Abstract

We report a comprehensive study of heavy-hole (HH) and light-hole (LH) excitons in a shallow GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As single quantum well (QW) using two-dimensional photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectroscopy, reflectivity in Brewster geometry, and time-resolved four-wave mixing (FWM) with polarization-resolved photon echo (PE) detection. The PLE measurements reveal well-resolved HH and LH exciton states with minimal inhomogeneous broadening, while reflectivity spectra indicate strong light–matter coupling and narrow exciton linewidths, reflecting the high structural quality of the QW. FWM experiments demonstrate two-pulse photon echoes with coherence times of ps for HH and ps for LH excitons. Polarization-resolved PE confirms that the observed signals originate from pure three-level excitonic systems without contributions from trions or donor-bound excitons. Compared to conventional GaAs/Al0.3Ga0.7As QWs, the shallow QW exhibits reduced HH-LH splitting, enhanced optical homogeneity, and robustness against above-barrier illumination, making it a promising platform for coherent optical control and information photonics applications.

1. Introduction

Excitons are quasiparticles formed by a bound electron–hole pair in semiconductors [1,2,3,4,5]. Excitons in A3B5 quantum wells (QWs) grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) serve as model systems for fundamental physics [6,7] and have enabled numerous advances in photonics, including polaritonic devices, coherent optical control (photon echo techniques), resonant excitonic diffraction gratings, and other cutting-edge applications, also paving the way to more complex structures such as quantum well tube nanowires [8]. Many seminal phenomena in polaritonics were first demonstrated using structures containing A3B5 QWs—such as the initial observation of exciton—polaritons in a semiconductor microcavity [9], stimulated polariton parametric scattering [10], polariton superfluidity [11], and the first electrically pumped polariton laser [12]. Likewise, the long dephasing times of excitons in such QWs make them attractive for long-lived optical coherence storage via magnetically controlled photon echoes [13], with magnetic fields several times lower than those required for photon echoes on QW trions [14,15]. The high oscillator strength of excitons has also enabled the creation of resonant diffraction gratings by periodically modulating the exciton resonance broadening with focused ion-beam irradiation of the QW epilayer [16].

Thus, excitons in A3B5 QWs provide a versatile platform for studying resonant and nonlinear light–matter interactions, owing to their well-understood band structure, high crystal quality, and the ability to tailor excitonic properties by adjusting the QW width and barrier composition.

One of the most studied A3B5 QW systems is GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs. In the vast majority of studies, structures with –0.35 are used, as this alloy composition provides the maximum band offset while still maintaining a direct-gap AlGaAs barrier [17,18,19]. Such QWs have been extensively studied and have served as a benchmark system for low-dimensional semiconductor physics for several decades. These investigations have focused on relatively deep quantum wells, where carrier confinement is strong, and leakage into the barriers is negligible.

In contrast, shallow QWs with low aluminum content () represent a distinct and less explored regime of renewed interest today, both for fundamental studies and for the optimization of modern optoelectronic and quantum devices that operate close to the confinement threshold. Information on optical properties of QWs with has been fragmentary [20,21,22,23,24]. It was shown that shallow QWs (with ) exhibit greater robustness of their optical properties under strong resonant excitation compared to traditional structures [25]. This behavior may be due to the absence of unintentional doping in the low-x barriers. The lack of such parasitic charging allows a pure excitonic response without the formation of trions [26], which can be favorable for certain applications. Indeed, low-Al-content QWs have revealed remarkable nonlinear and spin-related phenomena, including long-lived dark exciton populations and spin memory effects under resonant and nonresonant excitation [27,28,29].

In this work, we present a detailed study of the optical properties of heavy-hole (HH) and light-hole (LH) excitons in a shallow GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As single QW. To map out the excitonic energy landscape and recombination pathways, we performed two-dimensional photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectroscopy. The exciton homogeneity and light–matter coupling efficiency were investigated via reflectivity measurements in a Brewster-angle geometry. Finally, the coherent optical properties of the excitons were examined using time-resolved four-wave mixing (FWM) spectroscopy with polarization-resolved detection, revealing a photon echo (PE) regime [30]. This comprehensive study shows that shallow GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As QWs exhibit extremely high optical homogeneity, exciton–photon coupling efficiencies comparable to those of standard QWs, and long exciton dephasing times on the order of tens of picoseconds. These characteristics make such QWs very attractive for use in information photonics. At the same time, their distinct compositional features provide additional opportunities to tailor properties for applications in which traditional QWs may be less suitable.

2. Sample and Experimental Setup

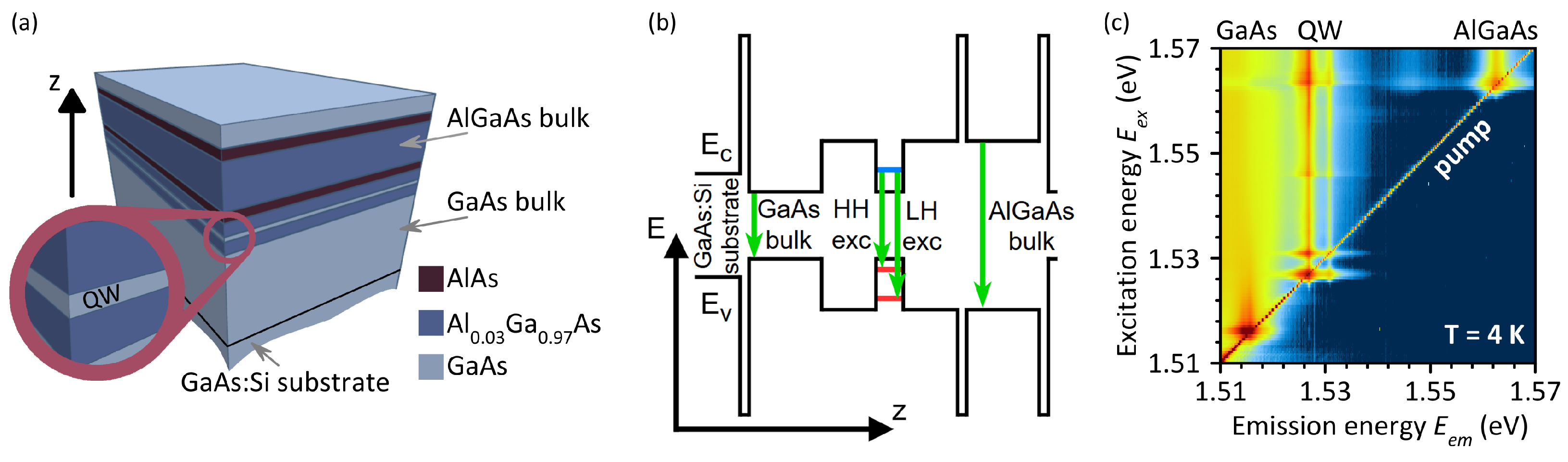

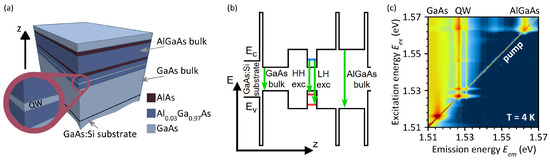

The sample was grown by MBE on an n-doped (001) GaAs substrate. The heterostructure presented in Table 1 and schematically shown in Figure 1a, consists of the following sequence of epitaxial layers: a ∼600 nm GaAs buffer layer, a 14 nm GaAs QW sandwiched between two 51 nm Al0.03Ga0.97As barriers, and a 175 nm Al0.03Ga0.97As layer confined between two 2.8 nm AlAs barriers. The structure is capped with a 7 nm GaAs layer. Thus, in addition to the GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As QW, the sample contains thick (‘‘bulk’’) GaAs and Al0.03Ga0.97As layers that are confined by barriers. The QW is nominally undoped and designed to support well-resolved excitonic transitions with minimal inhomogeneous broadening. The chosen aluminium content is an order of magnitude lower than that traditionally used in QWs, but still allows one to obtain distinct excitonic signals that are sufficiently detuned from the GaAs bulk resonance.

Table 1.

Epitaxial heterostructure studied.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the epitaxial heterostructure consisting of a 14 nm GaAs QW with Al0.03Ga0.97As barriers, and bulk GaAs and Al0.03Ga0.97As layers (details in the text). (b) Schematic band diagram of the heterostructure showing the conduction and valence band edges and optical transitions. (c) Two-dimensional PLE map showing the emission intensity as a function of excitation energy and emission energy . The false-color scale represents the emission intensity on a logarithmic scale, increasing from black (lowest intensity) through blue to red/dark red (highest intensity). K.

Optical measurements were performed at temperatures close to liquid-helium temperature (4 K for PL, 8 K for reflectivity, and 1.5 K for FWM) in closed-cycle helium cryostats. The temperature differences between the various experiments have a negligible influence on the exciton linewidths and HH-LH splitting, as phonon-induced broadening and dephasing are weak in this range compared to inhomogeneous and radiative contributions. The FWM measurements were performed at the lowest temperature to minimize decoherence and, thus, access the longest exciton coherence times. PL was excited by a tunable continuous-wave (cw) Ti–sapphire laser (Avesta TIC, Avesta Project Ltd., Troitsk, Moscow, Russia), with a beam power of 50 W focused to a ∼10 m spot through a 20× microscope objective, which was also used for PL collection. Crossed linear polarizers in the excitation and detection paths were used to suppress stray laser light.

Reflectivity spectra were measured using a broadband femtosecond Ti–sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics Tsunami, Spectra-Physics, Milpitas, CA, USA) as a white-light source. The measurements were performed in Brewster geometry, with the light incident at the Brewster angle (around ) and P-polarized, thus eliminating nonresonant reflection from the sample surface [25,31,32]. In this case, the reflectivity features of the QW appear as symmetric peaks whose shape is independent of the QW’s depth in the sample, since the reflection from the QW does not interfere with the surface reflection.

The emission and reflection were analyzed with a spectrometer based on an LOMO MDR-4 (LOMO JSC, Saint Petersburg, Russia) monochromator (600 mm focal length, 1200 lines/mm diffraction grating, 75 m slit width, 1:8 aperture) equipped with a cooled Andor iDus (Andor Technology, Belfast, UK) CCD camera, providing a spectral resolution of ∼0.2 meV.

The FWM signal was excited by two 3-ps pulses from the same mode-locked Ti–sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics Tsunami, repetition rate 80 MHz). The average power of each pulse was 25 W. The laser excitation spot had a diameter of approximately 100 m. The pulses had wavevectors and close to normal incidence, with an angular separation of ≈0.5°, thus isolating the FWM signal in the phase-matched direction in reflection geometry.

The temporal resolution of the FWM signal was achieved by cross-correlation with a reference pulse from the same laser source. Detection was performed using a balanced photodetector (Newport 2107, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA). A double modulation scheme was employed to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio: a fast modulation at 1 MHz using acousto-optic modulators (introducing frequency shifts of +80 MHz and MHz to the first and reference pulses, respectively) and a slow mechanical modulation of the first pulse at 1 kHz. Delay lines in the reference and second excitation pulse paths enabled time-resolved measurements of the FWM signal. For FWM polarimetry, Glan polarizers and half-wave plates were inserted in the excitation and reference beam paths.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Photoluminescence Excitation Spectroscopy

Unlike a single PL spectrum, a PLE map allows one to obtain comprehensive information about the energy landscape of the system [33]. In PLE spectroscopy, the PL intensity is analyzed as a function of two energies: the excitation energy and the emission energy . By fixing the emission energy and varying the excitation energy, one obtains the excitation spectrum. This approach enables the identification of absorption features with insight into possible energy transfer pathways contributing to the observed emission. Figure 1c presents a two-dimensional PLE map, showing the dependence of the photoluminescence (PL) intensity on the excitation energy on a logarithmic intensity scale. Each horizontal slice of the map represents the PL spectrum for a specific excitation energy . The diagonal line is the scattered signal of the pump laser.

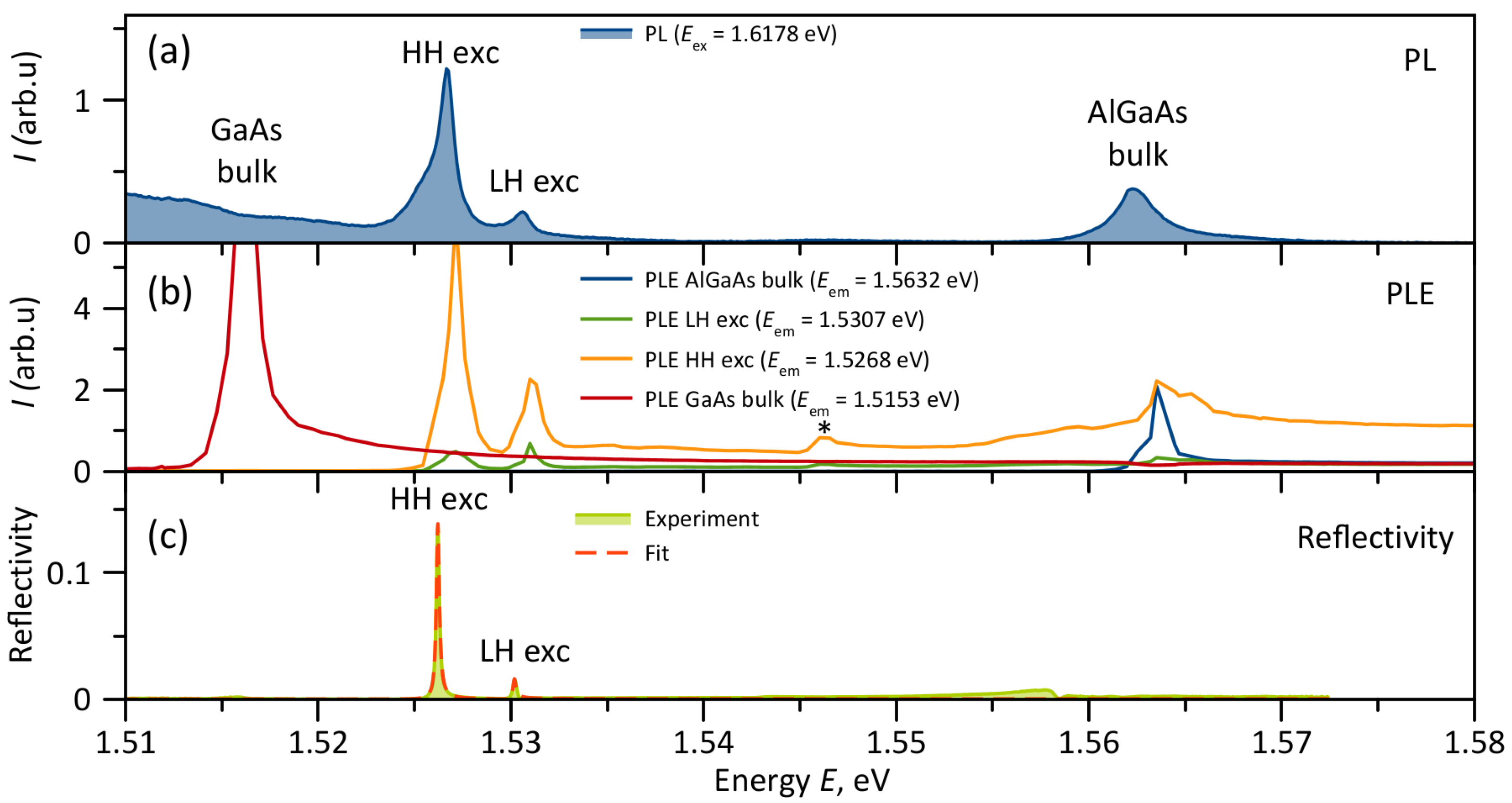

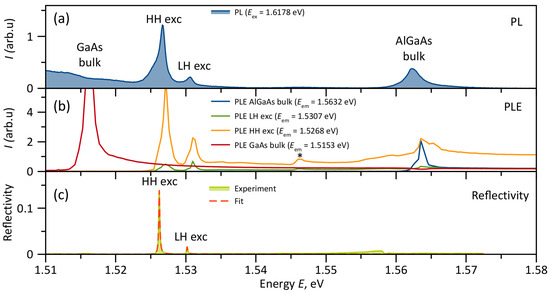

The PL spectrum for excitation above the AlGaAs barrier is shown in Figure 2a. It clearly shows peaks related to the AlGaAs bulk [34] and to two QW excitonic transitions—HH and LH excitons.

Figure 2.

(a) PL spectrum for excitation above all resonances ( eV). K. (b) PLE spectra for different emission energies. The asterisk marks the intermediate resonance at 1.546 eV, previously attributed to the third quantum-confined HH-exciton state [28]. K. (c) Reflectivity spectrum (solid line) and its fit (dashed line). K.

The broad PL signal below 1.515 eV originates from the GaAs substrate, which is significantly inferior in quality to the epitaxial layers. The band at 1.515 eV, associated with the PL of bulk GaAs, appears most clearly under resonant excitation (red curve in Figure 2b), when the pump light freely penetrates the overlying wider-bandgap layers.

The HH and LH exciton resonances in the QW are located at 1.5268 eV and 1.5307 eV, respectively. The small inhomogeneous broadening of the QW results in narrow resonance widths on the order of 0.5 meV. The PLE spectra are presented in Figure 2b. In the PLE spectrum for HH exciton emission, a pronounced resonance at the LH exciton energy is observed. The PLE spectra also show the reverse process: excitation of LH excitons under HH exciton pumping, which corresponds to phonon absorption. This anti-Stokes phenomenon will be reported in detail elsewhere [35].

No pronounced trion emission at energies below the exciton resonances was observed at any excitation intensity. The PLE spectra for the exciton resonances also show a peak at 1.546 eV. Such an intermediate state was previously suggested to be the third quantum-confined state of the HH exciton [28]. The even wave function of this state provides stronger exciton–light coupling than the odd wave function of the second confined state, which leads to its manifestation in the spectrum [28].

The highest-energy state in the system is the AlGaAs bulk state. Since this layer is the uppermost in the structure, its resonant absorption at 1.563 eV can also be observed as a dip in the excitation spectrum of the GaAs substrate emission. However, resonant excitation of the AlGaAs layer also excites the QW excitonic states, which can be explained by energy transfer from the AlGaAs layer to the QW.

Thus, PLE spectroscopy reveals well-resolved exciton states in the QW. It should also be noted that, unlike QWs with , in our case, the barrier absorption resonance falls within the tuning range of common Ti–sapphire lasers, significantly expanding the possibilities for experiments with excitation or additional illumination of the barrier, such as selective barrier excitation and carrier transfer, pump–probe experiments, and QW excitonic population control without direct QW excitation.

3.2. Reflectivity

While PLE spectroscopy allows even the weakest spectral features to be revealed, reflection spectroscopy is sensitive to those states where the main oscillator strength is concentrated. A convenient way to measure reflection is to use Brewster geometry. This geometry allows for the complete suppression of background reflection from the sample surface, so the reflectance from features associated with QW excitons appears most clearly. Furthermore, the absence of interference from the background leads to a nearly undistorted Lorentzian resonance shape, which can be easily fitted by a model of uncoupled Lorentzian oscillators.

Independent measurements of the resonant reflectivity coefficient and the full width of the exciton resonance can be used to separate the two main contributions to the linewidth: the radiative width and the nonradiative broadening [25]. The nonradiative broadening arises primarily from homogeneous temperature-dependent broadening and inhomogeneous broadening due to QW imperfections. By performing measurements at liquid helium temperature, the temperature-dependent contribution is suppressed, allowing a direct determination of the inhomogeneous broadening.

Figure 2c shows the reflectance spectrum measured in Brewster geometry. The choice of the incidence angle equal to the Brewster angle ( in this case) and P-polarization of incident light made it possible to reduce the non-resonant background reflection to the level below 0.001. As expected, in this case, the reflection from exciton resonances takes the form of peaks since there is no interference with the background.

Figure 2c also shows the fit results, which demonstrate excellent agreement with the experiment. The extracted positions of the exciton resonances are eV and eV. Thus, the splitting between these resonances is only meV. The radiative widths of the resonances are eV and eV, respectively. These values are only slightly smaller than those reported for GaAs/AlGaAs QWs with [25]. The ratio between the radiative widths is in good agreement with what is expected from the selection rules for exciton transitions in QWs [36]. The nonradiative broadenings of the resonances are comparable: eV and eV. At such low temperatures and in the linear excitation regime, the main contribution to these linewidths comes from inhomogeneous broadening of the excitonic resonances, arising due to sample imperfections and compositional inhomogeneities. This is evidence of the high quality of the QWs, as the nonradiative broadening for the HH exciton is only about twice its radiative broadening.

Thus, reflectance spectroscopy shows that excitons in these shallow QWs interact effectively with light, while simultaneously exhibiting narrow resonances, owing to the high quality of the epitaxial structures.

3.3. Photon Echo

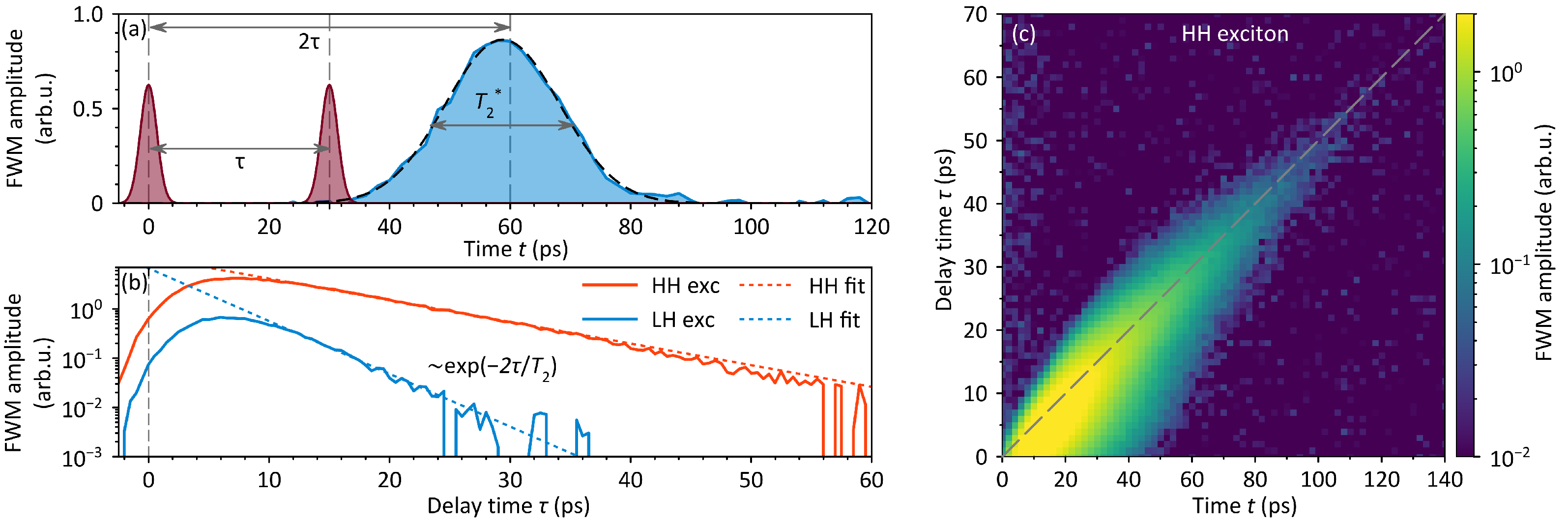

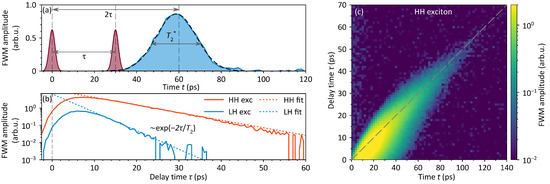

To assess the shallow QWs for coherent optical control applications, FWM and PE experiments were performed. Figure 3a shows the time profile of a coherent FWM signal from a HH exciton resonance with sequential excitation by two coherent laser pulses separated by ps. This profile exhibits a peak centered at a delay time of 60 ps. The appearance of such a time-delayed coherent signal at is a manifestation of the two-pulse PE. The total width of this pulse corresponds to a reversible phase relaxation time ps.

Figure 3.

(a) Time-resolved FWM profile recorded at an emission energy of 1.526 eV (HH exciton). The red curves schematically represent the excitation pulses; the blue curve shows the measured FWM signal in the direction. The dashed black line is a Gaussian fit yielding a dephasing time ps. (b) PE decay (FWM amplitude at as a function of ) for the HH (red) and LH (blue) excitons, corresponding to excitation at 1.526 eV and 1.530 eV, respectively. Dashed lines represent exponential decay fits, yielding coherence times ps (HH) and ps (LH). (c) Two-dimensional map of the FWM temporal profile as a function of for the HH exciton. The dashed line shows the dependence. Note that the time axes in (a,b), as well as the two time axes in (c), differ by a factor of 2, which is related to the dependency.

Figure 3c shows a two-dimensional map, each horizontal slice of which represents a time profile for a different delay. The map shows that the PE signal lies along the line, even for large , deviating from this dependence only at short delays.

The irreversible phase relaxation can be determined by measuring the decay of the PE, i.e., the dependence of the FWM amplitude at on . The PE decays for both QW excitons are shown in Figure 3b. An exponential fit yields coherence times ps for HH excitons and ps for LH excitons. Such decay times are comparatively long for states with strong radiative decay.

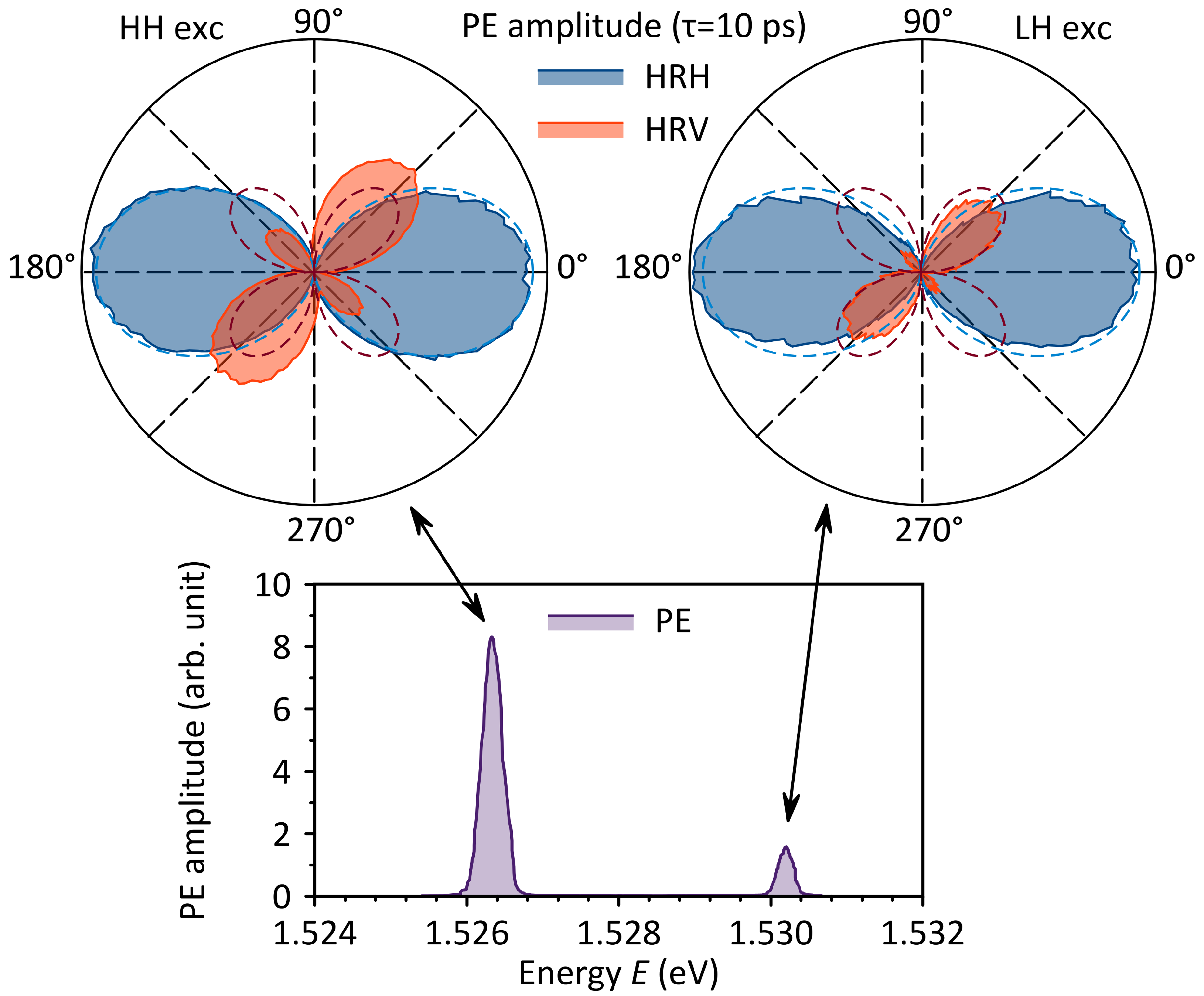

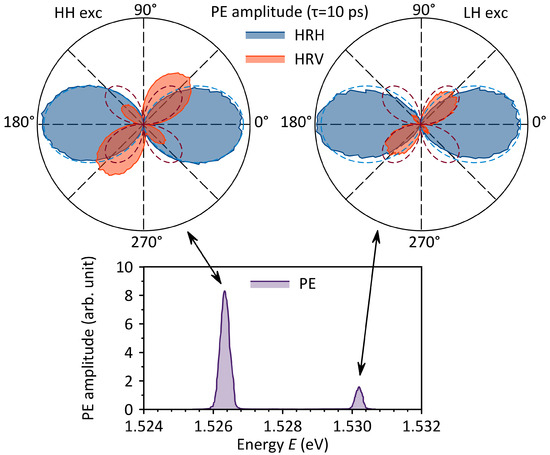

Picosecond laser pulses enable the measurement of temporal profiles and decays; at the same time, their relatively narrow spectral width allows for spectral measurements by selectively exciting individual excitonic resonances. Figure 4 shows the PE spectra for ps. These spectra reveal well-resolved HH and LH excitonic resonances.

Figure 4.

PE spectra for a delay time ps and polar plots in HR→H (blue) and HR→V (red) geometries for HH and LH excitons. Dashed curves show the theoretical fits. K.

Information about the optical transitions involved in the formation of the PE signal in QWs can be obtained using PE polarimetry [37,38]. For this purpose, the linear polarization of the first excitation pulse and the detection (reference) pulse are fixed, while the linear polarization of the second pulse is rotated. Such experiments are denoted by the notation AB→C, where A is the polarization of the first pulse, B is the polarization of the second, and C is the polarization of the detection pulse. The polarization states are designated H for horizontal (laboratory frame), V for vertical, D for diagonal, and X for cross-diagonal. A rotation of the polarization plane is indicated by R.

Figure 4 shows representative polar plots HR→H and HR→V for HH and LH excitons at ps. Such polarization measurements allow us to unambiguously distinguish signals generated by a three-level exciton system from those of four-level trion systems or donor-bound excitons. In particular, the HV→H signal should be absent for an exciton, whereas for trions it should be equal to the HH→H signal. Furthermore, for trions the HD→V and HX→V signals should have the same amplitude as the HH→H signal, whereas for excitons, they should be only half as large. It is clear that the experimental data in Figure 4 correspond to the typical behavior of excitons. The dashed lines show fits based on the theoretical dependencies for excitons presented in Ref. [37]. Minor discrepancies are due to imperfect polarization in the setup. It should also be noted that the exciton signal we observe completely lacks the HV→H component that has been reported for excitons in other semiconductors and attributed by those authors to various nonlinear processes [38,39].

PE measurements of excitons in the shallow QW show that these states exhibit long decoherence times (tens of picoseconds), can be independently addressed spectrally, and represent pure three-level excitonic systems that strongly interact with light. Thus, exciton resonances can be used to implement protocols for manipulating and storing optical coherence.

3.4. Special Aspects of Shallow QWs

The results presented above indicate that shallow QWs are, in many respects, not inferior to conventional GaAs/AlGaAs QWs with . In particular, the radiative linewidths, HH-LH exciton splittings, and optical coherence times observed here are comparable to typical values reported for deeper QWs, where HH-LH splittings of 10–20 meV [19], radiative widths on the order of a few tens of eV [40], and coherence times ranging from a few to several tens of picoseconds [41,42,43] are commonly observed at cryogenic temperatures. At the same time, it is important to highlight several distinctive characteristics of shallow QWs that may offer notable advantages under specific conditions:

- The reduced aluminum content in the AlGaAs ternary alloy significantly diminishes compositional disorder in the barrier material. This leads to smoother potential profiles, reduced interface roughness scattering, and improved spectral homogeneity of confined excitonic states, which are advantageous for high-resolution spectroscopy and coherent optical experiments.

- Although mechanical stresses within the GaAs/AlGaAs heteropair are generally low, in structures with shallow QWs, they are reduced by more than an order of magnitude compared with conventional QWs with . Such low stress not only minimizes strain-induced band mixing but also improves structural stability and reproducibility, which are essential for precision optical and spin-dependent measurements.

- The reduced AlGaAs barrier height leads to a small HH–LH exciton splitting, which strongly influences the probability of phonon-assisted intersubband scattering of excitonic holes. This feature can be exploited in schemes of optical upconversion and laser cooling [44]. Furthermore, the near-absence of strain suppresses additional spin-relaxation channels, making shallow QWs attractive platforms for spin optics and quantum information applications.

- The low barrier height promotes substantial penetration of carrier wave functions into the surrounding AlGaAs layers. This enhances interwell coupling and facilitates tunneling-assisted transport, the formation of extended excitonic states, and collective many-body effects. Such properties can be deliberately engineered to explore coherent coupling, condensation, or transport in coupled QW arrays.

- Shallow QWs demonstrate remarkable robustness against above-barrier illumination, which does not result in appreciable recharging of the QWs. This robustness preserves the purity of exciton states and prevents the formation of unwanted trions, which is a critical requirement for applications in information photonics and coherent control, where the presence of free carriers would degrade performance.

- The bulk and excitonic resonances of the AlGaAs barriers lie within the spectral range of standard Ti–sapphire infrared lasers, enabling straightforward two-beam and pump–probe configurations with above-barrier excitation. By contrast, structures with typically require additional visible-range laser sources for such experiments. This spectral compatibility simplifies experimental setups and broadens the scope of nonlinear and multi-color excitation techniques.

While shallow QWs offer several advantages, as discussed above, they also present intrinsic limitations that must be considered. In particular, the reduced QW depth leads to weaker confinement of electrons and holes, which increases the susceptibility of excitonic states to thermal ionization and carrier escape into the barriers. As a result, excitonic resonances may broaden and decrease in intensity with increasing temperature, and may become difficult to resolve. These factors may set practical limits on the temperature range and excitation conditions under which well-defined excitonic features can be observed in shallow GaAs/AlGaAs QWs.

It should also be noted that the optical methods for characterizing QWs proposed in this work can be used in the future to study QWs with intermediate values of aluminum content in the barriers in order to bridge the gap between deep and shallow QWs.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this work establishes shallow GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As QW as a model system for exciton-related photonics applications. By combining two-dimensional PLE, Brewster-angle reflectivity, and time-resolved FWM with polarimetric control, we demonstrate the simultaneous optical accessibility of HH and LH excitons forming spectrally well-isolated, nearly ideal three-level systems with coherence times extending to several tens of picoseconds. Such a level of spectral purity and coherence has so far been primarily associated with deeper QWs, yet is achieved here in a structure with substantially reduced disorder, negligible built-in strain, and enhanced wave function delocalization.

Beyond providing new insight into exciton coherence in shallow confinement potentials, our results highlight clear and experimentally relevant advantages of shallow QWs over conventional Al-rich structures. These include substantially reduced compositional disorder and mechanical stress, which lead to enhanced spectral homogeneity and reproducibility; a small HH-LH splitting and suppressed strain-induced band mixing, favorable for coherent and spin-selective optical control; and pronounced wave-function penetration into the barriers, enabling engineered inter-well coupling and collective excitonic effects. In addition, the robustness of shallow QWs against above-barrier illumination preserves the purity of neutral exciton states, while the spectral alignment of barrier resonances with standard Ti–sapphire laser systems significantly simplifies experimental implementations and broadens the range of accessible nonlinear and multi-color excitation schemes.

Looking forward, the demonstrated long-lived optical coherences and tunable HH-LH coupling open promising perspectives for studies of coherent control, exciton-based quantum nonlinearities, and the implementation of solid-state platforms for information photonics and quantum technologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/photonics13010019/s1: a ZIP archive containing the underlying numerical data for the figures (text files).

Author Contributions

Investigation, R.S.N., M.A.M., Y.P.E., S.A.E., V.A.L. and Y.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.N. and Y.V.K.; supervision, Y.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation and the St. Petersburg Science Foundation, grant No. 25-12-20007.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out on the equipment of the SPbU Resource Center ”Nanophotonics”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frenkel, J. On the Transformation of Light into Heat in Solids. I. Phys. Rev. 1931, 37, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannier, G.H. The Structure of Electronic Excitation Levels in Insulating Crystals. Phys. Rev. 1937, 52, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.F. Optical spectrum of excitons in the crystal lattice. Il Nuovo Cimento 1956, 3, 672–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenman, G.G.; Peisakhov, A.; Zadok, N. Dispersion of organic exciton polaritons—A novel undergraduate experiment. Eur. J. Phys. 2022, 43, 035301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ersu, G.; Pucher, T.; Kuriakose, S.; Zhang, W.; Al-Enizi, A.M.; Albrithen, H.A.H.; Nafady, A.; Bratschitsch, R.; Island, J.O.; et al. Making exciton physics easy and affordable. Eur. J. Phys. 2023, 44, 055501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, H.; Koch, S.W. Quantum Theory of the Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconductors, 5th ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weisbuch, C.; Vinter, B. Quantum Semiconductor Structures: Fundamentals and Applications; Academic Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Prete, P.; Wolf, D.; Marzo, F.; Lovergine, N. Nanoscale spectroscopic imaging of GaAs-AlGaAs quantum well tube nanowires: Correlating luminescence with nanowire size and inner multishell structure. Nanophotonics 2019, 8, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbuch, C.; Nishioka, M.; Ishikawa, A.; Arakawa, Y. Observation of the Coupled Exciton-Photon Mode Splitting in a Semiconductor Microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 3314–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvidis, P.G.; Baumberg, J.J.; Stevenson, R.M.; Skolnick, M.S.; Whittaker, D.M.; Roberts, J.S. Angle-Resonant Stimulated Polariton Amplifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 1547–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo, A.; Lefrère, J.; Pigeon, S.; Adrados, C.; Ciuti, C.; Carusotto, I.; Houdré, R.; Giacobino, E.; Bramati, A. Superfluidity of Polaritons in Semiconductor Microcavities. Nat. Phys. 2009, 5, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Rahimi-Iman, A.; Kim, N.Y.; Fischer, J.; Savenko, I.G.; Amthor, M.; Lermer, M.; Wolf, A.; Worschech, L.; Kulakovskii, V.D.; et al. An Electrically Pumped Polariton Laser. Nature 2013, 497, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovev, I.A.; Yanibekov, I.I.; Efimov, Y.P.; Eliseev, S.A.; Lovtcius, V.A.; Yugova, I.A.; Poltavtsev, S.V.; Kapitonov, Y.V. Long-Lived Dark Coherence Brought to Light by Magnetic-Field Controlled Photon Echo. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 235312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, L.; Poltavtsev, S.V.; Yugova, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Karczewski, G.; Wojtowicz, T.; Kossut, J.; Akimov, I.A.; Bayer, M. Magnetic-Field Control of Photon Echo from the Electron-Trion System in a CdTe Quantum Well: Shuffling Coherence between Optically Accessible and Inaccessible States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 157403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, L.; Poltavtsev, S.V.; Yugova, I.A.; Salewski, M.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Karczewski, G.; Wojtowicz, T.; Akimov, I.A.; Bayer, M. Access to Long-Term Optical Memories Using Photon Echoes Retrieved from Semiconductor Spins. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitonov, Y.V.; Shapochkin, P.Y.; Beliaev, L.Y.; Petrov, Y.V.; Efimov, Y.P.; Eliseev, S.A.; Lovtcius, V.A.; Petrov, V.V.; Ovsyankin, V.V. Ion-Beam-Assisted Spatial Modulation of Inhomogeneous Broadening of a Quantum Well Resonance: Excitonic Diffraction Grating. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuech, T.F.; Wolford, D.J.; Potemski, R.; Bradley, J.A.; Kelleher, K.H.; Yan, D.; Farrell, J.P.; Lesser, P.M.S.; Pollak, F.H. Dependence of the AlxGa1−xAs band edge on alloy composition based on the absolute measurement of x. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1987, 51, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.L.; Bajaj, K.K.; Phelps, D.E. Energy levels of Wannier excitons in GaAs–GaAlAs quantum-well structures. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koteles, E.S.; Chi, J.Y. Experimental exciton binding energies in GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs quantum wells as a function of well width. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibeldin, N.N.; Skorikov, M.L.; Tsvetkov, V.A. Formation of charged excitonic complexes in shallow quantum wells of undoped GaAs/AlGaAs structures under below-barrier and above-barrier photoexcitation. Nanotechnology 2001, 12, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, S.A.; da Silva, M.A.T.; Dias, I.F.L.; Duarte, J.L.; Laureto, E.; Quivy, A.A.; Lamas, T.E. Correlation between luminescence properties of AlxGa1−xAs/GaAs single quantum wells and barrier composition fluctuation. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.A.T.; Morais, R.R.O.; Dias, I.F.L.; Lourenço, S.A.; Duarte, J.L.; Laureto, E.; Quivy, A.A.; da Silva, E.C.F. The effect of confinement on the temperature dependence of the excitonic transition energy in GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs quantum wells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2008, 20, 255246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochiev, M.V.; Tsvetkov, V.A.; Sibeldin, N.N. Accumulation of the excess of one type of charge carriers and the formation of trions in GaAs/AlGaAs shallow quantum wells. JETP Lett. 2012, 95, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochiev, M.V.; Tsvetkov, V.A.; Sibeldin, N.N. Kinetics of accumulation of excess holes under photoexcitation and their relaxation in GaAs/AlGaAs shallow quantum wells. JETP Lett. 2015, 101, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovev, I.A.; Davydov, V.G.; Kapitonov, Y.V.; Shapochkin, P.Y.; Efimov, Y.P.; Eliseev, S.A.; Lovcjus, V.A.; Petrov, V.V.; Ovsyankin, V.V. Increasing of AlGaAs/GaAs Quantum Well Robustness to Resonant Excitation by Lowering Al Concentration in Barriers. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015, 643, 012085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Joseph, I. Comparative Study of Negatively and Positively Charged Excitons in Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, R10425–R10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, A.V.; Khramtsov, E.S.; Kavokin, K.V.; Ignatiev, I.V.; Kavokin, A.V.; Yugova, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Bayer, M. Nanosecond Spin Coherence Time of Nonradiative Excitons in GaAs/AlGaAs Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 147401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurdyubov, A.S.; Trifonov, A.V.; Gerlovin, I.Y.; Gribakin, B.F.; Grigoryev, P.S.; Mikhailov, A.V.; Ignatiev, I.V.; Efimov, Y.P.; Eliseev, S.A.; Lovtcius, V.A.; et al. Optical control of a dark exciton reservoir. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 035414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, A.V.; Trifonov, A.V.; Sultanov, O.S.; Yugova, I.A.; Ignatiev, I.V. Long-Lived Coherent Dynamics of Heavy- and Light-Hole Excitons in GaAs Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 075302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltavtsev, S.V.; Yugova, I.A.; Akimov, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Bayer, M. Photon Echo from Localized Excitons in Semiconductor Nanostructures. Phys. Solid State 2018, 60, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivchenko, E.L.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Jorda, S. Exciton longitudinal-transverse splitting in GaAs/AlGaAs superlattices and multiple quantum wells. Solid State Commun. 1989, 70, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, W.; Hvam, J.M. Measuring Excitonic Coherence in Nanostructures: Time-Resolved Speckle Analysis versus Four-Wave Mixing. Phys. Status Solidi 2000, 178, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, R.; Lomascolo, M.; Lovergine, N.; Dabbicco, M.; Ferrara, M.; Suemune, I. Excitonic properties of ZnSe/ZnSeS superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 64, 2439–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S. GaAs, AlAs, and AlxGa1−xAs: Material parameters for use in research and device applications. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 58, R1–R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, R.S.; Maksimov, M.A.; Efimov, Y.P.; Eliseev, S.A.; Lovtcius, V.A.; Kapitonov, Y.V. Phonon-Assisted Anti-Stokes Photoluminescence of Light-Hole Excitons in Shallow GaAs/Al0.03Ga0.97As Quantum Well; Manuscript in preparation; Saint Petersburg State University: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Bastard, G. Wave Mechanics Applied to Semiconductor Heterostructures; Les Editions de Physique: Les Ulis Cedex, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Poltavtsev, S.V.; Kapitonov, Y.V.; Yugova, I.A.; Akimov, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Karczewski, G.; Wiater, M.; Wojtowicz, T.; Bayer, M. Polarimetry of photon echo on charged and neutral excitons in semiconductor quantum wells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, A.V.; Grisard, S.; Kosarev, A.N.; Akimov, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Höcker, J.; Dyakonov, V.; Bayer, M. Photon Echo Polarimetry of Excitons and Biexcitons in a CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Single Crystal. ACS Photonics 2022, 9, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.E.; Bolger, J.A.; Smirl, A.L.; Pellegrino, J.G. Time-resolved measurements of the polarization state of four-wave mixing signals from GaAs multiple quantum wells. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1996, 13, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltavtsev, S.V.; Ovsyankin, V.V.; Stroganov, B.V. Coherent resonant scattering and free induction decay of 2D-excitons in GaAs SQW. Phys. Status Solidi C 2009, 6, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheis, L.; Sturge, M.D.; Hegarty, J. Photon echoes from two-dimensional excitons in GaAs-AlGaAs quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1985, 47, 995–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.D.; Cundiff, S.T.; Steel, D.G. Stimulated-picosecond-photon-echo studies of localized exciton relaxation and dephasing in GaAs/AlxGa1−xAs multiple quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 43, 12658–12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cundiff, S.T.; Wang, H.; Steel, D.G. Polarization-dependent picosecond excitonic nonlinearities and the complexities of disorder. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 7248–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Chen, R.; Xiong, Q. Laser cooling of a semiconductor by 40 kelvin. Nature 2013, 493, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.