Abstract

Human exposure to persistent organic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) and brominated flame retardants (BFR), including both legacy and emerging compounds, remains a concern due to their bioaccumulative nature and potential health effects. Comprehensive analytical methods are necessary to monitor these substances in complex biological matrices, such as human serum. A gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method was developed for the simultaneous determination of 44 analytes, encompassing PCB and a broad spectrum of BFR with diverse physicochemical properties. The extraction procedure and GC-MS parameters were optimized using a design of experiments approach to maximize performance while minimizing analysis time. The method demonstrated high sensitivity, precision, and accuracy, thereby meeting internationally recognized validation criteria for biomonitoring applications. To further ensure analytical reliability, compound confirmation was achieved using gas chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry, providing enhanced selectivity and confidence in identification, particularly for low-level analytes. Key advantages of the method include its applicability to analytes with significantly different chemical behaviors and its capacity to quantify a large number of target compounds simultaneously. This makes it a powerful tool for assessing human exposure to both regulated and emerging halogenated contaminants.

1. Introduction

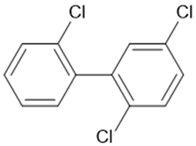

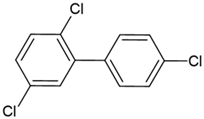

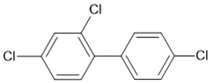

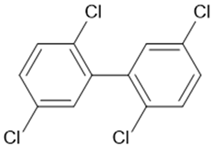

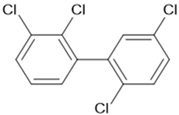

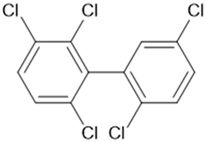

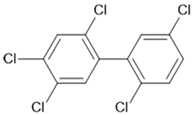

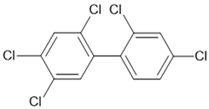

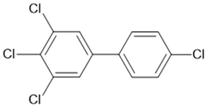

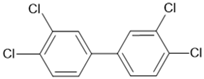

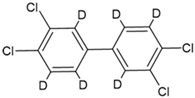

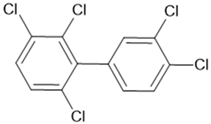

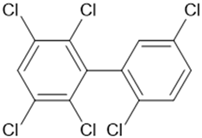

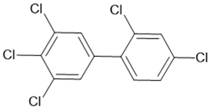

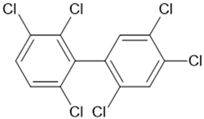

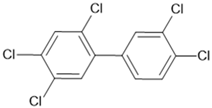

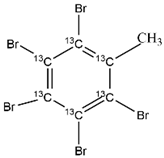

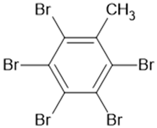

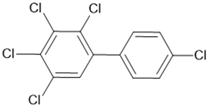

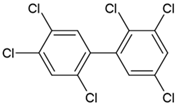

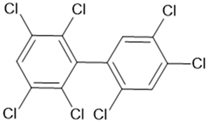

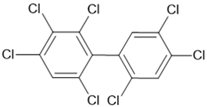

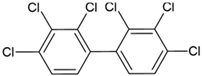

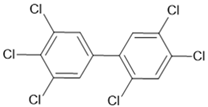

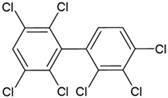

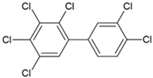

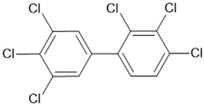

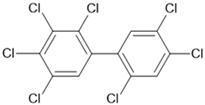

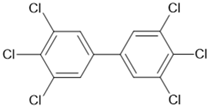

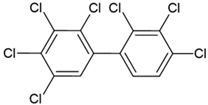

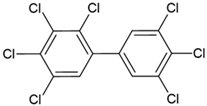

Air pollution, described by the World Health Organization as a “silent killer”, is of great concern, but its effects are not easy to measure [1]. Persistent organic pollutants (POP) are long-lived toxic chemicals. Lipophilic POP affect human health worldwide for generations by accumulating in fatty tissues and fluids [2]. POP are chemicals of great concern due to their persistent presence in the environment and humans. The main categories of POP include organochlorine pesticides (OCP), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) [3]. Globally, increasing evidence links these compounds to various non-cancer and cancer-related health effects. Among many adverse health effects, there is growing concern about possible links between serum POP and reproductive health, infant wheezing, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DMT2), liver cancer, breast cancer, and, recently, neurological outcomes, including Parkinson’s disease, neurotoxicity, and other neurodegenerative disorders [4,5,6,7]. PCB are a class of persistent environmental pollutants that were historically used in various industrial applications, including dielectric fluids and plasticizers, until their production was banned by the Stockholm Convention in 2001, with subsequent amendments in 2008 and 2014 [8]. Despite this ban, PCB are still present in older materials such as sealants and fluorescent light ballasts, contributing to ongoing indoor contamination and exposure. Background environmental concentrations typically range from 1 to 100 pg/m3 in air and 100 to 1000 pg/g in soil [9]. PCB comprise 209 congeners, classified as either dioxin-like (DL) or non-dioxin-like (NDL), depending on their chlorine substitution pattern and ability to bind the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) [9]. PCB are included among the initial “Dirty Dozen” POP [9,10] and have been classified as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1A) [11]. They have been associated with a range of toxic effects, including carcinogenesis, neurotoxicity, and endocrine disruption [12]. Notably, NDL PCB represent the majority of congeners detected in human serum studies [9].

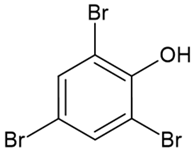

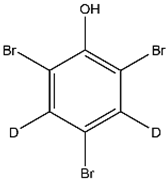

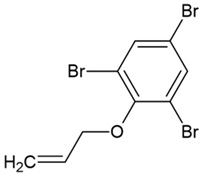

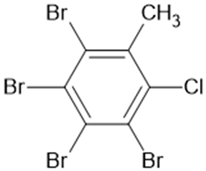

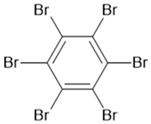

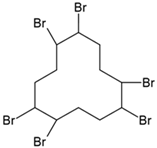

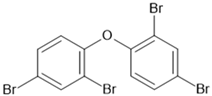

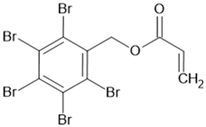

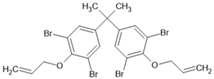

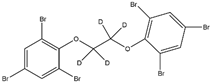

The widespread use of plastic consumer goods led to the introduction of flame retardants (FR), chemicals designed to prevent or slow the spread of fire. Among the most used household materials were phosphorus- and halogen-based FR, particularly brominated flame retardants (BFR). Regulated BFR such as polybrominated biphenyls (PBB), PBDE, and hexabromocyclododecane (HBCDD), used in consumer products as “commercial mixtures” [13], have raised concerns due to their toxicity and persistence. In response, novel BFR (NBFR), including Decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE), 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP), 1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane (BTBPE), Hexabromobenzene (HBB), Pentabromotoluene (PBT), have been marketed [14]. Like PBDE, NBFR are semi-volatile and lipophilic, allowing them to travel long distances and accumulate in the environment and organisms [14]. However, their safety remains unclear, with evidence suggesting they may cross the blood–brain barrier and pose neurotoxic, carcinogenic, and endocrine-related risks [15,16].

Despite numerous efforts in method development, most existing protocols focus on specific contaminant classes, often requiring separate extraction and purification steps for PCB and NBFR, due to their differing physicochemical properties [16]. This leads to increased sample volume requirements, longer analysis times, and inconsistent recovery across compound classes. Additionally, challenges remain in achieving adequate chromatographic resolution for closely eluting congeners (e.g., PCB 128 and PCB 167) and minimizing matrix effects in complex biological matrices such as human serum. Few studies have addressed the co-extraction of PCB and NBFR using a unified protocol applicable to biomonitoring, and those that do often rely on multi-step workflows or target limited analyte panels [16]. Therefore, the development of a simplified, high-throughput method capable of simultaneously extracting and quantifying a broad spectrum of halogenated contaminants is crucial for advancing human exposure assessment.

Human biomonitoring (HBM) relies on internal dose biomarkers, typically measured in serum, to assess exposure [17]. These compounds enter the body via ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact and circulate in the blood [1]. Still, their low concentration and the complexity of serum make their accurate quantification analytically challenging.

Both for PCB and NBFR, multistage liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) and a subsequent sophisticated purification step were used [18,19]. New pretreatment techniques have been developed for environmental contaminant analysis, such as the QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe) approach, solid-phase extraction (SPE) [16,20,21] or two pretreatment methods based on the QuEChERS approach and SPE simultaneously [22]. For instrumental analysis, the most frequently used detection techniques of NBFR were developed on GC-NCI-MS (Gas chromatography–negative chemical ionization–mass spectrometry) or GC-EI-MS/MS (Gas chromatography–electron impact–tandem mass spectrometry) [23]. GC-EI-MS is an ideal technique for PCB.

Analytical procedures become more complex when identifying and quantifying multiple pollutants from different classes with widely varying chemical and physical properties. Here, we developed and validated a novel SPE-GC-EI-MS method for the simultaneous analysis of PCB and NBFR in human serum. Design of Experiment (DoE) was used to optimize the method, focusing on key aspects such as chromatographic separation, method sensitivity, and the extraction process for contaminants. GC-HR-MS (Gas chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry) was used to confirm peak identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Water of HPLC-MS grade (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) was produced using the depurative system Milli-Q Synthesis A 10 (Millipore, Molsheim, France). Hexane, dichloromethane (DCM), acetone, and acetonitrile (ACN), all of HPLC-grade, were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Isooctane and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Milano, Italy). Supelclean envi-florisil (1 g/6 mL) and supelclean LC-Si (1 g/6 mL) SPE materials and SRM 1957 human serum were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). The standard reference material SRM 1957, certified by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD, USA), was used.

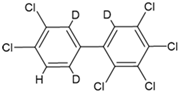

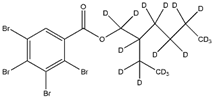

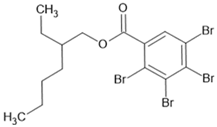

2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate, 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate-d17, Bis(2-ethylhexyl)-3,4,5,6-tetrabromo-phthalate, hexabromobenzene, pentabromobenzylacrylate, 1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy) ethane, 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromotoluene-13C6, 2,4,6-Tribromophenol-3,5-d2, 1,2-bis (2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane-d4, PCB Internal Standards Mixture 104 (2,3,3′,4,4′,5-Hexachlorobiphenyl-2′,6,6′-d3 and 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl-d6) 10 µg/mL in n-Hexane were purchased from LGC Standards S.R.L (Milano, Italy). Standards of 2,4,6-tribromophenol, 2,2-Bis(4-allyloxy-3,5-dibromophenyl) propane were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). Tetrabromo-o-chlorotoluene, 2,2′4,4′-Tetrabromodiphenyl Ether, and a total of 32 PCB were purchased from Ultra Scientific (Bologna, Italy). 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromotoluene, Allyl 2,4,6-tribromophenyl ether, 1,2,5,6,9,10-Hexabromocyclododecane, alachlor, atrazine were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Standard Solutions

Single stock solutions (1 mg/mL) of 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate, hexabromobenzene, 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromotoluene, 2,4,6-Tribromophenol, Allyl 2,4,6-tribromophenyl ether, pentabromobenzylacrylate, Tetrabromophthalic anhydride, 1,2-bis (2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane, 2,2-Bis(4-allyloxy-3,5-dibromophenyl)propane, 2,2-Bis [3,5-dibromo-4-(2,3-dibromopropoxy)phenyl]propane, 1,2,5,6,9,10-Hexabromocyclododecane, Tetrabromo-o-chlorotoluene were prepared in toluene and stored until use at −80 °C.

Single stock solutions (1 mg/mL) of PCB were prepared in isooctane and stored until use at −80 °C. Stock solutions of atrazine and alachlor were prepared in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and stored until use at −80 °C. 2,3,4,5-Pentabromo-6-chlorocyclohexane was already available at a concentration of 100 µg/mL in isooctane.

Standard solutions used for method validation were obtained by diluting stock solutions in isooctane.

Spiked sample solutions (QCs) were used for optimizing PCB and NBFR extraction procedure and were obtained by adding diluted stock solutions in the range 0.5–500 ppb to fetal bovine serum sample. For preparation, see Section 2.4.

2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate-d17, 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromotoluene-13C6, 2,4,6-Tribromophenol-3,5-d2, 1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy) ethane-d4 were used as internal standards (IS) for NBFR quantification at a concentration of 10MQL. The IS were selected based on their retention-time proximity to the target analytes. For PCB quantification, a mixture of 2,3,3′,4,4′,5-Hexachlorobiphenyl-2′,6,6′-d3 and 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl-d6 at a concentration of 10MQL was used. Table S1 provides a detailed overview of IS used for each compound.

2.3. Design of Experiment Method

DoE [24] is a well-known chemometric approach that allows us to optimize the parameters of a process with a reduced number of experiments. The experiments are chosen by selecting the most important variables to be kept into account for the process and the operative limits, called levels (minimum and maximum), between which these variables must be evaluated. The performed experiments are those exploring each combination of the levels of all variables. In some cases, a central level between the two limits is also explored. In this way, for a V number of variables and L levels, the number of experiments to be performed is LV. If all the experiments are performed, the DoE is called full-factorial. The regions that are not explored directly by the DoE experiments are estimated by a multiple linear regression (MLR) using the combinations of the levels as the dependent variables and the results of the experiments (responses) as the independent one(s). In this way, it is possible both to evaluate in which region of the experimental domain the response is optimized, and to evaluate which variables are most influential on the response. This is obtained by considering the p-values of the regression coefficient: highly influential variables have p-values below the chosen significance level (generally 0.05), while non-influential variables have p-values higher than the significance level.

If the number of experiments considering all the combinations of the levels is too high, it is possible to reduce it using the D-optimal approach, whose detailed computation is described elsewhere [24]. The D-optimal splits the matrix composed by the combination of the levels into several subgroups (also hundreds or thousands, depending on the dimension of the starting matrix), considering different numbers of experiments (nj, where j indicates different subgroups for each n). For each n, it calculates a parameter (M) [24] and the subgroup corresponding to the highest M is the one considered as most informative and chosen instead of the full-factorial DoE.

2.4. Instrumental Conditions

2.4.1. GC-EI-MS Condition

GC was performed using an Agilent 8890 GC System, equipped with an autosampler PAL RSI 120, coupled to a single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 5977B, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an electron impact source. The analytical separation was achieved using an EquityTM-5 FUSED SILICA Capillary Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Merk Life Science, Milano, Italy) within 47.5 min. Injection volume was 2 μL in pulsed splitless mode. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a column flow set at 1.4 mL/min during the chromatographic run, while the injector was held at 280 °C. GC-MS assay was optimized by using DoE as reported in Section 2.4. The final conditions are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

GC-MS parameters.

Table 2.

Oven temperature ramp.

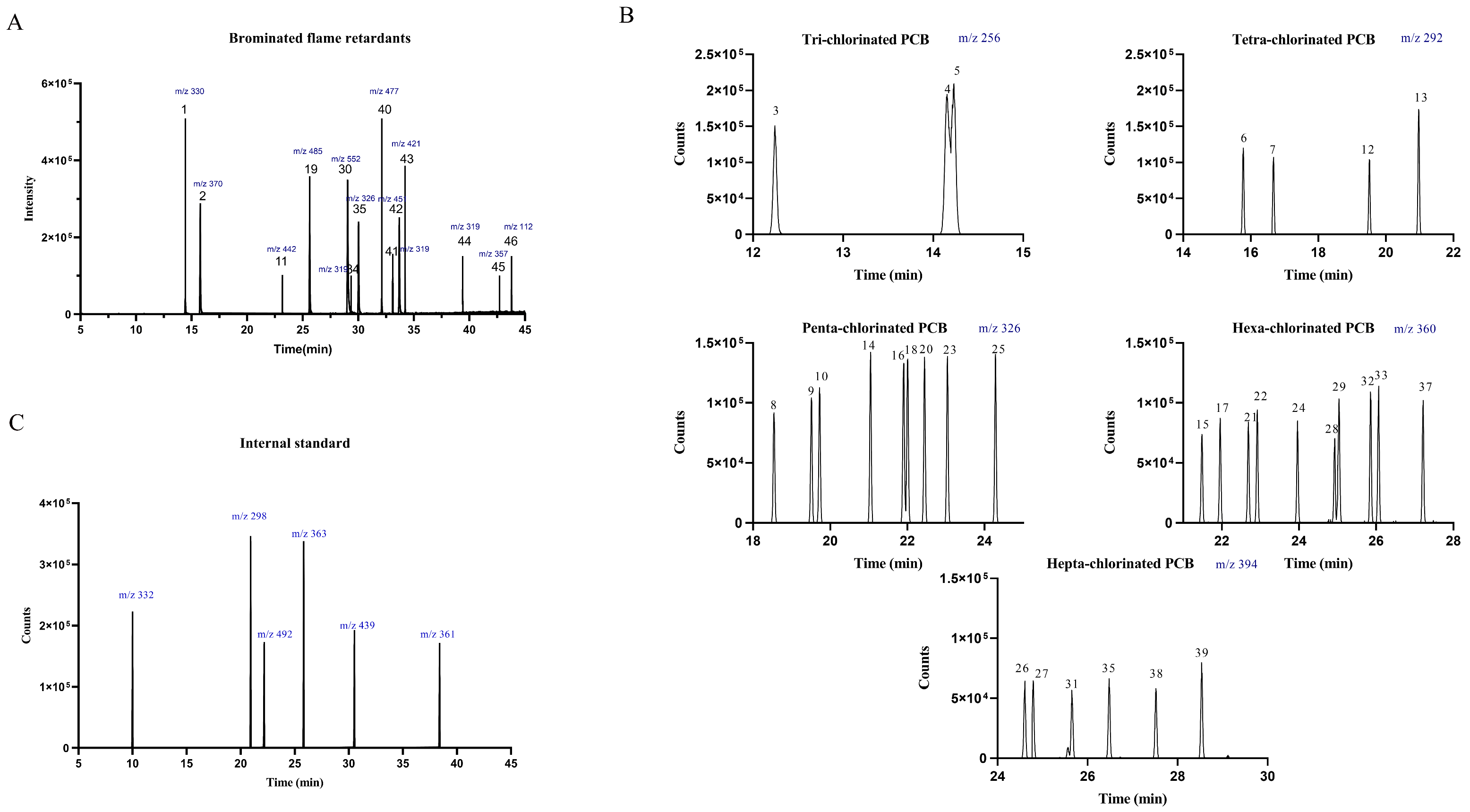

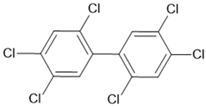

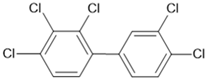

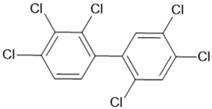

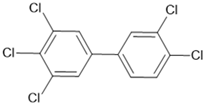

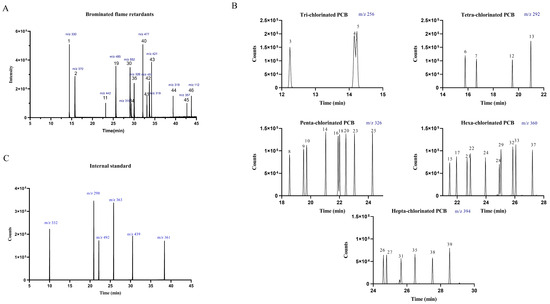

MS analysis was performed splitting the retention time range into four segments in single ion monitoring (SIM) mode, selecting the ion after a GC/EI full scan screening. Table 3 resumes the single ion monitored and Table S2 in Supplementary Information resumes MS parameters. Figure 1 shows the chromatograms for BFR and PCB.

Table 3.

PCB and NBFR included in the method.

Figure 1.

Chromatograms obtained for all the analytes: (A) BFR: 2,4,6-Tribromophenol (1), Allyl 2,4,6-tribromophenyl ether (2), Tetrabromo-o-chlorotoluene (11), 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromotoluene (19), Hexabromobenzene (30), 2,2′,4,4′-Tetrabromo diphenyl ether (36), Pentabromobenzylacrylate (40), 2,2-Bis(4-allyloxy-3,5-dibromophenyl)propane (41), 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate (43), 1,2-bis (2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane (45), Bis (2-ethylhexyl)-3,4,5,6-tetrabromo-phthalate (46), Hexabromocyclododecane (α,β,γ) (34,42,44); (B) PCB: PCB-18 (3), PCB-31 (4), PCB-28 (5), PCB-52 (6), PCB-44 (7), PCB-95 (8), PCB-101 (9), PCB-99 (10), PCB-81 (12), PCB-77 (13), PCB-110 (14), PCB-151 (15), PCB-123 (16), PCB-149 (17), PCB-118 (18), PCB-114 (20), PCB-146 (21), PCB-153 (22), PCB-105 (23), PCB-138 (24), PCB-126 (25), PCB-187 (26), PCB-183 (27), PCB-128 (28), PCB-167 (29), PCB-177 (31), PCB-156 (32), PCB-157 (33), PCB-180 (35), PCB-169 (37), PCB-170 (38), PCB-189 (39); (C) internal standard: 2,4,6-Tribromophenol-3,5-d2 (m/z 332), PCB 77-d6 (m/z 298), 2,3,4,5,6-Pentabromo-toluene-13C6 (m/z 492), PCB 156-d3 (m/z 363), 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate-d17 (m/z 439), 1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy) ethane-d4 (m/z 361).

2.4.2. GC-EI-HRMS Condition

GC-EI-HRMS was performed using Orbitrap Exploris (Thermo Fisher, Milano, Italy) with an electron impact source. The analytical separation was achieved using an EquityTM-5 FUSED SILICA Capillary Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Merk Life Science, Milano, Italy). Injection volume was 2 μL. The carrier gas flow in the column during the chromatographic run was set at 1.4 mL/min, the injector was held at a temperature of 280 °C. Acquisition was performed in full scan mode from 60 m/z to 800 m/z with a resolution of 60,000 at 200 m/z.

2.5. Sample Extraction

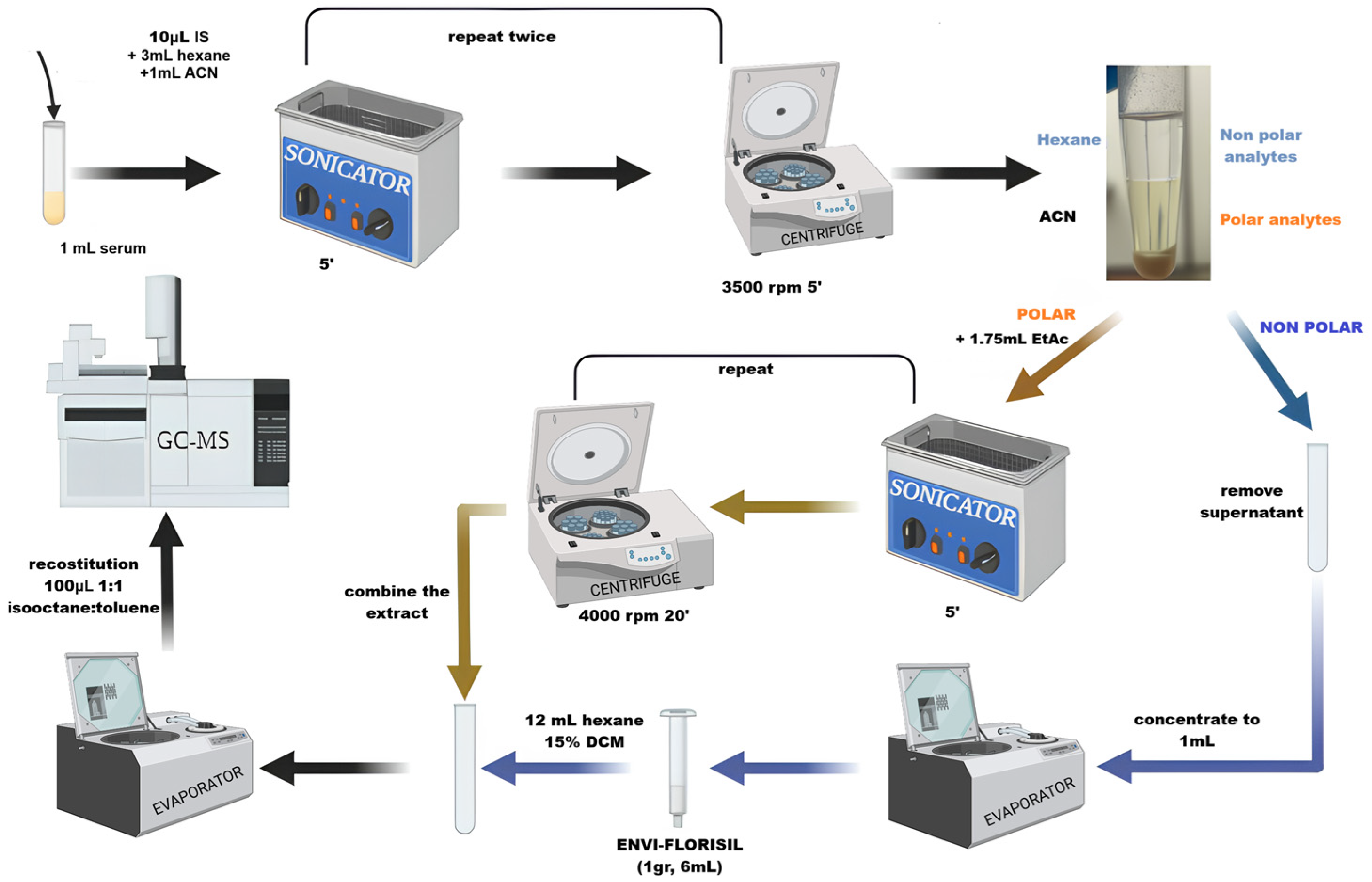

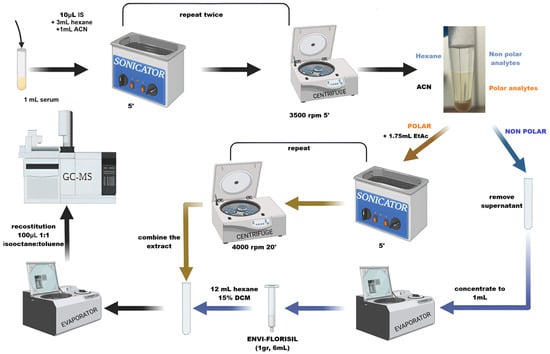

The optimization was performed by using a DoE, as reported in Section 2.7. The optimized extraction procedure reported in Figure 2 offered the best compromise between recoveries, limit of detection, and matrix effect.

Figure 2.

Extraction procedure for serum sample (created with BioRender.com).

Aliquots of 1 mL serum were transferred into a centrifuge tube and stored at −20 °C until sample clean-up. The extraction procedure was as follows (Figure 2):

- (1)

- Aliquot was thawed, 10 μL of IS (at 10 MQL concentration) was added, and the freeze-dried sample was added with 3 mL of hexane and 1 mL of ACN for protein precipitation. The sample was sonicated for 5 min, vortexed for 2 min, and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min. Three identical extractions were performed, and the supernatants were merged. The hexane fractions were separated and concentrated to 1 mL with N2.

- (2)

- SPE was performed on the first fraction containing hexane by using SupercleanTM ENVI-Florisil SPE Tube cartridge (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The cartridge was conditioned with 8 mL of DCM/acetone 1:1 and 2 mL of hexane, sample was eluted with 12 mL of 15%DCM in hexane and dried under a gentle stream of N2.

- (3)

- The polar fraction, after hexane extraction, was added with 1.75 mL of EtAC, sonicated for 5 min, vortexed for 2 min, and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatants, obtained from three identical replicated extractions, were collected and dried.

- (4)

- EtAC extract was reconstituted in 400 μL of 1:1 isooctane/toluene mixture and used to reconstitute the dryness hexane extract.

- (5)

- After dryness, final 100 μL of 1:1 isooctane/toluene was used to reconstitute the sample.

2.6. Optimization of GC-MS Assay

DoE approach was employed to optimize the key parameters affecting GC-MS performance. Considering the literature, all aspects of the chromatographic separation for a specific phase and column dimension are influenced by GC parameters such as initial oven temperature and oven ramp rate [25]. Moreover, to reduce analyte loss and achieve lower detection limits, we used pulsed splitless injection mode [26,27]. Thus, the parameters to optimize were chosen among those mainly affecting resolution and method sensitivity, together with their minimum and maxima values (Table 4):

Table 4.

GC-MS parameters to optimize in experimental design.

Injector and detector temperatures were not included because they have to be sufficient for the respective vaporization and detection of the compounds [25].

The following responses were considered:

- Resolution between PCB 128 and PCB 167.

- Method sensitivity and peak shape: peak area/full width at half maximum (A/FWHM).

The relative influence of these factors on the analytical response was studied using a D-optimal design [28], which enabled the identification of parameters with the greatest influence with a reduced number of experiments. In this initial design, the quadratic terms or the interactions between the temperature programming parameters and the injection mode parameters were not considered, as they are not directly related.

A total of 58 runs and 5 replicates were selected to balance design quality and information gain, ensuring sufficient degrees of freedom for statistical analysis. Table S3 reports the selected experiments for the D-optimal design.

A second D-optimal design was performed to optimize those variables showing a statistical significance in the first model, by including also all higher-order terms. In total, 37 experiments were performed (29 experiments, 5 replicates, and 3 replicates of the central point to validate the model). Table 5 summarizes the used conditions. Figure S1 reports the normalized determinant of the information matrix, and Table S4 reports the selected experiment.

Table 5.

GC-MS parameters to optimize in the second experimental design.

All chemometric elaborations were carried out by means of R-based software CAT (Chemometric Agile Tool, R version 3.1.2, 2014-10-31) [29].

2.7. Optimization Extraction Procedures

In preliminary experiments, the recovery and matrix effect of two commonly used SPE cartridges were firstly evaluated: LC-Si and LC-Florisil [16,30,31,32]. Following the procedures reported in the literature, we tested the two cartridges both in series and separately. LC-Florisil proved to give the best results without having to be used with LC-Si. We also performed extractions with various solvents including hexane, EtAC, and DCM. However, the use of only one solvent for extraction was not possible due to the physicochemical differences between the analytes investigated. A full-factorial design was constructed with a total of 23 experiments (18 experiments and 5 replicates) at 10 MQL concentration level to maximize analyte recoveries (Rec%) (Equation (1)).

Rec(%) = (Areapre-spike/Areapost-spike) × 100

The parameters to be optimized in this case (Table 6) were chosen based on previously independent experiments.

Table 6.

Parameters related to the extraction process optimized by the experimental design.

2.8. Method Validation

2.8.1. D-Optimal Design Validation

The validation of D-optimal model was performed by comparing the response variable predicted by the model at the optimum point of the response surfaces with that obtained experimentally under the working conditions suggested by the model.

2.8.2. Analytical Method Validation

For each analyte, method performance was evaluated by determining retention time (RT), recovery, accuracy, precision (expressed as intra- and inter-day repeatability), linearity, method detection limits (MDLs), and method quantification limits (MQLs).

Selectivity was evaluated by comparing the chromatograms obtained from standards, samples, QCs, and blank injection (i.e., a serum sample not fortified and extracted). In addition, selectivity was also evaluated based on methods reported in the literature regarding mass spectrometer conditions [33]. In particular, for PCB congeners, the m/z and m/z + 2 ions of the two isotopes 35Cl and 37Cl were monitored in SIM mode.

Calibration curve parameters were obtained by plotting the peak area ratio between analyte and IS for each standard solution against theoretical concentration by linear least squares regression analysis. Linearity was assessed via six-point calibration curves in isooctane obtained by diluting stock solution in the range 0.5–50 ng/mL for PCB and 10–500 ng/mL for BFR, each containing each IS (fixed concentration 10 MQL).

MDL and MQL were determined in the samples spiked before the extraction (n = 3) and considered as the minimum detectable amount of analyte with signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 3 and 10, respectively.

The overall accuracy and precision of the method were calculated intra-day (n = 3) and inter-day (n = 9) from three repeated injections of QCs at three different concentrations and extracted. Low concentration was the MQL, medium concentration was 10 MQL, and high concentration was 100 MQL for each analyte.

Accuracy was calculated following Equation (2):

where STDm and STDs indicate mean measured concentration and theoretical (spiked) concentration, respectively.

bias(%) = (STDm − STDs)/STDs

Precision was expressed as the relative standard deviation of the measured concentration in repeated analyses.

To evaluate potential matrix effect (ME) of the optimized method, we adopted the following approach: a pooled serum sample (analytes were below the MQLs) was extracted as reported above (Section 2.5); the final supernatant was then spiked with analyte standard solutions at two concentration levels (low and high) and analyzed. The low-spike concentrations were 0.5 ppb for PCBs and 10 ppb for BFRs, whereas the high-spike concentration was 10 ppb for PCBs and 1000 ppb for BFRs.

Quantification of this sample was compared to results obtained using a standard solution at the same analyte concentration levels. The percentage ME (matrix ion suppression/enhancement) was calculated. If ME ≈ 0%, then there is no observed ME. If ME > 0%, then an ion enhancement occurred. If ME < 0%, then an ion suppression occurred.

Rec % experiments were calculated by comparing the area ratio of the analyte to the IS of samples fortified before and after extraction. Under these conditions, any differences are only due to the efficiency of the extraction, as both samples are subject to the same matrix effects. The Rec% of the analytes was evaluated on samples fortified at concentrations of 0.5 ppb (low spike) and 10 ppb (high spike) for PCB, 10 ppb (low spike) and 1000 ppb (high spike) for BFR.

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Separation Method Development

3.1.1. First D-Optimal Design

To select the optimal chromatographic conditions, single solutions and a mixture of standards were subjected to a series of analyses selected by the DoE approach. First, the standard solutions were analyzed in full scan mode to obtain the exact mass. Then, a D-optimal design was used as a screening method to estimate the relative influence of factors affecting the injection mode and the chromatographic separation (Section 2.4). Quadratic terms have not been considered at this first stage.

The number of experiments was selected by the D-optimal algorithm as a compromise between the optimal M-parameter [24] and the solutions with a lower, but still significant, number of experiments.

The retention factor between the two PCB128-PCB167, which is the lowest of the compounds under consideration, was chosen as a response for DoE modeling to optimize the chromatographic separation.

The peak area to full width at half maximum (A/FWHM) ratio was the second response to optimize. Thus, method sensitivity and peak shape were considered simultaneously.

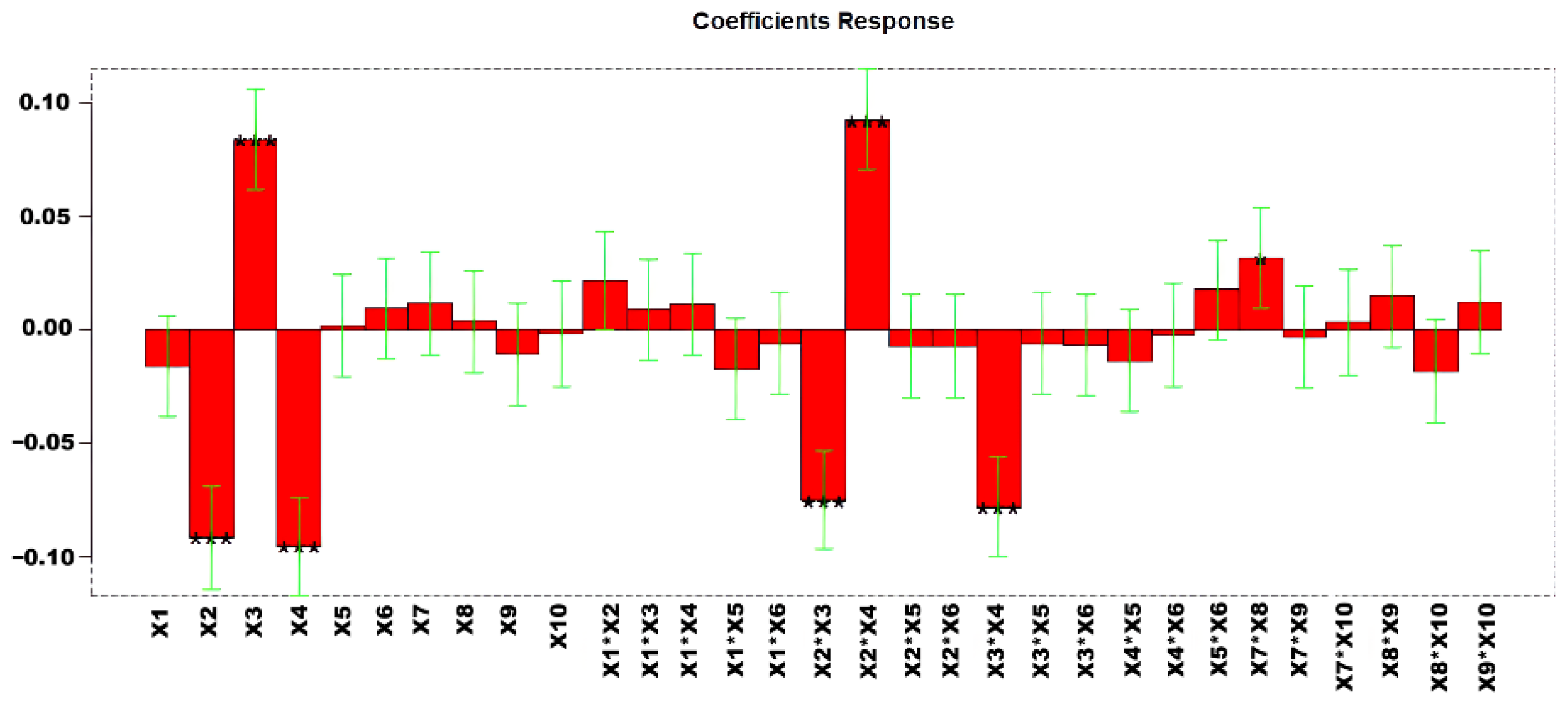

(1) Resolution Between PCB128-PCB167

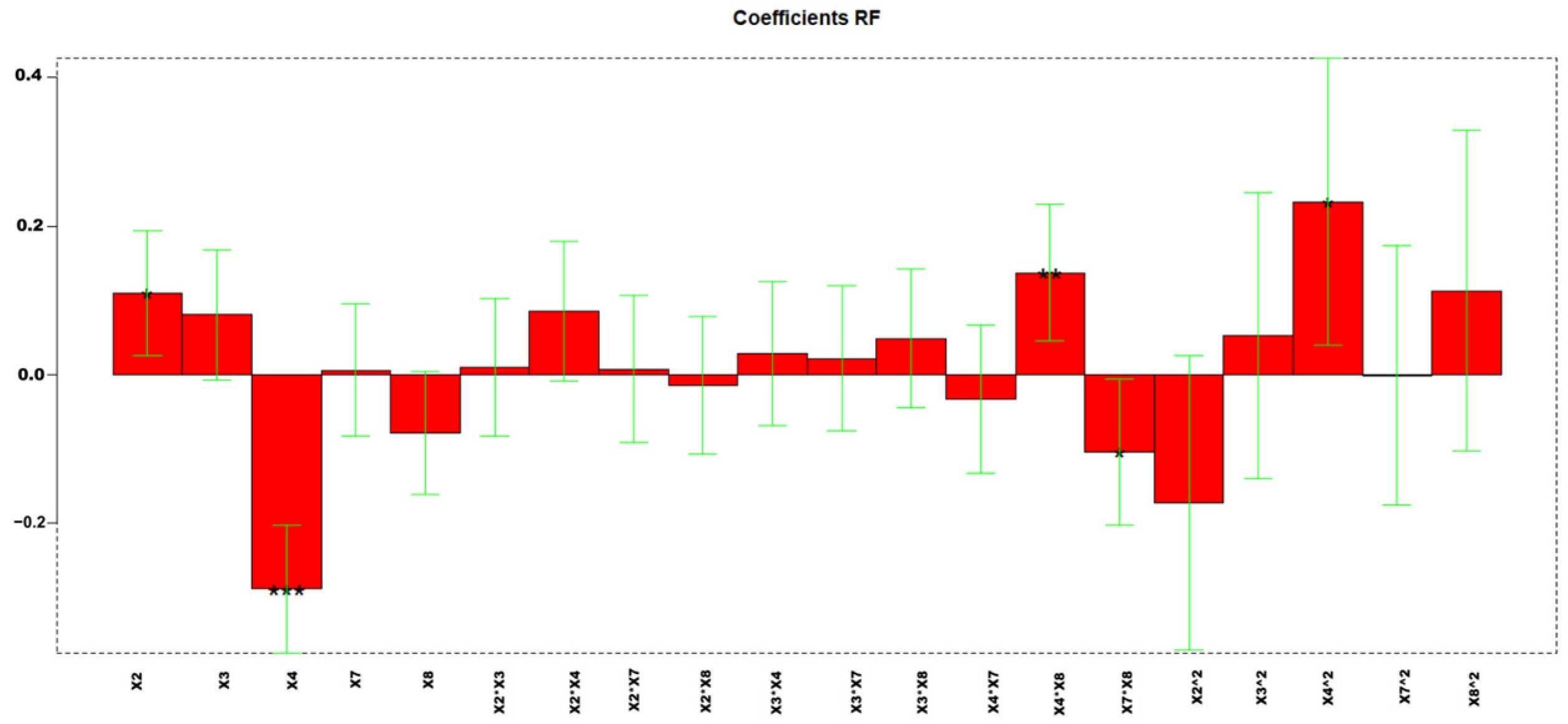

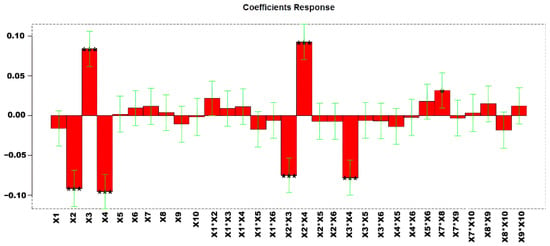

In total, 58 experiments were performed to obtain the models with explained variances of 77.38%. Figure 3 shows the regression coefficients obtained for the MLR (multiple linear regression) model. The list of variables is reported in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Regression coefficients for MLR-DOE. * p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.001.

The estimated effects of the factors and their statistical significance at 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) are shown in Table S5. To select the optimized condition variables for analysis in a second DOE, we examined the response surfaces of the significant variables (Figure S2). The response surfaces indicated that X2 and X4 should be set at lower values, while X3 should be maintained at higher values to maximize the desired response. The corresponding confidence interval responses are provided in Figure S3.

Given the significant interaction between X7 and X8, we decided to further optimize these variables by narrowing their range of variation, as described in Section 3.1.2. This approach allowed a more precise assessment of their combined effect on the response.

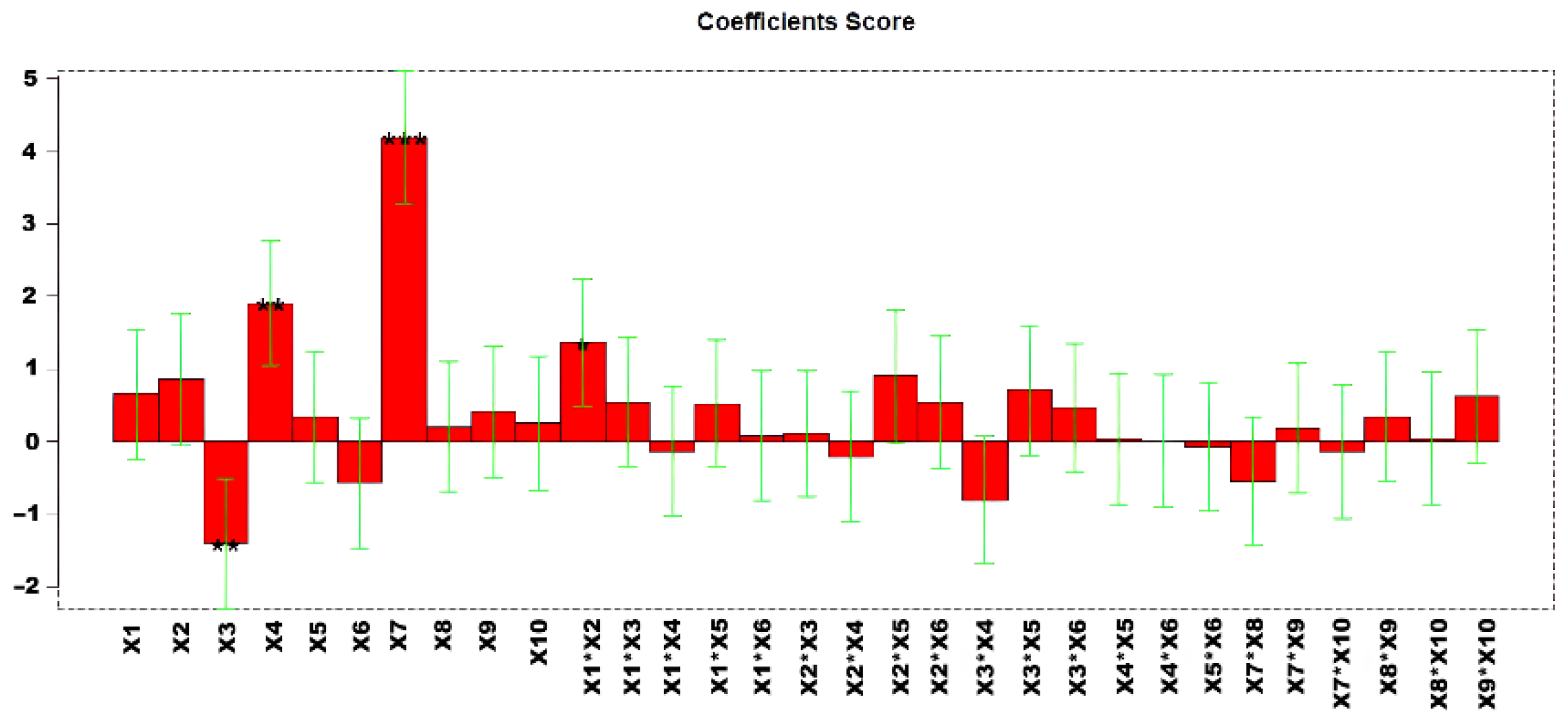

(2) Method Sensitivity and Peak Shape

The second part of this DoE involved the optimization of A/FWHM ratios. However, considering the high number of analytes (Table 3) involved in method development, we used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the 58 experiments. PCA was then applied to a dataset in which the rows are the DoE experiments and the columns are the 44 analytes considered for this work. Figure S4 shows PCA scores and loadings plot obtained in this way. The loadings plot shows that the increase in all A/FWHM ratios is found at positive PC1 values, where all corresponding loadings are located. Thus, high positive PC1 score imply high A/FWHM ratios for all the analytes. This indicates that PC1 scores are sufficient to fully describe all (or most of) the analytes, and, in the DoE, the optimization of the model is obtained by maximizing such value. Therefore, the dimensionality of the problem was reduced by using a single response variable in the PCA.

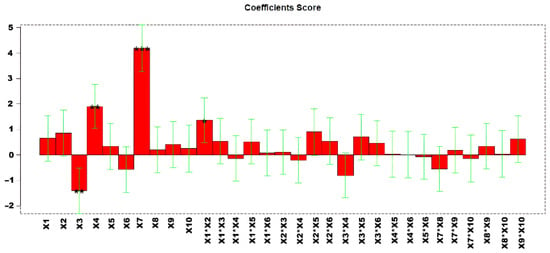

Highly informative models were obtained, with explained variances of 61.72%. Figure 4 shows the regression coefficients obtained after performing the MLR model. The estimated effects of the factors and their statistical significance at 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) are shown in Table S6.

Figure 4.

Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Analysis of the response surfaces (Figure S5) revealed that X7 and X4 should be maintained at higher values, whereas X3 should be set at lower values. The corresponding confidence interval responses are provided in Figure S6. Given the observed significance of variables X3, X4, and X7, these factors were selected for further optimization in a second D-optimal design to refine the experimental conditions and improve the response.

3.1.2. Second D-Optimal Design

To further optimize the significant parameters found in the first DoE model, a second D-optimal design was calculated by excluding the non-significant variables and including the quadratic terms. This design enabled a more precise optimization of the three significant parameters: first oven temperature (X2), first temperature holding time (X3), and second oven ramp rate (X4). Pulse pressure (X7) and pulse duration (X8) were also included due to the statistical significance of their interaction. Specifically, a lower range was set for X2 and X8, a higher range for X3 and X7, and a central level was added for X4. With the D-optimal algorithm, a 29-runs design was selected (Figure S7). Three replicates of each experiment, and three replicates of the central point (Table S3) were performed.

(1) Resolution Between PCB128-PCB167

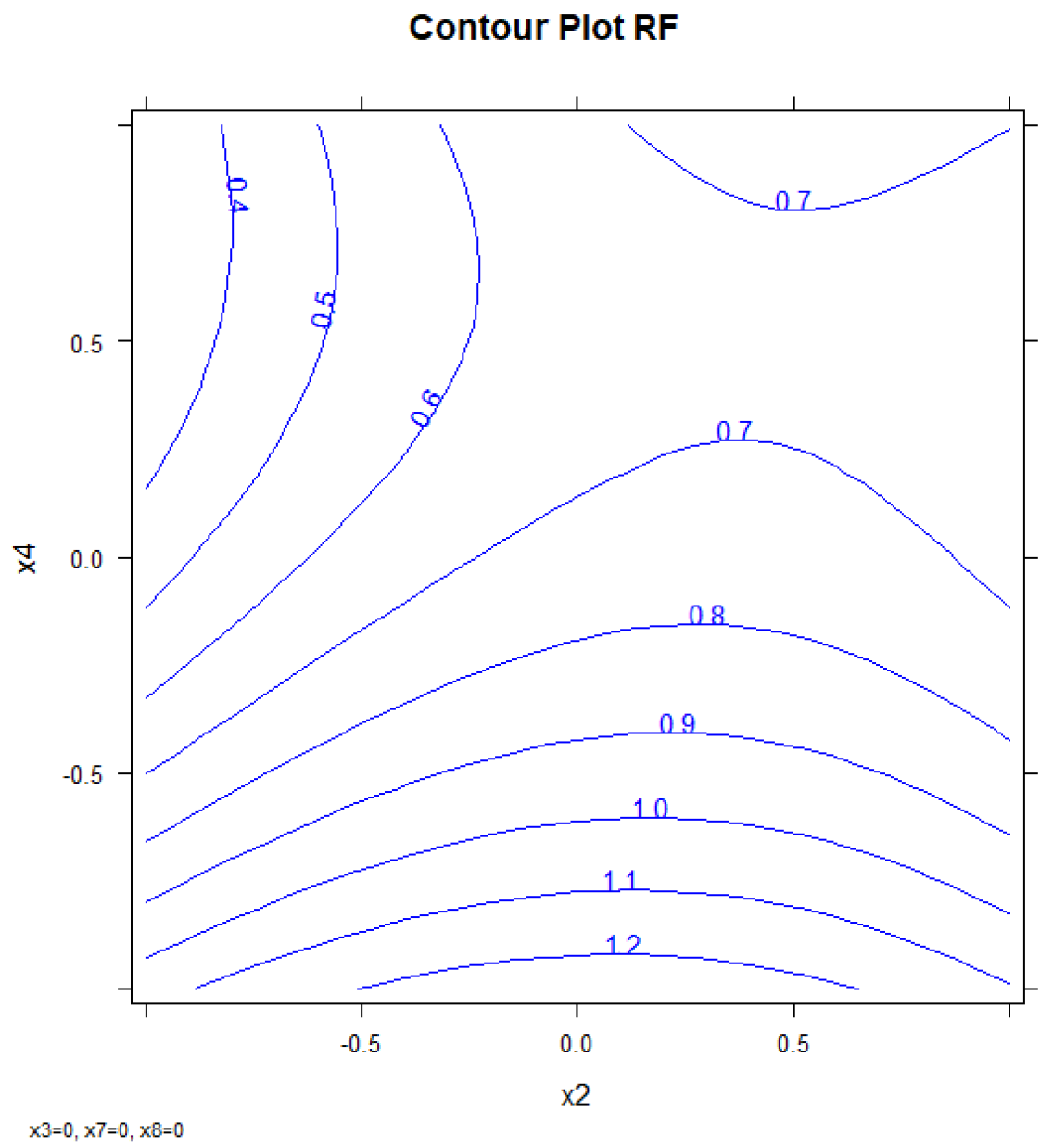

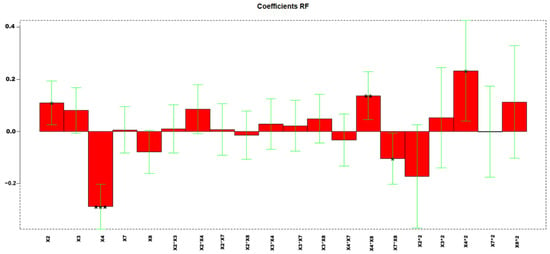

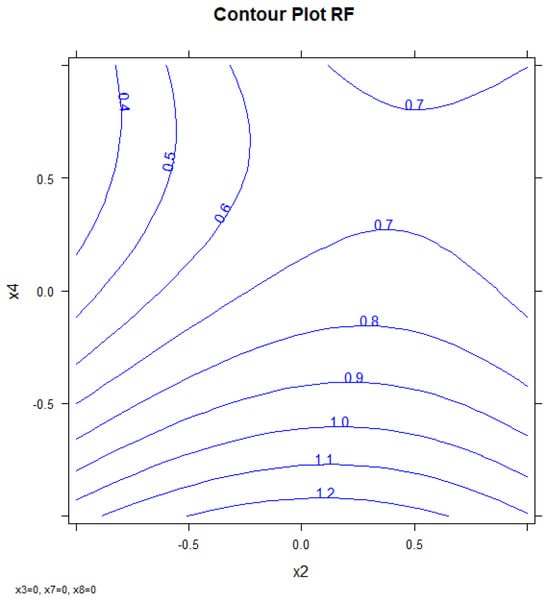

Highly informative models were obtained, with explained variances of 68.36%. Figure 5 reports the coefficients obtained for the MLR-DOE model.

Figure 5.

Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

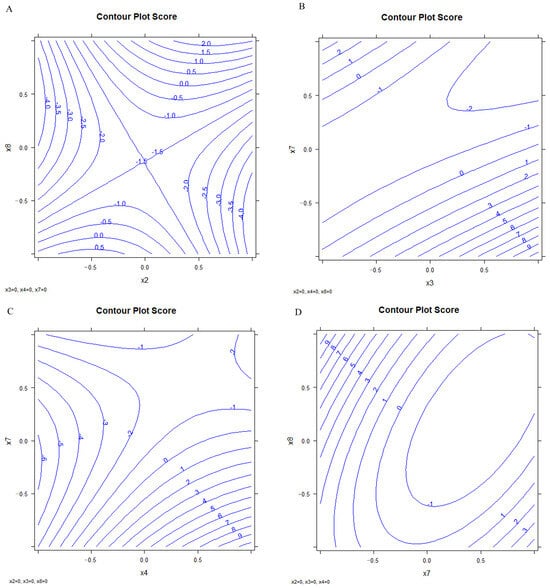

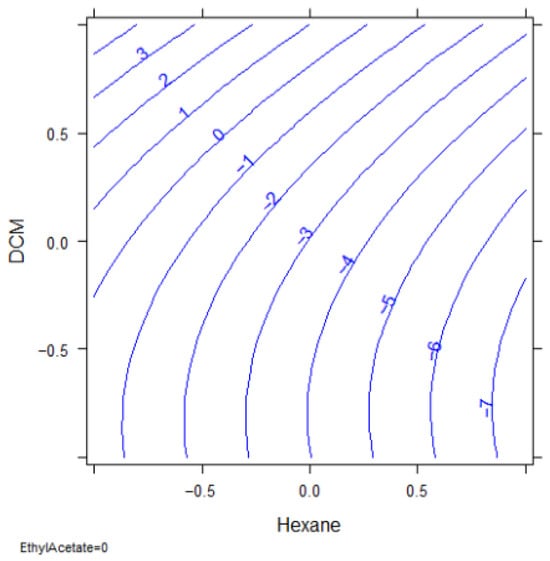

The values corresponding to every factor in each experiment and the responses for each compound are shown in Table S7. Figure 6 shows the response surface obtained by using the three-dimensional response surfaces for X2, X4, and resolution PCB128-167 (RF). Three-dimensional response surfaces show the effect of two independent variables on a given response, at a constant value of the other independent variable (X3, X7, X8). Figure S8 shows the confidence intervals.

Figure 6.

Response surface: First oven temperature (x2) vs. second oven ramp rate (x4) vs. response (RF).

(2) Method Sensitivity and Peak Shape

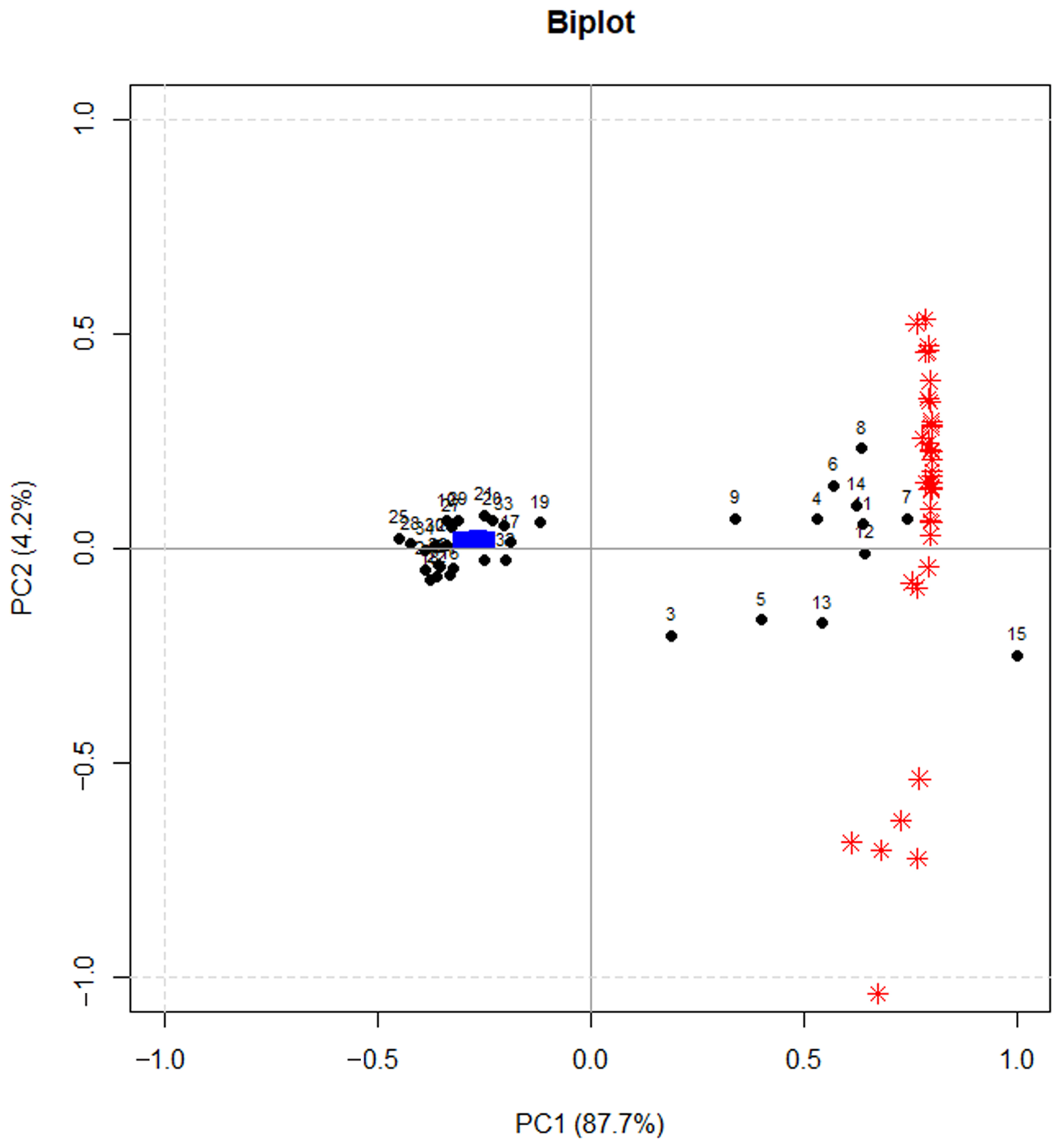

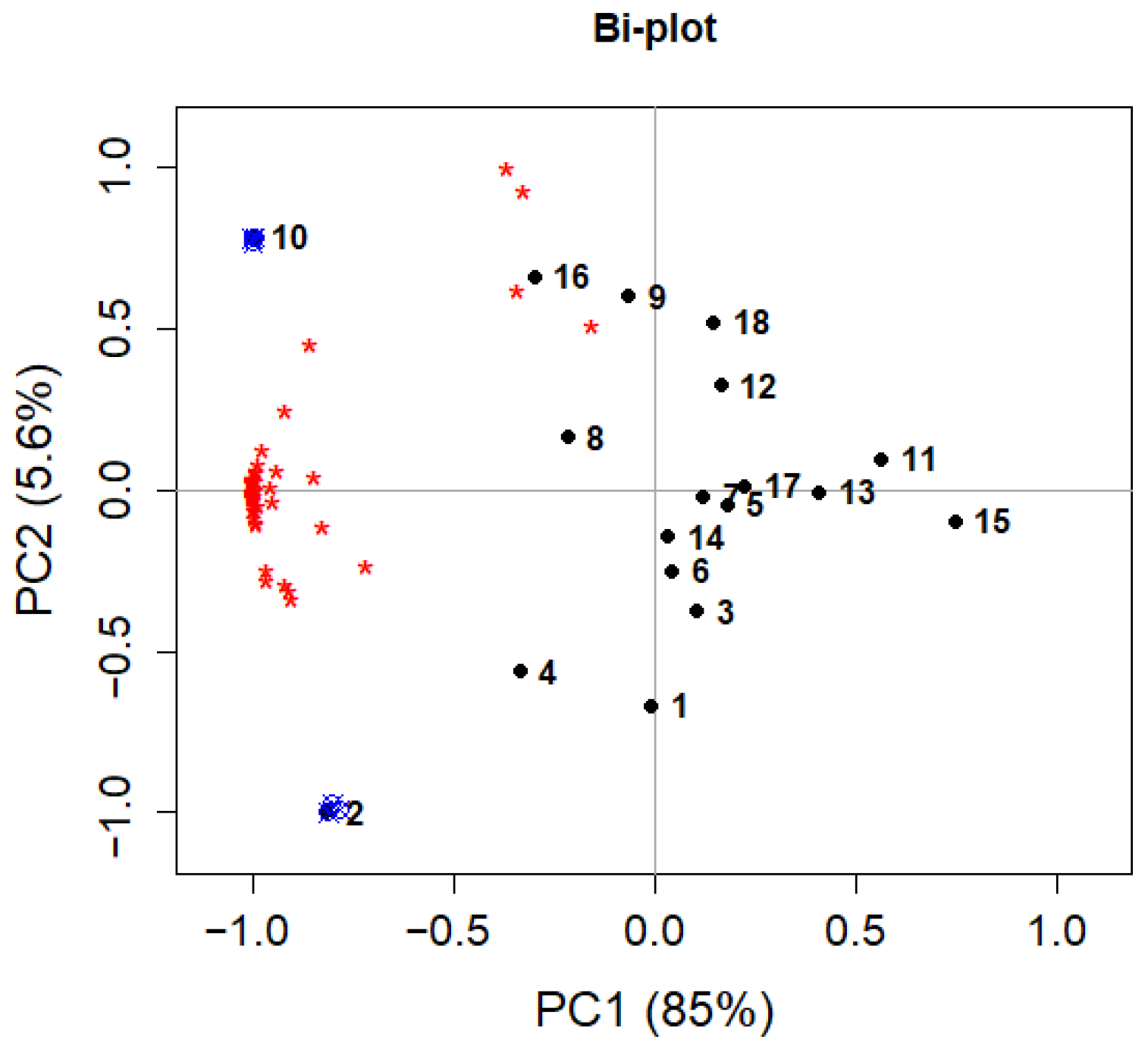

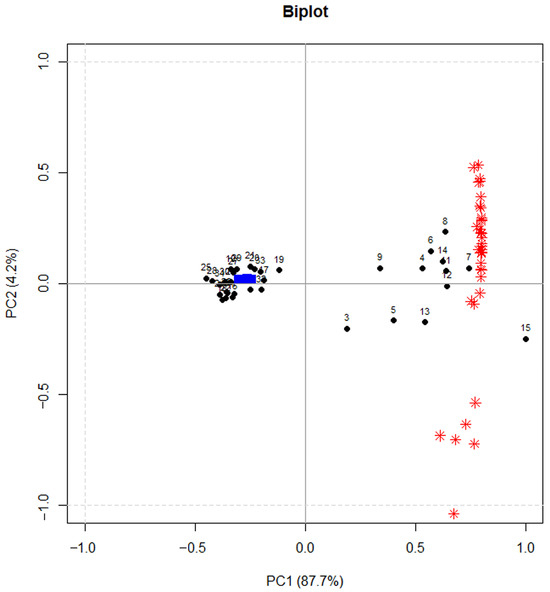

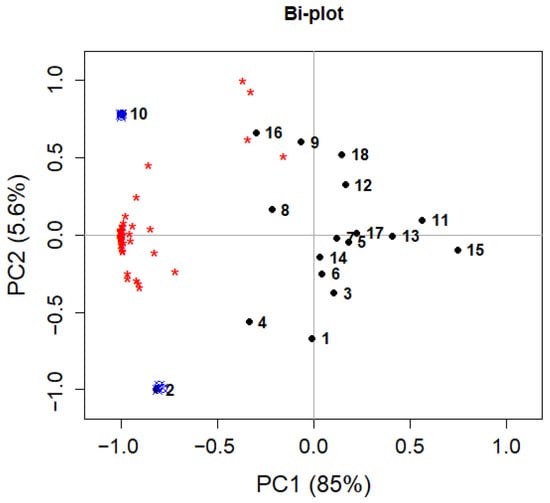

Also in this case, PCA was used to reduce the data dimensionality. Figure 7 shows the calculated PCA model (experiments and A/FWHM for all the compounds), which allowed us to select PC1 scores as the DoE response variable.

Figure 7.

Bi-plot of the PCA. Black points represent the DoE experiments (numbers), red asterisks the loadings, blue symbols are the projected experiments for validation.

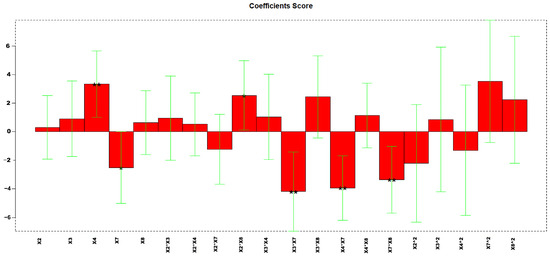

An informative model was obtained, with an explained variance of 51%. Figure 8 reports the coefficients obtained for the MLR-DOE model.

Figure 8.

Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model. * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01.

The values corresponding to every factor in each experiment and the responses for each compound are shown in Table S8.

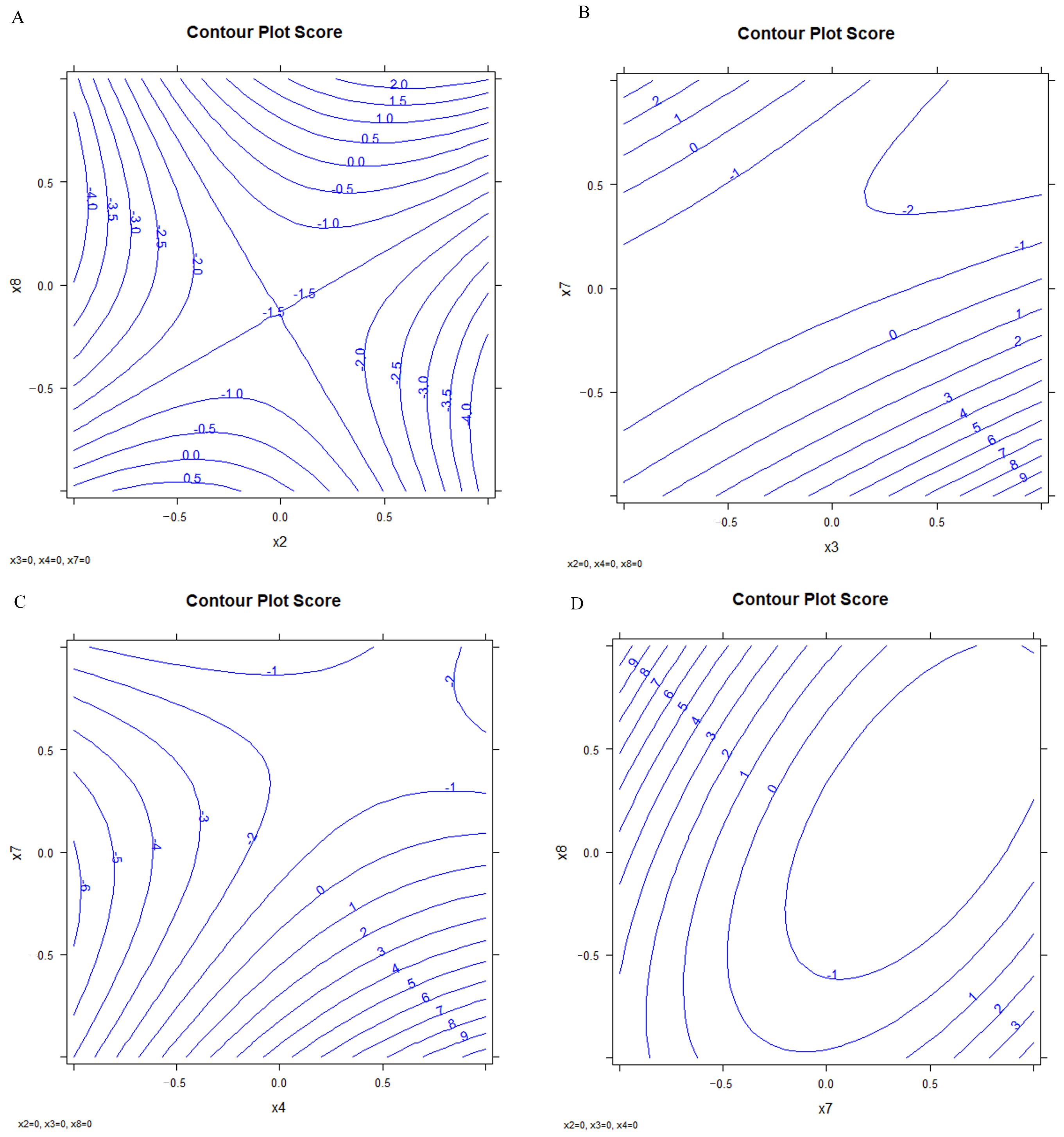

The optimized conditions were selected by the analysis of the response surface of the significant variables (Figure 9). Figure S9 shows the confidence intervals.

Figure 9.

Response surface; (A) x2 vs. x8, (B) x3 vs. x7, (C) x4 vs. x7, (D) x7 vs. x8.

This experimental design approach enables the construction of response surfaces and the identification of factor settings that optimize analytical performance. Table 7 reports the final optimized conditions.

Table 7.

Selected GC-MS working conditions.

3.2. Extraction and Purification Method Development

In the second optimization step, keeping the instrumental conditions reported in Table 7, attention was focused on the extractive conditions for the analytes of interest.

The two classes of pollutants were extracted simultaneously in human serum samples by LLE. Various solvents or solvent mixtures have been used in PCBs LLE extraction: hexane, hexane/ethyl ether, and hexane/methyl tert-butyl ether [34,35]. For NBFR hexane, DCM, and hexane/methyl tert-butyl ether and DCM/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) have been used [16,22].

In our study, three extraction reagents, ethyl acetate, n-hexane, and hexane/ethyl ether (1:1 v/v), were tested.

Preliminary tests showed that hexane was the most suitable solvent for extracting analytes such as PCB and non-polar NBFR. However, a more polar solvent, such as EtAc, produced good results for more polar analytes. Consequently, the extraction procedure was optimized using these two solvents.

Further purification was performed to reduce apparent matrix interference in instrumental analysis. Two different SPE cartridges, LC-Si and ENVI Florisil, which are the most commonly used in the literature, were tested with different elution mixtures. DoE approach was used to optimize the extraction procedure.

Design of Experiment

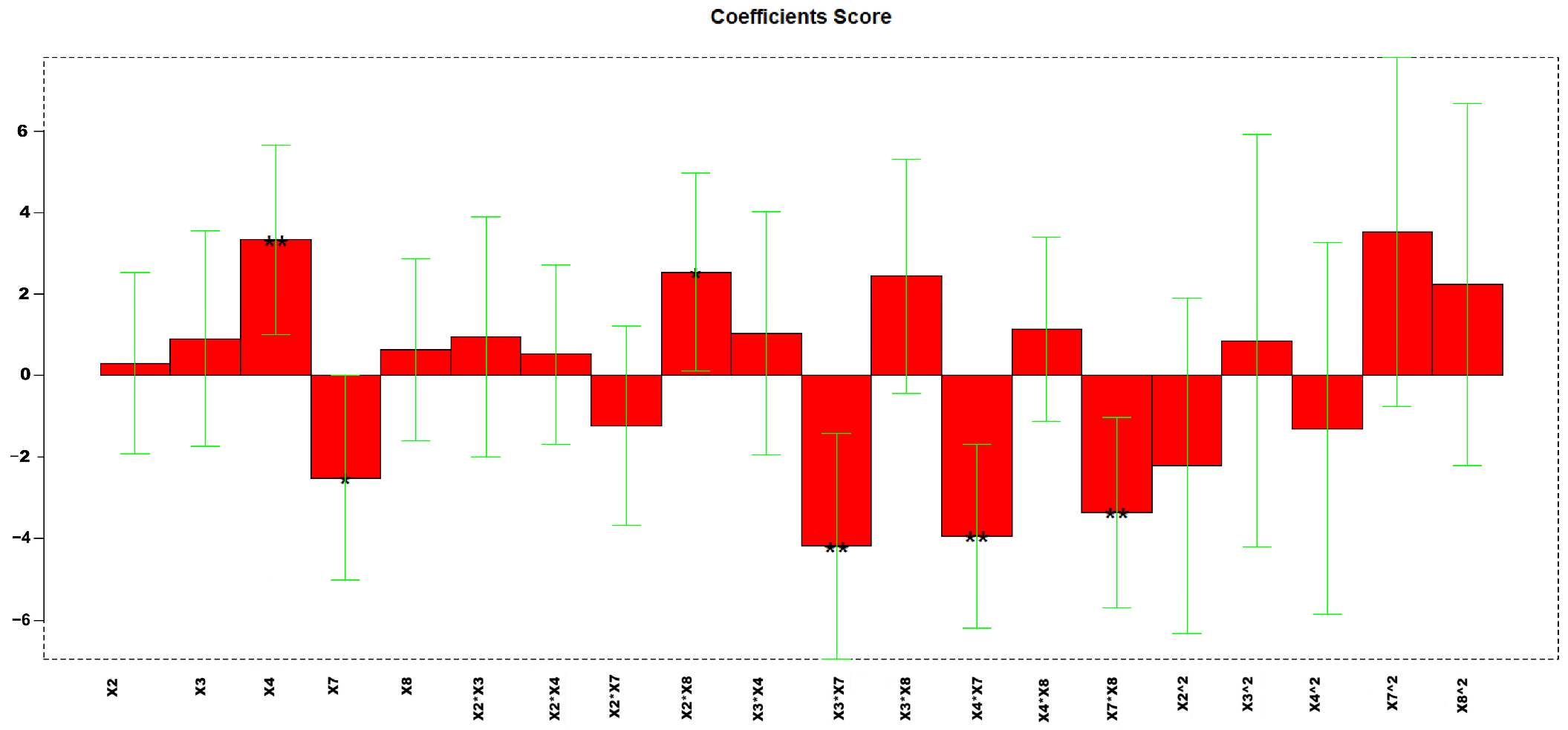

The three variables kept in consideration for the extraction optimization were the volume of EtAc, the percentage of DCM, both considered on three levels, and the volume of hexane, considered on two levels. In total, 18 experiments were carried out, corresponding to a full-factorial design in which all the combinations of variables were kept into account. As responses, the peak area to full width at half maximum (A/FWHM) ratio of all 44 analytes were considered. Due to the high number of responses, in this case, PCA was also applied to A/FWHM data. In this case, all loadings showed a negative PC1 value, thus the aim of the regression applied to DoE was to minimize the PC1 response.

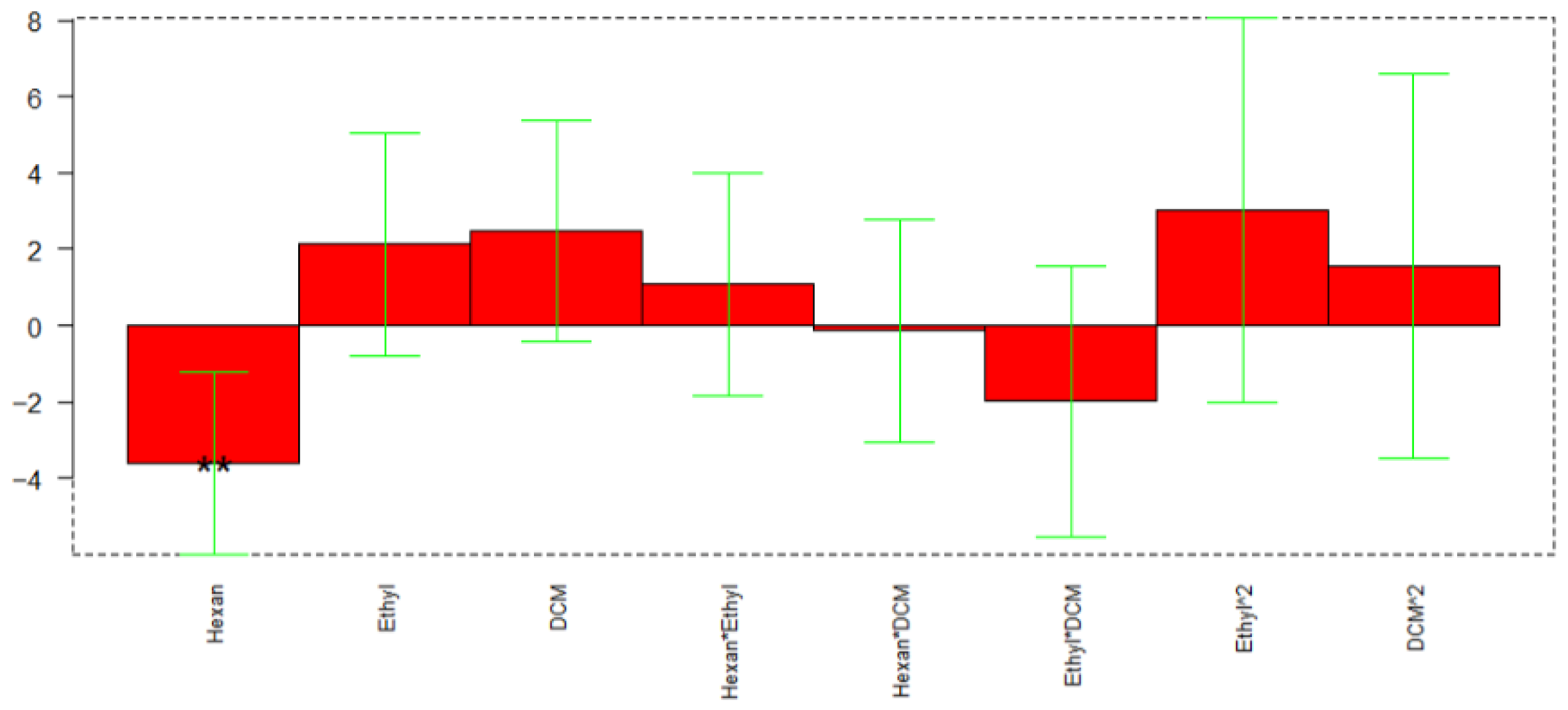

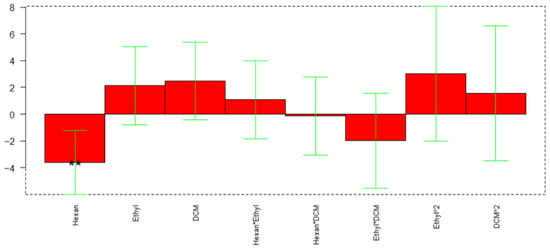

The calculated model retained 47% of explained variance; Figure 10 reports the coefficients obtained for the MLR-DoE model.

Figure 10.

Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model. ** p < 0.01.

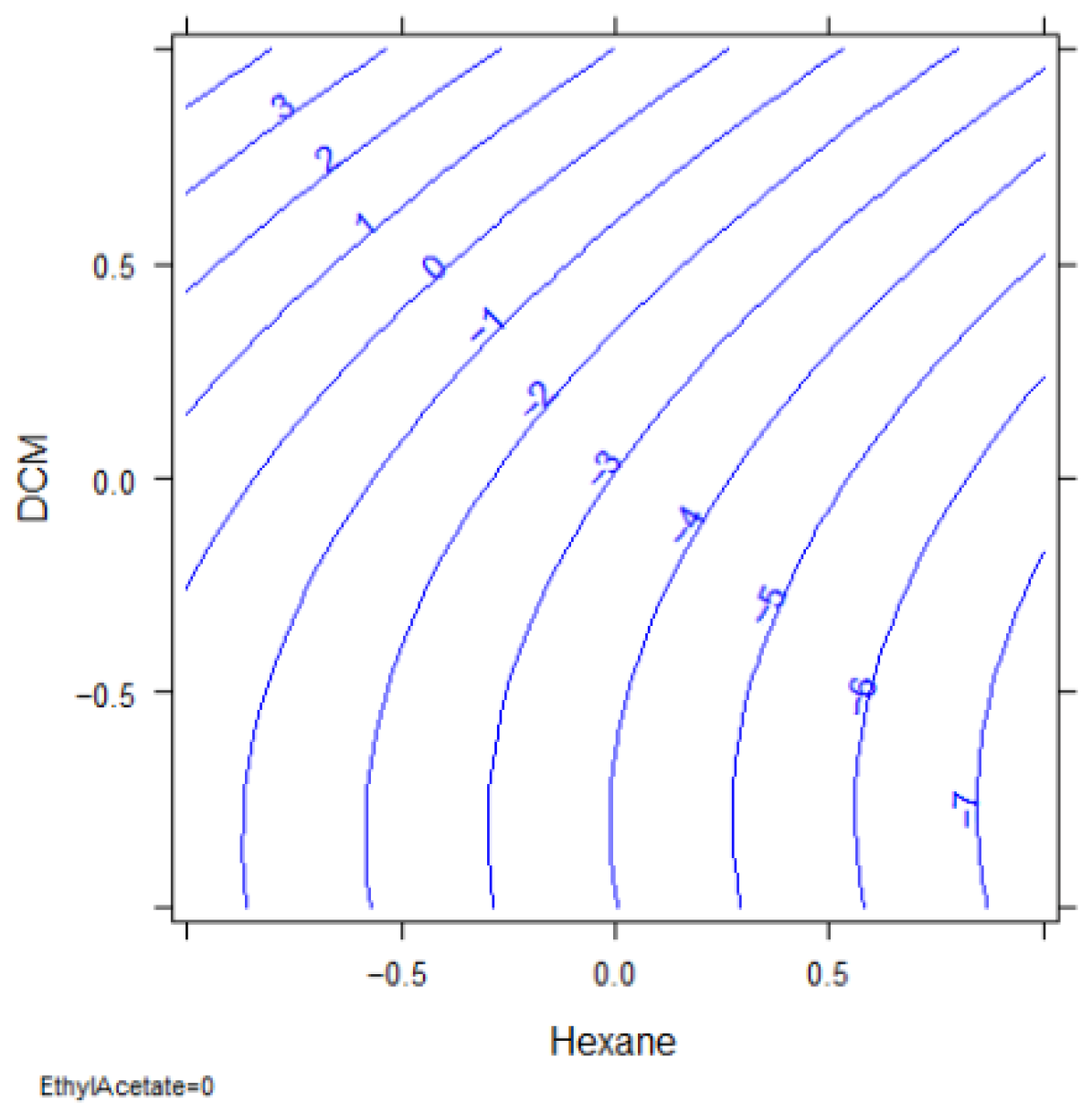

In this case, only the volume of hexane resulted significant (p-value 0.0075), with a lower significance of the percentage of DCM (p-value 0.0855). The response surface reported in Figure 11 indicates that the optimal extraction for most of the analytes is obtained with hexane volume at its higher level (3 mL) and the DCM at the lower (0%).

Figure 11.

Response surface: hexane vs. percentage of DCM.

To validate the model, the two experiments with the optimal combination of variables were repeated three times each, and the results were projected onto the PCA model. Figure 12 shows the bi-plot (reporting both scores and loadings) of the PCA model with the projections of the repeated samples. Figure 12 clearly shows a good reproducibility of the experiments, because the projected samples are well-overlapping the corresponding DoE experiments (2 and 10) on which they are based. Moreover, Figure 12 also shows that experiments 2 and 10, both with hexane at its higher level, are those with better performances, being in the same portion of the plot (negative PC1) as most of the loadings and with the highest negative PC1 scores.

Figure 12.

Bi-plot of the PCA model for extraction optimization. Black points represent the DoE experiments (numbers), red asterisks the loadings, blue symbols are the projected experiments for validation.

3.3. Method Validation

3.3.1. Linearity, Accuracy, and Precision

Calibration curve parameters were obtained by plotting the peak area ratio between analyte and IS for each standard solution against theoretical concentration by linear least squares regression analysis. Linearity was assessed via six-point calibration curves in isooctane thanks to the presence of non-significant ME. The resulting calibration curve equations were in the form of Y = a (±δa)X + b (±δb). Calibration curve determination coefficients (r2) were ≥0.995 for all molecules in the linearity ranges (0.5–50 ppb for PCB, 10–500 ppb for NBFR). Solutions were obtained by diluting the working solution with a mixture of isooctane/toluene 1:1 (v/v). Each standard solution was analyzed in duplicate, and IS concentrations were 10 MQL.

Accuracy values ranged between −10.4% and 10.5% at three different concentration levels. RSD values were between 8.25% and 10.2% for the intra-day analysis (repeatability) and between −10.3% and 10.6% for the inter-day analysis (reproducibility). Table S9 reports the results.

3.3.2. Selectivity

Comparison of the chromatograms for these samples showed no interference from matrix components. Furthermore, the relative abundances between the two monitored ions for each analyte belonging to PCB were at least 20% of the expected value [33].

PCB 28 and 31 are the only two co-eluting PCBs. However, the co-elution of these two congeners is a well-documented phenomenon in PCB analysis, particularly on 30 m columns containing 5% phenyl methyl silicone as a stationary phase [36]. Therefore, in accordance with European Commission Regulation (EU) No 709/2014, which recognizes that PCB 28 and PCB 31 congeners often co-elute during GC-MS analysis, they were considered together during quantification [37].

For BFR, the only problem in selectivity was not assigning the peaks for 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexabromocyclododecane to the correct isomer due to interconversion between them [38,39].

3.3.3. Method Detection Limits and Method Quantification Limits

MDLs and MQLs for all the analytes ranged from 0.01 ppb to 3 ppb and from 0.05 ppb to 10 ppb, respectively. Table S10 in Supplementary Information reports the results.

3.3.4. Recovery

The following recovery results were obtained at the optimized condition for each pollutant class, which are consistent with those reported in Table 8:

Table 8.

Recovery (%) for PCB and BRs (n = 3).

The term ‘legacy BFR’ refers to BFRs that are subject to regulatory control [13], whereas ‘NBFR’ designates alternative and emerging compounds that have been introduced as substitutes for the regulated ones [40].

The recovery values for the D-optimal design validation experiment can be found in the Supplementary Material (Table S11).

3.3.5. Matrix Effect

Table 9 reports the results obtained for ME for PCB and BFR.

Table 9.

Range of matrix effect for PCB and BFR.

3.4. Analysis of Certified Serum Sample

The multi-analyte method was applied to NIST SRM 1957 human serum. The estimated concentrations based on recoveries were reported in Table 10. Values are consistent with the certified reference concentrations. According to NIST documentation, the reported value for PCB 180 includes a minor contribution from PCB 193, which was not included in our method. Validation was performed to ensure the reliability of the analytical procedure.

Table 10.

PCB concentration (ppb) in NIST SRM 1957 human serum.

3.5. GC-HR-MS

We transferred the presented method to the GC-HRMS platform. The chromatograms obtained are reported in Figure S10.

Considering GC-HR-MS is required under several regulatory frameworks, particularly for BFR [37], we tested our extraction and chromatographic method using HR-MS to compare its performance relative to our low-resolution approach.

Our results showed that the optimized chromatographic separation allowed the low-resolution method to yield identification and quantification results statistically comparable to those obtained via HR-MS on test samples (α = 0.05), confirming its high selectivity and analytical robustness.

As anticipated, GC-HR-MS provided lower MDL, especially for brominated compounds, in accordance with published data and consistent with results typically obtained using other highly selective detectors, such as electron capture detectors (ECD) and chemical ionization.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analytical Separation Method Development

Several factors affect a GC-MS analysis. The accuracy of generated data depends on the overall performance of the GC system, starting from the choice of injection mode on the GC. Matrix-induced response enhancement is a complex phenomenon observed during the analysis of real samples containing some matrix components (e.g., lipids, waxes, pigments, etc.). It is not always possible to completely separate these components from the analytes during the clean-up, especially when multi-residue methods are used.

Pulsed splitless injection is one of the most sophisticated techniques that can significantly improve the performance of classic split/splitless injection. Benefits are expected in terms of lower detection limits and improved reproducibility of analytical results [26]. However, the geometry of the injection port, the type of liner, and the analytical column used can play an important role when using this injection technique. As a result, it is necessary to optimize the parameters that most affect the analysis.

The aim was to improve the two responses: the retention factor between PCB128-PCB167, and (A/FWHM) ratio for all the analytes.

By analyzing the coefficients and their statistical significance from the initial DoE, we identified the most impactful variables influencing GC-MS performance (Table 4).

These included the first oven ramp rate, first temperature holding time, and second oven ramp rate. These variables were then further explored through a second, more targeted D-optimal design, in which their variation ranges were extended to better characterize their influence on system performance.

The linear terms of the first oven ramp rate, first temperature holding time, and second oven ramp rate showed a statistically significant impact on the responses. Interestingly, the first temperature holding time exhibited opposite effects on the two target responses: it improved one while adversely affecting the other. We chose to maximize the ratio between peak area and full width at half maximum (A/FWHM), since even at the maximum holding time, PCB 128 and PCB 167 remained chromatographically resolved (retention factor > 1). Accordingly, we set the first oven ramp rate to its maximum value and the second oven ramp rate to its minimum.

The first temperature holding time and time of pulse pressure did not show significant main effects on the responses when considered individually. However, their interactions with other variables proved relevant: the interaction between pulse pressure time and first oven ramp rate had a positive effect on the response, whereas the interaction between pulse pressure time and second oven ramp rate had a negative effect. Based on this, the pulse pressure time was set to its maximum value. Conversely, although the interaction between second oven ramp rate and first temperature holding time had a negative impact, we fixed the first temperature holding time at its minimum value, since it did not significantly affect the response, allowing for a reduction in total chromatographic run time.

This iterative, data-driven approach enabled the development of a robust and optimized method, improving both sensitivity and reproducibility in the final GC-MS protocol.

4.2. Extraction and Purification Method Development

The extraction and purification of serum samples are critical steps in the analysis of contaminants because they directly influence the accuracy and reliability of the results. Serum is a complex biological matrix containing proteins, lipids, and other substances that can interfere with detecting and quantifying contaminants. A well-designed extraction and purification procedure effectively isolates the contaminants of interest, removing potential interferences and concentrating the target analytes.

LLE and SPE seem to be the main analytical procedures among previously published papers. However, different solvents, cartridges, and protocols are used in the literature. Among the tested solvents, hexane was efficient for PCB and less-volatile NBFR, whereas ethyl acetate was essential for more polar analytes. Thus, hexane and ethyl acetate were chosen as extraction solvents.

For purification, we firstly tried to use two cartridges in series as described in the literature [31,41]. However, the time and volume of solvent required for simultaneous use were higher, and no better results were obtained. ENVI Florisil provides a better result even if more polar analytes (i.e., tribromophenol) are retained in the cartridge. This is critical because PCB analysis requires a purification step to remove other chlorinated contaminants such as OCPs. In fact, this method was specifically developed and validated for the selective determination of PCB congeners and BFR. While OCPs could be present in the studied matrix, they are not the target analytes. Due to their structural similarity and potential to co-elute with PCB and PBDE [42], OCPs were considered potential interferents, and the optimization of the method focused on maximizing PCB selectivity and quantification accuracy. The use of ENVI-Florisil is therefore essential. We tried it with samples spiked with two contaminants, alachlor and atrazine, and the recovery was less than 10%. Therefore, no subsequent SPE cartridge purification was performed on the analytes extracted after washing with ethyl acetate.

4.3. Method Validation

Given the methods that have been published to date, it is a challenge to develop a comprehensive method of analysis for all the chemicals that may be present in serum. Most of the studies, in fact, focused on the determination of novel brominated flame retardants. This is due to the different analytes’ physical–chemical properties and the complex matrix.

This diversity precludes the possibility of tailoring extraction and clean-up protocols to a single class of compounds, thus necessitating a multi-step strategy.

It is therefore necessary to find the best compromise between the performance of the recovery method and the matrix effect to obtain the highest sensitivity, as described in our study.

Method Performance

The performance of the analytical method was evaluated to ensure its reliability and suitability for detecting target compounds. The developed method is suitable for quantification due to its selectivity, high levels of repeatability, and reproducibility (bias (%) and RSD (%) < 20%).

MDLs and MQLs for PCB meet the thresholds useful for screening in serum [43,44], as shown in Table S12 in Supplementary Information, and are comparable to those reported in the literature (Table 11).

Table 11.

LODs and LOQs for PCB in the literature.

Several methods for the extraction of PCB in serum have been reported in the literature. These include the use of diethyl ether/hexane 1:1 for liquid phase extraction and hexane for solid phase extraction [46]. The recoveries reported ranged from 58% to 124%, which is less efficient than the analytical method developed. A method for the extraction of PCB and PBBs (polybrominated biphenyls) [43] has also been developed. PBBs are BFR with chemical-physical properties very similar to those of PCB. In this work, only hexane was used for both liquid and solid phase extraction. The recoveries obtained for PCB are close to those of the method used in this work, although they have a narrower range of 93–97%. However, the method included significantly fewer analytes. A method was then developed for the extraction of five classes of POPs, including PCB, NFR, and FR [49]. This involved two different approaches for less and more polar analytes. Specifically, a liquid phase extraction with hexane/diethyl ether 9:1 and a solid phase extraction with a Florisil cartridge were performed. More polar compounds, such as 2,4,6-tribromophenol, were extracted using a QuEChERS approach. This method involved a two-step analytical procedure: GC-MS-MS for PCB and some NBFR and BFR, and LC-MS-MS for other BFR. The recoveries ranged from 70 to 116% for BFR and NBFR and 86–113% for PCB. Furthermore, the extraction and analysis procedures are more complex and different depending on the class of pollutants, in contrast to the method developed in the present work.

Among the methods for the extraction and analysis of NBFR [25], one of them involved the use of EtAc for the liquid phase extraction and a two-step purification with SPE, Oasis HLB cartridge, and a Florisil cartridge. Again, the extraction procedure is more complex and resulted in recoveries in a wide range, i.e., 73–122%.

Due to the emerging nature of NBFR, serum reference limits have not yet been established. Therefore, the MDLs and MQLs obtained with the present analytical method for NBFR can only be truly evaluated once reference limits are established. The same applies to hexabromocyclododecane, for which only a few studies are available.

However, there are studies in the literature that have identified NBFR in human serum. QuEChERS seem to be one of the most widely used extraction methods for NBFR [23,50]. Zao et al. [50] reported a LOD for DBDPE of 10 pg/mL, and those of other NBFR in a range of 0.01–0.1 pg/mL. Gao et al. [22] reported LODs values ranged from 0.3 to 50.8 pg/mL and 300–500 pg/mL for DBDPE.

LLE has been used. Tay et al. [51] reported LODs ranged from 2.6 to 120 (pg/serum sample). Notably, larger quantities of serum are used, and none of these studies examined more than one type of pollutant. In fact, only BFR or both BFR and PDBEs were analyzed. The presence of PCB and BFR, as well as the large number of analytes included in the presented method, makes method optimization very challenging in our case.

Ali et al. [52] have published a method for the simultaneous quantification of OCPs, PCB, PBDEs, HO-PCB, and HO-PBDEs. Although the LOD and LOQ are not reported, the analysis procedure is very lengthy. It comprises an extraction and purification step using SPE (HLB and a silica Bond Elut cartridges), followed by a derivatization step involving silanisation. On the other hand, the recovery of our method is entirely satisfactory. In the literature, in fact, the values range from 34 to 123% [51], 62–100% [22], 61–158% [52].

The developed method showed negligible matrix effects for all target compounds.

In addition, the analytical method developed enabled the analytes to be concentrated and the serum samples to be purified, removing numerous interferents such as the pesticides mentioned above. Although further improvements in the method’s LOQs could potentially be achieved by applying alternative detectors or ionization techniques—such as chemical ionization—the procedure developed in this study remains fully valid and reliable, particularly in terms of chromatographic separation and analyte extraction from serum. The robustness and effectiveness of the extraction and separation steps ensure the overall performance and applicability of the method, regardless of the detection strategy employed.

5. Conclusions

The method developed in this study proved to be efficient, providing a consistent extraction and analysis protocol for a wide range of pollutants characterized by different chemical–physical properties, with highly satisfactory results in terms of recovery, matrix effect, selectivity, MDL, MQL, accuracy, and precision.

In addition, the number of experiments required to identify the optimum working conditions can be reduced by using the D-optimal design approach for the extraction of contaminants.

Although extensive research has been conducted, the environmental relevance of several pollutants, particularly emerging contaminants, is still poorly understood and inadequately addressed by current regulatory frameworks. Furthermore, the recent literature also highlights how legacy PCB, despite being regulated for decades, are now considered reemerging contaminants. Their environmental persistence, continuous release from old materials, and long-range transport mean that they remain detectable in human matrices worldwide. This renewed attention underscores that PCB exposure is still insufficiently characterized and calls for further comprehensive investigation.

Active biomonitoring is therefore needed. The establishment of effective analytical protocols to measure emerging contaminants in humans should be a key part of this process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010036/s1, Table S1: IS used for the quantification of each compound; Table S2. MS scan parameters; Table S3. Selected experiments for the D-optimal design; Figure S1. Normalized determinant of the information matrix (M-parameter) and maximum inflation factors; Table S4. Selected experiments for the D-optimal design; Table S5. Statistically significant regression coefficients in the MLR model; Figure S2. Response surface of the significant variables: (A) x2 VS x3, (b) x3 vs. x4, (C) x2 vs. x4; Figure S3. Confidence interval responses: (a) x2 vs. x3, (b) x3 vs. x4, (c) x2 vs. x4; Figure S4. Principal Component Analysis with experiments and A/FWHM for all the compound: score in black, loadings in red; Table S6. Statistically significant regression coefficients in the MLR model; Figure S5. Response surface for method sensitivity and peak shape MLR model: (a) x3 vs. x4, (b) x7 vs. x3, (c) x7 vs. x4; Figure S6. Confidence interval responses: (a) x3 vs. x4, (b) x7 vs. x3, (c) x7 vs. x4; Table S7. Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model; Figure S7. Normalized determinant of the information matrix (M-parameter) and maximum inflation factors; Table S8. Regression coefficients obtained for the MLR model; Figure S8. Confidence interval response for X2 vs. X4; Figure S9. Confidence interval responses: (a) x2 vs. x8, (b) x3 vs. x7, (c) x4 vs. x7, (d) x7 vs. x8; Table S9. Accuration (CV %) and precision (bias %); Table S10. MQLs and MDLs for included pollutants; Table S11. Recovery for validation experiment (n = 3); Figure S10. Chromatogram obtained with GC-HRMS; Table S12. Reference values for PCBs in certified human serum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P., R.C., F.S.V.; methodology R.C., E.P.; software, R.C., N.K., A.Z.; validation, E.P., R.C., A.Z.; formal analysis, R.C., N.I., E.P.; investigation R.C., E.P., F.S.V., D.M.; data curation, R.C., E.P., N.K., A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., E.P., A.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.C., E.P., A.Z., N.K., N.I., J.F.; visualization, R.C., E.P.; supervision, F.S.V., E.P., D.M., J.F.; project administration, E.P., F.S.V.; funding acquisition R.C., F.S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNR), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3 funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. PE3—RETURN, code PE00000005, CUP J33C22002840002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all biological materials employed were obtained exclusively from commercial suppliers. The work involved method development on commercially available fetal bovine serum, which is the standard matrix for this type of analytical development. No samples were collected from human subjects, and no procedures involving human participants were performed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are openly available in AMSActa Institutional Research Repository [53].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GC-EI-MS | Gas chromatography-Electron impact-Mass spectrometry |

| DoE | Directory of open access journals |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyl |

| BFR | Brominated flame retardants |

| NBFR | Novel brominated flame retardants |

| PoP | Persistent organic pollutants |

| GC-HR-MS | Gas chromatography- high resolution- mass spectrometry |

References

- Comito, R.; Porru, E.; Violante, F.S. Analytical Methods Employed in the Identification and Quantification of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Matrices—A Scoping Review. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Bignert, A.; Andersson, P.L.; West, C.E.; Domellöf, M.; Bergman, Å. Polychlorinated Alkanes in Paired Blood Serum and Breast Milk in a Swedish Cohort Study: Matrix Dependent Partitioning Differences Compared to Legacy POPs. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Génard-Walton, M.; Warembourg, C.; Duros, S.; Mercier, F.; Lefebvre, T.; Guivarc’h-Levêque, A.; Le Martelot, M.-T.; Le Bot, B.; Jacquemin, B.; Chevrier, C.; et al. Serum Persistent Organic Pollutants and Diminished Ovarian Reserve: A Single-Exposure and Mixture Exposure Approach from a French Case–Control Study. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, C.J.; Thompson, O.M.; Dismuke, C.E. Exposure to DDT and Diabetic Nephropathy among Mexican Americans in the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Scarselli, M.; Fasciani, I.; Maggio, R.; Giorgi, F. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) Induced Extracellular Vesicle Formation: A Potential Role in Organochlorine Increased Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2017, 77, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, B.A.; Cirillo, P.M.; Terry, M.B. DDT and Breast Cancer: Prospective Study of Induction Time and Susceptibility Windows. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessah, I.N.; Lein, P.J.; Seegal, R.F.; Sagiv, S.K. Neurotoxicity of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Related Organohalogens. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klocke, C.; Lein, P.J. Evidence Implicating Non-Dioxin-Like Congeners as the Key Mediators of Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Developmental Neurotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbuckle, K.; Robertson, L. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs): Sources, Exposures, Toxicities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2749–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, M.; Andersen, H.V.; Haug, L.S.; Thomsen, C.; Broadwell, S.L.; Egsmose, E.L.; Kolarik, B.; Gunnarsen, L.; Knudsen, L.E. PCB in Serum and Hand Wipes from Exposed Residents Living in Contaminated High-Rise Apartment Buildings and a Reference Group. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 224, 113430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Polybrominated Bipheny; IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Lyon, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Saktrakulkla, P.; Marek, R.F.; Lehmler, H.-J.; Wang, K.; Thorne, P.S.; Hornbuckle, K.C.; Duffel, M.W. PCB Sulfates in Serum from Mothers and Children in Urban and Rural U.S. Communities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6537–6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, M.; Harrad, S.; Abou-Elwafa Abdallah, M.; Drage, D.S.; Berresheim, H. Phasing-out of Legacy Brominated Flame Retardants: The UNEP Stockholm Convention and Other Legislative Action Worldwide. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Wang, S.; Qu, J.; You, H.; Liu, D. New Understanding of Novel Brominated Flame Retardants (NBFRs): Neuro(Endocrine) Toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Flame Retardants Used in Flexible Polyurethane Foam: An Alternatives Assessment Update; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Guan, X.; Zhang, G.; Meng, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, G. Novel Biomonitoring Method for Determining Five Classes of Legacy and Alternative Flame Retardants in Human Serum Samples. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 131, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionetto, M.G.; Caricato, R.; Giordano, M.E. Pollution Biomarkers in Environmental and Human Biomonitoring. Open Biomark. J. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Niu, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y. Concurrent Extraction, Clean-up, and Analysis of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers, Hexabromocyclododecane Isomers, and Tetrabromobisphenol A in Human Milk and Serum. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 3402–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulara, I.; Czaplicka, M. Methods for Determination of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Environmental Samples—Review. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 2075–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svarcova, A.; Lankova, D.; Gramblicka, T.; Stupak, M.; Hajslova, J.; Pulkrabova, J. Integration of Five Groups of POPs into One Multi-Analyte Method for Human Blood Serum Analysis: An Innovative Approach within Biomonitoring Studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, E.; Kumar, N.; Drage, D.S.; Cunningham, T.K.; Sathyapalan, T.; Mueller, J.F.; Atkin, S.L. A Case-Control Study of Polychlorinated Biphenyl Association with Metabolic and Hormonal Outcomes in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2022, 40, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Yu, M.; Chen, T.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z. Determination of Novel Brominated Flame Retardants and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Serum Using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry with Two Simplified Sample Preparation Procedures. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 7835–7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, T.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, J. Determination of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Novel Brominated Flame Retardants in Human Serum by Gas Chromatography-Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1099, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leardi, R. Experimental Design. In Data Handling in Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 28, pp. 9–53. ISBN 978-0-444-59528-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Namara, K.; Leardi, R.; Sabuneti, A. Fast GC Analysis of Major Volatile Compounds in Distilled Alcoholic Beverages. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 542, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godula, M.; Hajšlová, J.; Alterová, K. Pulsed Splitless Injection and the Extent of Matrix Effects in the Analysis of Pesticides. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1999, 22, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruse, C.A.; Tipple, C.A.; Miller, M.L. Confirmation of Solid Phase Extracted Post-Blast Explosives Residues Analyzed Using Pulsed Split Injection GC/MS. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2025, 50, e202400184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, R.A. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory and Instrumentation; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-470-02731-8. [Google Scholar]

- Leardi, R.; Melzi, C.; Polotti, G. CAT (Chemometric Agile Tool), R version 3.1.2; Società Chimica Italiana: Roma, Italy. Available online: http://gruppochemiometria.it/index.php/software (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Magoni, M.; Donato, F.; Apostoli, P.; Rossi, G.; Comba, P.; Fazzo, L.; Speziani, F.; Leonardi, L.; Orizio, G.; Scarcella, C.; et al. Serum Levels of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Risk of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostoli, P.; Magoni, M.; Bergonzi, R.; Carasi, S.; Indelicato, A.; Scarcella, C.; Donato, F. Assessment of Reference Values for Polychlorinated Biphenyl Concentration in Human Blood. Chemosphere 2005, 61, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esser, A.; Schettgen, T.; Kraus, T. Assessment of a Potential PCB Exposure among (Former) Underground Miners by Hydraulic Fluids. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2020, 83, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiridena, W.; Wiegand, P.; Booth, M.; Lindelien, C. A Comparative Assessment of Low- and High-Resolution Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Methods for Polychlorinated Biphenyl Congener Analysis in Industry Wastewater. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 5, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, M.; Yu, L.; Liang, R.; Liu, W.; Dong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Ye, Z.; Wang, B.; et al. Associations of Polychlorinated Biphenyls Exposure with Plasma Glucose and Diabetes in General Chinese Population: The Mediating Effect of Lipid Peroxidation. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turci, R.; Finozzi, E.; Catenacci, G.; Marinaccio, A.; Balducci, C.; Minoia, C. Reference Values of Coplanar and Non-Coplanar PCBs in Serum Samples from Two Italian Population Groups. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 162, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, D.; Sverko, E. Analytical Methods for PCBs and Organochlorine Pesticides in Environmental Monitoring and Surveillance: A Critical Appraisal. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 709/2014 of 20 June 2014 Amending Regulation (EC) No 152/2009 as Regards the Determination of the Levels of Dioxins and Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 188, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkrabová, J.; Hrádková, P.; Hajšlová, J.; Poustka, J.; Nápravníková, M.; Poláček, V. Brominated Flame Retardants and Other Organochlorine Pollutants in Human Adipose Tissue Samples from the Czech Republic. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barontini, F.; Cozzani, V.; Petarca, L. Thermal Stability and Decomposition Products of Hexabromocyclododecane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 3270–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, P.; Yan, X.; Zhu, Q.; Qu, G.; Shi, J.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. A Review of Environmental Occurrence, Fate, and Toxicity of Novel Brominated Flame Retardants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13551–13569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turci, R.; Angeleri, F.; Minoia, C. A Rapid Screening Method for Routine Congener-specific Analysis of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Human Serum by High-resolution Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometric Detection. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2002, 16, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaee, M.; Backus, S.; Cannon, C. Potential Interference of PBDEs in the Determination of PCBs and Other Organochlorine Contaminants Using Electron Capture Detection. J. Sep. Sci. 2001, 24, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Aarøe Mørck, T.; Polcher, A.; Knudsen, L.E.; Joas, A. Review of the State of the Art of Human Biomonitoring for Chemical Substances and Its Application to Human Exposure Assessment for Food Safety. EFSA Support. Publ. 2015, 12, 724E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Angerer, J.; Ewers, U.; Kolossa-Gehring, M. The German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2007, 210, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaprio, A.P.; Tarbell, A.M.; Bott, A.; Wagemaker, D.L.; Williams, R.L.; O’Hehir, C.M. Routine Analysis of 101 Polychlorinated Biphenyl Congeners in Human Serum by Parallel Dual-Column Gas Chromatography with Electron Capture Detection. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2000, 24, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylander, C.; Lund, E.; Frøyland, L.; Sandanger, T.M. Predictors of PCP, OH-PCBs, PCBs and Chlorinated Pesticides in a General Female Norwegian Population. Environ. Int. 2012, 43, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpas, M.; Vakonaki, E.; Tzatzarakis, M.; Sifakis, S.; Alegakis, A.; Grigoriadis, T.; Sodré, D.B.; Daskalakis, G.; Antsaklis, A.; Tsatsakis, A. Organochlorine Pollutants’ Levels in Hair, Amniotic Fluid and Serum Sampless of Pregnant Women in Greece. A Cohort Study. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 73, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turci, R.; Balducci, C.; Brambilla, G.; Colosio, C.; Imbriani, M.; Mantovani, A.; Vellere, F.; Minoia, C. A Simple and Fast Method for the Determination of Selected Organohalogenated Compounds in Serum Samples from the General Population. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.; Suzuki, G.; Michinaka, C.; Yuan, B.; Takigami, H.; De Wit, C.A. Dioxin-like Activities, Halogenated Flame Retardants, Organophosphate Esters and Chlorinated Paraffins in Dust from Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden and China. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Yang, B.; Wang, D.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wen, S.; Li, J.; Shi, Z. Serum Levels of Novel Brominated Flame Retardants (NBFRs) in Residents of a Major BFR-Producing Region: Occurrence, Impact Factors and the Relationship to Thyroid and Liver Function. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, J.H.; Sellström, U.; Papadopoulou, E.; Padilla-Sánchez, J.A.; Haug, L.S.; De Wit, C.A. Serum Concentrations of Legacy and Emerging Halogenated Flame Retardants in a Norwegian Cohort: Relationship to External Exposure. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Mehdi, T.; Malik, R.N.; Eqani, S.A.M.A.S.; Kamal, A.; Dirtu, A.C.; Neels, H.; Covaci, A. Levels and Profile of Several Classes of Organic Contaminants in Matched Indoor Dust and Serum Samples from Occupational Settings of Pakistan. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porru, E.; Comito, R.; Kassouf, N.; Zappi, A.; Interino, N.; Fiori, J.; Melucci, D.; Violante, F.S. PCB Method Design of Experiments. Available online: https://amsacta.unibo.it/id/eprint/8629/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.