Abstract

The hydrophobic region of semaglutide makes it prone to aggregation in aqueous solution, which leads to serious interception in microfiltration. The influences of pH and low concentrations of salts (NaCl, CH3COONa, Na2SO4 and (NH4)2SO4) on the particle size and zeta potential of semaglutide aggregates were studied in this work. The results showed pH could change the zeta potential on the semaglutide surface, but the impact on semaglutide dispersion was limited. When salts were introduced into aqueous solution, NaCl had a more significant dispersion effect on semaglutide than other salts. Under pH 2.5 or pH 8.0 conditions, the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl reduced the average particle size of semaglutide aggregates to below 70 nm. The permeability of semaglutide in microfiltration increased from 60% to 86% under optimized conditions with the PES membrane (0.22 μm), and the adsorption loss also reduced 40%. In addition, this study compared the HPLC detection precision of semaglutide samples prefiltered with different microfiltration filters. Some semaglutide was intercepted by various microfiltration filters, resulting in serious detection errors. When semaglutide was dissolved in the aqueous solution containing 0.01 mol/L NaCl with pH 2.5, the detection error was controlled within 1%.

1. Introduction

With the development and evolution of bioengineering technology, polypeptides have become widely used in the fields of medicine, food, cosmetics, etc. The separation and purification techniques of polypeptides have become a hot spot for research and application. Most functional peptides have special structural properties, and the separation and purification processes are difficult and complex. Semaglutide is one of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist analogues and has 94% structural homology with the naturally occurring GLP-1 [1,2,3,4]. The semaglutide molecule is composed of a 31-amino-acid peptide skeleton connected to fatty acid side chains, and its molecular weight is 4113.58 [5]. Semaglutide is widely used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and has significant advantages in lowering blood sugar, weight loss, and improving cardiovascular system function [6,7].

As a medicinal polypeptide, the purification process of semaglutide needs to achieve highly selective separation while maintaining its structural integrity and biological activity, thereby ensuring the high purity and high yield of the product [8,9]. Membrane separation technology operates under mild conditions and can effectively prevent the degradation or denaturation of polypeptides. It features low energy consumption, no pollution, high efficiency, sustainability, and easy operation and has been widely applied in the pharmaceutical industry through microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), etc. [10,11]. MF membranes with pore diameters ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 μm can achieve efficient separation under mild operating conditions (normal temperature and normal pressure). Its screening mechanism can effectively separate particulate matter, cell debris, organelles, colloids, and even pathogens in the liquid from polypeptides [12,13]. Swaminathan et al. [14] removed peptides from hydrolyzed protein solutions through a 0.1 µm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and concentrated phospholipids in the solution. Kongsinkaew et al. [15] successfully isolated a 4.1 kDa candidate cell-penetrating antimicrobial peptide (CAP) from other impurity proteins and pigments using a MF membrane with a pore size of 0.2 μm.

The accurate evaluation of polypeptide production and separation relies on precise analysis and detection. In high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, MF filters (such as 0.22 μm and 0.45 μm) often play a critical role in the sample preparation process. The main function of MF filters is to eliminate particulate matter, bacterial contaminants, and other impurities from samples, thereby preventing column fouling and detector contamination [16]. Therefore, the permeability of the polypeptide molecules through MF filters would directly affect the accuracy of the product concentration detection.

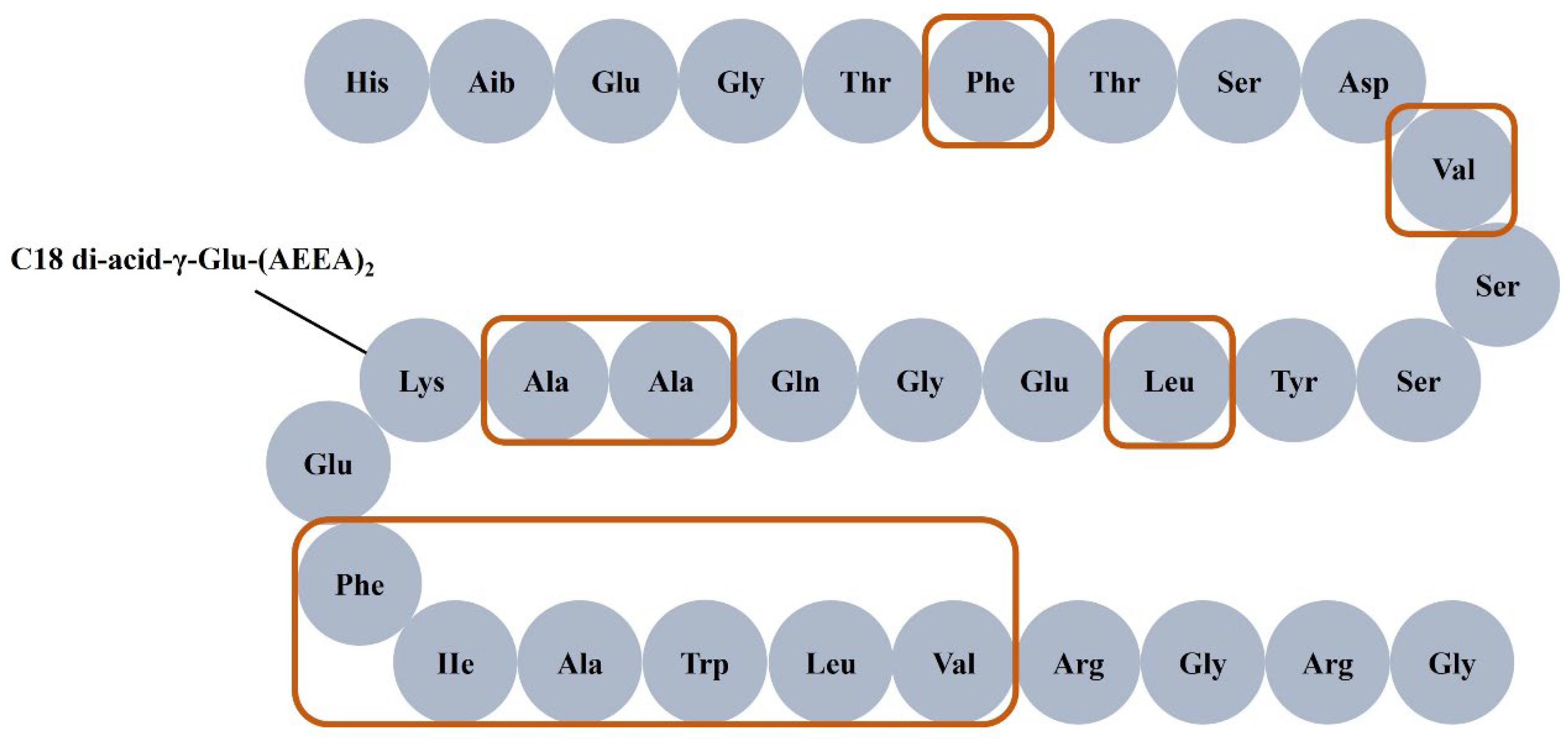

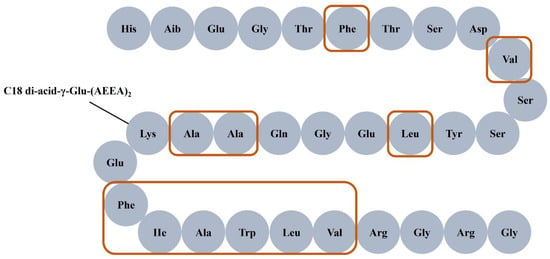

The characteristics of polypeptides, such as molecular structure or size, hydrophobicity, surface charge, and aggregation properties, directly affect the selectivity and recovery of membrane separation. It is worth noting that the peptide chain structure of semaglutide contains a strong hydrophobic region, consisting of 11 hydrophobic amino acids (as shown in Figure 1), which would stimulate the aggregation of semaglutide in the solution. Consequently, the aggregation behavior of semaglutide would lead to the retention or adsorption of the target product by the membrane in the separation and purification process, which results in a decrease in the selectivity of membrane separation and a reduction of product yield. The polypeptide aggregates are easily intercepted by MF membranes because these membranes are usually prepared from PVDF materials, which have strong hydrophobicity [17] and exhibit a strong adsorption effect on the hydrophobic biomacromolecules [18]. The solubility of proteins in aqueous systems is highly pH-dependent, reaching a minimum at the isoelectric point (pI) where the net surface charge is zero. This principle extends to polypeptides, as the solution pH directly governs the distribution of their net surface charge, thereby influencing electrostatic interactions and aggregation behavior. The charge characteristics on the surface of the membrane material could cause the electrostatic adsorption of semaglutide with opposite charges at certain pH values, which would cause a large amount of semaglutide to be retained or adsorption by the membrane. When salts are introduced into the solution, ions interact directly or indirectly with the surface of polypeptides. Ionic strength modulates the effective hydrodynamic volume of charged polypeptides by compressing the electrostatic interactions mediated by the electric double layer, thereby altering their aggregation states and solubility [19,20]. Fernández et al. [21] investigated the effect of ionic strength on peptides separated by polyethersulfone (PES) membranes. The effective size of the charged peptide (IDALNENK) decreased after adding 0.5 mol/L NaCl, and its permeability increased from 6.2% to 58.7%.

Figure 1.

Structure of semaglutide. The region within the frame represents hydrophobic amino acids.

Therefore, ionic strength and pH might improve the membrane separation performance of semaglutide and reduce separation loss. In this study, the effects of low-concentration salts and pH on the aggregation of semaglutide are investigated, to promote the application of membrane separation in polypeptide separation and purification. The selectivity and recovery of the membrane separation of semaglutide are compared in different dispersion states. In addition, the effect of the aggregation state of semaglutide on the sample prefiltration and the accuracy of HPLC detection is also discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Semaglutide (99.63%) was purchased from TAKELE Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Three different hollow-fiber MF membrane modules were used in this work. The first and the second membrane modules are PVDF membranes (0.5 m2) with a pore size of 0.22 μm and 0.45 μm (Tianjin MOTIMO Membrane Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). The third one is a PES membrane (0.3 m2), which has a pore size of 0.22 μm (OMEX, Huzhou, China). NaCl, Na2SO4, CH3COONa, (NH4)2SO4, and other chromatography-grade reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

In addition, the mixed cellulose (MCE) filters (pore size 2.5 μm) were purchased from Shanghai Xin Ya Purification Equipment Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). PES filters (pore sizes of 0.8 μm, 0.45 μm, and 0.22 μm) and PVDF filters (pore sizes of 0.8 μm and 0.45 μm) were purchased from Tianjin Navigator Lab Instrument Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). They were used in prefiltration for sample analysis by HPLC.

2.2. Microfiltration Separation of Semaglutide Solution

An aqueous solution of semaglutide with 500 mg/L was prepared with deionized water. Before MF separation, the membrane module was washed with deionized water until the effluent was about pH 7.0. The semaglutide solutions were adjusted to different pH levels for the separation. Then, MF was operated at 20 °C through a full circulation mode, with a feed flow rate of 29.26 L/h. The permeate and the retentate were returned to the initial feed solution, and the transmembrane pressure was controlled at 0.05 Mpa. Full circulation mode is an operational method that achieves the efficient concentration or separation of target solutes. This is done by continuously recycling the retentate back to the feed end to mix with the unfiltered feed liquid while simultaneously collecting the permeate. After a half-hour cycle, the sample and the velocity of permeate were analyzed and recorded. After the MF experiments, all the liquid was collected, and the MF membrane was backwashed with 0.8 L of deionized water.

Following each MF separation, the membrane was thoroughly washed with citric acid solution (10 g/L) and sodium hydroxide solution (2 g/L) to remove adsorbed polypeptides and salt residues from the membrane surface and pores. Finally, the membrane was rinsed with deionized water until the pH of the permeate reached 7.0. To evaluate the cleaning effectiveness, the initial water flux of the membrane was measured using deionized water under standard operation pressure. If the membrane flux, measured consecutively, remained above 97% of the initial water flux, the membrane performance was considered restored. The samples were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The strength of the interaction between the membrane and semaglutide was assessed by measuring the permeate flux (J) and the permeability of semaglutide under different conditions. Further analysis was conducted by calculating the adsorption of semaglutide by the MF membrane to distinguish whether pore blocking or surface adsorption was the dominant mechanism. The permeability of semaglutide (T) was calculated as shown in Equation (1):

where C0 is the concentration of semaglutide in the initial feed solution (mg/L); C1 is the concentration of semaglutide in the permeate (mg/L).

The adsorption of semaglutide by the MF membrane was determined by Equation (2):

where Q is the amount of semaglutide adsorbed per unit membrane area (mg/m2); C2 and C3 are the concentrations of semaglutide reflux and backwash liquor, respectively; V0, V2, and V3 are the volumes (L) of the feed solution, reflux, and backwash liquor, respectively; A is the effective membrane area (m2).

The permeate flux of MF membrane is expressed in Equation (3):

where J is the permeate flux of the MF membrane (L/m2·h); V is the volume of filtrate collected over time T (mL); A is the effective membrane area (m2); T is the MF time (min).

2.3. Investigation of the Effect of Low-Concentration Salts on the Aggregation of Semaglutide

The method for determining the aggregation state of semaglutide was modified based on the literature [22]. Specific salts (NaCl, CH3COONa, Na2SO4, and (NH4)2SO4) were selected to systematically compare the effects of cations (Na+, NH4+) and anions (Cl−, SO42−, CH3COO−) with different valences. Acetate or hydrochloride salts represent the predominant salt forms for most therapeutic peptides [23]. Sodium sulfate and ammonium sulfate are also commonly used inorganic salts for the salting-out separation of therapeutic peptides [24,25]. The concentration gradients was designed to span a range from low to high ionic strength to analyze the influence of inorganic salts on the aggregation state of semaglutide molecules. The semaglutide solution (500 mg/L) with the addition of different salts (NaCl, CH3COONa, Na2SO4, and (NH4)2SO4) was controlled in a certain range (0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, and 0.1 mol/L) and stirred for 30 min. It was then adjusted to different pH levels (2.0, 2.5, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0) by hydrochloric acid solution (2 mol/L) or sodium hydroxide solution (2 mol/L). Further, solutions were analyzed by a laser particle size analyzer to investigate the aggregation of semaglutide in solution and surface charge properties (zeta potential).

2.4. Investigation of the Effect of Salt Addition on Microfiltration of the Semaglutide Solution

According to the results of Section 2.3, the proper salt was added to the semaglutide solution at the appropriate pH level, which could promote the dispersion of semaglutide and reduce the particle size of aggregates. Then, MF was carried out through a full-circulation mode to further investigate the permeability of semaglutide. The MF operation was the same as that described in Section 2.2.

2.5. Investigation of the Effect of Semaglutide Aggregation on HPLC Analysis

A semaglutide solution (400 mg/L) was prepared, and the pH was adjusted to different values. The HPLC analysis results of the semaglutide solutions with or without the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl were compared after filtration with different filters. The MCE membrane was uncharged or weakly charged and the pore size was 2.5 μm, so the detection results of the semaglutide solution filtrated by MCE filters was used as the standard control.

2.6. Analytical Methods

2.6.1. Characterization of the Aggregation State of Semaglutide

A sample of 10 mL was taken for particle size testing with the Zetasizer Lab system (Zetasizer Lab-Blue, Malvern Panalytical, Worcester, UK). Prior to introduction into the 10 × 10 mm plastic particle size cuvette, each sample was thoroughly vortexed to ensure the complete dispersion of particles and to prevent aggregation. Instrument parameters were configured based on the sample characteristics. The dispersant was deionized water, the temperature was set at 25 °C, and the refractive index of the dispersing medium was 1.45–1.55. The detector was subsequently initiated, and data acquisition was carried out by the instrument’s embedded software. Through mathematical model fitting, particle size distribution curves and statistical parameters such as D10, D50, D90, and the polydispersity index were automatically generated. The mean particle size (D50) was utilized to describe the overall dimensions of the particles and for subsequent analysis. Similarly, the Zetasizer Lab system was also used to measure the surface charge properties of aggregates. The parameters were set as follows: dispersant as water, temperature 25 °C, laser wavelength 633 nm, electric field strength 100 V/cm, etc. Upon instrument initiation, the zeta potential was automatically calculated, and the results were generated to analyze the surface charge characteristics of semaglutide. To ensure the reliability of the results, the same sample was analyzed three times.

2.6.2. Concentration Detection of Semaglutide by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

The samples were analyzed using an HPLC system (DIONEX UltiMate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a WondaSil C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) at a column temperature of 30 °C. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, and the sample injection volume was 20 μL. The detection wavelength was 215 nm. The procedure was carried out using a mobile phase A containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (v/v), with acetonitrile as the mobile phase B. The method was as follows: a linear gradient from 40% to 55% B for 20 min, from 55% to 40% B for 1 min, and isocratic elution at 40% B for 14 min. The total analysis time for each sample was 35 min. All the standard concentration samples of semaglutide in the series were prepared with ultrapure water and filtered through a 2.5 μm MCE filter before detection. A standard concentration curve was plotted based on the chromatographic peak area and the corresponding concentration of the semaglutide standard samples.

2.6.3. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy Analysis

The CD spectroscopy analysis was performed according to the referenced literature [26]. A 400 mg/L semaglutide solution was analyzed under the addition of different 0.01 mol/L salts. A salt solution of the same concentration served as the control. CD spectra of the samples were recorded from 190 to 400 nm using a CD spectrometer (JASCO J-1500, JASCO, Hachioji, Japan).

2.6.4. Statistical Analysis

All results were measured in triplicate, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. When p < 0.05, significant differences were considered.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microfiltration Separation Performance of Aqueous Semaglutide Solutions

Semaglutide exhibits an isoelectric point (pI) within the range of 4.2 to 4.8 [27]. When the pH is above the isoelectric point (pI), semaglutide carries a net negative charge. Conversely, it bears a net positive charge when the pH is below the pI. As the pH approaches the pI, electrostatic repulsion is progressively weakened [28]. The preliminary experiment revealed that semaglutide solutions appeared turbid, and some semaglutide precipitated at both pH 4.0 and 5.0, irrespective of the presence or absence of salts. Consequently, hydrophobic interactions become dominant and drive the aggregation process. Therefore, semaglutide carried a net positive charge at pH 2.5 in this study. PVDF membranes possess a positive charge [29], but the semaglutide could not permeate through the PVDF membrane in MF whether the membrane pore size was 0.22 μm or 0.45 μm (Table 1). Mochizuki et al. [30] revealed that this phenomenon not only originates from the sieving effect of the pore structure but also is closely associated with significant adsorption interactions between the membrane surface and peptide molecules. Semaglutide is a peptide containing a highly hydrophobic structure. The strong hydrophobic interaction would result in a large adsorption of semaglutide on the PVDF membrane surface and change the selectivity of MF. In this experiment, the adsorption capacity of the 0.22 μm PVDF membrane for semaglutide even achieved 700 mg/m2, which indicated PVDF membranes were inappropriate in this separation process. This phenomenon was consistent with the adsorption behavior of hydrophobic membrane materials on peptides reported in the literature [31], which further validated the critical influence of the surface properties of membrane materials on the separation of biomolecules. Under pH 8.0 conditions, the separation performances of the PVDF membranes with different pore sizes for semaglutide were further investigated using the same methodology. The results indicated that both membranes had almost no permeation flux. This phenomenon was attributed to the synergistic effects of pronounced hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic interactions between the membrane material and semaglutide molecules. The hydrophobic PVDF membranes tended to adsorb the hydrophobic domains of semaglutide. Simultaneously, under alkaline pH conditions, semaglutide molecules carried a net negative charge. Thus, electrostatic adsorption between the positively charged PVDF and semaglutide occurred. The combination effects led to complete retention of semaglutide molecules by the MF membranes, preventing transmembrane mass transfer.

Table 1.

Effect of microfiltration membranes with different pore sizes and materials on the separation performance of semaglutide aqueous solution.

PES membranes carry negative charges [32], and they are more hydrophilic than PVDF. In contrast, semaglutide carried a negative charge at pH 8.0, so there was electrostatic repulsion with the membrane surface, which was unfavorable for the adsorption of peptides on the membrane. A 0.22 μm PES membrane exhibited a 56.15% lower adsorption of semaglutide than a PVDF membrane of comparable pore size. However, the semaglutide permeability of this PES membrane was only 60% (Table 1), demonstrating low separation selectivity. Particle size analysis results showed that the average particle size of semaglutide in the aqueous solution was 338 nm (Table 2), significantly larger than the pore size of the PES membrane. These results suggested that semaglutide was in a state of aggregation in the aqueous solution, which would lead to serious interception by MF. This study further investigated the effect of electrostatic interactions on the separation of semaglutide with PES MF membranes by comparing its separation performance at pH 2.5. When semaglutide molecules carried a positive charge (pH 2.5), the permeability of the PES membrane was only 25.98%, approximately 57% lower than that under alkaline conditions (Table 1), while the adsorption capacity increased by about a factor of 1.2. Thi suggested that the inherent negative charge of the PES membrane and the positively charged peptide molecules generated an electrostatic attraction at pH 2.5. Combined with the hydrophobic interactions between them, this synergy led to significant loss of semaglutide during the separation process. Therefore, enhancing the dispersibility of semaglutide in aqueous solution and regulation of both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between the peptide and the membrane are critical strategies for improving the permeability of semaglutide molecules during MF.

Table 2.

Relationship between average particle size of semaglutide and different pH and salt concentrations.

3.2. Effect of pH and Salt Concentration on the Aggregation State of Semaglutide

It has been shown that the introduction of salt ions can modulate the surface properties of protein or polypeptide molecules by altering the hydration layer through dual mechanisms (electrostatic screening and specific ion effects). This modulation consequently influences their conformational stability and solubilization behavior [33]. Sousa et al. [22] investigated the effects of three salts on the solubility of egg yolk and plasma egg yolk. The results showed that NaCl acted as an excellent solubility promoter for both protein species. By comparing the optimization conditions under different pH conditions, it was found the solubility of egg yolk could reach 83 g/100 g at pH 10.0, and the solubility of plasma egg yolk could achieve 74 g/100 g.

As an amphipathic molecule, the physicochemical properties of semaglutide should be susceptible to the ionic environment of the solution. In view of the above mechanism, the present study was carried out to investigate the effect patterns of different types and concentrations of different salts on the particle size distribution and surface zeta potential of semaglutide aggregates. The results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationship between the zeta potential of semaglutide and different pH and salt concentrations.

Experimental results showed that semaglutide was highly prone to form aggregates in aqueous solution at room temperature. According to laser particle size analyzer measurements, the average diameter was determined to be 237–615 nm, which prevented semaglutide from passing through the MF membrane. As the pH of the solution changed from acidic to alkaline, the zeta potential on the surface of semaglutide gradually shifted from a positive charge to negative charge (Table 3). When the absolute value of the zeta potential on semaglutide surface decreased, the electrostatic repulsion effect was weakened, causing peptides to easily aggregate and the size of the polymer to increase, such as at pH 2.5 and pH 7.0.

Table 2 demonstrates that the NaCl concentration in solution could affect the aggregation propensity of semaglutide at certain pH levels. The binding of chloride ions to semaglutide in its charged state might increase the net negative charge of the peptide, enhancing the electrostatic repulsion between semaglutide molecules and consequently strengthening their hydration capacity. The introduction of low-concentration NaCl (0.01–0.02 mol/L) effectively reduced the semaglutide aggregate size to approximately 65 to 85 nm while maintaining a high zeta potential (40–43 mV) at pH 2.5, demonstrating excellent colloidal dispersion stability. Compared to the control group without salt added, the average particle size of semaglutide aggregates decreased by approximately 82 to 87%. Wu et al. [34] reported that as salt concentration increases, the shielding of the protein surface charges lead to compression of the electric double layer, thereby weakening the electrostatic repulsion between charged molecules. Table 3 shows there was a sharp decline in zeta potential (below 4.5 mV) when NaCl concentration reached or exceeded 0.05 mol/L at pH 2.5. The electrostatic repulsion between peptide molecules was consequently reduced, with the average particle size exceeding 630 nm, ultimately leading to particle reaggregation with visible precipitation. Notably, at pH 6.5, the negatively charged semaglutide achieved a reduced particle size of 100 nm with 0.02 mol/L NaCl, and the zeta potential also decreased from −13.8 mV to −38.7 mV. With further increases in NaCl concentration, the particle size showed significant regrowth, while the absolute zeta potential value decreased. The higher concentration of sodium ions might neutralize the negative charges on the surface of semaglutide, resulting in a decrease in its electronegativity; when the intermolecular hydrophobic interactions are enhanced, this can lead to more aggregation. However, NaCl addition failed to significantly improve semaglutide dispersion within the pH 7.0 to 7.5 range, with mean particle size remaining above 350 nm. Concurrently, zeta potential analysis indicated poor colloidal stability, suggesting NaCl introduction may paradoxically promote peptide aggregation under these conditions.

Negatively charged semaglutide was effective dispersed by 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 8.0. The system achieved a mean particle size of 60 nm while maintaining high charge stability (−47.7 mV). Compared to the control, this semaglutide aggregate diameter decreased 83%. Therefore, low concentrations of sodium chloride played a significant role in modulating the aggregation state of semaglutide in aqueous solution. However, when the concentration of NaCl was further increased, the absolute value of the zeta potential significantly decreased, which suggests that the negative charge on the surface of the peptide molecules decreased. This was not conducive to the dispersion of semaglutide molecules, with the average size of aggregate again increasing to 453–553 nm. These results suggest that the aggregation behavior of semaglutide was co-regulated by electrostatic and salt effects.

Using the analogous method, we investigated the effects of CH3COONa, Na2SO4, and (NH4)2SO4 on semaglutide aggregation across pH 2.0–8.0. Low concentrations of CH3COONa could not change the aggregation of semaglutide in aqueous solution; the average particle size of aggregates still ranged from 250 nm to 660 nm (Table 2). This phenomenon may be caused by the conformational changes induced by the binding of CH3COO− to the hydrophobic domains of the peptide [35], ultimately promoting the aggregation of semaglutide molecules into complexes. The aforementioned changes could expose more hydrophobic regions of the peptide, thereby promoting the aggregation of semaglutide molecules via hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic shielding effects.

The introduction of Na2SO4 exhibited a pH-dependent influence on the aggregation of semaglutide. When semaglutide carried a net positive charge (pH 2.5), the addition of 0.01 mol/L Na2SO4 promoted the dispersion of semaglutide aggregates, reducing the average particle size to 140 nm, a decrease of over 77% compared to the size observed at pH 7.0 without Na2SO4. At the same time, the high zeta potential value (+32 mV) indicated electrostatic repulsion was increased. However, within the pH range of 6.5–8.0, semaglutide aggregates maintained a size of 400–600 nm, with low absolute zeta potential values (Table 2 and Table 3). The dissociation of Na2SO4 introduced Na+ and SO42− ions into the aqueous solution, which led to an increase in ionic strength. Compared to the same amount of monovalent salt, the dissociation of Na2SO4 generates more sodium ions and divalent ions, which can result in stronger ionic strength. This enhances the electrostatic shielding effect and compresses the electrical double layer surrounding the peptide molecules, weakening the electrostatic repulsion between charged groups and promoting the formation of semaglutide aggregates.

It was noteworthy that (NH4)2SO4 exhibited significant regulatory effects on aggregation under acidic conditions. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, the addition of low-concentration (NH4)2SO4 could reduce aggregate size if the zeta potential of the semaglutide surface did not decrease to the lowest level. Moreover, 0.1 mol/L (NH4)2SO4 reduced the average particle size of semaglutide aggregates in solution to 100 nm at pH 2.5, representing a 79% reduction compared to the control without (NH4)2SO4. A high zeta potential of 37 mV was maintained, which was 4.6 times that of the control (8.06 mV). This phenomenon might be attributed to specific interactions between ammonium ions and the polypeptide molecules [35]; the introduction of ammonium ion could weaken hydrophobic interactions among polypeptide molecules, thereby further suppressing aggregate formation. Nevertheless, the dispersion efficacy of (NH4)2SO4 decreased progressively when the pH shifted to the neutral or alkaline range. Concurrently, the consistently low absolute zeta potential values indicated gradually decreasing solution stability and weakened intermolecular electrostatic repulsion, ultimately resulting in aggregate sizes remaining within the 400–600 nm range. Noro et al. [36] pointed out that, according to the extended law of corresponding states, a reduction in interparticle attractive interactions or an enhancement of repulsive interactions could improve dissolution capacity. The findings of this study were consistent with the conclusions mentioned above.

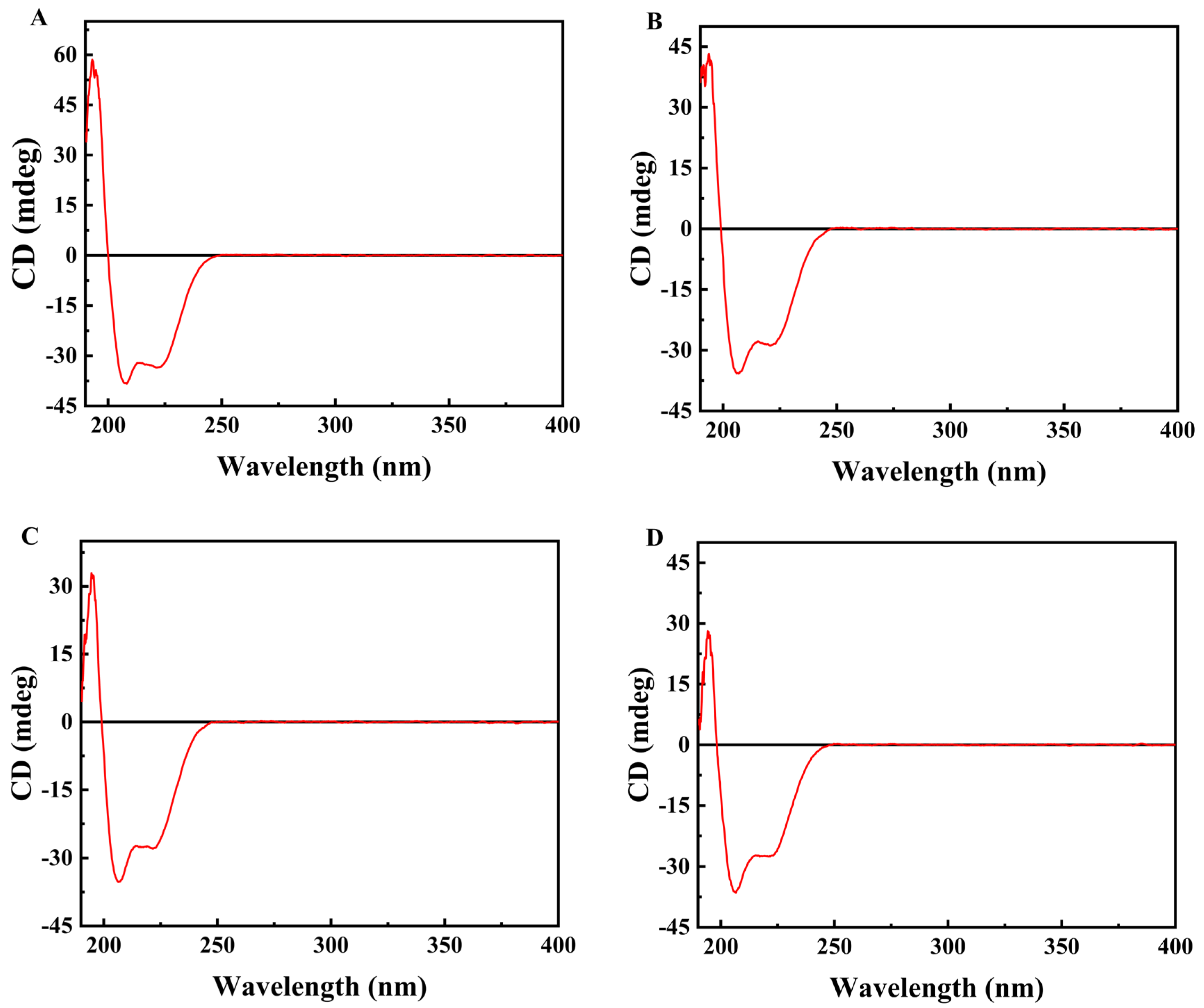

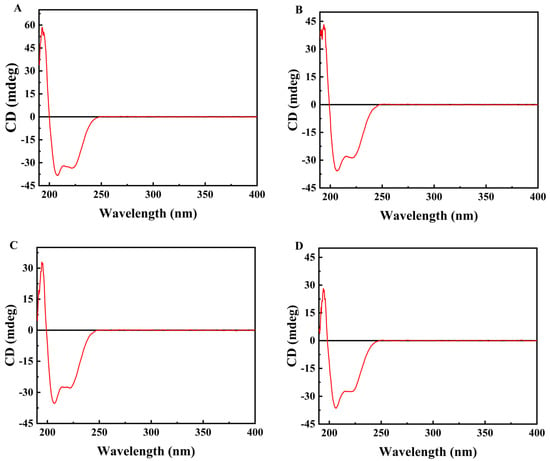

The literature has reported that semaglutide possesses an inherent α-helical structural domain within its molecular conformation [37]. This study employed circular dichroism spectroscopy to further verify the effects of different salt ions at identical concentrations (0.01 mol/L) on the dispersion behavior of semaglutide. The results indicated that the CD spectrum of semaglutide displayed characteristic peaks of a typical α-helical structure in the presence of salt ions (Figure 2). They manifested as distinct negative peaks (ellipticity minima) at wavelengths of 208 nm and 222 nm, along with a positive peak near 194 nm. In CD spectroscopy, more negative characteristic peaks of the α-helix at 222 nm and 208 nm (larger negative ellipticity values) signified a more regular and stable helical conformation. Therefore, the hydrophobic core of the polypeptide molecule becomes more fully embedded within the helical structure, thereby minimizing its exposure to the solvent and reducing the likelihood of nonspecific hydrophobic interactions [38]. Comparative analysis revealed that the interaction between NaCl and semaglutide resulted in superior helical characteristic signals in the CD spectrum compared to other small molecule salts. This result indicated that NaCl more effectively stabilized the native helical conformation of semaglutide and inhibited nonspecific aggregation. The aforementioned results were consistent with the characterization of solution dispersibility (particle size).

Figure 2.

Circular dichroism spectra of semaglutide solutions under different salt conditions at identical concentrations (0.01 mol/L): (A) semaglutide–NaCl mixed solution; (B) semaglutide–CH3COONa mixed solution; (C) semaglutid–Na2SO4 mixed solution; (D) semaglutide–(NH4)2SO4 mixed solution.

According to these results, the addition of certain salts in low concentrations under certain pH conditions could improve the dispersion degree of semaglutide in aqueous solution and substantially reduced the average particle size of semaglutide aggregates, which is conducive to the enhancement of the MF permeability of semaglutide and the reduction of semaglutide loss during the separation process. However, when the salt ion concentration exceeded a critical level, the shielding effect of salt ions on surface charges became dominant. This led to compression of the electric double layer surrounding the charged solutes (evidenced by a decrease in zeta potential), weakened the electrostatic repulsion between semaglutide molecules, and subsequently induced aggregation, thereby increasing mass transfer resistance. In this study, the optimal conditions were achieved when the pH of the semaglutide aqueous solution was 2.5 or 8.0 and the concentration of NaCl was 0.01 mol/L.

3.3. Effect of Salts on the Microfiltration Membrane Separation Performance of Semaglutide

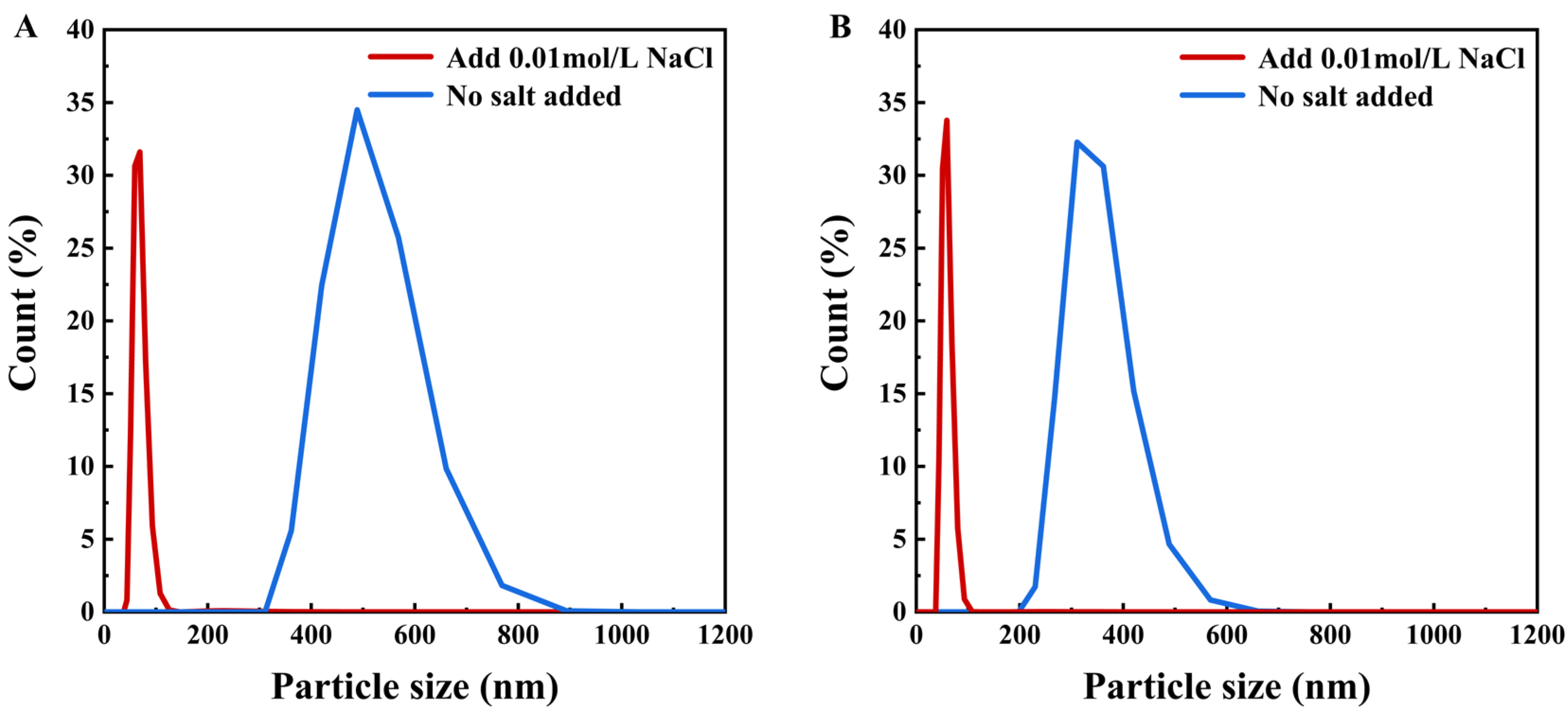

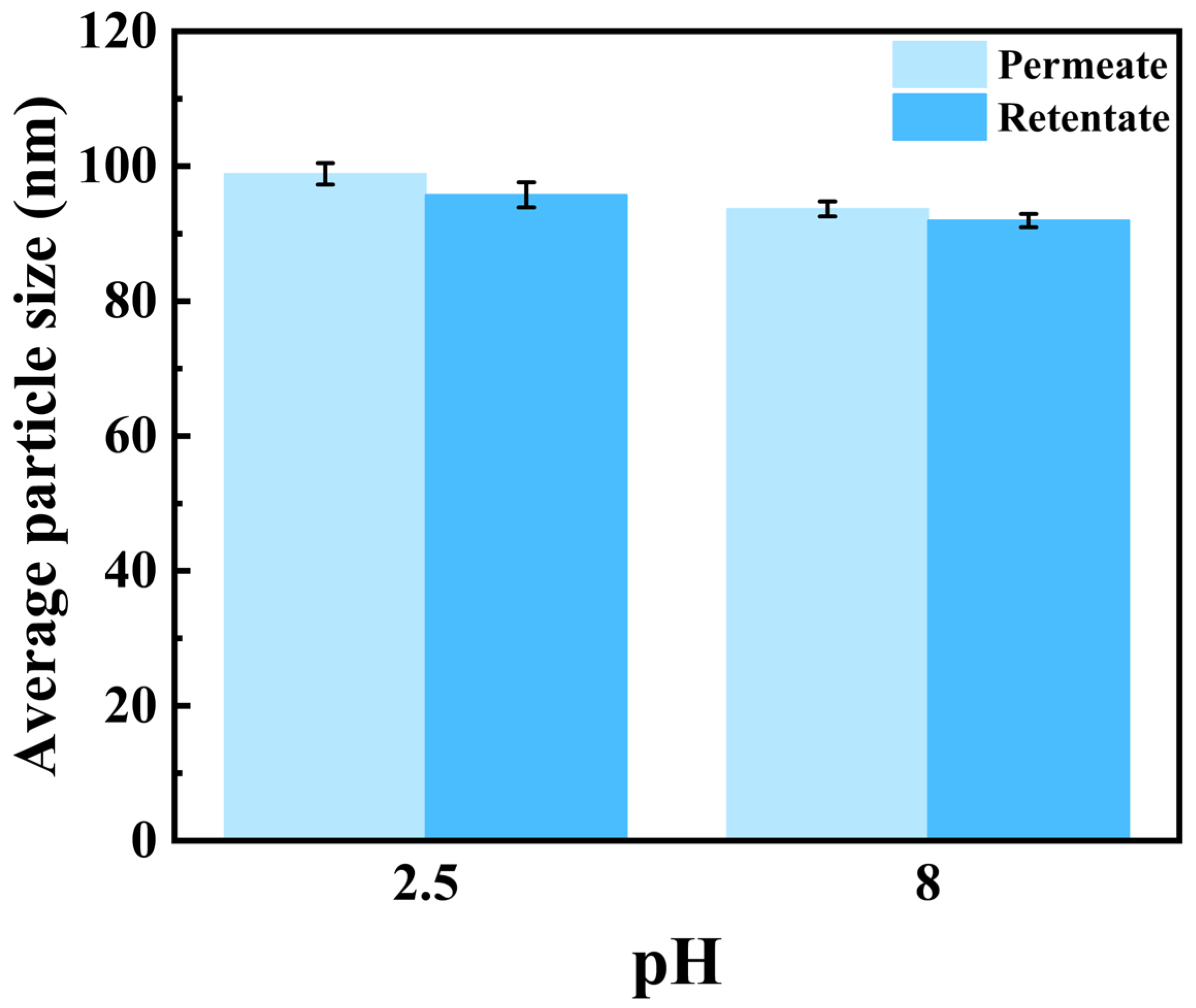

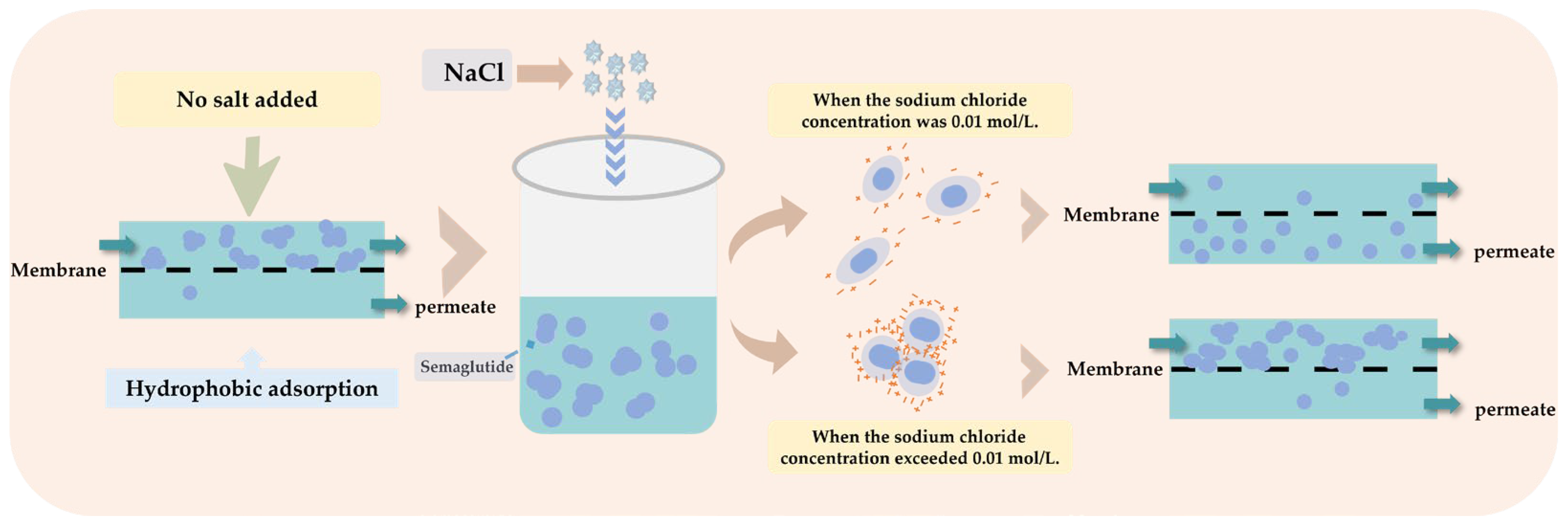

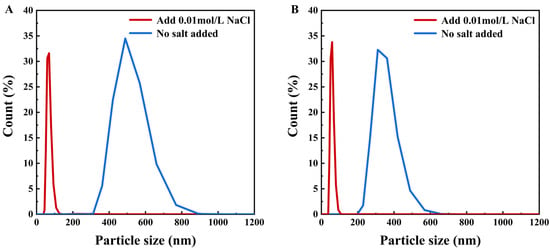

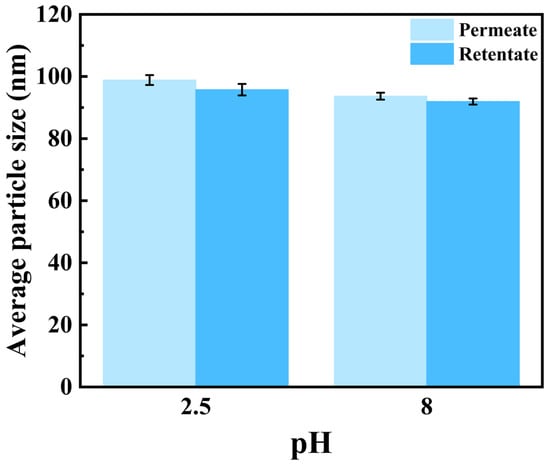

The particle size distribution of semaglutide at pH 2.5 and 8.0 is shown in Figure 3A; the average particle size of semaglutide ranged from 300 to 500 nm without the addition of NaCl. The particle size was significantly larger than the pore size of the 0.22 μm PVDF membrane; it prevented semaglutide from passing through the membrane. At pH 2.5 and with the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl, the average size of semaglutide was reduced to less than 100 nm. The membrane flux was increased from 25 L/(m2·h) (Table 1) to 33.9 L/(m2·h) (Table 4). However, the hydrophobic adsorption between PVDF and semaglutide resulted in a persistent membrane adsorption capacity of 532 mg/m2 for semaglutide, and the MF permeability of semaglutide only achieved 20% (Table 4). Similar results were observed when the 0.45 μm PVDF membrane was used. Additionally, semaglutide carried a negative charge at pH 8.0, whereas the PVDF membrane possessed an inherent positive surface charge, giving rise to specific electrostatic adsorption interactions between these two components. As shown in Figure 3B, the particle size of semaglutide could be reduced to approximately 60 nm at pH 8.0 with the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl. However, due to electrostatic attraction, semaglutide could not permeate through the 0.22 μm PVDF membrane, and the adsorption of semaglutide was as high as 696 mg/m2. Even using the 0.45 μm PVDF membrane at pH 8.0, the permeability of semaglutide was only 10.32%. As shown in Figure 4, whether at pH 2.5 or pH 8.0, the average particle sizes of semaglutide in both the permeate and retentate of the 0.45 μm PVDF membranes were below 100 nm, which were significantly smaller than the membrane pores. These results indicate the dispersion of semaglutide did not change during the MF process, and the extremely low permeability was due to hydrophobic adsorption or electrostatic adsorption. Therefore, the interaction between semaglutide and the membrane surface resulted in the PVDF membrane being unsuitable for the separation of semaglutide.

Figure 3.

Effect of low concentration of NaCl (0.01 mol/L) on the particle size distribution of semaglutide at different pH levels: (A) particle size distribution of semaglutide in solution before and after adding 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 2.5; (B) particle size distribution of semaglutide in solution before and after adding 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 8.0.

Table 4.

Effect of NaCl on the performance of microfiltration membranes with different pore sizes and materials on the separation of semaglutide aqueous solution.

Figure 4.

The average particle size (D50) of semaglutide in the permeate and retentate of MF using a 0.45 μm PVDF membrane at pH 2.5 and pH 8.0 with the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl.

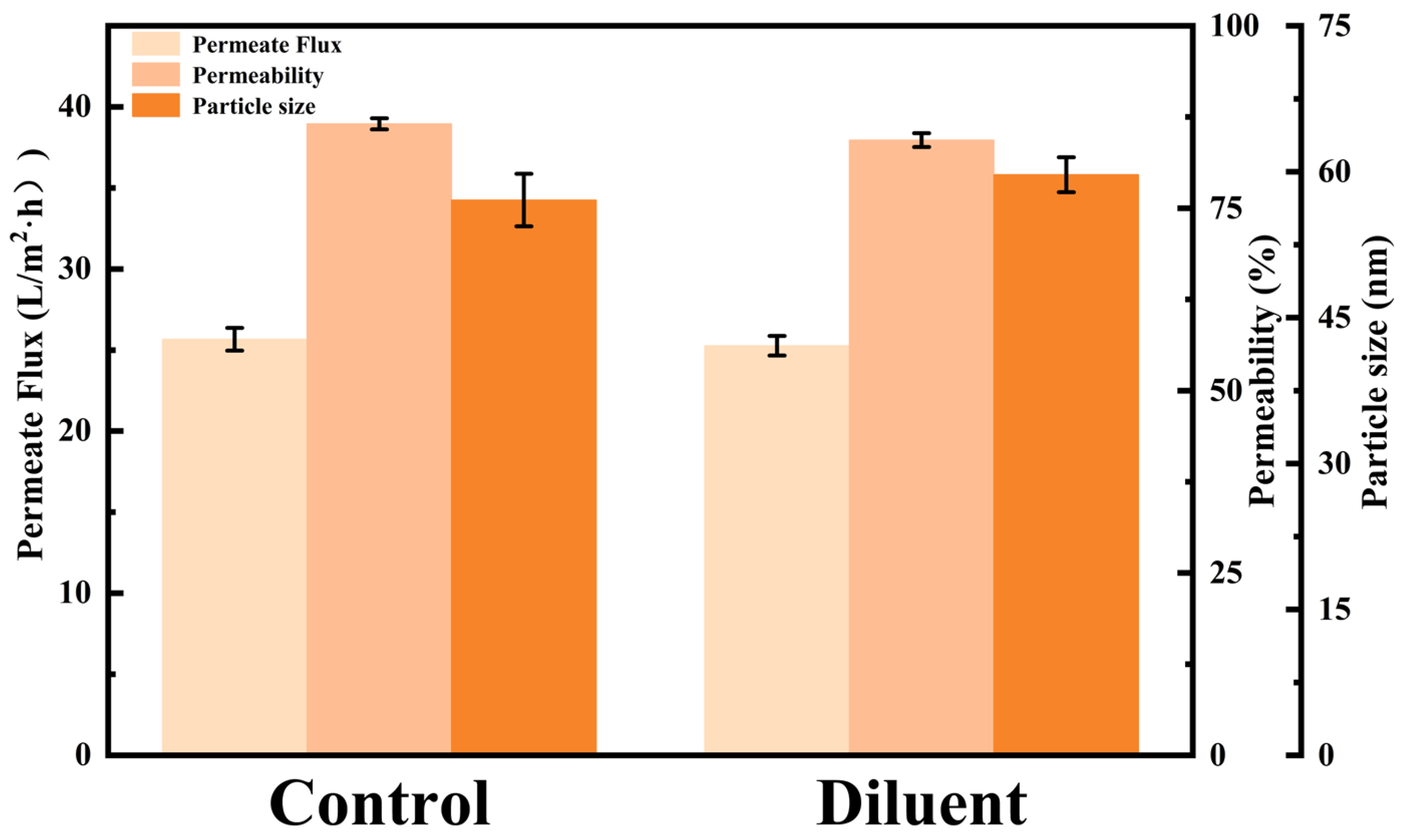

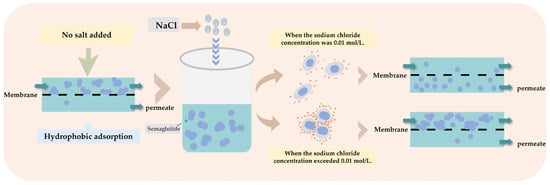

In comparison, the PES membrane exhibited superior separation performance for semaglutide owing to its weaker hydrophobic characteristics. The separation performance of semaglutide was significantly enhanced at pH 8.0 with the addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl; the permeability was increased to more than 86% (Table 4), and the membrane adsorption loss of semaglutide was reduced by 40%. This optimization effect was mainly attributed to the negative charge of semaglutide under alkaline conditions, and the electrostatic repulsion between semaglutide and the membrane material was enhanced. In contrast, electrostatic attraction dominated at pH 2.5. To investigate the effect of salt addition on MF separation performance, this study further examined the separation efficiency following the introduction of 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 2.5. The results demonstrated that the MF permeability increased from 25.98% to 40.22% after salt addition, accompanied by an approximately 25.33% reduction in adsorption loss. These results indicate that the addition of an appropriate amount of NaCl effectively suppressed the aggregation behavior of semaglutide (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of salt concentration in regulating semaglutide aggregation.

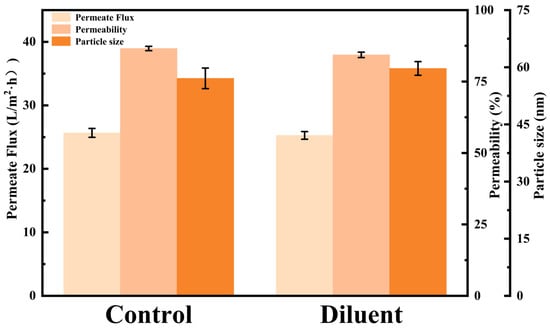

The aggregation state of peptides is a key parameter in determining the efficiency of membrane filtration. The formation of aggregates and their interaction with the membrane directly impact the transmembrane flux and the selective permeability of target products [39,40]. To further investigate the reversibility of the aggregation phenomenon, a semaglutide solution with a concentration of 500 mg/L, having a pH of 8.0, and containing 0.02 mol/L NaCl was prepared to induce aggregation. The average particle size of semaglutide was approximately 460 nm at this point. Subsequently, this solution was subjected to an equal-volume dilution, reducing the NaCl concentration to 0.01 mol/L. Finally, the diluted solution was subjected to an MF experiment using the 0.22 μm PES membrane. The diluted solution was then compared in parallel with a control solution (250 mg/L semaglutide, pH 8.0, 0.01 mol/L NaCl). A systematic comparison of the changes in permeate flux and semaglutide permeability was conducted to evaluate the stability of the aggregates and their influence on filtration performance. As shown in Figure 6, the particle size of semaglutide in the diluted sample decreased significantly, from 460 nm before dilution to around 60 nm, which was comparable to that of the control solution (57 nm). The result indicated that reducing the ionic strength attenuated the salt-ion shielding of peptide surface charges. This effectively restored the electrostatic repulsion between semaglutide molecules, thereby inducing the dispersion of aggregates. The experimental data showed that the MF permeate flux of the high-salt diluted solution and semaglutide permeability still achieved 25.27 L/m2·h and 84.33%, which were almost the same as the control (Figure 6). These results suggest that the significant reduction in the particle size of semaglutide in the solution decreased the physical clogging of membrane pores by aggregates, consequently leading to the increase of membrane flux and permeability. The semaglutide aggregation observed under these experimental conditions was primarily governed by reversible physical interactions. Specifically, electrostatic screening played the dominant role, as opposed to irreversible chemical denaturation.

Figure 6.

The influence of dilution on the particle size (D50) of semaglutide and the microfiltration performance.

In summary, the separation selectivity of semaglutide was significantly enhanced by regulating the solution and membrane material, demonstrating the possibility for applying MF technology to its separation and purification.

3.4. Effect of MF Filters on the Detection Precision of Semaglutide by HPLC

The MF filter plays a critical role in ensuring the precision of liquid chromatography detection. In the sample preparation process for macromolecular peptides, the optimization of filtration conditions, including membrane material and pore size selection, can significantly increase recovery and data reliability. The present study investigated the effects of membrane materials and pore sizes on the detected concentration of semaglutide under varying pH conditions and ionic strengths. With its characteristic non-charged nature and appropriate hydrophilic properties, MCE shows negligible nonspecific adsorption behavior when filtering polypeptide samples [41]. Therefore, a 2.5 μm MCE filter was selected as the control, while five additional MF filters with distinct physicochemical characteristics (including pore size, material composition, surface charge properties, and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity profiles) were employed as the experimental groups. The detection results for 400 mg/L semaglutide are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Effect of MF filter composition and porosity on the detection precision in semaglutide HPLC quantification.

As shown in Table 5, the 2.5 μm MCE filter exhibited favorable stability for the detection of semaglutide at pH 2.5, 6.86, and 8.0, the detection errors were all below 0.3%. At pH 2.5, the detection data demonstrated that the 0.8 μm PES filter exhibited excellent accuracy under acidic conditions. The detection error increased to 1.95% after passing through the 0.45 μm PES filter. However, only 366.3 mg/L semaglutide was detected after passing through the 0.22 μm PES filter due to its reduced pore size. The detection data of PVDF filters were lower than 390 mg/L, although their pore sizes were 0.45 μm and 0.8 μm for hydrophobic adsorption between semaglutide and PVDF material. When the pH was 6.86 and 8.0, the net charge on the surface of the semaglutide polypeptide was negative. The electrostatic incorporation loss of semaglutide increased when samples were pre-filtrated by PVDF filter. Even using the 0.8 μm PVDF filter, the lowest detection error also exceeded 4.3%. On the contrary, most PES filters demonstrated excellent accuracy, except for the 0.22 μm filter. The pattern of the influence of MF filters on the accuracy of HPLC detection was also similar to that observed at pH 6 and pH 8. Since semaglutide aggregated together in the aqueous solution and the average size of the aggregate was larger than 230 nm, the 0.22 μm PES filter was unsuitable for pre-filtration before the HPLC quantitative detection.

Under the conditions of pH 2.5 with 0.01 mol/L NaCl, the detection errors of samples pre-filtrated by various MF filters were all below 1%, including PVDF filters. Compared to the same condition without 0.01 mol/L NaCl, the detection error of the 0.22 μm PES filters was only 0.25%, which was far below the control (8.43%). The addition of 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 8.0 also improved the detection accuracy with most MF filters, except for the 0.45 μm PES filter. Although semaglutide carried a negative charge under these conditions, the PVDF filter (0.8 μm) exhibited reduced detection error, reaching a minimum of only 0.95%. Furthermore, even with the relatively small pore size (0.22 μm) of the PES filters, the detection error was still within 1%. Appropriate pH and ionic strength could enable precise HPLC quantitative detection of semaglutide concentration in samples pre-filtrated by MF filters.

4. Conclusions

Semaglutide exists in the form of aggregates in aqueous solution, which is not conducive to membrane separation. This study found adding 0.01 mol/L NaCl at pH 2.5 or pH 8.0 could promote the dispersion of semaglutide in water. The average particle size of the aggregates was below 70 nm, which was more than 80% lower than the control. Under optimized conditions, the PES membrane exhibited excellent MF performance compared to the PVDF membrane. The permeability of semaglutide increased from 60% to 86%, and the adsorption loss decreased by 40%. Furthermore, the HPLC detection error of semaglutide concentration resulting from MF filters could be significantly reduced by regulating the pH and adding a low concentration of NaCl. Even when the 0.22 μm PES filter was used for pre-filtration, the detection error was also controlled within 1%, which improved the detection accuracy of HPLC. These results would be beneficial for promoting the application of membrane separation technology in the separation and detection of semaglutide or other polypeptides.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, the membrane separation experiments were only carried out on a laboratory-scale setup. Secondly, the research primarily focused on the effects of several representative salts at a relatively low range of ionic strength. However, ion-polypeptide interactions are highly specific and depend on the ion type, valence, and concentration as well as the unique surface charge distribution and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of the polypeptides. Therefore, further research should explore the interactions between pharmaceutical polypeptides and inorganic salts within a wider range of salt types and ionic strength levels.

Author Contributions

L.D.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Y.Y.: Data curation, Investigation. H.W.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review and editing. X.D.: Data curation, Investigation. M.J.: Resources, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number 2021YFC2103902).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sorli, C.; Harashima, S.I.; Tsoukas, G.M.; Unger, J.; Karsbøl, J.D.; Hansen, T.; Bain, S.C. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, Y.; Avery, A. The efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide for glycaemic management in adults with type 2 diabetes compared to subcutaneous semaglutide, placebo, and other GLP-1 RA comparators: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2022, 28, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrén, B.; Masmiquel, L.; Kumar, H.; Sargin, M.; Karsbøl, J.D.; Jacobsen, S.H.; Chow, F. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily sitagliptin as an add-on to metformin, thiazolidinediones, or both, in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 2): A 56-week, double-blind, phase 3a, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, L.; Helleberg, H.; Roffel, A.; van Lier, J.J.; Bjørnsdottir, I.; Pedersen, P.J.; Rowe, E.; Derving Karsbøl, J.; Pedersen, M.L. Absorption, metabolism and excretion of the GLP-1 analogue semaglutide in humans and nonclinical species. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 104, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.; Bloch, P.; Schäffer, L.; Pettersson, I.; Spetzler, J.; Kofoed, J.; Madsen, K.; Knudsen, L.B.; McGuire, J.; Steensgaard, D.B.; et al. Discovery of the Once-Weekly Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogue Semaglutide. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 7370–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Capeau, J. Is the GLP-1 receptor agonist, semaglutide, a good option for weight loss in persons with HIV? AIDS 2024, 38, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghieri, M.; Christensen, A.S.; Andersen, A.; Solini, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. Future Perspectives on GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and GLP-1/glucagon Receptor Co-agonists in the Treatment of NAFLD. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bækdal, T.A.; Borregaard, J.; Hansen, C.W.; Thomsen, M.; Anderson, T.W. Effect of Oral Semaglutide on the Pharmacokinetics of Lisinopril, Warfarin, Digoxin, and Metformin in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, C.; Breitschaft, A.; Hartoft-Nielsen, M.L.; Jensen, S.; Bækdal, T.A. Effect of oral semaglutide on the pharmacokinetics of thyroxine after dosing of levothyroxine and the influence of co-administered tablets on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide in healthy subjects: An open-label, one-sequence crossover, single-center, multiple-dose, two-part trial. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021, 17, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziri Mehrabani, S.A.; Vatanpour, V.; Koyuncu, I. Green solvents in polymeric membrane fabrication: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaviska, F.; Drogui, P.; Grasmick, A.; Azais, A.; Héran, M. Nanofiltration membrane bioreactor for removing pharmaceutical compounds. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 429, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Tripathi, B.P.; Kumar, M.; Shahi, V.K. Membrane-based techniques for the separation and purification of proteins: An overview. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweers, L.J.H.; Lakemond, C.M.M.; Fogliano, V.; Boom, R.M.; Mishyna, M.; Keppler, J.K. Biorefining of liquid insect fractions by microfiltration to increase functionality. J. Food Eng. 2024, 364, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, A.V.; Molitor, M.S.; Burrington, K.J.; Otter, D.; Lucey, J.A. Partial enrichment of phospholipids by enzymatic hydrolysis and membrane filtration of whey protein phospholipid concentrate. JDS Commun. 2023, 4, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsinkaew, C.; Ajariyakhajorn, K.; Boonyaratanakornkit, V.; Sooksai, S.; Pornpukdeewattana, S.; Krusong, W.; Sitanggang, A.B.; Charoenrat, T. Membrane-based approach for the removal of pigment impurities secreted by Pichia pastoris. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 139, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlig, N.; Lehotay, S.J.; Lightfield, A.R. Comparison of filter membranes in the analysis of 183 veterinary and other drugs by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, 2300696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjerbæk Søtoft, L.; Lizarazu, J.M.; Razi Parjikolaei, B.; Karring, H.; Christensen, K.V. Membrane fractionation of herring marinade for separation and recovery of fats, proteins, amino acids, salt, acetic acid and water. J. Food Eng. 2015, 158, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomize, A.L.; Pogozheva, I.D.; Lomize, M.A.; Mosberg, H.I. The role of hydrophobic interactions in positioning of peripheral proteins in membranes. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.D. Ions from the Hofmeister series and osmolytes: Effects on proteins in solution and in the crystallization process. Methods 2004, 34, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydney, A.L. Protein Separations Using Membrane Filtration: New Opportunities for Whey Fractionation. Int. Dairy J. 1998, 8, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Riera, F.A. Influence of ionic strength on peptide membrane fractionation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 119, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.d.C.S.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Garcia Rojas, E.E.; Minim, L.A.; Oliveira, F.C.; Minim, V.P.R. Effect of pH and salt concentration on the solubility and density of egg yolk and plasma egg yolk. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.V.; Cross, E.R.; An, Y.; Pentlavalli, S.; Coulter, S.M.; Sun, H.; Laverty, G. Impact of counterion and salt form on the properties of long-acting injectable peptide hydrogels for drug delivery. Faraday Discuss. 2025, 260, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, A.M.; Zultanski, S.L.; Waldman, J.H.; Zhong, Y.-L.; Shevlin, M.; Peng, F. General Principles and Strategies for Salting-Out Informed by the Hofmeister Series. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2017, 21, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohrer, C.; Horrell, S.; Meier, S.; Sans, M.; von Stetten, D.; Hough, M.; Goldman, A.; Monteiro, D.C.F.; Pearson, A.R. Homogeneous batch micro-crystallization of proteins from ammonium sulfate. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2021, 77, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Qiao, M.; Shao, D.; Xie, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Luo, X. Alkaline pH-driven formation of protein-isoflavone nanoparticles: Functional characteristics and interaction mechanisms. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 174, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Přáda Brichtová, E.; Edu, I.A.; Li, X.; Becher, F.; Gomes dos Santos, A.L.; Jackson, S.E. Effect of Lipidation on the Structure, Oligomerization, and Aggregation of Glucagon-like Peptide 1. Bioconjugate Chem. 2025, 36, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Lu, J.; Cui, J. Protease-synthesized oligopeptide promoted with chitosan for pH-tolerant HIPEs. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2026, 729, 138819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, A.; González-Garcinuño, Á.; Cardea, S.; Marco, I.D.; Martín del Valle, E.M. PVDF-based membranes in biotechnology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 365, 132636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, S.; Zydney, A.L. Theoretical analysis of pore size distribution effects on membrane transport. J. Membr. Sci. 1993, 82, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Duval, C.E. Rare-Earth Element Adsorption to Membranes Functionalized with Lanmodulin-Derived Peptides. Langmuir 2025, 41, 9581–9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; Sun, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X. Quantitative Assessment of Interfacial Interactions Governing Ultrafiltration Membrane Fouling by the Mixture of Silica Nanoparticles (SiO2 NPs) and Natural Organic Matter (NOM): Effects of Solution Chemistry. Membranes 2023, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Liu, W.; Guo, C.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tian, Y. Complex coacervates and interaction mechanisms of flaxseed gum, flaxseed protein, and major milk proteins. LWT 2025, 231, 118286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wu, T.; Wu, J.; Chang, R.; Lan, X.; Wei, K.; Jia, X. Effects of cations on the “salt in” of myofibrillar proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 58, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, K.; Jaśkiewicz, M.; Neubauer, D.; Migoń, D.; Kamysz, W. The Role of Counter-Ions in Peptides—An Overview. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noro, M.G.; Frenkel, D. Extended corresponding-states behavior for particles with variable range attractions. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 2941–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venanzi, M.; Savioli, M.; Cimino, R.; Gatto, E.; Palleschi, A.; Ripani, G.; Cicero, D.; Placidi, E.; Orvieto, F.; Bianchi, E. A spectroscopic and molecular dynamics study on the aggregation process of a long-acting lipidated therapeutic peptide: The case of semaglutide. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 10122–10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qiu, G.; Kang, M.; Zhang, C.; Quan, W.; Zhou, H.; Fan, X.; Luo, J.; Lu, B.; Li, M. Insights into the dual inhibitory effects of phenylethanoid glycosides from Osmanthus fragrans flower on glycolipid metabolizing enzymes. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 168, 109328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, G.; Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Assessment of whole egg fractionation by tangential flow filtration: The problem of low-density lipoprotein aggregates. Food Bioprod. Process. 2023, 140, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makasewicz, K.; Carlström, G.; Stenström, O.; Bernfur, K.; Fridolf, S.; Akke, M.; Linse, S.; Sparr, E. Tipping point in α-synuclein-membrane interactions from stable protein-covered vesicles to amyloid aggregation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybek, P.; Dudek, G.; van der Bruggen, B. Cellulose-based films and membranes: A comprehensive review on preparation and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.