Abstract

A semi-empirical lumped parameter model for the extraction process of traditional Chinese medicine based on thermal equilibrium was established in this work. In this model, the effect of heat dissipation was considered. Differential equations was solved using numerical methods. Key model parameters such as the overall heat transfer coefficient and heat dissipation coefficient were obtained by fitting measured data. In the laboratory scale, Ginkgo biloba leaves were used as the liquid-solid extraction object to systematically investigate the effects of liquid-to-solid ratio, extraction temperature, solvent ratio, and slice particle size on the temperature changes during the extraction process. The average determination coefficient (R2) of the model fitting was 0.9955, and the R2 value for the prediction group was 0.9950. In the laboratory scale, extraction experiments of Xiaochaihu Decoction were conducted, and the performance of the model was verified. Furthermore, the model was applied to the mixed decoction process of five medicinal materials (Bupleurum, Glycyrrhiza, Scutellaria, Codonopsis, and Jujube) in industrial-scale for the production of Xiaochaihu capsules. The temperature change curves of three extraction tanks were all fitting well. The fitting results indicated abnormal heat transfer performance in Tank No. 1, providing a prompt for equipment maintenance and process optimization for the enterprise. A feasible method for temperature calculation and abnormal identification in the industrial process of traditional Chinese medicine extraction was provided in this work.

1. Introduction

Extraction is a key unit operation in the production of Chinese patent medicines, involving complex heat transfer, mass transfer, and chemical reactions. Extraction temperature, as a crucial parameter affecting the dissolution rate of active ingredients and extraction efficiency, directly influences product quality, energy consumption, and production costs. Currently, the TCM extraction process often relies on empirical control [1], lacking support from systematic dynamic temperature models, which frequently leads to issues such as imprecise temperature control, high energy consumption, and fluctuating extraction efficiency during process scale-up.

In recent years, with the development of process modeling and simulation technologies, extraction process models based on heat transfer principles have gradually become a research focus. Scholars have conducted research from various perspectives: analyzing the effect of temperature on component dissolution by combining kinetics and thermodynamics [2]; constructing multi-component coupling models to reveal the differential effects of temperature on stability [3]; achieving refined simulation of the extraction temperature field using the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) [4]; employing robust optimization to reduce the impact of raw material fluctuations on extraction efficiency [5]; and establishing dynamic extraction process models [6]. These studies provide cross-disciplinary methodological support for building heat transfer models for TCM extraction. Simultaneously, some research teams have conducted modeling and control studies specifically for the TCM extraction process, such as developing digital twin control systems [7], applying adaptive fuzzy PID control [8,9], establishing temperature control models [10], and constructing dynamic extraction models using the step response method [11], etc. These studies provide cross-domain methodological support for the construction of heat transfer models for TCM extraction.

However, existing research still has shortcomings: many are limited to ideal constant temperature conditions, with insufficient consideration of dynamic temperature behavior under variable temperature environments in actual production, multi-batch variations, and multi-scale equipment. Limited research focused on the impact of TCM’s “multi-component, multi-batch” characteristics in modeling [12,13]. Relatively little attention was paid to the influence of environmental heat dissipation on temperature changes [14,15], making it difficult to fully reflect actual production processes. Furthermore, current modeling research on TCM extraction processes still focuses primarily on mass transfer models, with relatively insufficient systematic research specifically targeting heat transfer mechanism. For example, Chen et al. [16] and Zhang et al. [17] established extraction kinetic models for medicinal materials based on Fick’s law, revealing the relationship between material microstructure and extraction efficiency; Chen et al. [18] proposed a hybrid modeling method combining mechanism and data-driven approaches; Song et al. [19] constructed decoction kinetic equations by combining Fick’s law and the Higbie model. Although Gao et al. [20] simulated the mass and heat transfer process of oak leaves in a hydrothermal environment using COMSOL, the focus remained primarily on mass transfer at the particle scale, with insufficient discussion on the heat transfer mechanism. However, Lan et al. [21] pointed out that accurately determining the boiling time in the decoction tank could potentially reduce energy consumption in the extraction process by more than 20%, which indicates the importance of heat transfer in the extraction process. Overall, existing research tends to emphasize mass transfer models, with limited attention to heat transfer, especially practical factors like heat dissipation during extraction, which is the research gap this paper aims to address.

Therefore, this paper aims to construct a heat transfer model applicable to the TCM extraction process. This model comprehensively considers factors such as equipment structure, material properties, and heat dissipation, enabling accurate description of the dynamic temperature relationship between the heating medium and the interior of the extraction tank. The reliability of the model is verified through laboratory-scale extraction experiments with Ginkgo biloba leaves and Xiaochaihu Decoction. It is then extended to the industrial-scale extraction process of Xiaochaihu Capsules to explore its application value in process optimization and equipment diagnosis, providing theoretical support and a methodological foundation for the intelligent and refined management of TCM extraction processes.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Ultrapure water was prepared by a water purification system (Milli-Q, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Ginkgo biloba leaves included three batches. Batch A1 was provided by Zhejiang Conba Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) with a initial batch number of YYC20181007. Batch A2 was a mixture of batch numbers 20231214 (Chenyu Bencao Co., Ltd., Haozhou, China) and 20231203 (Anhui Meikang Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Haozhou, China). Batch A3 was obtained from Bozhou Da Xibei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Haozhou, China) with a initial batch number of 20231225. The ingredients for Xiaochaihu Decoction (Bupleurum, Scutellaria, Codonopsis, Pinellia, Glycyrrhiza, fresh ginger, and jujube) were purchased from Anshun Yitang Medicine Flagship Store of Hebei Shuxiangkang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Baoding, China) on 25 July 2025.

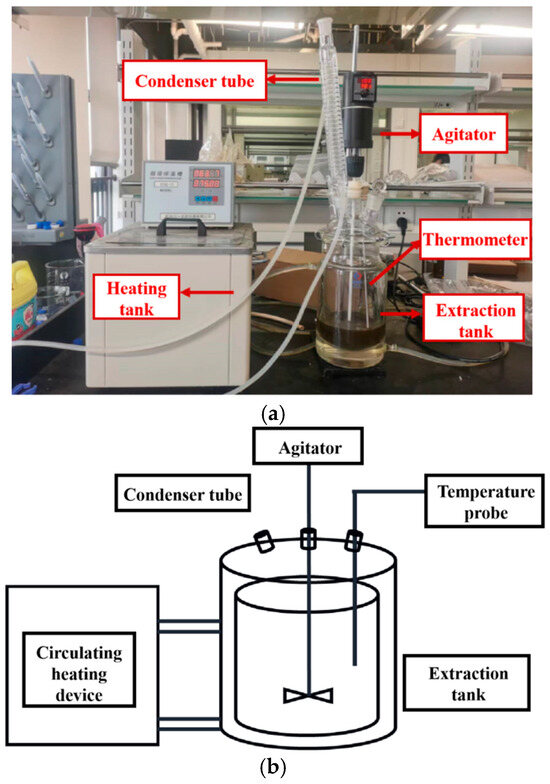

2.2. Ginkgo Biloba Leaf Extraction Experimental Conditions

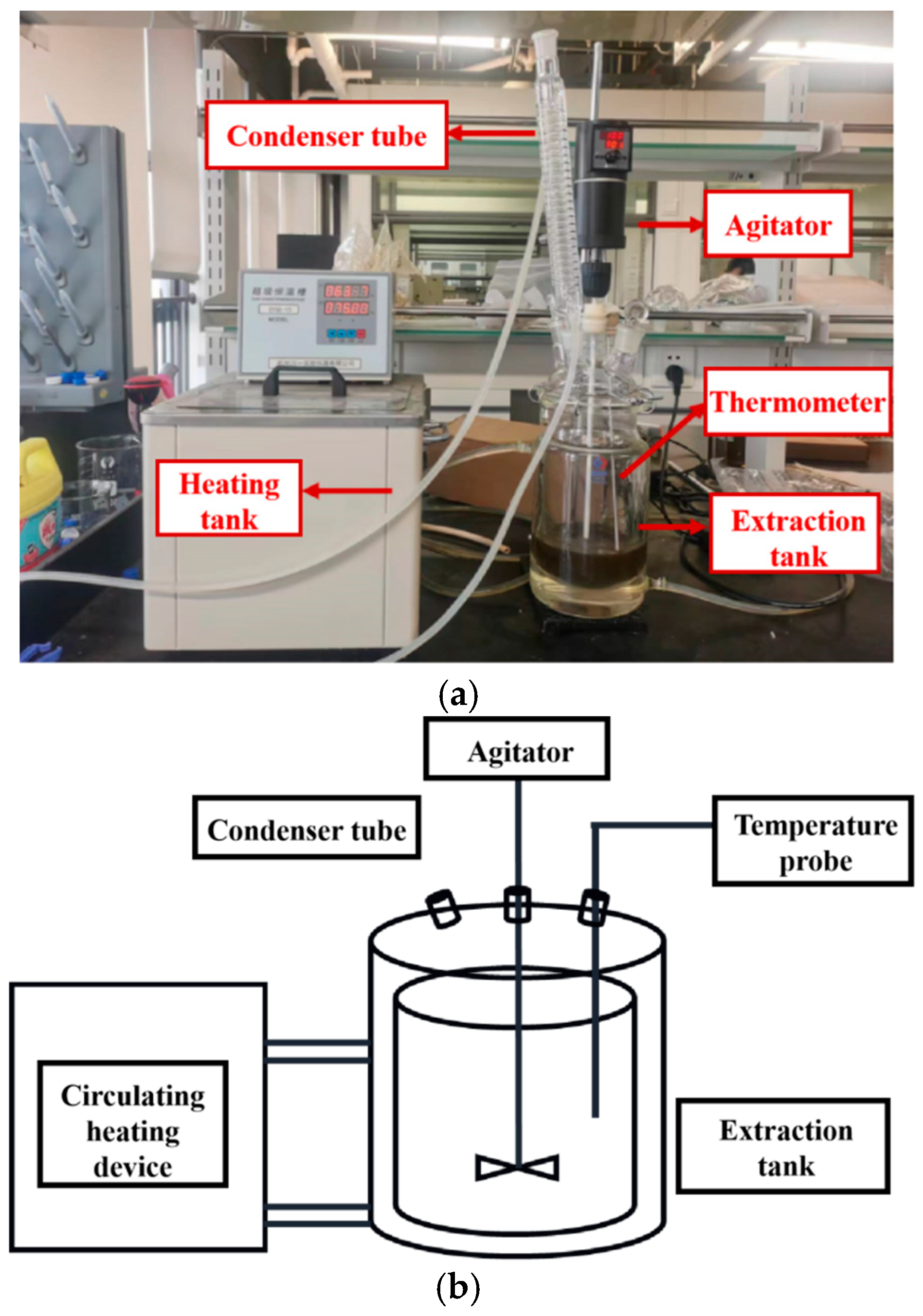

The factors investigated in the extraction process include heating temperature, the ethanol ratio (v/v) in the ethanol-water mixed solvent, solid–liquid ratio, particle size of the slices, and the batch of the slices. The experimental setup and the physical image of the extraction process are shown in Figure 1. Different groups of extraction experiments are shown in Table 1. The extraction process involved soaking the slices for 1 h, followed by heating for 3 h using a heating bath (high-temperature circulator (HMGX-2005, Jiangsu Hengmin Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Yancheng, China) with stirring at 100 rpm. The heating time was approximately 1 h, and the holding extraction time was about 2 h. Temperature data of the extract tank and the heating medium at different time points during the extraction process were collected.

Figure 1.

Ginkgo leaf extraction process equipment diagram. (a) Physical diagram of Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction process. (b) Schematic diagram of Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction process.

Table 1.

Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction experimental table. A1–A3 represent three different batches of ginkgo leaves.

2.3. Xiaochaihu Decoction Extraction

Bupleuri Radix decoction pieces (74.15 g), Pinelliae Rhizoma (37.6 g), Scutellariae Radix (27.85 g), Codonopsis Radix (27.84 g), Zingiberis Rhizoma Recens (27.83 g), Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (27.86 g), and Jujubae Fructus (27.83 g) were weighed and placed in a glass extraction tank. The temperature of the high-temperature circulator was set to 95 °C. 2500 mL of water (10 times the water volume) was added, and the mixture was soaked for 0.5 h. After heating up to the set temperature (approximately 1 h), extraction was carried out at the set temperature for 1.5 h. After the first extraction was completed, the aqueous extract was filtered out using a mesh screen. Then, 2500 mL of water (10 times the water volume) was added again for the second extraction. After heating up to the set temperature (approximately 0.5 h), extraction was carried out at the set temperature for 1.5 h. The temperature data inside the extraction tank and the heating bath temperature at different time points during the extraction process were collected.

2.4. Industrial Extraction of Xiaochaihu Capsules

The extraction production process of Xiaochaihu capsules was completed at Zhejiang Zansheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Taizhou, China). The production steps are as follows: During the feeding process, 534 kg of Bupleurum slices, 200.4 kg of Scutellaria slices, 146.4 kg of Codonopsis slices, 146.4 kg of Glycyrrhiza slices, and 200.4 kg of jujube slices were added to each of the three industrial extraction tanks. The industrial steam pressure used for extraction was typically controlled between 0.2 MPa and 0.3 MPa. For the first extraction, 4092 L of purified water was added, soaked for about 1 h, and then the steam valve was opened to heat. The set extraction temperature was generally 99.95 °C, but the actual temperature may deviate slightly. Once the temperature indicator reached the set temperature, the steam was stopped. When the tank temperature drops below the set temperature, the steam valve was reopened to raise the temperature back to the set value. The specific control was performed through the industrial control system using PID control to maintain the tank temperature. After about 1.5 h of holding extraction, the valve was opened to discharge the aqueous extract. After discharging, 3274 L of purified water was added for the second extraction, and the steam was introduced to reach the set temperature for holding extraction. After the holding extraction, the first and second extracts were combined and sent to the concentration stage for further production. In actual extraction, the heating duration and holding extraction duration may vary slightly. The industrial extraction tanks are shown in Figure 2.

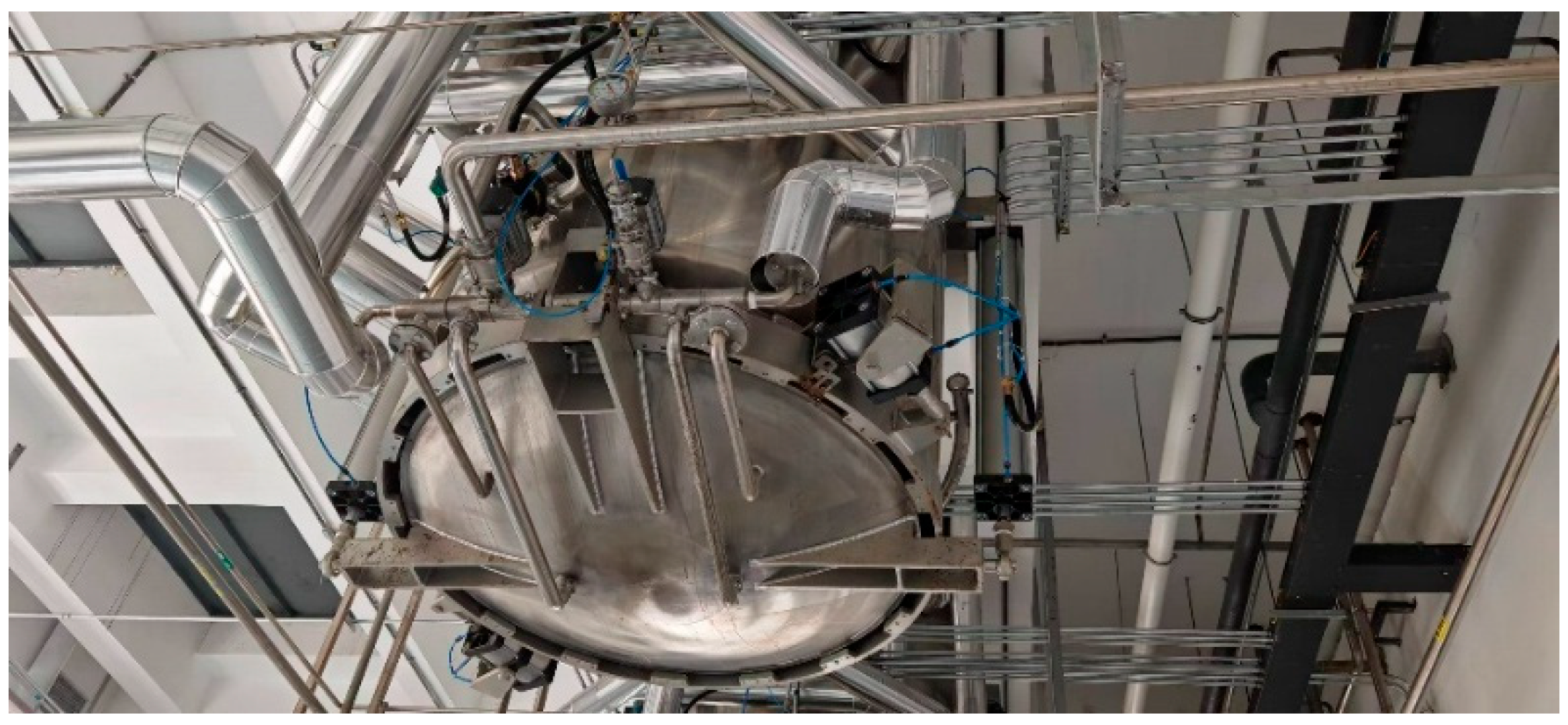

Figure 2.

An industrial extraction tank.

2.5. Modeling and Solution

2.5.1. Heat Transfer Process Modeling

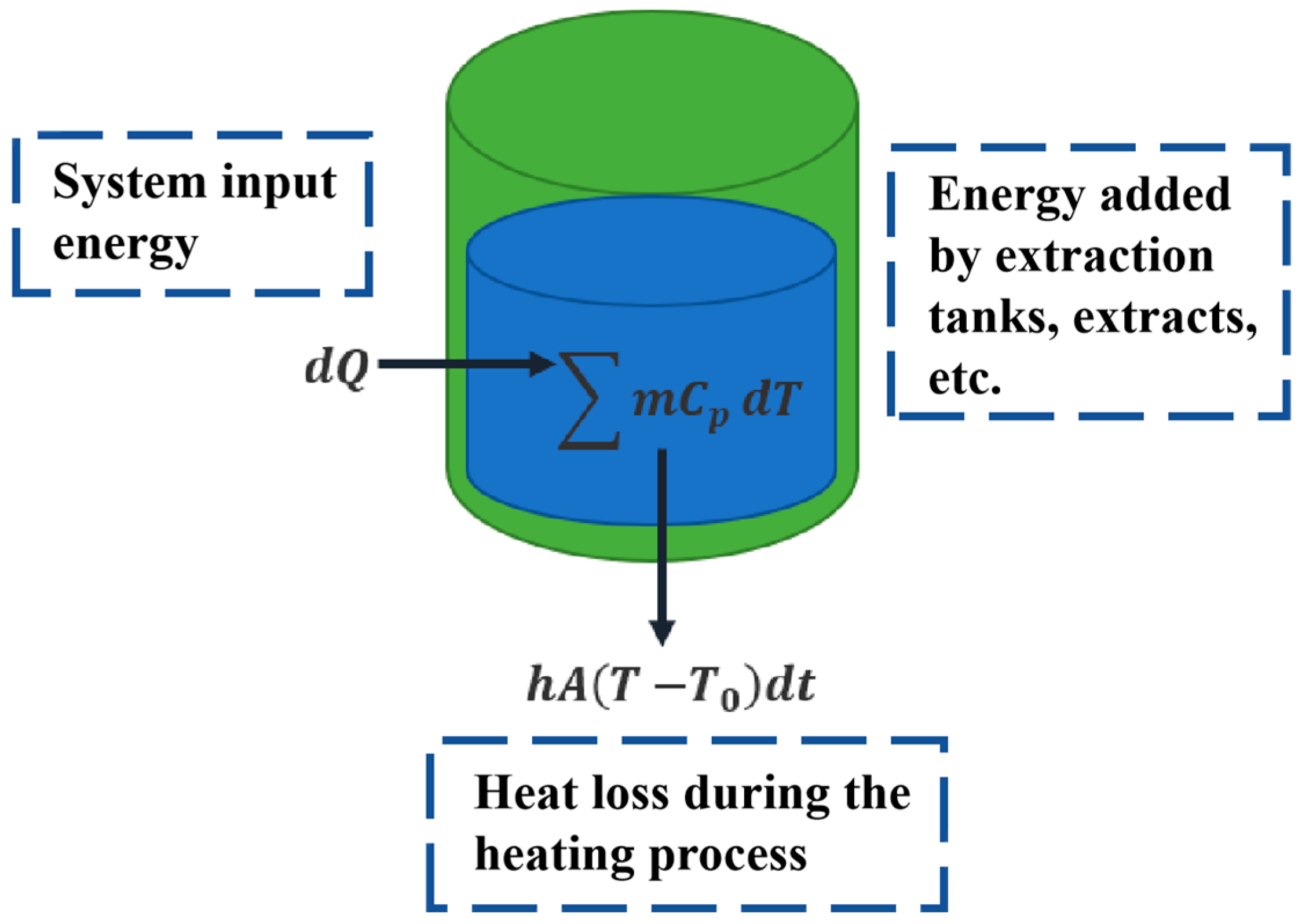

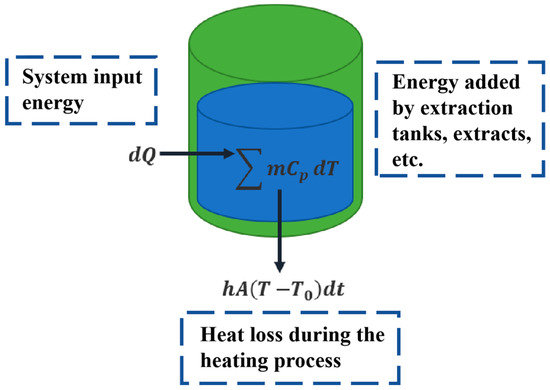

Heat balance was performed and modeled for the extraction process to establish the relationship between the heating medium temperature and the internal temperature of the extraction tank, as shown in Figure 3. During the heating process, the heating medium temperature rises slowly, and the internal temperature of the extraction tank also rises slowly due to heat conduction through the tank wall. To quantitatively describe the time-varying characteristics of the heating medium temperature and the internal extraction tank temperature during the extraction process, based on the heat transfer law, the relationship between the heat transfer rate and the temperature inside the extraction tank is written as Equation (1).

where is the overall heat transfer coefficient, is the heat exchange area between the jacket and the container, is the temperature of the medium inside the jacket, and is the temperature of the solution inside the extraction tank. At the laboratory scale, was derived from the measured temperature curve of the heating bath. At the industrial scale, was obtained by back-calculating from the steam pressure using the Antoine equation (as described later in Section 3.3.1).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of temperature modeling for the extraction process. Green color represents the extraction tank; Blue color represents the extract.

According to the law of energy conservation, the heat relationship during jacket heating is expressed as follows:

where , is the mass of the extraction tank, is the specific heat capacity of the extraction tank, is the mass of the decoction pieces, is the specific heat capacity of the decoction pieces, is the mass of the extraction solvent, is the specific heat capacity of the extraction solvent, is the heat dissipation area of the liquid phase bulk, is the heat exchange coefficient between the solution and the external environment, is the solution temperature, and denotes the measured soaking temperature of the medicinal materials at . Although in practice, there may be fluctuations of a few degrees Celsius during long industrial batches, its impact is negligible and can therefore be considered constant. In the calculation, the extraction apparatus is considered cylindrical. Since heating is mostly from the sides and bottom, the heat exchange area between the jacket and the container can be regarded as the side and bottom areas of the cylinder, and the heat dissipation area can be regarded as the top area of the cylinder.

Combining the equations yields:

In the above equation, the overall heat transfer coefficient “” and the heat transfer coefficient “” are fitting parameters to be determined. Since is not constant and varies over time during the actual extraction process, this linear non-autonomous ordinary differential equation, based on the measured heat transfer driving force , is solved using numerical methods.

In this study, assumptions of constant specific heat capacity (Cp) and constant physical properties are adopted, while the extraction temperature in some experiments approaches 95–100 °C. This approximate treatment may introduce certain systematic errors. From a physical perspective, thermophysical parameters of materials (such as specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, etc.) generally exhibit nonlinear variations with increasing temperature. The assumption of constancy under high-temperature conditions may, to some extent, deviate from the actual heat and mass transfer processes. However, for the first-order simplified model constructed in this study, such errors remain within an acceptable range. Moreover, this assumption significantly reduces the computational complexity of the model, ensuring computational efficiency and intuitive interpretability of the results, making it a reasonable choice for balancing model accuracy and practicality.

2.5.2. Calculation

During solution, the differential equation is transformed into a difference equation and solved using the finite difference method. Since the actually observed and recorded temperatures are discrete values, i.e., the internal temperature of the extraction tank , an appropriate interpolation method was used to obtain , ensuring consistency between the temperature vector and the number of micro-elements, thus facilitating numerical solution. In actual computation, because the coefficients on the right side of the differential equation are mostly related to temperature, it is a differential equation with variable coefficients. The finite difference method was used for numerical solution. In each step of the iterative loop, the iterative coefficients are converted into expressions related to temperature for iterative calculation and solution. All calculation programs were self-developed and implemented in MATLAB software (version 2024a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

An optimization algorithm was used to fit the parameters for modeling the temperature and concentration during the extraction process. The objective function was defined as the sum of squared errors (SSE):

where is the number of experimental groups, is the number of experimental data points, is the measured value of the -th data point in the -th experimental group, and is the predicted value at the corresponding time point calculated by the model for the -th point in the -th experimental group under that parameter set.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA) was selected for global parameter fitting. GA is a classic optimization algorithm capable of global optimization. The optimized parameters were substituted into the model, and the coefficient of determination (R2) for multiple experimental groups was calculated using the model results to evaluate the model’s fitting performance. The formula for calculating the coefficient of determination is as follows:

where is the number of experimental data points, is the measured value of the -th point in the measured curve, is the average value of all points in the curve, and is the calculated value of the temperature inside the extraction tank obtained from the model calculation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Application at Laboratory Scale: Ginkgo Biloba Leaf Extraction

3.1.1. Model Fitting

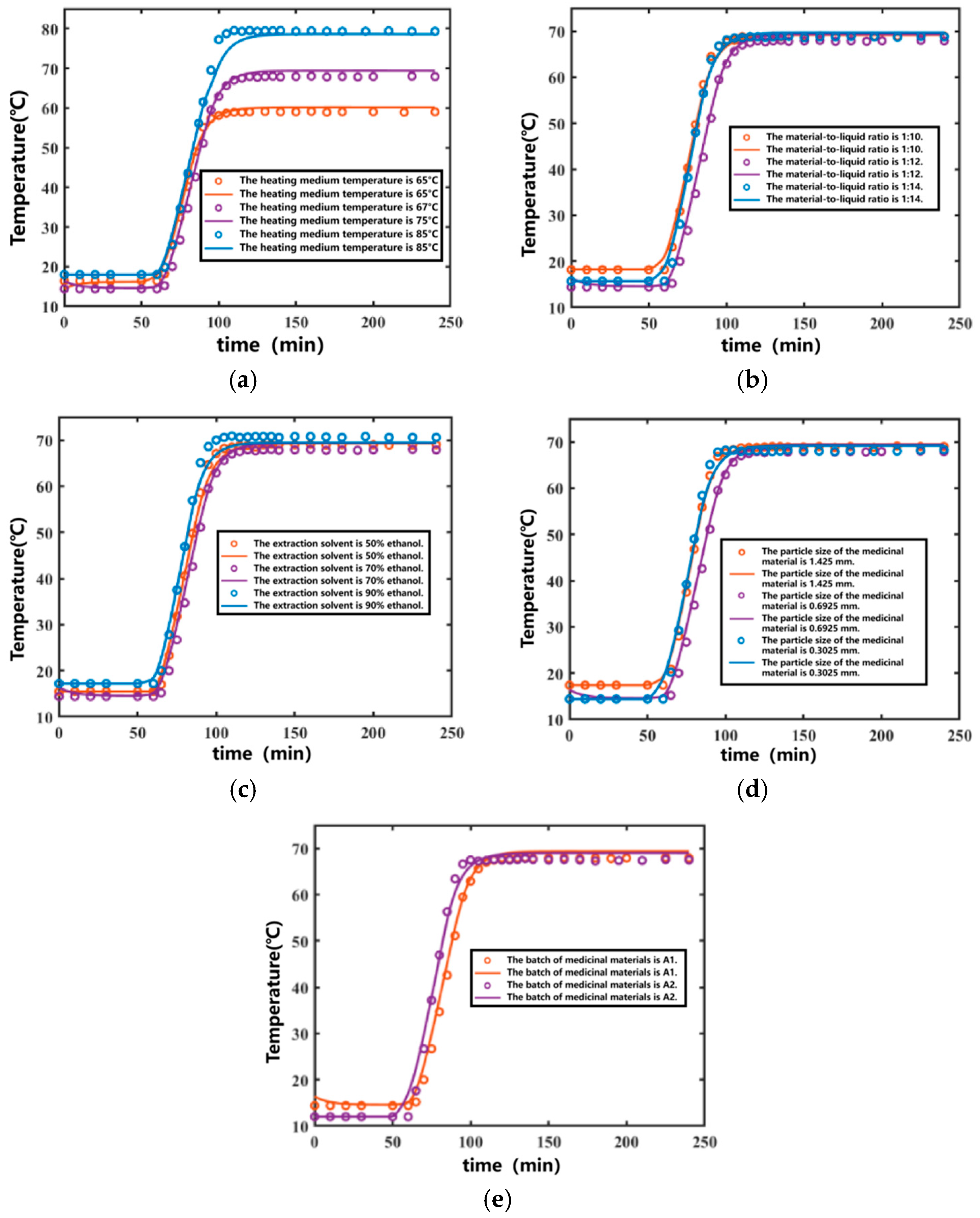

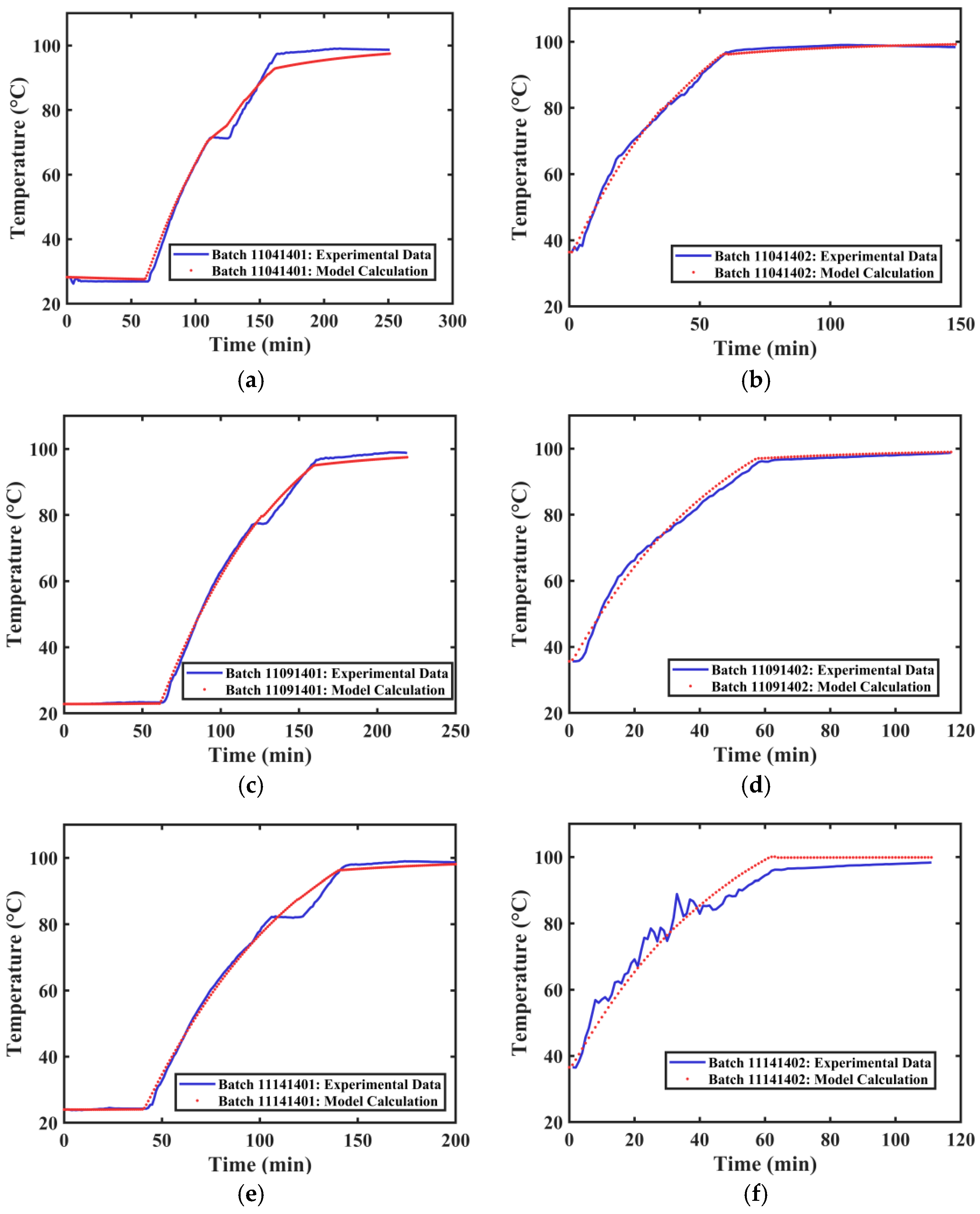

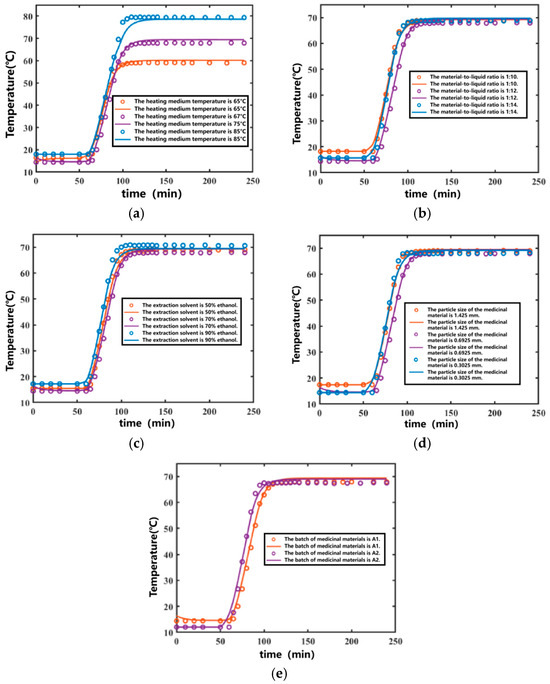

By substituting the fitted temperature parameters into the results, the temperature variation curve over time was obtained, as shown in Figure 4. The coefficients of determination (R2) for the fitted curves of the internal temperature variations in the extraction tank during the ten Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction processes were 0.9953, 0.9952, 0.9940, 0.9977, 0.9941, 0.9971, 0.9965, 0.9977, 0.9940, and 0.9933, respectively. The average coefficient of determination was 0.9955. Overall, the fitting performance was satisfactory. The parameters obtined through multi-group global fitting are not limited to individual experiments but demonstrate adaptability across different batches of ginkgo leaf extraction processes, effectively reflecting the temperature variation patterns within the extraction tank. The relevant parameter details from three global fittings for different batches of ginkgo leaf extraction are provided in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Temperature curves of the Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction process under different conditions. (Points represent experimental values—represents calculated curves). (a) Fitting results of different heating temperatures. (b) Fitting results of different solid-to-liquid ratios. (c) Fitting results of different extraction solvents. (d) Fitting results of different decoction piece particle sizes. (e) Fitting results of different decoction piece batches.

Table 2.

Parameter information for different batches of ginkgo biloba leaf extraction processes obtained from three fittings.

During the soaking stage, the temperature inside the extraction tank remained constant. After the heating medium temperature increased, the internal temperature of the extraction tank also increased until it stabilized. The higher the heating medium temperature, the higher the maximum temperature inside the extraction tank, and a longer time was required to reach equilibrium. The developed extraction model simulated the above phenomena well, as shown in Figure 4a.

Regarding the parameter selection in this study, taking the ginkgo leaf extraction process as an example, the model employs only two parameters to fully describe the extraction process across 11 datasets, resulting in a low risk of overfitting. Additionally, a supplementary sensitivity analysis was conducted. We found that the predictive performance does not vary significantly with minor parameter changes.

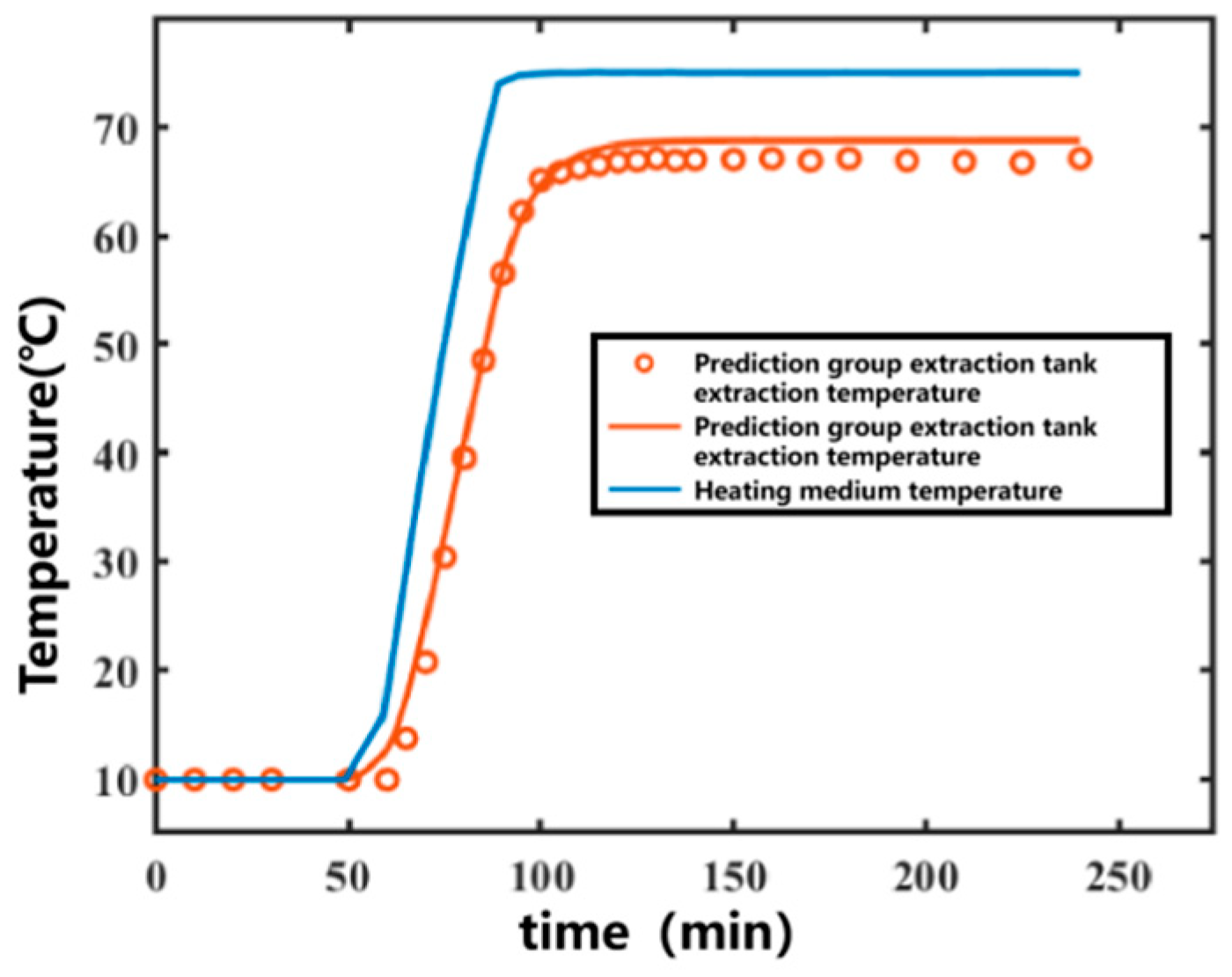

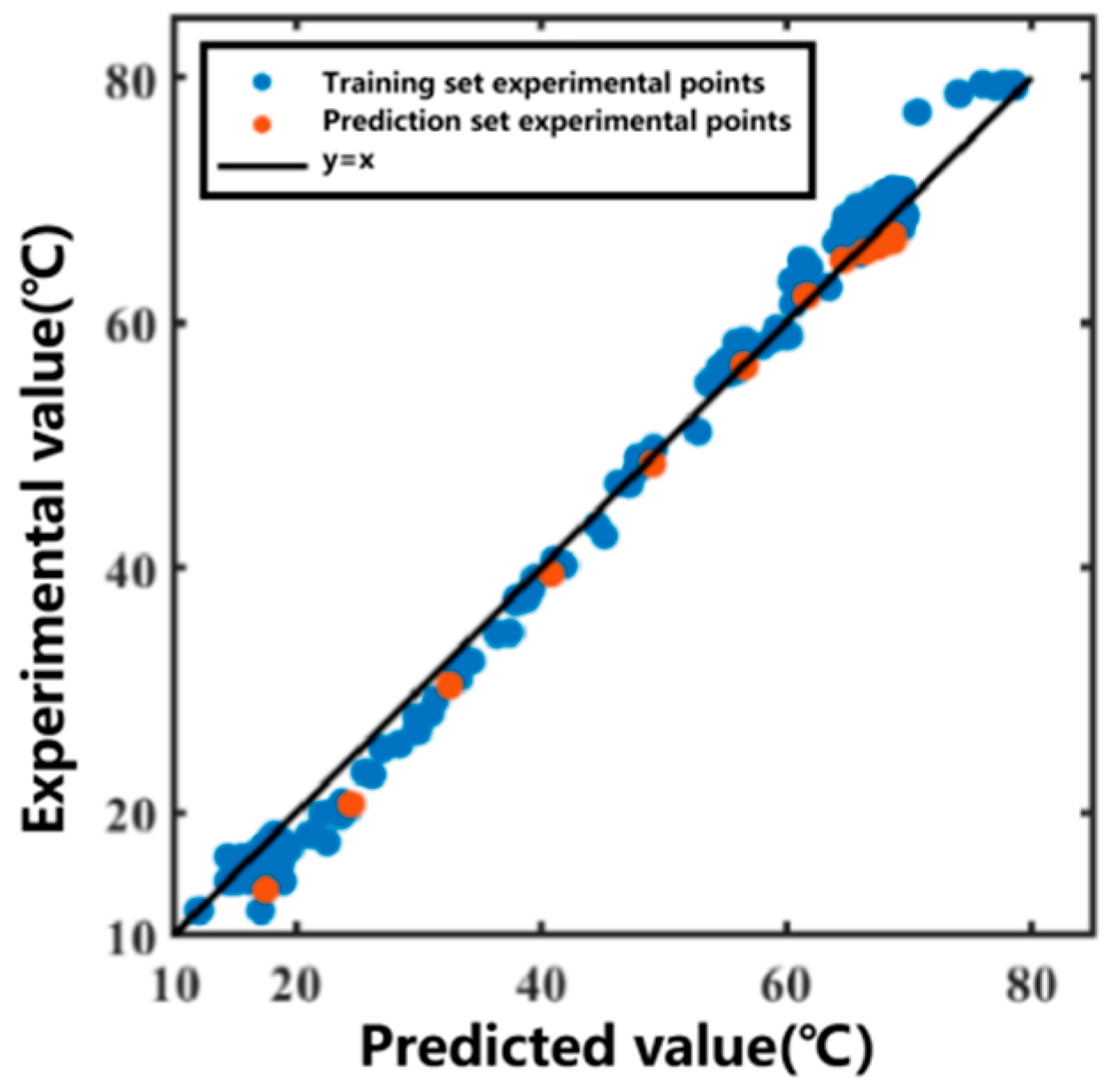

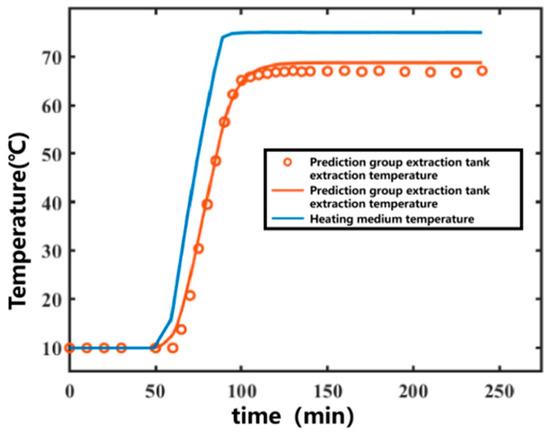

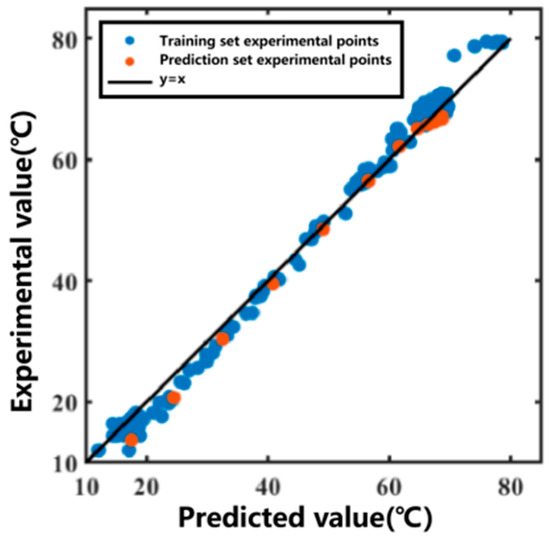

3.1.2. Using the Model for Prediction

The 11th set was used as the prediction set for forecasting. After obtaining the temperature variation in the heating medium, the temperature variation curve inside the extraction tank over time was predicted, as shown in Figure 5. The prediction R2 for the prediction set was 0.9950. The data fitting part served as the training set, and the prediction group served as the prediction set. The correlation plot between the actual values and predicted values of the model is shown in Figure 6. Most of the predicted temperature values versus the measured values lie on the line. This indicates that the model developed in this study can satisfactorily predict the extraction temperature changes.

Figure 5.

Predicted temperature results for the prediction set under experimental conditions for Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction. (Points represent experimental values—represents predicted curves).

Figure 6.

Correlation plot between predicted and measured temperatures for the Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction process.

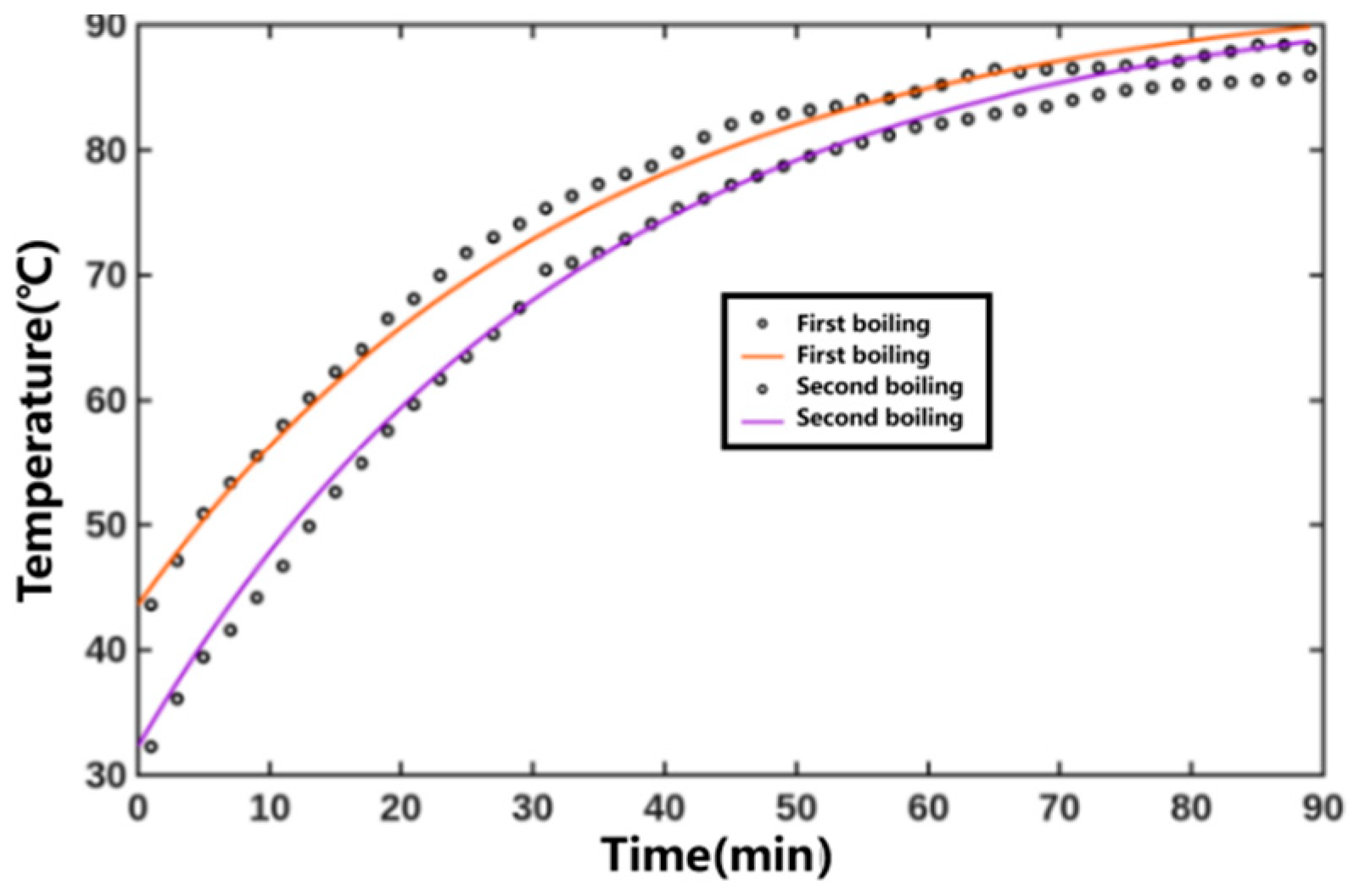

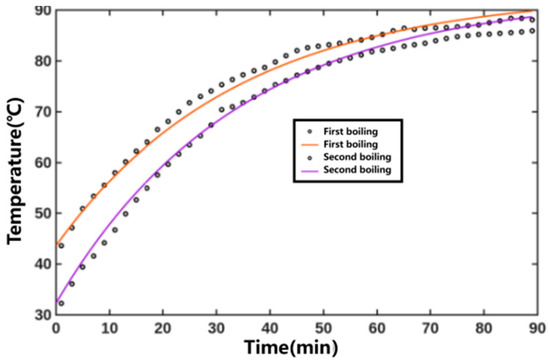

3.2. Application at Laboratory Scale: Xiaochaihu Decoction Extraction

The fitted temperature parameters were substituted into the results to obtain the temperature versus time curve, as shown in Figure 7. The heating medium temperature was constant, and the internal temperature of the extraction tank gradually increased. The coefficient of determination R2 for fitting the internal temperature variation curves of the extraction tank during the first and second decoctions of Xiaochaihu Decoction were 0.9904 and 0.9915, respectively. The relevant parameters obtained from three global fittings for the Xiaochaihu Decoction extraction process are detailed in Table 3. Overall, the fitting effect was satisfactory.

Figure 7.

Predicted temperature results for the prediction set of the Xiaochaihu Decoction extraction process (Points represent experimental values—represents predicted curves).

Table 3.

Parameter information for the Xiaochaihu Decoction extraction process obtained from three fittings.

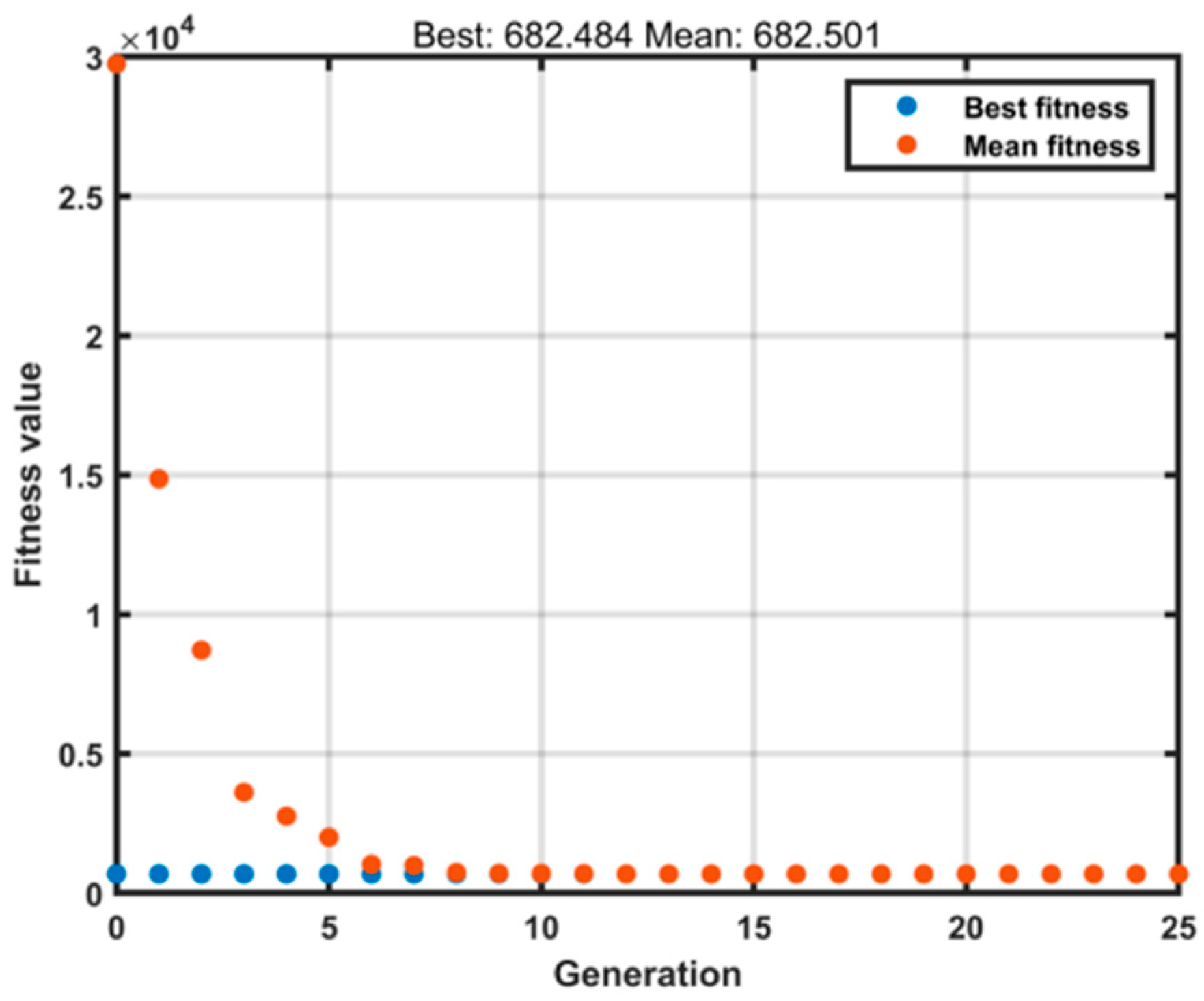

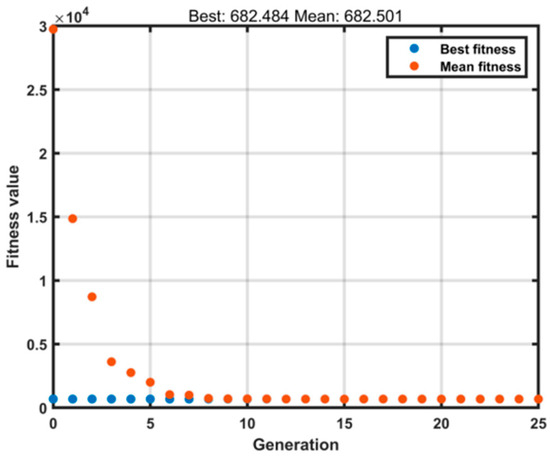

The optimized parameters varied slightly across different groups. In the extraction processes of ginkgo leaves and Xiaochaihu Decoction, only two parameters required fitting. The genetic algorithm (GA) optimization utilized relevant MATLAB functions with the following settings: population size of 500, maximum generations of 25 (as shown in Figure 8), and a mutation probability of 0.05. All other parameters remained consistent with the default MATLAB settings. Each optimization approach was executed three times in parallel, and both the heat dissipation coefficient and heat transfer coefficient demonstrated good consistency across runs.

Figure 8.

Model Iteration.

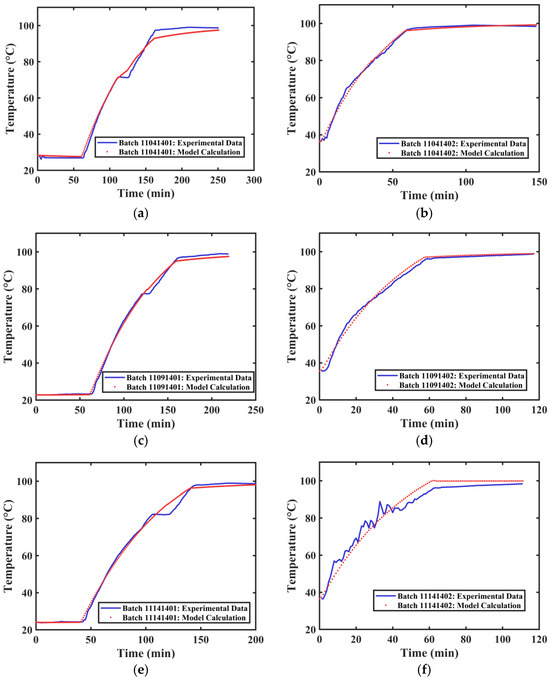

3.3. Application at Industrial Production Scale: Mixed Decoction of Five Herbs in Xiaochaihu Capsules

3.3.1. Fitting of Industrial Data

The temperature data and steam pressure data from three batches of Xiaochaihu Capsule extraction processes (20241104, 20241109, and 20241114) were collected. Since each extraction was performed in three extraction tanks, they were recorded as Tank 1, Tank 2, and Tank 3 according to their tank numbers, resulting in a total of 18 extraction datasets (each extraction includes data from the first and second extractions). This data was provided by Zhejiang Zansheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Taizhou, China). Since the obtained data was steam pressure data, it was converted to temperature data using the Antoine equation. Then, based on the temperature model developed in Section 2.4, the overall heat transfer coefficient and heat dissipation coefficient for different extraction tanks were obtained by fitting the temperature data.

Based on the model and algorithm, three global fittings were conducted to obtain the heat dissipation coefficients, overall heat transfer coefficients for the first extraction, and overall heat transfer coefficients for the second extraction of three industrial extraction tanks, as shown in Table 4. Overall, the heat dissipation coefficients of different extraction tanks were low, ranging between 0.5 and 5 . The overall heat transfer coefficients for the first extraction process ranged between 270 and 510 , and those for the second extraction process ranged between 460 and 1000 . The overall heat transfer coefficient for the first extraction process was relatively lower compared to the second extraction. Comparing the fitted overall heat transfer coefficients of different extraction tanks, it was found that the overall heat transfer coefficients for both the first and second extractions of Tank 1 were significantly lower than those of Tank 2 and Tank 3. This result suggests that the enterprise should inspect the equipment and pipelines of Tank 1 to identify factors leading to the low heat transfer coefficient. While factors such as insufficient insulation conditions, abnormal steam condensation modes, and partial jacket filling could all contribute to a decrease in the overall heat transfer coefficient, pipeline blockage remains the most plausible root cause in this study. On one hand, the experiment strictly controlled insulation parameters and jacket filling ratios throughout the process, eliminating interference from non-target variables. On the other hand, post-failure disassembly revealed significant sediment buildup on the inner walls of the pipeline, with the sediment composition closely matching the crystallizable components in the material. This directly confirms the obstruction effect of the blockage on steam flow and heat exchange efficiency. In contrast, other factors lack direct physical evidence within the experimental framework, making pipeline blockage the primary factor leading to the reduction in the overall heat transfer coefficient.

Table 4.

Fitted Parameters of Different Extraction Tanks.

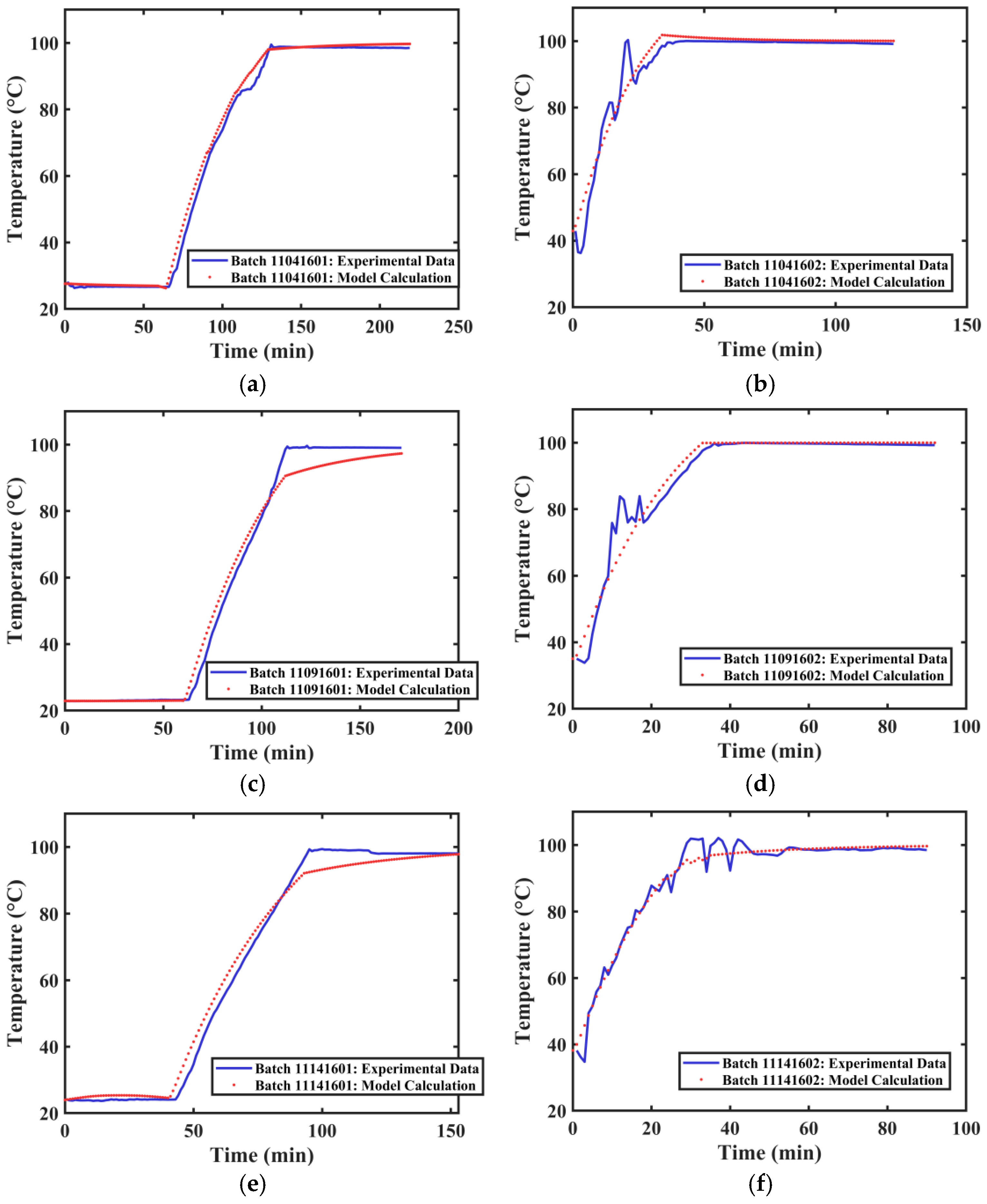

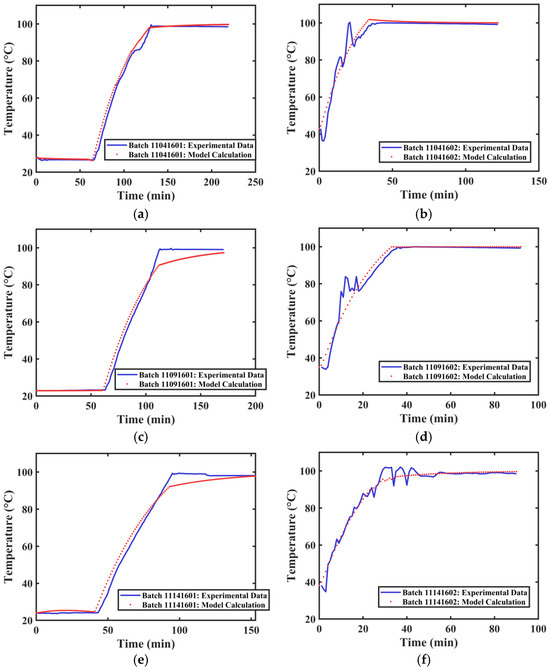

The actual extraction tank temperature profile data and the calculated temperature profiles for different extraction processes of Tank 1 are shown in Figure 9. The average R2 value obtained from fitting the temperature curves of different groups was 0.9882. The overall fitting effect is good, capable of simulating the internal temperature changes in the industrial extraction tank.

Figure 9.

Temperature Variation Curves of Extraction Tank 1. (a) First extraction on 4 November 2024. (b) Second extraction on 4 November 2024. (c) First extraction on 9 November 2024. (d) Second extraction on 9 November 2024. (e) First extraction on 14 November 2024. (f) Second extraction on 14 November 2024.

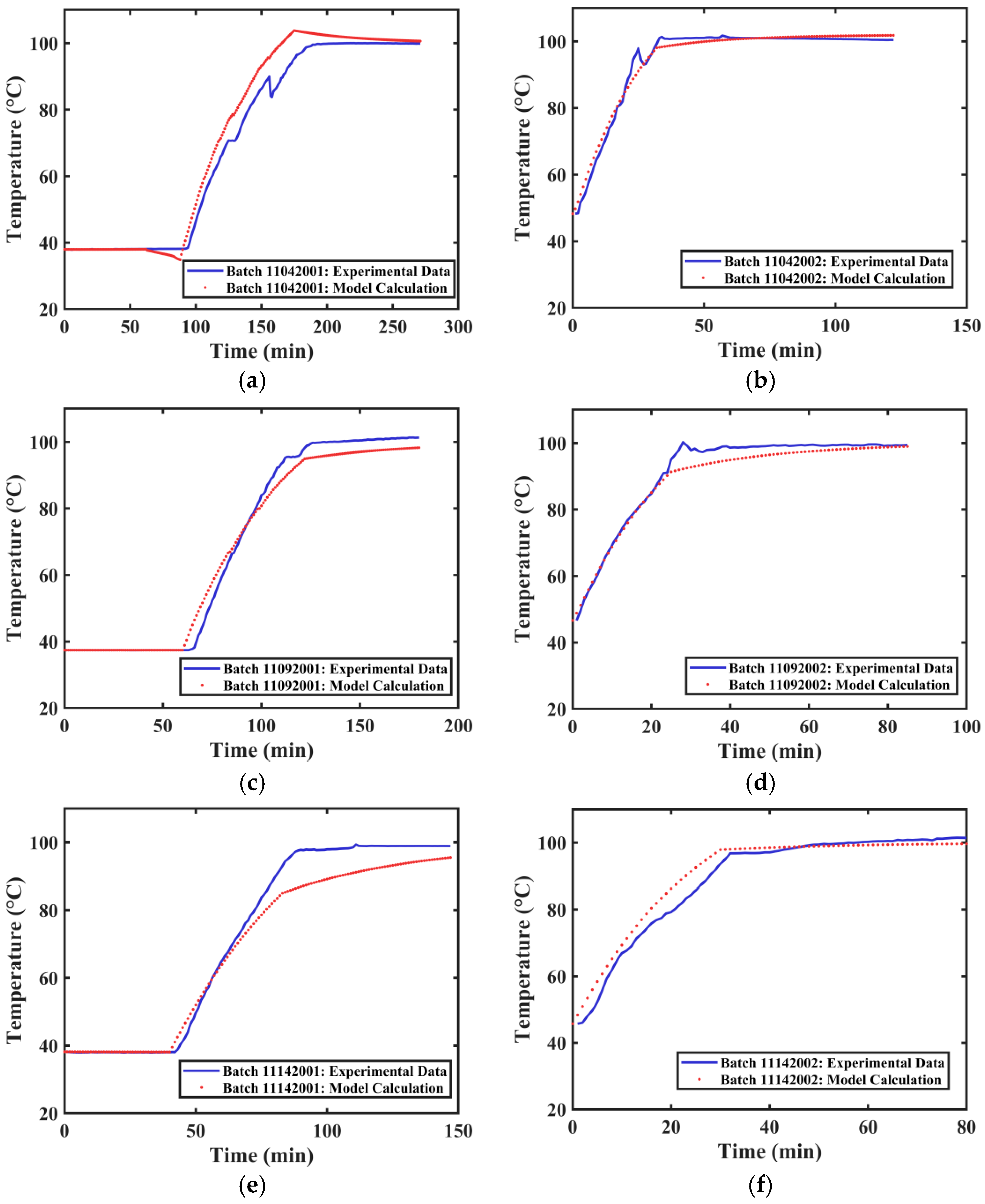

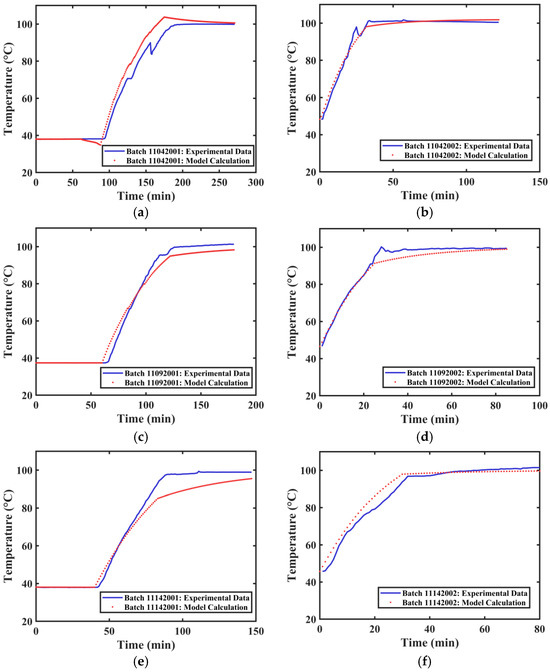

The actual extraction tank temperature profile data and the calculated temperature profiles for different extraction processes of Tank 2 are shown in Figure 10. The average R2 value obtained from fitting the temperature curves of different groups was 0.9736. The actual extraction tank temperature profile data and the calculated temperature profiles for different extraction processes of Tank 3 are shown in Figure 11. The average R2 value obtained from fitting the temperature curves of different groups was 0.9708. The developed method can satisfactorily simulate the internal temperature changes in different extraction tanks.

Figure 10.

Temperature Variation Curves of Extraction Tank 2. (a) First extraction on 4 November 2024. (b) Second extraction on 4 November 2024. (c) First extraction on 9 November 2024. (d) Second extraction on 9 November 2024. (e) First extraction on 14 November 2024. (f) Second extraction on 14 November 2024.

Figure 11.

Temperature Variation Curves of Extraction Tank 3. (a) First extraction on 4 November 2024. (b) Second extraction on 4 November 2024. (c) First extraction on 9 November 2024. (d) Second extraction on 9 November 2024. (e) First extraction on 14 November 2024. (f) Second extraction on 14 November 2024.

3.3.2. Discussion on Industrial Data Fitting Results

The industrial extraction process was studied through the workflow of data collection, data preprocessing, temperature profile modeling, parameter fitting, and simulation exploration under different operating conditions. To shorten the extraction process time, improve concentration efficiency, and reduce production costs, this study provides the following suggestions for the industrial extraction process of Xiaochaihu: The heat transfer performance of Tank 1 in the Xiaochaihu industrial extraction equipment is lower than that of the other tanks, and the cause needs to be investigated. After factory inspection, it was found that the steam transmission pipeline was partially blocked. The improvement measure is to regularly clean the steam pipeline. According to feedback from the factory, the heat transfer of Tank 1 was improved.

Furthermore, analyzing the differences in heat transfer properties between laboratory and industrial-scale extraction equipment reveals that the heat dissipation coefficient of the laboratory setup is significantly higher than that of the industrial equipment. This is likely because the laboratory setup lacks specialized insulation measures such as insulation cotton, making it more prone to heat loss, whereas the industrial extraction tank is equipped with comprehensive insulation solutions for energy conservation and emission reduction, resulting in a lower heat dissipation coefficient. Meanwhile, the heat transfer coefficient of the laboratory setup is relatively lower than that of the industrial equipment. The heat transfer coefficient is closely related to the material of the heating vessel and the properties of the heating medium. The laboratory extraction tank is made of glass, which has relatively poor thermal conductivity. The laboratory extraction tank uses silicone oil as the heating medium. In contrast, the industrial extraction tank is constructed from stainless steel, which offers superior thermal conductivity, and employs industrial steam as the heating medium, which provides more efficient heat transfer. The combination of these two aspects leads to the differences in heat transfer characteristics between industrial and laboratory scales.

When fitting the internal temperature of the extraction tank in this study, the difference in the initial temperature of the material inside the tank was not considered. During the second extraction, since the material was already hot, the extraction liquid heated up more rapidly in practice. This may explain why the heat transfer coefficient obtained from the fitting for the second extraction is higher than that for the first extraction.

4. Conclusions

A heat transfer model for the TCM extraction process based on heat conduction laws is developed in this work. Since the model considers heat dissipation during the extraction process, it can accurately describe the dynamic changes in the internal temperature of the extraction tank over time. Validation through laboratory-scale Ginkgo biloba leaf extraction experiments showed that the model exhibited good fitting and prediction capabilities under different process conditions, with an average R2 exceeding 0.995. Validation through laboratory-scale Xiaochaihu Decoction extraction experiments showed that the model exhibited good fitting performance for both the first and second decoction processes, with R2 values of 0.9904 and 0.9915, respectively, indicating good applicability of the model. In industrial application, the model was successfully applied to the decoction process of five medicinal materials for Xiaochaihu Capsules. The heat transfer performance of Tank 1 was significantly lower than that of other tanks, providing a direction for enterprise equipment maintenance. This study provides a useful method for industrial production data mining in TCM extraction processes. By monitoring changes in fitting results, it is conducive to timely equipment maintenance, ensuring production efficiency and product quality.

Although this model has been validated as effective for ginkgo leaves and the Xiaochaihu formulations, its general applicability and parameter transferability require further investigation. The characteristics of herbal materials, such as particle size and surface area, are closely related to the heat transfer behavior of the decoction system. The overall heat transfer coefficient (H) and convective heat transfer coefficient (h) obtained from fitting the ginkgo leaf system are strongly coupled with its specific material properties and cannot be directly generalized to other types of herbal decoction processes. Follow-up studies need to expand the range of validation samples, clarify the relationship between material properties and heat transfer parameters, and develop a more universally applicable corrected model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G.; Methodology, F.D. and X.G.; Software, F.D.; Validation, F.D.; Formal analysis, F.D.; Investigation, F.D. and X.Z.; Resources, Z.W., X.G. and N.W.; Data curation, F.D.; Writing—original draft, F.D. and X.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.Z., Z.W., X.G. and N.W.; Visualization, F.D.; Supervision, G.W., Z.W., X.G. and N.W.; Project administration, G.W., Z.W., X.G. and N.W.; Funding acquisition, G.W., Z.W. and N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Modern Chinese Medicine Preparations, Ministry of Education, Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant number Zdsys-202301), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number 2024YFC3506900), Key R & D Program Project of Jiangxi Province (Grant number 20243BBI91013).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Z.; Cheng, N.; Zhao, X.; Tao, Y.; Xue, Q.; Gong, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y. Studies on the best production mode of traditional Chinese medicine driven by artificial intelligence and its engineering application. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2025, 50, 3197–3203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.Y.; Rajan, K.S. Microwave assisted extraction of flavonoids from Terminalia bellerica: Study of kinetics and thermodynamics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Methven, L.; Niranjan, K. Modelling extraction kinetics of betalains from freeze dried beetroot powder into aqueous ethanol solutions. J. Food Eng. 2023, 339, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R.; Villa, A.L.; Ribeiro, R.; Rabi, J.A. Pectin Extraction from Mango Peels in Batch Reactor: Dynamic One-Dimensional Modeling and Lattice Boltzmann Simulation. Chem. Prod. Process Model. 2015, 10, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroço, R.F.; Kim, B.; Santacoloma, P.A.; Abildskov, J.; Lee, J.H.; Huusom, J.K. Analysis and model-based optimization of a pectin extraction process. J. Food Eng. 2018, 244, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ding, F.; Qu, H.; Gong, X. Mechanism modeling and application of Salvia miltiorrhiza percolation process. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, K. Dynamic Predictive Control of Traditional Chinese Medicine Extraction Process Based on Digital Twin. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Gao, H.; Wang, K. Temperature Control for Polysaccharide Precipitation in Traditional Chinese Medicine Based on Fuzzy Adaptive PID. Autom. Appl. 2019, 5, 29–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Cheng, W.; Zheng, Y. Temperature Control for Traditional Chinese Medicine Extraction Based on Adaptive Fuzzy PID. Control Eng. China 2009, 16, 527–530. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Kang, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, M. Simulation and Experiment of Temperature Uniformity during Hot Air Drying of Erzhi Pill. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2020, 51, 1226–1232. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Xie, Q.; Li, S. Modeling and Decoupling Control of the Extraction Process in Traditional Chinese Medicine Production. Manuf. Autom. 2013, 35, 47–50+67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; He, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J. Comparative Study on the Extraction Kinetics of Chlorogenic Acid from Lonicera japonica and Lonicera hypoglauca. Chin. J. Inf. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 25, 91–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Ge, L.; Qi, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, H.; Dang, X.; Yang, B.; Ni, J. Study on the Suitability of Kinetic Models for the Extraction of Total Flavonoids from Drynaria Using Water Decoction. J. Beijing Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 37, 121–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Study on the Mechanism and Process Simulation of Enhanced Heat and Mass Transfer in Ultrasound-Coupled Vacuum Drying of Traditional Chinese Medicine Extracts. Ph.D. Thesis, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Yi, B.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Simulation and Experiment of Heat and Mass Transfer during Ultrasound-Assisted Vacuum Drying of Licorice Extract. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2023, 54, 2056–2065. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, M.; Qu, H.; Cheng, Y. Extraction Kinetic Model of Chinese Herbal Medicine Based on Cylindrical Structure. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2006, 9, 1600–1603. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Study on Kinetic Models for Flavonoid Extraction from Five Rhizome Herbs. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, X.; Chen, S.; Fu, H.; Qu, H. Study on Salvia miltiorrhiza Extraction Kinetics Based on Data-Driven and Mechanism Modeling. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2022, 53, 51–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qu, X.; Yang, H. Study on the Decoction Kinetics of Moringa oleifera Leaves Based on Decoction Factors-Multi-component Correlation Analysis. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2022, 47, 4950–4958. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Simulation of Mass and Heat Transfer in Oak Leaves Under Hydrothermal Conditions. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Henan, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lan, J.; Fu, H.; Qu, H.; Gong, X. Energy Conservation and Production Efficiency Enhancement in Herbal Medicine Extraction: Self-Adaptive Decision-Making Boiling Judgment via Acoustic Emission Technology. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.