Abstract

A composite dual-cavity passively mode-locked fiber laser based on a functionalized microsphere resonator is proposed and experimentally demonstrated. The nonlinear response of the resonator is enhanced by depositing TiO2 film on a SiO2 microsphere, which leads to improved mode-locking performance. The wavelength selectivity and optical field confinement of the microsphere resonator are exploited, allowing it to simultaneously serve as an intracavity narrowband filter and a nonlinear modulation element. The threshold of the mode-locked laser was measured to be as low as 34 mW, and stable mode-locked operation was achieved at a pump power of 105.7 mW, with a pulse duration of 2.8 ns, a repetition rate of 13.88 MHz, and a signal-to-noise ratio of 74.86 dB. The output spectrum exhibited a central wavelength of 1560.12 nm, a 3 dB linewidth of 0.06 nm, and a side-mode suppression ratio of 55.13 dB. This straightforward design provides an effective approach for the miniaturization of passively mode-locked fiber lasers.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of laser technology towards miniaturization, high energy efficiency, and simple structure, fiber lasers are gradually replacing the previous bulky solid-state pulsed sources. To satisfy the increasing demands for high stability and high coherence in applications such as medical treatment [1], optical communication [2], and manufacturing [3], various pulsed laser technologies have been developed and widely investigated. Among them, Q-switched lasers typically operate in a regime of high pulse energy and low repetition rate, whereas passively mode-locked lasers (MLLs) generate phase-coherent ultrashort pulse trains at high repetition rates and can serve as seed sources for frequency combs and chirped pulse amplification systems [4,5,6]. In passive MLLs, the high optical power circulating in the cavity accumulates significant nonlinear phase modulation, thereby establishing a fixed phase relationship among the frequency components and enabling stable mode-locking. Traditional mode-locking schemes based on saturable absorbers, nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR), nonlinear amplifying loop mirrors (NALMs), and nonlinear multi-mode interference [7,8,9,10] typically achieve nonlinear accumulation by increasing the cavity length, raising the pump power, or introducing an amplification section. However, these approaches are inherently limited by constraints on cavity length, optical loss, and noise accumulation, which ultimately restrict the properties of the pulse laser.

Whispering-gallery-mode (WGM) microcavities [11,12,13], distinguished for their capability to enhance light–matter interactions within extremely small mode volumes, have found widespread applications in micro-lasers [14,15], sensing [16,17], nonlinear optics [18,19], cavity quantum electrodynamics [20], and non-Hermitian optics [21]. In particular, micro-lasers serve as key light sources in integrated photonics and optoelectronic systems. As a result, micro-resonator-assisted fiber lasers have been widely investigated for pulsed laser generation owing to their strong field confinement and comb-like spectral filtering properties. Peccianti et al. demonstrated a pulsed laser based on a CMOS-compatible high-Q micro-ring resonator exhibiting an ultrahigh repetition rate and narrow spectral linewidth [22]. Wang et al. reported a high-repetition-rate comb laser source using a micro-ring resonator, and the repetition rate can be precisely controlled by adjusting the cavity length [23]. Huang et al. utilized a microfiber resonator combined with high-birefringence fibers to achieve terahertz-repetition-rate pulses. The repetition rate can be tuned by adjusting the birefringence of the fiber using polarization controllers [24]. These approaches primarily focus on generating ultrafast pulses at extremely high repetition rates, which are attractive for applications such as biological imaging and quantum technologies. In contrast to high-repetition-rate schemes, micro-resonator-based fiber lasers have also been explored for stable nanosecond pulse generation, where system robustness, low threshold power, and compactness are of primary concern. Kues et al. employed a micro-ring resonator as the nonlinear element in an NALM-based ring cavity to achieve a stable nanosecond pulsed laser [25]. Nevertheless, most previously reported schemes rely on complex instrumentation or precision coupling schemes, resulting in system complexity and elevated costs. This has driven considerable interest in developing more compact and easily integrated strategies to enhance the nonlinear response of microcavities. In previous studies, other high-nonlinearity materials have been explored for passive mode-locking. For example, γ-MnO2 was incorporated into a dual-core, pair-hole fiber (DCPHF) carrier, enabling ultrafast pulse generation [26]. The results highlight that the integration of functional nonlinear materials into fiber or microcavity platforms can effectively control pulse lasers. Inspired by this approach, coating high-nonlinearity materials onto the surface of WGM microcavities has been regarded as a promising approach. Such configurations effectively strengthen light–matter interactions and facilitate nonlinear optical processes. TiO2 is a material with high refractive index, broadband transparency, and an optical nonlinearity approximately 30 times that of SiO2 [27]. By improving mode field confinement, TiO2 significantly enhances the instantaneous nonlinearity, thereby facilitating mode-locking formation and optimizing pulse properties. Compared with magnetron sputtering, bottom-up growth, and atomic layer deposition techniques [28,29,30], the sol–gel method is favored due to the simple processing, low cost, and excellent film uniformity, offering significant advantages for fabricating composite films [31]. Therefore, integrating a functional TiO2 film coating with a WGM microsphere resonator (MR) represents an effective approach to realize passively MLLs.

In this work, we propose and experimentally demonstrate a composite dual-cavity system based on a TiO2/SiO2 functionalized microsphere resonator (TiO2/SiO2 FMR). This system enables the stable generation of passively mode-locked lasers (MLLs), which is a performance enhancement strategy that has rarely been investigated for FMR-based mode-locking. The TiO2/SiO2 FMR is fabricated by coating a TiO2 film onto the surface of a SiO2 MR. A key feature of this design is that the TiO2/SiO2 FMR simultaneously functions as an ultra-narrowband spectral filter and a high nonlinear modulation element. Moreover, the strong optical field confinement promotes the formation of mode-locked pulses. The influence of the TiO2 film on the output characteristics of the laser is also investigated. Experimentally, stable MLL is achieved without auxiliary components, producing pulses with a pulse duration of 2.8 ns, a repetition rate of 13.88 MHz, and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 74.86 dB. The wavelength optical laser emits at 1560.12 nm with a 3 dB bandwidth of 0.06 nm and a side-mode suppression ratio (SMSR) of 55.13 dB. Moreover, the mode-locking threshold is 34 mW. This approach offers an effective route toward compact and miniaturized pulsed laser sources and provides new insights into mode locking enabled by material and microcavity-assisted field manipulation.

2. Experiment Setup

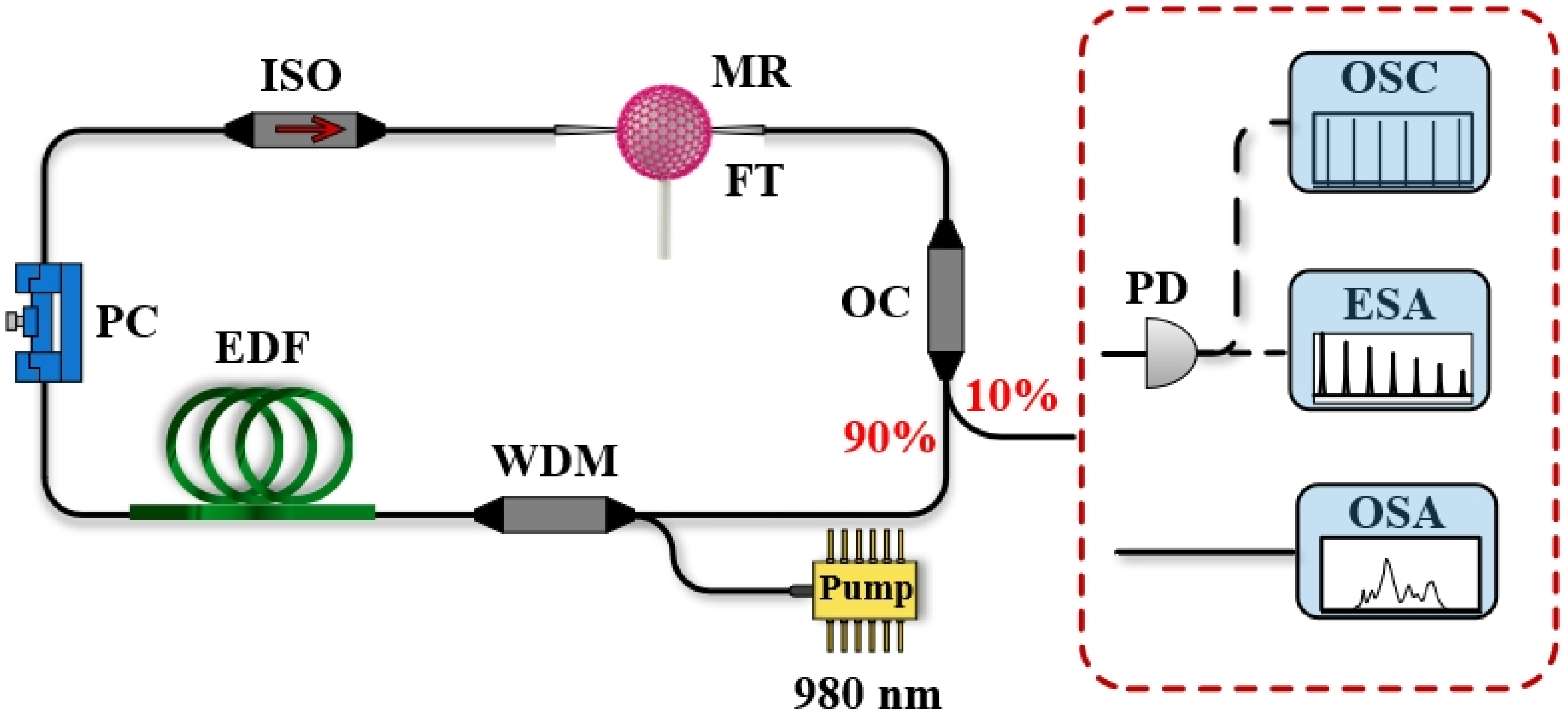

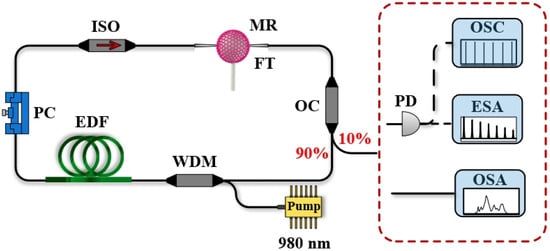

The configuration of the composite dual-cavity passive MLL based on TiO2/SiO2 FMR is shown in Figure 1. The laser employs a ring-cavity structure. A 980/1550 nm wavelength-division multiplexer (WDM) is used for pump coupling, and a 2.3 m single-mode erbium-doped fiber (EDF, Nufern, EDFL-980-HP, East Granby, CT, USA) serves as the gain medium. A polarization-independent isolator (ISO) is inserted to isolate the reflected light from the TiO2/SiO2 FMR and ensure the unidirectional propagation of the light. A polarization controller (PC) is inserted to adjust the intra-cavity polarization state. The 980 nm pump is provided by a laser diode. The TiO2/SiO2 FMR is incorporated into the main ring cavity via a fiber taper (FT), where it functions simultaneously as a nonlinear modulation element and a narrowband spectral filter. The output laser is extracted from the 10% port of the OC, and the 90% port is used as the cavity feedback to maintain the operation of the laser. The experimental results are measured by an oscilloscope (OSC, Agilent, DSO9254A, Santa Clara, CA, USA), an optical fiber coupling power meter (Thorlabs, S145C, Newton, MA, USA), a spectrum analyzer (OSA, Yokogawa, AQ6370D, Tokyo, Japan), and a radio frequency analyzer (ESA, Agilent, N9030A, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Structure of the composite dual-cavity system passive MLL based on TiO2/SiO2 FMR.

3. Fabrication and Properties of TiO2/SiO2 FMR

3.1. Fabrication of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR

A TiO2 film is synthesized by the sol–gel method and coated onto the surface of the SiO2 MR, forming the TiO2/SiO2 FMR with enhanced optical nonlinearity. The SiO2 MR is fabricated by producing a fiber-stem integrated microsphere through a localized arc-melting technique. A standard single-mode fiber is tapered to form a single-ended FT with a length of 4–6 cm. The tapered tip is melted using a modified fusion splicer, and a microsphere is formed under surface tension.

The TiO2 sol is prepared by mixing titanium butoxide (8.5 mL, Shanghai Meryer Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with anhydrous ethanol (20 mL, Chengdu Jinshan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) to form Solution A, and glacial acetic acid (5 ml, Tianjin Beilian Fine Chemicals Development Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) with 95% ethanol (22.5 ml, Chengdu Jinshan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) to form Solution B. Solutions A and B are combined at room temperature, magnetically stirred for 4 h, and aged for 12 h to obtain a homogeneous colloid. The cleaned SiO2 MR is then immersed in the TiO2 sol for 5–10 min and baked at 160 °C for 10–15 min for preliminary curing. A subsequent densification process using electrode discharge produces a TiO2/SiO2 FMR with a smooth surface.

Finally, a 2–3 cm section of coating on a single-mode fiber is removed and cleaned, and an FT with the diameter of 1–4 μm is fabricated using a precision tapering system (XQ7170-B04, Shenzhen OSCOM Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) based on a single-point heating and pulling technique.

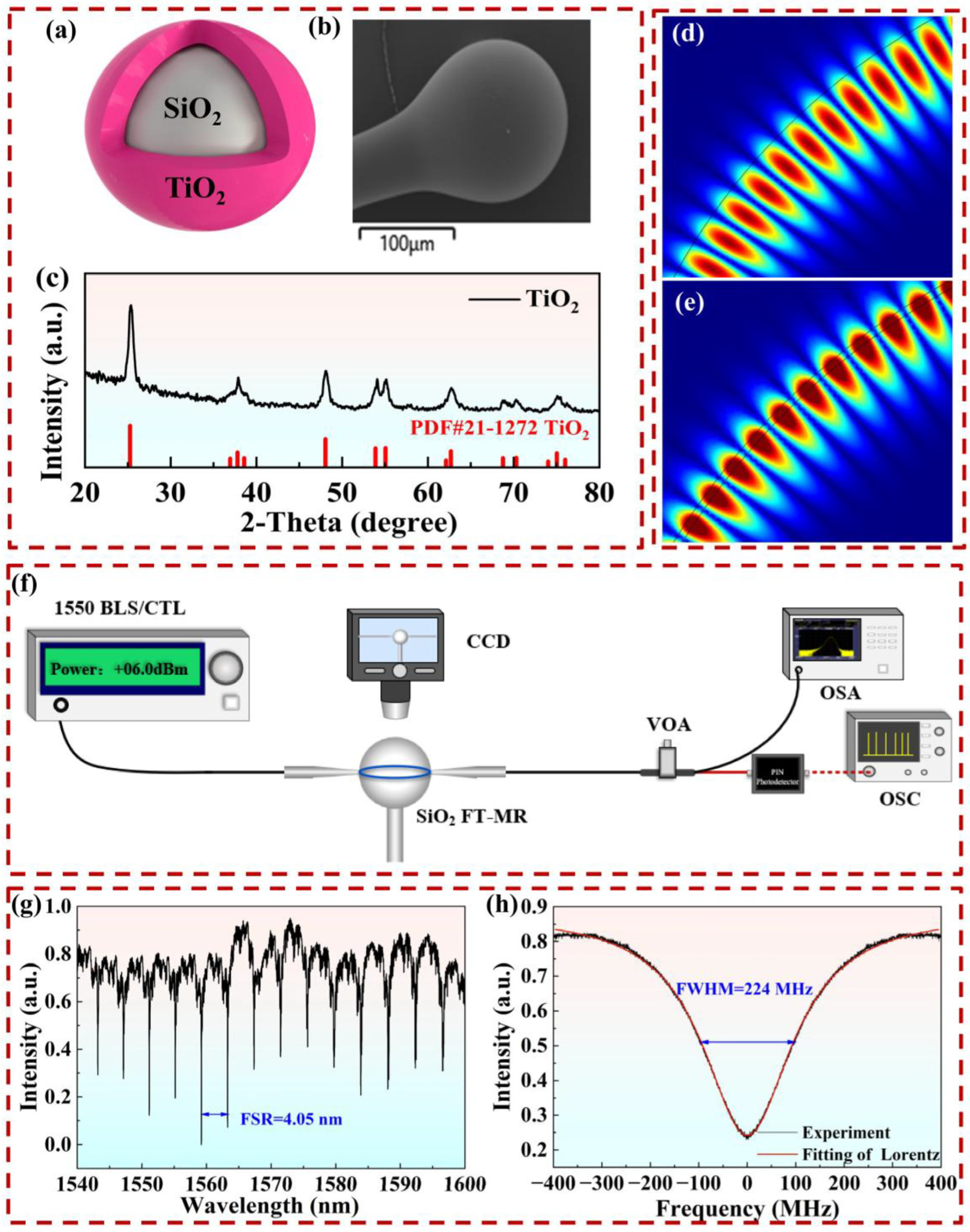

3.2. Properties of TiO2/SiO2 FMR

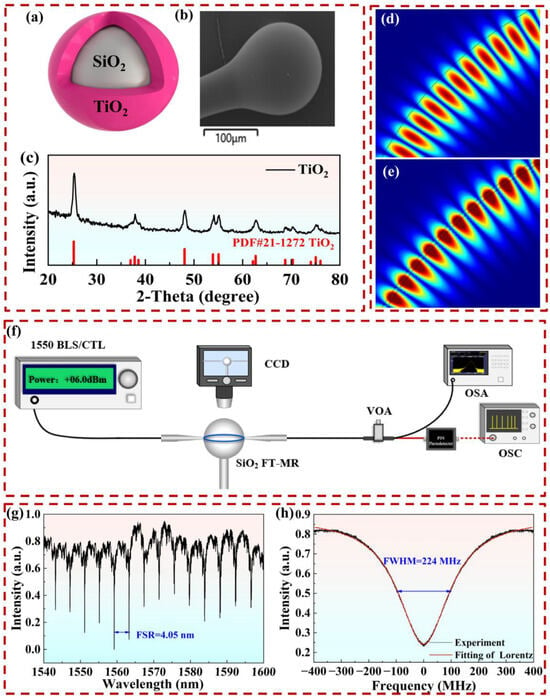

The performances characterization of TiO2/SiO2 FMR is presented in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows the structure of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR. Figure 2b indicates that the diameter of the microsphere is about 128 µm, and the layered structure of the TiO2 film can be clearly seen. To further confirm the characteristics of TiO2 films, X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrum is measured, as shown in Figure 2c. To gain deeper insight into the influence of the TiO2 film on the optical-field distribution, finite-element simulations based on COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 are performed. Figure 2d,e show the simulated optical field distributions of SiO2 MR and TiO2/SiO2 FMR (a wavelength of 1550 nm, a refractive index of 2.19, and a TiO2 film thickness at 100 nm), respectively. The results indicate that the optical field in the TiO2/SiO2 FMR is more strongly confined near the equatorial region within the TiO2 layer, thus resulting in enhanced nonlinearity and improved modulation capability of the laser.

Figure 2.

Performance characterization of TiO2/SiO2 FMR. (a) TiO2/SiO2 FMR structure. (b) SEM image. (c) XRD pattern. (d) Optical field distribution of SiO2 MR. (e) Optical field distribution of TiO2/SiO2 FMR. (f) Experiment setup. (g) Filtering characteristic. (h) Q value measurement.

Additionally, the optical properties of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR are measured. The transmission spectrum of 128 μm TiO2/SiO2 FMR is recorded using a broadband light source. In Figure 2f, a broadband light source (Hoyatec, SLED, BLS, Shenzhen Hoyatek Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China) is used as pump source. The coupling system between the FT and the MR is monitored in real time by a microscope (CCD, 1200×). The transmitted light signal is adjusted using a variable optical attenuator (VOA, Shenzhen MC Fiber Optics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and subsequently analyzed by an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA, AQ6370D, Tokyo, Japan). The results show that the free spectral range (FSR) is 4.05 nm, and a periodic WGM distribution is observed, exhibiting a typical comb filter characteristic, as shown in Figure 2g. Figure 2h presents the characterization of the Q factor, which is measured by scanning the frequency of a tunable laser at 1550 nm. The observation process is shown in the red line of Figure 2f. The broadband light source (TOPTICA CTL 1550, Graefelfing, Germany) serves as the pump source, which is coupled through a MR-FT system and connected to an oscilloscope (OSC, Yokogawa, DLM2034, Tokyo, Japan) via a photodetector (PD, Newport, RI, USA). According to the formula (where is the resonance frequency and is the Lorentz linewidth), the measured resonance linewidth of 224 MHz corresponds to a Q factor of approximately 8.6 × 105.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Output Performance of the MLL

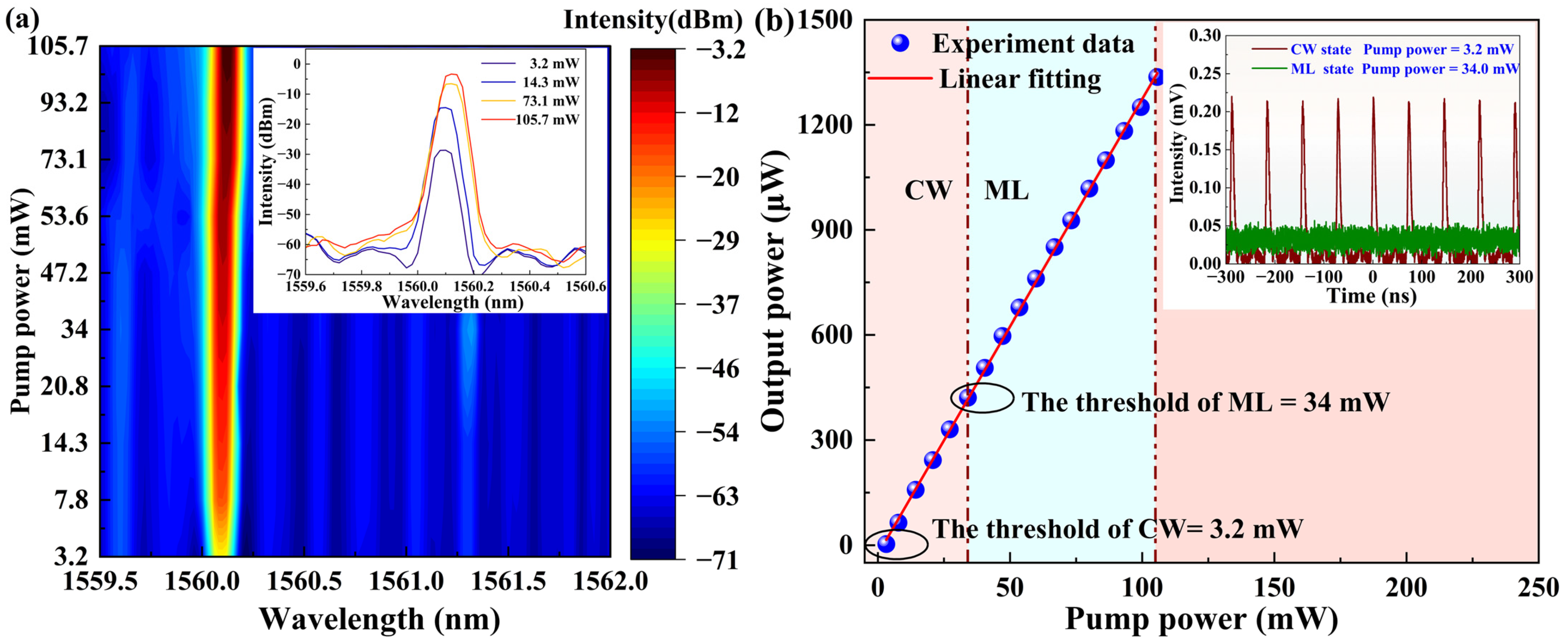

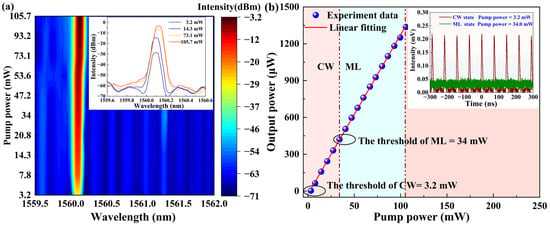

A TiO2/SiO2 FMR with a diameter of 128 μm and a resonance linewidth of 224 MHz is inserted into the main ring cavity, which has a total length of 14.4 m, corresponding to a repetition rate of 13.88 MHz. Therefore, a maximum of 16 longitudinal modes of the main ring cavity can oscillate within a single TiO2/SiO2 FMR resonance. By finely adjusting the PC and gradually increasing the pump power, both continuous-wave (CW) and pulsed states are achieved. Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the laser with increasing pump power. Figure 3a depicts the influence of pump power on the output spectrum. As the pump power increases from 3.2 mW to 105.7 mW, the spectral center remained at approximately 1560.12 nm, while the output intensity increased. The inset illustrates the spectral evolution at different pump powers, showing a clear increase in peak intensity accompanied by a slight redshift of the central wavelength. These results indicate that the intracavity mode selection is stable and there is no observable mode hopping. In the future, methods such as optimizing the microcavity materials, introducing a temperature control system, and applying active frequency locking techniques can be employed in real time to compensate for frequency deviations, thereby further enhancing the stability of the system [32,33,34].

Figure 3.

Evolution of laser operation as a function of increasing pump power. (a) Variation of spectral intensity with pump power. (b) Transition of laser state.

The evolution of the laser states with increasing pump power is shown in Figure 3b. As the pump power increases, CW lasing is first observed with a threshold of 3.2 mW. For pump powers below 34 mW, only continuous noise is recorded on the OSC, indicating that the system remained in CW operation. When the frequency difference between the main-cavity longitudinal modes and the WGMs is less than half of the resonance linewidth of the MR, mode resonance in the composite dual-cavity system is established. The main-cavity modes effectively fell within the resonance window of the MR and are cyclically amplified, achieving laser emission. However, the intracavity energy is initially too low to excite the nonlinear effects, and the system remains in the CW state. As the pump power is increased to 34 mW, the intracavity energy reaches the threshold for the Kerr effect, triggering the transition from CW to pulsed operation. Within the pump range of 34 to 105.7 mW, highly stable and periodic pulse trains are observed on the OSC, indicating the system remained in a stable mode-locked state. In this regime, further increases the pump power enable Kerr-induced dynamic compensation of small mode detuning between the two cavities. This compensation allows coherent superposition of multiple longitudinal modes and leads to the formation of low-loss mode-locked pulses. When the pump power exceeds 105.7 mW, the compensation is insufficient to overcome the mode detuning, and mode-locking is disrupted.

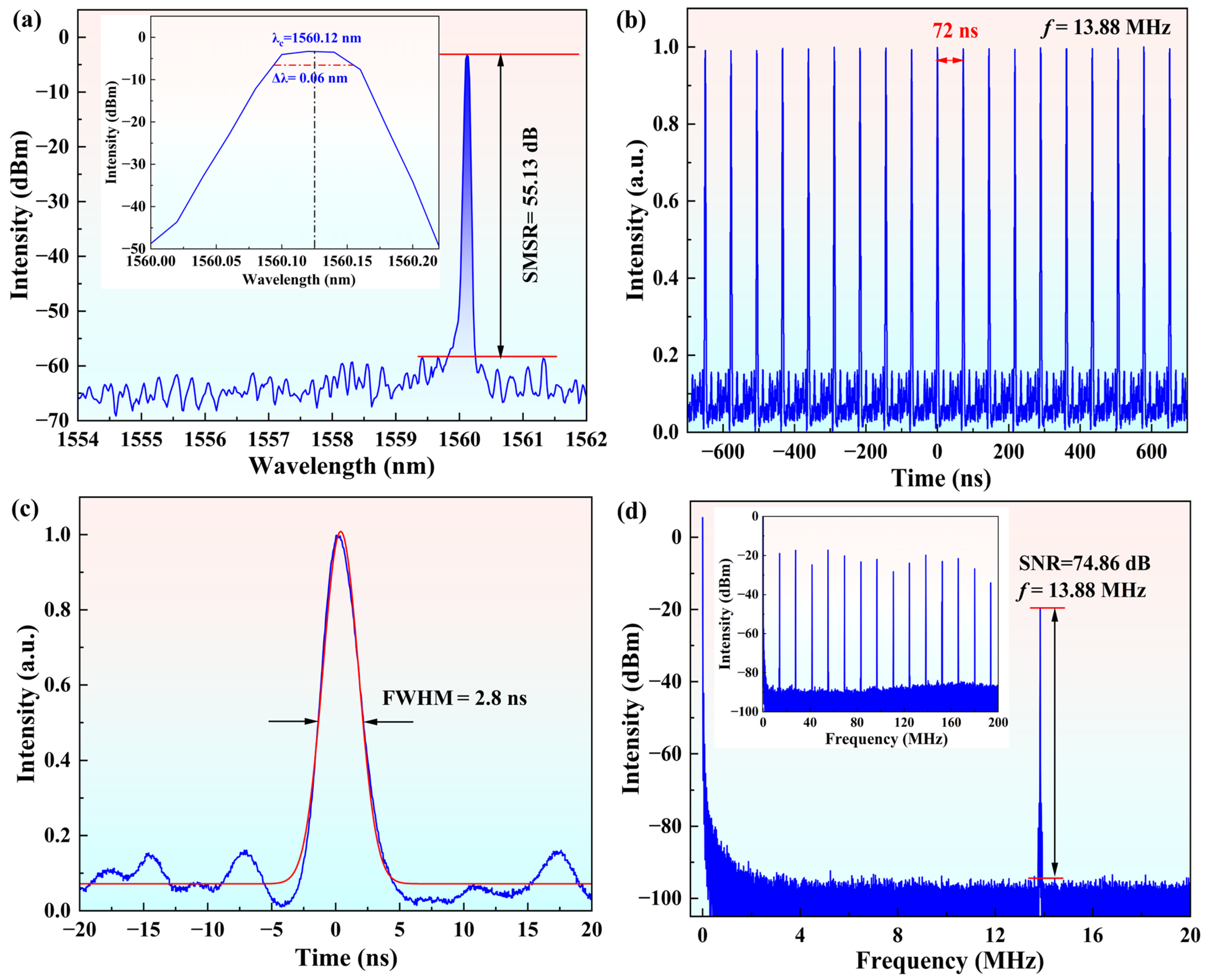

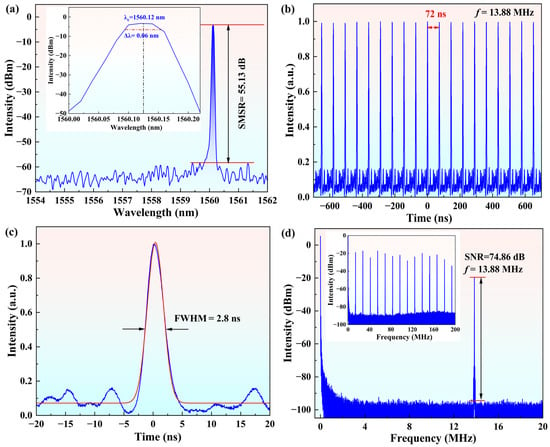

By finely adjusting the PC, the laser output of the MLL at the pump power of 105 mW is characterized in terms of the optical spectrum, pulse train, single pulse, and radio-frequency (RF) spectrum, as summarized in Figure 4. Figure 4a shows the output spectrum of the MLL at with a resolution of 0.02 nm. The wavelength of the mode-locking operation at 1560.12 nm is observed, and is associated with an SMSR of 55.13 dB and a 3 dB linewidth of approximately 0.06 nm. These results show that single-wavelength lasing is achieved, with mode hopping effectively suppressed due to the pronounced wavelength-selective property of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR. Figure 4b presents the pulse train recorded by the OSC, showing a pulse interval of 72 ns, corresponding to a fundamental pulse repetition rate of 13.88 MHz. It is worth noting that, during the experiment, no pulse splitting is observed. The corresponding single-pulse train is shown in Figure 4c, and the temporal profile fitted by a Gaussian function, yielding a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 2.8 ns. To evaluate the stability of the MLL, the RF spectrum is measured over a span of 20 MHz with a resolution of 2 kHz, as presented in Figure 4d. A pronounced peak is located at 13.88 MHz with a high SNR of 74.86 dB, indicating excellent good stability and temporal coherence. This RF peak corresponds to the pulse repetition rate of the 14.4 m main ring cavity, confirming that the MLL operates at the fundamental rate. During the mode-locking process, the TiO2/SiO2 FMR serves as a nonlinear modulator, promoting pulse formation. In addition, the high SNR is attributed to the narrow-linewidth filtering capability, which effectively suppresses spurious frequency components, and further enhances the stability of the pulse train [35].

Figure 4.

Output characteristics of MLL at 105 mW. (a) Spectrum. (b) Pulse train. (c) Single pulse. (d) RF spectrum.

In the experiment, the TiO2/SiO2 FMR simultaneously provides narrowband spectral filtering and nonlinear modulation. On the one hand, the MR supports WGMs, the transmission spectrum exhibits a comb-like distribution, which enables only selected longitudinal modes to oscillate. This typical frequency selectivity effectively suppresses wavelength hopping, thereby significantly enhancing wavelength stability. On the other hand, the strong nonlinearity of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR efficiently induces the Kerr effect within localized regions. As a result, low-threshold, highly stable, and highly coherent MLL can be obtained based on the TiO2/SiO2 FMR.

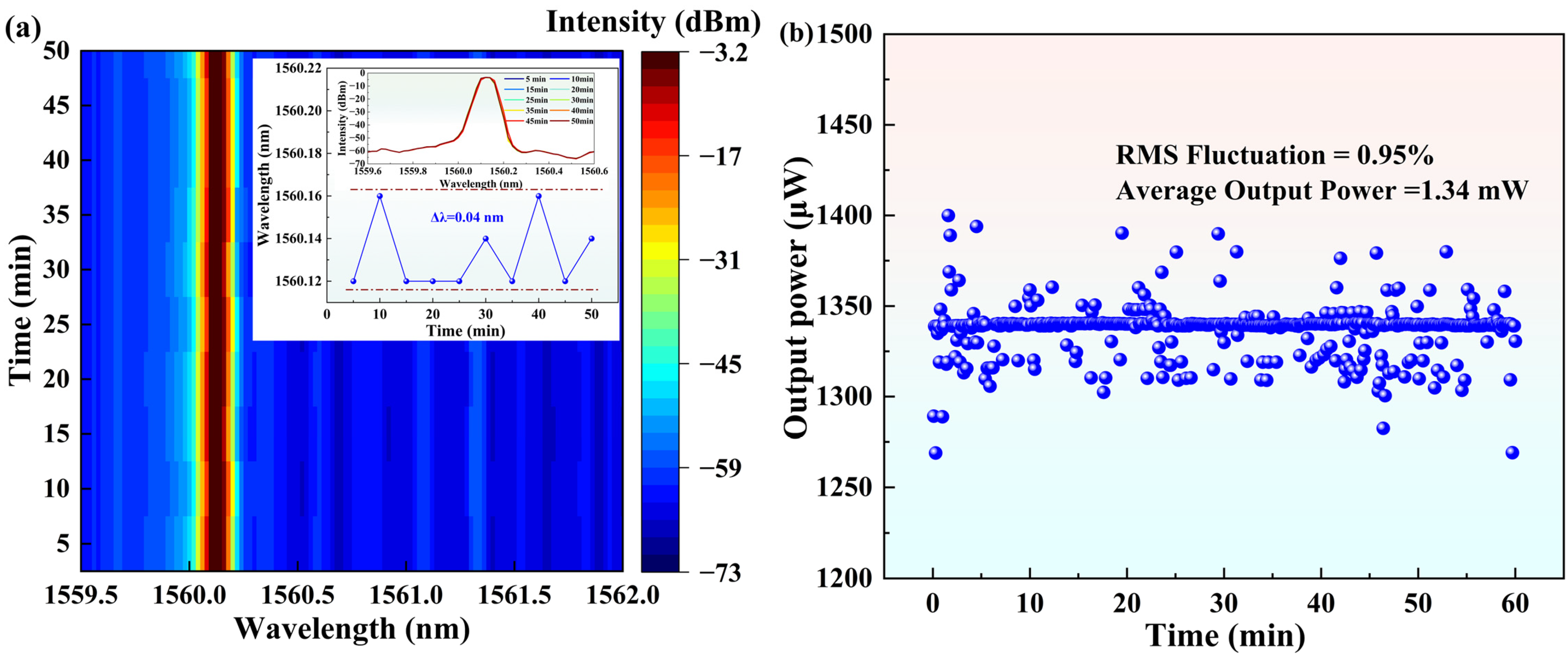

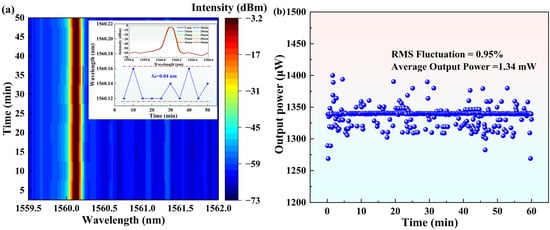

To evaluate the long-term stability of the mode-locking state, the output spectrum and the power of the MLL are continuously monitored at the pump power of 105.7 mW, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Stability test at the pump power of 105 mW. (a) Output spectrum. (b) Output power.

The output spectrum is recorded at 5 min intervals over a period of 50 min, as illustrated in Figure 5a. The wavelength remains highly stable throughout the measurement, with a maximum shift of only 0.04 nm (the inset), demonstrating excellent spectrum stability and coherence of the MLL. The stability of the output power is also measured, as shown in Figure 5b. The maximum average output power of MLL is 1.34 mW, with an RMS fluctuation of 0.95% over 60 min, further exhibiting long-term stability and robustness of the system. Notably, the composite dual-cavity system is encapsulated in a self-made protective box, which effectively isolates external disturbances. In addition, the narrowband filtering property of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR limits longitudinal mode competition, thereby preventing pulse splitting and frequency shifts. To further reduce power fluctuations and improve system performance, feasible optimization strategies include maintaining a stable polarization state, minimizing external disturbances such as mechanical vibrations and air turbulence, and precisely tuning the coupling conditions between the MR and the FT.

4.2. Comparison of MLL Performance in TiO2/SiO2 FMR vs. SiO2 MR

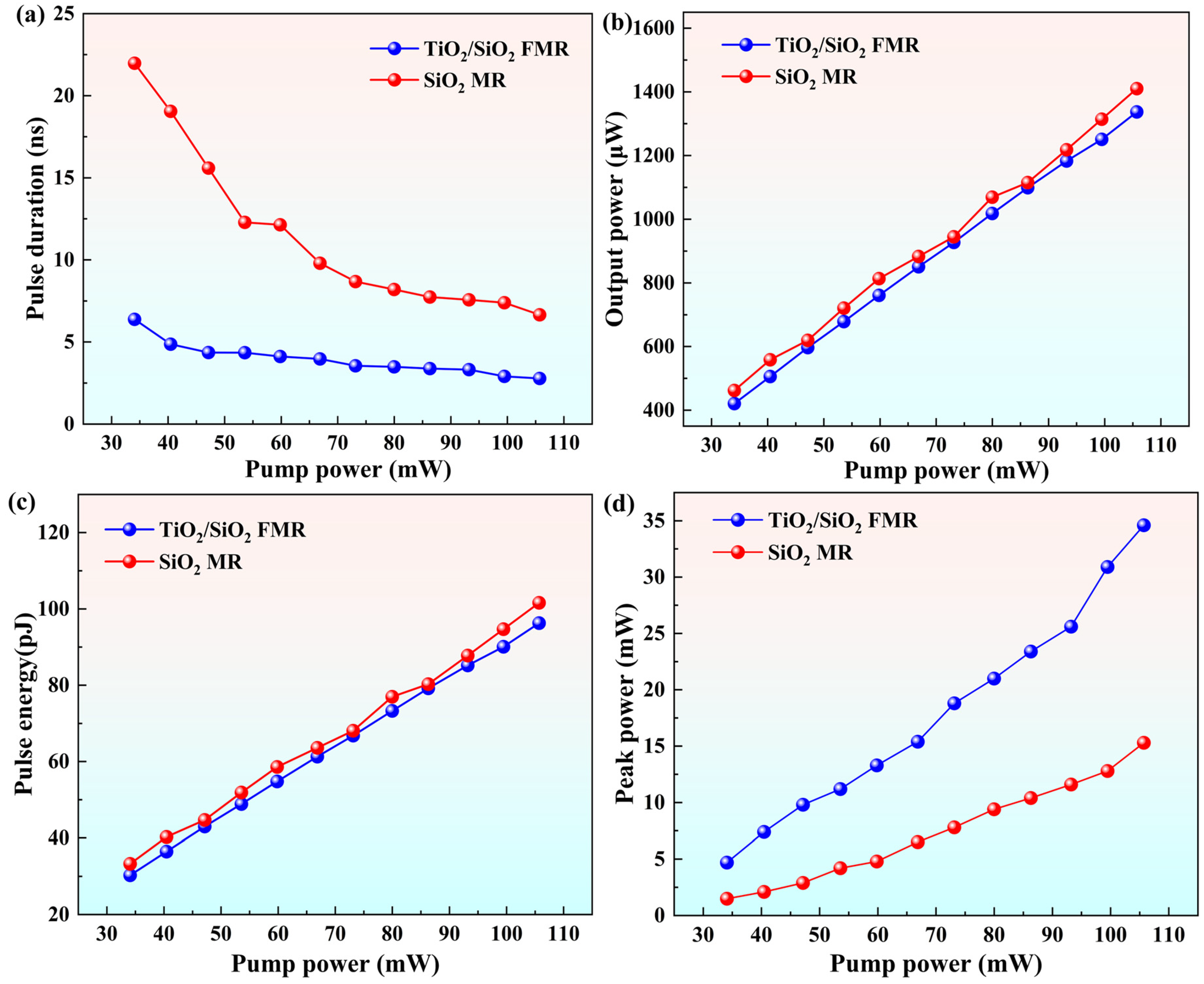

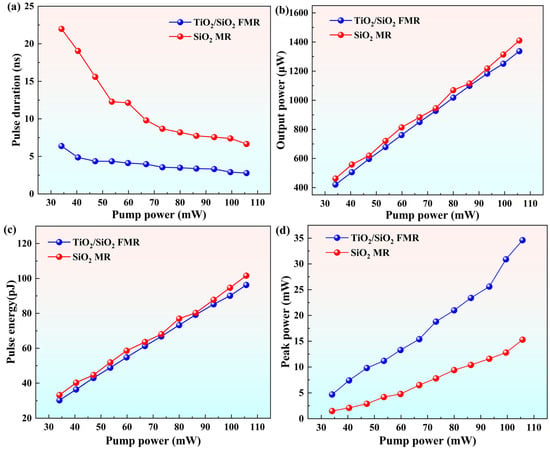

In order to further investigate the influence of functional coating on the output characteristics of MLL, a comparative study between TiO2/SiO2 FMR vs. SiO2 MR is performed. Figure 6 shows the dependence of the pulse duration, output power, single-pulse energy, and peak power on the pump power for MLL.

Figure 6.

Output pulse parameters under different pump power. (a) Pulse duration. (b) Output power. (c) Pulse energy. (d) Peak power.

As shown in Figure 6a, the pulse duration gradually decreases with increasing pump power. Comparative results indicate that the narrowest pulse duration obtained with the TiO2/SiO2 FMR is 2.8 ns, representing a 57% reduction relative to 6.6 ns achieved with the SiO2 MR. Figure 6b,c show that both the average output power and single-pulse energy increase linearly with pump power. At the pump power of 105.7 mW, the output power and single-pulse energy of the SiO2 MR reach 1.41 mW and 101.6 pJ, respectively, which are slightly higher than those of the TiO2/SiO2 FMR (1.34 mW and 96.3 pJ). Figure 6d shows that the peak power increased with pump power, and the TiO2/SiO2 FMR achieved a maximum peak power of 34.6 mW, representing a 126% enhancement relative to 15.3 mW for the SiO2 MR.

The experimental results indicate that the observed improvement in mode-locking performance originates from the introduction of TiO2 film onto of the MR. The coated TiO2 film enables significant pulse compression and an increase in peak power, which is attributed to the enhanced Kerr nonlinearity. The functional film strengthens local phase modulation and promotes coherent longitudinal mode locking. Although the coated MR improves pulse performance, the mode-locking threshold does not show a noticeable decrease. The additional scattering and absorption losses introduced by the TiO2 film result in a lower Q factor of the MR. The intensity-dependent behavior of the passive MLL has also been demonstrated. At low pump power, the intracavity intensity is insufficient to induce the nonlinear phase modulation necessary for pulse formation. Conversely, excessive pump power increases nonlinear accumulation in the cavity, disrupting the phase synchronization between the main ring cavity and the MR, thereby causing the mode-locking state to disappear. Based on the experimental results, the output characteristics of the MLLs can be further optimized by modifying the microcavity structure, material properties, and device parameters.

In addition, as shown in Table 1, the performance of nanosecond pulsed lasers realized by different approaches is compared. Lower threshold power and higher SNR are achieved in this work, which confirms the feasibility of the proposed dual-cavity configuration. These improvements are enabled by the incorporation of the FMR, whose inherent mode-selective property provides effective regulation for stable nanosecond mode-locked operation. Therefore, the compact FMR-assisted dual-cavity architecture is a promising solution for miniaturized, high-performance pulsed laser sources.

Table 1.

Comparison of passively MLLs with various methods.

5. Conclusions

In summary, a composite dual-cavity passively MLL based on a TiO2/SiO2 FMR has been proposed and experimentally demonstrated. The TiO2/SiO2 FMR coated with a high nonlinear TiO2 film on the surface of SiO2 MR, provides both narrow-band spectral filtering and nonlinear modulation, playing a key role in the generation of MLLs. The MLL exhibits a low threshold of 34 mW. At the pump power of 105 mW, stable pulsed output is achieved with a pulse duration of 2.8 ns, a repetition frequency of 13.88 MHz, and an SNR of 74.86 dB. The central wavelength of the spectrum is located at 1560.12 nm, with an SMSR of 55.13 dB and a 3 dB linewidth of approximately 0.06 nm. Compared with an uncoated SiO2 MR, the pulse duration can be compressed by approximately 60%, while the peak power increased by nearly 126%. These results demonstrate that the TiO2/SiO2 FMR not only enables low-threshold, stable MLL operation, but also provides insight into its influence on pulse characteristics. The results indicate that functional coating of MR provides an effective degree of freedom for mode-locking, which is beyond simple cavity optimization and offers a new route for microcavity-assisted ultrafast fiber lasers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu) and T.W. (Tianshu Wang); methodology, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu) and B.L.; software, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu)validation, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu) and B.L.; formal analysis, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu); investigation, B.L.; resources, T.W. (Tianshu Wang); data curation, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu); writing—original draft preparation, T.W. (Tianjiao Wu); writing—review and editing, B.L.; visualization, T.W. (Tianshu Wang) and B.L.; supervision, T.W. (Tianshu Wang); project administration, T.W. (Tianshu Wang); funding acquisition, T.W. (Tianshu Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Science and Technology Project of Jilin Province (20220508134RC), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61975021), the 111 Project of China (D21009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are shown in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declares that there are has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ryczkowski, P.; Närhi, M.; Billet, C.; Merolla, J.-M.; Genty, G.; Dudley, J.M. Real-time full-field characterization of transient dissipative soliton dynamics in a mode locked laser. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Company, V.; Schroder, J.; Fulop, A.; Mazur, M.; Lundberg, L.; Helgason, O.B.; Karlsson, M.; Andrekson, P.A. Laser frequency combs for coherent optical communications. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniewski, P.; Brunzell, M.; Barrett, L.; Harvey, C.M.; Pasiskevicius, V.; Laurell, F. Er-doped silica fiber laser made by powder-based additive manufacturing. Optica 2023, 10, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T. Passively Q-Switched and Mode-Locked Er3+-Doped Ring Fiber Laser with Pulse Width of Hundreds of Picoseconds. Photonics 2021, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddams, S.A.; Vahala, K.; Udem, T. Optical frequency combs: Coherently uniting the electromagnetic spectrum. Science 2020, 369, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Zhou, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Nakkeeran, K. Progressive pulse dynamics in a mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 168, 109827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zou, H. Inverse Saturable Absorption Mechanism in Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers with a Nonlinear Amplifying Loop Mirror. Photonics 2023, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Lv, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Co-existence of watt-level dissipative solitons and synchronous dual-wavelength mode-locked pulses in Yb fiber laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2023, 35, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Zhang, H.; Gong, Q.; He, L.; Li, D.; Gong, M. Energy scalability of the dissipative soliton in an all-normal-dispersion fiber laser with nonlinear amplifying loop mirror. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 125, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C. Narrow bandwidth mode-locked fiber laser with the GIMF-based saturable absorber. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2024, 87, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahala, K.J. Optical microcavities. Nature 2003, 424, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y. Packaged ultrahigh-Q silica hollow microrod WGM resonator with simplified modes for nonlinear photonics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumetsky, M.; Dulashko, Y.; Windeler, R.S. Super free spectral range tunable optical microbubble resonator. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 1866–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, X.; Kan, C.; Shi, D. Performance-enhanced single-mode microlasers in an individual microwire covered by Ag nanowires. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 155, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wan, P.; Liu, M.; Tang, K.; Li, L.; He, T.; Shi, D.; Kan, C.; Jiang, M. High Q-factor and low threshold electrically pumped single-mode microlaser based on a single-microwire double-heterojunction device. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 3276–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Ji, Y.; Xiong, B.; Du, Z.; Yang, X. Tunable laser absorption imaging for 2D gas measurement with an electronic rolling shutter camera. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2022, 34, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erushin, E.; Nyushkov, B.; Ivanenko, A.; Akhmathanov, A.; Shur, V.; Boyko, A.; Kostyukova, N.; Kolker, D. Tunable injection-seeded fan-out-PPLN optical parametric oscillator for high-sensitivity gas detection. Laser Phys. Lett. 2021, 18, 116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalanos, G.N.; Silver, J.M.; Bino, L.D.; Moroney, N.; Zhang, S.; Woodley, M.T. M.; Svela, A.Ø.; Haye, P.D. Kerr-Nonlinearity-Induced Mode-Splitting in Optical Microresonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 223901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Liu, S.; Bowers, J.E. Integrated optical frequency comb technologies. Nat. Photonics 2022, 16, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strekalov, D.V.; Marquardt, C.; Matsko, A.B.; Schwefel, H.G.L.; Leuchs, G. Nonlinear and quantum optics with whispering gallery resonators. J. Opt. 2016, 18, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Özdemir, S.K.; Lei, F.; Gianfreda, F.M.M.; Long, G.; Fan, S.; Nori, F.; Bender, C.M.; Yang, L. Parity–time-symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat. Phys. 2014, 10, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccianti, M.; Pasquazi, A.; Park, Y.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Demonstration of a stable ultrafast laser based on a nonlinear microcavity. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Chu, S.T.; Little, B.E.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Repetition rate multiplication pulsed laser source based on a microring resonator. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Guo, X.; Huang, X.; Peng, F.; Li, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Q. Highly Birefringence-Guided Microfiber Resonator for Ultra-High Repetition Rate Ultrashort Pulse. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kues, M.; Reimer, C.; Wetzel, B.; Roztocki, P.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Hansson, T.; Viktorov, E.A.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Passively mode-locked laser with an ultra-narrow spectral width. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, X.; Han, Y.; Chen, E.; Guo, P.; Zhang, W.; An, M.; Pan, Z.; Xu, Q.; Guo, X.; et al. High-performance γ-MnO2 Dual-Core, Pair-Hole Fiber for Ultrafast Photonics. Ultrafast Sci. 2023, 3, 0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ozdemir, Ş.K.; Monifi, F.; Chadha, T.; Huang, S.H.; Biswas, P.; Yang, L. Titanium Dioxide Whispering Gallery Microcavities. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2014, 2, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Monteiro, C.S.; Silva, S.O.; Frazão, O.; Pinto, J.V.; Raposo, M.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Sério, S. Sputtering deposition of TiO2 thin film coatings for fiber optic sensors. Photonics 2022, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Guan, X. TiO2 microring resonators with high Q and compact footprint fabricated by a bottom-up method. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 5012–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Shen, Z.; Gu, P.; Hu, T.; Chen, J. Tunable, single-wavelength fiber laser based on hybrid microcavity functionalized by atomic layer deposition. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 2513–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Yang, W.; Hui, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, Q. Sol–gel preparation of a silica antireflective coating with enhanced hydrophobicity and optical stability in vacuum. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2014, 12, 071601. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Savchenkov, A.A.; Dale, E.; Liang, W.; Eliyahu, D.; Ilchenko, V.S.; Maleki, L.; Wong, C.W. Chasing the thermodynamical noise limit in whispering-gallery-mode resonators for ultrastable laser frequency stabilization. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhadnov, N.; Masalov, A. Temperature-independent optical cavities for laser frequency stabilization. Laser Phys. Lett. 2023, 20, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.D. An introduction to Pound–Drever–Hall laser frequency stabilization. Am. J. Phys. 2001, 69, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Jin, L.; Liu, Z.; Tao, L.; Zhang, H.; Bi, M.; Zhou, X. High signal-to-noise ratio harmonic mode-locking Mamyshev oscillator at 1550 nm. Opt. Commun. 2024, 569, 130787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, A.H.A.; Latiff, A.A.; Abdul Khudus, M.I.M.; Harun, S.W. Nanosecond pulses generation with rose gold nanoparticles saturable absorber. Indian J. Phys. 2020, 94, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, E.I.; Ahmad, F.; Shafie, S.; Yahaya, H.; Latif, A.A.; Muhammad, F.D. Copper nanowires based mode-locker for soliton nanosecond pulse generation in erbium-doped fiber laser. Results Phys. 2020, 18, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadi, N.I.S.; Jusoh, Z.; Muhammad, A.R.; Ahmad, B.A.; Salam, S. Nanosecond-pulse fiber laser mode-locked with iron phthalocyanine. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 095525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.X.; Li, H.; Li, X.W.; Yang, F. Sub-10 ns mode-locked fiber lasers with multimode fiber saturable absorber. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2024, 84, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.