1. Introduction

The sustainable utilization of residual biomass constitutes a fundamental pillar in the transition toward a circular economy and a decarbonized energy system. Each year, the agroindustrial sector generates substantial quantities of lignocellulosic residues that are frequently undervalued or left unexploited, resulting in significant environmental management challenges and the inefficient loss of potentially valuable resources. In response to this issue, a wide range of biomass conversion pathways—including pyrolysis, gasification, and fermentation—have been developed to transform these residues into higher-value products such as biofuels, fertilizers, and platform chemicals [

1,

2,

3].

Although the theoretical energy potential of global biomass resources could exceed current energy demand, reaching values as high as 1100 EJ, existing assessments vary considerably. This variability reflects the lack of a unified consensus regarding the actual contribution that biomass may offer to future energy systems, highlighting the substantial uncertainty that still characterizes this field [

4].

Within this broader framework, the pecan production chain generates a significant volume of woody residues derived from the pruning of

Carya illinoinensis trees. In Mexico, this biomass stream represents a largely underutilized resource, despite the fact that the country accounts for approximately 40% of global pecan production, an activity that contributes nearly 1.4% to the national gross domestic product. Furthermore, exports exceeded 280 thousand tons in 2016 [

5]. Consequently, the energetic valorization of lignocellulosic residues from pecan pruning emerges as a promising opportunity for bioenergy development in regions with extensive pecan cultivation.

Lignocellulosic biomass is one of the most abundant renewable resources and is primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which together form the structural matrix of the plant cell wall. Cellulose consists of long, linear chains of glucose units linked by β-(1→4) glycosidic bonds and provides rigidity and mechanical strength. Hemicellulose acts as an amorphous supporting polymer that connects cellulose and lignin, while lignin confers additional structural stability and protection against chemical, biological, and mechanical degradation. This highly ordered and hierarchical organization significantly limits access to the structural polysaccharides, particularly cellulose [

6,

7].

Despite being composed of glucose units, cellulose cannot be efficiently hydrolyzed by humans and other mammals due to the nature of its glycosidic bonds, as well as its high crystallinity and structural complexity. In contrast, certain herbivorous animals, such as ruminants, host complex microbial consortia in their digestive systems that produce specific enzymes, including cellulases, which enable the degradation of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., grasses) and the subsequent utilization of its components as sources of energy and nutrients [

8,

9].

Analogously, industrial processes aimed at the valorization of lignocellulosic biomass require the implementation of pretreatment stages to overcome its inherent recalcitrance and to maximize resource utilization. These pretreatments may involve physical (mechanical or thermal), chemical, or biological methods, or combinations thereof, and are primarily intended to alter, degrade, or redistribute cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. By modifying the structure and physicochemical properties of biomass, pretreatment enhances accessibility to its constituent fractions, thereby increasing process efficiency, product yields, and selectivity toward desired end products [

10].

In this context, biomass pretreatment is particularly critical for energy applications, as it reduces the intrinsic heterogeneity of the material and adjusts its properties to meet the requirements of the selected conversion process. Among the most relevant pretreatment steps is drying, since high moisture content reduces energy efficiency by consuming a portion of the supplied heat for water evaporation. Moreover, moisture content influences reaction kinetics, thermal control, and product composition, especially in biomass combustion processes [

11].

Another key pretreatment aspect is particle size reduction and control. Size reduction and homogenization enhance heat and mass transfer, promote more uniform heating, and improve process reproducibility in biomass pyrolysis systems. Nevertheless, excessively small particle sizes may increase pretreatment energy consumption and introduce operational challenges. Therefore, particle size must be optimized according to the reactor configuration and the specific conversion technology employed [

12,

13].

Another representative example of biomass pretreatment is torrefaction, which is widely applied as a preliminary step prior to the gasification of lignocellulosic materials. Torrefaction can be regarded as a form of low-temperature slow pyrolysis, typically carried out within a temperature range of approximately 200–300 °C [

14], during which partial degradation of the main biomass constituents—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—occurs. As a result, a solid product with improved physicochemical properties is obtained, which, when used as feedstock for gasification, typically leads to a reduced formation of tar compounds [

15].

In addition, this mild pyrolytic treatment increases both the bulk density and the energy density of biomass, while enhancing its hydrophobicity. These changes facilitate pelletization, storage, and handling, and contribute directly to more stable gasifier operation and to the production of higher-quality synthesis gas. For these reasons, biomass pyrolysis has attracted growing interest not only as a direct route for biofuel production but also for its strategic role as a pretreatment step in the gasification of lignocellulosic biomass [

16].

In this context, pyrolysis is a thermochemical conversion pathway capable of transforming lignocellulosic biomass into syngas, condensable vapors, and biochar [

17]. These products have a wide range of potential applications, including use as alternative fuels, soil amendments, and components of carbon capture and storage (CCS) strategies [

18]. However, conventional pyrolysis typically requires an external heat supply at temperatures between 200 and 600 °C, which is commonly provided through the combustion of fossil fuels or a fraction of the biomass itself. This configuration results in direct greenhouse gas emissions and reduces both the overall energy efficiency and the net carbon performance of the process [

19].

Consequently, a central technological challenge lies in decarbonizing the thermal energy input required by thermochemical conversion processes. Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) has emerged as a promising alternative capable of delivering high-temperature heat through concentrated solar radiation, thereby eliminating the need for hydrocarbon combustion and substantially reducing associated emissions [

20]. Several CSP configurations—including parabolic troughs, dual-concentration systems, parabolic dishes, and heliostat fields—are capable of achieving temperatures ranging from approximately 500 °C to above 1500 °C [

21].

Accordingly, multiple studies have investigated the feasibility of solar-driven pyrolysis using different reactor configurations. Notable examples include research on agroindustrial residues such as nut shells and pecan pruning wood, conducted in both Auger and batch reactors powered by concentrated solar energy, either through a solar furnace or a solar simulator [

22,

23].

The integration of solar energy with biomass pyrolysis remains challenging due to the intrinsic complexity of both systems. Pyrolysis involves a highly intricate set of physicochemical transformations characterized by simultaneous solid–liquid–gas interactions that typically occur above 200 °C under inert conditions. This complexity arises from the heterogeneous nature of biomass, which is primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, each exhibiting distinct decomposition temperature ranges and kinetic behaviors. Furthermore, the process is inherently multifactorial and strongly influenced by operational variables such as temperature, heating rate, vapor residence time, sweep gas composition and flow rate, pressure, particle size, moisture content, and feedstock composition [

24,

25].

These variables not only control product distribution but also govern the overall energy balance of the process. Although pyrolysis is generally treated as an endothermic phenomenon, recent studies have provided clear evidence of exothermic events during biomass decomposition [

26]. For example, the phenomenon referred to as pyrolysis runaway has been observed during the thermal conversion of agroindustrial potato residues, where sudden temperature spikes were detected in a radiantly heated packed-bed reactor [

27]. Such findings demonstrate that the thermal behavior of biomass cannot be attributed solely to external heating conditions; rather, it is strongly influenced by intrinsic feedstock properties and potential catalytic effects arising from inorganic constituents or reactor materials. In this context, the identification of exothermic and endothermic patterns constitutes an important aspect of the present experimental work, as similar phenomena may have occurred in previous solar pyrolysis studies involving nut shells [

23] and were anticipated during the pyrolysis of woody pruning residues. Overall, these and other experimental investigations have demonstrated that CSP technology is capable of supplying sufficient thermal energy to sustain thermochemical conversion processes, positioning solar-driven systems as attractive candidates for direct biofuel production and high-heat-demand biomass pretreatment applications.

Additionally, given the complexity arising from the occurrence of multiple simultaneous reactions, a common strategy to facilitate the understanding of the process is to divide the information associated with the overall conversion into more manageable phases. Numerous authors describe three main stages—drying, active pyrolysis, and passive pyrolysis—generally associated with the decomposition of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, respectively, although additional sub-stages have been proposed, particularly for lignin conversion [

28]. This conceptual framework is most frequently applied in thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), where the derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) signal is used to identify distinct decomposition events [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Despite its widespread use in TGA, the literature reveals a gap: derivative-based analytical tools are rarely applied to experimental data acquired outside thermogravimetric instruments. Nevertheless, the analysis of temperature profiles and their corresponding derivatives (heating rates) in chemical reactors has proven to be a valuable approach, yielding clear and informative results. In particular, such methods have enabled the identification of relevant findings in studies aimed at detecting evidence of exothermic events during the pyrolysis of various lignocellulosic materials [

35,

36,

37].

Therefore, further exploration and systematic application of these analytical tools are warranted. This gap motivated the development of an enhanced data analysis methodology based on the evaluation of temperature derivatives obtained from sensor-acquired data in experimental reactor prototypes, with the objective of identifying, examining, and interpreting thermal events. The methodological contribution of the present work lies precisely in adapting derivative-based interpretation to solar-driven pyrolysis experiments, as described in the subsequent sections.

In this study, the solar pyrolysis of woody biomass derived from

Carya illinoinensis pruning (CaEX) is investigated using a batch reactor heated by a solar simulator. This work forms part of a broader research effort that previously examined the solar pyrolysis of pecan nut shells (WSSP) under equivalent radiative and experimental conditions [

23].

The main objective of this study is to identify and characterize the drying, active pyrolysis, and passive pyrolysis stages of CaEX under solar heating. This objective is addressed through two specific aims: (1) to apply, refine, and validate an improved solar experimental methodology used in previous work, and (2) to compare the thermochemical behavior of CaEX and WSSP originating from the same tree, with particular emphasis on temperature peak dynamics and product characterization. Preliminary results indicated that bulk density plays a crucial role in determining both the resolution and intensity of the detected temperature peaks. Because the CaEX samples exhibited approximately half the bulk density of the WSSP samples, the mass introduced into the reactor was proportionally reduced, leading to diminished interpretative clarity. For this reason, additional elements were incorporated into the analytical methodology, which are presented and discussed in this manuscript.

2. Materials and Methods

The raw material used in this experimental campaign consisted of woody biomass obtained from the pruning of Carya illinoinensis trees. Experiments conducted with this feedstock are hereafter referred to as CaEX. As a physical pretreatment, the material was mechanically ground using a wood chipper and subsequently sieved to obtain a controlled particle size range of approximately 1–4 mm. This range was selected based on preliminary experiments, which indicated that particles smaller than 1 mm caused clogging in the experimental system piping, whereas particles larger than 4 mm hindered adequate thermal contact with the internal thermocouple.

The biomass was deliberately not dried prior to the experiments in order to allow for in situ observation of the drying stage during solar heating. For each solar pyrolysis experiment, a biomass mass of approximately 25.5 g was used. This amount filled the internal volume of the reactor, which has an approximate capacity of 115 cm3.

A comprehensive characterization of the woody raw material was subsequently performed using standardized analytical techniques to obtain the fundamental properties required for further analysis. Proximate analysis was conducted to determine moisture content following the NREL/TP-510-42621 method, volatile matter content according to ASTM E872-82 (2019) [

38], and ash content using the NREL/TP-510-42622 method. Fixed carbon was calculated by difference. Ultimate analysis was carried out to determine the elemental composition (C, H, N, and S) using a PerkinElmer PE 2400 elemental analyzer, with all measurements performed in triplicate. Oxygen content was calculated by difference. The initial bed bulk density was measured in accordance with the ISO 17828:2015 standard [

39], and a statistical average was obtained using graduated cylinders and an analytical balance to ensure measurement precision. The higher heating value (HHV) was estimated using the methodology proposed by Channiwala and Parikh [

40].

Additionally, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed over a temperature range of 30–900 °C. For TGA measurements, biomass samples were further reduced to a particle diameter smaller than 1 mm. Experiments were conducted under an inert nitrogen (N2) atmosphere, with a sweep gas flow rate of 40 cm3/min and a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min.

The experimental system employed in this study (

Figure 1) consisted of four main components: (i) a concentrated solar radiation simulator, (ii) a cylindrical batch reactor, (iii) a gas cooling and cleaning system, and (iv) a gas chromatography unit. Thermal energy was supplied by a 7 kWe solar simulator equipped with a xenon lamp, in which radiation was concentrated using an ellipsoidal mirror. The net incident radiative power on the focal plane—corresponding to one face of the reactor—was used to heat the system at three constant thermal power levels: 234 W, 482 W, and 725 W, referred to as low, medium, and high power, respectively.

A cylindrical stainless-steel reactor with a mass of 1260 g and a maximum volumetric capacity of approximately 115 cm3 was operated in batch mode. The front face of the reactor consisted of a flat circular section with a diameter of 6 cm, resulting in an irradiated area of 28.27 cm2. Argon (Ar) was used as the carrier gas to ensure an inert atmosphere and was supplied at a constant volumetric flow rate of 1 L/min.

Thermal monitoring was performed using seven thermocouples strategically distributed throughout the system (see

Figure 1). Thermocouples T1 and T2 measured the external surface temperatures of the reactor front (irradiated) and rear faces, respectively. Thermocouples T3 and T4 recorded the external surface temperatures at the top and bottom of the reactor. Thermocouple T5 was positioned inside the reactor in direct contact with the biomass bed to measure the internal bed temperature. Thermocouple T6 measured the temperature of the pyrolysis gases at the reactor outlet, while T7 was located inside the tar trap to monitor the condensation temperature.

The composition of the non-condensable gases was analyzed online using an Agilent 490 Micro Gas Chromatograph. The system was equipped with two analytical columns: a Molsieve 5 Å column using argon as the carrier gas for the quantification of H2, CO, and CH4, and a Pora PLOT U column using helium as the carrier gas for the quantification of CO2. Gas composition measurements were recorded at 3 min intervals to evaluate the temporal evolution of gaseous species throughout the pyrolysis process.

2.1. Previous and Present Experimental Campaigns

The experiments presented in this work (CaEX) were preceded by three experimental campaigns conducted using the same reactor and solar heating system. The first campaign focused on the thermal characterization of the empty reactor, while the second involved experiments using volcanic rocks as an inert reference material [

41]. The third campaign employed walnut shells (WSSP) as feedstock and was structured into two experimental cases: Case A (CA), corresponding to the pyrolysis of the raw walnut shells, and Case B (CB), which evaluated the reheating of the biochar produced in CA under identical operating conditions.

This same two-case experimental protocol was subsequently applied to the CaEX experiments, enabling direct comparison among campaigns. To ensure consistent and comparable temperature–time profiles across all experimental campaigns, the solar simulator was operated at identical constant radiative thermal power levels of 234 W, 482 W, and 725 W. The most representative results obtained under these conditions are presented and discussed in the following section.

2.2. Data Analysis Methodology

The data analysis methodology was based on the evaluation of heating rates derived from the temperature–time profiles, expressed as first-order derivatives (dT/dt). This approach constitutes a key element of the improved methodology adopted in this study, as it allows the temperature-variation signal to be accentuated and facilitates the identification and differentiation of the various stages of the pyrolysis process.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Feedstock Characterization Results

The physical and chemical characterization of the woody pruning residue from

Carya illinoinensis is summarized in

Table 1. The table reports the results of the proximate and ultimate analyses, particle size distribution, higher heating value (HHV), and bulk density. These properties provide the fundamental baseline required to interpret the thermochemical behavior of the biomass under solar pyrolysis conditions.

The proximate analysis indicates a relatively high volatile matter content (69.09 wt%), which is characteristic of lignocellulosic biomass and suggests a strong propensity for devolatilization during pyrolysis. The ash content (2.97 wt%) is low, minimizing potential catalytic or inhibiting effects on thermal decomposition reactions. The fixed carbon fraction (21.13 wt%) reflects the potential for char formation during the later stages of pyrolysis.

Elemental analysis reveals carbon and oxygen contents of 45.28 wt% and 47.91 wt%, respectively, consistent with woody biomass reported in the literature. The HHV of 17.616 MJ/kg falls within the typical range for untreated hardwood residues, confirming the energetic suitability of the feedstock. The measured bulk density of 0.22 g/cm3 is particularly relevant for the present study, as it directly influences heat transfer, temperature evolution, and the resolution of thermally induced events during solar heating.

3.2. TGA Analysis and Interpretation

To facilitate the interpretation of both thermogravimetric and solar reactor experimental results, the pyrolysis process was divided into three principal stages following the nomenclature proposed by Narnaware and Panwar [

42]: (1) drying, (2) active pyrolysis, and (3) passive pyrolysis. Active pyrolysis is primarily associated with the decomposition of the more reactive components, namely hemicellulose and cellulose, whereas passive pyrolysis is attributed mainly to the degradation of the thermally more stable lignin fraction.

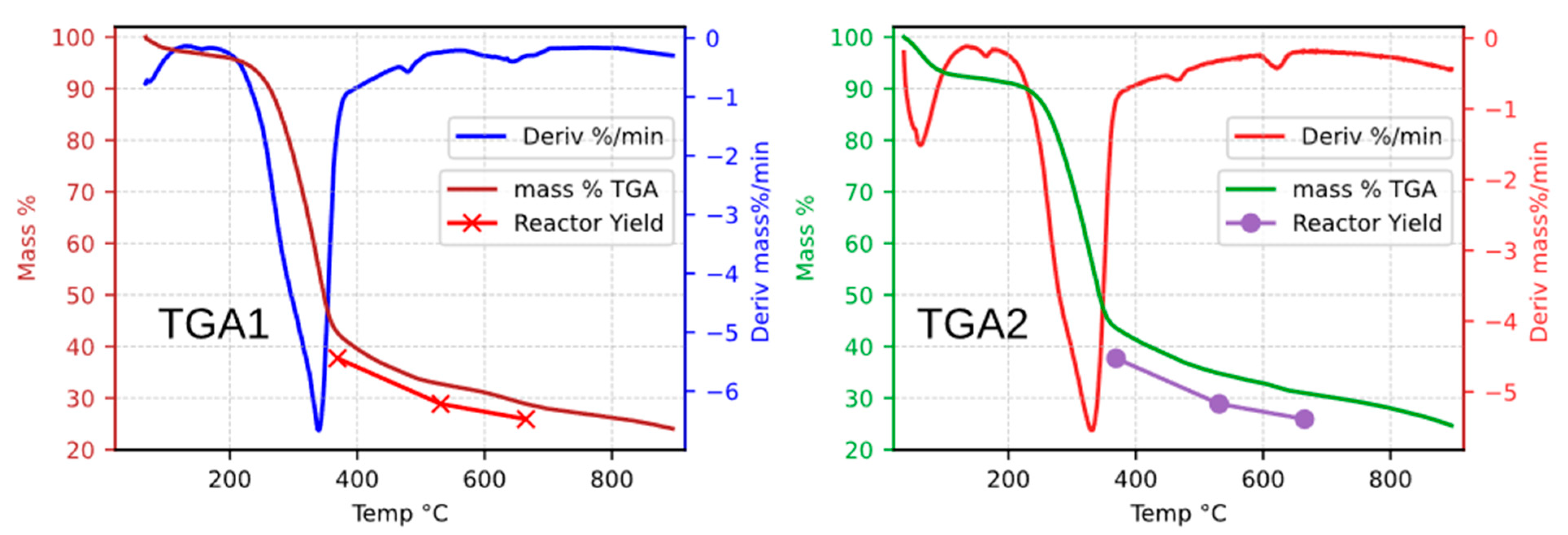

For practical purposes and to simplify the comparative analysis between TGA and solar reactor data, the active pyrolysis stage was delimited to the temperature range of 200–400 °C, as highlighted by the shaded region in

Figure 2. This interval was selected because it encompasses the onset and termination of the most pronounced peaks observed in the mass derivative (DTG) curve obtained during the TGA characterization of CaEX.

It is important to note that there is no strict consensus in the literature regarding the precise temperature at which biomass pyrolysis begins, either globally or for individual biomass components. Some authors, such as Uddin et al. [

43] and Mettler et al. [

44], report that the main thermal transformations become significant at temperatures close to 400 °C, although this threshold is strongly dependent on heating rate and experimental conditions.

Based on a review of the literature, the following component-specific behavior can be summarized:

Hemicellulose: This component is generally reported as the first biomass component to decompose, typically within the range of 225–325 °C [

45]. Chen et al. [

46] observed hemicellulose pyrolysis occurring between 223.4 and 332.8 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min. These temperature ranges are fully contained within the 200–400 °C interval adopted in the present study.

Cellulose: Zhang et al. [

47] investigated cellulose pyrolysis over a broad temperature range (200–800 °C) and reported that the most intense degradation reactions occur between 300 and 400 °C. Although cellulose decomposition extends beyond 400 °C, the concentration of major reactions within this interval supports its classification as part of the active pyrolysis stage. Reactions persisting at higher temperatures suggest that cellulose exhibits both active and passive pyrolytic behavior.

Lignin: This component is structurally distinct due to its aromatic backbone and methoxyl substituents and is composed of syringyl, guaiacyl, and p-hydroxyphenyl units. Thermal transformations involving these structures typically occur over a wide temperature range, with significant bond rearrangements reported between 400 and 600 °C, reflecting the high thermal stability of lignin-derived linkages [

48].

Given the structural complexity of lignin and the multitude of overlapping reactions involved, Leng et al. [

32] proposed a three-stage framework specifically for lignin pyrolysis: (1) drying, (2) active pyrolysis, and (3) passive pyrolysis. According to this classification, reactions such as demethoxylation, demethylation, and decarboxylation can begin at temperatures as low as 150 °C. Active pyrolysis was defined between 200 and 450 °C, where cleavage of C–C and β-O-4 linkages—the most abundant in lignin—occurs, leading predominantly to CO

2 formation. Above 450 °C, passive pyrolysis dominates, involving polymerization reactions leading to coke formation, degradation of aromatic structures, and rearrangement of side chains associated with the most thermally stable compounds [

32].

Overall, the current state of knowledge does not allow for a precise allocation of all biomass pyrolysis reactions into distinct and non-overlapping temperature intervals. Despite extensive research, the detailed mechanisms governing biomass pyrolysis and the individual behavior of its constituent components remain only partially understood. This lack of consensus highlights the need for further experimental and analytical studies to advance the understanding of this complex and multifactorial phenomenon [

17,

32,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Acknowledging these uncertainties, the present work adopts fixed temperature ranges to define the pyrolysis stages. These ranges were established based on the observable changes in the mass derivative profiles shown in

Figure 2 and were selected for practical reasons, in order to facilitate analysis and comparison with solar reactor experiments. The adopted classification is defined as follows:

3.3. Internal Thermal Evaluation of the Solar Reactor and Apparently Inert Behavior

As previously stated, the pyrolysis experiments involving Carya illinoinensis woody biomass (CaEX) are part of a broader experimental series. In order to experimentally determine the maximum temperatures achieved inside the reactor under the radiative thermal power supplied by the solar simulator, heating runs were initially conducted using an empty reactor and subsequently with volcanic stones.

The stone employed was a pyroclastic material known as volcanic scoria, which can be considered a porous form of basalt and is commonly referred to in Mexico as

tezontle. Although its chemical composition varies depending on geological formation processes, its melting point generally exceeds 1000 °C. Furthermore, while minor changes in the physical and chemical properties of volcanic stone may occur during heating, these alterations are sufficiently negligible that the material is commonly regarded as highly thermally stable [

54,

55].

Likewise, the stainless steel constituting the reactor structure is characterized by a high degree of thermal stability, with a melting point typically above 1300 °C [

56,

57,

58]. For these reasons, the experimental campaigns involving the empty reactor and the volcanic stone were treated as inert material experiments.

Figure 3 presents the internal reactor temperature (T5) recorded during experiments involving inert and apparently inert materials. The figure is organized such that the first column shows the temperature–time profiles, while the second column displays the corresponding heating rates (temperature derivatives). Each row corresponds to one of the radiative thermal power levels employed: 234 W (low), 482 W (medium), and 725 W (high).

The results corresponding to the pyrolysis of raw biomass (Case A experiments for both walnut shell and woody pruning) were excluded from this figure, as their heating patterns differed markedly from those observed for inert materials. In contrast, the results from Case B experiments (biochar heating) were included, as they exhibited heating patterns closely resembling those of the inert cases.

The heating behavior of the empty reactor and the volcanic stone was generally similar, although some differences were observed. In particular, the temperature of the volcanic stone increased more slowly, as the larger thermal mass acted as a thermal resistance, requiring a greater amount of energy to achieve the same temperature increase.

The heating-rate profiles shown in the second column of

Figure 3 exhibit an asymmetric Gaussian-like shape. Beyond the maximum heating-rate point, the temperature derivatives for the different materials tend to overlap as the system approaches steady-state conditions.

This heating-rate pattern is characteristic of the internal behavior of the reactor and would only be observed in devices with a similar design and heating conditions. Moreover, such behavior is typical of materials that primarily absorb sensible heat as their temperature increases. In the case of a phase change, the temperature derivative would be expected to approach zero, reflecting the absorption of latent heat.

Additionally, if endothermic or exothermic chemical reactions were occurring, deviations or fluctuations in the derivative curves would be expected at the corresponding temperatures. For this reason,

Figure 3 also includes the heating results for biochar derived from WSSP and CaEX, as these materials exhibited an apparently inert behavior under the experimental conditions investigated. The measurement and interpretation of gas production during biochar heating, which supports this observation, are discussed in a subsequent section.

3.4. Comparison Between CaEX and WSSP at Medium Power: 482 W

As previously mentioned, the results from the Case A (raw feedstock) experiments were excluded from the preceding figure because their heating patterns differed markedly from those observed for inert materials.

Figure 4 presents a direct comparison between the pyrolysis of walnut shells (WSSP: Sh) and woody pruning residues (CaEX: Wd). Only the experiments conducted at medium radiative power were included, as these conditions were identified as the most representative.

In

Figure 4a, a temperature plateau at approximately 100 °C is clearly observed during the heating of walnut shells, which is attributed to moisture evaporation. Although a similar phenomenon occurred during the heating of woody residues, the plateau is less distinct in the temperature profile. This behavior, however, becomes evident when analyzing the corresponding heating-rate curves (

Figure 4b), where the inflection point of the first derivative peak marks the onset of drying, followed by a decrease toward zero—a characteristic signature of a phase-change process.

Notably, the first derivative peaks for both materials occur at approximately 5.5 min, despite differences in their amplitudes. A second peak is also observed for both feedstocks, exhibiting comparable magnitudes but occurring at different times: around 16.5 min (≈200 °C) for CaEX and 22.5 min (≈270 °C) for WSSP. This temporal shift is primarily attributed to the difference in sample mass: 25.5 g for CaEX compared to 50.7 g for WSSP. The larger mass of the WSSP sample therefore imposed a greater thermal resistance, consistent with observations from the inert material experiments. This mass disparity is directly linked to the bulk density of each material, which was 0.232 g/cm3 for CaEX and 0.504 g/cm3 for WSSP—nearly a twofold difference.

Additionally, within the time interval of 30–38 min (approximately 435–455 °C), the derivative curve of WSSP (

Figure 4b) exhibits a pronounced valley that is absent in the CaEX experiments. Two plausible explanations can account for this behavior. First, tar formation and subsequent evaporation are known to be favored in the 300–500 °C temperature range, with maximum liquid yields during cellulose pyrolysis reported near 450 °C [

47,

59]. Second, this valley may be associated with preceding exothermic reactions. Highly exothermic events, commonly referred to as pyrolysis runaway, have been reported during the pyrolysis of various nut shells, including walnut shells [

60]. Although typically less intense, similar exothermic behavior has also been observed during wood pyrolysis [

26,

61].

Moreover, liquid pyrolysis products are prone to polymerization—a process that can occur even at ambient conditions but is significantly intensified between 100 and 400 °C [

62,

63,

64]. Because polymerization reactions are inherently exothermic [

65,

66], neither tar evaporation nor exothermic reactions can be ruled out, and it is likely that both phenomena occur concurrently.

Figure 4c,d present the outlet gas temperatures measured by thermocouple T6 and their corresponding derivatives. The initial peaks in the T6 derivatives coincide temporally with those observed in

Figure 4b, further linking these features to the drying stage. A similar valley is again observed during walnut shell pyrolysis in the T6 derivative (

Figure 4d), corresponding to the internal temperature behavior. Most notably, the T6 temperature profile for WSSP displays a sharp peak reaching nearly 90 °C shortly before the 30 min mark. This sudden increase strongly suggests the occurrence of an exothermic event, consistent with pyrolysis runaway behavior, whereas the temperature of the woody residue gases shows a comparatively smooth and continuous decline.

The third row of

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal evolution of non-condensable gases (H

2, CH

4, CO

2, and CO) produced during the pyrolysis of both feedstocks. Although distinct exothermic signatures are not readily discernible from the gas evolution profiles alone, a pronounced decrease in the production rates of all gases is observed after approximately 30 min (around 400 °C).

An unexpected observation was the detection of gaseous products as early as 10 min into the experiments, when the internal reactor temperature was only about 100 °C. This behavior is attributed to thermal heterogeneity within the reactor. The irradiated front face reaches significantly higher temperatures than the reactor core; consequently, biomass located near the irradiated surface likely underwent pyrolysis earlier than the bulk material. These effects are examined in greater detail in the following section.

3.5. Evaluation of Thermal Homogeneity: Peripheral Sensors and Reactor Heating

Figure 5 presents the temperature measurements obtained from the peripheral thermocouples (T2, T3, and T4), together with the internal bed temperature recorded by T5. These results correspond exclusively to the CaEX woody residue pyrolysis experiments conducted under Case A (CA).

In the figure, the first column displays the temperature–time profiles, while the second column shows the corresponding heating rates derived from the temperature gradients (dT/dt). The rows are organized according to the applied constant radiative power: low power (234 W), medium power (482 W), and high power (725 W). The dashed vertical lines indicate the precise moments at which the solar simulator is switched on—marking the onset of radiative heating—and subsequently switched off, signaling the beginning of the reactor cooling phase.

The primary objective of

Figure 5 is to illustrate the lack of thermal uniformity within the reactor during the heating stage, both on the external surfaces and inside the reactor bed. Notably, the rear section of the reactor (T2) consistently records the lowest temperatures across all power levels.

In contrast, the cooling phase exhibits a markedly more homogeneous thermal behavior, characterized by substantially reduced temperature gradients. During this stage, the temperatures measured by the thermocouple pairs T2–T5 and T3–T4 are nearly identical. Likewise, the corresponding heating-rate profiles display strong convergence during cooling, indicating uniform heat dissipation throughout the reactor.

The observed thermal heterogeneity during heating is of particular relevance, as it directly explains the early gas production detected in

Figure 4. Specifically, the fraction of biomass located near the irradiated front surface reached pyrolysis conditions earlier than the bulk material at the reactor center. Consequently, this effect must be carefully considered when interpreting gas evolution and reaction onset, even though the reactor dimensions are relatively small.

3.6. Interpretation of Solar Pyrolysis Stages Using the Internal Thermocouple (T5)

Figure 6 follows the same layout as

Figure 5, presenting the temperature–time curves in the first column and the corresponding heating-rate profiles (

dT/

dt) in the second column. The rows correspond, from top to bottom, to the low, medium, and high radiative power levels.

This figure exclusively displays the results obtained from the internal thermocouple T5. The notation CA refers to pyrolysis experiments conducted with reactive material (Carya illinoinensis woody residue), whereas CB denotes the heating curves of the resulting biochar. The biochar experiments serve as a reference for the heating behavior of an apparently inert material, consistent with observations from the inert-material campaigns, where no phase transitions or significant chemical reactions are expected.

The first peak observed in the Der T5–CA curves is attributed to the drying (

dy) stage of the biomass. This assignment is supported by both the timing of the peak and its occurrence within the approximate temperature range of 60–100 °C. This interpretation is consistent with literature reports indicating that biomass drying typically initiates between 40 and 70 °C [

67]. As shown in

Figure 6, the peak associated with drying occurs progressively earlier as the applied power increases: at 7.8 min for low power, 5.3 min for medium power, and 3.3 min for high power.

The shaded regions indicate the temperature interval between 200 and 400 °C, within which active pyrolysis (Ac) is assumed to occur. Although the CB experiments reached 200 °C at different times depending on the applied power, the CA experiments were consistently used as the reference for defining the onset of active pyrolysis throughout the manuscript.

In the low-power experiments, the internal temperature did not exceed 400 °C. Consequently, active pyrolysis is interpreted to extend until the end of the heating phase under these conditions. In contrast, for the medium- and high-power experiments, active pyrolysis clearly coincides with the appearance of the second peak in the Der T5–CA curves, allowing this feature to be directly associated with the active pyrolysis stage.

The convergence of the Der T5–CA and Der T5–CB curves is interpreted as marking the onset of passive pyrolysis (Pa). Based on this observation, it is inferred that some degree of overlap between active and passive pyrolysis likely occurred during the low-power experiments, as previously discussed, given that the decomposition of certain lignin components can initiate at temperatures below 200 °C.

The time required for the internal reactor temperature (T5) to enter and traverse the active pyrolysis temperature range (200–400 °C) was extracted from

Figure 6 and is summarized in

Table 2. This table constitutes a key reference for the subsequent analyses.

3.7. CaEX: Analysis of Gas Outlet (T6) and Tar Trap (T7) Temperatures

Figure 7 presents the temperature profiles recorded by thermocouples T6 and T7, which monitor the reactor gas outlet temperature and the temperature within the tar trap, respectively, during the CA (woody residue pyrolysis) and CB (biochar heating) experiments. The figure follows the same structure as previous ones: the first column displays the temperature–time curves, the second column shows the corresponding heating rates (

dT/

dt), and the rows are arranged in descending order of radiative power (low, medium, and high).

During the CB experiments, both T6 and T7 exhibit gradual heating of the carrier gas, characterized by slightly positive and smooth derivatives, with no significant fluctuations. This behavior is indicative of purely sensible heat transfer and confirms the absence of relevant chemical reactions or phase transitions during biochar heating.

In contrast, the CA experiments display pronounced peaks and fluctuations in both the T6 and T7 temperature profiles, clearly evidencing the occurrence of phase changes and chemical reactions associated with biomass pyrolysis. The first peaks observed in

Figure 7 are attributed to the drying (

dy) stage, as their timing coincides with the interval during which the internal reactor temperature (T5) lies within the 60–100 °C range.

In the low-power CA experiments, thermocouple T6 registers a relatively stable temperature plateau during the active pyrolysis stage (

Figure 7a), while the corresponding derivative approaches zero (

Figure 7b). This behavior is interpreted as the result of condensation processes involving liquid pyrolysis products formed during active pyrolysis. Similar plateaus are also observed under medium and high power conditions, although over progressively shorter durations as radiative power increases.

Thermocouple T7, located within the tar trap, exhibits a downward temperature trend following the drying stage. Additionally, distinct valleys appear after active pyrolysis, which are interpreted as indicative of tar condensation. These features are particularly pronounced in the medium- and high-power experiments (

Figure 7c,e). At later stages, the temperature curves and their derivatives tend to converge, suggesting that the net generation of condensable liquids and gases diminishes significantly as the active pyrolysis reactions become exhausted.

3.8. CaEX: Analysis of Pyrolysis Gas Composition

Figure 8 presents the temporal evolution of gas composition during the CA (woody residue pyrolysis) and CB (biochar heating) experiments. Unlike previous figures, the data are organized by experiment type: the first column displays the volumetric concentrations (% vol) of CO, CO

2, H

2, and CH

4 measured during the CA experiments, while the second column corresponds to the CB experiments. The rows are arranged according to the applied radiative power (low, medium, and high).

3.8.1. Gas Production in CA Experiments (Woody Residue)

Under low-power conditions (L) (

Figure 8a), the production of CO and CO

2 clearly dominates over that of CH

4 and H

2. Notably, gas production peaks are observed prior to the onset of the active pyrolysis temperature range. This behavior is attributed to the lack of thermal homogeneity within the reactor, as previously discussed in the analysis of peripheral sensor measurements.

A second peak in CO and CO2 production, followed by a marked depletion, can be associated with the active pyrolysis (Ac) stage. However, under low-power conditions, no significant variations are observed in the production of H2 or CH4.

These results are consistent with literature reports indicating that higher temperatures favor hydrogen formation [

68]. Moreover, several studies have shown that H

2 concentrations typically exceed those of CO

2 above approximately 400 °C. In contrast, the trends governing the relative production of CH

4 and H

2 remain less clearly defined [

69].

In the medium- (M) and high-power (H) CA experiments (

Figure 8c,e), distinct production peaks for H

2 and CH

4 are observed, occurring precisely within the time interval associated with active pyrolysis. Following this stage, a clear depletion trend is evident for all gaseous species.

Comparable behavior was reported by Zhang [

47], who observed an initial phase of intense gas production followed by progressive depletion, both strongly governed by operating temperature. This trend is also consistent with the product distribution curves reported by Aguado and Westerhof [

70,

71], which show that increasing temperature leads to higher gas yields, lower biochar yields, and liquid yields reaching a maximum at approximately 500 °C.

From the comparison of the three CA experiments, it is evident that H2 production increases systematically with both temperature and radiative power. Notably, under high-power conditions, H2 production substantially exceeds that of all other gaseous species, highlighting the strong dependence of hydrogen formation on thermal input during solar-driven biomass pyrolysis.

3.8.2. Gas Production in CB Experiments (Biochar)

The reheating of the biochar (CB) was conducted with the primary objective of establishing an instrumental reference baseline for comparison with the first heating stage (CA experiments). This experimental design was based on the hypothesis that, provided the maximum temperature reached during the initial pyrolysis was not exceeded, subsequent chemical reactions would be minimal or negligible, causing the biochar to behave as an apparently inert material.

The volumetric concentrations of gases produced during the reheating of biochar, shown in the second column of

Figure 8, support this hypothesis. Under comparable temperature and radiative power conditions, gas production during the CaEX biochar heating experiments (CB) was observed to be up to 25 times lower than that recorded during the corresponding CA experiments. Moreover, no significant production peaks were detected for any of the monitored gaseous species (H

2, CO, CO

2, and CH

4) within the temperature range associated with active pyrolysis.

Although a minor residual gas production was detected during the CB experiments, it accounted, on average, for only 0.4% of the total initial feed mass. These results, together with comparisons against the empty-reactor and volcanic-stone heating experiments, provide strong evidence supporting the assumption that biochar behaves as an apparently inert material during reheating under the conditions explored in this study.

This behavior closely resembles that reported in the literature for inertinite, one of the primary macerals in coal, alongside vitrinite and liptinite. Inertinite originates from organic matter that underwent extensive degradation, oxidation, or partial combustion prior to geological burial, resulting in a highly aromatized, carbon-rich, and structurally dense material with low volatile content. As reported in the literature [

72,

73,

74], inertinite exhibits the following thermal characteristics during heating: (1)very limited thermal reactivity compared to other macerals; (2) release of only small amounts of volatile matter; (3) low thermoplasticity, with negligible participation in softening or coke formation; and (4) decomposition restricted to higher temperatures than those associated with vitrinite or liptinite.

In summary, inertinite represents a highly thermally mature coal component with very low reactivity, remaining largely unaltered under moderate to high heating conditions, although it is not strictly inert. In the context of the present work, a closely analogous behavior was observed during the reheating of the biochars produced in both the CaEX and WSSP experiments.

3.9. Comparative Analysis Between CaEX (Pecan Pruning) and WSSP (Walnut Shell) Experiments at 234, 482, and 725 W

The analytical methodology applied to the CaEX woody residue experiments—based on temperature profiles, their derivatives, and the identification of active pyrolysis intervals—proved effective in distinguishing the main process stages, namely drying, active pyrolysis, and passive pyrolysis.

However, when these results are compared with those obtained from the walnut shell experiments (WSSP), it becomes evident that the thermal and derivative signals associated with WSSP are significantly more pronounced. Across all radiative power levels, the WSSP experiments exhibited clearer and sharper features, including the following:

Distinct phase changes associated with moisture evaporation.

Transient temperature spikes indicative of potentially exothermic behavior.

Signs consistent with the formation of heavy tar compounds.

More clearly defined gas evolution patterns.

The primary factor responsible for these differences is the disparity in bulk density between the CaEX and WSSP feedstocks, which directly affects the amount of biomass that can be loaded into the reactor, as summarized in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, the bulk density of the pruning material (CaEX, 0.232 g/cm

3) is substantially lower than that of the walnut shell (WSSP, 0.504 g/cm

3), indicating that the walnut shell feedstock is approximately 2.17 times denser. Given that the reactor volume was limited to 115 cm

3, the mass of CaEX loaded into the reactor (approximately 25.5 g) was therefore roughly half that of WSSP (approximately 50 g), in direct agreement with the density ratio.

The lower biomass mass present in the CaEX bed reduced the magnitude of thermal variations, including both endothermic effects associated with moisture evaporation and potentially exothermic phenomena linked to pyrolysis runaway. In addition, the reduced mass limited the total production of gaseous and condensable products. As a result, the CaEX experiments displayed weaker and less sharply defined thermal and compositional signals compared to those observed for WSSP.

Despite these differences in signal intensity, both feedstocks exhibited comparable qualitative thermal behavior. In particular, the reheating experiments confirmed the apparently inert character of the resulting biochars, regardless of the original biomass type, reinforcing the validity of the comparative framework adopted in this study.

3.10. Evaluation of Yields: Solar Reactor vs. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

To quantify the discrepancy between the pyrolysis yields obtained in the solar reactor and those derived from Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), a comparison of the biochar fraction was performed. The biochar yields obtained in the solar batch reactor were contrasted with the residual mass fractions determined by TGA, using as a reference the maximum internal temperatures (T5, max) reached during the solar simulator experiments. Two basic quantitative error estimation methods were applied to assess the differences.

The first level of

Table 4 presents the final product balance, including biochar, gas, and liquid fractions. To perform this mass balance, the reactor was first allowed to cool, after which the solid products were removed and weighed. The amount of gas produced was calculated by integrating the area under the gas-production curves obtained from the measured data points. Most of the liquid fraction was recovered in the tar trap; however, a portion remained in the condensers and downstream cotton filters (

Figure 1). Consequently, the liquid yield was estimated by difference, subtracting the masses of char and gas from the initial feed mass.

This first level of

Table 4 also reports the mass balance results as a function of radiative power and maximum internal reactor temperature (T5, max). The data show that the biochar yield decreases inversely with increasing maximum temperature, whereas both gas and liquid yields increase at higher temperatures.

The second level of

Table 4 presents a comparison between the biochar yields obtained in the solar reactor and those from a first thermogravimetric analysis (TGA1). The second column of this level corresponds to the reference temperatures, followed by the mass percentages obtained from TGA1.

Two methods were used for the quantitative evaluation of the differences. The first method is defined as the absolute difference (

Ev1):

where

is the mass percentage from TGAi, and

is the mass percentage of biochar obtained with the solar reactor. The second method is a relative percentage error (

Ev2), defined as follows:

The third level of

Table 4 presents the evaluation of these errors using a second thermogravimetric analysis (TGA2). Using the

Ev1 criterion, an average absolute difference of 4.66% was obtained, indicating a close agreement between the biochar yields measured in the solar reactor and those derived from TGA. In contrast, the

Ev2 method yielded an average relative error of 15.20%. This result is noteworthy, since applying the same

Ev2 criterion to previous walnut shell (WSSP) experiments resulted in a relative error of only 1.5%.

This larger relative error is attributed to the low bulk density of the pecan woody residue. A less dense material bed is expected to exhibit poorer thermal contact between the biomass and the internal thermocouple, affecting the accuracy of the recorded maximum temperature (T5, max) and, consequently, the correlation with the TGA results.

Figure 9 presents the

Ev1 evaluation (absolute difference), illustrating the divergence between the biochar yields obtained in the solar reactor and those measured by TGA. The solar reactor yields closely follow the trend of the TGA curves, showing only minor deviations.

A consistent observation is that the biochar yields obtained in the solar reactor during CaEX experiments lie below the corresponding TGA curves. This suggests that the biochar was likely exposed to temperatures higher than those recorded by the internal instrumentation, leading to increased conversion and, consequently, lower residual mass compared with the TGA results.

This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the limited thermal contact between the internal thermocouple and the wood-pruning sample, an effect associated with the low bulk density of the material. In contrast, materials with higher density and greater contact surface area provide more reliable temperature measurements. In this sense, the pecan woody residue behaves as a highly porous medium when compared with walnut shell samples.

3.11. Elemental Analysis and Higher Heating Value (HHV)

Table 5 presents the comparative elemental analysis of the feedstock (

Carya illinoinensis woody residues) and the biochar produced at different radiative power levels.

An increase in the carbon (C) content is observed as a function of radiative power and, consequently, of the maximum reaction temperature reached. Conversely, the elemental fractions of hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) decrease progressively with increasing temperature. The nitrogen (N) content remains nearly constant throughout all experiments.

Table 5 also shows that the pyrolysis process significantly enhances the energy density of the biomass, as reflected by the increase in the Higher Heating Value (HHV). However, a slight decrease in HHV is observed for the biochar obtained at high power (H = 725 W) when compared with that produced at medium power (M = 482 W).

Additionally, the elemental composition and heating values of both the

Carya illinoinensis wood and the resulting biochars are consistent with values reported in the literature for woody and agricultural biomasses. In general terms, these properties increase as a function of the degree of carbonization [

75,

76,

77,

78]. A similar trend was reported by Qian et al. [

79], who observed that the HHV of biochar increases with temperature but decreases when temperatures approach or exceed approximately 750 °C.

3.12. Bulk Density and Temperature

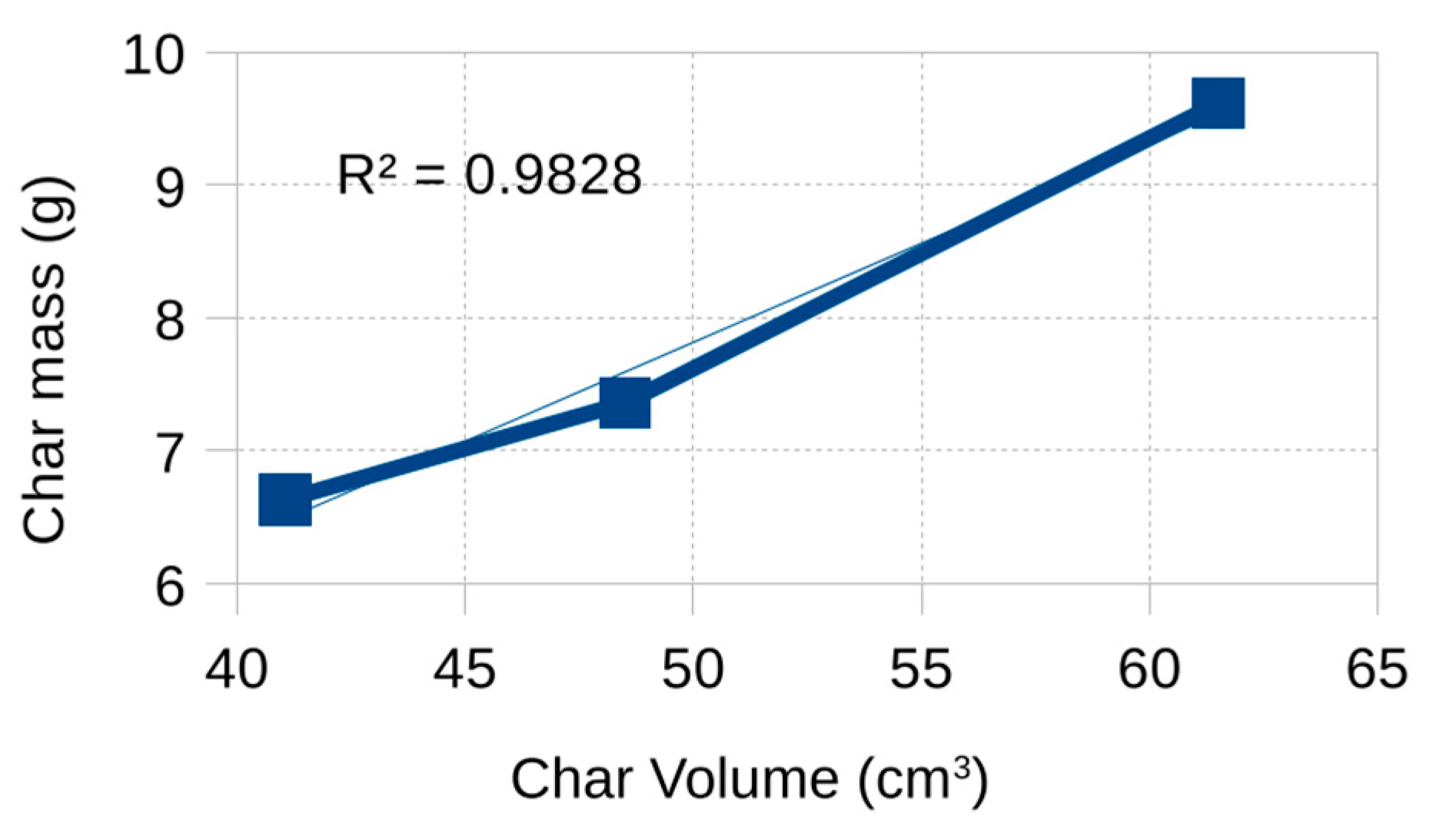

Table 6 presents the mass, apparent volume, and bulk density of the feedstock and the resulting biochars as a function of radiative power and maximum reaction temperature for the CaEX pyrolysis experiments.

A systematic decrease in both the mass and apparent volume of the biochar is observed as temperature and radiative power increase. However, an inconsistency is detected in the bulk density results: a decrease is observed at medium power (M = 482 W), which disrupts the expected monotonic trend.

This behavior contrasts with previous reports in the literature, which generally indicate that the bulk density of biomass-derived chars increases with reaction temperature during pyrolysis, without exhibiting inflection points, unlike the behavior commonly observed for heating value [

80,

81,

82].

To explore a possible explanation for the observed inconsistency in bulk density,

Figure 10 presents the correlation between the mass and volume reductions of the biochar. A nearly linear relationship is observed (R2 = 0.983). Furthermore, the hypothetical measurement error required for the bulk density to follow a strictly increasing trend was estimated. The analysis indicates that an error on the order of 4.5% in either mass or volume measurements would be sufficient, a value that is considered reasonable within the limits of experimental uncertainty.

Despite this inconsistency, the overall experimental trends remain coherent and fall within the ranges reported in the literature.

One of the most relevant findings of the present work is that the relatively low mass of material loaded into the reactor significantly affected the internal temperature signal (T5), as well as the temperature measurements at the gas outlet (T6) and tar trap (T7), in contrast with the behavior observed in the nut shell experiments (WSSP).

Accordingly, the results indicate that the intrinsically low bulk density of pecan pruning (Carya illinoinensis, CaEX) plays a critical role. This characteristic likely leads to an underestimation of the temperature recorded by the thermocouple in contact with the biomass (T5). A less dense material contains a higher fraction of voids, which facilitates carrier-gas flow and enhances convective effects that perturb the thermal measurement. In addition, lower density implies reduced mechanical contact pressure between the biomass and the sensor, limiting effective conductive heat transfer.

This interpretation provides supporting evidence for the downward shift observed in the biochar yield curves (

Ev2) relative to the TGA results shown in

Figure 9. Notably, this effect was not observed in the walnut shell experiments (WSSP), which involved a substantially higher bulk density material.

Based on these findings, it is recommended that future studies include parametric analyses involving different carrier-gas flow rates and particle sizes, in order to more accurately evaluate the interplay between convective and conductive effects in temperature measurements within solar pyrolysis reactors.

4. Conclusions

This study reports the experimental investigation of the solar pyrolysis of woody residues derived from the pruning of Carya illinoinensis, using a solar simulator as the heat source. The primary objective was to instrument the reactor and analyze the resulting thermal and compositional data in order to identify distinct stages of biomass pyrolysis: drying (dy), active pyrolysis (Ac), and passive pyrolysis (Pa).

To this end, the reactor was equipped with multiple temperature sensors and an online gas-analysis system, and an improved data analysis methodology based on heating-rate derivatives (dT/dt) was applied to highlight thermal variations and facilitate the identification of process stages. The experimental campaign was structured into Case A (CA), corresponding to biomass pyrolysis, and Case B (CB), consisting of the reheating of the produced biochar, which served as an apparently inert reference.

The results enabled the identification of the characteristic pyrolysis stages of the woody residues. However, the associated thermal and compositional signals were significantly less pronounced than those observed in previous experiments conducted with walnut shells (WSSP). This difference is primarily attributed to the substantially lower bulk density of the Carya illinoinensis pruning material—approximately 2.5 times lower than that of walnut shells—which limited the mass loaded into the reactor and resulted in weaker thermal responses and reduced gas evolution.

The combined analysis of temperature measurements and gas composition provided information that supports the interpretation of biochar as an apparently inert material when reheated under the same conditions in which it was produced, consistent with earlier observations for WSSP-derived biochar. In addition, the results suggest that the pyrolysis of woody pruning residues generates smaller quantities of heavy tars than walnut shells, indicating the need for further experiments to quantify condensable products in greater detail.

Finally, the low bulk density of the pruning material, and the resulting attenuation of thermal signals, is attributed to two main effects that affect the internal temperature measurement (T5): (i) enhanced convective effects due to the larger void fraction, which facilitates the flow of the inert carrier gas, and (ii) reduced conductive contact, as the lower mass exerts less pressure on the thermocouple. This interpretation provides a plausible explanation for the divergence observed between biochar yields obtained in the solar reactor and those derived from TGA. Accordingly, future work should include parametric studies involving different carrier-gas flow rates and particle size distributions to better assess the interaction between convective and conductive mechanisms influencing temperature measurements.