Abstract

This work presents, to the best of our knowledge, the first experimental report of an erbium/ytterbium double-clad ring fiber laser based on nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) operating in a self-starting Q-switched high-order harmonic mode locking noise-like pulse (QHML-NLP) regime. The NPR mechanism relies on an arrangement composed of a beam splitter cube, a half-wave retarder, and a quarter-wave retarder. Through specific adjustments of the wave retarders and pump power, the laser cavity engages the QHML-NLP regime, where mode-locked burst-like pulses containing a significant number of NLPs are modulated by a giant Q-switched envelope. The laser system emits at the 132nd-order harmonic mode locking (HML) frequency, representing the highest order achieved to date in the framework of QHML-NLP. Additional features include a broadband optical spectrum with dual-wavelength emission at 1568.4 nm and 1605.9 nm, and maximum energies of 2.37 µJ for the Q-switched envelope and 200 nJ for the mode-locked burst-like pulse. These detailed experimental results reveal remarkable aspects in the NLP dynamics, contributing to a deeper understanding of their physical mechanisms and highlighting their potential as novel laser sources for micromachining and nonlinear optics.

1. Introduction

The study of fiber lasers is a thriving research field that drives the development of pulsed light sources for a wide range of applications, such as supercontinuum generation, micromachining, spectroscopy, optical communication, medical instrumentation, and many other applications [1,2,3,4]. Pulsed fiber lasers are commonly classified into Q-switched and mode-locked types, with a Q-switching technique that modulates the Q-factor (quality factor) of the laser cavity, managing relatively broad high-peak-power optical pulses at relatively low repetition rates of around a few tens of kHz, while the mode-locking technique generates high repetition rates, ultrashort optical pulse durations with equidistant frequency spacing. Q-switching and mode-locking fiber lasers can be designed to operate in both active and passive configurations. In particular, passive mode-locked fiber lasers (PMLFLs) have been the focus of extensive analyses, introducing optimized approaches in terms of high-power output, ultra-short pulse emission, high beam quality, and simplified cavity architectures [5,6,7,8,9,10]. PMLFLs are versatile schemes capable of emitting a diversity of pulse regimes such as conventional solitons [11], dissipative solitons [12], dark pulses [13], soliton rains [14], and noise-like pulses (NLPs) [15]. Among these, NLPs have attracted strong experimental and theoretical research interest because of their rich and complex characteristics. Some unique facets of NLPs involve a smooth and wide averaged optical spectrum, low temporal coherence, high-energy pulses, and a distinctive optical autocorrelation profile with a narrow peak positioned over a broad pedestal [16,17]. Their temporal shape consists of a wave packet of numerous ultrashort pulses drifting randomly framed in a variable structure. Despite the use of sophisticated optical instrumentation, the internal details of NLPs remain unresolved.

An attractive laser emission has emerged from the hybridization between Q-switching and mode-locking techniques, the so-called Q-switched mode locking (QML) operation, in which a continuous train of mode-locked pulses is embedded within a giant Q-switched envelope. This particular type of laser emission is suitable for applications such as supercontinuum generation, material processing, and multiphoton spectroscopy, applications that usually require high-power output pulses beyond the capability of conventional mode-locked lasers. The generation of QML emission has been demonstrated in a variety of laser architectures, including active schemes such as subharmonic cavity modulation and acousto-optic modulators [18,19], as well as passive schemes via artificial and natural saturable absorbers, such as nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) [20] and nanomaterials [21]. An additional desirable feature in the train of mode-locked pulses is the capacity to manipulate the repetition rate, as it enables potential applications in the field of data storage [22], optical telecommunications [23], and bioimaging [24]. Short laser cavities are generally more suitable for producing high repetition rate pulses. In contrast, fiber lasers face the limitation of cavity shortening due to the use of fiber elements (gain fibers, isolators, and couplers). A convenient approach to overcome this barrier is the implementation of high-order harmonic mode-locked (HML) pulses, which produce a pulse train spaced equidistantly within the cavity. At higher pump power levels, mode-locked pulses tend to enter into an unstable breakup, which results in pulse splitting followed by the multiplication of optical pulses [25,26]. Subsequently, the pulses rearrange into a well-organized pulse train with a repetition frequency that is a multiple of the fundamental mode-locked frequency, a behavior attributed to noise-seeded modulation instability [27]. In the case of HML in PMLFLs, this phenomenon has been associated with long-range interactions of pulses through implications of acoustic-wave effect (AW) [28,29], dispersive wave effect (DW) [30,31], and the gain depletion and recovery mechanism (GDR) [32,33]. A considerable number of studies focused on high-order HML in PMLFLs based on NPR can be found in the literature [34,35,36].

In this context, the use of Er/Yb co-doped double-clad fibers offers important advantages for high-order harmonic mode-locking, as they enable efficient high-power cladding pumping and enhanced nonlinear interactions inside the laser cavity. Previous works have shown that such configurations facilitate pulse splitting and self-organization processes, allowing the formation of stable harmonic pulse trains at high harmonic orders, which are difficult to achieve in conventional erbium fiber lasers due to their more limited pump power handling and nonlinear interaction strength [16,36].

On the other hand, research covering QML-NLP emission remains limited. For example, the generation of QML square-shaped NLP is reported in an erbium-doped PMLFL using an NPR scheme [37], where the evolution of the QML operation is investigated in the anomalous dispersion regime with different cavity lengths ranging from 50 to 200 m. The emission wavelength was centered at 1561.1 nm, while the QML repetition rate reports a similar trend to conventional Q-switched pulses, which increments as the pump power rises. In [6], the authors reported the formation of a broad-spectrum of QML-NLP in a thulium-doped fiber laser based on nonlinear polarization evolution. The optical spectrum exhibited a sharp peak at 1864 nm over a wide base, where the sharp peak corresponded to the QML and the wide base to the NLPs. The QML-NLP train also performs the typical behavior of increasing repetition rate as the pump power is incremented. A recent special aspect addressed in the framework of QML-NLP fiber lasers is the emission of HML pulses, with very few studies published. For instance, in [38], the experimental generation of Q-switched harmonic mode locking noise-like pulse (QHML-NLP) in an erbium-doped fiber laser was reported for the first time. The scheme operated based on the NPR technique, and with appropriate polarization adjustment, was capable of generating up to eight-order mode-locking. The optical spectrum showed a laser line centered at 1559.49 nm with a −3 dB bandwidth of 1.14 nm. However, further inner details of the NLPs were not provided.

In this work, we report for the first time the experimental emission of QHML-NLP in an erbium/ytterbium fiber laser. The laser cavity operates under the NPR technique, where a half-wave retarder (HWR), a quarter-wave retarder (QWR), and a polarized beam splitter cube (PBSC) perform the saturable absorber action. With a precise adjustment of the wave retarders and pump power well above the continuous-wave (CW) threshold emission, the laser cavity self-starts this special QHML-NLP regime. The fundamental cavity frequency in conventional mode locking operation is 847.4 kHz; however, when the laser emits in the QHML-NLP regime, the measured HML pulses underneath the Q-switched envelope reach 112.35 MHz, corresponding to high-order HML up to the 132nd order—representing, to date, the highest-order HML ever reported into the framework of QHML-NLP. From our perspective, the scarcity of studies on QHML-NLP makes this topic of great interest for advancing the development of new laser sources.

2. Materials and Methods

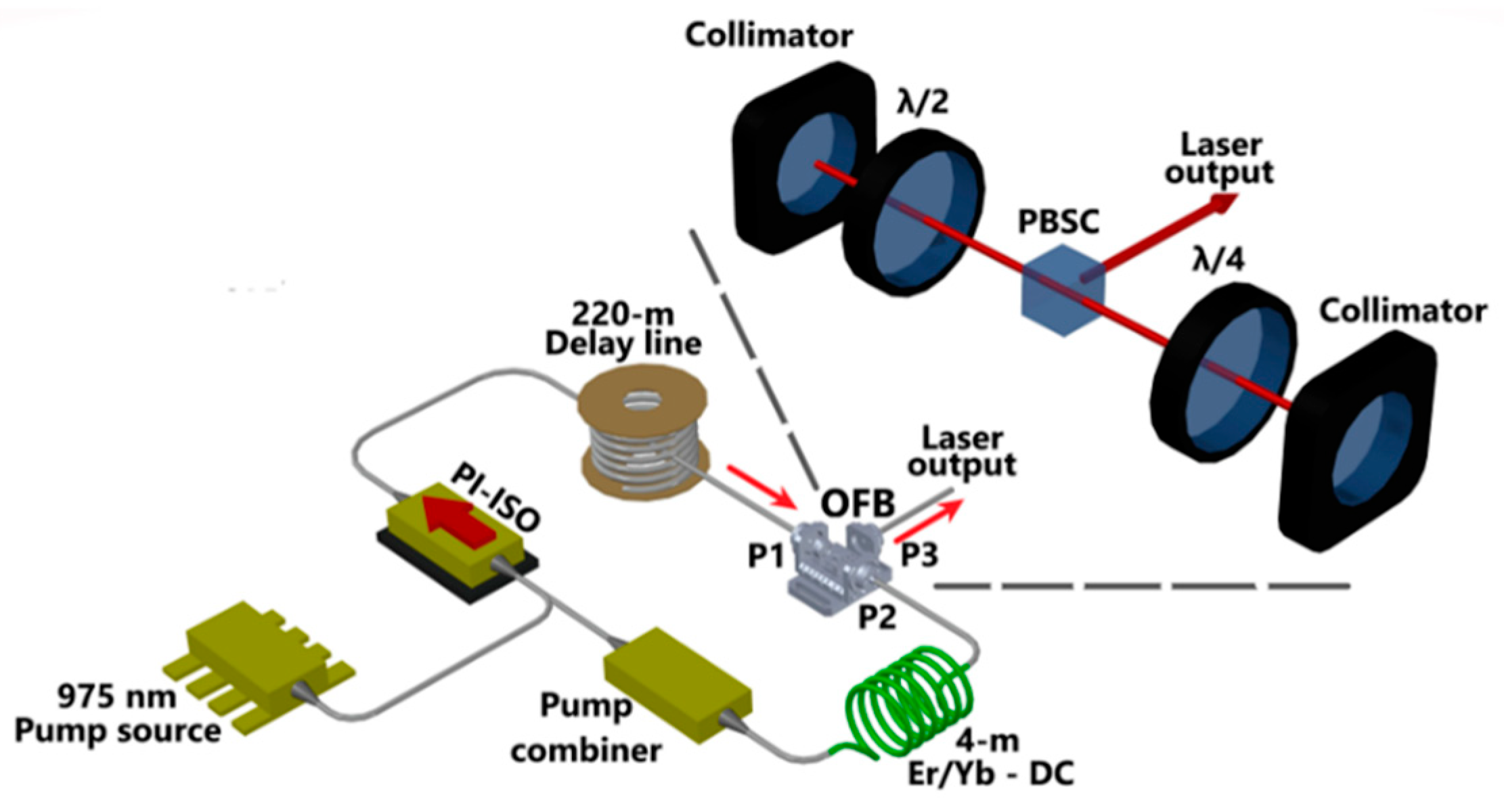

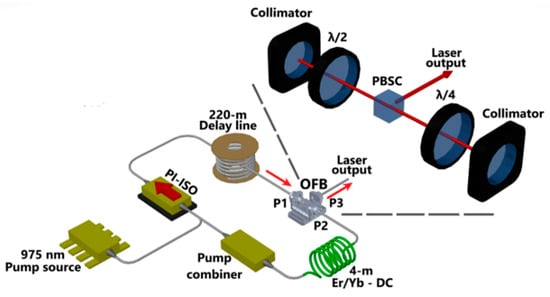

The schematic of the QHML-NLP fiber laser based on NPR is shown in Figure 1. The cavity was constructed with a 4 m long erbium/ytterbium co-doped double-clad fiber (Coractive, DCF-EY-10/128, Coractive, Québec, QC, Canada) as the active medium, with a group velocity dispersion (GVD) of −19 ps2/km. A pigtailed laser diode (Qphotonics, QSP-975–10, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) operating at 975 mW delivering up to 10 W of output power was used to pump the active medium via a (2 + 1) × 1 pump combiner (MPCS-2-M02-S03-D05-0–3 Gould Fiber Optics, East Granby, CT, USA). Following a clockwise layout, the signal port of the combiner was connected to a polarization-independent isolator (PI-ISO), enforcing unidirectional propagation within the cavity. A 220 m spool of standard optical fiber (Corning SMF-28e, Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA), twisted at a rate of 7 turns per meter with GVD of −21 ps2/km, was added after the PI-ISO as a boosting instrument for the NPR effect and self-starting operation. Next, a 3-port optical fiber bench (OFB, Thorlabs bench FT-51X60 with collimators PAF-X-2-C, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) was inserted to control the intracavity polarization state and optimize the laser performance. The OFB comprised a QWR (Thorlabs FBRP-AQ3, 1100–2000 nm, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA), a HWR (Thorlabs FBRP-AH3, 1100–2000 nm, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA), and a 5 mm PBSC (Thorlabs PBS054, 1200–1600 nm, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) inserted between them. This OFB enabled the redirection of optical power either toward the laser output (port P3) or back into the cavity (port P2) through precise adjustments of the wave retarders. The cavity was closed by splicing port P2 to the end of the active fiber, while the laser output was monitored through port P3. The overall length of the laser cavity was determined as 246 m, and the net dispersion of the entire cavity was calculated as −5.16 ps2, indicating operation within the anomalous dispersion regime. For characterization, measurement instrumentation includes an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA, Yokogawa AQ6375, Yokogawa Test & Measurement, Tokyo, Japan) with 50 pm resolution, a 20 GHz bandwidth ultrafast photodetector (Thorlabs, DXM20AF, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) paired with a 20 GHz real-time oscilloscope (Oscilloscope, DPO72004C, Tektronix Inc., Beaverton, OR, USA), a 5 GHz photodetector (Thorlabs DET08CFC, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) combined with a 3.2-GHz radiofrequency spectrum analyzer (RF, Siglent SSA3032X, Siglent Technologies, Shenzhen, China), and a Femtochrome autocorrelator (FR-103XL, Femtochrome Research Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA). This robust instrumentation ensured complete and detailed experimental data acquisition.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup of the QHML-NLP fiber laser.

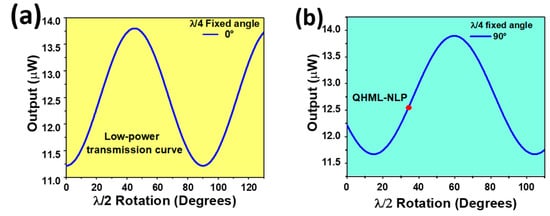

Adjustment of the OFB for a Controlled Tuning of the QHML-NLP

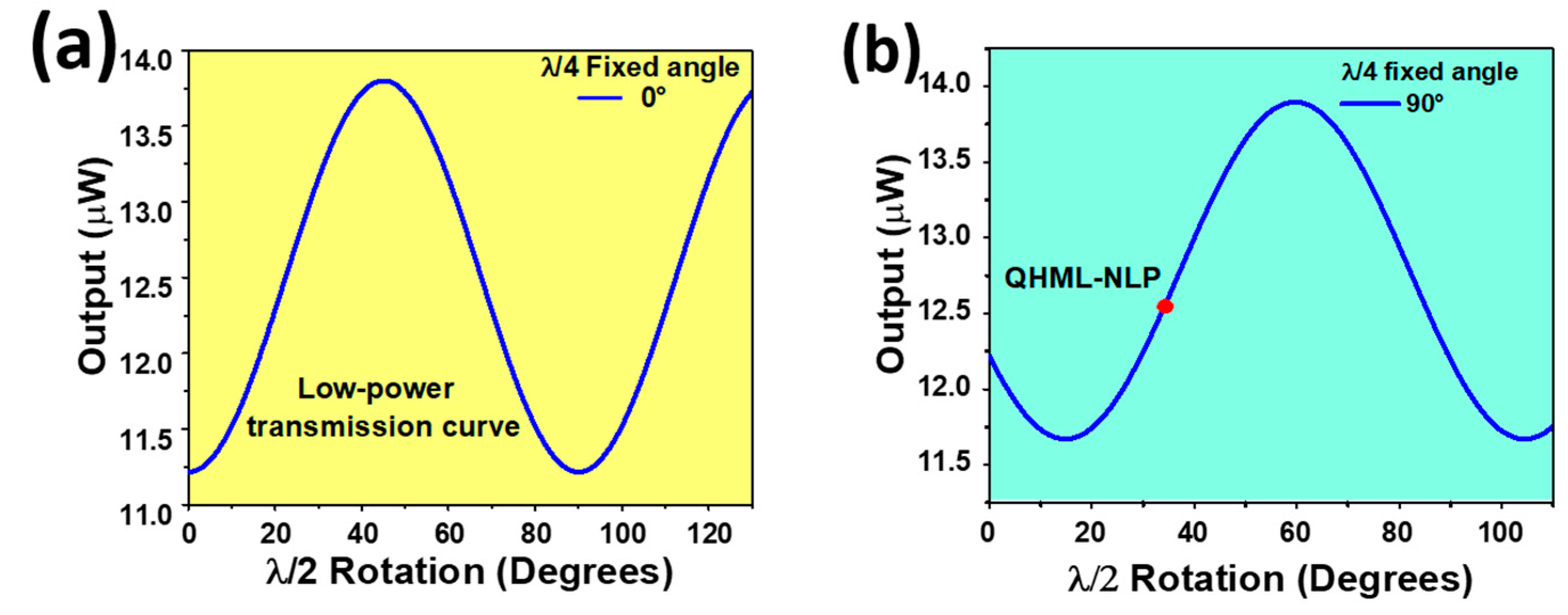

The OFB is integrated by an HWR, a PBSC, and a QWR connected in series to implement the NPR effect in the laser cavity. This arrangement offers a high damage threshold, relatively low-insertion loss, and provides a fast response time, making this arrangement an effective artificial saturable absorber system for the fiber laser. The laser system requires initial adjustments on the OFB to operate in a continuous low-power regime. Thus, by setting the wave plates’ angles, the transmission of light is regulated to be transmitted back into the laser cavity through the QWR and port P2 with maximal transmission. Hence, a minimum emission of light is measured at the laser output (port P3). This minimal transmission is enabled with a rotation angle of 0° at the HWR and QWR. Then, only the HWR is carefully rotated and the laser output is recorded. A periodic dependence on the rotation angle is observed, as shown in Figure 2a. Therefore, the generated trace is a valuable low-power transmission curve for identifying and tuning diverse pulsed regimes (conventional solitons, harmonic mode-locked, conventional NLP, and burst-like NLP, among others) once pump power is increased in the laser setup. Moreover, the QWR angle adds another degree of freedom, and it also expands the range of achievable pulsed emission regimes. To systematically explore these pulse regimes, the following procedure was implemented: (1) set the laser system on the low-power transmission regime, i.e., where minimal light emission is observed at the laser output; (2) QWR is rotated by a small step and fixed its position; (3) HWR is completely rotated to generate the corresponding low-power transmission curve; (4) the process is repeated until a full rotation of QWR is covered. Hence, a low-power transmission curve is generated for each QWR angle position. These adjustments demonstrated that the QWR strongly influences the low-power transmission curve, while also providing a practical and precise manner to locate different lasing regimes. Specifically, QHML-NLP emission was obtained at pump power in the range of 2.72 W to 3.09 W, when the QWR angle was positioned at 90°, and the HWR angle at 34°, as presented in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Initial adjustments. (a) Low-power transmission curve and (b) QHML-NLP operational point.

3. Results and Discussion

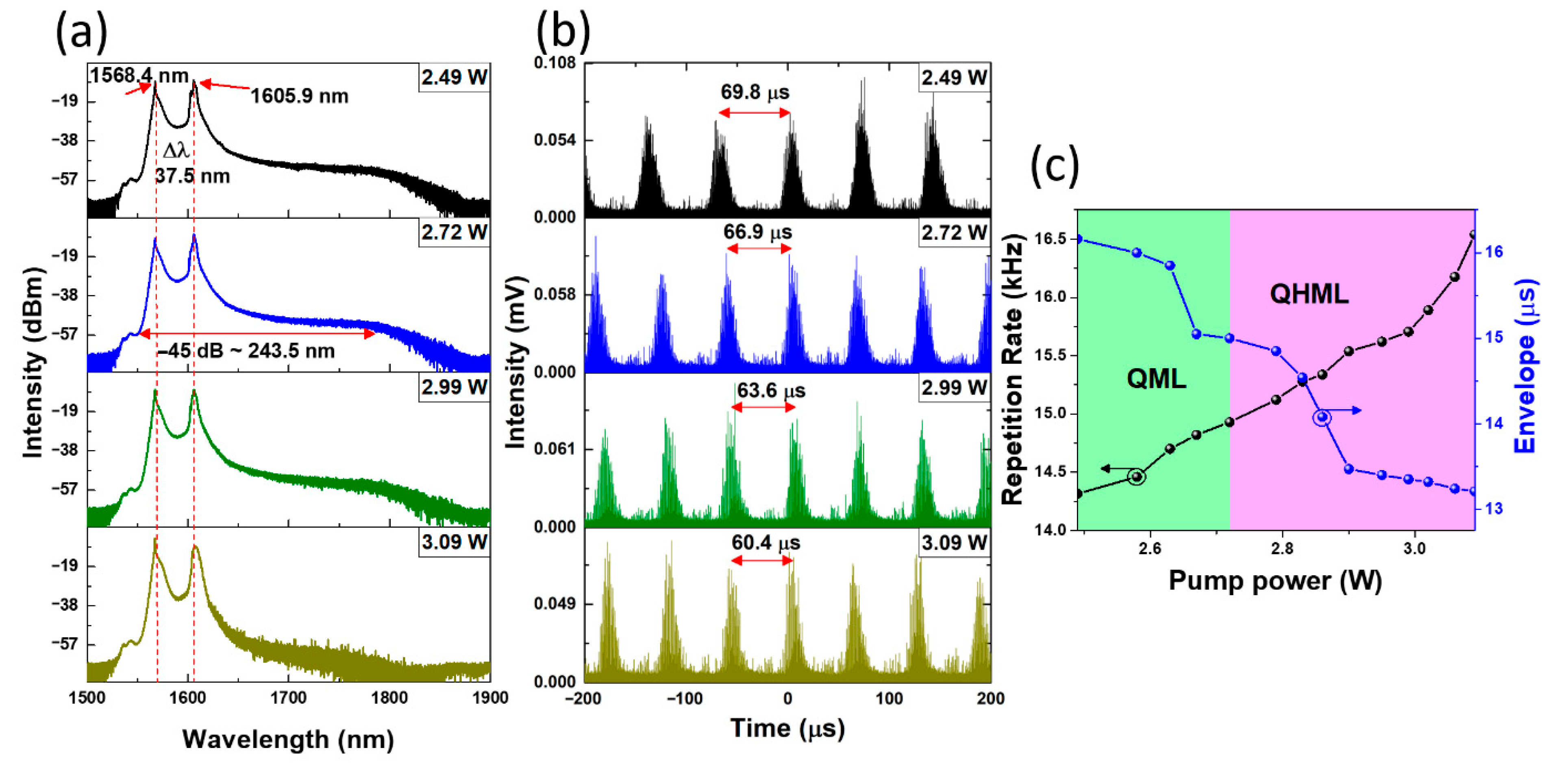

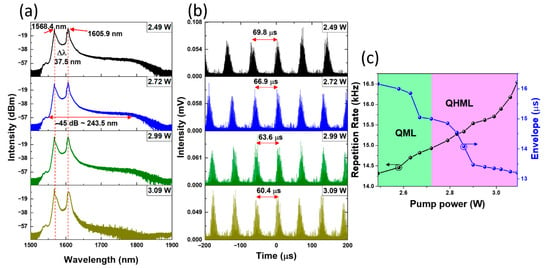

In our experiment, the QHML-NLP was detected on the positive slope of the low-power transmission curve, as observed in the trace shown in Figure 2b. The QWR and HWR angle rotations were set to 90° and 34°, respectively. These precise tune angle rotations were determined after performing a complete rotation sweep for each wave plate. With a pump power ranging from 2.49 W to 3.09 W, a self-starting steady state QML emission with a regular temporal period is obtained. Figure 3 presents the optical spectrum and oscilloscope traces of the QML pulse trains at different pump power values. Each of the optical spectra can be considered a dual-wavelength emission, exhibiting two pronounced wavelength peaks at 1568.4 nm and 1605.9 nm, presenting a wavelength separation (Δλ) of 37.5 nm. Those peaks showed good stability across the range of pump powers, as depicted in Figure 3a. This dual-wavelength emission can be attributed to the strong nonlinear spectral broadening occurring in the QHML-NLP regime, combined with the broad gain bandwidth of the erbium-doped fiber. At high intracavity power levels, multiple spectral components are generated and simultaneously satisfy the lasing condition through spectral and polarization-dependent gain competition, a behavior commonly observed in noise-like pulse fiber lasers operating under strong nonlinear regimes [39], which are known to promote efficient nonlinear spectral broadening and are widely considered suitable for supercontinuum-related applications [1].

Figure 3.

QHML-NLP evolution across pump power. (a) Optical spectrum evolution, (b) time-domain traces evolution, (c) Q-switched characteristics, repetition rate, and envelope versus pump power.

Considering the overall spectral shape, it broadens toward a long-wavelength region, clearly portraying supercontinuum properties, with a −45 dB optical bandwidth (BW) of 243.5 nm, as measured from the blue trace. The respective oscilloscope traces, showing the evolution of the temporal profiles as a function of pump power, are reported in Figure 3b. These traces illustrate the expected behavior of a Q-switched regime, an increment in repetition rate of the Q-switched envelope when increasing the pump power [40]. Figure 3c illustrates the repetition rate rising from 14.3 kHz (68.9 µs pulse separation) to 16.5 kHz (60.6 µs pulse separation) as the pump power increases from 2.49 W to 3.09 W. In contrast, the envelope pulse width decreases with increments of pump power, from 16.1 µs to 13.2 µs, as depicted by the blue line. The green shaded zone indicates the pump power values where pure QML emission is observed, while the purple shaded zone implies the generation of QHML emission at pump powers exceeding 2.72 W.

Although Figure 3c shows two distinct operational NLP regimes (QML and QHML), the scope of this work is limited to the analysis of the QHML-NLP phenomenon, which is presented as follows. It is worth noting that the transition from QML to QHML is not identified by changes in the repetition rate or the temporal width of the Q-switched envelope. Instead, the onset of the QHML regime is determined by the emergence of multiple equally spaced mode-locked pulses, as revealed by the temporal analysis presented in Figure 4. This pulse multiplication leads to the formation of a harmonic pulse train within the Q-switched envelope, whose detailed temporal characteristics are discussed below.

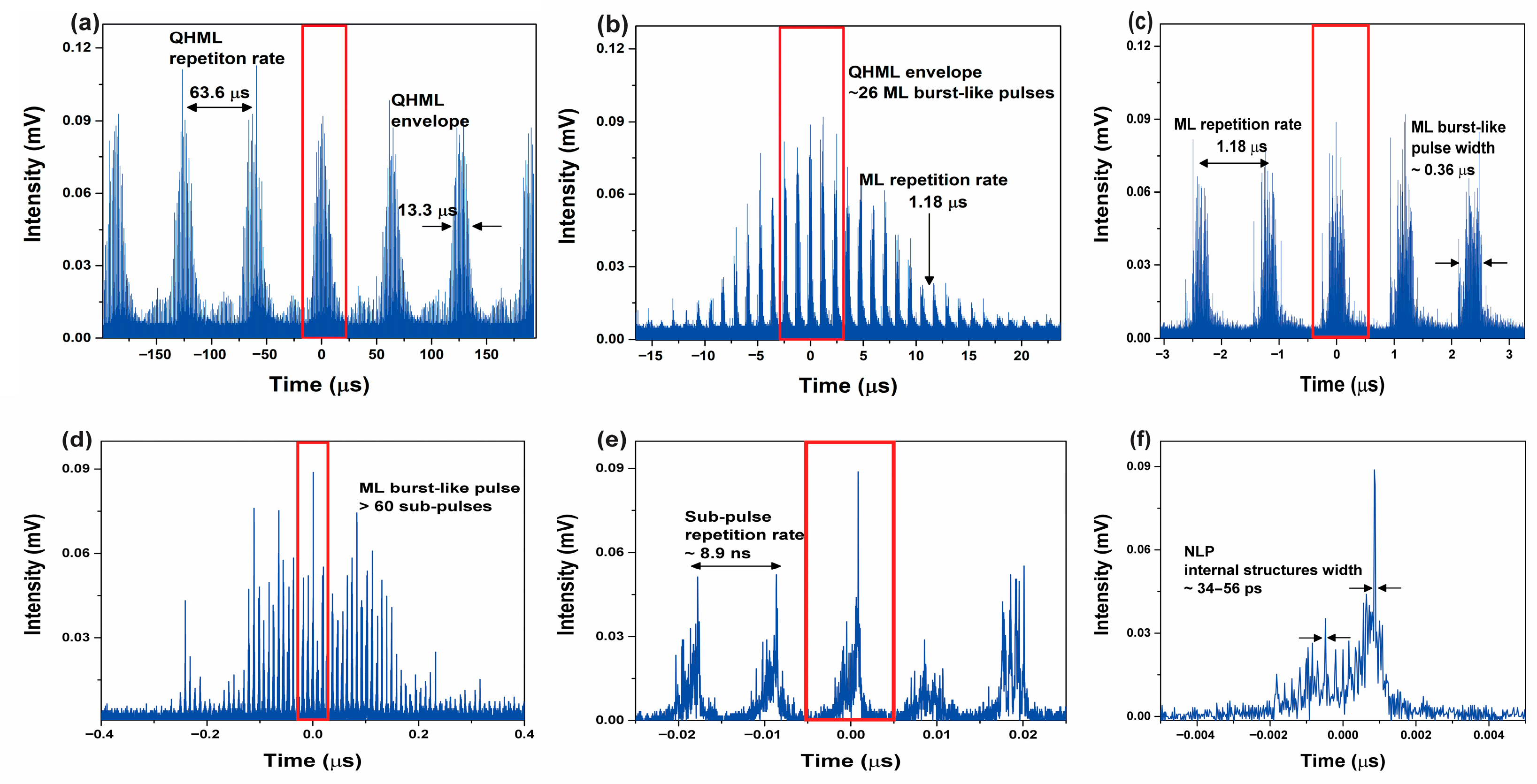

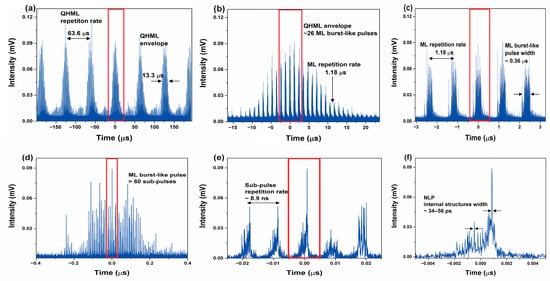

Figure 4.

QHML-NLP at successively shorter time scales. (a) QHML-NLP emission, (b) mode-locked train under a Q-switched envelope, (c) mode-locked burst-like pulse characteristics, (d) high-order harmonics mode-locked, (e) sub-pulse characteristics, and (f) NLP inner composition.

As observed in Figure 3c, the QHML-NLP regime was recorded for pump powers ranging from 2.72 W to 3.09 W. In our approach, the mode-locked pulses at the fundamental frequency, modulated within the Q-switched envelope, undergo a sudden breakup when the pump power reaches 2.72 W, transitioning the emission into a special high-order HML state that gives rise to the QHML-NLP emission. Figure 4 displays single-shot captures of six successive oscilloscope traces recorded at a pump power of 2.72 W, where the region enclosed by red boxes in Figure 4a–e represents a progressive zoomed-in time-domain view of the hybrid regime. Figure 4a shows the oscilloscope trace over a 400 µs time span, exhibiting uniformly sequenced Q-switched envelopes with a temporal spacing of 63.6 µs, corresponding to a repetition rate of 15.7 kHz, and an envelope duration of approximately 13.3 µs. The pulsed train consists of mode-locked pulses modulated by giant Q-switched envelopes. Outside the Q-switched envelopes, the CW mode-locked pulse train can still be perceived, suggesting that, despite the considerable amount of energy manifested in each Q-switched pulse, it is insufficient to accumulate enough intracavity energy to fully saturate the gain. This allows harmonic locked pulses to radiate in the inter-pulse regions, together with smaller soliton-like pulses drifting into a condensed phase. Figure 4b displays a single QHML envelope containing a train of about 26 mode-locked burst-like pulses emitting at a round-trip time of 1.18 µs, which is consistent with the fundamental frequency of 847.4 kHz for a cavity length of 246 m. To elucidate the internal composition of the mode-locked burst-like pulses, Figure 4c presents a train of five of these pulses with an estimated full width at the half maximum (FWHM) of ~0.46 µs. From this particular point of view, the burst-like pulses appear to be composed of complex inner sub-structures that drift randomly in intensity and temporal position (a typical feature of NLPs). A close-up view of a single mode-locked pulse reveals more than 60 well-defined, equidistant time-separation NLPs forming the burst, which is a characteristic of an HML regime, as shown in Figure 4d. Moreover, these NLPs oscillate at a frequency of 112.35 MHz, corresponding to the inverse of the minimum time interval of ~8.9 ns. It is worth noting that, due to the nature of NLPs, the sub-pulse duration may vary for each single-shot capture, ranging from a few hundred ps to several ns. However, the inter-pulse separation of ~8.9 ns remains stable throughout the lasing operation. In this case, the average sub-pulse duration was estimated as 2.5 ns, as depicted in Figure 4e. This frequency represents the 132nd-order harmonic of the fundamental mode locking frequency, surpassing by a factor of 16.5 the highest value previously reported in the context of QHML-NLP regime [38]. Finally, Figure 4f illustrates the central NLP, providing a detailed experimental snapshot of its internal composition, where random sub-structures oscillate in both temporal position and intensity, with time durations ranging from 34 ps to 56 ps. To the best of our knowledge, this constitutes the first and most detailed experimental report on higher-order harmonics in a QML regime under the NLP phenomenon.

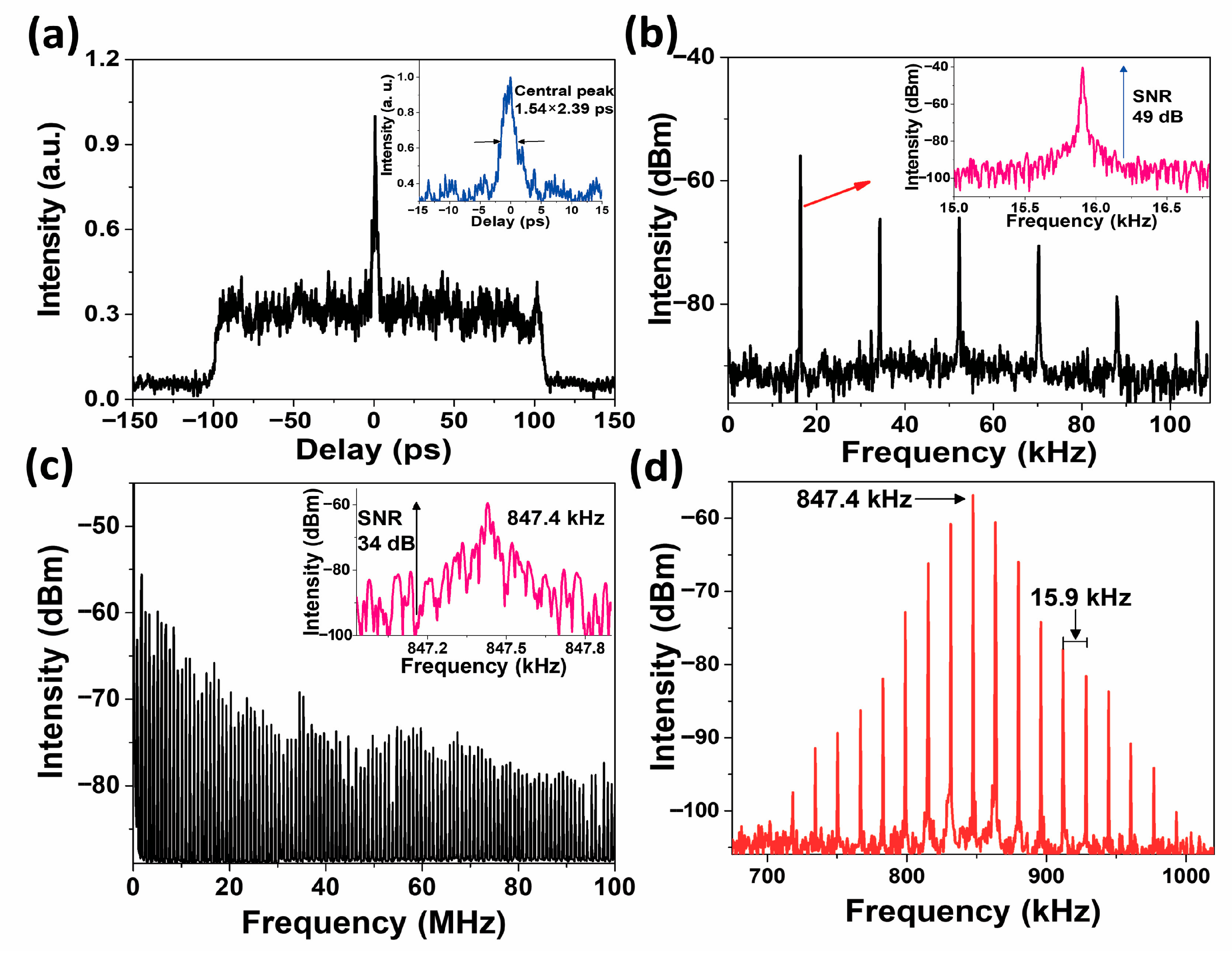

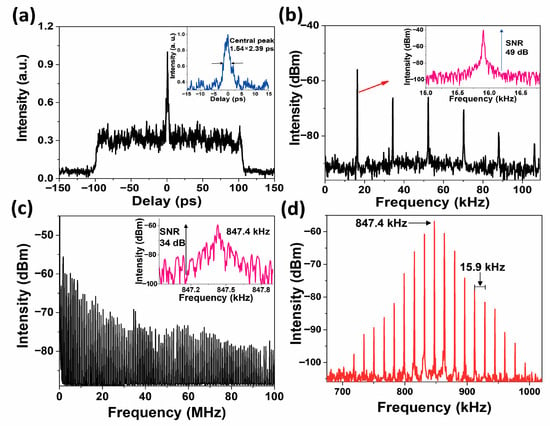

The main properties of the NLPs include a broad and smooth average spectrum, nanosecond or picosecond overall temporal scales, and a composition of inner sub-pulse structures drifting randomly in intensity and temporal position [41]. In addition to these features, a very distinctive characteristic of NLPs is a double-scale autocorrelation trace. This signature ensures that NLP operation persists into the QHML emission, as illustrated in Figure 5a. It displays a fine central spike riding on a broad pedestal, with a pedestal-to-peak intensity ratio of approximately 0.3. The noisy contribution observed on the autocorrelation shoulders suggests that the QHML pulse is composed of multiple contiguous pulses. The inset shows a zoomed-in view of the central peak assuming a sech2-shaped temporal profile, confirming that the pulse is composed of fine formations with estimated FWHMs of about 2.39 ps. To assess the quality and stability of the QHML-NLP laser, the radio frequency (RF) electrical spectrum was measured over different spans. Figure 5b shows the RF spectrum over a 100 kHz frequency span, recorded with a resolution bandwidth (RBW) of 100 Hz, indicating the Q-switched frequency operation. Additionally, the inset depicts a single frequency peak recorded over a 2 kHz span with a 10 Hz RBW, showing a single-to-noise ratio (SNR) of about 49 dB. Minor timing jitter and amplitude fluctuations were observed, confirming the good stability of the pulse. This SNR level indicates that the output signal is much greater than the noise power, indicating reliable pulse emission and consistent measurements. The mode-locked frequency is confirmed by an RF trace recorded for over 100 MHz with a 10 kHz RBW, as depicted in Figure 5c. It shows a series of equidistantly spaced frequency components associated with the fundamental mode locking frequency of 847.4 kHz and its harmonics. This well-defined trace reflects stable mode-locked radiation with regular pulsing, demonstrating the periodic behavior of the pulse train. The inset shows the fundamental frequency with an SNR of ~34 dB, recorded over a 1 kHz span at 10 Hz RBW. A noticeable noisy pedestal is present beside the fundamental repetition frequency, a common observation for NLPs that is attributed to amplitude noise. A typical electric spectral profile of QML emission is depicted in Figure 5d, showing a central frequency peak accompanied by several neighboring frequency components. The main peak is located at 847.4 kHz, which is linked to the fundamental mode locking frequency of the laser cavity. Side frequency contributions spaced at 15.9 kHz are related to the Q-switched pulse repetition rate. This RF trace indicates that the amplitude Q-switched modulation at 15.9 kHz is imposed onto the CW mode-locked pulse train [18]. Overall, the RF measurements confirm that the saturable absorber effectively provides the mechanism to initiate a QML regime.

Figure 5.

QHML-NLP autocorrelation and RF measurements. (a) Double-scale autocorrelation trace confirming a NLP regime in the QHML pulse emission; the fine peak is shown in the inset, (b) RF spectrum over a 100 kHz span, indicating the Q-switched operation; inset shows the frequency of the Q-switched envelope, (c) RF spectrum over a 100 MHz span, inset describes the fundamental mode-locked frequency, (d) characteristic RF with modulation sidebands spectrum for the QHML-NLP laser.

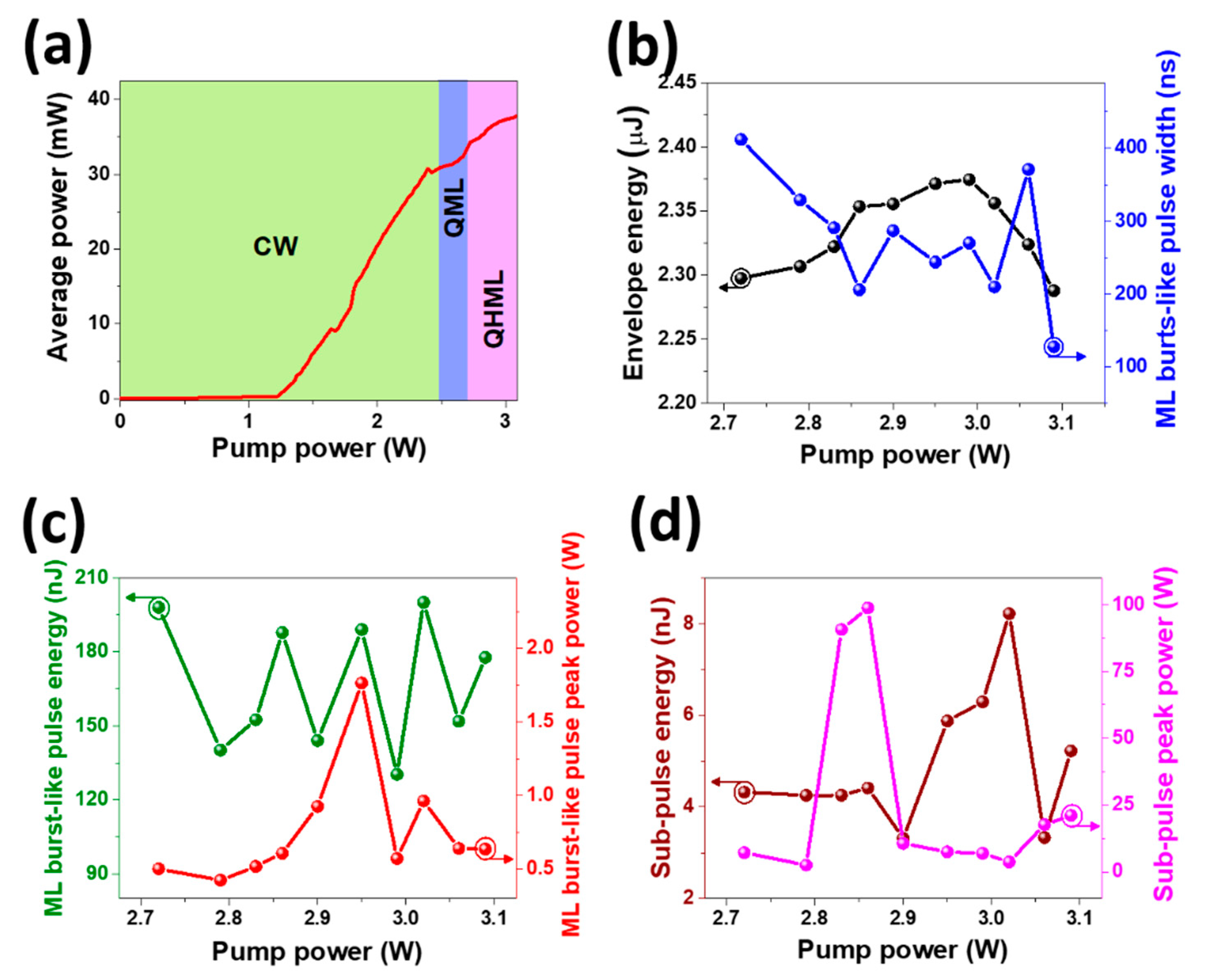

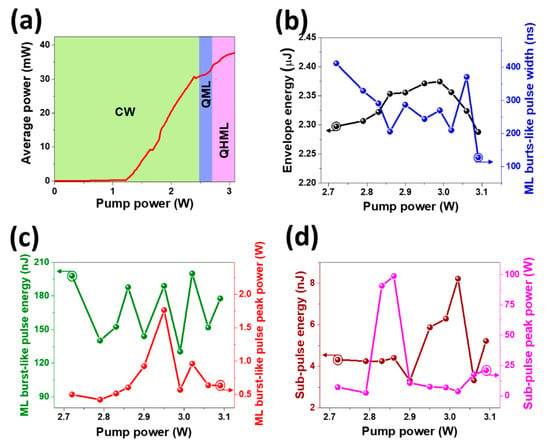

The output characteristics of QML-NLPs exhibiting high-order mode looking are presented in Figure 6. The variation in average power (red line) as a function of pump power is presented in Figure 6a. This trace exhibits an almost linear trend from a pump power of 1.2 W onward, while the NLP regime extends from 2.49 W to the maximum pump power of 3.09 W. The NLP region encompasses both QML (blue-shaded zone) and QHML (purple-shaded zone) regimes, with the latter occurring between 2.72 W and 3.09 W. The slope efficiency was estimated to be ~2%. The following plots display only data above 2.72 W, corresponding exclusively to the QHML regime, which is the focus of this work. The response of envelope energy (black line) and mode-locked burst-like pulse temporal width (blue line) as functions of pump power are shown in Figure 6b. It can be observed that the pump power does not substantially affect the envelope energy, leading to only minor variations, reaching a maximum of 2.37 µJ. The burst-like pulse width exhibits oscillations along the pump power, with no clear monotonic trend; the minimum and maximum widths registered were about 128 ns and 412 ns, respectively. This behavior is consistent with the chaotic nature associated with NLPs. It is important to note that the data obtained from the output signal analysis were extracted from single-shot measurements acquired at the maximum bandwidth resolution (20 GHz) of our real-time optoelectronic instrumentation. The mode-locked burst-like pulse energy and peak power as functions of pump power were also evaluated, as shown in Figure 6c. The data were extracted from the central mode-locked burst under the Q-switched envelope, where the significant oscillations in pulse width are reflected in the following traces. The method of numerical integration from the oscilloscope single-shot trace was used to estimate both mode-locked burst-like pulse energy (green line) and peak power (red line). The maximum energy achieved was approximately 200 nJ at a pump power of 3.02 W, placing it among the most energetic mode-locked burst pulses reported within the framework of QML, while the highest recorded peak power was 1.76 W at a pump power of 2.95 W. Moreover, it is also of interest to approximate the energy and peak power associated with a single HML sub-pulse. Employing the same numerical method, the central sub-pulse within the mode-locked burst was analyzed to assess its energy (wine line) and peak power (pink line), as shown in Figure 6d. For this central sub-pulse, the maximum energy was about 8.21 nJ at a pump power of 3.03 W, while the highest peak power reached nearly 100 W at a pump power of 2.86 W. It is also worth noting that each of these sub-pulses (NLPs) is composed of multiple picosecond-scale substructures in continuous motion, which results in varying peak power values across different measurements. The QML fiber lasers have proven to be an efficient platform for generating pulses with high energy and peak powers. In our work, further improvements in cavity losses management, external amplification, optimization of conversion efficiency, or enhancement of pump power could lead to significant benefits in the output performance.

Figure 6.

QHML-NLP output pulse characteristics. (a) Average power, (b) envelope energy and mode-locked burst-like pulse width, (c) mode-locked burst-like pulse energy and peak power, and (d) sub-pulse energy and peak power.

The build-up of QHML-NLPs results from a complex synergy among dispersion, cavity gain and losses, and nonlinear effects. Previous works have suggested that QML formation can evolve from CW lasing, in combination with precise polarization adjustments and correct management of pump power [6,20]. In our case, this process is associated with the correct tuning and rotation of the wave plates, which link the NPR mechanism to the saturable absorption, leading to complex evolution dynamics within the laser cavity. Three main effects have been discussed as responsible for the generation of an HML state: GDR, DW, and AW [28,29,30,31,32,33,42,43]. As the pump power increases, the interaction between NLP and the soliton-DW becomes stronger, possibly making this effect responsible for the stable NLP wave packet pulse breaking into unstable NLP wave packets. Furthermore, proper NPR adjustments can modify the cavity nonlinearities, causing internal unbalances within the NLP wave packet that also contribute to pulse splitting [44]. In our case, this action leads to the formation of a new packet, referred to as the burst-like pulse, which belongs to the NLP regime and is observed underneath the Q-switched envelope. Due to the inter-pulse time separation observed between these recently formed burst-like pulses, it can be considered that attractive forces acting over the bursts may be associated with the DW and GDR effects. Although the typical Kelly sidebands observed from soliton-DW effect are not evident on the NLP optical spectrum—since the output represents an average response including random sub-pulse drifts [45]—its effects could still play a role in the pulse breaking, transformation, and multiplication of the NLP packet. Additionally, the AW effect may contribute to the HML stability, as the fiber geometry allows it to act as a resonator excited at discrete natural eigenfrequencies [27,38,43]. In this context, the formation of QHML-NLP in our system could be analogous to the generation of HML pulses originating from a primary CW mode-locked state.

4. Conclusions

We have experimentally demonstrated, for the first time, the generation of high-order HML pulses under a Q-switched envelope within the NLP regime, featuring a broadband width dual-wavelength optical spectrum in an erbium/ytterbium ring fiber laser. The NPR effect acts as the saturable absorption mechanism through an optical fiber bench composed of an HWR, a QWR, and a PBSC. Precise rotation of the wave retarders with adequate pump powers enables stable operation in the QHML-NLP regime. The emitted radiation exhibits dual-wavelength lasing at 1568.4 nm and 1605.9 nm, with maximum energies of 2.37 μJ for the Q-switched envelope and 200 nJ for the mode-locked burst-like pulse. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report achieving the 132nd-order harmonic of the fundamental mode locking frequency in the framework of QHML-NLP, surpassing previously reported HML orders by a significant margin. The maximum energy of a single NLP was estimated as 8.21 nJ. This work provides a high-speed characterization that reveals the detailed inner composition of the envelope with ps resolution, contributing to a deeper understanding of the complex NLP dynamics in this hybrid regime.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.H.-E.; Methodology, J.L.F.-G., E.N.H.-E., Y.N.-M., L.A.R.-M., M.A.G.-R. and M.D.-S.; Validation, M.Á.B.-J., R.E.L.-E., O.P., L.A.R.-M., M.A.G.-R., M.D.-S. and B.I.-E.; Formal analysis, M.V.H.-A., J.L.F.-G. and Y.N.-M.; Investigation, M.V.H.-A., J.L.F.-G. and Y.N.-M.; Writing—original draft, M.V.H.-A.; Visualization, R.E.L.-E., E.N.H.-E., O.P., L.A.R.-M., M.A.G.-R., M.D.-S. and B.I.-E.; Supervision, M.Á.B.-J., O.P. and B.I.-E.; Project administration, R.E.L.-E.; Funding acquisition, M.Á.B.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by SECIHTI (formerly CONAHCyT) under Grant CBF2023-2024-1981. J. L. Flores-Gonzalez was supported by SECIHTI doctoral grant 935357. M. V. Hernández-Arriaga thanks SECIHTI postdoctoral fellow 2269202. E. Escobar-Hernández thanks SECIHTI postdoctoral fellow 3787819. Y. Navarro-Martínez was supported by SECIHTI doctoral grant 837841. L. A. Rodríguez-Morales thanks SECIHTI postdoctoral fellow 2482407.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xia, H.; Li, H.; Deng, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Compact noise-like pulse fiber laser and its application for supercontinuum generation in highly nonlinear fiber. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 9379–9384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Fu, S.; Tang, M.; Liu, D. Femtosecond laser micro-machining enabled all-fiber mode selective converter. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 5941–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Shi, H.; Chai, L.; Hu, M. Dual-comb spectroscopy with a single free-running thulium-doped fiber laser. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 11046–11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traxer, O.; Keller, E.X. Thulium fiber laser: The new player for kidney stone treatment? A comparison with Holmium: YAG laser. World J. Urol. 2019, 38, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, L.A.; González-Vidal, L.M.; Armas-Rivera, I.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Hernández-Arriaga, M.V.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Hernandez-Garcia, J.C.; Lauterio-Cruz, J.P.; Pottiez, O. Spatio-temporal study of single and multi-wavelength quasi-continuous-wave generation regimes in an all-normal dispersion ring cavity. Optik 2024, 298, 171598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Yan, D.; Wang, C. Broad-spectrum noise-like pulse and Q-switched noise-like pulse in a Tm-doped fiber laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 148, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, H.; Lan, C.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Graphene/WS2 heterostructure saturable absorbers for ultrashort pulse generation in L-band passively mode-locked fiber lasers. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11514–11523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, H.; Luo, F.; Zhu, L. A switchable dual-wavelength fiber laser based on phase shifted fiber Bragg grating combined with Sagnac loop. Optoelectron. Lett. 2019, 15, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Nithyanandan, K.; Coillet, A.; Tchofo-Dinda, P.; Grelu, P. Optical soliton molecular complexes in a passively mode-locked fibre laser. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grelu, P.; Akhmediev, N. Dissipative solitons for mode-locked lasers. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Lu, H. Formation and evolution of passively mode-locked fiber soliton lasers operating in a dual-wavelength regime. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2012, 29, 2819–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Hernández, H.; Bracamontes-Rodríguez, Y.E.; Beltrán-Pérez, G.; Armas-Rivera, I.; Rodríguez-Morales, L.A.; Pottiez, O.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Hernández-Arriaga, M.V.; Kuzin, E.A. Initial conditions for dissipative solitons in a strict polarization-controlled passively mode-locked Er-Fiber laser. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 25036–25045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Mora, A.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Espinosa-De-La-Cruz, E.A.; Alcántara-Bautista, U.; Ibarra-Garrido, A.; Armas-Rivera, I.; Rodríguez-Morales, L.A.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B. High-Order Domain-Wall Dark Harmonic Pulses and Their Transition to H-Shaped and DSR Pulses in a Dumbbell-Shaped Fiber Laser at 1563 nm. Micromachines 2025, 16, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Lv, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, C. SnSe2 realizes soliton rain and harmonic soliton molecules in erbium-doped fiber lasers. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 165203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Jiménez, M.; Hernández-Arriaga, M.V.; López-Estopier, R.; Alaníz-Baylón, J.; Hernández-Escobar, E.; Pottiez, O.; Rodríguez-Morales, L.A.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B. Single-shot characterization of special multi-soliton and noise-like pulse emissions in a mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 176, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterio-Cruz, J.P.; Hernandez-Garcia, J.C.; Pottiez, O.; Estudillo-Ayala, J.M.; Kuzin, E.A.; Rojas-Laguna, R.; Santiago-Hernandez, H.; Jauregui-Vazquez, D. High energy noise-like pulsing in a double-clad Er/Yb figure-of-eight fiber laser. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 13778–13787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yan, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Hou, Y. Noise-like pulse generation from a thulium-doped fiber laser using nonlinear polarization rotation with different net anomalous dispersion. Photonics Res. 2016, 4, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.H. A Q-switched, mode-locked fiber laser employing subharmonic cavity modulation. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 26627–26633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Laborde, C.; Díez, A.; Cruz, J.L.; Andrés, M.V. Doubly active Q switching and mode locking of an all-fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 2709–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Estopier, R.; Camarillo-Avilés, A.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Pottiez, O.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B.; Rivera-Pérez, E.; Andrés, M.V. Q-switched mode locking noise-like pulse generation from a thulium-doped all-fiber laser based on nonlinear polarization rotation. Results Opt. 2021, 5, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Du, Y.; Han, M.; Shu, X. Mode-locked and Q-switched mode-locked fiber laser based on a ferroferric-oxide nanoparticles saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 13177–13186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; He, W.; Jiang, X.; Russell, P.S.J. All-optical bit storage in a fibre laser by optomechanically bound states of solitons. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, M. Ultrafast mode-locked fiber lasers for high-speed OTDM transmission and related topics. J. Opt. Comm. Rep. 2005, 2, 462–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.D.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, M.Y.; Kim, C.S. Characterization of wavelength-swept active mode locking fiber laser based on reflective semiconductor optical amplifier. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 14586–14593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, J.; Dias, F.; Erkintalo, M.; Genty, G. Instabilities, breathers and rogue waves in optics. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Sorokina, M.; Sugavanam, S.; Tarasov, N.; Turitsyn, S.K. Real-time observation of dissipative soliton formation in nonlinear polarization rotation mode-locked fibre lasers. Commun. Phys. 2018, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pang, M. Revealing the Buildup Dynamics of Harmonic Mode-Locking States in Ultrafast Lasers. Laser Photonics Rev. 2019, 13, 1800333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudinin, A.B.; Payne, D.N. Passive harmonic modelocking of a fibre soliton ring laser. Electron. Lett. 1993, 29, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Grudinin, A.B.; Loh, W.H.; Payne, D.N. Femtosecond harmonically mode-locked fiber laser with time jitter below 1 ps. Opt. Lett. 1995, 20, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, W.H.; Grudinin, A.B.; Afanasjev, V.V.; Payne, D.N. Soliton interaction in the presence of a weak nonsoliton component. Opt. Lett. 1994, 19, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Crespo, J.M.; Akhmediev, N.; Grelu, P.; Belhache, F. Quantized separations of phase-locked soliton pairs in fiber lasers. Opt. Lett. 2003, 28, 1757–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobko, D.A.; Okhotnikov, O.G.; Zolotovskii, I.O. Long-range soliton interactions through gain-absorption depletion and recovery. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 2862–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, R.; Bekker, A.; Smulakovsky, V.; Fischer, B.; Gat, O. Noise-mediated Casimir-like pulse interaction mechanism in lasers. Optica 2016, 3, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Fan, D. Ultra-high order harmonic mode-locking of a Raman fiber laser. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 092002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Niang, A.; Guesmi, K.; Salhi, M.; Sanchez, F. 1.61 μm high-order passive harmonic mode locking in a fiber laser based on graphene saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 29921–29926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobon, G.; Krzempek, K.; Kaczmarek, P.; Abramski, K.M.; Nikodem, M. 10GHz passive harmonic mode-locking in Er–Yb double-clad fiber laser. Opt. Commun. 2011, 284, 4203–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Yao, Y.; Wu, Q.C.; Xu, K.; Xu, X.C.; Tian, J.J. Evolutions of Q-switched mode-locked square noise-like pulse with different cavity lengths. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 3641–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, C.R.; Gowrishankar, R.; Srivastava, S. Harmonic mode-locked noise-like pulses under a Q-switched envelope in an erbium doped all-fiber ring laser. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 7354–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Huerta, E.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Álvarez-Tamayo, R.I.; Santiago-Hernández, H.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Posada-Ramírez, B.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B.; Pottiez, O.; Kuzin, E.A. Single and dual-wavelength noise-like pulses with different shapes in a double-clad Er/Yb fiber laser. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 12349–12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Utkin, I.; Fedosejevs, R. Passively Q -switched Ytterbium-Doped Double-Clad Fiber Laser with a Cr4+:YAG Saturable Absorber. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2007, 19, 1979–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Vazquez-Zuniga, L.A.; Lee, S.; Kwon, Y. On the formation of noise-like pulses in fiber ring cavity configurations. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2014, 20, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Huang, K.; Yan, M.; Zeng, H. Experimental study on buildup dynamics of a harmonic mode-locking soliton fiber laser. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 28808–28815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudinin, A.; Gray, S. Passive harmonic mode locking in soliton fiber lasers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1997, 14, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zhao, L.-M.; Zhao, B.; Liu, A. Mechanism of multi soliton formation and soliton energy quantization in passively mode-locked fiber lasers. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 043816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, A.F.J.; Aguergaray, C.; Broderick, N.G.R.; Erkintalo, M. Coherence and shot-to-shot spectral fluctuations in noise-like ultrafast fiber lasers. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 4327–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.