1. Introduction

Coalbed methane (CBM), as a significant unconventional natural gas resource, has an estimated recoverable reserve of approximately 260 trillion cubic meters globally, primarily distributed in countries such as China, the United States and Russia. As shallow CBM resources become increasingly depleted, development has shifted toward deep coal seams utilizing extended-reach horizontal wells [

1]. Deep seams, typically buried deeper than 1500 m, present substantial geological and engineering challenges. These include lithological heterogeneity, the presence of mechanically contrasting interlayers such as sandstone and mudstone, and weak intrinsic mechanical properties of coal—characterized by low elastic modulus and compressive strength as well as susceptibility to hydration and dispersion [

2]. Furthermore, tectonic compression and depositional compaction contribute to pronounced horizontal in situ stress anisotropy, which exacerbates stress concentration around wellbores and increases collapse risk [

3,

4]. Compared with conventional reservoirs, the mechanisms of wellbore instability in deep coal seams are more complex due to the widespread development of cleats, bedding planes and natural fractures, as well as coal’s degradation in strength under fluid interaction [

5]. High horizontal stress differences lead to complex stress redistribution around wellbores, triggering shear slip and structural failure [

6].

Numerous studies have been conducted to improve the understanding of wellbore stability in coal and shale formations. Gentzis [

7] emphasized the need for nonlinear strength criteria for coal under high-stress conditions. Gao et al. [

8] and Zhang et al. [

9] applied the Hoek–Brown criterion to evaluate collapse pressure and found that stress anisotropy and coal structure significantly affect wellbore stability. Yang et al. [

10] and Zhang et al. [

11] analyzed stress distribution around wellbores and confirmed that the orientation and magnitude of in situ stresses play a critical role in determining failure zones. Zhang et al. [

12] developed models incorporating bedding orientation and weak planes, while Ding et al. [

13] and Li et al. [

14] improved collapse prediction accuracy through experimental calibration. Despite these advances, integrated analyses that simultaneously consider in situ stress heterogeneity, coal structure and horizontal stress anisotropy remain limited.

In parallel, considerable research has been devoted to geomechanical modeling of wellbore stability using analytical, poroelastic and numerical approaches. Recent reviews summarize the main controlling factors and modelling techniques for wellbore stability in coalbeds, including analytical Mohr–Coulomb models, poroelastic formulations and thermo–hydro–mechanical (THM) coupling methods [

15,

16,

17]. Analytical and semi-analytical solutions have been developed for poroelastic and elastoplastic media subjected to non-hydrostatic far-field stresses [

18,

19,

20], and related geomechanical frameworks have also been proposed for assessing the technical condition of underground excavations and mine workings [

21]. Finite-element and damage-coupled methods have been used to investigate wellbore stability in transversely isotropic rocks, showing that bedding-related anisotropy can significantly change the orientation and magnitude of near-wellbore stresses [

22,

23,

24]. For coal seams, case studies further highlight the role of in situ stress differences and faulting regimes in controlling wellbore integrity [

25,

26,

27]. Another important line of research concerns the interaction between drilling fluids and coal. Laboratory experiments consistently show that filtrate invasion and chemical reactions can degrade the strength and stiffness of deep coal seams, increasing the risk of collapse [

28,

29], and tailored drilling-fluid systems have been developed to minimize coal damage and facilitate clean-up [

30].

Nevertheless, there is still a lack of simple, field-oriented workflows that quantitatively link laboratory-measured coal properties, log-derived in situ stress anisotropy and collapse-equivalent mud density for horizontal wells in deep coal seams. The present study aims to fill this gap by developing a laboratory-calibrated framework for wellbore stability analysis of extended-reach horizontal wells in deep coal seams under heterogeneous in situ stresses. Coal-core mechanical parameters are obtained from uniaxial and triaxial tests and used to calibrate a Mohr–Coulomb-based collapse model. The in situ stress tensor and pore pressure are inferred from logs and regional data, and the near-wellbore stress distribution is calculated for inclined and horizontal trajectories under different horizontal stress ratios. Using six wells from the Ordos Basin as examples, we quantify how horizontal stress anisotropy modifies circumferential stress concentration and collapse-equivalent mud density, and we derive trajectory-sensitivity maps that can guide mud-weight selection in deep coal seams. Compared with previous studies, the main contribution of this work is to provide a process-oriented workflow that links laboratory measurements, log-derived stress anisotropy and engineering design parameters for extended-reach coal-seam wells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rock-Mechanics Testing and Sample Preparation

To simulate the in situ stress conditions of underground rock and to analyze its mechanical behavior, conventional triaxial rock-mechanics experiments were conducted. In actual subsurface environments, rocks are subjected to forces from three principal directions: the overburden pressure, the maximum horizontal stress, and the minimum horizontal stress, all of which are unequal in magnitude. Although true triaxial tests more accurately represent these conditions, they are difficult to perform; therefore, conventional triaxial tests were employed as an alternative. In these experiments, axial loading is applied to simulate the vertical overburden stress, while lateral confining pressure is imposed to represent the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses. Generally, as confining pressure increases, rock porosity decreases and strength increases, often leading to a transition from ductile to brittle behavior.

Due to the widespread development of cleats, fractures, and weak structural planes in coal–rock, its strength is significantly lower than that of sandstone or shale, making it more prone to fragmentation. Therefore, care must be taken during handling, drilling, and cutting to avoid artificially induced damage. In this study, a total of 43 coal–rock core samples were collected from the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. Large coal blocks were processed into standard core samples with dimensions of 25 mm × 50 mm using a wire-cutting technique. The ends of the cylindrical samples were ground flat in accordance with the preparation standards recommended by the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM) [

31,

32,

33].

2.2. Experimental Equipment and Testing Procedure

The experimental apparatus used in this study was the RTR-1000 (GCTS Testing Systems, Tempe, AZ, USA) triaxial rock-mechanics testing system, as shown in

Figure 1. The machine is designed with a maximum confining pressure of 140 MPa, a maximum axial static load of 1000 kN, a maximum axial dynamic load of 800 kN, and can accommodate specimens up to 54 mm in diameter. All test conditions and data acquisition are fully computer-controlled, enabling precise evaluation of the mechanical properties of rock under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions equivalent to depths up to 2162.9 m.

A total of 14 core samples were collected from four case study wells for uniaxial and conventional triaxial compression tests. In the Ordos Basin case study, the wells analyzed in this work are extended-reach horizontal CBM wells targeting deep coal seams in the Taiyuan, Shanxi and Benxi Formations. In the field development, these wells typically have measured depths on the order of 3.0–3.6 km, with horizontal sections of approximately 0.8–1.2 km drilled within the target coal seams. The 14 coal-core samples listed in

Table 1 were taken from four case-study wells at vertical depths of about 1.9–2.2 km, i.e., from the same coal seams that are intersected by the horizontal sections of the extended-reach wells. In this way, the laboratory-derived mechanical parameters (UCS, elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, cohesion and friction angle) are representative of the formations encountered along the extended-reach horizontal sections.

2.3. Stress Transformation and Near-Wellbore Stresses

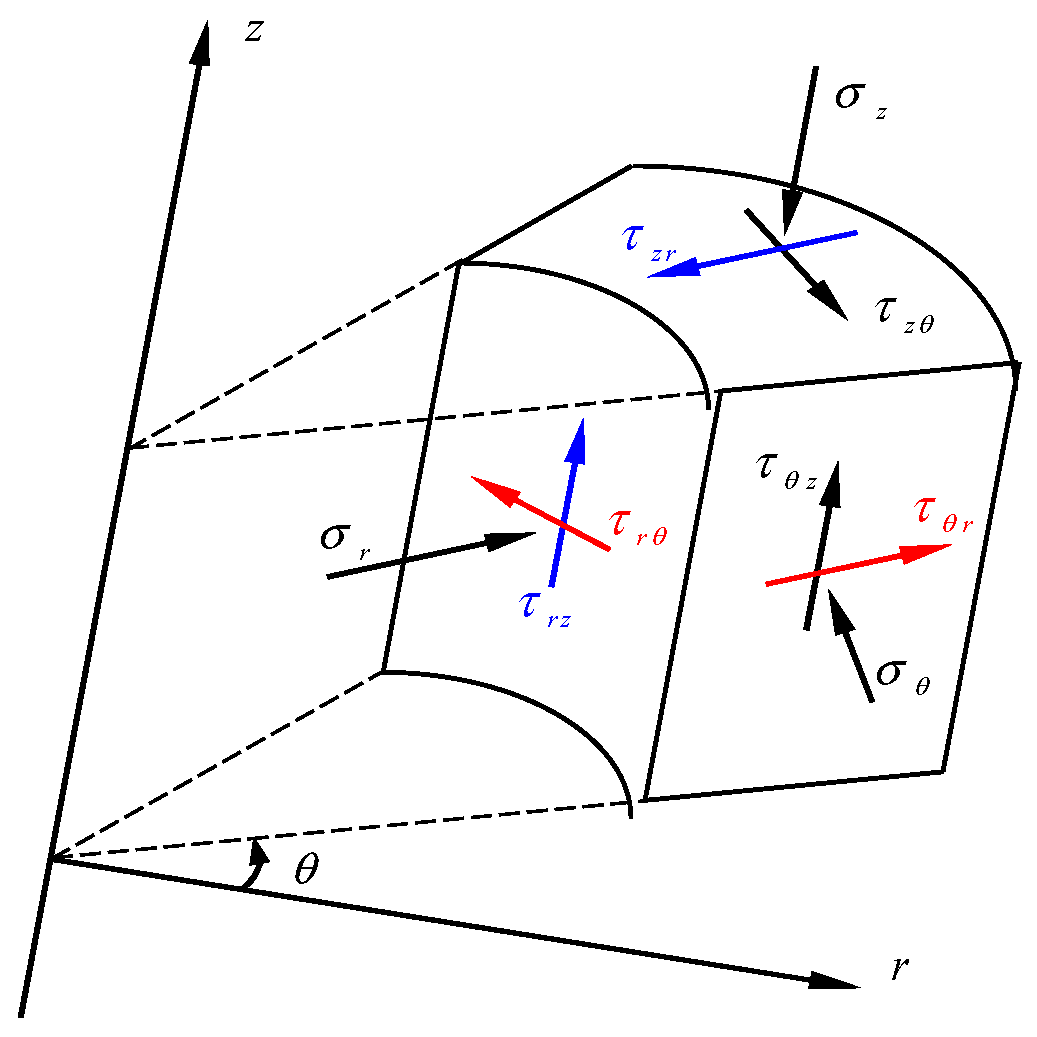

Drilling within a rock mass induces stress concentration effects around the wellbore. In this study, the rock mass is assumed to be a homogeneous, linear-elastic, and isotropic medium. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the wellbore coordinate system is transformed using a Cartesian coordinate transformation, simplifying the in situ stress state of the coal seam to a triaxial principal stress condition. A mathematical model is developed to describe the circumferential stress distribution around a horizontal wellbore at a depth of 2000 m in a deep coal seam. The stress state at any point along the inclined wellbore is analyzed. The stability of the wellbore is then evaluated based on the calculated effective stress acting on the wellbore surface [

34].

In this study, the rock mass is treated as a homogeneous, isotropic and linear-elastic continuum at the wellbore scale in order to enable an analytical collapse analysis. Although deep coal seams commonly contain cleats and bedding planes, the available caliper and production records for the case wells do not indicate pervasive large-scale fractures controlling the observed drilling response. The present results should therefore be viewed as conservative, first-order estimates; in strongly cleated or highly anisotropic coals, additional elastoplastic or damage-based modeling that explicitly incorporates weak planes would be required.

The analysis is intended for short-term stability during drilling. In the case wells, the open-hole exposure time of the coal-seam interval was typically limited to several days, and no obvious progressive enlargement of the borehole was reported in the drilling records. Under these conditions, failure is treated as an instantaneous elastic–plastic process and long-term creep deformation is neglected.

The coordinate system of the principal in situ stresses is rotated into the (x,y,z) coordinate system, as illustrated in the figure. The transformation between coordinate systems can be described using direction cosines. The corresponding direction cosine matrix is given as follows:

The stress components in the (x,y,z) coordinate system can be transformed as follows:

After linear superposition, the expression for the stress distribution around the wellbore is

Here, is the wellbore radius, is the radial distance from the wellbore center ( ≥ ), and is the circumferential angle measured from the direction of the maximum horizontal in situ stress. , and are the corresponding shear stress components in the , and planes

At the wellbore (

r =

R), the stress components can be expressed in terms of the in situ stresses

(maximum horizontal principal stress),

(minimum horizontal principal stress), and

(vertical stress):

where

2.4. Collapse-Pressure Evaluation in Deep Coal Seams (Mohr–Coulomb Criterion)

As described in the previous section, based on the expression of wellbore stress, formation failure occurs on the

plane. The stress distribution of a rock element on the inclined wellbore is illustrated below, as illustrated in

Figure 3 [

35]:

According to stress analysis, the relationships between the normal and shear stresses on an inclined plane at an angle

to the z-axis (in the same direction of

) and the stress components are as follows:

To determine the principal stresses, set the derivatives of the normal and shear stresses with respect to

to zero, i.e.,

, yielding two angles differing by 90°:

Substituting these angles

and

into Equation (7) allows for the calculation of two undetermined principal stress values, denoted as

and

. Thus, the three principal stresses on the inclined wellbore are determined as follows:

where

represents the hydrostatic pressure exerted by the drilling-fluid column, MPa.

The normal and shear stresses (

and

) at any point on the wellbore can be expressed in terms of the principal stresses

and

:

The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion is rewritten as follows:

where

To capture stress concentration effects beyond the circular-hole assumption, an elliptic-wellbore pressure model was also considered in recent analyses, which refines the circumferential stress evaluation and the resulting density envelope [

18]. The formulation of the mud-weight window (MWW) was aligned with petroleum engineering practice by constraining the lower bound with pore pressure and collapse criteria and the upper bound with fracture initiation/propagation criteria. A recent comprehensive synthesis consolidates these design constraints and engineering caveats, which are adopted herein to set the computation envelope [

33,

36].

Software. MATLAB R2023b (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) was used for figure plotting (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). OriginPro 2024 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) was used for figure plotting (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

3. Results

3.1. Rock-Mechanics Characterization

The rock-mechanics parameters of the coal–rock samples from case study wells in the Ordos Basin are shown in

Table 2, as determined through rock-mechanics experiments. Based on the stress–strain curves, the elastic modulus and compressive strength of the coal–rock cores under different confining pressures were obtained. Using the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, the cohesion and internal friction angle of the cores with different bedding angles were calculated. Specifically, the elastic modulus ranges from 1.58 to 18.78 GPa; the Poisson’s ratio ranges from 0.34 to 0.48; and the uniaxial compressive strength ranges from 8.25 to 12.53 MPa.

3.2. Directional Contrast of Circumferential Stress at ~2000 m

The fundamental parameters obtained through coal–rock mechanical property experiments and the established mathematical models are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Using the calculation models described in Equations (1)–(6), the circumferential stress distribution around deep coal-seam wells in the Ordos basin was analyzed.

A mathematical model was established to calculate the wellbore stress distribution in case study well 1 to 3 at a vertical depth of 2000 m. The variations in circumferential stress with depth were analyzed at wellbore circumferential angles of 0° (maximum horizontal stress direction) and 90° (overburden stress direction). The results show that radial, circumferential, and axial stresses all increase with depth, with the circumferential stress exhibiting the most significant increase. This indicates that the wellbore is subjected to greater tensile or shear stress, thereby increasing the risk of failure or instability.

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the variation in principal stresses with depth and azimuth. At 2000 m in wells 1–3, circumferential stress along

= 90° ranges from 100 to 120 MPa, approximately 20 MPa higher than that at

= 0°. In case study wells 4–6 (as shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), this disparity increases significantly to 40–50 MPa, with

= 90° reaching up to 140 MPa. Circumferential stress shows the steepest growth with depth and becomes the dominant stress component near the wellbore wall. These results underscore the intensifying stress asymmetry with depth, especially perpendicular to the minimum horizontal stress direction, and highlight its critical role in triggering localized collapse. This insight is essential for directional trajectory design and mud-weight optimization.

In the coal-seam horizontal sections (inclination 90°),

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate how the three borehole-wall stress components vary with depth and azimuth. For each case well, the circumferential stress

, axial stress

and radial stress

are plotted as functions of depth at different azimuths β, with compression taken as positive and all values expressed in MPa. The upper curve in each panel corresponds to

, the middle curve to

and the lower curve to

, indicating that the circumferential component consistently dominates the near-wellbore stress state, followed by the axial and radial components. Results are shown for circumferential angles

= 0° and

= 90°, which represent directions where the calculated circumferential stress is relatively high. At a given depth and azimuth,

is systematically larger at

= 90° than at

= 0°, reflecting a pronounced azimuthal asymmetry in the circumferential stress concentration. This pattern provides the mechanical basis for the collapse-prone sectors identified in the subsequent trajectory-sensitivity analysis.

3.3. Effect of Horizontal Stress Ratio on Minimum Collapse Equivalent Density

To investigate collapse pressure under different horizontal stress ratios, iterative calculations using the Mohr–Coulomb criterion were conducted for case study well 2 and 5. The results are shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

As the horizontal stress ratio n increases from 1.07 to 1.28 (corresponding to a differential of 3 to 7 MPa), the equivalent mud density required to maintain wellbore stability increases from 1.53 to 1.77–1.81 g/cm3, reflecting a 15.7–18.3% increase. The sharpest density rise occurs at well inclinations of 0–40° and azimuths of 90–270°, aligned perpendicular to the minimum horizontal stress. In case well 5, this demand exceeds 1.8 g/cm3 under high stress contrast. These findings confirm a strong positive correlation between stress anisotropy and collapse risk, particularly when deviating from principal stress directions.

The monotonic increase in the required collapse mud density with a larger horizontal stress contrast is consistent with field-calibrated wellbore-stability analyses in shale formations, where the safe density window narrows as in situ stress anisotropy grows [

20].

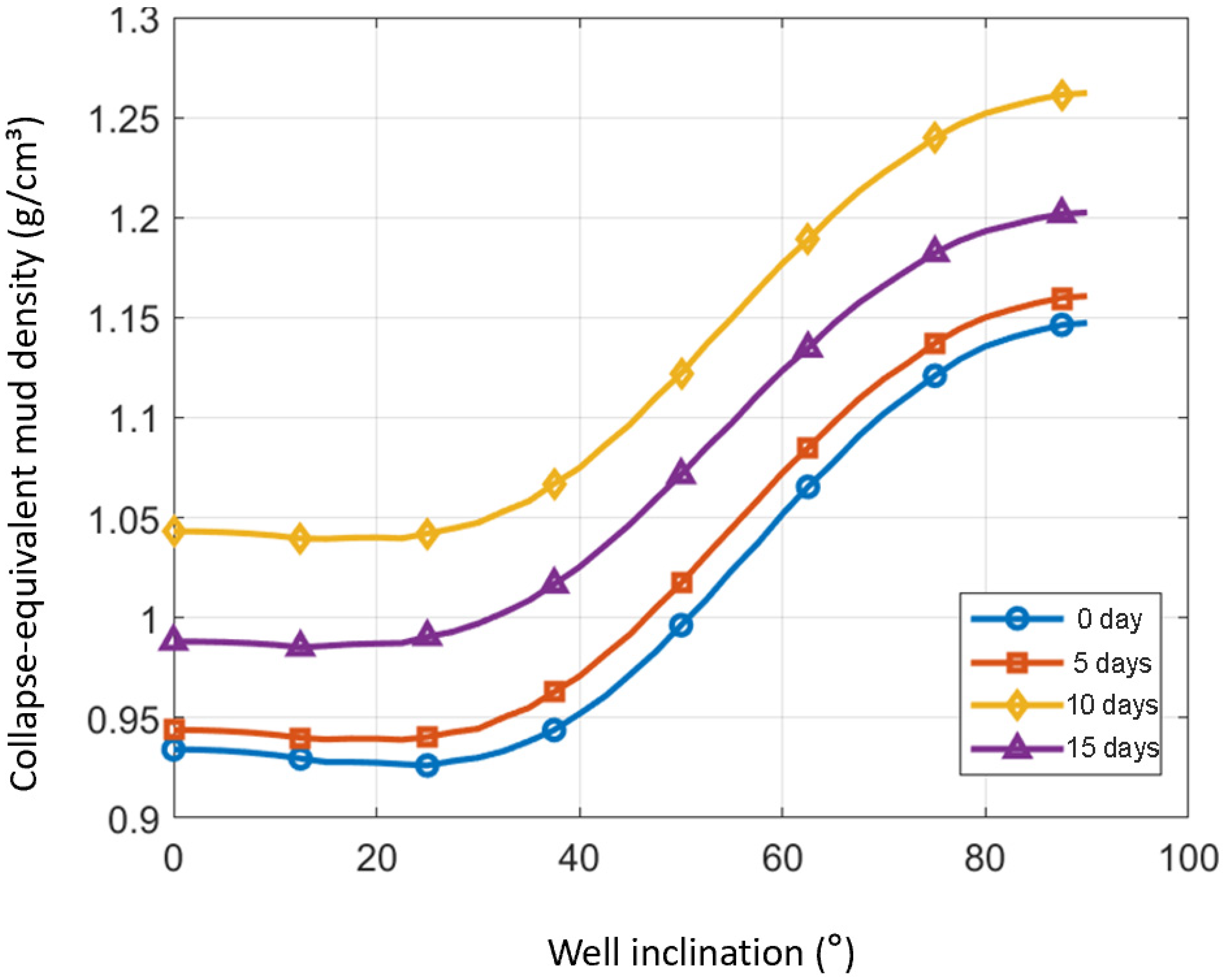

3.4. Influence of Drilling-Fluid–Coal Interaction on Coal Mechanical Properties and Collapse Pressure

To quantify the time-dependent effect of drilling fluid on coal strength, core samples from coal seams A and B of the case well were immersed in a field water-based drilling fluid and then tested after soaking times of 0, 5, 10 and 15 days. Triaxial compression tests were conducted at a confining pressure of 40 MPa, and the compressive strength, Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio were obtained for each soaking duration. In addition, the linear swelling ratio was monitored to characterize the hydration and expansion behavior.

The experimental results (

Figure 12) demonstrate that the compressive strength of both seams decreases monotonically with soaking time. After 15 days of exposure to the drilling fluid, the strength reduction reaches approximately 30–40% compared with the unsoaked state, indicating pronounced weakening of the coal skeleton due to water invasion and clay hydration. The corresponding Young’s modulus (

Figure 13) also shows a continuous decrease with time; in some samples the modulus is reduced by more than 50%, reflecting the progressive loss of stiffness and the development of micro-cracks within the coal matrix. In contrast, Poisson’s ratio and the swelling ratio (

Figure 14) increase with soaking time, which implies a transition from relatively stiff and brittle behavior to a more deformable and volumetrically expansive response. Coal seam B is consistently more sensitive to drilling-fluid exposure than seam A, with larger strength loss, stronger modulus reduction and higher swelling. This can be attributed to its higher content of swelling clay minerals and more developed cleat and fracture networks, which facilitate fluid penetration and hydration.

The time-dependent mechanical parameters were then incorporated into the wellbore stability model. For each soaking duration, the cohesion and internal friction angle were updated according to the measured strength and deformability, and the corresponding collapse mud weight was recalculated as a function of well inclination. As shown in

Figure 15, the collapse pressure increases with both inclination angle and soaking time. For the high-inclination section of the case well, the required mud density after 10–15 days of exposure is approximately 0.10–0.15 g/cm

3 higher than that before soaking, and the safe mud-weight window becomes noticeably narrower. These results clearly indicate that drilling-fluid–coal interaction exerts a non-negligible control on wellbore stability: prolonged contact with the drilling fluid leads to time-dependent weakening of the coal seams, which in turn elevates the collapse pressure and shortens the safe drilling period.

From an operational point of view, the findings suggest that the drilling fluid for deep coal-seam horizontal wells should combine sufficient density with strong inhibition and plugging capacity to minimize hydration and strength degradation. At the same time, the open-hole exposure time in the coal-bearing interval of the case well should be kept within the calculated safe period, and unnecessary waiting or long tripping operations should be avoided. These recommendations provide a quantitative basis for selecting drilling-fluid properties and planning the drilling schedule in deep coal seams, so as to mitigate time-dependent collapse risk and ensure safe and efficient drilling.

3.5. Comparison with Field Mud Weights

Model predictions were also compared with field mud-weight data to provide an indirect validation of the framework. For multiple trajectory samples in the coal-seam horizontal sections,

Figure 16 plots the field mud density against the corresponding predicted minimum collapse-equivalent mud density, together with a 1:1 reference line. All case points fall on or slightly above this line, indicating that the mud weights used in the field are consistently equal to or higher than the model-predicted lower-bound densities. No severe borehole collapse has been reported in these sections, which is consistent with the conservative nature of the predictions. Although this comparison cannot replace detailed validation using image logs or microseismic monitoring, it provides supportive evidence that the proposed model yields reasonable collapse-equivalent mud densities for the studied deep coal-seam wells.

4. Discussion

This study integrates laboratory-measured coal mechanical properties with log-derived in situ stresses to quantify the influence of horizontal stress anisotropy on wellbore stability in deep coal seams. The circumferential-stress calculations in

Section 3.2 show that at a depth of about 2000 m, the circumferential stress along

= 90° exceeds that along

= 0° by approximately 20 MPa in case wells 1–3 and by 40–50 MPa in case wells 4–6. In other words, the near-wellbore stress field becomes strongly asymmetric with depth, and the direction perpendicular to the minimum horizontal stress is subject to the highest compressive and shear stresses. The collapse analyses in

Section 3.3 further indicate that when the horizontal stress ratio

increases from 1.07 to 1.28, the minimum collapse-equivalent mud density for the horizontal coal-seam section rises from about 1.53 to 1.77–1.81 g/cm

3, corresponding to an increase of approximately 15–18%. For a given coal strength, the safe mud-weight window therefore narrows appreciably as the horizontal stress difference grows, even if the vertical stress and pore pressure remain unchanged. This strong sensitivity highlights that the commonly neglected heterogeneity of the horizontal stress field can be a first-order control on mud-weight design for extended-reach coal-seam wells [

37,

38,

39].

These findings can be placed in the context of previous analytical and numerical studies as follows. The magnitude and trend of this stress-ratio effect are broadly consistent with previous analytical and numerical studies of wellbore stability under anisotropic stress fields in coal and shale formations. Transversely isotropic and anisotropic poroelastic models have shown that increasing horizontal stress difference intensifies circumferential stress concentration and can shift the most critical azimuth for collapse in inclined and horizontal wells. Case studies in coal seams likewise indicate that large horizontal stress differences and strike–slip or reverse-faulting regimes promote instability in horizontal wells and require higher mud densities to maintain borehole integrity. Compared with these studies, the present framework provides a laboratory-calibrated quantification of how realistic changes in the horizontal stress ratio modify collapse-equivalent mud density in deep coal seams, using six wells from the Ordos Basin as examples. By explicitly combining core-derived Mohr–Coulomb parameters with log-derived stress tensors, the approach helps to bridge the scale gap between laboratory measurements and field-scale design.

Beyond stress anisotropy, drilling-fluid–coal interaction also exerts a strong control on coal mechanical behavior. The new soaking experiments presented in

Section 3.4 further demonstrate that drilling-fluid–coal interaction can significantly alter coal strength and deformability over time. Core samples from two coal seams were soaked in a representative field water-based drilling fluid for up to 15 days, and triaxial tests at 40 MPa confining pressure were carried out after each soaking period. The results show that the triaxial compressive strength decreases by roughly 30–40% and the Young’s modulus by more than 50% in some samples, whereas Poisson’s ratio and the swelling ratio increase with soaking time. These trends indicate progressive weakening and softening of the coal skeleton due to water invasion and clay hydration, consistent with previous observations of drilling-fluid-induced degradation in deep coal seams. When the time-dependent mechanical parameters are propagated into the collapse model, the required mud density increases systematically with soaking time: for the high-inclination section of the case well, the collapse-equivalent density after 10–15 days of exposure is about 0.10–0.15 g/cm

3 higher than that for unsoaked coal, and the safe mud-weight window becomes noticeably narrower. From an operational perspective, these results emphasize that both fluid formulation (inhibition, plugging and filtrate control) and open-hole exposure time need to be managed carefully in deep coal-seam drilling.

To further examine the practical applicability of the model, the predictions were compared with field mud weights. Model predictions have also been compared with field mud-weight data as an indirect validation of the framework. For multiple trajectory samples along the coal-seam horizontal sections,

Figure 16 plots the field mud density against the corresponding predicted minimum collapse-equivalent mud density. All case points lie on or slightly above the 1:1 reference line, indicating that the mud weights used in the field are consistently equal to or higher than the model-predicted lower-bound densities. In addition, the drilling records for these sections do not report severe borehole collapse. Although this comparison cannot replace detailed validation using image logs, caliper logs or microseismic monitoring, it provides supportive evidence that the proposed model yields reasonable lower-bound estimates of collapse pressure for the studied deep coal-seam wells and does not underestimate the required mud density under the given assumptions.

Several limitations of the present framework should be acknowledged. First, the coal around the wellbore is treated as a homogeneous, isotropic and linear-elastic continuum. The available field data indicate limited macro-fracturing in the studied seam, and our laboratory tests do not show pronounced strength anisotropy, which partly justifies this assumption. Nevertheless, in strongly cleated, bedded or structurally complex coals, the model may underestimate collapse risk, and extended elastoplastic or damage-based formulations that explicitly incorporate weak planes and structural anisotropy would be desirable. Second, the analysis focuses on short-term stability during drilling. In the case wells, the open-hole exposure time of the coal-seam interval was typically limited to several days, and no obvious progressive enlargement is reported; accordingly, failure is treated as an instantaneous elastic–plastic process and long-term creep deformation is neglected. For long-term stability assessment (e.g., production wells or shut-in stages), fully coupled time-dependent models that include coal creep and rheology would be required. Third, drilling-fluid-induced weakening is incorporated in a simplified way—through the interpretation of soaking tests and the choice of conservative strength parameters—while the fully coupled evolution of pore pressure, filtrate invasion and chemical damage is not resolved. Finally, the lack of direct image-log or microseismic observations of borehole failure means that model validation is based on indirect comparison with mud weights and drilling records.

Despite these limitations, the proposed workflow provides a practical bridge between rock-mechanics experiments, log-derived in situ stresses and engineering design parameters for deep coal-seam wells. Future work should extend the framework by incorporating anisotropic strength models for weakly structured coals and coal–parting systems, coupling the collapse analysis with poroelastic or thermo–hydro–mechanical formulations to evaluate long-term stability and drilling-fluid invasion effects, and applying the methodology to wells with comprehensive monitoring (image logs, caliper logs and microseismic data) to further validate and refine the model. Such extensions will help to calibrate probabilistic safety factors for field applications in deep CBM developments and to support more robust wellbore-stability management in complex stress environments.