Abstract

Screening is a critical link in the separation of gold ores. However, issues such as the agglomeration of material masses and screen aperture blinding often lead to low screening precision and poor desliming performance, severely impacting the efficiency of subsequent crushing processes. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a rigid–flexible coupled screening method for viscous and moist gold ores. The time-frequency response characteristics of the screen surface motion were investigated, the influence of processing capacity and moisture content on screening performance was analyzed, and an industrial performance evaluation of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface was conducted. Laboratory and industrial test results demonstrate that the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface exhibits a periodic, non-regular waveform with a maximum peak vibration intensity of 14.79 g. Screening efficiency is synergistically inhibited by moisture content and processing capacity. When the ore moisture content is below 3% and the processing capacity ranges from 15 to 22.5 t/(h·m2), the screening efficiency can exceed 85%. Compared with conventional screen surfaces, the implementation of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface achieved a desliming efficiency of 91%, a maximum processing capacity in the crushing stage of 380 tons per hour, a nearly 12% improvement in the screening efficiency of the closed-circuit checking process for crushed products, and an approximately 8% reduction in the circulating load ratio of the crushing circuit. These enhancements collectively ensure the stable operation of both the screening and crushing processes.

1. Introduction

Minerals are fundamental resources for national economic development and national defense construction. China is a major producer and consumer of mineral resources [1]. However, China’s mineral resources are characterized by poor endowment and a high proportion of low-grade minerals. Raw ore cannot be directly used in metallurgical, chemical engineering, or gold deep-processing applications unless it is first upgraded through beneficiation to produce a concentrate [2,3,4]. Screening is a key link in the beneficiation process. Efficient screening is crucial for realizing particle size classification and desliming, which can subsequently reduce the energy consumption of mineral crushing, improve the operational stability of the beneficiation process, and is of great significance for promoting the large-scale, clean, and efficient processing and utilization of mineral resources [5,6].

With the advancement of mechanized mining in deep resource extraction, the fines content in raw ores has progressively increased. Under the influence of measures such as water spraying for dust suppression, the ores exhibit challenging characteristics, including high surface moisture, severe slime coating, and a significant proportion of particles near the screen aperture size [7]. This easily leads to the formation of covering films and clogging of the screen surface, gradually deteriorating the traditional screening process, affecting the screen surface opening rate and screening effect, and seriously restricting the utilization efficiency of mineral resources [8,9,10]. In response to the screening challenges associated with difficult-to-screen ores, researchers worldwide have established the elastic screening theory and developed elastic screen surfaces that meet the demands of efficient screening for sticky and moist minerals. These screens, constructed from flexible materials, utilize elastic deformation to deliver greater additional vibrational energy [11,12,13]. The flip-flow screen is a typical elastic screening equipment currently, whose screen surface undergoes forced stretching to achieve flexural deformation, significantly improving screening efficiency [14,15]. However, the flip-flow screening process imposes high demands on the bending and tensile fatigue strength of the screen material. Under impact from hard materials, the screen is prone to damage, leading to a substantial reduction in service life [16]. Researchers have conducted extensive studies on this issue, focusing on the accumulation of fatigue in the screen during flip-flow motion and implementing reinforcement designs in local areas to enhance its durability [17]. Currently, flip-flow screens are primarily used in coal classification and iron ore deep screening, with relatively limited application in the processing of broadly sized sticky and moist gold ores [18]. The rigid–flexible coupled screen surface combines the high strength of rigid materials with the large toughness of elastic materials, exhibiting potential advantages in the dry screening of broadly sized sticky and moist minerals [19].

This study addresses the challenges in dry screening of difficult-to-screen, sticky, and moist gold ores by proposing a rigid–flexible coupled screening method. The study focuses on investigating the time-frequency response characteristics of the screen surface kinematics, clarifying the influence of key operational parameters on the screening performance, and validating the advantages of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface through industrial trials. The findings are expected to provide theoretical and technical guidance for the efficient screening of sticky and moist minerals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental System

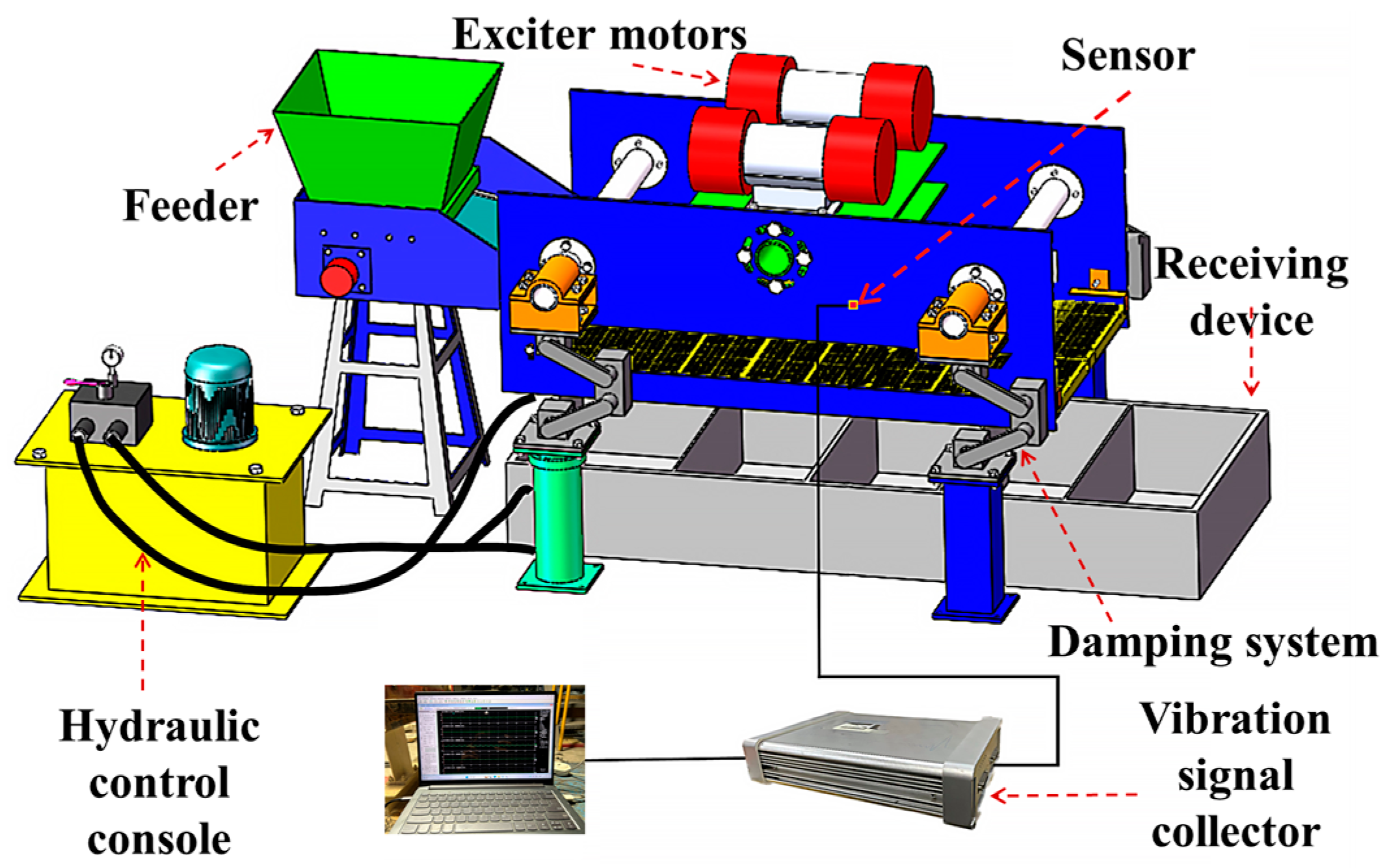

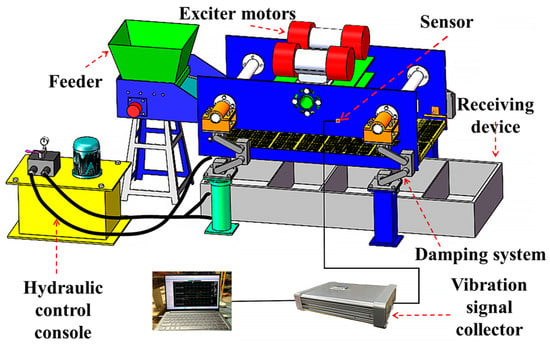

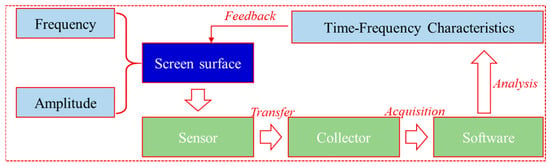

The screening and testing system, as shown in Figure 1, is composed of a feeder, a vibrating screen, and a vibration signal analysis system. The feeder is driven by a vibration motor to achieve uniform material supply, with the feeding rate adjustable based on the motor’s vibration frequency. The vibrating screen primarily includes vibration exciter motors, a hydraulic control console, a vibration-damping system, a material receiving device, and a rigid–flexible coupled screen surface. The vibrating screen measures 1.2 m in length and 0.6 m in width. Two sets of self-synchronizing vibration exciter motors form the excitation system of the vibrating screen, whose excitation force is adjusted by varying the angle between the eccentric blocks of the motors. The vibration frequency is regulated by a frequency converter, with the adjustable range of the amplitude and vibration frequency of the vibrating screen being 0–8 mm and 0–16.67 Hz, respectively.

Figure 1.

Screening and testing system.

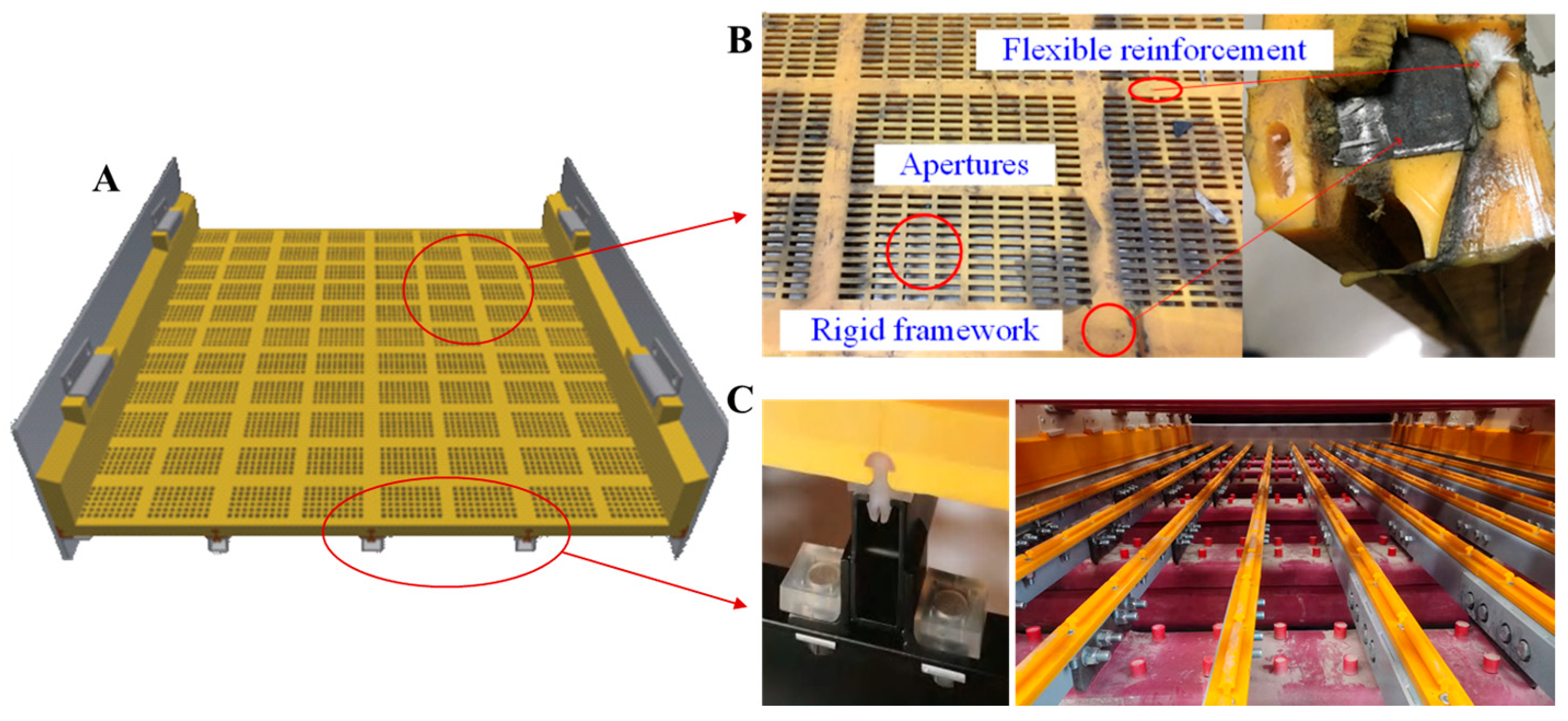

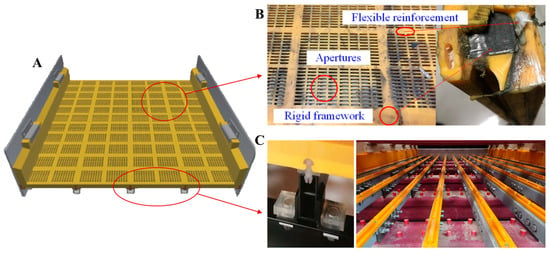

The rigid–flexible coupled screen surface is integrally cast from a rigid framework and high-elasticity polyurethane flexible material, comprising the rigid framework, flexible reinforcement ribs, and the polyurethane flexible screen surface area. Firstly, the high-elasticity polyurethane material is vulcanized at an elevated temperature to form a primarily vulcanized screen surface, which is then pre-tensioned to induce significant stretching. Subsequently, the primarily vulcanized screen surface, high-hardness fiber materials, and the rigid framework undergo secondary vulcanization, forming the integrated structure of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface. Finally, the screen surface is subjected to a 12 h vulcanization process at a controlled temperature. Through these three stages of temperature-varying vulcanization, the screen surface acquires enhanced properties including tensile resistance, impact resistance, and aging resistance. As shown in Figure 2, a single screen panel measures 1200 mm × 300 mm × 90 mm (length × width × height), with aperture dimensions of 13 × 13 mm and an open area ratio exceeding 30%. The installation section of the screen surface employs a buckle-beam structure-based mounting method, where the screen surface is connected to the beam via rail seats, ensuring sufficient installation strength.

Figure 2.

Experimental screen surface ((A) rigid–flexible coupling screen surface; (B) screen surface detail structure; (C) screen surface installation method).

2.2. Ore Particle Size Characteristics

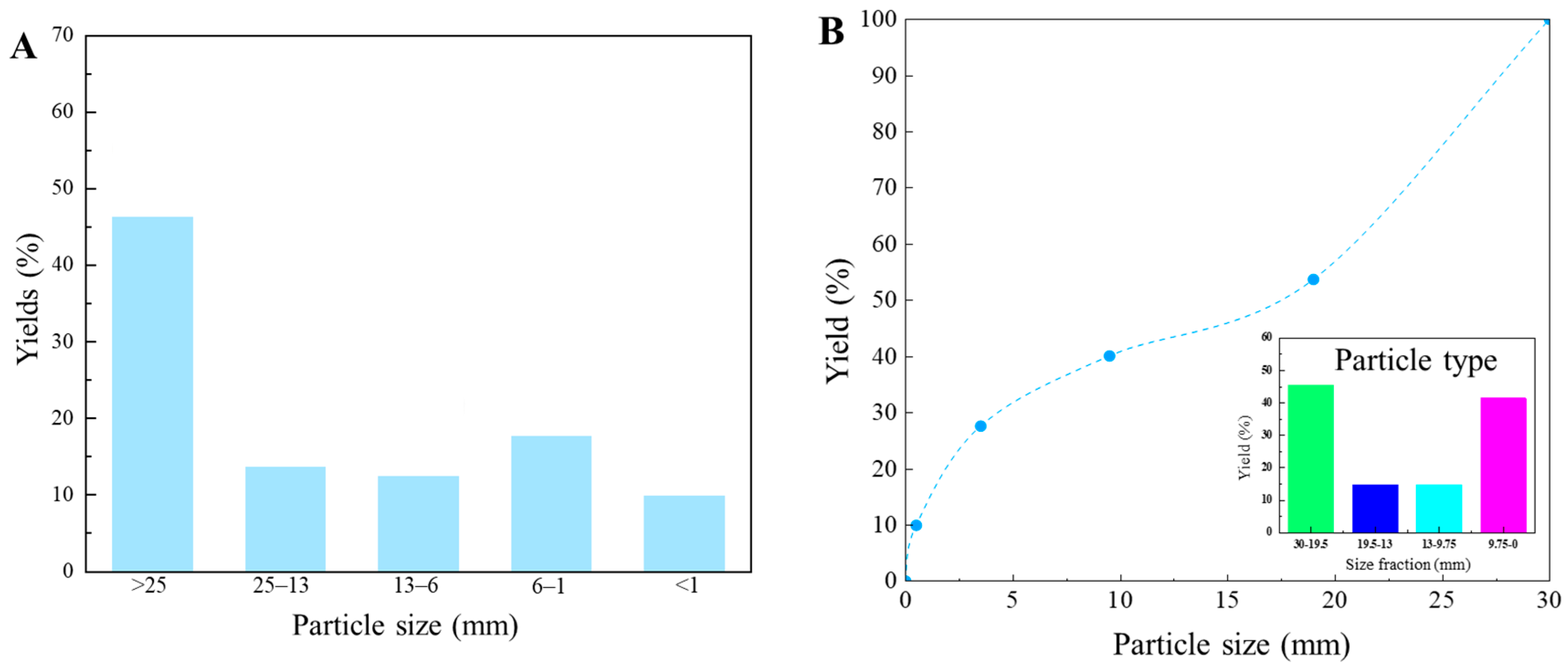

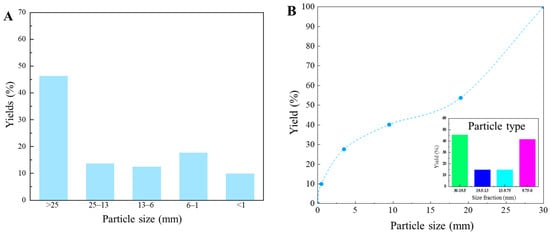

The selected samples were collected from the mineral processing plant of Shandong Gold Mining (Linglong) Co., Ltd, located in Zhaoyuan City, China. The ore has a density of approximately 2.71 t/m3 and the hardness coefficient of 12–14 (determined via the Protodyakonov Hardness Test), which classifies it as a medium-hard ore. The particle size distribution of the raw ore is characterized in Figure 3. The cumulative distribution curve (Figure 3B), derived from the fractional yield data (Figure 3A), reveals that nearly 40% of the ore is smaller than 13 mm, and approximately 10% is finer than 1 mm. Based on the relative size to the screen aperture (dA), the particles are categorized as oversize (>1.25 dA), obstructive (1.25–1 dA), hard-to-screen (0.75–1 dA), and easy-to-screen (<0.75 dA) particles. Notably, the combined fraction of hard-to-screen and obstructive particles accounts for about 27.5%. These particles are prone to adhesion and agglomeration in the presence of water, which hampers material stratification during screening and increases the risk of misplacement. Furthermore, the ore has an external moisture content of 2–5%, as determined by oven-drying at 105 ± 5 °C to a constant weight, and a primary slime content (<0.074 mm) of 3.5%, as obtained from the cumulative curve.

Figure 3.

Ore size distribution ((A) yield of each size fraction; (B) particle size cumulative curve).

2.3. Experimental Procedure

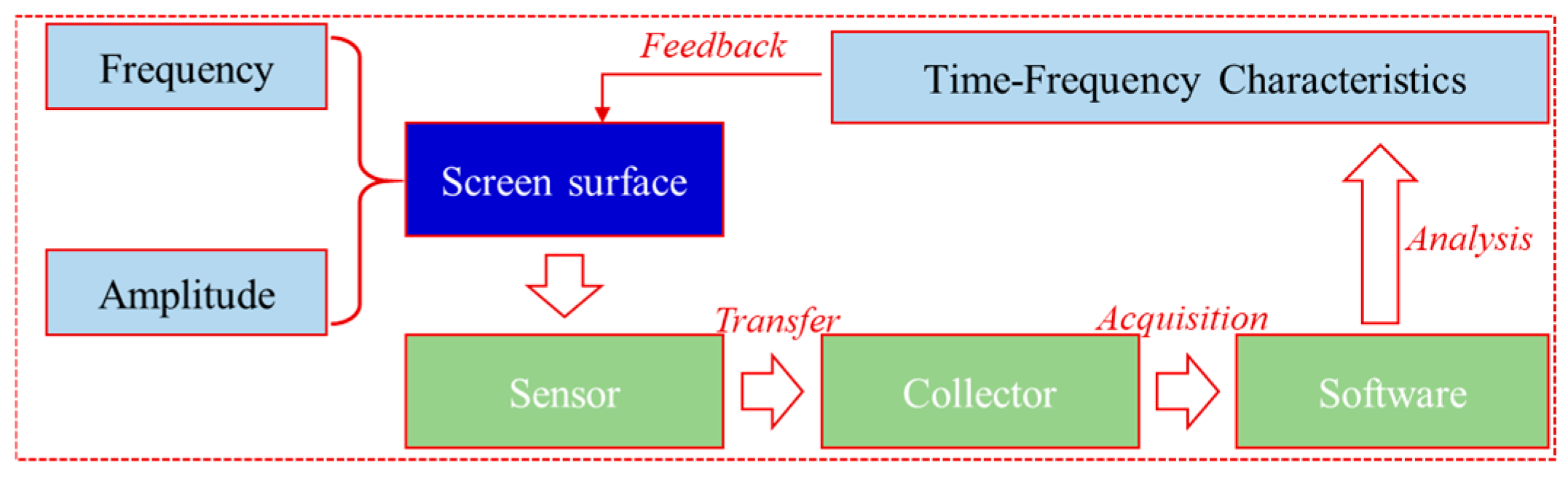

The vibration signal analysis system is employed to acquire and analyze the kinematic signals of the screen body and the screen surface. During the testing process, sensors are fixed to the designated measurement points and connected to the acquisition instrument via insulated cables. The acquisition instrument is subsequently linked to a computer terminal using a dedicated network cable. The power supply, the multi-channel synchronous acquisition instrument, and the Data Acquisition and Signal Processing software (DASPs) are activated sequentially. Within the DASPs, the parameters for each direction of the sensors are calibrated, and the sampling frequency is set to 1024 Hz. Prior to initiating the test, the low-pass filter frequency is set to 50 Hz, and zero balancing is performed on the oscilloscopic signals to eliminate signal offset. Once the dynamic testing system is prepared, the vibrating screen is started to commence the collection of vibration acceleration signals. As shown in Figure 4, the acceleration signals from the measurement points are converted into velocity and displacement signals through Simpson’s integral method. Time-frequency characteristics of the signals are then obtained by performing auto-spectral and three-dimensional spectral array analyses.

Figure 4.

Vibration signal acquisition instrument and its data analysis process.

The research methodology employed a two-phase approach. First, laboratory batch screening tests were designed to quantitatively assess the impact of feed rate and external moisture content. The particle size distributions of the feed, oversize, and undersize materials were analyzed to determine screening efficiency. All laboratory tests were conducted in triplicate to validate the consistency of the results. In the second phase, based on the laboratory findings, the screen surface of an industrial vibrating screen was replaced, and its performance was compared directly with that of the original panel under field conditions. The screening efficiency was adopted as the primary evaluation index [20], and its calculation formula is presented as follows. Where η is the screening efficiency, %; Ec is the effective placement efficiencies of coarse particles, %; Ef is the effective placement efficiency of fine particles, %; γo is the yield of oversized product, %; Oc is the ratio of coarse particles in the oversized product, %; Of is the ratio of fine particles in the oversize product, %; Fcr is the ratio of coarse particles in the calculated feed, %; Ffr is the ratio of fine particles in the calculated feed, %.

3. Results

3.1. Kinematic Characteristics of the Rigid–Flexible Coupled Screen Surface

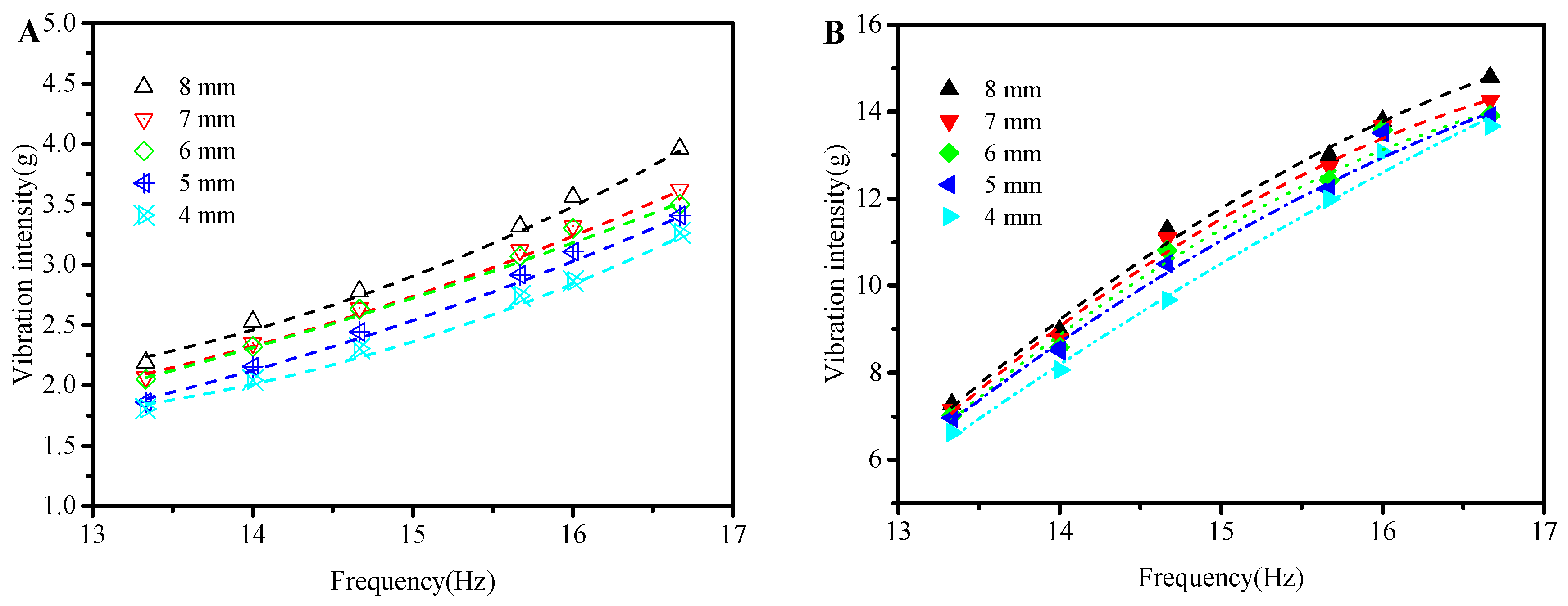

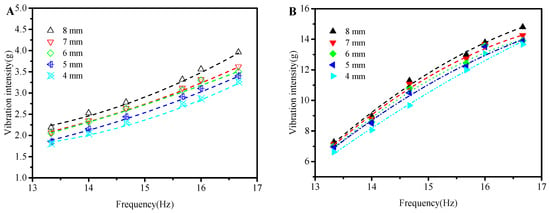

To clarify the response pattern of screen surface and screen body vibration intensity to excitation parameters, the variation in vibration intensity with excitation frequency under different amplitudes was investigated. As shown in Figure 5A,B, with screen body amplitudes set at 8 mm, 7 mm, 6 mm, 5 mm, and 4 mm, and vibration frequencies set at 13.33 Hz, 14.00 Hz, 14.67 Hz, 15.56 Hz, 16.00 Hz, and 16.67 Hz, the variation patterns of screen surface vibration intensity were examined, and its response to excitation parameters was analyzed. Under all tested screen body amplitudes, the vibration intensity increased with rising vibration frequency. When the frequency varied from 13.33 Hz to 16.67 Hz, the screen surface vibration intensity demonstrated a notable increase from 6.62 to 14.79 g, which far exceeds the vibration intensity of the screen body. The high vibration intensity enhances the loosening and segregation of viscous, moist ores, thereby facilitating the penetration of particles through the screen. Furthermore, the screen surface vibration intensity significantly exceeded that of the screen body, achieving an amplification of the input vibration intensity value.

Figure 5.

The variation in vibration intensity with excitation frequency under different screen body amplitudes ((A) screen body vibration intensity; (B) screen surface vibration intensity).

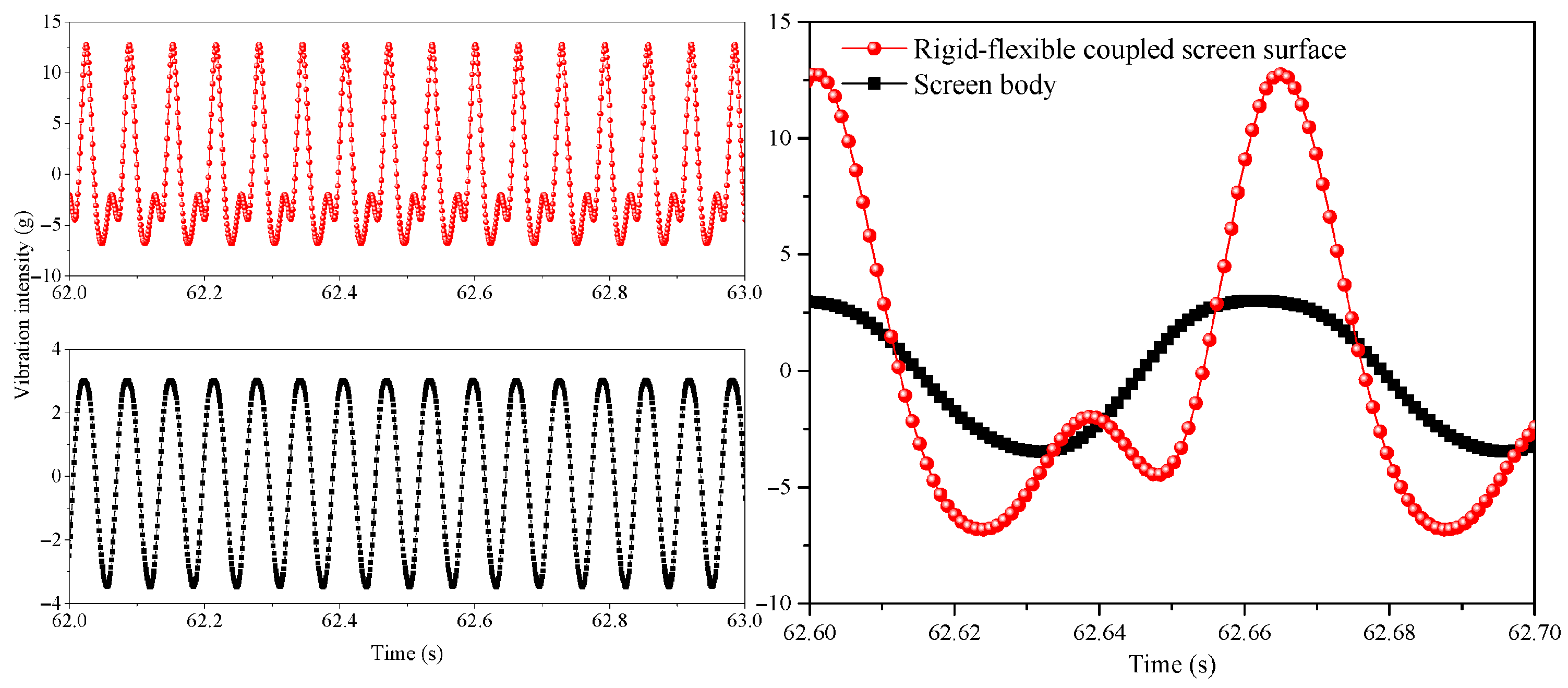

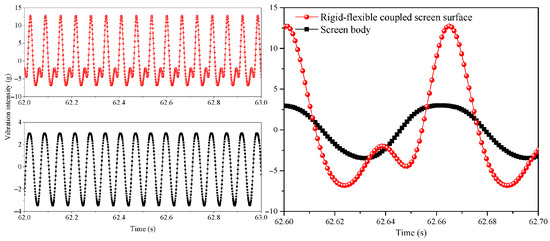

Under the conditions of a screen body amplitude of 8 mm and an excitation frequency of 15.56 Hz, the kinematic time-domain characteristics of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface were analyzed. As shown in Figure 6, which displays the variation in vibration intensity for both the screen body and the screen surface, it can be observed that the screen body exhibits a regular, simple harmonic motion waveform with an average peak value of 3 g. In contrast, the screen surface displays a periodic, non-regular waveform with a maximum peak value of 13 g. The substantially higher vibration intensity is a prerequisite for enhancing the fragmentation and dispersion of material agglomerates. Furthermore, analysis of the time-domain characteristic curve of the screen surface’s vibration intensity reveals that significant deformation of the screen surface is the key condition for generating its high vibration intensity.

Figure 6.

Time-domain kinematic characteristics of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface.

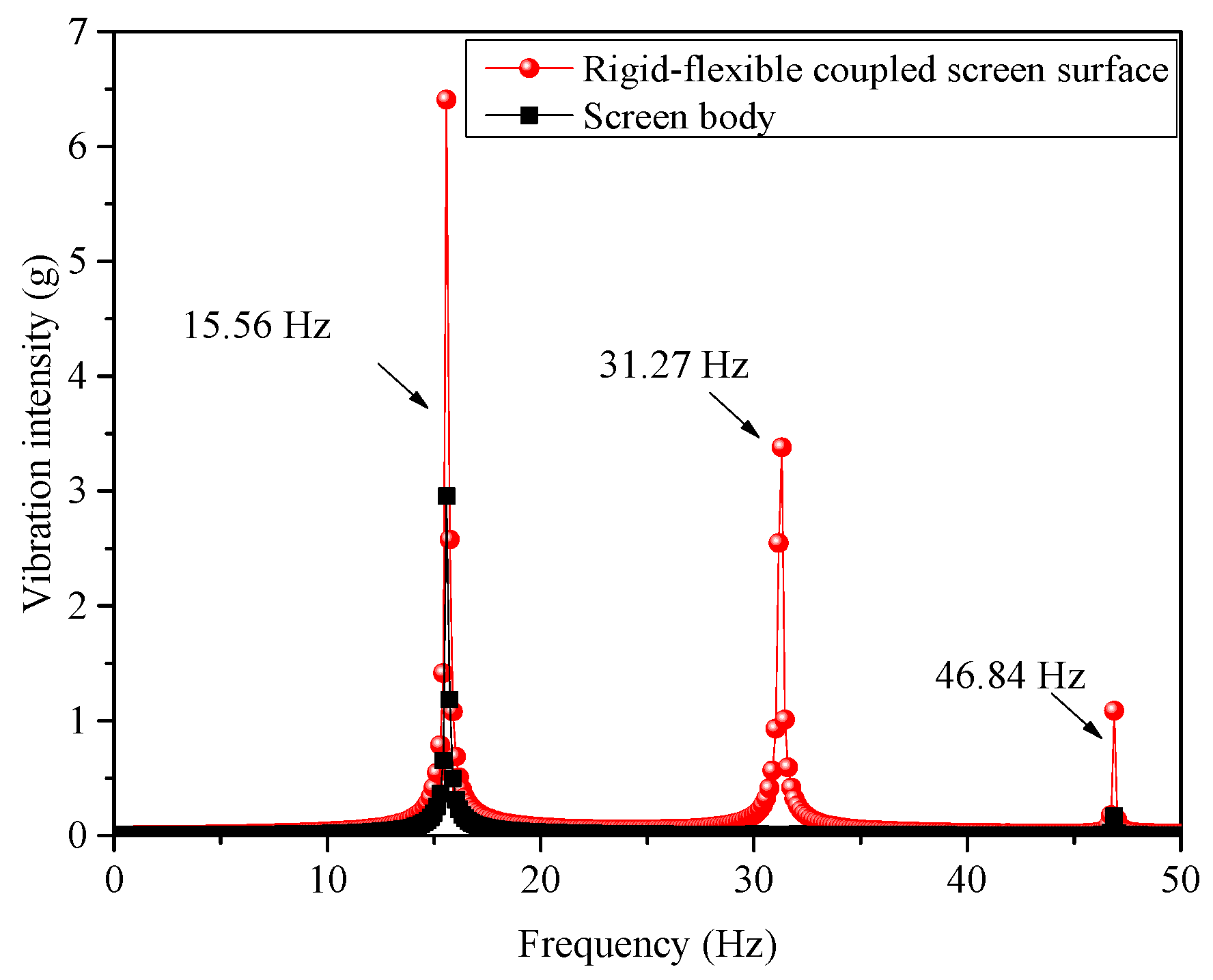

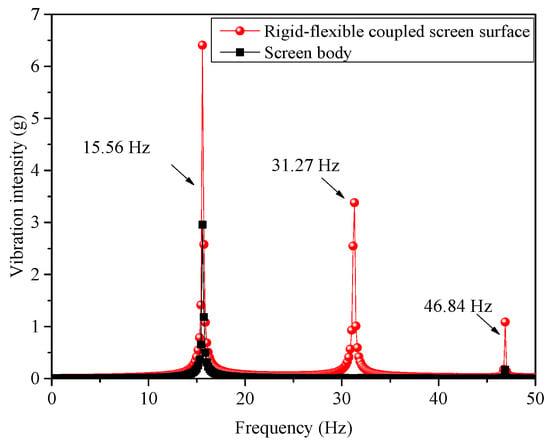

This phenomenon facilitates the dislodgment of particles stuck in the screen apertures, thereby achieving an efficient self-cleaning effect. Further frequency-domain analysis was performed on the vibration intensity signal, as illustrated in Figure 7. Three distinct vibrational components can be clearly identified in the screen surface’s response. Two of these components share the same frequency as the screen body, with the dominant frequency at 15.56 Hz, which is the vibration frequency converted from the electrical current frequency. The frequency of 46.84 Hz is likely attributable to additional motion of the screen surface and body induced by material impact. The frequency of 31.27 Hz, which appears exclusively in the screen surface’s motion, is generated by additional movement during the deformation process of the screen surface.

Figure 7.

Frequency-domain characteristics of screen surface vibration intensity.

3.2. Influence Laws of Key Parameters on Screening Effect

To verify the screening effect of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface, a screening test was carried out in the next section to further analyze the influence mechanism of key parameters on the screening effect.

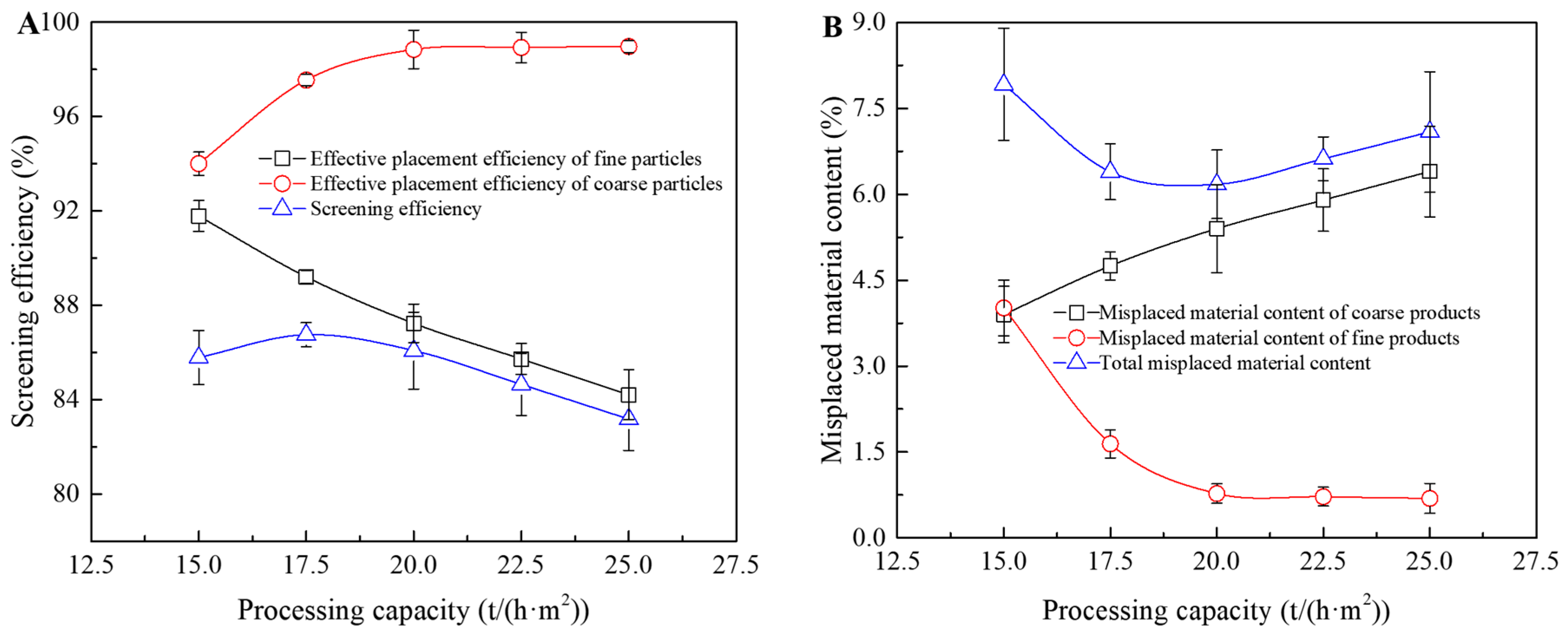

3.2.1. Influence of Processing Capacity on Rigid–Flexible Coupled Screening Efficiency

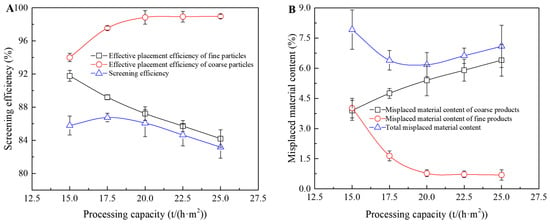

Processing capacity affects the thickness of the material layer on the screen during the screening process. An excessively high processing capacity inhibits the loosening and stratification of ore, while an excessively low processing capacity fails to meet the requirements of large-scale ore production. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate this parameter to determine the optimal feeding rate. The external moisture content of the samples used in the test was 3%, and the set processing capacities were 15 t/(h·m2), 17.5 t/(h·m2), 20.0 t/(h·m2), 22.5 t/(h·m2), and 25 t/(h·m2). As shown in Figure 8A,B, with the increase in processing capacity, the screening efficiency first increased and then decreased, while the total misplaced material content showed the opposite trend of first decreasing and then increasing. The thickness of the material layer on the screen increased with the rise in processing capacity, which made it difficult for fine-grained materials to pass through particle gaps and penetrate the screen. A large number of fine particles moved to the discharge end and became oversize products, leading to a gradual decrease in the effective placement efficiency of fine particles. When the processing capacity was 15 t/(h·m2), the material layer on the screen was thin, which increased the contact probability between some coarse particles (with sizes close to the screen mesh) and the screen surface, thus reducing the effective placement efficiency of coarse particles. When the processing capacity was 17.50 t/(h·m2), the optimal screening efficiency and total misplaced material content were 86.75% and 6.18%, respectively.

Figure 8.

Influence of processing capacity on the rigid–flexible coupled screening performance at the external moisture content of 3% ((A) variation pattern of screening efficiency; (B) variation pattern of misplaced material content).

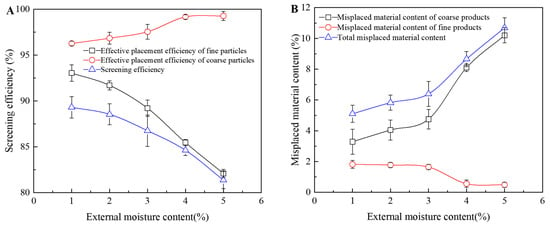

3.2.2. Influence of External Moisture Content on Rigid–Flexible Coupled Screening Efficiency

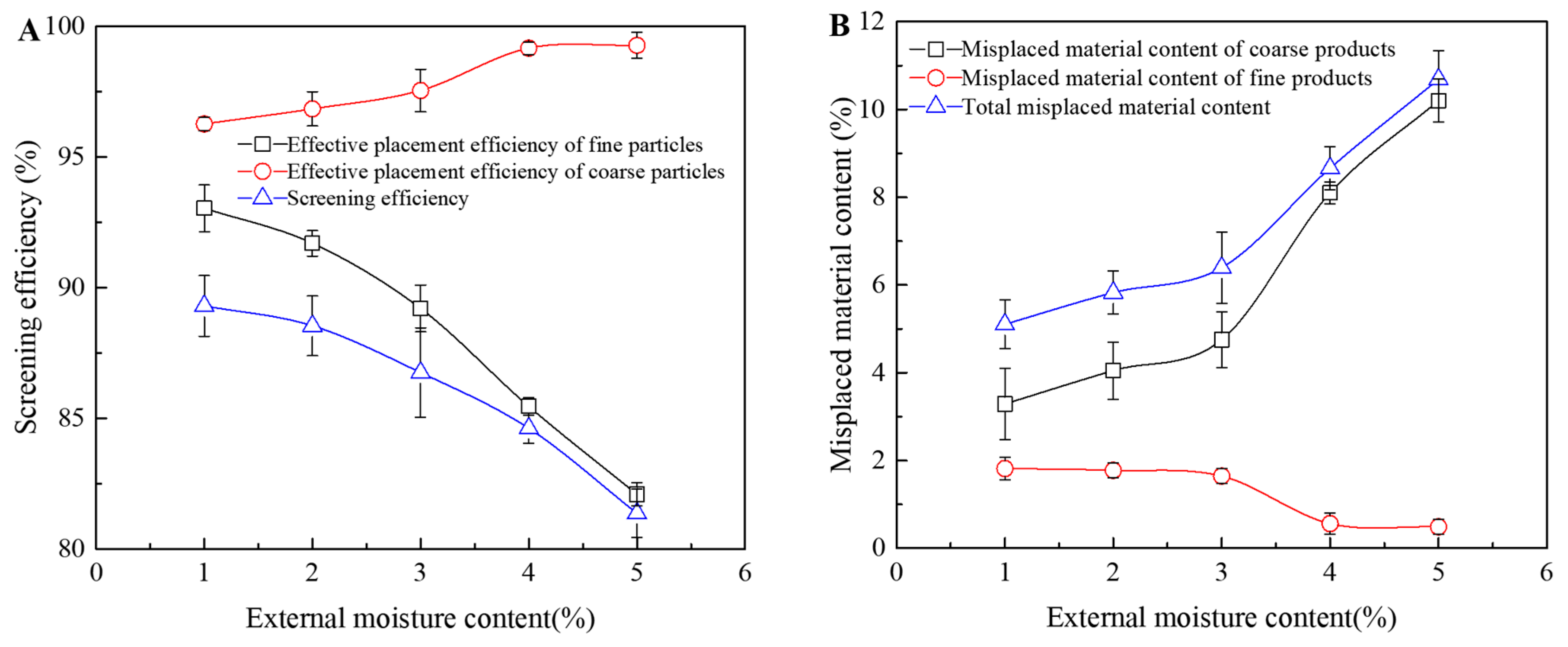

Under the action of moisture, fine-grained ore and slime tend to adhere into agglomerates and attach to the surface of coarse particles, which makes loosening and stratification difficult and causes severe screen surface clogging. For this reason, the variation in the screening effect of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface under different moisture content conditions was investigated to clarify the adaptability of the screen surface to ore with different moisture levels. As shown in Figure 9A,B, when the processing capacity was 17.5 t/(h·m2), with the external moisture content increasing from 1% to 5%, the screening efficiency showed a decreasing trend while the total misplaced material content presented an increasing trend. The screening efficiency ranged from 81.36% to 89.30%, and the total misplaced material content varied from 5.10% to 10.68%. With the increase in external moisture content, the adhesion between the solid and liquid phases was enhanced. A large number of hard-to-screen particles, slime, and fine particles became oversize products, which led to a decrease in the effective placement efficiency of fine particles and an increase in the misplaced material content in coarse particles.

Figure 9.

Influence of moisture content on the rigid–flexible coupled screening performance at a capacity of 17.5 t/(h·m2) ((A) variation pattern of screening efficiency; (B) variation pattern of misplaced material content).

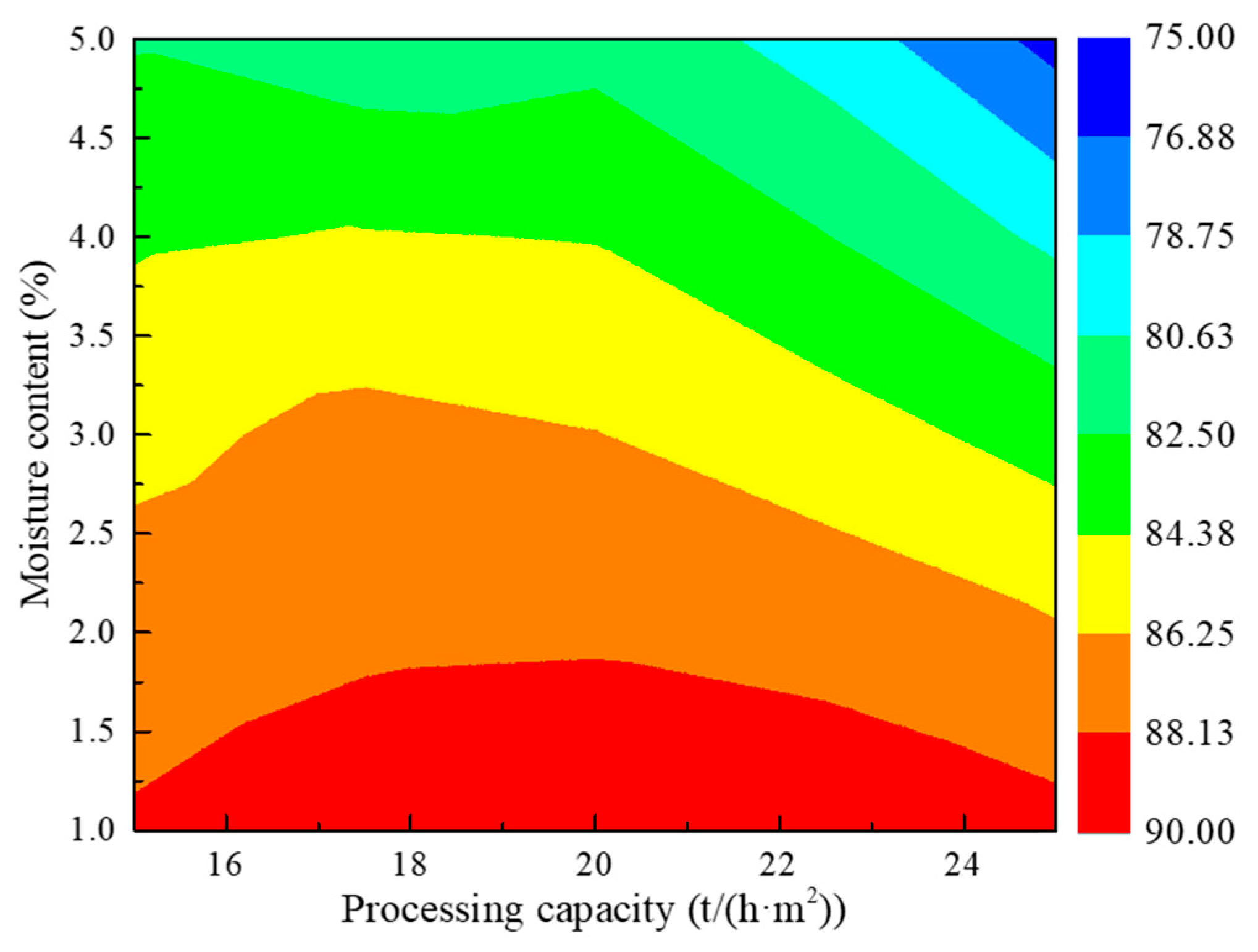

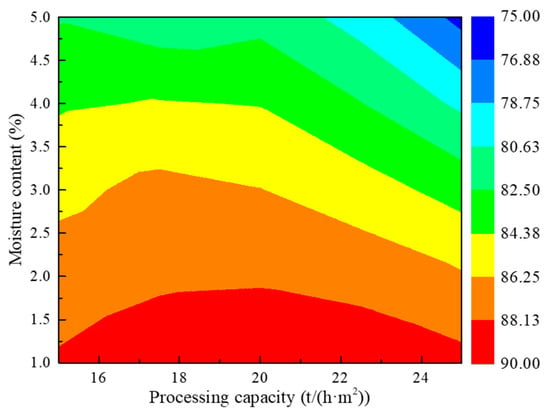

Both processing capacity and external moisture content have a significant impact on the rigid–flexible coupled screening effect. To further clarify the interaction law between the two factors on the screening effect, the influence of external moisture content on screening efficiency under different processing capacity conditions was studied. The isosurface of screening efficiency is shown in Figure 10. By conducting analysis of variance (ANOVA) and fitting on the test data, a quadratic function model between screening efficiency, external moisture content (w), and processing capacity (Q) was established, as shown in Equation (4). The external moisture content and processing capacity synergistically inhibit the screening efficiency. When the processing capacity is relatively high, the moisture has a more significant impact on the screening efficiency; meanwhile, the higher the moisture content, the more obvious the decrease in screening efficiency caused by the increase in processing capacity. To ensure the screening efficiency reaches above 85%, the ore moisture should be controlled below 3%, and the processing capacity should be maintained at 15–22.5 t/(h·m2).

Figure 10.

The interaction effect between moisture content and processing capacity on screening efficiency.

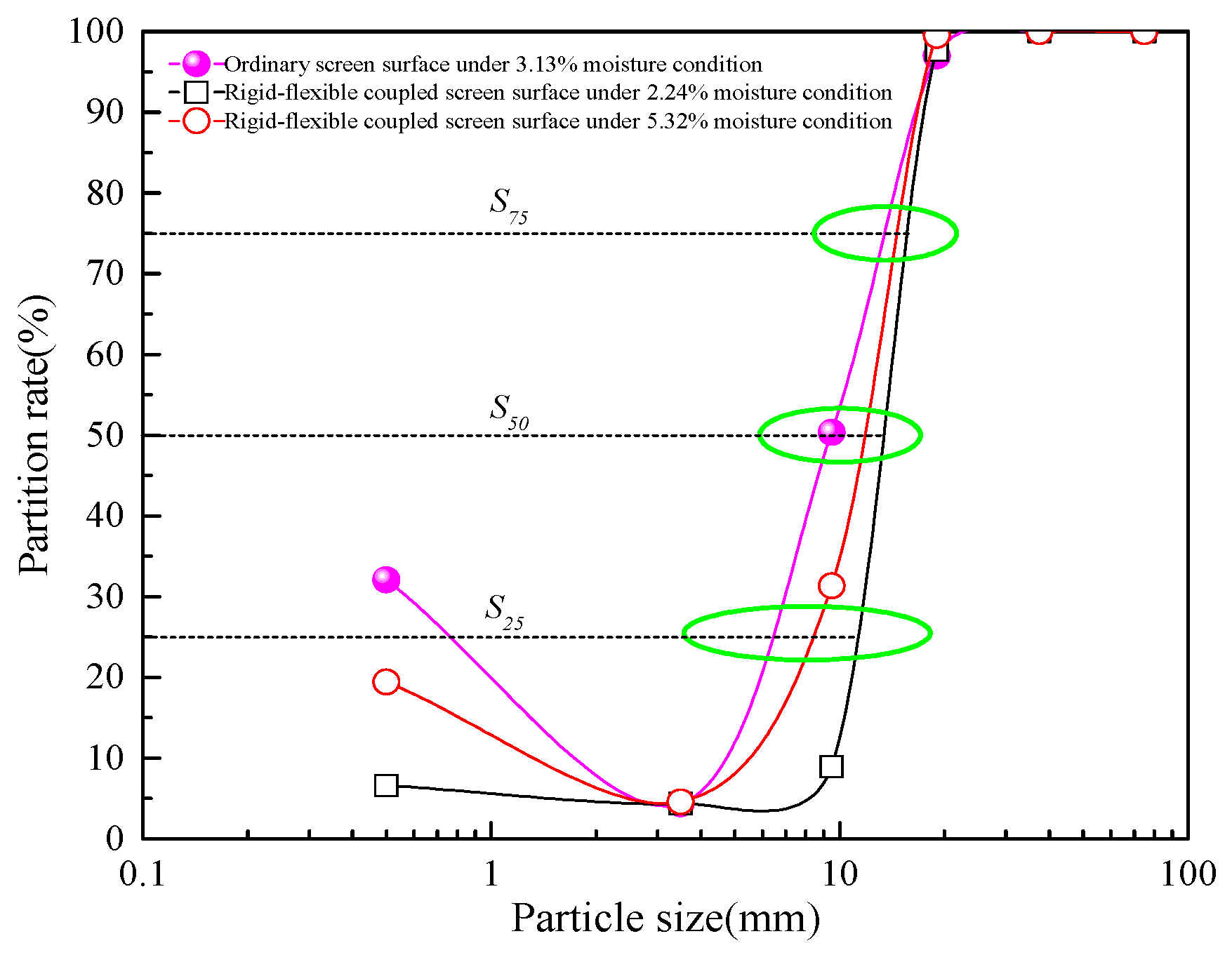

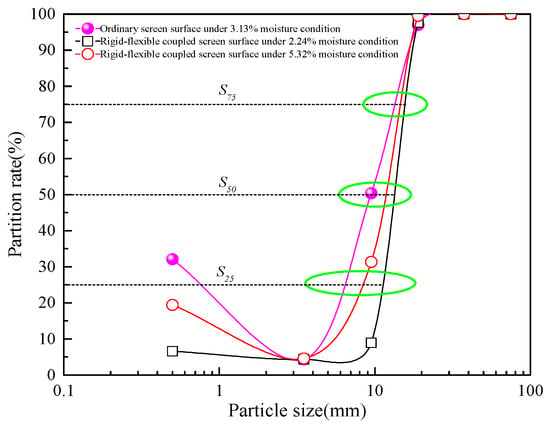

3.2.3. Industrial Performance Evaluation of the Rigid–Flexible Coupled Screen Surface

Combined with the actual production conditions of the mineral processing plant and the properties of raw ore, a process performance evaluation was conducted for the industrial application of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface, and compared with the performance of the ordinary screen surface used on site. The aperture of the ordinary screen surface is 13 × 13 mm. In industrial processing, the moisture content of the ore is influenced by numerous factors. While it can be measured, it cannot be precisely controlled. Industrial trials were conducted using two types of screen surfaces, both under a consistent ore feed rate of 17.5 t/(h·m2). When the external moisture content of the ore was 2.24% and 5.32%, the corresponding screening efficiencies of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface were 93.11% and 82.92%, with total misplaced material contents of 0.87% and 5.71%, respectively. Table 1 presents the particle size distribution of the feed, oversize, and undersize materials for the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface at a moisture content of 2.24%. The actual yield of oversize and undersize products was calculated using the least squares method, based on which the partition curve for the screening process was plotted. The partition curves for other operating conditions were obtained using the same method, as shown in Figure 11. The partition sizes of the ordinary screen surface and the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface under different moisture conditions were 9.53 mm, 13.42 mm, and 11.84 mm, respectively, with separation deviations of 3.78, 1.1, and 3.04, respectively. In addition, according to the variation trend on the left side of the curve, it can be observed that the upward warping trend of the ordinary screen surface is the most significant—this confirms that a large number of fine particles enter the oversize products. In contrast, the upward warping trend of the distribution curve of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface is reduced, indicating a stronger promoting effect on the penetration of fine particles through the screen.

Table 1.

Actual yield and partition rate.

Figure 11.

Variation in the partition curve.

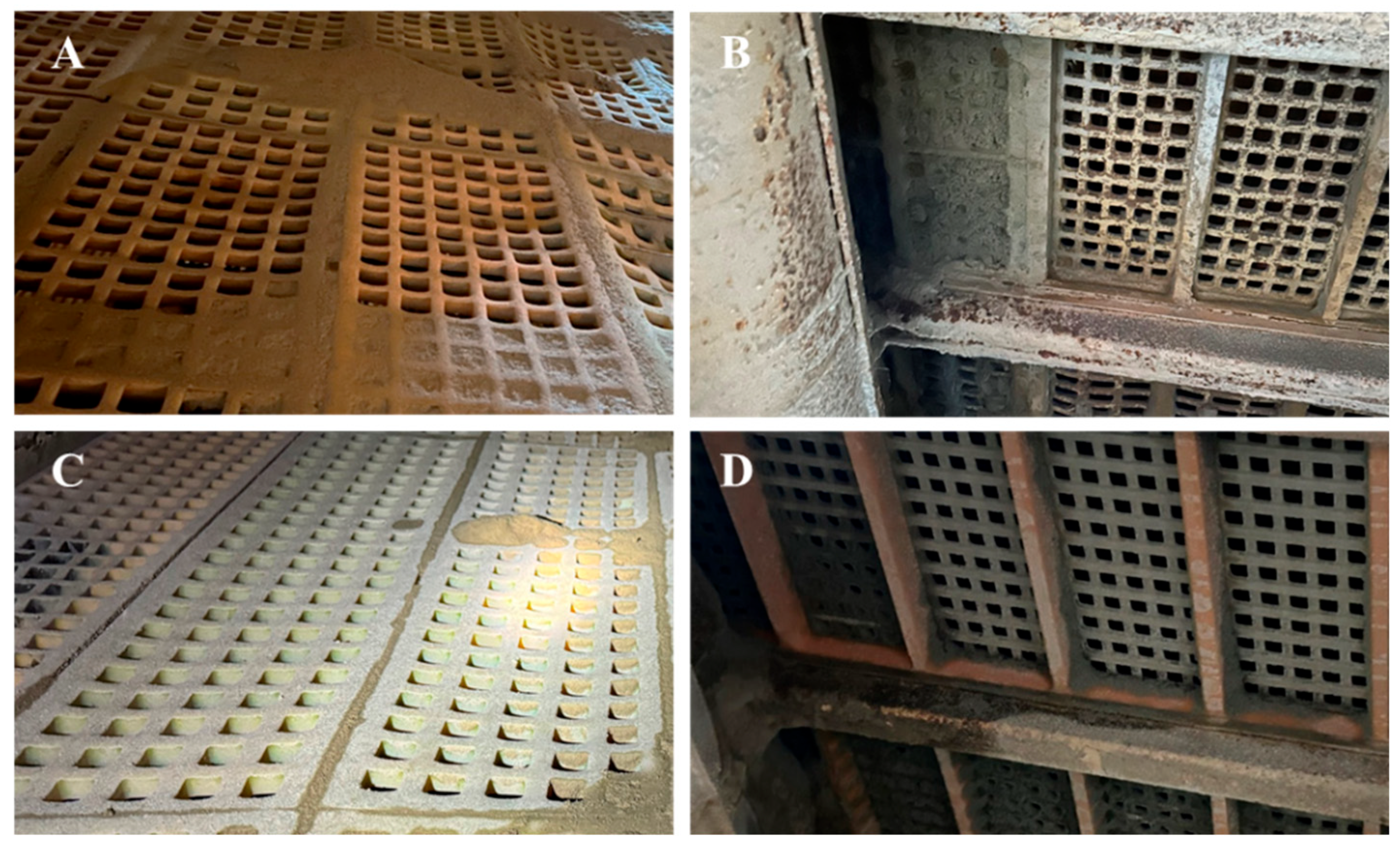

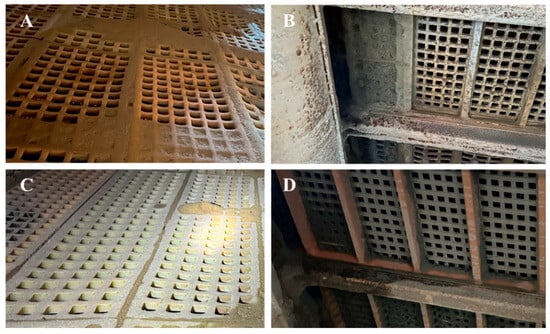

After continuously processing approximately 2500 tons of ore, the hole-clogging condition of the ordinary structured screen surface is shown in Figure 12A,B. Both the upper and lower screen surfaces exhibited obvious hole clogging caused by covering films, with the average hole-clogging rates of a single screen surface at the beam position being 25% and 73%, respectively. After replacing it with the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface, its hole-clogging condition is presented in Figure 12C,D. For the upper screen surface, only slime caking at the beam position was observed, and the clogged area of a single screen surface accounted for 8% to 10% of the open area. For the lower screen surface, the clogged area of a single screen surface accounted for 25% to 32% of the open area.

Figure 12.

Comparison of screen aperture blocking between ordinary and rigid–flexible coupled screen surfaces ((A) The upper ordinary structured screen surface; (B) The lower ordinary structured screen surface; (C) The upper rigid–flexible coupled screen surface; (D) The lower rigid–flexible coupled screen surface).

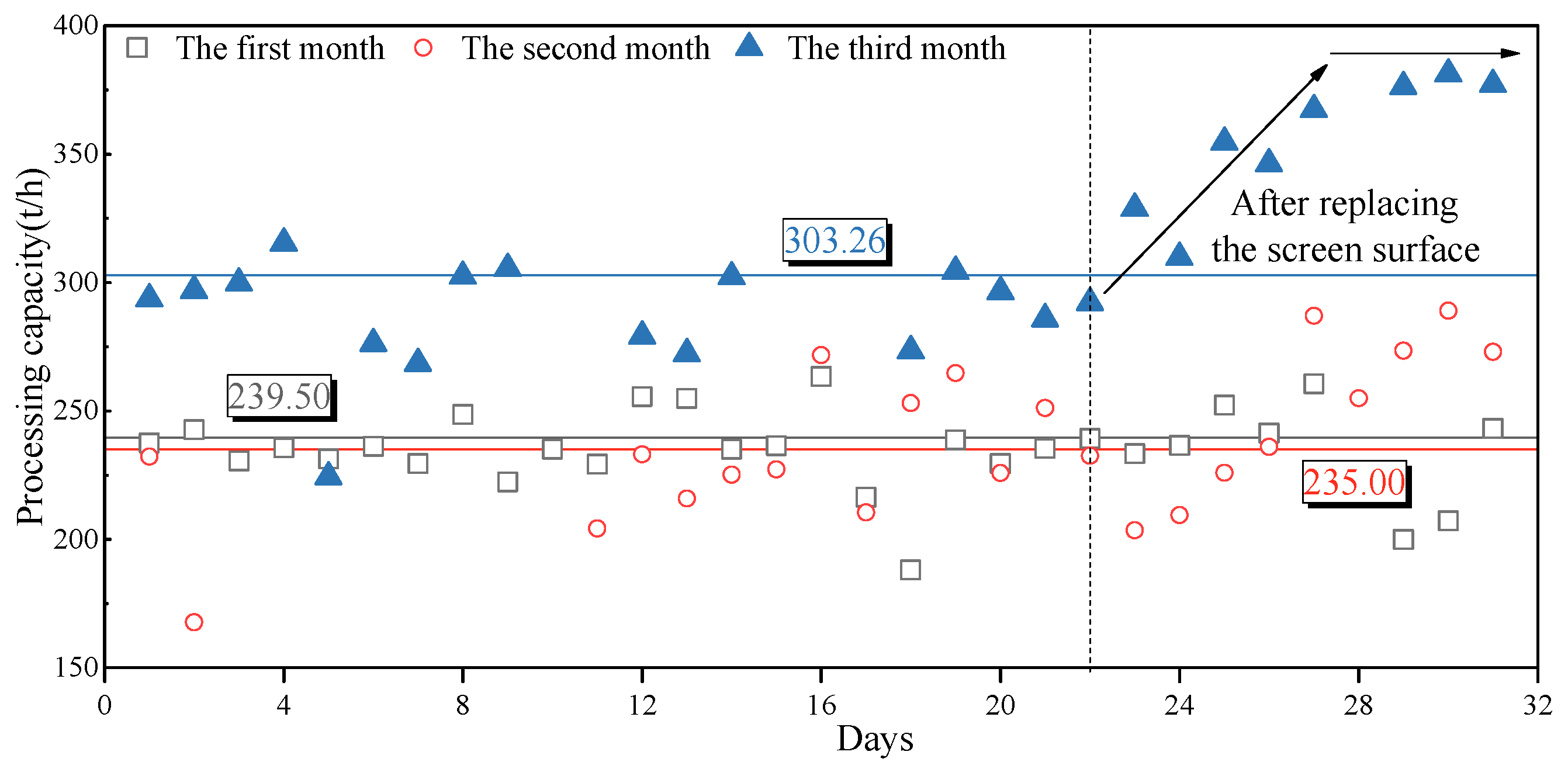

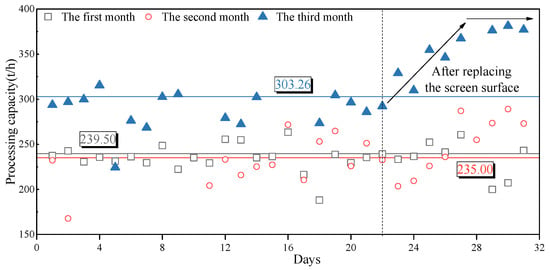

The high-elastic screen mesh area of the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface drives the fragmentation and dispersion of agglomerates in sticky and wet gold ore, increasing the probability of fine-grained ore penetrating the screen. Meanwhile, its high-elastic response promotes the deformation of screen meshes, overcoming screen surface clogging, which can meet the technical requirement of efficient desliming for dry screening of sticky and wet gold ore. The removal rate of fine particles smaller than 6 mm in the oversize product is nearly 91%. Due to the reduction in the content of fine particles and slime, the operation of the subsequent crushing system is improved. The average processing capacity of the crushing section within 3 months was counted, as shown in Figure 13. After replacing with the rigid–flexible coupled screen surface, the processing capacity increased significantly, with an average processing capacity of 303.26 t/h and a maximum processing capacity of 380 t/h. In addition, according to on-site production statistics, the content of sticky and wet fine-grained ore in the feed of the crushing section decreased, avoiding caking of crushed products. The screening effect of the checking screening section was improved by nearly 12%, and the circulating load ratio of the crushing section was reduced by approximately 8%, which effectively ensured the operational stability of the screening and crushing processes.

Figure 13.

The impact of improved screening performance on the crushing operation.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study proposes a rigid–flexible coupled screening method for viscous, moist gold ore. The screen surface demonstrates a vibration intensity significantly greater than that of the screen body, achieving amplification of the input vibration parameters. This enhancement effectively strengthens the fragmentation and dispersion of material agglomerates while simultaneously avoiding the reliability degradation caused by excessive dynamic stress in the screening machinery.

- (2)

- Moisture content and processing capacity synergistically inhibit screening efficiency. A quadratic function model was established to describe the relationship between screening efficiency, moisture content, and processing capacity. When the ore moisture content is below 3% and the processing capacity ranges from 15 to 22.5 t/(h·m2), the screening efficiency can be maintained above 85%. The rigid–flexible coupled screen surface achieves a desliming efficiency of 91%, reducing the slime content in subsequent crushing stages. Furthermore, the closed-circuit checking screening efficiency is synchronously improved by nearly 12%, and the crushing return ore ratio is reduced by approximately 8%, thereby ensuring operational stability in both the screening and crushing processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; Methodology, J.L.; Software, X.F.; Validation, N.X., Z.H., T.G., X.F., H.G., J.L., X.S., W.S. and M.P.; Formal analysis, T.G.; Investigation, N.X., Z.H., T.G., X.F., H.G., J.L., X.S., W.S. and M.P.; Data curation, N.X., Z.H. and T.G.; Writing—original draft, N.X.; Writing—review & editing, M.P.; Visualization, X.F. and H.G.; Supervision, X.S.; Project administration, Z.H.; Funding acquisition, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Industrial development projects] grant number [gx2023004] And The APC was funded by [China University of Mining and Technology].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors N.X., Z.H., T.G., X.F., H.G., J.L., X.S. were employed by the company Shandong Linglong Gold Mining Co., Ltd., author W.S. was employed by the company Jiangsu Hewa Screening Product Co., Ltd., the remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cai, M.; Li, P.; Tan, W.; Ren, F. Key engineering technologies to achieve green, intelligent, and sustainable development of deep metal mines in China. Engineering 2021, 7, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Jiang, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Feng, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C. A review on the advanced design techniques and methods of vibrating screen for coal preparation. Powder Technol. 2019, 347, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hou, X.; Duan, C.; Mao, P.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, J.; Pan, M.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, H. Dynamic model of the flip-flow screen-penetration process and influence mechanism of multiple parameters. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Yuan, J.; Pan, M.; Huang, T.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, S.; Lu, J. Variable elliptical vibrating screen: Particles kinematics and industrial application. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, M.N.; Galery, R.; Mazzinghy, D.B. A review of process models for wet fine classification with high frequency screens. Powder Technol. 2021, 394, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qiao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Duan, C.; Luo, Z.; Cai, L.; Wang, S.; Pan, M. Time evolution of kinematic characteristics of variable-amplitude equal-thickness screen and material distribution during screening process. Powder Technol. 2018, 336, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, R.; Feng, Y.; Huang, T.; Duan, C.; Jiang, H. In-depth analysis of the dynamic features and screening performance of high-elasticity projection vibrating screen. Miner. Eng. 2025, 232, 109558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Xu, T.; Lu, J.; Duan, C.; Shi, W.; Huang, L.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, J.; Qiao, J.; Jiang, H. Enhanced vibration dewatering to facilitate efficient disposal process for waste fine flotation tailings. Miner. Eng. 2025, 223, 109177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Huang, L.; Jiang, H.; Wen, P.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, C.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; et al. Kinematics of elastic screen surface and elimination mechanism of plugging during dry deep screening of moist coal. Powder Technol. 2019, 345, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Guo, P.; Li, S.; Pan, M.; Duan, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, W.; Xu, T.; Shi, W. Investigation on enhancing classification of moist material by variable vibration intensity elastic screening. Adv. Powder Technol. 2024, 35, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baragetti, S. Innovative structural solution for heavy loaded vibrating screens. Miner. Eng. 2015, 84, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wang, W.; Pan, J.; Mao, P.; Zhang, S.; Duan, C. Optimization of flip-flow screen plate based on DEM-FEM coupling model and screening performance of fine minerals. Miner. Eng. 2024, 211, 108694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, C.; Shen, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, S. Kinematics characteristics of the flip-flow screen with a crankshaft-link structure and screening analysis for moist coal. Powder Technol. 2021, 394, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Gong, S.; Pang, K.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, D.; Xu, N. Stability analysis of the screening process of a vibrating flip-flow screen. Miner. Eng. 2021, 167, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Niu, L.; Gu, C.; Wang, Y. Vibration characteristics of an inclined flip-flow screen panel in banana flip-flow screens. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 411, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.Q.; Liu, C.S.; Wu, J.D.; Wang, Z. Influence of tensional amount on dynamic parameters of unilateral driven flip-flow screen surface. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Zou, M.; Qiu, W. Numerical simulation of dynamic characteristics and parameter optimization of flip-flow screen surface. J. Cent. South Univ. 2019, 50, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Lu, J.; Wang, C.; Yuan, J.; Hou, X.; Pan, M.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, J.; Duan, C.; Dombon, E.; et al. Study on screening probability model and particle-size effect of flip-flow screen. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yu, S.; Pan, M.; Duan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Song, B. Effect of excitation parameters on motion characteristics and classification performance of rigid-flexible coupled elastic screen surface for moist coal. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Duan, C.; Tang, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.; Kinematics, P.W. of a novel screen surface and parameter optimization for steam coal classification. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.