Abstract

Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle) C. Jeffrey is widely recognized for its anti-inflammatory properties, as well as its roles in lung purification, phlegm elimination, intestinal function regulation, and anti-tumor activity. Its pharmacological activity is attributed to a diversity of functional components. However, due to the extensive application of sweet glycosides in food additives, there have been few studies on non-sweet glycosides, particularly those with high polarity. This paper investigates the chemical constituents in the non-sweet glycosides fraction of S. grosvenorii juice. First, an MCI GEL CHP20P chromatographic column was utilized to enrich the non-sweet glycosides fraction. Furthermore, two-step medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) was performed for the efficient preparative separation of high-polarity non-sweet glycosides with similar structures, using C18 and silica gel as stationary phases, respectively. Seven non-sweet glycoside compounds were identified through NMR and mass spectrometry analyses, including three new compounds (4-hydroxyphenylethanol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 4-hydroxyphenylethanol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside and n-butanol 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside), as well as four known ones (α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-D-glucose, α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-fructofuranoside, methoxy hydroquinone diglucoside, and β-D-glucopyranoside). The results demonstrate that mixed-mode MPLC using different stationary phases is an efficient approach for separating non-sweet glycosides from S. grosvenorii.

1. Introduction

Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle) C. Jeffrey, a perennial vine belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family and predominantly distributed in southern China [1], has been widely applied in traditional medicine for its efficacy in addressing various health concerns. These include immune regulation, hypoglycemic effects, antioxidant properties, liver protection, and anti-tumor activity [2]. A pivotal challenge in herbal medicine research lies in clarifying the pharmacodynamic material basis. The pharmacological activity of S. grosvenorii is attributed to a diversity of functional components. Existing studies have confirmed that S. grosvenorii contains not only sweet glycosides, renowned for their sweet characteristics, but also numerous other potential bioactive substances [3,4]. However, due to the extensive application of sweet glycosides in food additives, current research demonstrates a notable selectivity bias, overlooking other functional constituents, particularly those with high polarity. It is noteworthy that manufacturers of sweet glycosides have preliminarily explored the potential commercial value of the non-sweet glycoside juice [5]. This juice, containing high-polarity components, serves as a by-product in the sweet glycosides production process [6]. In-depth exploration and clarification of the material basis of the juice are critical for promoting the further development and application of S. grosvenorii.

Traditional column chromatography persists as a prevalently utilized laboratory method for the separation and purification of natural products, primarily due to its operational simplicity and cost-effectiveness [7,8,9,10]. However, its extensive employment in laboratories is accompanied by notable drawbacks, including suboptimal separation efficiency, inconsistent reproducibility, and the lack of real-time monitoring functionality. These challenges complicate the purification of target compounds, thereby necessitating the exploration of alternative methodologies. Medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) has emerged as an efficient technique for compound isolation, featuring notable advantages such as cost-effectiveness, robust stationary phase stability, excellent separation reproducibility, online real-time monitoring, and automated operation [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Nevertheless, achieving high-purity target compounds often requires multi-step purification procedures using diverse stationary phases. Thus, the selection of optimal separation materials according to the physicochemical properties of target analytes is crucial. Currently, silica gel, polyamide resin, and MCI GEL CHP20P are widely employed as adsorbents in MPLC [18,19,20].

In this study, two-step MPLC approach was developed for purifying compounds from the non-sweet glycoside juice of S. grosvenorii, using C18 and silica gel as stationary phases. The purification process was systematically divided into two key stages: in the first step, MCI GEL CHP20P was employed to enrich the targeted fraction, enabling the selective isolation of target components from the complex mixture by leveraging its adsorption properties; in the second stage, the preliminarily enriched components were further purified via MPLC with C18 and silica gel columns, a combination that ensured high separation efficiency and maximized the purity of the final products. The method demonstrated robust effectiveness and reliability, highlighting its potential for scale-up in future applications to purify target compounds from other homologous natural products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Solvents employed for plant extraction, separation, and other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from Kelong (Chengdu, China). Chromatographic grade methanol and Deuterated methanol (MeOH) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Deuterated water (D2O) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The non-sweet glycoside juice was obtained from Monk Fruit Crop. (Guilin, China). This is a concentrated solution obtained from a macroporous resin column after loading the aqueous extract of S. grosvenorii. It was not absorbed by macroporous resin and does not contain sweet glycosides.

2.2. Instruments

The MPLC system (Yamazen, Osaka, Japan) was equipped with a pump (Model 580 s), a fraction collector (FR-360), and a UV absorbance detector (prepUV-20VH). The HPLC analysis was performed on an Agilent 1260 system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a 1260 Infinity III diode array detector (DAD), a 1260 Infinity III universal pump, a 1260 Infinity III sample vial injector, a 1260 Infinity III high-capacity column oven, a ZORBAX SB-C18 columnan (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), and an evaporative light scattering detector (Unimicro, Shanghai, China; ELSD), a Shimadzu GIS-C18 column (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan; 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). HPLC-DAD-ESI-IT-TOF-MSn analyses were conducted with a Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), which included a column oven, a degasser, an autosampler, two pumps, a PDA detector, an ESI ion source, and an IT-TOF mass spectrometer. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data were recorded using a Bruker Avance III HD-500 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a broadband observation probe. The rotary evaporator was conducted with EVELAN-1300 (Evela, Shanghai, China), and the lyophilizer was conducted with FDU-2110 (Evela, Tokyo, Japan). TLC was conducted at room temperature using ALUGRAM-precoated silica gel (0.20 mm in thickness) G/UV254 aluminum plates (20 cm × 20 cm; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Before sample spotting, these plates were cut to a suitable width. A SPARK microplate reader (Tecan, Zurich, Switzerland) was used to record the absorbance.

2.3. Preparation of the Crude Juice

The non-sweet glycoside juice underwent systematic purification via multi-stage chromatography. The process commenced with an initial treatment: 1 kg of non-sweet glycoside juice was mixed with 2 kg of deionized water to form a 3 kg diluted solution, which was then loaded onto the pre-prepared MCI GEL CHP20P chromatographic column (60 mm × 360 mm, 0.45 L of MCI GEL CHP20P) and eluted using a MeOH/H2O mobile phase. Gradient elution was performed using water, 5% MeOH, 10% MeOH, and 20% MeOH sequentially. The resulting crude sample fractions were concentrated via rotary evaporation followed by freeze-drying, yielding three fractions: the 5% MeOH-eluted (RE5, 7.0 g), the 10% MeOH-eluted (RE10, 3.0 g), and the 20% MeOH-eluted (RE20, 3.2 g). Combined HPLC and LC-MS spectral analyses indicated that RE5 contained peaks exhibiting high polarity and glycoside characteristics. To gain deeper insight into its composition, RE5 was retained for further purification.

2.4. Enrichment of the Target Minor Components

The RE5 (7.0 g) was dissolved in a MeOH/H2O mixture (5:95, v/v, 7.0 mL) to obtain a solution (7.0 g/mL), which was then pretreated with a C18 MPLC column using MeOH/H2O as the mobile phase for elution. Elution conditions were as follows: 0–130 min, 5–35% MeOH. Absorbance was measured at 203 nm with the mobile phase flow rate maintained at 20.0 mL/min. Four subfractions (RE5-A to RE5-D) were collected and concentrated according to the elution curve.

2.5. Separation of the Target Components

The fractions (RE5-A: 318 mg; RE5-B: 404 mg; RE5-C: 2.08 g; RE5-D: 181 mg) were each dissolved in 3 mL of MeOH, mixed with an equal weight of amorphous silica gel (200–300 mesh), and dried at 60 °C under vacuum to obtain a dry mixture. This was then loaded onto a pre-prepared silica gel MPLC column (20.0 g, 200–300 mesh) and eluted with a mixture of Dichloromethane (DCM) and MeOH (7:3, v/v) at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min, with UV monitoring at 203 nm. All processes were carried out at ambient temperature (25–28 °C). Following the above process, the target compounds were obtained from each fraction: RE5-A yielded compound 1 (10.6 mg) and compound 2 (15.7 mg), RE5-B yielded compound 3 (4.2 mg), RE5-C yielded compounds 4 (88 mg) and 5 (118 mg), and RE5-D yielded compounds 6 (40 mg) and 7 (21 mg).

2.6. Analysis and Identification of Fractions and Purified Compounds

The fractions and the purified compounds were subjected to TLC and HPLC analysis. TLC was performed on silica gel G/UV254 aluminum plates at ambient temperature, with samples manually spotted onto Alugram silica gel plates. The developing solvent system consisted of the organic phase of chloroform/methanol/water (6.5:3.5:0.75, v/v/v). After development, TLC plates were visualized under UV light at 254 nm, followed by spraying with a universal sulfuric acid/ethanol (1:9, v/v) derivatization reagent. Plates were air-dried and heated on a CAMAG TLC Plate Heater III (Camag, Winterthur, Switzerland) for approximately 5 min. HPLC analysis was conducted on a Shimadzu GIS-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) using a MeOH-H2O binary solvent system. The MeOH proportion increased gradually from 10% to 54% over 30 min. The chromatographic column was equilibrated with 10% MeOH for 20 min, and all experiments were conducted at a constant flow rate (0.8 mL/min). The elution profile was monitored using a DAD at 203 nm and an ELSD (drift tube temperature: 75 °C; air flow rate: 1.10 L/min). The structural characterization of compounds 1–7 was achieved through a comprehensive analysis of 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and LC-MS-IT-TOF, with comparison to literature values for final confirmation.

2.7. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization–Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Non-Sweet Glycoside Analysis

Then chemical analysis of the non-sweet glycoside juice was performed using LCMS-IT-TOF. Full-scan mass data were acquired in negative ion mode, with an m/z range of 50 to 2000. The ion source temperature was maintained at 550 °C, and the ion spray voltages were set to 5.5 kV and 4.5 kV. Characterization was achieved by analyzing ion peaks and their fragmentation products compared with standard information and published data.

2.8. Determination of Sugar Configuration in Novel Compounds

A 1.5 mg aliquot of the compound was accurately weighed and hydrolyzed with 3 mL of 2 mol/L trifluoroacetic acid at 110 °C for 5 h. Following hydrolysis, the reaction mixture was neutralized by adding an equal volume of MeOH, and residual acid was then removed via vacuum distillation. The hydrolysate was reconstituted in 1.5 mL of ultrapure water for monosaccharide composition analysis using 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP) pre-column derivatization.

HPLC analysis was performed under the following conditions: a TC-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) with an acetonitrile–phosphate buffer system (pH 7.1, 17:83, v/v) as the mobile phase. The chromatographic parameters were as follows: column temperature maintained at 30 °C, mobile phase flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 254 nm, and injection volume of 50 μL.

3. Results

3.1. Primary Enrichment Using MCI GEL CHP20P Chromatography

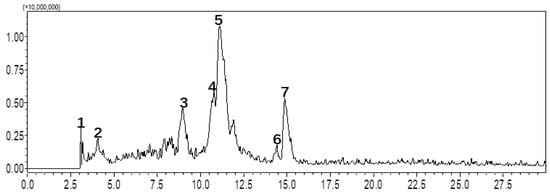

Considering the favorable aqueous solubility of the non-sweet glycoside-containing juice, initial fractionation was performed using MCI GEL CHP20P column chromatography (CC). As demonstrated in previous studies, MCI GEL CHP20P exhibits outstanding chemical stability, which ensures reproducible purification results [21,22,23]. In this study, the MCI gel CHP-20P CC was sequentially eluted with water, 5% MeOH, 10% MeOH, and 20% MeOH. HPLC analysis revealed that the 5% MeOH-eluted fraction (RE5) contained peaks with retention times ranging from 2.5 to 16 min, indicating that these components possess high polarity. Furthermore, the LC-MS profile of RE5 exhibited seven main peaks. Detailed analysis of the multistage mass spectra of these compounds—characterized by the loss of sugar moieties—confirmed their glycosidic nature (Table S1). The experimental results are shown in Figure 1. To gain a deeper understanding of the constituents of RE5, a chemical investigation was subsequently conducted.

Figure 1.

LC-MS/MS analysis of S. grosvenorii extract on the Shimadzu GIS-C18 analytical column.

3.2. The First-Dimensional MPLC Separation for Crude Fraction

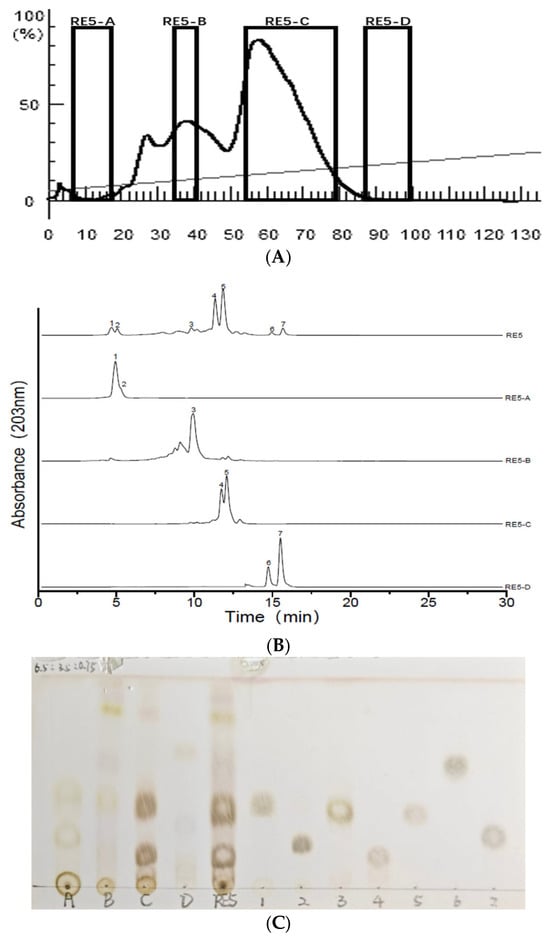

C18 was selected to couple with MPLC for first-dimensional separation. A solvent gradient elution with MeOH/H2O was used, and the flow rate was 20.0 mL/min. The collector gathered 20.0 mL of eluate into each tube, yielding 150 total fractions throughout the process. Subsequently, the MPLC fractions were merged based on TLC analysis results, yielding four distinct fraction components. The results are presented in Figure 2. The results demonstrate that the target analyte exhibited continuous elution behavior throughout the separation process, indicating the presence of a significant number of different compounds in the sample. Compounds 1 & 2, 4 & 5, and 6 & 7 were co-eluted in fractions RE5-A (318.1 mg), RE5-C (2.1 g), and RE5-D (181.3 mg), respectively. RE5-B (404.2 mg) consists of compound 3 and several unidentified minor compounds. RE5-A and RE5-D show negligible UV absorption across the range of 190–400 nm, whereas RE5-B and RE5-C exhibit distinct UV absorption maxima at 203 nm. Interestingly, while compounds 1 & 2, 4 & 5, and 6 & 7 showed very close retention times in C18 HPLC analysis, silica gel-based TLC analysis revealed significantly different retention factors (Rf) within each pair. This observation reveals a significant difference in separation efficiency between C18 and silica gel observation, offering valuable insights for the selection of experimental approaches in subsequent studies.

Figure 2.

(A): C18 medium-pressure chromatogram; (B): ELSD chromatograms of the crude fraction RE5 and subfractions RE5-(A–D); (C): TLC chromatogram of the crude fraction RE5, subfractions RE5-(A–D), and compounds (1–7). TLC method solvent-system selection: CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (6.5:3.5:0.75, v/v/v).

3.3. The Second-Dimensional MPLC Separation of RE5-A to RE5-D

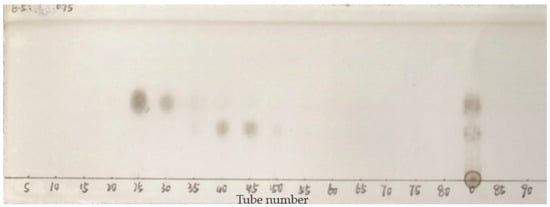

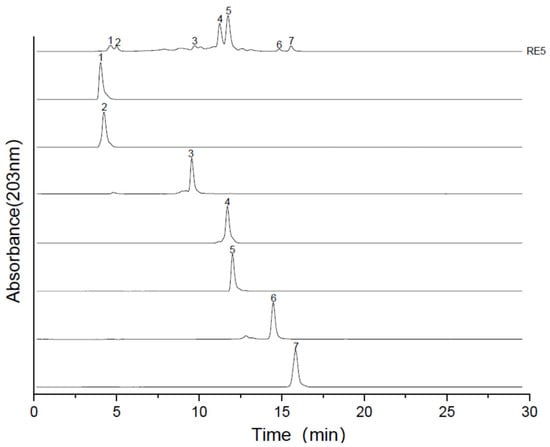

To achieve highly purified compounds, multiple MPLC (multi-column chromatography) steps with different stationary phases are often required. Notably, the most suitable material selection for later purification stages is contingent on the properties of compounds in the target fraction. Given that the paired compounds in fractions RE5-A, RE5-C, and RE5-D had significantly different Rf values in silica gel-based TLC, silica gel MPLC was used for subsequent separation. Furthermore, due to its lower toxicity and high availability, DCM was used to replace chloroform. A DCM/MeOH (7:3, v/v) solvent mixture was chosen as the mobile phase, and isocratic elution was performed for all samples. As illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the compounds in RE5-A were completely separated via the second-dimensional MPLC. Additionally, the same approach facilitated the isolation of other compounds, including three new glycosides from RE5-B to RE5-D with high purity. This fully demonstrates that silica gel and C18 possess distinctly different separation capabilities. The multi-dimensional chromatographic separation method, which harnesses the complementarity of the two distinct separation mechanisms, not only exemplifies the combined advantages of both chromatographic modes in the separation and purification of natural products but also substantially enhances the separation efficiency and purity of complex samples.

Figure 3.

TLC profiles of the purified compounds obtained by MPLC for RE5-A. TLC solvent system: CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (6.5:3.5:0.75, v/v/v).

Figure 4.

ELSD chromatogram of RE5 samples and purified compounds.

3.4. Identification of the Isolated Compounds

3.4.1. Structure Elucidation of the Novel Compounds (4, 5 and 7)

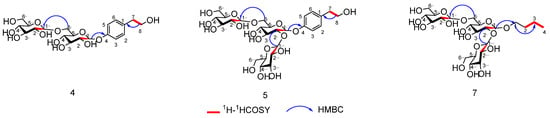

Compound 4 was obtained as a white powder. The HR-ESI-MS (Figure S1) detected an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z = 485.1641 (calcd. for C20H30O12Na, 485.1633, ∆ +0.8 mmu), which indicates six degrees of unsaturation. UV absorption spectroscopy (Figure S2) (MeOH) showed λmax values at 200, 219, and 271 nm [24]. The 1H NMR (Figure S3) spectrum characteristic signals of a para-disubstituted aromatic ring at δ 7.16 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz) and δ 7.05 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), two sets of methylene protons at δ 3.70 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz) and δ 2.72 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz) along with two anomeric protons at δ 5.02 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz) and δ 4.36 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz). Combination 13C NMR (Figure S4) and HSQC (Figure S5), 20 carbon signals were identified. These signals correspond to four methylene and fourteen methine groups, and two non-hydrogenated carbons (Table 1), of which eight were assignable to the aglycone moiety, and the remaining belonged to the sugar part. Through acid hydrolysis and HPLC analysis, the glycosyl moiety was identified as D-glucose, its structure confirmed by comparison to a D-glucose standard. The appearance of the methylene signal (C-8) at δC 62.6 implies that this position has no substitutions, which confirms the sugar moiety is located at the C-4 position. The aforementioned NMR data suggest that the structure of 4 shares a phenylethanoid skeleton similar to that of the known compound strigoside [25]. The only difference lies in that there is a rhamnosyl group in strigoside and a glucopyranosyl group in 4, which was further confirmed by the HMBC (Figure S6) correlations between H-1′ (δH 5.02) of glucosyl-A and C-4 (δC 154.9)/C′-3 (δC 75.8)/C′-5 (δC 75.5) and H-1″ (δH 4.36) of glucosyl-B and C′-6 (δC 68.2)/C″-3 (δC 75.6)/C″-5 (δC 75.4) (Figure 5). The configuration of glycosidic linkage of the glucopyranoside moieties in 4 was determined to be β based on their J values [δH 5.02 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz) and δH4.36 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz)] of their anomeric protons. Therefore, the structure of 4 was elucidated as a phenylethanoid, named as 4-hydroxyphenylethanol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 1.

1H- and 13C-NMR spectrum data of compounds 4 and 5.

Figure 5.

Key 1H 1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY; red bold lines) and hetero nuclear multiple bond coherence (HMBC; blue arrows) correlations of compounds 4, 5, and 7.

Compound 5 was obtained as a white powder. The HR-ESI-MS (Figure S8) detected an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z = 647.2157 (calcd. for C26H40O17Na, 647.2163, ∆ −0.6 mmu), which indicates seven degrees of unsaturation. UV absorption spectroscopy (Figure S9) (MeOH) showed λmax values at 200, 219, and 271 nm [24]. The 13C (Figure S10) and 1H NMR (Figure S11) data for compound 5 (Table 1) were comparable to those of compound 4, with the only difference being in their sugar moieties. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound 5 signals corresponding to three β-glucopyranosyl moieties [δH 5.25 (1H, d, J = 7.69 Hz), 4.73 (1H, d, J = 7.69 Hz), and 4.36 (1H, d, J = 7.69 Hz)]. In the HMBC (Figure S12) spectrum, the cross-peaks between H-1′ (δH 5.25) of glucosyl-A and C-4 (δC 154.5) of the aglycone, and H-1″ (δH 4.36) of glucosyl-B and C-6′ (δC 68.2) of glucosyl-A, H-1‴ (δH 4.73) of glucosyl-C and C-2′ (δC 81.2) of glucosyl-A suggested sugar linkage. By integrating the above data with the analysis results of HSQC (Figure S13), HMBC, and 1H-1H COSY (Figure S14) spectra, the chemical structure of compound 5 was elucidated as a phenylethanoid shown in Figure 5 and named as 4-hydroxyphenylethanol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Compound 7 was obtained as a yellow oily liquid. The HR-ESI-MS (Figure S15) detected an [M − H]− ion at m/z = 559.2245 (calcd. for C22H39O16, 559.2316, Δ −7.1 mmu), which indicates three degrees of unsaturation. UV absorption spectroscopy (Figure S16) (MeOH) showed λmax values at 209, 257, and 291 nm [24]. The 13C (Figure S17) and 1H NMR (Figure S18) data for compound 7 (Table 2) were comparable to those of compound 5, with the only difference being in their substituent regions. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound 7 showed four sets of methylene protons with δ values of 3.88, 3.64 (2 m), 1.55 (2H, q, J = 7.4 Hz,), 1.32 (2H, q, J = 7.4 Hz), and 0.86 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), respectively, assigned to H-1, H-2, H-3, and H-4 of the n-butanol unit, which was further confirmed by the HMBC (Figure S19) correlations between H-2 (δH 1.55) and C-4 (δC 13.2) (Figure 5). The HMBC correlation between H-1′ (δH 4.52) of the glucose moiety-A and C-1 (δC 70.7)/C′-2 (δC 31.1) and C′-3 (δC 18.6) confirms that the glucose moiety is located at C-1. Based on the above data, combined with the analysis of HSQC (Figure S20), HMBC, and 1H-1HCOSY (Figure S21) spectra, as shown in Figure 5, the chemical structure of compound 7 was elucidated and named n-butanol 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Table 2.

1H- and 13C-NMR spectrum data of compounds 7.

3.4.2. Identification of the Known Isolated Compounds

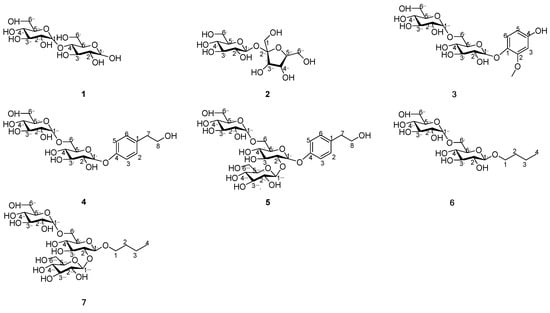

Four known compounds were identified as α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-D-glucose (1) [26], α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-fructofuranoside(2) [26], methoxy hydroquinone diglucoside (3) [27], and β-D-glucopyranoside (6) [28]. By directly comparing their NMR spectra with the published data in the literature, (NMR data are available in the Supporting). Compounds 1–7 are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–7.

4. Conclusions

This study developed an efficient MPLC method for separating and purifying high-polarity compounds from S. grosvenorii extracts. Through MCI GEL CHP20P chromatography to obtain four mixed fractions, followed by two-step purification via MPLC integrating C18 and silica gel columns, seven compounds were isolated, including three novel structures. These findings confirm that MPLC enables optimal selection of separation materials for complex samples, significantly improves process efficiency, and thus exhibits practical utility and potential as a powerful purification strategy for complex natural product matrices-particularly for high-polarity compounds from S. grosvenorii extracts. While the current results are promising, additional practical validation is necessary before extending this approach to others.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010026/s1, Figure S1: HR-ESI-MS Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S2: UV absorption spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S3: 1HNMR Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S4: 13CNMR Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S5: HSQC Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S6: HMBC Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S7: 1H-1H COSY Spectrum of compound 4* in D2O; Figure S8: HR-ESI-MS Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S9: UV absorption spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S10: 13CNMR Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S11: 1HNMR Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S12: HMBC Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S13: HSQC Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S14: 1H-1H COSY Spectrum of compound 5* in D2O; Figure S15: HR-ESI-MS Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S16: UV absorption spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S17: 13CNMR Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S18: 1HNMR Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S19: HMBC Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S20: HSQC Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S21. 1H-1H COSY Spectrum of compound 7* in D2O; Figure S22: Key HMBC and 1H-1H COSY correlations for compound 4*, 5*, 7*; Figure S23: HPLC of monosaccharide compositions of compounds 4*, 5*, 7*; Table S1: Compounds identified in RE5 by LC-MS/MS analysis.

Author Contributions

W.C. and X.T. conceived of and wrote the manuscript; X.D. collected the plant materials; X.Y. carried out data analysis; X.J. and Y.W. instructed on experiments; F.L. and H.J. designed the experiments, reviewed the writing, and supported funding for this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Guangxi Key R&D Project (GuikeAB25069040, GuikeAB25069363), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2023GXNSFDA026053), and the Guangxi Qi Huang Scholar Support Program (GXQH202401).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinghua Dai was employed by the company Guilin GFS Monk Fruit Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Duan, J.J.; Zhu, D.; Zheng, X.X.; Ju, Y.; Wang, F.Z.; Sun, Y.F.; Fan, B. Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle) C. Jeffrey: Research progress of its active components, pharmacological effects, and extraction methods. Foods 2023, 7, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Chen, X.F.; Gong, P.; Long, H.; Wang, J.T.; Yang, W.J.; Yao, W.B. Siraitia grosvenorii as a homologue of food and medicine: A review of biological activity, mechanisms of action, synthetic biology, and applications in future food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 13, 6850–6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chen, N.H.; Ren, K.; Jia, J.Y.; Wei, K.H.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Y.; Wang, J.H.; Li, M.H. The Fruits of Siraitia grosvenorii: A Review of a Chinese Food-Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, R.L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, L.M. Research progress of pharmacological effects of Siraitia grosvenorii extract. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 7, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.S.; Fan, X.Y.; Sun, Q.L.; Han, J.Y.; Hua, C.H.; Li, Y.; Niu, Y.W.; Emeka Okonkwo, C.; et al. Properties, extraction and purification technologies of Stevia rebaudiana steviol glycosides: A review. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Ma, Q.Y.; Li, J.H.; Du, G.C.; Liu, L.; Lv, X.Y. Progress and prospects of natural glycoside sweetener biosynthesis: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 43, 15926–15941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosavljević-Stevanović, N.; Andrić, F.; Manojlović, D.; Ristivojević, P. Green analytical strategy for distinguishing Cannabis sativa L. chemotypes via planar chromatography and partial least squares regression. JPC–J. Planar. Chromatogr. 2024, 6, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.T.; Cao, Y.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.W.; Kang, J.; Wang, H. Synthesis of functional ionic liquid modified silica and its excellent performance in selective separation of artemisinin/artemisinin. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 272, 118612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, R.; Lill, J.; Olbrich, M.; Schmidt, P.; Müller-Späth, T. Purification of a GalNAc-cluster-conjugated oligonucleotide by reversed-phase twin-column continuous chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1663, 462734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Li, C.Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.L.; Li, G.; Dang, J. Preparative isolation of antioxidative furanocoumarins from Dracocephalum heterophyllum and their potential action target. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 24, 4375–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawa, Y.; Du, Y.R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, C.B.; Zou, D.L.; Qi, D.S.; Ma, J.B.; Dang, J. Targeted isolation of 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl inhibitors from Saxifraga atrata using medium-and high-pressure liquid chromatography combined with online high performance liquid chromatography–1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1635, 461690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, M.X.; Pan, N.; Wu, J.N.; Chen, X.T.; Cai, S.L.; Fang, H.; Xiao, M.T.; Jiang, X.M.; Liu, Z.Y. Reversed-Phase Medium-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Purification of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters Using AQ-C18. Mar. Drugs 2024, 6, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Ma, J.B.; Dawa, Y.; Liu, C.; Ji, T.F.; Wang, Q.L. Preparative separation of 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl inhibitors originating from Saxifraga sinomontana employing medium-pressure liquid chromatography in combination with reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Rsc. Adv. 2021, 61, 38739–38749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.X.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Li, K.K.; Li, C.M. Rapid purification of alkylamides from Zanthoxylum bungeanum by medium-pressure liquid chromatography and the establishment of a numbness prediction model using an electronic tongue. Anal. Methods 2024, 8, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, V.; Varriale, F.; Melchiorre, C.; Varra, M.; Tartaglione, L.; Kulis, D.; Anderson, D.M.; Ricks, K.; Poli, M.; Dell’Aversano, C. Isolation of ovatoxin-a from Ostreopsis cf. ovata cultures. A key step for hazard characterization and risk management of ovatoxins. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1736, 465350. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.H.; Du, T.T.; Liu, X.Y.; Xu, H.T.; Chen, T.; Chou, G.X. Isolation and Identification of Monoterpenoids from Callicarpa Nudiflora. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 12, e20240147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, D.C.; Ki, D.W.; Won, Y.S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, I.K.; Yun, B.S. Three new nonenes from culture broth of marine-derived fungus Albifimbria verrucaria and their cytotoxic and anti-viral activities. J. Antibiot. 2024, 7, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Shen, C.; Li, H.M.; Zhao, J.Y.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.L. An effective method based on medium-pressure liquid chromatography and recycling high-speed counter-current chromatography for enrichment and separation of three minor components with similar polarity from Dracocephalum tanguticum. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 3, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, W.J.; Wang, Q.L.; Tao, Y.D.; Yu, R.T.; Pan, G.Q.; Dang, J. Preparative separation of isoquinoline alkaloids from Corydalis impatiens using middle chromatogram isolated gel column coupled with positively charged reversed-phase liquid chromatograph. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 13, 2521–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, C.; Li, G.; Ji, T.F. Preparative isolation of antioxidative gallic acid derivatives from Saxifraga tangutica using a class separation method based on medium-pressure liquid chromatography and reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 20, 3734–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Du, Y.R.; Wang, Q.; Dawa, Y.; Chen, C.B.; Wang, Q.L.; Ma, J.B.; Tao, Y.D. Preparative isolation of arylbutanoid-type phenol [(-)-rhododendrin] with peak tailing on conventional C18 column using middle chromatogram isolated gel column coupled with reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 16, 3233–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.Q.; Shen, J.W.; Ma, Y.H.; He, Y.F.; Bao, Y.; Li, R.R.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, Q.; Lin, P.C.; Dang, J. Preparative separation of isoquinoline alkaloids from Corydalis impatiens using a middle-pressure chromatogram isolated gel column coupled with two-dimensional liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 20, 3182–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, D.; Xi, X.J.; Huang, X.Y.; Quan, K.J.; Wei, J.T.; Wang, N.L.; Di, D.L. Isolation of high-purity peptide Val-Val-Tyr-Pro from Globin Peptide using MCI gel column combined with high-speed counter-current chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 24, 4559–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yang, X.R.; Yan, X.J.; Lu, F.L.; Liu, Z.B.; Li, D.P. Preparative isolation of diterpenoids from Salvia bowleyana Dunn roots by high-speed countercurrent chromatography combined with high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 9, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapoom, T.; Noiarsa, P.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kasai, R.; Otsuka, H. Phenylethanoid and iridoid glycosides from the Thai medicinal plant, Barleria strigosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 5, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Tester, R.F. Lactose. Maltose, and sucrose in health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 8, e1901082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, S.; Cole, R.B.; Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; French, A.D.; Johnson, G.P.; Laine, R.A. Incremented alkyl derivatives enhance collision induced glycosidic bond cleavage in mass spectrometry of disaccharides. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 1, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.H.; Qiu, F.; Zeng, J.L.; Gu, L.; Wang, B.J.; Lan, X.Z.; Chen, M. A Novel UDP-Glycosyltransferase of Rhodiola crenulata Converts Tyrosol to Specifically Produce Icariside D2. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7970590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.