Advances in Biochar-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion: Effects on Process Stability, Methanogenic Pathways, and Digestate Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biochar

2.1. Biochar Production

2.2. Properties of Biochar

2.3. Application of Biochar

3. Influence of Biochar on Anaerobic Digestion

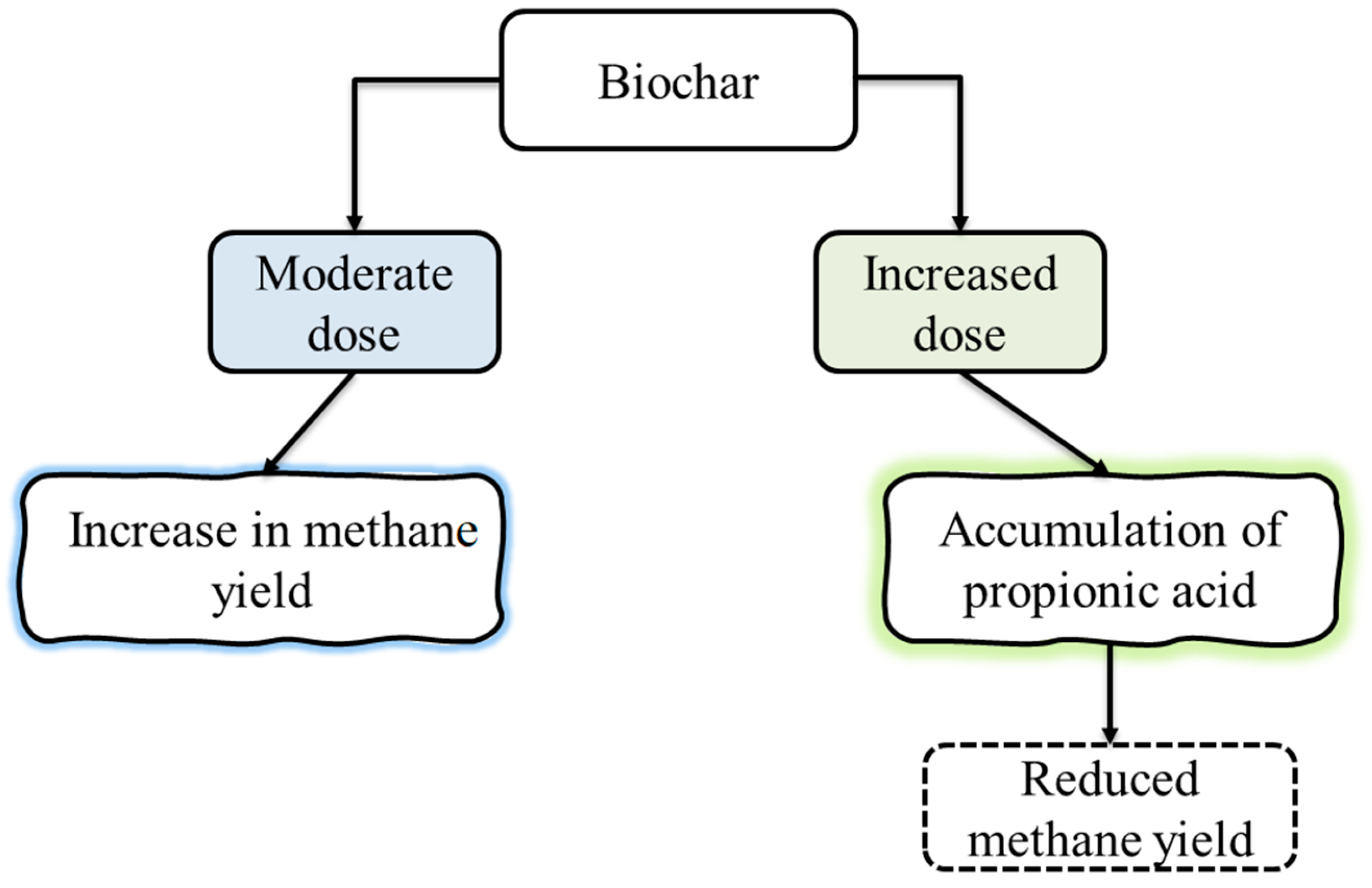

3.1. Effects of Biochar on Methane Yield

Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature and Feedstock Source of Biochar on Methane Yield

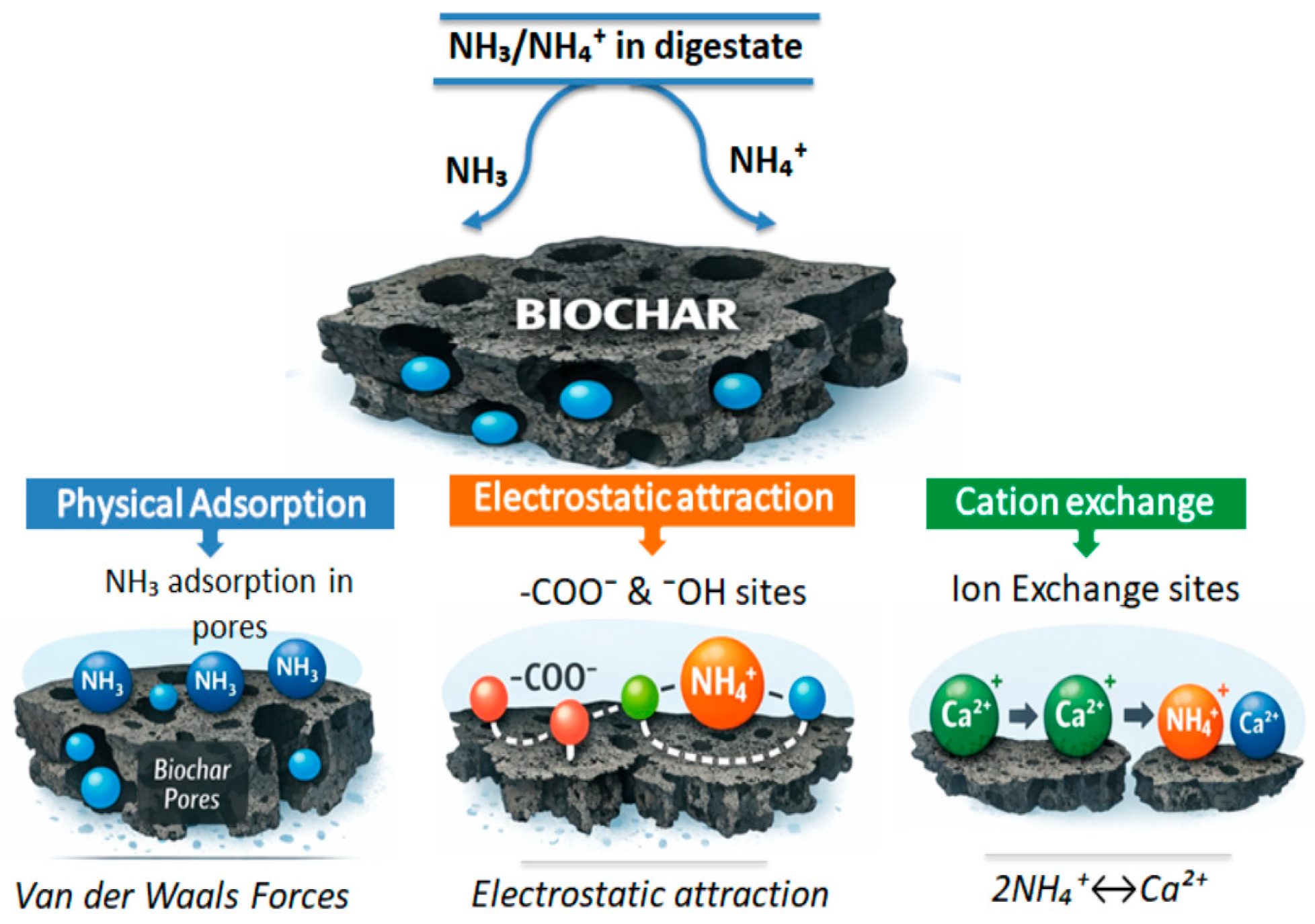

3.2. Effects of Biochar on Ammonia Inhibition

3.3. The Influence Biochar on the Production of VFAs and pH

3.4. Impact of Biochar on Microbial Structures

3.4.1. Syntrophy Mechanisms

3.4.2. Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer

3.4.3. The Impact of Biochar on Methanogenic Archaea and DIET

4. Digestate Quality

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VFAs | Volatile fatty acids |

| GAC | Granular activated carbon |

| HTC | Hydrothermal carbonization |

| TAN | Total ammonia nitrogen |

| SIET | Shuttled interspecies electron transfer |

| DIET | Direct interspecies electron transfer |

| EDA | Electron donor-acceptor |

References

- Kosnar, Z.; Mercl, F.; Pierdona, L.; Chane, A.D.; Micha, P.; Tulstos, P. Cocentration of the main persistent organic pollutants in sewage sludge in relation to wastewater treatment plant and sludge stabilization. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uggetti, E.; Ferrer, I.; Llorens, E.; García, J. Sludge treatment wetlands: A review on the state of the art. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2905–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkrishna, A.; Ghosh, S.; Kaushik, I.; Arya, V.; Joshi, D.; Semwal, D.; Saxena, A.; Singh, S. Sequential distribution, potential sources, and health risk assessment of persistent toxic substances in sewage sludge used as organic fertilizer in Indo Gangetic region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 2324–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegl, T. Anaerobic digestion BioModel upgraded by various inhibition types. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, B.; Flotats, X. Citrus essential oils and their influence on the anaerobic digestion process: An overview. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2063–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano-López, N.; Borrás, L.; Seco, A.; Aguado, D. Unveiling microbial structures during raw microalgae digestion and co-digestion with primary sludge to produce biogas using semi-continuous AnMBR systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, S.P.; Havukainen, J. Anaerobic digestion: Factors affecting anaerobic digestion process. In Waste Bioremediation. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Varjani, S., Gnansounou, E., Gurunathan, B., Pant, D., Zakaria, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D. Advances in enhanced volatile fatty acid production from anaerobic fermentation of waste activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, K.; Rybarczyk, P.; Hołowacz, I.; Łukajtis, R.; Glinka, M.; Kaminski, M. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Materials as Substrates for Fermentation Processes. Molecules 2018, 23, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rodriguez, J.; Perez, M.; Romero, L.I. Semicontinuous temperature-phased anaerobic digestion (TPAD) of organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW). Comparison with single-stage processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 285, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Wang, H. Volatile fatty acids productions by mesophilic and thermophilic sludge fermentation: Biological responses to fermentation temperature. Bioresour. Tehnol. 2015, 175, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh Nguyen, V.; Kumar Chaudhary, D.; Hari Dahal, R.; Hoang Trinh, N.; Kim, J.; Woong Chang, S.; Hong, Y.; Duc La, D.; Cuong Nguyen, X.; Hao Ngo, H.; et al. Review on pretreatment techniques to improve anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. Fuel 2021, 285, 119105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, M.T.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Białowiec, A. Direct interspecies electron transfer mechanisms of a biochar amended anaerobic digestion: A review. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-S.; Chang, J.-S.; Lee, D.-J. Adding carbon-based materials on anaerobic digestion performance: A mini-review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappero, M.; Norouzi, O.; Hu, M.; Demicheils, F.; Berruti, F.; Di Maria, F.; Mašek, O.; Fiore, S. Review of biochar role as additive in anaerobic digestion processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Sánchez, M.E.; Gómez, X. Enhancing anaerobic digestion: The effect of carbon conductive materials. J. Carbon Res. 2018, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, F.; Luo, C.; Shao, L.; He, P. Biochar alleviates combined stress of ammonium and acids by firstly enriching Methanosaeta and then Methanosarcina. Water Res. 2016, 90, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, E.S.; Bahnasawy, A.; Hamouda, R.; Sabahy, A.; Abbas, W.; Morsy, O.M. Biochar production under different pyrolysis temperatures with different types of agricultural wastes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, T.; Strezov, V.; Evans, T.J. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis: A review of product properties and effects of pyrolysis parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Sahu, J.N.; Ganesan, P. Effects of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste trough pyrolysis: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli, P.R.; Buonomo, E.L.; Cukierman, A.L. Pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse and co-pyrolysis with an argentinean subbituminous coal. Energy. Sour. Part A 2007, 29, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, Z. Sorption of naphthalene and 1-naphthol by biochars of orange peels with different pyrolytic temperatures. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, A.; Se, S.-M.; Dimin, M.F.; Juoi, J.M.; Husin, M.H.; Mitan, N.M.M. Influence of heating temperature and holding time on biochars derived from rubber wood sawdust via slow pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2014, 107, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, M.; Dutta, S.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Tsang, D.C.W. Hydrothermal carbonization and liquefaction for sustainable production of hydrochars and aromatics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jordan, B.; Berge, N.D. Thermal conversion of municipal solid waste via hydrothermal carbonization: Comparison of carbonization products to products from current waste management techniques. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambo, H.S.; Dutta, A. A comparative review of biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physic-chemical properties and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.B.; Sharma, A.K.; Dubey, B. Hydrothermal carbonization of renewable waste biomass for solid biofuel production: A discussion on process mechanism, the influence of process parameters, environmental performance and fuel properties of hydrochar. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 123, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Gao, B. Minireview of potential applications of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 57, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.H.; Xu, R.K.; Zhang, H. The forms of alkalis in the biochar produced from crop residues at different temperature. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3488–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariyar, P.; Kumari, K.; Jain, M.K.; Jadhao, P.S. Evaluation of change in biochar properties derived from different feedstock and pyrolysis temperature for environmental and agricultural application. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, M.; Akogun, O.; Enweremadu, C. Influence of feedstock mixtures on the fuel characteristics of blended cornhusk, cassava peels, and sawdust briquettes. Biomass Convers. Biorafinery 2023, 13, 16211–16226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.; Tarquis, A.M.; Saa-Requejo, A.; Guerrero, F.; Gascó, G. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on composted sewage sludge biochar priming effect in a loamy soil. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y. Influence of pyrolysis temperature and holding time on properties of biochar derived from medicinal herb (radix isatidis) residue and its effect on soil CO2 emission. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2014, 110, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. The structure evolution of biochar from biomass pyrolysis and its correlation with gas pollutant adsorption performance. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangabhashiyam, S.; Lins, P.V.d.S.; Oliveira, L.M.T.d.M.; Sepulveda, P.; Ighalo, J.O.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Meili, L. Sewage Sludge Derived Biochar for the Adsorptive Removal of Wastewater Pollutants: A Critical Review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V.; Meier, D.; Radlein, D. An overview of fast pyrolysis of biomass. Org. Geochem. 1999, 30, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; Neenu, S.; Rashmi, I.; Meena, B.P.; Jatav, R.C.; Lakaria, B.L.; Patra, A.K. Ameliorating effects of leucaena biochar on soil acidity and exchangeable ions. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2016, 47, 1252–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Riaz, M.; Arif, M.S.; Hafeez, F.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Shahzad, A.N. Biochar soil amendment on alleviation of drought and salt stress in plants: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12700–12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Xia, S. Mechanistic insights into removal of pollutants in adsorption and advanced oxidation processes by livestock manure derived biochar: A review. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.G.; Gloy, B.A.; Joseph, S.; Scott, N.R.; Lehmann, J. Life cycle assessment of biochar systems: Estimating the energetic, economic, and climate change potential. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.I.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.W.; Zimmerman, A.; Mosa, A.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Amrane, A.; Rtimi, S. Mechanisms and adsorption capacities of biochar for the removal of organic and inorganic pollutants from industrial wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 3273–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ma, J.; Zhai, L.; Lou, T.; Mei, Z.; Liu, H. Achievements of biochar application for enhanced anaerobic digestion: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 122058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Key properties identification of biochar material in anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge for enhancement of methane production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Ding, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y. Rethinking the biochar impact on the anaerobic digestion of food waste in bench-scale digester: Spatial distribution and biogas production. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 420, 132115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhu, W.; Yan, X.; Cui, Z. A comparasion and evaluation of the effect of biochar on the anaerobic digestion of excess and anaerobic sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhou, H.; Pan, J. The role of electrochemical properties of biochar to promote methane production in anaerobic digestion. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappero, M.; Fiore, S.; Berruti, F. Impact of biochar on anaerobic digestion: Meta-analysis and economic evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Eskicioglu, C. Effects of biochar on anaerobic digestion: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2845–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-W.; Li, A.-H.; Tang, C.-C.; Zhou, A.-J.; Liu, W.; Ren, X.-Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, A. Biochar reulates anaerobic digestion: Insights to the roles of pore size. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 148219. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Fang, W.; Liang, J.; Nabi, M.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, G. Biochar application in anaerobic digestion: Performances, mechanisms, environmental assessment and circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Hu, B.-B.; Wu, H.-Z.; Zhu, M.-J. Improved methane production with redoxactive/conductive biochar amendment by establishing spatial ecological niche and mediating electron transfer. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vayena, G.; Ghofrani-Isfahani, P.; Ziomas, A.; Grimalt-Alemany, A.; Hong, L.M.K.T.; Ravenni, G.; Angelidaki, I. Impact of biochar on anaerobic digestion process and microbiome compostion; focusing on pyrolysis conditions for biochar formation. Renew. Energy 2024, 327, 121569. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Lü, F.; Shao, L.; He, P. Application of eco-compatible biochar in anaerobic digestion to relieve acid stress and promote the selective colonization of functional microbes. Water Res. 2015, 68, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumme, J.; Srocke, F.; Heeg, K.; Werner, M. Use of Biochars in Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 164, 189−197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.C. Synergetic promotion of synotrophic methane production from anaerobic digestion of complex organic wastes by biochar: Performance and associated mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 812–820. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; He, P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Lü, F. Effects and optimization of the use of biochar in anaerobic digestion of food wastes. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Fagbohungbe, M.O.; Herbert, B.M.J.; Hurst, L.; Ibeto, C.N.; Li, H.; Usmani, S.Q.; Semple, K.T. The challenges of anaerobic digestion and the role of biochar in optimizing anaerobic digestion. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Brown, R.C.; Wen, Z. Biochar as an additive in anaerobic digestion of municipal sludge: Biochar properties and their effects on the digestion performance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 6391–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C. Impacts of different biochar types on the anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 42375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.M.; Choi, Y.-K.; Kan, E. Effects of dairy manure-derived biochar on psychrophilic, mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion of dairy manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 250, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, T.; Nosrati, M.; Mousavi, S.M.; Kermanshahi, R.K. Study of syntrophic anaerobic digestion of volatile fatty acids using enriched cultures at mesophilic conditions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 8, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, C.; Fabbri, D. Biochar enables anaerobic digestion of aqueous phase from intermediate pyrolysis of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 172, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Tang, J.; Niu, Q. The dosage-effect of biochar on anaerobic digestion under the suppression of oily sludge: Performance variation, microbial community succession and potential detoxification mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Xing, Y.; Yao, G.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.C. Redox–active biochar facilitates potential electron tranfer between syntrophic partners to enhance anaerobic digestion under high organic loading rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Hu, T.; Ma, H.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, S.; Ding, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, L. Impacts of biochar derived from oil sludge on anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge: Performance and associated mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Mannina, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, L.; Ni, B. Enchanced high-quality biomethane production from anaerobic digestion of primary sludge by corn stver biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, E.; Bouras, G.; Kalderis, D.; Diamadopoulos, E. Biochar production by sewage sludge pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 101, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qambarani, N.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Won, S.; Shim, S.; Ra, C. Biochar properties and eco-friendly applications for climate change mitigation, waste management, and wastewater treatment: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramrueang, N.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X. Application of biochar and alkalis for recovery of sour anaerobic digesters. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zhu, N. Progress in inhibition mechanisms and process control of intermediates and by-products in sewage sludge anaerobic digestion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.J.; Creamer, K.S. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4044–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, W.; Dong, Q.; Wu, D.; Yang, P.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Peng, X. Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal the key microbial phylotypes affecting anaerobic digestion performance under ammonia stress. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, H.; Duan, X.; Chen, Y. Integrated metagenomic and metaproteomic analyses unravel ammonia toxicity to active methanogens and syntrophs, enzyme synthesis, and key enzymes in anaerobic digestion. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2021, 55, 14817–14827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenigun, O.; Demirel, B. Ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion: A review. Bioprocess Biochem. 2013, 48, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, G. Mitigation of ammonia inhibition trough bioagumentation with different microorganisms during anaerobic digestion: Selection of strains and reactor performance evaluation. Water Res. 2019, 155, 214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.-J.; Liu, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.-S.; Shen, J.-Y.; Pan, Z.-C.; Mu, Y. Material and microbial perspectives on understanding the role of biochar in mitigating ammonia inhibition during anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Xu, C.; Huang, W.; Jiang, M.; Yan, J.; Fan, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Xiao, B.; Song, B. Improving anaerobic digestion of piggery wastewater by alleviating stress of ammonia using biochar derived from rice straw. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirne, D.G.; Paloumet, X.; Björnsson, L.; Alves, M.M.; Mattiasson, B. Anaerobic digestion of lipid-rich waste—Effects of lipid concentration. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhu, M.; Meng, X.; Zhou, J.L.; Zhang, H.; Shen, X. The role of biochar on alleviating ammonia toxicity in anaerobic digestion of nitrogen-rich wastes: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 126924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Fu, X.; Lu, W.; Ye, R.; Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Chusov, A. Effects of conductive carbon materials on dry anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge: Process and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasapoor, M.; Young, B.; Brar, R.; Sarmah, A.; Zhuang, W.Q.; Baroutian, S. Recognizing the challenges of anaerobic digestion: Critical steps toward improving biogas generation. Fuel 2020, 261, 116497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoei, S.; Stokes, A.; Kieft, B.; Kadota, P.; Hallam, S.J.; Eskicioglu, C. Biochar amendment rapidly shifts microbial community structure with enhanced thermophilic digestion activity. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.; Shahsavari, E.; Shah, K.; Surapaneni, A.; Ball, A. Improving bioenergy production in anaerobic digestion systems utilising chicken manure via pyrolysed biochar additives: A review. Fuel 2022, 316, 123374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Wah Tong, Y. Internal enhancement mechanism of biochar with graphene structure in anaerobic digestion: The bioavailability of trace elements and potential direct interspecies electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredych, M.; Bandosz, T.J. Mechanism of Ammonia Retention on Graphite Oxides: Role of Surface Chemistry and Structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 15596–15604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Dong, Q.; Yang, P.; Liu, H.; Ye, W.; Wu, D.; Peng, X. Evaluate of digestate-derived biochar to alleviate ammonia inhibition during long-term anaerobic digestion of food waste. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 137150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Chen, X.-H.; Mo, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-H.; He, M.-Y.; Li, Y.-W.; Feng, N.-X.; Katsoyiannis, A.; Cai, Q.-Y. Occurrence and dissipation mechanisms of organic pollutants during the composting of sewage sludge: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 328, 124847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linville, J.L.; Urgun-Demirtas, M.; Schoene, R.P.; Snyder, S.W. Producing Pipeline-Quality Biomethane via Anaerobic Digestion of Sludge Amended with Corn Stover Biochar with in-Situ CO2 Removal. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 300−309. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Yu, M.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, M.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y. A comprehensive review on food waste anaerobic digestion: Research updates and tendencies. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degreve, J.; Dewil, R. Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Yan, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Reduction of gibbs free energy and enhancement of methanosaeta by bicarbonate to promote anaerobic syntrophic butyrate oxidation. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 267, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Moe, C.L.; Null, C.; Raj, S.J.; Baker, K.K.; Robb, K.A.; Yakubu, H.; Ampofo, J.A.; Wellington, N.; Freeman, M.C.; et al. Multipathway Quantitative Assessment of Exposure to Fecal Contamination for Young Children in Low-Income Urban Environments in Accra, Ghana: The SaniPath Analytical Approach. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paritosh, K.; Vivekanand, V. Biochar enabled syntrophic action: Solid state anaerobic digestion of agricultural stubble for enhanced methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.R.; Adhikari, S.; Nam, H.; Sajib, S.K. Effect of bio-char on methane generation from glucose and aqueous phase of algae liquefaction using mixed anaerobic cultures. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 108, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Rotaru, A.-E.; Shrestha, P.M.; Malvankar, N.S.; Nevin, K.P.; Lovley, D.R. Promoting direct interspecies electron transfer with activated carbon. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8982–8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiarto, Y.; Sunyoto, N.M.S.; Zhu, M.; Jones, I.; Zhang, D. Effect of biochar addition on microbial community and methane production during anaerobic digestion of food wastes: The role of microbial in biochare. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124585. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; et al. Biochar accelerates methane production efficiency from baijiu wastewater: Some viewpoints considering direct interspecies electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yang, Q.; Yao, F.; Chen, S.; He, L.; Hou, K.; Pi, Z.; Yin, H.; Fu, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Evaluating the effect of biochar on masophilic anaerobic digestion of waste active sludge and microbial diversity. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 294, 122235. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.B.; Woodard, T.L.; Nevin, K.P.; Lovley, D.R. Enhancing syntrophic metabolism in up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket reactors with conductive carbon materials. Biresour. Technol. 2015, 191, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.N.; Li, B.; Patel, K.; Wang, L.B. A review of the processes, parameters, and optimization of anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anukam, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Naqvi, M.; Granström, K. A review of the chemistry of anaerobic digestion: Methods of accelerating and optimizing process efficiency. Processes 2019, 7, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schink, B. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomez Camacho, C.E.; Ruggeri, B. Syntrophic microorganisms interactions in anaerobic digestion (Ad): A critical review in the light of increase energy production. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 64, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, R.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhu, G. Syntrophy mechanism, microbial population, and process optimization for volatile fatty acids metabolism in anaerobic digestion. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.P.; Wolin, E.A.; Wolin, M.J.; Wolfe, R.S. Methanobacillus omelianskii, a symbiotic association of two species of bacteria. Archiv für Mikrobiologie 1967, 59, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stams, A.J.M.; Plugge, C.M. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.D. Enrichment of specific electro-active microorganisms and enchanchement of methane production by adding granular active carbon in anaerobic reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 205, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, F.J.; de Bok, F.A.M.; Tuan, D.D.; Stams, A.J.M.; Lettinga, G.; Field, J.A. Reduction of humic substances by halorespiring, sulphate-reducing and methanogenic microorganisms. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Salvador, A.F.; Pereira, L.; Madalena Alves, M. Methane Production and Conductive Materials: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10241–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, C.D.; Guiot, S.R. Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer in Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Adv. Biochem. Eng./Biotechnol. 2015, 151, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Summers, Z.M.; Fogarty, H.E.; Leang, C.; Franks, A.E.; Malvankar, N.S.; Lovley, D.R. Direct Exchange of Electrons Within Aggregates of an Evolved Syntrophic Coculture of Anaerobic Bacteria. Science 2010, 330, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, A.; Im, S.; Song, Y.-C.; Ahn, Y.; Kim, D.H. Enchanced anaerobic digestion by stimulating DIET reaction. Processes 2020, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Watanabe, K. Microbial interspecies electron transfer via electric currents through conductive minerals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10042–10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Zakaria, B.S.; Dhar, D.R. Enhanced methanogenic co-degradation of propionate and butyrate by anaerobic microbiome enriched on conductive carbon fibers. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 266, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Wan, J.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, S.; Luo, G. iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis reveals the pathways for methanation of propionate facilitated by magnetite. Water Res. 2017, 108, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Watanabe, K. Methanogenesis facilitated by electric syntrophy via (semi)conductive iron-oxide minerals. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, G.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, C. Role and potential of direct interspecies electron transfer in anaerobic digestion. Energies 2018, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüpfel, L.; Keiluweit, M.; Kleber, M.; Sander, M. Redox properites of plant biomass-derived black carbon (Biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 5601–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Pignatello, J.J.; Mitch, W.A. Role of black carbon electrical conductivity in mediating hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-treazine (RDX) transformation on carbon surfaces by sulfides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7129–7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapanagiotis, N.; Sterritt, R.; Lester, J.N. Heavy metals complexation in sludge amended soil: The role of organic matter in metal retention. Environ. Technol. 1991, 12, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.; Seghetta, M.; Mikkelsen, M.H.; Gyldenkaerne, S.; Becker, T.; Caro, D. Comparative life cycle assessment of biowaste to resource management systems—A Danish case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4050–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkdogan, M.K.; Kilcel, F.; Kara, K.; Tuncer, I.; Uygai, I. Heavy metals in soil, vegetables and fruits in the endemic upper gastrointestinal cancer region of Turkey. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2003, 13, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, D.; Feng, P.; Hao, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Municipal sewage sludge incineration and its air pollutioncontrol. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenzinger, K.; Drost, S.M.; Korthals, G.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Organic residue amendments to modulate greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural soils. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Ye, Z.; Yang, C. Effect of manganese oxide-modified biochar addition on methane production and heavy metal speciation during the anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 76, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Yang, X.; Gielen, G.; Bolan, N.; Ok, Y.S.; Niazi, N.K.; Xu, S.; Yuan, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effect of bamboo and rice straw biochars on the mobility and redistribution of heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn) in contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 186, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piippo, S.; Lauronen, M.; Postila, H. Greenhouse gas emissions from different sewage sludge treatment methods in north. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Huang, H.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y. Greenhouse gases emissions accounting for typical sewage sludge digestion with energy utilization and residue land application in China. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, J. Greenhouse gas emissions from different municipal solid waste management scenarios in China: Based on carbon and energy flow analysis. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, P.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Xiong, Z. Responses of N2O production pathways and related functional microbes to temperature across greenhouse vegetable field soils. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; Fang, N.; Dong, B. Life cycle assessment of sludge anaerobic digestion combined with land application treatment route: Greenhouse gas emission and reduction potential. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, H. Impacts of aeration and biochar addition on extracellular polymeric substances and microbial communities in constructed wetlands for low C/N wastewater treatment: Implications for clogging. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, E.M.; El-Bebany, A.A.F.; Alrumman, S.A.; Hesham, A.E.; Taher, M.A.; Fawy, K.F. Effects of different sewage sludge applications on heavy metal accumulation, growth and yield of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Int. J. Phytoremediation 2017, 19, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masebinu, S.O.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Muzenda, E.; Aboyade, A.O. A review of biochar properties and their roles in mitigating challenges with anaerobic digestion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Stephane, K.L.; Mayigue, C.; Sorel, C.-D.V.; Os´ee, M.; Derbetini Appolinaire, V. Potential assessment of biomethane fuel production from municipal sewage plant sludge: Kinetic modeling studies and techno-economic analysis. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.H.; Tao, L. Economic perspectives of biogas production via anaerobic digestion. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Sikora, J.; Oleksy-Gębczyk, A.; Wietecha, J.; Danielska, M. Energy properties of sewage sludge in biogas production-technical and economic aspects. Energies 2025, 18, 5662. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Chopra, A.K.; Kumar, A. A review on sewage sludge (Biosolids) a resource for sustainable agriculture. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2017, 2, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feedstock | Temperature Pyrolysis | The Highest Yield of Methane | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food waste | 550 °C | 65. 8 L/day | Biochar increased methane production by 23.8% | Zhang et al., 2025 [47] |

| Cedar wood, wheat straw, digestate, and municipal sludge | 400–950 °C | 417.79 ± 5.38 mL/g VS | Biochar produced at a lower temperature of 400 °C increased methane production by 40% | Vayena et al., 2024 [55] |

| Sawdust waste | 500–700 °C | 12.6–13.7 mL/day | Biochar pyrolyzed at 500 °C proved to be the most effective | Wang et al., 2020 [67] |

| Cornmeal leads | 500 °C | 66 g/L | Biochar enhanced methane production by up to 26.2% | Zhou et al., 2020 [61] |

| Corn straw, coconut shell, and sewage sludge | 400, 500, 600 °C | 218.45 ± 9.55 L per kg VS | Biochar derived from corn straw pyrolyzed at 600 °C proved to be the most effective | Zhang et al., 2019 [62] |

| Oil sludge | 500, 600, 700 °C | 143 mL/g VS | Biochar from oil sludge pyrolyzed at 600 °C was used; it showed the highest capacity and accumulative methane yield | Feng et al., 2023 [68] |

| Corn stover | 600 °C | 3.06 g/g TS | Biochar derived from corn stover pyrolyzed at 600 °C increased the methane yield by a range of 8.6–17.8% | Wei et al., 2020 [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leovac Maćerak, A.S.; Žmukić, D.S.; Duduković, N.S.; Slijepčević, N.S.; Kulić Mandić, A.Z.; Tomašević Pilipović, D.D.; Kerkez, Đ.V. Advances in Biochar-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion: Effects on Process Stability, Methanogenic Pathways, and Digestate Properties. Separations 2026, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010018

Leovac Maćerak AS, Žmukić DS, Duduković NS, Slijepčević NS, Kulić Mandić AZ, Tomašević Pilipović DD, Kerkez ĐV. Advances in Biochar-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion: Effects on Process Stability, Methanogenic Pathways, and Digestate Properties. Separations. 2026; 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeovac Maćerak, Anita S., Dragana S. Žmukić, Nataša S. Duduković, Nataša S. Slijepčević, Aleksandra Z. Kulić Mandić, Dragana D. Tomašević Pilipović, and Đurđa V. Kerkez. 2026. "Advances in Biochar-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion: Effects on Process Stability, Methanogenic Pathways, and Digestate Properties" Separations 13, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010018

APA StyleLeovac Maćerak, A. S., Žmukić, D. S., Duduković, N. S., Slijepčević, N. S., Kulić Mandić, A. Z., Tomašević Pilipović, D. D., & Kerkez, Đ. V. (2026). Advances in Biochar-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion: Effects on Process Stability, Methanogenic Pathways, and Digestate Properties. Separations, 13(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010018