Abstract

This study examines the effect of air-entraining agents (AEAs) type on cement-mortar air content and air-void structure under reduced atmospheric pressure. Six representative AEAs—cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), triterpenoid saponin (TS), sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS), sodium abietate (SA), cocamidopropyl betaine (CAB), and fatty alcohol polyoxyethylene ether (AEO-9)—were selected. Their foaming ability and time-dependent foam stability were measured in deionized water and in cement filtrate, and the air content of fresh mortars and the distribution of air-voids in hardened mortars were determined at 100 and 60 kPa. The results show that, at 100 kPa, TS, CAB, and CTAB produced higher initial foam height and better foam stability in deionized water than AEO-9, SA, and SDBS. TS and CAB also maintained a higher number density of bubbles and slower coalescence. In addition, all surfactant systems showed lower initial foam height and stability in cement filtrate than in deionized water, with SDBS, SA, and AEO-9 experiencing the greatest declines. When the pressure decreased from 100 kPa to 60 kPa, the mortar air content dropped by 8–15%, with the smallest reduction for TS (~8%) and the largest for CTAB (~15%). At 60 kPa, air voids with radius < 250 μm decreased markedly in hardened mortars: by 51%, 25%, and 28% for the control, CTAB, and AEO-9 mortars, respectively; but only by 14% for TS, highlighting its superior retention of fine air voids. Overall, amphoteric/saponin-type systems (represented by TS) exhibit better tolerance and stabilization, and are recommended for high-altitude concrete.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of China’s Western Development Strategy and new urbanization, an increasing number of residents are living in plateau areas [1,2]. Consequently, the improvement of road and municipal infrastructure construction in these regions is particularly important [3]. The plateau environment, typically characterized by reduced atmospheric pressures of about 60–70 kPa at elevations of 3000–4000 m, high annual solar radiation on the order of 6000–8000 MJ/m2, large diurnal air-temperature ranges often exceeding 20 °C, and more than 100 natural freeze–thaw cycles per year in many areas, poses more severe challenges to the service durability of concrete materials [4,5,6]. Existing engineering and experimental studies indicate that reduced air content and deteriorated air-void structure—fewer small pores, a higher spacing factor, and more connected bubbles—are key contributors to the loss of frost resistance in plateau concrete [7,8]. Thus, reliably introducing and retaining uniform, fine air bubbles in concrete is key to enhancing frost and salt-scaling resistance in plateau regions.

Air-entraining agents (AEAs) promote bubble nucleation and stabilize foam films via interfacial activity during mixing, thereby increasing bubble number density and refining the pore-size distribution [9]. However, existing research points out that the air-entraining efficiency and foam stability of most conventional AEAs decrease significantly in low-pressure environments. Li Xuefeng et al. [10,11] systematically compared four common types of AEAs in air-entrained concrete mixed inside a low-pressure chamber, where the ambient pressure was reduced from standard atmospheric pressure to about 50 kPa. They reported that the air content of fresh concrete decreases approximately linearly with decreasing environmental pressure, and that the reduction in air content can reach 20–49% at around 50 kPa, with the degree of sensitivity strongly dependent on the AEA type. Chen et al. [12] performed an on-site experimental campaign at different elevations, preparing cement paste, mortar, and concrete in Shigatse (3860 m, ~64 kPa), Lhasa (3646 m, ~66 kPa), and Harbin (150 m, ~101 kPa) under rigorously controlled mix proportions and raw materials. Their results showed that, for mortars with SJ-2 or 303R AEAs, the air-entraining efficiency and air-bubble stability were only weakly affected by atmospheric pressure changes, and that the air-void characteristics of hardened mortars remained similar at low and standard pressures; they also highlighted that the temperature and quality of raw materials can significantly interfere with the apparent pressure effect. Li Yang [13] carried out pressure-controlled foaming tests on five commercial AEAs in solution, demonstrating that the initial foam height decreases with decreasing pressure and that foam stability exhibits marked “product-dependent” characteristics. Liu Xu et al. [14,15] further pointed out that such solution foaming tests do not fully represent the effectiveness of air-entraining in cement-based systems, and emphasized the need for systematic evaluations under coupled “cement filtrate/mortar–low-pressure” conditions so as not to overemphasize interfacial activity while neglecting ionic strength and solid–liquid interface effects. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the sensitivity of different types of AEAs to changes in atmospheric pressure and to identify AEAs suitable for the low-pressure environment of plateau regions.

In this context, the present study systematically investigates the shaking-foaming performance of six representative AEAs (cationic, anionic, nonionic, amphoteric, and saponin-based), the time-dependent evolution of foam height and bubble size, and their effects on air content and air-void structure of mortars under both normal and reduced atmospheric pressures. Unlike earlier low-pressure AEA studies that typically examined one or two admixture types or relied mainly on solution foaming tests, this work combines aqueous solution and cement filtrate measurements with mortar-scale air-void characterization in a unified low-pressure chamber. By quantitatively linking bubble evolution in AEA solutions to the air content and fine-void retention in hardened mortars, the study reveals the superior pressure tolerance of saponin-based TS and provides a mechanistic basis for selecting AEAs suitable for plateau concrete.

2. Raw Materials and Test Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

P·I.42.5 Portland cement conforming to the Chinese National Standard “Common Portland Cement” GB 175-2023 [16] was used to prepare the cement filtrate and cement mortar. Its mineral composition and physical properties are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. ISO standard sand produced by Xiamen ISO Standard Sand Co., Ltd. was used as the fine aggregate for fabricating the cement mortar specimens, with a fineness modulus of 2.8 and an apparent density of 2.63 g/cm3 [17]. A high-performance superplasticizer (Sika 530P) produced by Sika (Jiangsu) Construction Materials Co., Ltd., Changshu, China was employed as the water-reducing agent. Deionized water was used for the solution foaming performance tests, and tap water was used for mortar specimen preparation. The cement filtrate was prepared using a paste with a water–cement ratio of 2 [18].

Table 1.

Mineral composition of P.I 42.5 Portland cement (wt.%).

Table 2.

Physical performance of P.I 42.5 Portland cement.

Six types of AEAs were used in this study, and their classifications and physical states are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Information on the AEAs used in this study.

2.2. Test Methods

All low-pressure environment tests related to this study were conducted inside a multi-parameter coupled environmental test system (TLPS4012-S, Hardy Technology International Ltd. (Chongqing, China)). The internal dimensions of the environmental simulation system are 3 m × 2 m × 2.2 m, capable of simulating an atmospheric pressure range from atmospheric pressure to 30 kPa, a temperature range from −40 °C to 150 °C, and a relative humidity range from 20% RH to 98% RH.

2.2.1. Measurement of Foam Height of AEA Solutions and Analysis of Foam Morphology Changes

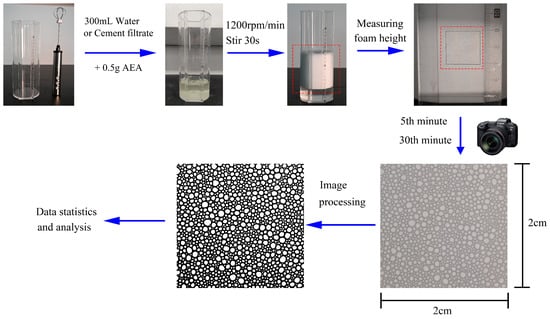

The foaming performance of air-entraining agent (AEA) solutions can reflect their air-entraining performance in concrete [19]. This study designed a dedicated foaming device (a cylinder with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 25 cm, featuring a 4 cm wide foam morphology observation window on the sidewall). Bubble morphology was observed within a 2 cm × 2 cm square area located 7 cm from the bottom. During the test, 300 mL of water or cement filtrate and 0.5 g of AEA were added to the container at 20 °C. After shaking gently to dissolve the AEA, the solution was stirred using a stirrer at 1200 rpm for 30 s. The foam height (difference between the top and bottom surfaces) was subsequently measured. Images of the observation area were captured at 5 min and 30 min after the cessation of stirring for analyzing the bubble structure and foam stability. Each experiment was repeated three times. The operational process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Foaming tests of air-entraining agent solutions and foam stability analysis.

2.2.2. Mortar Mix Proportions and Casting Method

The cement mortar specimens were prepared in accordance with Method T 0587 of the Chinese standard Testing Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering (JTG 3420). The air-entraining agent was first dissolved in the mixing water and then introduced into the mortar together with the mixing water [20]. The mix proportions of the mortar used in this study are shown in Table 4. Four types of AEAs were used in the tests. The dosage of the AEAs for each group of mortar was determined by controlling the initial air content of the mortar within the range of 11% ± 1% at 100 kPa. The dosage of AEAs was added relative to the mass of cement.

Table 4.

Mixture proportions of cement mortar.

2.2.3. Test for Air Content of Fresh Cement Mortar

The air content test for fresh mortar was conducted according to Method T0590-2020 specified in the “Test Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering” (JTG 3420-2020) [21]. A 1 L volumetric cylinder (with an inner diameter of 108 mm and a height of 109 mm) was used for the test. The mass of the empty cylinder m1 was first weighed. The cylinder was then filled slightly overfull with the mixed mortar, placed on a jolting table, and compacted with 120 jolts. The excess mortar at the top of the cylinder was struck off, and the wall of the cylinder was wiped clean. The total mass m2 was then weighed. The bulk density of the mortar was calculated using Equation (1), and the theoretical density of the mortar was calculated using Equation (2). The results were recorded with an accuracy of 10 kg/m3.

where —Bulk density of mortar (g/cm3); —Mass of the container (g); —Mass of the container and mortar (g).

where —Theoretical density of mortar (g/cm3); —Density of raw materials (g/cm3).

The air content by volume of mortar is calculated using Equation (3).

where —Air content by volume of mortar.

2.2.4. Test for Air-Void Structure of Hardened Mortar

The air-void structure of the mortar was tested using a hardened concrete air-void analyzer (Rapid Air 457, Concrete Experts International, Vedbæk, Denmark). Mortar specimens of 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm were prepared, cured under standard conditions for 28 days, and then cut into 10 cm × 10 cm × 2 cm thin slices. The test surface was ground with sandpaper until it was flat and smooth, followed by ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min and drying in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min before cooling to room temperature. The surface was painted black with ink, and then the surface pores were filled with a white paste prepared by mixing nano-zinc oxide and glycerol. The excess paste was scraped off, and the air-void structure test was subsequently conducted. Three specimens were tested per group, and the average value was taken as the result. The testing process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Air-void structure test of hardened mortar.

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Initial Foam Height and Time-Dependent Variation in Foam Height

3.1.1. Initial Foam Volume

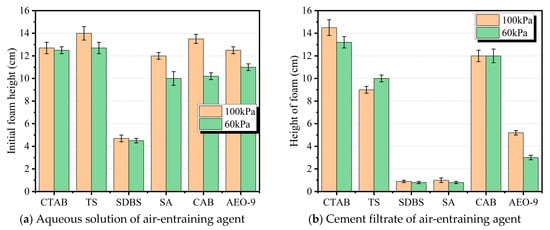

The foam content of an air-entraining agent (AEA) solution after rapid stirring can, to a certain extent, reflect its air-entraining capacity in concrete [17]. This study investigated the foaming capacity of AEAs in both aqueous solution and cement filtrate under atmospheric pressures of 100 kPa and 60 kPa, respectively. The test results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Initial foam height in AEA aqueous solutions and cement filtrate measured immediately after mixing.

As shown in Figure 3a, when the atmospheric pressure decreases, the foaming capacity of different types of AEAs in aqueous solution follows a consistent pattern: the foam volume decreases with reduced atmospheric pressure. This indicates that a decrease in atmospheric pressure reduces the air-entraining capacity of AEA aqueous solutions. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the foaming capacity of SDBS in aqueous solution is significantly weaker than the other five AEAs. The reason may lie in the slower diffusion and adsorption rate of SDBS monomers to the nascent gas–liquid interface during the foaming/shearing moment compared to the other AEAs, resulting in persistently high dynamic surface tension and difficulty in rapidly generating and retaining sufficient fine bubbles [22,23].

As shown in Figure 3b, the foaming capacity of AEAs in cement filtrate is significantly different from that in aqueous solution. The air-entraining capacity of SDBS, SA, and AEO-9 is most significantly affected in cement filtrate. The pH of cement filtrate typically ranges between 12 and 13, and it contains a high concentration of ions such as Ca2+, SO42−, OH−, etc. [24]. These ions may interact with AEA molecules, affecting their air-entraining effectiveness. For SDBS and SA AEAs, in cement filtrate with a pH of 12–13 and containing Ca2+, the anions associate/precipitate with Ca2+ (e.g., forming (SDBS)2Ca, Ca-soap), reducing the number of effective monomers and micelles in the aqueous phase [25]. Additionally, if these precipitates occur on the bubble film, they increase the brittleness of the bubble membrane, making the bubbles more prone to rupture under disturbance [26]. AEO-9 experiences a significant decrease in cloud point and undergoes dehydration/salting out of EO chain segments in the strong electrolyte and high alkali environment, leading to reduced solubility and interfacial activity, and increased dynamic surface tension [27]. Furthermore, some competitive adsorption and entrainment loss by hydration products and unreacted particles ultimately result in a significant decline in its foaming capacity.

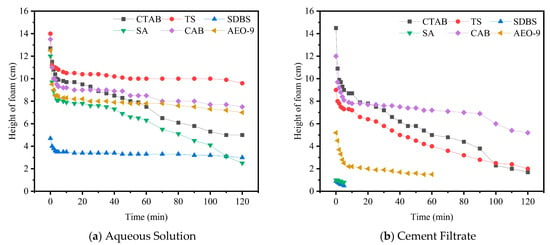

3.1.2. Time-Dependent Variation in Foam Height in Aqueous Solution and Cement Filtrate

After mixing is completed and before initial setting, concrete remains in a plastic state with fluidity. The bubbles introduced by the air-entraining agent within it undergo continuous evolution. The stability of the foam during this period also has a significant impact on the pore structure of the hardened concrete. Therefore, the stability of the foam in the AEA solution also serves as a crucial basis for evaluating the air-entraining performance of the agent. The time-dependent variation in foam height in AEA solutions was tested (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Foam height vs. time at 100 kPa (AEAs in aqueous Solution and cement filtrate).

As shown in Figure 4, it is generally observed that at 100 kPa, the foam height in cement filtrate for all types of AEAs decays significantly faster over time compared to in deionized water. This phenomenon results from the coupling of multiple mechanisms. The high pH and strong electrolyte environment accelerate film drainage, reduce interfacial viscoelasticity and Marangoni restoration, and alter surfactant adsorption–desorption kinetics, so that the dynamic surface tension remains above its equilibrium value for extended periods [28]. Specifically, SDBS and SA (anionic types) undergo association/precipitation (e.g., forming (SDBS)2Ca or Ca-soap) in the presence of Ca2+, significantly reducing the number of effective monomers and micelles in the aqueous phase. If these precipitates or aggregates nucleate on the bubble film, they can cause film embrittlement and create defect sites, promoting coalescence and bubble rupture. The nonionic type (AEO-9), due to the strong electrolytes, experiences a lowered cloud point and dehydration/salting out of the EO chains, leading to weakened interfacial activity and film viscoelasticity, also manifesting as poor foam stability. Additionally, surfactant adsorption by hydration products and unreacted particles further reduces free monomer concentration. The superposition of the aforementioned factors leads to the faster decay of foam in cement filtrate and the observed differences among the different AEA types.

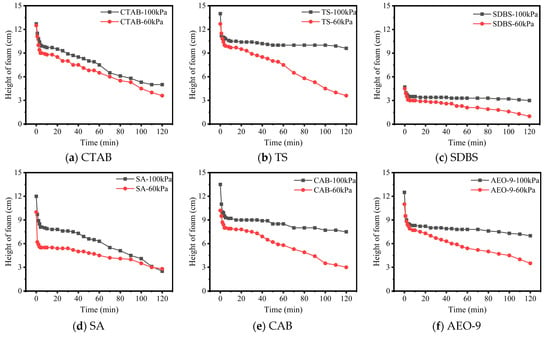

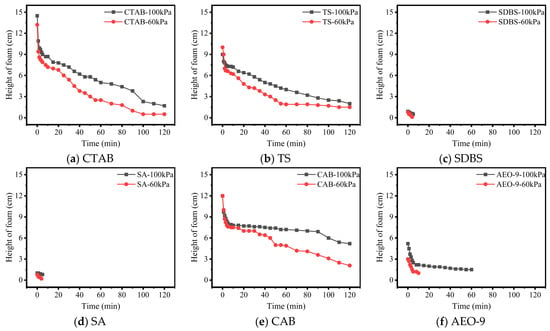

3.1.3. Effect of Atmospheric Pressure on the Variation in Foam Height in AEA Solutions

This study investigated the decay patterns, over a period of 2 h, of foam formed by air-entraining agent (AEA) aqueous solutions and cement filtrate under two different atmospheric pressures. The results are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Foam height vs. time in aqueous solution under different pressures.

Figure 6.

Foam height vs. time in cement filtrate under different pressures.

From Figure 5 and Figure 6, it can be observed that atmospheric pressure significantly influences the stability of foam formed by AEA solutions. Generally speaking, whether in aqueous solution or cement filtrate, the foam decays faster at 60 kPa compared to 100 kPa. There are two potential reasons for this: firstly, in a low-pressure environment, the surface tension at the gas–liquid interface is higher [29]. According to the Young–Laplace equation, increased surface tension raises the additional pressure exerted on the bubble by the bubble wall, which accelerates the diffusion of gas from small bubbles into larger ones. This causes the large bubbles to grow, while the water in the walls of these large bubbles is not replenished, leading to gradual thinning and eventual rupture and collapse of the bubble walls. Secondly, low-pressure conditions accelerate the evaporation rate of water from the bubble walls, hastening water loss and thereby increasing the bubble rupture rate.

Furthermore, the decay rate of foam under different pressures also depends on the type of AEA. CTAB, TS, and CAB exhibited relatively better stability in the low-pressure environment. The reason for CTAB’s performance is its molecular flexibility, allowing dense packing at the bubble interface. Its long-chain alkyl hydrophobic groups entangle with each other, significantly enhancing the flexibility and stability of the bubble wall. For TS, its hydrophilic group is a polyhydroxy sugar chain. The increased number of hydroxyl groups strengthens its binding with polar water molecules. Additionally, its hydrophobic group consists of a triterpenoid skeleton unit comprising 30 carbon atoms. The strong spatial extensibility of this triterpenoid skeleton increases the thickness of the bubble wall to some extent, hindering the permeation of air molecules through the bubble wall, thereby enhancing bubble stability. The reason for the good stability of CAB solution bubbles under low pressure is similar to that of CTAB. The hydrophobic carbon chain (cocamide group) and hydrophilic head group (betaine) of CAB form a tight interfacial arrangement, imparting a high surface viscoelastic modulus (Gibbs elasticity) to the liquid film. When the bubble is disturbed, CAB molecules rapidly rearrange to maintain interfacial coverage, avoiding local surface tension gradients that could cause film rupture (inhibiting the Marangoni effect). During bubble contraction, the hydrophobic interactions between molecules strengthen, forming a gel-like network structure that prevents excessive drainage of the liquid film.

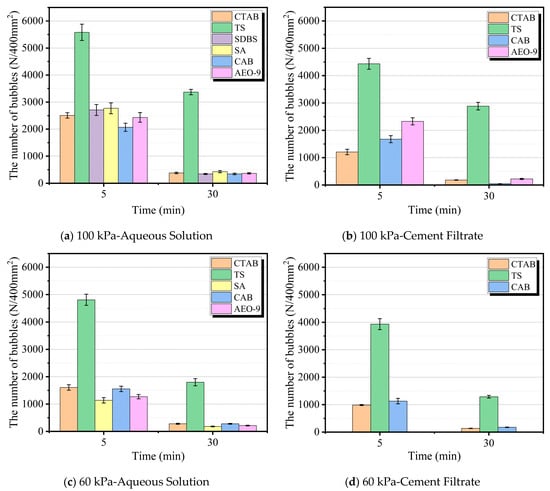

3.2. Evolution Patterns of Bubbles in Aqueous Solutions and Cement Filtrate Under Different Pressures

While recording the variation in foam height over time, this study observed that the bubbles within the foam underwent continuous evolution, even when the overall foam height did not change significantly. Therefore, relying solely on foam height to evaluate the performance of AEAs is relatively crude. Analyzing the changes in the internal bubble structure of the foam is more meaningful for studying the evolution of bubbles within concrete under low pressure. In this study, images of the bubble morphology within the foam were captured at the 5 min and 30 min marks, and software was used to count the number of bubbles within the study area. The results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Bubble number density vs. time under different pressures.

As shown in Figure 7, under the same atmospheric pressure conditions, the number of bubbles formed by the air-entraining agent in the aqueous solution after stirring is greater than that formed in the cement filtrate. This is because the cement filtrate contains a large number of ions such as Ca2+, Na+, OH−, and SO42−, etc. These ions interact with the AEA molecules, consuming them and reducing the activity of the AEA. This effect is most pronounced for SDBS and SA AEAs. Additionally, these ions cause a slight increase in the surface tension of the solution, which is unfavorable for bubble nucleation during stirring. Furthermore, the figure also shows that atmospheric pressure significantly affects bubble formation and stability. Taking the TS AEA as an example, when the atmospheric pressure decreased from 100 kPa to 60 kPa, the initial bubble density formed in its aqueous solution and cement filtrate decreased by 13.78% and 11.26%, respectively. This may be related to the increased surface tension of the solution and the increased diffusion rate of air molecules in the low-pressure environment. Moreover, it is evident from Figure 7 that the TS AEA exhibited excellent bubble performance and foam stability under different solution types and atmospheric pressure conditions. The bubble density in the foam formed by the TS AEA solution is approximately twice that of the other five AEAs.

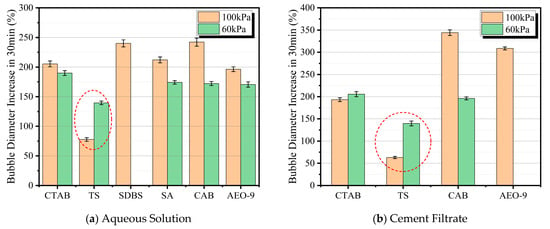

To analyze the effect of atmospheric pressure on bubble structure evolution in more detail, the number of bubbles in the observation area and the surface area occupied by the bubbles were counted. Bubbles were approximated as circles, and their equivalent circular diameter was calculated. The change in bubble diameter over 30 min was statistically analyzed, and the results are plotted in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Increase extent in bubble diameter over 30 min in aqueous solution and cement filtrate at different pressures.

Figure 9.

Increase in bubble diameter over 30 min in air-entraining agent solutions under different conditions.

Figure 8a shows the increase in the average bubble diameter of foam formed by aqueous solutions of AEAs after 30 min under different atmospheric pressures. It can be observed from the figure that, whether under normal pressure or low-pressure conditions, the foam generated by the TS air-entraining agent solution exhibits the smallest increase in average bubble diameter. Additionally, it should be noted that, except for the TS air-entraining agent, the increase in average bubble diameter of foams formed by other air-entraining agent solutions at 60 kPa is smaller than that under normal pressure conditions. This appears contradictory to the previously mentioned fact that gas molecules diffuse faster in low-pressure environments. The reason lies in the larger initial bubble diameter formed at 5 min under low pressure. A larger initial diameter results in a relatively smaller growth rate. Therefore, by comparison, the increase in average bubble diameter is smaller in low-pressure environments. In contrast, the TS air-entraining agent solution shows a greater increase in average bubble diameter at 60 kPa compared to normal pressure, because the bubbles generated by its solution at 5 min remain very fine and dense.

Figure 8b illustrates the increase in average bubble diameter of foams formed by different AEAs in cement filtrate after 30 min under different atmospheric pressures. Due to the poor foaming capacity of STBS and CA AEAs in cement filtrate, changes in bubbles formed by these two agents were not recorded. As can be seen from the figure, the foam generated by the TS air-entraining agent in cement filtrate still shows the smallest increase in average bubble diameter. Meanwhile, AEO-9 is the most affected by atmospheric pressure: under the 60 kPa condition, its cement filtrate produces only a small number of bubbles, insufficient to record the variation in bubble diameter.

Figure 9 presents the variation in bubble diameter after 30 min for foams generated by different types of air-entraining agent solutions under various atmospheric pressures. It can be observed from the figure that, under the same atmospheric pressure, the increase in bubble diameter is more pronounced in cement filtrate compared to aqueous solutions. For the same type of solution, the bubble diameter grows more rapidly in a 60 kPa environment than in a 100 kPa environment. This indicates that a reduction in atmospheric pressure accelerates the coarsening process of bubbles within the foam, which is detrimental to bubble stability. Furthermore, the figure demonstrates that the bubbles formed by the TS air-entraining agent solution exhibit superior bubble stability compared to those generated by the other tested agents.

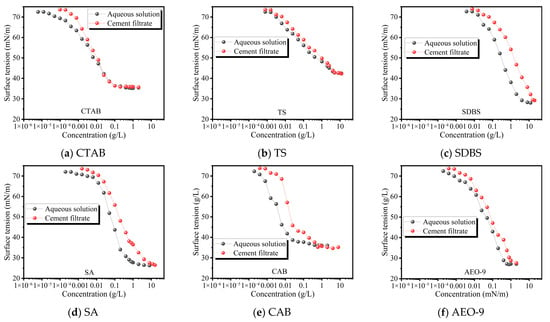

3.3. The Surface Tension of Different AEA Solutions

Figure 10 shows the variation in surface tension with concentration for the AEAs in aqueous solution and in cement filtrate. It can be seen that, at the same AEA concentration, the surface tension in aqueous solution is lower than that in cement filtrate, and that the critical micelle concentration is reached earlier in the aqueous solutions as the AEA concentration increases. This behavior is attributed to the presence of abundant Ca2+, SO42−, OH− and other ions in the cement filtrate, which can react with the AEA and consume part of the surfactant molecules. In addition, fine solid particles suspended in the cement filtrate can adsorb a portion of the AEA molecules. As a result, at a given nominal AEA concentration, the effective concentration of free AEA at the interface is lower in the cement filtrate than in the aqueous solution, leading to a higher measured surface tension.

Figure 10.

Surface tension of different AEAs in aqueous solution and cement filtrate.

Furthermore, Figure 10 shows that SDBS and SA are the most strongly affected by the cement filtrate. This is because both SA and SDBS are anionic surfactants that readily react with cations such as Ca2+ in the cement filtrate to form insoluble salts (e.g., calcium or magnesium soaps), leading to molecular deactivation. Their relatively simple molecular structures also facilitate adsorption onto cement particles. In addition, SA may undergo hydrolysis or structural changes in the highly alkaline environment, resulting in a further loss of air-entraining efficiency. By contrast, CTAB is a cationic surfactant whose quaternary ammonium headgroup carries a positive charge and is less prone to adverse reactions with cations in the cement filtrate, thereby exhibiting higher chemical stability. TS is a nonionic surfactant whose molecules are uncharged and act mainly through hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions, making them less sensitive to ionic disturbances in the cement filtrate. Moreover, both CTAB and TS can maintain favorable intermolecular interactions in cement filtrate; in particular, the structurally complex TS, which contains multiple hydroxyl and hydrophobic groups, can form a stable adsorbed layer at the air–liquid interface. As a result, they are less influenced by the ions present in the cement filtrate.

3.4. Evolution of Air-Void Structure in Cement Mortar Under Low Pressure

3.4.1. Initial Air Content of Fresh Mortar Under Different Pressures

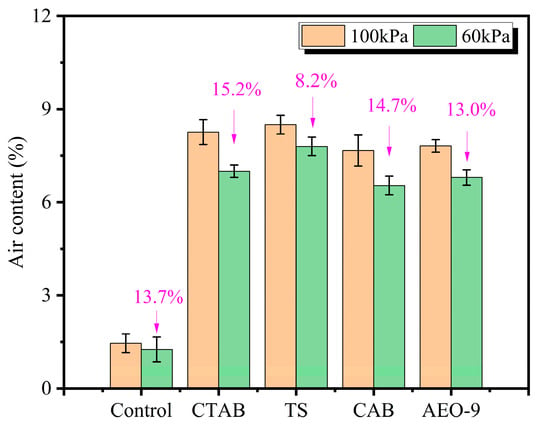

Currently, air content remains the controlling parameter for the frost-resistant design of concrete in cold regions. This section investigates the variation in air content for four types of air-entrained mortar, prepared under both low-pressure and normal-pressure conditions, with the results presented in Figure 10.

As shown in Figure 11, compared to the normal pressure environment, the air content of different types of air-entrained mortars decreases to varying degrees in the 60 kPa low-pressure environment, with an overall reduction range of 8.2% to 15.2%. This indicates that the low-pressure environment leads to a reduction in the air content of concrete, but the extent of reduction is related to the type of air-entraining agent used. The mortar specimen using the TS air-entraining agent exhibits the smallest reduction in air content, at 8.2%. The mortar specimen using the CTAB air-entraining agent shows the largest reduction in air content, at 15.2%. These findings demonstrate that selecting an appropriate air-entraining agent in low-pressure environments can mitigate the loss of air content in mortar.

Figure 11.

The effect of air-entraining agent type on the air content of cement mortar under different atmospheric pressures.

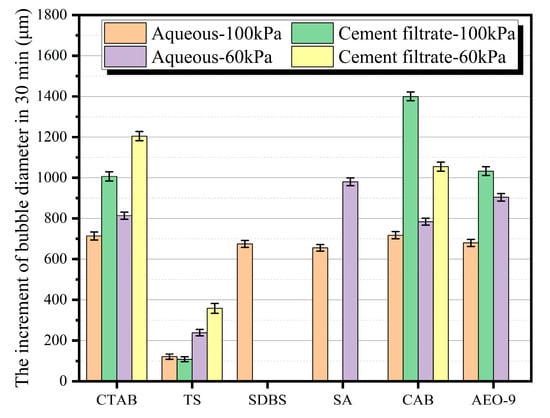

3.4.2. Internal Air-Void Structure of Hardened Mortar

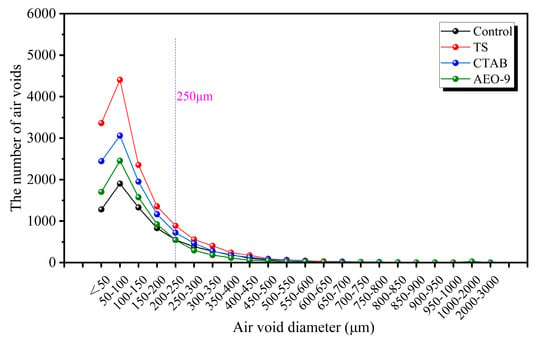

Figure 12 shows the internal pore structure of mortars incorporating different AEAs at 100 kPa. It can be observed from the figure that the number of pores smaller than 250 μm varies significantly among the different types of mortar. The content follows the order: TS group > CTAB group > AEO-9 group > Control group. It is noteworthy that the number of pores smaller than 250 μm introduced by the TS air-entraining agent is substantially greater than that introduced by the other two agents. Statistically, the number of pores smaller than 250 μm in the TS mortar is roughly twice that of the control, 1.3 times that of the CTAB mortar, and 1.7 times that of the AEO-9 mortar. Furthermore, Figure 12 also reveals that the primary difference in pore structure between mortars with and without AEAs lies in the quantity of pores smaller than 250 μm. This demonstrates that the fundamental role of AEAs is to introduce pores with diameters approximately less than 250 μm into the concrete. Increasing the number of these fine air bubbles can rapidly decrease the spacing factor, thereby enhancing the frost resistance of the concrete.

Figure 12.

The effect of different AEAs on the air-void structure of cement mortar at 100 kPa.

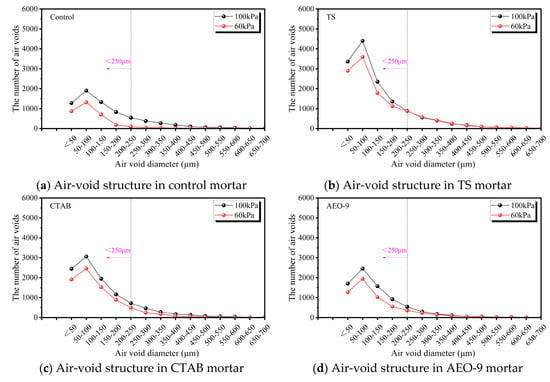

Figure 13 illustrates the differences in the pore structure within mortar specimens cast under 60 kPa and 100 kPa environments for the four types of mortar. It can be observed that specimens cast under the 60 kPa condition exhibit a reduction in the number of pores smaller than 250 μm to varying degrees compared to those cast under 100 kPa. Specifically, the number of pores smaller than 250 μm decreased by 51.48% in the reference group, 14.48% in the TS group, 25.64% in the CTAB group, and 27.55% in the AEO-9 group. This indicates that the reference group without any air-entraining agent experienced the most significant reduction in air-void content when atmospheric pressure decreased. The CTAB and AEO-9 groups showed relatively similar reductions, while the TS group exhibited the smallest decrease.

Figure 13.

The effect of atmospheric pressure on the internal air-void structure of cement mortar.

The TS molecule, characterized by its glycoside head group and rigid steroidal/triterpenoid skeleton, readily forms a “tough film” at the air-liquid interface. This film demonstrates high viscoelasticity and effective Gibbs/Marangoni restoration mechanisms. Additionally, the TS air-entraining agent exhibits relatively better tolerance to Ca2+ and high-alkaline environments. Consequently, although a reduction in fine pores still occurred under 60 kPa, the extent of this reduction (approximately 14.48%) was significantly smaller than that observed with CTAB and AEO-9. Considering foam performance and air-void structure, the saponin-based TS air-entraining agent is ideal for plateau-region concrete.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Significant differences exist in the foaming capacity and foam structure of different AEAs under normal pressure. At 100 kPa in deionized water, the initial foam height and time-dependent stability of TS, CAB, and CTAB are generally superior to those of AEO-9, SA, and SDBS. In terms of foam morphology, TS and CAB can maintain a higher density of small bubbles and a slower coalescence rate.

- (2)

- The solution type significantly alters the foaming performance and stability of different AEAs. Amphoteric/saponin-based AEA systems exhibit greater tolerance to strong electrolyte and high-alkali environments and better inhibit drainage and coalescence. In cement filtrate, the foam height and foam stability of all systems decreased significantly compared to those in deionized water, with SDBS, SA, and AEO-9 being the most affected; TS, CAB, and CTAB showed relatively smaller reductions.

- (3)

- A decrease in atmospheric pressure reduces the air content of mortar, but the extent of reduction depends on the type of AEA used. When the pressure decreased from 100 kPa to 60 kPa, the air content of the four air-entrained mortars decreased overall by 8.2–15.2%. Among them, the TS group had the smallest reduction (approximately 8.2%), while the CTAB group had the largest (approximately 15.2%).

- (4)

- The TS AEA possesses the best retention capability for fine air bubbles in cement mortar under low-pressure environments. At 60 kPa, the number of effective fine pores with a radius less than 250 µm in hardened mortar decreased compared to 100 kPa for all groups: the control, CTAB, and AEO-9 groups decreased by 51.48%, 25.64%, and 27.55%, respectively, whereas the TS group decreased by only 14.48%. TS not only generates a higher density of small bubbles during mixing but also more effectively suppresses coalescence and coarsening under low pressure and strong electrolyte conditions, making it most suitable as an air-entraining agent for plateau concrete.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.H.; Validation, L.L.; Investigation, Y.Z.; Resources, L.M.; Data curation, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Tianshan Talents” Leading Talents Training Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant number 2023TSYCLJ0056), the Directive Project of the Science and Technology Aid-Xinjiang Project Plan of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant number 2024E02035), and the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (grant number 2025SF-YBXM-537).

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Lianxia Ma and Yinbo Zhang were employed by the company Xinjiang Communications Construction Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fu, S.; Zhang, X.; Kuang, W.; Guo, C. Characteristics of Changes in Urban Land Use and Efficiency Evaluation in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau from 1990 to 2020. Land 2022, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Wang, T.; Chen, H.X.; Xue, C.; Bai, Y.H. Impact of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau’s Climate on Strength and Permeability of Concrete. China J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; He, R.; Guo, H. Confined photocatalysis and interfacial reconstruction for durability wettability in road markings. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2026, 729, 138902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dang, L.; Wang, C.; Wei, Z.; Han, D.; Chen, Z.; He, R. Effects of plateau environment on cement concrete properties: A review. J. Road Eng. 2025, 5, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Guo, J.; Hu, Y.Y.; Li, R.; Fang, J.H. Research progress on moisture transport and numerical simulation methods of cement-based materials. J. Chang’an Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.J.; Shao, Y.H.; Chen, M.T.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.Q.; Wang, W. Experimental study on frost resistance of manufactured sand concrete. Highw. Transp. Technol. 2025, 42, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, S.; Ke, W.; He, R. Air-Entraining Behavior of Concrete in Low Atmospheric Pressure Environments—A Review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2025, 1–45. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/61.1494.u.20250630.0929.002 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Huo, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; He, R. Impacts of Low Atmospheric Pressure on Properties of Cement Concrete in Plateau Areas: A Literature Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunstall, L.E.; Ley, M.T.; Scherer, G.W. Air entraining admixtures: Mechanisms, evaluations, and interactions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 150, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Fu, Z. The influence of low-pressure environment on the air content and bubble stability of concrete. J. Silic. Soc. 2015, 43, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, P. Effect of Low Atmospheric Pressure on Bubble Stability of Air-Entrained Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5533437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Tian, B.; Ge, Y.; Li, L. Effect of Low Atmospheric Pressure on Air Entrainment in Cement-Based Materials: An On-Site Experimental Study at Different Elevations. Materials 2020, 13, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Characteristics of Air Bubbles over the Life Cycle Under Low Air Pressure and Improvement of the Performance of Air En-trained Concrete; China National Building Materials Research Institute: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Effect of Low Atmospheric Pressure on Air Entraining Effectiveness and Pore Structure of Concrete; Institute of Technology Harbin: Harbin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Tian, B.; Li, L.H.; Ge, Y. Cement Concrete Properties under Low Atmospheric Pressures-A Short Review. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 49, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 175-2023; Common Portland Cement. Standardization Administration of China. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2023.

- ISO 679:2020; Cement—Test Methods—Determination of Strength. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Şahin, Y.; Akkaya, Y.; Boylu, F.; Taşdemir, M.A. Characterization of air entraining admixtures in concrete using surface tension measurements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 82, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zuo, W.; She, W. Using modified nano-silica to prevent bubble Ostwald ripening under low atmospheric pressure: From liquid foam to air-entrained cement mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 132, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Rizzo, F.; Palma, L.D. Lime and pozzolan-based matrices for an efficient immobilization of hazardous waste. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 313, 121735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG 3420-2020; Test Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Amani, P.; Miller, R.; Ata, S.; Hurter, S.; Rudolph, V.; Firouzi, M. Dynamics of interfacial layers for sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate solutions at different salinities. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 92, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Olsen, A.O.J.; Øye, G. The influence of divalent cations on the dynamic surface tension of sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate solutions. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 675, 132007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollpracht, A.; Lothenbach, B.; Snellings, R.; Haufe, J. The pore solution of blended cements: A review. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 3341–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ádám, A.A.; Ziegenheim, S.; Janovák, L.; Szabados, M.; Bús, C.; Kukovecz, Á.; Kónya, Z.; Dékány, I.; Sipos, P.; Kutus, B. Binding of Ca2+ Ions to Alkylbenzene Sulfonates: Micelle Formation, Second Critical Concentration and Precipitation. Materials 2023, 16, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Lattice Boltzmann study of the interaction between a single solid particle and a thin liquid film. Appl. Math. Mech. 2020, 41, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipov, V.P.; Arkhipov, R.V.; Filippov, A. Micellar and Extraction Properties of Ethoxylated Monoalkylphenols, a Review. J. Solut. Chem. 2025, 54, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, H.; Tanha, A.A.; Manshad, A.K.; Mohammadi, A.H. Experimental investigation of foam flooding using anionic and nonionic surfactants: A screening scenario to assess the effects of salinity and ph on foam stability and foam height. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14832–14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slowinski, E.J.; Gates, E.E.; Waring, C.E. The Effect of Pressure on the Surface Tensions of Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. 1957, 61, 808–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).