Abstract

Traditional herbal prescriptions composed of multiple botanicals remain central to ethnopharmacological practice; however, their chemical basis and classification remain poorly understood. Non-volatile compound analyses of herbal medicines are well established, but comparative studies focusing on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) across multi-herbal prescriptions are scarce. To enhance the chemical understanding of traditional formulations and clarify prescription-level characteristics, this study applied headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-SPME–GC–MS) to characterize VOC-based chemical signatures in 30 prescriptions composed of 76 herbal ingredients. Multivariate analyses such as principal component analysis, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) enabled systematic differentiation of various prescriptions and identified 25 discriminant VOCs, 9 of which were common among multiple therapeutic categories. These shared compounds, such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) and 4H-pyran-4-one derivatives, reflect recurrent chemical patterns associated with broad-spectrum applications, whereas category-specific volatiles (including isopsoralen, senkyunolide, and fenipentol) delineated therapeutic boundaries, even among prescriptions with overlapping botanicals. Capturing both shared and distinct volatile signatures clarified ambiguous boundaries between categories such as cold, inflammation, or diabetes versus kidney disorder prescriptions, thereby linking chemical patterns with ethnopharmacological indications. Together, these findings highlight VOC profiling as a valuable diagnostic and interpretive tool that bridges traditional categorization systems with modern chemical analysis, offering a robust framework for future pharmacological and mechanistic investigations. Such an approach not only substantiates traditional categorization but also provides a practical basis for quality control and pharmacological evaluation of multi-herbal formulations.

1. Introduction

Natural products have played crucial roles in human health for centuries, and the vast array of chemical compounds present in natural products offers a rich platform for drug discovery and development [1,2]. The discovery of active plant compounds such as paclitaxel [3], hesperidin [4], silymarin [5], quercetin [6], various terpenoids [7,8], and flavonoids [9] has provided a scientific basis for understanding the medicinal basis of these natural products. Previous findings have also highlighted the pivotal roles of natural bioactive substances in pharmaceutical innovation [10].

Traditional herbal prescriptions consist of complex mixtures of natural products whose therapeutic effects have been recognized through long-standing empirical use [11].

These formulations contain numerous constituents that act together to produce the overall therapeutic outcome, yet the mechanistic basis of their synergistic and complementary actions remains poorly defined. Their clinical applications are often broad and not restricted to a single disease entity, reflecting flexible, experience-based practice rather than rigid disease-specific frameworks. This empirical and holistic use of multi-herb prescriptions both preserves accumulated traditional knowledge and complicates efforts to systematically validate and classify their therapeutic indications [12,13,14]. Consequently, modern pharmacology has emphasized the need for rigorous, mechanism-oriented studies to substantiate traditional claims and to clarify how multiple constituents interact to generate therapeutic effects.

In traditional East Asian medicine, herbal prescriptions are guided by the concept of ‘qi’, which represents the dynamic physiological flow that maintains internal balance. The regulation of qi is central to therapeutic design, since imbalances in qi, such as deficiency, stagnation, or reversal, manifest as patterns of disease that require corresponding treatments [15]. For example, certain medicinal herbs are specifically noted for addressing patterns of qi imbalance; Hypericum sampsonii Hance, a prominent herb, is traditionally prescribed for conditions like anxiety disorders rooted in Liver-qi stagnation [16]. Prescriptions are therefore categorized not only by their pharmacological actions but also by their energetic orientations, such as warming or cooling, tonifying or dispersing, which describe how they modulate the movement of qi within the body. From a modern phytochemical perspective, these traditional classifications may correspond to variations in the chemical nature of volatile compounds. For example, warming prescriptions often contain higher proportions of terpenes and ketones that promote circulation and metabolic stimulation [17], whereas cooling or detoxifying prescriptions are enriched in oxygenated compounds, phenolics, or lactones that exert sedative or anti-inflammatory effects [18,19]. This conceptual bridge suggests that the traditional notion of qi regulation can, at least in part, be reflected through the volatility, polarity, and bioactivity of key constituents.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), primarily extracted from plants, possess a variety of important pharmacological properties. For instance, terpenes, which are responsible for the aroma and flavor of plants, exhibit numerous pharmacological actions, including anti-inflammatory [20], antimicrobial [21], and sedative effects [22,23]. In traditional herbal medicine, terpenes derived from medicinal plants can affect the nervous system, providing therapeutic benefits such as stress relief [24]. Moreover, due to their volatility, these compounds are rapidly absorbed and distributed in the body, enabling a quick onset of action and enhancing the overall effectiveness of herbal treatments [25,26].

While VOCs are known to be crucial components of natural products, their specific roles within complex traditional prescriptions, which combine multiple herbs for various therapeutic applications, remain underexplored. Previous research has suggested that VOCs are likely to contribute to the overall therapeutic effect through complex interactions among various herbs [27], but the underlying mechanisms have not been clearly elucidated.

Therefore, this study focuses on the volatile components present in traditional herbal prescriptions. We hypothesize that these volatile components are crucial for understanding the therapeutic impact of herbal mixtures, as they likely contribute to the overall effects through their interactions within the complex herbal formulations. To test this hypothesis, we sought to gain a deeper understanding of their contribution to the efficacy of the prescriptions by categorizing and analyzing the VOCs from various herbal formulas based on their intended medicinal applications.

This research aims to assess the synergy between these compounds and the overall effectiveness of the prescriptions by analyzing differences in their therapeutic effects. Ultimately, our findings are expected to highlight the importance of VOCs in traditional medicines, thereby enhancing the precision and effectiveness of herbal treatments. This would underscore the importance of studying VOCs to optimize and better understand the benefits of natural product remedies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herbal Medicine Prescriptions

To analyze the volatile components, we selected 30 different traditional herbal prescriptions that were categorized according to their therapeutic applications, including cold, inflammation, pain, women’s diseases, fatigue, diabetes, respiratory disorders, kidney disorders, digestive system diseases, muscle relaxation, and cognitive disorder enhancement (Table 1). The 30 prescriptions spanned a wide clinical spectrum, from acute conditions such as fever, sore throat, and cold (e.g., Paedoksan, PDS; Cheonghwabo Eumtang, CHBE; Socheongryongtang, SCRT) to chronic or systemic disorders such as diabetes and kidney dysfunction (e.g., Ockcheonhwan, OCH; Yukmijihwang Tang, YMJH; Injin Oryeongsan, IOS), as well as women’s health (Samultang, SMT; Sipjeon Daebotang, SDBT) and digestive support (Ijungtang, IJT; Pyeongwisan, PWS; Banhasasimtang, BHST). All dried extract samples were provided by Hanpoong Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Jeonju, Republic of Korea) as standardized decocted extracts, manufactured using controlled decoction, concentration, and drying procedures. Some prescriptions (e.g., Gamisinki Hwan, GSH; Cheongsangbohahwan, CSBH; Ockcheonhwan, OCH; Gagam Palmihwan, GPMH) were also available as pills, which were analyzed in parallel with their corresponding dried extracts to evaluate formulation-dependent differences in VOC compositions. The representative constituent herbs (e.g., Angelica gigas, Panax ginseng, or Scutellaria baicalensis) and clinical indications of each prescription are summarized in Supplementary Table S1, and the specific components used are shown in Table S2.

Table 1.

Overview of the 30 traditional herbal prescriptions analyzed.

2.2. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction–Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS) Analysis

Volatile components were analyzed using via automated headspace solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS). Each dried extract sample, weighing 1 g, was transferred to a 20 mL headspace vial for analysis. Three independent replicates were prepared and analyzed for each prescription. Samples were extracted using a CTC PAL RTC system for high-throughput SPME analysis (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland), following an optimized method. Briefly, samples in headspace vials were pre-equilibrated at 120 °C for 10 min at 300 rotations/min and extracted for 20 min under the same conditions. We used 50/30 μm divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDM) fiber (Agilent J&W, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to prepare SPME extracts. After extraction, the SPME fiber was immediately inserted into the injection port of a gas chromatography (GC)–mass spectrometry (MS) instrument for thermal desorption at 220 °C for 0.2 min. The GC cycle time was 104 min.

We employed an Agilent 8890 GC system equipped with an Agilent DB-5 column (60 m, 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and connected with an Agilent 7000D triple-quadrupole MS system. The injection was conducted in split mode (50:1) with an inlet temperature of 230 °C and a flow rate of 1 mL/min, using helium as the carrier gas in the GC system. The oven temperature was maintained at 60 °C for 3 min, increased to 300 °C at a rate of 2.5 °C/min, and held at 300 °C for 5 min, whereas the transfer line temperature was maintained at 230 °C. The MS system featured an acquisition delay time of 3.5 min, with source and quadrupole temperatures set at 230 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Electron-impact ionization was tuned to 70 eV with a scan mode ranging from 40–600 mass: charge ratio. Compounds analyzed via GC–MS were tentatively identified using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) MS Search 2.2 library. Retention indices were not experimentally determined in this study; therefore, all compound identities were interpreted exclusively at the EI-MS library matching level. Also, all percentage values reported were calculated from total ion chromatogram (TIC) peak areas.

2.3. GC-MS Data Processing and Multivariate Analysis

Agilent GC-MS data files (.d) of all samples were converted to .mzml format, using the MSConvert tool of the ProteoWizard software (3.0.25168-91d1203) suite. For multivariate analysis, we performed spectral deconvolution of the GC–MS data and a molecular-library search following the workflow described at https://gnps.ucsd.edu (accessed on 18 October 2025) [28]. Before the analysis, normalization was performed using Pareto scaling to account for differences among the samples in all models and avoid chemical noise. Unsupervised exploratory analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) with SIMCA-P software (version 18.0.1, Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden), were conducted to identify inherent clustering patterns within the dataset. Potential outliers were assessed using Hotelling’s T2 test to detect extreme variations in the dataset. Furthermore, distance-to-the-model (DModX) analysis was applied to ensure model robustness and detect samples deviating significantly from the main distribution. Following PCA, supervised analysis was performed using orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Data filtering was performed based on median intensity values, followed by normalization and Pareto scaling. Model robustness and potential overfitting were assessed using permutation tests with 100 iterations. Model performance was evaluated using R2Y (goodness-of-fit) and Q2 (goodness-of-prediction) parameters, with Q2 values greater than 0.5 indicating good predictive ability. In addition, the statistical validity of the supervised OPLS-DA and PLS-DA models was assessed using CV-ANOVA, and all models yielded p-values below 0.05, confirming that the observed class discrimination was statistically significant rather than due to random variation. Discriminant variables and potential biomarkers were identified based on variable importance in projection (VIP) values in combination with S-plot analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Herbal Medicines

To maximize VOC recovery and analytical breadth, we compared three SPME fibers, i.e., DVB/CAR/PDMS (50/30 µm), PDMS/DVB (65 µm), and PDMS (100 µm). The DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber yielded the highest number of detected compounds and the largest peak areas and was, therefore, selected for subsequent analyses. We then evaluated incubation temperatures (80, 100, and 120 °C) and extraction durations (20 and 40 min) to optimize the extraction conditions. Extraction efficiency increased with temperature, and 120 °C for 20 min provided the best balance of signal intensity, compound coverage, and throughput. These parameters were used in all subsequent analyses.

3.2. Identification of VOCs via HS-SPME-GC-MS Analysis

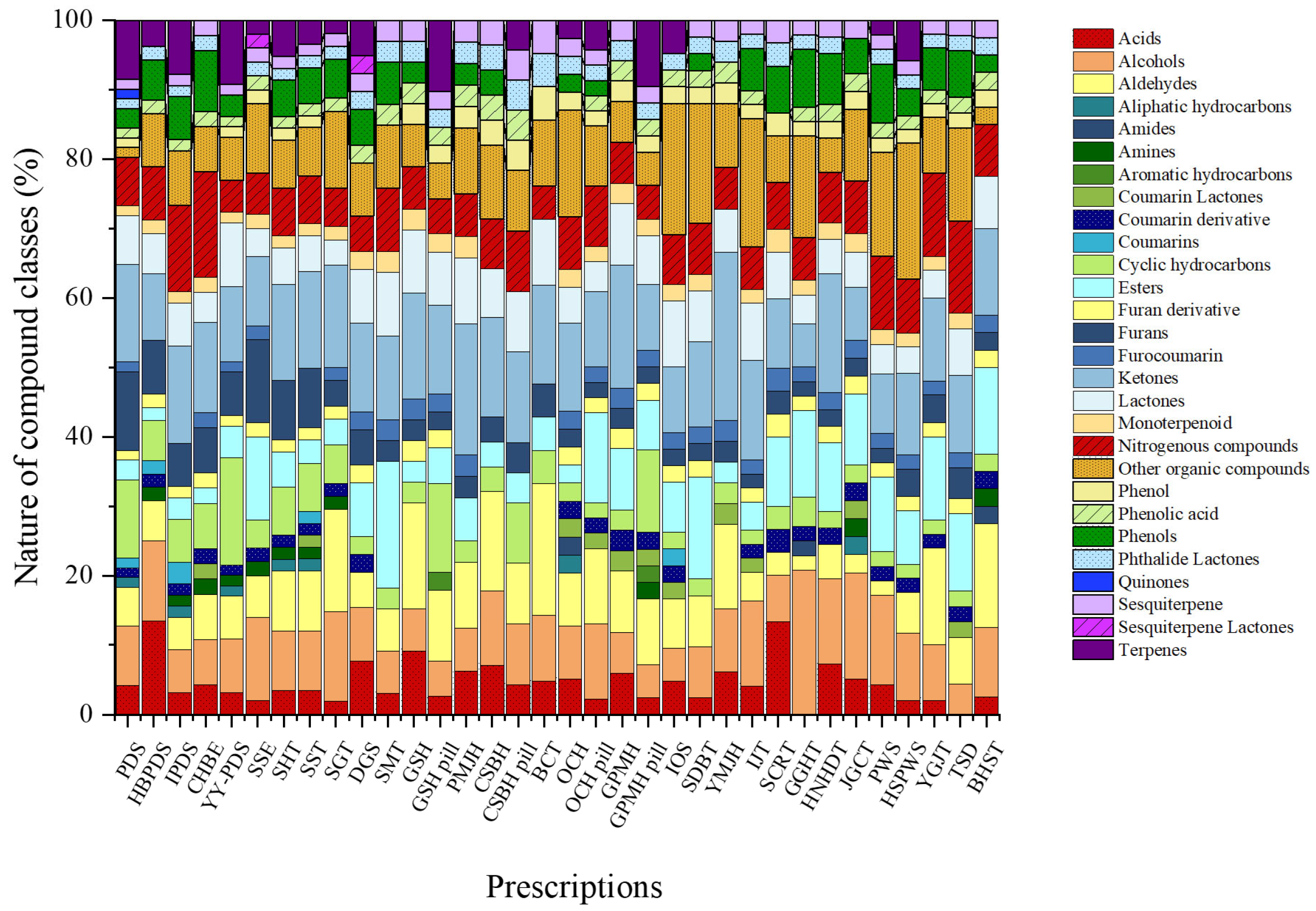

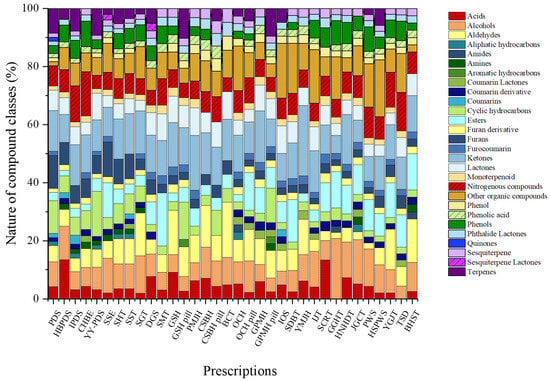

The total ion chromatograms (TICs) of all herbal medicines from the different prescriptions studied are shown in Figure S1. We used HS-SPME-GC-MS to investigate the VOCs in herbal medicine prescriptions and summarized the identified VOCs. Detailed information on the complete set of VOCs detected across all prescriptions is presented in Table S3. A total of 321 volatile compounds were annotated across all prescriptions based on library matching. These annotations reflect tentative identifications and were used to construct the comparative VOC dataset. The VOCs were classified into aldehydes, alcohols, acids, ketones, furans, furan derivatives, phenols, phenolic acids, esters, nitrogenous compounds, lactones, phthalide lactones, aliphatic hydrocarbons, cyclic hydrocarbons, monoterpenoids, terpenes, sesquiterpenes, coumarin derivatives, furocoumarins, quinones, and other organic compounds. Across the individual prescriptions, the relative contributions of chemical classes ranged from 1.4% to 41.7%.

The relative contributions of individual chemical classes within the total VOC composition varied across prescriptions, reflecting distinct compositional characteristics (Figure 1). Paedoksan (PDS) was primarily composed of ketones (14.1%), cyclic hydrocarbons (11.3%), and furans (11.3%), with terpenes contributing 8.5%. Hyungbang Paedoksan (HBPDS) was characterized by a high proportion of acids (13.5%), followed by alcohols (11.5%) and ketones (9.6%). In IPDS, ketones represented the most abundant class (14.1%), together with notable contributions from nitrogenous compounds (12.5%) and terpenes (7.8%). Chunghyulbohyul-eum (CHBE) showed relatively high levels of nitrogenous compounds (15.2%) and ketones (13.0%), accompanied by phenols (8.7%) and alcohols (6.5%). Yeongyopaedoksan (YY-PDS) exhibited a mixed profile dominated by cyclic hydrocarbons (15.4%), followed by ketones (10.8%), terpenes (9.2%), and lactones (9.2%).

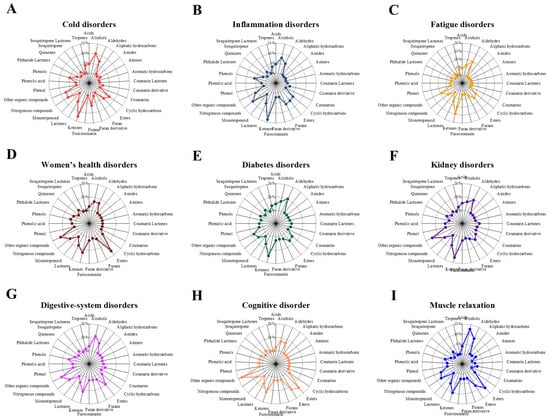

Figure 1.

Comparative radar plots of volatile organic compound (VOC) profiles across different herbal medicine prescriptions.

Among prescriptions associated with warming and dispersing functions, Samsoeum (SSE) was enriched in esters and furans (each 12.0%), together with alcohols (12.0%) and other organic compounds (10.0%). Samhwangtang (SHT) and Sosiho-tang (SST) both displayed ketones as the most abundant class (13.8%), with comparable contributions from aldehydes, alcohols, and furans (each approximately 8–9%). Seunggal-tang (SGT) was distinguished by elevated proportions of ketones (14.8%) and aldehydes (14.8%), along with alcohols (13.0%). Dangguisu-san (DGS) was characterized by ketones (12.8%) and acids (7.7%), while Samultang (SMT) showed a distinct enrichment of esters (18.2%) and ketones (12.1%), with moderate contributions from other organic and nitrogenous compounds.

Clear formulation-dependent differences were observed in prescriptions prepared in both dried extract and pill forms. In Gamisinki-hwan (GSH), the dried extract was dominated by aldehydes and ketones (each 15.2%), whereas the pill formulation exhibited higher relative proportions of cyclic hydrocarbons (12.8%), ketones (12.8%), and terpenes (10.3%). Palmijihwang-hwan (PMJH) was consistently ketone-rich (18.8%), with aldehydes, other organic compounds, and lactones each accounting for approximately 9%. For Cheongsangboha-hwan (CSBH), the dried form was characterized by aldehydes and ketones (each 14.3%), while the pill form shifted toward ketone predominance (13.0%). Baekchul-tang (BCT) showed a markedly aldehyde-dominant profile (41.7%), followed by ketones (24.6%). In Ocheuksan (OCH), the dried extract was co-dominated by ketones and other organic compounds (each ~17%), whereas the pill form showed increased proportions of esters and alcohols. Gagam Palmihwan (GPMH) also exhibited formulation-dependent variation, with ketones predominating in the dried extract (17.6%) and a more evenly distributed profile in the pill formulation.

Among single-form prescriptions, Insamyangyeong-tang (IOS) was dominated by other organic compounds (19.0%) and lactones (9.5%), whereas Samhwangbaekchul-tang (SDBT) showed high proportions of other organic compounds (17.1%) and esters (14.6%). Yukmijihwang-hwan (YMJH) was characterized by a ketone-rich composition (24.2%), with aldehydes contributing 12.1%. Ijintang (IJT) exhibited substantial levels of other organic compounds (18.4%), ketones (14.3%), and alcohols (12.2%). Socheongryong-tang (SCRT) was distinguished by acids (13.3%) and ketones (10.0%), while Gunggwihyanggi-tang (GGHT) showed relatively high proportions of alcohols (20.8%) and other organic compounds (14.6%). Hwangnyeonhaedok-tang (HNHDT) was dominated by ketones (17.1%), and Jakyakgamcho-tang (JGCT) was enriched in alcohols (15.4%) and esters (10.3%). Pyeongwi-san (PWS) and Hyangsapyeongwi-san (HSPWS) both showed substantial contributions from other organic compounds and alcohols. Finally, Yukgunja-tang (YGJT) was characterized by aldehydes (14.0%) and ketones (12.0%), Takrisodogeum (TSD) by other organic and nitrogenous compounds (each 13.3%), and Banha-sasim-tang (BHST) by aldehydes (15.0%), esters (12.5%), and ketones (12.5%).

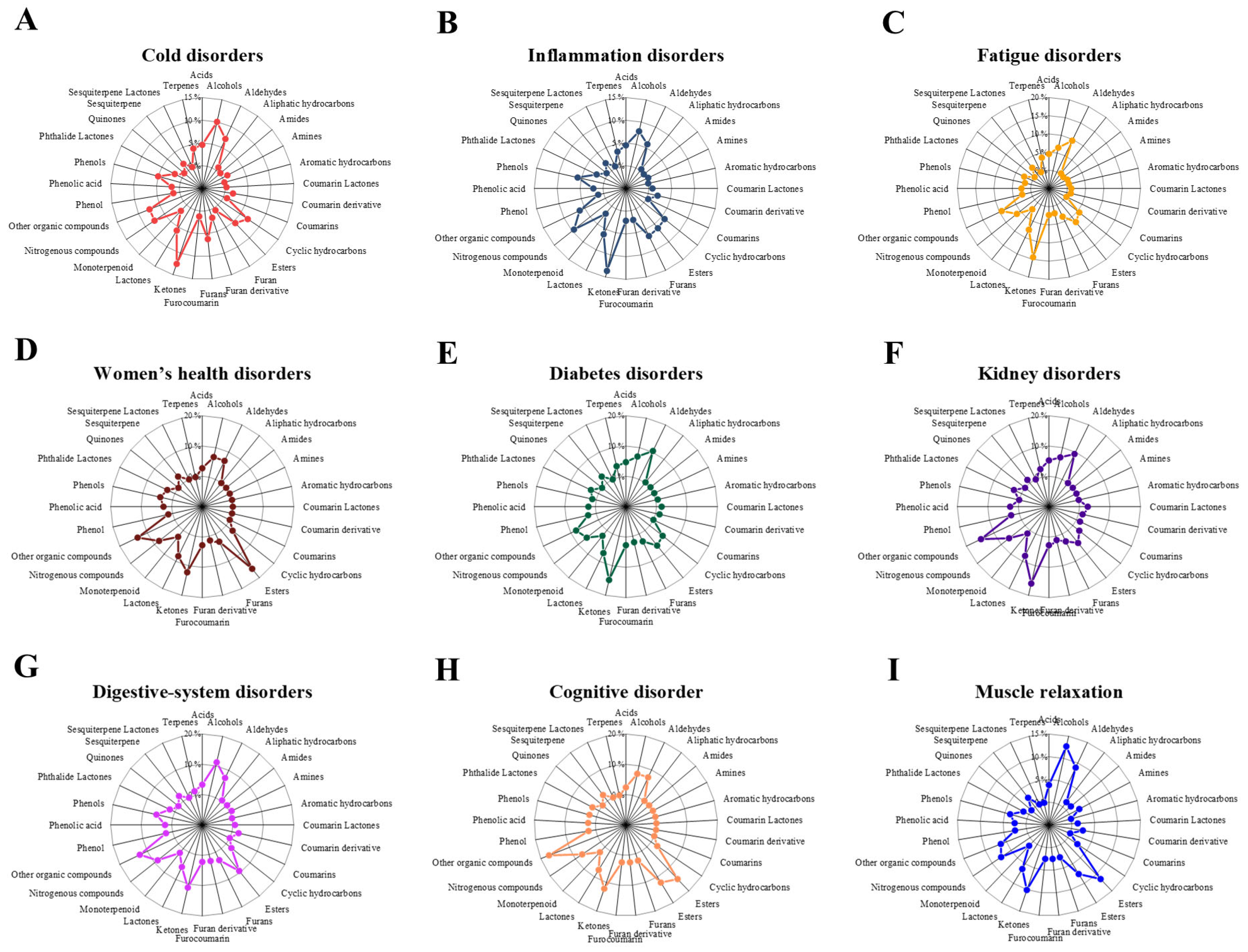

At the therapeutic-group level, the proportional distributions of VOC classes revealed clear usage-specific patterns (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radar plots show the average proportional distribution of volatile organic compound (VOC) classes across nine therapeutic categories. Panels represent (A) Cold disorders, (B) Inflammation disorders, (C) Fatigue disorders, (D) Women’s diseases disorders, (E) Diabetes disorders, (F) Kidney disorders, (G) Digestive-system disorders, (H) cognitive disorder, and (I) Muscle relaxation. Each category displays a distinct VOC composition pattern, reflecting category-dependent chemical characteristics of traditional herbal prescriptions.

In cold disorder prescriptions, the VOC profile was dominated by ketones (12.5%), followed by alcohols (10.0%), nitrogenous compounds (7.6%), and aldehydes (7.0%).Inflammation disorder prescriptions similarly showed a predominance of ketones (13.6%), with substantial contributions from nitrogenous compounds (9.5%), alcohols (7.9%), and furans (6.6%). In fatigue disorder prescriptions, ketones (14.4%) remained the most abundant class, followed by aldehydes (9.6%), other organic compounds (9.3%), and lactones (7.6%), indicating a shift toward oxygenated volatiles. Women’s health disorder prescriptions were characterized by a distinct enrichment of esters (16.2%) and other organic compounds (13.5%), together with notable proportions of ketones (12.2%) and lactones (8.1%).

In diabetes disorder prescriptions, ketones (14.8%) and aldehydes (10.4%) were the dominant classes, followed by other organic compounds (8.1%) and alcohols (7.0%). Kidney disorder prescriptions exhibited high proportions of ketones (16.0%) and other organic compounds (14.7%), with additional contributions from aldehydes (9.3%) and lactones (8.0%). Digestive disorder prescriptions were enriched in other organic compounds (12.7%), alongside comparable contributions from alcohols (11.2%) and ketones (11.2%), followed by esters (9.4%). Finally, cognitive disorder prescriptions showed the highest relative contribution of other organic compounds (17.1%), together with substantial proportions of esters (14.6%), ketones (12.2%), and alcohols and aldehydes (each 7.3%), whereas muscle relaxation prescriptions were dominated by alcohols (12.7%) and esters (11.4%), followed by ketones (10.1%) and aldehydes (8.9%). Overall, these quantitative differences demonstrate that although the same major VOC classes recur across usage groups, their relative dominance varies systematically according to therapeutic classification.

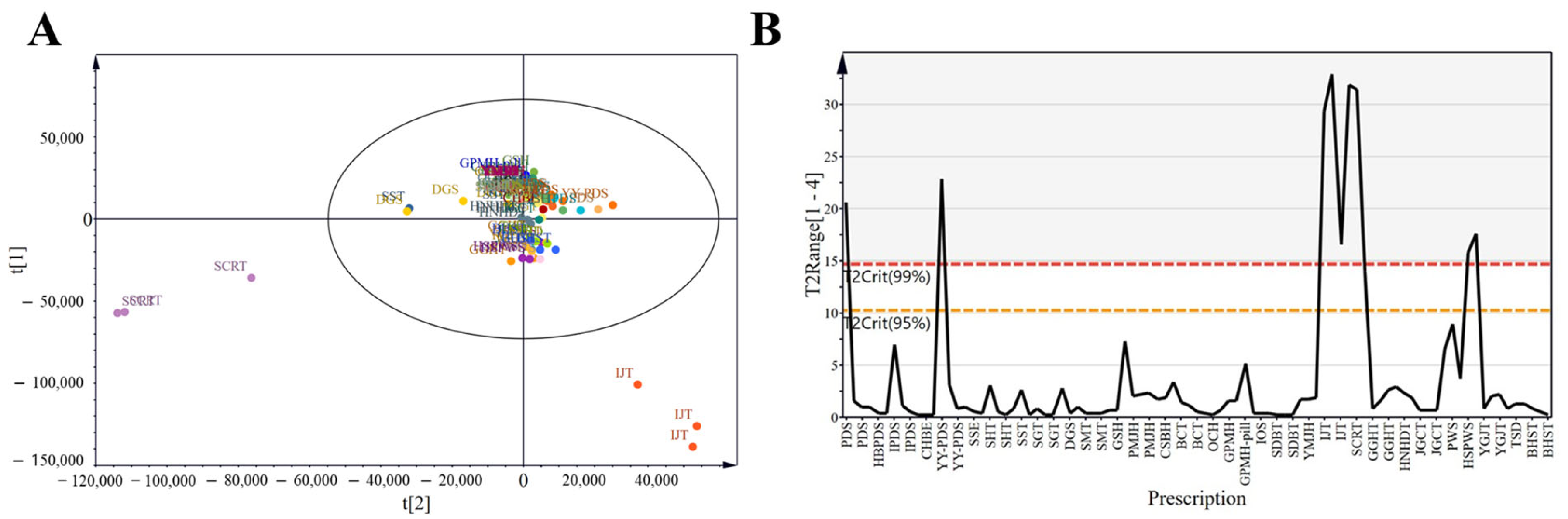

3.3. Results of Multivariate Data Analysis

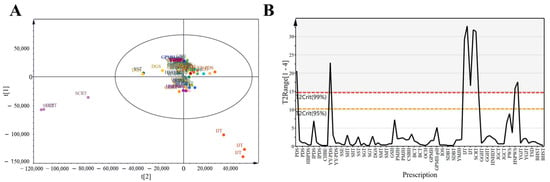

PCA simplifies complex datasets by identifying principal components that explain the variance across observations, facilitating pattern recognition among VOCs. To obtain a general overview of the data distribution, we applied exploratory PCA to the data for all 30 prescriptions (Figure 3A). Samples with strong correlations clustered together, which reinforced the correlation analysis results. All samples were Pareto scaled before analysis. Despite some clustering, considerable overlap, and proximity among prescriptions, limited complete differentiation. In Figure 3B, the red dashed line represents the 99% confidence interval for Hotelling’s T2 (T2Crit 99%), and the yellow dashed line indicates the 95% confidence interval (T2Crit 95%). Prescriptions located outside the red line were identified as outliers, whereas those within the yellow line indicated excellent model fit. For instance, IJT and SCRT exceeded the red line, suggesting relatively high heterogeneity compared with the other prescriptions.

Figure 3.

Score plots of herbal medicine prescriptions. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) score plot of all groups based on four components: R2X [1] = 0.18, R2X [2] = 0.102, cumulative R2X = 0.44, cumulative Q2 = 0.22. The ellipse represents Hotelling’s T2 at the 95% confidence level. (B) Hotelling’s T2 plot, representing a combination of all scores (t) across components.

To gain further insights, we constructed partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and OPLS-DA models to correlate VOC contents measured by HS-SPME-GC-MS with sample categories (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). The sample size was 90, with X variables representing all 30 prescriptions and Y variables representing 11 disease-related usage categories (e.g., cold, inflammation, and pain).

The cross-validation metrics of all prescription models (accuracy, R2, and Q2 > 0.5) confirmed their predictive reliability (Figure S2). Classification based on prescriptions demonstrated clear separation for most therapeutic categories; however, pain- and respiratory-related prescriptions were not distinctly separated, unlike the other groups. Specifically, respiratory-related prescriptions (CSBH, BCT, and SCRT) showed extensive overlap with other groups, and their limited sample sizes further constrained reliable classifications. Therefore, the respiratory disorders category was excluded from subsequent disease-specific analyses, which focused on prescriptions exhibiting clear VOC-based differentiation.

To further illustrate these findings, Table 2 summarizes the distribution patterns within the selected VOC marker set for marker-level normalization. The values in Table 2 do not represent proportions relative to the total VOC content. Instead, they reflect the relative contribution of each marker within the marker set of a given prescription. Table 3 presents the comparative abundance patterns across therapeutic categories, showing which VOCs were enriched or depleted in specific use groups. Together, these VOC markers provide a chemical basis for distinguishing prescriptions and interpreting their category-level characteristics.

Table 2.

Quantitative distribution of marker volatile organic compounds across 30 types of prescription categories.

Table 3.

Compound-level summary of volatile markers linked to prescription categories.

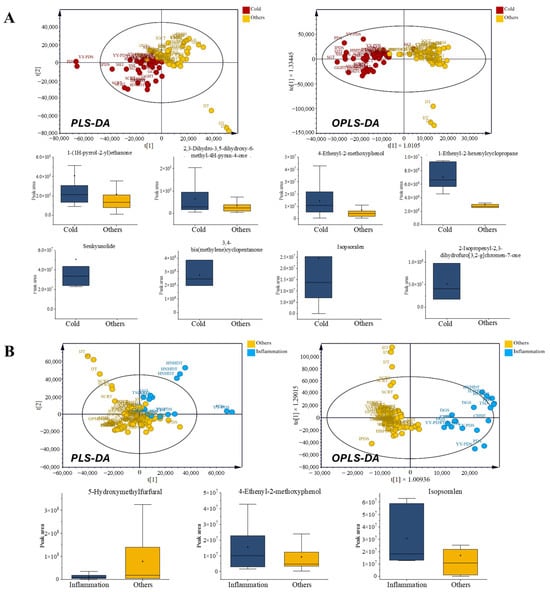

3.4. Acute Condition-Related Prescriptions (Cold and Inflammation)

3.4.1. Cold-Related Prescriptions

Cold prescriptions (PDS, HBPDS, IPDS, CHBE, YY-PDS, SSE, SHT, SST, SGT, BCT, SCRT, GGHT, and HNHDT) were characterized by higher levels of several discriminant VOCs, including ketones such as 1-(1H-pyrrol-2-yl)ethan-1-one and cyclopentanone (3,4-bis(methylene)cyclopentanone), pyranones such as 4H-pyran-4-one derivatives, and phenolic volatiles exemplified by 4-ethenyl-2-methoxyphenol, a compound widely reported for its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [29]. Additional enrichment of senkyunolide [30], a phthalide lactone associated with analgesic and vasorelaxant activities [31], that is, VOCs that improve respiratory disorder’s function, supports its relevance as a discriminant volatile feature in cold-related prescriptions. These tentatively annotated volatiles collectively to the differentiated cold-related prescriptions from other categories in the OPLS-DA model (Figure 4A). Coumarin-type metabolites such as 2-isopropenyl-2,3-dihydrofuro [3,2-g] chromen-7-one and isopsoralen, both documented for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects [32], further contributed to their distinctive chemical profiles. The cyclic hydrocarbon cyclopropane 1-ethenyl-2-hexenyl- was also enriched, supporting a complex fingerprint consistent with the traditional application of cold prescriptions under acute febrile and respiratory conditions.

3.4.2. Inflammation-Related Prescriptions

Inflammation-related prescriptions (PDS, CHBE, DGS, HNHDT, and TSD) shared this general phenolic- and furan-rich background, but they were distinguished by stronger abundances of 4-ethenyl-2-methoxyphenol and furocoumarins (such as isopsoralen), together with consistent 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) levels that were comparatively reduced, a characteristic of inflammation (Figure 4B). Phenolic volatiles, such as 4-ethenyl-2-methoxyphenol, have been documented to have antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, supporting their prominence in inflammation prescriptions [33,34,35]. Notably, both categories included Glycyrrhiza uralensis and Saposhnikovia divaricata as overlapping components. However, their volatile profiles diverged markedly, supporting the view that prescription-level interactions, rather than individual herbs, determine chemical identity. In contrast, Angelica dahurica and Platycodon grandiflorus, which are more frequently used in cold prescriptions, may contribute additional pyranone- and ketone-related volatiles, whereas inflammation prescriptions more consistently incorporate Cnidium officinale, which is traditionally associated with anti-inflammatory activity [36]. These compositional differences highlight the distinct volatile patterns of cold and inflammation prescriptions when compared with those in other categories, even with shared botanicals. The differentiation between cold- and inflammation-related prescriptions emerges from the emergent volatile pattern of multi-herbal prescriptions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for acute symptoms. (A) Cold-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Inflammation-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Figure 4.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for acute symptoms. (A) Cold-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Inflammation-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

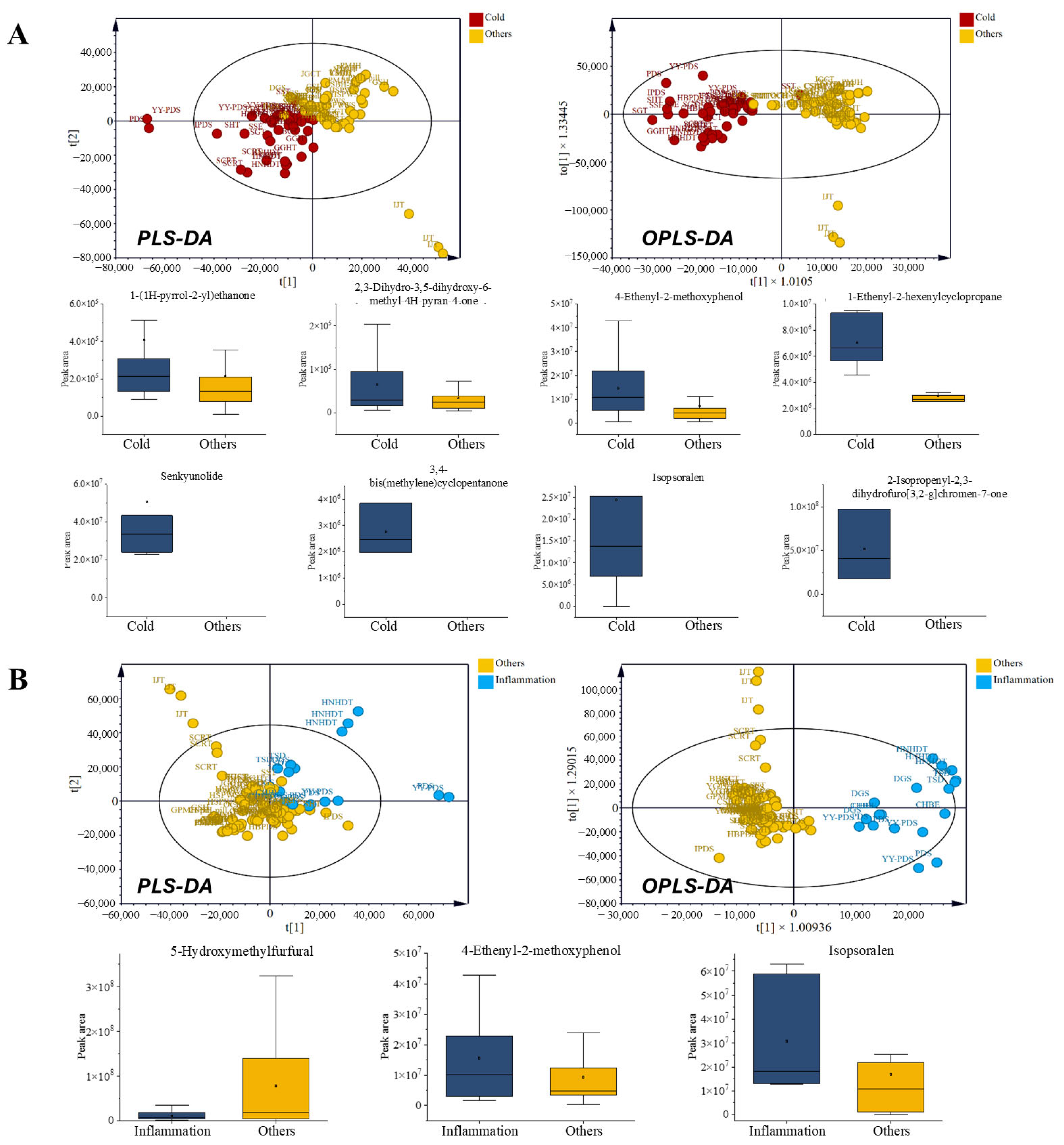

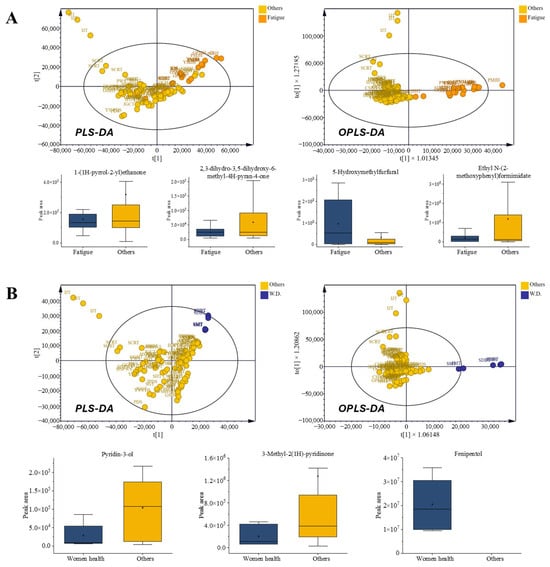

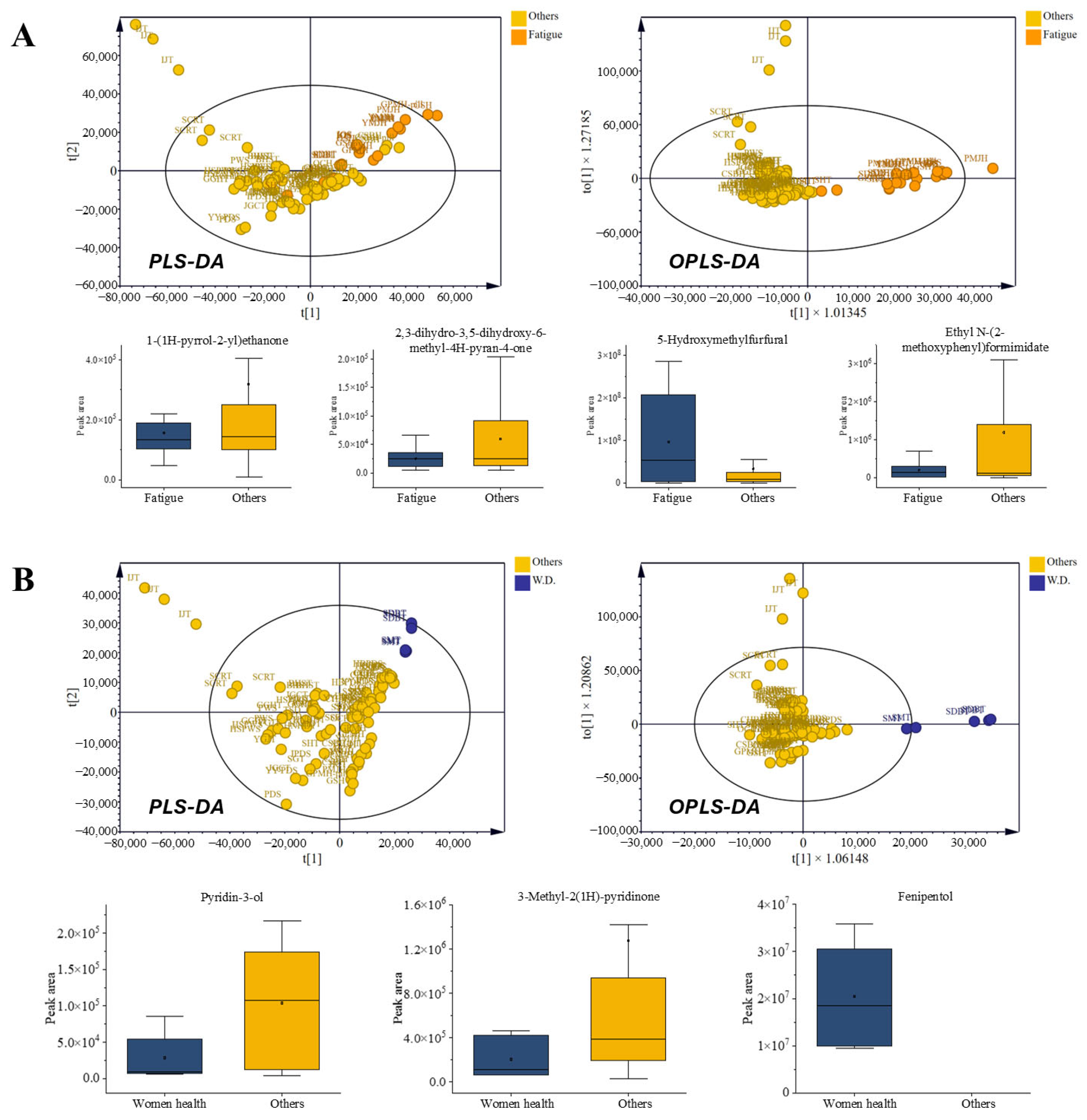

3.5. Metabolic and Hormonal Regulation-Related Prescriptions (Fatigue and Women’s Health)

3.5.1. Fatigue-Related Prescriptions

The fatigue-related prescriptions were likewise separated from other categories based on their VOC profiles. Fatigue-related prescriptions showed elevated 5-HMF but comparatively reduced 4H-pyran-4-one derivatives and nitrogen-aromatic volatiles such as 4H-pyran-4-one derivatives. In contrast, several nitrogen- and aromatic-derived volatiles, including ethanone 1-(1H-pyrrol-2-yl)ethanone, 3-pyridinol, 3-methyl-2(1H)-pyridinone, and ethyl N-(o-anisyl)formimidate, were relatively depleted in this group, along with polyfunctional pyranones and phenolic acids (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for metabolic and hormonal regulation. (A) Fatigue-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Women’s health-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for metabolic and hormonal regulation. (A) Fatigue-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Women’s health-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Herbs such as Panax ginseng and Poria cocos were recurrent components in fatigue-related prescriptions, reflecting their traditional roles in alleviating fatigue and restoring physical energy. Consistently, previous data showed that ginseng polysaccharides and red ginseng extract improved endurance in animal models, accompanied by increased hepatic and muscular glycogen levels and reduced fatigue-related biomarkers, including blood lactate, blood urea nitrogen, and malondialdehyde [37,38]. Many prescriptions in the fatigue group included P. ginseng and P. cocos, supporting the relevance of these formulations through both traditional and experimental evidence. Collectively, these findings highlight prescription-level volatile signatures that may act as candidate markers for differentiating categories with overlapping or ambiguous therapeutic uses. Such signatures reflect the emergent properties of multiherbal formulations rather than the direct pharmacological causality of individual compounds. Particularly, the compositional shift from nitrogen- and anisyl-type volatiles to sugar-derived furans and pyranones indicated a distinct volatile profile associated with fatigue-related prescriptions.

Despite sharing ingredients with other categories, the volatile outputs of fatigue-related prescriptions were clearly separated in multivariate analysis, emphasizing that prescription-level interactions, rather than individual herbs, define chemical identity

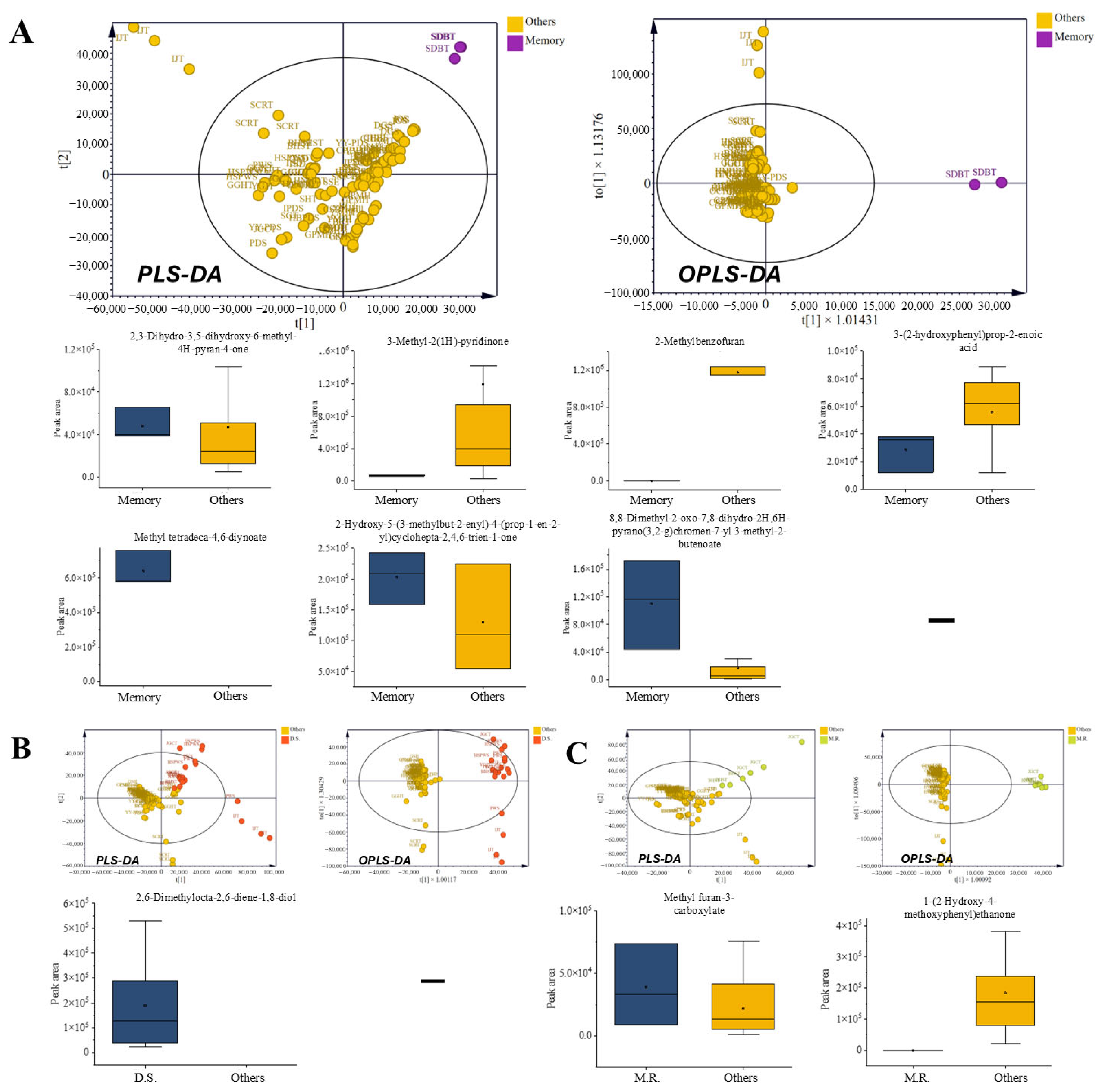

3.5.2. Women’s Health-Related Prescriptions

Women’s health prescriptions (SMT and SDBT) were characterized by a notable enrichment of alcohols, particularly fenipentol, together with increased levels of coumarin and lactone-type volatiles. In contrast, nitrogen-containing heterocycles such as 3-pyridinol and 3-methyl-2(1H)-pyridinone were comparatively less abundant than in other categories. This compositional pattern contributed to the clear separation of women’s health prescriptions in the multivariate models, as shown in Figure 5B.

Although both prescriptions contain Angelica gigas, a classical gynecological herb, their VOC outputs did not simply mirror the presence of shared botanical components. Instead, the selective accumulation of coumarin-derived lactones, along with the comparatively reduced levels of nitrogenous volatiles, indicates a prescription-level chemical identity shaped by interactions within the multi-herbal matrix. These features collectively produced a distinct volatile signature for women’s health prescriptions, which remained evident despite partial overlaps with other therapeutic categories.

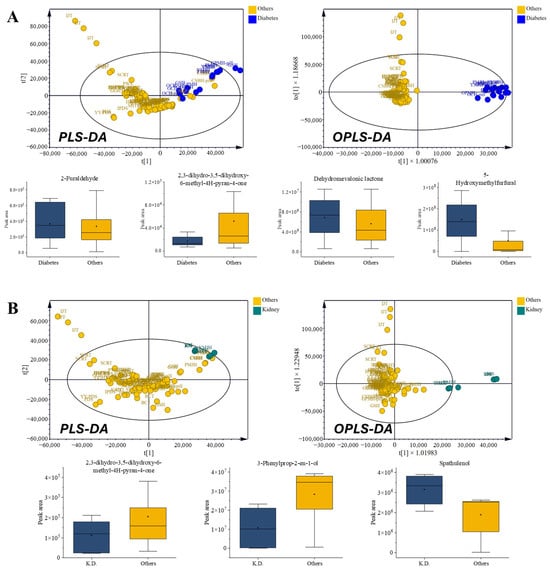

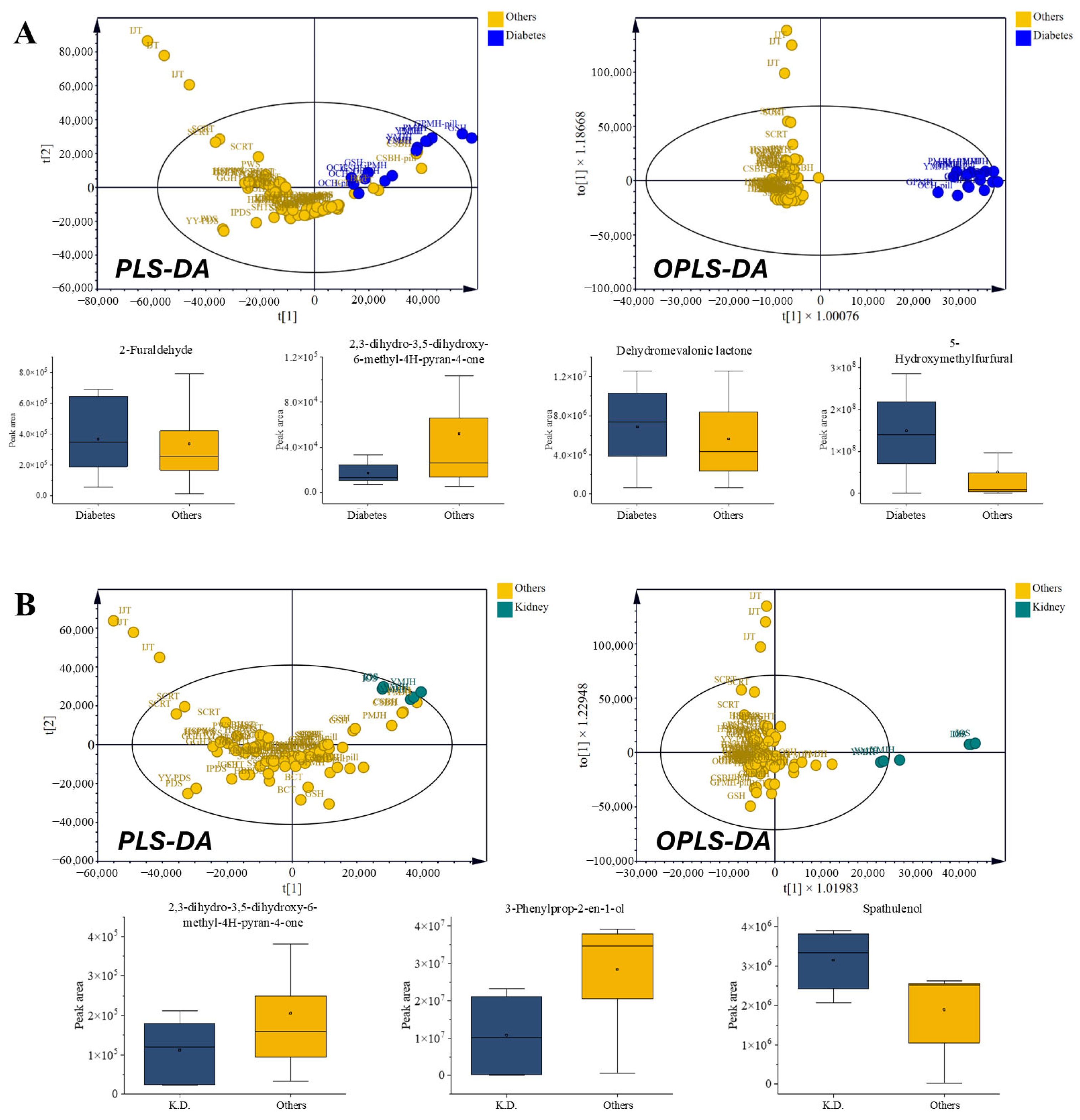

3.6. Metabolic Disorder-Related Prescriptions (Diabetes and Kidney Disorders)

3.6.1. Diabetes Prescriptions

Diabetes prescriptions (GSH, PMJH, OCH, GPMH, and YMJH) exhibited higher levels of aldehydes (such as 2-furaldehyde), lactones (including dehydromevalonic lactone), and aromatic ketones (ethanone derivatives with hydroxy/methoxy substitutions), as well as elevated 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde (5-HMF) levels, while pyranones were comparatively reduced. The diabetes-related prescriptions likewise showed a well-defined cluster distinct from Figure 6A. This enrichment of furanic and lactone-type VOCs is consistent with Maillard-type carbohydrate degradation (e.g., 5-HMF and 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one [DDMP]) and with reports that these species contribute to antioxidant/oxidative-stress modulation, aligning with their ethnopharmacological use in glycemic management [39]. Several prescriptions contained Rehmannia glutinosa [40,41] and Poria cocos [42,43], herbs traditionally employed in metabolic disorders, yet the characteristic furan- and lactone-rich profiles emerged only at the prescription level, underscoring the synergistic contribution of multi-herbal combinations.

3.6.2. Kidney Disorder-Related Prescriptions

Kidney disorder-related prescriptions (IOS and YMJH) presented contrasting VOC compositions, characterized by higher pyranone derivatives and spathulenol, while 1-(1H-pyrrol-2-yl)ethanone and 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-ol were reduced (Figure 6B). This shift indicated reduced sesquiterpene and alcohol contents alongside elevated lactones, a pattern consistent with the nephroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects frequently attributed to these prescriptions. Although kidney disorder formulas share core herbs such as R. glutinosa and P. cocos with diabetic formulas, their divergent VOC compositions highlight how distinct therapeutic identities are chemically maintained through prescription-level interactions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for metabolic disorders. (A) Diabetes-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Kidney disorder-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Figure 6.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in prescriptions for metabolic disorders. (A) Diabetes-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Kidney disorder-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

3.7. Other Functional Prescriptions (Cognitive Disorder, Digestion and Muscle Relaxation)

3.7.1. Cognitive Disorder-Related Prescriptions

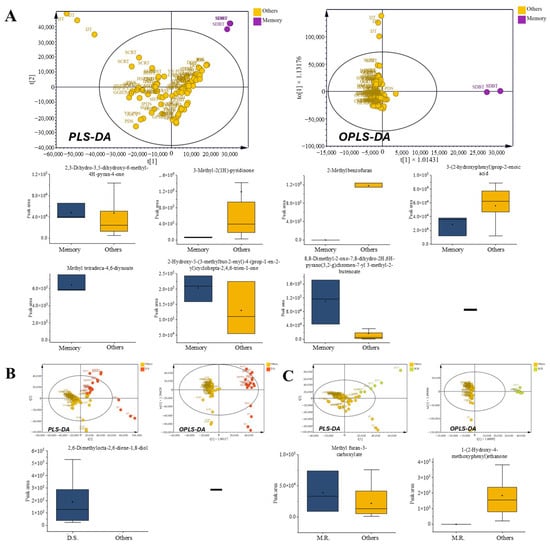

The cognitive disorder-related prescriptions showed distinct enrichment of pyranones (e.g., 4H-pyran-4-one derivatives), long-chain esters such as methyl 4,6-tetradecadiynoate, and aromatic ketones including cycloheptatrienone and pyranochromen-butenoate. In parallel, these prescriptions consistently showed depletion of nitrogenous heterocycles (such as 3-methyl-2(1H)-pyridinone), benzofuran derivatives (e.g., 2-methylbenzofuran), and phenolic acids such as (E)-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic acid (Figure 7A). This dual pattern of enriched VOCs with potential neuromodulatory activity and reduced compounds considered inhibitory or stress-related provides a plausible chemical rationale for their ethnopharmacological use in enhancing cognition. Although A. gigas was noted in other therapeutic categories, its presence coincided with a distinctive VOC fingerprint, reinforcing the category-specific chemical identity of cognitive disorder-related prescriptions.

3.7.2. Digestion-Related Prescriptions

Digestion-related prescriptions (IJT, JGCT, PWS, HSPWS, YGJT, and BHST) were uniquely characterized by enrichment for the monoterpenoid diol 2,6-dimethyl-2,6-octadiene-1,8-diol. This enrichment suggests a potential contribution to gastrointestinal protection or antimicrobial activity, consistent with the traditional application of these formulas in managing digestive disturbances. Several of these prescriptions include herbs such as Atractylodes japonica [44] and Citrus aurantium [45], both of which have been associated with stomach and carminative effects. However, the emergence of a monoterpenoid-rich VOC profile emphasizes the role of the prescription overall in defining its chemical signature rather than attributing it to any single herb. This monoterpenoid-driven profile was reflected in a distinct volatile distribution pattern in multivariate analysis (Figure 7B).

3.7.3. Muscle Relaxation-Related Prescriptions

The muscle-relaxants JGCT and BHST were consistently characterized by low abundances of furan esters and aromatic ketones. Specifically, the levels of Methyl 3-furoate and 1-(2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethan-1-one were depleted when compared with those in the other categories (Figure 7C). This dual reduction delineated a coherent volatile profile specific to the muscle relaxant prescriptions. Although overlapping herbs (such as C. officinale) were present in other groups, the combined depletion of furanic and ketone-type volatiles distinguished the category, thereby supporting its differentiation at the prescription level.

3.8. Ethnopharmacological Implications

Our results extend beyond chemical differentiation and provide a framework for understanding prescription efficacy in ethnopharmacology. The identification of volatiles that recur across multiple categories supports the idea that convergent biochemical pathways underlie their broad-spectrum use in traditional practice. Conversely, the presence of category-specific markers illustrates how therapeutic boundaries are maintained, even when prescriptions share many botanicals. This duality emphasizes that the efficacy of traditional formulas is not dictated by the sum of their individual herbs but, rather, by emergent VOC signatures arising from their unique combinations.

Thus, VOC profiling provides chemical support for the traditional logic of categorization systems. For example, cold- and inflammation-related prescriptions overlapped in terms of their phenolic- and furan-rich backgrounds but diverged in terms of markers such as isopsoralen and 4-ethenyl-2-methoxyphenol, consistent with their differential clinical indications. In contrast, 5-HMF was more common in prescriptions related to inflammation, fatigue, diabetes, and kidney health, highlighting its role as a shared yet context-dependent marker across multiple categories and with their differential clinical indications. Similarly, diabetes- and kidney disorder-related prescriptions, despite containing R. glutinosa and P. cocos, yielded contrasting VOC profiles, mirroring findings with metabolomics studies distinguishing traditional categories using chemical fingerprints [46,47]. By capturing both convergent and category-specific signatures, VOC analysis underscores how the collective matrix effect drives chemical convergence or divergence, thereby offering a chemical rationale for the therapeutic boundaries recognized in traditional medicine.

Figure 7.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in other functional prescription categories. (A) Cognitive disorder-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Digestion-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (C) Muscle relaxation-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Figure 7.

Comparison of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in other functional prescription categories. (A) Cognitive disorder-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (B) Digestion-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1. (C) Muscle relaxation-related prescriptions: radar chart of chemical classes, multivariate score plots (PLS-DA and OPLS-DA), and box plots of VOCs with VIP > 1.

Importantly, these findings should not be interpreted as the pharmacological effects of single herbs or isolated compounds. Instead, they reflect prescription-level signatures that emerge from the interactions of multiple botanicals within each formula. This holistic perspective is particularly relevant for categories with overlapping or ambiguous therapeutic boundaries, where VOC markers provide informative differentiation. Rather than serving as absolute determinants, these compounds act as candidate indicators highlighting how complex chemical matrices generate emergent properties that are distinct from the sum of their parts. Framing our results within this framework highlights that the logic of traditional prescriptions cannot be fully explained by reductionist herb-by-herb analyses but requires recognition of the collective chemical identity shaped by multi-herbal combinations. This approach strengthens the chemical rationale for ethnopharmacological classification and illustrates how modern profiling techniques can reveal emergent principles embedded in traditional medical practice.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the utility of VOC profiling for interpreting the chemical complexity of multi-herbal prescriptions. Using HS-SPME-GC-MS combined with multivariate analyses, we successfully differentiated 30 prescriptions composed of 76 herbal ingredients and identified 25 VOCs that contribute to prescription-level separation. Some of these compounds were shared across multiple therapeutic categories, whereas others were category-specific, indicating that VOC patterns reflect both the overlap and the boundaries inherent in traditional formulation practices.

Although traditional prescriptions are applied across diverse indications, their VOC profiles exhibit recognizable chemical tendencies that can assist in distinguishing categories. By resolving their VOC profiles, we provide quantitative evidence that prescription-level chemical tendencies correspond, at least in part, to these traditional categorizations. The presence of recurrent VOCs across categories highlights the internal complexity of multi-herb systems, while differences in their relative abundances suggest chemical cues that may support category-level discrimination.

This work establishes a coherent chemical framework for interpreting the compositional structure of traditional multi-herbal prescriptions through their VOC profiles. Expanding this approach with broader datasets and complementary analytical platforms will further refine how VOC information can be used to interpret and systematize the chemical logic underlying traditional prescription practices. The VOC profiles of complete prescriptions thus constitute a robust and coherent chemical framework, offering objective data to support the refinement of ethnopharmacological classifications and the standardization of traditional formulations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010008/s1, Figure S1: Representative TICs of VOCs obtained from 30 traditional herbal prescriptions; Figure S2: Cross-validation of supervised models. (A) Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) score plot. (B) Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) score plot; Table S1: Complete HS-SPME-GC-MS profile of volatile compounds from 30 traditional prescriptions; Table S2: Compositions of herbal prescriptions: component herbs and representative indications; Table S3: Plant parts used for each constituent herb in the analyzed prescriptions.

Author Contributions

S.B.H.: research design; supervision; provided financial and material support; writing—review and editing. S.S.: experiments and tests; data disposal; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft. U.K.: formal analysis; investigation; data curation. J.K.: formal analysis; investigation; data curation. C.J.: formal analysis; investigation; data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Graduate Research Scholarship in 2021, and by a grant (21173MFDS561) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2023.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pan, S.Y.; Zhou, S.F.; Gao, S.H.; Yu, Z.L.; Tang, M.K.; Sun, J.N.; Zhou, J.; Ko, K.M. New perspectives on innovative drug discovery: An overview. Asian J. Pharmacol. 2010, 13, 450–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.A.; Urban, S.; Roessner, U.J.M. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites 2012, 2, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenard, D.; Gueritte-Voegelein, F.; Potier, P.J. Taxol and taxotere: Discovery, chemistry, and structure-activity relationships. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Daryabari, A.M.; Gholizadeh, B.; Farajnia, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Ghasemnejad, T. The role of hesperidin in cell signal transduction pathway for the prevention or treatment of cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 22, 3462–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha; Jaggi, A.S.; Singh, N. Silymarin and its role in chronic diseases. In Drug Development for Modern Medicine, 1st ed.; Panda, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Long, M.; Li, P. Quercetin: Its main pharmacological activity and potential application in clinical medicine. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 8825387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, D.K.; Dash, S.; Pradhan, S.K.; Panda, S.K. Revisiting the medicinal value of terpenes and terpenoids. In Revisiting Plant Biostimulants; Pradhan, S.K., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox-Georgian, D.; Ramadoss, N.; Donoviel, M.; Basu, C. Therapeutic and medicinal uses of terpenes. In Nutraceuticals: Efficacy, Safety and Toxicity; Gupta, R.C., Lall, R., Srivastava, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balunas, M.J.; Kinghorn, A.D. Drug discovery from medicinal plants. Life Sci. 2005, 78, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Dias, D.A. The pharmaceutical industry and natural products: Historical status and new trends. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Rabe, T.; McGaw, L.J.; Jäger, A.K.; Van Staden, J. Towards the scientific validation of traditional medicinal plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2001, 34, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Liu, R.; Cui, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, J. Network pharmacology and traditional medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhao, C.; Lu, F.; Wu, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, T.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. Traditional Chinese medicine in treating influenza: From basic science to clinical applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 575803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhaoguo, L.; Qing, W.; Yurui, X. Key concepts in traditional Chinese medicine Ii. In Key Concepts in Traditional Chinese Medicine II; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, D. Hypericum sampsonii Hance: A review of its botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, biological activity, and safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1247675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.-G.; Huynh, T.H.; Peng, B.-R.; Pham, N.-T.; El-Shazly, M.; Chen, L.-Y.; Wang, L.-S.; Yen, P.-T.; Lai, K.-H. Investigating the therapeutic potential of terpene metabolites in hot-natured herbal medicines and their mechanistic impact on circulatory disorders. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 5343–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Gorycki, P. Bioactivation of herbal constituents: Mechanisms and toxicological relevance. Drug Metab. Rev. 2019, 51, 453–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shuhaib, M.B.S.; Al-Shuhaib, J.M. Assessing therapeutic value and side effects of key botanical compounds for optimized medical treatments. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Santana Souza, M.T.; de Souza Siqueira Quintans, J.; da Silva, F.P.; Oliveira, E.R.A.; Menezes-Filho, J.E.C.; Santos, M.R.V.; Piuvezam, M.R.; Gonsalves, A.P.S.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J. Structure–activity relationship of terpenes with anti-inflammatory profile–A systematic review. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 115, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.; Meireles, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Guimarães, M.M.; Endringer, D.C.; Scherer, R.; Romanha, B.S.; Kaplum, V.; De Simone, G.A.; Caliari, M. Antibacterial activity of terpenes and terpenoids present in essential oils. Molecules 2019, 24, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, H.; Kashiwadani, H.; Kanemaru, K.; Nihei, H.; Nakamura, T. Linalool odor-induced anxiolytic effects in mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 414763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Heinbockel, T. The effects of essential oils and terpenes in relation to their routes of intake and application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E.; Gertsch, J.; Appendino, G. Plant volatiles: Production, function and pharmacology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1359–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.-J.; Hua, Y.-L.; Ji, P.; Yao, W.-L.; Zhang, W.-Q.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.-M. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory effects of volatile oils from processed products of Angelica sinensis radix by GC–MS-based metabolomics. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 191, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Chen, D.; Xiao, Z. Natural volatile oils derived from herbal medicines: A promising therapy way for treating depressive disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edris, A.E. Pharmaceutical and therapeutic potentials of essential oils and their individual volatile constituents: A review. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksenov, A.A.; Laponogov, I.; Zhang, M.; Doran, S.L.; Traub, J.; Mast, T.J.; Liu, X.; Warth, B.; Kuzmanov, I.; Nothias, L.-F. Auto-deconvolution and molecular networking of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KP, R.F.; Suresh, M.; Prabhu, V.; Meenakshisundaram, M. PHYTOCHEMICAL SCREENING AND ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY IN PENNISETUM POLYSTACHION. L. World J. Pharm. Res. 2025, 14, 1162–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.; Zuo, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Huang, S.; Luo, D.; Zhu, H. Studying the efficacy of JBOL volatile components in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) using GC-MS and network pharmacology. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.G.; Li, F.F.; Brimble, M.A. Spiroketal natural products isolated from traditional Chinese medicine: Isolation, biological activity, biosynthesis, and synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 1786–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, D.; Liang, W. Psoralen and Isopsoralen Activate Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 Through Interaction with Kelch-Like ECH-Associated Protein 1. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukai, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Miyoshi, Y.; Fukuda, Y.; Miki, J.; Tanaka, A.; Nomura, M. Pharmacological activity of compounds extracted from persimmon peel (Diospyros kaki THUNB.). J. Oleo Sci. 2009, 58, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafis, A.; Elgadiry, M.H.; Oukhrib, M.; Aoujil, J.; Amamra, H.; Benali, T.; Aboulghazi, A.; Lhadi, E.K.; El Hajaji, R. New insight into antimicrobial activities of Linaria ventricosa essential oil and its synergetic effect with conventional antibiotics. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 4361–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, R.; Hu, T.; Li, Z.; Sun, X. Color-reflected chemical regulations of the scorched rhubarb (Rhei Radix et Rhizoma) revealed by the integration analysis of visible spectrophotometry, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.N.K.; Kim, M.S.; Ryoo, S.Y.; Oh, W.K.; Kim, Y.H. Anti-inflammatory activity of compounds from the rhizome of Cnidium officinale. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Wu, C.; Gong, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Qu, Y.; Huang, S.; Sun, W. Recent advances in Panax ginseng CA Meyer as a herb for anti-fatigue: An effects and mechanisms review. Foods 2021, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arring, N.M.; Millstine, D.; Marks, L.A.; Fick, L.J. Ginseng as a treatment for fatigue: A systematic review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapla, U.M.; Solayman, M.; Alam, N.; Khalil, M.I.; Gan, S.H. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) levels in honey and other food products: Effects on bees and human health. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, G.; Lin, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhu, H.; Lu, C.; Qin, H.; Zhang, L. Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. polysaccharide ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia and vascular inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 164, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Lu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zuo, Z. UPLC-Q/TOF-MS-based serum metabolomics reveals hypoglycemic effects of Rehmannia glutinosa, Coptis chinensis and their combination on high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in KK-Ay mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, T.Y.C.; Ong, K.L.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Review of the effects of the traditional Chinese medicine Rehmannia Six Formula on diabetes mellitus and its complications. J. Diabetes 2011, 3, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jeon, K.H.; Kim, S.Y. The role of the herbal medicines, Rehmanniae radix, Citrus unshiu peel, and Poria cocos wolf, in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019, 15, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonrungsesomboon, N.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Karbwang, J. Therapeutic potential and pharmacological activities of Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, J.A.S. An overview of Citrus aurantium used in treatment of various diseases. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2011, 5, 390–395. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, D.K.; Chau, F.-T. Chemical information of Chinese medicines: A challenge to chemist. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2006, 82, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N. Synergy, additive effects, and antagonism of drugs with plant bioactive compounds. Drugs Drug Candidates 2025, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.