Abstract

Grinding is an essential process in mineral processing. Hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation, used to efficiently process refractory iron ores, can alter the physical and chemical properties of the ore, affecting its grinding characteristics. This paper uses iron ore from Baoshan, Shanxi Province, as the raw material for laboratory-scale hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation (HMPT) experiments and grinding tests. It examines the impact of four cooling methods on the ore’s grinding characteristics. The results show that samples cooled in a reducing atmosphere to 200 °C and then water-quenched exhibit the best relative grindability. For the same grinding time, the content of coarse-sized particles (+0.074 mm) in the product is lowest, while the fine-sized particles (−0.030 mm) is highest. The grinding kinetic parameters of the samples with this cooling method are the highest. After 2 min of grinding, the value of n is 1.3363, and the particle size distribution of the product is the most uniform. The BET and SEM test results indicate that samples with this cooling method have more internal pores, the largest pore size, and the most surface cracks and pores. This paper clarifies the effects of the HMPT cooling methods on grinding characteristics, providing a theoretical foundation for the efficient separation of iron ores.

1. Introduction

Iron ore resources are one of the important resources that sustain human life. It provides essential energy for production, living, and technological advancements [1,2,3]. China is one of the world’s leading iron ore producers. China’s annual iron ore reserves total 16.124 billion tons, primarily located in Liaoning, Sichuan, and Inner Mongolia [4]. Although our country has abundant iron ore resources, they are more scattered, have poorer geological conditions, and are harder to develop compared to those in other countries. As a result, domestic iron ore supply is insufficient, leading to heavy reliance on imports. Imports are primarily concentrated from countries like Australia and Brazil, creating a “straitened neck” problem that severely hampers economic development. Relevant scholars conducted a comprehensive analysis of China’s iron ore resource security issues from the perspectives of resources, markets and sustainable development [5,6]. They concluded that China’s iron ore resource security has reached a red alert level in recent years. Addressing the comprehensive utilization of low-grade iron ore with complex interbedding relationships, which are difficult to process, has become a critical issue for economic and social development [7,8,9].

Hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation (HMPT) is an efficient method for processing low-grade and difficult-to-select iron ores [10,11,12]. The basic principle is that under suitable conditions, weakly magnetic iron minerals (such as hematite, siderite, and limonite) are transformed into strongly magnetic ones through phase transformation. After grinding, the recovery rate in the magnetic separation process improves. Our research team has successfully developed both laboratory-scale and industrial-scale versions of this technology. Unlike traditional roasting, HMPT operates at a medium temperature range of 450–600 °C [13,14,15]. Hydrogen in HMPT has higher reduction efficiency and faster reaction kinetics than carbon monoxide, due to its larger specific surface area and pore volume, which enhance mass transfer and active site contact.

Researchers have focused on the effect of reaction temperature, time, gas composition, and their influence on the phase transformation of iron minerals and the recovery rate of concentrates [16]. Li et al. processed Hainan’s iron ore using the HMPT technology. After optimizing the reaction conditions, they obtained and iron concentrate with a 67.7% grade and 94.7% recovery [17]. Zhang et al. conducted hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation on complex oolitic hematite. Under optimal conditions, weakly magnetic iron minerals were transformed into high-intensity magnetic magnetite. After separation, an iron concentrate with 58.14% TFe content and 95.75% recovery was obtained. Additionally, the porous structure of the product facilitated dissociation during grinding [18]. The application of this process has also demonstrated the economic benefits of HMPT by increasing the iron recovery rate. Baogang Group has established a 160 wt/year high-efficiency processing technology (HMPT) production line that extracts iron concentrate and recovers rare earth elements and fluorite from Bayan Obo ore [19,20]. Additionally, its 60 wt/year iron-manganese ore phase transformation project in Zambia has increased iron recovery by over 10 percentage points [21]. By inducing thermal microcracks during phase transformation, HMPT reduces grinding energy consumption and enhances mineral liberation efficiency, demonstrating advantages in the beneficiation of complex polymetallic ores [22,23]. However, very few studies have focused on the grinding characteristics of ore treated with HMPT, particularly the critical influence of the cooling method after the reaction on the properties of the ore and subsequent grinding efficiency. Most previous research has overlooked the cooling stage as a potential factor for optimizing grindability, leading to a limited understanding of how the physical and chemical properties of the ore, altered by cooling, affect grinding kinetics and particle size uniformity. This research gap has hindered the full integration of HMPT with subsequent grinding and separation processes, preventing the achievement of efficient mineral processing.

This study used the pre-enriched iron ore concentrate from Shanxi Baoshan mine as raw material. A laboratory-scale horizontal tubular furnace and a vertical stirred mill were used for hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation and grinding, respectively. Four cooling methods were designed to process the phase transformation products. The effects of cooling methods on the ore’s reducibility and grinding kinetics were investigated. The influence of cooling methods on the ore’s pore structure and surface microstructure was studied using BET and SEM. This provided theoretical guidance for improving the grinding characteristics of phase transformation products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

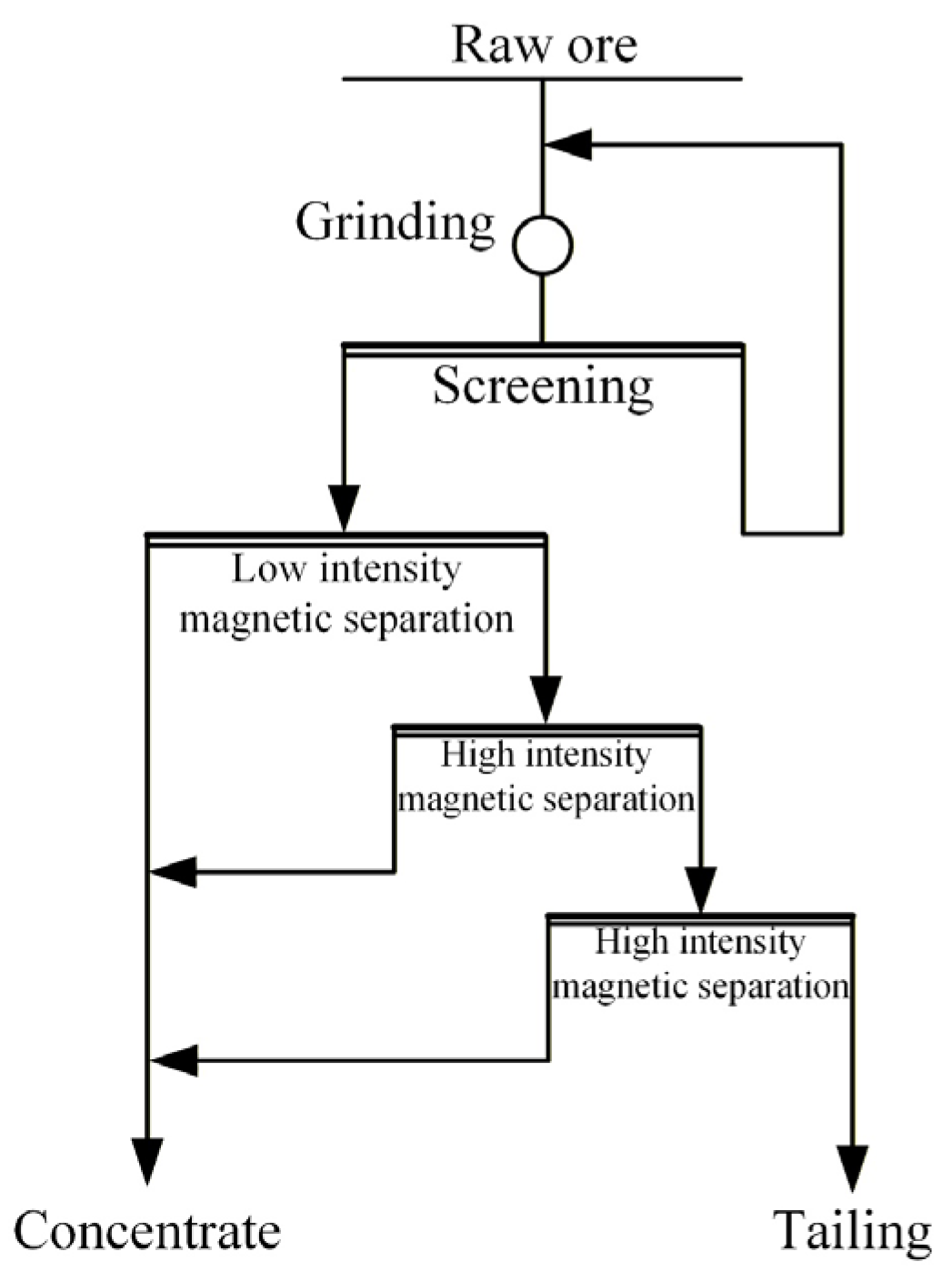

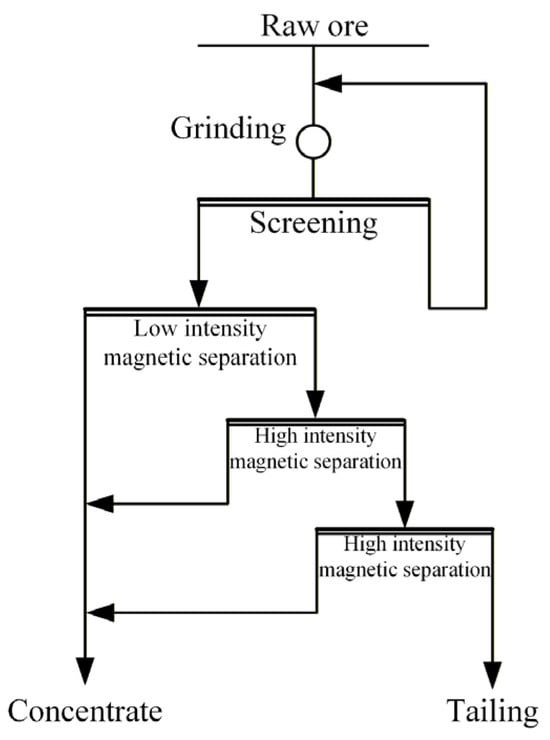

The raw ore utilized in this experiment was supplied by Shanxi Banshan Mining Co., Ltd., Xinzhou, China. Initially, the ore underwent two stages of closed-circuit crushing for pre-enrichment, aimed at preparing continuous test samples of the pre-enriched concentrate, as illustrated in Figure 1. The continuous pre-enrichment test process consists of grinding, low-intensity magnetic separation, and two-stage high-intensity magnetic separation. The test was conducted under the following conditions: grinding fineness of −0.074 mm with 60 passing, low-intensity magnetic separation field intensity of 1000 Oe, first-stage high-intensity magnetic separation field intensity of 5000 Oe, and second-stage high-intensity magnetic separation field intensity of 11,000 Oe. The resulting pre-enriched iron concentrate had an iron grade of 32.35% and an iron recovery of 92.20%.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the continuous pre-enrichment experimental process flow.

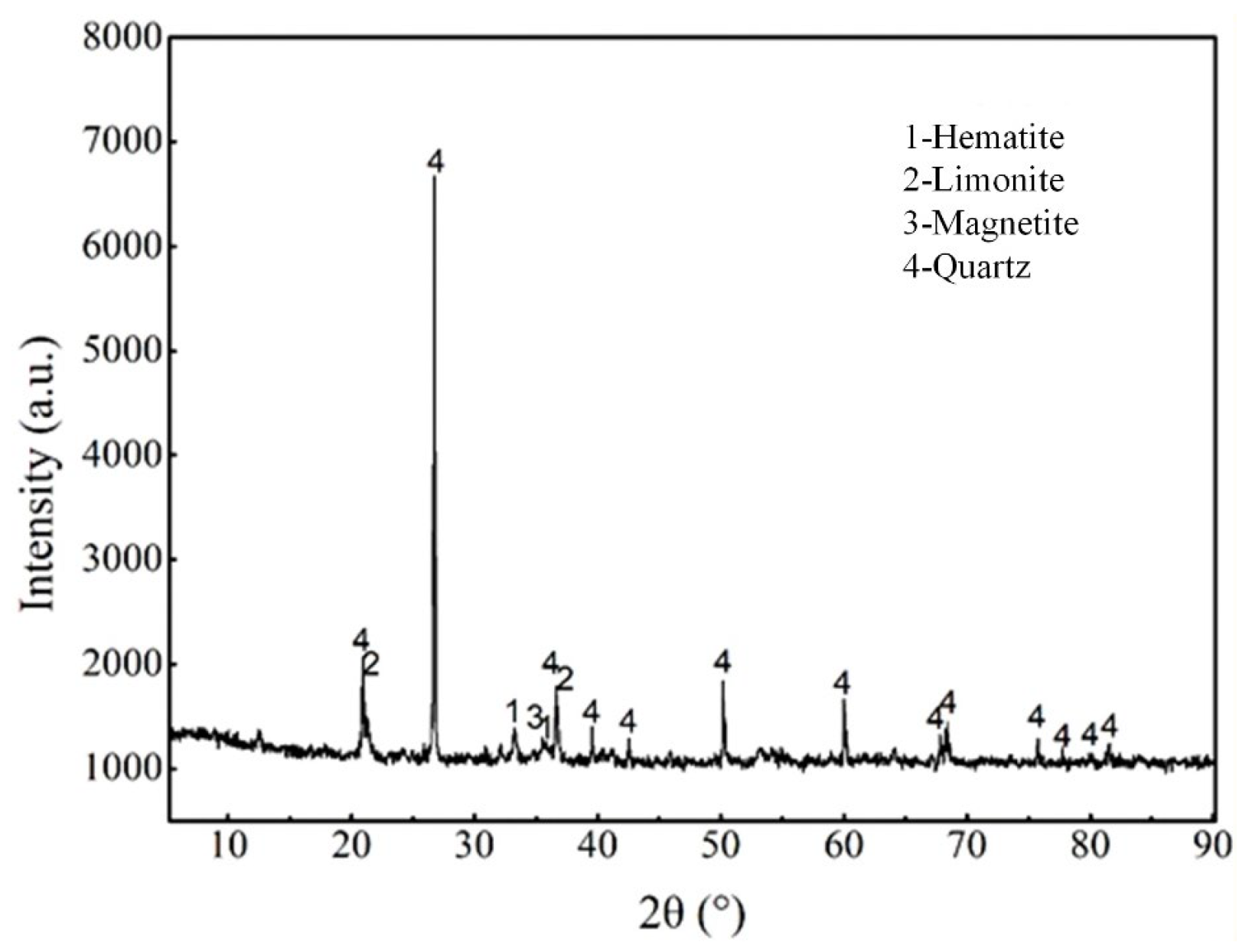

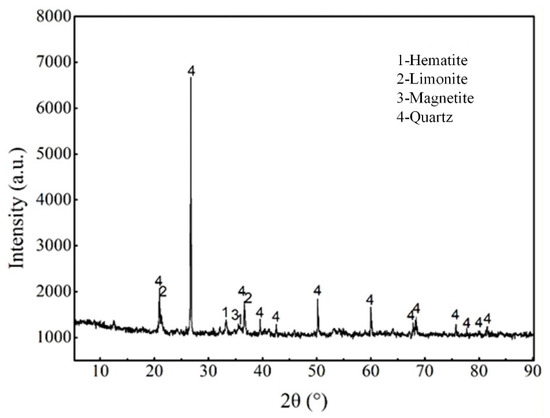

The chemical composition analysis of the pre-enriched concentrate sample is presented in Table 1. The analysis shows that the TFe content is 32.37%, with FeO content at 4.10%. The main impurity is SiO2, with a content of 36.36%, followed by other impurities: Al2O3 of 1.90%, CaO of 2.65%, and MgO of 1.30%. The harmful elements, P and S, have content of 0.047% and 0.135%, respectively. The loss on ignition is 9.01%, primarily caused by the dehydration of limonite and the decomposition of carbonate minerals. In addition, the X-ray diffraction analysis of the pre-enriched concentrate samples is shown in Figure 2. The study indicates that the iron minerals in the samples are predominantly hematite, with minor amounts of limonite and magnetite. The gangue minerals are mainly quartz.

Table 1.

Chemical composition analysis of pre-enriched concentrate samples (%).

Figure 2.

XRD analysis of pre-enriched concentrate sample.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Hydrogen-Based Mineral Phase Transformation Experiment

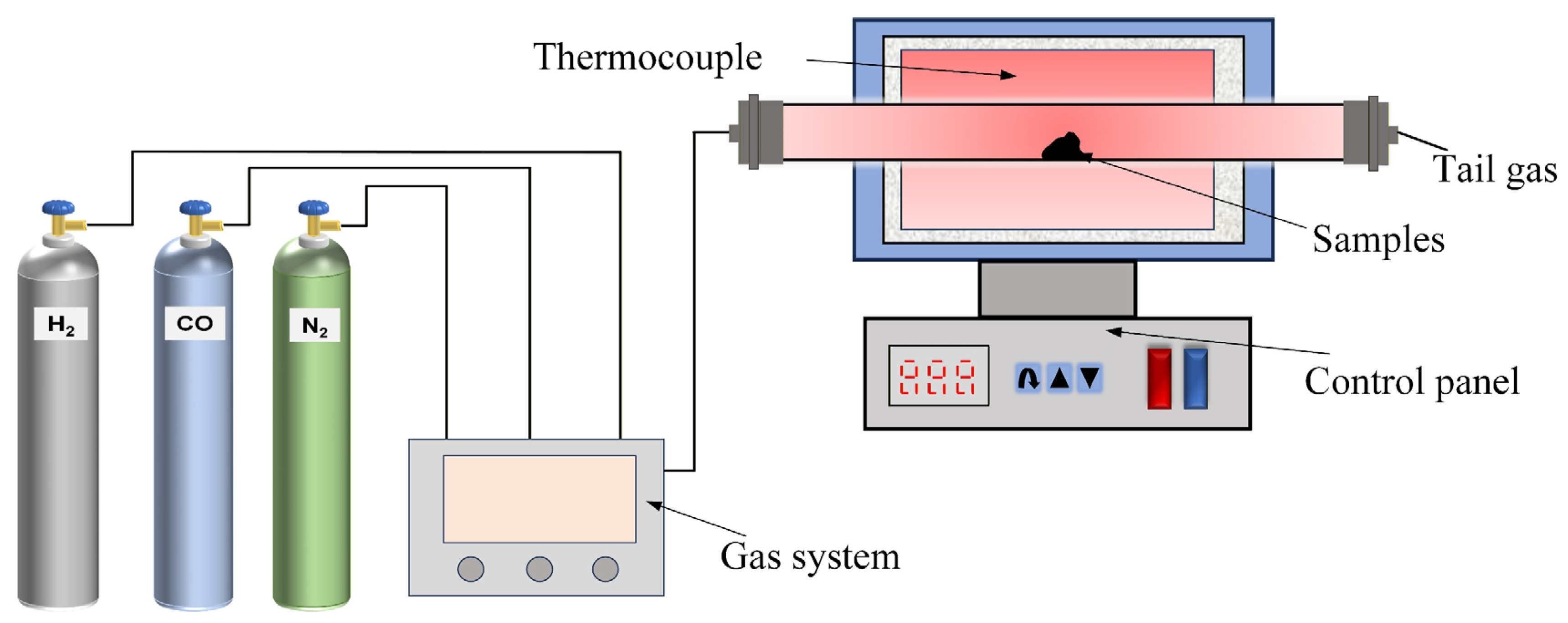

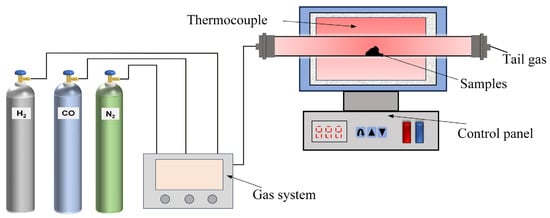

The hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation (HMPT) test was performed in a laboratory-scale horizontal roasting furnace (is provided by Hefei Kejing Materials. Co., Ltd., Hefei, China), as shown in Figure 3. The device comprises three main components: the roasting furnace, the gas supply system, and the control system. The specific steps of the experiment are as follows: For each trial, an appropriate amount of ore sample is weighed, then placed into the roasting tube, and N2 is introduced to expel the air. When the roasting furnace reaches the set temperature, the reduced gas at the preset flow rate is introduced, and timing begins. When the reaction reaches the set time, the reduced gas is turned off, and the ore sample is cooled using various methods before being used as grinding raw material. Based on preliminary experiments, the experimental conditions for the hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation were determined as follows: reaction temperature of 540 °C, reaction time of 20 min, reduced gas concentration of 30% (CO:H2 = 2:1), and total gas volume of 70 mL/min.

Figure 3.

Hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation test system. Reprinted from [24].

After the HMPT reaction (540 °C, 20 min), four cooling modes with different cooling rates and temperature gradients were developed, taking into account industrial feasibility and the necessity to differentiate the chemical changes in the mineral structure. Cooling mode I (reduction atmosphere cooling): in this mode, the flow of reducing gas (CO:H2 = 2:1) is maintained after the reaction, allowing the sample to cool naturally to room temperature (25 °C). The cooling rate is set at 5 °C/min. This mode simulates the slow cooling process utilized in industrial settings to prevent thermal stress and serves a benchmark for comparing oxidation and structural stability. Cooling mode II (reduction atmosphere at 200 °C + water quenching): in this mode, the sample is first cooled to 200 °C in the reducing gas (cooling rate is 8 °C/min), and then rapidly quenched in water at 25 °C. The total cooling rate for this process is 45 °C/min. Cooling mode III (natural air cooling): after the reaction, all gas flows are halted, and the sample is removed to cool in ambient air at 25 °C with a relative humidity of 50%. The cooling rate is 12 °C/min. Cooling mode IV (direct water quenching): after halting the reaction, the sample at 540 °C is immediately immersed in water at 25 °C, resulting in a cooling rate of 60 °C/min. This mode examines the effects of extremely rapid cooling on the ore’s structure and allows for comparison with the staged cooling mode (mode II).

2.2.2. Grinding Experiment

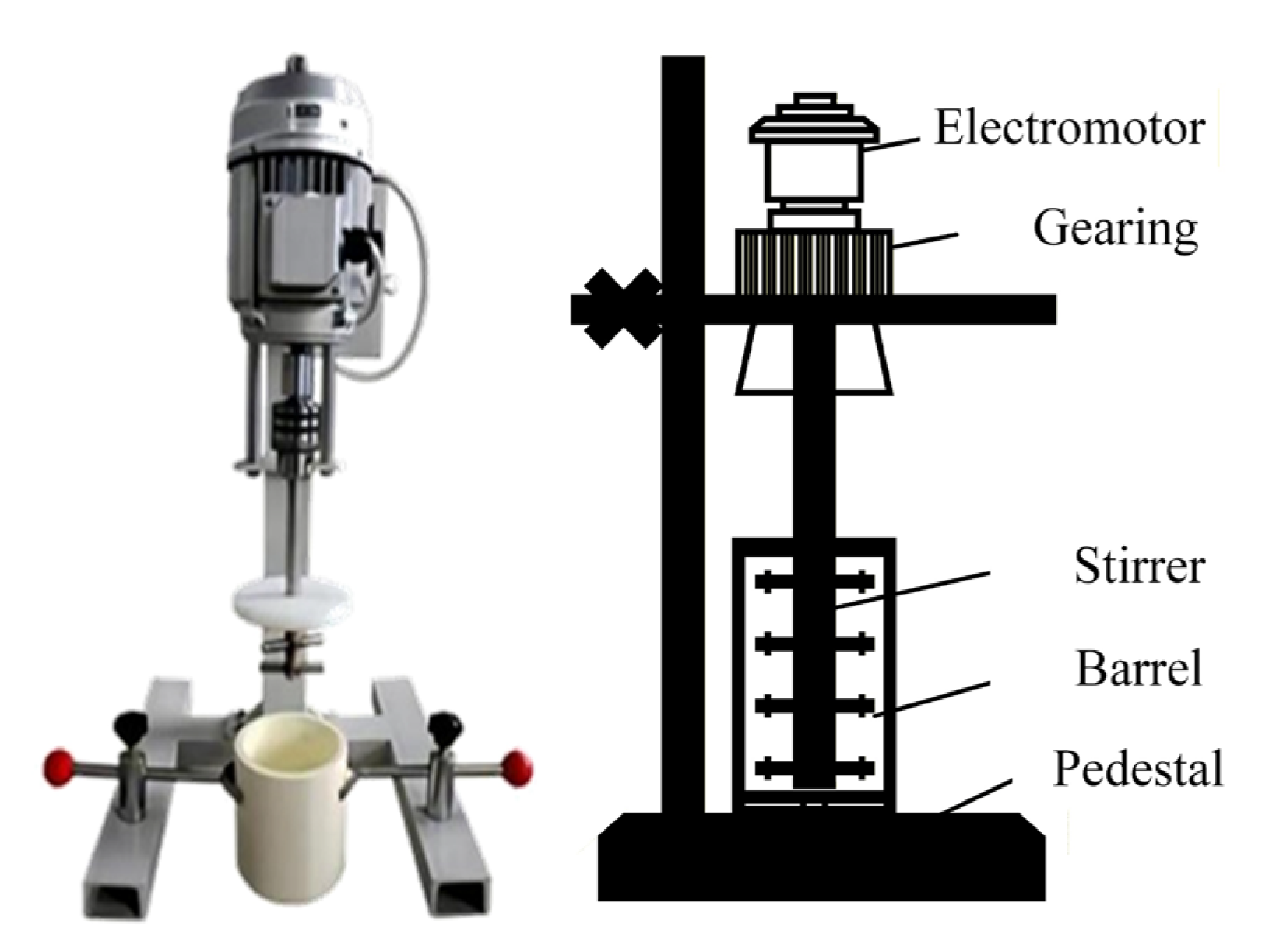

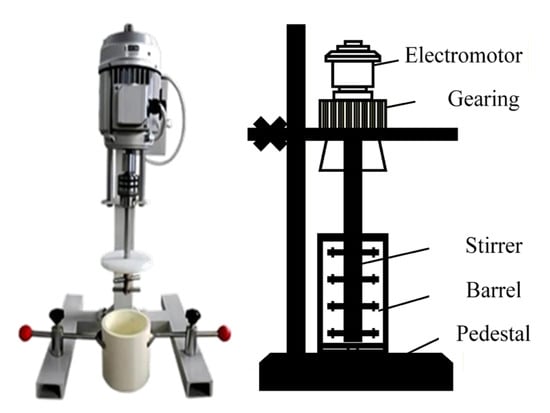

The grinding test equipment used is a JM-type laboratory stirring mill (is provided by Changsha Tianchuang Powder Technology, Co., Ltd., Changsha, China), as shown in Figure 4. It mainly consists of an electric motor, a transmission device, a stirrer, a cylindrical body, and a base. The model of the mixer mil is JM-3L, featuring an adjustable speed range from 50 to 1400 rpm, and a volume capacity of 3L. It is equipped with a motor power of 0.37 KW, and the grinding cylinder is constructed from corundum. Before grinding, it is essential to prepare the required tools and sample, adjust the parameters of the agitated mill, and operate the mill at idle speed for 3 min to clean both the mill and the grinding media. During the test, based on the grinding conditions outlined in Table 2, an appropriate amount of grinding media (ceramic balls), the material to be ground, and water were successively added to the grinding mill cylinder. Finally, the remaining ceramic balls were added, the stirrer and cylinder were secured, the grinding time was set, and the switch was turned on. After the grinding process was complete and the machine stopped, the ore was discharged. The obtained pulp was sieved, dried, and weighed to determine the particle size distribution of the grinding product.

Figure 4.

JM stirring mill for laboratory-scale.

Table 2.

Grinding conditions.

2.2.3. Particle Size Distribution Characteristics

In this study, the parameters of the Rosin-Rammler (R-R) particle size distribution equation were used to analyze the particle size distributin characteristics of the samples, calculate the particle size uniformity index and other characteristic parameters, and deter mine the optimal grinding process parameters [25,26]. The R-R equation is shown in Equation (1).

where d represents the particle diameter or sieve aperture, measured on micrometers; R0 is the cumulative content of particles larger than d, expressed as a percentage; b is a particle characteristic parameter related to the product’s particle size; and n is the homogeneity index, which indicates the uniformity of the product’s particle size distribution. The previous study’s findings on the relationship between the b and n values indicate that the b and n values of the product exhibit opposite trends. Specifically, as the b value increases, the n value decreases. As the n value increases, the particle size range becomes narrower and the material’s particle size distribution becomes more uniform. Conversely, as the n value decreases, the particle size distribution becomes more dispersed and less uniform.

3. Results and Discussion

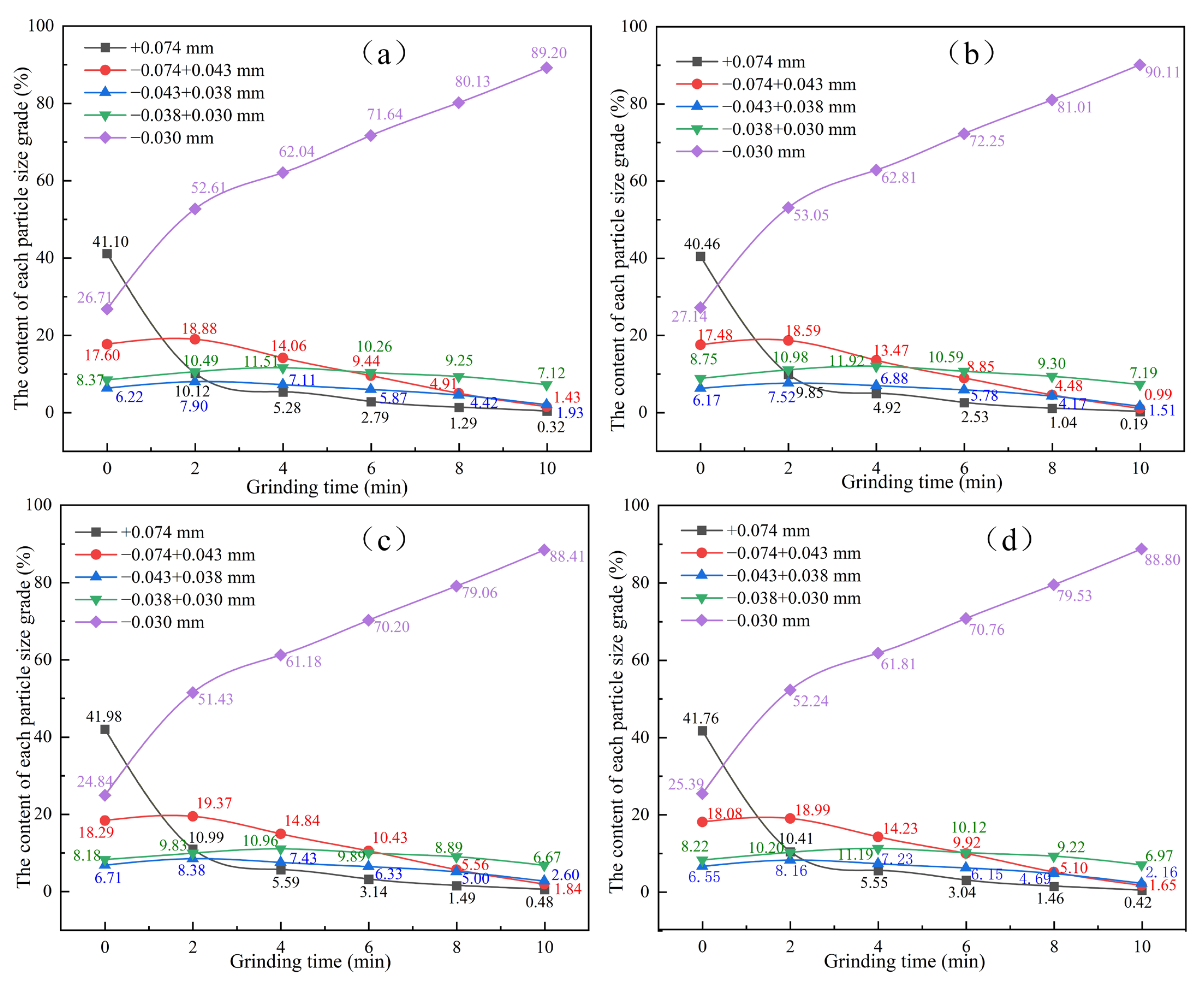

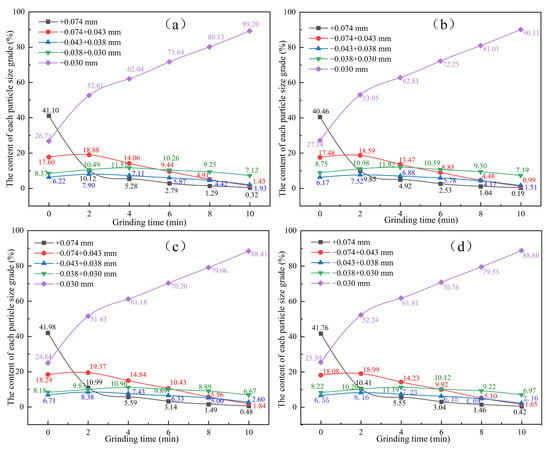

3.1. Effect of Cooling Methods on Relative Grindability

To visually analyze the grinding characteristics of HMPT products obtained through different cooling methods, grinding tests were conducted for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 min, as specified by the grinding conditions in Table 2. Overall, as the grinding process progresses, the content of the finest particle size (−0.30 mm) in the grinding product increases, while the content of the coarser particle size (+0.074 mm) decreases. The content of intermediate particle sizes increases initially and then decreases slightly. Comparative analysis showed that after 10 min of grinding, the +0.074 mm content in the four cooled grinding products decreases to 0.32%, 0.19%, 0.48% and 0.42%, respectively, while the −0.030 mm content increases to 89.20%, 90.11%, 88.41%, and 88.80%, respectively. It is observed that the second cooling method results in the lowest content of coarser particles and a significantly higher content of finer particles compared to the other cooling methods.

Specifically, as shown in Figure 5a, for the hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation products obtained using the first cooling method, after 2 min of grinding, the content of +0.074 mm rapidly decreased from 41.10% to 10.12%. The content of −0.074 + 0.043 mm increased from 17.60% to 18.88%; the content of −0.043 + 0.038 mm increased from 6.22% to 7.90%; the content of −0.038 + 0.030 mm increased from 8.37% to 11.51%; and the content of the smallest particle size, −0.030 mm, increased from 26.71% to 52.61%. As shown in Figure 5b, for the hydrogen-based mineral products from phase conversion obtained using the second cooling method, after 2 min of grinding, the content of +0.074 mm rapidly decreased from 40.46% to 9.85%; the content of −0.074 + 0.043 mm increased from 17.48% to 18.59%; the content of −0.043 + 0.038 mm increased from 6.17% to 7.52%; the content of −0.038 + 0.030 mm increased from 8.75% to 10.98%; and the content of the smallest particle size, −0.030 mm, increased from 27.14% to 53.05%. As shown in Figure 5c, for the hydrogen-based mineral products from phase conversion obtained using the third cooling method, after 2 min of grinding, the content of +0.074 mm decreased from 41.98% to 10.99%; the content of −0.074 + 0.043 mm increased from 18.29% to 19.37%; the content of −0.043 + 0.038 mm increased from 6.71% to 8.38%; the content of −0.038 + 0.030 mm increased from 8.18% to 9.83%; and the content of the smallest particle size, −0.030 mm, increased from 24.84% to 51.43%. As shown in Figure 5d, for the hydrogen-based mineral phase conversion products obtained using the fourth cooling method, after 2 min of grinding, the content of +0.074 mm decreased from 41.76% to 10.41%; the content of −0.074 + 0.043 mm increased from 18.08% to 18.99%; the content of −0.043 + 0.038 mm increased from 6.55% to 8.16%; the content of −0.038 + 0.030 mm increased from 8.22% to 10.20%; and the content of the smallest particle size, −0.030 mm, increased from 25.39% to 52.24%. In addition, as the grinding time increases from 2 min to 10 min, the rate of change slows down. Based on the reduction in coarse particle content and the increase in fine particle content, it can be concluded that the HMPT products treated by the second cooling method exhibit better relative grindability.

Figure 5.

The influence of different cooling methods on the particle size distribution of the grinding products. (a) cooling mode I, (b) cooling mode II, (c) cooling mode III, and (d) cooling mode IV.

From the above analysis results, it can be concluded that the grinding performance of ore treated by HMPT directly depends on the physical and chemical properties of the ore, with the cooling method after the reaction having a significant regulatory effect on these properties. The results that among the four cooling methods, cooling mode II produced the lowest content of coarse particles and the highest content of fine particles. This enhanced grindability may be attributed to the microcracks induced by thermal stress. During the cooling process, the temperature gradient between the surface and the interior the ore generates thermal stress. In cooling mode II, the ore is first cooled to 200 °C in a reducing atmosphere and then rapidly quenched with water. The difference in thermal expansion coefficients between iron ore and gangue minerals amplifies this thermal stress during rapid cooling. As a result, a significant number of microcracks form, which reduces the energy required for particle fragmentation during the grinding process and promotes the formation of fine particles. In contrast, cooling mode I involves a slow cooling process, resulting in minimal thermal stress and smaller microcracks, which have a relatively minor impact on grindability. Cooling modes III and IV are adversely affected by insufficient oxidation of magnetite and inadequate formation of microcracks, respectively, leading to poor grindability of the ore.

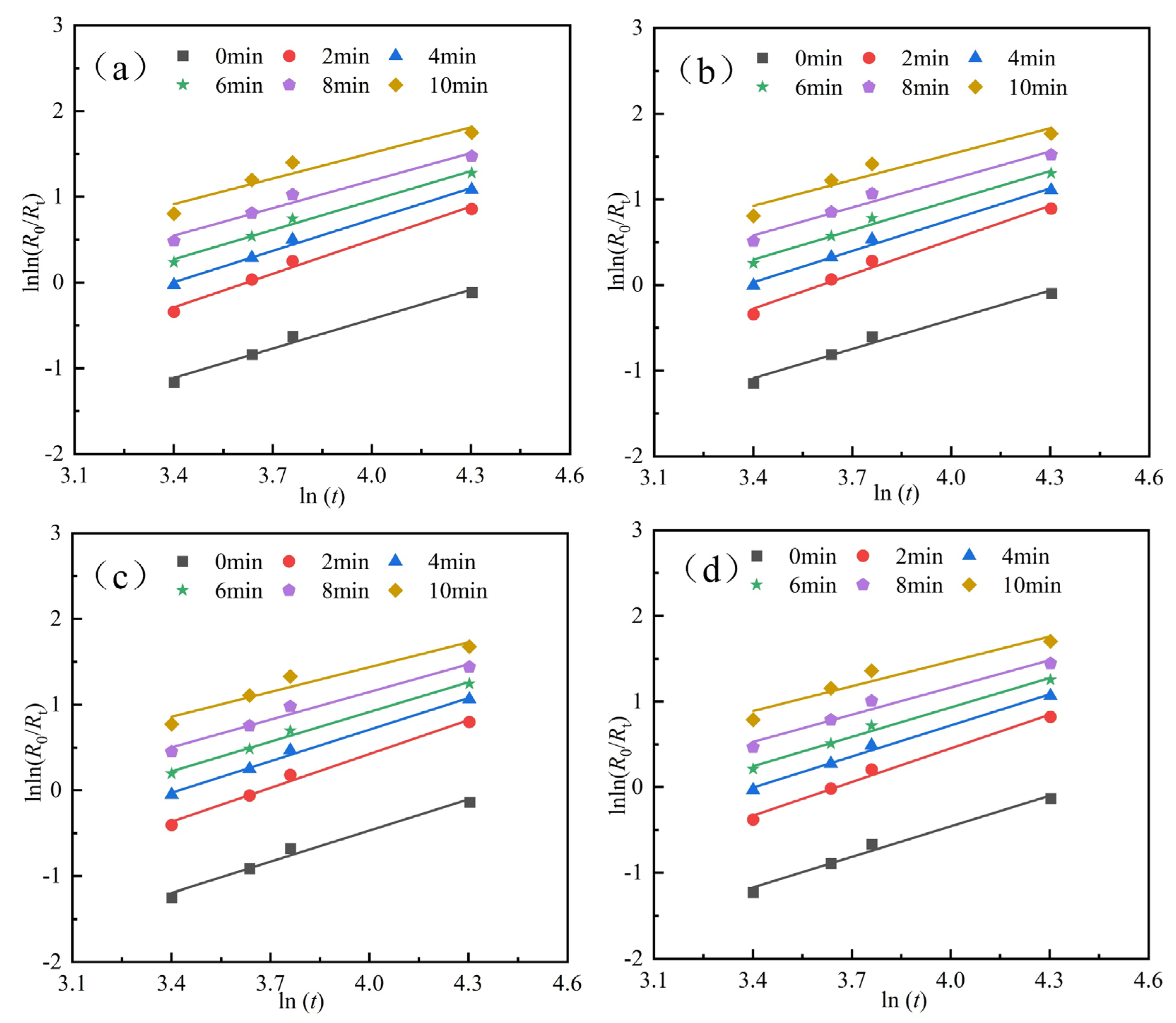

3.2. Effect of Cooling Methods on Grinding Kinetics

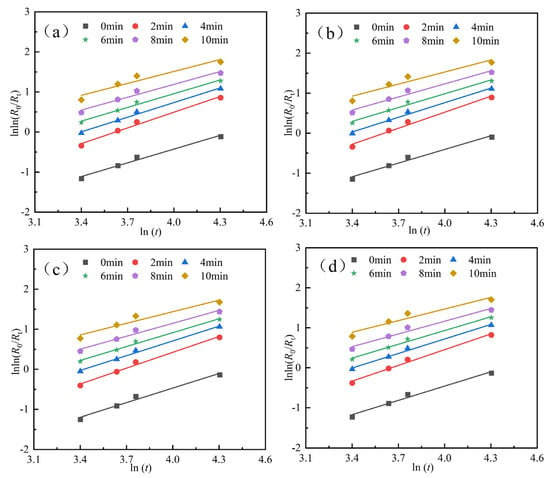

To further analyze the influence of cooling methods on the grinding characteristics of materials, the particle size distribution of the grinding products at different grinding time was fitted using Equation (1). The fitting process is illustrated in Figure 6. The grinding kinetic parameters for products processed with different cooling methods are presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The fitting optimization parameter R2 is consistently greater than 0.95, indicating that the fitting quality meets the required standards.

Figure 6.

Fitting results of sample particle size characteristics under different cooling methods. (a) cooling mode I, (b) cooling mode II, (c) cooling mode III, and (d) cooling mode IV.

Table 3.

Analysis of particle size characteristics of samples under cooling mode I.

Table 4.

Analysis of particle size characteristics of samples in cooling mode II.

Table 5.

Analysis of particle size characteristics of samples in cooling mode III.

Table 6.

Analysis of particle size characteristics of cooling mode IV sample.

Figure 6a and Table 3 show that the parameters of the grinding particle size characteristic equation obtained using cooling mode I exhibit different trends as the grinding time increases. Specifically, the uniformity index n increases and then decreases as the grinding process progresses, while the particle characteristic parameter b increases with grinding time. After 2 min of grinding, the uniformity index n reaches its maximum value of 1.3063, and the optimal uniformity of the grinding product is achieved. Based on the corresponding particle characteristic parameter b value of 0.0088, the R-R particle size characteristic equation, as shown in Equation (2), is further derived.

Figure 6b and Table 4 show that the uniformity index n in the grinding particle size characteristic equation obtained using cooling mole II exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing as the grinding time increases. The particle characteristic parameter b increases gradually. Moreover, the uniformity index n reaches its maximum value of 1.3363 after 2 min of grinding, with the corresponding particle characteristic parameter b value of 0.0080. The corresponding R-R particle size characteristic equation is given in Equation (3).

Figure 6c and Table 5 show that the uniformity index n in the grinding particle size characteristic equation obtained using cooling mode III exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing as the grinding time increases. The particle characteristic parameter b increases gradually. Additionally, the uniformity index n reaches its maximum value of 1.3190 after 2 min of grinding, with the corresponding particle characteristic parameter b value of 0.0078. The corresponding R-R particle size characteristic equation is given in Equation (4).

Finally, Figure 6d and Table 6 show that the uniformity index n in the grinding particle size characteristic equation obtained using cooling mode IV exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing as the grinding time increases. The particle characteristic parameter b increases gradually. Additionally, the uniformity index n reaches its maximum value of 1.3109 after 2 min of grinding, with the corresponding particle characteristic parameter b value of 0.0083. The corresponding R-R particle size characteristic equation is given in Equation (5).

Overall, the comparison reveals that, for the same grinding time, the kinetic parameter n corresponding to cooling mode II is the largest, indicating superior uniformity.

The results from the grinding kinetics model indicate that the uniformity coefficient n for cooling mode II is highest, signifying the most uniform particle size distribution. The n value reflects the consistency of particle fragmentation during the grinding process, which is closely related to the mechanical properties and structural uniformity of the ore. In cooling mode II, the combination of a larger average pore size and abundant microcracks ensures that the ore is crushed more uniformly during grinding. The cracks expand uniformly under mechanical stress, thereby preventing the formation of excessively coarse or excessively fine particles. The grinding time exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing, with the cooling method influencing both the magnitude and rate of this trend. During the initial stage of grinding, the number of surface cracks and pores in the ore increases, resulting in a more uniform crushing speed and an increase in the value of n. As grinding progresses, the remaining particles possess greater structural integrity, causing the rate of crack expansion to slow down, which leads to a gradual decrease in the value of n. Cooling mode II maintains a relatively high value of n throughout the grinding process because its initial crack and pore structure is more conducive to continuous and uniform crushing.

3.3. Effect of Cooling Methods on Physical and Chemical Properties

The hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation is a complex physical and chemical process [20]. Different cooling methods induce variations in the physical and chemical properties of the ore, leading to differences in the grinding characteristics of the processed ore. Therefore, analyzing the impact of cooling methods on the physical and chemical properties of hydrogen-based mineral phase products is crucial for further research into the mechanisms. This study focused on analyzing the pore size characteristics and microscopic morphology of the products using tests such as BET and SEM.

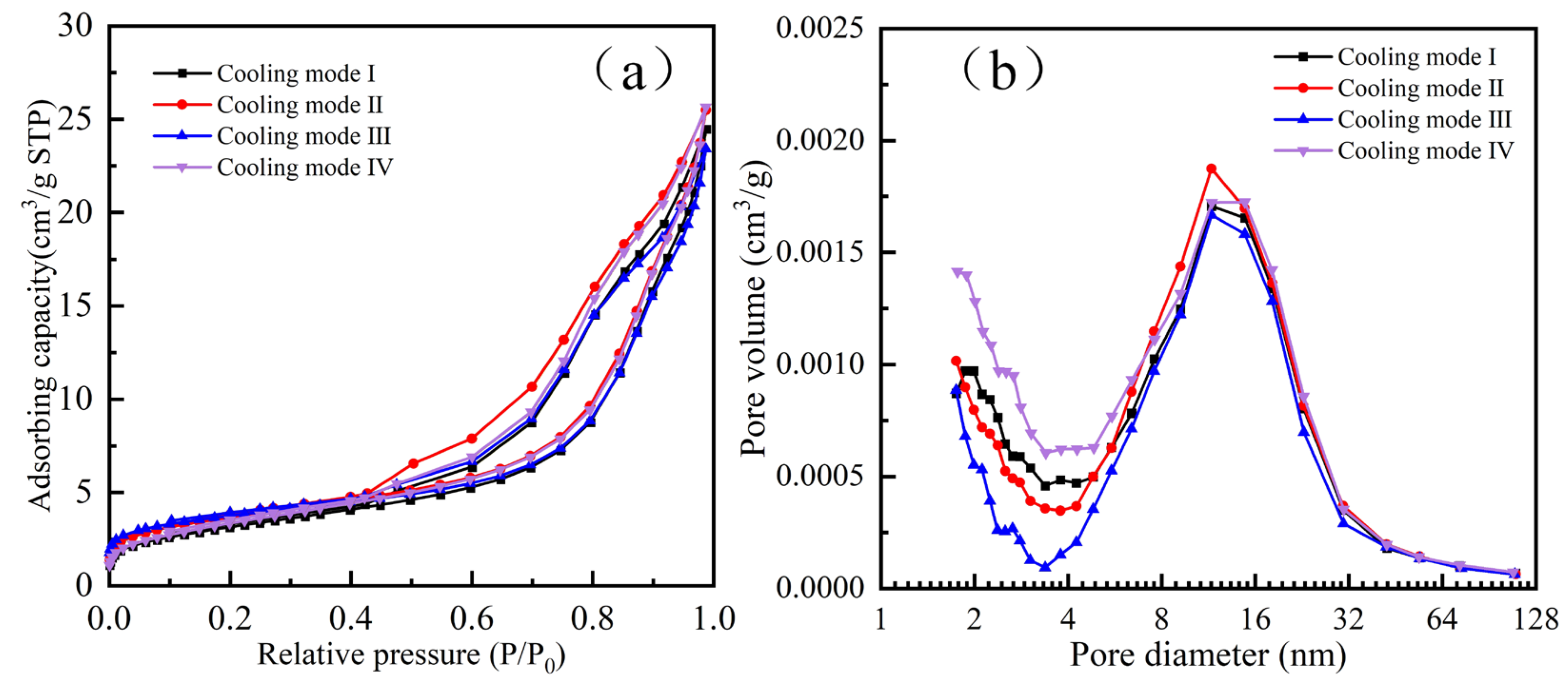

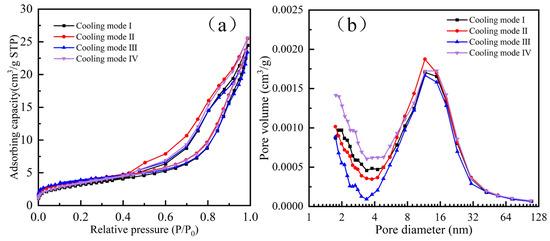

Table 7 presents the BET analysis results of the products following hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation under different cooling methods. According to Table 7, the products obtained by different cooling methods, ranked from largest to smallest in specific surface area, are: cooling method IV > I > III > II. In terms of total pore volume, from largest to smallest, the ranking is: III > I > II > IV. For average pore diameter, from largest to smallest, the ranking is: II > III > IV > I.

Table 7.

BET analysis of different cooling products after hydrogen mineral phase transformation.

Figure 7 presents the adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution diagrams of the products obtained after hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation under different cooling methods. As shown in Figure 7a, the adsorption–desorption isotherms of the products obtained via different cooling methods exhibit distinct hysteresis loops, all classified as H3 type. The H3-type hysteresis loop primarily indicates the presence of mesopores or macropores. Figure 7b shows that, by comparing micropore volume (pore diameter < 2 nm), the water-quenched–cooled samples subjected to water immersion cooling to 200 °C contain the highest number of micropores, while the water-quenched–cooled samples contain the fewest. In terms of mesopore volume (2 nm < pore diameter < 100 nm), the reducing atmosphere-cooled samples contain the largest number of mesopores, whereas the water-quenched–cooled samples contain the fewest. Comparing the total pore diameter reveals that the water-quenched–cooled samples, after cooling to 200 °C in a reducing atmosphere, exhibit a larger number of pores with the largest diameter, which is more conducive to improving subsequent grinding efficiency.

Figure 7.

BET analysis of different cooling products after mineral phase transformation. (a) N2 adsorption-desorption curves and (b) pore size distribution.

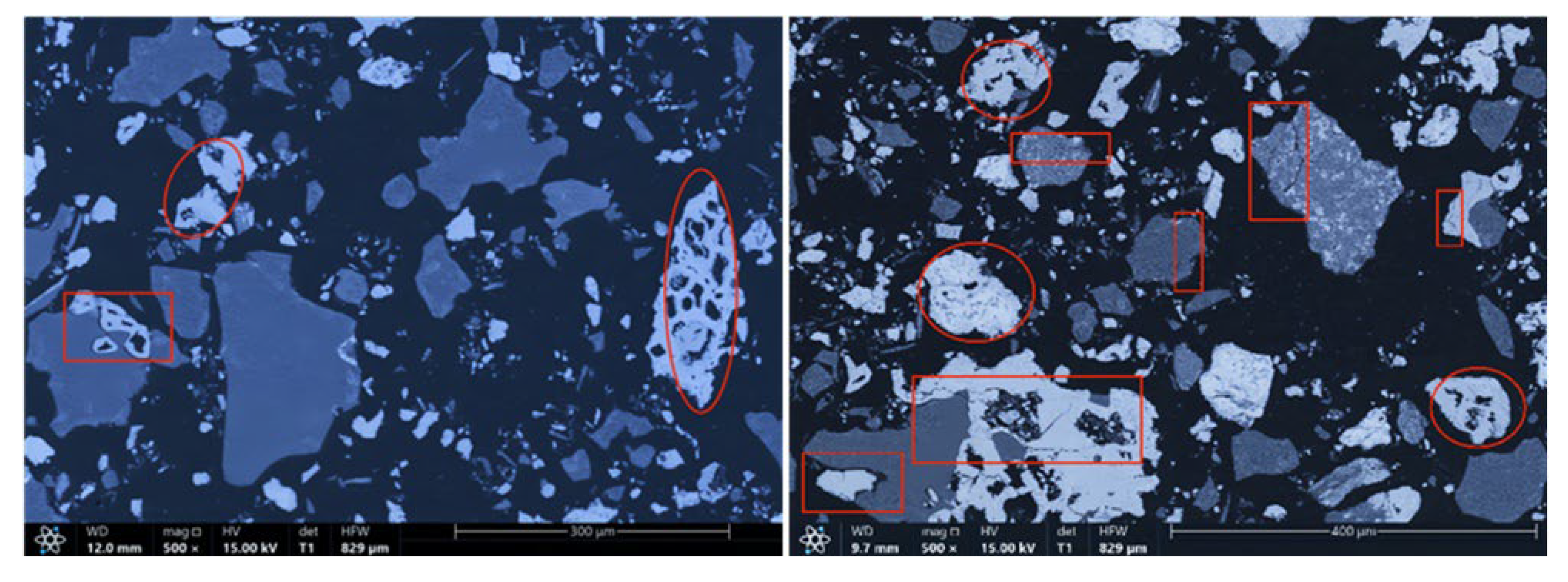

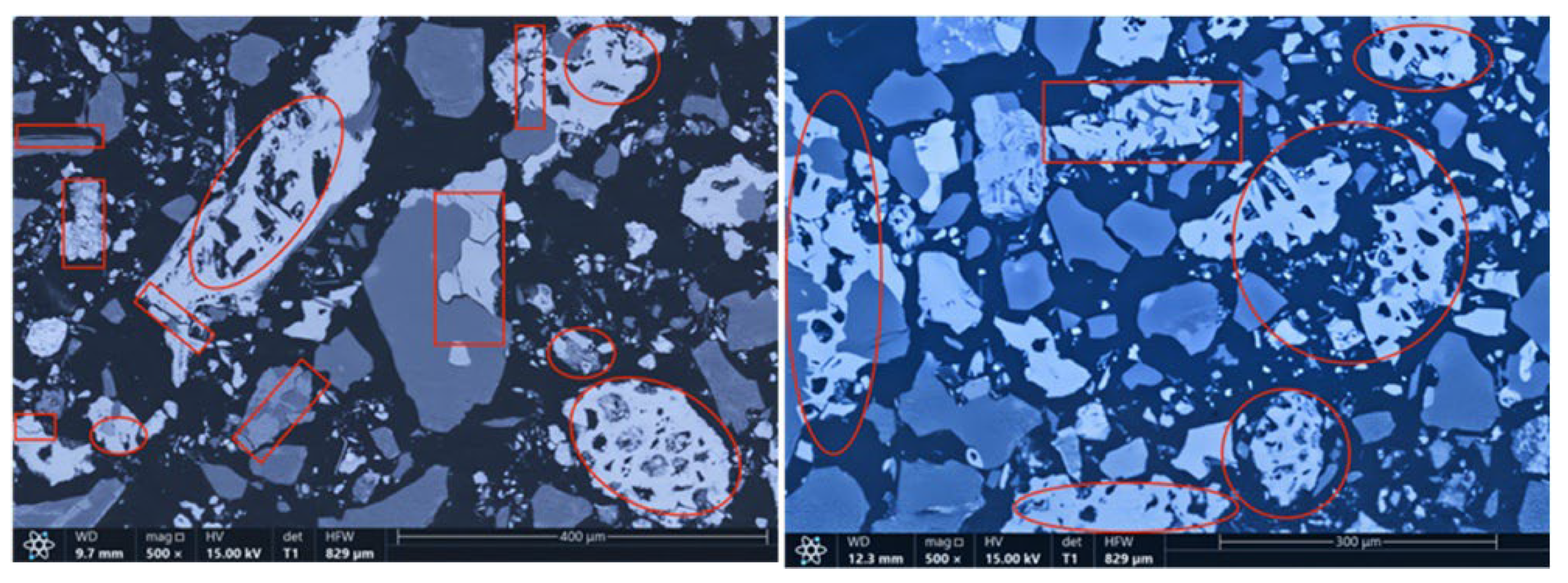

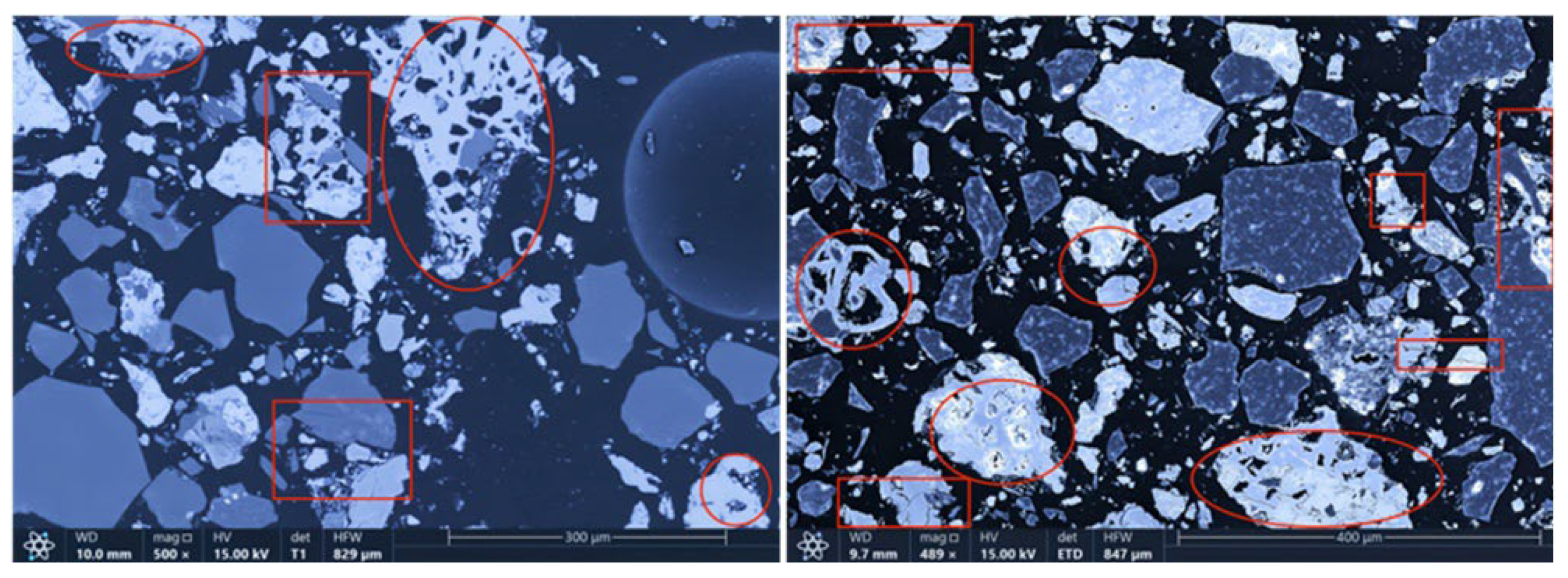

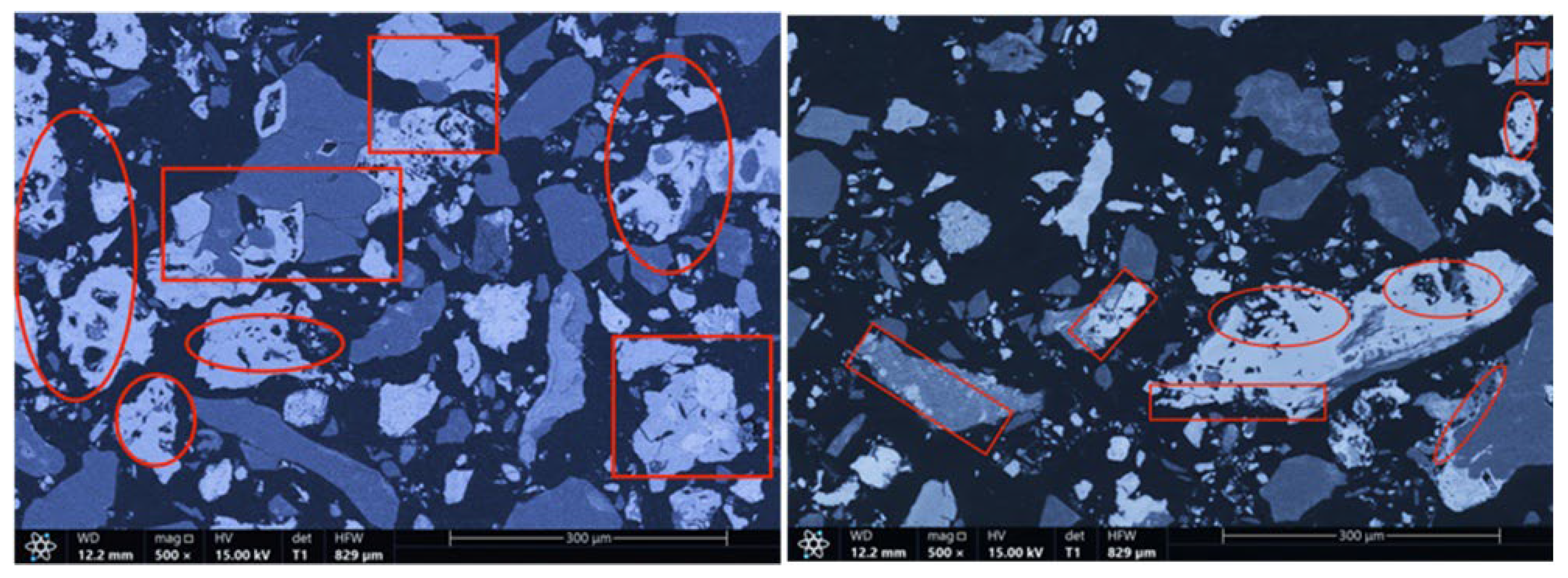

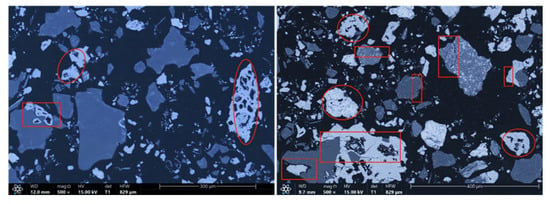

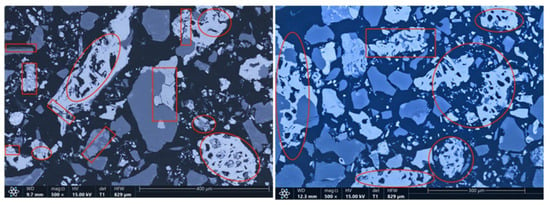

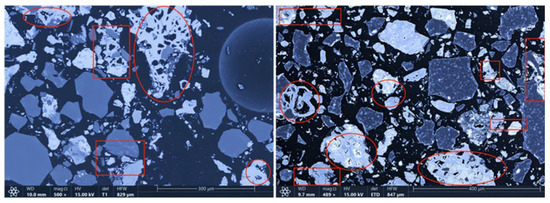

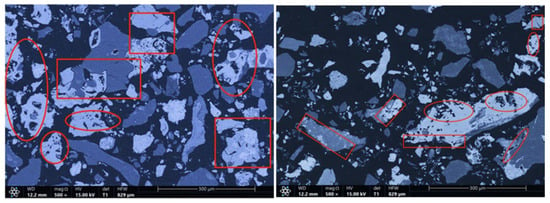

The microstructures of the products obtained via different cooling methods were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with the results presented in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. As shown in the figures, the number of cracks and micropores on the surface of the ore particles varies with the cooling method. Ore particles treated with water quenching after cooling to 200 °C in a reducing atmosphere exhibit the highest number of cracks and pores. Studies have shown that during the rapid quenching and cooling process following hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation, differences in thermal properties among the minerals in the ore induce stress at mineral interfaces, leading to contraction and the formation of microcracks. The presence of microcracks increases the degree of monomer dissociation and the exposed surface area of iron minerals during subsequent grinding. Consequently, the water-quenched–cooled samples exhibit more cracks and pores than the reduced-atmosphere-cooled samples.

Figure 8.

Microstructure of reduced gas-cooled sample.

Figure 9.

Microstructure of samples cooled to 200 °C by reducing gas and then water quenching.

Figure 10.

Microstructure of samples cooled to 200 °C by water shower and then by water quenching.

Figure 11.

Microstructure of water-quenched–cooled sample.

In addition, restoring the reducing atmosphere further reduces the mineral phase conversion products, whereas natural cooling leads to magnetite oxidation. The most intense phase transformations in the mineral phase conversion products occur within the 400–500 °C. At this temperature range, exposure to air causes Fe3O4 to oxidize to form α-Fe2O3. Hematite has significantly higher hardness and Young’s modulus than magnetite, so the oxidation of Fe3O4 increases the hardness and modulus of the mineral phase conversion products, reducing their grindability and impairing grinding characteristics. In the water quenching process, magnetite in the mineral phase conversion products experiences slight oxidation. However, if the mineral phase conversion products are sealed and cooled below 400 °C before exposure to air, Fe3O4 remains largely unoxidized. Therefore, water quenching after reducing the atmosphere to 200 °C effectively prevents the newly formed magnetite from oxidizing into harder, denser hematite, preserving the beneficial effects of hydrogen-based mineral phase conversion on the grinding characteristics of iron ore. Additionally, samples cooled by reducing the atmosphere to 200 °C and then water quenched exhibit the highest number of cracks and pores in the mineral particles. Therefore, this cooling method is more suitable for subsequent grinding, dissociation, and separation operations than the other three methods discussed in this paper.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the effects of four HMPT post-cooling methods on the grinding characteristics of refractory iron ores. It clarified the regulatory role of the cooling methods on these characteristics and revealed that changes in pore structure and microstructure induced by cooling are key factor affecting grinding performance. The main research conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The +0.074 mm particle size content in the different cooling samples decreased gradually with increased grinding time. The contents of the −0.074 + 0.043 mm, −0.043 + 0.038 mm, and −0.038 + 0.030 mm particle size grades initially increased and then decreased with grinding time, while the −0.030 mm particle size grade content steadily increased.

- (2)

- The analysis of particle size characteristics shows that, compared to the other three cooling methods, the particle size uniformity index (n value) of samples cooled in a reducing atmosphere to 200 °C and then water-quenched is consistently the highest. A larger particle size uniformity index (n value) indicates a more uniform particle size. Thus, the grinding product particle size distribution of these samples is the narrowest, with the most uniform particle size.

- (3)

- BET and SEM results show that ore particles cooled in a reducing atmosphere to 200 °C and then water-quenched have the largest average pore size and the most cracks and pores, which enhances the minerals’ grindability.

Although this research has achieved satisfactory results, several potential challenges remain in the process of promoting industrialization. This has been conducted on a specific type of mineral at the laboratory scale, and the adaptability of other types of refractory iron ores requires further verification. Secondly, in industrial production, challenges such as fluctuations in ore feed quality, maintaining the continuous stability of cooling system parameters, and the necessity for coordination with existing production lines must be addressed. Furthermore, the design of large-scale cooling equipment for reducing atmospheres and water quenching systems, along with energy consumption control during continuous operation, necessitates in-depth exploration. Finally, it is necessary to further investigate the coupling effects of HMPT parameters and cooling methods on the processing efficiency of the ore. In conjunction with the grinding operation and separation processes, a comprehensive multi-factor prediction model should be developed. This will ultimately lead to the development of a more comprehensive and practical technical system for the efficient and sustainable utilization of refractory iron ore resources.

Author Contributions

S.Z.: Project administration, Resources, Conceptualization. P.T.: Modify, Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization. J.J.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resoures, Validation. D.L.: Project administration, Resources, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Major Project for Deep Earth Exploration and Mineral Resources grant number (2024ZD1004001) And The APC was funded by Jianping Jin.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allaire, S.E.; Parent, L.E. Size Guide Number and Rosin–Rammler Approaches to describe Particle Size Distribution of Granular Organic-based Fertilisers. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 86, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.J.; Courtney-Davies, L.; Flowers, R.; Zhang, Y.; Swanson-Hysell, N. Evolution of iron formation to ore during Ediacaran to early Paleozoic tectonic stability. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2025, 671, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulayani, M.M.; Raghupatruni, P.; Mamvura, T.; Danha, G. Coal-based reduction roasting and magnetic separation of low-grade Botswana iron ore for sustainable beneficiation. Miner. Eng. 2025, 233, 109594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xu, Y.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. Efficient degradation of organophosphorus pesticides and in situ phosphate recovery via NiFe-LDH activated peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, J. Mineralogy, fluid evolution, and ore-forming mechanism of the Early Cretaceous Yangshan iron skarn deposit in the Makeng-Yangshan region, SE China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2025, 293, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Gao, P.; Zhang, X.; Han, Y. Green reagent-driven resource recovery: Separation of hematite and iron-bearing silicate minerals from complex low-grade iron ore. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Lin, H.; Tang, X.; Luo, X. Ionic Speciation and Coordination Mechanisms of Vanadium, Iron, and Aluminum in the Oxalic Acid Leachate of Shale. Separations 2025, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovón-Canchumani, G.A.; Lima, F.M.S.; Araujo, M.G.; Elabras-Veiga, L.B. Environmental impacts for iron ore pellet production: A study of an open pit mine through life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 993, 179986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, C.; Song, H.; Lu, X.; Cheng, F. Synergistic gas–slag scheme to mitigate CO2 emissions from the steel industry. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, N.; Shao, Z.; Qin, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ni, Z.; Yang, L. Enhanced Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia at the Co-N Heteroatomic Interface in MOF-Derived Porous Carbon. Materials 2025, 18, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Yuan, S.; Han, R.; Gao, P.; Li, Y. An efficient and green method to separate iron from refractory iron ore by amino mineral phase transformation. Powder Technol. 2025, 464, 121277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, P.; Gao, P.; Li, Y.; Han, Y. Minerals phase transformation by hydrogen reduction technology: A new approach to recycle iron from refractory limonite for reducing carbon emissions. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Kang, X.; Li, P.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Qi, Z.; Sun, D. Thermal decomposition behavior of boron-bearing iron concentrate under nitrogen atmosphere: Kinetics, mineral phase transformation and microstructure evolution. Miner. Eng. 2025, 234, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Gao, P.; Han, Y. Hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation of bastnaesite: Detailed assessment of physicochemical properties and flotation behavior. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Gao, P.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Han, Y. Pilot-scale recovery of iron from refractory specularite ore using hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation technology: Process optimization, mineral characterization, and green production. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 491, 144836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Gao, P. Advanced strategies for the efficient utilization of refractory iron ores via magnetization roasting techniques: A comprehensive review. Miner. Eng. 2025, 225, 109236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Ying, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, M.; An, W. Motion and Appearance Decoupling Representation for Event Cameras. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 5964–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, H.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, W. A zero-carbon emission approach for the reduction of refractory iron ores: Mineral phase, magnetic property and surface transformation in hydrogen system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, S.; Gao, P.; Han, Y. Unlocking iron from oolitic hematite: Clean mineral phase transformation for primary iron concentrate production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Gao, P.; Yuan, S.; Han, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, W. Green approach for separating iron and rare earths from complex polymetallic solid residues via hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation: A pilot-scale study. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 350, 128006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Gao, P.; Tang, Z.; Wang, X.; He, J. Study on the mechanism of hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation to enhance the grinding characteristics of Bayan Obo polymetallic ore. Miner. Eng. 2025, 227, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Gao, P. Green iron recovery through hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation using ultrafast air-cooling for heat recycling: A pilot-scale investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yin, W. Study on the intergranular fracture of the minerals in iron ores from similar iron deposits. Miner. Eng. 2025, 224, 109209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Zhang, J.; Gao, P.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y.; Han, Y. Strategy to kill two birds with one stone: Contribution of hydrogen-based mineral phase transformation on enhancing the grinding and flotation characteristics of bastnaesite and fluorite. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.A.; Potgieter, J.H.; Nkhoesa, D.; Dyk, L.D. Vanadium, Titanium, and Iron Extraction from Titanomagnetite Ore by Salt Roasting and 21st-Century Solvents. Separations 2025, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fan, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, S. Application of the Rosin-Rammler function to describe quartz sandstone particle size distribution produced by high-pressure gas rapid unloading at different infiltration pressure. Powder Technol. 2022, 412, 117982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.