Abstract

Panettones enriched with Sambucus peruviana (elderberry) flour at concentrations of 4, 6, 8, and 10% were developed to study their physicochemical, bioactive, and sensory properties. Results showed that the incorporation of S. peruviana significantly increased fiber content, reaching 4.74% in the EP10 formulation, compared to 3.53% in the control (TP0). Total phenolic content also increased, reaching 6.7 mg GAE/g in EP10 versus 4.0 mg GAE/g in TP0. Regarding antioxidant capacity, DPPH antioxidant activity was the highest in EP10 (0.9 mg TE/g), while TP0 presented only 0.2 mg TE/g. In terms of physical properties, the color of the panettone progressively darkened with S. peruviana incorporation, with a decrease in lightness (L*) from 56.79 in TP0 to 39.54 in EP10. For texture, hardness increased significantly from 20.23 N in TP0 to 77.15 N in EP10, suggesting greater crumb compactness. In the sensory evaluation, formulations EP4 and EP6 showed higher acceptance in attributes such as color and aroma, while higher concentrations (EP8 and EP10) exhibited a slight decrease in acceptance due to increased hardness and a slightly bitter taste. These results demonstrate the potential of S. peruviana flour as a functional ingredient for enriching bakery products, enhancing their nutritional and antioxidant profiles without excessively compromising sensory characteristics.

1. Introduction

In recent years, interest in functional foods has grown considerably due to their ability to improve human health and contribute to agro-industrial sustainability [1,2]. These foods not only provide essential nutrients but also promote innovation and the development of new food matrices that incorporate bioactive compounds [3,4,5]. In this context, baking has become a dynamic sector, where innovation through the incorporation of functional ingredients—such as fiber, antioxidants, and alternative flours—is key to adapting to consumer demand, which is increasingly health-conscious [6,7]. Given its widespread acceptance, panettone represents an excellent platform for innovations aimed at optimizing its nutritional profile without compromising its sensory characteristics. To turn these products into functional foods, recent research has added bioactive compounds to baked goods, such as hibiscus flour [8] or grape by-products [5].

Among the plant sources that contain high levels of bioactive compounds, the fruits of the genus Sambucus have attracted special attention. The European species Sambucus nigra L. is valued for its high content of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and anthocyanins, as well as for its applications as a natural colorant and functional ingredient in various food matrices [9,10]. However, the Andean subspecies Sambucus peruviana has been less researched in the food sector, despite having a similar profile of phenolic compounds and great antioxidant potential [11]. The limited scientific information available on S. peruviana highlights the importance of conducting research aimed at enhancing its value in agro-industrial terms and incorporating it into functional products.

In the present study, panettone was enriched with an ingredient of high functional potential, S. peruviana (common name elderberry), which is rich in anthocyanins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids [12,13]. S. peruviana, exhibiting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [14,15], is considered an alternative for increasing the nutritional value of bakery products [16].

The incorporation of S. peruviana into panettone production presents a significant challenge, as the physicochemical interactions between its bioactive compounds and the flour, sugar, and fat matrices of the panettone alter the sensory properties of the final product [17,18]. However, a prolonged fermentation process and proper control of baking conditions can enhance the bioavailability of functional compounds [19]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the physicochemical and textural properties, bioactive potential, and sensory acceptance of panettone enriched with S. peruviana flour, as well as to assess its overall consumer acceptance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of S. peruviana

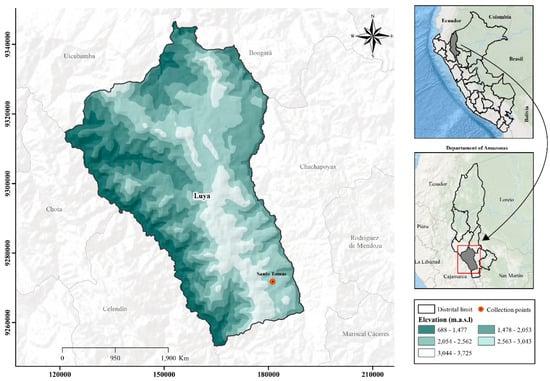

The fruits of S. peruviana were harvested at physiological maturity in March 2024, during the final harvest season, in the annex of Santo Tomas, province of Luya, Amazonas, Peru; located at coordinates 6°34′46.41″ S, 77°54′17.96″ W, at an altitude of 2525 m.a.s.l (Figure 1). After harvesting, the fruits were placed in polyethylene bags and stored in a cooler at 8 °C for transport to the Engineering Laboratory at the Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza National University of Amazonas. In the engineering laboratory, the S. peruviana fruits underwent an initial wash with running water. The disinfection process was carried out by immersing the fruit in distilled water containing a 0.4% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, prepared from commercial bleach (4% chlorine). Subsequently, they were rinsed with distilled water to remove any residual chlorine [20].

Figure 1.

Collection site of S. peruviana in the Amazonas region, Peru.

All the ingredients for making panettone were purchased in stores in the city of Chachapoyas, Amazonas, Peru.

2.2. Preparation of S. peruviana Flour

The fruits of S. peruviana were placed on stainless-steel trays and subjected to dehydration in a convection dryer (CE130,Gunt Hamburg, Hanskampring, Germany) with a constant airflow. The fruits were dehydrated at 45 °C for 8 h until reaching a relative moisture content of 10%. The dried material was ground using a high-speed blade mill and sieved through a 150 µm mesh to ensure a uniform particle size. Finally, the S. peruviana flour was packed in low-density polyethylene bags, vacuum-sealed, and stored at controlled room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) in darkness until further characterization [21,22].

2.3. Formulation of the Panettone

A traditional panettone (TP0) was prepared according to Table 1; four additional formulations were produced by adding S. peruviana flour in proportions of 4, 6, 8, and 10% w/w without replacing the base ingredients, which were named experimental panettones EP4, EP6, EP8, and EP10, respectively. The proportions reported in previous studies were taken as a reference for the development of this experiment [23].

Table 1.

Formulation and processing stages of traditional and experimental panettones with S. peruviana flour.

The process consisted of two stages. In the first stage, known as the “sponge,” the base premix, water, and instant dry yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) were combined in a laboratory mixer, and the resulting dough was fermented in a fermentation chamber (Max 1000-1, Nova, Lima, Peru) at 35 °C for 90 min. In the second stage, the fermented dough was returned to the mixer (AC-50, Intec Industries S.R.L., Lima, Peru) together with egg yolks, sugar, water, S. peruviana flour according to each treatment, and additional premix, and kneaded until an elastic dough was obtained. Subsequently, vegetable shortening, margarine, raisins, and candied fruits were added.

The dough was divided into 50 g portions, corresponding to a mini-panettone format designed to ensure experimental scalability and reproducibility of the process under laboratory conditions. The portions were placed in paper molds and fermented again at 35 °C for 35 min. Baking was performed in an oven (C-1400, Intec, Peru) in three consecutive stages: preheating (5 min at 160 °C), internal baking (45 min at 160 °C), and external baking (25 min at 185 °C). Upon completion of the baking process, a panettone was obtained, which was packaged in polypropylene bags with low gas and moisture permeability (thickness: 35 μm; moisture permeability: 7–20 g m−2 day−1; oxygen permeability: 50,000–100,000 cm3 m−2 day−1) [24] and stored at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 15 days to simulate shelf-life conditions before physicochemical and sensory analyses [25].

2.4. Proximate Analysis of Panettones

The proximate analysis of the panettone the determination of moisture, lipids, proteins, ash, total dietary fiber, pH, and titratable acidity, following to the methodologies established by the AOAC [5,25].

2.4.1. Moisture

Moisture content was determined using a moisture analyzer (KERN DAB 100-3, Balingen, Germany). One gram of panettone sample was placed on the analyzer plate and heated at 120 °C. The moisture content was recorded once a constant weight was reached or when the weight variation was below 20% [26].

2.4.2. Ash

Ash content was determined by incineration of 3 g of sample placed in previously tarred porcelain crucibles, following the AOAC Official Method 923.03. The samples were ashed in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 3 h until a constant light gray residue was obtained. The crucibles were then cooled in a desiccator and weighed. Ash content was expressed as a percentage of the dry weight of the sample.

2.4.3. Lipid

Lipid content was quantified using the Soxhlet extraction method (AOAC 920.39). Approximately 3 g of sample were subjected to continuous extraction using petroleum ether as solvent. After extraction, the solvent was evaporated, and the remaining lipid residue was dried and weighed. Lipid content was expressed as a percentage of the dry weight of the sample.

2.4.4. Protein

Protein content was determined using the Dumas combustion method with a Carbon–Nitrogen Elemental Analyzer (CN 928, LECO Corp., St Joseph, MI, USA). This method is based on the complete combustion of the sample at high temperatures, which releases the total nitrogen present in the sample as nitrogen gas (N2). The released gas is measured by a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) detector, allowing quantification of the total nitrogen content. The protein content was then calculated using a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25 [27,28].

2.4.5. Total Dietary Fiber

The total dietary fiber content was evaluated using the enzymatic–gravimetric method AOAC 991.43. Approximately 1 g of sample was subjected to successive enzymatic treatments with α-amylase, protease, and amyloglucosidase to hydrolyze digestible starch and protein components. The indigestible residue obtained was filtered, washed with ethanol and acetone, and dried to constant weight. The total dietary fiber was determined based on the indigestible residue, corrected for protein and ash content [29,30].

2.5. Physical Properties

2.5.1. Color

The color characteristics of panettone were analyzed in the CIE Lab system using a Konica Minolta digital colorimeter (CR-400, Osaka, Japan). The measurements were taken according to the methodology of Abdollahi Moghaddam et al. [31] with some modifications: the CIE Lab* scale, where L* represents lightness (0 = black and 100 = white), a* the range of the red color to green (+60 = red and −60 = green) and b* the range of yellow-blue (+60 = yellow and −60 = blue). The colorimeter was calibrated with a white standard, and initially applied to a standard white surface (L*, a*, b*). The total color difference (ΔE∗) (Equation (1)) and the whiteness index (W1) (Equation (2)) were obtained. The measurements were taken in triplicate on the panettone, with a randomly chosen center point; then a cross-section was made to take color measurements in the core of the panettone [32,33,34].

where L*, a*, and b* represent the differences between the color parameters of the samples and those of a standard white reference used as the measurement background.

2.5.2. Texture

The texture profile of the panettone samples was evaluated using a texture analyzer (CT3 Texture Analyzer, AMTEK Brookfield, Middleborough, MA, USA) equipped with a 25 kg load cell and a 25 mm-diameter cylindrical acrylic probe (TA25/100). Panettone samples measuring 50 mm × 70 mm in thickness were placed horizontally on the texture analyzer platform. The samples were kept at room temperature (25 °C) prior to texture measurements. The test parameters were set as follows: pre-test speed 2.0 mm/s; test speed 0.5 mm/s; post-test speed 0.5 mm/s; compression distance 6.0 mm; trigger force 0.10 N; and data acquisition frequency 20 points/s. The parameters of hardness (N), deformation (mm), and elasticity (mm) were recorded [35,36].

2.6. Bioactive Properties

2.6.1. Preparation of the Methanolic Extract

A methanolic solution was prepared as described by Jonfia-Essien et al. [37] with some modifications. To extract the bioactive compounds of the panettones, 1 g of sample was diluted in 80 mL of methanol–water solution (80:20 v/v). Subsequently, it was homogenized for 5 min in a Vortex Mixer (Mixer S0200, Labnet International, Edison, NJ, USA). Then, the mixture was centrifuged for 30 min at 3000 rpm in a centrifuge (MPW-251, MPW-Med. Instruments, Warsaw, Poland). The supernatant was collected using a sterile syringe and filtered through nylon membranes (0.45 μm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, it was stored at −15 °C in the absence of light until further analysis. This procedure was performed in triplicate for each treatment [38].

2.6.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The total phenolic content (TPC) of the panettone was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method according to the procedure described by Singleton et al. [39] with some modifications. A 20 μL aliquot of the sample was mixed with 40 μL of 10% Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (5 min) and 160 μL of 7.5% (w/v) Na2CO3 solution. The mixture was kept in the dark for 60 min at room temperature (18 ± 2.25 °C), after which the absorbance was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (GENESYS 180, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 765 nm. The calibration curve was constructed using gallic acid equivalent (GAE) dilutions (0–200 mg L−1), resulting in the equation: y = 0.005x + 0.0707 (R2 = 0.99). TPC was expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent per L of sample (mg GAE/L) [40].

2.6.3. Antioxidant Capacity by DPPH

The antioxidant activity was determined using a spectrophotometric assay, which measures the radical scavenging capacity of DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl). To evaluate the radical scavenging activity, 20 μL of panettone extract was mixed with 125 μL of DPPH solution. The reaction mixture was agitated and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 517 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The antioxidant activity was quantified using the Trolox standard curve: y = 0.6719x + 44.181 (R2 = 0.99). The antioxidant activity was calculated according to Equation (3), and the results were expressed as μmol Trolox equivalents (TEs) per gram of sample [41].

where A0 represents the absorbance of the DPPH solution, and A1 is the absorbance of the sample.

2.7. FT-IR Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed in the infrared region, acquiring data in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. A Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used, and spectral acquisition was carried out using 32 scans with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, following the procedures described by Warren et al. [42], and Kim et al. [43]. The obtained spectra were processed using OMNIC™ software (version 8.2). Absorbance plots were generated using RStudio software (version 4.3.3) [41].

2.8. Sensory Analysis

Sensory evaluation was carried out using a structured 5-point Likert-type hedonic test, chosen because it is appropriate for untrained panelists, as it helps them understand the attributes evaluated and reduces the variability associated with longer scales [44]. In accordance with international guidelines, informed consent was obtained prior to the sensory evaluation from semi-trained panelists randomly selected (100 participants). Sensory analysis was performed in the laboratory at the Toribio Rodriguez National University of Mendoza in Amazonas (UNTRM). Panelists were presented with a slice of panettone, coded with a random three-digit number [45]. To evaluate the sensory attributes of color, smell, taste, texture, and appearance, the methodology described by Lawless et al. [46] was followed. Panelists were selected from university students over the age of 18 who are frequent consumers of bakery products and had no allergies to the ingredients used in this research. Those who did not meet these criteria were excluded. Each panelist recorded their perception on a sensory evaluation form and was instructed to drink water between samples to avoid sensory interference. Color was evaluated visually under neutral light; smell was evaluated by direct aroma perception; taste was evaluated through consumption; and texture was evaluated both orally and through tactile perception during con-sumption.

2.9. Data Analysis

The results were subjected to an analysis of variance to determine statistical dif-ferences among treatments. ANOVA and Tukey’s test were applied at a significance level of p < 0.05 to identify significant variations between treatments. Data were pro-cessed using the Agricolae package [47] in the R programming language (RStudio, Version 4.3.3, Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition

The incorporation of S. peruviana flour produced significant differences (p < 0.05) in the proximate composition and physicochemical parameters of the panettones (Table 2). The moisture content increased from 14.24 ± 0.05% to 16.39 ± 0.03%, showing an upward trend as the proportion of S. peruviana flour increased, with the EP8 formulation exhibiting the highest value. This effect may be explained to the ability S. peruviana flour to promote the formation of a more stable gluten network, thereby enhancing water retention within the dough [48]. Additionally, this network improves the distribution of volatile compounds and the diffusion of carbon dioxide (CO2) during fermentation and baking [49,50]. Similar behavior was reported by Rodiguez et al. [51] in panettones enriched with okara flour, were moisture content increased from ~17% to 33%.

Table 2.

Proximate Composition and Physicochemical Parameters of Panettones Enriched with S. peruviana Flour.

From a technological standpoint, a product with higher ash content is considered undesirable and of lower quality, as they tend to exhibit darker coloration and in-creased proteolytic and amylolytic enzyme activity [52,53]. In this study, ash content showed a slight decrease from 1.87 ± 0.03% in TP0 to 1.55 ± 0.09% in EP10. This reduction may be attributed to mineral dilution relative to the base premix and to the lower inorganic content of S. peruviana flour [54].

The fat content was the highest in the TP (12.30 ± 0.06%). This pattern is attributed to the use of key ingredients in the formulation, such as butter and vegetable fat, which increase the lipid content of the final product [55]. On the other hand, previous studies have reported that the incorporation of alternative flours, such as cocoa flour or sinami by-products, can reduce the fat content in baked products [56]. Accordingly, it may be inferred that the inclusion of S. peruviana flour contributed to the reduction in the panettone’s fat content.

Protein values ranged from 12.17 ± 0.23% to 11.37 ± 0.12%, comparable to those reported by Jamanca-Gonzales et al. [25] in traditional panettones (8.40 to 10.40%), and by Bigne et al. [57] for panettone-type bread enriched with mesquite (9.3 to 9.9%).

Regarding fiber content, a moderate increase was observed, from 3.53 ± 1.50% to 4.74 ± 0.01%—as the proportion S. peruviana flour increased, confirming its functional contribution to the formulation. Previous studies evaluating the fruits and flowers of S. peruviana have similar reported enhancements in fiber content in bakery products [58,59].

Finally, the pH decreased from 5.27 ± 0.16% to 4.30 ± 0.23%, while the titratable acidity increased from 0.25 ± 0.01% to 0.30 ± 0.01%, indicating an acidification trend as the proportion of S. peruviana flour increased. This effect is attributed to the contribution of organic acids (citric, malic, and tartaric) and the release of phenolic compounds during mixing and fermentation, a behavior reported in previous studies that used berries in baked products [60,61].

3.2. Physical Properties and Colorimetric Analysis

3.2.1. Color

In baking, color is generated through a series of complex chemical reactions between carbohydrates and proteins during the baking process, influenced by both the formulation and the process conditions [62]. Changes in color parameters are directly related to the characteristics of the raw materials used [63]. Anthocyanins, flavonoids are responsible for the red, purple, and blue hues of various fruits [64]. In S. peruviana, the anthocyanins responsible for the characteristic color are cyanidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin-3-sambubioside, and cyanidin-3-sambubioside-5-glucoside [65]. These compounds are responsible for the distinctive pigmentation of panettones enriched with S. peruviana.

The color parameters of the panettones formulated with the incorporation of S. peruviana flour are presented in Table 3. Luminosity (L*) decreased from 56.79 (TP0) to 39.54 (SP10), demonstrating a darkening of the product. This effect is due to the phenolic pigments inherent to S. peruviana, primarily anthocyanins, which degrade during the baking process [66,67], and it also may be attributed to the caramelization reactions of the sugars in S. peruviana [68].

Table 3.

Texture and color characteristics of panettones with S. peruviana flour incorporation.

The incorporation of S. peruviana caused the parameter (a*) to increase from 2.39 to 7.75, indicating a greater intensity of red tones. The presence of anthocyanins in a slightly acidic pH is the cause of this chromatic effect, in which red tones prevail over bluish tones [69]. For the spectrum (b*), it decreased from 25.31 to 20.91, showing a change in tone characteristic of traditional panettone (yellow). The decrease in the spectrum (b*) is due to the effect of adding S. peruviana flour, which altered the color (dark and reddish). In a similar way, Abdollahi Moghaddam et al. [31] reported a decrease in L* values in fried cookies (from 86.30 to 72.85). The total chromatic intensity of the final product did not undergo significant changes, although the chroma index (c*) varied from 25.42 to 22.30, indicating that the hue was modified. On the other hand, for the hue angle (h*) the values decreased from 84.63 to 69.64, indicating that the yellow color becomes darker and more reddish as the concentration of S. peruviana increases given that anthocyanins are the polyphenolic compounds most responsible for the color of panettone [70].

Regarding the color difference ∆E, the values increased from 45.53 to 61.26 after the incorporation of S. peruviana. These values show differences that are easily noticeable to the naked eye [71]; thus the inclusion of S. peruviana affected the treatments compared to the control. Finally, the whiteness index (WI) decreased from 49.84 (TP0) to 32.86–35.55 in the EP8 and EP10 formulations, which is attributed to the interaction between the phenolic pigments of S. peruviana and the panettone matrix that leads to a gradual loss of brightness.

3.2.2. Texture

The hardness of the crumb, defined as the maximum force required to break it, is an essential parameter in bakery products, as it is closely linked to the consumer’s perception of freshness [72]. It also shows a negative correlation with the overall quality of the product [73], which makes it necessary to control this parameter in order to maintain the acceptability of the product. In this study, the hardness of the panettone ranged from 20.23 to 77.15 N (Table 3). The experimental panettone EP10 showed a significantly higher hardness value com-pared to the other panettone formulations. Studies by [35,74] using lower or similar concentrations (15%; 3%; and 6%; 9% and 15%) reported a higher hardness profile than that observed in this study.

Deformation (mm) is the product’s ability to yield to force without breaking. This parameter allows the effect of instrumental testing to be objectively evaluated and measured, accurately indicating the physical characteristics of the product [75]. In this investigation, all formulations ranged between 5.99 and 6.00 mm. The incorporation of S. peruviana did not significantly alter the plasticity of the crumb, which may be attributed to effect of the fiber structure and moisture retention promoted by the polysaccharides in S. peruviana, allowing for the maintenance of an airy and cohesive texture [76].

As for elasticity (mm), a textural property that represents the sample’s ability to recover after deformation [77], values ranged from 2.75 to 3.45 mm and there was no significant difference among the samples (p > 0.05). As observed in this study and other reports, the texture parameters of bakery products are directly influenced by the addition of byproduct flour [78,79,80]. However, the addition of S. peruviana did not significantly affected the texture of the panettones, as the starch was able to stabilize acidic emulsions due to its resistance to low pH [81].

3.3. Bioactive Properties

Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Capacity (AC)

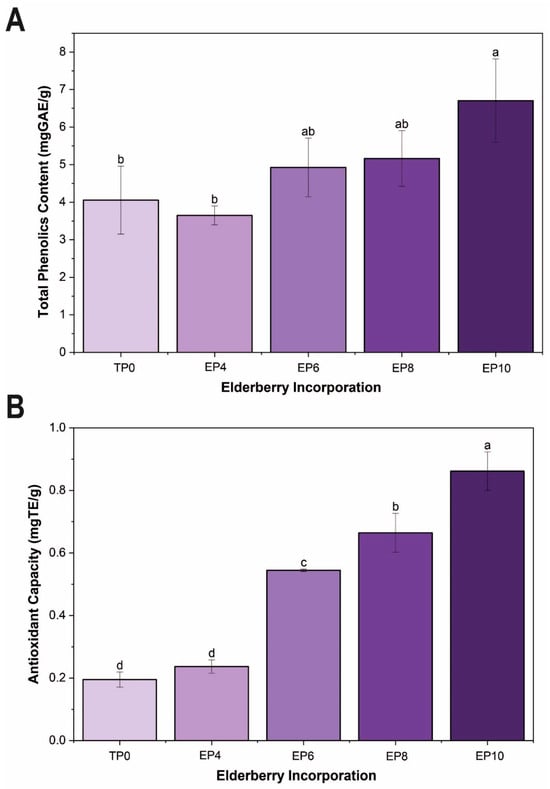

The TPC can vary significantly depending on its geographic origin and the methods used to obtain the phenolic extracts [82]. In Figure 2A, the results obtained from the TPC quantification in the panettones enriched with S. peruviana flour are presented. When S. peruviana flour was incorporated into the experimental formulations EP6, EP8, and EP10, a significant increase (p < 0.05) in TPC was observed compared to the control (TP0) and the EP4 treatment. The lowest values were observed in TP0 and EP4 (3.6 and 4.0 mg GAE/g, respectively), while the highest was in EP10 (6.7 mg GAE/g). This indicates that adding S. peruviana at high concentrations increases the content of bioactive phenolic compounds [83]. The increase in TPC can be attributed to the anthocyanin content in S. peruviana and the interaction between phenolic compounds and the food matrix. In comparison, Ferreira et al. [84] reported much higher values (820 ± 45 mg GAE/100 g) in their treatments, highlighting the differences in TPC levels depending on the formulations and specific conditions of each study.

Figure 2.

Bioactive properties: (A) Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g), (B) antioxidant capacity (mg TE/g) of panettones with S. peruviana flour incorporation. Different letters in the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between samples.

The antioxidant capacity (AC) of a fruit is related to the synergistic impact of the phenolic compounds it contains [85]. In Figure 2B, the antioxidant capacity, expressed in mg TE/g (Table S2), increased progressively increase upon incorporation of S. peruviana, a trend similar to that of TPC. The EP10 treatment reached a maximum value of 0.9 mg TE/g, which is significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the TP0 control (0.2 mg TE/g). This increase confirms the relationship between phenolic content and total antioxidant capacity, as phenolic compounds act as hydrogen donors and free radical scavengers [15,83].

Our findings are consistent with previous studies in which S. peruviana extracts exhibited high antioxidant capacity due to their high concentration of anthocyanins and flavonoids [86]. This pattern is also evident in other fruits with a high anthocyanin content, such as pomegranates, where the total amount of phenols was reported to be 371.19 ± 8.12 mg GAE/g and that of anthocyanins was 300.68 ± 7.56 mg/g [72]. However, the relationship between TPC and AC is not always linear, as it depends on the chemical structure of the phenols and the synergy among them [87]. Furthermore, the food matrix and processing conditions, such as temperature or oxy-gen exposure, can alter both the availability and the activity of antioxidants [88].

3.4. FT-IR Spectroscopy

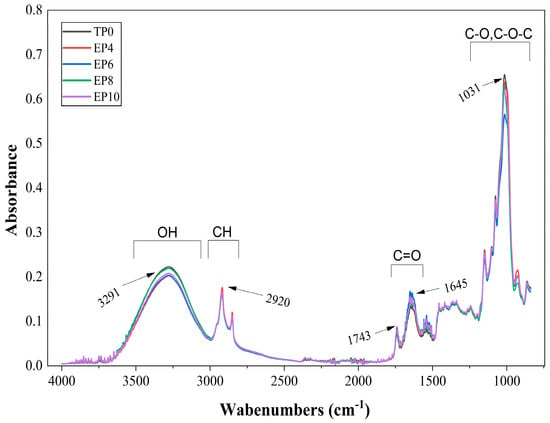

In Figure 3, the spectral analysis revealed different signal intensities among the treatments, suggesting differences in the relative abundance of functional groups [89]. The peak at 3291 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group (O–H), characteristic of polysaccharides, proteins, and phenolic compounds present in the matrix. The incorporation of S. peruviana affected the intensity and broadening of the band, especially in the EP8 and EP10 treatments, suggesting a higher presence of polar groups and the formation of hydrogen bonds between the phenolic compounds of S. peruviana and the macromolecules in the dough (gluten proteins and starch polysaccharides). These interactions modified the structural organization of the network, increasing binding and water retention capacity without compromising its basic integrity, i.e., without disrupting the gluten network responsible for the characteristic texture of panettone [90]. The peak at 2920 cm−1 (C–H group) corresponds to the asymmetric stretching of methylene (-CH2-) and methyl (-CH3) groups, characteristic of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids [91]. This slight vibration is attributed to the protein–polyphenol interaction, which generates a less dense gluten network in relation to the incorporation of S. peruviana.

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectra of panettones with S. peruviana flour incorporation.

At the peak of 1743 cm−1 (C=O group), a stretching band of the carbonyl group (C=O) is observed, characteristic of lipid esters and the amide I groups of gluten proteins [92]. In treatments with higher S. peruviana incorporation, a decrease in the vibration of this band was noted, likely due to interactions between phenolic compounds and protein or lipid carbonyl groups. The absorption peak at 1645 cm−1 corresponds to C=O stretching vibrations (amide I and amide II), typical of gluten proteins [93]. The peak at 1031 cm−1 represents the stretching vibration of glycosidic C–O and C–O–C bonds, characteristic of polysaccharides (starch and cellulose) [94].

Similar spectral patterns have been observed in other hydrocolloid systems. Rafe et al. [95] reported that basil seed gum exhibited characteristic peaks at 1603 cm−1 (COO− stretching of carboxylate salts) and 1023 cm−1 (C–O–C glycosidic bonds), demonstrating the typical structure of polysaccharides and their ability to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Like basil seed gum, S. peruviana contains polysaccharides that contribute to glycosidic bond formation and enhance water retention capacity in the panettone matrix.

Phenolic compounds and sugars from S. peruviana favored intermolecular bonding (hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions) with the nutrients in panettone, such as proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides. During baking, temperature and humidity conditions induced thermal and condensation reactions among these compounds, resulting in chemical modifications in the matrix. Indeed, the FT-IR spectra in our study revealed slight molecular changes that did not significantly alter the main structure of the panettone [91].

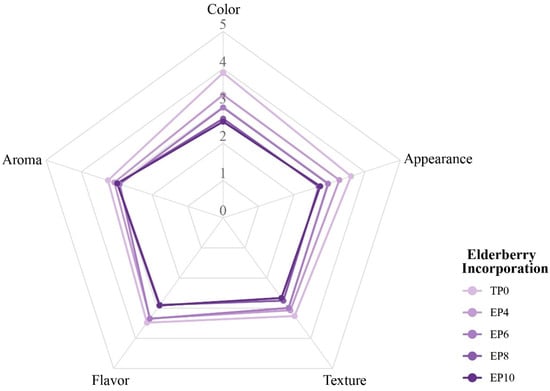

3.5. Sensory Analysis

The sensory analysis of the panettones formulated with different levels of S. peruviana incorporation revealed that treatment TP0 obtained higher scores for color (4.0) and flavor (3.8), indicating greater overall acceptance. The treatments with the highest incorporation of S. peruviana (SP8 and SP10) experienced a slight decrease in color and flavor, while the texture and aroma attributes remained similar. The incorporation of S. peruviana into the experimental panettones SP4 and SP8 increased their sensory acceptance, as it im-proved their color and aroma without significantly affecting the texture.

Due to the large size of the sensory panel and for practical reasons, we considered the 5-point Likert-type hedonic scale to be useful, as it was well suited to our semi-trained panelists, reduced the complexity of the evaluation, and provided valid responses. While it is true that some studies use 9-point scales, other authors have shown that 5 and 7 point scales yield consistent and reliable results [44], which aligns with the findings of our study (Figure 4 and Table S3).

Figure 4.

Sensory attributes of panettones with S. peruviana flour incorporation.

This behavior is consistent with other studies, which indicated that low and moderate concentrations of freeze-dried fruit can improve attributes such as color and aroma, while higher levels may cause undesirable changes, such as color darkening [59,96]. In general, the anthocyanins present in S. peruviana are sensitive to pH variations and the thermal conditions of baking, which can affect the product’s color stability [97,98]. In terms of flavor, the incorporations used in our study contributed positively to the overall perception [61]. Finally, the texture showed no significant changes, suggesting that the incorporation of S. peruviana does not significantly affect the gluten network structure and maintains an airy and cohesive texture, as reported in previous studies on plant-based substitutes in baking [15].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of S. peruviana flour as a functional ingredient in panettone production, significantly enhancing nutritional and bioactive properties by increasing phenolic compound content and antioxidant capacity, thereby adding value to the panettone in line with the growing demand for functional foods. Although an improvement in fiber content and a change in color parameters due to anthocyanins were observed, hardness gradually increased in formulations with higher levels of S. peruviana, which could pose a challenge to sensory acceptance by consumers. The sensory acceptance results indicate that the EP6 formulation offers a moderate balance between the functional characteristics and the organoleptic quality of the panettone. From a technological standpoint, this research provides an innovative option for valorizing Andean S. peruviana in baked products, promoting the sustainable use of native resources and the development of functional foods with industrial viability.

While this study demonstrates the functional potential of S. peruviana, future research should analyze its stability during storage, the evolution of bioactive compounds, their effect on preservation, and other textural properties of the product. Subsequent studies could also address differences in the characteristics of elderberry flour as a food ingredient, taking into account its origin and production conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010068/s1, Table S1: Data collection, Table S2. Total Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity, and Table S3. Sensory Analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.A., E.A.A.-S., R.J.C. and L.D.M.-A.; methodology, J.R.A., E.A.A.-S., A.J.V., R.J.C., H.O.A.C., L.D.M.-A. and I.Y.; software, A.J.V., R.O.-D., S.G.C. and I.Y.; validation, E.A.A.-S., L.D.M.-A., C.R.B.-Z., S.G.C. and I.S.C.-C.; formal analysis, J.R.A., R.O.-D., R.J.C., C.R.B.-Z. and S.G.C.; investigation, J.R.A., E.A.A.-S., L.D.M.-A. and S.G.C.; resources, J.R.A., E.A.A.-S., L.D.M.-A. and S.G.C.; data curation, J.R.A., R.J.C., R.O.-D., L.D.M.-A. and I.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.A., R.O.-D., E.A.A.-S., L.D.M.-A., C.R.B.-Z. and I.S.C.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.R.A., S.G.C., E.A.A.-S., C.R.B.-Z. and I.S.C.-C.; visualization, J.R.A., A.J.V., R.J.C., L.D.M.-A. and R.O.-D.; supervision, E.A.A.-S., L.D.M.-A. and S.G.C.; project administration, J.R.A., E.A.A.-S. and L.D.M.-A.; funding acquisition, E.A.A.-S. and S.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the resources of project C.U.I. 2590707 “Mejoramiento del Servicio de Promoción de la Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica en Centro de Investigación en Ciencias y Tecnología de Alimentos”—CIENCYTEC de la UNTRM distrito de Chachapoyas de la provincia de Chachapoyas del departamento de Amazonas. The APC was funded by Vicerrectorado de Investigación—Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the CIENCYTEC project of the Institute of Research, Innovation, and Development for the Agricultural and Agroindustrial Sector (IIDAA), the Experimental Center for Agroindustrial Research and Innovation (CEIIA), the Soil and Water Research Laboratory (LABISAG) of the Institute for Sustainable Development of the Ceja de Selva (INDES CES), and the Engineering Laboratory of the Faculty of Engineering and Agricultural Sciences at the National University Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza of Amazonas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Zábó, V.; Varga, J.T.; Bálint, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Rząsa-Duran, E.; Varga, P. Functional Foods in Modern Nutrition Science: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donn, P.; Prieto, M.A.; Mejuto, J.C.; Cao, H.; Simal-Gandara, J. Functional foods based on the recovery of bioactive ingredients from food and algae by-products by emerging extraction technologies and 3D printing. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Casolani, N.; Ruggeri, M.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Aiello, F.; Chiodo, E.; Martuscelli, M.; Restuccia, D.; Mastrocola, D. Sensory Evaluation and Consumers’ Acceptance of a Low Glycemic and Gluten-Free Carob-Based Bakery Product. Foods 2024, 13, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J.; Gouveia, I. Food Wastes and Microalgae as Sources of Bioactive Compounds and Pigments in a Modern Biorefinery: A Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.L.; Santos, L.F.P.; Barreto, G.d.A.; Leal, I.L.; Oliveira, F.O.; Conceição dos Santos, L.M.; Ribeiro, C.D.F.; Minafra e Rezende, C.S.; Machado, B.A.S. Development and characterization of panettones enriched with bioactive compound powder produced from Shiraz grape by-product (Vitis vinifera L.) and arrowroot starch (Maranta arundinaceae L.). Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, E.G.; dos Passos, C.M.; Levy, R.B.; Bortoletto Martins, A.P.; Mais, L.A.; Claro, R.M. What to expect from the price of healthy and unhealthy foods over time? The case from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G. Development and Characterisation of Functional Bakery Products. Physchem 2024, 4, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, N.M.; Tram, N.B.; Cuong, D.G.; Duy, H.K.; An, L.T.; Tien, V.Q.; Giau, T.N.; Van Tai, N. Evaluation of functional characteristics of roselle seed and its use as a partial replacement of wheat flour in soft bread making. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Li, B.; Ma, M.; Shao, X. Health-promoting mechanisms and food applications of Sambucus nigra L.: A comprehensive review. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 134, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; He, X.Q.; Wu, D.T.; Li, H.B.; Feng, Y.B.; Zou, L.; Gan, R.Y. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.): Bioactive Compounds, Health Functions, and Applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 4202–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras-Mija, I.; Chirinos, R.; Garcia-Rios, D.; Aguilar-Galvez, A.; Huaman-Alvino, C.; Pedreschi, R.; Campos, D. Physico-chemical characterization, metabolomic profile and in vitro antioxidant, antihypertensive, antiobesity and antidiabetic properties of Andean elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. peruviana). J. Berry Res. 2020, 10, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.L.; Zapata, J.E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Release of Bioactive Peptides from Erythrina edulis (Chachafruto) Proteins under Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Albino, C.; Intiquilla, A.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Rodríguez-Arana, N.; Solano, E.; Flores, E.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Izaguirre, V.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Albumin from Erythrina edulis (Pajuro) as a promising source of multifunctional peptides. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.; Santos López, E.M.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Barros, L.; Lorenzo, J.M. Potential Use of Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) as Natural Colorant and Antioxidant in the Food Industry. A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seixas, N.L.; Paula, V.B.; Dias, T.; Dias, L.G.; Estevinho, L.M. The Effect of Incorporating Fermented Elderberries (Sambucus nigra) into Bread: Quality, Shelf Life, and Biological Enhancement. Foods 2025, 14, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intiquilla, A.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Arnao, I.; Peña, C.; Chavez-Hidalgo, E.L.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Erythrina edulis (pajuro) seed protein: A new source of antioxidant peptides. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, V.; Vescovo, D.; Melini, F.; Raffo, A. Bakery Product Enrichment with Phenolic Compounds as an Unexplored Strategy for the Control of the Maillard Reaction. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, S.; Oest, M.; Rohn, S. Interactions between phenolic acids, proteins, and carbohydrates—Influence on dough and bread properties. Foods 2021, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Chen, G.; Tilley, M.; Li, Y. Changes in phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities during the whole wheat bread-making process. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblitas, R.; Quispe-Sanchez, L.; Guadalupe, G.; Diaz, E.H.; Oliva, S.; Diaz-Valderrama, J.R.; Yoplac, I.; Valencia-Sullca, C.; Chavez, S.G. Physicochemical properties of bioactive bioplastics based on cellulose from coffee and cocoa by-products. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElGamal, R.; Song, C.; Rayan, A.M.; Liu, C.; Al-Rejaie, S.; ElMasry, G. Thermal Degradation of Bioactive Compounds during Drying Process of Horticultural and Agronomic Products: A Comprehensive Overview. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R.; Najda, A.; Sałata, A.; Krajewska, A. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Properties of Black Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.). Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2022, 21, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nakov, G.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Ivanova, N.; Stamatovska, V.; Dimov, I. Effect of grape pomace powder addition on chemical, nutritional and technological properties of cakes. LWT 2020, 134, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsido, S.F.; Welelaw, E.; Belachew, T.; Hensel, O. Effects of storage temperature and packaging material on physico-chemical, microbial and sensory properties and shelf life of extruded composite baby food flour. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamanca-Gonzales, N.C.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Quintana-Salazar, N.B.; Siche, R.; Silva-Paz, R.J. Influence of Preferments on the Physicochemical and Sensory Quality of Traditional Panettone. Foods 2022, 11, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.A.; Mohd Norzi, M.F.A.; Mohd Arshad, Z.I.; Mohd Azman, N.A.; Abdul Mudalip, S.K. Effect of spray drying parameters on the physicochemical properties and oxidative stability of oil from menhaden (Brevoortia spp.) and Asian swamp eel (Monopterus albus) oil extract microcapsules. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Weiss, J.; Kinchla, A.J.; Nolden, A.A.; Grossmann, L. Methods for testing the quality attributes of plant-based foods: Meat-and processed-meat analogs. Foods 2021, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.M.; Witte, F.; Terjung, N.; Weiss, J.; Gibis, M. Influence of Processing Steps on Structural, Functional, and Quality Properties of Beef Hamburgers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, B.M.; Das, A.K.; Alam, S.M.S.; Saqib, N.; Rana, M.S.; Sweet, S.R.; Naznin, T.; Hossain, P.; Sardar, S.; Hossain, Z.; et al. Effect of different drying techniques on the physicochemical and nutritional properties of Moringa oleifera leaves powder and their application in bakery product. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Métodos Oficiales de Análisis-Official Methods of Analysis, 22nd Edition 2023; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi Moghaddam, M.R.; Rafe, A.; Taghizadeh, M. Kinetics of color and physical attributes of cookie during deep-fat frying by image processing techniques. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanchi, M.; Sugianto, E.C.; Chau, A.; Khoddami, A. Quality Properties of Bakery Products and Pasta Containing Spent Coffee Grounds (SCGs): A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewko, P.; Wójtowicz, A.; Gancarz, M. Application of Conventional and Hybrid Thermal-Enzymatic Modified Wheat Flours as Clean Label Bread Improvers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Paz, M.F.; Marques, R.V.; Schumann, C.; Corrêa, L.B.; Corrêa, É.K. Technological characteristics of bread prepared with defatted rice bran. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2015, 18, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Šporin, M.; Avbelj, M.; Kovač, B.; Možina, S.S. Quality characteristics of wheat flour dough and bread containing grape pomace flour. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, R.A.; Santos, E.C., Jr.; Pinto, L.I.F.; Viana, J.D.R.; Lima, C.A.R.; Pontes, D.F. Propriedades texturométricas e sensoriais de pães formulados com polidextrose e brócolis em pó obtidos por massas congeladas. Blucher Chem. Eng. Proc. 2015, 1, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonfia-Essien, W.A.; West, G.; Alderson, P.G.; Tucker, G. Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of hybrid variety cocoa beans. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Beta, T. Identification and antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds during production of bread from purple wheat grains. Molecules 2015, 20, 15525–15549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniolli, A.; Becerra, L.; Piccoli, P.; Fontana, A. Phenolic, Nutritional and Sensory Characteristics of Bakery Foods Formulated with Grape Pomace. Plants 2024, 13, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Chacon, L.M.; Quispe-Sanchez, L.; Chicana, F.; Oblitas, R.; Huaman-Pilco, A.F.; Mori, S.; Oliva, M.; Yoplac, I. Biopolymers extracted from agro-industrial wastes of lucuma, avocado and rice for production of biodegradable trays. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, F.J.; Gidley, M.J.; Flanagan, B.M. Infrared spectroscopy as a tool to characterise starch ordered structure-A joint FTIR-ATR, NMR, XRD and DSC study. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 139, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Wang, Y.; Vongsvivut, J.; Ye, Q.; Selomulya, C. On surface composition and stability of β-carotene microcapsules comprising pea/whey protein complexes by synchrotron-FTIR microspectroscopy. Food Chem. 2023, 426, 136565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomei, P.A.; de Campos Serra, B.P.; Mello, S.F. Differences in the Use of 5- or 7-point Likert Scale: An Application in Food Safety Culture. Organ. Cult. Int. J. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, L.G.I.; Genevois, C.E.; Busch, V.M. Novel flours from leguminosae (Neltuma ruscifolia) pods for technological improvement and nutritional enrichment of wheat bread. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 2, 603p. [Google Scholar]

- Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, Package R version 1.3-7; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Momin, M.A.; Jubayer, M.F.; Begum, A.A.; Nupur, A.H.; Ranganathan, T.V.; Mazumder, M.A.R. Substituting wheat flour with okara flour in biscuit production. Foods Raw Mater. 2020, 8, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann-Porcel, M.V.; Rinaldoni, A.N.; Rodriguez-Furlán, L.T.; Campderrós, M.E. Quality assessment of dried okara as a source of production of gluten-free flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2934–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Salvador-Reyes, R.; Guillén-Sánchez, J.; Mori-Arismendi, S. Effect of partial substitution of wheat flour by soybean meal in technological and sensory characteristics of cupcakes for children of school age. Sci. Agropecu. 2016, 7, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.; Ponce Aquino, V.T.; Uriarte Dávila, J.R. Effect of partial substitution of wheat flour with okara flour in the elaboration of panettone. In Proceedings of the LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology, San Jose, Costa Rica, 17–19 July 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bucsella, B.; Molnár, D.; Harasztos, A.H.; Tömösközi, S. Comparison of the rheological and end-product properties of an industrial aleurone-rich wheat flour, whole grain wheat and rye flour. J. Cereal. Sci. 2016, 69, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemery, Y.; Holopainen, U.; Lampi, A.M.; Lehtinen, P.; Nurmi, T.; Piironen, V.; Edelmann, M.; Rouau, X. Potential of dry fractionation of wheat bran for the development of food ingredients, part II: Electrostatic separation of particles. J. Cereal. Sci. 2011, 53, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczkowska, E.; Serek, P. Health-Promoting Properties and the Use of Fruit Pomace in the Food Industry—A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Paz, R.J.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; Eguilas-Caushi, Y.M.; Padilla-Fabian, R.A.; Jamanca-Gonzales, N.C. Sensory Evaluation through RATA and Sorting Task of Commercial and Traditional Panettones Sold in Peru. Foods 2024, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Ramos-Escudero, F. Valorization of flours from cocoa, sinami and sacha inchi by-products for the reformulation of Peruvian traditional flatbread (‘Pan Chapla’). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, F.; Puppo, M.C.; Ferrero, C. Mesquite (Prosopis alba) flour as a novel ingredient for obtaining a “panettone-like” bread. Applicability of part-baking technology. LWT 2018, 89, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentscheva, G.; Milkova-Tomova, I.; Buhalova, D.; Pehlivanov, I.; Stefanov, S.; Nikolova, K.; Andonova, V.; Panova, N.; Gavrailov, G.; Dikova, T.; et al. Incorporation of the Dry Blossom Flour of Sambucus nigra L. in the Production of Sponge Cakes. Molecules 2022, 27, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesárová, A.; Bojňanská, T.; Solgajová, M.; Mendelová, A.; Kopčeková, J.; Kolesárová, A. The effects of the addition of lyophilized berry fruits on the leavening properties of dough and volume properties of bread. Food Feed. Res. 2025, 52, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascariu, O.E.; Israel-Roming, F. Bioactive Compounds from Elderberry: Extraction, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Processes 2022, 10, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topka, P.; Poliński, S.; Sawicki, T.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Tańska, M. Effect of Enriching Gingerbread Cookies with Elder (Sambucus nigra L.) Products on Their Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Glycation Properties, and Sensory Acceptance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkut, G.M.; Cakmak, H.; Kumcuoglu, S.; Tavman, S. Effect of quinoa flour on gluten-free bread batter rheology and bread quality. J. Cereal. Sci. 2016, 69, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira Soares Souza, F.; Rocha Vieira, S.; Leopoldina Lamounier Campidelli, M.; Abadia Reis Rocha, R.; Milani Avelar Rodrigues, L.; Henrique Santos, P.; de Deus Souza Carneiro, J.; de Carvalho Tavares, I.M.; de Oliveira, C.P. Impact of using cocoa bean shell powder as a substitute for wheat flour on some of chocolate cake properties. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Classification of fruits based on anthocyanin types and relevance to their health effects. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1301–13066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Finn, C.E. Anthocyanins and other polyphenolics in American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) and European elderberry (S. nigra) cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.F.R.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Heleno, S.A.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Anthocyanin profile of elderberry juice: A natural-based bioactive colouring ingredient with potential food application. Molecules 2019, 24, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oancea, S. A review of the current knowledge of thermal stability of anthocyanins and approaches to their stabilization to heat. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Monaco, R.; Miele, N.A.; Cabisidan, E.K.; Cavella, S. Strategies to reduce sugars in food. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 19, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Acylated anthocyanins from edible sources and their applications in food systems. Biochem. Eng. J. 2003, 14, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.J.; Xavier, M.F.; Quadri, M.G.N.; Quadri, M.B. Antocianinas: Uma breve revisão das características estruturais e da estabilidade. Rev. Bras. Agrociencia 2007, 13, 291–297. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5702886&info=resumen&idioma=ENG (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Mokrzyxki, W.S.; Tatol, M. Colour difference ΔE-A survey. Mach. Graph. Vis. Int. J. 2011, 20, 383–411. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3166160.3166161 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Sedighi, R.; Rafe, A.; Rajabzadeh, G.; Pardakhty, A. Development and Characterization of Calcium Ion-Enhanced Nanophytosomes Encapsulating Pomegranate Fruit Extract. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Lin, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q. Chickpea sourdough as a functional ingredient in gluten-free bread: Impact on quality attributes. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 172, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Tseng, A.; Cavender, G.; Ross, A.; Zhao, Y. Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Sensory Qualities of Wine Grape Pomace Fortified Baked Goods. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, S1811–S1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.M.; Guiné, R.P.F. Textural Properties of Bakery Products: A Review of Instrumental and Sensory Evaluation Studies. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, C.; Albrecht, A.; Elgeti, D.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Impact of gas formation kinetics on dough development and bread quality. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.; Guiné, R.; Fonseca, M.; Batista, L. Analysis of textural properties of gluten free breads. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2021, 34, 102–108. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10400.19/6717 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Beres, C.; Costa, G.N.S.; Cabezudo, I.; da Silva-James, N.K.; Teles, A.S.C.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P. Towards integral utilization of grape pomace from winemaking process: A review. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faki, R.; Gursoy, O.; Yilmaz, Y. Effect of Electrospinning Process on Total Antioxidant Activity of Electrospun Nanofibers Containing Grape Seed Extract. Open Chem. 2019, 17, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Iuga, M.; Zaharia, D.; Mironeasa, C. Rheological Analysis of Wheat Flour Dough as Influenced by Grape Peels of Different Particle Sizes and Addition Levels. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2019, 12, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funami, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Omoto, T.; Goto, Y.; Asai, I.; Nishinari, K. Effects of non-ionic polysaccharides on the gelatinization and retrogradation behavior of wheat starch☆. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Leonard, W.; Zhang, P. Phenolic compounds in Lycium berry: Composition, health benefits and industrial applications. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Ocampo, E.; Torrejón-Valqui, L.; Muñóz-Astecker, L.D.; Medina-Mendoza, M.; Mori-Mestanza, D.; Castro-Alayo, E.M. Antioxidant capacity, total phenolic content and phenolic compounds of pulp and bagasse of four Peruvian berries. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.S.; Silva, P.; Silva, A.M.; Nunes, F.M. Effect of harvesting year and elderberry cultivar on the chemical composition and potential bioactivity: A three-year study. Food Chem. 2020, 302, 125366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Montoya, Ó.; Vaillant, F.; Cozzano, S.; Mertz, C.; Pérez, A.M.; Castro, M.V. Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of tropical highland blackberry (Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) during three edible maturity stages. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Pando Bedriñana, R. The Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Microflora of Wild Elderberry in Asturias (Northern Spain): An Untapped Resource of Great Interest. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, I.; Kocakaya, S.O.; Ertas, A.; Erhan, B.; Kaplaner, E.; Oral, E.V.; Yilmaz-Ozden, T.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Ozturk, M.; Kolak, U. Selective in vitro and in silico enzymes inhibitory activities of phenolic acids and flavonoids of food plants: Relations with oxidative stress. Food Chem. 2020, 327, 127045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Wan, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, C.; Liu, D.; Gao, L.; Wang, M.; Wu, C.; Nabavid, S.M.; Daglia, M.; et al. Polysaccharides from Marine Enteromorpha: Structure and function. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calonico, K.; De La Rosa-Millan, J. Digestion-Related Enzyme Inhibition Potential of Selected Mexican Medicinal Plants (Ludwigia octovalvis (Jacq.) P.H.Raven, Cnidoscolus aconitifolius and Crotalaria longirostrata). Foods 2023, 12, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yao, J.; Wang, F.; Wu, D.; Zhang, R. Extraction, isolation, structural characterization, and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from elderberry fruit. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 947706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandee, Y.; Uttapap, D.; Mischnick, P. Yield and structural composition of pomelo peel pectins extracted under acidic and alkaline conditions. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; Xing, M.; Huang, H.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Wang, J. Flash nanoprecipitation enables regulated formulation of soybean protein isolate nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 131, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.H.; Sung, J.M.; Park, J.; Park, J.D.; Park, E.Y. Sucrose-induced structural modification of in situ exopolysaccharides: Effects on rheological and baking properties of gluten-free sourdough. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, X.; Qin, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Bao, M. Characterization and protective effect against ultraviolet radiation of a novel exopolysaccharide from Bacillus marcorestinctum QDR3-1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafe, A.; Razavi, S.M.A. Effect of thermal treatment on chemical structure of β-lactoglobulin and basil seed gum mixture at different states by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 2652–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenutti, L.; Moura, F.M.; Zanghelini, G.; Barrera, C.; Seguí, L.; Zielinski, A.A.F. An Upcycling Approach from Fruit Processing By-Products: Flour for Use in Food Products. Foods 2025, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enaru, B.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stǎnilǎ, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: Factors affecting their stability and degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, P.; Parra, F.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Sepúlveda Chavera, G.F.; Parra, C. Chemical Characterization, Nutritional and Bioactive Properties of Physalis peruviana Fruit from High Areas of the Atacama Desert. Foods 2021, 10, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.