Abstract

Building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) enable the seamless incorporation of solar energy systems into architectural structures. Luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) represent a technology that offers a promising route for semitransparent solar harvesting. In this study, phycocyanin, a bio-derived luminescent material extracted from the extremophilic red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, was used as the emissive layer in thin-film LSCs to achieve a sustainable BIPV system. This material exhibited high transparency, strong red fluorescence, and notable stability under illumination conditions, primarily attributable to its unique pigment–protein structure. Thin-film LSCs incorporating phycocyanin at various weight ratios were fabricated and evaluated under simulated sunlight conditions. These concentrators demonstrated efficient photon collection and maintained stable optical performance during solar exposure. Overall, these findings underscore the potential of phycocyanin derived from C. merolae as an eco-friendly and renewable alternative to conventional organic or synthetic luminophores, which can advance the development of sustainable and efficient LSC systems for next-generation BIPV applications.

1. Introduction

Continual depletion of fossil fuel reserves and growing concerns regarding climate change have intensified the global pursuit of renewable and sustainable energy solutions. Photovoltaic (PV) systems have emerged as one of the most promising solutions because of their ability to directly convert sunlight into electricity without generating harmful emissions. These advancements confirm the economic competitiveness of PV technology and its value in reducing reliance on fossil fuels and mitigating environmental impacts. Nevertheless, conventional PV modules still face several practical challenges, including high installation costs, the requirement for large installation areas, limited architectural adaptability, and end-of-life recycling concerns [1,2,3]. These constraints and angular dependencies hinder the deployment of PVs in space-constrained or densely populated urban environments.

Building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) have been proposed as an effective strategy for addressing the aforementioned challenges. By incorporating solar modules into building rooftops, facades, and windows, BIPVs can reduce land-use requirements, enhance architectural esthetics, and enable on-site power generation in settings with high electrical demand [4,5,6]. Within this framework, luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) have emerged as a particularly promising approach [7,8,9,10]. An LSC is a device that consists of a transparent glass or polymer substrate embedded or coated with luminescent materials that absorb incident sunlight and re-emit it at longer wavelengths. The emitted photons are trapped within a plate as a result of total internal reflection and are guided to the plate’s edges, where attached PV cells convert them into electricity. This architecture reduces the required active PV cell area by replacing it with a low-cost light-collecting plate, resulting in a lightweight, scalable, and architecturally adaptable system. Additionally, LSCs benefit from diffuse light collection, wherein scattered radiation from clouds, haze, or atmospheric conditions can be efficiently absorbed by a luminescent layer, thereby enhancing overall output.

To further improve efficiency, thin-film LSC configurations have been introduced, in which the luminescent material is deposited as a thin coating on a transparent substrate. In this design, absorption and emission occur within the film, whereas the re-emitted photons are largely confined within the transparent plate, thereby reducing reabsorption losses when high-purity optical materials are employed [11,12,13,14]. Despite these advancements, the success of thin-film LSCs primarily depends on the choice of luminescent material. Optimal candidates must exhibit high quantum yield, long-term photostability, and low reabsorption capacity and must be compatible with cost-effective fabrication principles. Although organic dyes and quantum dots have been extensively studied, their practical application remains limited by photodegradation, thermal instability, and high production costs [7,8]. Inorganic phosphors, which are already well established in solid-state lighting, offer distinct advantages for LSCs, including thermal stability, resistance to ultraviolet radiation and moisture, and relatively low cost. In our previous study, we confirmed the potential of inorganic phosphors for use in scalable LSC systems, and we reported stable and high performance in thin-film devices incorporating commercial inorganic phosphors [15]. With the constant advancements in this field, research attention has shifted to alternative luminescent materials that combine functionality with sustainability. While various organic dyes, quantum dots, and inorganic phosphors have been explored as luminophores for LSC applications, increasing concerns related to material toxicity, environmental impact, and resource sustainability have motivated the exploration of alternative bio-derived luminophores. Among these materials, bio-based pigments such as phycocyanin have recently attracted attention in the field of optoelectronics, with reports highlighting their potential for use in PV devices and fluorescence-based applications [16,17,18]. In this context, phycocyanin extracted from Cyanidioschyzon merolae offers a renewable option without toxic heavy metals, with absorption–emission characteristics compatible with LSC operation.

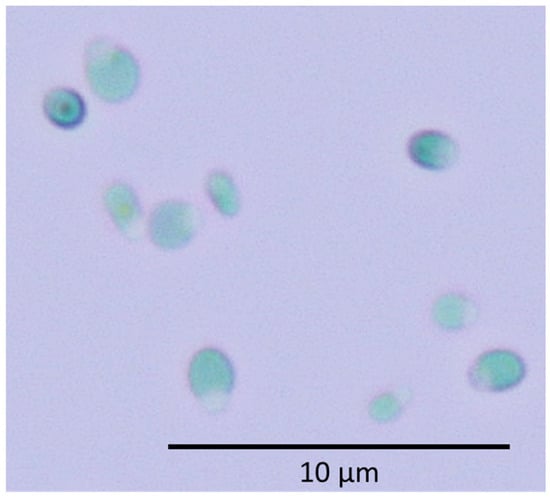

Phycocyanin is a water-soluble pigment–protein complex that captures light for photosynthesis in cyanobacteria, red algae, and cryptophytes, including the red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Morphologically, the cells of C. merolae are oval to club-shaped, measuring 1.5–3.5 µm each, and they reproduce by binary fission (Figure 1). Isolated phycocyanin appears blue, emits strong red fluorescence, and exhibits notable antioxidant activity, making it widely applicable in food, cosmetics, and medicine. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the extraction methods used for Limnospira platensis (syn. Spirulina platensis), the most commonly used species for phycocyanin production, although extraction from other cyanobacteria and red algae has also been reported [16]. C. merolae belongs to the class Cyanidiophyceae, a group of extremophilic unicellular red algae capable of growing under highly acidic (pH 0–5) and high-temperature (35–63 °C) conditions [17]. In addition to its thermotolerance, the C. merolae 10D strain lacks a rigid cell wall [18], a feature that enables rapid and cost-effective phycocyanin extraction by using high concentrations of MgCl2 [19]. According to the literature, phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae remains thermostable at 60 °C, whereas phycocyanin extracted from L. platensis remains stable only up to 45 °C [19,20]. In addition, phycocyanin extracted from L. platensis has been reported to degrade upon exposure to 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light for 36 h [20]. Therefore, several strategies, such as the use of additives, have been proposed to enhance the stability of phycocyanin [21].

Figure 1.

Photograph of Cyanidioschyzon merolae.

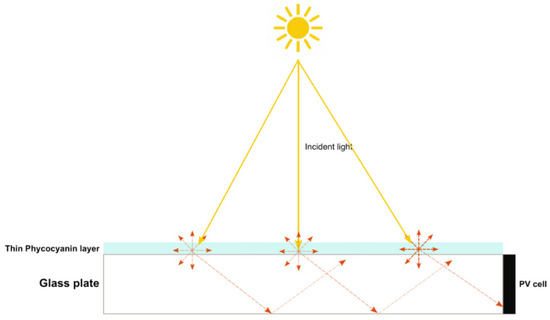

In this study, we used phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae as the luminescent layer in thin-film LSCs for BIPV applications. While previous studies on bio-based luminophores for LSCs have predominantly focused on phycocyanin derived from Spirulina platensis or other cyanobacteria, the utilization of C. merolae-derived PC remains largely unexplored. Notably, C. merolae exhibits unique biological characteristics, including thermotolerance, the absence of a rigid cell wall, and enhanced pigment stability during extraction and processing, which are advantageous for device fabrication. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first report demonstrating the application of C. merolae-derived phycocyanin as a luminescent material in thin-film LSC architectures. Specifically, we examine the light-harvesting ability of PC at different weight ratios under illumination conditions relevant to LSC operation, as illustrated in Figure 2, together with a systematic investigation of emissive-layer placement (top- and bottom-coated configurations) within the LSC structure. Our goal was to determine the feasibility of phycocyanin as a sustainable, bio-derived alternative to conventional luminescent materials and to provide insights into its potential for use in advancing environmentally friendly and efficient LSC technologies.

Figure 2.

Schematic of a thin-film LSC incorporating phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae as the luminescent material.

2. Materials and Methods

Each LSC consisted of four primary components: a transparent light guide, a phycocyanin layer, PV cells, and reflective elements. A borosilicate glass plate (BA270, 50 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm) was used as the transparent light guide. Multicrystalline silicon (mc-Si) cells were laser-cut to dimensions of 50 mm × 5 mm to match the edges of the glass plate. After wire soldering, the cells were found to exhibit an average power conversion efficiency of 12.74% within an AM 1.5G spectrum. Next, they were affixed to the glass plate edges by using optically clear silicone (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), which was cured at room temperature for 48 h to ensure stable optical and mechanical coupling.

Phycocyanin was extracted from C. merolae using a MgCl2-based method as previously reported [19]. Cells were centrifuged at 5000× g for 2 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in twice its volume of 0.75 M MgCl2. After the suspension was incubated in the dark at 40 °C for 2 h, it was centrifuged at 20,000× g for 2 min. Next, the blue supernatant obtained was diluted at a ratio of 1:4 (v/v) with water, and the concentration of phycocyanin was calculated using the following formula [22]:

where absorbance values at 620 nm (A620) and 652 nm (A652) were baseline-corrected by assuming that absorbance values at 470 and 730 nm correspond to isosbestic points with zero absorbance. Using this method, the concentration of the extracted phycocyanin solution was determined to be 1.379 mg/mL Finally, the excitation and emission spectra of phycocyanin were measured using a FluoroMax 4 spectrometer (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere.

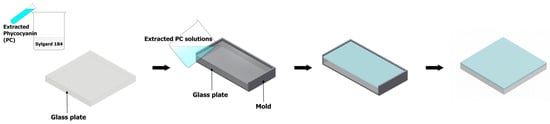

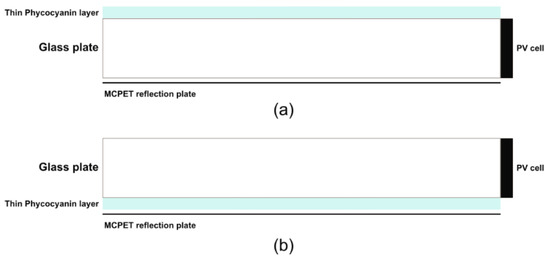

To fabricate thin-film LSCs, the phycocyanin extract was uniformly mixed with optically clear silicone (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) at weight ratios of 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, and 35% through mechanical stirring. Each mixture was then poured into a rectangular aluminum mold with a glass plate at its base, which acted as the substrate. The thickness of the thin phycocyanin layer on the glass plate was controlled by adjusting the depth of the rectangular aluminum mold, which was fixed at 0.65 mm to ensure a uniform film thickness. Next, the films were cured following the manufacturer’s instructions to obtain uniform thin phycocyanin layers. Figure 3 depicts a schematic of the thin-film LSC fabrication process. After casting, the coated glass plates were thermally cured at 60 °C for 90 min to obtain solid and uniform thin phycocyanin layers. In addition to varying the weight ratio of phycocyanin, the relative positions of the thin phycocyanin layer were investigated to examine different LSC structural configurations. Two configurations were fabricated: a configuration with the thin phycocyanin layer coated on the top surface of the glass plate and a configuration with the thin phycocyanin layer positioned beneath the glass plate. These two configurations were achieved using the same fabrication procedures described earlier, ensuring a uniform film thickness and curing conditions for reliable comparison in subsequent analyses. Figure 4 presents a schematic of the LSCs with the thin phycocyanin layer on the top and bottom surface of the glass plate. To further enhance light-harvesting efficiency, reflective elements were incorporated into the LSC design. A microcellular polyethylene terephthalate plate (MCPET) with 95% reflectance was applied to all side and bottom surfaces of the LSCs. The reflectors were used to increase the probability of incident light interacting with the thin phycocyanin layer and redirect the emitted photons toward the PV cells, thereby improving overall device performance. It should be noted that the MCPET and its geometric configuration were kept identical for all LSC configurations and phycocyanin weight ratios investigated in this study. Accordingly, the MCPET provides a fixed waveguiding boundary condition, and the observed performance variations can be primarily attributed to differences in the phycocyanin configuration and loading rather than changes in the waveguide structure.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the thin-film LSC fabrication process.

Figure 4.

Schematic of LSCs with the thin phycocyanin layer on the (a) top surface and (b) bottom surface of the glass plate.

As a final step, the LSCs were tested under simulated solar illumination conditions by using a Sun 2000 solar simulator (Abet Technologies, Milford, CT, USA) operating at AM 1.5G with an intensity of 100 mW cm−2. Additionally, the current–voltage characteristics of the PV cells attached to each LSC were recorded using a Keithley 2400 source meter (Keithley Instruments, Cleveland, OH, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

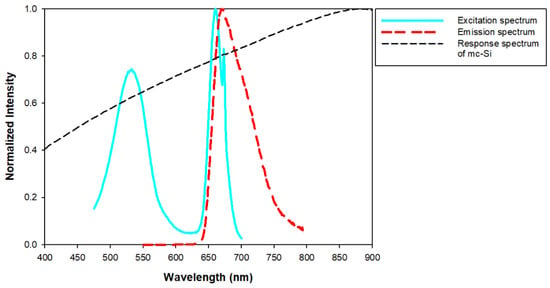

Figure 5 presents the normalized excitation and emission spectra of phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae. The excitation spectrum exhibits two distinct absorption bands centered at approximately 530 and 660 nm, corresponding to the characteristic electronic transitions of bilin chromophores in the phycocyanin protein complex. The emission spectrum exhibits a strong fluorescence peak near 670 nm, with emission extending from approximately 660 to 720 nm. This spectral behavior indicates that the extracted phycocyanin efficiently absorbs incident light in both the green and red regions of the visible spectrum and subsequently re-emits it in the deep-red region with high intensity. A notable feature is the substantial overlap between the phycocyanin emission band and the spectral response of the mc-Si PV cells, as indicated by the dashed curve, suggesting excellent spectral compatibility for PV conversion. This spectral compatibility suggests that phycocyanin can serve as an effective spectral converter or luminescent down-shifting material, enhancing photon utilization in Si-based PV cells. Before evaluating the optical performance of the LSCs, it is important to note that the thin phycocyanin layers were cured at 60 °C for 90 min during fabrication. The thermal stability of phycocyanin is crucial to ensure that its absorption and emission properties are preserved under these conditions. Phycocyanin extracted from Cyanidioschyzon merolae has been reported to exhibit thermotolerant behavior [19], and previous studies have shown that moderate heating does not lead to significant degradation when phycocyanin is embedded in polymer matrices [20,21]. Therefore, the chosen curing temperature represents a balance between effective silicone cross-linking and minimal thermal stress on the pigment, ensuring that the optical properties observed in the subsequent measurements reflect the preserved functionality of the phycocyanin.

Figure 5.

Normalized excitation and emission spectra of phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae.

The optical performance of the fabricated LSCs was evaluated in terms of optical collection efficiency (ηopt), which quantifies the ability of an LSC to capture and guide incident light toward the PV cells positioned along the plate edges. To decouple the optical light-collection behavior from the intrinsic photovoltaic performance, ηopt is defined as the ratio between the power conversion efficiency of the integrated LSC system (ηLSC) and that of the bare photovoltaic cell (ηPV) as follows:

In this definition, ηLSC represents the power conversion efficiency of the photovoltaic cells mounted on the edges of the LSC under AM 1.5G illumination using the same solar simulator, reflecting the overall light-harvesting performance of the LSC module. In contrast, ηPV denotes the efficiency of the same photovoltaic cells measured independently under direct illumination without the LSC, under otherwise identical measurement conditions. Because both ηLSC and ηPV were obtained using the same photovoltaic cells and the same measurement setup, systematic uncertainties associated with absolute calibration and illumination geometry largely cancel out in the ratio defining ηopt. As a result, ηopt primarily reflects the intrinsic optical light-collection and guiding capability of the LSC structure rather than the characteristics of the measurement system. Accordingly, no additional correction factors were applied in the evaluation of ηopt. For each LSC configuration, one device was fabricated and measured.

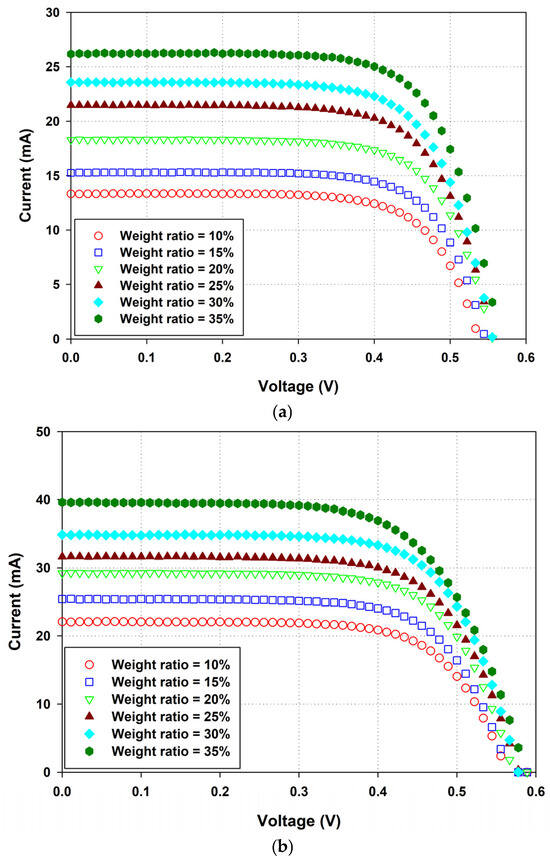

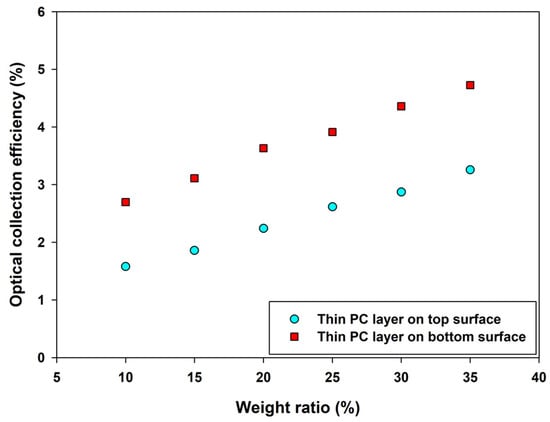

Because of the strong absorption and emission characteristics of phycocyanin, its weight ratio and spatial configuration in LSCs are expected to play a crucial role in determining the value of ηopt. Generally, the molecules of phycocyanin act as luminescent centers that absorb incident sunlight in the green and red regions and subsequently re-emit photons in the deep-red region. These photons are then guided toward the PV cells through total internal reflection. The efficiency of this process depends on the balance between absorption and re-emission. Specifically, an insufficient phycocyanin weight ratio limits photon capture, whereas an excessive phycocyanin weight ratio can cause self-absorption and scattering losses that reduce photon transport through the waveguide. The photovoltaic performance of the fabricated LSCs was first evaluated through their current-voltage (I–V) characteristics. Figure 6a,b show the I–V curves of the LSCs with the thin phycocyanin layer on the top and bottom surfaces of the glass plate across different weight ratios. As the phycocyanin weight ratio increases, a significant enhancement in the short-circuit current (Isc) is observed for both configurations, while the open-circuit voltage (Voc) remains relatively stable. The extracted photovoltaic parameters, including Isc and Voc, were used to determine the optical collection efficiency (ηopt) of the LSCs according to Equation (2). Notably, the devices with the emissive layer on the bottom surface deliver higher current outputs compared to those with the top-surface configuration at identical weight ratios. To further quantify these observations, Figure 7 presents the measured optical collection efficiency (ηopt) of thin-film LSCs incorporating thin phycocyanin layers with varying weight ratios coated either on the top or on the bottom surface of the glass plate. When the weight ratio of phycocyanin was increased, additional photons were absorbed and subsequently re-emitted within the emissive layer, leading to enhanced light capture and guiding through total internal reflection within the glass plate. In both configurations, the value of ηopt steadily increased with increasing phycocyanin weight ratio, indicating that higher PC loading effectively promotes photon absorption, re-emission, and optical coupling. This consistent increase in ηopt suggests that the combined effects of scattering and reabsorption losses remain manageable within the tested weight ratio range, leading to a net improvement in device performance. Furthermore, LSCs with the phycocyanin layer deposited on the bottom surface exhibited consistently higher ηopt values compared with those with the phycocyanin layer deposited on the top surface, regardless of the weight ratio of phycocyanin. This discrepancy can be attributed to lower reabsorption losses and more efficient coupling of re-emitted photons into the glass plate, which enabled a larger fraction of the emitted light to reach the PV cells located along the plate edges. In the bottom-coated configuration, photons emitted toward the glass substrate are more readily trapped by total internal reflection, while surface-related escape-cone losses at the air–glass interface are suppressed. In contrast, top-coated configurations are more susceptible to photon escape before effective waveguiding occurs. Taken together, these findings confirm that optimizing both the weight ratio of phycocyanin and the placement of the emissive layer is crucial for maximizing the efficiency of light harvesting in phycocyanin-based thin-film LSCs. They also confirm the optical suitability of phycocyanin extracted from C. merolae for transparent solar energy conversion systems.

Figure 6.

Current-voltage (I–V) characteristics of LSCs with the thin phycocyanin layer on the (a) top surface and (b) bottom surface of the glass plate.

Figure 7.

Optical collection efficiency of LSCs with the thin phycocyanin layer on the top and bottom surface of the glass plate.

4. Conclusions

In this study, phycocyanin, a bio-derived pigment extracted from the extremophilic red alga C. merolae, was successfully used as a luminescent material in thin-film LSCs, representing a renewable and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional synthetic dyes. This pigment was found to be associated with strong and narrow emission peaks centered around 670 nm, with high spectral compatibility to mc-Si PV cells. Operating as a proof-of-concept investigation, the fabricated LSCs demonstrated systematically enhanced optical collection efficiency (ηopt) with increasing phycocyanin weight ratio, with the bottom-coated configuration exhibiting higher performance compared with the top-coated configuration because of its reduced reabsorption and improved optical coupling. Overall, these findings confirm phycocyanin’s use as a sustainable luminophore for next-generation BIPV technologies and other solar-energy-harvesting platforms. While the reported values are based on single-device measurements for each configuration, the clear and consistent performance trends across the tested concentration range validate the device’s fundamental optical behavior. Detailed spectroscopic characterization of film transmission and absorption, along with an extended statistical analysis to evaluate device-to-device reproducibility, will be addressed in future studies using appropriately scaled samples. In addition, long-term photostability, thermal stability, and environmental durability of phycocyanin-based LSCs under prolonged illumination will be systematically investigated to assess their practical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-P.Y., B.-M.C. and Y.-K.C.; Methodology, S.-P.Y., H.-Y.F. and Y.-K.C.; Software, Y.-W.L.; Validation, Y.-W.L.; Formal analysis, B.-M.C. and Y.-W.L.; Investigation, S.-P.Y., H.-Y.F. and Y.-W.L.; Resources, H.-Y.F. and Y.-K.C.; Data curation, H.-Y.F., B.-M.C. and Y.-W.L.; Writing—original draft, S.-P.Y.; Writing—review & editing, S.-P.Y.; Visualization, B.-M.C. and Y.-K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tsoutsos, T.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gekas, V. Environmental impacts from the solar energy technologies. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaabi, B.; Ghosh, A. Managing photovoltaic waste: Sustainable solutions and global challenges. Sol. Energy 2024, 283, 112985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchelli, S.; Havrysh, V.; Kalinichenko, A.; Suszanowicz, D. Ground-Mounted Photovoltaic and Crop Cultivation: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemisana, D. Building integrated concentrating photovoltaics: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, B.; Esmailzadeh, E.; Dincer, I. Renewable energy options for buildings: Case studies. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P.; Breivik, C.; Røkenes, H.D. Building integrated photovoltaic products: A state-of-the-art review and future research opportunities. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 100, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debije, M.G.; Verbunt, P.P.C. Thirty years of luminescent solar concentrator research: Solar energy for the built environment. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, B.C.; Wilson, L.R.; Richards, B.S. Advanced material concepts for luminescent solar concentrators. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2008, 14, 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Benetti, D.; Ma, D.; Rosei, F. Perovskite quantum dots integrated in large-area luminescent solar concentrators. Nano Energy 2017, 37, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gong, X. Deep-red emitting zinc and aluminium co-doped copper indium sulfide quantum dots for luminescent solar concentrators. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 534, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, G.; Campagnaro, A.; Carturan, S.; Quaranta, A. Dye-doped parylene-based thin film materials: Application to luminescent solar concentrators. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 108, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, T.; Bauer, C.; Dolamic, I.; Brühwiler, D. Spectral-based analysis of thin film luminescent solar concentrators. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffini, G.; Levi, M.; Turri, S. Thin-film luminescent solar concentrators: A device study towards rational design. Renew. Energy 2015, 78, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisfeld, R.; Eyal, M.; Chernyak, V.; Zusman, R. Luminescent solar concentrators based on thin films of polymethylmethacrylate on a polymethylmethacrylate support. Sol. Energy Mater. 1988, 17, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.-P.; Chen, B.-M.; Tseng, W.-L. Thin-film luminescent solar concentrators using inorganic phosphors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 2290–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, N.T. Production of phycocyanin—A pigment with applications in biology, biotechnology, foods and medicine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Etten, J.; Cho, C.H.; Yoon, H.S.; Bhattacharya, D. Extremophilic red algae as models for understanding adaptation to hostile environments and the evolution of eukaryotic life on the early earth. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 134, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagishima, S.-Y.; Tanaka, K. The unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae—The simplest model of a photosynthetic eukaryote. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, C.; Murakami, M.; Niwa, A.; Takeya, M.; Osanai, T. Efficient extraction and preservation of thermotolerant phycocyanins from red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 131, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-L.; Wang, G.-H.; Xiang, W.-Z.; Li, T.; He, H. Stability and antioxidant activity of food-grade phycocyanin isolated from Spirulina platensis. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 2349–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh-Lo, M.; Castillo, G.; Ochoa-Becerra, M.A.; Mojica, L. Phycocyanin and phycoerythrin: Strategies to improve production yield and chemical stability. Algal Res. 2019, 42, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Bogorad, L. Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue-green alga. J. Cell Biol. 1973, 58, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.