Abstract

The advancement of miniaturized liquid chromatography (M-LC) systems has drawn considerable attention for their ability to enhance sensitivity, expedite analysis, and minimize the environmental impact of chemical usage in various analytical processes. This review explores the fundamental principles and recent innovations in M-LC technology, including diverse pump designs, advanced column techniques, and the reduction in connection devices. Emphasizing the need for components that operate efficiently at the capillary or nanoscale with minimal dead volumes, we also discuss the development of benchtop instruments and mass spectrometry integrations. The review further highlights the growing applications of M-LC in food, environmental, and biological analyses, highlighting its potential as a powerful and emerging tool in separation science. Looking forward, addressing problems such as limited robustness, fabrication complexity, and integration with sensitive detectors will be instrumental to advancing M-LC technology. Modern innovation in microfabrication, materials science, and hyphenated methods holds great promise for allowing real-time, high-throughput, and portable analytical solutions in the near future.

1. Introduction

1.1. History of Chromatography

The conceptual roots of liquid chromatography (LC) miniaturization can be traced back to 1957–1958, when Martin and Golay introduced the concept of capillary columns in gas chromatography (GC), which laid the theoretical foundation for their later adoption in LC [1]. In 1964, J.C. Giddings proposed the use of capillary columns in LC to improve separation efficiency, marking one of the earliest theoretical advances in miniaturized LC systems [2]. Subsequently, ref. [3] applied 1 mm i.d. columns for the separation of ribonucleotides, a major practical leap forward in column size reduction. From 1973 to 1978, Ishii and colleagues developed 0.5 mm i.d. capillary columns and, importantly, engineered gradient pumps and low-volume ultra-violet detectors specifically designed for capillary formats [4].

In 1976–1884, JASCO introduced commercially available micro-LC systems (FAMILIC-100), further supporting the transition from conventional HPLC to miniaturized LC [5]. Novotny (1978) advanced the field by employing drawn glass capillary columns to conduct high-efficiency separations [6]. Then, in 1981, Jorgenson and Lukacs made a groundbreaking contribution with the introduction of capillary electrochromatography (CEC) using packed columns, setting a milestone for electrically driven miniaturized separations [7].

By 1985–1986, Ishii and Yang had proposed a unified approach to chromatography, envisioning the use of a single column format across GC, LC, and Supercritical fluid chromatography(SFC), reinforcing the convergence of separation sciences [8]. In parallel, MiLiChrome systems, a family of micro-LC instruments, emerged in Russia and gained moderate distribution until the mid-1990s, as noted by Baram et al. in a review of micro-LC innovations [9]. The 1990s and early 2000s saw an explosion of innovation: capillary monolithic columns (both silica and polymeric), chip-based columns, AI-coupled LC detection, and on-chip valves/injection technologies. Table 1 shows the milestones of LC in the past. These advances shaped the modern field of M-LC and chip-LC systems now being used in omics, toxicology, food safety, and environmental science.

Table 1.

Summary of milestones in LC miniaturization.

1.2. Liquid Chromatography

The late 1960s saw the emergence of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), a significant enhancement over classical LC methods [10]. HPLC uses a liquid mobile phase in conjunction with a high-pressure infusion system to achieve separation based on the physical and chemical properties of analytes [11]. It is particularly effective for analyzing organic compounds that exhibit high boiling points, low volatility, large molecular weights, or diverse polarities—factors that limit the applicability of GC [12,13]. Known for its precision, high efficiency, rapid throughput, and broad applicability, HPLC has become the dominant technique in fields such as biochemistry, medicine, food science, and environmental monitoring [12,13]. Its development has also driven innovations in stationary phase materials, detector technology, data processing, and theoretical aspects of chromatography [11].

Moreover, ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) continues to be an important technique characterized by ultra-fast analysis, high-resolution separation, and heightened sensitivity [14,15]. Building on the principles of HPLC, UHPLC incorporates innovations such as sub-2 µm particle packing, reduced system dead volume, and rapid detection methods to enhance flow rates, sensitivity, and chromatographic peak capacity [16]. Compared to HPLC, UHPLC offers improved resolution and significantly reduced analysis times. It is increasingly used in pharmaceutical research, biochemical assays, food safety testing, and environmental analysis [13,16].

1.3. Why Do We Want to Miniaturize Liquid Chromatography?

Although LC technology has advanced significantly over the past six decades, the widespread use of HPLC remains limited in certain contexts due to factors such as bulky instrumentation, high operational costs, and lengthy analysis times [17]. These limitations have spurred interest in the development of new LC-based approaches [18], with system miniaturization emerging as a prominent trend, especially in analytical chemistry [19]. M-LC offers several advantages: higher chromatographic resolution, reduced consumption of samples and organic solvents, and improved reproducibility [20].

As LC systems shrink in size, there is a corresponding miniaturization of analytical columns and continuous innovation in detector technology, which facilitates seamless coupling with mass spectrometry [21].

This review focuses on the recent progress and applications of M-LC over the past decade, particularly in the domains of food safety, environmental monitoring, and biological analysis.

1.4. Why Use M-LC for Food Safety Monitoring, Environmental Tracking, and Biological Analysis?

1.4.1. Food Safety Monitoring

The increasing prevalence of food contamination and its public health implications have made food safety and quality assurance global priorities. M-LC technologies offer effective tools for verifying food authenticity, assessing nutritional and toxicological properties, and detecting contaminants and residues via high-resolution chromatographic data [22,23]. Chip-based M-LC platforms are especially promising, allowing for rapid, on-site screening of food adulterants, toxins, and other hazards—an essential capability in settings with limited laboratory infrastructure [23].

Given the complexity of food matrices, robust analytical methods are required. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometery (LC-MS) is a powerful solution [24], though traditional LC-MS platforms are often expensive and technically demanding. Emerging chip-based LC-MS systems aim to overcome these barriers by offering greater throughput and sensitivity [25], enabling precise detection of nutritional components, veterinary drug residues, and pesticide contaminants in a variety of food products.

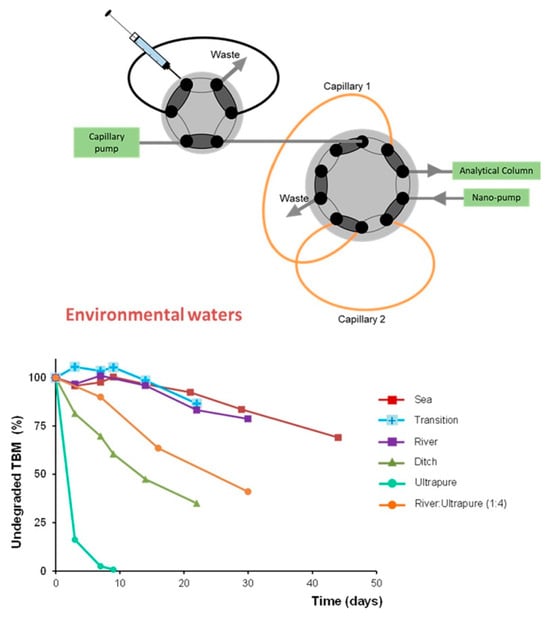

1.4.2. Environmental Analysis

Environmental monitoring represents a critical application area for M-LC systems, particularly for tracking pollutants in aquatic and terrestrial environments. Water samples, in particular, are well suited for M-LC due to their relatively simple matrices, which allow direct injection with minimal risk of column clogging [26,27]. In addition to miniaturized versions of conventional HPLC (e.g., capillary and micro-LC systems), researchers are increasingly exploring the use of microchip-based platforms in place of traditional analytical columns [28,29]. These chip-based LC-MS methods significantly reduce both analysis time and solvent consumption, making them a promising advancement in environmental science [30,31].

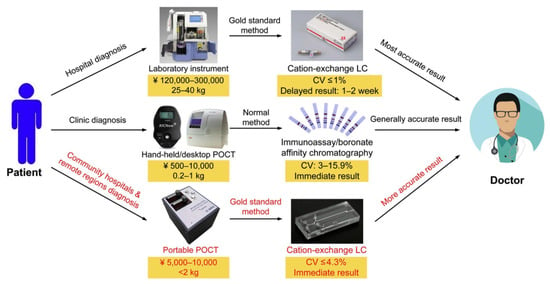

1.4.3. Biological Analysis

Progress in bioanalytical chemistry relies heavily on innovative analytical technologies. LC-MS has established itself as a gold standard in this field, with chip-based LC-MS gaining traction as a more efficient alternative [32,33]. Omics disciplines, particularly proteomics and metabolomics, demand high-resolution and high-throughput platforms [34]. M-LC, especially when integrated with MS, offers enhanced peak resolution, enabling more comprehensive metabolite profiling and quantification [35]. Compared to conventional benchtop instruments, chip-based LC provides notable benefits, including faster analysis, higher sensitivity, reduced band broadening, and increased throughput, making it exceptionally well-suited for complex biological studies [17].

M-LC also plays an important role in advancing the goals of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), particularly through its significant reduction in solvent consumption and improved energy efficiency [36]. M-LC systems, such as capillary LC and nano-LC, operate with extremely low flow rates, often in the nL to mL per minute range, leading to solvent reductions of up to 1000 times compared to traditional LC systems. This not only decreases hazardous waste but also reduces costs and improves laboratory sustainability practices [36,37]. It also shows the integration of high-efficiency columns and water-rich or alternative green solvents (e.g., ethanol, glycerol, deep eutectic solvents) as key trends in greener LC system design [36].

Miniaturized systems use less thermal energy since they have smaller interior volumes and frequently operate at room temperature, which aligns with GAC’s energy efficiency principles. Coupling M-LC with MS or miniaturized detectors allows for real-time and in-process analysis, which are GAC principles centered on pollution reduction and rapid decision-making [36]. However, they acknowledge trade-offs: M-LC systems may face challenges such as reduced sample loading capacity and the need for precise control systems to manage low flow rates. Despite these limitations, M-LC stands out as a promising green technology that minimizes the ecological footprint of chemical analysis while maintaining analytical performance.

2. Development of an M-LC System

The development of M-LC systems presents a multifaceted engineering challenge, demanding innovation across multiple components [38]. Early pioneers laid the foundation for today’s advanced systems, which emphasize high precision, portability, and reduced sample consumption. One of the earliest breakthroughs came in 1986 when Otagawa et al. introduced a portable HPLC system featuring a plunger pump and an electrochemical detector [39], initiating the path toward chromatographic miniaturization. This was followed by Tulchinsky et al. in 1998, who designed an HPLC system compactly housed in an aluminum box, further enhancing its portability and practical functionality [40].

The 2010s witnessed accelerated innovation. In 2015, Ishida et al. proposed an ultra-compact HPLC system integrating a chip module that combined a separation column and an electrochemical detection cell, driven by a compact electric flow pump [41]. This marked a shift toward highly integrated M-LC platforms. In 2017, Lynch et al. developed a system using an electroosmotic flow pump and an interchangeable HPLC cartridge compatible with both UV and MS detection [42], showcasing the adaptability of modern M-LC setups. Around the same time, Chang’s group introduced a series of lightweight, field-deployable LC systems [43]. Their post-2019 models typically measured 20 × 16 × 16 cm, weighed only 1.8 kg, and featured battery-powered electrolysis micropumps (EMPs), LC microchips, and LED-based absorbance detectors—exemplifying miniaturization without sacrificing functionality.

Further developments include Foster et al.’s 2020 portable capillary LC system, which measured 20.1 × 23.1 × 32.0 cm and weighed 7.82 kg [44]. Designed for flexibility, it employed high-pressure syringe pumps (up to 10,000 psi) and supported variable flow rates and column configurations. In 2021, Chatzimichail et al. introduced a hand-portable LC system using 3D-printed components, highlighting the potential of additive manufacturing to produce customizable, low-cost chromatographic instruments [45]. Since 2021, Brett Paull and colleagues have focused on field-deployable LC/MS systems, aiming to deliver laboratory-grade analytical performance in portable formats for on-site pharmaceutical analysis [46,47]. In 2022, Campíns-Falcó’s team developed two lab-built M-LC systems emphasizing user-friendly interfaces and operational versatility [27]. The following year, Svensson et al. integrated a chip-based pressure regulator with fluorescence and MS detection in a chip-HPLC system [21], reflecting on ongoing efforts to improve precision and system compactness. In 2023, Ishida’s group further enhanced chip-based M-LC technology by introducing modular detection units designed to minimize dead volume and boost system efficiency [19].

Commercialization of M-LC began in earnest in 2005 with Yin et al.’s prototype of the HPLC-Chip/MS system from Agilent Technologies [48], setting a precedent for future market-ready designs. Since then, companies such as Sciex-Eksigent [49], Waters [50], and PharmaFluidics [51] have launched robust M-LC products with separation performance comparable to full-scale LC systems. These commercial systems emphasize user-friendly integration, offering stable fluid drives, precise chip-peripheral connectivity, and highly sensitive detectors.

Ultimately, the performance of an M-LC system hinges on the coordinated function of its key components: chips, pumps, columns, detectors, and injectors. Seamless integration among these parts is essential to achieve the high precision, sensitivity, and operational efficiency required for modern analytical applications.

2.1. Microchip

The development and application of analytical microfluidic devices play a critical role in advancing separation science across various domains [52]. M-LC systems, particularly those integrated with MS, are gaining traction due to their ability to consolidate key LC components into a compact, planar architecture [53,54]. This integration reflects a significant trend in analytical chemistry—delivering high-performance analysis while minimizing system footprint.

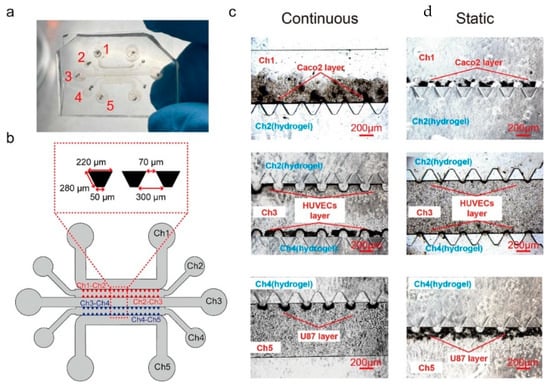

Xing et al. developed a hydrogel-based microchip to model complex physiological barriers, specifically the intestinal barrier and blood–brain barrier, using a combination of alginate and gelatin (Figure 1) [55]. The UV cross-linking improved stability compared to traditional ionic methods. This microchip successfully mimicked the gut–brain axis and allowed in vitro simulation of tryptophan metabolism. LC-MS confirmed realistic levels of tryptophan and kynurenine, demonstrating biological accuracy. Unlike traditional organ-on-chip (OOC) systems, this design avoided porous membranes, supported co-culture of cells and microorganisms, and allowed future integration of organoids or iPSC-derived tissues. The chip demonstrates strong potential for applications in disease modeling, drug screening, and metabolic research.

Figure 1.

Cell morphogenesis in an inoculated microchip. (a) Physical diagram of the microchip after cell inoculation. (b) Illustration of the inoculated chip. (c) Corresponding cell layer on each hydrogel surface after the continuous flow culture. (d) Corresponding cell layer on each hydrogel surface after the static culture. (Scale bar = 200 μm) [55]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [55]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

In summary, the continuous evolution of microchip design is largely driven by the demand for enhanced analytical performance, operational durability, and system versatility in M-LC platforms. Ongoing advances in materials science and microfabrication techniques are expected to further expand the capabilities of chip-based LC systems, opening new frontiers in analytical applications.

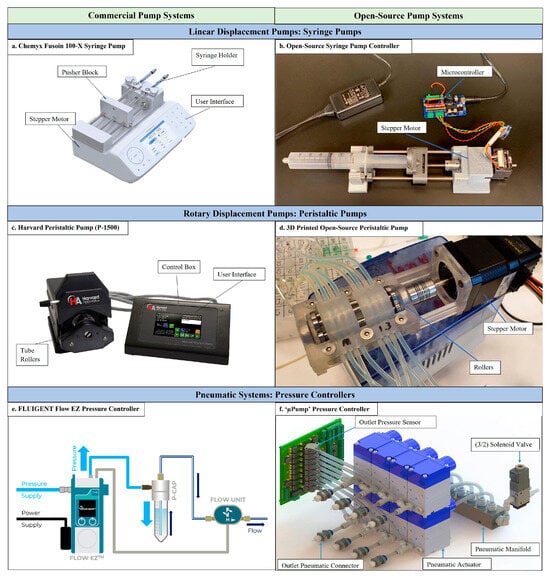

2.2. Pumps

Pumps are essential components of M-LC systems, generating the high pressures required to drive the mobile phase through the chromatographic column [27]. Their design directly impacts the consistency of flow rates, minimization of pulsations, and overall system stability. Various pumping mechanisms have been developed to meet the specific needs of miniaturized systems, including electroosmotic pumps (EOPs), piston pumps, and syringe pumps (Figure 2) [56].

Figure 2.

Commercial and open-source pumping systems. (a) Chemyx syringe pump with embedded electronics; requires the user to input the desired flow rate that is regulated with the help of a stepper motor and pusher block. (b) An open-source syringe pump controlled with the help of a microcontroller, stepper motor, and pushing mechanism. (c) Harvard peristaltic pump with essential control box: requires the user to set the Revolutions Per Minute (RPM) of the motor, which is then translated to the rollers’ speed. (d) A 3D-printed peristaltic pump assembled with the help of a stepper motor and rollers. (e) FLUIGENT pressure controller: requires the user to set the pressure according to the desired flow rate, indicated through the flow sensor. (f) An open-source pressure controller assembled with the help of pneumatic actuators, pressure sensors, and necessary connectors [56]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [56]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

2.2.1. Electroosmotic Pump

EOPs have become increasingly prominent in recent decades, particularly in microanalytical and miniaturized HPLC systems [57]. EOPs generate flow by electroosmosis—moving liquid through a charged porous medium under an applied electric field [19]. This mechanism provides pulse-free flow delivery, it is well-suited for miniaturization, and it supports lab-on-a-chip (LOC) and portable LC systems [58]. Figure 3 shows a flowchart illustrating trends in system miniaturization.

Figure 3.

Flowchart illustrating trends in system miniaturization.

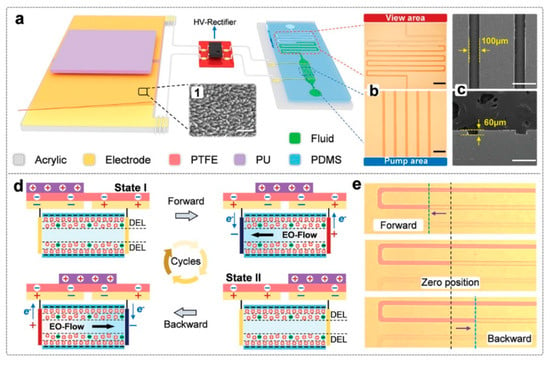

Microfluidic systems frequently use EOPs, but traditional high-voltage sources are large and ineffective because of adverse effects [59]. In order to overcome this, a triboelectricity-driven electroosmotic pump (TEOP) powered by a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) was developed (Figure 4) [60]. Through biomechanical motion, the TEOP produces powerful electric fields that allow for regulated electroosmotic flow. The TEOP achieves ≈600 nL·min−1 flow with significantly lower Joule heating (1.76 J·cm−3·nL−1) than high-voltage sources (≈50 nL·min−1, 8.12 J·cm−3·nL−1). Its efficiency, portability, safety, and low cost make it highly promising for motion-activated micro/nanofluidic transport and manipulation.

Figure 4.

Prototype of the TEOP. (a) 3D schematic diagram of the triboelectricity-driven micro-flow pump composed of a TENG component, high-voltage rectifier module, and microfluidic chip. Inset 1 (scale bar: 1 µm) shows the surface morphology of the tribo-layer. (b) Optical microscopy image of the view area (top) and pump area (bottom) in the microfluidic chip; the widths of the channels are 150 and 100 µm, respectively (scale bar: 1 mm and 500 µm). (c) Electron microscopy image of the pump area; its width and height are 100 and 60 µm, respectively (scale bar, 200 and 100 µm). (d) The step-by-step working mechanism of the EOP works under a full cycle of TENG movement. (e) Photographs of the micro-flow while operating TENG forward and backward [60]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [60]. Copyright 2025, John Wiley and Sons. All rights reserved.

Recent research has focused on enhancing EOP performance for M-LC applications. For instance, nanoporous membranes fabricated using track-etch techniques have shown promise in boosting electroosmotic flow efficiency [61].

In conclusion, while EOPs have demonstrated significant potential, further advancements are required to ensure stable flow rates and reproducible gradient programming prerequisites for commercial adoption in chromatography. As these challenges are addressed, EOPs are expected to become central to next-generation portable analytical systems.

2.2.2. Piston and Syringe Pump

Piston and syringe pumps remain critical in M-LC systems, valued for their pressure stability and flow accuracy [62]. Piston pumps, especially single-piston and double-piston configurations (parallel or serial), have played a foundational role in LC miniaturization [63]. The single-piston design, although simple, enables precise unidirectional flow via check-valve control.

In order to improve automated ambulatory Duodopa pumps for patients with Parkinson’s disease, Pravika et al. [64] conducted a study that proposes the design of a linear electromechanical actuator for use with a positive displacement piston-type medication dispensing syringe pump [64]. A direct current (DC) servo motor with gears powers the electromechanical actuators’ lead screw mechanism, which is intended to guarantee self-locking and stop back-driving. While fault assessments addressed possible mechanical and electrical failures, in silico testing verified improved dynamic responsiveness, stability, and dependability. Frequency response plots used in stability experiments revealed that time delays or inertia mismatches could lead to instability, highlighting the necessity of the ideal DC motor sizing with an inertia ratio near 1:1 for dependable pump operation.

Recent innovations have also improved syringe pump systems. For example, a modular LC platform using syringe pumps demonstrated performance on par with commercial systems, achieving <1.5% relative standard deviation (RSD) for peak area and <0.4% RSD for retention time [65]. Operating at pressures up to 4000 psi, the system utilized capillary columns with sub-3 μm particles and integrated miniature Z-cell detection with deep UV light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and photodiodes. Its open-architecture design, including custom-built control software, allowed flexible configuration and future expansions such as multi-wavelength detection and portable MS integration (Figure 5) [65].

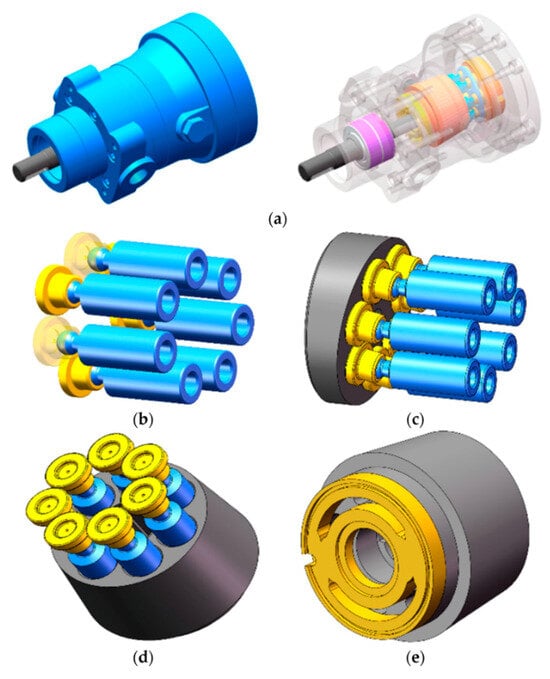

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the structural composition of a piston pump. (a) Three-dimensional structural model of a hydraulic piston pump. (b) Piston ball heads and slippers. (c) Slippers and swashplate. (d) Pistons and piston holes. (e) Cylinder and valve plate [62].

Despite their strengths, size and integration challenges remain. Instrument manufacturers are actively developing more compact and efficient pump designs to meet the increasing demand for M-LC systems [56,66]. These developments are crucial for enabling the next generation of high-performance, field-deployable M-LC platforms.

2.2.3. Constant-Pressure Pump

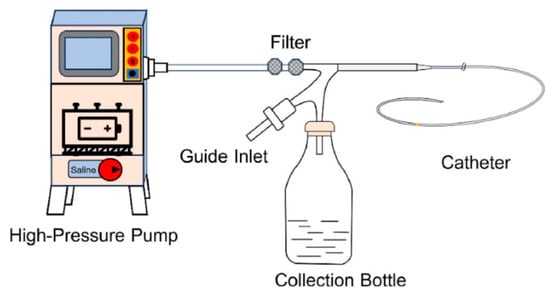

Constant-pressure pumps, also known as pneumatic pumps, utilize compressed gas to deliver the mobile phase at a steady pressure, ensuring consistent flow through the chromatographic column [67]. By maintaining stable pressure, these pumps provide reproducible flow rates, an essential requirement for reliable chromatographic separation. Their ability to suppress flow fluctuations makes them particularly advantageous in applications where even minor deviations in flow can compromise analytical quality and result in reproducibility [68]. Figure 6 shows the Angio-Jet thrombus aspiration system and constant-pressure pump [69].

Figure 6.

Schematic of the Angio-Jet thrombus aspiration system with a constant-pressure pump [69]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [69]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Recently, Bai et al. presented a novel handheld pressure pump using a disposable mini gas cylinder as its pressure source and porous polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) films as flow regulators [70]. This design incorporated multiple parallel PDMS films with varied porosity, thickness, and cross-sectional areas, enabling precise flow modulation by selectively engaging specific branches of the flow circuit. The release of gas was finely controlled, which allowed accurate pressure regulation across the microfluidic network. This compact and lightweight pressure system demonstrated effectiveness in generating concentration gradients and producing emulsion droplets in microfluidic experiments. The authors emphasized its suitability for portable, disposable applications such as point-of-care (POC) diagnostics and analytical workflows in resource-limited settings due to its simplicity, ease of operation, and low cost.

Despite these advantages, constant-pressure pumps are generally less common in LC systems than their constant-flow counterparts. This is mainly due to challenges in maintaining precise, pulse-free flow and generating complex gradients—critical factors for many chromatographic applications [71]. Nonetheless, recent innovations have renewed interest in refining these systems, especially for cost-sensitive and portable LC configurations [68].

In summary, although constant-pressure pumps have not yet been widely adopted in mainstream LC systems, they offer specific benefits such as efficiency, simplicity, and longevity. With ongoing miniaturization and technological improvements, they present a promising direction for future M-LC developments, particularly where affordability and field deployability are prioritized [72].

2.3. Injectors

Injectors are important components in LC systems, directly influencing separation efficiency by reducing void volume, minimizing flow disruption, and ensuring precise sample delivery essential for reproducibility [73]. As M-LC technologies advance, innovations in injector design, particularly at the microfluidic scale, have significantly advanced analytical performance and system integration. Zohouri et al. systematically analyzed how microfluidic droplets can be integrated with separation methods (e.g., LC) to enable minimal sample volume workflows [74]. They showcase the benefits of droplets as discrete carriers (reducing sample diffusion and cross-contamination) but also point out that interfacing droplets with injection modules poses challenges in dead volumes, reproducibility, and pressure matching between droplet modules and separation modules. For instance, droplet-to-column coupling often requires specific valve designs or flow converters to maintain stable transfer without disrupting droplet integrity [74].

On the other hand, Chatzimichail et al. showed that their portable LC system’s 60 nL injection valve yielded retention time RSDs of 0.55 and 0.93% and peak area RSDs of 1.42 and 2.20%, almost matching a benchtop Agilent LC system’s performance, a great example of how careful injector design can deliver robust miniaturized performance in field conditions [45]. The limitations, however, remain: this portable system uses gas-driven pressure (limiting gradient flexibility), and droplet-based interfaces may struggle to maintain uniform droplet transfer under varying backpressure or complex matrices. Regarding quantitative impacts of miniaturization and performance tradeoffs, ref. [74] emphasized that droplet-based microfluidic LC hybrids can minimize sample and solvent consumption by orders of magnitude, e.g., using pico- to nL droplets instead of mL injections, while preserving or enhancing sensitivity via compartmentalization.

These miniaturized workflows also allow higher throughput, since parallel droplet generation and rapid droplet transport reduce dead times. In Chatzimichail et al.’s system, using only 5 µL injections and <150 µL/min flow, they achieved continuous operation (24 h) with a 150 mL solvent reservoir and good retention stability (e.g., 0.09–0.57% RSD in retention). Together, these cases show that miniaturization can bring >90% reductions in reagent use and 3 5× (or more) throughput improvements over classical LC runs (which often require ≥20 µL injections and 20–60 min per run) [45]. However, such gains come with tradeoffs: smaller volumes exacerbate the effects of pressure fluctuations, bubble formation, and coupling inefficiencies, especially when connecting to MS. Ensuring robustness, reproducibility, and seamless MS interfacing remains a central challenge for these systems to become routine in analytical labs.

2.3.1. Chip Injectors

Microfluidic integration has revolutionized injector technology by embedding injection mechanisms directly onto chips, thereby reducing dead volume and enhancing sample precision [75]. In M-LC systems, where stability and miniaturization are paramount, chip injectors are especially valuable for maintaining analytical sensitivity and reducing sample dispersion [45].

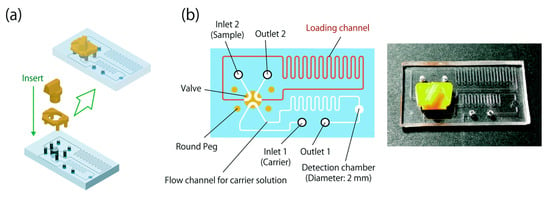

In 2020, Morioka et al. integrated a compact 6-port valve onto a microchip using 3D printing [76]. The manually operated design allowed seamless switching between load and injection modes, supporting sample delivery at flow rates below 100 μL/min. This system performed comparably to commercial injectors and was applied in a hydrogen peroxide assay, achieving a detection limit of 0.5 μM within 100 s post-injection. Its flexibility supports various microfluidic formats, such as microflow injection analysis (μFIA), offering high analytical accuracy and efficient sample handling. The microchip is equipped with a 6-port valve [76] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic of integration of the valve and valve stopper on the microchip. (b) Cross-sectional drawing and photograph of the microchip equipped with the 6-port valve. The dimensions of the valve-equipped microchip are 41 mm in length, 23 mm in width, and 10 mm in height. The channels are 263 μm in width and 105 μm in depth [76].

Despite their benefits, chip injectors face several limitations. These include a susceptibility to clogging from particulate matter, challenges in maintaining steady flow rates, and compatibility issues with aggressive solvents that may degrade common polymeric materials [73]. Moreover, microfabrication costs and limited sample volume capacity restrict their broader applicability [77].

Nevertheless, advances in materials, precision flow control, and device integration continue to expand the utility of chip injectors, particularly in LOC platforms. As these systems evolve, chip injectors are poised to become essential components in next-generation diagnostic and analytical technologies [78].

2.3.2. Valve-Based Injectors

Valve-based injectors are integral to LC systems where precise sample control and consistent delivery are required [79]. Though traditional syringe-based designs remain relevant, modern valve-based systems offer improved reliability, reduced dead volume, and enhanced automation [58]. These are typically categorized into stop-flow and continuous-flow types, both designed to minimize band broadening and maintain chromatographic resolution [80,81].

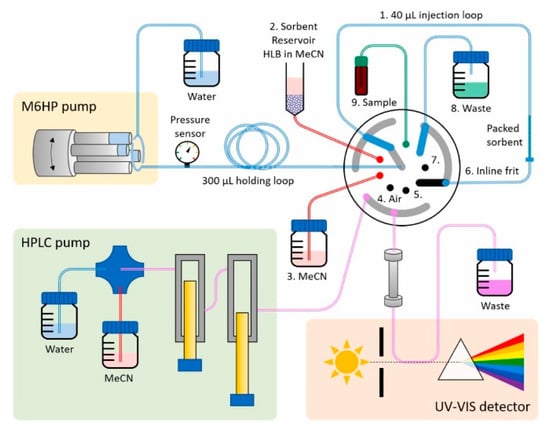

A sophisticated injector was designed by Cocovi-Solberg et al. for the purpose of high-precision sample preparation and solid-phase material packing [80]. The proposed system facilitates (i) accurate loading of sub-milligram quantities of sorbent, (ii) matrix removal during sample loading, (iii) inline analyte transfer via switching valves, and (iv) automated sorbent flushing for renewable bead injection-solid phase extraction. Operating at low pressure (<25 bar), this system is compatible with commercial auto-samplers and provides high throughput (up to 51 samples/hour). Its modular sorbent selection and low solvent usage yield a 250-fold average signal enhancement. Sample volumes up to 3200 μL were processed without peak broadening, outperforming traditional large-volume injection and inline cartridge-based solid phase extraction (SPE) systems. Despite its versatility, the prototype’s pressure tolerance remains a limitation (≤120 bar), driven by the complexity of the flow path. Future improvements may include reducing wetted surfaces to support smaller sorbent particles and higher flow rates suitable for 1 mm ID columns operating at 50 mL/min. Additionally, valve switching introduces challenges in method development, as sample transfer occurs with each cycle through specific valve positions (Figure 8) in the injector prototype [80].

Figure 8.

Illustration of the injector prototype and its fluidic connections. The rotor mechanism links low-pressure pumps and packed columns for precise sample handling. The analytical column (Pursuit 3 PAH, 4.6 × 100 mm, 3 μm (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA)) was operated at 20 °C and 1 mL min−1 using water and MeCN as the mobile phase. The pump aspirates 20 μL of MeCN from position 3, and a part of it is used to resuspend the bead material in position 2, then aspirates the desired bead suspension volume from position 2, and dispenses the train to position 1 [80].

While issues such as clogging, fabrication cost, and solvent compatibility persist, ongoing research and material innovation are steadily improving performance. These injectors are increasingly applicable in emerging areas such as personalized medicine, high-throughput screening, and environmental analysis [82,83]. As integration with microfluidic and M-LC platforms advances, valve-based injectors are positioned to become indispensable tools in future bioanalytical workflows.

2.4. Column

The analytical column is a central component in M-LC, playing a pivotal role in determining separation performance and system efficiency [84]. With increasing demand for high-resolution, low-volume analytical techniques, the development of advanced columns—especially capillary and nanoscale variants—has become essential [85]. Column design must account for multiple factors, including maintaining backpressure within acceptable limits, achieving stable flow rates, ensuring detector compatibility, and minimizing dwell volume [17]. These considerations collectively impact the chromatographic system’s reliability and analytical accuracy [86]. Miniaturized columns generally fall into two categories: open-tube capillary columns (OTCCs) and packed capillary columns [87].

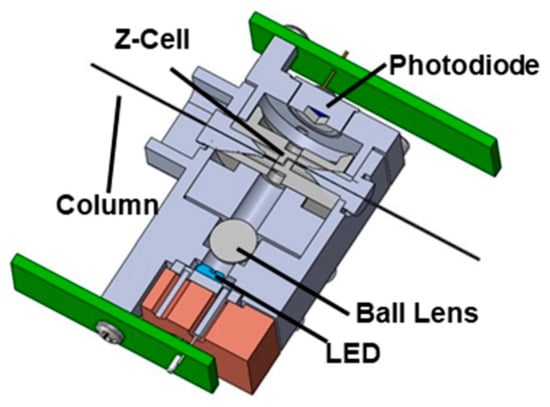

A few years ago, Forster et al. presented work on portable LC systems, a miniature LED-based UV absorption detector built into a capillary column cartridge [82]. Column diameters were raised to 0.2–0.3 mm i.d. to handle the higher flow cell volume compared to the prior on-column version. Comparing kinetic plots across columns with varying lengths, particle sizes, and pressure restrictions revealed theoretical efficiency and achievable chromatographic performance, with smaller particles allowing for faster runs. The technique works best in portable applications when the volume of the mobile phase is constrained by tiny syringe pumps. Future research will optimize the trade-off between analysis time and mobile phase volume in both gradient and isocratic scenarios. Figure 9 shows a UV-absorbance detector with a column [82].

Figure 9.

Schematic of a new UV-absorbance detector module for use in a capillary column cartridge. Light from a UV-LED source is focused through a Z-shaped flow cell with a ball lens. Transmitted light is then detected by a photodiode on the opposite end of the detector flow cell optical path [82]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [82]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

However, miniaturized columns face specific challenges. These include reduced efficiency due to shorter lengths, lower sample capacity, and difficulties in achieving uniform particle packing [88]. The use of small particles to enhance resolution often leads to high backpressures-difficult to manage in compact systems. Additionally, precision manufacturing increases cost and fragility, while dead volume, solvent incompatibility, and inadequate thermal control further limit performance [89]. Low analyte volumes reduce detection sensitivity, and inconsistencies in fabrication processes can impair reproducibility [90]. Table 2 illustrates the different dimensions used in M-LC columns.

Table 2.

Dimensions of columns used in M-LC.

Emerging technologies such as 3D printing offer promising solutions. Three-dimensional printing enables custom column designs, reduces dead volume by integrating columns directly into microfluidic chips, and improves material compatibility and robustness [94]. It also lowers manufacturing costs, enhances reproducibility, and offers better mechanical and thermal stability-making M-LC more feasible for real-world applications, including on-site antibiotic detection in food matrices [95].

Recent advancements in micro-capillary column fabrication, such as the slurry packing of fused silica particles, have further improved column uniformity, which is vital for boosting separation efficiency and analytical reproducibility [84]. As material science and fabrication techniques continue to evolve, miniaturized columns are expected to deliver performance on par with, or superior to, their conventional counterparts—paving the way for broader adoption of M-LC across disciplines.

2.4.1. Packed Capillary Column

Packed capillary columns offer several advantages in M-LC systems. Their primary benefit lies in delivering high separation efficiency while consuming minimal amounts of sample and solvent [82]. Given that M-LC inherently operates with small sample volumes, packed capillary columns are especially suited for high-throughput applications [96]. When filled with fine particle materials, these columns can achieve exceptional resolution. Their narrow inner diameters reduce analyte diffusion, resulting in sharper peaks and more precise separations [26].

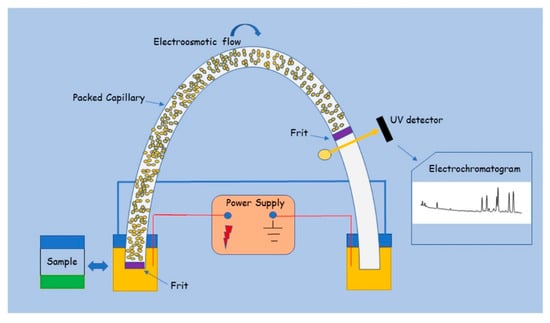

Recently, Fanali & D’Orazio et al. presented a tutorial of capillary electrochromatography for UV and MS techniques for enantiomer separation employing packed capillaries with silica–vancomycin stationary phase [97]. It describes the instrumentation, chiral stationary phase synthesis, and coupling of CEC with MS via a liquid junction interface, which provided high sensitivity. The chiral stationary phase synthesis showed strong enantio-separation and chemo-selectivity, and its practical applicability was demonstrated through analysis of plasma samples from patients undergoing venlafaxine therapy. CEC was displayed with a detector [97] (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Scheme of a CEC instrumentation where a UV detector is used [97]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [97]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Despite these advantages, packed capillary columns present several technical challenges in M-LC contexts. One of the main limitations is the difficulty in achieving uniform packing within such narrow columns [98]. Uneven packing can result in channeling and inconsistent flow distribution, leading to reduced separation performance and reproducibility [97]. Furthermore, the use of fine particles generates high backpressures due to the small internal diameter, which imposes significant mechanical stress on system components—particularly pumps—and may reduce overall system longevity [17].

To address these issues, recent innovations have focused on improving column packing technologies and materials. Notably, the use of sub-2 µm particles and highly porous stationary phases has enabled enhanced separation efficiency while keeping backpressure at manageable levels [82].

As fabrication techniques continue to improve and as new materials and column architectures are developed, packed capillary columns are expected to play a foundational role in the evolution of high-efficiency, low-volume M-LC systems.

2.4.2. Particle-Packed Capillary Column

In particle-packed capillary columns, the size and uniformity of the packing particles are key determinants of chromatographic performance [99,100]. Recent innovations have focused on optimizing particle sizes in the range of 1.7 to 5 µm, with sub-2 µm particles gaining attention for their superior separation efficiency and improved peak resolution [34,100]. These smaller particles increase surface area and promote stronger analyte-stationary phase interactions, yielding sharper chromatographic peaks. However, this improvement comes at the cost of significantly higher backpressure, which necessitates robust and pressure-resistant system components [85].

Conversely, particle sizes in the range of 3–5 µm remain widely used for applications where lower backpressure and enhanced system robustness are prioritized over ultra-high resolution [35]. These particles offer longer operational life and are better suited for high-throughput or routine analyses.

Takuya Kubo & Toyohiro Naitoa et al. prepared a packed-bed particle model within a microfluidic LC column to quantitatively assess the impact of structural design on band broadening [84]. Si-quartz columns with integrated on-column detection were fabricated to test various structural parameters. The study found that columns with minimal variation in structural size distribution exhibited the least band broadening. Additionally, micro-columns featuring duplicated pillar size patterns demonstrated that lower duplication frequency yielded better separation performance by reducing peak dispersion at transition zones between different regions. Further, the influence of void ratio—related to packing density—was evaluated. While columns with higher void ratios exhibited more band broadening, this factor was found to have a smaller effect compared to the impact of structural size distribution. Figure 11 shows a schematic of columns integrated with Si-quartz [84]. These results provide a detailed understanding of how microstructural homogeneity and packing density affect chromatographic efficiency in particle-packed capillary systems.

Figure 11.

Preparation of Si-Q columns [84]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [84]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Despite their many advantages, particle-packed capillary columns face technical limitations. High backpressure remains a critical issue, especially in M-LC systems where pump capacities are limited [16,89]. Uniform particle packing at micro-scales is also difficult to achieve, and any inconsistencies may lead to channeling or uneven flow, degrading column performance. Moreover, the narrow internal diameter limits sample loading capacity, which can be a constraint in higher-throughput applications [101]. These columns also tend to be fragile, making them prone to damage during handling and operation.

To address these challenges, several recent innovations have emerged: 3D printing of column hardware has enabled precise fabrication of custom geometries and integrated fluidic connectors, reduced dead volume, and improved packing consistency [102,103]. Hybrid particle technologies, combining silica and polymeric materials, have expanded chemical stability and pH compatibility [89]. Nanofabrication techniques, such as electrostatic deposition, ensure uniform particle placement and reduce channeling effects [104]. Advanced surface functionalization, including zwitterionic coatings, has enhanced selectivity—particularly for polar analytes—broadening the applicability of these columns across various separation challenges [105].

2.4.3. Monolithic Packed Capillary Column

Monolithic packed capillary columns have emerged as critical components in M-LC, offering high separation efficiency and structural versatility across various analytical applications [106]. Their continuous porous architecture—formed in situ—distinguishes them from traditional particle-packed columns by eliminating interstitial voids and enabling improved mass transfer and lower backpressure [107,108]. These properties make monolithic columns particularly suitable for complex analyses in proteomics, environmental science, and biomedical research [109].

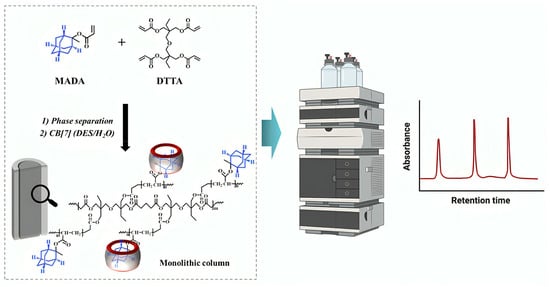

W. Li et al. recently developed a monolith using thermally induced free radical polymerization with phase separation, a porous copolymerization of 2-methyladamantan-2-yl acrylate (MADA) with ditrimethylolpropane tetraacrylate (DTTA) in fused silica. The prepared poly (MADA-co-DTTA) monolith showed adjustable permeability, developed porous structure and high thermal stability [106]. Porous structure, permeability, and surface area were optimized by modifying the reaction conditions and prepolymerization content. The monolith exhibited great thermal stability from crosslinking and increased hydrophobicity because of the adamantyl groups. It performed exceptionally well in the separation of biological materials and small molecules (PAHs, alkylbenzenes). Additionally, host-guest interactions immobilized cucurbituril (CB) onto the monolith, and capillary- LC (cLC), cLC-MS/MS analysis verified that CB could control column hydrophobicity. In order to accommodate increasingly complicated samples, this approach raises the possibility of dynamically tuning monolithic columns in the future, utilizing various host-guest systems. Schematic of monolithic column design [106] (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Overview of a monolithic column design, highlighting its open, interconnected pore structure and high-speed separation capability [106]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [106]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Typically fabricated from organic polymers or silica-based materials, monolithic columns can be tailored for specific separation targets [34]. Recent advancements in additive manufacturing, particularly 3D printing, have expanded design possibilities by enabling precise control over pore geometry and distribution [110,111]. As a result, these columns can achieve plate numbers between 50,000 and 100,000 plates per meter, depending on material selection and analyte interactions [106]. Incorporation of nanomaterials has further enhanced the functionality of monolithic columns. Metallic nanoparticles—such as gold or silver—embedded within the monolith matrix improve selectivity and introduce catalytic properties, expanding the column’s utility in biomolecular analysis, including proteomics and glycomics [107,112].

Despite their advantages, monolithic packed capillary columns face limitations that hinder broader adoption. Fabrication reproducibility remains a challenge, particularly in achieving consistent pore structures and functionalization across batches [105]. Such variability can affect analytical reliability and complicate method standardization. Furthermore, commercial availability is still limited; monolithic columns are not as widely produced or distributed as traditional packed columns, restricting their use in routine laboratory workflows [34].

Nevertheless, monolithic packed columns represent a substantial advancement in column technology. Their low backpressure, ease of integration with microfluidic platforms, and compatibility with advanced materials such as nanoparticles and 3D-printed frameworks make them ideal candidates for next-generation M-LC systems. Future research is focusing on areas such as stimuli-responsive materials for smart separation control, sustainable and scalable fabrication methods, and computational modeling for precision column design. With continued innovations in materials science and microfabrication, monolithic capillary columns are poised to play an increasingly important role in advancing the performance, reliability, and accessibility of M-LC technologies.

2.4.4. Open Tubular Capillary Column

OTCCs play a critical role in M-LC, offering advantages in efficiency, speed, and flow dynamics due to their unique structure [113]. Unlike packed or monolithic columns, OTCCs consist of a thin stationary phase coating applied to the inner wall of the capillary. This design eliminates packing material, enhancing permeability and reducing backpressure—ideal for fast, high-resolution separations in proteomics, pharmaceutical analysis, and complex sample workflows [114].

Stationary phases in OTCCs may be porous or non-porous, with film thicknesses ranging from 0.1 µm to several micrometers [115]. Non-porous coatings provide uniform analyte interaction surfaces, while porous films—incorporating materials like silica or metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)—offer greater selectivity and retention [115]. Recent advances from 2022 to 2024 introduced hybrid stationary phases (e.g., silica-polymer composites, carbon-based nanomaterials) that enhance chemical robustness and analyte-specific interactions [116].

Though OTCCs are not packed with particles, the stationary phase porosity and surface structure play crucial roles in determining peak sharpness and resolution [117]. Their inner diameters typically range from 10 to 100 µm, with column lengths spanning from 10 cm to over 1 m [118,119], offering broad application flexibility.

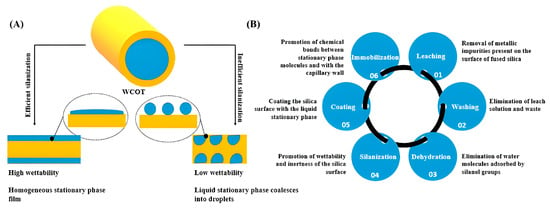

A study by Santos et al. evaluated key parameters of wall-coated open tubular (WCOT) columns within nano-LC- Electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS systems. Parameters such as stationary phase composition, column length, and flow rate were optimized [92]. While WCOT columns demonstrated strong intrinsic separation capabilities, especially when combined with trapping columns, issues like film detachment and clogging remain challenges. The findings underscore the potential of WCOT columns as competitive tools in M-LC, with further research required to address fabrication and reliability concerns. Figure 13 shows the development of WCOT columns [92].

Figure 13.

(A) The difference in the silica surface’s coating with the liquid stationary phase depends on the wettability profile; (B) summary of the steps involved in developing WCOT columns and their respective functions [92].

Despite recent improvements, OTCCs face limitations in fabrication reproducibility, stationary phase uniformity, and limited sample capacity. These restrict their use in high-throughput or preparative workflows [115]. However, their unique advantages—especially in speed and selectivity—make them a compelling choice for advanced analytical applications. Continued innovation in materials science and thin-film deposition will be key to realizing their full potential.

2.4.5. Chip-Based Column

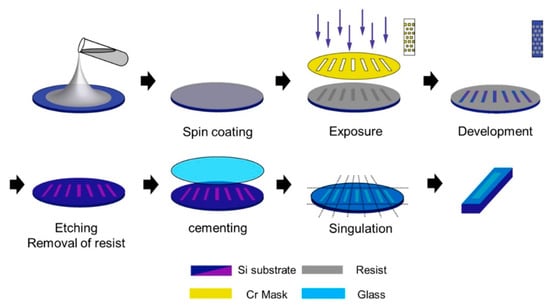

Chip-based columns represent a groundbreaking development in M-LC, integrating chromatographic functionality directly into LOC systems [120]. Fabricated using microfluidic technologies, these columns offer unmatched precision, low sample consumption, and rapid analysis times—particularly beneficial for proteomics, diagnostics, and pharmaceutical analysis [121]. Materials used for chip-based columns include silicon, glass, and various polymers [122]. Recent advancements have introduced hybrid substrates such as cyclic olefin copolymers and engineered thermoplastics to improve solvent resistance and structural durability [123]. Fabrication methods—photolithography, laser etching, and 3D printing—allow for precise control over microchannel geometry, stationary phase integration, and multi-modal system compatibility [120,124,125]. Table 3 shows a comparison of several types of M-LC systems.

Table 3.

Comparison of M-LC Systems.

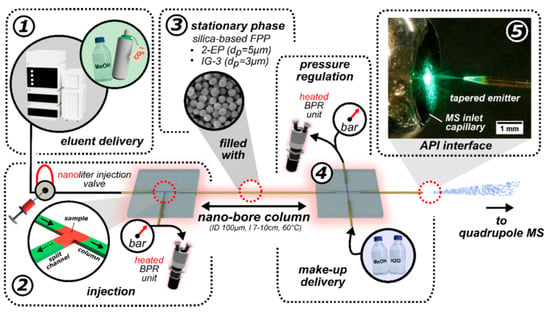

In a representative study, Weise et al. reported a chip-based nano supercritical fluid chromatography MS (NanoSFC-MS) system [124]. This modular device included a packed nanobore column between two laser-etched chip modules: a pre-column microtee for sample injection and a post-column micro-cross for coupling to atmospheric pressure MS via a split-flow interface. The system enabled rapid separations of vitamins and chiral compounds in seconds, demonstrating excellent speed, efficiency, and pressure regulation. Figure 14 shows the NanoSFC setup [124].

Figure 14.

Schematic illustration of the NanoSFC-MS setup, detailing pump, column, interface, and pressure sensor integration. An external nano-injection valve (C74MPKH-4674, VICI, Switzerland) with a 5 nL sample loop was installed between the solvent delivery system and the modular nano-SFC system. The proposed post-column chip module with the micro-cross structure was evaluated using a fluorescent sample (7-amino-4-methyl coumarin, c120, c = 500 μM dissolved in MeOH for the imaging, c = 100 μM for FLD measurements) [124].

Despite these advances, chip-based columns face limitations. Fabrication consistency and channel reproducibility can impact separation reliability [130]. Small sample capacities limit their use in high-throughput or preparative contexts [131], and the high cost of specialized instrumentation can deter widespread adoption [132]. Additionally, polymer-based chips may degrade under harsh chemical or thermal conditions [133].

Nonetheless, chip-based columns are transforming the M-LC landscape. Their high integration potential, customizable designs, and compatibility with advanced detection systems position them at the forefront of analytical innovation. As fabrication technologies mature and costs decrease, their adoption is expected to grow across disciplines—from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics.

2.5. Detector

Detectors are critical components of M-LC systems, serving to identify and quantify analytes after chromatographic separation [134]. In M-LC, detectors must be appropriately miniaturized to preserve the system’s compact form while maximizing detectability, resolution, and analytical efficiency [27]. Common detector types include absorbance detectors, also known as LEDs, laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), and electrochemical detectors (ECDs) [135]. These are often tailored for specific compound classes but can be adapted for broader analyte detection through optical, electrochemical, or signal-processing modifications [135]. Recent advancements have significantly enhanced detector sensitivity, compactness, and integration, enabling more versatile and portable LC systems [136].

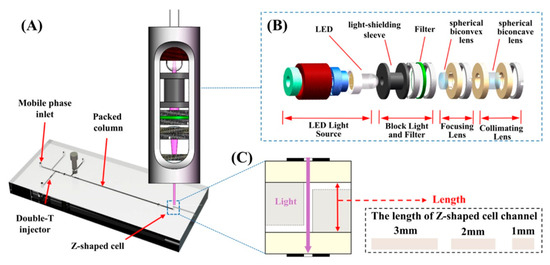

A study was conducted by Jiao, Zhang, Wang, et al., where a miniaturized detector integrated with a microfluidic chip for use in portable LC platforms was developed and then reported by [54]. The system incorporates an LED light source and compact optical components within a light-shielding sleeve, allowing easy adjustment and alignment. The microfluidic chip, constructed from three layers of Poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) features a Z-shaped detection cell in the middle layer—designed to maximize the optical path length and improve sensitivity. To reduce stray light interference, dual slits were applied to the chip surface, maintaining interference at a low 0.08%. Moreover, the Z-shaped cell design helped mitigate optical scattering caused by substrate surface roughness. This detector was successfully coupled with microchips employing different stationary phases, supporting both ion-exchange and reversed-phase LC configurations. The integrated system was used to detect metabolic markers such as glycated hemoglobin and bilirubin, demonstrating strong potential for non-invasive chronic disease screening, including diabetes and liver disorders. The LC system with a detector [54] is shown below (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

(A) Schematic diagram of the LC system composed of a microfluidic chip composed of three layers of PMMA and a miniaturized detector. (B) Cross-sectional view of the miniaturized detector, including LED light source, black light-shielding sleeve, filter, spherical biconvex lens, and spherical biconcave lens. (C) A Z-shaped detection unit was processed on the middle layer chip, and the length of the Z-shaped detection unit varies with the thickness of the middle layer chip. Three lengths of 1, 2, and 3 mm were designed, making the volume of the detection cell 0.2826, 0.5652, and 0.8478 µL, respectively, which is necessary to determine the optimal path length [54]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [54]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Recent advances in detector integration within M-LC systems have significantly improved analytical performance, but limitations remain. For example, Svensson et al. demonstrated that coupling chipHPLC systems with microchip pressure regulators enabled robust pressure control at the nanoflow level, which is essential for stable operation of miniaturized detectors such as UV and MS interfaces [21]. Their system achieved a stable flow rate of 400 nL/min and reproducible peak retention times with RSDs below 2%, showcasing improved reliability. However, they also noted that reproducibility was compromised at high backpressures due to the fragility of microfluidic connections, especially when interfacing with ESI-MS. Hemida et al. further emphasized challenges in coupling M-LC with mass spectrometry, particularly in chip-based LC-MS applications. While their low-footprint system enabled online MS-based reaction monitoring with rapid cycle times (<1 min), they reported that miniaturized interfaces remain prone to clogging, dead volume effects, and signal suppression due to inconsistent electrospray formation. These findings highlight the progress in precision and miniaturization while exposing reproducibility, pressure instability, and MS compatibility as ongoing technical hurdles in detector integration [47].

Miniaturization has significantly enhanced LC by reducing sample and solvent consumption, improving throughput, and lowering detection limits. According to Zheng Li et al., microfluidic chips used for nucleic acid diagnostics achieved sample volumes as low as 0.5 nL, a stark contrast to the 10–100 µL typically required in conventional LC [136].

Recent innovations in microfluidic chip-based nucleic acid detection platforms have achieved remarkable sensitivity. For instance, a CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) biosensor enabled detection of HIV-1 dsDNA with a limit of detection (LOD) as low as 0.3 fM (femtomolar), demonstrating strong clinical potential for ultrasensitive diagnostics [137]. These systems often integrate sample preparation, amplification, and detection within a compact format, contributing to improved specificity and automation in molecular diagnostics.

Hemida et al. reported that their compact LC-MS platform consumed less than 100 µL of solvent per run, achieved detection limits below 0.5 ng/mL, and supported automated throughput with analysis times under 2 min per sample [47]. This represents a 3–5× increase in throughput and up to a 95% reduction in solvent usage compared to traditional systems. Such quantitative improvements confirm the environmental and operational advantages of M-LC systems while also suggesting their readiness for high-frequency applications in pharmaceutical and diagnostic workflows.

To overcome these limitations, researchers are pursuing several strategies. Hybrid detection systems that integrate UV-Vis and fluorescence modalities, offering broader detection capabilities [138]. Machine learning (ML) algorithms to reduce noise and enhance signal quality in real time [134]. Advanced materials, such as self-cleaning electrodes for ECDs, are needed to improve robustness and reduce maintenance [139]. As detection technologies continue to evolve, the integration of smart detectors into M-LC systems will play a critical role in expanding their accessibility, functionality, and application scope—particularly for POC diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and resource-limited analytical contexts.

2.5.1. Absorbance Detector

Absorbance detectors have significantly advanced the analytical capabilities of M-LC, enabling accurate quantification of analytes at low concentrations [17]. These detectors are vital in pharmaceutical, environmental, and biochemical analysis, offering rapid and precise compound detection [58]. The miniaturization of absorbance detectors has extended their utility to portable systems, enabling on-site analysis, reducing sample degradation, and improving response times [140]. A major driver of this evolution is the use of LEDs, which offer compact size, low power consumption, high stability, and long operational lifespans, which are characteristics ideal for integration into portable M-LC systems [141].

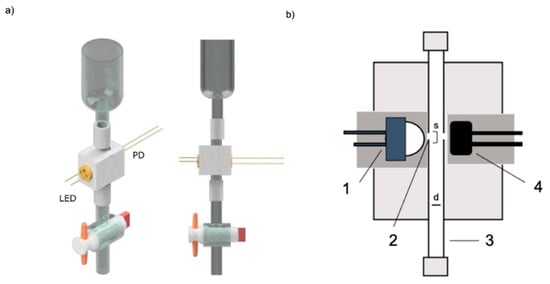

In a compelling application, Prado et al. successfully displayed the application of an easy, cost-effective UV detector with the use of a 280 nm LED [142]. They made a 3D-printed structure and incorporated a custom-made quartz tube, which enabled in-flow absorbance measurements during the elution process in classical column chromatography. Combining an LED and a photodiode allowed for the establishment of a simple setup that massively reduces device costs. This detector showed that it allows real-time monitoring of elution, can facilitate the collection of UV-absorbing compounds, and also decreases the overall experimental time. Hence, by using this method and the potential use of multiple deep-UV LEDs, they predicted an efficient and affordable answer for monitoring the elution of non-colored compounds in column chromatography. Model of an LED [142] (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

(a) 3D rendered models of the proposed LED-based absorbance detector for column chromatog-raphy; (b) Cross-sectional design of the assembled detector: (1) UV-LED in positioning stage (3 mm to the slit), (2) optical slit (1.5 mm diameter), (3) quartz tube with internal diameter (d) of 3 mm, (4) signal photodiode in positioning stage (3 mm to the slit) [142]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [142]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

While LED and LIF detectors have substantially enhanced the analytical power of M-LC systems, several challenges remain. For UV-visible absorbance detectors, sensitivity is strongly tied to optical path length, which is constrained by miniaturization. Moreover, stray light and electronic noise can compromise signal quality and measurement accuracy [143].

To address these limitations, advanced microchip-based absorbance detectors now incorporate Z-shaped flow cells, optical slits, and collimating microlenses to extend the optical path and minimize stray light interference [144]. These advancements enhance the sensitivity [145], reproducibility [146], and overall performance while maintaining a compact footprint. Furthermore, the introduction of multi-wavelength programmable detectors has enabled simultaneous detection of multiple analytes, improving analytical efficiency and reducing instrument cost [147]. As a result, absorbance detectors have broadened the scope of M-LC applications, from pharmaceutical quality control [148] to in situ environmental monitoring [143].

Overall, absorbance detection in M-LC systems continues to evolve through material innovation, optical engineering, and miniaturized design integration, solidifying its role in portable, high-efficiency analytical platforms.

2.5.2. Electrochemical Detectors

ECDs have become integral to M-LC systems due to their high sensitivity, versatility, and adaptability to portable formats [129]. ECDs are particularly effective for detecting electrochemically active compounds that undergo redox reactions at the electrode surface [134]. This makes them highly suitable for the analysis of a wide range of substances, including organic molecules, trace metals, and bioactive compounds with electrochemical properties [149].

An ECD typically consists of three electrodes: a working electrode (the site of redox reactions), a reference electrode (maintains a stable potential for accurate measurement), and a counter electrode (completes the electrical circuit) [150,151,152,153]. Common electrode materials include platinum, gold, glassy carbon, and carbon composites [154]. Platinum and gold are particularly favored for their superior conductivity and corrosion resistance, which ensure stable performance even in chemically harsh environments frequently encountered in M-LC [155,156].

Krishnamurthy et al. developed a new electrochemical sensor based on screen-printed electrodes, modified with carbon-supported platinum and gold, in order to detect the benzenediol isomers catechol, hydroquinone, and resorcinol in acidic environments [157]. Chronoamperometry, differential pulse voltammetry, and cyclic voltammetry were used for detection. While differential pulse voltammetry enabled the simultaneous detection of several analytes by differentiating their oxidation potentials, cyclic voltammetry allowed for the identification of individual isomers. Chronoamperometry was used in the determination of the quantification limits, which were proven to be reproducible across two potentiostats and reached 1 mM for catechol and hydroquinone and 100 nM for resorcinol. The results highlighted the potential of modified screen-printed electrodes for monitoring volatile toxic organic compounds in acidic settings by showing that they can offer a quick, easy, and affordable platform for benzenediol detection. Figure 17 shows a general description of a screen-printed electrode, where the critical elements are shown and explained [157].

Figure 17.

Scheme of sensing volatile toxic organic compounds in air and water using modified screen-printed electrodes [157]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [157]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

The integration of ECDs has significantly advanced analytical chemistry by enabling ultrasensitive detection of low-concentration analytes, supporting analysis in complex matrices such as biofluids or environmental samples [157], and facilitating cost-effective and portable on-site monitoring systems [158]. ECDs are also well-suited for miniaturization and battery-powered operation, aligning with the trend toward decentralized, POC diagnostics and field-deployable analytical tools [158].

In summary, the ECD continues to expand the utility of M-LC systems across biomedical, pharmaceutical, and environmental domains. With ongoing innovations in electrode design, microfabrication, and integration, ECDs are expected to play an even more pivotal role in next-generation analytical platforms.

2.5.3. Miniaturized Mass Spectrometer

Miniaturized MS have become increasingly prominent in the context of M-LC, driven by advancements in microfluidics, compact instrument design, and analytical methodologies [159,160]. These devices harness the core strengths of MS, including high sensitivity, broad molecular detection range, and precise compound identification, while adapting them to portable, low-footprint formats [104,119]. As a result, miniaturized MS systems are revolutionizing clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical analysis by enabling analyses to occur directly at the point of need [161]. Progress in ionization techniques has played a pivotal role in the integration of MS with M-LC. Methods such as electrospray ionization (ESI) and ambient ionization are particularly well-suited for compact systems [162]. These soft ionization approaches preserve molecular structures, making them ideal for analyzing complex biological or labile compounds without excessive fragmentation.

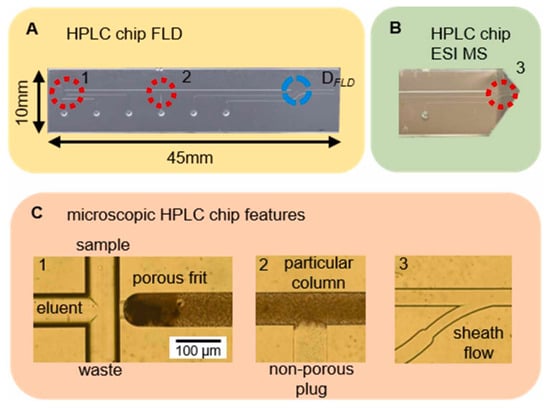

Svensson et al. successfully developed a chip-based pressure regulator (chipPR) integrated into a chip-HPLC system, which was further coupled with fluorescence detection and MS for various analytical applications [21]. This chipPR utilized temperature-controlled restriction for precise flow gradient generation and pinched injections, significantly reducing system complexity. The enhanced portability and integration enabled by chipPR modules make these systems more suitable for field-deployable and POC applications. The chip is composed of an injection cross, a separation channel with a packed column, and a post-column section with two outgoing channels, illustrated in Figure 18, where one could be used to introduce an additional sheath flow for MS-hyphenation [21].

Figure 18.

Overview of HPLC chips and their microscopic features. (A) A fusion-bonded borosilicate-based HPLC chip (45 × 10 × 1.1 mm) was used for fluorescence measurements; detection took place directly after the microcolumn (DFLD). (B) Modified chipHPLC interface for ESI-MS; in here a ground hydrophobized chip-based electrospray emitter is shown. (C) Insight into microscopic chip features: (1) Injection cross and column head. (2) Pressure-tight sealing of the microcolumn. (3) Sheath flow channel merging into the post-column channel prior to the emitter [21].

Despite their many advantages, miniaturized MS systems face challenges, including limited resolution and mass range compared to their full-sized counterparts [163,164]. The trade-offs between performance and portability mean that these systems may not always be suitable for highly complex or large-scale analyses [165]. Additionally, maintaining a stable vacuum in a compact form factor and ensuring consistent ionization can be technically demanding [166].

Recent breakthroughs are addressing these challenges. Innovations such as energy-efficient ion traps and hybrid mass analyzers (e.g., combining quadrupole and time-of-flight) have improved resolution, scan speed, and dynamic range in compact formats [167]. These innovations allow miniaturized MS systems to achieve higher resolution and faster scan speeds [167]. Additionally, wireless communication integration has enabled real-time data transmission and remote access, expanding the utility of miniaturized MS in collaborative research and decentralized diagnostics [168].

In summary, the evolution of miniaturized MS systems is central to the future of portable analytical science. As performance continues to improve and integration with microfluidic M-LC platforms advances, these systems are poised to become core components in flexible, POC, and on-site analytical solutions across diverse scientific fields.

3. Application

3.1. Food Analysis

3.1.1. Toxins

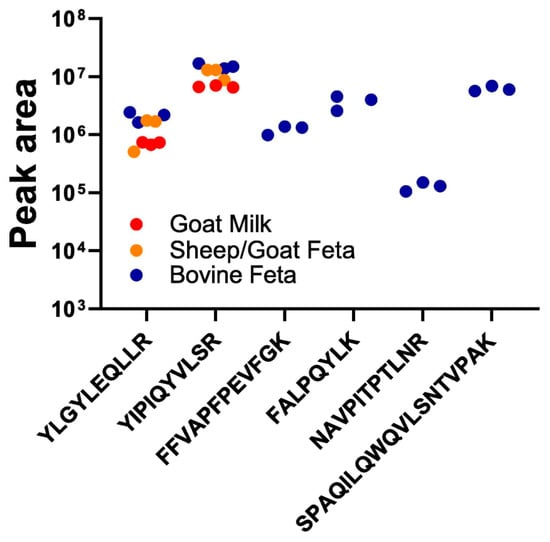

M-LC has emerged as a powerful approach for toxin analysis, offering advantages such as reduced matrix effects and lower analyte dilution in the mobile phase. These benefits enhance signal intensity in concentration-dependent detectors like ESI-MS [169,170].

A study conducted by Chen, Liu, et al. established a fast and automated approach for determining aflatoxins (aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2) in peanut oil [171]. An SPE-based microfluidic chip and MS (SPE-Chip-MS) were presented. Aflatoxins were enhanced in the SPE channel of a microfluidic chip filled with HP C18 particles, then eluted and put into the MS for qualitative and quantitative analysis using multiple reaction monitoring mode. ESI in the positive ion mode was employed to detect aflatoxins. The SPE-Chip-MS system produced a series of good linear calibration curves with a linear range of 1.25 ng/mL to 100 ng/mL, and the detection limits (S/N = 3) of aflatoxins were 0.013–0.067 ng/mL. During this study, the sample pretreatment was entirely incorporated into a microfluidic chip for the first time, and online MS detection was performed; this technology might be extended to detect a variety of food samples.

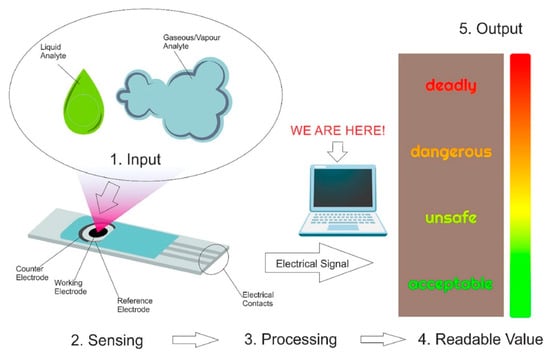

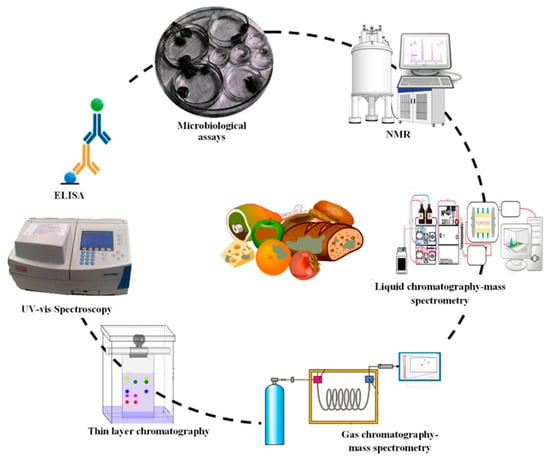

Currently, there are many specific and well-established conventional techniques used on a regular basis for food safety assessment and regulation. These techniques are often specific, but they may have limitations in terms of speed, sensitivity, and ability to detect a wide range of toxins (Figure 19) [172].

Figure 19.

Schematic representation of various methods used for the detection of food toxins [172].

The shift from technical miniaturization in LC systems to real-world toxin detection is underpinned by advancements that directly enhance analytical performance. The incorporation of microfluidic components such as low-dead-volume injectors and integrated fluorescence sensors has enabled high sensitivity, particularly valuable in agri-food and environmental monitoring. According to Fakayode et al., fluorescent chemical sensors have achieved detection limits as low as 0.1 nM for toxins such as mycotoxins and aflatoxins in grain and dairy products, a level of precision significantly supported by M-LC platforms [169]. These sensors, when integrated into chip-based LC systems, allow real-time, label-free toxin quantification in complex matrices with minimal sample volumes. Complementing this, Ahuja et al. report that coupling M-LC to tandem MS allows marine toxin detection (e.g., domoic acid, saxitoxin) with limits below 1 µg/kg, showing clear gains in sensitivity, selectivity, and sample economy [172]. Together, these examples highlight how M-LC advances from channel geometry to optical detection coupling, which are not merely technical feats but critical enablers of high-performance toxin analysis in applied fields.

Looking ahead, the trajectory of M-LC strongly favors integration with intelligent technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), sensor fusion, and mobile diagnostics. Shi et al. described how ambient ionization MS paired with portable M-LC enables field-ready analysis of food and environmental toxins without laborious sample prep. In such platforms, AI-based data analytics optimize signal extraction, peak identification, and noise suppression in real-time, drastically improving throughput and decision accuracy [162]. Alves et al. further emphasize that microfluidic platforms designed for autonomous operation can incorporate feedback mechanisms to adjust flow rates and separation conditions based on toxin concentration [173]. The addition of fluorescent or electrochemical sensors (as shown by [169]) enables rapid screening of multiple toxin classes simultaneously, even in low-resource settings [169]. These integrations support the development of fully portable, battery-operated M-LC systems with detection limits in the picomolar-to-nanomolar range, minimal sample consumption (≤1 µL) [173], and throughput improvements of up to 10× compared to conventional LC systems, positioning M-LC as a cornerstone of smart, sustainable analytical chemistry [162].

Despite its advantages, M-LC faces challenges—particularly in handling complex sample matrices and maintaining sensitivity. Miniaturized systems, while efficient, can still suffer from issues such as matrix interferences and co-elution, similar to traditional LC [129].

Recent advancements have significantly enhanced the capability of M-LC in toxin analysis. Improvements in column technology, such as reduced particle sizes, have led to higher separation efficiency [172]. Simultaneously, developments in microchip and LOC platforms have enabled the miniaturization of entire analytical workflows, reducing sample volume and cost while increasing throughput [129].

3.1.2. Drug Residues

Drug residues, especially antibiotics in food and environmental matrices, pose significant risks to public health, food safety, and ecological balance [174]. M-LC has rapidly evolved into a leading technique for trace-level detection of such residues [175]. When coupled with MS, M-LC enables highly sensitive, accurate, and selective analysis, even distinguishing between structurally similar compounds such as isomers [91]. HRMS, in particular, can detect residues in the ppt range, ensuring regulatory compliance [23].

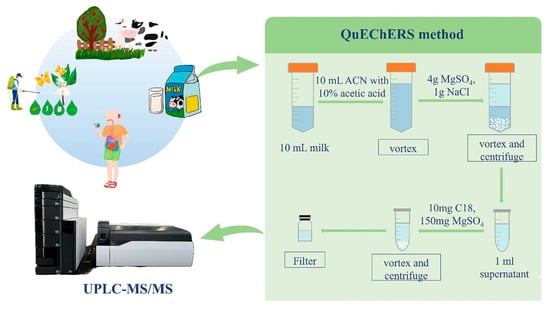

A notable study by Xueting et al. introduced a method for simultaneously quantifying 20 pesticide and veterinary drug residues in cow and buffalo milk (Figure 20) [174]. Using a modified QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged and Safe) extraction followed by UPLC-MS/MS, the method optimized sample treatment with 10% formic acid in acetonitrile, achieving efficient recovery. Calibration using matrix-matched curves demonstrated excellent linearity (R2 > 0.9990), and method validation showed recoveries of 73.1–111.6% with RSDs below 15%. Detection and quantification limits ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 μg/L and 2.0–5.0 μg/L, respectively, confirming the method’s sensitivity and precision.

Figure 20.

Workflow for detecting 20 pesticides and veterinary drugs via QuEChERS and LC-MS/MS. Milk samples (10 mL) of 10% formic acid in acetonitrile (ACN) were added to the sample in a 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube, vortexed for 2 min, and then supplemented with 4 g anhydrous magnesium sulfate and 1 g sodium chloride to prevent protein coagulation. The mixture was vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant (1 mL) was transferred to a 2 mL centrifuge tube containing 10 mg C18 and 150 mg anhydrous magnesium sulfate, vortexed for 1 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 1 min. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane and analyzed by UPLC-MS/MS [174]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [174]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Recent advancements in M-LC systems, particularly in sample preparation, solvent handling, and detector integration, have enabled practical improvements in the detection of veterinary drug residues in complex food matrices. For example, Zareasghari et al. demonstrated that coupling deep eutectic solvent-based pressurized liquid extraction with dispersive liquid microextraction (DLLME) significantly improved the recovery and sensitivity of organophosphorus pesticide residues in egg powder. The optimized method achieved LOD as low as 0.26 and 0.47 µg/kg with excellent repeatability (RSD < 8%) using only 10 mL of extraction solvent, a marked improvement over traditional LC workflows that typically consume higher solvent volumes and exhibit larger variation due to manual sample handling [176]. These results highlight how modern M-LC systems minimize sample and solvent consumption while maintaining high analytical performance, making them well-suited for rapid screening in food safety monitoring [177]. The enhanced pressure and flow control in miniaturized platforms also contribute to stable baselines and sharper peaks, facilitating trace detection even in complex biological matrices like egg powder, milk, or meat products [176].