Abstract

This paper systematically reviews the key spectral information extraction methods in Brillouin microscopy, aiming to address the core challenge of accurately extracting material mechanical parameters from raw spectra. Based on technical principles, the methods are categorized into three types for elaboration: Spontaneous Brillouin Scattering (SpBS) is characterized by low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and strong background interference, and its processing relies on high-precision spectrometers and complex preprocessing procedures to mitigate noise and background effects; Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (SBS) operates on the mechanism of optical gain/loss, which achieves significantly improved data SNR and thereby enables more robust and accurate Lorentzian fitting for spectral analysis; Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (ISBS) retrieves the frequency spectrum by inverting time-domain oscillating signals, and the core of its processing lies in super-resolution algorithms such as Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and the Matrix Pencil Method, which are tailored to match its high-speed data acquisition capability. The paper further compares the advantages and disadvantages of various methods, outlines future development trends of intelligent processing technologies such as deep learning and multi-modal data fusion, and provides a clear guide for selecting the optimal data processing strategy in different application scenarios.

1. Introduction

Brillouin microscopy is a label-free optical detection technique based on inelastic light scattering from acoustic phonons in materials. Its growing significance in the life sciences has recently culminated in an international consensus statement [1], which establishes unified reporting standards and instrumental guidelines for the field. By quantifying the frequency shift in scattered light relative to incident radiation, this approach enables non-invasive characterization of microscale mechanical properties, demonstrating significant potential for applications in materials science and biomedical research [2,3,4,5,6]. Brillouin scattering is principally classified into two categories based on excitation phonon modes: Spontaneous Brillouin Scattering (SpBS) induced by thermally fluctuating phonons [7], and Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (SBS) driven by coherent optical pumping [8]. However, raw Brillouin spectra face ubiquitous challenges such as low signal-to-noise ratio [9], vulnerability to strong Rayleigh scattering interference [10], and spectral superposition of multiple peaks [11], resulting in critical bottlenecks for precise and efficient extraction of frequency shift and linewidth parameters from complex spectra.

For SpBS spectral extraction, researchers typically employ Fabry-Pérot (F-P) interferometer-based spectral acquisition systems coupled with nonlinear least-squares fitting for parameter retrieval. This methodology demonstrates critical limitations, including heavy reliance on domain-specific prior knowledge and constrained processing throughput [12,13,14]. To address the critical needs for high-speed operation and low photodamage in biological specimen characterization, SpBS spectroscopy employing a Virtually Imaged Phased Array (VIPA) has emerged, demonstrating substantially enhanced spectral acquisition efficiency [15,16,17,18]. In contrast to SpBS, SBS spectroscopy extracts spectral information through its unique stimulated amplification mechanism, establishing fundamental distinctions in both data acquisition strategies and processing methodologies. The core innovation of this technique lies in indirect Brillouin gain/loss spectral mapping via laser frequency scanning, rather than direct spectral separation or detection of scattered photons. [19] For SBS spectral information extraction, linear least-squares fitting represents the most extensively utilized classical methodology. This technique constructs a Lorentzian function model incorporating critical parameters including Brillouin frequency shift, linewidth, gain peak, and background offset. Through iterative optimization employing algorithms such as Levenberg–Marquardt, it achieves simultaneous high-accuracy determination of both elastic and viscous material properties [20,21,22]. This methodology demonstrates optimal performance in static measurement scenarios with high signal-to-noise ratios (SNR). Nonetheless, relying on the assumption of a Lorentzian profile for Brillouin peak fitting risks introducing systematic errors when spectral lineshapes deviate due to sample heterogeneity or instrumental broadening. Recent advancements in intelligent algorithms have inspired data-driven paradigms to enhance spectral analysis automation and robustness [23]. Nevertheless, a systematic categorization and comparative evaluation of existing computational strategies remains conspicuously absent.

This article delineates the developmental path of Brillouin spectral extraction strategies, evaluates the performance trade-offs between conventional fitting and intelligent algorithms, and explores their suitability for various scenarios alongside current obstacles. Such an analysis intends to offer theoretical foundations and processing solutions to advance Brillouin spectroscopy toward broader practical implementation. Notably, a recent international consensus statement has standardized the reporting metrics and instrumental guidelines for Brillouin light scattering in biological materials, highlighting the maturity and growing significance of this field.

2. Theoretical Foundations of Brillouin Microscopy

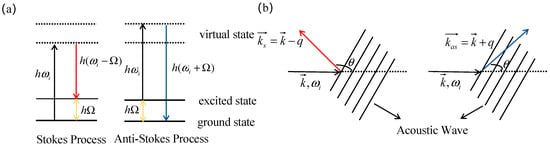

The physical foundation of Brillouin microscopy lies in the inelastic scattering process between light and acoustic phonons within materials. Governed by the Doppler effect, this scattering manifests as Stokes and anti-Stokes processes: In Stokes scattering, photons lose energy to generate an acoustic phonon and a redshifted Stokes photon, whereas in anti-Stokes scattering, phonons transfer energy to photons, producing a blueshifted anti-Stokes photon. Consistent with energy conservation, the angular frequencies of Stokes and anti-Stokes light satisfy:

where and denote the angular frequencies of the incident light and the acoustic wave, respectively. The frequency shift between the incident light and the scattered Stokes/anti-Stokes light defines the Brillouin frequency shift , a process schematically depicted in Figure 1a. Momentum conservation dictates two processes: Stokes scattering generates a Stokes photon and forward-propagating wave from incident light, while anti-Stokes scattering combines incident light with backward-propagating waves to produce anti-Stokes photons, as shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Brillouin Scattering Process (a) Energy Conservation in the Brillouin Scattering Process (b) Momentum Conservation in the Brillouin Scattering Process.

The Brillouin frequency shift correlates with the medium’s sound velocity through

where is refractive index, is vacuum wavelength, and is scattering angle. Material viscoelasticity stems from microstructural responses to mechanical stress, governing both sound propagation velocity and attenuation. Consequently, sound velocity measures the elastic modulus ( = storage modulus), obeying the constitutive relation:

with is material density and quantifying elastic energy storage. Acoustic attenuation principally originates from the viscous modulus ( = loss modulus), which quantifies mechanical energy dissipation into heat through viscoelastic relaxation. proportional to the longitudinal viscosity coefficient through:

In Brillouin spectroscopy, the attenuation coefficient is experimentally quantified through the spectral linewidth :

By correlating the Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth within backscattering geometry (), the viscoelastic moduli are derived:

Ultimately, viscoelasticity can be expressed by the complex longitudinal modulus [24]:

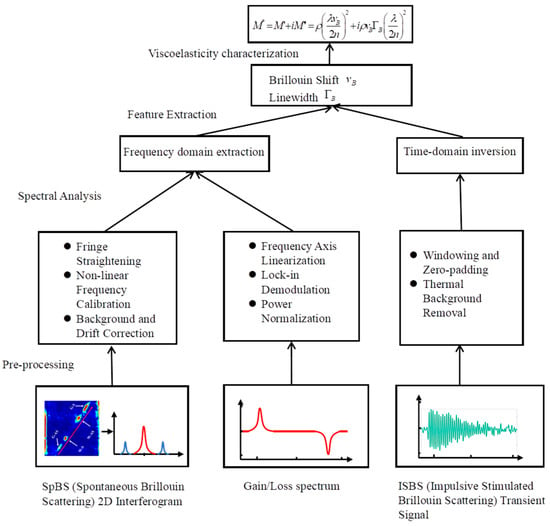

While Equations (1)–(7) establish the theoretical link between Brillouin scattering and material viscoelasticity, accurately retrieving the frequency shift and linewidth from experimental noise remains a significant computational challenge. To bridge the gap between physical theory and experimental implementation, Figure 2 summarizes the general data processing pipeline. The workflow begins with the acquisition of raw signals, which vary fundamentally across modalities: SpBS yields 2D interferometric images, Continuous-Wave Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (CW-SBS) produces frequency-scanned gain/loss spectra, and Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (ISBS) generates time-domain transient oscillations. Before feature extraction, these signals must undergo rigorous pre-processing—such as fringe straightening for SpBS, frequency axis linearization for CW-SBS, or thermal background removal for ISBS—to mitigate instrumental artifacts. Subsequently, core spectral analysis algorithms are employed to precisely extract and . Finally, these spectral features are mapped back to the and via the constitutive equations. The specific implementation and evolution of these algorithmic strategies are detailed in the following sections.

Figure 2.

General data processing and physical inversion framework for Brillouin microscopy.

Brillouin spectroscopy has been extensively demonstrated as a powerful technique for characterizing material viscoelasticity. Its non-contact and label-free measurement capabilities have made it a research hotspot in recent years, providing significant insights into micromechanical behavior across various fields. In materials science, Brillouin spectroscopy is employed for the non-destructive determination of elastic constants and viscoelastic responses of polymers, glasses, and ice at high frequencies (GHz). For instance, Gammon P. H. et al. [25] at the University of Cambridge utilized this technique to precisely measure the elastic constants of natural and artificial ice samples, offering new data for understanding the mechanical properties of ice. Furthermore, the work of Baranowski J. et al. [26] showcased the high-resolution capability of Brillouin spectroscopy in characterizing surface acoustic waves. In the biomedical domain, Brillouin spectroscopy is widely used for viscoelastic imaging of cells, tissues, and 3D tumor spheroid models. A study published by Jan Rix et al. [27] demonstrated its utility in monitoring heterogeneous changes in the internal mechanical properties of tumor spheroids after drug treatment, providing a new perspective for cancer mechanism research. The technique has also been applied to measure the viscoelasticity of elastin and collagen fibers within the extracellular matrix, revealing the relationship between tissue structure and function [28]. In ophthalmic applications, Brillouin microscopy is used for the non-invasive assessment of the biomechanical properties of the cornea and lens, such as mechanical changes after corneal cross-linking and age-related lens stiffening. [29] Moreover, it has been successfully applied to characterize the elasticity of vocal folds [30], biofluids [31], neural tissues [32], human soft tissues [33], and bovine jugular veins [34].

The broad applicability of Brillouin spectroscopy in materials science and biomedicine fundamentally relies on the high-fidelity extraction of two core parameters from the raw spectra: the Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth .

In practical application, signal retrieval encounters severe impediments including the faint magnitude of spontaneous Brillouin scattering, the immediate vicinity of the strong elastic Rayleigh peak, pump noise interference in stimulated regimes, and spectral superposition within heterogeneous samples. These physical constraints necessitate algorithms possessing exceptional accuracy and robust noise immunity, making the sophistication of the computational scheme the primary determinant for the ultimate precision and spatial resolution of the derived viscoelastic properties. Efforts to surmount such bottlenecks have catalyzed a diverse array of evolving processing solutions. Accordingly, the subsequent sections comprehensively survey analysis protocols for both spontaneous and stimulated modalities by detailing their fundamental mechanisms, technical progression, and operational metrics.

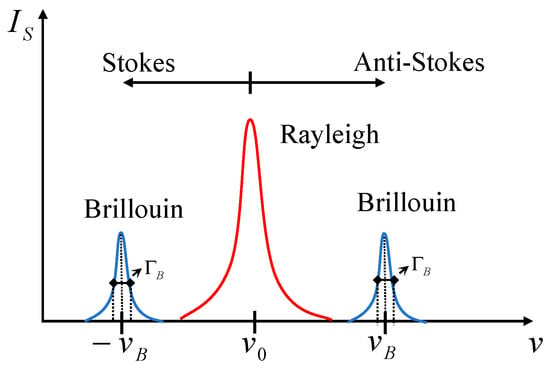

3. Spectral Extraction Methodologies for SpBS Microscopy

The signal generated by SpBS is inherently weak. As depicted in Figure 3, the resulting Stokes and Anti-Stokes peaks are positioned symmetrically around the Rayleigh peak, which is several orders of magnitude more intense. With typical frequency shifts of 1–100 GHz (corresponding to a wavelength change of <0.01 nm), these faint Brillouin features are spectrally very close to the dominant Rayleigh line. This characteristic makes them difficult to resolve using conventional grating spectrometers. Consequently, the central challenge in leveraging SpBS for practical implementation is the development of spectral information extraction techniques that possess both ultra-high spectral resolution and excellent stray light rejection capabilities.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Typical Spectra for Rayleigh Scattering and Brillouin Scattering, where the Stokes Peaks and Anti-Stokes Peaks Generated by Brillouin Scattering are Distributed on Both Sides of the Central Rayleigh Peak. The frequency offset denotes the Brillouin frequency shift and the peak width at half height represents the Brillouin linewidth .

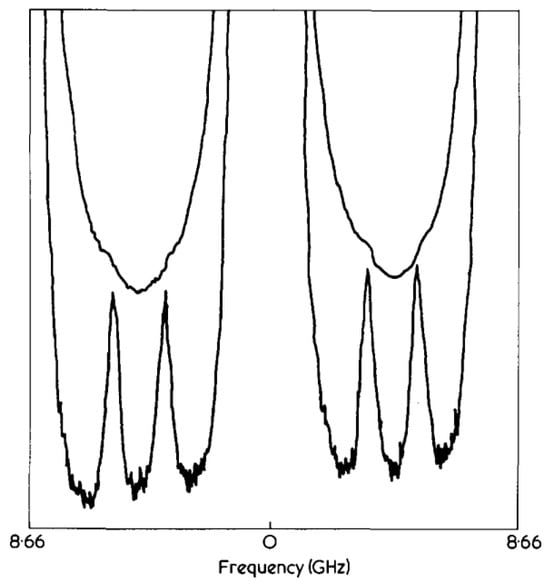

In a seminal 1976 investigation, D. S. Bedborough and D. A. Jackson [35] pioneered the use of a double-pass Fabry-Pérot (F-P) interferometer to resolve polymer gel Brillouin spectra. This configuration routes the optical signal through a standard etalon twice sequentially. Following initial filtration during the primary transit, retro-reflection directs the beam back into the cavity for a secondary pass. The superposition of these two filtering processes results in a substantial enhancement of spectral contrast. The implemented system, characterized by a free spectral range (FSR) of 8.66 GHz and a finesse of approximately 40, attained a final resolution of 200 MHz. This performance was sufficient to permit the precise quantification of variations in the Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth within the gelatin gel. The fundamental merit of the double-pass configuration over its single-pass antecedent is the significant augmentation of contrast without degrading instrumental resolution. As Figure 4 illustrates, whereas the Brillouin features in the single-pass spectrum (upper trace) are completely masked by the overwhelming elastic scattering intensity, they become clearly resolved in the double-pass spectrum (lower trace), enabling direct quantitative analysis of their spectral position and width.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Typical Brillouin Spectra of Low-Concentration Gelatin Gels Obtained by the Double-Pass F-P Technique and the Single-Pass F-P Technique Proposed by Bedborough et al.

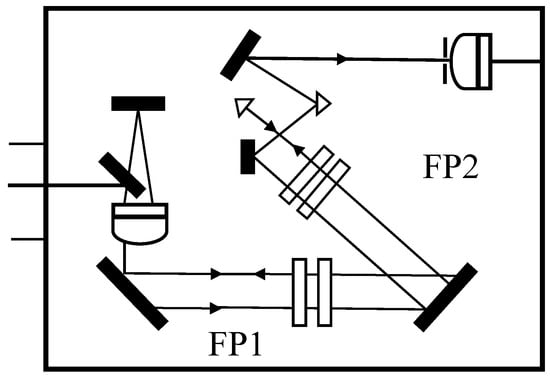

In 1980, Vaughan [13] reported the inaugural use of a passively stabilized, triple-pass F-P interferometer for the analysis of Brillouin spectroscopy from vertebrate ocular refractive tissues, including the cornea and crystalline lens. Figure 5 presents the schematic configuration of a representative multipass tandem F-P architecture. The technique operates by guiding the scattered light through the F-P etalon three times. This triple-pass configuration drastically improves spectral contrast through the superposition of multiple interference events. When coupled with a 488 nm single-mode argon-ion laser and a micron-scale focusing system, the instrument could precisely resolve Brillouin frequency shifts and linewidths within the 1–10 GHz range. This technique suppresses elastic scattering intensities exceeding the Brillouin signal by a factor of 106, including artifacts from corneal turbidity. The system was also capable of acquiring spectra from varying radial depths within the crystalline lens, distinctly resolving the differences in elasticity between the nuclear and peripheral zones.

Figure 5.

Schematic of a Typical Multi-Pass Tandem F-P Interferometer.

A significant advancement occurred in 2005, when K. J. Koski and J. L. Yarger [36] introduced a technique that integrated an angularly dispersive F-P interferometer with confocal backscattering. This innovation marked the first successful union of Brillouin spectral acquisition with spatial imaging. By employing a design that featured non-scanning spectral separation and spatial filtering, their approach simultaneously achieved rapid data collection and high resolution. This work culminated in the first demonstration of two-dimensional Brillouin imaging, performed on a liquid polymer sample.

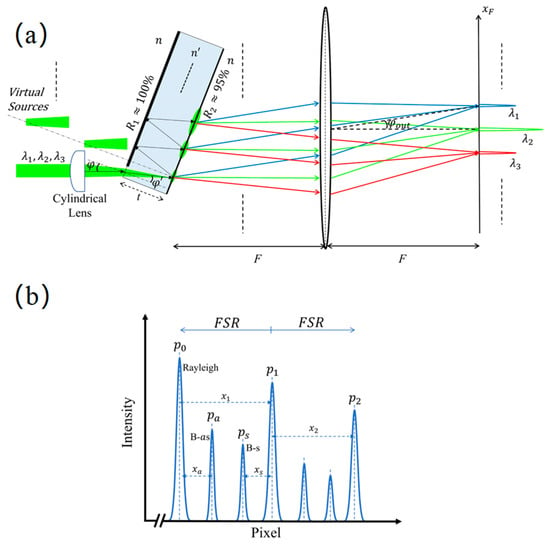

Conventional approaches that rely on tandem or multi-pass scanning F-P interferometers are constrained by modest spatial resolution and protracted spectral acquisition times. The virtually imaged phased array (VIPA) has emerged as a powerful alternative. As an optical element characterized by exceptionally high chromatic dispersion, the VIPA offers a cost-effective means of attaining ultra-high spectral resolution. Moreover, its distinct architecture permits a substantial increase in optical throughput, leading to a significant reduction in data acquisition duration and a decrease in overall system complexity. The structure and operational principle of the VIPA are depicted in Figure 6 [37]. It functions based on parallel-plate interference, analogous to an F-P etalon, but its method of implementation differs from that of a traditional F-P interferometer. A conventional F-P etalon possesses two surfaces coated with high-reflectivity films, a configuration that intrinsically results in very low optical throughput. This characteristic severely impedes the collection of the inherently faint Brillouin signal. The VIPA overcomes this deficiency by incorporating a highly transparent entrance window in addition to its two high-reflectivity surfaces, thereby effectively compensating for the primary limitation of the F-P etalon.

Figure 6.

The structure and working principle of VIPA (a) Schematic of VIPA Structure and Dispersion; (b) Schematic of Brillouin Spectrum, where , and are Rayleigh Peaks, is the Stokes Peak, and is the Anti-Stokes Peak.

Despite the high throughput of VIPA, the spectral contrast of a single-stage device is often insufficient to fully reject the strong elastic Rayleigh scattering inherent in turbid biological media. To surmount this limitation and enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), various background suppression strategies have been developed. Spectral apodization techniques [38] are employed to suppress the spectral leakage of the elastic peak, preventing faint Brillouin signals from being masked by side-lobes. For stronger rejection, multi-pass or cascaded etalon configurations [39] exponentially increase the extinction ratio through sequential filtering. Additionally, destructive interference methods [40] utilize phase cancellation to selectively nullify the elastic background, while molecular absorption cells (e.g., Iodine) [41] offer an ultra-narrow notch filter by tuning the laser frequency to match specific absorption lines. These filtering technologies lay the necessary foundation for high-fidelity spectral acquisition.

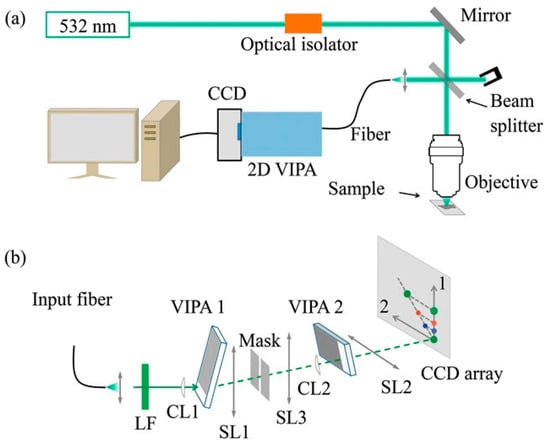

In 2015, Kim V. Berghaus [42] introduced a parallel, high-extinction, and high-resolution Brillouin acquisition scheme predicated on a dual-stage, cross-axis VIPA interferometer, with the specific optical design displayed in Figure 7. To elaborate, this work utilized a tandem VIPA configuration whose central advantage was the ability to independently insert, remove, and align each stage in the optical path without mutual perturbation. This design enabled the finesse of the individual stages to be stably maintained above 40 (VIPA1) and 30 (VIPA2), respectively, culminating in a total system extinction ratio superior to 60 dB. This arrangement permitted the acquisition of a single Brillouin spectroscopy on a sub-second timescale, representing an enhancement in measurement throughput of three to four orders of magnitude relative to conventional scanning F-P interferometers. Concurrently, the system exhibited outstanding spectral performance. To address noise and instrumental drift in raw 2D interferometric patterns, they implemented a specialized algorithmic pipeline for precise frequency shift extraction. This multi-step process began with background intensity normalization across datasets. Instead of conventional peak-finding, a weighted centroid approach determined peak positions. The algorithm scanned the image with a defined window to calculate the intensity-weighted center of mass. This strategy successfully decoupled Brillouin peak localization from high-amplitude background noise. Furthermore, the protocol incorporated temporal linear interpolation to correct frequency axis fluctuations via periodic standard reference acquisitions. These combined hardware and computational advancements enabled sub-gigahertz spectral resolution, ensuring the accurate detection of characteristic 1 GHz Brillouin shifts in biological tissues.

Figure 7.

Two-Stage VIPA Spectrometer Proposed by Kim V. Berghaus et al. (a) Schematic of the Brillouin Spectrometer; (b) More Detailed Schematic of the Two-Stage VIPA Spectrometer.

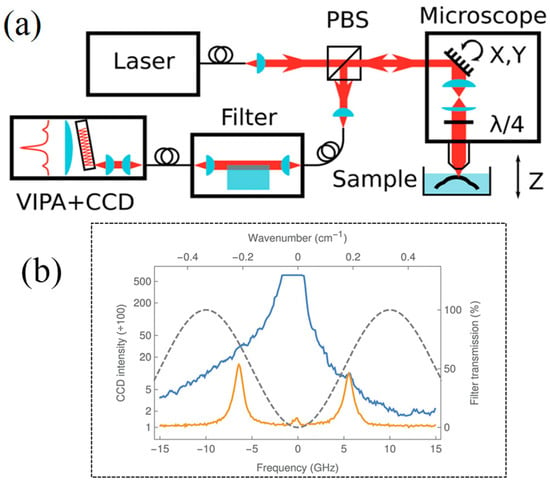

In 2016, Guillaume [43] put forward a hybrid Brillouin microspectroscopy approach that integrates a single-stage VIPA with a novel adaptive optical interference filter, intended for the non-contact biomechanical characterization of transparent soft biomaterials. Through the precise control of the optical path difference, this filter engineers destructive interference at the laser wavelength, resulting in the suppression of the elastic scattering background by more than 46 dB. This design effectively isolates the Brillouin signal from the formidable background noise, elevating the signal-to-noise ratio of the Stokes and anti-Stokes peaks by an order of magnitude. To optimize data fidelity, the authors implemented a rigorous processing pipeline: sensor-level vertical binning was employed to rapidly convert 2D interferograms into 1D spectra, while a quadratic model was adopted to calibrate the VIPA’s inherent non-linear dispersion. Furthermore, a dynamic drift correction strategy utilizing Rayleigh peak tracking and Stokes/anti-Stokes averaging was applied. This common-mode rejection technique effectively eliminated errors from thermal and laser frequency instabilities, enabling precise biomechanical characterization of highly scattering biological tissues. Figure 8 exhibits the utilized single-stage VIPA spectrometer setup alongside the acquired aqueous Brillouin spectrum.

Figure 8.

Brillouin Microscope Combining a Single-Stage VIPA with Adaptive Optics Proposed by Guillaume et al. (a) Schematic diagram of the simple experimental setup (b) aqueous Brillouin spectrum.

In 2021, Meng et al. [44] proposed a VIPA-based Brillouin spectroscopy technique for determining material elastic moduli by introducing a cross-axis cascaded dispersion architecture. By combining a VIPA with a diffraction grating, the system effectively resolved the “spectral order overlap” problem inherent to high-finesse etalons. From a signal processing perspective, this configuration required a specific reconstruction algorithm to decode the 2D spectral image, where the grating disperses light vertically to separate overlapping orders while the VIPA provides high-resolution horizontal dispersion. The authors established a theoretical framework linking the Brillouin frequency shift directly to the longitudinal elastic modulus through rigorous derivation of the dispersion equations. For spectral extraction, a Lorentzian peak-fitting algorithm was employed to precisely locate the Brillouin shifts from the discrete spectral points. This configuration achieved a spectral resolution of 0.25 GHz and successfully quantified Brillouin frequency shifts in samples including polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyethylene, and silica glass, yielding modulus values consistent with standard mechanical testing. In 2024, Xu et al. [17] developed a fully parallel dispersive Brillouin spectrometer comprising a two-stage VIPA and a CMOS camera. Integrating a high-resolution, small-pixel sensor with a zoom lens shortened the optical path, reducing the dispersion rate to 0.047 GHz per pixel. Rigorous spectral dispersion analysis guided the system optimization, proving that the enhanced spectral sampling rate obviates the need for post-processing interpolation algorithms. Additionally, the authors implemented a “virtual-bright-fringe” algorithm to address calibration challenges. This computational method derives Brillouin frequency shifts from multiple Rayleigh interference orders, thereby eliminating dependence on frequent standard reference measurements. Ultimately, this architecture achieved a spectral precision surpassing 50 MHz alongside effective elastic scattering suppression. Upon application to ex vivo porcine eyes, the system yielded micron-scale measurements, producing imaging maps that clearly demarcated the corneal-scleral boundary and revealed non-uniform corneal biomechanics. In 2025, Ibrahim et al. [45] pioneered a deep learning-guided smart imaging approach to accelerate SpBS microscopy. Instead of merely increasing single-spectrum acquisition speed, this study introduced a self-driving microscope. The AEGON model predicts aggregation onset from single soluble protein fluorescence images with 91% accuracy, triggering optimized multimodal imaging. Concurrently, the IC-LINA model detects mature aggregates from bright-field images in real-time without labeling. This strategy minimizes phototoxicity, enabling the first dynamic biomechanical analysis of protein aggregation and providing a robust tool for investigating neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) such as Huntington’s disease. In the same year, Christopher et al. [46] applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [47] and Vertex Component Analysis (VCA) [48] to Brillouin spectral analysis. These unsupervised machine learning algorithms extract primary features via PCA dimensionality reduction and identify pure end-member spectra through VCA, requiring no prior sample information. This methodology successfully isolated component spectra from heterogeneous biological specimens, including protein liquid–liquid phase separation systems. Notably, VCA resolved spectral overlaps where PCA proved ineffective.

To summarize, SpBS spectral retrieval methodologies have evolved to address the critical challenge of accurately resolving frequency shifts from low-photon-flux signals amidst strong background interference. The technical lineage has progressed from early high-precision fitting via scanning F-P interferometers to parallel VIPA-based architectures. Crucially, increasingly sophisticated computational strategies underpin this hardware evolution. Algorithmic innovations such as non-linear frequency calibration, sensor-level binning, and dynamic drift correction have become as essential as the optical design itself. While recent deep learning approaches further push the boundaries of high-speed imaging, the intrinsic physical limits on spontaneous signal intensity continue to restrict measurement sensitivity. To circumvent this fundamental bottleneck, Stimulated Brillouin Scattering (SBS) techniques utilize nonlinear interactions to significantly boost signal strength, as detailed in the following section.

4. Spectral Extraction Methodologies for SBS Microscopy

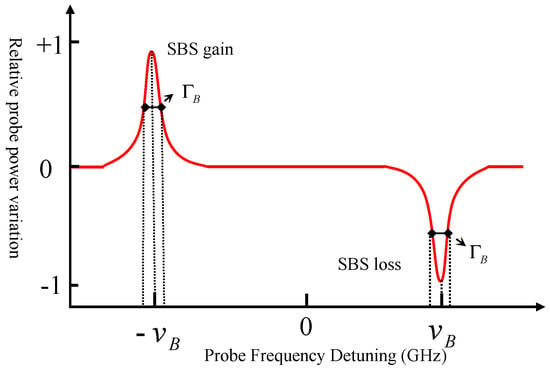

Driven by electrostriction, the interaction between pump and probe beams coherently excites an acoustic field, characterizing the SBS process through probe gain or depletion. In the Brillouin gain regime, the pump Stokes frequency aligns with the probe frequency. Consequently, the generated acoustic wave functions as a traveling diffraction grating. This structure channels energy from the pump to the probe, yielding signal amplification. This stimulated mechanism significantly boosts signal strength compared to SpBS, enabling shot-noise-limited detection and reducing spectral integration times to the millisecond range [19], thereby overcoming the limitation of low acquisition speed. Furthermore, the optical gain and acoustic excitation mutually reinforce each other to establish a positive feedback loop. Conversely, the Brillouin loss scenario corresponds to a probe frequency matching the pump anti-Stokes component. Here, the acoustic field mediates energy transfer away from the probe beam. This effect results in power attenuation. Figure 9 presents a representative SBS spectral profile. Based on pump temporal characteristics, SBS microscopy is categorized into CW-SBS and ISBS. However, conventional SBS often requires high optical power to maintain sufficient SNR, potentially inducing phototoxicity. Despite sharing a fundamental nonlinear physical core, these modalities differ significantly in spectral acquisition and processing strategies. CW-SBS continuously scans the pump-probe frequency detuning to record intensity variations point-by-point, constructing gain and loss profiles via Lorentzian line-shape fitting. In contrast, ISBS employs time-gating techniques to detect the probe time-domain response to a transient phonon field excited by short pump pulses, utilizing Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms to retrieve spectral information. This section elaborates on these distinct spectral extraction paradigms.

Figure 9.

Schematic of a Typical SBS Spectrum; The curve illustrates the stimulated Brillouin gain and loss profiles. The Brillouin frequency shift () is defined by the probe frequency detuning at the peak maximum (or minimum), and the linewidth () corresponds to the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the spectral profile.

4.1. Spectral Extraction Methodologies for CW-SBS Microscopy

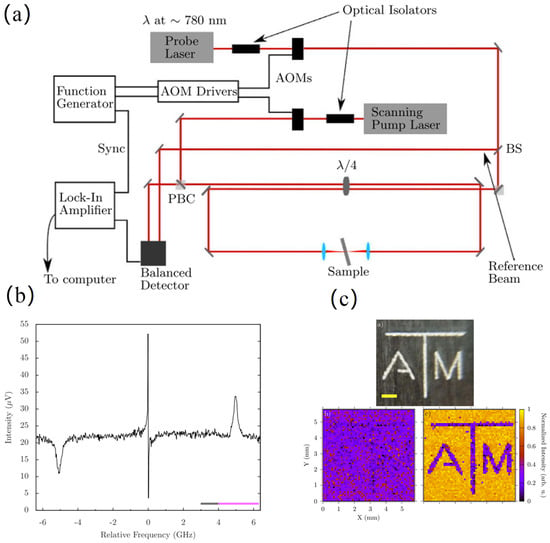

In 2015, Yakovlev et al. [49] realized two-dimensional SBS microscopy. Their setup featured a counter-propagating pump-probe architecture driven by a low-power continuous-wave laser tunable around 780 nm. Regarding spectral extraction, the team acquired signals by scanning frequencies encompassing the SBS gain peak at each pixel, concurrently monitoring non-signal bands to eliminate background interference. Lorentzian fitting of the resulting spectra, combined with theoretical formulations for frequency shift and linewidth, enabled the calculation and validation of the Brillouin properties of water. Figure 10a details the experimental arrangement. A 780 nm laser drives the counter-propagating SBS excitation. Balanced detection paired with lock-in amplification facilitates signal retrieval during XY scanning. Figure 10b plots the aqueous SBS spectrum. Bottom grey and magenta bars demarcate background and signal acquisition windows, respectively. Lateral loss and gain peaks derive from SBS interactions. In contrast, the central feature attributed to absorptive stimulated Rayleigh scattering. Figure 10c renders the final imaging outcome. Pixel-wise mapping of SBS magnitude to grayscale values generates the contrast. Consequently, the aqueous medium exhibits high brightness. Conversely, the logo pattern appears with low intensity.

Figure 10.

(a) SBS Microimaging System Constructed by Yakovlev et al. (b) SBS Spectrum of Water (c) Final Imaging Result.

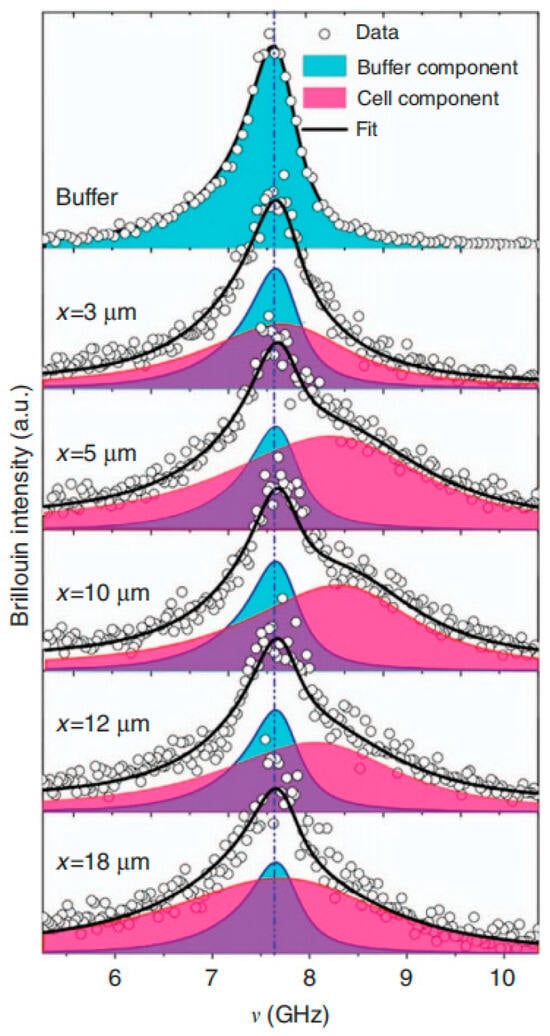

In 2018, Mattana et al. [20] performed the inaugural SBS application on subcellular structures within living cells. The work probed biomechanical distinctions between normal and cancerous phenotypes. A tandem F-P interferometer facilitated the analysis. Short-pass filtering isolated quasi-elastic scattered light for spectral acquisition. The live-cell response diverges from a single-peak profile. Instead, the signal constitutes a superposition of contributions from cellular constituents and the surrounding buffer. The researchers employed multi-peak Lorentzian fitting to deconvolute these contributions, thereby extracting critical parameters including Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth. Figure 11 charts multi-peak fitted spectra across various spatial coordinates. White scatter points map raw live-cell measurements. Red and blue solid traces correspond to fitted curves for cellular and buffer components, respectively. Finally, the black solid line delineates the cumulative dual-component fit.

Figure 11.

Multi-Peak Lorentzian Curve Fitting Results Adopted by Sara Mattana et al.

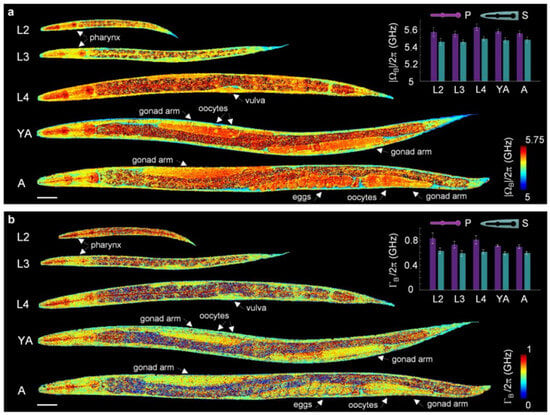

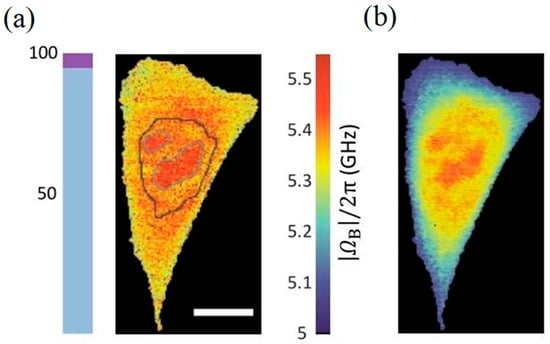

In 2020, Remer et al. [19] applied SBS to quantify pharyngeal mechanics, image viscoelastic responses under hyperosmotic stress, and perform comparative mesoscopic biomechanical imaging of live Caenorhabditis elegans across developmental stages. This method improved pixel dwell times by over an order of magnitude compared to SpBS microscopy, achieving MHz-level spectral resolution. A custom-developed MATLAB algorithm performed dual-Lorentzian fitting on acquired SBS gain spectra, enabling precise pixel-wise extraction of critical mechanical parameters including Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth. Leveraging these high-speed imaging capabilities, Figure 12 displays whole-body distribution maps of these parameters for three larval (L1, L2, L3) and two adult (young adult YA, adult A) stages. Based on viscoelastic contrast, the images clearly resolve anatomical structures such as the pharynx, vulva, gonads (G), and eggs (E).

Figure 12.

SBS Biomechanical Mesoscopic Imaging for Tracking Nematode Development (a) Variation in Brillouin Frequency Shift; (b) Variation in Brillouin Linewidth.

In SBS microscopy, a single voxel typically encompasses diverse biomechanical constituents, yielding Brillouin spectra manifest as superpositions of overlapping Lorentzian peaks. Naive single-peak fitting extracts an averaged mechanical response, introducing substantial spectral artifacts and quantification errors. Addressing this model selection ambiguity, Shaashoua et al. [50] proposed a robust framework integrating information theory with physical constraints to optimize selection among single, standard double, and modified double Lorentzian models. Central to this approach is an initial evaluation based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [51], balancing goodness-of-fit against complexity via the following equation:

Here, denotes the number of spectral data points, the measured spectrum, the fitted signal, and the total parameter count. Models yielding lower values are deemed optimal, achieving the best trade-off between fitting residuals and complexity. To prevent noise overfitting, the method incorporates a physically driven threshold of 207 MHz, derived from the 95% quantile of the frequency difference observed when overfitting pure water samples with a dual-peak model. A dual-peak model qualifies as a valid candidate only if the inter-peak frequency separation exceeds this limit. This constraint ensures that identified multi-peak structures possess genuine physical significance rather than originating from random noise. Applying this framework to SBS data from live NIH/3T3 cells yielded the reconstructed Brillouin frequency shift images in Figure 13, comparing the optimized model selection against forced single-peak fitting. The adaptive framework effectively eliminated downward frequency shift artifacts induced by single-peak fitting, significantly enhancing quantification accuracy for subcellular structures such as the nucleoplasm and nucleoli.

Figure 13.

Reconstructed Brillouin Image of Living NIH/3T3 Cells Based on the Model Selection Framework Proposed by Shaashoua et al. (a) The effect of applying the model selection framework (b) Performance of the enforced single-peak fit.

Holistically, spectral analysis within CW-SBS microscopy revolves around high-precision line-shape modeling. This process targets indirectly mapped gain or loss profiles. Methodological progression extends from elementary single-peak Lorentzian regression to multi-peak decomposition. Such approaches suit complex biological constituents. Physics-driven model selection also plays a crucial role. These strategies incorporate information-theoretic criteria including AIC. Such a trajectory reflects increasing refinement and automation in data processing. These developments significantly bolstered the accuracy and reliability of viscoelastic parameter determination from heterogeneous systems. Cells and tissues benefit largely from this precision. Consequently, a robust foundation for quantitative biomechanical imaging now exists. Nonetheless, a persistent challenge in CW-SBS is the trade-off between signal quality and phototoxicity; high optical power is often required to ensure sufficient SNR. To address this, Li et al. [52] recently introduced a modification to the CW-SBS configuration using squeezed light. By suppressing quantum noise below the shot-noise limit, this method enables high-sensitivity measurements at significantly reduced power levels, rendering the technique less susceptible to the photodamage pitfalls of traditional high-intensity tools. However, even with quantum enhancements, the fundamental requirement of point-by-point frequency scanning in CW-SBS still limits the ultimate temporal resolution. The advent of ISBS microscopy addresses this limitation. This modality captures rapid dynamic processes with superior spatiotemporal resolution. The technique utilizes an impulsive excitation mechanism. Pulsed pump pairs generate acoustic fields. This configuration transforms the analytical framework from frequency-domain fitting to time-domain signal inversion. The subsequent discussion details this specific transition.

4.2. Spectral Extraction Methodologies for ISBS Microscopy

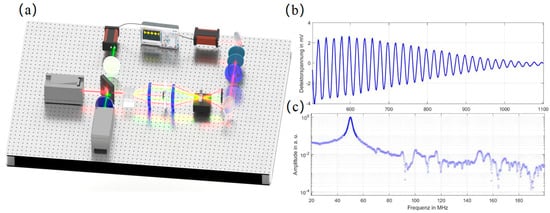

Distinct from the CW-SBS method, ISBS generates an acoustic wave grating through the application of a pair of high-intensity pump pulses. A separate continuous-wave beam is simultaneously introduced for the heterodyne detection of the ISBS signal. Notably, the single-shot time-domain signal measurement time depends primarily on the pulse light repetition rate [53], offering a distinct speed advantage. The time-domain transient acquired at the detector is subsequently converted to the frequency domain via a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to enable the extraction of spectral information. A representative ISBS experimental apparatus and the resulting signal are illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

ISBS Device and Generated Signal (a) Schematic of a Typical ISBS Microscope Experimental Setup (b) ISBS Time-Domain Signal (c) ISBS Frequency-Domain Signal.

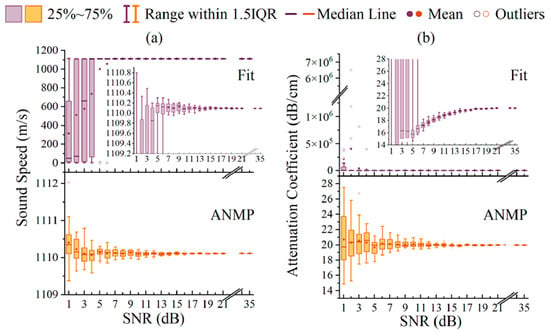

The ISBS technique generates spectra through the excitation of a transient acoustic field and the subsequent probing of its time-domain oscillations. The transformation from time-domain data to frequency-domain spectra relies on the FFT. The core methodologies for backend spectral information extraction remain conceptually congruent with established frequency-domain techniques. Specifically, following the retrieval of the Brillouin gain/loss spectrum, mature frequency-domain analysis strategies are universally employed for the precise extraction of the Brillouin frequency shift and linewidth. For spectra with high signal-to-noise ratios and well-defined profiles, direct peak-finding algorithms offer a computationally efficient means to determine the frequency shift, a method used by Meng Zhaokai et al. [54] in 2017 for rapid mechanical imaging of two-dimensional materials via ISBS-based nonlinear Brillouin microscopy. For more complex spectra or for the concurrent determination of linewidth, least-squares fitting to a Lorentzian profile is widely adopted to maximize information recovery and ensure parametric accuracy, as shown in multiple studies by J. Zhang et al. beginning in 2019 [55,56,57,58]. This procedural bifurcation highlights the primary innovation of ISBS: the use of pulsed excitation for rapid spectral acquisition. The subsequent spectral interpretation remains fundamentally dependent on robust, classical frequency-domain fitting and peak-finding algorithms. Together, these stages form the complete information processing workflow. A paradigm shift in ISBS data processing was introduced in 2022 by the group of Yan Li at Tsinghua University [59] with their adaptive noise-suppressing Matrix Pencil method (MPM) [60]. This novel algorithm fundamentally diverges from FFT-based approaches by extracting spectral parameters directly from the time-domain transient. Fundamentally, MPM models the time-domain ISBS transient—typically an exponentially damped sinusoid—as a sum of complex exponentials. By utilizing singular value decomposition (SVD) of the data matrix, it extracts spectral parameters (frequency and damping rate) directly from the time series without transforming to the frequency domain. This mechanism proves superior to conventional FFT-based analysis, which faces inherent limitations when handling short-lived, decaying signals, particularly under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. Specifically, FFT processing is prone to artifacts such as spectral leakage, broadening induced by window functions, and the ‘picket-fence’ effect due to discrete frequency bins, all of which degrade the precision of peak localization [61,62,63,64]. By obviating the time-frequency transformation, MPM effectively eliminates these artifacts, maintaining high accuracy in frequency shift determination even when the signal quality is significantly compromised. As illustrated in Figure 15, the Matrix Pencil method demonstrates superior performance at low signal-to-noise ratios. While the conventional FFT-based analysis fails for signal-to-noise ratios below 7 dB, the Matrix Pencil method sustains high accuracy and stability in the extracted sound velocity and attenuation coefficients down to a signal-to-noise ratio of 1 dB.

Figure 15.

Sound Velocity and Sound Attenuation Coefficients Extracted by Spectral Fitting and the Matrix Pencil Method Under Different Signal-to-Noise Ratios. (a) The extraction accuracy of medium sound velocity using the FIT method and the ANMP method under different signal-to-noise ratios. (b) The extraction accuracy of medium sound attenuation coefficients using the FIT method and the ANMP method under different signal-to-noise ratios.

In 2023, Yang et al. [65] developed a pulsed stimulated Brillouin scattering microscope. It used a pulsed pump–probe scheme. This enabled long-term mechanical imaging of living zebrafish, C. elegans embryos, mouse embryos, and organoids. For handling high-throughput, high-complexity spectral data, they created a GPU-based parallel computing fitting pipeline. They customized and extended the open-source Gpufit toolkit. Lorentzian and double-Lorentzian fitting models were introduced. This increased data processing speed by over two orders of magnitude. It achieved near-real-time spectral analysis. Crucially, they integrated an intelligent multi-peak identification algorithm. This algorithm used a derivative-based test. It distinguished single from multiple peaks with up to 99.9% accuracy. This ensured reliable mechanical component analysis in complex biological tissues, such as the zebrafish notochord.

ISBS microscopy emerged later than SpBS and CW-SBS. This technique integrates ultrafast pulsed excitation with direct time-domain signal acquisition. Such an architecture addresses critical constraints regarding measurement speed and signal fidelity found in earlier generations. Single-pulse interactions capture broadband spectra. This mechanism circumvents the temporal bottleneck imposed by the point-by-point frequency scanning in CW-SBS. Simultaneously, the stimulated nature of the scattering process yields a signal-to-noise ratio superior to SpBS. Initial spectral interpretation depended on traditional frequency-domain techniques such as Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Conversely, contemporary strategies prioritize time-domain processing. The adaptive noise-suppression Matrix Pencil method exemplifies this shift. Consequently, these algorithmic innovations sustain high imaging speeds while enhancing sensitivity. Precise mechanical characterization of low-SNR scenarios and complex multi-component systems becomes feasible.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

To facilitate the selection of appropriate analysis protocols for specific experimental constraints, Table 1 systematically compares the mainstream spectral extraction algorithms discussed in this review. This comparative assessment reveals that the optimal processing strategy is dictated by the fundamental trade-offs between SNR, acquisition speed, and sample heterogeneity.

Table 1.

Comparative Assessment of Spectral Information Extraction Algorithms.

Overall, this paper provides a systematic review of three typical spectral information extraction methods in Brillouin microscopy—SpBS, CW-SBS, and ISBS. It covers their technical principles, developmental trajectories, and performance characteristics. SpBS technology has continuously improved spectral resolution and acquisition efficiency through hardware innovations such as Fabry–Pérot interferometers and VIPA spectrometers. Leveraging its high signal-to-noise ratio, CW-SBS has driven the refinement of algorithms from single-peak to multi-peak analysis and from empirical fitting to physics-driven model selection. ISBS combines pulsed excitation with time-domain inversion algorithms, laying a solid foundation for high-speed mechanical imaging. Despite significant progress, each method still faces multiple challenges including signal strength, temporal resolution, and system complexity. Looking ahead, spectral information processing in Brillouin microscopy will advance toward greater intelligence and multimodal integration. Data-driven approaches such as deep learning are expected to enable end-to-end parameter extraction, significantly improving automation and robustness. Integration with multimodal information from fluorescence, Raman, and other techniques will construct more comprehensive maps linking mechanics and function. Coordinated optimization of hardware and algorithms will further push the limits of spatiotemporal resolution. With the development of standardized data processing platforms and deeper interdisciplinary collaboration, Brillouin microscopy is poised to transition from a laboratory technique to a practical tool in biomedical diagnostics and materials characterization. This evolution will provide stronger technical support for the dynamic analysis of microscopic mechanical behavior.

Author Contributions

Z.L. (Zhaohong Liu); paper review. X.L., X.S., Z.Y. and Y.G.; review paper collection, organization by topics and editing and manuscript draft. Y.Z. (Yun Zhang), Y.Z. (Yu Zhou) and Q.S.; Supervision. Y.W., Z.L. (Zhiwei Lv) and Y.X.; Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program: 2024YFB3613602, National Natural Science Foundation of China: 62375074 and Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (General Program): F2025202060.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bouvet, P.; Bevilacqua, C.; Ambekar, Y.; Antonacci, G.; Au, J.; Caponi, S.; Chagnon-Lessard, S.; Czarske, J.; Dehoux, T.; Fioretto, D.; et al. Consensus Statement on Brillouin Light Scattering Microscopy of Biological Materials. Nat. Photonics 2025, 19, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, T.G.; Shao, P.; Eltony, A.; Seiler, T.; Yun, S.-H. Brillouin Spectroscopy of Normal and Keratoconus Corneas. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 202, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Scarcelli, G. Mapping Mechanical Properties of Biological Materials via an Add-on Brillouin Module to Confocal Microscopes. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayad, K.; Werner, S.; Gallemí, M.; Kong, J.; Sánchez Guajardo, E.R.; Zhang, L.; Jaillais, Y.; Greb, T.; Belkhadir, Y. Mapping the Subcellular Mechanical Properties of Live Cells in Tissues with Fluorescence Emission–Brillouin Imaging. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, rs5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Gray, K.M.; Stroka, K.M.; Rizvi, I.; Scarcelli, G. Mechanical Characterization of 3D Ovarian Cancer Nodules Using Brillouin Confocal Microscopy. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2019, 12, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatzakis, A.; Song, C.Z.; Allsopp, L.P.; Filloux, A.; Rice, S.A.; Cohen, Y.; Wohland, T.; Török, P. Probing the Internal Micromechanical Properties of Pseudomonas Aseruginosa Biofilms by Brillouin Imaging. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2017, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. Diffusion de la lumière et des rayons X par un corps transparent homogène—Influence de l’agitation thermique. Ann. Phys. 1922, 9, 88–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, R.Y.; Townes, C.H.; Stoicheff, B.P. Stimulated Brillouin Scattering and Coherent Generation of Intense Hypersonic Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 12, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remer, I.; Bilenca, A. Background-Free Brillouin Spectroscopy in Scattering Media at 780 Nm via Stimulated Brillouin Scattering. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, R.; Schumacher, J.; Frank, E.; Ambekar, Y.S.; Zanini, G.; Scarcelli, G. Brillouin Spectroscopy via an Atomic Line Monochromator. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 18572–18581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Speed of Sound Measurement and Mapping in Transparent Materials by Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Microscopy. J. Phys. Photonics 2024, 6, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dil, J.G. Brillouin Scattering in Condensed Matter. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1982, 45, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, J.M.; Randall, J.T. Brillouin Scattering, Density and Elastic Properties of the Lens and Cornea of the Eye. Nature 1980, 284, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, S.; Kojima, T.Y. Quick Measurement of Brillouin Spectra of Glass-Forming Material Trimethylene Glycol by Angular Dispersion-Type Fabry-Perot Interferometer System. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 35, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Yakovlev, V.V. Precise Determination of Brillouin Scattering Spectrum Using a Virtually Imaged Phase Array (VIPA) Spectrometer and Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) Camera. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 70, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, C.; Xie, C.; Guo, Z.; Wang, M.; Wei, B.; Zhang, L.; He, X. Accurate Extraction of Spontaneous Brillouin Scattering Spectra Based on Virtually Imaged Phased Array and Accurate Calculation of Brillouin Shift. Opt. Eng. 2024, 63, 074103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Lan, X.; Luo, N.; Hao, Z.; He, X.; Shi, J. Brillouin Microscopic Imaging of Ex-Vivo Porcine Eye Using VIPA-CMOS-Based Spectrometer. Measurement 2024, 231, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiß, S.; Burau, G.; Stachs, O.; Guthoff, R.; Stolz, H. Spatially Resolved Brillouin Spectroscopy to Determine the Rheological Properties of the Eye Lens. Biomed. Opt. Express 2011, 2, 2144–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remer, I.; Shemsesh, N.; Ben-Zvi, A.; Bilenca, A. High Sensitivity and Specificity Biomechanical Imaging by Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattana, S.; Mattarelli, M.; Urbanelli, L.; Sagini, K.; Emiliani, C.; Serra, M.D.; Fioretto, D.; Caponi, S. Non-Contact Mechanical and Chemical Analysis of Single Living Cells by Microspectroscopic Techniques. Light. Sci. Appl. 2017, 7, 17139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, C.; Sánchez-Iranzo, H.; Richter, D.; Diz-Muñoz, A.; Prevedel, R. Imaging Mechanical Properties of Sub-Micron ECM in Live Zebrafish Using Brillouin Microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaashoua, R.; Bilenca, A. Aperture-Induced Spectral Effects in Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 143702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Lian, J.; Ye, Z.; Yu, X.; Zheng, H.; Yu, Z.; Wen, K.; Yan, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Chirp-Pulse Pair φOTDR. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margueritat, J.; Virgone-Carlotta, A.; Monnier, S.; Delanoë-Ayari, H.; Mertani, H.C.; Berthelot, A.; Martinet, Q.; Dagany, X.; Rivière, C.; Rieu, J.-P.; et al. High-Frequency Mechanical Properties of Tumors Measured by Brillouin Light Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 018101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammon, P.H.; Kiefte, H.; Clouter, M.J.; Denner, W.W. Elastic Constants of Artificial and Natural Ice Samples by Brillouin Spectroscopy. J. Glaciol. 1983, 29, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, J.; Mroz, B.; Mielcarek, S.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Trzaskowska, A. High Resolution Brillouin Spectroscopy of the Surface Acoustic Waves in Sb2Te3 van Der Waals Single Crystals. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rix, J.; Uckermann, O.; Kirsche, K.; Schackert, G.; Koch, E.; Kirsch, M.; Galli, R. Correlation of Biomechanics and Cancer Cell Phenotype by Combined Brillouin and Raman Spectroscopy of U87-MG Glioblastoma Cells. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20220209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edginton, R.S.; Mattana, S.; Caponi, S.; Fioretto, D.; Green, E.; Winlove, C.P.; Palombo, F. Preparation of Extracellular Matrix Protein Fibers for Brillouin Spectroscopy. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2016, 115, e54648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.H.; Chernyak, D. Brillouin Microscopy: Assessing Ocular Tissue Biomechanics. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheburkanov, V.; Keene, E.; Pipal, J.; Johns, M.; Applegate, B.E.; Yakovlev, V.V. Porcine Vocal Fold Elasticity Evaluation Using Brillouin Spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2023, 28, 087002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adichtchev, S.V.; Karpegina, Y.A.; Okotrub, K.A.; Surovtseva, M.A.; Zykova, V.A.; Surovtsev, N.V. Brillouin Spectroscopy of Biorelevant Fluids in Relation to Viscosity and Solute Concentration. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 062410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheburkanov, V.; Du, J.; Brogan, D.M.; Berezin, M.Y.; Yakovlev, V.V. Toward Peripheral Nerve Mechanical Characterization Using Brillouin Imaging Spectroscopy. Neurophotonics 2023, 10, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruidze, P.; Chayleva, E.; Weninger, W.J.; Elsayad, K. Brillouin Scattering Spectroscopy for Studying Human Anatomy: Towards in Situ Mechanical Characterization of Soft Tissue. J. Eur. Opt. Soc.-Rapid Publ. 2023, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynina, E.A.; Zykova, V.A.; Zhuravleva, I.Y.; Kuznetsova, E.V.; Surovtsev, N.V. Brillouin Spectroscopy of Medically Relevant Samples of Bovine Jugular Vein and Pericardium. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 321, 124692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedborough, D.S.; Jackson, D.A. Brillouin Scattering Study of Gelatin Gel Using a Double Passed Fabry-Perot Spectrometer. Polymer 1976, 17, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, K.J.; Yarger, J.L. Brillouin Imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 061903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Xie, C.; Wu, Y.; Wei, B.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; He, X. Interference Cancellation Analysis of Output Spectrum of Virtual Image Phased Array (VIPA) and Application of VIPA in Spontaneous Brillouin Backscattering Measurement. Appl. Phys. Express 2023, 16, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, G.; Polacheck, W.J.; Nia, H.T.; Patel, K.; Grodzinsky, A.J.; Kamm, R.D.; Yun, S.H. Noncontact Three-Dimensional Mapping of Intracellular Hydromechanical Properties by Brillouin Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 1132–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, A.; Zhang, J.; Shao, P.; Yun, S.H.; Scarcelli, G. High-Extinction Virtually Imaged Phased Array-Based Brillouin Spectroscopy of Turbid Biological Media. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 203701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, G.; Lepert, G.; Paterson, C.; Török, P. Elastic Suppression in Brillouin Imaging by Destructive Interference. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Traverso, A.J.; Yakovlev, V.V. Background Clean-up in Brillouin Microspectroscopy of Scattering Medium. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, Z.; Meng, Z.; Traverso, A.J.; Yakovlev, V.V. Brillouin Spectroscopy as a New Method of Screening for Increased CSF Total Protein during Bacterial Meningitis. J. Biophotonics 2015, 8, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepert, G.; Gouveia, R.M.; Connon, C.J.; Paterson, C. Assessing Corneal Biomechanics with Brillouin Spectro-Microscopy. Faraday Discuss. 2016, 187, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Niu, H.; Zhu, L.; Ning, Y. Elastic modulus measurement based on virtual image phase array confocal Brillouin spectroscopy technology. Infrared Laser Eng. 2021, 50, 20200265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.A.; Cathala, C.; Bevilacqua, C.; Feletti, L.; Prevedel, R.; Lashuel, H.A.; Radenovic, A. Self-Driving Microscopy Detects the Onset of Protein Aggregation and Enables Intelligent Brillouin Imaging. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulton, C.G.; Mahmodi, H.; Arnold, M.D.; McAlary, L.; Ooi, L.; Kabakova, I. Statistical Data Analysis Methods in Brillouin Spectroscopy: Tutorial. APL Photonics 2025, 10, 061101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.M.P.; DiaVertex, J.M.B. Vertex component analysis: A fast algorithm to unmix hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 43, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballmann, C.W.; Thompson, J.V.; Traverso, A.J.; Meng, Z.; Scully, M.O.; Yakovlev, V.V. Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Microscopic Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaashoua, R.; Levy, T.; Rotblat, B.; Bilenca, A. Enhancing Mechanical Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Imaging with Physics-Driven Model Selection. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2301054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.E.; Neath, A.A. Akaike’s Information Criterion: Background, Derivation, Properties, and Refinements. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cheburkanov, V.; Yakovlev, V.V.; Agarwal, G.S.; Scully, M.O. Harnessing Quantum Light for Microscopic Biomechanical Imaging of Cells and Tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2413938121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Improvement of Gain and Spatial Resolution for Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Scattering Microscopy. Photoacoustics 2025, 42, 100696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballmann, C.W.; Meng, Z.; Traverso, A.J.; Scully, M.O.; Yakovlev, V.V. Impulsive Brillouin Microscopy. Optica 2017, 4, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, B.; Koukourakis, N.; Czarske, J.W. Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Microscopy for Non-Contact, Fast Mechanical Investigations of Hydrogels. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 26910–26923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, B.; Koukourakis, N.; Guck, J.; Czarske, J. Nonlinear Microscopy Using Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Scattering for High-Speed Elastography. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 4748–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, D.; Boehm, J.; Liebig, L.; Koukourakis, N.; Czarske, J.W. Single-Shot Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Microscopy by Tailored Ultrashort Pulses. J. Eur. Opt. 2025, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.P.; Doktor, D.A.; Scully, M.O.; Yakovlev, V.V. Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Spectroscopy for Assessing Viscoelastic Properties of Biologically Relevant Aqueous Solutions. In Proceedings of the Optical Elastography and Tissue Biomechanics VIII, SPIE, Online, 6–12 March 2021; Volume 11645, pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, M.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Sensitive Impulsive Stimulated Brillouin Spectroscopy by an Adaptive Noise-Suppression Matrix Pencil. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 29598–29610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Sarkar, T.K. Matrix Pencil Method for Estimating Parameters of Exponentially Damped/Undamped Sinusoids in Noise. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1990, 38, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Suonan, J. A Fast Algorithm to Estimate Phasor in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheshyekani, K.; Fallahi, G.; Hamzeh, M.; Kheradmandi, M. A General Noise-Resilient Technique Based on the Matrix Pencil Method for the Assessment of Harmonics and Interharmonics in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinjab, F.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhao, X.; Nagashima, Y.; Ideguchi, T. Enhanced Spectral Resolution for Broadband Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, X.; Qin, K. Parameters Estimation Algorithm for the Exponential Signal by the Interpolated All-Phase DFT Approach. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Actiev Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), Chengdu, China, 19–21 December 2014; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Bevilacqua, C.; Hambura, S.; Neves, A.; Gopalan, A.; Watanabe, K.; Govendir, M.; Bernabeu, M.; Ellenberg, J.; Diz-Muñoz, A.; et al. Pulsed Stimulated Brillouin Microscopy Enables High-Sensitivity Mechanical Imaging of Live and Fragile Biological Specimens. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.