Abstract

We present a theoretical and numerical investigation of a far-field super-resolution dark-field microscopy technique based on longitudinal nano-optical field excitation and detection. This method is implemented by integrating vector optical field modulation into a back-scattering confocal laser scanning microscope. A complete forward theoretical imaging framework that rigorously accounts for light–matter interactions is adopted and validated. The weak interaction model and general model are both considered. For the weak interaction model, e.g., multiple discrete dipole sources with a uniform or modulated responding intensity are utilized to fundamentally demonstrate the relationship between the sample and the imaging information. For continuous nanostructures, the finite-difference time-domain simulation results of the interaction-induced optical fields in the imaging model show that the captured image information is not determined solely by system resolution and sample geometry, but also arises from a combination of sample-dependent factors, including material composition, the local density of optical states, and intrinsic physical properties such as the complex refractive index. Unlike existing studies, which predominantly focus on system design or rely on simplified assumptions of weak interactions, this paper achieves quantitative characterization and precise regulation of nanoscale vector optical fields and samples under strong interactions through a comprehensive analytical–numerical imaging model based on rigorous vector diffraction theory and strong near-field coupling interactions, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional methods.

1. Introduction

Far-field label-free super-resolution (SR) optical imaging has garnered significant interest in biomedical and materials science due to its non-invasive nature, standing in contrast to near-field techniques that require physical probes [1,2] and fluorescence-based SR methods that depend on labeling or specific nonlinear responses [3,4]. However, achieving SR imaging in the far-field regime by directly detecting the linear optical response from sub-diffraction-limited structures without employing evanescent fields, fluorescence, or nonlinear effects presents a formidable physical challenge.

Fortunately, with a great many studies on cylindrical vector beams (CVBs) [5,6,7] considering a range of issues from their special properties to their applications, it is indicated that adopting CVBs in common microscopy has great potential in resolution enhancement such that the diffraction limit can be surpassed, especially with a modulated radially polarized (RP) structured light beam [8,9,10]. Multiple strategies have been developed to engineer RP beams for generating strong longitudinal fields, such as high-aperture focusing via a single annular aperture [11,12], super-oscillatory lenses assisted by multiple subwavelength annular slits [13,14], inherent super-oscillation using higher-order RP beams [15], and pure-phase modulation with binary phase masks [16,17]. Advances in design and fabrication, especially in metasurfaces [18,19], now allow not only the miniaturization of imaging systems, but also precise subwavelength control over light–matter interactions for tailored illumination and detection field shaping. As a result, CVB-assisted super-resolution imaging techniques remain an actively evolving frontier. Existing far-field SR approaches employing modulated RP beams [20,21,22] have primarily focused on system design, leaving the core physics of excitation–sample interaction underexplored. This gap forces most models to adopt an oversimplified weak interaction assumption, neglecting the critical influence of the sample’s local field on its radiative response.

In the field of modern optical super-resolution microscopy, interferometric scattering microscopy [23,24,25] has achieved significant breakthroughs in recent years through point-spread function engineering. Interferometric image scanning microscopy, for instance, combines point-spread function modulation with confocal scanning to achieve label-free imaging at an approximately 120 nm resolution inside living cells [26]. Similarly, approaches integrating PSF shaping with deep learning have demonstrated sub-diffraction-limit resolution in dynamic biological samples [27,28,29]. These advancements primarily focus on enhancing the lateral resolution of weak scatterers in complex biological environments, with their technical frameworks often relying on the specific dielectric properties and dynamic conditions of biological samples. In contrast, this study aims to establish a theoretical model applicable to solid-state nanostructures, focusing on revealing the quantitative mapping relationship between far-field imaging signals and sample geometric morphology, as well as intrinsic physical parameters (such as local density of states), under longitudinal optical field excitation. This provides a theoretical perspective and analytical tool for nanoscale optical characterization in materials science distinct from biological imaging. The core objective of this study is to develop a theoretical model for analyzing solid-state nanostructures, with a focus on revealing the intrinsic mapping relationship between imaging signals and sample geometry, as well as physical parameters (such as local density of states). This provides a complementary perspective for nanoscale optical characterization in materials science.

In this paper, we present a comprehensive dark-field imaging theory for the far-field SR confocal laser scanning microscopy (SR-CLSM) system based on a longitudinal field excitation and detection mechanism (LEDM), fully accounting for complex light–matter interactions. The LEDM entails two key features: (1) the excitation field is dominated by a longitudinally polarized component and (2) only the radiation from longitudinally oscillating dipoles is effectively detected. This is achieved by integrating a polarization converter and an annular aperture into a back-scattering CLSM to provide vector field modulation (VFM) in both illumination and collection paths. Theoretically, we can model nanostructures of arbitrary shape and material using discrete dipole approximation (DDA) [30,31] combined with a volume-integral method [32,33]. The total responding field is constructed from the superposition of all induced discrete dipoles within the structure, driven by the actual local field inside the nanostructure. For detection, the field contribution from each dipole is described via paraxial approximation and linear coordinate transformation, equivalent to the radiation from a free-space dipole at the focus. In the following sections, we detail the imaging theory for this LEDM-based far-field SR microscopy system and present and discuss numerical simulations on label-free samples.

2. Super-Resolution Method via Longitudinal Nano-Optical Field

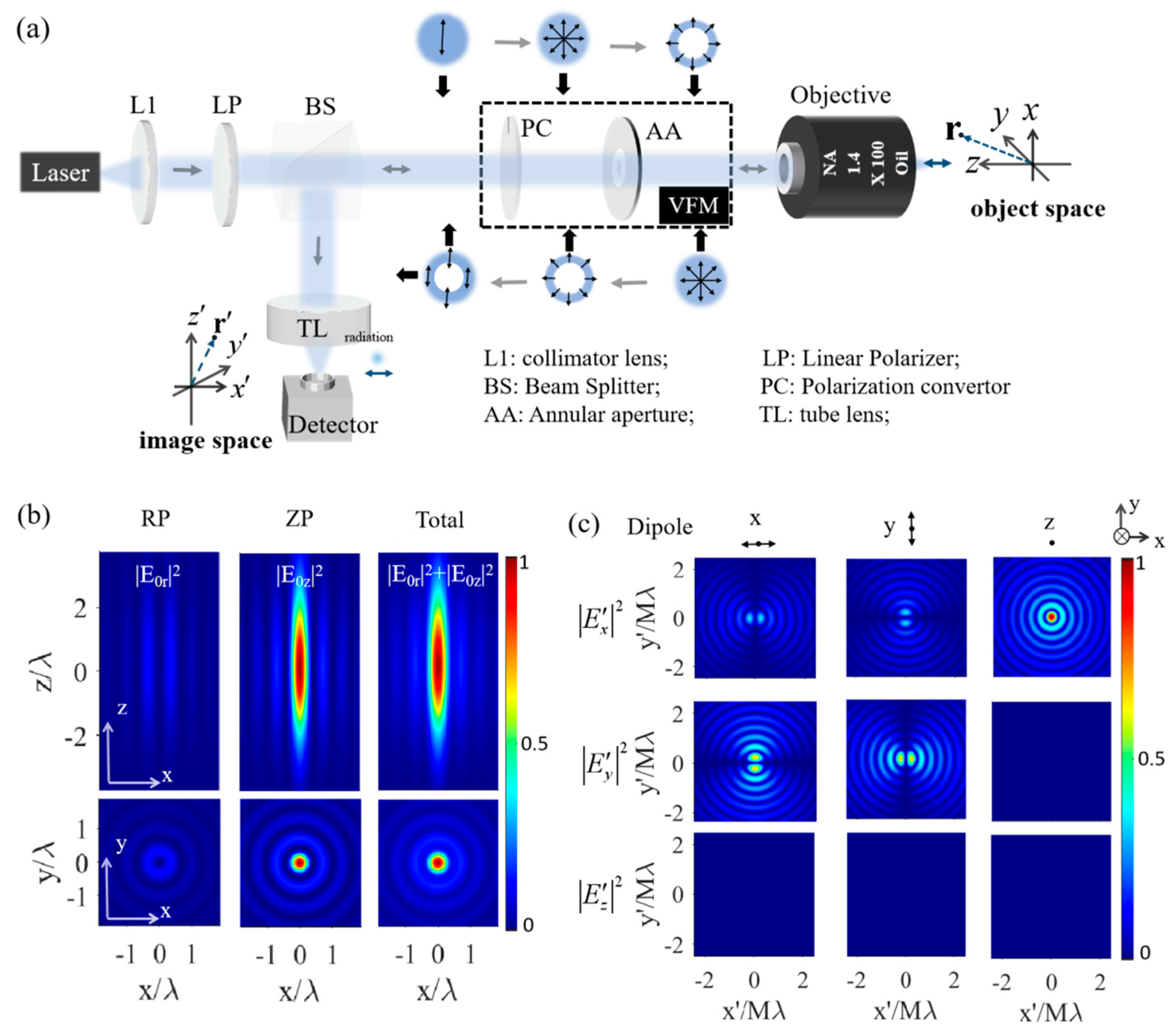

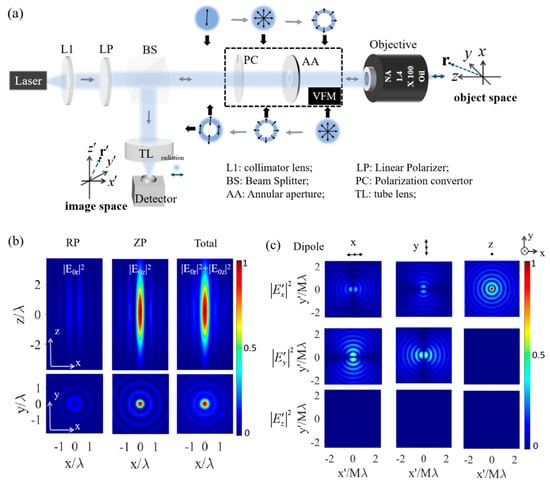

The far-field SR optical dark-field microscopy via longitudinal nano-optical field excitation and detection is implemented by integrating a vector field modulation (VFM) module into a back-scattering confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a high-numerical-aperture objective lens with a long working distance, as shown in Figure 1a. The VFM module consists of a polarization converter (PC) and an annular aperture (AA), which jointly modulate both the illuminating and collected light fields. In the back-scattering working mode, the responding field from the objective can be collected by the same objective lens and then pass through the VFM module. The complete PSF study for an ideal object, such as a free-space vector dipole, has been presented in detail in our previously reported papers [34,35,36,37], with different theoretical derivation and numerical calculation approaches [38,39,40,41]. For excitation with a wavelength of 405 nm, a theoretical lateral spatial resolution below 80 nm can be obtained.

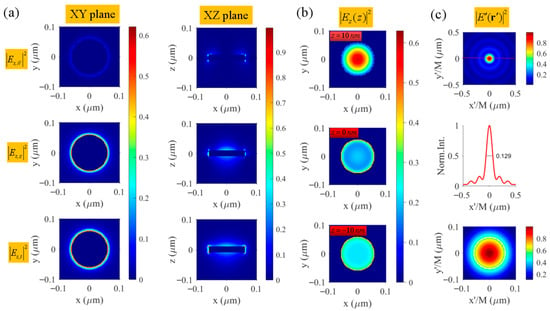

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the super-resolution CLSM. Light-field cross-sections shown above the VFM module are for the illumination path; those below correspond to the radiation collected from a z-polarized (ZP) dipole. (b) Longitudinal (top) and transverse (bottom) cross-sections of the tightly focused light field on the focal plane of the objective lens for its RP component (left), ZP component (middle), and total field (right). (c) Detected field distributions on the confocal image plane for dipole sources oscillating along the x-, y-, and z-directions at the focal point in object space. Here, denotes the excitation/detection wavelength and M is the magnification of the detection system. The arrows marked on the cross-sections of each light spot represent the polarization directions of the optical fields, while the arrows marked along the optical paths indicate the propagation directions of the light.

The size of the longitudinal vector is not solely determined by the oil immersion objective; it is also related to the wavelength of illumination used (a smaller wavelength results in a smaller longitudinal vector size). Additionally, it is associated with the parameters of the annular aperture. A larger duty cycle of the annular aperture (i.e., the ratio of the inner to outer radii) leads to a smaller longitudinal vector size. It is possible to design a metasurface structure that integrates the focusing function of a conventional objective, the filtering function of an annular aperture, and the vector light-field transformation function. Given the flexibility in its parameter design, optimizing these parameters holds the potential to achieve a higher resolution. Experimentally, two nanospheres with a diameter of 80 nm and an edge-to-edge gap of 30 nm can be distinguished from each other [37]. This result confirms that applying VFM in both the illumination and detection paths significantly enhances the resolution compared to systems where VFM is only applied in the illumination [20,21,22].

As demonstrated in Figure 1b, the RP light beam is tightly focused by the objective lens as a light spot laterally with a size of about but as an extended nanoneedle longitudinally with a size of about . From the intensity distribution of the RP component (), ZP component (), and total field (), it is obvious that the total field is dominated by the ZP component. Thus, if ignoring the weak lateral polarized component, the excitation field, , in this system can be approximately regarded as the ZP field, as . This is the mechanism of the so-called longitudinal excitation mechanism in this paper for the VFM-assisted SR-CLSM.

The introduction of longitudinal vector beams can provide the system with a higher resolution compared to a conventional CLSM system. Specifically, the resolution of a conventional CLSM is approximately ~102 nm. By incorporating vector light-field modulation technology—introducing a longitudinal field—under the relevant parameters, the resolution can be improved to approximately ~80 nm. Moreover, by utilizing longitudinal light-field excitation and longitudinal field detection mechanisms, the longitudinal physical properties of the sample can be independently detected while reducing lateral coupling interference between samples. This highlights the differences between the introduction of longitudinal field excitation and detection mechanisms and conventional CLSM.

3. Imaging Theory and Simulation

According to the above analysis, the far-field SR-CLSM via the longitudinal nano-optical field is suitable for exploring the morphology and/or physical properties of a sample with a feature size below the diffraction limit. It also offers a large longitudinal detection range at a certain level, , during a single lateral scanning process across the tightly focused RP beam. With the far-field excitation and detection method, a large workspace is provided. Under no special treatment (such as fluorescence staining), in this Super-Resolution (SR) scheme, sample detection relies solely on the intrinsic response of the sample to the incident excitation light field.. To establish a general imaging theory, a DDA for nanostructures in the sample system is utilized so that its whole response can be regarded as the superposition of all induced dipoles. Since the analytical expressions of the excitation field and the detection Green’s function tensor for this SR system have been derived in detail, the exact analytical description of light–matter interaction is vital, as it relates the excitation and detection processes and contains the sample information.

In some reported papers, the imaging performance of a VFM CLSM is evaluated on the ideal dipole source lattice pattern and some weak interaction patterns [20,21,22], where the complex light–matter interaction between the incident excitation field and the sample is not considered and demonstrated in detail. For such a weak interaction sample, the incident excitation field is usually approximately used as the driving field for a certain position dipole, for which the scattering field from the simultaneously excited nonlocal parts is assumed to be very weak compared with the incident excitation field.

However, when the SR scheme is used to explore a strong interaction sample system, such as a plasmonic system composed of an extended metal structure and/or several densely distributed metal nanoparticles, the dipole–dipole interaction within the sample system may show that they have a strong influence on each other and even on the final image pattern. In order to make the imaging principle better understood, the imaging simulation for lattice arrays composed of ideal dipole sources with identical or modulated response intensity will be first simulated using a weak interaction CLSM imaging theory. Specifically, the weak interaction model refers to systems such as isolated nanoparticle arrays, where the nanoparticle spacing exceeds the constraint condition for dipole spacing (d) in the DDA model, while the nanoparticle size itself is smaller than the constraint condition for d. In such weak interaction systems, the incident field can be approximated as the driving field, and the influence of the scattered field on other dipoles can be neglected. Then, a general theory will be presented and demonstrated on several strong interaction models referring to bulk nanostructures whose dimensions exceed the constraint condition for d, such as the nanodisks and nanotriangles in the paper. These are discretized into small units on the scale of a few nanometers, with each unit approximated as a dipole located at its center.

3.1. Weak Interaction Model

In the LEDM-based far-field SR-CLSM, the detected electric field at the pinhole position for any ZP dipole moment, , at a given position, , can be expressed as [25]. In a weak interaction system, the dipole moment is expressed as , where is the effective polarizability tensor, is the longitudinal component of the focused RP field, and is the Green’s function for the ZP dipole, which only has an x-polarized component. is the vacuum permeability, and is the angular frequency of the incident optical wave.

For isotropic material, its polarizability tensor will degrade into a scalar quantity, . Therefore, the detected signal for each scanning position is proportional to the detected field intensity, , where denotes the infinitesimal detector area. In CLSM, the total PSF is defined as the image of a dipole source that scans through the excitation field. And it can be approximately calculated by . In this SR scheme, if the laser source is supposed as a point source, then . As a result, the image signal of a weak interaction system for a certain wavelength excitation can be approximately expressed as , where is the effective polarizability of each dipole and represents the number of ideal dipole sources. On the basis of this weak interaction CLSM imaging theory, the images of both an identical dipole lattice array and a modulated dipole lattice structure will be calculated. For a certain excitation wavelength, an isolated dipole’s responding intensity is intrinsically represented by its effective polarizability.

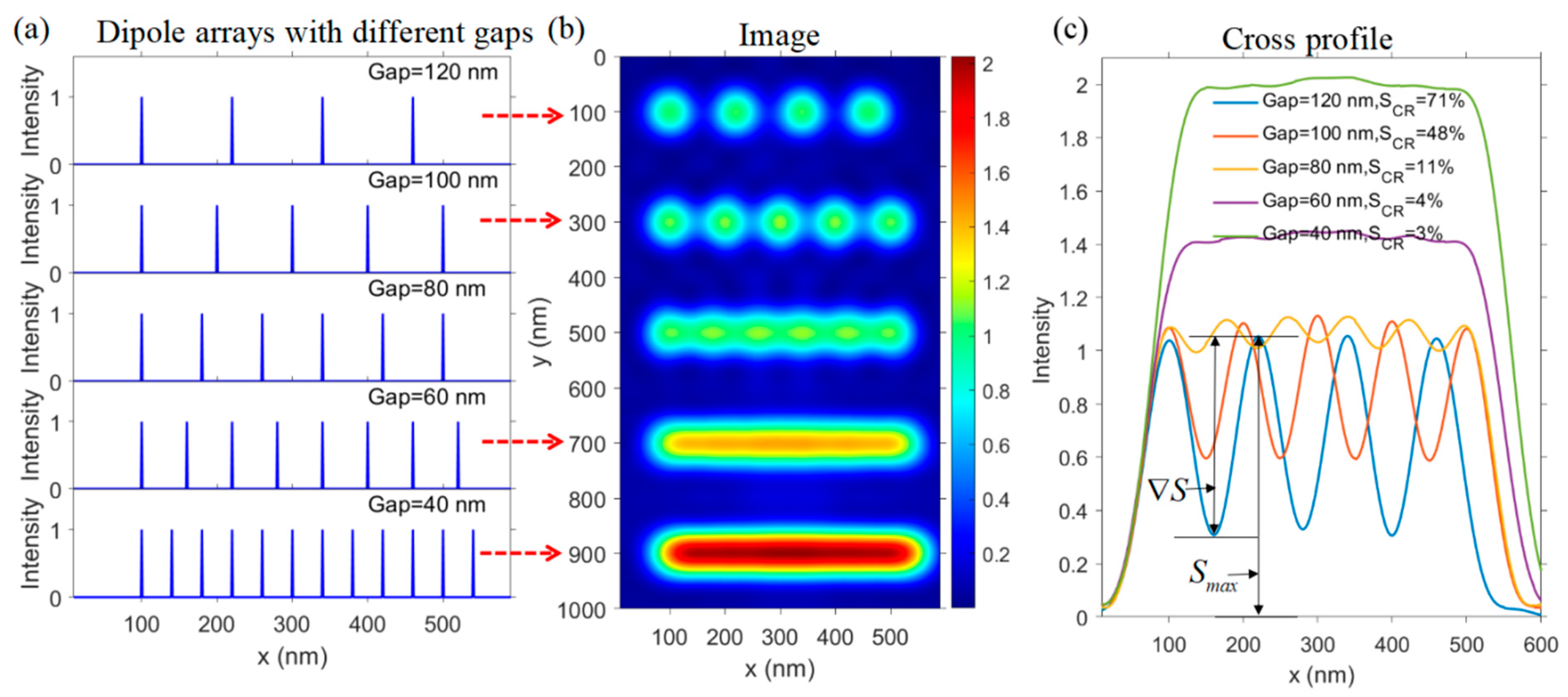

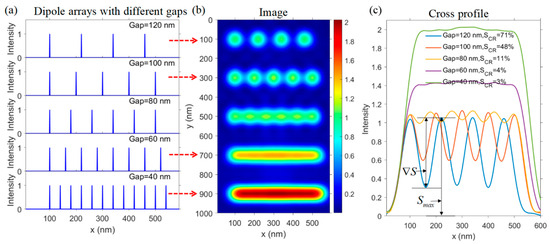

As shown in Figure 2a, five lattice arrays are arranged with different gaps, where each dipole is assumed to be polarized along the z-direction and to have the same polarization intensity. In the simulation, the polarizability is set as a unit: one. In practice, it can be replaced by any practical value. Figure 2b demonstrates the simulated CLSM image for such artificially set dipole arrays. It can be seen that besides the dipoles in the fourth and fifth arrays, all the dipoles in the other arrays can be distinguished from each other. However, with the decreasing gap distance, the signal contrast defined by drops dramatically from to , as shown in Figure 2c, when the gap shrinks from to beyond the resolving limit. For the array that has a gap period below the resolving power of the SR—CLSM, such as or , its imaging pattern looks like a rod, from which the spatially separated dipoles cannot be reversely guessed. At the same time, the whole image intensity is increased by (from 1 to 1.4 for a gap distance of ) and (from 1 to 2 for a gap distance of ), whereas the averaged signal contrast is just at the level of to . From the simulated results, we can see that the diffraction-induced broadening of the dipole image spot and the overlaying among dipole image fields both give rise to the synthetic performance on the final CLSM image.

Figure 2.

The imaging simulation for a series of dipole arrays with an identical dipole moment along the z-orientation but different gaps under the excitation of monochromatic light of a certain wavelength: . (a) Dipole arrays with the gap distance decreasing from 120 nm to 40 nm. (b) Simulated images. (c) Corresponding lateral cross-section profiles through the centers for each dipole array.

After understanding the relationship between the gap distance and the final image information, the influence of the dipole’s response intensity on the final image information will also be explored through simulation, as shown in Figure 3. The response intensity of dipoles in each row is alternately modulated by a factor, , which is defined as the ratio of the response intensity of the even-numbered dipoles to that of the odd-numbered dipoles. Actually, an ideal dipole source does not exist but is proposed for analyzing physical problems. For a practical nanoparticle, it can be approximated as a single dipole or a series of dipoles. The response intensity of these dipoles is generally characterized by the effective polarizability, which is related to its own material composition, geometrical structure, and surroundings.

Figure 3.

Simulated images for non-homogeneous dipole arrays with gaps of and . (a–d) The modulated dipole arrays with a relative intensity of for the even-numbered dipoles in each array. (e–h) Simulated images and (i–l) corresponding lateral cross-section profiles for the modulated dipole arrays.

In Figure 3a–d, each dipole array can be regarded as composed of two sets of identical dipole arrays (a strong dipole array and a weak dipole array) that have twice the period of the original one shown in Figure 2a. From the simulated LSCM imaging results shown in Figure 3e,f, it can be seen that the dipoles in the strong dipole set can be distinguished from each other, while those in the weak set cannot be observed. If compared with the image result of a homogeneous dipole array with gaps of and , the signal from the weak dipoles in each array contributes a considerable background field to the final image, which may reduce the relative signal contrast. From the simulated results, it can be concluded that the dipole’s responding intensity can also influence the final CLSM imaging. The weak responding dipoles cannot be directly perceived through the image pattern.

From the simulated results for the weak interaction sample system, it is shown that the final image is a synthetic result of all parameters in the sample system, including the geometrical pattern and material components. In the next part, a general CLSM imaging theory will be presented and applied to a practical nanostructure with an extended geometrical size.

3.2. General Imaging Model

When the longitudinal nano-optical field excitation and detection-based SR approach is used to explore the extended nanostructure or densely distributed nanoparticles with a feature size below the diffraction limit in terms of their geometrical shape and/or physical property pattern, the dipole–dipole interaction within the sample system should be considered for the diffraction-induced broadened excitation and detection. If the strong interaction sample system is still analyzed using the weak interaction CLSM imaging theory, this may lead to a considerable discrepancy between the simulated image results and the experimental ones. Although the image of any sample can be directly obtained through the experiment, the nanoimaging system may still function like a black box without a complete theoretical analysis.

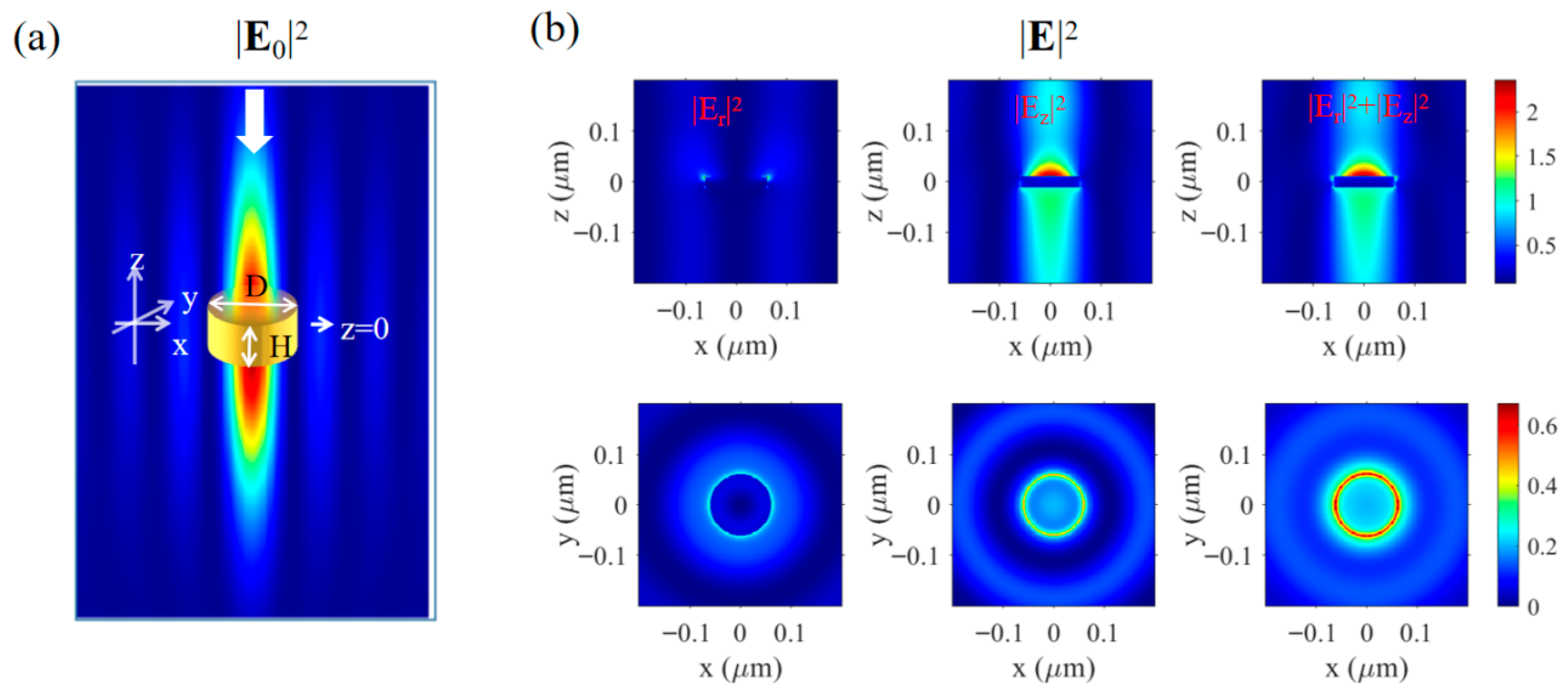

Taking the imaging of a nanodisk as an example, as shown in Figure 4a, the complex light–matter interaction can be analytically expressed by the volume integral equation [25,26] (also called the Lippmann–Schwinger equation):

where , , and respectively denote the position vector, the relative dielectric function inside the nanostructure, and the wavenumber in the vacuum. The integral should be taken over the entire volume of the nanostructure, . And represents the free-space Green’s function that characterizes the field at any position, , generated by an induced dipole at . is the incident tightly focused RP beam. denotes the actual field when the nanodisk is present in the excitation field area, and denotes any position vector in the object space.

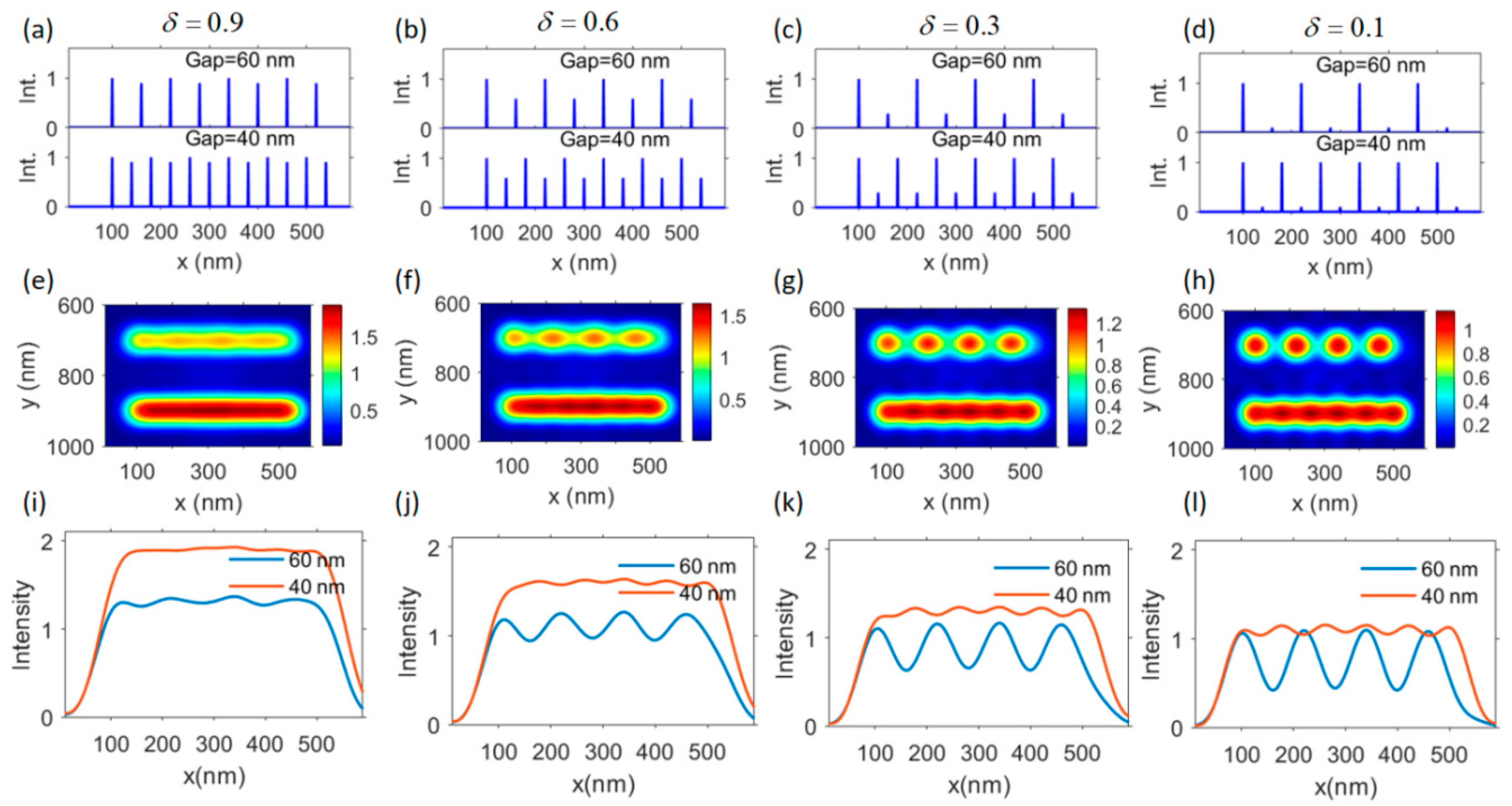

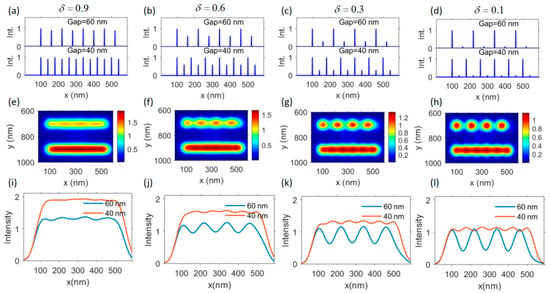

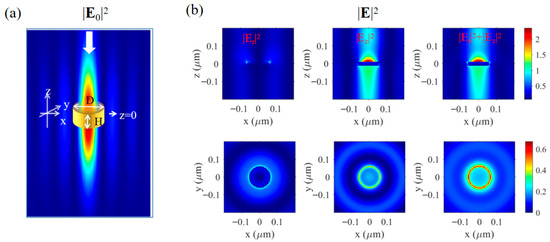

Figure 4.

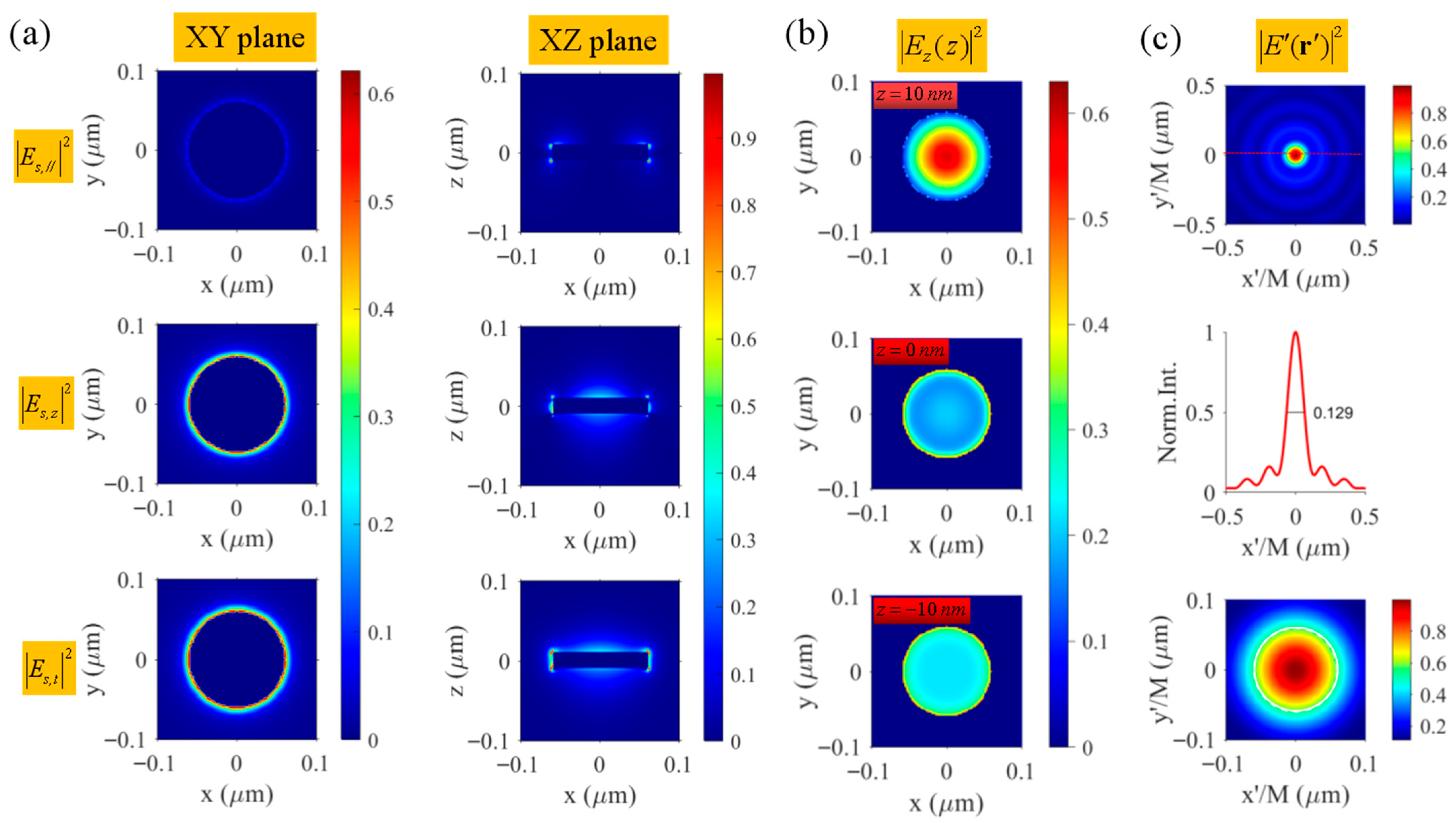

(a) Sketch map of a nanodisk in the excitation field area, the white arrows indicate the excitation light direction. (b) The actual field intensity distribution inside and outside the nanodisk for the RP (radial polarization), ZP (azimuthal polarization), and total fields in the longitudinal (upper) and transverse (lower) cross-sections of a gold nanodisk with a diameter of and a thickness of , whose center is set at the focus position.

Instead of directly solving the interaction Equation (1), which will become a complex equation set if the considered nanostructure is divided into a series of discrete dipoles, a commercial finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) software (Ansys Lumerical 2020 R2 Finite Difference IDE) system is utilized to perform the light–matter interaction. In terms of mesh accuracy, the computational domain employs a non-uniform grid division, with local grid refinement applied to the nanostructures and near-field regions, setting the minimum grid size to Δx = Δy = Δz = 2 nm to ensure accurate resolution of near-field interactions and evanescent waves. Regarding boundary conditions, perfectly matched layer (PML) boundaries are applied in the x-, y-, and z-directions to minimize non-physical reflections. For the light-source setup, a custom source mode is used, generating a nanoscale vector light-field consistent with Figure 1b through programming for excitation, with an excitation wavelength of 405 nm. In constructing the material model, the optical properties (dielectric constants) of all materials are based on experimental data or reliable literature values and defined using dispersion models such as the Drude–Lorentz model. For the determination of the simulation domain and runtime, the computational domain size is set to fully encompass the near-field interaction region. The simulation time is sufficiently tested to ensure that the electromagnetic fields reach a steady state. In the arrangement of near-field monitors, field monitors are placed near the tip of the optical needle and the sample surface to accurately extract the electric field enhancement distribution and near-field–sample interaction information. The longitudinal (upper) and transverse (lower) cross-sections of the actual field intensity distribution are displayed in Figure 4b for the RP (first column), ZP (second column), and total field (third column) components. From the resulting field distribution, it can be seen that the incident excitation field is hardly coupled deep into the inner part of the Au nanodisk. However, the field above the nanodisk shows a more than two-fold enhancement compared to the original incident field.

Combining the scattered field distribution outside the nanodisk, as demonstrated in Figure 5a, which is acquired by removing the incident excitation field, , from the actual local field, , as , we can conclude that the scattered field intensity has nearly reached the level of the incident field in the near area of the Au nanodisk. However, it shows a rapid decline from the near field to the far field in the whole space. Although the excited nanodisk scatters into the whole space, it exhibits an inhomogeneous distribution in different directions, where the backward-scattered field appears to be slightly stronger than the forward-scattered field.

Figure 5.

(a) Scattered field intensity outside the nanodisk along the transverse (first column) and longitudinal (second column) cross-sections for the field components of the lateral-polarized (), longitudinal-polarized (), and total () scattered fields. (b) Actual induced field intensity distribution on the upper surface, central cross-section, and lower surface of the nanodisk. (c) The calculated single-shot image field for the Au nanodisk with a view field range of (first sub-graph) and (third sub-graph). The second sub-graph shows the profile along the red dotted line in the single-shot image field. The white circle added in the third sub-graph denotes the boundary of the nanodisk.

However, in the back-scattering far-field CLSM, only the backward-scattered far field can be partially collected by the detection system. Using the near-to-far field (NTFF) method for the full field on a monitor plane located at a distance beyond half a wavelength from the nanostructure in FDTD simulation, or directly through the volume integral expression, the scattered or radiation field at any position in the object space for the entire excited nanostructure can be written as

where should adopt its far-field form in the far-field area and the near-field form in the near-field area. After being partially collected by the objective lens, the scattered field from the simultaneously excited parts of the sample will subsequently pass through a series of optical modulation devices arranged in the detection system.

As the image field for a free-space-induced vector dipole at focus point has been studied in detail, where it was defined as the detection Green’s function, and in addition to the reasonable assumption of linear translation invariance in the vicinity of focus (several micrometers is reasonable for the working distance of the objective, which is usually beyond one-hand micrometers), the single-shot image field of the actual longitudinal field-induced dipoles in the nanostructure can be calculated by

The single-point response image field represents the single-frame information obtained at a specific scanning position, serving as the fundamental data unit for synthesizing the final scanning image. During the evolution from the scattered field, , in object space to the detected field, , in image space, by combining the longitudinal excitation and detection mechanism in this far-field SR-CLSM, the in Equation (2) is replaced by its longitudinal component, , and the free-space Green’s function tensor, , in Equation (2) is replaced by the detected field component on the confocal image plane for the ZP dipole, , which only possesses the x-polarized component, as shown in Figure 1c (the third column).

Equation (3) indicates that the single-shot image field for a sample can be regarded as the convolution operation between the detected Green’s function and the local-field-induced dipoles inside the sample. As demonstrated in Figure 5b, it is obvious that the induced field at each transverse cross-section inside the nanodisk has a completely different distribution, which depends on the geometrical shape, material elements, and its surroundings, besides the property of the incident excitation field. Moreover, the induced field on the upper surface of the Au nanodisk is much larger than that on other lateral cross-sections. From this, it can be easily predicted in theory that the scattered field above the nanodisk may be stronger than that below the nanodisk, as the oscillation amplitude of the dipole is directly proportional to the actual driving field at the dipole position.

The single-shot image field on the confocal image plane is calculated and demonstrated in Figure 5c. If the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the central image spot is used to characterize the diameter of the golden nanodisk, there is an evaluation error of because the FWHM is about , but the diameter of the nanodisk is about . In confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), a pinhole filter is applied to the single-shot image, and the filtered signal is registered as pixel information. A complete CLSM image is reconstructed by a series of continuously and temporally detected signals at the pinhole, while the sample is raster-scanned through the excitation field. However, it is time-consuming to obtain the CLSM reconstructed image in theory in the same way as in the experiment by point-to-point scanning excitation and detection.

In theory, through a series of derivations, the induced field inside the nanostructure can be directly linked to the incident excitation field via its physical property of local density of optical states (LDOS) [30,34] as

Combining Equations (3) and (4), we can see that the single-shot image field is related to the following parameters: the material components of the nanostructure and its surroundings, which are characterized by the relative dielectric function ; the incident focusing field that is polarized along the z-direction when the sample is absent (for point-source illumination, its intensity can be denoted as ); the effective detection field distribution, , whose intensity is denoted as ; and the physical property, LDOS, in the nanostructure.

By systematically traversing the light needle positions and acquiring the single-frame imaging field corresponding to each position, a complete two-dimensional CLSM image is ultimately synthesized. When the sample experiences a whole displacement vector, , at the scanning to its original position, the corresponding pixel signal can be derived as

It should be pointed out that denotes the position vector of any position inside the nanodisk in terms of the local Cartesian coordinate system that is set at any reference point inside the nanodisk, such as its central position . represents the position vector of the reference point, , in the Cartesian coordinate system that is set at the focus of the objective lens. If the sample is transversely scanned through the incident excitation field near the focus, the final constructed CLSM image can be regarded as the convolution between the total PSF and the product of the relative dielectric function and LDOS.

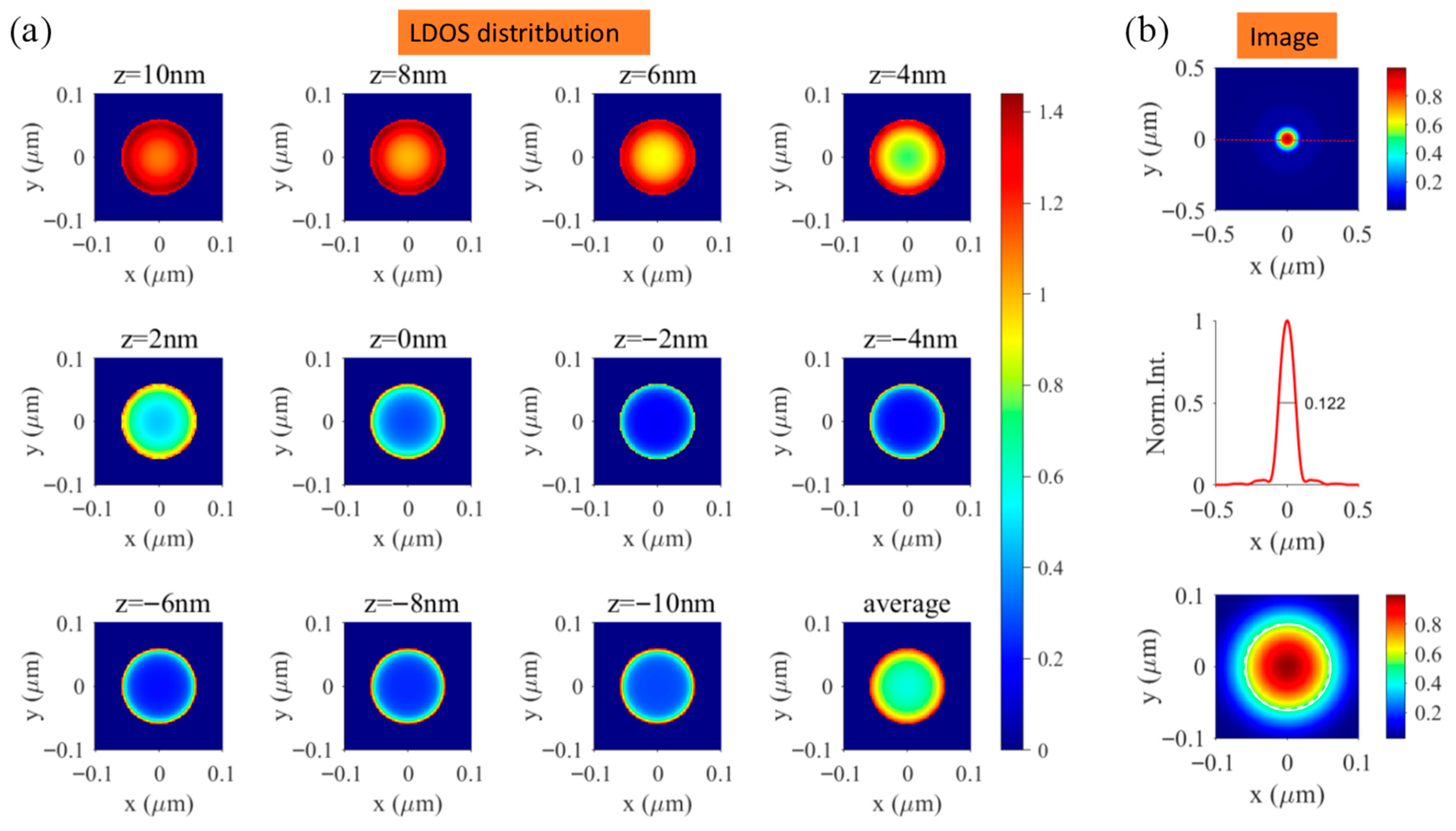

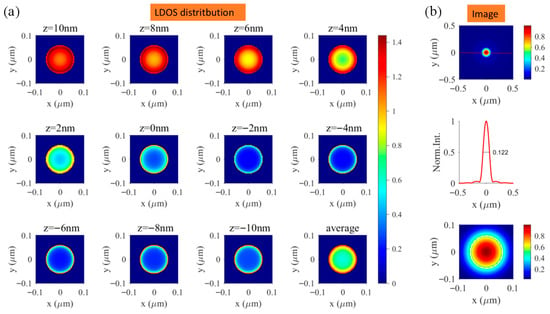

As can be seen in Figure 6a, the local density of states (LDOS) on the upper surface and in several nearby cross-sections, such as at , is overall stronger than that in other cross-sections. Nevertheless, almost all the LDOSs show stronger intensity near the edge area than in the inner parts. The picture at the bottom right of Figure 6a represents the averaged LDOS distribution in the projected transverse plane along the whole thickness direction. The confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) image of the Au nanodisk calculated according to Equation (5) is demonstrated in Figure 6b. Compared with the single-shot image field displayed in Figure 5b, the CLSM image shows better imaging properties, including a higher resolution and lower background. The FWHM of the image spot is evaluated as , which only has an error of with respect to the diameter of the nanodisk. However, the LDOS pattern cannot be resolved from the final CLSM image due to the limited resolving power of the microscopy system.

Figure 6.

(a) LDOS distribution for different transverse cross-sections inside the Au nanodisk. (b) Simulated CLSM image of the Au nanodisk with a view field range of (first sub-graph) and (third sub-graph). The second sub-graph shows the profile along the red dotted line in the single-shot image field. The white circle added in the third sub-graph denotes the boundary of the nanodisk.

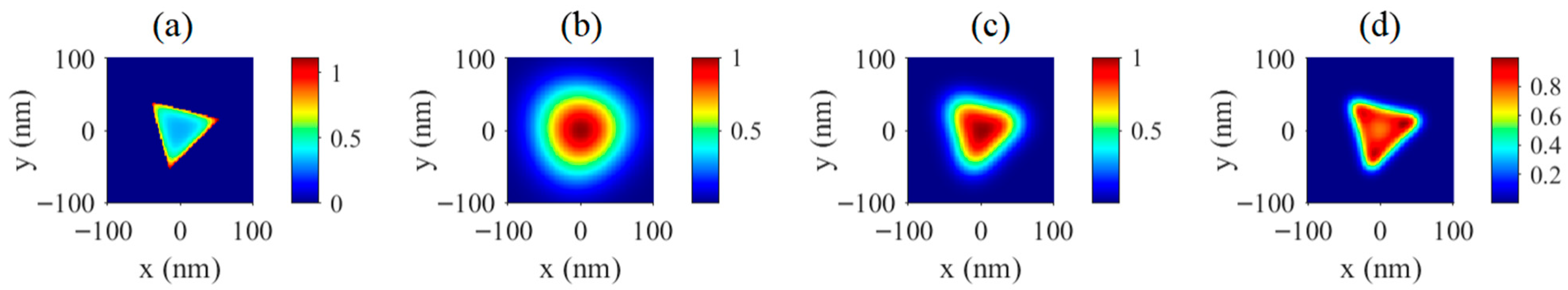

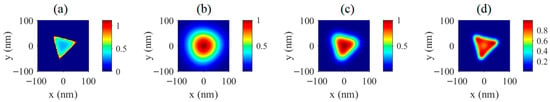

To further resolve the LDOS pattern, not just its projected geometrical shape, a simulation on a nanoprism with an assumed higher resolving power was performed, as shown in Figure 7. In the back-scattering CLSM system that adopts the conventional PC and AA-based VFM, the resolving power is a little better than that with the excitation wavelength of , and all the previous discussion is based on this. However, as mentioned in the Section 1, by adopting a powerful metasurface design and manufacturing method that can provide arbitrary manipulation of the light field as required, a better resolving power can be obtained in the near future, though the research on versatile metasurfaces is not within the scope of this paper. The assumed better resolving powers, such as and , also evaluated by the total PSF of a free-space dipole, are utilized in the imaging simulation for the same excitation wavelength of and the same LEDM. From the simulated CLSM image, it can be seen that all the images in Figure 7b–d appear as a triangle pattern but with different spreads from their geometrical boundaries. And the main features of the LDOS distribution can be distinguished for the case with a resolving power of . It can be speculated that more details can be observed in its CLSM image if a higher-resolution scheme is used.

Figure 7.

(a) Averaged LDOS distribution along the whole thickness direction in the projected transverse plane for a nanoprism with a side length of and a thickness of . The CLSM images of the nanoprism calculated with different system resolving powers: (b) , (c) , and (d) .

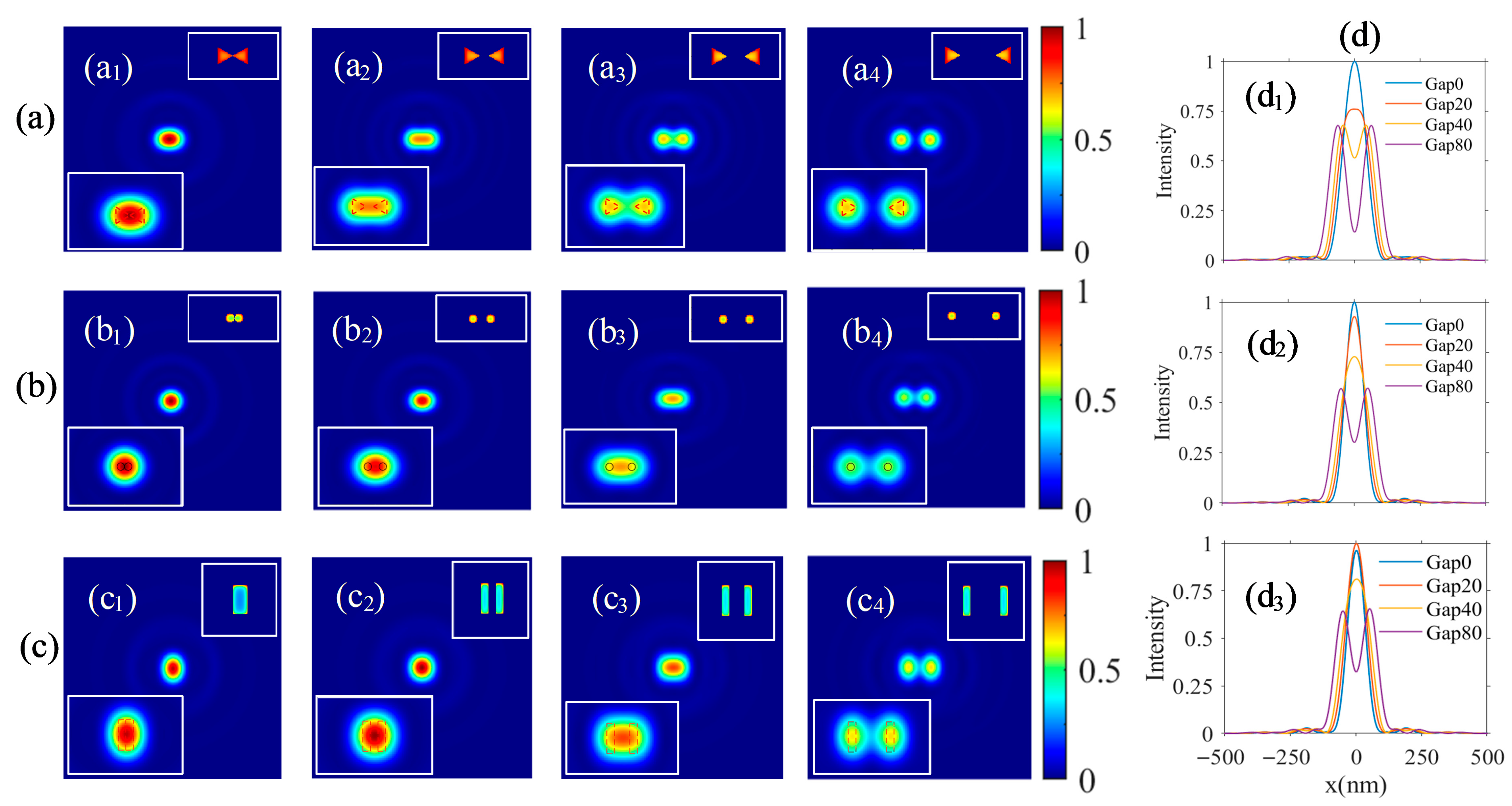

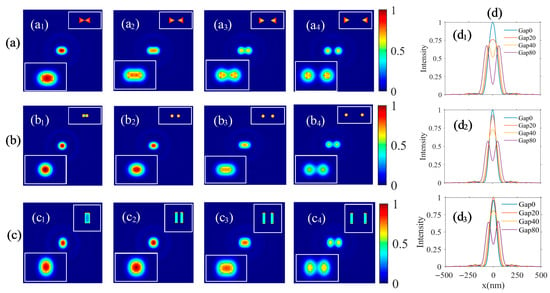

As the general CLSM imaging theory has been presented and demonstrated through a simulation for a nanodisk whose lateral size is comparable to the excitation spot, the geometrical shape can be preliminarily distinguished from its image pattern. However, the more sophisticated pattern of the LDOS distribution cannot be recognized unless the appropriate resolving power is provided, as demonstrated for a nanoprism in Figure 7. In the following section, it will be applied to a nanostructure composed of two smaller nanoparticles with different gaps. From the simulated results, as shown in Figure 8, the two nano-objects cannot be distinguished from each other until the edge-to-edge gap is beyond the resolving power of the system according to the Rayleigh criterion. However, the imaging pattern is also related to the actual geometrical pattern, as in Figure 8(a3,a4), where the two image spots begin to separate from each other when the gap is , and they are separated far beyond the Rayleigh criterion when the gap is beyond the resolving power. In actuality, this system is also applicable to the characterization of dielectric materials, such as silicon, titanium dioxide, and polymer nanoparticles. Naturally, when contrasted with metallic nanostructures, discrepancies may be present in signal intensity and contrast.

Figure 8.

Simulated images for a couple of nanostructures with different gaps and geometrical shapes. (a) Au nanoprism with a side length of and a thickness of ; (b) Au nanocylinder with a diameter of and a thickness of ; (c) Au nanocube with a length, width, and thickness of , , and . The nearest edge-to-edge gap between the two nanostructures is in figure (a1,b1,c1), in figure (a2,b2,c2), in figure (a3,b3,c3), and in figure (a4,b4,c4). The inserted image in the top-right of each map represents the thickness-direction averaged LDOS distribution, and that in the left-bottom of each map displays the magnified image near the nanostructures. Each main picture in (a–c) has a view field of . The maximal image intensity in the first column is normalized to 1, and other maps display the relative intensity. (d) Profiles along the lateral symmetry axis, (d1–d3) corresponding to the nanostructure patterns in (a–c) with varying gap distances between the double nanostructures.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

In summary, the CLSM imaging theory and numerical simulation for the LEDM-based SR far-field method are presented and demonstrated for the weak interaction system and the general system. The CLSM imaging of a practical sample results from multiple factors. On the one hand, there is the diffraction-induced broadened excitation and detection; on the other hand, there are the geometrical landscape, material components, and the nonlocal interaction within the sample system. In the theoretical derivation, the LDOS is introduced to characterize the local response of the nanostructure to the incident excitation field, which is essentially modulated by all its nonlocal parts. Thus, the finally obtained CLSM image may present as the geometrical landscape, the LDOS pattern, or even some other physical properties. Larger feature sizes are easier to resolve, whether in the geometrical landscape or in the physical property pattern.

When the sample surface potential is uniform, electronic states are weakly localized, and the light needle tip state remains stable, the confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) image primarily reflects the geometric topography. In the presence of surface potential fluctuations, strong electron correlation, and excited resonance states, the image can more sensitively reveal the local density of states or material properties. Experimenters can actively adjust key parameters such as sample surface conditions to guide the imaging mode toward revealing specific information (topography or electronic structure), thereby enhancing the direct guiding value of this study for experimental design.

The complete imaging theory presented in this paper can also be applied to other types of far-field SR-CLSM techniques by substituting the excitation and detection Green’s functions. Besides the modulation of the excitation and detection PSF through the microscopy hardware system, the complex light–matter interaction can be another approach to improving the performance of the system. Only dependent upon the intrinsic response of the nanostructure itself, its imaging information may simultaneously contain multiple factors in the sample system. Even though the CLSM image may perform like the geometrical landscape, the physical property pattern, or the synthetic results of multiple factors of the sample, the imaging results do not necessarily reveal a certain type of the required parameters in the sample. However, the theoretically simulated results can offer a reference analysis for the experimental ones. Nevertheless, the theoretically calculated images for various types of samples can be built as an image database to reversely recover the interesting target information from the experimental image with an appropriate post-processing method, such as deep learning-based classification and recognition.

Compared to previous works that primarily focused on system optimization [20,21,22], this study has made substantial theoretical advancements. By utilizing a comprehensive analytical–numerical imaging model grounded in rigorous vector diffraction theory and strong near-field coupling interactions, this research not only discards the idealized assumption of weak interactions but also advances the theory of microscope-based material property characterization for micro- and nanostructures. This provides a novel theoretical foundation for the characterization and design of micro- and nanomaterials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and J.Z.; methodology, A.Z. and K.L.; software, A.Z. and K.L.; validation, A.Z., K.L., and J.Z.; formal analysis, A.Z., K.L., and J.Z.; investigation, A.Z., K.L., and J.Z.; resources, K.L. and J.Z.; data curation, A.Z. and K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., K.L., and A.Z.; visualization, A.Z. and K.L.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z. and K.L.; funding acquisition, J.Z. and K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (2023F050162305233) and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515110658).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hecht, B.; Sick, B.; Wild, U.P.; Deckert, V.; Zenobi, R.; Martin, O.J.F.; Pohl, D.W. Scanning near-field optical microscopy with aperture probes: Fundamentals and applications. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 7761–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, D.; Mescall, R.; You, G.; Basov, D.N.; Dai, Q.; Liu, M. Modern scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy for advanced material research. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahl, S.J.; Hell, S.W.; Jakobs, S. Fluorescence nanoscopy in cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzig, E.; Patterson, G.H.; Sougrat, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Olenych, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Davidson, M.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hess, H.F. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 2006, 313, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, U.; Silberberg, Y.; Davidson, N. Mathematics of vectorial Gaussian beams. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2019, 11, 828–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q. Cylindrical vector beams: From mathematical concepts to applications. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2009, 1, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngworth, K.S.; Brown, T.G. Focusing of high numerical aperture cylindrical-vector beams. Opt. Express 2000, 7, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, W.; Sun, Y. Super-resolution radially polarized-light pupil-filtering confocal sensing technology. Appl. Opt. 2014, 53, 7407–7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.; Pereira, S.; Urbach, P. Confocal microscopy with a radially polarized focused beam. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 29600–29613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, C. High-resolution dark-field confocal microscopy based on radially polarized illumination. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 11066–11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, R.; Quabis, S.; Leuchs, G. Sharper focus for a radially polarized light beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 233901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Noda, S. Sub-wavelength focal spot with long depth of focus generated by radially polarized, narrow-width annular beam. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 4518–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rogers, E.T.F. Sub-wavelength annular-slit-assisted superoscillatory lens for longitudinally-polarized super-resolution focusing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Li, Z.X.; Wu, J.; Hu, Z.-D.; Wang, J. Super-resolution imaging based on radially polarized beam induced superoscillation using an all-dielectric metasurface. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 2780–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozawa, Y.; Matsunaga, D.; Sato, S. Superresolution imaging via superoscillation focusing of a radially polarized beam. Optica 2018, 5, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Lukyanchuk, B.; Sheppard, C.; Chong, C.T. Creation of a needle of longitudinally polarized light in vacuum using binary optics. Nat. Photonics 2008, 2, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, Z.-Q.; Dai, L.-R.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, S.-L.; Wu, Z.-X.; Li, Y.-Y.; Wang, C.-T.; et al. Creation of sub-diffraction longitudinally polarized spot by focusing radially polarized light with binary phase lens. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Chen, H.; Zang, Y.; Duan, H.; Li, Q.; Qiu, M.; Hu, Y. Dielectric metalens for miniaturized imaging systems: Progress and challenges. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, W.J.; Averitt, R.D. Imaging with metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2022, 4, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Wu, B.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Sun, P.; Zheng, S.; Tan, J. Image scanning microscopy with a long depth of focus generated by an annular radially polarized beam. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 39288–39298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozawa, Y.; Sakashita, R.; Uesugi, Y.; Sato, S. Imaging with a longitudinal electric field in confocal laser scanning microscopy to enhance spatial resolution. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 18418–18430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, T.; Huang, W.; Shi, Y. Image scanning microscopy with radially polarized light. Opt. Commun. 2017, 387, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.W.; Mahmoodabadi, R.G.; Rauschenberger, V.; Giessl, A.; Schambony, A.; Sandoghdar, V. Interferometric scattering microscopy reveals microsecond nanoscopic protein motion on a live cell membrane. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Arroyo, J.; Cole, D.; Kukura, P. Interferometric scattering microscopy and its combination with single-molecule fluorescence imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, K.; Guan, G.; Liang, H.; Xie, X.; Zhou, J. Far-Field Super-Resolution Optical Microscopy for Nanostructures in a Reflective Substrate. Photonics 2024, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küppers, M.; Moerner, W.E. Interferometric Image Scanning Microscopy for label-free imaging at 120 nm resolution inside live cells. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtvedt, B.; Helgadottir, S.; Argun, A.; Pineda, J.; Midtvedt, D.; Volpe, G. Quantitative digital microscopy with deep learning. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 011310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, E.; Freedman, D.; Gordon, R.; Ferdman, B.; Weiss, L.E.; Alalouf, O.; Naor, T.; Orange, R.; Michaeli, T.; Shechtman, Y. DeepSTORM3D: Dense 3D localization microscopy and PSF design by deep learning. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Li, J.; Yao, B.; Yang, Z.; Lam, E.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, W.; Qu, J. Enhancing image resolution of confocal fluorescence microscopy with deep learning. PhotoniX 2023, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draine, B.T.; Flatau, P.J. Discrete-dipole approximation for scattering calculations. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1994, 11, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmehl, R.; Nebeker, B.M.; Hirleman, E.D. Discrete-dipole approximation for scattering by features on surfaces by means of a two-dimensional fast Fourier transform technique. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1997, 14, 3026–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, L.; Hecht, B. Principles of Nano-Optics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, O.J.F.; Dereux, A.; Girard, C. Iterative scheme for computing exactly the total field propagating in dielectric structures of arbitrary shape. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1994, 11, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J. Minimized spot of annular radially polarized focusing beam. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 1331–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhou, J. Harnessing the point-spread function for high-resolution far-field optical microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 263901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xie, X.; Zhou, J. Generalized vector wave theory for ultrahigh resolution confocal optical microscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2016, 34, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Zhang, A.; Xie, X.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Liang, H. Far-field and non-intrusive optical mapping of nanoscale structures. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, M.; Rao, R.; Leitgeb, R.A.; Lasser, T. Fast focus field calculations. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 11277–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, O.G.; Kenny, F.; Lara, D.; Dainty, J.C. Fast vectorial calculation of the volumetric focused field distribution by using a three-dimensional Fourier transform. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, R.; Dong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Cai, Y.; Setälä, T. Fast calculation of tightly focused random electromagnetic beams: Controlling the focal field by spatial coherence. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 9713–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viarbitskaya, S.; Teulle, A.; Marty, R.; Sharma, J.; Girard, C.; Arbouet, A.; Dujardin, E. Tailoring and imaging the plasmonic local density of states in crystalline nanoprisms. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.