Abstract

The m-lines spectroscopy is a precise, non-destructive and contactless method, and one of its main applications is the determination of the geometric-optical parameters of a thin film deposited over a substrate, namely the refractive index and the thickness of the film under analysis. The method was first described in 1969 with the seminal work of Tien, more than half a century ago, and, since then, it has been reported in the literature that at least two modal indices of the same polarization are required to unequivocally determine a given film’s refractive index and thickness. This constraint imposes a limit on the waveguide’s thickness, for it leaves out the possibility of determining the geometric-optical parameters of all films where only single-mode propagation is feasible. In this work, we propose and validate a strategy that extends the applicability of the method to single-mode operation, enlarging its operational thickness detection range. Moreover, the results obtained demonstrate that restricting the parameter extraction to fundamental modes leads to a measurable increase in precision. This improvement is attributed to the lower susceptibility to experimental uncertainties, lower sensitivity to surface roughness and nearby structures, and higher confinement that characterize fundamental modes as opposed to higher-order ones.

1. Introduction

M-lines spectroscopy is a non-destructive, contactless and highly accurate technique to optically characterize thin films. Its main functionality is to determine with high precision two fundamental parameters of a given thin layer of material deposited over a substrate: the refractive index and thickness of the deposited film. This method has found applications in industry and academia, with recent increasing adoption by the former, especially where rigorous and precise characterization of dielectric films is a requirement. The following are examples of applications in industry:

- Photonic Integrated Circuit manufacturing

- ○

- Stakeholders: Silicon photonics, optical sensors and telecommunications industries.

- ○

- Industrial Motivation: Enables minimal tolerance over optical and dimensional parameters, thus improving overall coupling efficiency.

- Coatings quality control

- ○

- Stakeholders: Laser components, high precision optics and photolithography.

- ○

- Industrial Motivation: Refractive index and thickness validation of anti-reflection and highly protective coatings, and dielectric mirrors.

- Microelectronics and semiconductor manufacturing

- ○

- Stakeholders: Micro-electro-mechanical systems, sensors and optoelectronics industries.

- ○

- Industrial Motivation: Allows non-destructive analysis of dielectric layers deposited over semiconductor substrates and contactless inspection of layer parameters during or after deposition.

- Functional glass manufacturing

- ○

- Stakeholders: Construction, auto and ultraviolet to infrared protection industries.

- ○

- Industrial Motivation: Non-destructive characterization of solar protective, electrically conductive, hydrophobic, anti-flare and multilayer films on dielectric substrate.

Developments of the m-lines spectroscopy method, as originally established by the work of Tien et al. in 1969 [1], have also taken place through academic research in more recent years. Approaches considering the application of numerical methods to include multilayer heterostructures, multiwavelength and new methods for data analysis, have also been proposed by Schneider et al. [2], where it is claimed the development of an equation for the simultaneous extraction of the refractive index and thickness of a three layer system, and Wu et al. [3], with a multiwavelength m-lines spectroscopy system with claimed advantages for the identification of refractive index profiles and dispersion.

This method is based on the excitation of the allowed propagation modes in a thin film. To achieve this, the modes propagating in the thin film couple into the incoming electromagnetic (EM) radiation through a coupling prism. Each of the allowed modes in the thin film couples at a specific angle of incidence, which corresponds to an interference dip in the reflection intensity graph produced by a monitoring photo detector. These incidence angles on the prism’s edge, at which propagating modes are excited, find direct correspondence to propagating modes in the thin film. Once these angles are known, it is possible to obtain the angles incident at the base of the prism through Snell’s law, and the modal index () of the excited mode is given by the following [4]:

where is the prism’s refractive index. In this work, we designate as the modal index (also referred to as the effective refractive index in the literature) to establish a clear separation from the designation effective refractive index. We reserve the latter to designate the refractive index sensed by an incoming EM beam onto a heterogeneous structure consisting of subwavelength features. The relation between the modal index of the propagating mode and its wavenumber () is as follows:

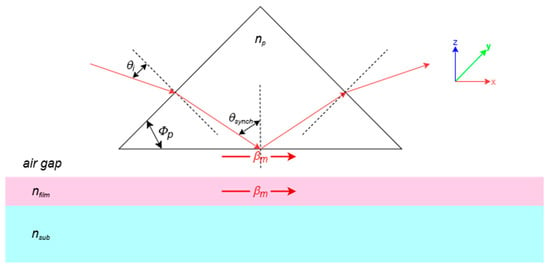

where is the free space wavenumber. Figure 1 presents a diagram depicting the conservation of energy over the wavenumbers of the evanescent and propagating waves and the working principle of the method.

Figure 1.

Representation of the m-lines working principle, where the normal at the point of incidence is depicted by dashed lines, thin red arrows are associated with incoming and outgoing laser beams and thicker red arrows represent the wavenumber () of the wave propagating at both the prism’s base and the thin film.

The method implements the Frustrated Total Internal Reflection (FTIR) principle [5], which consists of the evanescent coupling of a given mode propagating in the thin film into the wave reflected at the prism’s base. Being an evanescent wave, the excitation of a given propagating mode requires proximity between the thin film and the prism’s base. To achieve this, we use a pressure gauge to slightly deform the sample at the point of application of the force, hence diminishing the existing air gap between the prism’s base and the thin film, and enabling evanescent mode coupling. Furthermore, the resonant angles incident at the prism’s edge (the ones measured) and the modal indices of the excited modes are related by the following equation:

where and are the refractive index and the internal angle formed between the base and the edge of the prism, respectively, is the refractive index of the air gap and are the incident angles at the prism’s edge that excite propagating modes in the thin film.

Once we identify coupling features in the reflectance spectrum, the synchronous angles can be calculated using Snell’s law, for the corresponding incident angles at the prism interface —associated with each guided mode resonance—are now precisely known. This information, together with the knowledge of the modal indices of the propagating modes in the thin film, allows determining the refractive index of the thin film layer by solving the following transcendental mode equation:

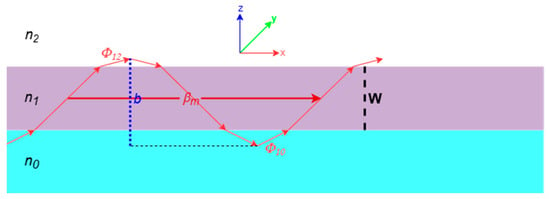

where is the wavenumber-dependent effective width of the thin film (including the wave’s penetration in both substrate and cladding , due to the Goos–Hänchen effect [6]), and is the actual width of the layer. Figure 2 depicts a diagram of the phase evolution of the propagating mode as it progresses in the thin film.

Figure 2.

Phase evolution along the structure with the relevant parameters for calculation and where the black dashed line (W) denotes the film thickness, the blue dashed line indicates the effective width of the guiding region, the thin red arrows illustrate the direction of wave propagation within the thin film, and the thick red arrow represents the propagation constant (βm) of the guided mode.

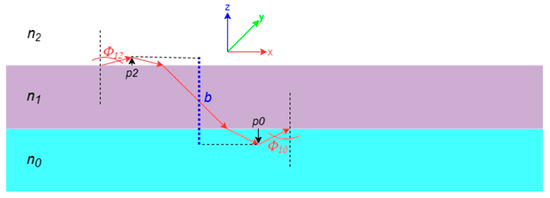

Looking at Figure 3, the terms on the left-hand side of Equation (4) can be further represented by the following expressions, where is the vacuum wavenumber, and and are the refractive index and the wavenumber of the thin film, respectively:

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the terms defined in Equations (8)–(11).

- For perpendicular (free space propagation) [1] and Transverse Electric (TE—assuming propagation along the X-axis and non-vanishing , and field components in the thin film) polarization, we may write the following:

- For parallel (free space propagation) [1] and Transverse Magnetic (TM—assuming propagation along the X-axis and non-vanishing , and field components in the thin film) polarization, the wave’s penetration either in the substrate or in the cladding (air), may be written as follows:

We now have all that is required to express Equation (4) with known quantities, except for the unknown (thin-film refractive index) and (thin-film width) variables. After replacing the terms in Equation (4) with the corresponding expressions in Equations (5)–(11) and algebraic simplification, we obtain the following equations for each polarization:

These are two variable transcendental equations, which are not easily solvable through analytical methods. The usual way of solving these equations is by eliminating the width () variable and performing a division between two equations, each resulting from the expression obtained when considering two different modes of the same polarization. For instance, when considering TE polarization and the modal indices of the fundamental () and first () propagation modes:

Similarly, when considering TM polarization and the modal indices of the fundamental () and first () propagation modes:

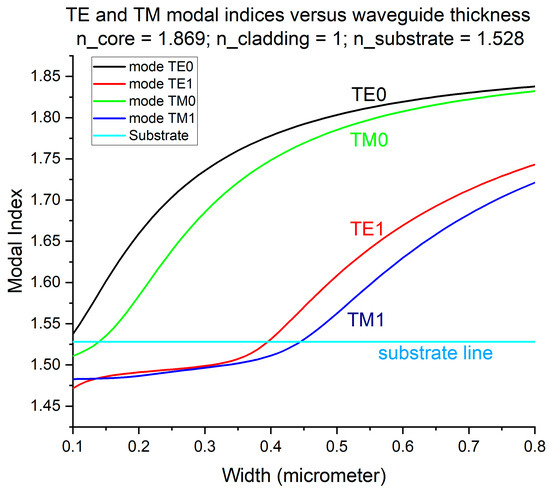

Hence, it has been claimed throughout the years [3,7,8,9,10] that this method requires at least the knowledge of two modal indices of the same polarization to unequivocally determine its refractive index and thickness. This imposes dimensional constraints on the waveguide’s parameters calculation. To illustrate this and as an example, we assume a usual asymmetric thin film deposited over an optical glass substrate with 1.8 and 1.528 refractive indices, respectively, and plot the allowed modes as a function of the thickness of the waveguide, at the operating wavelength of 655 nm. We used FemSIM from RSoft [11,12] to calculate the excited modes, and, as can be observed in Figure 4, the first modes start being excited when the width of the thin film is around 400 nm, more precisely, at ~400 and ~450 nm, for TE1 and TM1 modes, respectively. Thus, since m-lines spectroscopy requires at least two modes of the same polarization to solve Equation (15), this technique is limited to ~400 nm thick films for reliable measurement, considering the asymmetric thin-film configuration, which mode solving analysis led to the graph presented in Figure 4 (air/film/substrate).

Figure 4.

TE and TM modes as a function of the width of the thin film.

In this work, we use the m-lines spectroscopy method to determine the refractive index and thickness of asymmetric thin films by solely utilizing the fundamental mode of each polarization (TE0 and TM0) to calculate the geometric-optical parameters of the deposited film. This way, we avoid the thickness constraint imposed by the two propagating modes of the same polarization requirement for reliable computation, and we are now able to calculate these parameters for much thinner films, only limited in thickness by the degree of asymmetry of the thin film. Namely, and returning to the thin-film configuration presented in Figure 4 (air/film/substrate), calculation is still limited by the refractive index of the substrate, only, this once, by the TM fundamental mode (TM0) instead of the first mode (TM1), corresponding to minimal width W = ~150 nm.

In the next section, Materials and Methods, we present the implemented optical setup with a thorough description of its constituents. Following is the Results Section, where we report our findings and describe all steps and actions performed in this research work. Finally, in Section 4, we present a critically aware assessment of this research work and its findings, discuss our conclusions and define future work directions.

2. Materials and Methods

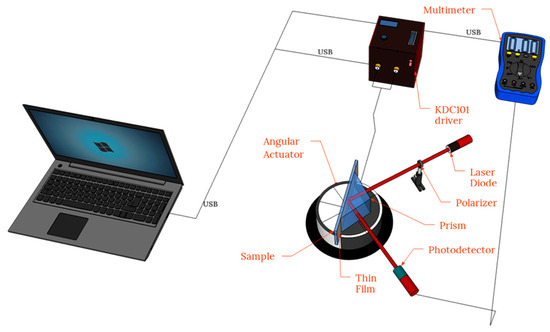

We used an optical setup, which has been previously employed to characterize hydrogenated amorphous silicon nitride thin films for the Photonic Integrated Circuits industry [13,14], to obtain the optical-geometric parameters of an a-SiN2 film deposited over an optical glass substrate. The characterization consisted of determining the refractive index and thickness of the thin film through the m-lines spectroscopy method. We accomplished this by using an optical setup that monitors the photodiode current as a function of the incident/reflected angle. Figure 5 presents a diagram of our optical setup:

Figure 5.

Diagram of the implemented optical setup.

As depicted in Figure 5, the optical setup consists of a 668 nm laser diode (middle right in the above figure), followed by a polarizer (Thorlabs LPVIS100, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany), enabling the selection of parallel or perpendicular polarizations, thus providing the selective excitation of transverse magnetic or Transverse Electric mode resonances; the rotary stage is an angular motor/actuator (Thorlabs PRM1-Z8, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany) and the motor driver (Thorlabs KDC101, Thorlabs GmbH, Bergkirchen, Germany) controls the rotary stage. Attached to the prism holder, there is a pressure mechanism (not represented in the above figure) to exert mechanical force on the backside of the sample’s substrate, thus controlling the coupling of the laser beam onto the modal resonances by adjusting the distance between the prism’s base and the a-SiN2 film. The photo detector is attached to the prism holder to monitor the reflected beam. We monitor the generated photocurrent in the photodetector with a multimeter (Rigol DM-3058, RIGOL Technologies Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). A computer running in-house developed software controls the optical setup through USB connections to drive and monitor the angular movement of the rotary stage and register the photodetector’s current generated by the beam reflected from the prism’s base.

3. Results

We started this research work with a sample consisting of an optical glass substrate with a refractive index similar to very light flint glass LLF1HTi [15], with the thin film deposited on the substrate through Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. The fabrication conditions, deposition and characterization details of the selected silicon nitride sample (a-SiN2) are described elsewhere [16]. We used this sample to test, verify and confirm if the limit in the m-lines spectroscopy method is the thickness necessary to propagate the fundamental modes of both polarizations, Transverse Electric (TE0) and Transverse Magnetic (TM0).

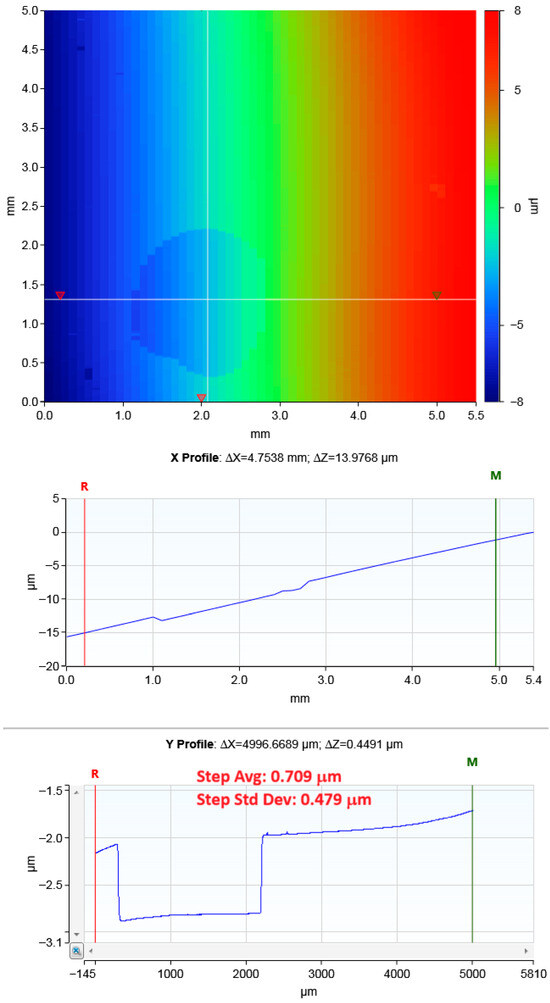

The a-SiN2 sample has also been specially prepared to allow thickness measurement through a stylus surface profiler (Brucker DektakXT), thus providing an independent measurement check. As such, film deposition does not cover the whole sample, leaving out a region of bare substrate, which can be probed by DektakXT. Figure 6 shows a 25 mm2 scan with a 50 µm step over the region where the hole is and the results obtained from the data analysis performed by the stylus surface profiler, with the most important outcome being the detected hole height (Step Avg = 0.709 µm):

Figure 6.

A 50 µm step scan showing the region with no film deposited on and the results obtained from the analysis; the  and

and  symbols correspond, respectively, to the R and M marks in both graphs and represent the measurement boundaries to calculate the average value in both abscissa (X) and ordinate (Y) profiles.

symbols correspond, respectively, to the R and M marks in both graphs and represent the measurement boundaries to calculate the average value in both abscissa (X) and ordinate (Y) profiles.

and

and  symbols correspond, respectively, to the R and M marks in both graphs and represent the measurement boundaries to calculate the average value in both abscissa (X) and ordinate (Y) profiles.

symbols correspond, respectively, to the R and M marks in both graphs and represent the measurement boundaries to calculate the average value in both abscissa (X) and ordinate (Y) profiles.

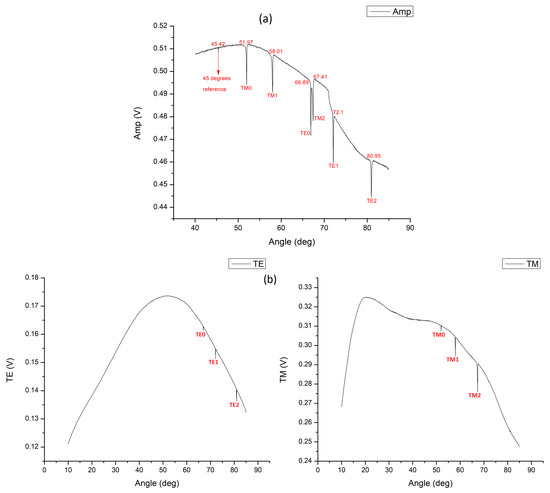

Next, using the m-lines spectroscopy optical setup with the a-SiN2 sample loaded on, we observed the reflectance of the laser beam versus incident angle as presented in Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Photodetector measurements, results obtained with (a) unpolarized EM laser beam and (b) with perpendicular and parallel polarizations.

We obtained these results with an angular step of 0.01°, at the operating wavelength of 668 nm provided by an off-the-shelf laser diode and a polarizer placed in the optical beam path, between the laser diode and the prism. The polarizer has been used to differentiate and unequivocally identify which resonances were related to TM or TE polarization, as depicted in Figure 7b.

In Figure 7a, we may observe seven dips corresponding, from left to right, to the interference of the returning laser beam when at normal incidence on the prism’s edge (at 45.42°), which we use as our 45° reference, and to the modes which have been excited in the film. Follows the resonances at the angles of incidence 51.97°, 58.01° and 67.41°, for TM polarization, and at 66.89°, 72.1° and 80.95°, for TE polarization. We can now use Equation (3) to obtain the modal indices of the excited modes (), given the incident angles at the prism’s edge () and corresponding synchronous angles (). Since these are known quantities, we can solve numerically Equation (4) and determine the refractive index and thickness of the film, if the refractive indices of the substrate, air gap and prism are known.

To perform these calculations, we have developed two MATLAB online live scripts (see the Data Availability Statement):

- m_Lines_SiN2.mlx;

- m_Lines_SiN2_singleMode.mlx.

The m_Lines_SiN2.mlx script corresponds to the standard m-lines spectroscopy calculation method of finding the refractive index and thickness of thin films. Since we observed three resonances for each polarization with the optical setup, we obtained the film’s parameters considering TM and TE polarizations and all combinations with each of them.

As can be observed in Table 1, there is some variability associated with the values calculated by the script in both polarizations, but with greater amplitude in TM polarization. There are reports in the literature that refer to and attribute this variability to the prism’s influence. In fact, if we increase the force exerted on the substrate (diminishing the gap between the film and the prism’s base), we observe a resonance shift and peak widening, with greater impact on the higher-order modes, which affects the calculated parameters. More importantly, the calculated thicknesses are far from the value measured by the stylus surface profiler DektakXT.

Table 1.

Thin-film refractive index and thickness results for TE and TM polarizations (error reported corresponds to the accuracy limit of the angular actuator, 0.03°).

The m_Lines_SiN2_singleMode.mlx and m_Lines_SiN2.mlx live scripts are similar, only we modified the former to calculate both refractive index and thickness with the fundamental modes of each polarization (TE0 and TM0). The following are the results obtained when using the angles of incidence corresponding to the TE0 and TM0 modes after running the m_Lines_SiN2_singleMode.mlx live script:

- Refractive Index = 1.7788 0.0017;

- Thickness = 706.37 15.21 nm.

Both live scripts are available online (see the Data Availability Statement) and may be run with MATLAB Online. Live script editing permissions will be granted upon reasonable request.

4. Discussion

Prior to Tien’s work, there were two main methods for the optical characterization of thin films. One bases its functionality on the optical transmission/reflection spectra [1] and the other on ellipsometric measurements [17] to retrieve the thickness and/or refractive index of thin films. These methods rely on the indirect measurement of the parameters, which are then retrieved by a fitting function, while the m-lines spectroscopy method provides a direct measurement of the thin-film characteristics, thus presenting greater accuracy, and has been successful and independently verified in the literature, including with anisotropic materials [18] and with intensity-dependent refractive index thin films [19].

We started this research work to evaluate the possibility of extending the measurement range of the m-lines spectroscopy method. To this end, we conducted an experimental procedure with a silicon nitride film deposited over a glass substrate. The procedure consisted of using the m-lines spectroscopy method to determine the angular resonances observed in the reflectance of our sample, which correspond to the excited modes propagating in the film, and to measure the thickness of the thin film with a stylus surface profiler (DektakXT), since our sample has been specifically prepared for this task. Finally, we cross-checked the results obtained in both instances of the experiment and determined deviations.

We started by using the angular resonances obtained through the m-lines spectroscopy method to calculate the refractive index and thickness of the film. Initially, we applied the calculation strategy that has been reported in the literature throughout the years, since the seminal work of Tien et al. [1]: the method requires two modes of the same polarization to solve the transcendental equations.

The results obtained are reported in Table 1, and we found a significant difference between the calculated thickness and the value measured by the DektakXT. With the same angular data used before and using the fundamental modes of each polarization, calculations returned the following: refractive index = 1.7788 and thickness = 706.37 nm. Not only is the thickness in very good agreement with DektakXT measurement (Step Avg = 709 nm), but by calculating the optical-geometric parameters with the fundamental modes, we are able to extend the range of application of the m-lines spectroscopy method to thinner films, as it is the main intent of this research work.

Future work will be focused on obtaining a larger number of samples that exhibit these characteristics, i.e., regions where access to the bare substrate is available. Additionally, these samples will have varying film materials and thicknesses. This will enable comprehensive testing and validation of the proposed method under diverse conditions and, if successful, enhance its reliability and applicability across different material systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, P.L.; software, P.L.; validation, A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, A.F.; funding acquisition, P.L. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Portuguese national funds provided by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) program, Center of Technology and Systems (CTS) CTS/00066, and by IPL projects IPL/IDI&CA2024/OPAPIC2D_ISEL and IPL/IDI&CA2024/REFINDEX_ISEL.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://drive.mathworks.com/sharing/14676815-9b5e-40a2-bb34-cc11346421b0 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tien, P.K.; Ulrich, R.; Martin, R.J. Modes of propagating light waves in thin deposited semiconductor films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1969, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Leduc, D.; Cardin, J.; Lupi, C.; Gundel, H. Optical Characterisation of a Three Layer Waveguide Structure by m-Lines Spectroscopy. Ferroelectrics 2007, 352, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Villanueva-Ibañez, M.; Le Luyer, C.; Shen, J.; Mugnier, J. Application of multi-wavelength M-lines spectroscopy for optical analysis of sol-gel prepared waveguide thin films. In Optical Materials and Applications; Rosental, A., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2005; p. 59461E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, P.K.; Ulrich, R. Theory of Prism–Film Coupler and Thin-Film Light Guides. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1970, 60, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E. Optics, 5th ed.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goos, F.; Hänchen, H. Ein neuer und fundamentaler Versuch zur Totalreflexion. Ann. Der Phys. 1947, 436, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.; Torge, R. Measurement of Thin Film Parameters with a Prism Coupler. Appl. Opt. 1973, 12, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T.-N.; Garmire, E. Measuring refractive index and thickness of thin films: A new technique. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardin, J.; Leduc, D.; Schneider, T.; Lupi, C.; Averty, D.; Gundel, H. Optical characterization of PZT thin films for waveguide applications. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 25, 2913–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, J.; Leduc, D. Determination of refractive index, thickness, and the optical losses of thin films from prism-film coupling measurements. Appl. Opt. 2008, 47, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FemSIM. FemSIM—Synopsys. Available online: https://www.synopsys.com/photonic-solutions/rsoft-photonic-device-tools/passive-device-femsim.html (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Lourenço, P.; Vygranenko, Y.; Costa, J.; Fernandes, M.; Fantoni, A.; Vieira, M.; Lavareda, G. Determining Thin Film Characteristics by Prism Coupling Technique. In Doctoral Conference on Computing, Electrical and Industrial Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, P.; Vygranenko, Y.; Fernandes, M.; Fantoni, A.; Vieira, M. Refractive index and thickness analysis of planar interfaces by prism coupling technique. EPJ Web Conf. 2024, 305, 00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refractiveindex.info. Refractive Index Database. Available online: https://refractiveindex.info/ (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Lavareda, G.; Vygranenko, Y.; Amaral, A.; de Carvalho, C.N.; Barradas, N.P.; Alves, E.; Brogueira, P. Dependence of optical properties on composition of silicon carbonitride thin films deposited at low temperature by PECVD. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 551, 120434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manifacier, J.C.; Gasiot, J.; Fillard, J.P. A simple method for the determination of the optical constants n, k and the thickness of a weakly absorbing thin film. J. Phys. E 1976, 9, 1002–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A.; Bashara, N.M.; Ballard, S.S. Ellipsometry and Polarized Light. Phys. Today 1978, 31, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, F.; Endelema, D.; Pelletier, E.; Hodgkinson, I. Anisotropy in thin films: Modeling and measurement of guided and nonguided optical properties: Application to TiO2 films. Appl. Opt. 1993, 32, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigneault, H.; Flory, F.; Monneret, S. Nonlinear totally reflecting prism coupler: Thermomechanic effects and intensity-dependent refractive index of thin films. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.