Abstract

This study examines the evolution of Shannon entropy, a key measure of uncertainty and disorder, in a Laguerre-Gaussian correlated Schell-model (LGcSM) beam under ocean turbulence. We explore how the spatial coherence distribution of the LGcSM beam influences its Shannon entropy in both free space and ocean turbulent conditions. Our results show that tailoring the optical coherence distribution can significantly control spatial disorder, enabling the beam to restore order under turbulence. Furthermore, we analyze the impact of various ocean turbulence parameters on Shannon entropy evolution, offering a potential strategy to mitigate performance degradation in optical communication systems affected by turbulence.

1. Introduction

The amplitude, phase, and polarization of optical fields are well-established tunable degrees of freedom that, when tailored, can produce various physical effects with practical applications [1]. Recently, optical coherence tailoring has emerged as a novel approach to manipulate light fields, enabling the generation of unique physical phenomena [2]. By introducing randomness into a fully coherent beam, its spatial coherence can be significantly reduced, resulting in a partially coherent beam (PCB) [3,4,5,6]. Researches have demonstrated that appropriately controlling the spatial coherence of such beams can not only preserve their inherent advantages but also mitigate the negative effects of high coherence, making them superior to fully coherent beams in certain applications [2].

Initially, spatial coherence studies focused on one-dimensional (1D) distributions, but as F. Gori et al. established conditions for constructing the spectral degree of coherence (SDOC) function of PCBs [7,8], research expanded to 2D spatial distributions. Optical fields with tailored 2D spatial coherence have since shown novel propagation behaviors, with applications in optical trapping [9,10], imaging [11,12], computing [13,14], and encryption [15,16,17]. PCBs are particularly promising for free-space optical communication, where lasers serve as information carriers and free space acts as the transmission medium [18]. This technology offers high bandwidth, low latency, and the advantage of not requiring spectrum licensing, making it a key area of research in next-generation communication systems. Studies have highlighted the anti-interference capabilities of PCBs in random media [19,20], although most focus on beam degradation (e.g., spectral intensity degaussianization, decoherence, depolarization, beam wander and scintillation) rather than the underlying randomness and disorder introduced by turbulence.

While much research on free-space optical communication has centered on laser beams propagating through atmospheric turbulence, little attention has been given to the oceanic environment, which covers approximately 71% of Earth’s surface. Ocean turbulence, driven by temperature and salinity fluctuations as well as water movement, presents significant challenges for beam propagation. In addition to scattering and absorption effects, random refractive index fluctuations are a major factor disrupting underwater optical communication [21]. Therefore, exploring the randomness and disorder characteristics of PCBs in ocean turbulence holds significant theoretical and practical value for advancing underwater optical communication and marine exploration technologies.

Shannon entropy, a key measure of system disorder, can quantify the randomness of an optical field [22]. P. Réfrégier et al. first demonstrated that Shannon entropy could be expressed as a function of intensity, polarization, and coherence [23,24]. Recent studies have focused on the evolution of Shannon entropy for PCBs in turbulent atmospheres, showing that controlling optical coherence can suppress turbulence-induced disorder and enhance spatial correlations [25,26]. Laguerre-Gaussian correlated Schell-model (LGcSM) beams, which possess a 2D spatial coherence distribution, have garnered significant attention due to their distinctive physical properties [27]. These beams exhibit ring-shaped intensity self-shaping, highlighting their potential applications in optical tweezers [28,29]. Additionally, existing research has affirmed their robust resistance to turbulent interference [30,31]. This paper explores the evolution of Shannon entropy in an LGcSM beam as it propagates through ocean turbulence, providing new insights into the role of optical coherence engineering in improving light field propagation quality in oceanic environments.

2. Theory

Shannon entropy is a fundamental concept in information theory, used to quantify the uncertainty associated with random variables [22]. The central idea is that a system’s Shannon entropy increases with disorder and decreases with order. For a discrete random process, where the probability of a given outcome n is , the Shannon entropy of the probability distribution is defined as [32]. For continuous random processes, such as an electric field, the process must first be discretized. The Shannon entropy of the probability distribution of a continuous random process can then be approximated. Let the discretization precision be denoted as . When is sufficiently small, the Shannon entropy of a continuous electric field can be expressed as the following integral,

where is the probability density function of the electric field at the point in space.

PCBs, a special class of structured beams, exhibit randomness at each spatial point [14,33]. As such, these fields cannot be fully characterized by the electric field alone. Instead, they are typically described by the ensemble average of the electric fields at two spatial points and , known as the cross-spectral density function . The normalized version of this function is referred to as the SDOC, , where ∗ denotes the complex conjugate, and represents the spectral intensity distribution [3,34].

Considering a random vector composed of electric fields at spatial points and , if this vector follows a Gaussian statistical distribution, the probability density function of this random vector is given by

where is the polarization matrix of the partially coherent light beam, † denotes transpose conjugation, and is the determinant of the matrix. The Shannon entropy of the PCB can then be simplified to

with e is the natural constant. When the discretization precision is much smaller than the spectral intensity , approximately less than 0.1% of the spectral intensity, the contribution of intensity variation to the Shannon entropy becomes negligible. In this case, the change in Shannon entropy of the PCB is primarily governed by the last term in the equation, which we define as the Shannon entropy difference (SED), . Since the range of the SDOC is , the SED is negative, indicating that the SDOC reduces the total Shannon entropy of the system. The magnitude of this negative contribution reflects how the SDOC suppresses disorder, suggesting that optical coherence engineering can effectively control the spatial distribution and transmission evolution of Shannon entropy in PCBs. This property forms the theoretical foundation for designing light beams with low entropy features.

Next, we focus on a well-known class of PCBs, the LGcSM beam [31]. Unlike traditional Gaussian Shell-model beams, the LGcSM beam exhibits more intricate physical characteristics during propagation, owing to its distinct SDOC distribution. In the source plane (at ), its cross-spectral density function is given by

where the amplitude term represents the Gaussian envelope of the beam, with w being the beam waist width. The SDOC is given by

here, is the nth-order Laguerre polynomial, and is the spatial coherence width. This SDOC determines not only the propagation behavior of the LGcSM beam but also governs the evolution of its Shannon entropy during propagation.

To study the Shannon entropy evolution of an LGcSM beam in ocean turbulence, we invoke the extended Huygens-Fresnel principle. The cross-spectral density function of the beam, propagating paraxially to the target plane, can be expressed as [18]

where and are position vectors on the target plane, is the wave number, and is the wavelength. The term represents the random complex phase perturbation induced by turbulence. The ensemble term, which characterizes the average effect of turbulence, is given by [18]

where , represents the power spectrum of turbulent refracted waves. In this study, we employ the ocean turbulence spectrum as follows [35]

here, , , , and are ocean turbulence spectral constants, , is the kinetic energy dissipation rate per unit mass of fluid, is the mean-square temperature dissipation rate, is the Kolmogorov inner scale, and is the ratio of temperature to salinity fluctuations.

By substituting the cross-spectral density function of the LGcSM source into the extended Huygens-Fresnel transmission formula, and performing the necessary algebraic manipulations, we derive the cross-spectral density function of the LGcSM beam at the target plane

here,

Thus, the spectral intensity on the target plane is given by , and the SDOC is obtained by . By combining the expression for the SED of PCBs with the SDOC at the receiving end, we can analyze the evolution of the SED during the propagation of an LGcSM beam through ocean turbulence. By adjusting the initial parameters of the LGcSM beam, we can control its SDOC distribution during propagation, allowing for effective management of SED. This provides a theoretical basis for enhancing the quality of information propagation using PCBs in complex oceanic channels.

3. Results

This section investigates the evolution of Shannon entropy in an LGcSM beam as it propagates through free space and ocean turbulence, based on numerical simulations. As a representative example of a partially coherent Schell-model beam, the SDOC of an LGcSM beam depends solely on the spatial position difference. For the purpose of subsequent analysis and graphical representation, we will use the spatial position intervals and as the coordinate variables when discussing the spatial distribution and evolution of the SED.

In the numerical calculations presented, the following default initial beam parameters are used: nm, cm, , and cm. The typical ocean turbulence parameters employed are: , , mm, and . Whenever beam or turbulence parameters are varied to examine their effects on Shannon entropy evolution, detailed explanations will be provided.

3.1. Effect of Spectral Degree of Coherence on Shannon Entropy Evolution

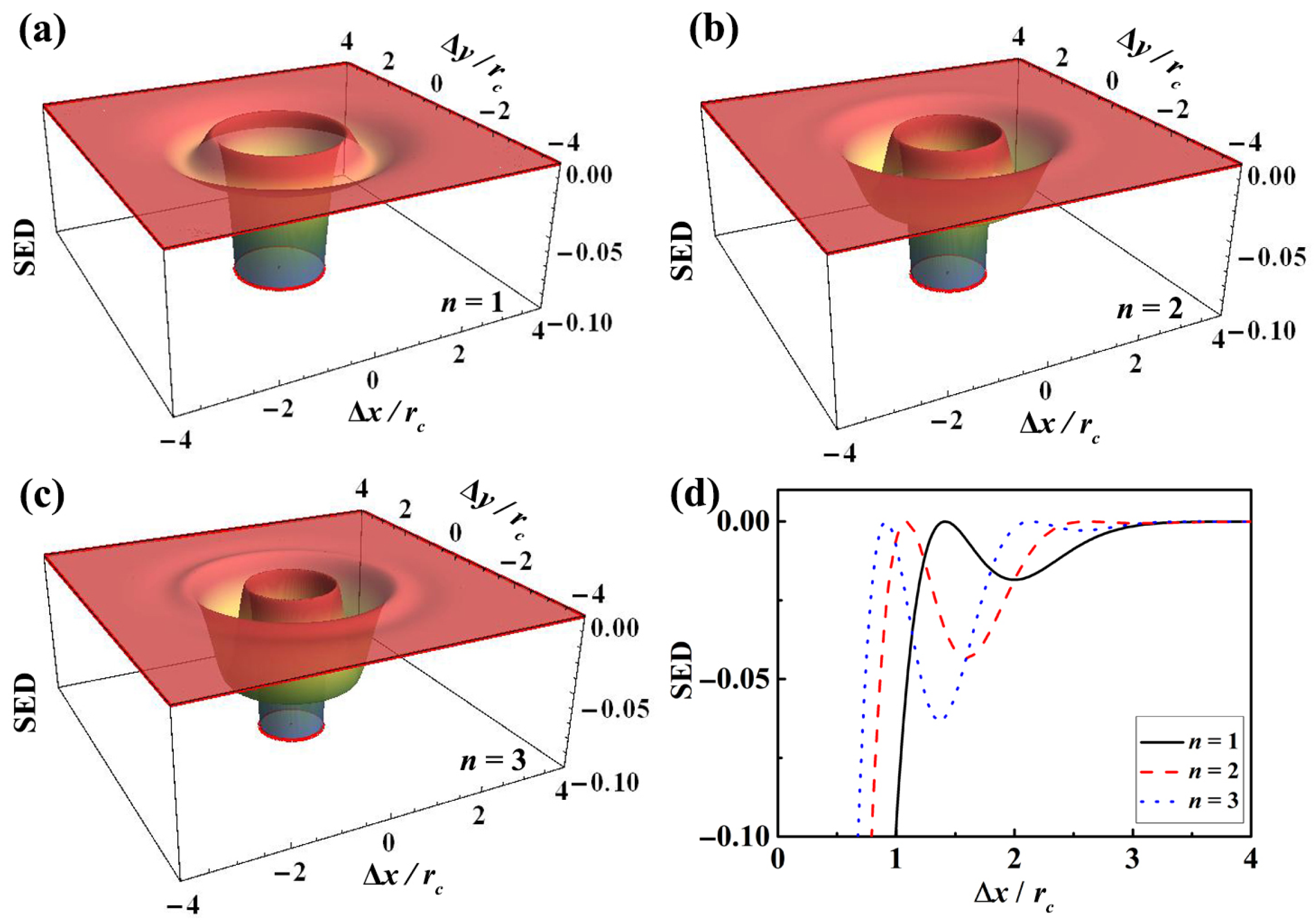

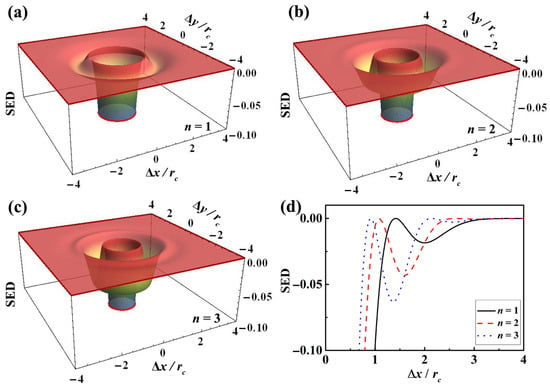

Figure 1a–c display the 3D spatial distribution of the SED for different beam orders. Notably, at the center of the spatial distribution , the SDOC , causing the SED to approach negative infinity. To highlight the effective spatial distribution of the SED, we have truncated the central region where the SED tends to infinity, as this region has limited physical significance. This behavior arises from a fundamental principle in statistical physics: in the limit of perfect coherence, quantum fluctuations cannot be ignored, making the classical statistical expression for Shannon entropy inapplicable at this singularity. Upon comparing Figure 1a–c, we observe that the SED in the source plane exhibits a distinctive concentric ring structure. As the beam order increases, the structure becomes more complex, with a greater number of rings and the appearance of sidelobes with varying amplitudes. For a more intuitive comparison, Figure 1d presents contour plots of the SED for different beam orders. It is evident that increasing the beam order not only adds more rings but also enhances the prominence of the outer sidelobes. This suggests that adjusting the beam order can effectively modify the amplitude and spatial frequency of the ring-shaped SED sidelobes, providing structured control over the beam’s spatial disorder.

Figure 1.

The SED spatial ring distributions representing the disordered characteristics of LGcSM (a) , (b) , and (c) . (d) The corresponding cross-lines with different initial beam orders.

Importantly, the spatial coordinates in Figure 1 are represented by and , indicating that the pattern of the SED distribution depends solely on the beam order, and is independent of the absolute value of the coherence width. The coherence width serves to scale the overall distribution in real space. By adjusting , we can shift the spatial location of the ring-shaped sidelobes, thereby localizing regions with lower SED. Thus, by varying both the beam order and coherence width, the distribution of the SED in LGcSM beams can be customized in multiple dimensions, including the number of rings, the amplitude of the sidelobes, and their spatial locations.

For subsequent quantitative studies of transport evolution, we focus on the SED at a specific point in space. In our numerical simulations, we selected three representative initial beam parameter sets: , , and . These parameter combinations ensure that the first annular sidelobes of the SED for beams of different orders are located at the same spatial reference point P, enabling a fair comparison of their SED evolution in free space and ocean turbulence. In the following discussion, beam order and coherence width will be varied accordingly.

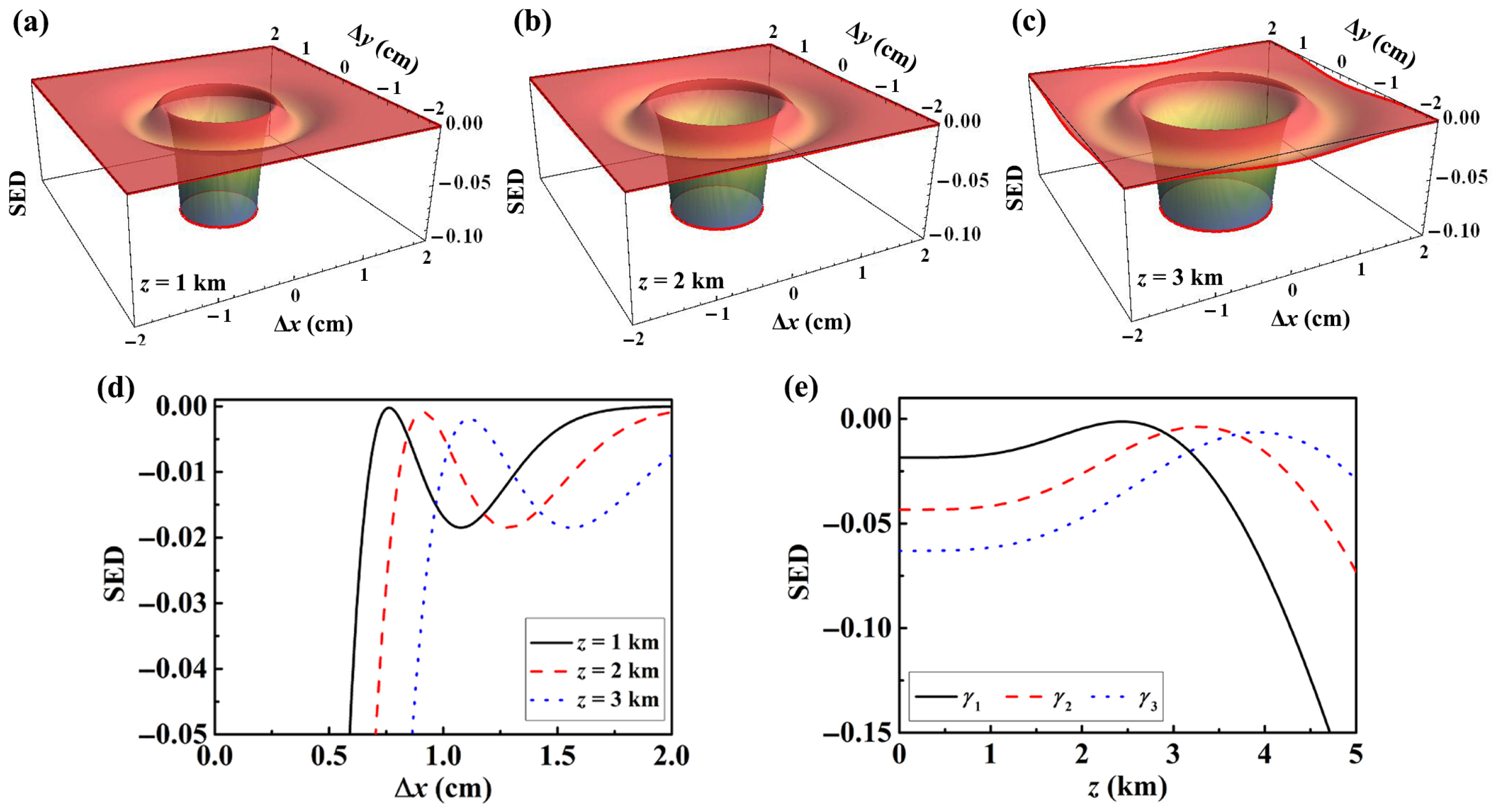

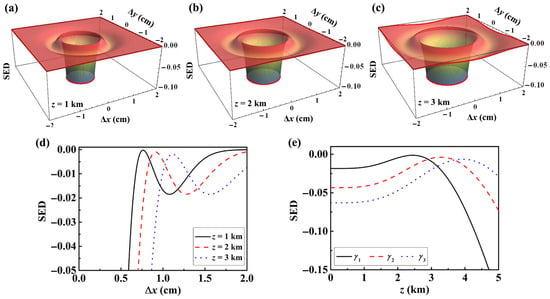

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the SED of an LGcSM beam during free-space propagation, with varying propagation distance and initial beam parameters. Figure 2a–c illustrate the 3D spatial distribution of the SED at different propagation distances, using parameter set as an example. As shown, the characteristic concentric ring-shaped distribution of the SED becomes increasingly diffuse with increasing propagation distance. This visually reflects the redistribution of the beam’s disordered characteristics under the influence of the SDOC during propagation. Figure 2d shows the 1D spatial distribution of the SED at various fixed propagation distances. The analysis reveals that as the propagation distance increases, the peak positions of the ring-shaped sidelobes shift to larger spatial intervals. This shift signifies the redistribution of the beam’s disordered nature during its propagation.

Figure 2.

The SED distributions of an LGcSM beam with beam parameter set in free space at different propagation distances (a) km, (b) km, and (c) km. (d) The corresponding cross-lines of SED distributions at corresponding propagation distances. (e) SED evolution at the reference point P under different beam parameter sets in free space.

To quantitatively capture this evolutionary behavior, Figure 2e plots the SED at a fixed observation point P as a function of propagation distance for different parameter sets. The results show significant non-monotonicity in the evolution of the SED. During short-range propagation, the SED initially increases, with higher-order LGcSM beams consistently exhibiting lower SED values than lower-order beams. This indicates that higher-order beams are more effective at suppressing local disorder in the initial transmission phase. Upon entering the long-range transmission phase, the SED decreases monotonically, with its value becoming more negative. This indicates that the spatial correlation of the beam’s information at point P is reconstructed and enhanced, allowing the beam to recover in this local region, demonstrating a unique disorder-mitigation capability. A comparison of the curves for different parameter sets reveals that while higher-order LGcSM beams achieve lower SED values in the short range, the decrease in SED over long distances may be slightly smaller than for lower-order beams. This is because the LGcSM beam can still maintain a well SDOC distribution over short distances. Nonetheless, after long-distance propagation in free space, the SED at specific locations for all LGcSM beams shows a decreasing trend. This universal phenomenon highlights the inherent ability of LGcSM beams to combat disorder growth during propagation. This characteristic forms the theoretical foundation for exploring their potential performance advantages in complex environments, such as ocean turbulence.

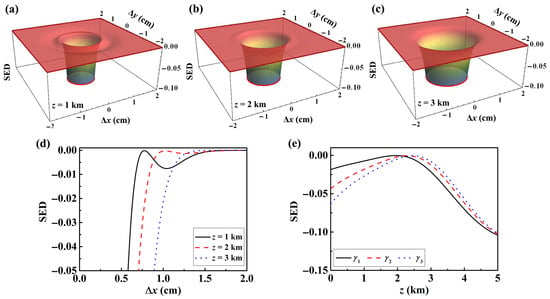

Figure 3a–c show the 3D spatial distribution of the SED of an LGcSM beam with initial parameter set , propagating through ocean turbulence at different distances. At the initial stage of propagation ( km), the beam maintains its characteristic concentric ring-shaped structure. However, as the propagation distance increases, the detrimental effects of ocean turbulence begin to accumulate and dominate the evolution process. The phase distortion caused by the turbulence severely disrupts the initial distribution of the SED, causing the ring-shaped sidelobes to blur and merge. Eventually, the distribution degenerates into a simple Gaussian-like shape. This process visually illustrates the smoothing effect of turbulence on the beam’s spatial information.

Figure 3.

The SED distributions of an LGcSM beam with beam parameter set in ocean turbulence at different propagation distances (a) km, (b) km, and (c) km. (d) The corresponding cross-lines of SED distributions at corresponding propagation distances. (e) SED evolution at the reference point P under different beam parameter sets in ocean turbulence.

The 1D distribution curve of the SED in Figure 3d further quantifies this degradation. As the transmission distance increases, the undulations representing the annular structure (i.e., the SED sidelobes) progressively weaken and eventually vanish, resulting in a smoother distribution profile. This indicates that, under the long-range influence of ocean turbulence, the local low entropy advantage gained by the LGcSM beam through SDOC customization is gradually lost, and the beam’s spatial disorder tends to homogenize overall. Figure 3e presents the evolution of the SED for LGcSM beams with different initial parameter sets at a fixed reference point P as a function of transmission distance. It is evident that, in ocean turbulence, the SED for beams with various initial parameters monotonically increases with transmission distance, approaching zero (i.e., the absolute value of the SED decreases). However, as the propagation distance increases further, the SED begins to decrease monotonically again, highlighting the beam’s ability to mitigate disorder during long-distance transmission.

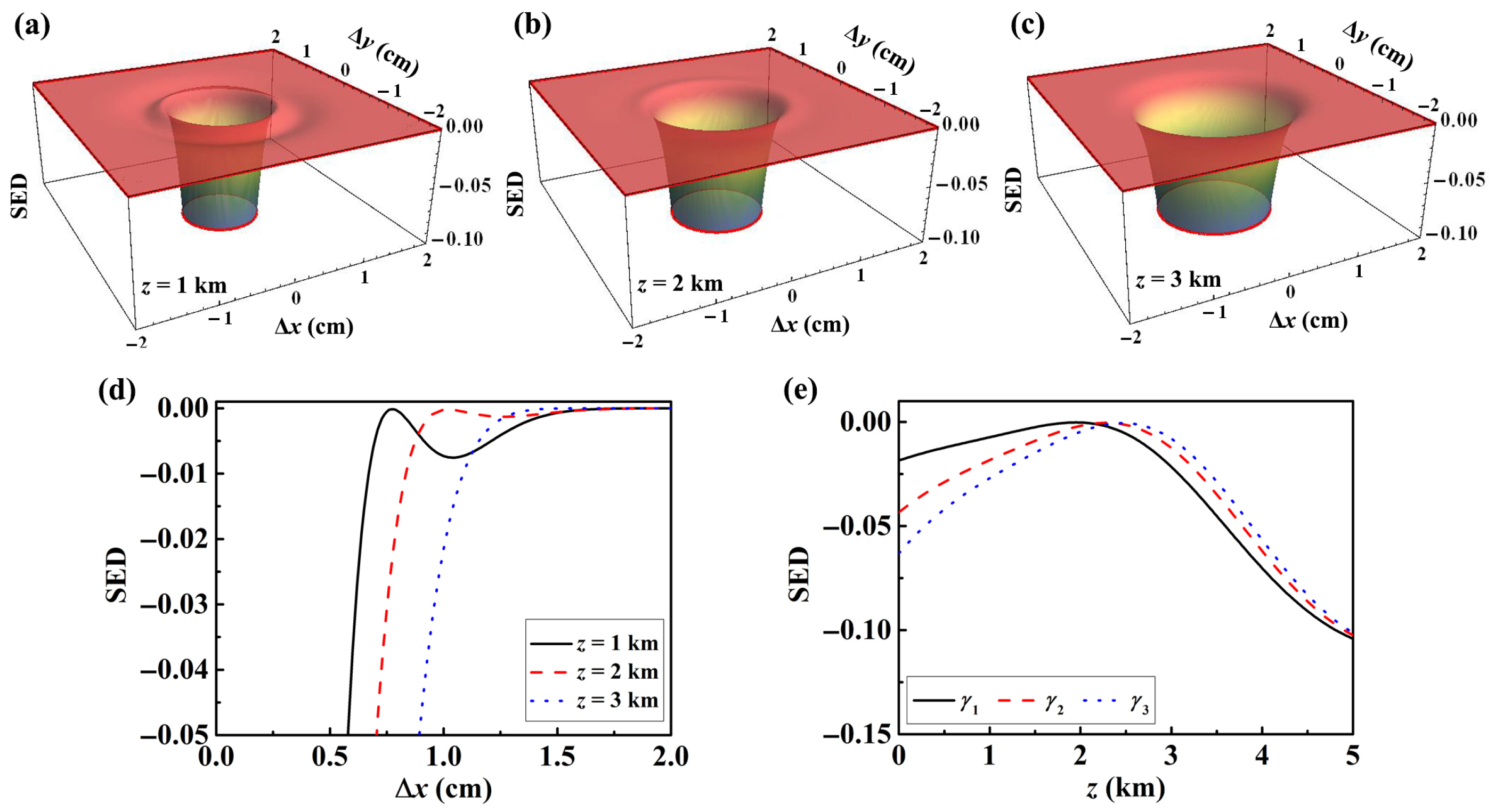

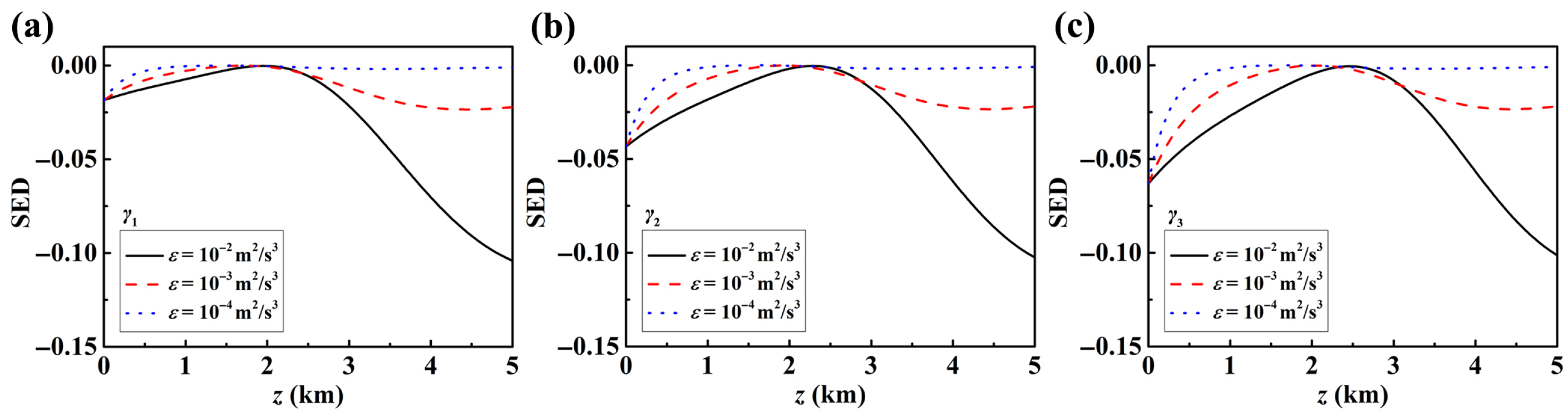

3.2. Effect of Ocean Turbulence on the Shannon Entropy Evolution

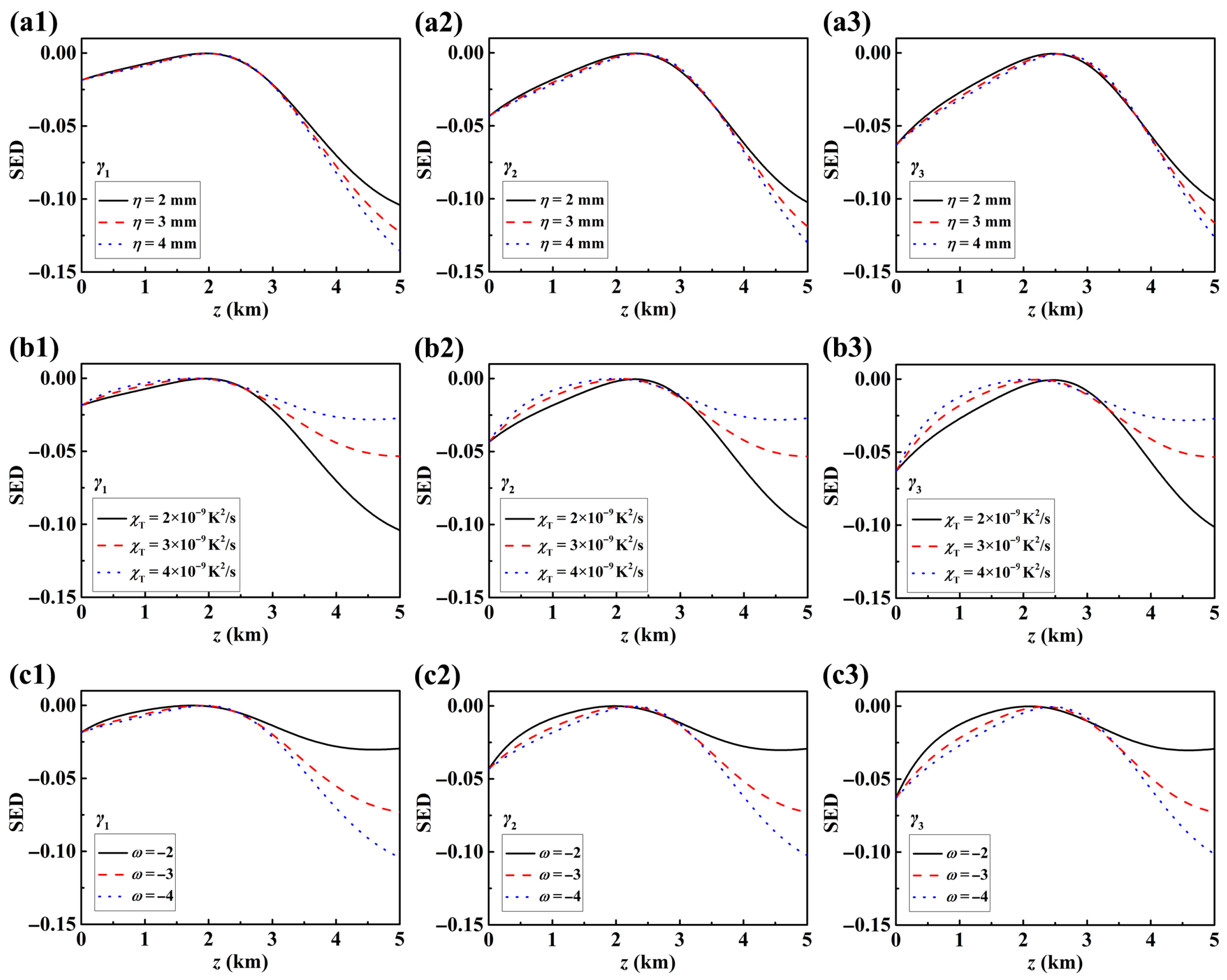

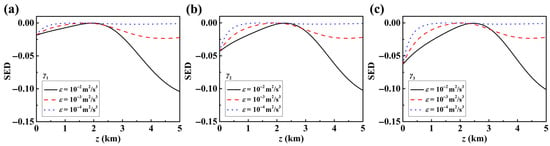

We begin by examining the effect of the kinetic energy dissipation rate per unit mass of fluid, . Figure 4 compares the evolution of the SED for an LGcSM beam with different initial parameter sets in ocean turbulence at varying values of . The results show that significantly influences the behavior of the SED: when is high, the SED fluctuates more dramatically during propagation, whereas, as decreases, these fluctuations become smoother. This indicates that the disorder characteristics of the LGcSM beam are highly sensitive to the kinetic energy dissipation rate, with higher values enhancing the beam’s ability to recover from disorder. A comparison of Figure 4a–c further reveals that in the near-field transmission region, higher-order LGcSM beams exhibit lower SED, while in the far-field region, the SED of beams with different orders converge.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the SED of LGcSM beams for different beam parameters (a) ; (b) ; (c) in ocean turbulence under different .

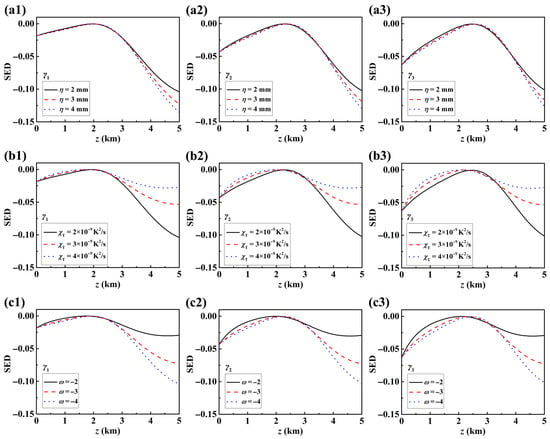

Figure 5 present similar analyses, leading to the following conclusions: in terms of SED, smaller Kolmogorov inner scales , larger mean-square temperature dissipation rates , and higher relative intensities of temperature and salinity fluctuations all significantly enhance the disorder characteristics of LGcSM beams. Specifically, smaller turbulent inner scales cause stronger light scattering, exacerbating the turbulence-induced disorder. Higher mean-square temperature dissipation rates correspond to stronger turbulent energy, further increasing the beam’s disorder. Regarding the relative intensity of temperature and salinity fluctuations, temperature fluctuations dominate when , while salinity fluctuations become dominant when . The analysis indicates that salinity fluctuations have a more substantial impact on the disorder characteristics of LGcSM beams than temperature fluctuations. Therefore, the disorder characteristics of LGcSM beams propagating in shallow-sea regions are more easily mitigated than those in deep-sea regions.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the SED of LGcSM beams for different beam parameters in ocean turbulence under other different turbulence parameters (a1–a3) , (b1–b3) , and (c1–c3) .

4. Summary

We investigated the evolution of disorder characteristics in LGcSM beams propagating through free space and oceanic turbulence. Our results show that the SDOC plays a critical role in the beam’s disorder behavior. While PCBs inherently exhibit some randomness, their specific SDOC helps mitigate disorder growth during free-space propagation. In ocean turbulence, although turbulence exacerbates disorder, PCBs retain the ability to suppress its effects. Notably, at shorter propagation distances, higher-order LGcSM beams are more effective in reducing disorder. However, at longer distances, beams of all orders can still effectively counteract turbulence-induced disorder, highlighting the potential of optical coherence engineering in controlling turbulence effects. Further analysis of SED and its evolution reveals that lower kinetic energy dissipation rates, smaller Kolmogorov inner scales, higher mean-square temperature dissipation rates, and higher ratios of temperature to salinity fluctuations all significantly exacerbate the beam’s disorder in ocean turbulence. Therefore, based on our findings, when designing underwater optical communication systems utilizing PCBs, higher-order LGcSM beams are more suitable for short-distance transmission, while lower-order beams offer advantages for long-distance communication. Additionally, the performance of such systems is notably better in shallow waters compared to deep waters.

Existing studies have established that polarization characteristics influence the distribution of Shannon entropy [23]. It is important to focus on the combined control of both polarization and the SDOC of PCBs and examine their effects on the distribution and evolution of Shannon entropy.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Z.H.; writing—review and editing, R.L. (Rong Lin); conceptualization, J.Y. and Y.C.; methodology, R.L. (Rong Lin); software, R.L. (Ruilin Liu); data curation, W.Y.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration J.Y. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (12192254, 12534014, 12374276, W2441005); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2025ZD21); Qingchuang Science and Technology Plan of Shandong Province (2023KJ198, 2023KJ279); Young Talent of Lifting Engineering for Science and Technology in Shandong (SDAST2024QTA047); Heze University doctoral fund project (XY22BS30).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Forbes, A.; Oliveira, M.D.; Dennis, M.R. Structured light. Nat. Photonics 2021, 15, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y. Research progress on manipulating spatial coherence structure of light beam and its applications. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2023, 91–92, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, L.; Wolf, E. Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics; Cambridge University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, L. Generation of partially coherent beams. Prog. Opt. 2017, 62, 157–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, X.; Yu, J. Research progress on the generation, propagation and applications of spatially coherent structured light fields. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. Sci. 2024, 47, 720–737. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zeng, J.; Cai, Y.; Liang, C. Measurement of optical coherence structures of random optical fields using generalized Arago spot experiment. Opto-Electron. Sci. 2023, 2, 220024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, F.; Santarsiero, M. Devising genuine spatial correlation functions. Opt. Lett. 2007, 32, 3531–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, F.; Ramírez-Sánchez, V.; Santarsiero, M.; Shirai, T. On genuine cross-spectral density matrices. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 2009, 11, 085706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xu, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhu, X.; Gbur, G.; Cai, Y. Longitudinal optical trap and manipulating Rayleigh particles by spatial nonuniform coherence engineering. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 033511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Cai, Y.; Yu, J. Switching of three-dimensional optical cages using spatial coherence engineering. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.N.; Huang, X.; Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. High-resolution three-dimensional partially coherent diffraction imaging. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, B.; Choma, M.A.; Cao, H. Speckle-free laser imaging using random laser illumination. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Shi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Feng, R.; Sun, F.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, C.; et al. Partially coherent diffractive optical neural network. Optica 2024, 11, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Brückerhoff-Plückelmann, F.; Meyer, L.; Dijkstra, J.; Bente, I.; Wendland, D.; Varri, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Farmakidis, N.; Wang, M.; et al. Partial coherence enhances parallelized photonic computing. Nature 2024, 632, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhu, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Gbur, G.; Cai, Y.; Yu, J. Statistically stationary random light for high-security encryption. Optica 2025, 12, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, Y.; Lin, S.; Shao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Peng, X.; Cai, Y.; Yu, J. Optical coherence engineering encryption for secure and robust information transmission. Photon. Res. 2025, 13, B64–B70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, P.; Cai, Y.; Wang, F. Full-dimensional complex coherence properties tomography for multi-cipher information security. Opto-Electron. Adv. 2025, 8, 240278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.C.; Phillips, R.L. Laser Beam Propagation Through Random Media; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gbur, G. Partially coherent beam propagation in atmospheric turbulence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2014, 31, 2038–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Cai, Y. Propagation of partially coherent beam in turbulent atmosphere: A review. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 2015, 150, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, S.A. The Turbulent Ocean; Cambridge University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réfrégier, P.; Morio, J. Shannon entropy of partially polarized and partially coherent light with Gaussian fluctuations. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2006, 23, 3036–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réfrégier, P.; Goudail, F.; Chavel, P.; Friberg, A. Entropy of partially polarized light and application to statistical processing techniques. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2004, 21, 2124–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, R.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lin, R.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, X. Evolution of Shannon entropy of random structured light beams in turbulence. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 21194–21205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Lin, S.; Yu, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, X. Optical spatial coherence-induced changes of Shannon entropy of a light beam in turbulence. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 34086–34094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Korotkova, O. Random sources generating ring-shaped beams. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liang, C.; Hoenders, B.J.; Cai, Y.; Zeng, J. Multiple particles flexible assembly via spatial coherence array engineering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Cai, Y. Twist-and cross-phase-modulated Laguerre-Gaussian correlated Schell-model beam and its radiation forces. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 4803–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, H.; Balhamri, A.; Belafhal, A. Propagation of the Laguerre-Gaussian correlated Shell-model beams through a turbulent jet engine exhaust. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2022, 54, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Zhu, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, F.; Cai, Y. Statistical properties of a Laguerre-Gaussian Schell-model beam in turbulent atmosphere. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M. Elements of Information Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; Chapters 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova, O. Theoretical Statistical Optics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2021; Chapters 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. Introduction to the Theory of Coherence and Polarization of Light; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Chapters 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nikishov, V.V.; Nikishov, V.I. Spectrum of Turbulent Fluctuations of the Sea-Water Refraction Index. Int. J. Fluid Mech. Res. 2000, 27, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.