Abstract

The transition to renewable energy technologies is one of the most important ways to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of affordable and clean energy (SDG7); industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG9); responsible production and consumption (SDG12); and climate action (SDG13). The widespread use of renewable energy technologies in developing countries will reduce dependence on imported fossil resources, increase industrial competitiveness, and support low-carbon development. Despite all their advantages, the integration of renewable energy technologies into industrial and domestic systems in developing countries remains slow due to a number of barriers. Financial constraints, technical and technological deficiencies, political restrictions and uncertainties, and organizational and managerial inadequacies are some of the barriers to the widespread adoption of renewable energy technologies. This study aims to identify, classify, and prioritize the barriers to the implementation of renewable energy technologies by applying multi-criteria decision-making methods in a fuzzy environment, with Türkiye considered as a case study. The relative importance of the barriers identified using the Single-Valued Spherical Fuzzy SWARA method was assessed, and their interconnections and significance were systematically demonstrated. The findings will contribute to the development of policy and management strategies aligned with global sustainability goals, thereby facilitating a more effective and equitable transition to clean and resilient energy systems.

1. Introduction

Energy is needed for all kinds of activities, both industrial and domestic, worldwide. Providing clean and affordable energy services to communities has become a top priority for policymakers, businesses, and governments [1,2]. The root cause of the climate crisis is fossil fuels used in energy production, industrial and domestic activities. Energy transformation is needed to reduce CO2, a major greenhouse gas released by fossil fuel use [3]. The average Earth’s surface temperature is between 1.34 °C and 1.41 °C warmer than it was in the late 1800 s, before the industrial revolution, and this temperature is increasing [3]. Research and a series of United Nations report suggest that limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 °C will help us avoid the worst climate impacts and maintain a liveable climate [3]. However, current policies and living standards could cause the average Earth’s surface temperature to rise by up to 3.1 °C by the end of the century [3]. To get the world to net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, nations need to take urgent action and develop comprehensive, long-term and integrated planning for a net zero emissions energy system [4].

The energy transition has become essential to combating climate change and achieving sustainable development goals. The foundation of the energy transition is the use of renewable energy sources in more sectors and activities [5,6]. Because traditional fossil fuels are limited and contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, this raises environmental and economic concerns. However renewable energy sources and technologies offer a sustainable, long-term solution for energy production [7,8]. At this point, energy transformation has become essential. However, while this transformation offers advantages, it will also present challenges. Adopting and implementing new technologies has always been considered a challenging process for businesses. The first and most critical goal, carbon emission reduction, requires structural changes in energy systems, and this multifaceted transformation process will present technical, economic, and social challenges [9,10]. Renewable energy technologies (RETs) aim to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the use of resources such as solar, wind, biomass, geothermal, hydro, and wave energy. The literature contains articles emphasizing the growing importance of these technologies in terms of technical maturity, cost competitiveness, and sustainability [11,12]. For developing countries, adapting to renewable energy technologies is not only a technical challenge but also a multidimensional decision-making problem that must be evaluated from economic, social and institutional perspectives [13]. Although there are many studies in the literature on the factors affecting the adoption of renewable energy technologies, research comparing the importance levels of these barriers systematically is quite limited. Existing studies often focus on one-dimensional analyses or remain specific to a particular technology type, making it difficult to provide a holistic understanding of the multifaceted barriers that hinder renewable energy integration, particularly in industrial sectors. Recent studies on renewable energy technologies have generally focused on renewable energy technology selection, performance evaluation, or policy debates, with little attention paid to the problems that may be encountered in practice. In many studies, MCDM methods are limited to ranking renewable energy alternatives or evaluating them in terms of sustainability, and do not systematically address the barriers in implementation. Furthermore, there are limited studies on identifying and evaluating them in developing countries like Türkiye. There is a lack of empirical studies that integrate technological, economic, theoretical, and regulatory barriers into a quantitative decision support system. Most existing studies rely on qualitative assessments or address barriers independently, which is limiting for practitioners and policymakers. To address these shortcomings, this study asks the question: “What are the most critical barriers to the implementation of renewable energy technologies in Türkiye, and how should these barriers be systematically prioritized in a fuzzy environment?” Accordingly, this study presents a fuzzy logic-based MCDM methodology incorporating expert opinions to evaluate and weight implementation barriers. This allows it to move beyond descriptive analysis and offer a structured, data-driven approach that supports strategic decision-making and policy formulation to accelerate the use of renewable energy in industrial sectors.

In this study, the Single-Valued Spherical Fuzzy SWARA (SVSFS) method was used to evaluate these barriers. The SVSFS method is an effective approach for managing the uncertainties inherent in evaluating the barriers that hinder the integration of renewable energy technologies. It simultaneously considers the degrees of membership, non-membership, and hesitation, thereby enabling a more comprehensive representation of uncertainty. In this respect, SVSFS allows uncertainty to be interpreted more clearly and realistically compared to intuitionistic and Pythagorean fuzzy approaches. The SWARA method, by structuring the weighting process through sequential pairwise evaluations among criteria, enables decision-makers to perform assessments more rapidly, effectively, and with greater consistency, particularly when dealing with a large number of criteria. The selected approach is required by the nature of the decision problem. The barriers addressed in the problem inherently involve high levels of uncertainty, subjective judgment, and hesitation. These barriers are often managed under conditions of partial acceptance and partial rejection, reflecting a state of indecision in the decision-making process. Classical fuzzy sets, as well as intuitionistic and Pythagorean fuzzy models, are unable to fully capture this complex network of uncertainty experienced by decision-makers. Spherical fuzzy sets, by simultaneously incorporating membership, non-membership, and hesitation degrees within a unified framework, provide a more comprehensive and flexible representation of uncertainty. This structure allows for a more accurate modeling of decision-makers’ hesitation and ambiguity, thereby reducing the distortion of subjective evaluations. Furthermore, the SWARA method enhances the reliability of the study by enabling the simultaneous comparison of multiple criteria in a structured and sequential manner, which helps reduce decision-makers’ uncertainty and cognitive burden when evaluating a large set of interrelated criteria.

The second section of the study will review the literature on renewable energy technologies. The third section will introduce the obstacles encountered in the implementation of renewable energy technologies and explain the MCDM method used. The fourth section of the study will discuss the results obtained from the application.

2. Literature Review

A search conducted on 22 October 2025, in the Web of Science database using the keyword “Renewable Energy Technology” revealed 469 publications between years 2016 and 2025. Approximately 56% of these publications were articles, 34% were proceedings papers, and 10% were book chapters. By adding the keyword “barriers” and “MCDM” to the same search, the number of journal articles decreased to 49.

Lu and his colleagues conducted a study to select the most suitable renewable energy technology to alleviate energy poverty in 2023. In their research, they used the best-worst method based on quality function deployment using interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy numbers. The six renewable energy technologies including solar energy, wind energy, biomass, and hydropower have been selected as alternatives, and the result shows that large-scale hydropower could be selected as the best alternative to obtain the goal [14].

A study was conducted to select the most sustainable renewable energy technology in Morocco for 2023. MCDM methods were used to evaluate existing renewable energy technologies in Morocco in terms of environmental, economic, technical, and social criteria. The cardinal method was used to determine the criteria weights, and the PROMETHEE (The Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment of Evaluations) method was used to rank the alternatives. The study determined that economic and environmental factors were the most important criteria, with photovoltaic solar (PVS) ranking first as the most sustainable technology [15]. Malaysia, a country characterized by excessive energy consumption, has implemented multiple policies to develop and expand renewable energy technologies. However, as of 2022, only 2% of the country’s energy supply will come from renewable energy sources. The study used the fuzzy MCDM method to evaluate renewable energy technologies across various dimensions, including technology, economy, society, and environment. Efficiency, payback period, employment generation, and CO2 emissions were identified as the most critical factors. The most sustainable and affordable renewable energy source was identified as solar power [16]. In Türkiye, studies and projects are underway to expand renewable energy technologies across all sectors. A study conducted by Akusta et al. [17] in 2025 aimed to identify and prioritize the obstacles to the development of renewable energy investments. The significance levels of thirty sub-obstacles, categorized under four main categories, were determined using the fuzzy AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) method. They concluded that political and regulatory barriers were the most significant, while lengthy procedures and legal processes were the most significant sub-barriers [17].

Numerous studies have been conducted on the economic and environmental importance of renewable energy technologies. These studies have specifically investigated the barriers to these technologies and developed measures to overcome them. A study conducted in Iran specifically investigated the barriers encountered in the implementation of wind and solar energy. The evaluation was conducted by considering the cause-and-effect relationships among existing barriers. Using fuzzy cognitive maps and slack-based data envelopment analysis, a prioritization was established to achieve the ideal situation more quickly. Finally, the impact of each improvement solution on system objectives was examined in terms of the cause-and-effect relationships among the barriers [18]. Similarly, the Libyan government has committed to reducing its carbon footprint. To this end, studies and research have been conducted to expand renewable energy sources, particularly solar, wind, and biomass, in the country. Ali and his colleagues also utilized MCDM methods to identify the best renewable energy sources. Comparing the results obtained from various MCDM methods, they concluded that the most suitable energy source was a combination of wind and solar energy. They also indicated that COPRAS (The COmplex PRoportional Assessment) or VIKOR (VIseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje) were the best methods for selection [19].

Furthermore, countries face challenges facing standards and regulations in the renewable energy sector. These challenges influence the investment decisions of renewable energy producers. Song et al. proposes a model to address the uncertainty in renewable energy investment decision-making under the new renewable portfolio standards (RPSs). The real options (ROs) method, which allows for the consideration of numerous influencing factors, was used. This method evaluated numerous factors, including tax incentives, market electricity prices, changes in investment costs, and pricing policies. The study provides clear recommendations for investors and recommends that the Chinese government take further action regarding the transition to low-carbon energy systems [20]. Other studies on renewable energy sources in the literature are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies in the literature.

The existing literature on renewable energy technologies widely uses MCDM methods to identify optimal technologies or detect barriers to their implementation. However, a more comprehensive review has revealed several structural limitations. Firstly, most technology selection studies generally assume ideal implementation conditions and evaluate renewable energy alternatives based on economic, environmental, technical, and social criteria. In contrast, studies attempting to identify barriers have focused on identifying and prioritizing technological, financial, and regulatory constraints. Secondly, although MCDM methods such as AHP, COPRAS, VIKOR, and PROMETHEE have been widely used, many studies have not conducted sensitivity analyses to compare the methods or show how the results might change under different scenarios. Finally, there are few empirical studies that simultaneously address the interactions of barriers encountered in the selection or implementation of renewable energy technologies, particularly in developing countries like Türkiye, within a unified analytical framework. From a contextual perspective, empirical evidence focusing particularly on developing countries, especially Türkiye, is insufficient despite the immense strategic importance of this transition for these countries. Existing studies have focused either on ranking renewable energy technologies or on qualitatively evaluating the obstacles. There has been a lack of systematic prioritization of the obstacles that may be encountered in the transition to renewable energy technologies through quantitative research based on expert opinions. This study proposes a comprehensive fuzzy-based MCDM framework that evaluates renewable energy technologies and their associated barriers together, thus providing more applicable information for policymakers and implementers.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, the barriers to renewable energy technologies and the Single-Valued SVSFS method used to determine the importance of these barriers will be introduced.

3.1. Barriers to Renewable Energy Technologies

The barrier framework adopted and addressed in this study is based on the renewable energy and sustainable supply chain literature, which generally considers and conceptualizes barriers to the implementation of renewable energy technology in a multidimensional way. Previous studies have consistently categorized barriers into technical, economic, financial, organizational, and social dimensions, providing a systematic framework for transitions to renewable energy technologies in industrial sectors. High initial investment costs and limited access to financing, which are among the economic and financial barriers, are commonly encountered as critical barriers. Technical and infrastructural barriers such as grid unreliability, inadequate technical infrastructure, and personnel shortages are highlighted as the main barriers encountered in the application of renewable energy technologies to industries. Furthermore, bureaucratic approval processes and weak internal implementation mechanisms in the organizations negatively impact the adoption of renewable energy technologies. In addition, challenges in implementing these technologies are experienced, particularly in developing countries, including dependence on imported technologies and limited local production capacity. This study synthesizes information obtained from expert assessments and extensive literature reviews to define a comprehensive barrier framework for the application of renewable energy technologies, based on existing established classifications. For this purpose, the barriers identified using previous studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Barriers to the integration of renewable energy technologies into industries.

While classifications in the literature are used to identify barriers in the implementation of renewable energy technologies, their importance is further amplified, particularly in developing economies like Türkiye, where industrial energy systems exhibit unique structural characteristics. Türkiye’s industrial sector has high energy intensity and is significantly dependent on imported fossil fuels. Therefore, the integration of renewable energy technologies becomes a strategic issue, not only from a sustainability perspective but also in terms of energy security and cost fluctuations. Furthermore, SMEs face economic and financial barriers due to exchange rate fluctuations, limited access to green finance, and restricted investment capacity. Technical and infrastructural barriers are further exacerbated by regional disparities in energy infrastructure, grid reliability, and legacy industries that rely on fossil fuels. In addition, frequent regulatory changes and complex permitting processes in Türkiye create uncertainty and difficulties for businesses due to institutional and political barriers. Furthermore, in competitive industrial markets, organizational and cultural barriers are also significant, as sustainability-focused decision-making processes take a backseat to short-term cost considerations. Therefore, although the barrier classification resembles the global classifications defined in the literature, the interaction, application, and relative importance of these barriers are context-dependent. This study explicitly applies the barrier framework to the Turkish industrial context by reflecting the identified barriers and local economic conditions, regulatory structures, and industrial practices.

The importance of renewable energy technologies in developing societies lies in their ability to address sustainable development goals. At the same time, they play a critically important role in ensuring the security of energy resources and managing adverse environmental conditions. However, it is also essential to address the potential challenges associated with implementing these technologies. Therefore, identifying, analyzing, and determining the significance of these challenges will enable developing societies to overcome difficulties encountered in the decision-making process. Moreover, it will ensure the effective management of technological investments. In this study, the challenges encountered in the selection of renewable energy technologies in Türkiye, classified as a developing country, are examined. For this evaluation, the SVSFS method was applied.

First, experts participating in the evaluation process were carefully selected, with preference given to individuals possessing substantial experience in knowledge management. A general overview of the experts is presented in Table 1.

Second, an extensive literature review was conducted to identify the criteria to be included in the study, taking into account the preliminary insights of the experts. In line with expert opinions, the criteria related to the barriers to the integration of renewable energy technologies into industries were determined from the existing literature.

Third, the SVSFS method was applied to distinct entities. Subsequently, the linguistic variables to be employed in the evaluations were defined.

Thereafter, the decision-makers assessed the criteria based on the established linguistic variables. During this phase, the experts utilized their knowledge and professional experience to evaluate the importance or impact of each criterion using linguistic terms. This approach facilitates a more standardized and comparable analysis of subjective judgments. The evaluations were then aggregated according to the weights assigned to each decision-maker, converted into a unified value, and normalized accordingly.

Following this, score function, comparative importance of score value (sj), comparative coefficient (kj), fuzzy weight (pj) and relative weights (wj) is calculated. Finally, to minimize subjectivity, a sensitivity analysis was performed to verify the robustness of the assigned weights and reduce potential biases. The overall structure of the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General structure of the study.

In Türkiye, accurately assessing these challenges when making technology investments will help establish a vision that enables sound future decisions and analyses in this field. The use of the SVSFS method aims to minimize uncertainties in evaluating these barriers. It also reflects the intuitive judgments of DMs throughout the evaluation process. The method considers both positive and negative degrees of uncertainty, ensuring a balanced and comprehensive assessment. Consequently, it identifies which barriers should be prioritized when making investment decisions. For this purpose, the opinions of five energy experts (DMs) were collected, and their evaluations are presented in Table 3. In the selection of decision-makers, subject-matter expertise and practical application experience were considered as the primary criteria. The selected decision-makers possess substantial industrial experience in the implementation and operation of renewable energy technologies. Their evaluations reflect diverse perspectives derived from different functional units, including maintenance, production, and research and development, thereby ensuring a multifaceted assessment of the problem.

Table 3.

DMs’ profile.

3.2. Spherical Fuzzy Set

Spherical Fuzzy Set Theory (SFS) was developed by Gündoğdu Kahraman [53] in 2019. SFS the spherical fuzzy set over the universe of discourse characterizes in Equation (1).

where : X → [0, 1], : X → [0, 1], : X → [0, 1] gives for each element , the respective degrees of belongingness, non-belongingness, and indeterminacy associated with in Equation (2).

Let denotes a spherical fuzzy (SF) number. The score value (Equation (3)) and accuracy function (Equation (4)) corresponding to are determined using the following expressions.

Single-valued Spherical Weighted Arithmetic Mean (SWAM) regarding w=

Single-valued Spherical Weighted Geometric (SWGM) regarding w=

3.3. Single-Valued Spherical Fuzzy SWARA

The SWARA method, developed by Zavadskas et al. [54] in 2010, is a technique used to determine the weights of criteria. It operates based on a ranking-oriented relative weighting approach. The procedural steps of the method are outlined below.

Phase 1. According to linguistic terms in Table 4, the criteria are assessed.

Table 4.

Linguistic Terms and Values [53].

Phase 2. The decision-makers (DMs) evaluate their significance using linguistic terms. The weights of the DMs are determined according to Equation (7), while their evaluations are aggregated based on Equation (5).

Phase 3. The Score Function is obtained using Equation (3).

Phase 4. The comparative importance of the score value () is computed.

Phase 5. It is followed by the determination of the comparative coefficient ().

Phase 6. The fuzzy weight () is then calculated.

Phase 7. the relative weights () are derived.

4. Results

Five DMs from an energy-sector firm located in Muğla were selected to participate in the study. Individuals with expertise in energy technologies were specifically chosen, and the interviews were conducted through face-to-face meetings. The study employed fuzzy linguistic terms, enabling a more realistic and nuanced assessment through linguistic evaluations. The primary objective of this research is to determine the weights of the barriers associated with energy technologies using the SVSFS approach, which represents one of the contemporary fuzzy-based methodologies

The linguistic terms of the DMs’ importance weights are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The linguistic terms of the DMs’ importance weights.

Subsequently, the linguistic evaluations of the DMs were presented in Table 6, based on the linguistic scale provided in Table 4.

Table 6.

The linguistic evaluations of the decision-makers.

The calculation of the criteria weights using Equations (3)–(11) is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Barriers’ weights.

The importance weights of the barriers to renewable energy technologies reveal which barriers most significantly hinder the widespread adoption of these technologies in Türkiye. Firstly, the high weight of political and legal barriers demonstrates that energy transition is not only a technical challenge but also a major governance issue. Weak energy policies, insufficient incentive mechanisms, and bureaucratic hurdles negatively affect private sector investment decisions. Secondly, the high significance of economic and financial barriers underscores the critical role of high initial costs and financing difficulties in renewable energy projects. Therefore, the lack of credit and investment incentives creates severe crises in technological development. Thirdly, technological and infrastructural barriers cause substantial challenges in integrating existing national energy infrastructures with renewable systems. Fourthly, institutional and managerial barriers reflect deficiencies in organizational vision and governance required to support energy transition. Finally, the notable weight of social and cultural barriers indicates that public awareness and social acceptance of renewable energy technologies remain relatively low compared to other categories.

In terms of sub-criteria, High Capital Costs (EFB-1) emerged as the most significant barrier. Particularly in the energy sector, the substantial investment required for technological infrastructure poses a major obstacle to large-scale initial investments. Limited Access to Financing (EFB-2) ranked as the second most critical barrier. Firms in developing countries tend to be less responsive and capable of allocating sufficient financial resources for energy-related investments. The third most important barrier identified was Incompatibility with Existing Systems (TIB-1), which highlights the necessity of redesigning existing infrastructures to accommodate renewable energy technologies. Fourthly, the criterion of Unreliable Power Grids (TIB-2) was also found to be highly influential, as power interruptions reveal the inadequacies of energy distribution infrastructures. Finally, Weak Policy Frameworks (IPB-1) reflect the insufficiency of renewable energy policies in developing countries, underscoring the need for stronger institutional and regulatory mechanisms to support energy transition.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted based on the opinions of the experts. In addition to the weights provided in Case 1, four additional cases were evaluated. The scenarios are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

The scenarios for DMs.

The results were analyzed in terms of ranking consistency using the Spearman correlation coefficient (Table 9).

Table 9.

Ranking for Cases.

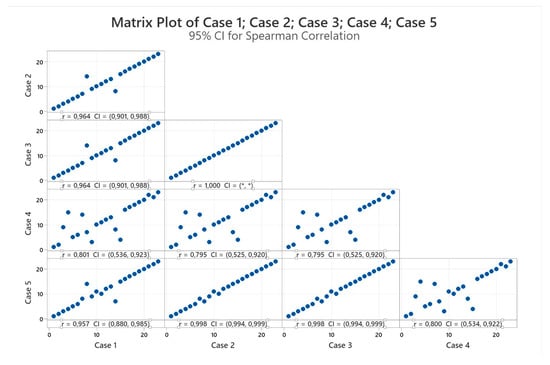

Spearman Correlation evaluation in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spearman Correlation Evaluations for Cases(These dots represent the relation between two different variables. “*” means confidence interval. If standard deviation equals to zero, confidence interval becomes “*”).

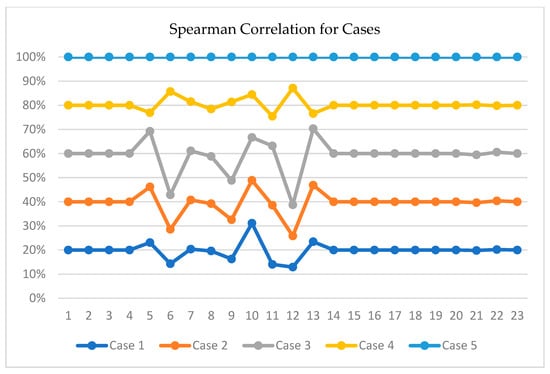

Spearman Correlation Evaluations in Cases for Sensitivity in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Spearman Correlation Evaluations in Cases for Sensitivity.

Upon examination, it was observed that the results were closely aligned across all cases. The weights of the criteria for the five cases are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

The weights of the criteria for the five cases.

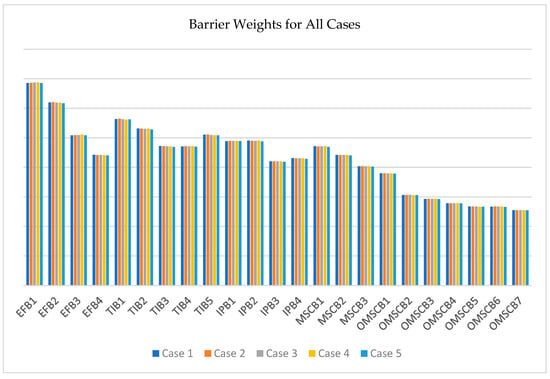

The weights of the criteria for the five cases are presented in Figure 4. As observed, the variations in the results remain very limited even across different scenarios.

Figure 4.

Barrier Weights for All Cases.

The findings indicate that the most critical barriers to renewable energy technologies in Türkiye are predominantly technical in nature, highlighting the central role of technological and infrastructural constraints in hindering energy transition. Economic and Financial Barriers follow closely, underscoring the importance of investment-related challenges. The relatively high importance of Political and Institutional Barriers (IPB) further demonstrates that renewable energy deployment requires strong governance structures, stable regulatory frameworks, and effective policy support mechanisms. Although Market and Supply Chain Barriers (MSCBs) and Organizational, Managerial, Social, and Cultural Barriers (OMSCBs) exhibit comparatively lower weights, their significance should not be underestimated. Factors such as social acceptance, institutional capacity, and managerial structures remain critical enablers of sustainable energy development, indicating that renewable energy barriers must be addressed within a multidimensional and systemic framework.

At the sub-criteria level, High Capital Costs (EFB1) and Limited Access to Financing (EFB2) emerge as the primary bottlenecks, clearly revealing that financial constraints constitute the dominant impediments to renewable energy investments. Moreover, Incompatibility with Existing Systems (TIB1) and Unreliable Power Grids (TIB2) indicate a lack of flexibility and readiness in current energy infrastructures, which significantly limits effective integration of renewable technologies. In addition, Weak Policy Frameworks (IPB1) emphasize the complementary yet indispensable role of governance and institutional arrangements in supporting technological and financial efforts. Overall, these findings confirm that overcoming renewable energy barriers requires coordinated interventions across technical, financial, institutional, and socio-organizational dimensions. The results indicate that there is no observable or significant variation across the five different cases.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the challenges encountered in renewable energy technologies were examined. For this purpose, the SVSFS method was applied based on the opinions of five experts working in a renewable energy firm located in Muğla. As a result of the application, the barriers were evaluated under five main categories and twenty-three subcategories.

The fact that technical and infrastructural barriers have the highest weight indicates that the integration of renewable energy technologies is constrained by the insufficient transformation capacity of the existing energy infrastructure. In particular, incompatibility with existing systems (TIB-1) and unreliable power grids (TIB-2) reveal that the problem extends beyond design deficiencies and is fundamentally related to the overall system architecture. Rather than continuing with fossil fuel-centric system designs, a comprehensive infrastructure-based systemic transformation is required. In this context, smart grids, energy storage systems, and flexible grid architectures should be developed in an integrated manner. Incentives for modular and scalable infrastructure investments should be effectively utilized where available. Moreover, the mandatory implementation of technical standards focusing not only on generation capacity but also on system compatibility would significantly mitigate integration-related challenges.

Economic and financial barriers were identified as the second most significant category. High capital costs (EFB-1) and limited access to financing (EFB-2) emerged as the most critical sub-criteria within this group, directly highlighting the issue of financial sustainability. These findings emphasize the need for effective management of incentive mechanisms and the adoption of measures aimed at reducing energy costs to enhance the financial feasibility of renewable energy investments.

Organizational, managerial, social, and cultural barriers primarily challenge prevailing institutional mindsets. In particular, lack of awareness (OMSCB-1), short-term planning horizons (OMSCB-2), and resistance to change (OMSCB-3) significantly constrain the effectiveness of technical and financial solutions. Therefore, renewable energy investments should be approached not merely as cost-driven initiatives but as strategic tools for enhancing corporate competitiveness and strengthening risk management capabilities.

Within the category of institutional and policy barriers, weak policy frameworks (IPB-1) and regulatory uncertainty (IPB-2) are perceived as major deficiencies in terms of long-term predictability and stability. These results underline the necessity of developing participatory policy-making mechanisms and establishing long-term, clearly defined roadmaps to support renewable energy integration.

Market and supply chain barriers were found to be relatively less influential compared to other categories. Nevertheless, limited local manufacturing capacity (MSCB-1) and volatile supply chains (MSCB-3) increase technological dependency. Accordingly, strengthening research and development activities and the renewable energy supply ecosystem, alongside adopting multi-sourcing strategies to enhance supply chain resilience, is essential.

From a theoretical perspective, these results indicate that the renewable energy transition presents not only a technical but also a multidisciplinary structure. These main dimensions support the “systemic transformation” approach. In this context, the theoretical contribution of the study highlights the need to develop more holistic models to explain the adoption of energy technologies in developing countries. From a practical standpoint, identifying the priority barriers enables strategic prioritization for national policymakers and industrial firms, thereby facilitating effective technology transfer. In terms of social implications, the findings emphasize that the transition should foster not only economic but also cultural transformations.

The main limitation of this research arises from the temporal and geographical constraints faced during the data collection process aimed at identifying the barriers and evaluating their relative significance. Furthermore, limiting the dataset exclusively to the thermal energy sector in Türkiye represents another constraint. In the context of the integration challenges of renewable energy technologies in Türkiye, the experience and sector-specific expertise of the selected decision-makers have strengthened the reliability of the collected data and the robustness of the decision-support structure. Nevertheless, future studies may broaden the scope of the analysis by incorporating experts from different regions and stakeholder groups (such as public institutions, policymakers, and suppliers). The inability to generalize the findings to broader populations, various countries, or other industrial domains also restricts the study’s applicability. Future investigations could overcome this issue by identifying industry-specific barriers across different sectors. Additionally, alternative fuzzy set approaches could be employed to address the problem, and the findings could be compared using diverse weighting techniques based on identical or distinct fuzzy frameworks. Methods such as Hesitant, Picture, Pythagorean, Neutrosophic, and Fermatean can be applied in future research. Moreover, the integrated application of SVSFS with methods such as Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) or Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCMs) may enable a more in-depth analysis of the interactions among the identified barriers. At the same time, the weights of the barriers identified in this study were calculated in accordance with the current technological level, policy framework, and industrial development specific to Türkiye. Over time, particularly with the impact of technological advancements, future studies may address different conditions by integrating the SVSFS method with alternative approaches and by considering additional or evolving barrier categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and E.Ç.B.; methodology, H.T. and E.Ç.B.; formal analysis, H.T. and E.Ç.B.; data curation, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T. and E.Ç.B.; writing—review and editing, H.T.; visualization, H.T. and E.Ç.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hakan Turan was employed by the company OPEX Academy. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SFS | Spherical Fuzzy Sets |

| SVSFS | Single-Valued Spherical Fuzzy SWARA |

References

- Akpahou, R.; Mensah, L.D.; Quansah, D.A.; Kemausuor, F. Long-term energy demand modeling and optimal evaluation of solutions to renewable energy deployment barriers in Benin: A LEAP-MCDM approach. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1888–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/18041SDG7_Policy_Brief.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Worku, A.K.; Worku Ayele, D.; Deepak, D.B.; Gebreyohannes, A.Y.; Agegnehu, S.D.; Kolhe, M.L. Recent advances and challenges of hydrogen production technologies via renewable energy sources. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2300273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshtinia, M.A.; Yaghobian, S.N.; Fathi, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Foroughi, B. Overcoming barriers to renewable energy adoption: A decision-making framework for strategy evaluation and implementation prioritization. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 18, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi-Cerdá, I.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; García-Melón, M.; D’Este, P.; Poveda-Bautista, R. Drivers and barriers to the adoption of decentralized renewable energy technologies: A multi-criteria decision analysis. Energy 2024, 305, 132264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Minx, J.C.; Toth, F.L.; Abdel-Aziz, A.; Meza, M.J.F.; Hubacek, K.; Jonckheere, I.G.C.; Kim, Y.-G.; Nemet, G.F.; Pachauri, S.; et al. Emissions trends and drivers. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_Chapter02.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Tseng, M.-L.; Ardaniah, V.; Sujanto, R.Y.; Fujii, M.; Lim, M.K. Multicriteria assessment of renewable energy sources under uncertainty: Barriers to adoption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 171, 120937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Dessi, F.; Bonaiuto, M. A meta-analysis on the drivers and barriers to the social acceptance of renewable and sustainable energy technologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 114, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, K.; Lőrincz, M.J.; Alaei, M.H.; Lautert, R.R.; Siano, P.; Kia, M.; Görel, G. Review of transmission planning and scaling of renewable energy in energy communities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 222, 115928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Capacity Highlights. Abu Dhabi. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2025/Mar/IRENA_DAT_RE_Capacity_Highlights_2025.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Wheatley, M.C. Advancements in renewable energy technologies: A decade in review. Premier J. Sci. 2024, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Oyewo, A.S.; Lopez, G.; Kaypnazarov, K.; Breyer, C. Technologies, trends, and trajectories across 100% renewable energy system analyses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.F.; Zhou, J.Z.; Ren, J.Z. Alleviating energy poverty through renewable energy technology: An investigation using a Best-Worst method-based Quality Function Deployment approach with interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy numbers. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 8358799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouraizim, M.; Makan, A.; El Ouarghi, H. A CAR-PROMETHEE-based multi-criteria decision-making framework for sustainability assessment of renewable energy technologies in Morocco. Oper. Manag. Res 2023, 16, 1343–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y. Selection of renewable energy development path for sustainable development using a fuzzy MCDM based on cumulative prospect theory: The case of Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akusta, E.; Ari, A.; Cergibozan, R. Barriers to renewable energy investments in Turkiye: A fuzzy AHP approach. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.J.; Yousefi, S.; Hayati, J. Root barriers management in development of renewable energy resources in Iran: An interpretative structural modeling approach. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Musbah, H.N.; Aly, H.H.; Little, T. Hybrid renewable energy resources selection based on multi criteria decision methods for optimal performance. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 26773–26784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Han, J.J.; Li, Q.C.; Li, S.Y.; Li, J.J.; Xu, S.Z. Research on investment decision-making of renewable power producers under the new renewable portfolio standards. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 518, 145867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Sanagustin-Fons, V.; Fierro, J.A.M. Social perception of renewable energies: Barriers and opportunities for an inclusive energy transition. Energy Policy 2026, 208, 114899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlborg, H.; Hammar, L. Drivers and barriers to rural electrification in Tanzania and Mozambique e Grid-extension, off-grid, and renewable energy technologies. Renew. Energy 2014, 61, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhirasasna, N.; Becken, S.; Sahin, O. A systems approach to examining the drivers and barriers of renewable energy technology adoption in the hotel sector in Queensland, Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Curtis, J.; Clancy, M. Modelling barriers to low-carbon technologies in energy system analysis: The example of renewable heat in Ireland. Appl. Energy 2023, 330, 120314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, D.; Wenqi, J.; Sameeroddin, M. Prioritization of ecopreneurship barriers overcoming renewable energy technologies promotion: A comparative analysis of novel spherical fuzzy and Pythagorean fuzzy AHP approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Pathak, S.; Sharma, V.; Chougule, S.S.; Goel, V. Prioritization of barriers to the development of renewable energy technologies in India using integrated Modified Delphi and AHP method. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat, R.; Erdiwansyah, E.; Ghazali, M.F.; Rosdi, S.M.; Syafrizal; Bahagia. Strategic framework for overcoming barriers in renewable energy transition: A multi-dimensional review. Next Energy 2025, 9, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magableh, G.M.; Mistarihi, M.Z.; Daki, S.A. Innovative hybrid fuzzy MCDM techniques for adopting the appropriate renewable energy strategy. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 21, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Imani, M.A. Overcoming implementation barriers to renewable energy in developing nations: A case study of Iran using MCDM techniques and monte carlo simulation. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, W.O.; Ofosu, E.A.; Ampimah, B.C. Decision optimization techniques for evaluating renewable energy resources for power generation in Ghana: MCDM approach. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 13505–13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, M.; Mukul, E.; Konyalıoğlu, A.K. A hesitant fuzzy approach to renewable energy technology selection aligned with sustainable development goals in Turkey. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 48, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, D.; Wenqi, J.; Tanveer, A.; Sharaf, I.M. Identifying and prioritizing obstructions and strategies towards wind energy using an integrated MCDM approach. Energy 2025, 323, 135848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Li, Y.; Neo, P.L.; Wang, Z.; Xia, C. Subjective-objective median-based importance technique (SOMIT) to aid multi-criteria renewable energy evaluation. Appl. Energy 2025, 402, 126872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Maleki, A.; Ahmadi, M.H.; Kiani, A.H. Comparative evaluation of renewable energy investments: A multi-criteria decision-making approach. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 28, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Imani, M.A.; Imani, M.S. Comprehensive strategic assessment of Iran’s renewable energy potentials through a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making approach. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 123896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Kumar, S. Sustainable renewable energy source selection with novel fuzzy entropy based extended TOPSIS method. Frankl. Open 2025, 13, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadli, O.E.; Hmamed, H.; Lagriou, A. Multi-objective optimization and improved decision-making in renewable energy investments for enhancing wind turbine selection: Framework and a case study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 326, 119464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, K.; Worrell, E.; Eichhammer, W. Energy efficiency and demand response—Two sides of the same coin? Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.R.; Shrimali, G. Role of policy in the development of business models for battery storage deployment: The California case study. Electr. J. 2021, 34, 107024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraimov, N.; Assylbayev, A.; Niiazalieva, K. Investments in renewable energy: Opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises through alternative financial instruments. Econ. Dev. 2025, 24, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, Y.A.; Longsheng, C.; Shah, S.A.A. Assessing and overcoming the renewable energy barriers for sustainable development in Pakistan: An integrated AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 173, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, I.; Anagnostopoulou, E. Identifying barriers in the diffusion of renewable energy sources. Energy Policy 2015, 80, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.F.; Kharb, R.K.; Luthra, S.; Shimmi, S.L.; Chatterji, S. Analysis of barriers to implement solar power installations in India using interpretive structural modeling technique. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, S.A.; Fini, M.V.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H.; Nazififard, M. Barrier analysis of solar PV energy development in the context of Iran using fuzzy AHP TOPSIS method. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegels, A. Renewable energy in South Africa: Potentials, barriers and options for support. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4945–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.A.; Solangi, Y.A.; Ikram, M. Analysis of barriers to the adoption of cleaner energy technologies in Pakistan using modified Delphi and fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.A.; Ahiabor, F.S.; Abalo, E.M. Analysing the barriers to renewable energy adoption in Ghana using Delphi and a fuzzy synthetic evaluation approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmeang, R.; Mazancová, J.; Roubík, H. Technological, economic, social and environmental barriers to adoption of small-scale biogas plants: Case of Indonesia. Energies 2022, 15, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. A review of the deployment programs, impact, and barriers of renewable energy policies in Korea. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Yao, S.; Rong, D.; Skare, M.; Streimikis, J. Renewable energy barriers and coping strategies: Evidence from the Baltic states. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Navarro, T.; Ribó-Pérez, D. Assessing the obstacles to the participation of renewable energy sources in the electricity market of Colombia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, K.; Green, D.; O’Faircheallaigh, C. Large-scale renewable energy developments on the Indigenous Estate: How can participation benefit Australia’s First Nations peoples? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 123, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogdu, F.K.; Kahraman, C. A Spherical fuzzy sets and spherical fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 36, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersuliene, V.; Turskis, Z. Integrated fuzzy multiple criteria decision making model for architect selection. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2011, 17, 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.