Abstract

In this paper, we theoretically investigate nonlinearly tunable Fano resonance by employing a light tunneling heterostructure with one-dimensional defective photonic crystals and a lossy metallic film. We find that the phenomenon of Fano resonance can be created by coupling the Fabry–Pérot cavity mode with the topological optical Tamm state. We emphasize that the local field confinement induced by Fano resonance can ensure that the large nonlinear permittivity of metal can be utilized sufficiently. We show that the Fano-type transmission spectrum can be actively modulated by altering the input power intensity of light. We also illustrate that the hysteresis effects and nonreciprocal transmission behaviors can be obtained directly by using the Fano resonant heterostructure, allowing for the realization of high-performance all-optical switches and diodes. Our findings may open up new prospects for the nonlinear topological photonic systems with classical analogue–quantum phenomena.

1. Introduction

Topology is a hot research topic in the field of photonics. It has brought a new degree of freedom to control the motion of photons. Such a core aspect gives rise to an indispensable subject of topological photonics. Recently, topological photonic modes, also called optical Tamm states, have been demonstrated in a variety of artificial micro-structures, including metamaterials, plasmonics, and photonic crystals (PCs) [1,2,3,4]. Among them, one-dimensional (1D) heterostructures composed of paired epsilon-negative (ENG) and mu-negative (MNG) materials are crucial platforms for achieving the optical Tamm states [5,6]. Under the impedance and phase matching conditions, light can transmit through the heterostructures with the reduction in reflection [7,8]. At the light tunneling mode, the electromagnetic (EM) fields are strongly localized around the interface of two opaque medium. In particular, it has been shown that metals can be viewed as ENG materials below the plasma frequencies; meanwhile, 1D dielectric PCs in the forbidden gap can exhibit properties similar to those of MNG materials [9,10,11,12]. As a result, the topological tunneling mechanism can make the bulk metals transparent and boost the local fields in the metals, which prompt the optical properties of metals be utilized effectively for facilitating the nonlinear effect, optical absorption, and optical rotation [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. To date, considerable works on novel physical phenomena behind the light tunneling heterostructures have been carried out. However, to further explore their capabilities to control EM waves, some exotic concepts must be involved.

Fano resonance is a fundamental quantum effect originating from the destructive interference between narrow discrete pathways and broad continuum spectra [21]. It can induce a sharp asymmetric line shape with highly dispersive feature for simultaneously suppressing radiative loss and strengthening near-field localization [22]. Owing to this salient feature, Fano resonance has become the focus in many diverse areas of research, ranging from fundamental physics to abundant applications. Representative examples include nonlinear optics, cavity quantum electrodynamics, high-sensitivity sensing, low-threshold lasing, and narrow-band filtering [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. During the past decade, Fano resonance has been extensively investigated in classical systems, such as metallic nanoparticles, dielectric clusters, dielectric–metal hybridized structures, whispering-gallery micro-resonators, coupled micro-cavities, and asymmetric split rings [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In 2018, the Fano-type spectral profile was also found in a one-dimensional topological PCs hetero-junction [37]. In this case, the produced Fano resonance can be attributed to the weak coupling between a Fabry–Pérot (FP) cavity mode and a topological edge state, which opens up a new prospect for mimicking some quantum optical phenomena. Up to now, significant efforts have been made to generate Fano resonance in topological photonic structures [38,39,40,41,42]. Nevertheless, studies on tuning these Fano resonances in light tunneling heterostructures with the aid of nonlinear metallic layer are still lacking.

In this paper, we theoretically demonstrate nonlinearly tunable Fano resonance by utilizing a light tunneling heterostructure with one-dimensional defective PCs and a lossy metallic film. The metal–PC configuration is developed to excite optical Tamm state and provide a narrow-resonance response. The defective sheet sandwiched between two PCs is constructed to support FP cavity mode and present a broad resonance effect. The destructive interference between the above two types of state results in Fano resonance. At the hybrid coupling mode frequencies, the proposed heterostructure exhibits highly localized EM fields around the metal layer. By introducing third-order nonlinear susceptibility into the metal and altering the input intensity of light, the spectral position of hybrid Tamm–cavity modes can be dynamically tuned. It is also revealed that the hysteresis effects and nonreciprocal transmission behaviors can be established effectively in the heterostructure, allowing for the realization of high-performance all-optical switches and diodes. These results may inspire innovations for researching nonlinear quantum-like interference effect in topological photonic systems.

2. Fano Resonance in Light Tunneling Heterostructures

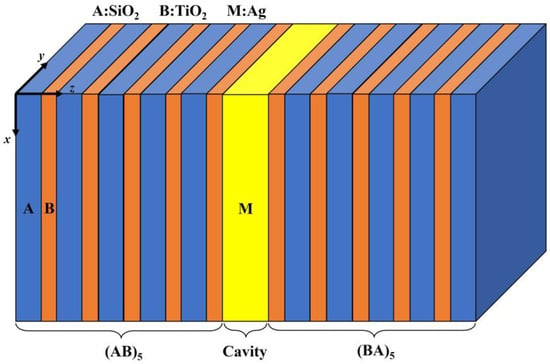

Figure 1 displays the designed Fano resonant heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5, which consists of a metallic film, M, sandwiched between two one-dimensional PCs (AB)5 and (BA)5. A indicates a SiO2 layer with refractive index nA = 1.443, and B represents a TiO2 layer that has the refractive index of nB = 2.327 [43]. The thickness of A and B are dA = 80 nm and dB = 50 nm, respectively. The subscript of the two PCs (AB)5 and (BA)5 means the periodic number is 5. For M, it is selected to be silver (Ag) with a linear dielectric constant of , where is the plasma frequency obtained by and represents the damping calculated with [44]. Ag is assumed to be nonmagnetic and is expressed as , and its thickness is dM = 45 nm. The dielectric function of Ag with cubic nonlinearity is , where is the intensity of electric field and the cubic nonlinearity is chosen as . Numerical results are obtained by using the transfer matrix method, supposing that light incidents normally on the structure in the z direction.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Fano resonant heterostructure with an arrangement of (AB)5M(BA)5.

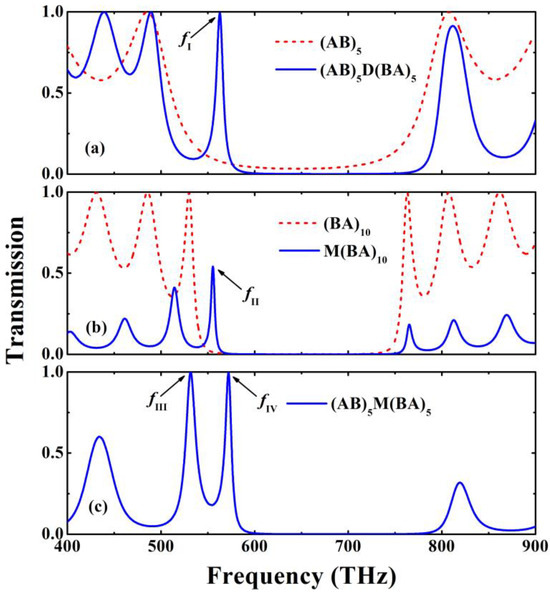

Figure 2 presents the calculated transmission spectra of the defective PCs structure (AB)5D(BA)5, the light tunneling heterostructure M(BA)10, and the Fano resonant heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5. Here, the effective third-order nonlinear and the loss of Ag are not considered. For the (AB)5D(BA)5 structure, the defect layer, D, denotes a dielectric with refractive index nD = 0.130 and thickness dD = 45 nm. These values for D are chosen to match the structural parameters of the metal layer. As demonstrated in Figure 2a, there exists a defect mode located around the frequency of fI = 562.8 THz. Such a mode is a typical FP cavity mode characterized by a Lorentzian shape. The mode is located near the left side of PC (AB)5 bandgap with a relatively small quality factor 65.0. Hence, the FP cavity mode can be well regarded as a broad continuum resonant state. In the case of the M(BA)10 structure, it can be found that the light tunneling phenomenon occurs in the PC (BA)10 bandgap around the frequency of fII = 555.4 THz, as shown in Figure 2b. The quality factor of this mode is up to 115.3. Therefore, such a light tunneling mode can provide a narrow discrete state for the formation of Fano analogue. By combining the light tunneling and the FP cavity mechanisms, the (AB)5M(BA)5 structure exhibits two transmission peaks situated around fIII = 531.6 THz and fIV = 572.0 THz, as shown in Figure 2c. This spectrum corresponds to the prominent Fano-type spectrum. The Fano resonant mode arises from the weak coupling between the narrow light tunneling discrete mode and the broad FP cavity continuum mode. Additionally, the transmission coefficient of the hybrid Tamm–cavity modes are nearly 100%, which are pronouncedly larger than that of the M(BA)10 structure (0.54 at fII = 555.4 THz). Note also that the Fano resonant mechanism in the light tunneling heterostructure is realized without the cost of extra device volume. Consequently, these advantages, combined with the two-band property, are highly desired but difficult to achieve for conventional topological heterostructures.

Figure 2.

Linear transmission spectra for (a) the PC structure (AB)5 and the FP cavity structure (AB)5D(BA)5, (b) the PC structure (BA)10, and the light tunneling heterostructure M(BA)10, as well as (c) the Fano resonant heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5.

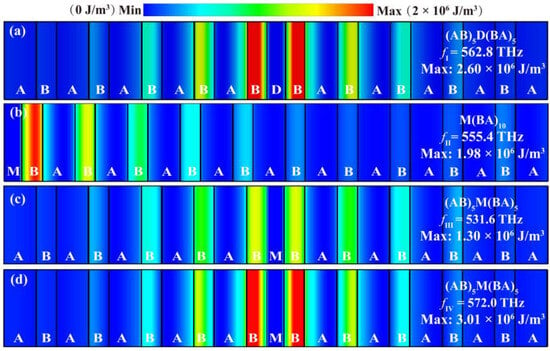

To reveal the underlying physics, the electric energy density distributions of the defective PCs structure (AB)5D(BA)5, the light tunneling heterostructure M(BA)10, and the Fano resonant heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5 were calculated and plotted in Figure 3. For (AB)5D(BA)5 at the frequency of fI = 562.8 THz, the local fields demonstrate a typical standing-wave pattern with a maximum intensity of 2.60 × 106 J/m3, which is indicative of a classic FP cavity response. For M(BA)10 at the frequency of fII = 555.4 THz, it is apparent that the electric fields are highly localized around the interface of the M-PC heterostructure, exhibiting a maximum intensity of 1.98 × 106 J/m3, which is a typical characteristic of the light tunneling effect. When a whole structure is made, as in the (AB)5M(BA)5 structure, the maximum electric field intensity at the hybrid mode of fIII = 531.6 THz is maintained on a high level of 1.30 × 106 J/m3. Meanwhile, at another hybridized coupling mode of fIV = 572.0 THz, the maximum electric field intensity is elevated to a new level of 3.01 × 106 J/m3, which can be attributed to the cooperation of the light tunneling and the FP cavity mechanisms. These two aspects mutually reinforce each other, enlarging the electric energy density around the transparency windows. Such achievements toward EM fields are not only crucial for enhancing light–matter interactions but are also bound to improve nonlinear actions.

Figure 3.

Simulated electric energy density distributions for (a) the (AB)5D(BA)5 at fI = 562.8 THz, (b) the M(BA)10 at fII = 555.4 THz, as well as the (AB)5M(BA)5 at (c) fIII = 531.6 THz and (d) fIV = 572.0 THz. The four characteristic frequencies of fI, fII, fIII, and fIV are marked in Figure 2.

3. Bistable Switching Action

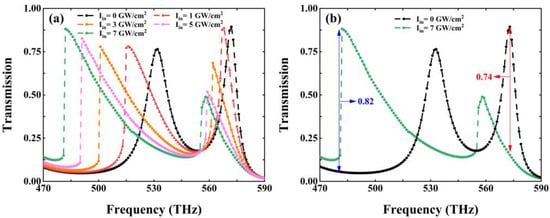

In this part, the nonlinear properties are investigated in the Fano resonant heterostructure by controlling the input optical intensity in the sample. Here, the effective third-order nonlinear and the loss of Ag are considered. Figure 4a shows the calculated dynamic transmission spectra for the (AB)5M(BA)5 heterostructure at five magnitudes of light power, i.e., 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 GW/cm2. It can be seen that the hybrid resonant modes are very sensitive to the input power intensities of light. For no-power or low-power situations, take 0 GW/cm2 for an example: the hybrid resonant modes locate around 531.6 THz and 572.0 THz. When we increase the input power intensity from 0 to 7 GW/cm2, the two hybrid resonant modes become increasingly asymmetric. Quantitatively, the transmission peak at 531.6 THz shifts from the original position to 482.0 THz, displaying a remarkable blueshift of 49.6 THz. In addition, the resonant mode at 572 THz exhibits a distinct frequency shift of 15 THz. Furthermore, the transmission switching behaviors are also showcased via the nonlinearly tunable Fano resonance phenomena. As depicted in Figure 4b, the transmission at 482.0 THz switches from the off-state (0.06) to the on-state (0.88) and the input power changes from 0 to 7 GW/cm2, demonstrating an amplitude modulation depth of up to 0.82. Similarly, within the same bias voltage range, the transmission at 573.0 THz decreases rapidly from the on-state (0.89) to the off-state (0.15), illustrating a modulation ratio of 0.74. From this point of view, the amplitude-modulated property, together with the frequency-agile feature, all reflect the feasibility and effectiveness of the all-optical switching effect based on the proposed Fano resonant heterostructure.

Figure 4.

(a) The calculated transmission spectra for the (AB)5M(BA)5 structure with respect to different input optical intensities ranging from 0 to 7 GW/cm2. (b) The calculated transmission spectra at two typical input powers of 0 GW/cm2 and 7 GW/cm2 for the proposed heterostructure.

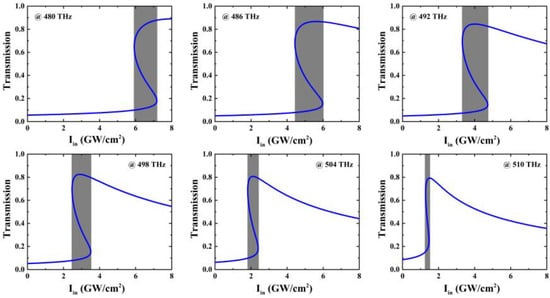

Then, the optical bistable behaviors for this Fano resonant heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5 are investigated in detail. Figure 5 illustrates the calculated transmission in the input power range of 0 to 8 GW/cm2 at six selected frequency points of 480, 486, 492, 498, 504, and 510 THz. Notably, we observe that the hysteresis loops in transmission are clearly formed as varying the input power intensity of light bidirectionally. For instance, at 480 THz, the switching-up and -down thresholds for the bistability are 5.9 GW/cm2 and 7.2 GW/cm2, respectively. Within the input power intensities range defined by the above two threshold levels, multi-valued transmission is achieved at one frequency, generating a maximum transmission contrast over 0.75, which is crucial for the effective performance of nonlinear bistable switches. Moreover, it can be observed that the locations of these hysteresis loops are sensitive to the frequency points. As the monochromatic input signal is adjusted from 480 to 510 THz, the threshold of bistable state is reduced from 7.2 to 1.5 GW/cm2, whereas the transmission contrast is still maintained at a high level of 0.61, which is conducive to meeting the requirements of general all-optical devices. In addition, the widths of the hysteresis loops demonstrate frequency sensitivity. Specifically, as the frequency is altered from 480 to 510 THz, the width of the hysteresis loop is decreased from 1.3 to 0.1 GW/cm2. This property further manifests the suitability of the nonlinear bistable switches. Overall, the low-threshold intensity, large transmission contrast, and relatively wide frequency band indicate that our (AB)5M(BA)5 structure can function as a high-performance all-optical switch.

Figure 5.

The calculated transmission at 480, 486, 492, 498, 504, and 510 THz versus input optical intensities on the sample from 0 to 8 GW/cm2. The gray areas indicate the regions of hysteresis loops.

4. Nonlinear One-Way Transmission Behavior

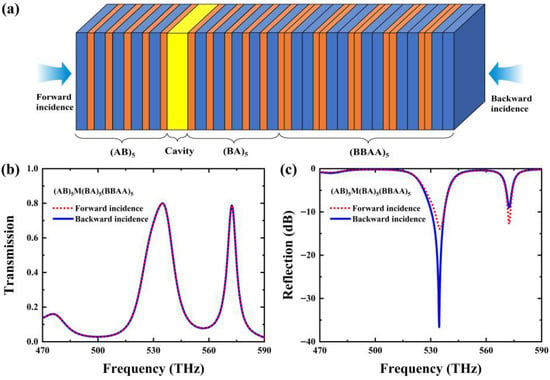

Then, we investigate the nonlinear one-way transmission effect by introducing a Bragg mirror (BBAA)5 on the right side of the Fano resonant heterostructure with an arrangement of (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5, as seen in Figure 6a. The A layers stand for SiO2 and the B layers are selected as TiO2, respectively. The geometrical parameters of the components towards A and B are identical to those shown in Figure 1. The subscript of the Bragg mirror (BBAA)5 means the periodic number is 5, which determines the spatial asymmetry of the structure.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic of the Fano resonant heterostructure with an asymmetric arrangement of (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5. Simulated (b) transmission spectra and (c) reflection spectra for the presented structure under bidirectional excitations.

First, the heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5 is studied at the weak power situation. In Figure 6b,c, we give the calculated linear transmission and reflection spectra of the proposed sample under forward excitation (from left to right) and backward excitation (from right to left). We find that this asymmetric structure exhibits pronounced unidirectionality due to the strong spatial asymmetry of the hybrid Tamm–cavity modes. For the transmission case, we can find that the spectra for bidirectional excitations are almost identical. In contrast, for the reflection case, it is evident that the spectra are dependence on the light propagating direction. Specifically, the reflection at 534.6 THz is −13.7 dB for the forward excitation, while it reaches −36.6 dB for the backward excitation. Likewise, the reflection at 572.4 THz is −12.75 dB for the forward excitation; however, it is −8.97 dB for the backward excitation. These discrepancies suggest that there is a contrast in local fields with respect to the two excitation directions, which is conducive to the promotion of nonlinear one-way transmission behavior in the asymmetric heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5.

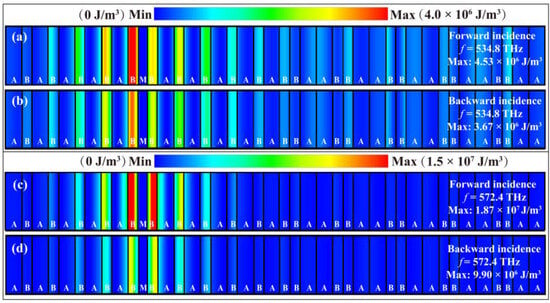

Additionally, the electric energy density distributions for the heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5 are simulated to further elucidate the non-reciprocity nature. Figure 7 exhibits a striking contrast in the confinement strength of electric fields under bidirectional excitations at the hybrid Tamm–cavity modes frequencies of 534.8 THz and 572.4 THz. For forward excitation, we can clearly see that the electric fields at 534.8 THz are highly localized around the interface of the heterostructure with a maximum value of 4.53 × 106 J/m3. Conversely, for backward excitation, we notice that the electric fields are partially reflected by the Bragg mirror (BBAA)5 with a maximum value of just 3.67 × 106 J/m3. Likewise, the maximum electric field intensity at 572.4 THz for forward excitation is 1.87 × 107 J/m3. In contrast, for backward excitation, the electric field intensity is 9.9 × 106 J/m3. Therefore, it can be concluded that the introduction of the asymmetric Bragg reflector indeed enlarges the structural non-symmetry and leads to the establishment of strongly nonreciprocal field localization. In addition, it is also important to point out that the nonlinear response in the proposed structure will be distinct for forward and backward excitations under the same input power intensity.

Figure 7.

Simulated electric energy density distributions for the asymmetric heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5 at 534.8 THz under (a) forward excitation and (b) backward excitation, and at 572.4 THz under (c) forward excitation and (d) backward excitation.

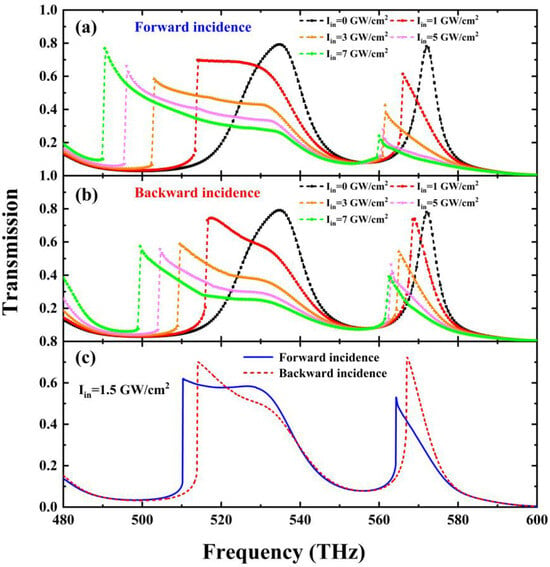

Next, we conducted a detailed investigation on the nonreciprocal nonlinear effect in the heterostructure (AB)5M(BA)5(BBAA)5. In this structure, the nonlinear effects are excited through dynamically regulating the input optical intensity. In Figure 8a,b, under the same input intensity, we can see that the transmission spectra are markedly different in the forward and backward directions. This is attributable to the forward excitation, which effectively enhances the nonlinear response; nevertheless, the backward excitation intensely suppresses it. Consequently, the noticeable discrepancies between forward and backward excitations are formed. Taking the left hybrid Tamm–cavity mode as an example, we can see that, with the input power intensity increasing from 0 to 7 GW/cm2, the mode under forward excitation displaces from 534.5 THz to 490.5 THz, showing a large lateral shift of 44 THz. However, within the same intensity range, the mode situated at 534.5 THz under backward excitation moves to 499.5 THz, indicating a relatively small offset of 35 THz. Moreover, the all-optical diode effects are also showcased via the nonreciprocal nonlinear phenomena. As depicted in Figure 8c, the transmission at 510.3 THz switches from the on-state (0.62) to the off-state (0.06) with the excited direction changes from forward to backward under 1.5 GW/cm2. This demonstrates an amplitude modulation depth of up to 0.56. Moreover, the transmission at 564.3 THz switches from the on-state (0.53) to the off-state (0.15) with the excited direction changes from forward to backward under 1.5 GW/cm2. This indicates an amplitude modulation depth of up to 0.38. These results confirm that the proposed asymmetric hybrid Tamm–cavity heterostructure is well suited for the design of a two-band all-optical diode.

Figure 8.

The calculated transmission spectra under (a) forward excitation and (b) backward excitation with varied input optical intensity ranging from 0 GW/cm2 to 7 GW/cm2. (c) The transmission spectra at the same input power of 1.5 GW/cm2 under bidirectional excitations for the proposed asymmetric heterostructure.

Additionally, we provide a performance comparison between the proposed composite Tamm–cavity structure and other related works. The authors of [17,19] proposed frequency-agile Tamm resonance with amplitude control but achieved only small modulation depths. The authors of [39,41,42] proposed actively controlled Fano resonance with frequency and amplitude control but these can only be achieved at the cost of large device volumes. In contrast, the structure proposed in this work simultaneously achieves large frequency shifts and high modulation depths within a relatively small device size. Furthermore, the composite Tamm–cavity structure offers a two-band advantage over other related works. These properties pave the way for our structure to be applied in new-generation optic communications integrated systems.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have theoretically investigated the nonlinear properties of a light tunneling Fano resonant heterostructure with one-dimensional PCs and a lossy metallic film. The Fano resonance is achieved through the destructive interference between a FP cavity mode and an optical Tamm state. The FP cavity is built up of a defective sheet sandwiched between two PC reflectors, while the optical Tamm state arises from the configuration of metal–PC heterostructure. After combining these two distinct mechanisms, the proposed heterostructure can exhibit highly localized EM fields around the metal layer. And then, via controlling the input intensity of light, the hybrid Tamm–cavity transmission spectra can undergo remarkable changes. It is also found that the hysteresis effects and nonreciprocal transmission behaviors can be fully formed in the proposed heterostructure, taking effect in the realizing high-performance all-optical switches and diodes. Hopefully, our work could have a positive influence on the development of nonlinear functional photonic devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H. (Wenzhe He); methodology, W.H. (Wei Huang) and L.Y.; software, W.H. (Wenzhe He); validation, W.H. (Wei Huang) and L.Y.; formal analysis, F.W.; investigation, W.H. (Wenzhe He), W.H. (Wei Huang) and L.Y.; resources, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.H. (Wenzhe He), W.H. (Wei Huang) and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, F.W. and Y.C.; visualization, F.W.; supervision, Q.W. and Y.C.; project administration, F.W.; funding acquisition, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Province Key Discipline of China’s 14th five-year plan (Grant No. 2021135).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, F.; Ma, S.J.; Ding, K.; Pendry, J.B. Continuous topological transition from metal to dielectric. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16739–16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Gorlach, M.A.; Alù, A.; Khanikaev, A.B. Topological edge states in acoustic Kagome lattices. New J. Phys. 2017, 19, 055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazbayev, B.; Fleury, R. Quantitative robustness analysis of topological edge modes in C6 and valley-Hall metamaterial waveguides. Nanophotonics 2019, 8, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Jiang, S.J.; Chen, X.D.; Zhu, B.C.; Zhou, L.; Dong, J.W.; Chan, C.T. Experimental realization of photonic topological insulator in a uniaxial metacrystal waveguide. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alù, A.; Engheta, N. Pairing an epsilon-negative slab with a mu-negative slab: Resonance, tunneling and transparency. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2003, 51, 2558–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishige, T.; Caloz, C.; Itoh, T. Experimental demonstration of transparency in the ENG-MNG pair in a CRLH transmission-line implementation. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2005, 46, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoopman, T.; Tayeb, G.; Enoch, S.; Maystre, D.; Gralak, B. Photonic Crystal Lens: From Negative Refraction and Negative Index to Negative Permittivity and Permeability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 073905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, A.L.; Efros, A.L. Electrodynamics of Metallic Photonic Crystals and the Problem of Left-Handed Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 093901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.C.; Povinelli, M.L.; Joannopoulos, J.D. Negative effective permeability in polaritonic photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Chen, H.; Li, H.Q.; Zhang, Y.W. Effective permittivity and permeability of one-dimensional dielectric photonic crystal within a band gap. Chin. Phys. B 2008, 17, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.Q.; Zhang, Y.W.; Chen, H. Optical Tamm States in Dielectric Photonic Crystal Heterostructure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2008, 25, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ruan, J.; He, L.; Panda, A.; Jiang, H.T. Angle-Dispersion-Free Near-Infrared Transparent Bands in One-Dimensional Photonic Hypercrystals. Photonics 2025, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, S.; Gerace, D.; Galli, M.; Sagnes, I.; Braive, R.; Lemaître, A.; Bloch, J.; Bajoni, D. Ultra-low threshold polariton lasing in photonic crystal cavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 111106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Johnson, S.G.; Broderick, L.Z.; Michel, J.; Kimerling, L.C. Integrated photonic structures for light trapping in thin-film Si solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 111110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, K.Y.; Zhao, Y.P.; Zhang, L.; Shang, Z.Q.; Zhou, H.Y.; Diao, C.; Zhou, X.C. Perfect optical absorbers by all-dielectric photonic crystal/metal heterostructures due to optical Tamm state. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.S.; Abdelaleem, A.M.; El-Gamal, A.A.; Amin, M. Fabrication and stabilization of silicon-based photonic crystals with tuned morphology for multi-band optical filtering. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 013108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.H.; Jiang, H.T.; Chen, H. Highly efficient all-optical diode action based on light-tunneling heterostructures. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 7479–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xue, C.H.; Jiang, H.T.; Chen, H. Optical phase conjugation enhancement in one-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystals containing single-negative materials. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2011, 28, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.Q.; Jiang, H.T.; Wang, Z.S.; Chen, H. Optical nonlinearity enhancement in heterostructures with thick metallic film and truncated photonic crystals. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.J.; Jiang, H.T.; Chen, H.; Shi, Y.L. Enhancement of Faraday rotation effect in heterostructures with magneto-optical metals. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 093101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fano, U. Effects of Configuration Interaction on Intensities and Phase Shifts. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.H. Sharp asymmetric line shapes in side-coupled waveguide-cavity systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Khanikaev, A.B.; Adato, R.; Arju, N.; Yanik, A.A.; Altug, H.; Shvets, G. Fano-resonant asymmetric metamaterials for ultrasensitive spectroscopy and identification of molecular monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2011, 11, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.H.; Lei, D.Y.; Li, X.F.; Maier, S.A. Plasmonic Fano resonances in nanohole quadrumers for ultra-sensitive refractive index sensing. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 4705–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xue, W.Q.; Semenova, E.; Yvind, K.; Mork, J. Demonstration of a self-pulsing photonic crystal Fano laser. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.H.; Zhang, F.L.; Fan, Y.C.; Dong, J.J.; Cai, W.Q.; Zhu, W.; Chen, S.; Yang, R.S. Weak coupling between bright and dark resonators with electrical tunability and analysis based on temporal coupled-mode theory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 221905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Liang, J.G.; Yu, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, R.S.; Fan, Y.C.; Wang, G.M.; Cai, T. Silicon-Based Terahertz Meta-Devices for Electrical Modulation of Fano Resonance and Transmission Amplitude. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.C.; He, X.; Zhang, F.L.; Cai, W.Q.; Li, C.; Fu, Q.H.; Sydorchuk, N.V.; Prosvirnin, S.L. Fano-resonant hybrid metamaterial for enhanced nonlinear tunability and hysteresis behavior. Research 2021, 2021, 9754083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Wang, F.F.; Ao, Y.T.; Gao, W.; Yang, H.; Gong, Q.H. Ultralow-power on-chip all-optical Fano diode based on uncoupled nonlinear photonic-crystal nanocavities. J. Opt. 2018, 20, 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Xiao, Y.F.; Zou, C.L.; Jiang, X.F.; Liu, Y.C.; Sun, F.W.; Li, Y.; Gong, Q.H. Experimental controlling of Fano resonance in indirectly coupled whispering-gallery microresonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 021108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotov, V.A.; Rose, M.; Prosvirnin, S.L.; Papasimakis, N.; Zheludev, N.I. Sharp trapped-mode resonances in planar metamaterials with a broken structural symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 147401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Flach, S.; Kivshar, Y.S. Fano resonances in nanoscale structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk’Yanchuk, B.; Zheludev, N.I.; Maier, S.A.; Halas, N.J.; Nordlander, P.; Giessen, H.; Chong, C.T. The Fano resonance in plasmonic nanostructures and metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Khanikaev, A.B.; Shvets, G. Broadband slow light metamaterial based on a double-continuum Fano resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 107403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Yu, Z.; Fan, S.H.; Brongersma, M.L. Optical fano resonance of an individual semiconductor nanostructure. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Al-Naib, I.A.I.; Koch, M.; Zhang, W. Sharp Fano resonances in THz metamaterials. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 6312–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Hu, X.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Chai, Z.; Xie, J.; Gong, Q. Fano-resonance in one-dimensional topological photonic crystal heterostructure. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 8634–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiyang, W.N.; Jiang, P.; Qin, Y.; Mao, S.Q.; Cao, B.; Gui, F.J.; Yang, H.J. Design of a high-Q fiber cavity for omnidirectionally emitting laser with one-dimensional topological photonic crystal heterostructure. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 4176–4187. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Xu, J.; Dong, H.; Dai, X.; Jiang, J.; Qian, S.; Jiang, L. Graphene-based low-threshold and tunable optical bistability in one-dimensional photonic crystal Fano resonance heterostructure at optical communication band. Opt. Express 2020, 27, 34948–34959. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Wang, B.; Yuan, Q.; Fang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Gan, X.; Zhao, J. Fano resonance from a one-dimensional topological photonic crystal. APL Photonics 2021, 6, 086105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Rezaei, B.; Ad, H.P.; Zakerhamidi, M.S. Tunable Fano resonance in coupled topological one-dimensional photonic crystal heterostructure and defective photonic crystal. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 133, 083102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Gao, E.; Li, M.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lia, H. Tunable Fano resonance and optical switching in the one-dimensional topological photonic crystal with graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 133, 213101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manifacier, J.C.; Gasiot, J.; Fillard, J.P. A simple method for the determination of the optical constants n, k and the thickness of a weakly absorbing thin film. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1976, 9, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalora, M.; Bloemer, M.J.; Pethel, A.S.; Dowling, J.P.; Bowden, C.M.; Manka, A.S. Transparent, metallodielectric, one-dimensional, photonic band-gap structures. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 2377–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.