Abstract

Thermoluminescence has a long and successful history in applied radiation dosimetry, as well as in a wide range of other applications and basic research. However, there is a dichotomy that, despite the many commercial successes, there continue to be entrenched systematic errors in data collection, signal processing, and models. This overview offers suggestions to address these issues. Improving initial data collection is certainly feasible and may offer deeper insights into the potential mechanisms of thermoluminescence. There is an extremely complex challenge in suggesting and confirming models for lattice sites that generate luminescence signals. Currently, such models are highly speculative and simplistic. In reality, they should involve not only immediate lattice sites but also extremely long-range interactions. Weaknesses in data collection and models impact and generate errors in the extraction of activation energies and frequency factors that are routinely ascribed to data analysis. Overall, it is possible to suggest ways to improve data collection and slightly improve modelling of relevant lattice sites and parameters such as their activation energies, but in reality, these factors will always be speculative and imprecise. Fortunately, this does not inhibit the extension of the technique into other areas of application, but the suggested improvements will enable greater diversity.

1. Introduction

Thermoluminescence (TL) has proved to be an extremely valuable tool across a wide range of topics, from its initial use in radiation dosimetry and archaeological dating to an immense number of applications including geology (including dating), anti-counterfeiting, information storage, sensors, etcetera. TL has offered insight into the extremely difficult task of attempts to model and categorise lattice sites and defect interactions in various host insulating materials. It has also acted as a catalyst for improvements in the requisite spectroscopy and has led to significant enhancements in detector performance. Over its long history, numerous TL overviews and discussions have emerged, along with multiple textbooks [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and many thousands of detailed research articles. To illustrate the scale of the literature, it was initially estimated in the 1950s that there were over 500 TL-related research articles per year, and this rate has greatly increased over the last 70 years. A Google Scholar search lists 2920 articles containing the word “thermoluminescence” since the beginning of 2025 alone. It is also historically unique in that the first discussion of the process was presented by Robert Boyle (of gas law fame) in 1663 when he reported that a diamond that had been exposed to sunlight emitted light when viewed in darkness against his warm body [17]. The name and description of an irradiation process first appeared following an experiment with a sample irradiated with an electron beam before heating and optical measurement [18,19]. Consequently, one might assume that, given such a vast and successful body of literature, the processes are fully understood and the experimental data are entirely reliable. Surprisingly, this is not the case. The data collection methods are invariably flawed in many aspects, such as temperature lag, spectral overlap, retrapping assumptions, and the neglect of long-range interactions. Additionally, the proposed mechanisms of the process are vastly idealised and/or deliberately oversimplified. Basically, we remain tied to the very early attempts at modelling which, whilst sensible at the time, fail to appreciate the wealth of data that has since accumulated. Hence, analytical processing of the data is not perfect (and potentially actually wrong). Models oversimplify, or exclude, the immense diversity of sites that exist, and we fully ignore the documented evidence of extremely long-range electronic interactions and minimise the effects of large-scale defects, such as dislocations, grain, or phase inclusions, and the influence of surface contaminants. This is inevitable, as we do not use experimental techniques that might offer detailed site structures, and therefore must rely on imaginative modelling to interpret them. This is not a criticism, just reality. However, it implies that virtually all the “detailed” site models and kinetics of TL are vastly oversimplified. An immense body of literature on these topics does not validate them. Instead, it generates a false impression of understanding the science of TL and inhibits the reappraisal of historical models and analyses. Unfortunately, any attempts to diverge from the “popular” models will lower the success rate with journal reviewers. Hence, errors become entrenched and are compounded by the fact that the topic has been successfully applied for about 70 years—similar to historical beliefs about phlogiston and ether. Complacency understandably exists as, despite intrinsic errors, the approach has been robust and has offered extremely helpful data in the various fields in which it is exploited. Therefore, this article will initially focus on the acquisition of data, as this will reveal significant errors and uncertainty in “standard” modelling and, in some cases, unequivocally demonstrate where it is oversimplified, making the subsequent mathematical treatments questionable. Practical usage is far more secure, as interpretation is often feasible without detailed knowledge of the structure of lattice sites and charge movements in the host materials. Therefore, for radiation dosimetry or archaeological and geological dating, thermoluminescence data offer valuable information. By contrast, attempts to describe the detailed mechanisms of TL, and especially the key lattice sites, can be seriously flawed. The comments here may stimulate a new generation of improvements in current data collection techniques, data processing, and speculative models. Our hope is that it will also trigger completely new routes to analyse the structures of the key lattice sites, and their more extensive environments.

Similar situations have always existed across all of life and science. Top chefs skilfully use ingredients, herbs, and processing for taste and appearance without understanding the molecular chemistry. Identical patterns occur across most successful technologies where usage predates understanding. Effective metal working of copper, bronze, steel, glass, etcetera, all preceded the science. Metallurgists focused on the production performance of weapons and other applications for several thousand years before science contributed to help control strength, anti-corrosion, sword blade sharpness, etc. Modern science helps, but rarely in ways we fully understand [20]. Photography commenced ~200 years ago, but the chemistry of how light could change materials, generate lattice defects, and lead to photographic images was almost pure guesswork. This sufficed for two centuries, whilst partial knowledge steadily enabled improvements in quality, response speed, addition of colour, etcetera. A detailed understanding of the science and chemistry of lattice sites has slowly developed. Commercially, this is now irrelevant, as the photographic process has mostly been displaced by electronic image recording.

The following sections will review some historic examples of TL and how it has been possible to enhance the quality of the data. Whilst some changes have been very expensive, their benefits were readily justified. Less obvious are hidden weaknesses and equipment errors that may be unfamiliar to those who have only used commercial equipment. Interpretation of TL data in terms of activation energies and frequency factors are similarly very sensitive to both data collection and models. The final conclusions will explain why we will never achieve a fully detailed model of the lattice site structures and how they interact. However, with a deeper understanding of TL data and improvements in experimentation, one can confidently assume new applications will be envisaged.

Rather than just using commercial equipment, we have had considerable experience in the design and construction of luminescence systems, along with the many subtle and unexpected pitfalls that exist. This has highlighted for us major problems in defining the true sample temperature, errors in spectral analysis, and potential improvements using existing systems. This has led to major improvements in photomultipliers and techniques to significantly enhance the sensitivity of existing equipment. We will not cite articles which have erred in any of these ways, but since many advances may be unfamiliar in the TL literature, we will indicate corrections that are required and list detection improvements that have been achieved. Such details are rarely mentioned, and therefore, we will highlight them, as many could be exploited for thermoluminescence dosimetry and analysis of defect sites.

2. The Aims and Structure of This Overview

Improvements in collection of thermoluminescence data are essential to avoid errors in processing and interpretation from both early and current data. Numerous research groups and laboratories worldwide have devoted substantial work to advancing thermoluminescence data acquisition techniques, optimising detector sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratios, and temperature control precision [21,22,23]. Their contributions have laid a solid foundation for standardised data collection protocols, and a variety of mature commercial thermoluminescence measurement systems are now available on the market to meet the diverse needs of academic research and industrial applications. Our examples are somewhat personal, as they highlight features of equipment we have used or designed, in addition to our errors and advances. In particular, in the 1990s, a move from photomultiplier tubes to imaging photon detectors (IPDs) significantly improved our spectral sensitivity by over 800 times compared with equipment that was then in use. Although far more expensive, the vastly superior performance revealed quite unexpected features of thermoluminescence spectral data. In hindsight, the investment was academically fully justified, as superior equipment attracts collaborators of diverse backgrounds and leads to a profusion of co-authored publications and advances in understanding.

The following sections will initially catalogue some inherent problems in the acquisition and processing of data. Many are trivial, but others are subtle and significant, with their presence not being exploited or recognised, and with the same errors persistently appearing in the current literature. Unfortunately, we rarely question the validity of our own data but have often benefitted from students and other friends who indicated our mistakes. The text will include some less familiar but important features of equipment. It will highlight the benefits of good spectral resolution and the ability to operate at low heating rates.

3. Very Basic Thermoluminescence Glow Curves

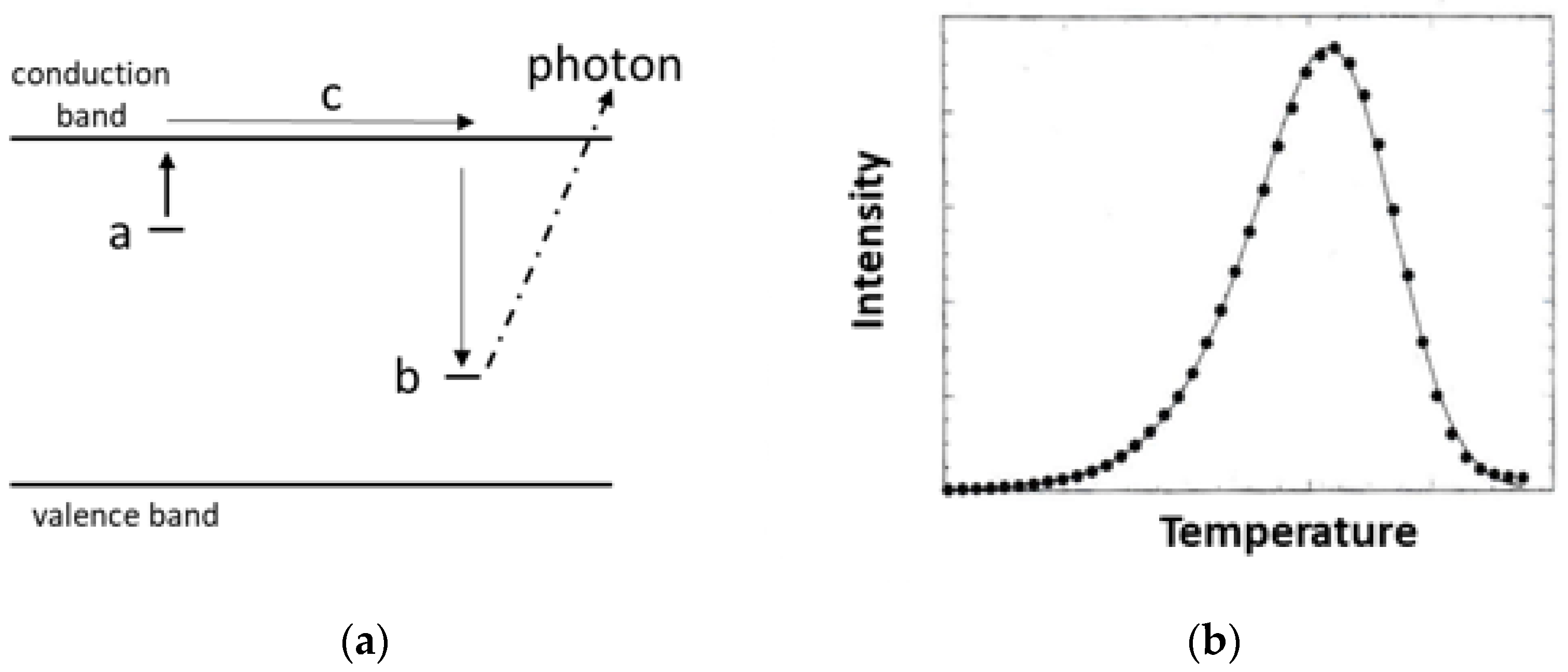

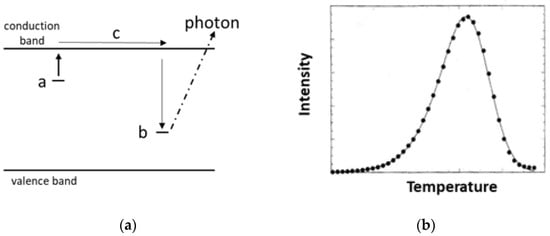

The initial simplistic model for the thermoluminescence process considers an insulator with valence and conduction bands, with defect sites adding both a shallow electron trap and a hole trap (Figure 1a). Initially no charge is trapped. Radiation produces ionisation, and the electron goes to trap a and the hole moves to b. We assume the concentration of occupied a type sites is proportional to the radiation dose. To stimulate thermoluminescence, the sample is heated at a linear rate in temperature. Escaping electrons move via the conduction band and find site b. The recombination energy released during this trapping is emitted as a photon. This generates the thermoluminescence glow curve sketched in Figure 1b. Ideally the integrated intensity of the curve monitors the radiation dose, and the shape and peak temperature can be evaluated to define the depth (energy below the conduction band edge) of trap a and an escape frequency term. Whilst oversimplistic, it can still offer useful radiation dosimetry. Generally, one cites the peak temperature to identify which traps are being discussed and the area under the curve (or peak intensity) to identify the radiation dose. In real systems with many trap types, peaks will overlap on the integrated polychromatic spectral intensity plot. Hence, the next phase has been to spectrally resolve the component emission features. Invariably, this has indicated several emission bands. Even greater detail emerges through the line spectra of elements, such as the rare earths. Rare earth (RE) data can help to model the structure of trapping sites. However, spectrally resolved glow curves can differ for every single emission line (even of the same RE dopant). Potential models to explain these features will be discussed.

Figure 1.

(a) After ionisation, electrons are trapped at a type sites and holes on b ones. On heating, trapped electrons escape and move through conduction band c. When they reach the b sites, the energy release is by a photon. This is a useful initial model, but it is overly simplistic. (b) An idealised intensity pattern of the thermoluminescence as the sample is heated. Potentially, both the peak height and the area under the curve offer a measure for dosimetry.

3.1. Temperature Measurement

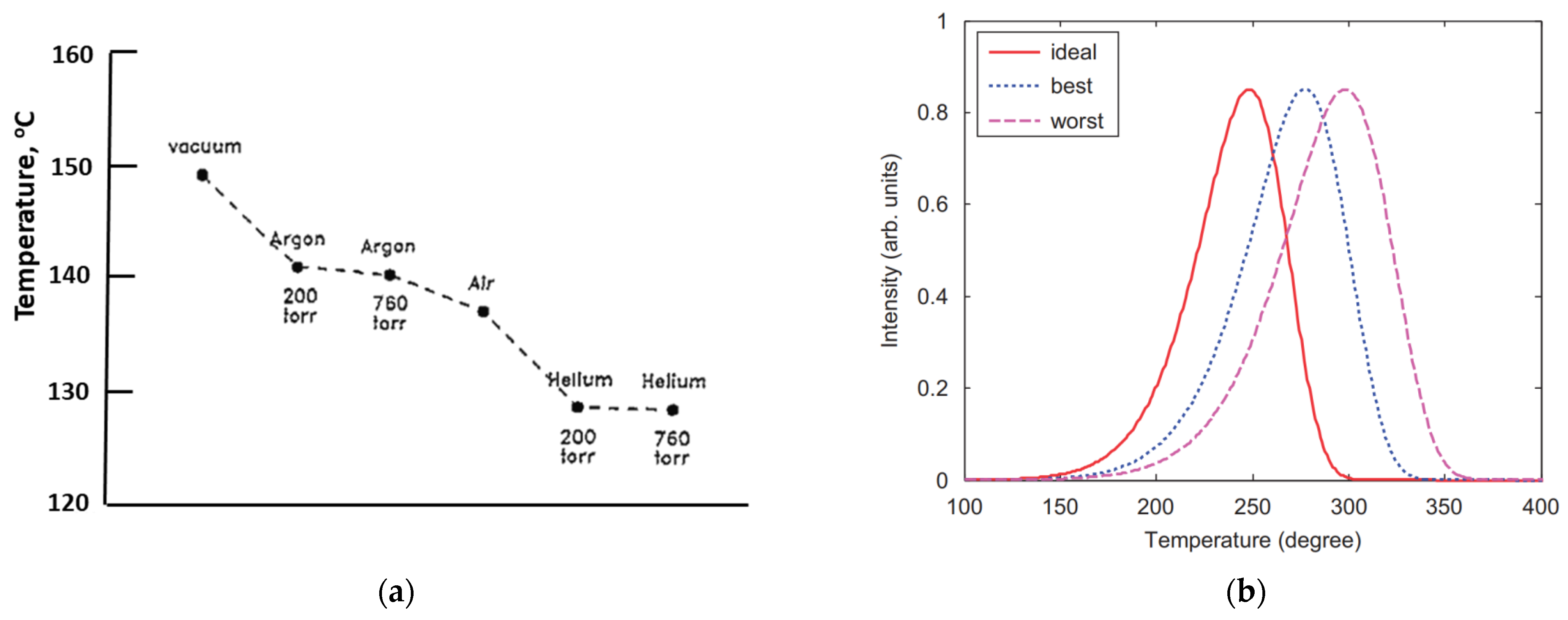

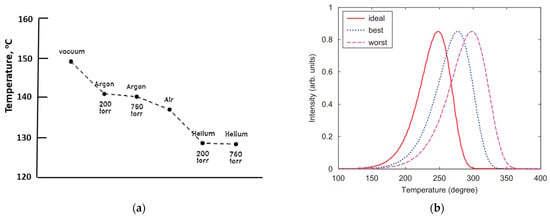

The materials are insulators, both electrically and thermally, and the temperature is monitored by a thermocouple fixed to the heater. There are temperature gradients across the sample, so light emission comes from a sample surface at a lower temperature than the heater (although the heater value is always cited in the data). Many articles discuss this temperature error and ways of reducing it (e.g., by using a thermally conductive background gas). The error is clearly worse at high heating rates, which are, unfortunately, normally a requirement to compress the emission into a short time to optimise the signal-to-background noise ratio. If the heater emits light, one may add filters to reduce the background heater emission (black-body emission). The scale of these problems will vary with different systems, sample size, and whether the sample is a powder or a crystal. The signals are also considerably modified if there are several electron traps, and/or a variety of recombination sites. In practice, many such factors exist. Some articles have addressed the problem of divergence between the heater and sample temperatures [24,25,26]. Figure 2a offers one example of the scale of temperature lag, showing the heater temperature at which the peak is detected when using different heat exchange gases. Initially, with an excellent thermally conductive environment (helium), the sample temperature appears at ~130 °C (i.e., probably with only a minor temperature lag), but in a vacuum, it is behind by ~20 degrees. Errors increase with fast heating rates and higher temperature glow peaks. With a heater strip temperature of 350 °C, the true sample surface temperature can be between 50 and 100 degrees cooler (i.e., a considerable percentage error in centigrade). The divergence increases with both high heating rates and high temperature peaks. In scientific terms, temperatures are measured in Kelvin units, so the true percentage error is smaller (but still significant). Unfortunately, such error variations are unlikely to be considered during kinetic analyses, which will use the heater value. The literature cites the apparent peak temperatures. Figure 2b indicates how peak temperatures can differ depending on the thermal contact with the heater. A further complication from temperature gradients across the sample is that the peak shape becomes broader than theory predicts, due to different parts of the sample emitting at different measured temperatures, both across the heater strip and within the sample, leading to errors in analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Peak position, in °C, for the same TL peak recorded in different gas atmospheres with various degrees of thermal coupling. The weakest thermal coupling occurred in a vacuum, and coupling increased with the thermal conductivity of the gas used and the pressure. The data were recorded at a heating rate of 5 degrees per second [24,25]. (b) A simple example showing how shifts in TL peak shape and temperature differ with thermal contact from good to poor (NB: “best” is still far from perfect) [26].

Whilst helium is most effective, it is never used in routine data collection, but argon or nitrogen are sometimes used, which have similar heat conductivity. Such data are significantly equipment-sensitive. The real bonus of thermoluminescence dosimetry is that even “incorrect and distorted” data may be perfectly adequate for dosimetry, but they introduce significant errors in both site modelling and kinetics. The errors are system-dependent, and hence introduce further problems when comparing data. Figure 2b indicates how thermal coupling can modify the signal temperature. An example with the same quartz sample, with a nominal peak near 110 °C, differed by over 60 degrees across data from six laboratories. All were recorded at the same high heating rate, but none were in agreement [27].

Not only do such diverse numbers influence analyses of trap depth, etc., but critically, the temperature errors nullify many comparisons with data from alternative experimental procedures, such as optical absorption or paramagnetic resonance. It may not even be clear if the same feature is being studied. This is unfortunate, as TL will never, by itself, offer a site model, whereas ESR (EPR) and ENDOR [28,29,30] have shown excellent correlation between explicit structures and TL peaks. Potentially, one might also correlate TL data with other types of measurement, such as optical absorption, which are often quite specific. Difficulties in comparison can also emerge from the fact that TL is highly sensitive—often more so than the comparison techniques.

Absorption data are also useful, as it is known that TL intensity can be reduced by absorption of the emitted light within the sample (e.g., signals can differ for the same volume of material when used as thin disks versus thicker columns). Absorption will further modify both total intensities and the relative strengths of different emission bands.

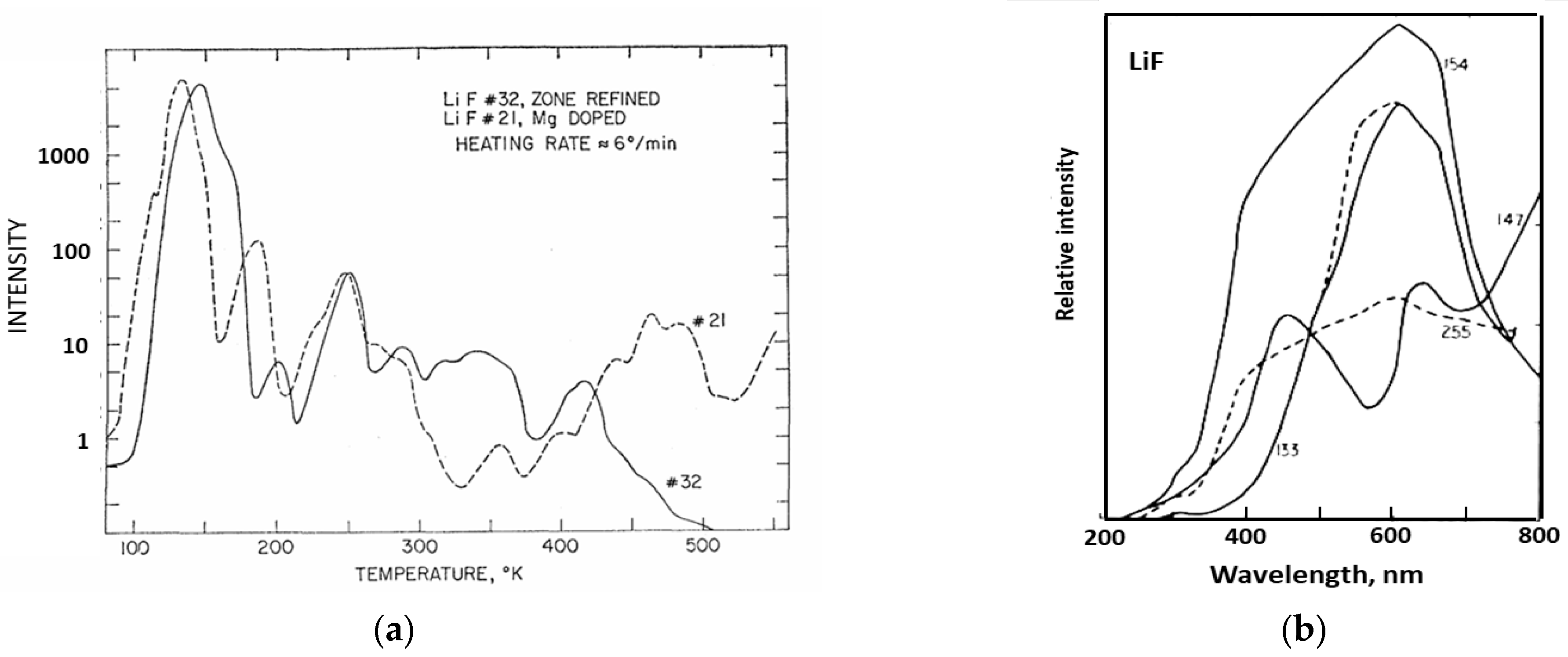

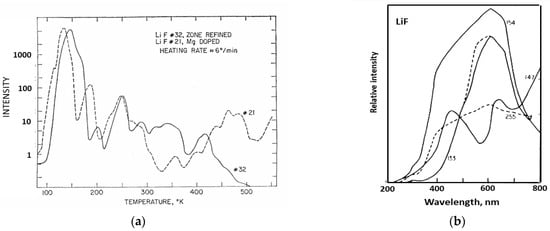

3.2. Optical Detection

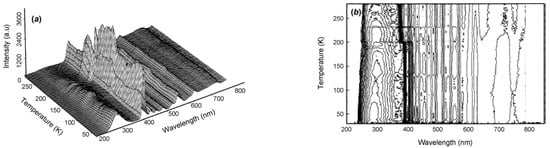

Photomultiplier tubes offer very good sensitivity for photon counting, and they have quite a wide spectral range, which implies they can simultaneously detect emission at wavelengths from every trapping site in an insulator host. In dosimeter applications with a single trapping site, this a minor problem, as polychromatic emission merely adds to the integrated signal. However, if there are several emission sites, their efficiency will be temperature-sensitive, and it may be necessary to use a reduced spectral detection range (e.g., by a filter or spectrometer). Ideally one requires total spectral resolution so one can select a specific emission band, especially if there are several sites. Polychromatic recording will subsume them into a single signal. Historically, pioneering work of spectral TL was carried out by the group of Dr Paul Levy in Brookhaven using scanning monochromators [31]. Their data revealed both broad band signals and line spectra (e.g., from rare earth dopants). The Brookhaven group also extended TL recordings to low temperatures. Figure 3a shows low-temperature TL peaks from LiF, with quite different TL peaks for a sample that had been zone-refined in a nitrogen atmosphere and one doped with Mg [32]. Even with an initially low-grade spectral resolution (Figure 3b), one senses very clear spectral differences in the different temperature regions [33]. These are probably the very first examples of LiF low-temperature TL data. Their important message is that polychromatic data hide a vast amount of information (partially revealed by wavelength scanning systems).

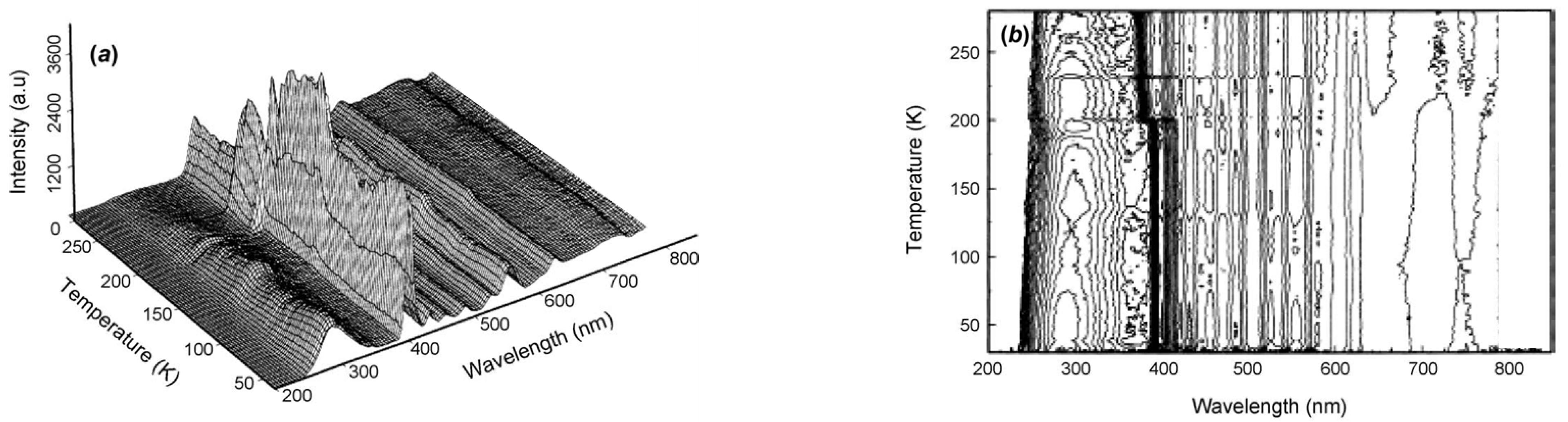

Figure 3.

(a) The first example of low-temperature TL measurements of LiF [32]. (b) Examples of the first attempt at low-temperature emission spectra of LiF for peaks near 133, 147, 154, and 255 K [33].

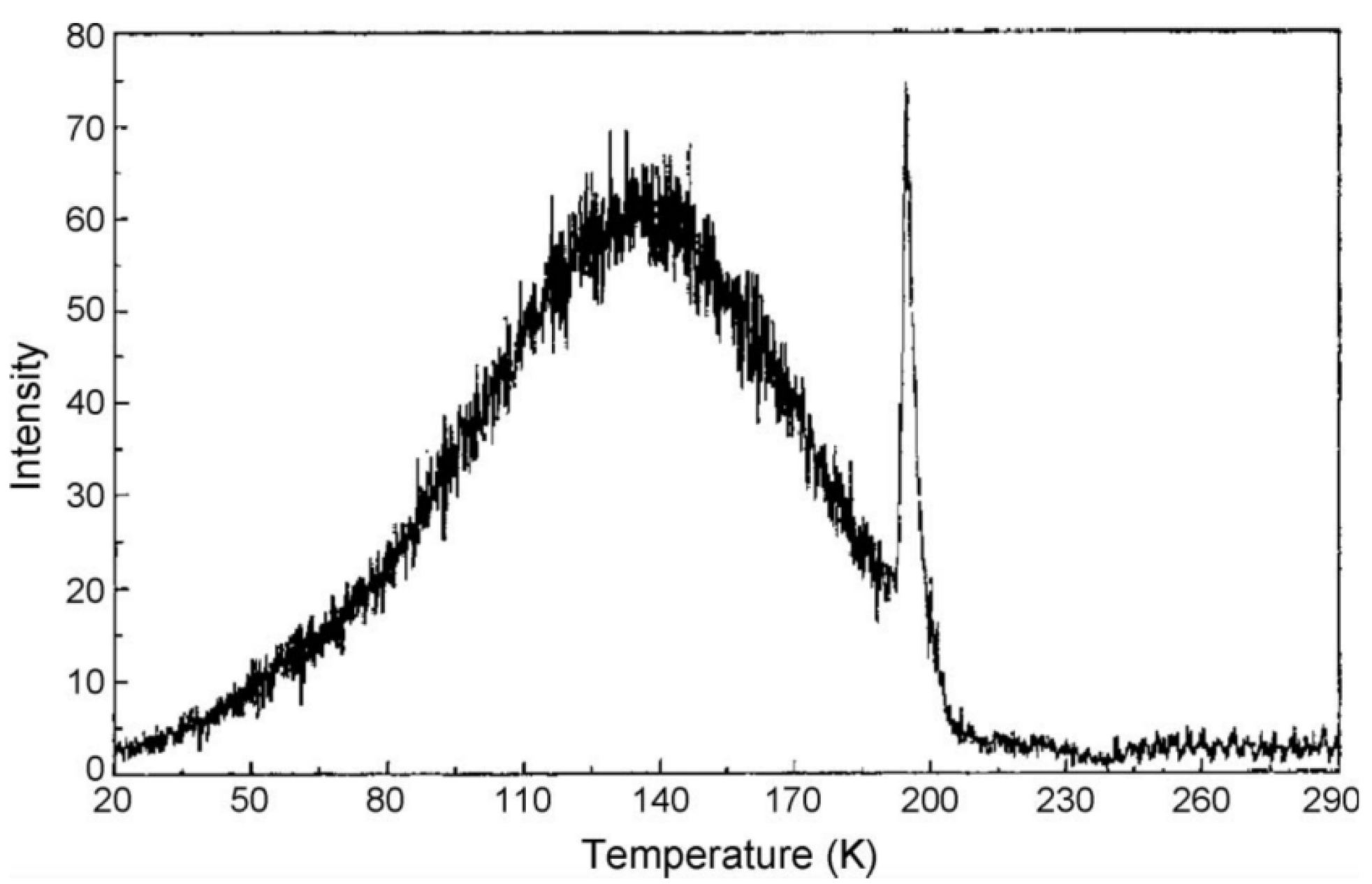

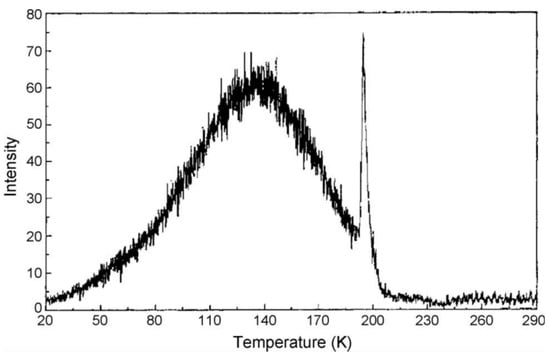

The major improvement gained by spreading spectra across an IPD (imaging photon detector) meant simultaneous spectral resolution and the ability to use lower heating rates, resulting in precise temperature accuracy. As a bonus, one can record phase transitions in insulators by noting discontinuities in both signal intensity and spectra. Indeed, the first example was fortuitous, as it occurred during a luminescence study of an optical fibre, which happened to contain trapped carbon dioxide (CO2 was involved in the production process). At a low temperature of ~197 K, CO2 undergoes a sublimation phase transition from solid to gas. On heating, this induces an immense pressure change, which completely distorts both the host lattice transition and the electronic transition probabilities. This was clearly observed as a luminescence intensity spike across the entire spectrum, as shown in Figure 4 [34]. Such trapped impurity features, both from CO2 and the many different phase transitions of ice, were subsequently seen in a wide range of insulators at low temperature [35,36,37]. Surprisingly, the data reveal that significant quantities of atmospheric moisture can diffuse into the surfaces of Nd:YAG laser material (Figure 5). Phase transitions of CO2 and water ice cause pressure changes that induce spectral and intensity steps in both line and broad band luminescence, along with changes in X-ray diffraction parameters [35,36,37]. Such events are obvious at low temperatures in many minerals and insulating crystals. They also emerge in data at temperatures of “normal” X-ray crystal phase transitions. Many early examples of optical detection of phase transitions were reviewed [35], along with additional later examples from a variety of minerals and hosts [36,37].

Figure 4.

Thermoluminescence of an optical fibre containing CO2. An intensity spike anomaly exists across the entire spectrum at ~197 K, the temperature of the sublimation phase transition of CO2 from solid to gas [34].

Figure 5.

(a) An example of low-temperature TL from Nd:YAG, and (b) the corresponding contour map. Phase transitions of trapped ice and CO2 (which had diffused in from the surface) induced both intensity steps and wavelength shifts due to pressure changes that occurred during phase transitions. Obvious features appeared near 197 and ~230 K [36].

3.3. TL Relevance of Detection of Phase Transitions

Whilst interesting from the viewpoint of crystallography, the more important observation is that luminescence has revealed a wide range of phase change features from hosts and impurities. This occurs in many of the materials previously considered in prior thermoluminescence studies as being of a uniform and unchanging single-phase structure. Although the preceding examples of low-temperature luminescence evidenced the presence of phase transitions of CO2 and ice, which may initially not seem relevant to TL dosimetry above room temperature, their phase changes altered the lattice parameters and modified the luminescence emission intensities and spectra. The data are therefore important, as there are many crystalline phases of ice. In a range of examples using TL, RL, and CL, all show that water can be trapped, not merely as individual molecules, but in sufficiently large clusters that can be structured to exhibit the many different ice phases as microcrystalline particulates. Water vapour is a universal surface contaminant and is clearly present, not just in the atmosphere, but also in large quantities in many minerals, and even in synthetic hosts (e.g., Nd:YAG). Evidence of their phase transitions unequivocally implies they are not just isolated molecules on grain boundaries, dislocations, or surfaces (such in-diffusion is especially relevant for powder materials, including the many used in TL dosimetry). However, such possibilities are completely ignored in virtually all of the TL literature. Indeed, dopants and impurities are invariably treated as isolated ions occupying lattice sites. The only literature exceptions to consider clustering are when the trap and recombination site are intimately linked. This is highly desirable, since it guarantees an extremely efficient TL process. A classic example of such association is the model of the LiF-based material termed TLD 100 [38,39,40,41]. Clustering of dopants has also been proposed in numerous materials. An example of rare-earth impurities in LaF3 that cluster into triplets will be mentioned, together with evidence of very long-range impurity interactions.

3.4. Subtleties of Diffraction Gratings

An inherent problem is that spectra resolved with a diffraction grating at a wavelength of 900 nm can be generated not only by first-order 900 nm diffraction, but also by second-order 450 nm and third-order 300 nm diffraction. Photomultiplier sensitivity is strongly wavelength-dependent, so a weak third-order 300 nm signal can totally dominate a true 900 nm signal. In scanning systems, signals are acquired sequentially in wavelength, and therefore, for a 200-point spectrum, more than 99.5% of the signal is rejected. There is further loss during scanning when returning to the starting point. In Sussex in the 1990s, an expensive alternative to a scanning monochromator was to use an imaging photon detector (IPD), where every wavelength is recorded simultaneously with high spectral resolution [42,43]. The equipment prevented order overlap by using two such devices to cover different spectral ranges. Furthermore, the spectrometers had low f numbers to increase intensity. This increased the sensitivity compared with scanning monochromator systems by more than 800 times. IPD detection has very rapid time resolution, so one can also track luminescence decay, etcetera [42]. Resolution of the decay properties of different sites has potential value for site modelling.

Such TL studies had an unexpected, but related, impact on stimulating improvements in photomultiplier performance [44,45,46] and IPD response times [47] and led to many collaborations across a range of disciplines.

The subsequent introduction of semiconductor photon sensors for conventional TL spectral analysis offers a lower-cost alternative that extends the detection range further into the infra-red than is feasible with most photomultiplier tubes. Note, however, that commercial equipment may not resolve the overlap of diffraction orders (this is clearly apparent in some journal literature, which has failed to recognise line spectra in both first- and second-order measurements).

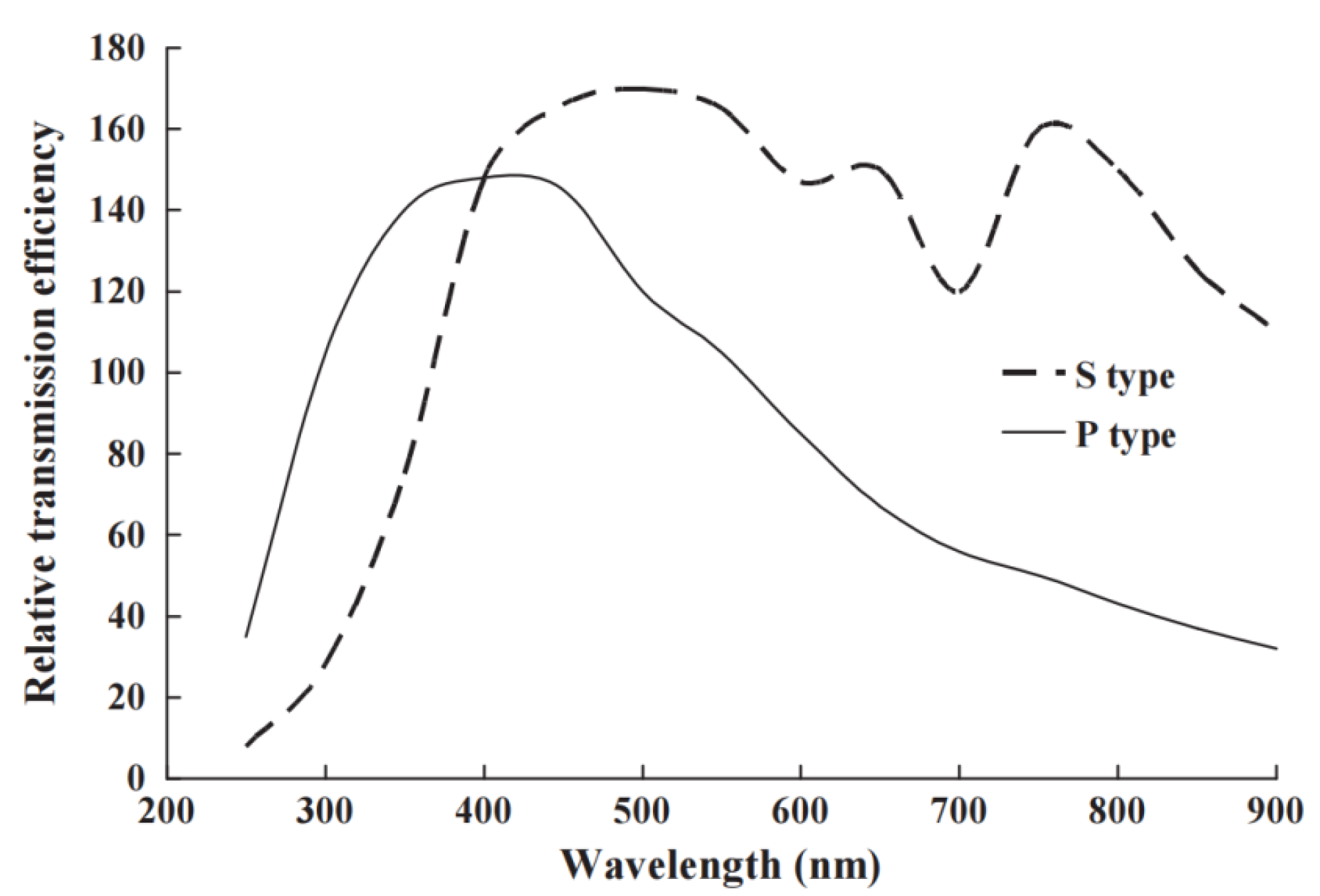

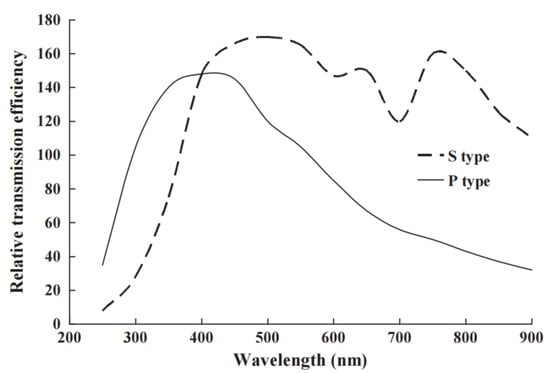

A note of caution is that a spectrometer feature that is rarely considered is that if the light comes from a crystalline source with an anisotropic structure, then different emission features will be polarised. This has a major but rarely mentioned consequence on the recorded intensity, since the wavelength sensitivity of a diffraction grating will differ in efficiency, not just with wavelength but also with polarisations of light parallel or perpendicular to the diffraction grating line structure. This is normally a minor error for the grating, but when the entire system is considered, these differences can be significantly compounded. Figure 6 displays an example of particularly bad system. This warning applies equally to both photomultipliers and charge-coupled detectors (CCDs), as there will always be polarisation sensitivity of the diffraction gratings and order overlap of the spectra. Failure to recognise these when recording signals introduces many false features into the spectra. Line spectra examples are clearly obvious in many articles.

Figure 6.

An unusually divergent example of diffraction grating and system efficiency differences for light polarised parallel (P) and perpendicular (S) to the grating lines [48].

3.5. Detector Spectral Response

Knowledge of the wavelength sensitivity of a photomultiplier (or CCD) is required for intensity analysis, but catalogue values are generic and can differ noticeably between nominally identical components, and they also change with ageing. Commercial photomultiplier tube (PM) calibrations are invariably performed across UV to red wavelengths, but a photocathode that has been recently exposed to UV can temporarily have higher red sensitivity. It is also often assumed that commercial spectrometer systems provide wavelength-corrected intensity data, but this is not universal. Therefore, calibration with a black-body spectrum is essential, especially if the detector is changed or aged. This level of finesse is rarely needed for routine dosimetry but is required for spectral analysis and site modelling.

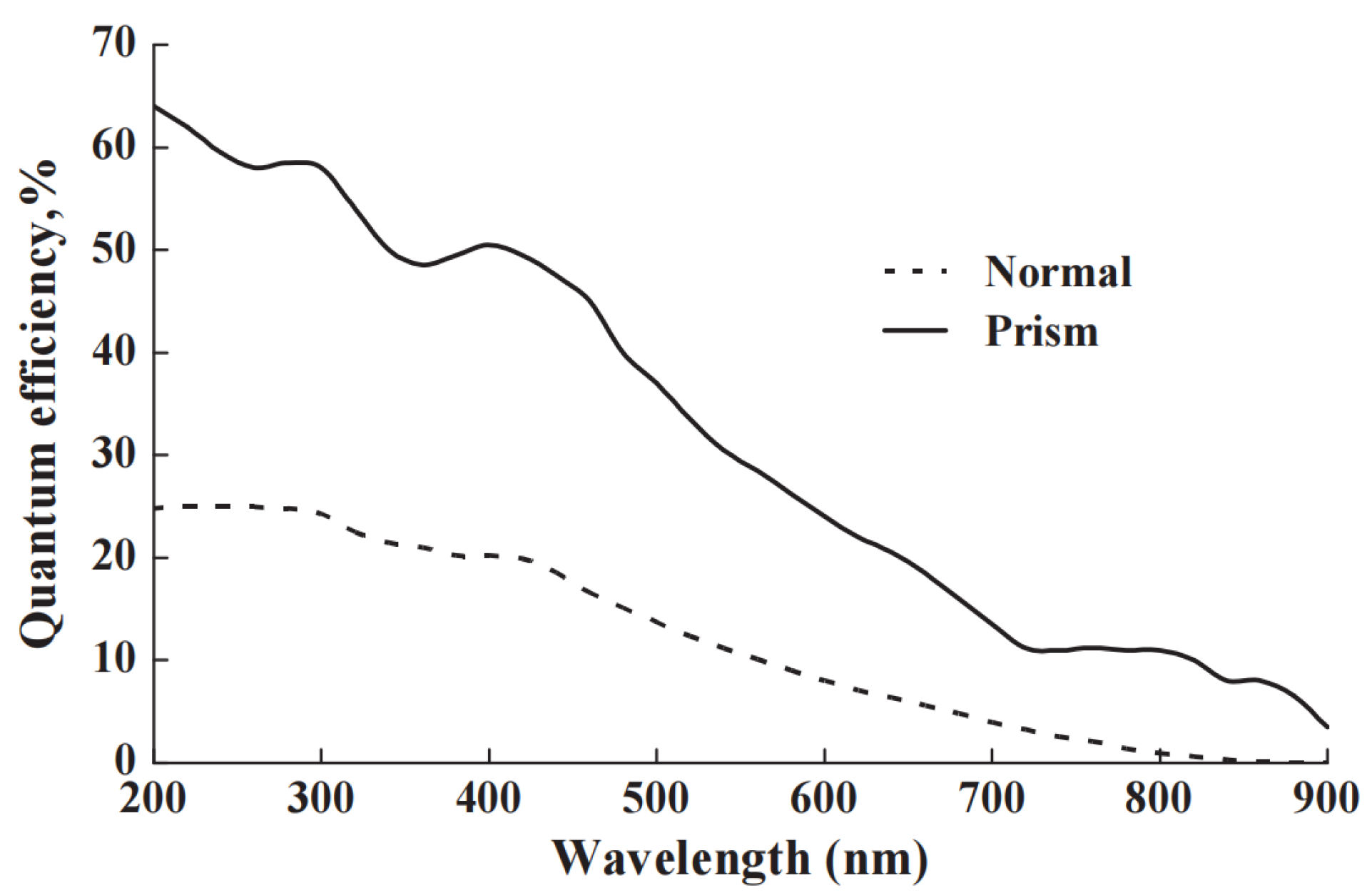

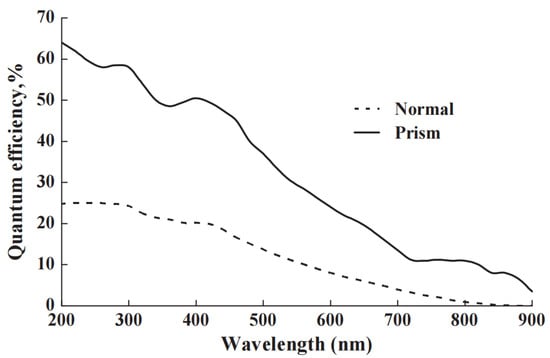

Rather than merely directing the light at normal incidence onto the detector, there are numerous ways to gain higher intensity signals. A high percentage of light on the PM tube is backscattered. Furthermore, the quantum efficiency is low for a planar photocathode illuminated at normal incidence. By adding a simple reflector dome (with the initial beam entering at the centre), the reflected and scattered signals return at different angles of incidence, which correspond to higher detector efficiencies. In one example, with a 1 EURO torch reflector, we increased signals by 20% [45]. Far greater enhancements are feasible if the signal is being delivered by an optical fibre, as a prism coupler can then generate waveguiding of the light across the photocathode, and very high signal enhancement occurs [44,45,46]. The data in Figure 7, in terms of PM tube quantum efficiency, show improvements of about 3-fold at short wavelengths, but over 10-fold at the red end of the spectrum.

Figure 7.

The data show how moving from conventional head-on illumination to coupling and waveguiding across the photomultiplier faceplate enhances the performance of the photocathode (using the same photomultiplier tube). The percentage improvement at long wavelengths is exceptional [46].

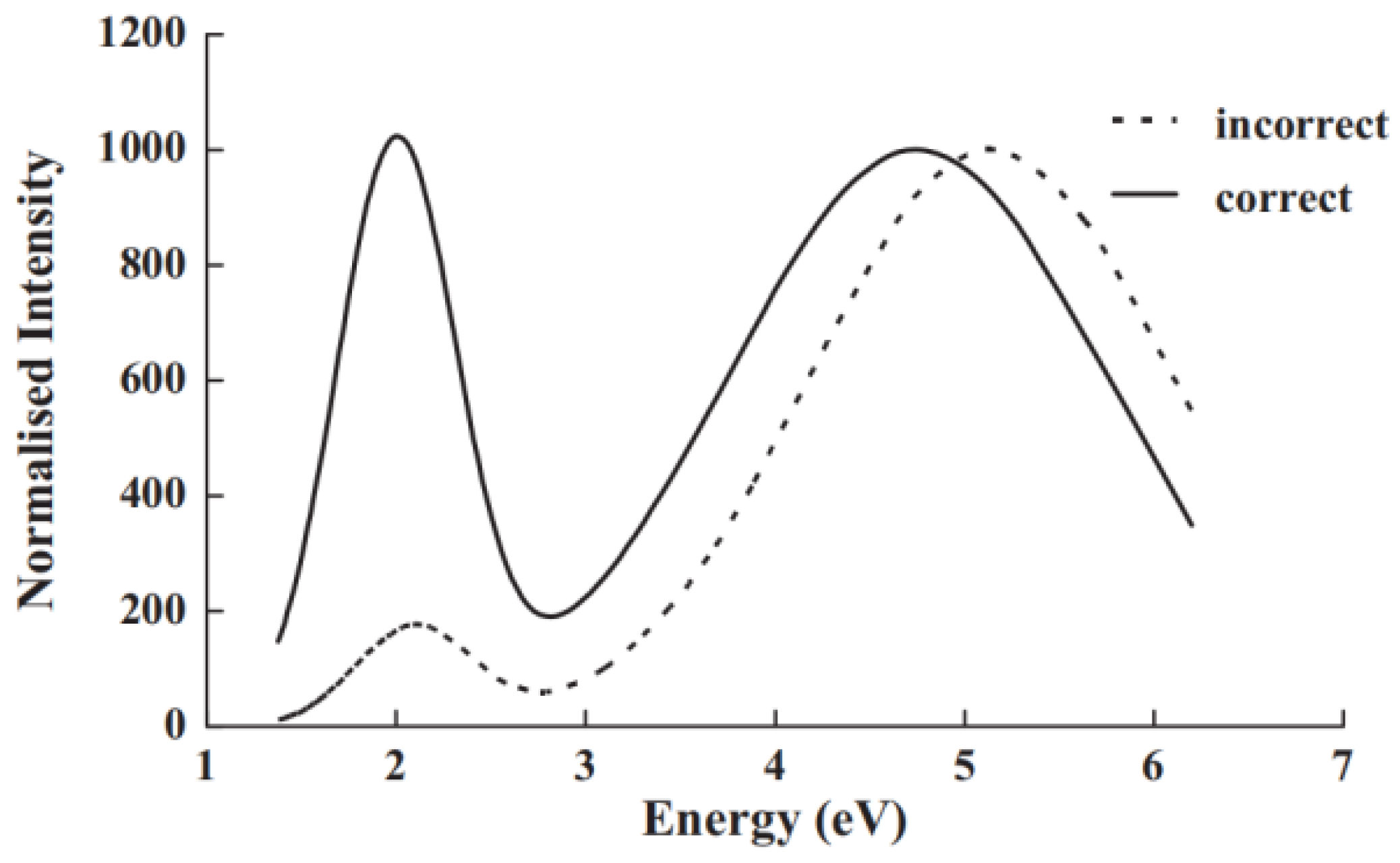

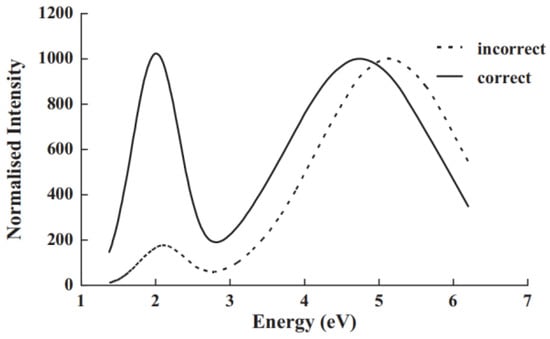

There is additionally a perception problem that, when one views the original spectrometer wavelength data, the longer wavelength bands occupy more of the space on the wavelength axis, leading to the assumption that this is the key spectral signal, even though there may appear to be stronger signals over a smaller wavelength range at shorter wavelengths. This distortion bias will perhaps be more obvious with a photomultiplier, rather than CCD recording. To emphasise this perceptual misreading, Figure 8 displays the wavelength plot of a red and a UV band taken with a red-sensitive PM tube with an S20 photocathode. A completely different perspective appears after data are transformed into a photon energy plot, where it is apparent that both bands actually have the same intensity, and in energy terms, the UV band is much broader. Since the relevant science is based on energy, not wavelength, this further emphasises why conversion from wavelength recordings to energy terms is essential [48].

Figure 8.

This figure emphasises that conversion from a spectral wavelength display to a corrected energy presentation completely changes the perception of which features are dominant. The red end is at the left side of the diagram. In the original wavelength data, a broad weak red feature and more intense UV emission appear. When transformed into an energy plot, both bands have the same maximum value, and the UV band remains strong over a wider spectral range [48].

4. Defect Information Derived from TL Measurements

4.1. Information from Glow Curves

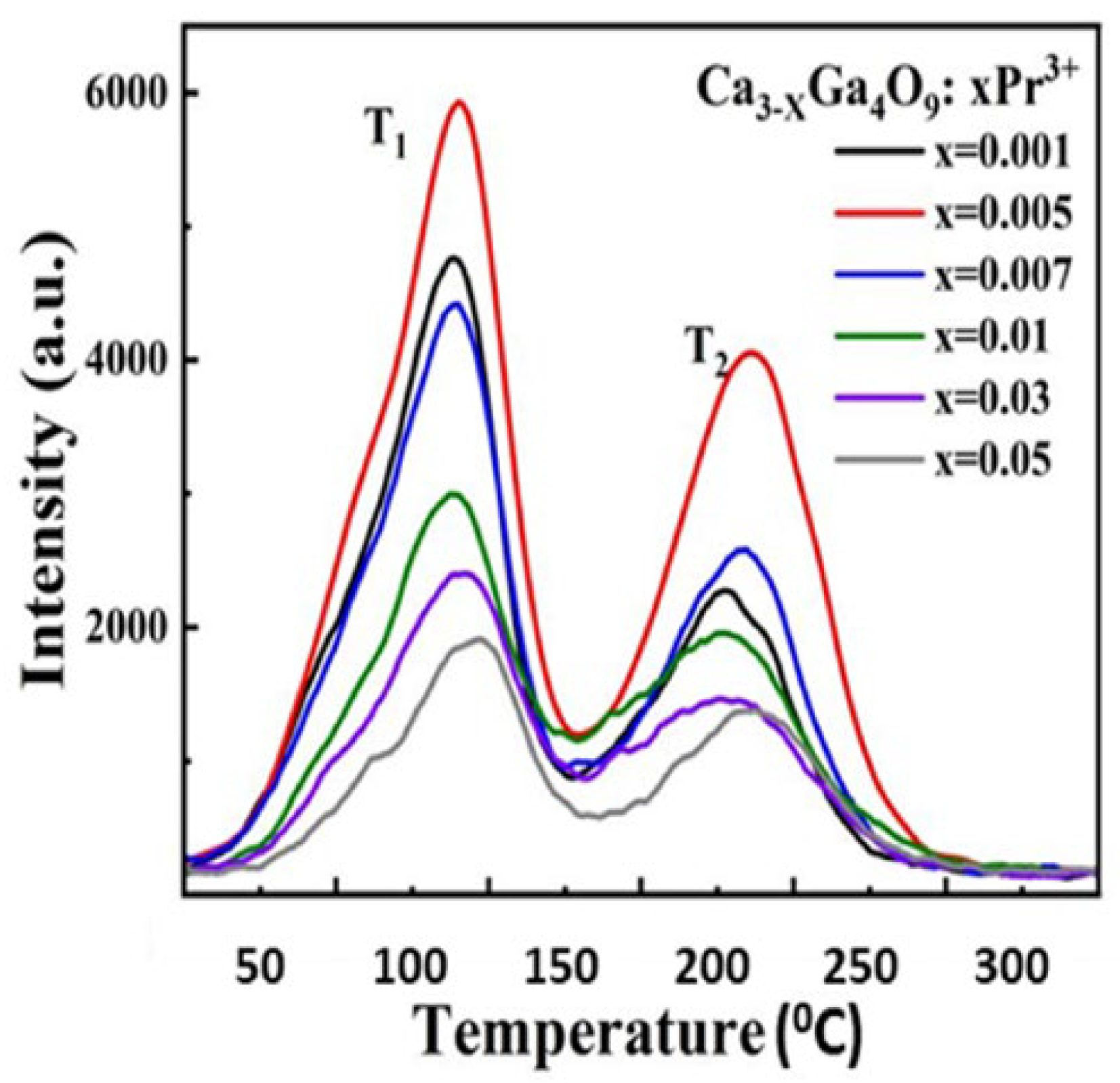

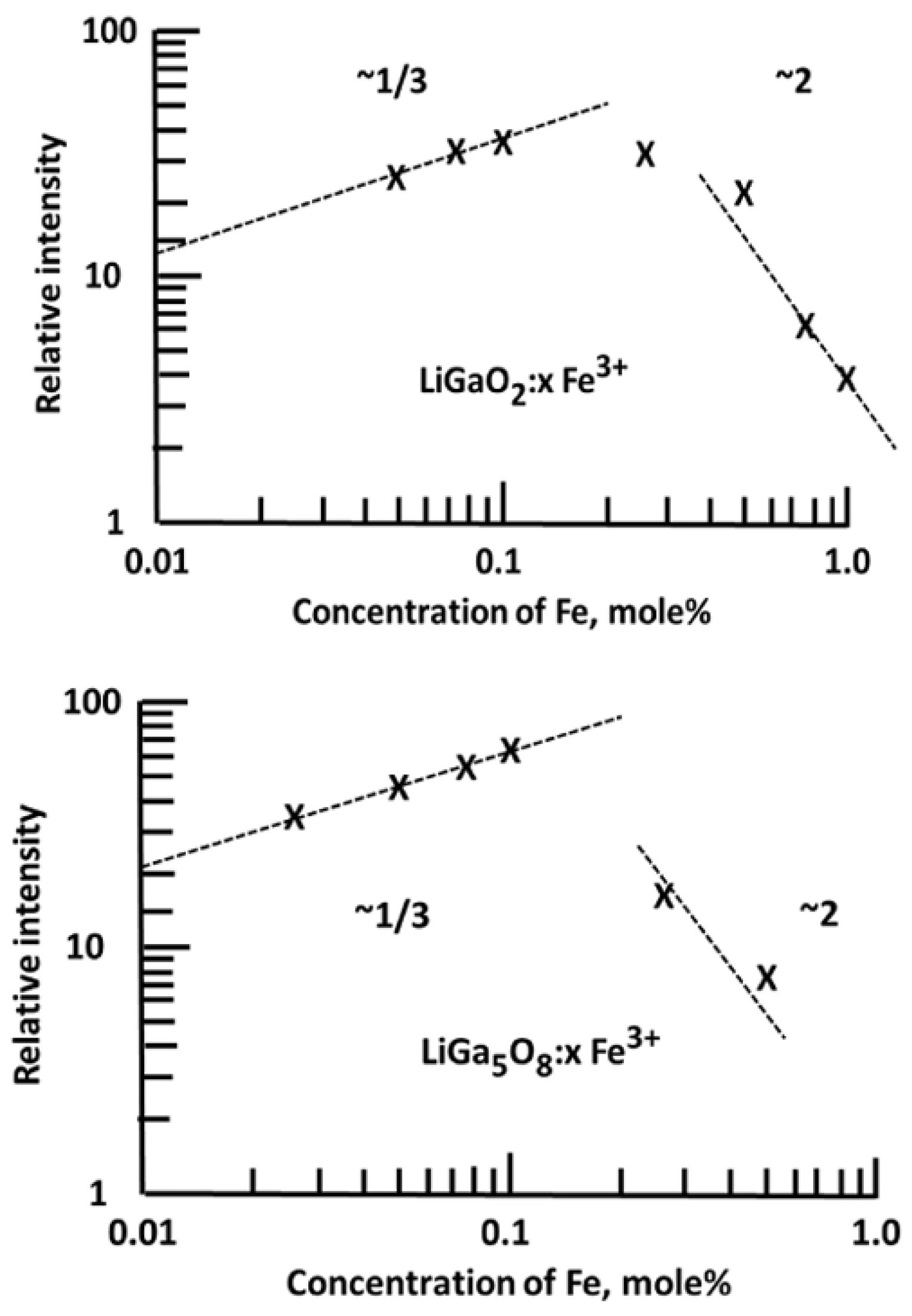

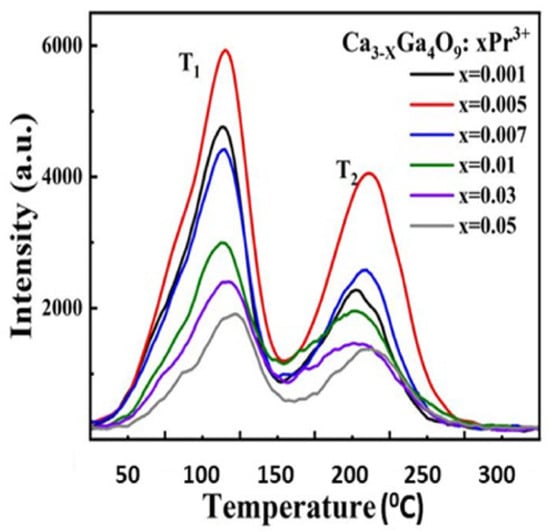

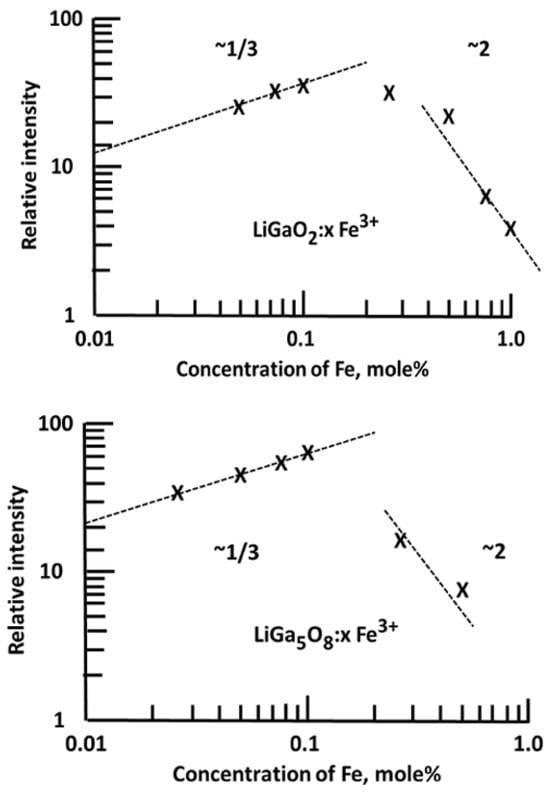

A standard thermoluminescence article will typically mention an application that can be addressed by TL, cite related literature, indicate why the new material may be more useful, and then present the results. This may include real progress, and it indicates the potential of the material. Since many such examples require additives (dopants), the study may include analyses of concentration effects and X-ray crystallography, which indicate how the structure is modified as a function of the dopant concentration. In many examples, the intensity is linearly related to the concentration, and the form of the glow curve is identical (this implies that isolated dopants do not significantly interact with or distort the host structure). Alternatively, the dose dependence may also emphasise changes in spectra and peak temperatures and may include information to estimate how TL peak intensities change with concentration (e.g., Figure 9 and Figure 10). A log–log plot of intensity versus concentration with a linear slope implies that the dopants act independently. In contrast, in the examples shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, this is not the case. The initial one-third slope indicates clustering into triplet sites, while at higher concentrations, the performance switches into pair formation, which disrupts the valuable triplets. Very frequently, a detailed view of the X-ray data shows they change noticeably with dopant concentration. To exemplify this type of simple analysis [49], Figure 9 offers TL examples of calcium gallate doped with different concentrations of Pr. In this simple plot, two regions for TL peaks appear near 110 and 210 °C (but with peak temperatures modified by concentration). A logarithmic intensity plot versus Pr concentration indicates that higher concentrations progressively reduce the TL signals and move the peak positions. Along the same line, Figure 10 displays concentration changes introduced by Fe-doped gallates. In both cases, there is an initial signal increase with a slope of one-third (i.e., the dopants form triplet-linked clusters), but above ~0.1 mol%, this switches to pair formation, and the signal is progressively reduced. This informative use of TL data reveals details of major structural changes at the luminescence sites. Most importantly, it emphasises that the dopants are not isolated ions within the lattices; in this example, they exist either as pairs or triplet clusters. As will be further discussed, this opens the possibility of increasing performance.

Figure 9.

Dopant dependence of the TL signal intensity and peak temperatures for 2 peaks of Pr doped calcium gallate [49].

Figure 10.

TL intensity plots of Fe-doped Li gallates, emphasising initial triplet site formation but signal loss at higher concentrations due to conversion into dopant pairs [49].

Most articles attempt to offer models for the sites, cross-reference the literature, and discuss similarities with the new material. Whilst this is the standard pattern, it is highly speculative. The fact that the X-ray data are visually different means there are immense lattice distortions, indicating that “point” defect models are far too idealistic. Furthermore, intensity dependences, as exemplified here in Figure 9 and Figure 10, unequivocally show that dopants can enter in close enough proximity to enhance, or quench, the source of the luminescence. The broad band spectral data do not immediately identify the structure in these examples, whereas with dopants such as rare-earth ions, there is absolute certainty from the emission line spectra that luminescence corresponds to rare-earth transitions. Detailed luminescence studies of rare-earth ions in LaF3 reveal that not only dopants enter La sites (as expected) but so do associated triplets. With double doping, both single-dopant triplets and combinations of the two can form. The ionic size of the triplets defines the TL peak temperature and also reveals two regions of different ionicity (with co-ordination numbers of six for smaller ions and eight for the larger ion sites). Equally, pairs and clusters of dopants of different elements are well documented (e.g., it has historically been recognised that in ruby, the chromium dopants are paired in the Al2O3 lattice). In many TL examples, the TL peak temperature appears to depend on the dopant package size. Standard TL site models may recognise such possibilities, but rarely are there data that can unequivocally confirm these situations or the development of precipitate dopant structural phases.

4.2. Controlling the Size of Clusters

Figure 10 emphasises that adding more dopants could initially improve signal intensity, but an excess could cluster differently and transform into non-useful groupings. Therefore, stronger signals could be achieved if the high concentration of pairs could reform into triplet clusters. Simple thermal annealing could break up all the clusters, so a furnace cooling cycle might dissociate them, followed by a secondary treatment to regroup the iron with the preferable triplet association. In this example, the maximum dopant level would then potentially increase the TL signal by almost 10 times. However, different stages of rapid and slow cooling might be required to optimise triplet association. Nevertheless, the scale of such improvements would justify these efforts. This is a very general problem with high levels of dopants and could have wide relevance.

Commercial examples have shown that control of metal colloids can modify the optical properties, such as absorption and transitions, of glass products [50], and this is also observed in rare-earth-doped laser systems [51,52,53]. In examples with ion-implanted Er, there was inevitably ion beam radiation damage, which was removed either by furnace or intense laser pulse heating. Furnace annealing is slow, so the Er presumably clustered, whereas the pulse lasers dissolved clusters, and very rapid cooling preserved their isolation. In terms of both laser performance (and cathodoluminescence), the furnace increased intensities by 10 to 20 times, whereas the pulsed lasers approach increased them by 80 to 100 times (i.e., removing rare earth pairs and clusters). A further, but less obvious, advantage of laser treatments is that they are independent of the sample temperature, and when made at lower temperatures (e.g., room or below), cluster reformation may be inhibited. It would be equally interesting to see if such laser treatments can remove the crystallographic distortions that are commonly reported in the TL literature for doped host systems.

4.3. Crystallographic Data and Modified Luminescence Responses

Most TL models and descriptions of dopant effects seem to imply that the host structure and crystallography are unchanged by the addition of dopants. Certainly, at the parts-per-million level, this may be possible (e.g., if the dopants are perfectly separated by ~100 lattice sites in a cube). However, this implies that the dopants are uniformly distributed. Considerable evidence shows that they may cluster in pairs (e.g., Cr pairs in ruby, observed in the 1950s), in triplets (e.g., as seen in the TL of RE dopants in LaF3 in the 1990s), as subphase particulates (e.g., CO2 and water in many TL examples showing their phase transitions), in long-range ordered strings (possibly along dislocations and grain surfaces), or in entirely new and unexpected structural arrangements and/or new phases. In virtually all the published X-ray data, the patterns visually change with dopant concentration at extremely low dopant concentrations. Unfortunately, even at the lowest concentrations, we can never be certain that the distributions of dopants are uniform and isolated. This introduces an intrinsic major deficiency in modelling their role in sensitive properties such as luminescence.

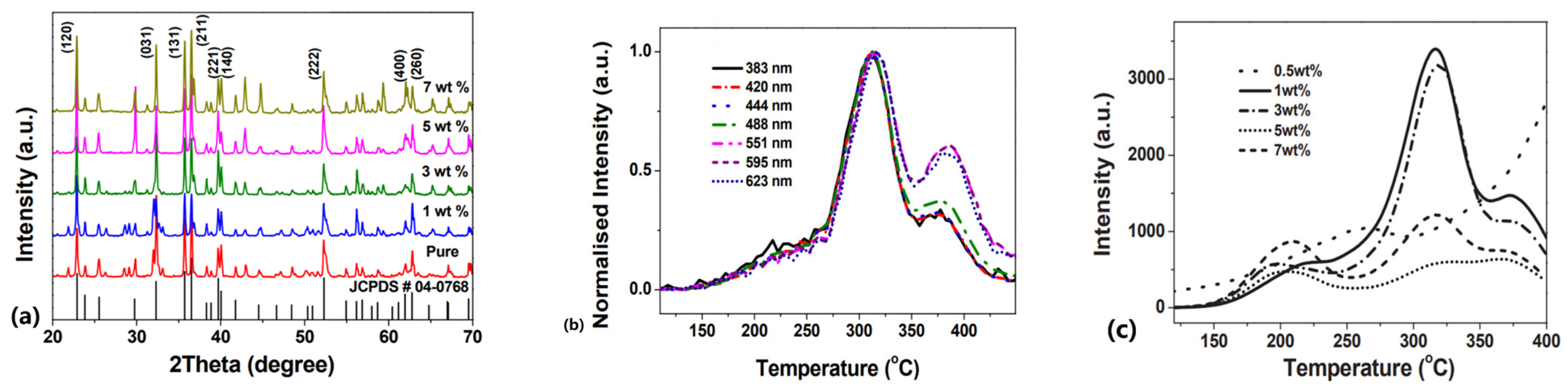

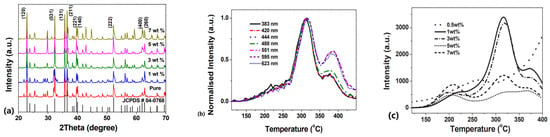

Figure 11a presents an XRD example of relatively heavily doped Mg2SiO4: Tb3+. This was chosen as it shows only minor distortions for quite high Tb dopant concentrations (i.e., it is a remarkably stable system). There is, however, a slight expansion of the cubic lattice. Tb has several emission lines, and for the seven shown in Figure 11b (normalised peak intensity), there are both peak shifts in temperature and obvious differences in the relative magnitude of the two TL peak regions. Polychromatic TL curves (Figure 11c) are far more complex to interpret, as they imply a very varied range of Tb-related sites that are concentration-dependent (e.g., as previously noted from the gallate examples). Overall, XRD indicates a slight expansion of the lattice (as expected).

Figure 11.

(a) Concentration-dependent XRD patterns, (b) normalised wavelength-resolved TL glow curves, and (c) integrated polychromatic TL as a function of Tb doping level in Mg2SiO4: Tb [54].

The unavoidable conclusions are that adding the dopants (a) increases the structural size of the fundamental unit cell; (b) causes TL transitions that involve a range of electron-hole coupling processes, which are strongly dependent on the local wavefunctions of the different Tb energy levels (i.e., the charge movement is not from some distant trap via the conduction band to isolated Tb sites); and (c) requires the sites to be interlinked in sufficiently close proximity together, with long-range interactions, so that the TL responses vary significantly as a function of concentration. Unfortunately, this clearly implies that the idealised simplicity of the TL model in Figure 1 is both completely inadequate and misleading, as it fails in every one of these aspects. The real challenge is to include the complexity of charge coupling to neighbours and specifically to different energy levels via adjacent and long-range wave functions, potentially including the phenomenon of tunnelling.

In reality, a mixture of isolated, pairs, triplets, and/or precipitate phases may all coexist, with different lattice distortions and short- and long-range interactions. A further complexity, even with the rare-earth sites, is that the size of dopants and the sizeof host lattice sites may involve different electronic structural co-ordination numbers. Therefore, small and large dopants may respond differently, even though they are chemically of the same subset (e.g., as clearly noted for rare-earth ions in LaF3).

Once one recognises the presence and magnitude of structural changes and long-range interactions, these critical comments are justified. TL is sensitive, showing distinct variations in signals when measuring the TL from the same sample in crystalline form, after it has been crushed, or when transitioning from small crystals to powder (a very typical dosimetry format). Not only do the signals change at each stage, but there are literature examples of surface and dislocation contaminants that add yet more confusion.

Strong trap and luminescence site coupling can offer a route to an efficient TL dosimeter or sensor. The nearness of sites may involve a small structural package and more than one dopant. Historically, the LiF dosimeter TLD 100 was a good, albeit complex example, as it involves Mg dopants, Li vacancies, oxygen, and titanium all linked together. Despite the many components, the trap and recombination sites appear to be very efficiently united.

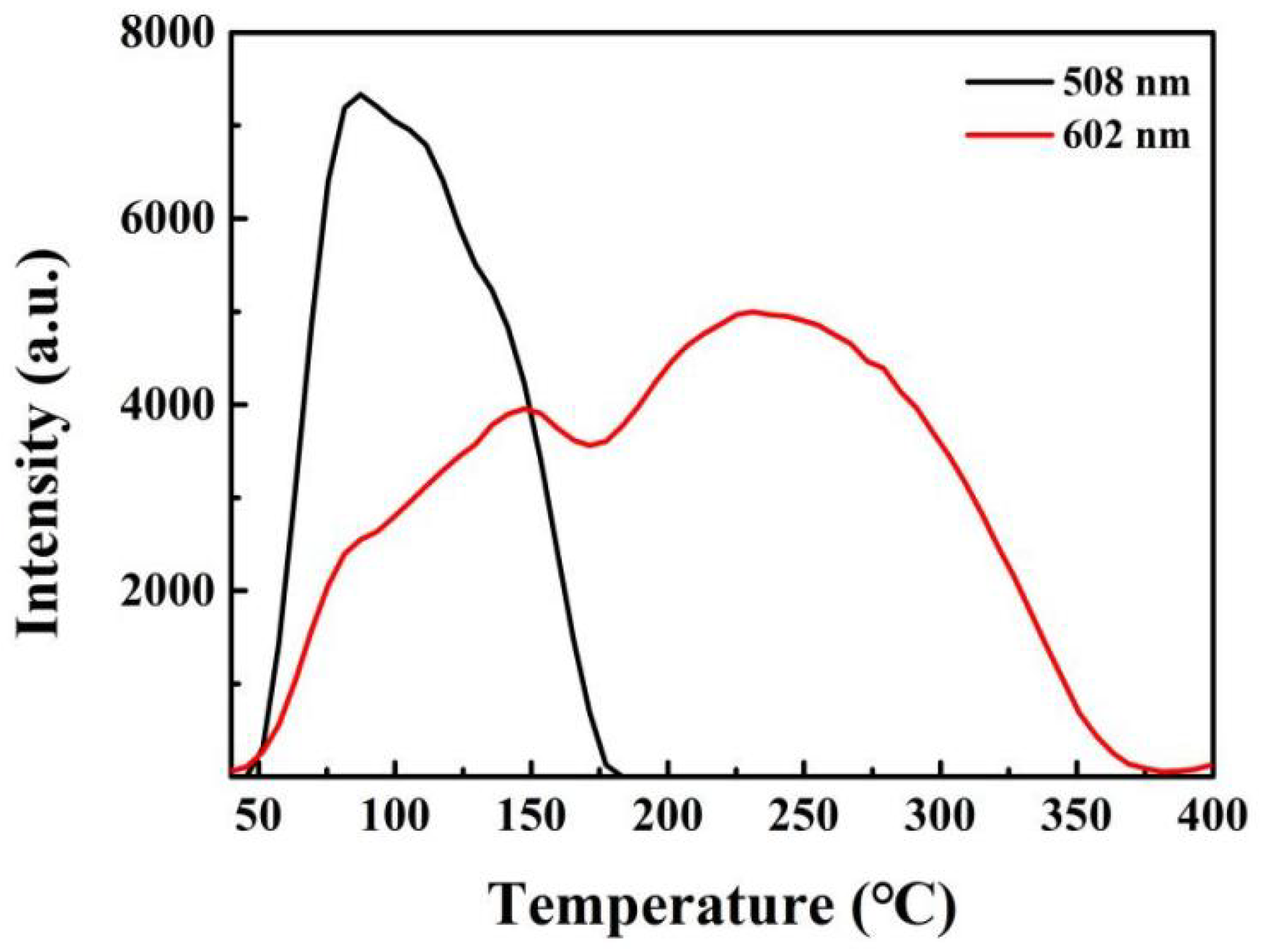

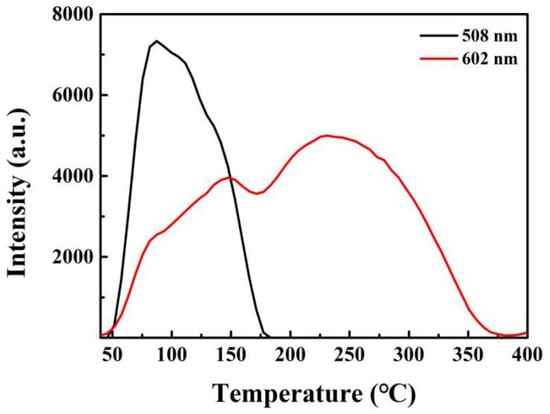

4.4. Transition-Sensitive TL

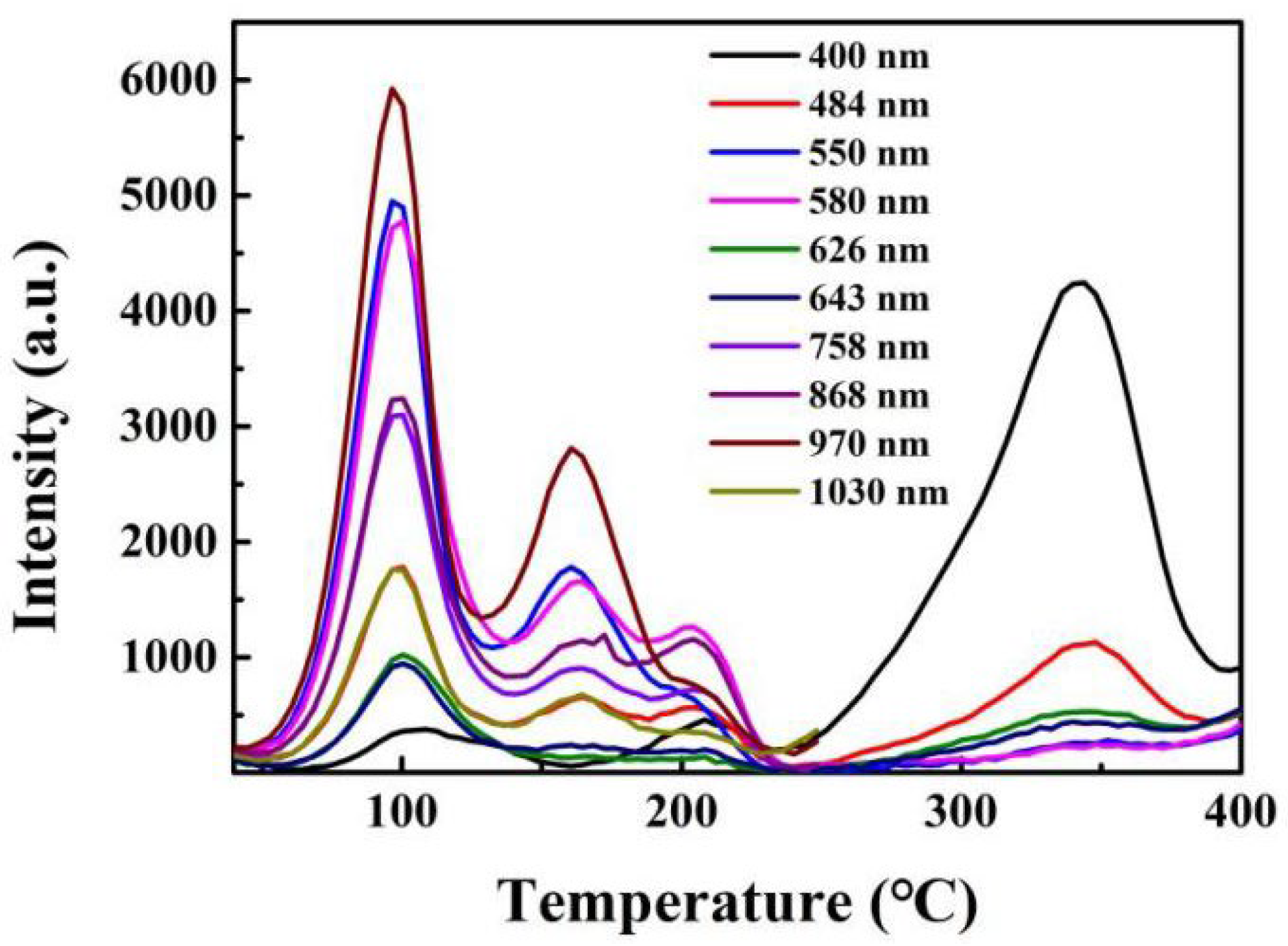

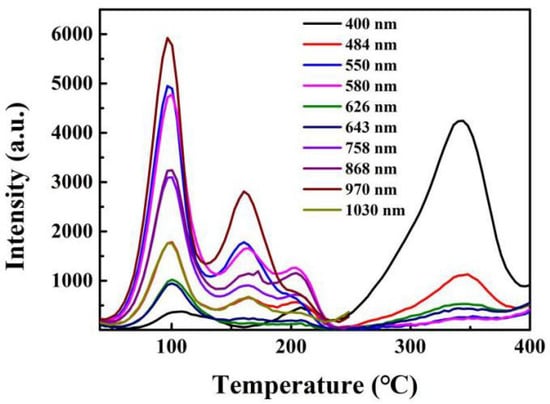

A further aspect of very close linkage between trap and luminescence sites is that rather than charge being transferred via the conduction band (e.g., at high temperatures), there can be far lower barriers locally and/or there may be tunnelling. Hence, when charge moves to a rare-earth luminescence site with discrete transitions, the initial signals produce spectra that differ from those generated when electrons return by barrier crossing to the highest levels. Extremely clear demonstrations of this exist in the case of rare-earth ion luminescence sites, where only lower-level tunnelling transitions are seen at very low temperatures, and their TL peaks also differ in temperature. By contrast, the entire set of TL transitions may occur at higher temperatures, and their peak values are invariably closer. However, their TL temperature widths can be very wavelength-dependent, implying major differences from their orbital forms [55,56]. Such data are clearly apparent in many examples of rare- earth transitions in different hosts, especially at very low temperatures. If all charge transfers occurred via the conduction band, then RE site emission would generate identical TL signals. However, this is rarely the case, and most spectrally resolved RE TL show that the peak temperatures and relative intensities are significantly different for each transition. The transition-sensitive differences in terms of the intensity patterns tend to be more pronounced on the lower-temperature sides of the wavelength-resolved glow curves, implying that there is a tunnelling aspect of many transitions. Figure 12 presents examples for Ca2.90Ga4O9:5 mol% Bi3+, 5 mol% Na+. The variations in TL temperature response for different transitions require more spectral precision than is used in dosimetry, but for site modelling, it is extremely revealing in terms of the coupling between trap and emission site, as well as the influence of separation and interactions, even over very long distances.

Figure 12.

TL glow curves of Ca2.90Ga4O9:5 mol% Bi3+, 5 mol% Na+. The site models for the two bands are speculative.

A spectacular example of TL changes due to wavefunctions coupling to different states is provided by data from Nd-doped CaF2 [55,56]. The TL emission spectra have a wealth of Nd transitions, and even at low resolution, there are at least three major glow peaks cited. However, as seen in Figure 13, the form of the TL pattern in terms of relative intensity and peak temperature is dramatically different for every Nd transition. More details are provided in Table 1, including the scale of such differences. Even more interestingly, these variations in both glow curves and intensity for each transition change further depending on the form: the crystal, the same crystal when crushed, and with further changes in the powdered version. One might assume this is an example of a mixture of tunnelling and/or long-range wave function coupling. In contrast, in a conventional TL model of isolated defect sites, all three would have been identical and insensitive to long-range interactions. Such experimental evidence introduces a challenge for theoretical modelling, as it clearly does not merely involve a charge transfer via a single, fixed energy barrier.

Figure 13.

TL spectra of a crystal sample of a CaF2:Nd sample [56].

Table 1.

Normalised data of 10 of the TL peaks and their relative intensities for a crystal of CaF2:Nd before and after crushing. This emphasises that every transition is influenced differently by a large number of interactions with nearby ions. The fact that there are differences between a crystal and the same sample after crushing implies extremely long-range interactions. Further changes exist with powder formation, as these include surfaces and surface contaminants.

To offer slightly more insight into the data in Figure 13, the following table compares normalised intensity data for each wavelength, their measured peak temperatures in a crystalline sample, and the performance after crushing it. The detailed differences highlight shifts in each feature and completely diminish the concept of a single type of dopant/lattice interaction for TL but emphasise that every excited state level has different wavefunctions, which are highly specific in how they interact with many of the neighbouring atoms.

As a final comment on long-range interactions, there has been superb experimental demonstration of much longer-range electron–hole coupling extending over ~60 neighbouring distances of Mg in GaP [57,58]. The spectral resolution required working temperatures near 1.6 K. Whilst the wavefunction interactions remain equally long-range above room temperature, they cannot be resolved, and therefore, are never considered. Nevertheless, they provide a significant contribution to the total signal. Simplistic localised models may therefore be rejecting more than 90% of the actual charge-transfer processes, which have blurred into a continuum, causing us to overlook the possibility of such long-range interactions. They are still a component in the mechanism of thermoluminescence, and hence, every conventional modelling of TL processes based on isolated point defects is significantly flawed.

4.5. Additional Uses of Spectroscopy

In addition to the equipment improvements already mentioned, one could use spectral emission lines to considerably improve the temperature measurements (and hence the energies involved). In particular, temperature measurements could be inferred from changes in the transition rates of rare-earth ions, which might offer a more accurate and quantitative analysis of the energies.

This method is directly compatible with TL, and it would be feasible to combine it with a TL measurement for calibration purposes. It is known as Boltzmann thermometry [59,60]. This would provide a “true” temperature reference scale that could be applied to standard TL data. Since current errors can often exceed 30 to 50 degrees, the corrected data would then be available for comparison with the powerful methods of CL, EPR, ENDOR, optical absorption, RAMAN spectroscopy, and precise X-ray structural analyses. This would offer reliable evidence to assess not just the typical, highly localised site models but also longer-range interactions, and the presence of localised precipitate structures. Many studies also indicate how varied the sites are for the same dopant, with this diversity depending on concentration and/or association with other dopants and impurities. Precision in TL temperatures is essential if cross-method comparisons are exploited and if accurate quantitative analysis to extract energies is to be performed.

One possible route is to use Boltzmann thermometry on an insulator doped with rare-earth ions and excited with a UV laser beam at a wavelength that is blocked in the spectral data collection [59,60] The intensity ratios of the various emission lines are strongly temperature-sensitive, and hence one can accurately monitor the sample temperature from their relative intensities. This will be less than the heater plate temperature. Publications to date give examples from about 300 to 900 K (~room temperature to 600 °C). Simple initial experiments could compare thermometry with TL or use two types of samples on the same heater system. The improvements in temperature accuracy may unfortunately invalidate the numbers discussed in virtually all of the previous high-temperature dosimetry literature. Low-temperature data have invariably been collected at very low heating rates. As already mentioned, TL peak temperatures and wavelength temperatures have already been noted to differ in many examples for each possible transition, so this is not an unexpected outcome. Although rarely used in normal dosimetry, some research groups have explored TL with low heating rates and in every case, have revealed a wealth of more subtle interactions [61,62,63,64].

5. Caveats

Before proceeding to the models and mathematical analysis of TL data to extract energy and frequency factors, it is useful to summarise the key features that need to be included and which were never considered in the earlier models based on the simplistic process sketched in Figure 1. The reality is that the defect sites are not in a perfect host lattice, but one which is distorted. Whilst trapping and recombination sites might be well connected via charge transport through the conduction band, Figure 1 does not readily account for the multiplicity of trap and recombination centre types, all of which may interact (exchange charge). Furthermore, the model assumes spatial dissociated traps and centres and does not apply to situations where the trap and recombination sites are in close proximity. Therefore, this initial model is inadequate whenever trap and recombination sites are closely linked either by a localised distortion or a doped package. It should be noted that the interaction regions may be extensive. References [57,58] showed that at low temperatures, electron/hole exciton coupling could be resolved, not merely with immediate neighbours but even up to 60 atomic shells away.

TL dosimetry above room temperature lacks the spectral resolution to detect these component emission features, but a large interaction volume is still a relevant factor and must be considered. Furthermore, with a multiplicity of orbital states, the range of strong coupling between the TL site and its neighbours can be very variable. Indeed, in many cases, the initial glow peaks may involve tunnelling rather than barrier crossing. As noted above, this has been apparent with rare-earth ions where the spectral composition changes with temperature. This multiplicity of interactions is evident, even at high temperatures. The examples above room temperature showed that the TL data of CaF2:Nd displayed quite different wavelength-dependent glow curves (both in shape and peak temperature) for each transition. Even more important is that these are all significantly modified when crushing a single crystal into powder [56]. This unequivocally implies that extremely long-range interactions are involved. In the models from the 1960s, such possibilities were not included, and hence, simplistic kinetic modelling of TL was understandable, but flawed.

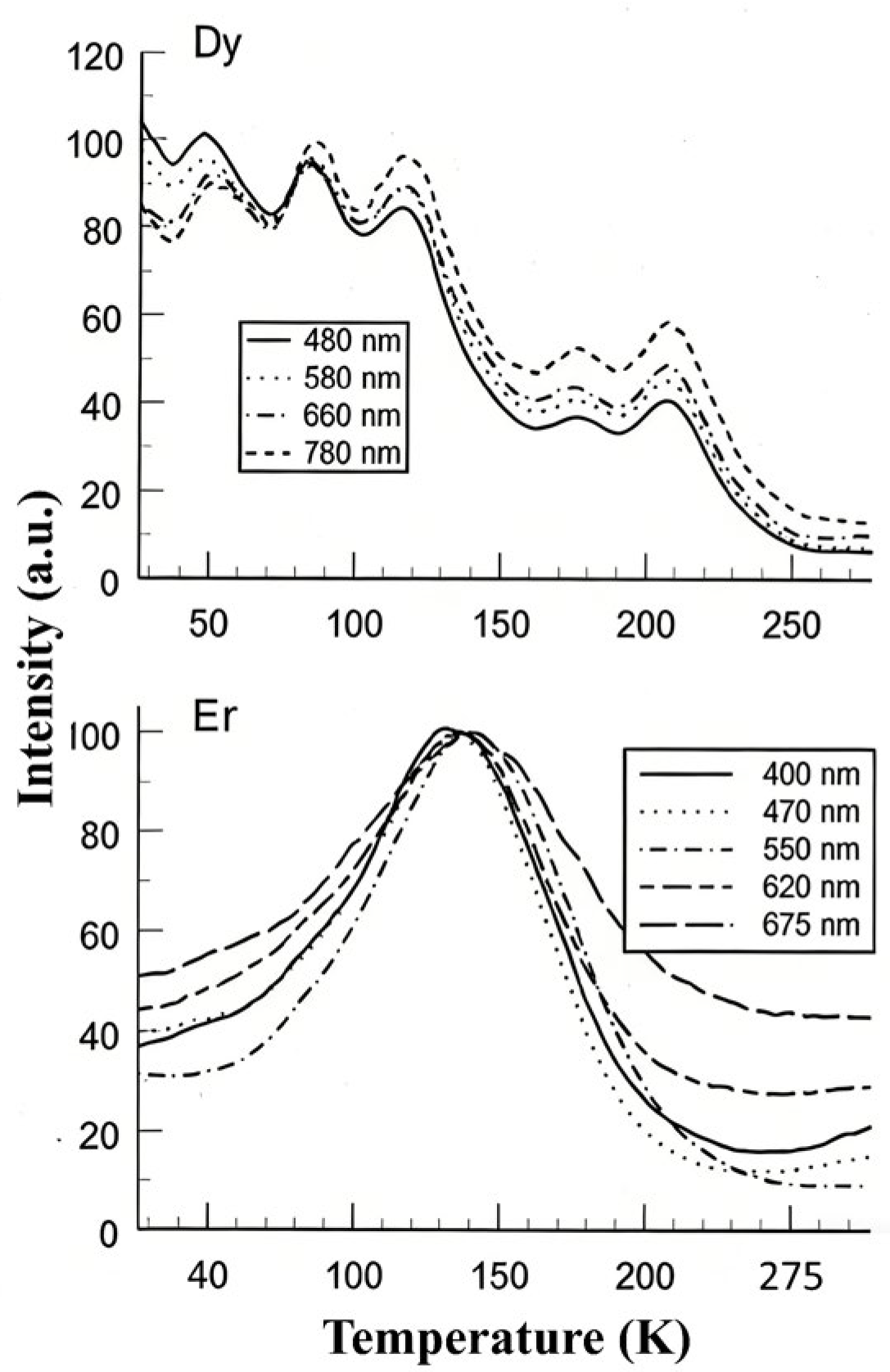

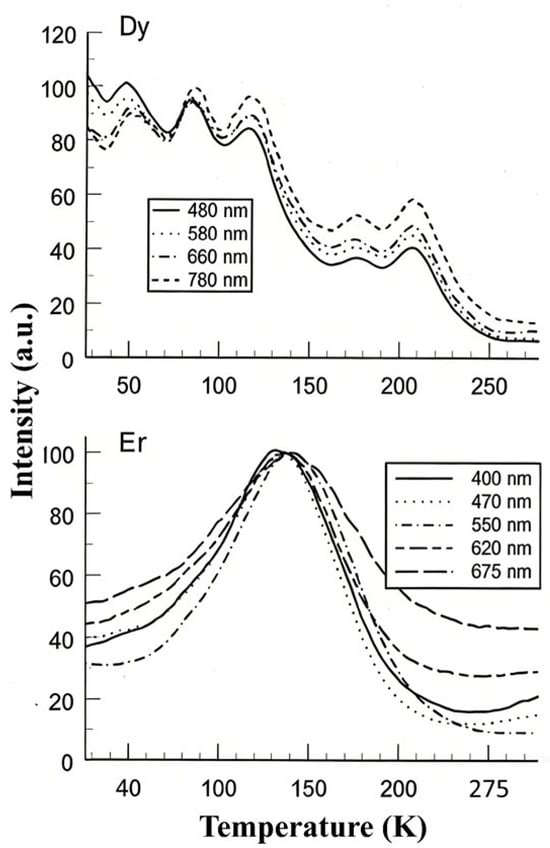

Low-temperature spectral analysis of TL that includes rare-earth ions clearly shows (a) the peak temperatures vary with wavelength, (b) the pattern of intensity with temperature (i.e., glow curve shape) is different for each transition, and (c) hence, the relative intensities of wavelengths are also variable with temperature. Since the literature on low-temperature TL may be unfamiliar to those working in dosimetry, Figure 14 presents typical examples of these features. The data were obtained at a low heating rate of 6 K/min following X-ray irradiation at 20 K.

Figure 14.

Low-temperature TL data of rare-earth-doped zircon crystals at a heating rate 6 K/min.

In Dy-doped zircon, there were five low-temperature peaks. The pattern of relative intensities reversed over this temperature range, the peak temperatures differed, and for the lowest temperature peak near 50 K, they differed by up to 10 percent in energy. The Er example is typical of such measurements where the transition intensity pattern of the various transitions is completely different, and normalised data differ both in peak value and in shape. Here, the relative intensity ratios vary by up to ~300%. Such differences in spectral behaviour are normally hidden above room temperature, although orbital dependence of the TL will still exist. In the following sections, these issues are discussed with respect to the quantitative analysis of glow curves. It is shown that analysis based on isolated traps and centres that do not interact will lead to erroneous results, and that localised recombination, including tunnelling, must be included in numerical glow-curve analysis.

Although rarely considered, data collected at a very low heating rate have clearly shown a range of additional features and experimental distortions that are missed in fast heating, as used in dosimetry. Some examples of such data and confusions caused by different thermal stability of components have been previously discussed [61,62,63,64].

6. Analytical Issues and Model Inadequacies

6.1. Delocalised Transitions

Despite the weight of experimental evidence, as summarised here, to indicate that isolated “point” defects are highly unlikely in radiation dosimetry materials, the literature continues to be full of analyses of TL glow curves that assume exactly that. The simple model in Figure 1a is the model most commonly used to quantitatively examine TL glow-curve shapes. In this model, isolated traps release their trapped charge, and their corresponding wavefunction immediately becomes delocalised, thus allowing recombination to occur at any available isolated recombination site elsewhere in the crystal. Furthermore, by treating each TL peak as isolated, the whole glow curve is assumed to arise from a linear sum of such models, one for each TL peak in the glow curve, with zero interaction between defects, whether traps or recombination sites.

Based on these assumptions, the analyses of Randall and Wilkins [65,66], or Garlick and Gibson [67], or May and Partridge [68] are usually adopted, with the assumption that the analytical expressions can be added using the Superposition Principle. The first analysis of the model in Figure 1a by Randall and Wilkins assumed that once an electron, for example, has been released from its trap, the likelihood of retrapping before recombination occurs is small. With this assumption, and the assumption of quasi-equilibrium, Randall and Wilkins determined that the rate of trap emptying is given as follows:

where n is the trapped electron concentration, Et is the thermal energy required for the release of the electron to the delocalised band, k is Boltzmann’s constant, T is temperature, and t is time. One can see that this is a first-order equation with the dn/dt rate proportional to n. From this, the equation describing a TL peak can be given as follows:

where is a dummy variable representing temperature, and β is the heating rate, equal to dT/dt.

Garlick and Gibson [67] adopted a different assumption wherein the rate of recombination is similar to, or greater than, the rate of retrapping, and they developed the following Equation:

where N is the total available trap concentration, and the expression is now of second-order with dn/dt proportional to n2. From this, the TL peak shape is given as follows:

where all terms are already defined.

May and Partridge [68] generalised Equation (3) and wrote the following empirical expression:

where b is an empirical term representing the order of kinetics and can be neither 1 (first-order kinetics) nor 2 (second-order kinetics). It represents, in an ill-defined manner, the relative strengths of retrapping and recombination. Using Equation (5), May and Partridge developed the so-called “general-order” expression for TL, as follows:

Most analyses of TL glow curves then proceed using a linear sum of general-order expressions, as follows:

where there are i = 1-to-u peaks in the glow curve.

Even assuming, for the moment, that charge is indeed released from every trap into the delocalised band, the use of expression (7) for deconvolution of glow curves is clearly inadequate, since it treats each peak in complete isolation, disallowing trapping of the released electrons into other, deeper traps, and ignoring potential recombinations at multiple recombination sites.

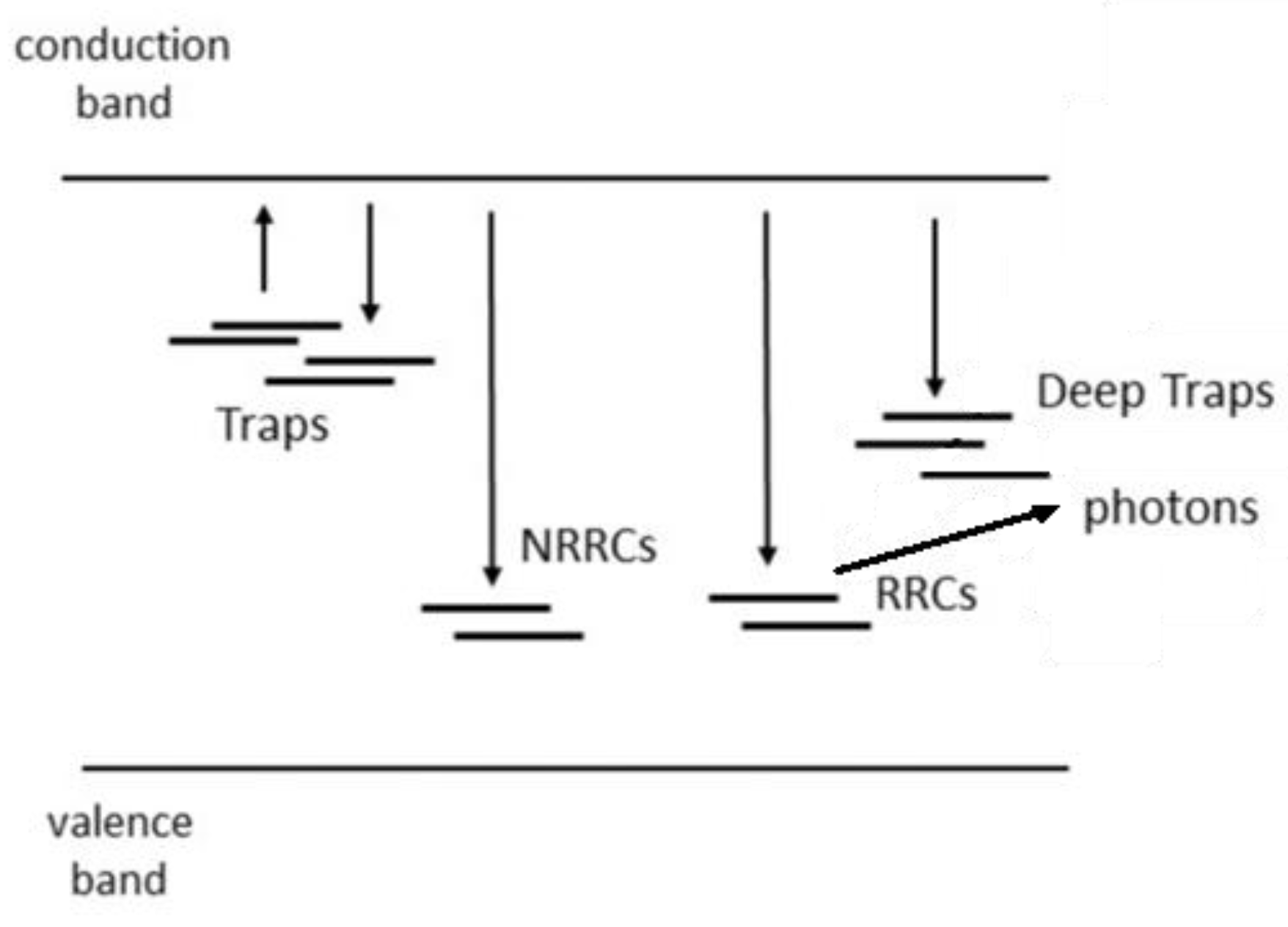

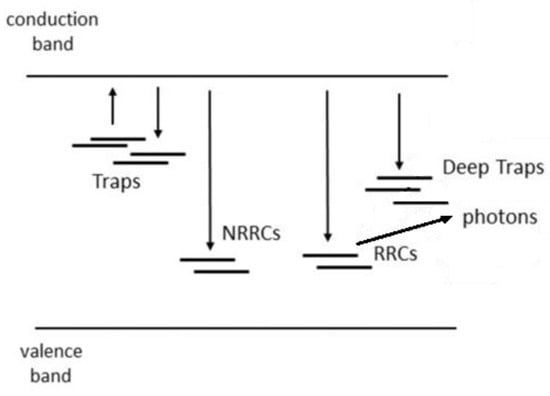

As already pointed out in several treatises, a more realistic model for TL production (ignoring, temporarily, localised recombination within a cluster of traps and recombination centres) is that given in Figure 15. In this model, there are multiple traps present that can interact with any other trap such that electrons released from one trap may be re-trapped in deeper traps. Also assumed is a set of very deep traps from which no electron can escape thermally during a normal TL experiment. There are also multiple recombination centres, some of which are radiative and some non-radiative. All transitions indicated are allowed.

Figure 15.

A more realistic, delocalised model (compared to Figure 1a) for charge trapping, detrapping, and recombination, in which there are multiple traps into which thermally delocalised electrons can become trapped. The model also assumes two types of recombination site—radiative recombination centres (RRCs) and non-radiative recombination centres (NRRCs). There are also deep traps for which the temperature (during a TL experiment) is never high enough to detrap the localised electrons. Once an electron is trapped in these states, it stays trapped. Because of charge equality, this means that there is also a population of trapped holes remaining after the TL is recorded. The model is known as the Interactive Multi-Trap System (IMTS).

With such a model, the use of Equation (7) is no longer allowed, since this expression assumes isolated trap–recombination centre pairs with transitions between them via the delocalised band. (In effect, it assumes a sum of isolated one-trap/one-recombination-centre models, as shown in Figure 1a). This cannot be true, however, since, once delocalised, an electron is able to be trapped or to recombine anywhere within the lattice, and therefore, the simple Superposition Principle of Equation (7) cannot apply.

Using the IMTS model in Figure 15, and recognising that TL results from the probability (per second) of detrapping multiplied by the probability (per second) of radiative recombination, Chen and Pagonis [10] showed that the TL glow curve can be described as follows:

where the following terms are defined:

- u represents types of traps with available trap concentrations , trapped electron concentrations n1…nu, trapping probabilities , and thermal trap depths and frequency factors and ;

- v represents types of radiative recombination centres (trapped holes), with concentrations m1… mv, and recombination probabilities ;

- x represents types of non-radiative recombination sites (trapped holes), with concentrations …., and recombination probabilities ;

- The term is the net rate of all potential, trap-emptying events; is the net rate of all radiative recombination events (producing TL); is the net rate of all non-radiative recombination events; and is the net rate of all trapping/retrapping events. Clearly, is the net rate of all recombination events, whether radiative or not.

From Equation (8) the TL intensity as a function of temperature, caused by the first trap (i = 1) to empty during thermal stimulation, can then be derived as follows:

in which is the initial trapped charge concentration in the first (i = 1) trap.

The last ratio, in square parentheses, is the probability of radiative recombination of released electrons compared to all possible recombination and trapping/retrapping transitions. It can be simplified using the following definitions:

- 5.

- Rrt1 = the rate of retrapping into the trap = ;

- 6.

- Rr1 = the net rate of recombination at the RRCs = ;

- 7.

- Rnr1 = the net rate of recombination at the NRRCs = ;

- 8.

- Rt1 = the net rate of trapping into all deeper traps = .

Subscript 1 refers to that value of each of the terms when trap 1 is emptying. Therefore, . With these definitions, Equation (9) becomes

In this analysis, there are no prior assumptions regarding retrapping rates or recombination rates. No assumptions are made regarding fast retrapping, slow retrapping, fast recombination, or slow recombination. The primary assumption (apart from the model itself) is that of quasi-equilibrium [10].

Additional insight comes from unifying the approach of Chen and Pagonis [69] with the earlier analysis of Lewandowski and McKeever (1991) [70], who introduced the functions and . The describes the relative rates of retrapping into the same trap compared to the rates of recombination and trapping into deeper traps. For the IMTS model in Figure 15, we can write

The function describes the closeness of the system to quasi-equilibrium, for which condition For the current model, we can write

where Rex is the rate of thermal excitation from the traps, and the R terms are defined as above. (See McKeever [12] for additional discussion of Q(T) and P(T).) Following Lewandowski and McKeever [71], it can be shown that for the ith trap in the IMTS model,

With the assumptions of quasi-equilibrium (Q(T) = 1), and ignoring the temperature dependencies of s and P compared to the exponential term, Equation (13) becomes

Using Equation (8) and the definitions of Rrt, Rt, Rr, Rnr, and P gives

where subscript i represents the ith trap. Combining Equations (13) and (14) gives us the final expression for TL from the first trap in the IMTS model, as follows:

Examination of Equation (16) reveals that it is in fact the same form as the Randall–Wilkins [65,66] equation for TL, but multiplied by the term and with an effective frequency factor .

Chen and Pagonis [69] pointed out that for small enough the term can be considered as constant during trap emptying. This means that Equation (16) describes a first-order process and is the Randall–Wilkins equation for TL multiplied by a constant. Furthermore, the size of the TL peak is proportional to , and not due to some of the electrons from the trap being localised into other traps, and/or recombining with non-radiative centres, rather than participating in TL emission [71].

If there are many traps and recombination centres in the system, it is likely that for the first trap being small is an expected result. However, in situations where there are many deep traps that cannot be accessed at the temperatures used in a normal glow-curve measurement, this same approximation (of small ) is always likely to be true for each TL peak recorded. That is, we can approximate as constant for many i (not only i = 1) throughout the measurable glow curve. All peaks for which this approximation is true will exhibit a first-order, Randall–Wilkins shape. Depending on the temperatures at which emptying of the deepest traps might occur, the highest-temperature peaks in a glow curve may no longer exhibit a Randall–Wilkins shape (as already noted). However, in insulators especially, the deepest traps can be stable up to many hundreds of degrees Kelvin, and therefore, never observed in a normal TL experiment. For example, deep electron and hole traps have been observed in Al2O3:C, which are stable until 800–1200 K—much higher than the temperatures used in a TL experiment [72].

Therefore, expressions in the form of Equation (16) are the expected expressions describing all TL peaks, for all i except the last one, in an interactive multi-trap system (IMTS), such as that shown in Figure 14. The second-order and general-order expressions (Equations (4) and (6), respectively) are inappropriate for this model, and examples of their use in the literature are incorrect. An advantage of this analysis is that the Superpo sition Principle can be applied, but using Equation (16), not Equation (6).

6.2. Localised Recombination

Any detrapping process in which the detrapped charge accesses the conduction band can also give rise to enhanced conductivity and a thermally stimulated conductivity (TSC) peak at, or near, the same temperature as the TL peak. Indeed, many materials exhibit both TL and TSC, indicating delocalised transitions. (See [8] for detailed analysis of both TL and TSC signals.) However, not all TSC peaks have a corresponding TL peak (implying that any recombination is non-radiative), and not every TL signal has a corresponding TSC signal. Unravelling the detailed relationship between TL and TSC is often non-trivial. The observations that TL signals do not always have a corresponding TSC signal raises the possibility of a localised, not delocalised, transition of the detrapped electron to the recombination site. Such possibilities are illustrated schematically in Figure 15 and are likely to arise when the trapping site and the recombination site are closely localised, perhaps in a cluster, as discussed earlier in this paper.

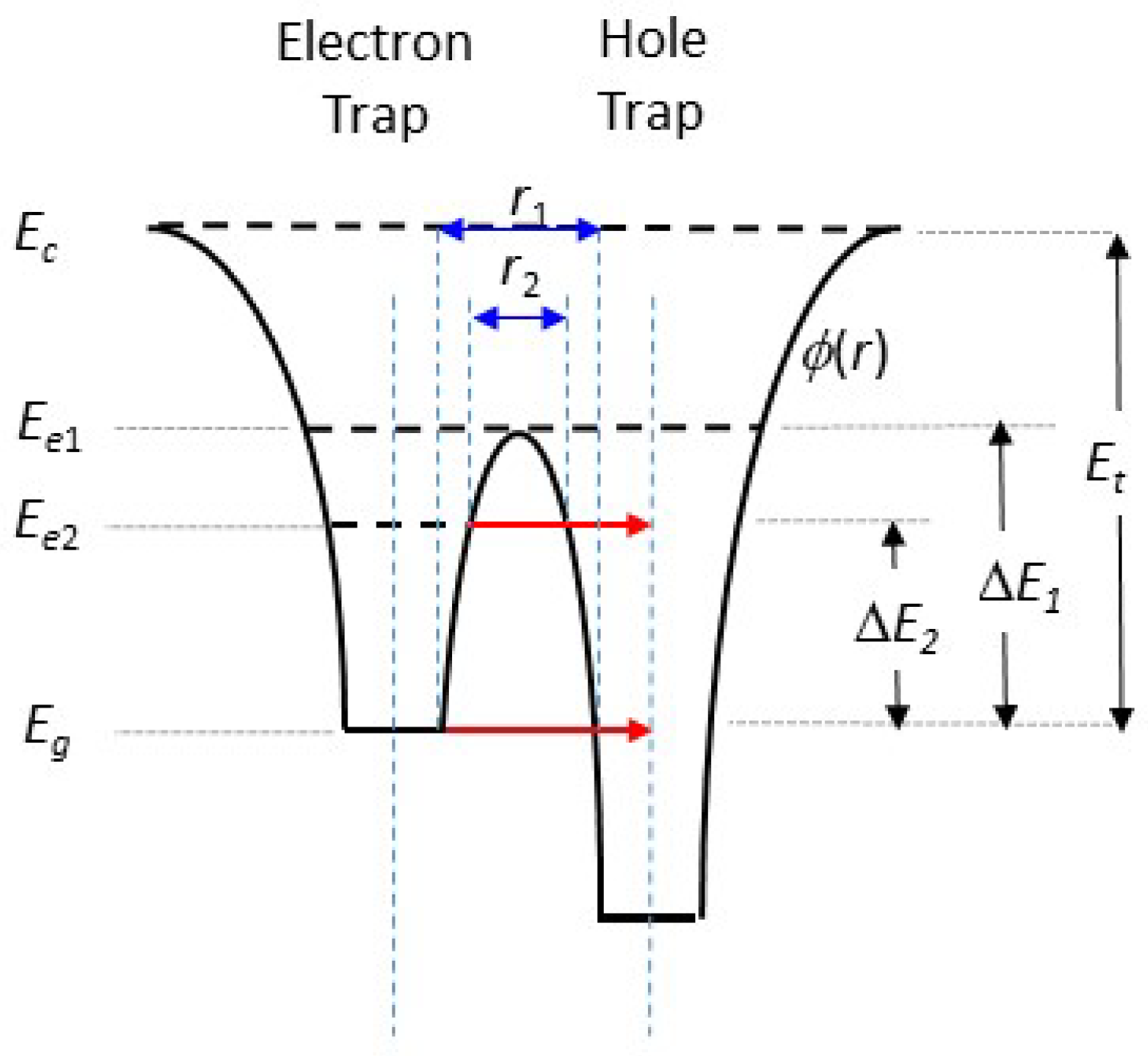

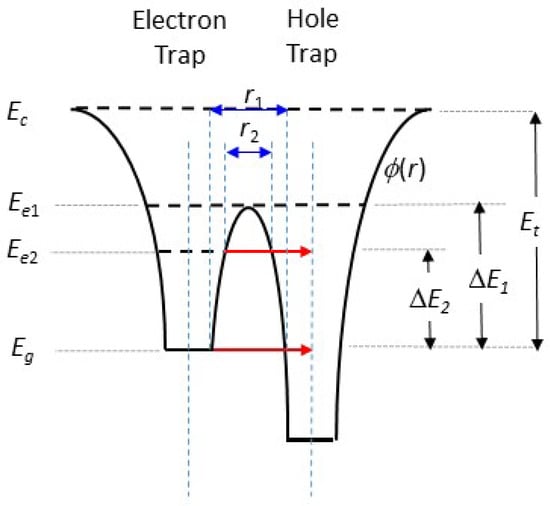

Figure 16 presents two overlapping potential wells ϕ(r) for an electron trap and a localised recombination centre (hole trap), closely separated by distance r1. Absorption of energy Et would delocalise the trapped electron, with a transition from the ground state Eg to above the conduction band edge Ec. However, absorption of energy ΔE1 would enable a localised transition only, above the potential barrier between the electron and holes traps at Ee1. Alternatively, absorption of energy ΔE2 would raise the electron to a lower energy level Ee2, with the possibility of tunnelling through the potential barrier of width r2. This is also only a localised transition. Tunnelling through the barrier from the ground state is also possible, but less likely due to the wider barrier width (r1). When it does occur, it gives rise to athermal fading of the corresponding TL signals [73]).

Figure 16.

Two overlapping potential wells ϕ(r) corresponding to nearby electron and hole traps (recombination centres). Absorption of thermal energy Et excites the electrons above the conduction band edge Ec, whereas absorption of energy ΔE1 raises the electron energy to a level sufficient to surmount the potential barrier between the two sites. Whereas the first is a delocalised transition, the second is a localised transition only. A further thermally stimulated localised transition can be achieved through the absorption of energy ΔE2 to level Ee2. Tunnelling from Ee2 can then result in recombination. Tunnelling from the ground state at level Eg may also be possible. Blue arrows indicate distance while red arrows indicate tunneling.

One has to consider that real materials may contain several species of clusters, each with a corresponding diagram, such as that shown in Figure 15, but with different energy and distance values. As previously noted with regard to the IMTS model, there is likely to be a multiplicity of trapping and recombination sites, including different cluster types.

If the concentration of electrons in the ground state is ng, the rate of a delocalised transition in Figure 15 due to thermal excitation from the ground state to the conduction band is dng/dt = ngsexp{−Et/kT). When this is multiplied by the probability of radiative recombination, Equation (9) is obtained, leading to the expression for TL given in Equation (15).

A description of TL from the localised transition, Eg to Ee1, follows the early work of Halperin and Braner [74] and can be found in many texts [5,8,10,69,75,76]. The following assumptions are usually adopted: (i) the recombination rate is proportional to the concentration of electrons in the excited state Ee1; (ii) the principle of detailed balance applies; and (iii) the system is in quasi-equilibrium. With these assumptions, the TL intensity can be written as follows:

where is the rate of recombination (in s−1) from the excited state and K is the rate of relaxation of excited electrons, with concentration ne, back to the ground state. The term is then the probability of recombination. With the above assumptions, we may also write that ng ≈ m (quasi-equilibrium) and K ≈ s* (detailed balance). Therefore, Equation (17) becomes

This is also a first-order equation, so the final TL peak will also follow a Randall–Wilkins shape. Note that the frequency factor s* does not have the same value as the frequency factor s. The former is a localised transition only, for which the entropy change is ΔS, much less than for the delocalised transition. Since the frequency factor is proportional to exp (ΔS/k) [5], one can expect much smaller values for s* compared to s.

A key assumption in the above analysis is that the recombination rate γne depends only on the electron concentration at Ee1, and not the trapped-hole concentration m. This is because excited-state electrons can only recombine with their nearest-neighbour holes and not with any other, non-local holes. The excited state is localised in the trap–centre complex and, since only local transitions via the excited state are allowed, the above is an inevitable consequence. Delocalised transitions would be required in order to recombine with holes located elsewhere. An exception to this would be if there existed an array of localised/semi-localised states, such as band-tail states caused by a high degree of disorder. In such a case, thermal excitation into the band-tail states may result in longer-range recombination via either thermal hopping or percolation. Band-tail states, for example, are typical in natural feldspars and disordered materials ([12] p. 317, and [77]).

Simulations by Bull [6] show that for the quasi-equilibrium condition to hold, s* has to be ≥ γ. Since s* < s (or even s* << s), then is also < s, (or even << s). Recalling also that Et > ΔE1, an important consequence of these combined inequalities is that a TL peak due to a delocalised transition can appear around the same temperature as that due to a localised transition. They will be distinguished in shape, however, since TL from a delocalised transition, with large Et and s, will be taller and narrower than the TL peak due to a localised transition, which has smaller ΔE1 and and will therefore be shorter and broader.

6.3. Tunnelling

Derivation of the expression for TL due to excited state tunnelling proceeds along a similar path. First, one writes the probability of thermal excitation to the excited state Ee2 and then multiplies this by the probability of tunnelling. The latter is given as follows:

where p0 is a frequency factor, α is a tunnelling constant, and r is the separation between the donor (electron trap) and the acceptor (hole trap/recombination centre). With usual assumption of quasi-equilibrium, this leads to an expression for TL:

where ΔE2 is the activation energy defined in Figure 15, and s* is again assumed to be the relaxation rate from Ee2 to Eg. Assuming a constant value for p(r), Equation (20) has the form of Equation (17), and a first-order TL peak can be anticipated. For a fixed cluster configuration, we might consider r to be constant, at r = r2 (see Figure 15), in which case, p(r) is a value fixed of p(r2). However, if there is a variety of cluster configurations, it may be more accurate to consider r to be a variable, in which case tunnelling may proceed via nearest-neighbour donors and acceptors first, then next-nearest-neighbours, and so on. A fixed r implies a constant p, whereas a variable r as recombination proceeds implies a non-constant function, p(r).

Jain et al. [78] assumed a random distribution of donor–acceptor distances and solved the relevant rate equations to show how the TL peak shape varies with parameter ΔE2, s*, and the number density of acceptors. Based on this work, Kitis and Pagonis [79] subsequently derived an analytical expression for TL due to tunnelling, as follows:

where the function F(t) is defined as

In the above expressions, z is a constant (fixed by Kitis and Pagonis [79] at a value of 1.8), n0 is the initial concentration of trapped electrons, β is the heating rate, and is the normalised number density of the acceptor sites.

These somewhat cumbersome expressions are the only expressions to date that can be used for peak-fitting of TL peaks when tunnelling with a random distribution of donors and acceptors is suspected. However, this may not be a good model for situations where one has a cluster of trap and recombination centres. In the latter case, a fixed r may be a better approximation, in which case the TL expression will be first-order and follow the Randall–Wilkins shape.

6.4. Thermal Quenching

The above analyses assume that the TL glow curves are unaffected by thermal quenching. When thermal quenching is present, the luminescence efficiency of the luminescence site decreases as the temperature increases. Therefore, if the glow peaks being monitored appear over the same temperature range that thermal quenching occurs, the peaks will be distorted, specifically narrowed on their high-temperature side, and not amenable to the type of analyses noted above. Although the phenomenon of thermal quenching has been known for decades and generally follows the Mott–Seitz law, tests to see if thermal quenching is present and, if found, corrected for, are often absent in TL analysis works. Examples in the literature were recently given by McKeever [71], who also emphasised the importance of correction by using simulations to illustrate the possible effects. McKeever also demonstrated an experimental example using TL from Al2O3:C.

7. Conclusions

Thermoluminescence dosimetry and thermoluminescence explorations of imperfections in insulating materials has been extremely valuable for dosimetry and applications in archaeology, etcetera, as well as opening many new opportunities for a wide range of fields involving insulating crystals and powders. Less obvious is that the nominally successful data are often obtained with a range of experimental flaws or weaknesses that seriously undermine attempts to make detailed and accurate analyses of factors such as process activation energies and frequency factors. Suggestions cited here can improve on numerous aspects of experimentation and processing that might enhance performance and further insights into the underlying science. This article has also attempted to explain why, despite about 70 years of usage, and thousands of publications, it is incredibly difficult to quantify and justify structural models of the lattice sites and the interactions that are involved in thermoluminescence. Whilst models, even incorrect ones, are essential to try to understand, quantify, and improve performance, the reality is that modelling so far has been oversimplistic, as we lack the detailed evidence and experimental techniques that would truly help. In particular, once one recognises that extremely long-range interactions are involved, then modelling might improve, but realistically this requires far greater experimental sophistication than is currently available. One must find, not just more speculative site models, but ideas and demonstrations for new types of explicit and detailed measurements. We, as users of TL, see a strong future even at the current level of understanding, but suspect the community (including ourselves) has not addressed the true level of detail that is required, nor focussed on exploring more powerful analytical analyses.

Immediate progress could be made in temperature measurements, which currently are unequivocally extremely poor in dosimetry applications. Fortuitously, this systematic error may not significantly distort measurements of radiation dose or age assessments in archaeology, etc. However, it introduces very significant errors in assessment of activation energies, frequency factors, and site modelling and, as mentioned, prevents comparisons with many other techniques. Therefore a truly beneficial novel experiment is required to assess the true sample temperature. Fortuitously, techniques exist that could be readily included in many TL systems with spectral resolution.

Temperature calibration could readily be made in parallel with TL recording, allowing corrections to be immediately applied to TL data. Once established, one would have a better appreciation of the true TL parameters and their correspondence to CL, ESR, ENDOR, RAMAN, EXAFS, optical absorption, or other analytical data. Indeed, none of these techniques seem to be adequately utilized for TL structural modelling although they offer local site details. They are also instructive in terms of the range of possible sites and the role of impurities. For example, in CL studies of quartz, more than 20 different emission band have been recorded, with a diverse range of possible site model interpretations (e.g., Muller [80]).