Abstract

Polar compounds can be separated on polar stationary phases attached on the surface of silica hydride (Type C silica). Although aqueous normal phase (ANP) chromatography has been used to denote this mode of separation, there have been no detailed studies on the retention mechanisms. We have applied the quantitative assessment methodology to investigate the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the silica-hydride-based polar phases using a widely used hybrid silica-based amide phase for comparison. The study results indicate that the silica-hydride-based polar phases are not fundamentally different from the hybrid silica-based phase in terms of the adsorbed water layer and the retention mechanisms for polar compounds. Similar forces governing the retention in HILIC (i.e., partitioning, adsorption, and electrostatic interactions) are sufficient to describe the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the silica-hydride-based polar phases. However, some small differences in selectivity are observed between the silica-hydride-based and hybrid silica-based phases.

1. Introduction

Many compounds of biomedical and pharmaceutical importance such as small metabolites, nucleosides and nucleotides, glycans, peptides, and oligonucleotides are polar in nature and very difficult to separate in conventional reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) due to lack of retention. For example, oligonucleotides have emerged as an important treatment modality and present special challenges to chromatographic separation [1,2]. Ion-pairing agents (e.g., alkylamines) have to be added to the mobile phase to render oligonucleotides less polar; however, the presence of ion-pairing agents is less ideal for mass spectrometric detection [3]. Alternatively, hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) has been applied to oligonucleotide separation with significant success and has shown complementary strength to ion-pairing RPLC [4]. Most HILIC separations are performed on bonded stationary phases based on Type B silica or hybrid silica matrixes, such as amide, diol, polyacrylamide, and zwitterionic phases [5,6]. There are a significant number of silanol groups (Si-OH) present on the surface of Type B silica even after the surface is modified with the bonded phases.

Surface silanol groups on the surface of silica gel can be largely replaced with silica hydride groups (Si-H) through a silanization process, resulting in Type C silica [7]. The number of silanol groups is significantly reduced (<5% remaining) on the silica hydride surface, rendering unmodified Type C silica less hydrophilic than the conventional Type B silica [8]. The silica hydride groups on the Type C silica can be modified by hydrosilation to attach both lipophilic (e.g., C18, cholesterol, phenyl and undecanoic acid) and hydrophilic ligands (e.g., amide and diol) as stationary phases [8,9,10,11]. An interesting feature of the silica-hydride-based stationary phases is that these stationary phases can be used to separate various compounds in a mixed mode with a wide range of lipophilicity over the entire range of mobile phase composition from 100% aqueous to pure nonpolar organic solvents [12]. Polar compounds are separated on the silica-hydride-based polar phases using the mobile phase containing higher levels of organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) in a manner similar to hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC). However, aqueous normal phase (ANP) has been used to describe polar compound separation on the silica-hydride-based phases [13,14]. Elution order of polar compounds in the ANP mode is the same as that in HILIC with the retention positively correlated to polarity. However, the term ANP may imply that the retention of polar compounds on the silica-hydride-based phases resembles that in normal phase liquid chromatography (NPLC), which is governed by surface adsorption. In addition, electrostatic interactions have been found to be involved in the retention of charged compounds on both unmodified and modified silica-hydride-based phases due to accumulation of hydroxide ions (OH−) on the hydrophobic surface of low permittivity of the Type C silica [15,16,17,18]. However, other retention mechanisms (e.g., hydrophilic partitioning) in the ANP mode, especially on the bonded polar phases based on the Type C silica, have not been evaluated in detail.

Frontal analysis is a continuous injection chromatographic method to obtain thermodynamic isotherms, which are used to determine the characteristic constants of the adsorbent. The results of frontal analysis indicate that there is still excess water adsorbed on the unmodified silica hydride surface, but the adsorbed water layer is very thin with only less than half the equivalent monomolecular water layer [19]. The adsorbed water layer on the unmodified silica hydride surface is found to increase with temperature to more than half the equivalent monolayer at 80 and 100 °C [20]. The thin adsorbed water layer on the silica hydride surface is in sharp contrast to the adsorbed water layer on the unmodified surface of the Type B silica, which is approximately equivalent to 1.5 monomolecular water layers and 2–9.5 monomolecular water layers on the Type B silica with bonded polar phases [21]. However, there is no frontal analysis data available for the Type C silica with bonded polar phases in the literature. A molecular simulation study on the water layer adsorbed on a bonded diol-alkyl phase indicates that a significant diffuse water layer can be formed through hydrogen bonding of water molecules with the polar groups of the bonded phase, although the rigid layer adsorbed directly on the silica surface is not sufficient to build a significant diffuse layer [22]. Therefore, it is conceivable that a diffuse water layer may be formed on the Type C silica surface with polar bonded phases (e.g., amide and diol). A significant adsorbed water layer may enable the partitioning mechanism to further enhance retention of polar compounds on the silica-hydride-based stationary phases.

The primary objective of this study is to elucidate the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the bonded stationary phases based on the Type C silica. For this purpose, two Type C silica columns with polar bonded phases (Cogent Amide and Cogent Diol) were selected for this study; and a hybrid silica-based amide phase (XBridge Amide) was included for comparison. Previous studies investigating the retention mechanisms in HILIC were based on either the partitioning or adsorption model by evaluating the effect of acetonitrile levels in the mobile phase on the retention of polar compounds [23,24]. However, the experimental data does not fit either model in most cases [23]. A mixed-mode model can better fit the experimental data but cannot differentiate different forces involved in retention [25]. Most published studies on the silica-hydride-based phases focused on various applications. Only a few studies attempted to investigate the retention behavior and mechanisms of polar compounds [10,11]. Fentanyl and matrine were observed to exhibit mixed-mode behaviors on the silica-hydride-based diol phase, but hydromorphone and hydrocodone were more retained in the ANP mode [10]. The silica-hydride-based amide phase displayed mixed-mode characteristics with anisole showing reversed-phase behaviors and adenosine showing ANP behavior [11]. A better understanding of the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the stationary phases based on the Type C silica can not only improve our knowledge in the silica hydride material but also provide guidance on the application of the silica-hydride-based phases. This will also potentially broaden the application of the bonded phases based on the Type C silica, which may complement the existing polar phases based on the Type B silica. Unlike the conventional approach to study the retention mechanisms by evaluating the retention of polar compounds at various acetonitrile levels, a new quantitative methodology that was developed to assess the retention mechanisms in HILIC has been employed in this study. Based on the literature search, this is the first study using the quantitative methodology to investigate the retention mechanisms on the bonded phases based on the Type C silica.

2. Methodology

Qualitative studies have shown that hydrophilic partitioning, surface adsorption, and electrostatic interactions (when both analytes and stationary phases are charged) are involved in retaining polar compounds in HILIC [23,24]. Surface adsorption is dependent on polar interactions with the polar functional groups of the bonded phases including hydrogen bonding. Hydrophilic partitioning takes place between the organic-aqueous mobile phase and adsorbed water layer on the polar stationary phases. The adsorbed water layer is considered as the de facto stationary phase in hydrophilic partitioning, and the volume of the adsorbed water layer is the stationary phase volume (VS) [26]. The phase ratio (Φ) is defined as the ratio of the stationary phase volume (VS) over the mobile phase volume (VM). Using toluene as the void marker, the phase ratio (Φ) can be measured using the toluene elution time in pure acetonitrile (tACN) and a mobile phase (tM) containing specific levels of acetonitrile and ammonium acetate as in Equation (1) [27]:

Previous studies have demonstrated that the volume of the adsorbed water layer, hence, the phase ratio, varies with the concentration of certain salts (e.g., ammonium acetate and formate) in the mobile phase in HILIC [27]. This provides a means to vary the phase ratio without changing the columns.

We have developed a quantitative assessment methodology to evaluate the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the polar stationary phases in HILIC [28,29]. The quantitative methodology is based on the premise that the observed retention factor (kobs) of a non-ionized compound is linearly proportional to the phase ratio (Φ) as in Equation (2):

where K represents the partitioning coefficient and kads the retention attributed to surface adsorption. The partitioning coefficient is dependent on the acetonitrile level in the mobile phase but not on the salt concentration in the range typically used in HILIC, thus independent of the phase ratio. Surface adsorption is assumed to be independent of the salt concentration [28]. Therefore, the observed retention factor is linearly proportional to the phase ratio (Equation (2)). The linear relationship between the observed retention factors and phase ratio has been demonstrated in previous studies [30,31]. Partitioning coefficients (K) are obtained from the slope and the retention contribution by surface adsorption (kads) from the intercept through linear regression of the observed retention factor (kobs) vs. phase ratio (Φ) plot. The retention contributed by hydrophilic partitioning can be calculated by multiplying the partitioning coefficient and phase ratio (KΦ) at specific acetonitrile levels and salt concentrations.

For ionized compounds, the retention is affected by electrostatic interactions at lower salt concentrations, resulting in deviation from the linear relationship (Equation (2)) at low salt concentrations. However, the electrostatic effect is attenuated by increasing salt concentration and becomes negligible when the salt concentration is sufficiently high to shield the charge interactions [29]. If the salt concentration further increases within the solubility limit, the observed retention factor linearly increases with the phase ratio again as in Equation (2). Therefore, a linear segment of the kobs vs. Φ plot would be obtained at high salt concentrations. Similar to the non-ionized compounds, the partitioning coefficient (K) and the retention contributed by surface adsorption (kads) of the ionized compounds can be obtained through linear regression of the linear segment of the kobs vs. Φ plot. Finally, the effect of electrostatic interactions (kelec) can be calculated using Equation (3) [29]:

Here, a positive kelec value indicates electrostatic attraction and a negative value electrostatic repulsion. The quantitative assessment methodology has not been applied to the study of retention mechanisms on the bonded polar phases based on the Type C silica. However, previous frontal analysis indicates that there is a significant adsorbed water layer on the bonded polar phases based on the Type C silica. This justifies the application of the quantitative assessment methodology in this study.

3. Materials and Methods

Type-C-silica-based Cogent Diol and Amide columns (150 × 3.0 mm ID) were provided by Microsolv Technology Corp. (Wilmington, NC, USA). An XBridge Amide column (250 × 4.6 mm ID) was acquired from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). Specific information on particle size, pore size, surface area and carbon loading of each stationary phase was obtained from published information of the supplier (Table 1). HPLC grade purified water and acetonitrile were purchased from Fischer Scientific (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Ammonium acetate was supplied by TCI (Portland, OR, USA). A stock salt solution was based at 400 mM by dissolving appropriate amounts of ammonium acetate in purified water. The pH of the stock ammonium acetate solution was around 6.8–6.9 and was not further adjusted. Test compounds including cytosine, dopamine, 2-deoxyuridine (2dU), uridine, adenosine, 1-methylxanthine (1-MX), 3-methylxanthine (3-MX), 1,7-dimethylxanthine (1,7-DMX), 3,7-dimethylxanthine (3,7-DMX) or theobromine, α-hydroxyhippuric acid, and hippuric acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Caffeine, vidarabine, 7-methylxanthine (7-MX), and 1,3-dimethylxanthine (1,3-DMX) or theophylline were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Bridgewater, NJ). The stock solution of each compound was prepared at about 1 mg/mL by dissolving the appropriate amount of the test compound in a mixture of acetonitrile and water (50/50, v/v). The test solution for each group was prepared by mixing the stock solutions and was diluted with 1:1 acetonitrile and water if needed. About 10 µL of 100 mg/mL toluene solution in acetonitrile was also added to each test solution as the void marker. Each sample was injected at least three times to obtain a reproducible retention time of the test compounds.

Table 1.

Specification information of the stationary phases used in this study *.

All the experiments were performed on an Agilent 1260 HPLC system (Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an online vacuum degasser, a quaternary gradient pump, an autosampler, a thermostated column compartment, and a variable wavelength UV detector. Chromatographic data was collected and processed by ChemStation for LC and LC/MS (Rev. C.01.06). The column temperature was set at 25 °C, and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The injection volume was 0.5–2 μL, and UV detection was performed at 254 and 262 nm. The mobile phase was prepared by online mixing of acetonitrile, water, and 400 mM ammonium acetate stock solution. Acetonitrile was kept at 85% or 80%, and ammonium acetate solution was varied from 1% to 10% to obtain the salt concentration of 4 mM to 40 mM in the mobile phase. The volume of water was adjusted accordingly to maintain the aqueous volume at 15% or 20%. The column was equilibrated for at least 20 min whenever the mobile phase composition was changed. Toluene void time was checked to be consistent before testing any samples.

Statistical tests (t-test and ANOVA) were performed using Microsoft Excel.

4. Results

Formation of the adsorbed water layer on the silica-hydride surface with polar bonded phases was first investigated for two reasons. First, there is no published data on the adsorbed water layer on the polar stationary phases based on the Type C silica. Second, the adsorbed water layer is critical to the partitioning mechanism. The retention mechanisms for both non-ionized and ionized compounds were then evaluated since the retention behavior of the ionized compounds could reveal the charge properties of these stationary phases. Finally, a hybrid silica-based amide phase (XBridge Amide) was used for comparative purposes in this study since both have similar polar functional groups, but the surface properties are different.

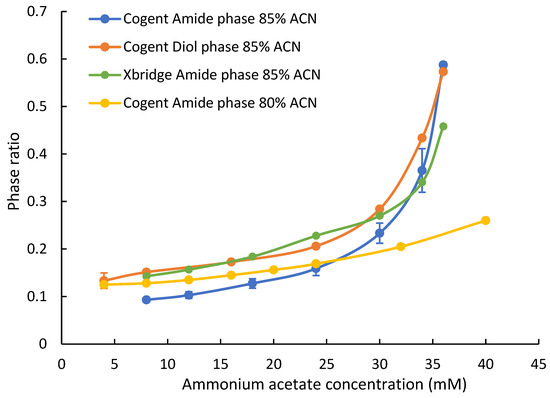

4.1. Adsorbed Water Layer

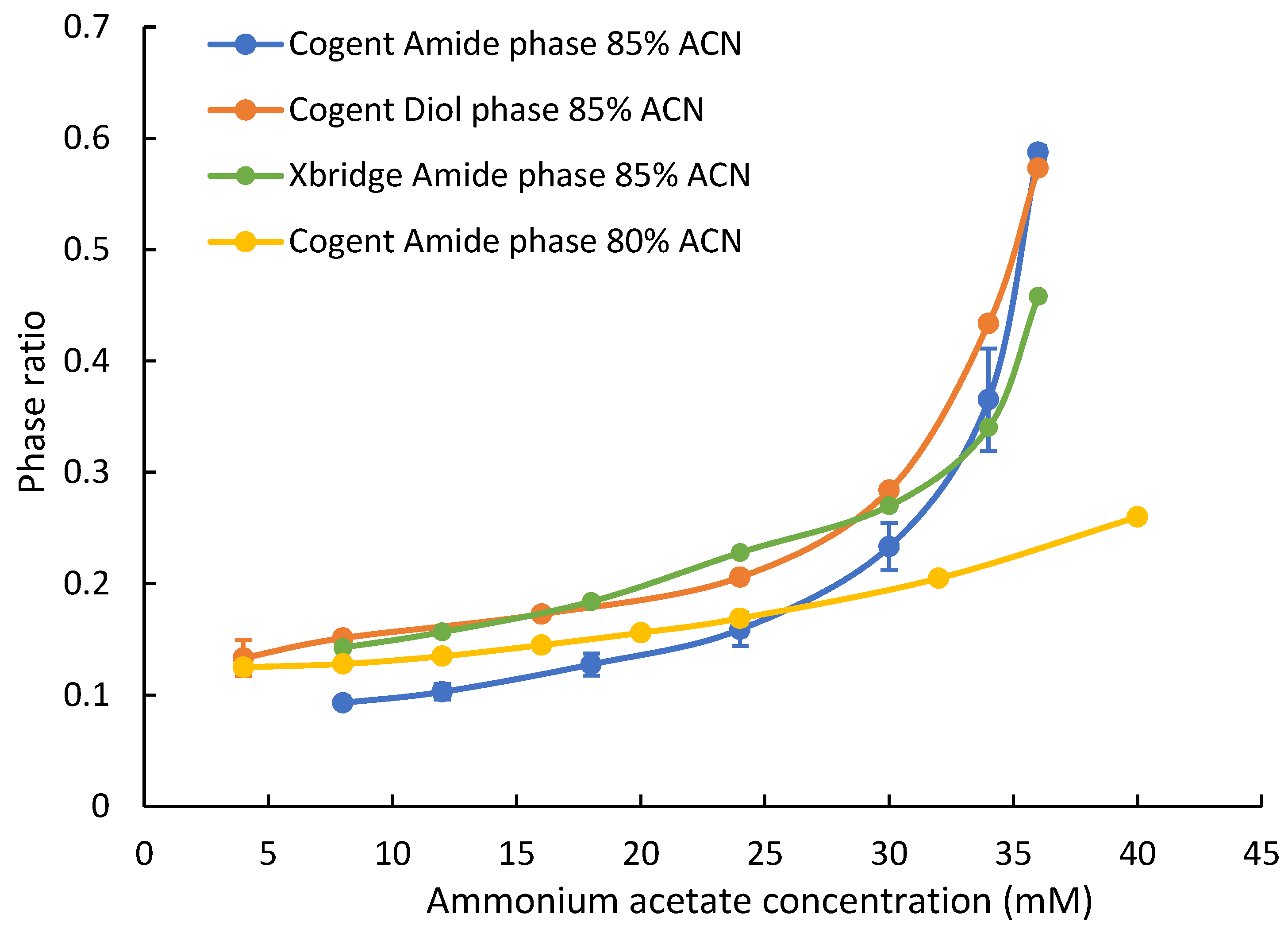

The phase ratio is defined as the volume of the adsorbed water layer over the volume of the mobile phase and, thus, can be used as the indicator of the adsorbed water layer [26,27]. In this study, the phase ratio of two polar stationary phases based on the Type C silica (Cogent Amide and Diol phases) was measured at two acetonitrile levels (80% and 85%) and various ammonium acetate concentrations (4–40 mM). The phase ratio of the hybrid silica-based amide phase (XBridge Amide) was also measured. Figure 1 shows the phase ratio of each phase at various ammonium acetate concentrations at 85% acetonitrile. The phase ratio of the Cogent Amide and Diol phases reveals that there is a significant adsorbed water layer on the surface of the silica hydride-based bonded phases. The phase ratio measurement was performed in triplicates (n = 3), and the relative standard deviation (RSD) was typically in the range 0.2–12.5% RSD. Higher RSD% may be related to the variation of ammonium acetate concentration in the stock solution and the column equilibration time. Although published results based on the frontal analysis indicate that the excess of adsorbed water on the unmodified silica-hydride surface is very low (less than half of equivalent monolayer), the phase ratio data of the Cogent Amide and Diol columns shows that there is a significant adsorbed water layer, which is a major difference between the modified and unmodified Type C silica. An earlier molecular dynamic simulation study suggests that the rigid layer formed on the modified silica surface may not be sufficient to form a diffuse layer; however, the bonded polar ligands can help build a significant diffuse layer through the hydrogen bonding network between the polar groups and water molecules [22]. Therefore, it is plausible that the polar ligands (amide and diol groups) bonded to the silica hydride surface are able to build a significant adsorbed water layer. In addition, Figure 1 shows that the adsorbed water layer on the Cogent Diol phase is similar to that on the XBridge Amide phase and is thicker than that on the Cogent Amide phase at ammonium acetate concentration below 30 mM. The phase ratio of all the stationary phases increases with the concentration of ammonium acetate in the mobile phase, which is consistent with previous studies [27]. It is interesting to note that the phase ratio of the Cogent Amide and Diol phases is even higher than that of the XBridge Amide phase at ammonium acetate concentration above 30 mM. In addition, the phase ratio of the Cogent Amide phase is moderately higher at 80% acetonitrile than that at 85% acetonitrile up to 24 mM ammonium acetate. When the ammonium acetate concentration further increases, the phase ratio at 85% acetonitrile exceeds that at 80% acetonitrile. This behavior has been observed on the Type-B-based polar stationary phases [27].

Figure 1.

The phase ratio of the Cogent Amide, Cogent Diol, and XBridge Amide phases at various ammonium acetate concentrations in the mobile phase containing 80% and 85% acetonitrile. Column temperature is 25 °C. Error bars show the standard error based on three replicates.

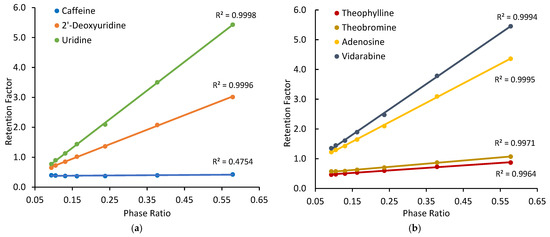

4.2. Retention Mechanisms of Non-Ionized Compounds

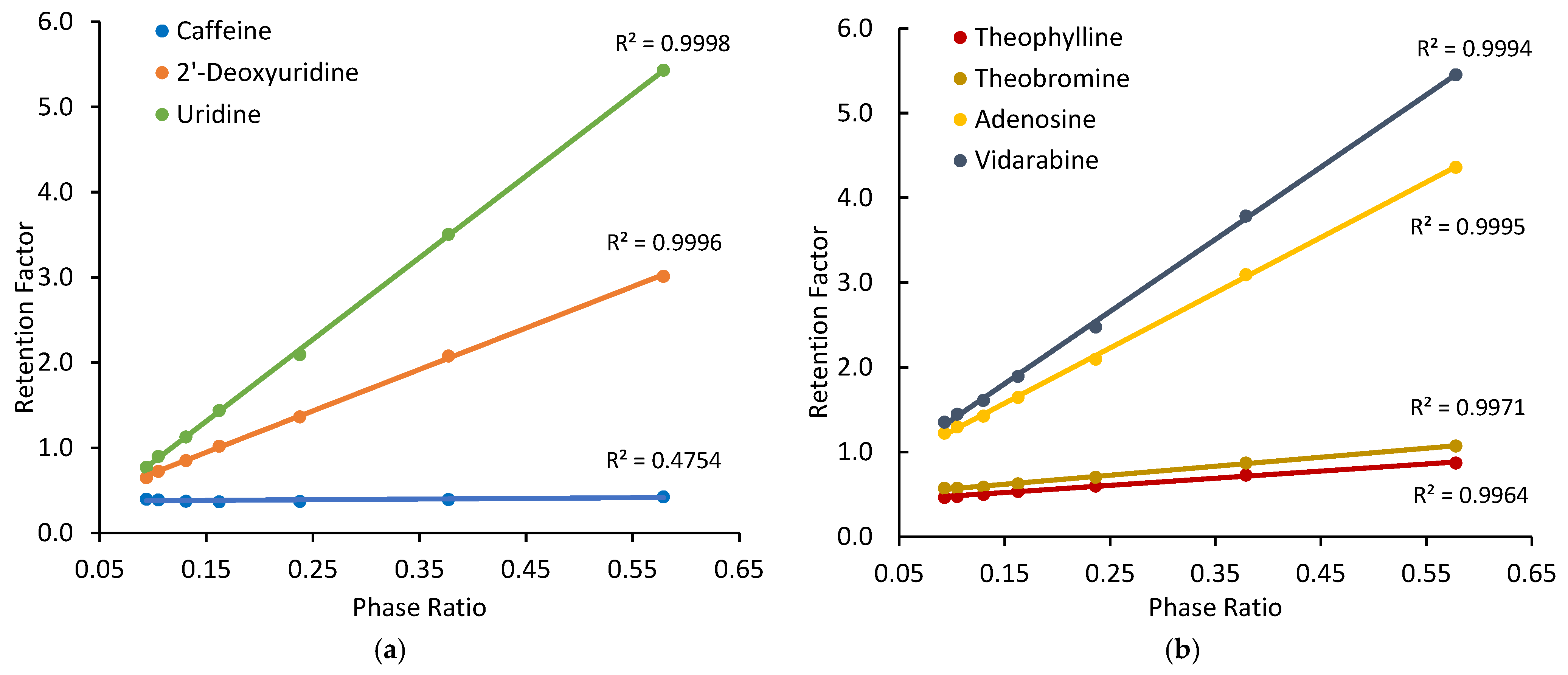

For non-ionized compounds, the presence of a significant adsorbed water layer makes hydrophilic partitioning possible on the silica hydride-based phases. At the absence of electrostatic interactions, surface adsorption through direct polar interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) is another plausible retention mechanism. Figure 2 shows the observed retention factors of selected non-ionized test compounds on the Cogent Amide phase at different ammonium acetate concentrations in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile. The observed retention factors of all the test compounds (except caffeine) increase linearly with the phase ratio as demonstrated by all coefficients of determination (R2) close to 1.0, except for caffeine. Since the phase ratio is only related to the volume of the adsorbed water layer, significant correlation between the observed retention factor and phase ratio supports the involvement of hydrophilic partitioning in retention process. Similar behaviors of the same test compounds have been reported on the Type-B-based polar stationary phases in HILIC [30]. The observed retention factor of caffeine is not well correlated with the phase ratio as reflected by a relatively low correlation coefficient (r = 0.689), indicating the retention of caffeine is not mainly controlled by partitioning. This has been observed in a previous study [30]. The selected test compounds were also evaluated on the Cogent Diol phase, and linear relationships between the observed retention factor and phase ratio were observed (graphs shown in Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2.

The observed retention factors measured at different phase ratios on the Cogent Amide phase: (a) caffeine, 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine; (b) theophylline, theobromine, adenosine, and vidarabine. The mobile phase contains 85% acetonitrile, and the ammonium acetate concentration is in the range of 8–36 mM.

Linear regression was performed on the retention data of the non-ionized test compounds obtained on the Cogent Amide, Cogent Diol, and XBridge Amide phases. The slopes of the linear regression lines provide the partitioning coefficients of the test compounds (K) in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile, as presented in Table 2. Since hydrophilic partitioning takes place between the adsorbed water layer and bulk mobile phase, the partitioning coefficients are theoretically independent of the type of the stationary phase. As shown in Table 2, the partitioning coefficients of the test compounds obtained on three different columns are not significantly different. The relative standard deviation is below 2% for most test compounds. The standard errors for dimethylxanthine isomers are relatively higher, which is likely related to weak retention of these compounds at 85% acetonitrile. The partitioning coefficient data provides evidence to support hydrophilic partitioning as a retention mechanism on the silica hydride-based stationary phases. It is interesting to note the partitioning coefficients of the positional and configurational isomers included in this study. For monomethylated xanthin isomers, an ANOVA test confirms that the partitioning coefficients of the three monomethylated xanthin isomers are not significantly different. For dimethylxanthine isomers, the partitioning coefficients are relatively small and are not significantly different based on the ANOVA test. However, the partitioning coefficients of 1,3-dimethylxanthine (theophylline) and 3,7-dimethylxanthine (theobromine) appear to be significantly different when evaluated separately using a t-test.

Table 2.

Partitioning coefficients (K) of the selected test compounds at 85% acetonitrile.

The partitioning coefficients of the non-ionized test compounds and phase ratio (KΦ) were used to calculate the retention contributed by the partitioning mechanism (kpar). The intercepts of the linear regression lines (Figure 2) yielded the retention contributed by adsorption (kads). Table 3 presents the retention contributed by both the partitioning (kpar) and adsorption (kads) mechanisms in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile and 24 mM ammonium acetate on the Cogent Amide, Cogent Diol, and XBridge Amide phases. First, uridine is predominantly retained by partitioning on the silica hydride-based phases. Small negative intercepts (negative kads values) are likely related to experimental errors; however, it might also be a sign of some unique retention behaviors of uridine on the silica hydride-based phases. Negative intercepts have been reported in previous studies and were attributed to incomplete access to the entire adsorbed water layer on the polymer-based stationary phase in the partitioning process in HILIC [30]. However, it is not clear whether the negative intercepts are related to the accessibility of the adsorbed water layer in this study. Further studies are needed to gain a better understanding of the retention behaviors on the silica hydride-based phases. In comparison, partitioning contributes about 90% of the observed retention on the XBridge Amide phase, and surface adsorption is less significant, contributing only 12.7% of the observed retention. Second, hydrophilic partitioning is found to be the main retention mechanism for 2-deoxyuridine (2-dU), adenosine, vidarabine, and three monomethylated xanthine isomers on the silica hydride-based phases with hydrophilic partitioning contributing 58.0–84.8% of the observed retention. Surface adsorption is a minor retention mechanism contributing 11.5–41.4% of the observed retention. It is noted that the data in Table 3 reveals similar retention mechanisms for these compounds on the hybrid silica-based amide phase (XBridge Amide). Interestingly, the retention contributed by adsorption (kads) is different for cytosine, 2-dU, adenosine, and vidarabine but similar for three monomethylated xanthine isomers on the Cogent Amide and Diol phases. This may reflect the difference in polar interactions of the test compounds with amide and diol groups on the silica-hydride surface. In comparison, surface adsorption on the XBridge Amide phase contributes more to the observed retention for 2-dU, adenosine, vidarabine, and monomethylated xanthine isomers than on the Cogent Amide phase. Since the bonding density or surface coverage data is not available, it is difficult to fully explain this observation. A possible explanation might be that these test compounds might interact with the surface silanol groups on the hybrid silica surface, which are minimal on the silica hydride surface. Finally, surface adsorption is the main retention mechanism for three dimethylxanthine isomers on all three stationary phases, contributing 57.7–75.6% of the observed retention and partitioning is the minor retention mechanism. Even though the observed retention factors of three dimethylxanthine isomers are similar on the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases, surface adsorption seems to be slightly stronger on the Cogent Amide phase than on the XBridge Amide phase. More contributions by partitioning (kpar) on the XBridge Amide phase than on the Cogent Amide phase can be attributed to the higher phase ratio of the XBridge Amide phase.

Table 3.

Quantitative retention contributions from partitioning (kpar) and adsorption (kads) for non-ionized test compounds on the Cogent Diol, Cogent Amide, and XBridge Amide phases *.

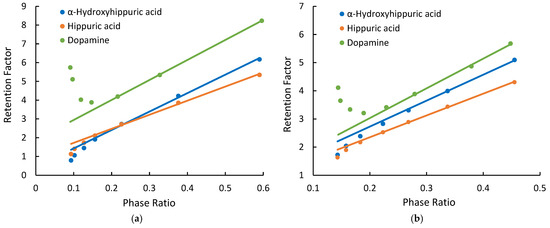

4.3. Retention Mechanisms of Ionized Compounds

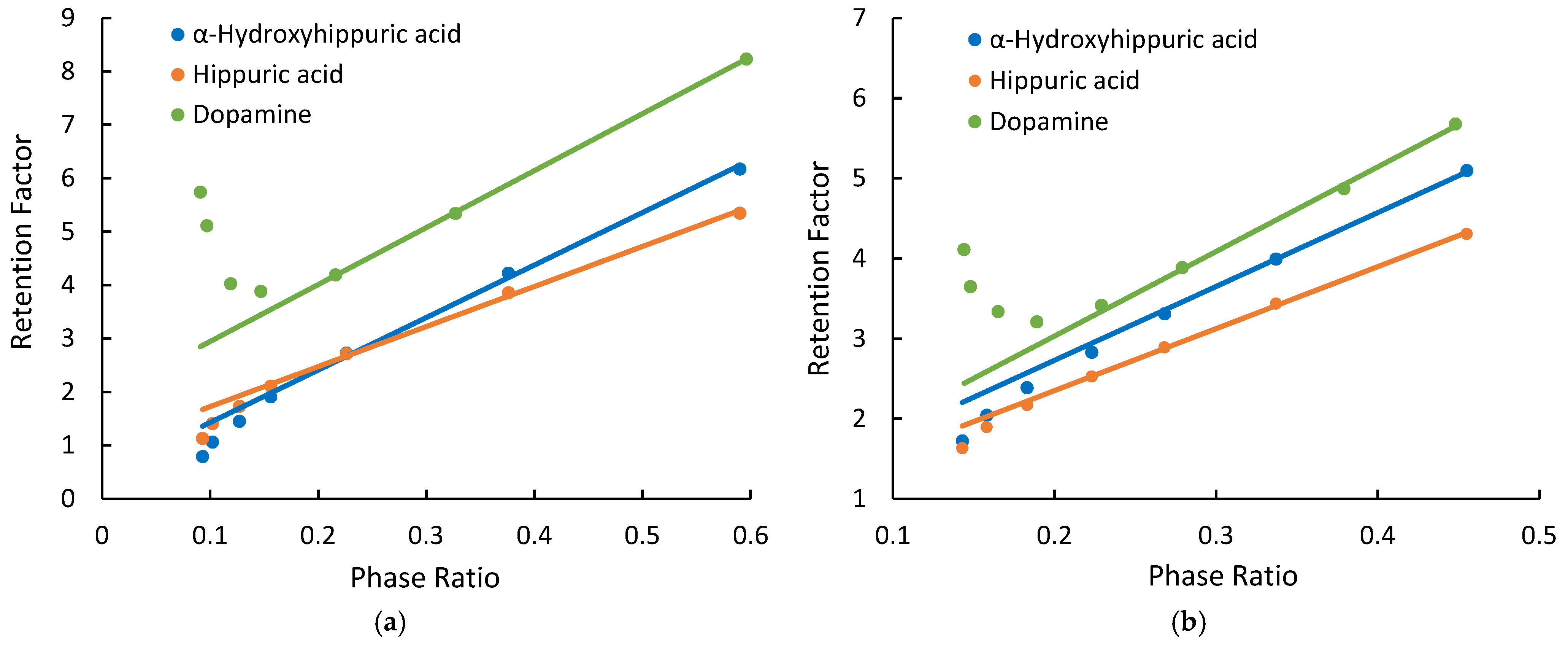

Dopamine, hippuric acid, and α-hydroxyhippuric acid were used to evaluate retention behaviors of ionized compounds. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the retention factors of the ionized test compounds and phase ratio on the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases. At lower phase ratios (i.e., lower salt concentrations), deviation from linearity is observed on both amide phases. Positively charged dopamine displays a positive deviation, indicating the effect of electrostatic attraction. In comparison, hippuric and α-hippuric acids are negatively charged in the mobile phase and have small negative deviation, indicating the effect of electrostatic repulsion. Similar behaviors of the ionized compounds are also observed on the Cogent Diol phase (Supplementary Materials). In the mobile phase used in this study, the residual silanol groups on the hybrid silica surface (XBridge Amide) are at least partially ionized (depending on its actual pKa) and can have electrostatic interactions with the ionized test compounds. The observation of the electrostatic effects on the silica hydride-based phases suggests that there are negative charges on the silica hydride surface. Previous studies have shown that hydroxide ions can accumulate on the hydrophobic surface of silica hydride, thus imparting negative charges to the silica hydride-based phases [15,16,17,18]. Electrostatic effects are observed at lower phase ratios (i.e., salt concentrations) for both the positively charged and negatively charged test compounds on the silica hydride-based phases, as shown in Figure 3. At higher salt concentrations, the linear relationship between the observed retention factor and phase ratio (kobs vs. Φ) is restored. Figure 3 also shows the linear regression lines obtained at higher phase ratios (i.e., high salt concentrations) with the coefficients of determination (R2) ranges 0.9982–1.000 on the Cogent Amide phase and 0.9992–0.9994 on the XBridge Amide phase.

Figure 3.

The observed retention factors of dopamine, α-hydroxyhippuric acid, and hippuric acid measured at different phase ratios (a) on the Cogent Amide phase; (b) on the XBridge Amide phase. The mobile phase contains 85% acetonitrile, and the ammonium acetate concentration is in the range of 8–36 mM.

The retention data was quantitatively analyzed to evaluate the effect of electrostatic interactions for the ionized test compounds. First, the partitioning coefficients and the retention contributed by surface adsorption (kads) were obtained through linear regression of the linear segment of the observed retention factor and phase ratio (kobs vs. Φ) plots (see regression lines in Figure 3). The partitioning coefficients (K) of the ionized compounds measured on three columns (Cogent Amide, Cogent Diol, and XBridge Amide) were found to be 10.39 ± 0.37 for dopamine, 9.76 ± 0.39 for α-hydroxyhippuric acid, and 7.54 ± 0.34 for hippuric acid. The relative standard deviation (RSD%) for partitioning coefficients is less than 5% based on three replicates. Second, the retention contributed by hydrophilic partitioning (kpar) was calculated by multiplying the partitioning coefficient and phase ratio (KΦ). Finally, the electrostatic effects (kelec), either attractive or repulsive, were calculated using Equation (3). Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 present the quantitative retention contributions by partitioning, adsorption, and electrostatic interactions for dopamine, α-hydroxyhippuric acid, and hippuric acid at various ammonium acetate concentrations. As shown in Table 4, electrostatic attraction contributes significantly to the retention of dopamine at 8 mM ammonium acetate, 50% on the Cogent Amide phase, and 32% on the XBridge Amide phase. As expected, the effect of electrostatic attraction decreases with salt concentration and becomes negligible at 30 mM ammonium acetate. It is interesting to note that electrostatic attraction contributes more to the observation retention on the Cogent Amide phase than on the XBridge Amide phase, for example, 50.4% vs. 31.9% at 8 mM ammonium acetate and 11.3% vs. 2.2% at 24 mM ammonium acetate, indicating the Cogent Amide phase has a stronger electrostatic effect than the XBridge Amide phase. This finding is consistent with the previously published results that alkylbenzylamines were more strongly retained on the Type C silica than on Type B silica phase [15]. These results indicate that the charge density may be higher on the silica hydride surface than on the hybrid silica surface, even though there are minimal silanol groups on the silica hydride surface. In comparison, hydrophilic partitioning is the main retention mechanism for dopamine only at the ammonium acetate concentration above 24 mM on the Cogent Amide phase but becomes the main mechanism at 12 mM on the XBridge amide phase. Surface adsorption for dopamine is much stronger on the Cogent Amide phase than on the XBridge Amide phase. In contrast, the retention of negatively charged α-hydroxyhippuric acid and hippuric acid is reduced significantly by electrostatic repulsion at 8 mM ammonium acetate, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6. Electrostatic repulsion seems to be stronger on the Cogent Amide phase than on the XBridge Amide phase. This is consistent with stronger electrostatic attraction observed for dopamine on the Cogent Amide phase (Table 4). The effect of electrostatic repulsion (kelec) is quickly weakened by the salt concentration and becomes negligible above 18 mM ammonium acetate. Quantitative retention data in Table 5 and Table 6 indicates that α-hydroxyhippuric acid and hippuric acid are predominantly retained by partitioning on both the amide phases regardless of the electrostatic effect. Surface adsorption is only a minor retention mechanism for both α-hydroxyhippuric acid and hippuric acid contributing 5.5–21.7% of the observed retention.

Table 4.

Quantitative retention contributions from partitioning (kpar), adsorption (kads), and electrostatic interactions (kelec) for dopamine on the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile.

Table 5.

Quantitative retention contributions from partitioning (kpar), adsorption (kads), and electrostatic interactions (kelec) for α-hydroxyhippuric acid on the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile.

Table 6.

Quantitative retention contributions from partitioning (kpar), adsorption (kads), and electrostatic interactions (kelec) for hippuric acid on the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases in the mobile phase containing 85% acetonitrile.

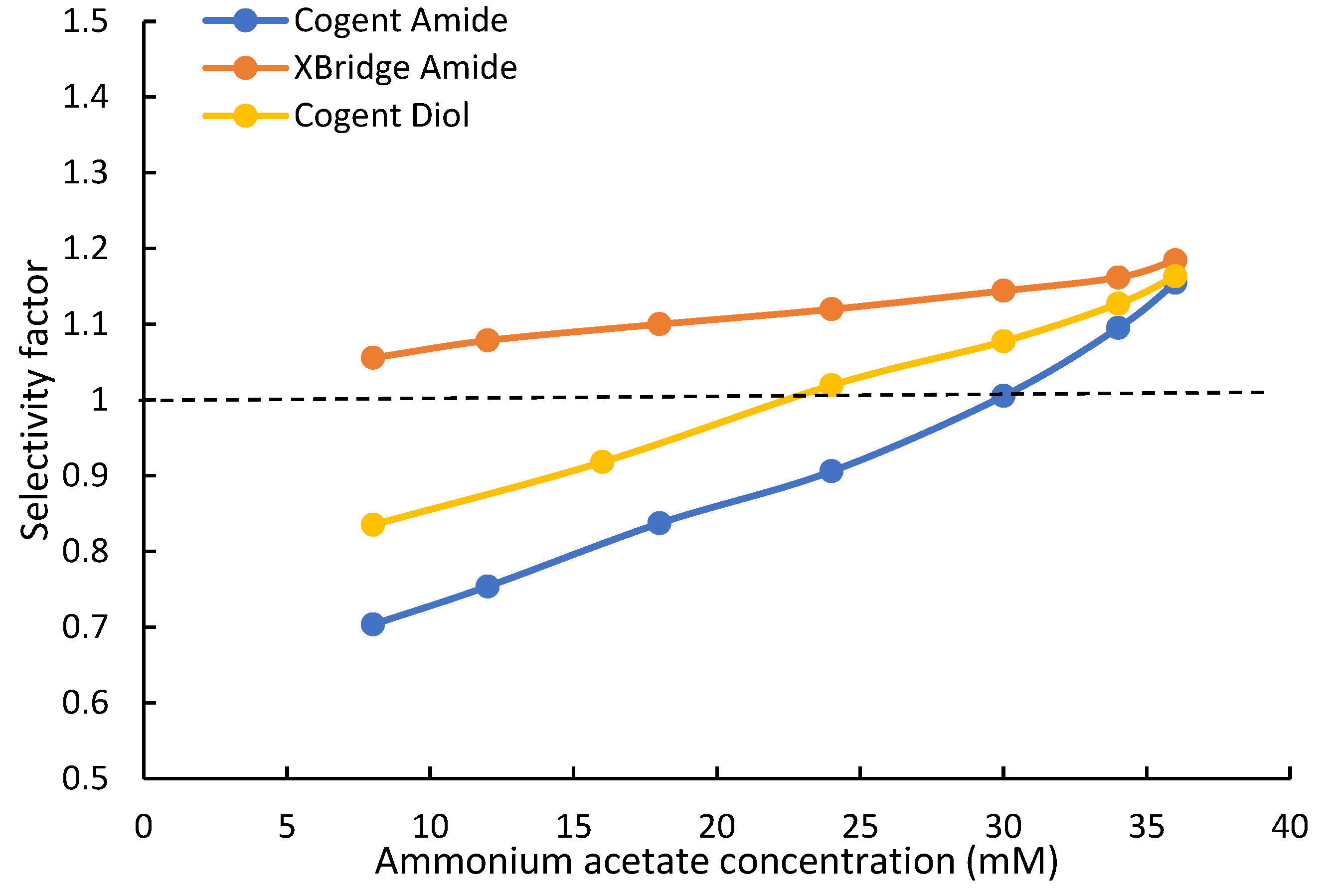

4.4. Selectivity Evaluation

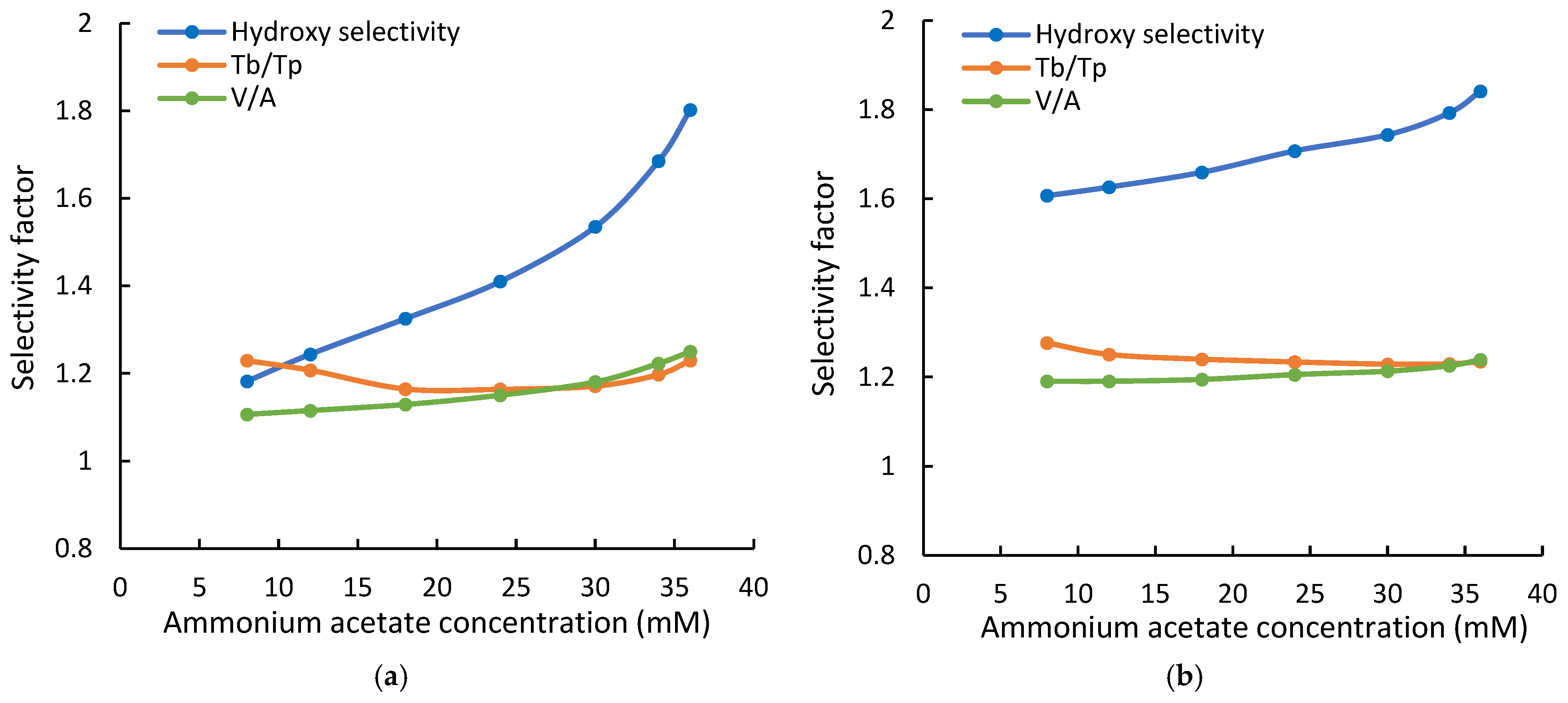

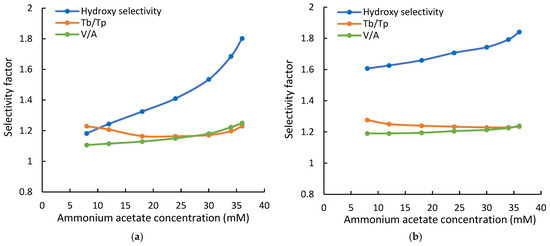

The selectivity of the Cogent Amide and XBridge Amide phases was evaluated using the retention data in this study. Uridine (U) and 2-deoxy uridine (2dU) were used to test hydroxy selectivity (αOH) as suggested in the Ikegami selectivity test [32]. The hydroxy selectivity at various ammonium acetate concentrations is shown in Figure 4. The hydroxy selectivity for both amide phases increases with the ammonium acetate concentration and is very similar at the highest salt concentration of 36 mM. However, the hydroxy selectivity of the Cogent Amide phase seems to be more affected by the salt concentration, thus the phase ratio. It should be noted that the hydroxy selectivity for both amide phases is below the ratio of the partitioning coefficients for uridine and 2-deoxyuridine (KU/K2dU~2.0). Uridine is retained by partitioning entirely on the Cogent Amide phase and predominantly on the XBridge Amide phase (see Table 3). In comparison, adsorption is a minor retention mechanism for 2-deoxyuridine (2dU) on both amide phases. Therefore, the hydroxy selectivity factor αOH is related to the partitioning coefficients, phase ratio (Φ), and the retention contributed by adsorption as shown in Equation (4):

Figure 4.

The hydroxy selectivity, configurational selectivity (V/A), and the selectivity for theobromine and theophylline (Tb/Tp) at various ammonium acetate concentrations (a) on the Cogent Amide phase; (b) on the XBridge Amide phase. The mobile phase contains 85% acetonitrile, and the ammonium acetate concentration is in the range of 8–36 mM.

The retention contributed by adsorption is negligible for uridine (kads,U) but significant relative to the retention contributed by partitioning for 2-deoxyuridine (kads,2dU). This makes the hydroxy selectivity factor less than the ratio of the partitioning coefficients (KU/K2dU). As the salt concentration (and phase ratio Φ) increases, partitioning contributes (KΦ) more to the observed retention of 2-deoxyuridine, but the retention contributed by adsorption remains constant. Thus, the hydroxy selectivity increases with salt concentration. Larger hydroxy selectivity factors of the XBridge Amide phase at lower salt concentration (i.e., phase ratio) are possibly related to more retention contributed by adsorption (Table 3) since the retention contribution by partitioning is similar.

Vidarabine and adenosine are configurational isomers used in the Ikegami selectivity test [31]. As shown in Figure 4, the configurational selectivity (αV/A) increases slightly with the salt concentration for both amide phases. Although partitioning has been shown to be the main retention mechanism for both vidarabine and adenosine, adsorption makes significant contributions to the observed retention (Table 3). As the salt concentration (and phase ratio) increases, the retention contributed by partitioning becomes more dominant, leading to increasing selectivity factor. However, the effect of the salt concentration is relatively small due to constant retention contribution by adsorption. In contrast, the selectivity for the positional isomers, theobromine, and theophylline (αTb/Tp) decreases with the salt concentration and phase ratio on both amide phases, as shown in Figure 4. There is a small increase above 30 mM ammonium acetate on the Cogent Amide phase. For theobromine and theophylline, adsorption is the main retention mechanism and is independent of the salt concentration (Figure 2). As the salt concentration and phase ratio increase, partitioning becomes more significant for both isomers, leading to a decrease in the selectivity factor.

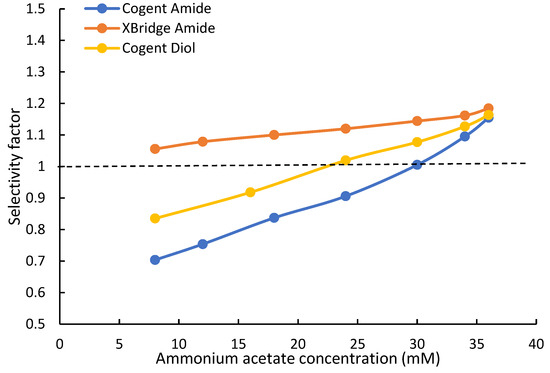

Hippuric acid and α-hydroxyhippuric acid are structurally related, and the only difference is the hydroxy group at the alpha position in α-hydroxyhippuric acid. The hippuric acid selectivity factor (αHA) is defined as the ratio of the retention factors of α-hydroxyhippuric and hippuric acids in this study. The hippuric acid selectivity factors (αHA) are plotted against salt concentration, as shown in Figure 5. First, α-hydroxyhippuric acid elutes before hippuric acid on the XBridge Amide phase; thus, the selectivity factor (αHA) is above unity. Since the main retention mechanism for both acids is partitioning, the selectivity factor (αHA) increases with the salt concentration. As discussed earlier, both acids experience electrostatic repulsion on the XBridge Amide phase at low salt concentrations. If the selectivity factor is calculated without the influence of electrostatic repulsion, the selectivity factor would be slightly higher at 8 and 12 mM ammonium acetate. This indicates that electrostatic repulsion reduces selectivity at low salt concentrations. In comparison, the Cogent Amide and Diol phases display different selectivity for hippuric acid especially at low salt concentrations. It should be noted that the hippuric acid selectivity factor on both silica hydride-based phases is below unity at the salt concentration below 24 mM for the Cogent Diol and 30 mM for the Cogent Amide phase. This is because the elution order of α-hydroxyhippuric and hippuric acids is reversed with hippuric acid eluting before α-hydroxyhippuric acid on both the silica hydride-based phases. Although selectivity factor is typically larger than unity by convention, the same definition of the selectivity factor for hippuric acid (αHA) is kept to avoid confusion. As shown in Table 5 and Table 6, hippuric acid and α-hydroxyhippuric acid experience similar electrostatic repulsion; however, hippuric acid has much stronger surface adsorption than α-hydroxyhippuric at low salt concentrations and phase ratios. Even though α-hydroxyhippuric acid has a slightly larger partitioning coefficient than hippuric acid, the difference in the retention contributed by partitioning is smaller than that in the retention contributed by adsorption, resulting in the reversal of the elution order. If the hippuric acid selectivity factors are calculated without counting the electrostatic effect (i.e., using only kpar + kads in Table 5 and Table 6), the selectivity factors would be still below unity but slightly higher than those calculated using the observed retention factors. This implies that the effect of electrostatic repulsion enhances selectivity, which is opposite to the observation on the XBridge Amide phase. As salt concentration and phase ratio increases, the retention contributed by partitioning becomes more dominant. This results in reducing selectivity with the constant retention contributed by adsorption (similar to the selectivity for theobromine and theophylline). In fact, hippuric acid and α-hydroxyhippuric acid co-elute at 24 mM ammonium acetate on the Cogent Diol phase and 30 mM on the Cogent Amide phase. At higher salt concentrations, the elution order becomes the same as that on the XBridge Amide phase; and the hippuric acid selectivity factor increases with salt concentration. The hippuric acid selectivity factors of the Cogent Diol and Amide phases are very similar and only slightly below that of the XBridge Amide phase at 36 mM ammonium acetate.

Figure 5.

Selectivity for α-hydroxyhippuric acid and hippuric acid on the Cogent Amide, Cogent Diol, and XBridge Amide phases. The mobile phase contains 85% acetonitrile, and the ammonium acetate concentration is in the range of 8–36 mM. Dashed line indicates selectivity of one below which the elution order is reversed.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We have investigated the characteristics of two silica hydride-based (Type C silica) polar stationary phases and the retention mechanisms of selected polar compounds in this study. Although the surface of unmodified silica hydride is relatively hydrophobic and has low excess absorbed water, modification with polar bonded phases renders the silica hydride surface more hydrophilic and able to adsorb a significant amount of excess water. The absorbed water layer on the Cogent Diol phase is similar to that on the XBridge Amide phase and more than that on the Cogent Amide phase at ammonium acetate concentration below 30 mM. At higher ammonium acetate concentrations, the adsorbed water layer on the silica hydride-based phases is even slightly more than that on the hybrid silica-based phase. The presence of a significant adsorbed water layer on the modified silica hydride surface allows hydrophilic partitioning of polar compounds. The quantitative assessment results indicate that the retention mechanisms of both non-ionized and ionized test compounds on the silica hydride-based polar phases are not drastically different from that on the hybrid silica-based phase in HILIC. The retention behaviors of ionized compounds reveals that there are significant amounts of negative charges on the modified silica hydride surface. This is consistent with the hydroxide ion accumulation model that was previously published [15,16,17,18]. Quantitative assessment results indicate that electrostatic interactions with the ionized compounds are relatively stronger on the silica hydride-based phases than on the hybrid silica-based phase. Despite the similarities in the absorbed water layer and retention mechanisms, the silica hydride-based phase is found to have some different selectivity than the hybrid silica-based amide phase, for example, hydroxy selectivity, selectivity for positional and configurational isomers, and negatively charged acids.

Although the quantitative assessment methodology has been successfully applied to provide useful insights into the retention mechanisms of polar compounds on the silica hydride-based polar phases, the current research evaluated only a small number of test compounds, particularly the ionized compounds. The unmodified silica hydride was not evaluated in this study, which prohibits direct comparison between the unmodified and modified silica hydride-based phases. In addition to evaluating more silica hydride-based phases, other studies are needed toward a comprehensive understanding of silica-hydride-based polar phases. Because the unmodified silica hydride surface contains a low level of excess water, it has been hypothesized that retention reproducibility may improve due to reduced variability in water content. However, since the adsorbed water layer can influence both reproducibility and equilibration time, it remains unclear whether silica-hydride-based bonded phases indeed offer superior reproducibility. Further investigations are, therefore, required to systematically evaluate both reproducibility and equilibration behavior. According to manufacturer specifications, the Cogent Amide column is stable over a pH range of 2–10, comparable to that of the XBridge Amide column (pH 2–11), which is designed for enhanced stability under extreme pH conditions. Nevertheless, stability data in the peer-reviewed literature remains limited. In addition, comprehensive selectivity studies of silica-hydride-based bonded phases are needed using established selectivity tests (e.g., Ikegami selectivity tests) to enable meaningful comparisons with other polar stationary phases.

Quantitative assessment of retention mechanisms provides evidence that there may not be any significant differences in retention mechanisms between the aqueous normal phase chromatography (ANP) using the silica hydride-based polar phase and HILIC using the polar phases on the Type B silica for polar compound separation. Clarification of the terminology may help reduce confusion and facilitate method development. With more information available on reproducibility, stability, and selectivity, the silica hydride-based phases have the potential to expand the applications and provide practicing scientists with more options for column selection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010017/s1. Figure S1: The observed retention factor measured at different phase ratios on the Cogent Diol phase. Figure S2: The observed retention factors of dopamine, α-hydroxyhippuric acid, and hippuric acid measured at different phase ratios on the Cogent Diol phase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, Y.G.; formal analysis, Y.G. and M.Z.; investigation, Y.G. and M.Z.; resources, Y.G.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. and M.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by US National Science Foundation, grant ID 2402756.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Cogent Diol and Amide columns used in this study are kindly provided by Microsolv Technology Corp.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANP | Aqueous normal phase |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic interaction chromatography |

References

- Vinjamuri, B.P.; Pan, J.; Peng, P. A review on commercial oligonucleotide drug products. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 113, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; AlShaer, D.; Al Musaimi, O. Oligonucleotides: Evolution and innovation. Med. Chem. Res. 2024, 33, 2204–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornstedt, T.; Enmark, M. Separation of therapeutic oligonucleotides using ion-pairing reversed-phase chromatography based on fundamental separation science. J. Chromatogr. Open 2023, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Separation of nucleobases, nucleosides, nucleotides and oligonucleotides by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC): A state-of-the-art review. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1738, 465467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaducci, M.A.; Fochetti, A.; Ciogli, A.; Mazzoccanti, G. A compendium of the principal stationary phases used in hydrophilic interaction chromatography: Where have we arrived? Separations 2023, 10, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. A survey of polar stationary phases for hydrophilic interaction chromatography and recent progress in understanding retention and selectivity. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2022, 36, e5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.H.; Jonsson, E.; Auvinen, M.; Pesek, J.J.; Sandoval, J.E. A new approach for the preparation of a hydride-modified substrate used as an intermediate in the synthesis of surface-bonded materials. Anal. Chem. 1993, 65, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesek, J.J.; Matyska, M.T. Silica hydride: A separation material every analyst should know about. Molecules 2021, 26, 7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesek, J.J.; Matyska, M.T.; Hearn, M.T.W.; Boysen, R.I. Aqueous normal-phase retention of nucleotides on silica hydride columns. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appulage, D.K.; Schug, K.A. Silica hydride-based phases for small molecule separations using automated liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method development. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1507, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesek, J.J.; Matyska, M.T.; Tardiff, E.; Hiltz, T. Chromatographic characterization of a silica hydride-based amide stationary phase. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 2728–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, J.; Jandera, P. Hydrosilated silica-based columns: The effects of mobile phase and temperature on dual hydrophilic-reversed-phase separation mechanism of phenolic acids. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1228, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesek, J.J.; Matyska, M.T. A comparison of two separation modes: HILIC and aqueous normal phase chromatography. LCGC N. Am. 2007, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, J.J.; Matyska, M.T.; Boysen, R.I.; Yang, Y.; Hearn, M.T.W. Aqueous normal-phase chromatography using silica-hydride-based stationary phases. Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 42, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, S.; Sutcliffe, O.B.; Euerby, M.R.; Bawazeer, S.; Watson, D.G. A comparison of the chromatographic properties of silica gel and silicon hydride modified silica gels. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1263, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsing, C.; Yang, Y.; Munera, C.; Tse, C.; Matyska, M.T.; Pesek, J.J.; Boysen, R.I.; Hearn, M.T.W. Correlation between the zeta potentials of silica hydride-based stationary phases, analyte retention behavior and their ionic interaction descriptors. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 817, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsing, C.; Nolvachai, Y.; Marriot, P.J.; Boysen, R.I.; Matyska, M.T.; Pesek, J.J.; Hearn, M.T.W. Insights into the origin of the separation selectivity with silica hydride adsorbents. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 3063–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulsing, C.; Yang, Y.; Boysen, R.I.; Matyska, M.T.; Pesek, J.J.; Hearn, M.T.W. Role of electrostatic contributions in the separation of peptides with silica hydride stationary phases. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, J.; Janas, P.; Jandera, P. Gradient elution in aqueous normal-phase liquid chromatography on hydrosilated silica-based stationary phases. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1286, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barto, E.; Felinger, A.; Jandera, P. Investigation of the temperature dependence of water adsorption on silica-based stationary phases in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1489, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, J.; Jandera, P. Adsorption of water from aqueous acetonitrile on silica-based stationary phases in aqueous normal-phase liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1374, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, S.M.; Holtzel, A.; Seidel-Morgenstern, A.; Tallarek, U. A molecular dynamics view on hydrophilic interaction chromatography with polar-based phases: Properties of the water-rich layer at a silica surface modified with diol-functionalized alkyl chains. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 13126–13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstrom, P.; Irgum, K. Hydrophilic interaction chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2006, 29, 1784–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Muscatiello, D. An update on the progress in fundamental understanding of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2026, 1765, 466520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, G.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xue, X.; Jin, Y.; Liang, X. Study on the retention equation in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Talanta 2008, 76, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandera, P.; Hajek, T. A new definition of the stationary phase volume in mixed-mode chromatographic columns in hydrophilic liquid chromatography. Molecules 2021, 26, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bhalodia, N.; Fattal, B.; Serris, I. Evaluating the adsorbed water layer on the polar stationary phases in hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Separations 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fattal, B. Relative significance of hydrophilic partitioning and surface adsorption to the retention of polar compounds in hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Anal. Chimi. Acta 2021, 1184, 339025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Baran, D.; Ryan, L. Quantitative assessment of retention mechanisms of ionized compounds in hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 4057–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Baran, D. Hydrophilic partitioning or surface adsorption? A quantitative assessment of retention mechanisms for hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC). Molecules 2023, 28, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.; Muscatiello, D.; Gutierrez, Z.; Asare, V.; Guo, Y. Quantitative assessment of retention mechanisms of nucleosides on a bare silica stationary phase in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC). Analytica 2025, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, Y.; Ikegami, T.; Takubo, H.; Ikegami, Y.; Miyamoto, M.; Tanaka, N. Chromatographic characterization of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography stationary phases: Hydrophilicity, charge effects, structural selectivity, and separation efficiency. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 5903–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.