Photonic Nyquist Pulse Generation Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principle and Design

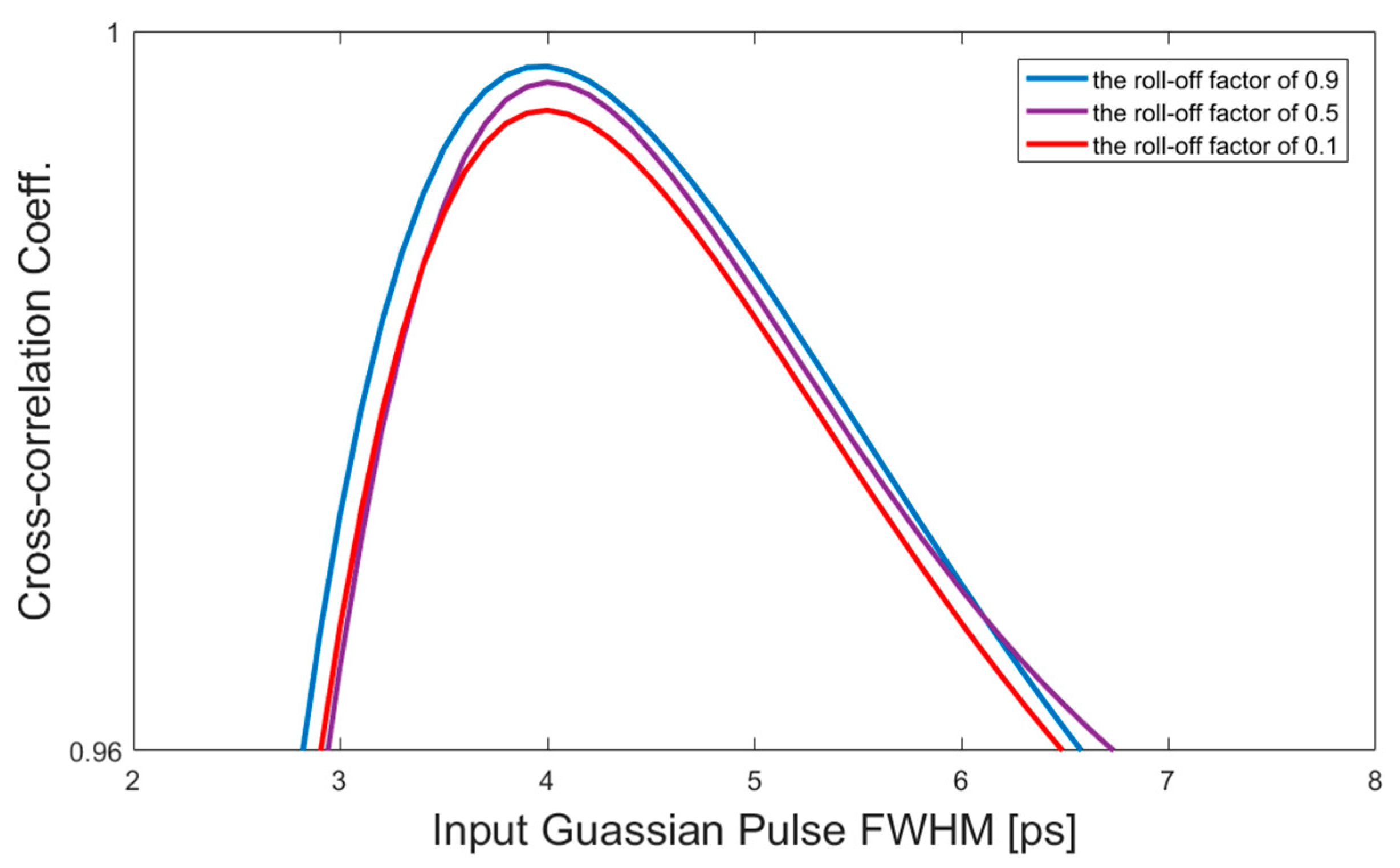

3. Numerical Results and Discussions

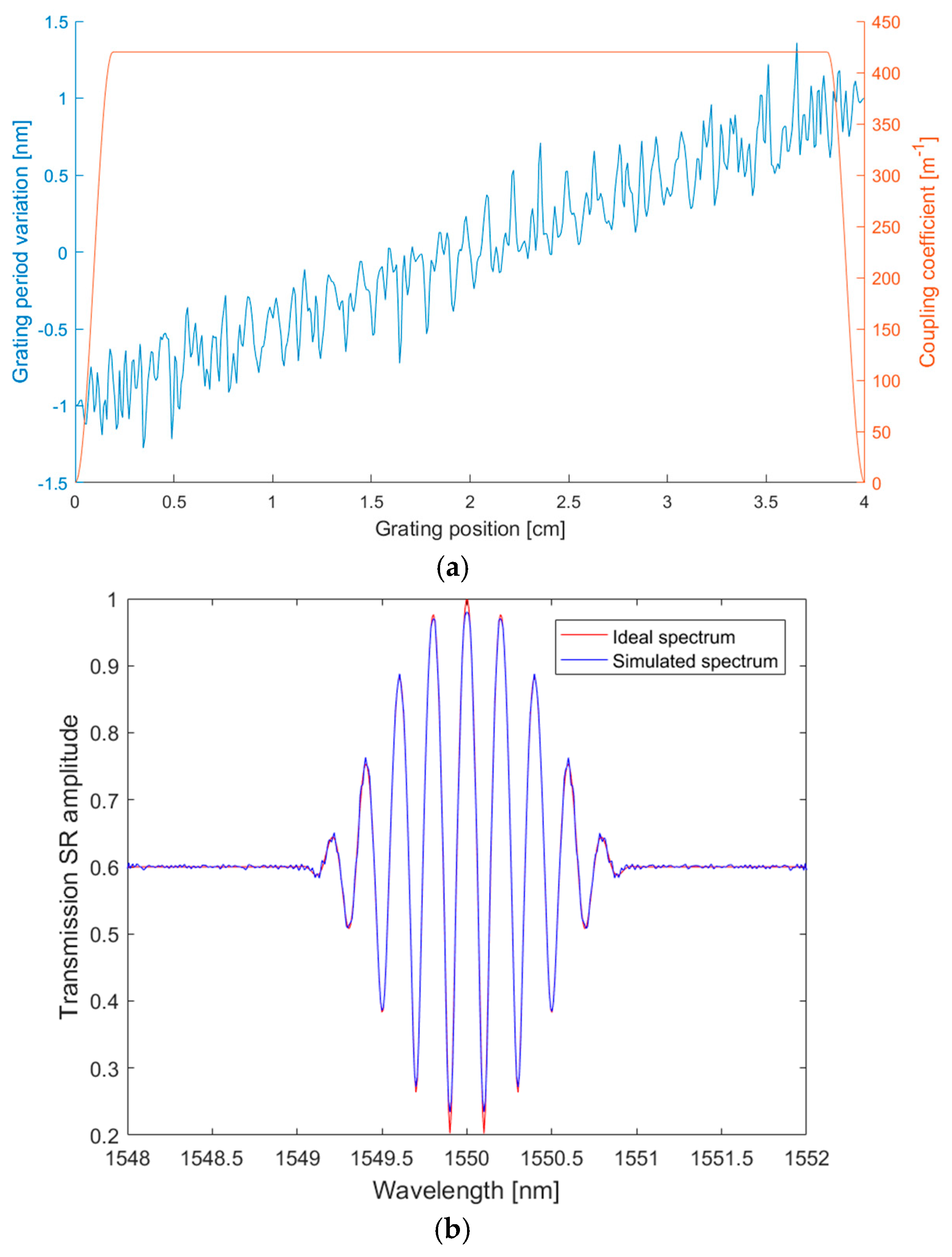

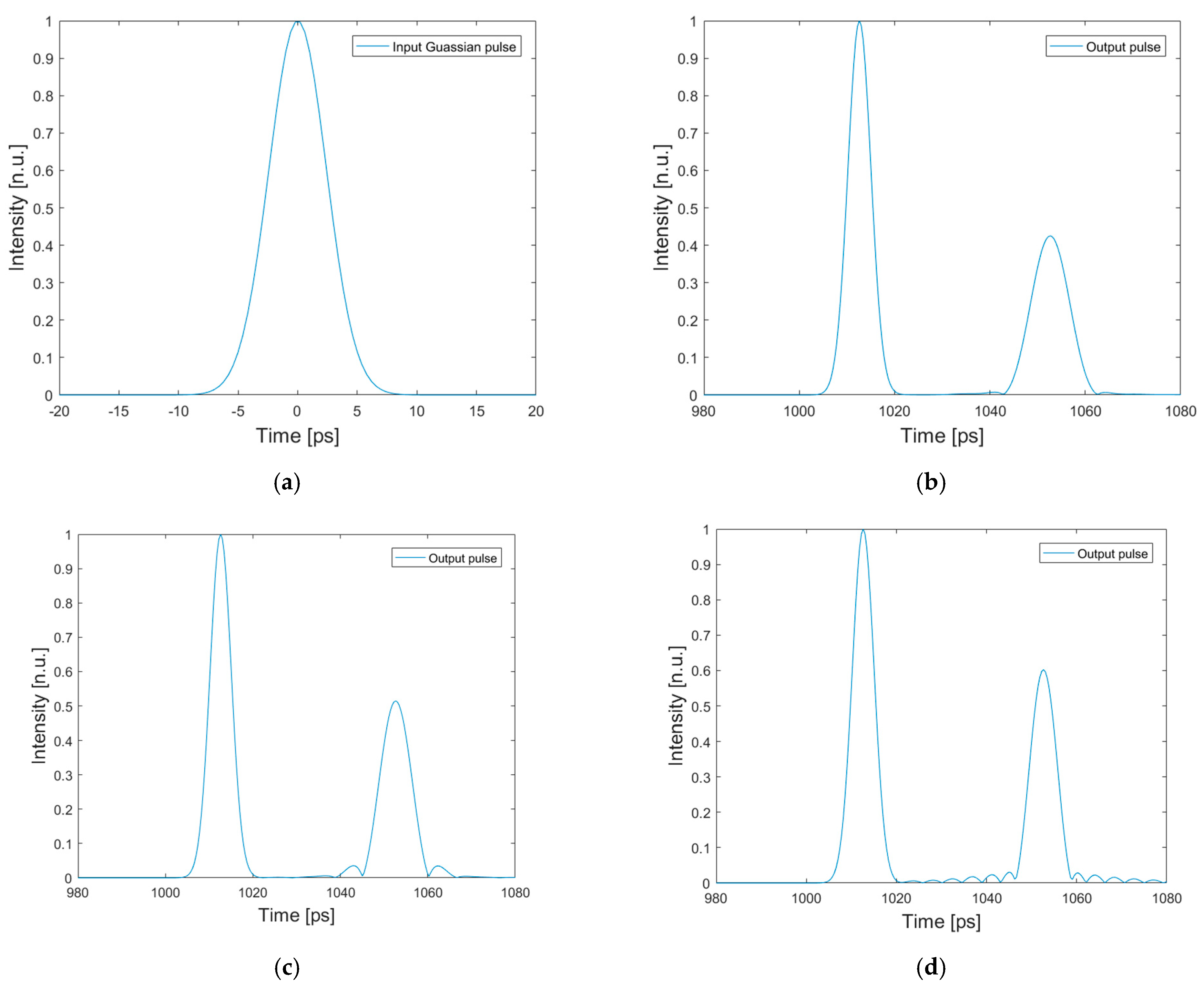

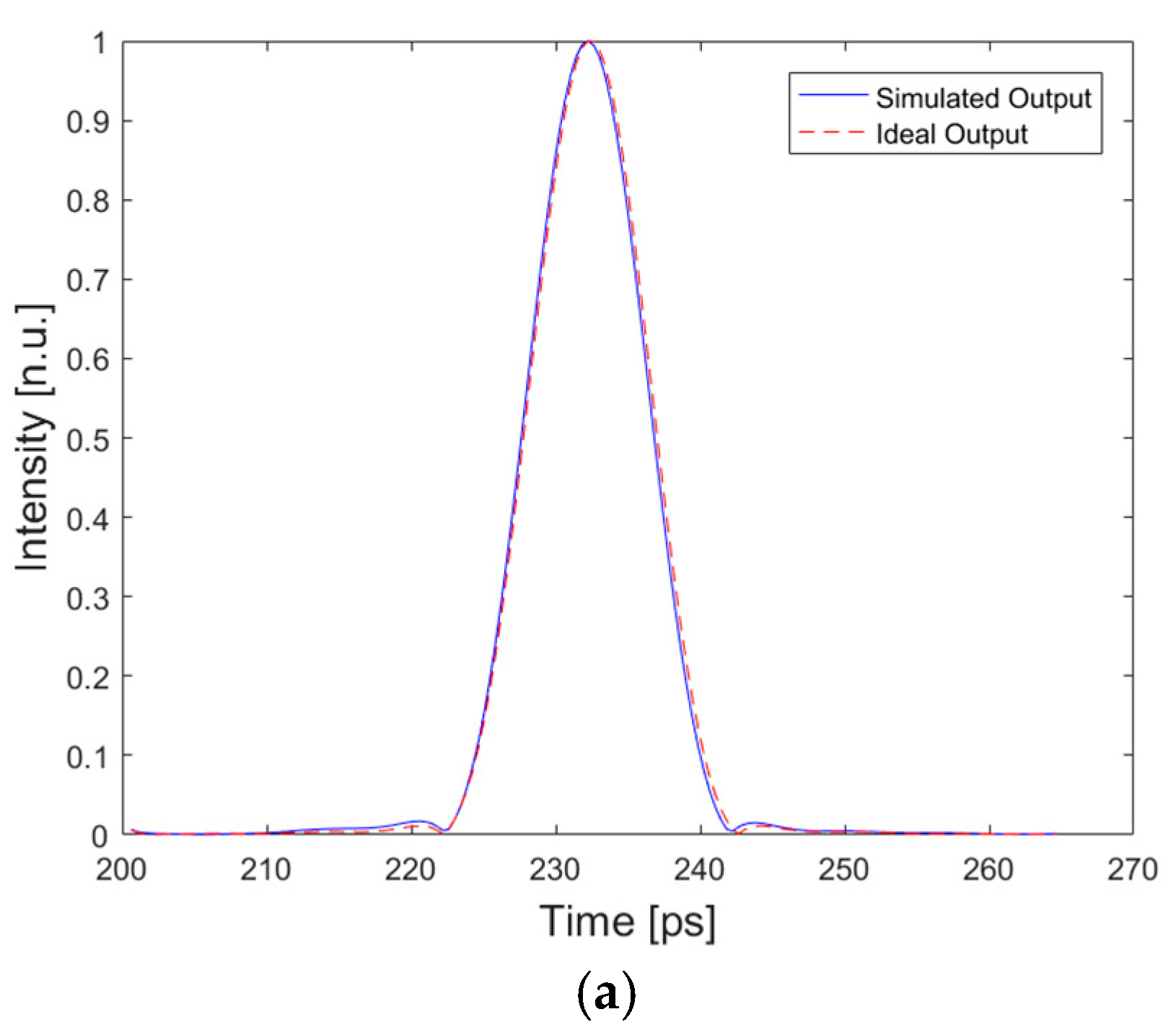

3.1. Roll-Off Factor = 0.9

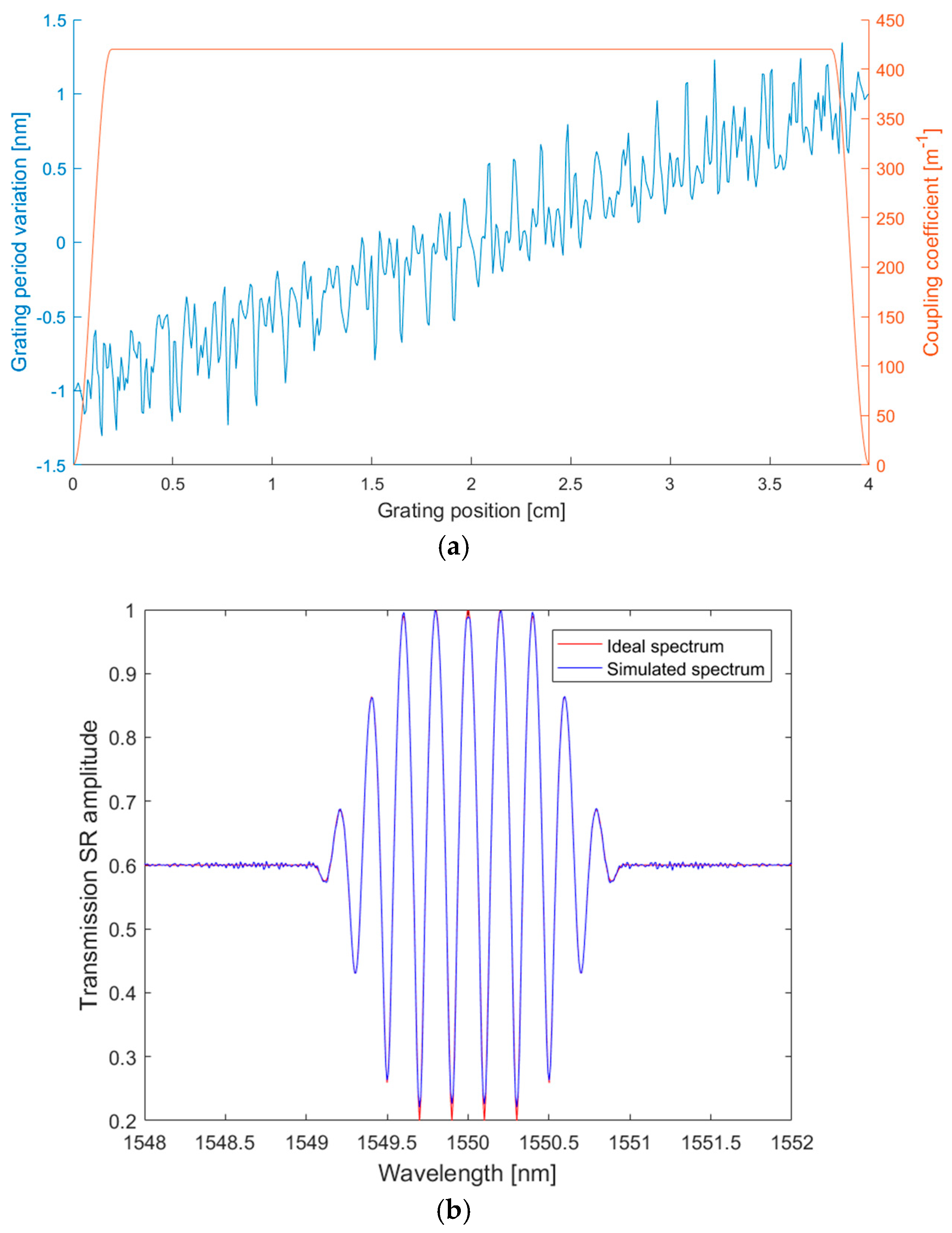

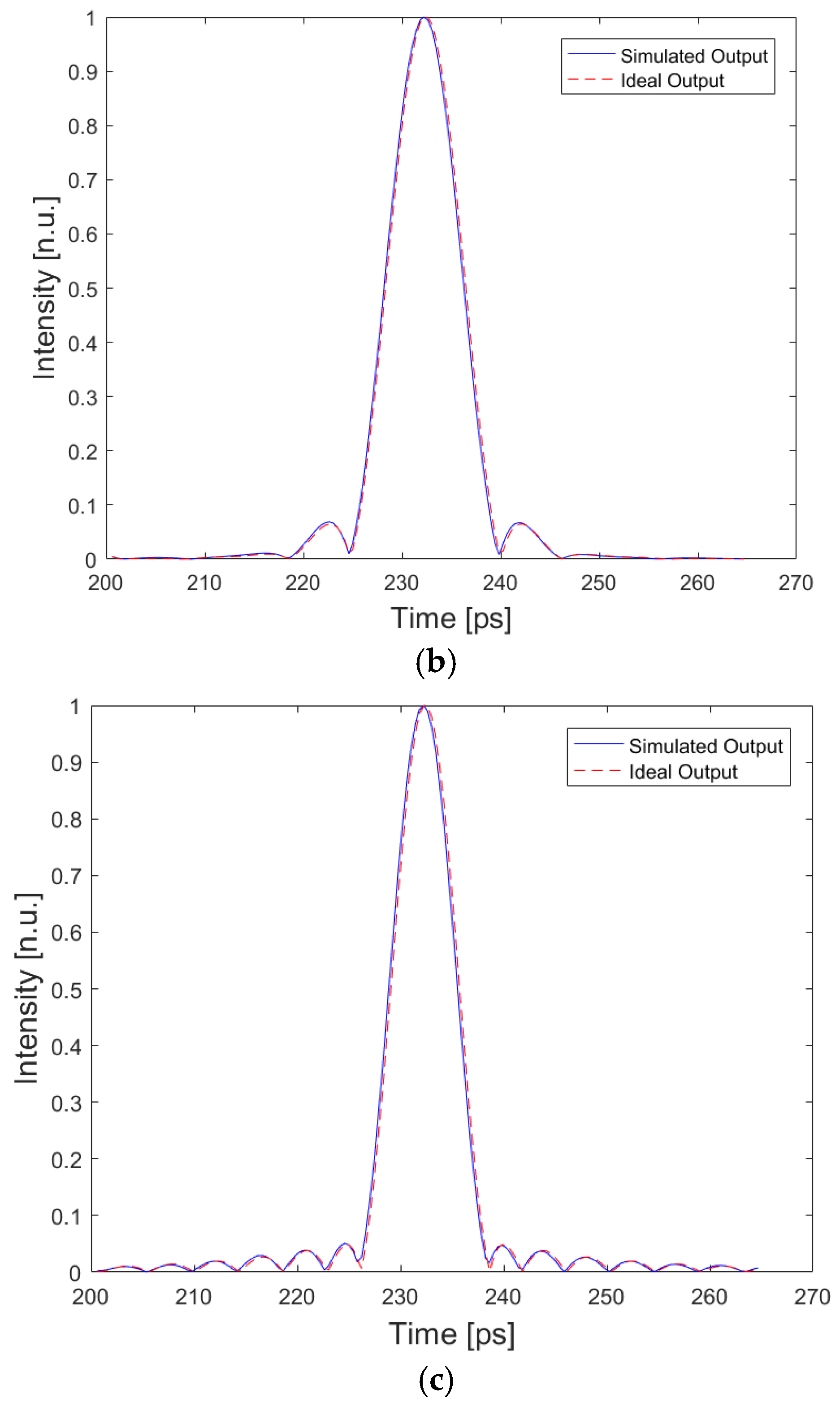

3.2. Roll-Off Factor = 0.5

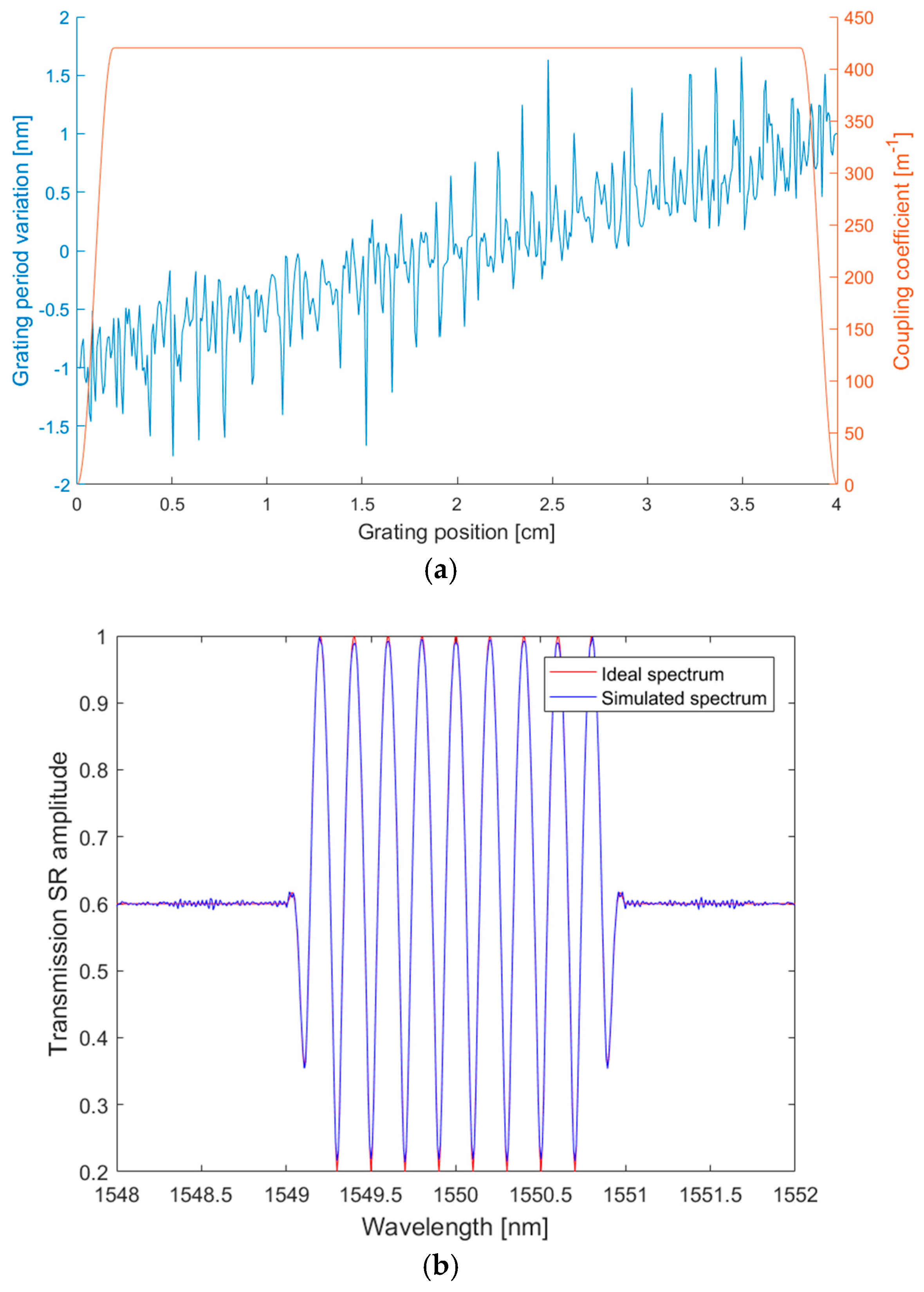

3.3. Roll-Off Factor = 0.1

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Proakis, J.G.; Salehi, M. Digital Communications; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Venema, L. Photonic technologies. Nature 2003, 424, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo, S.; Finot, C.; Turitsyn, S.K. Optical Nyquist Pulse Generation in Mode-Locked Fibre Laser. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics—European Quantum Electronics Conference, Optical Society of America, Munich, Germany, 21 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, M.A.; Alem, M.; Amin Shoaie, M.; Vedadi, A.; Brès, C.-S.; Thévenaz, L.; Schneider, T. Optical sinc-shaped Nyquist pulses of exceptional quality. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedadi, A.; Shoaie, M.A.; Brès, C.-S. Near-Nyquist optical pulse generation with fiber optical parametric amplification. Opt. Express 2012, 20, B558–B565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordette, S.; Vedadi, A.; Shoaie, M.A.; Brès, C.S. Bandwidth and repetition rate programmable Nyquist sinc-shaped pulse train source based on intensity modulators and four-wave mixing. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 6668–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, T.; Ruan, P.; Guan, P.; Nakazawa, M. Highly dispersion-tolerant 160 Gbaud optical Nyquist pulse TDM transmission over 525 km. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 15001–15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyadi, M.; Chitgarha, M.R.; Mohajerin-Ariaei, A.; Khaleghi, S.; Almaiman, A.; Cao, Y.; Willner, M.J.; Tur, M.; Paraschis, L.; Langrock, C.; et al. Optical Nyquist channel generation using a comb-based tunable optical tapped-delay-line. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 6585–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Zhu, C.; Lowery, A.J. Nyquist pulse shaping using arrayed waveguide grating routers. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 22357–22365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, X.; Sugden, K.; Bennion, I. Virtual Gires-Tournois etalons realized with phase-modulated wideband chirped fiber gratings. Opt. Lett. 2007, 32, 3546–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preciado, M.A.; Shu, X.; Sugden, K. Proposal and design of phase-modulated fiber gratings in transmission for pulse shaping. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Shu, X. Design of Arbitrary-Order Photonic Temporal Differentiators Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission. J. Light. Technol. 2017, 35, 2926–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Shu, X.; Zhang, L. Arbitrary-Order Photonic Hilbert Transformers Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission. Photonics 2021, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preciado, M.A.; El-Taher, A.; Sugden, K.; Shu, X. Spatially distributed delay line interferometer based on transmission Bragg scattering. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 4319–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Preciado, M.A.; Gbadebo, A.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, J.; Yu, Y.; Cao, H.; Shu, X. Transmissive fiber Bragg grating-based delay line interferometer for RZ-OOK to NRZ-OOK format conversion. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 140300–140304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaar, J. Synthesis of fiber Bragg gratings for use in transmission. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2001, 18, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, M.R.; Carballar, A.; Azana, J. Arbitrary Time-Limited Optical Pulse Processors Based on Transmission Bragg Gratings. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2014, 26, 1754–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, A.; Digonnet, M.J.; Kino, G.S. Characterization of fiber Bragg gratings using spectral interferometry based on minimum-phase functions. J. Light. Technol. 2006, 24, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Sugden, K.; Bennion, I. Apodisation of photo-induced waveguide gratings using double-exposure with complementary duty cycles. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 2221–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Shu, X.; Zhang, L. Photonic Nyquist Pulse Generation Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission. Photonics 2026, 13, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010030

Liu X, Shu X, Zhang L. Photonic Nyquist Pulse Generation Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission. Photonics. 2026; 13(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xin, Xuewen Shu, and Lin Zhang. 2026. "Photonic Nyquist Pulse Generation Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission" Photonics 13, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010030

APA StyleLiu, X., Shu, X., & Zhang, L. (2026). Photonic Nyquist Pulse Generation Based on Phase-Modulated Fiber Bragg Gratings in Transmission. Photonics, 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010030