Abstract

Mechanical forces, chemical and electrochemical reactions, and environmental variables can all lead to surface degradation of parts. Composite coatings can be applied to these materials to enhance their surface characteristics. Recently, nickel-based composite coatings have gained greater attention because of their remarkable wear resistance. The efficiency, precision, and affordability of this process make it a popular method. In addition, electroplating nickel-based composites offers a more environmentally friendly alternative to traditional dangerous coatings such as hard chrome. Tribological and wear characteristics are highly dependent on several variables, such as particle parameters, deposition energy, fluid dynamics, and bath composition. Mass loss, coefficient of friction, hardness, and roughness are quantitative properties that provide useful information for coating optimization and selection. Under optimized electrodeposition conditions, the Ni-SiC-graphite coatings achieved a 57% reduction in surface roughness (Ra), a 38% increase in microhardness (HV), and a 25% reduction in wear rate (Ws) compared to pure Ni coatings, demonstrating significant improvements in tribological performance. Overall, the incorporation of SiC nanoparticles was found to consistently improve microhardness while graphite or MoS2 reduces friction. Differences in wear rate among studies appear to result from variations in current density, particle size, or test conditions. Furthermore, researchers run tribology studies and calculate the volume percentage using a variety of techniques, but they fall short in providing a sufficient description of the interface. This work primarily contributes to identifying gaps in tribological research. With this knowledge and a better understanding of electrodeposition parameters, researchers and engineers can improve the lifespan and performance of coatings by tailoring them to specific applications.

1. Introduction

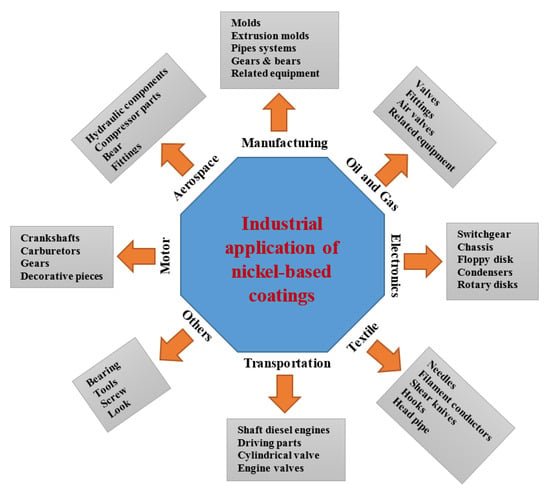

Tribology significantly impacts energy consumption, emissions, and operating costs by influencing friction and wear. Studies estimate that tribological contacts account for approximately 23% of global energy consumption, with 3% used for repairing worn components and 20% for reducing friction [1]. In the mining sector, they contribute 970 million tons of CO2 per year (2.7% of global emissions) [2]. These figures highlight the importance of improving tribological efficiency, which directly influences the selection of electrodeposition parameters for nickel matrix composite coatings. Several technologies and methods exist for reducing wear and friction, each suited to a particular use case [1]. In engineering systems, the predominant technique for controlling friction and minimizing wear during metal-to-metal contact is still liquid lubrication, such as oil. However, the use of liquid lubricants in tribology is limited by several drawbacks, including contamination from liquid lubrication, temperature limitations (oxidation and degradation), and liquid instability [3]. Also, due to health, safety, and environmental concerns related to hexavalent chromium, a dangerous and cancer-causing type of chromium, traditional chromium (Cr) coatings have been replaced by alternative solutions [4]. New, more environmentally friendly strategies, while maintaining acceptable wear and friction management, will be explored in the coming century. To improve the tribological characteristics of contact surfaces, methods for producing composite coatings encapsulated in reinforcing particles are frequently employed [5,6]. These recent advances are mainly the result of initiatives to eliminate chrome coatings and new production nanotechnologies. Low friction and wear tribological coatings are also highly sought after in many sectors. They are frequently used to reduce wear and friction when traditional lubricants fail to provide the required level of durability and performance under demanding application conditions [7].

Nickel-based composite coatings provide a promising alternative to traditional hard chrome coatings due to reduced toxicity and environmental impact. Compared to DLC and PVD nitride coatings, Ni-based composites generally require lower deposition energy and can incorporate reinforcing particles such as SiC or graphite, which can enhance wear resistance while enabling recyclability. However, nickel production and supply are subject to geopolitical and economic fluctuations, as major sources are concentrated in a few countries, which may affect material availability and cost. Life-cycle analyses (LCA) indicate that, although energy consumption during deposition is moderate, proper management of nickel-containing waste is critical to minimize environmental impact. Thus, Ni-based composites offer a balance of tribological performance and ESG compliance, but supply chain considerations must be taken into account for industrial adoption.

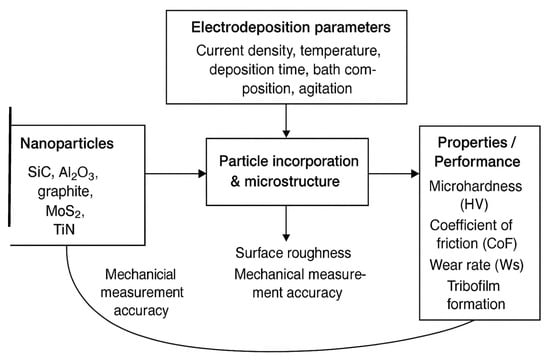

Comparing electrodeposited composite coatings to conventional monometallic coatings reveals a significant improvement. Metal matrix compositions (MMCs) allow the development of coatings with exceptional performance and adapted to specific applications by merging the qualities of many materials. The mechanical, chemical, and functional properties of coatings can be significantly enhanced by the addition of dispersed phases, such as ceramic nanoparticles, carbides, oxides, or polymers. Due to the continuous improvement of material combinations and deposition techniques, composite coatings have the potential to have a major impact on various industrial applications. Nickel-based alloys are used in the industrial production of MMCs because of their low cost and superior performance compared to other materials. Nanomaterials are superior to micro materials in terms of thermal, chemical, biological, optical, electrical, magnetic, hardness, and stiffness properties. Therefore, they are generating considerable interest in the development of composite materials. Understanding the properties and characteristics of these composite coatings is essential for optimizing their effectiveness in certain applications [8,9,10,11]. Several deposition parameters, such as bath temperature, pH, current density, agitation, and bath composition, critically influence the incorporation of co-deposited particles. For example, higher current densities can increase the deposition rate but also affect particle trapping efficiency, while bath temperature and pH modify the adsorption kinetics of particles on the cathode surface. Agitation ensures homogeneous particle distribution and prevents sedimentation, directly impacting the uniformity of the composite coating. By carefully adjusting these parameters, the microstructure and functional properties of nickel matrix composite coatings can be controlled. Thus, co-electrodeposition has become a key technique for producing customized protective coatings with controlled particle incorporation and optimized performance [12]. In order to create customized protective composite coatings by modifying their microstructure through adjustments of process parameters, co-electrodeposition has thus emerged as a fundamental application technique for industrial production [12].

The coating is ineffective because the particles agglomerate due to the high ionic concentration of the electrolyte and the high concentration of inert particles in the bath. Physicochemical techniques can solve this agglomeration problem. The following strategies have been described in the literature: (i) pulsed electrodeposition; (ii) ultrasonic vibrations; (iii) use of dispersing agents; and (iv) reduction in the ionic concentration of the bath [10,13,14,15].

Conducting tests requires significant time, energy, and resources. Numerical approaches, capable of predicting and modeling a wide range of events, they have been developed to address the problem of selecting production parameters for composite coatings. These methods are more efficient for analyzing experimental data and are employed when accurate mathematical models are unavailable. Examples of numerical techniques used in this context include the Taguchi approach, the RSM, the CCD method and ANOVA [16,17,18,19], artificial neural networks (ANNs) [20], and gray relationship analysis (GRA) [18,19].

This section below reviews the work of researchers on the main techniques for producing nanocomposite coatings and examines the influence of processing parameters on nanoparticle incorporation and the resulting tribological performance. It also evaluates existing methodological approaches and key results in order to define a structured framework for future research.

Using pulsed jet electrodeposition technology, H. Liu et al. (2025) [21] exploited the properties of electrochemical deposition. According to the findings, the deposition temperature has a greater impact on the coating’s characteristics than any other factor. The micro-hardness of composite coatings has increased by 113.75% to 652.85 HV, while the average wear width and coefficient of friction have dropped by 40% and 4.13 to 0.73 and 383.6 μm, respectively.

T. Guan et al. (2024) [8] focused primarily on the development of nickel-based nanocomposites, obtained by electrodeposition and enriched with lubricating nanoparticles such as graphene, MoS2, PTFE, and WS2. Their work also addresses methods for dispersing these nanoparticles in the electrolytic solution to prevent their aggregation. Nickel and nanomaterial deposition models are presented, and the main factors influencing this process are analyzed. In addition to their potential applications and advantages, the mechanical properties, tribological performance, and surface wettability of these nickel-based nanocomposites are also studied in detail.

Composite coatings based on nickel that are supplemented with various particles (Al2O3, SiC, ZrO2, WC, and TiO2) have been developed in detail by D. M. Zellele et al. (2024) [10] in order to greatly enhance a number of significant functional aspects of different substrates. The homogeneous dispersion of these particles within the nickel matrix creates wear resistance. Additionally, by decreasing dislocation mobility and matrix grain size, these particles improve the material’s mechanical strength.

The effect of several current modes (DC, PC, and PNPC) on the creation of a Ni-TiN composite coating was investigated by C. Ma et al. in 2024 [22]. The results demonstrated that the PC electrodeposited Ni-TiN coatings had smoother surfaces, finer grains, and stronger interface-bonding strength, while the PNPC electrodeposited Ni-TiN composite coatings had the densest structure and the highest interface strength when compared to DC electroplating. TiN nanoparticle incorporation was improved by pulsed current electroplating; positive-negative pulsed current electroplating showed a greater deposition rate than positive pulsed current electroplating. Additionally, the PNPC electrodeposited coating showed the best wear and friction characteristics and enhanced microhardness.

It has been shown that the incorporation of nanoparticles significantly improves the overall properties of Ni-based coatings (Y. Li et al., 2024) [23]. Moreover, when Al2O3 and PTFE nanoparticles are progressively added to the plating bath, the toughness and wear resistance of the Ni–Al2O3–PTFE nanocomposite coating exhibit a characteristic trend of initial strengthening followed by subsequent weakening. Under optimal conditions—specifically, 40 mL/L Al2O3 nanoparticles and 10 mL/L PTFE—the elastic recovery ratio can reach 0.46. In addition, the average friction coefficient and surface roughness can be reduced to as low as 0.09 and 42 nm, respectively.

To investigate the influence of TiN nanoparticle size on the microstructure and properties of prefabricated Ni–TiN thin coatings, H. Zhang et al. (2021) [24] employed the MAPE technique. When TiN nanoparticles with a size of 32 nm were used, the resulting coating exhibited a compact, uniform, and fine microstructure, characterized by narrowly distributed TiN nanoparticles and refined Ni grains. Moreover, the coating fabricated with these small-sized nanoparticles demonstrated the lowest wear mass loss, measured at only 36.4 mg.

To reduce the negative impact of surface flaws in coatings caused by CeO2 nanoparticle aggregation, R. An-hua et al. (2021) [25] employed the jet electrolytic deposition method. In order to achieve Ni-CeO2 composite coatings at varying current densities, they applied a vertical magnetic field during the jet electrolytic deposition procedure. The results demonstrate that the magnetic field’s magneto-hydrodynamic action results in the regularly arranged particles of the composite coatings. As the current density rose, the microhardness, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance first increased but subsequently declined. With a microhardness value of up to 665.78 HV and high surface density and flatness, the composite coating was created at a processing current density of 20 A/dm2. Additionally, it showed the highest level of wear resistance.

Utilizing circulating solution electrodeposition (CSD) with different SiC concentrations, this apparatus applies Ni–SiC composite coatings to the interior surfaces of cylinders. Y. Zhou and colleagues created a novel composite electroplating device in 2021 [26]. According to the results, the predominant wear mechanism was oxidative wear combined with abrasive wear. Wear rate and friction coefficient decreased with increasing SiC content.

By examining the influence of current density, duty cycle, and pulse frequency on the tribological behavior of pure nickel and nickel–silicon nitride nanocomposite coatings, M. Sajjadnejad et al. (2020) [27] employed a pulsed current electrodeposition method. The results indicated that increasing the current density during electrodeposition was the most critical parameter for reducing the wear coefficient, as reflected in the measured wear rates. Moreover, the incorporation of Si3N4 nanoparticles modified the wear mechanism, shifting it from severe plastic deformation, gouging, and delamination to a more stable plowing-dominated process.

A novel extended Taguchi technique was created by C. R. Raghavendra et al. (2021) [16] to investigate the relationship between specific wear rate and coating process variables. Electrodeposition of Ni-α nano Al2O3 particle onto 6061 aluminum. ANOVA indicates that temperature and particle concentration had the greatest effects on the particular wear rate, contributing 55.07% and 31.94%, respectively. Particle concentration and current density together have a greater effect on the specific wear rate (5.48%), while current density has the least effect (3.46%).

By empirically relating the input parameters (frequency (Hz), duty cycle (%), and peak current density (A/cm2), P. Natarajan et al. (2019) [19] employed the responses to surface method (RSM) to predict the micro-hardness, average surface roughness, specific wear rate, and friction coefficient of pulsed electroplated coatings. To identify the optimal electroplating parameter, grey relational analysis (GRA) was used. It is projected that the optimal parameters of the nano-composite coating will be 10 Hz, 10% duty cycle, and 0.2 A/cm2 peak current density. Furthermore, when compared to other parameters like peak current density and frequency, the duty cycle demonstrated the highest link with the multi-objective optimization of pulsed electrodeposition of composite coatings.

W. Jiang et al. (2019) [28] incorporated a mixture of hard SiC particles and soft PTFE particles into a nickel Watt bath and deposited the resulting composite coating using magnetic jet electrodeposition (JMEP). The JMEP Ni–PTFE/SiC (4 g/L) composite coating exhibited outstanding wear resistance, with the friction coefficient reduced to 0.127 and the wear loss minimized to 0.12 mg, in contrast to the pure nickel coating whose friction coefficient increased to 0.612. This improvement was attributed to the nano-SiC particles, which enhanced the coating’s resistance to deformation by forming a protective outer layer around the nano-PTFE particles. Simultaneously, the PTFE particles improved the lubricity of the composite coating, further contributing to its superior wear performance.

The wear behavior of Ni-TiC composite coatings by pulsed electrodeposition may be predicted by the BP neural network, according to H. Wei et al. (2015) [29] using orthogonal experimental data. The experimental values and the outcomes predicted by the suggested BP model agree quite well. The coefficient of determination is 0.9997, the maximum error is less than 3%, and the relative error is minimal. At a frequency of 600 Hz, a stirring speed of 250 rpm, a pulsed current duty cycle of 50%, a pulsed current density of 1 A/dm2, and a TiC particle concentration of 32 g/L, the optimal plating parameters of the BP neural network were attained.

X. Li et al. coated 45 steel substrates with Ni–TiN composites in 2014 using pulse electrodeposition [20]. An ANN model was used to predict the coatings’ sliding wear resistance through numerical simulations. Using the wear mass loss as the neural network model’s output, the inputs were the bath’s TiN particle concentrations, pulse current density, and pulse current duty ratio. With a density of 4.5 A/dm2 and a service ratio of 30%, the coating shows the least amount of wear mass loss (9.6 mg). When estimating the sliding wear resistance of Ni–TiN nanocomposite coatings, the ANN model’s accuracy is approximately 4.2%.

2. Metal Matrix Composites

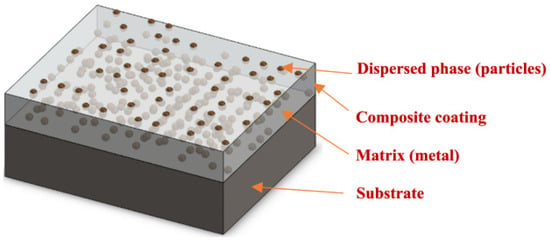

Composite coating is a highly advanced method in materials science that combines two or more phases: a continuous phase, called the matrix, and an integrated, discontinuous reinforcement. These subsequent stages are fused during coating growth or created within the coating (Figure 1) [13]. It is important to remember that the surface coating method produces a surface with appropriate performance while permitting the use of an inexpensive, low-quality substrate, such as corrosion resistance over a wide temperature range, improved mechanical, tribological and physical qualities, tunable surface hydrophobicity and a pleasant appearance [11].

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic illustration of a Composite coating [13].

2.1. Methods for Creating Composites Using Metal Matrix

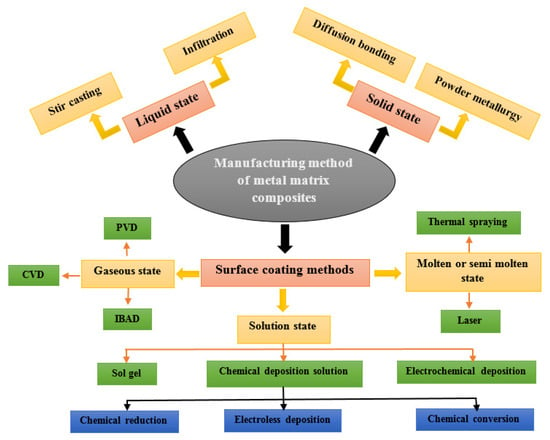

As illustrated in Figure 2, one effective solution is to apply a layer of nanocomposite coatings to the surface of the component, produced through various fabrication techniques. However, the manufacture of thin films cannot be achieved using conventional liquid or solid methods. Processes such as spray forming, spray deposition, and chemical or physical vapor deposition (CVD or PVD) require high operating temperatures. Although these techniques provide high deposition rates and strong coating adhesion, they also generate significant residual stresses, leading to numerous dislocations within the coating’s internal grains. This weakens grain boundaries and slightly reduces corrosion resistance.

Figure 2.

Primary techniques for producing metal matrix composites.

In contrast, electrochemical deposition enables the formation of coatings that chemically bond to the substrate without the need for additional thermal energy during processing. As a result, the produced coatings typically exhibit lower internal stresses and excellent resistance to both corrosion and wear. The incorporation of particles into a nickel matrix through electroplating offers several advantages, including low energy consumption, low cost, high repeatability, and ease of maintenance, ultimately contributing to improved coating performance. Moreover, its remarkable scalability for industrial applications explains its widespread adoption in the production of metallic coatings [30,31,32].

2.2. Electrodeposition of Nanoparticles in a Nickel-Based Matrix

Nickel is widely recognized as an ideal matrix material for composite coatings due to its versatility, hardness, and excellent corrosion resistance. However, despite these advantages, significant challenges remain in adapting such coatings to the stringent demands of high-performance applications, revealing limitations that warrant further investigation.

During electrodeposition, nickel ions dissolved in the electrolyte migrate from the anode to the cathode, where they are reduced to form the metallic deposit. When negatively charged second-phase particles approach the cathode, they adsorb nickel ions and are incorporated into the growing deposit, resulting in the formation of a metal matrix composite (MMC) coating. The characteristics of the final composite can be tailored by adjusting the electrodeposition parameters to control the incorporation rate of the particles, their dispersion within the matrix, and their influence on grain refinement of the metallic microstructure. Additionally, self-lubricating particles may be introduced to reduce wear by imparting intrinsic lubricating properties to the composite coating, thereby decreasing friction and improving tribological performance [11].

The incorporation of nanoparticles such as Al2O3 [17,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], SiC [26,33,44,45,46,47,48], ZrO2 [33,49,50], TiN [20,22,24,51,52], Y2O3 [53,54], TiO2 [55,56], TiCN [57], MoS2 [7,36,58,59,60], TiC [29], Si3N4 [27], ZnO [61], and diamond [60,62,63] into a nickel matrix is intended to improve the mechanical, tribological, and functional performance of the resulting composite coatings. These nanoparticles can significantly modify the properties of electrodeposited nickel via several strengthening and functional mechanisms. Hard ceramic particles (e.g., Al2O3, SiC, ZrO2, TiN, TiC, Si3N4, diamond) increase wear resistance and hardness by hindering dislocation motion, refining the nickel grain structure, and acting as load-bearing reinforcements during sliding. Some oxide particles (e.g., TiO2, ZnO, Y2O3) improve corrosion resistance by increasing coating density and reducing porosity. In addition, lubricating particles such as MoS2 provide a solid-lubricant effect, lowering friction and improving the coating’s tribological stability. Together, these nanoparticles enable the production of nickel-based composite coatings with superior hardness, reduced wear, enhanced corrosion resistance, improved thermal stability, and, in some cases, better lubrication performance compared to pure nickel.

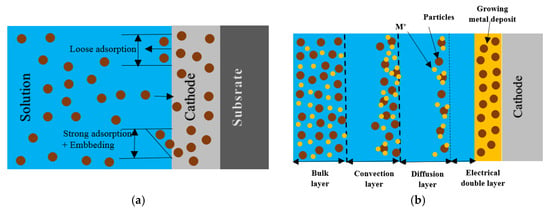

Mechanical agitation and an electric field that depends on many mechanisms capture the particles suspended in the plating solution during the code-position process and retain them in the expanding nickel matrix. The integration of solid particles into the metal matrix during an electro-deposition process is explained by the Guglielmi model [64]. According to this mechanism, the electrodeposition process occurs in two stages. First, the particles are weakly adsorbed on the cathode surface by Van der Waals forces resulting in a high surface coverage, which can be expressed by the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Second, under the effect of the applied electrical field, the particles are strongly adsorbed on the surface by Coulomb forces and incorporated into the growing metal matrix (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Schematic (a) the process of co-deposition according to the Guglielmi model and (b) procedure for co-electrodepositing unsolvable particles into a developing metal matrix to form a metal composite covering.

For the electrodeposition of metal matrix composites, Celis et al. [65] suggested a five-step procedure (see Figure 3b). Vereecken et al. [41] specifically noted that the impact of forces could vary considerably depending on particle size. In their study, the codeposition of 300 nm Al2O3 in the Ni matrix was significantly influenced by the gravitational force, while the codeposition of 50 nm nanoparticles was barely affected by this force. Furthermore, they found that convection and gravitational forces were more important for the transport of micron-sized particles, while convective diffusion dominated the transport of nano-sized particles. Their study also revealed that the entrapment rate of nanoparticles in the expanding composite was influenced by the composite growth rate, which was found to be regulated by the deposition rate.

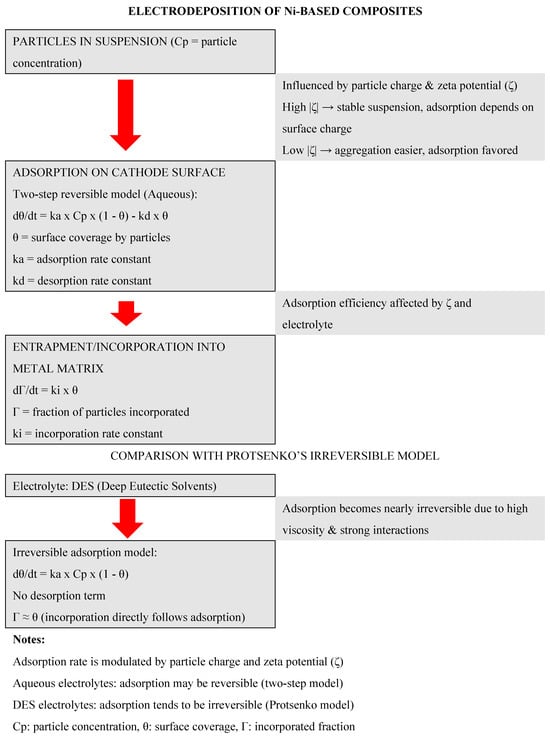

The incorporation of particles into Ni-based composite coatings can be described using mechanistic models that account for adsorption on the cathode surface and subsequent entrapment within the metal matrix. Figure 4 illustrates this process, highlighting the classical two-step reversible adsorption/entrapment model in aqueous electrolytes and the irreversible adsorption model proposed by Protsenko [56] for Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES).

Figure 4.

Mechanistic illustration of particle incorporation in Ni-based composite coatings. In aqueous electrolytes, a two-step reversible model is used: adsorption of particles on the cathode surface (dθ/dt = ka Cp(1 − θ) − kdθ) followed by entrapment/incorporation (dΓ/dt = kiθ). The particle charge and zeta potential (ζ) influence adsorption efficiency. In DES, adsorption tends to be irreversible (Protsenko model: dθ/dt = kaCp(1 − θ)), with direct incorporation into the metal matrix.

The particle charge and zeta potential play a key role in adsorption: particles with high absolute ζ are more stable in suspension, but adsorption depends on the sign of the surface potential. Low |ζ| favors aggregation and adsorption. In aqueous electrolytes, desorption can occur, which justifies the use of a two-step reversible model. In contrast, DES electrolytes exhibit nearly irreversible adsorption due to high viscosity and strong particle–surface interactions, making the Protsenko model more appropriate. This difference affects particle distribution, incorporation efficiency, and ultimately the tribological properties of the coatings.

2.3. Tribology Properties

Tribology is the science and engineering of surfaces in interaction and relative motion, including the study of hardness, wear, lubrication, and friction. Wear can lead to failure when two surfaces slide against each other. The constant removal of surface material reduces the lifespan of industrial equipment and results in significant energy and financial losses. Typically applied as protective films, surface coatings extend the life and reliability of devices by reducing wear and fractures. Optimizing mechanical systems, increasing component life, and improving energy efficiency all depend on tribology. Tribology remains essential to industrial innovation, sustainable development, and technological progress.

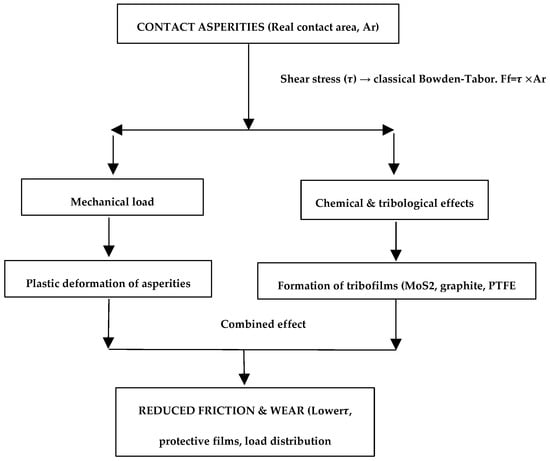

The friction mechanisms in Ni-based composite coatings containing solid lubricants such as MoS2, graphite, and PTFE can be interpreted by combining classical and modern tribological concepts (Figure 5). According to the Bowden–Tabor model, friction is proportional to the shear strength (τ) at the interface and the real contact area (Ar). In addition, multi-physics effects significantly influence friction behavior. Mechanical loading induces plastic deformation of surface asperities, dynamically altering the real contact area. Concurrently, tribochemical interactions lead to the formation of thin lubricant films (MoS2, graphite, PTFE) at the sliding interface, which reduce the effective shear strength and provide a protective layer against wear. The integrated effect of mechanical deformation and tribofilm formation results in a significant reduction in friction and enhanced coating durability. This framework bridges classical friction theory with modern understanding, explaining the superior tribological performance of Ni-based composite coatings with solid lubricants.

Figure 5.

Mechanistic representation of friction in Ni-based composite coatings: integration of Bowden–Tabor shear-based friction, mechanical deformation of asperities, and tribofilm formation by MoS2, graphite, and PTFE.

2.3.1. Micro-Hardness and Nano-Hardness

A quick way to define hardness is to think of it as a measure of a material’s toughness. Stiffness, yield strength, and other material characteristics are often confused with hardness. More specifically, hardness measures a material’s ability to resist local plastic deformation. For testing electrodeposited thin films, Vickers and Knoop micro indentations are often the two most common techniques. Thus, pressure units are used to express hardness (Equation (1)). Oliver and Pharr provided the most popular data analysis technique [66]. Because the shape of the curve determines the depth of the depression, the hardness can be determined without measuring the indentation. It also determines the material’s modulus of elasticity.

Its internal structure and its interaction with the indenter determine the material’s hardness, which is a complex and ill-defined attribute. One of the simplest ideas to apply to composites is the rule of mixtures (ROM). The lower and upper bounds of such an estimate can therefore be determined using the two models that are available in the literature [67]: iso-stress (Equation (2)) and iso-strain (Equation (3)).

The Hall-Petch effect, also referred to as the grain boundary strengthening effect, is the most significant of them. It is still the primary method for maximizing the hardness of co-deposited layers, especially in nickel. New developments in bath composition, additives, and pulsed electrodeposition are opening the door to “tailor-made” microstructures, which will fully utilize this effect while minimizing its drawbacks at extremely small scales [68]. Grain size and hardness are related, as explained by the Hall-Petch effect:

The finite element produces a very basic model when a single particle is added to the matrix [69]. The molecular dynamics method uses a lot of particles to create a model, either in accordance with the reference sample’s structure [70] or randomly distributed [71]. Since computers’ processing power has increased, molecular dynamics has also gained popularity as a simulation technique. It reveals the atomic level of fundamental mechanics [72].

By altering contact mechanics and measurement accuracy, the increase in surface roughness induced by the addition of nanoparticles complicates indentation tests. This highlights the importance of considering surface topography when characterizing materials, particularly for nanostructured coatings. Ignoring this factor can lead to erroneous assumptions regarding the mechanical characteristics of even very promising materials.

2.3.2. Wear Resistance

Wear is the term used to describe the removal of material from surfaces in relative motion. Wear resistance is significantly increased when particles are added to a metallic matrix. Microstructural changes, including morphology modification, choice of volume fraction, size and type of reinforcement particles, and the type of bonding between the reinforcement and the matrix, can significantly alter wear resistance.

- Abrasion, oxidation, and adhesion are the three wear mechanisms that these systems often display, depending on the component materials, applied force, and sliding distance [11,15].

- Oxidation (corrosion) of friction surfaces can accelerate wear. High temperatures and the friction-induced loss of protective oxide layers from the surface speed up this process. Friction continuously removes the oxide deposit, preventing new oxide from forming. Hard oxide particles trapped by sliding/rolling surfaces after removal also enhance three-body abrasive wear.

It should be mentioned that wear is typically calculated using the volumetric wear factor (CW), which has the following definition:

Since wear is measured using a variety of configurations and, in certain situations, wear determines other parameters (such as mass loss or wear trace depth), comparing various items is generally challenging and prone to considerable inaccuracies. Additionally, it is commonly believed that wear is explained by Archard’s law, which states that the wear rate is inversely proportional to hardness and relies linearly on the sliding distance and applied stress. However, this is not necessarily the case for PRMMCs [15].

2.3.3. Friction

When two surfaces come into contact, friction acts as a tangential resistive force that tends to produce relative motion. Friction is not an intrinsic property since it depends on several factors, including the presence of lubricants, the testing environment, the physical and chemical characteristics of the materials and surface, and the testing and contact conditions. Equation (6) provides the CoF, a dimensionless scalar number.

According to the Bowden–Tabor friction model (1964), as cited in [15], the force required to shear the adhering junctions (Fa) and provide the strain energy (Fd) equals the total frictional force (F).

The Bowden and Tabor mechanism is the main basis of the dry friction mechanism in MMCs. The metal matrix can avoid plastic deformation due to its reinforcing particles. However, the particles torn from the matrix can create a third body, which increases plowing and, consequently, friction [73].

The tribological properties of composites with a solid lubricant reinforcement, like the Ni/MoS2 coating, are generally better. The MoS2 particles provide a thick layer of lubricant coating during friction. MoS2 buildup in wear fissures may be the cause of this. Excellent tribological characteristics, including a low CoF and a low wear factor, are noted in this coating; the lubricant layer sticks to the coated surface [36,58].

Equation (6) is typically used to determine the CoF without making a distinction between adhesion and deformation factors. Additionally, the material, mechanical, and physical aspects of MMC on the CoF can be investigated using statistical models.

3. Parameters Affecting the Tribology Property

When nanoparticles are co-deposited in a metal matrix, nickel, electrolyte composition, and experimental conditions are critical factors. It can be difficult to get a clear picture of how experimental parameters affect things.

3.1. Particle-Related Parameters

The integration of nanoparticles into electrodeposition baths offers a promising avenue for the manufacture of coatings with improved properties adapted to specific applications, by modifying the morphology, microstructure and performance of the deposits obtained. Moreover, the inclusion of hard particles to the metal matrix improves wear resistance by boosting grain dispersion and refining resistance, changing the direction of grain growth to tighter directions, and increasing the ductility of the metal matrix in the contact zone. Better anti-abrasive effect is demonstrated by the lubricating particles’ non-stickiness.

3.1.1. Type of Nanoparticle

MoS2 particles are more effectively absorbed into the Ni matrix than graphite particles, according to D. Trabelsi et al. [7]. This is mainly because of their smaller size (<2 μm), which confers increased reactivity compared to the larger graphite particles (7–11 μm). In comparison to pure nickel, the microhardness is increased when MoS2 particles are added, but the hardness is somewhat reduced when graphite particles are added. However, graphite-containing coatings show better wear resistance and lubricating qualities, emphasizing the trade-off between tribological performance and hardness. Ni-Al2O3 composite coatings outperformed other composite coatings in terms of hardness and wear resistance for all electrodeposition scenarios (DC, PC, or PRC). With a hardness of roughly 2243 HV, SiC particles are notably more resilient than ZrO2 particles (approximately 1326 HV) and Al2O3 particles (about 1530 HV). The much greater content of Ni-Al2O3 for each deposition condition seems to be the reason for the significantly higher content of Al2O3 (in Ni-Al2O3) compared to SiC (in Ni-SiC) and ZrO2 (in Ni-ZrO2) [33].

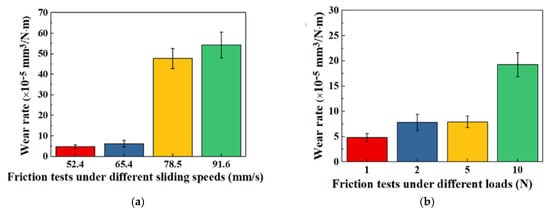

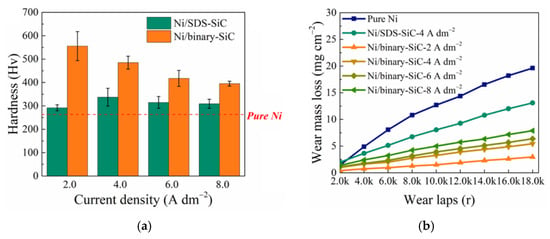

Y. Wang et al. [74] investigated the tribological properties and durability of mold inserts. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), tungsten disulfide (WS2), and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) nanoparticles were utilized to electroform nickel-based composite mold inserts. Ni-WS2 mold inserts demonstrated the best lubrication and wear resistance, followed by Ni-PTFE and Ni-MoS2 inserts. While the lowest friction coefficient against the Si3N4 ball decreased to 0.25, the maximum micro-hardness of Ni-WS2 mold inserts improved from 278.2 HV for pure Ni to 456.0 HV, an increase of 1.64 times. Self-lubrication and wear resistance were affected more by increasing sliding speed than by external load. The wear rate roughly tenfold increased when the sliding speed was above 65.4 mm/s (Figure 6a). High tangential friction and high normal pressure resulted in rapid wear of the composite mold inserts and loss of their self-lubricating qualities when the maximum sliding speed and load were exceeded. As the applied load increased from 1 N to 10 N, the wear rate gradually increased. It was possible to maintain the self-lubricating qualities of the Ni-WS2 mold inserts while reducing their wear rate when the external load was less than 10 N. Under a 10 N load, the wear rate increased significantly, although it was still lower than that of pure Ni (Figure 6b). Nevertheless, the increase in sliding speed had a greater impact on self-lubrication than the external stress.

Figure 6.

(a) Rate of wear of the Ni-WS2 mold insert at varying sliding speeds and (b) different loads [74].

Both Ni-SiC and Ni-Dual composites showed better wear resistance and greater hardness values than pure Ni and Ni-Graphite, as shown in Table 1. Tribological tests were carried out with a disc tribometer (NanoTest™ Vantage) under a load of 1 N and a sliding distance of 1.32 m. The reliability of the calibration, the rigor of the protocols and the stability of the instrument ensure measurements conforming to the ISO 14577-1:2015; Metallic materials—Instrumented indentation test for hardness and materials parameters—Part 1: Test method. Publisher: International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015). The co-deposition of SiC was unaffected by graphite’s presence in the SiC: Graphite powder mixture, and the composites’ performance was not enhanced by any other advantages such self-lubrication. There was no synergy between the powders because the Ni-SiC and Ni-Dual composites showed comparable co-deposition, average grain sizes, hardness, and wear volume [75].

Table 1.

Lists the mechanical and tribological characteristics of a Ni composite coating that contains graphite and SiC particles [75].

The type of nanoparticles incorporated into a composite coating strongly influences its mechanical and tribological properties. Hard nanoparticles improve the coating’s microhardness and rigidity through dispersion hardening, grain refinement, and dislocation blocking, while reducing abrasive and adhesive wear [33]. Solid lubricating nanoparticles decrease the coefficient of friction by forming a tribological film at the contact surface [74]. Good matrix–particle adhesion is essential to prevent defects. Combining hard and lubricating nanoparticles provides an optimal balance between mechanical strength, wear resistance, and low friction [7,75].

Hard ceramic particles such as Al2O3 and SiC consistently improve microhardness and wear resistance through grain refinement and reinforcement. Conversely, lubricating particles such as MoS2, WS2, and PTFE reduce friction and enhance self-lubrication. A trade-off exists between hardness and lubrication: coatings containing MoS2 or PTFE exhibit lower hardness but superior tribological stability, while Ni-Al2O3 or Ni-SiC coatings offer maximum hardness at the cost of reduced lubrication. Performance is also heavily influenced by operating conditions, such as sliding speed and applied load, highlighting the importance of optimizing both the choice of nanoparticles and the deposition parameters for specific applications. These trends allow for a more systematic understanding of the effect of different types of nanoparticles on the mechanical and tribological behavior of nickel matrix composite coatings.

3.1.2. Particle Size

Studies comparing the effect of particle size on wear show that coatings reinforced with nanoparticles generally exhibit lower wear rates than those containing microparticles [15]. The work of Zhang et al. [24] studied, using magnetically assisted pulsed electrodeposition (MAPE), the effect of TiN nanoparticle size on the tribological and mechanical properties of Ni–TiN thin coatings. A wear tester (MM63B) was used to examine the wear behavior of the deposited coatings. The pair consisted of a steel ball with a surface hardness of HRC 60. 150 rpm was the sliding speed maintained when the load was 90 N. The Table 2 shows that particle size strongly influences micro hardness and wear. Coatings made with finer nanoparticles exhibit a more compact and uniform microstructure, leading to high micro hardness and shallow indentation depths, while size variations significantly affect mass loss due to wear. Furthermore, it is noted that the use of nanoparticles shifts the minimum wear rate towards higher particle concentrations (see Section 3.1.3). Although small particles are more easily co-deposited and strongly influence the concentration in coatings, their direct effect on improving wear resistance sometimes remains ambiguous depending on the studies [15].

Table 2.

Effect of Ni-TiN composite coatings’ particle size on their hardness, indentation depth, and wear rate.

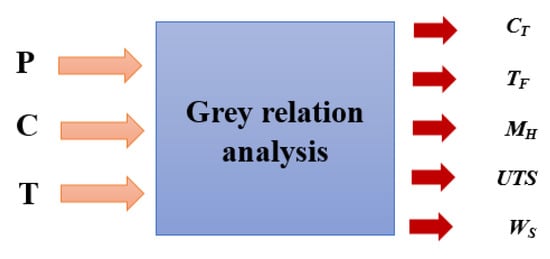

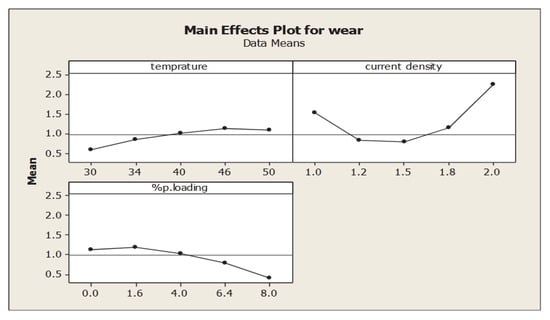

3.1.3. Nanoparticle Concentration in the Bath

The addition of nanoparticles increased the electrolytic matrix’s rate of deposition and the processing current’s efficiency. The composites’ microhardness values were noticeably higher than those of nickel coatings [61]. Furthermore, an ANOVA revealed that the addition of Al2O3 particles to the nickel matrix strengthened the coating’s adherence to the substance [18]. Ni-MoS2 composite coatings’ coefficient of friction dropped from 0.35 to 0.08 as the bath’s MoS2 concentration rose [59]. The nickel matrix’s increased MoS2 particle concentration is the cause of this impact. Adding more MoS2 particles to the coating reduced the friction coefficient because they are self-lubricating, according to Trabelsi et al. [7]. The electrodeposition of TiCN nanoparticles in a Ni matrix with bath pH (2 and 5), current densities (2 and 10 A.dm−2), TiCN particle concentrations (2 and 15 g·L−1), and bath temperature range (30 and 70 °C) was reported in a work by G.N.K. Ramesh Bapu et al. [57]. The durability and wear resistance of the nanocomposite deposit have increased with the volume percentage of TiCN in the deposit composite, at a rate of about 23.9 vol. %. The composite dispersions’ hardening effect and the modification of the nickel crystallite’s grain size and structure both contribute to the composite coating’s increased hardness. Using RSM based on Grey relation analysis (Figure 7), C. R. Raghavendra et al. [18] optimized the coating parameters of Ni-Al2O3 composite coating, such as temperature (T1), current density (C2), and percentage of particle loading (P3), in order to achieve maximum coating thickness (CT), adhesion strength (TF), micro-hardness (MH), maximum tensile strength (UTS), and minimum wear rate (WS). The link between process parameters and coating wear is represented by Equation (9), which provides the coding model of coating wear using RSM.

Figure 7.

Prediction system.

The ANOVA clearly shows that the linear particle loading in the bath (P) has the greatest effect on the wear rate of 41.48%. The 3D surface plots show that wear resistance increases as the particle loading in the composite coating increases. The best specific wear is obtained at low current density and low temperature with a reasonable particle loading of 3 g/L. The minimum value of 0.0918 mm3/N-m of specific wear rate is obtained for temperature, current density and particle loading of 34 °C, 1.2 A/dm2 and 4.8 g/L, respectively. The highest specific wear rate value obtained is 0.6210 mm3/N-m with corresponding values of 46 °C, 1.8 A/dm2 and 4.8 g/L, respectively. The ideal parameters for improved composite coating performance, as indicated by the Grey’s relation shade, are temperature (34 °C), current density (1 A/dm2), and particle loading percentage (1.2 g/L) [18].

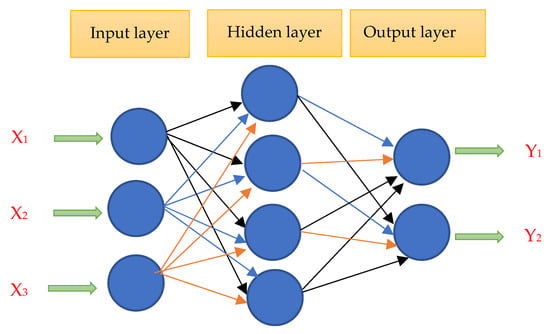

A computer-controlled MM200 ring-on-block tester was used by X. Li and colleagues [20] to estimate the sliding wear resistance of Ni–TiN coatings using artificial neural networks (ANNs) (Figure 8). Rotating the lower specimen, which was composed of Si3N4 ceramic rings, at 180 rpm produced a relative sliding velocity of 0.4 m/s. The Ni–TiN composite coatings were shattered after being affixed to the specimen holder when 200 N of force was applied. The test covered a total sliding distance of 2000 m. Wear mass loss (Mw) was intended to be the neural network model’s output, while the bath concentrations of TiN particles (Cp), pulse current density (Di), and pulse current duty cycle (Ro) were intended to be its inputs. At a duty cycle of 30%, a current density of 4.5 A/dm2, and an 8 g/L concentration of TiN particles, the Ni–TiN coatings with the least amount of weight loss exhibit these characteristics. The results of the experiment agree with the predicted values. The ANN model, which has an error of about 4.2%, can effectively predict the slip wear resistance of Ni–TiN nanocomposite coatings. Similarly, Wei et al. [29] used pulsed electrodeposition to create Ni-TiC composite coatings and identified the ideal parameters (i.e., duty cycle, current density, frequency, stirring speed, and TiC particle concentration). They showed a remarkable level of agreement between the experimental data and the outcomes predicted by the proposed BP model, with a maximum relative error of less than 3% and a coefficient of determination of 0.9997. At a frequency of 600 Hz, a stirring speed of 250 rpm, a pulsed current density of 1 A/dm2, a pulsed current duty cycle of 50%, and a TiC particle concentration of 32 g/L, the optimal plating parameters of the BP neural network were attained.

Figure 8.

An illustration of the ANN’s configuration.

The ideal composition of a nanocomposite coating (Ni-W10 g/L Y2O3) with a low friction coefficient and wear rate was identified by Xing et al. [53]. The proper addition of Y2O3 nanoparticles and the resulting increase in hardness from refined crystalline strengthening were the primary factors linked to the composite coating’s improved wear resistance. Y2O3 nanoparticles were taken out of the matrix to take part in the rolling friction process during the friction test. The wear track’s width and depth gradually decreased as the concentration of nanoparticles increased, indicating that the composite coating’s resistance to wear was enhanced. They demonstrated that the wear rate and friction coefficient of the produced coatings increase when the Y2O3 concentration is raised over this ideal level. This was explained by the fact that when there were too many Y2O3 nanoparticles present, a projecting grain formed, increasing the composite coating’s surface roughness. Xing et al. [53] pinpointed the optimal composition of a nanocomposite coating (Ni-W10 g/L Y2O3) with a low wear rate and friction coefficient. The proper addition of Y2O3 nanoparticles and the increased hardness brought about by refined crystalline strengthening were the primary factors linked to the composite coating’s improved wear resistance. L. Tian et al. [54] have demonstrated that code-posited Y2O3 particles minimize weight loss while lowering the friction coefficient. Ni–Y2O3 composite coatings reach their optimal microhardness and tribological characteristics at 4.4 weight percent Y2O3. Table 3 shows that increasing the concentration of diamond particles in the electrolyte improves the wear resistance of the coatings by reducing the coefficient of friction and wear loss. The wear mechanism is mixed (abrasive and adhesive) due to the adaptive effect of the co-deposited diamond particles [76].

Table 3.

Worn scratch profile information and CoF of Ni-diamond with increasing concentrations of diamond particles [76].

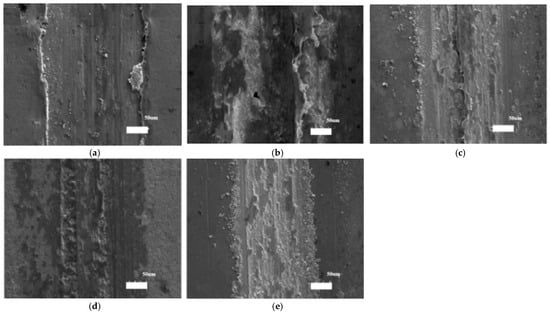

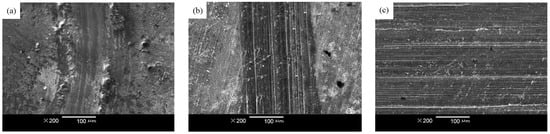

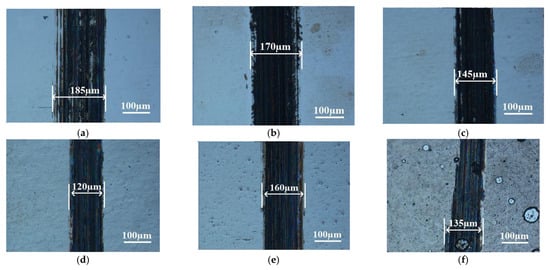

The SEM morphologies of the coatings’ worn scratches are shown in Figure 9 to further illuminate the coatings’ wear behaviors. All of the coatings have evident furrows in their worn scratches, which suggests that the coatings wear abrasively. Additionally, there was some avulsion at the side and inside the scratches, which suggests sticky wear behavior. In particular, the avulsion happened along the side of the coatings’ scratches made at 1 and 4 g/L, which caused the coatings’ scratch profiles. In the meantime, CoF fluctuated due to the coatings’ varied wear behaviors.

Figure 9.

SEM morphologies of the worn scratches of the Ni–diamond coatings prepared at (a) 1, (b) 2, (c) 4, (d) 8, and (e) 16 g/L [76].

3.1.4. Combination of Particles

An advanced technique in composite material design is a combinatorial particle-reinforced nickel matrix, which takes advantage of the composition and complexity of the reinforcing particles to enhance the performance of the nickel matrix and possibly provide it with multiple uses [23,75,76,77]. An overall lower and more stable coefficient of friction could result from the mixture of lubricating particles such as graphite or molybdenum disulfide that promote sliding and hard particles (such as carbides or nitrides) that maintain the load. In general, wear can occur in several ways, including abrasion, adhesion, fatigue, and corrosion. A more durable coating can be achieved under various stresses by adding particles that are resistant to various forms of wear. Hard particles, for example, can resist abrasion, while self-lubricating particles can reduce adhesive wear. Third-body wear debris can be abrasive. Overall wear can be reduced by adding particles that promote the disintegration of this material into finer, less aggressive particles.

In a modified Watts nickel-plating bath, M. Masoudi et al. [78] co-electrodeposited SiC into a Ni–Al2O3 MMC coating. The microhardness of recently created hybrid MMC films was 2.6 times that of Ni films and 30% greater than that of Ni–Al2O3 nanocomposite coatings. It was discovered that the wear resistance of Ni–Al2O3–SiC MMC films was 75% greater than that of Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings and almost four times greater than that of pure nickel. S. K. Singh et al. [77] checked the structure, composition, morphology, microhardness, wear resistance, and water contact angle measurements of Ni-SiC-GO composite coatings made by PC electroplating. Data showed that when GO was introduced to the Ni-SiC composite matrix, the water contact angle dropped from 69.2° to 58.9°, indicating that Ni–SiC-GO is hydrophilic due to its polar oxygen functions. According to the microhardness measurements, the Ni–SiC coating had a hardness of around 958.5 HV and an elastic modulus of about 140 GPa. However, the insertion of carbonaceous particles resulted in a high elastic modulus of 158 GPa. After inserting the embedded GO particles, the Ni–SiC-GO coating’s hardness dropped to about 785.2 HV. GO lubricating particles, however, increased the friction behavior of the resulting Ni–SiC–GO composite coating.

Ni-Al2O3-PTFE composites were found to have an average friction coefficient of 0.09 and a surface roughness of 42 nm, respectively, after Y. Li et al. [23] manufactured the coating via jet electrodeposition. The resultants displays that these values are much lower than those of Ni-PTEF and Ni-Al2O3 nanocomposite coatings. Additionally, the researchers discovered that the introduction of Al2O3 and PTFE nanoparticles at 40 and 10 mL/L produced the maximum deposition rate and microhardness, 63.13 μm/h and 886 HV, respectively, as well as the highest elastic recovery ratio (he/hmax) of 0.46. The findings show that the Ni-Al2O3-PTFE nanocomposite coating exhibits remarkable durability and resistance to wear in these conditions. The combination of solid lubricants and hard carbides as a reinforcing particle mixture in a nickel-based matrix was investigated by S. Pinate et al. [79]. Microhardness measurements (NanoTestTM Vantage) were performed using a Vickers indenter according to ASTM E384 (ASTM E384-22; Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials. Publisher: ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022), with a 100 m load applied for 10 s. The tribological tests were performed in dry condition using a pin-on-disk test (NanoTestTM Vantage) with a load of 1 N and a sliding distance of 1.32 m in accordance with ASTM G99 (ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. Publisher: ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.). Surface roughness was measured using a surface profilometer (Surtronic® S-100 Taylor Hobson®), and Ra was expressed as the average value of eight different measurements over a length of 1 mm, which conforms to ISO 4287/4288 (ISO 4287:1997; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface texture: Profile method — Terms, definitions and surface texture parameters. Publisher: International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.). Table 4 presents their results. Grain refinement by particle co-deposition and hardening by SiC inclusion strengthened these deposits, which had higher hardness values (about 448 HV) than pure nickel deposits (around 270 HV). The volumetric wear rate of Ni-SiC decreased due to this increase in hardness, halving the values recorded for pure nickel. The nickel matrix developed nano-crystallinity following the addition of MoS2 particles, which produced greater grain refinement than SiC. Although the softer MoS2 particles had a softening impact, Ni-MoS2’s microhardness (about 446 HV) was comparable to that of Ni-SiC because to its finer microstructure. Furthermore, by ensuring that the deposits would lubricate themselves, these particles reduced the friction coefficient from around 0.15 for pure Ni to about 0.06. Because of its high hardness and smooth sliding, the wear rate was lower (about 5 × 10−4 mm3 Nm−1) than that of Ni (approximately 62 × 10−4 mm3 Nm−1) and Ni-SiC. In addition, adding nanoparticles increased nickel’s previously decreased Young’s modulus (Er).

Table 4.

Pure nickel, Ni-SiC, Ni-MoS2, and Ni-SiC-MoS2 composites’ average grain area, arithmetic mean roughness, microhardness, decreased Young’s modulus, coefficient of friction, and volumetric wear factor [79].

Therefore, it can be said that hard ceramic particles such as Al2O3 and SiC significantly improve microhardness and wear resistance through grain refinement and their charge-carrying effect. Simultaneously, lubricating particles such as MoS2, WS2, PTFE, or GO reduce friction and promote self-lubrication of the coatings. Combinatorial systems, integrating both hard and lubricating particles, allow for an optimal compromise between hardness and tribological performance. The performance variations observed in different studies also depend on electrodeposition parameters, such as current density, bath composition, agitation, and temperature, which control particle incorporation and the final coating microstructure. These trends demonstrate the potential of nickel matrix composite coatings reinforced with nanoparticles to tailor mechanical and tribological properties to specific applications.

3.2. Parameters Related to Deposition Energy

Current density is the amount of current per unit area of the electrode. In electrodeposition, it plays a crucial role in determining the deposition rate, microstructure, and nanoparticle incorporation. In pulsed plating, the supplied current density consists of two parts: (1) a faradaic current, which regulates the rate of metal deposition; and (2) a capacitive current, which charges the double layer. Kariapper et al. [80] claim that the stirring speed determines the location of a maximum in the integration rate vs. current density graphs. The rise in the incorporation rate, consistent with Guglielmi’s two-step method, is caused by the nanoparticles’ increasing tendency to reach the cathode surface [64]. In these circumstances, particle deposition predominates and nanoparticle adsorption governs the codeposition process [81].

3.2.1. Effect of Average Current Density

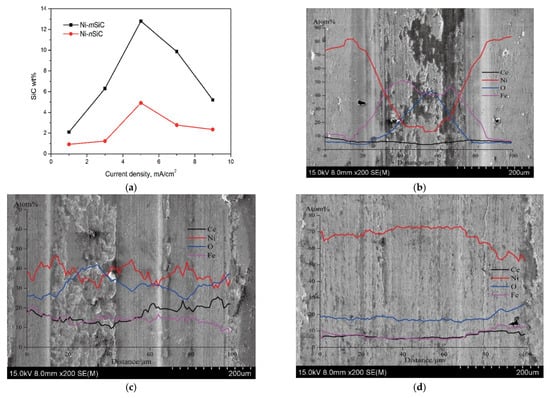

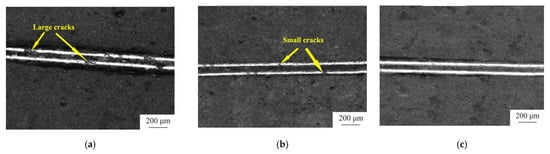

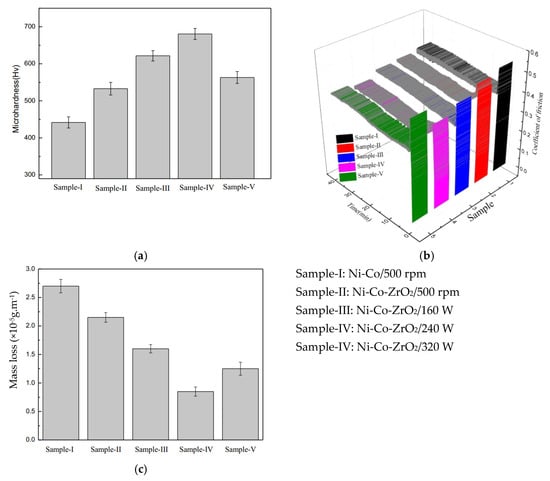

- Direct Current (DC): Figure 10a illustrates the correlation between the coatings’ current density and the micro- and nanoscale SiC concentrations. At lower current densities, the rate of Ni (II) reduction is slower, giving inert particles ample time to adhere to the electrode surface and become part of the Ni matrix. As current density increases, the SiC content of the coatings decreases because fewer particles may be absorbed into the Ni matrix due to inert particle adsorption, which happens far more slowly than the Ni (II) reduction rate [82]. R.K. Saha et al. demonstrated the same outcome [43]. In the coatings, the mass fraction of Al2O3 particles first increased with current density before peaking at 4.3 weight percent at 0.01 A/cm2. The concentration of particles that were co-deposited did not vary as the current density increased. With a maximum current efficiency of 0.01 A/cm2, more reinforced particles were created by the electrodeposition process. Ni–ZnO composites were discovered to have a nodular shape. Low current densities resulted in compact and smooth Ni–ZnO coatings. As the current density increased, the coatings’ surface became more imperfect and punctured [61]. Using a vertical magnetic field and jet electrodeposition technique, R. An-hua et al. [25] created a Ni-CeO2 nanocomposite coating on a 45# steel substrate. Even though the coatings contained 10–33% mass percentages of MoS2 particles, the composite coating demonstrated a maximum microhardness value of 665.78 HV0.1 at a current density of 20 A/dm2. The hardness, however, dropped from around 650 to 435 after the formation of Ni-MoS2 nanostructures when the current density was raised from 3 to 7 A/dm2. Throughout the treatment, current densities of 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 A/dm2 were employed, and each component had to be plated for 25 min. The ideal current density for the codeposition of nickel-MoS2 nanostructured composite coatings with a lovely look and advantageous tribological performances was therefore determined to be 5 A/dm2 [59]. Moreover, Figure 10b–f displays the composite coating’s surface look as seen under an electron microscope following 20 min of ball mill polishing. According to the findings, wear scars on the composite coating surface first shrank in width, depth, and cross-sectional area before growing as the current density rose. At low current densities, it was thinner, and the composite covering’s hardness value was lower. Significant adhesive wear caused the covering to deteriorate; mild oxidative and abrasive wear coincided with the rise in current density. When the composite coating’s current density was raised by 20 A/dm2, coating surface attrition decreased. [25].

Figure 10. (a) Particle concentration’s impact on the micro or nanosized SiC content of the composite coatings; surface morphologies of wear marks in the coating prepared at current densities of: (b) 10 A/dm2, (c) 15 A/dm2, (d) 20 A/dm2, (e) 25 A/dm2, (f) 30 A/dm2 [25].

Figure 10. (a) Particle concentration’s impact on the micro or nanosized SiC content of the composite coatings; surface morphologies of wear marks in the coating prepared at current densities of: (b) 10 A/dm2, (c) 15 A/dm2, (d) 20 A/dm2, (e) 25 A/dm2, (f) 30 A/dm2 [25]. - Pulsed current (PS): In pulsed current electrodeposition, a cathodic current is applied for a predetermined time (Ton) and then interrupted for a predetermined time (Toff). Higher average current densities (ia) can be used for the electrodeposition procedure since the pulsing of the current inhibits dendritic development [27]. Due to their uniform particle distribution and higher alumina content, Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings produced by pulsed current exhibit better wear characteristics than those deposited by direct current. The higher density of (002) planes is what gives nickel-based coatings their enhanced ductility and growth in the [83] direction, as well as boosting their capacity to absorb plastic deformation energy and inhibiting the development of microcracks. Additionally, the nickel matrix’s greater grain size is thought to be advantageous. Better wear characteristics result from higher Al2O3 concentration combined with high. However, for nanocomposites made with pulsed current, the wear rate does not change much as the number of particles with current density increases. This is explained by the coating’s higher particle count, which reduces its plastic deformation property and causes failure by creating microcracks [42]. The impact of pulsed current density on micro-hardness, wear characteristics, relative texture coefficient and microstructure of Ni-TiN was examined by F. Xia et al. [51]. A Ra value of 29.57 nm indicates that the Ni-TiN coating produced at 60 mA/cm2 had the most compact and smooth surface morphology of all the coatings. The coating created at 60 mA/cm2, however, has the lowest friction coefficient, wear loss, and greatest micro-hardness value.

3.2.2. Current Type

In both PC and PRC electro-deposition methods, the current can frequently oscillate between two levels. Zero current (for PC) or reverse current (for PRC) effectively discharges the electric double layer that forms around the cathode, accelerating deposition rates and enhancing ion penetration to the cathode. Furthermore, improved ion dispersion in the electrolyte and higher-quality coatings are made possible by reverse current (for PRC) or zero current (for PC) [22,33].

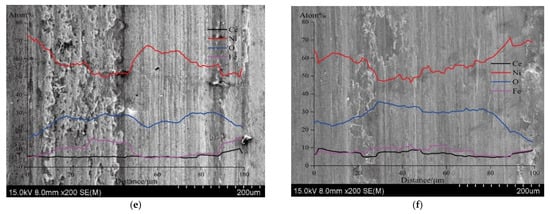

The coating was subjected to microhardness testing by C. Ma et al. [22] using an HXD-1000 microhardness tester (Shanghai Optical Instrument Factory Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) under a load of 0.98 N for 4 s, with an average calculated across five points in accordance with ASTM E384. Using a CSM scratch tester in accordance with ISO 20502 (Fine ceramics (advanced ceramics, advanced technical ceramics)—Determination of adhesion of ceramic coatings by scratch testing. Publisher: International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2016), coating adhesion was assessed using a progressive load scratch test (10–50 N). In accordance with ISO 20808 (Fine ceramics (advanced ceramics, advanced technical ceramics)—Determination of adhesion of ceramic coatings by scratch testing. Publisher: International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2017), friction and wear tests were conducted using an MW-1A machine under dry friction circumstances with a load of 50 N at 300 rpm for 20 min.

According to Table 5, the adhesion (1047.1 MPa) and microhardness (490.4 HV) of positive-negative pulse electrodeposited Ni-TiN coatings are superior to those of PC and DC electrodeposited coatings. Positive-negative pulse electrodeposited coatings are a great option for overall performance because of their exceptional tribological properties and resilience to wear [22]. The SEM micrographs of the scratches on the surfaces of the Ni-TiN coating coated at various current modes are shown in Figure 11. Significant cracks appear in the scratches of the coating applied by direct current electroplating when subjected to a 25 N stress. The coating scratches from positive pulse current electroplating develop tiny cracks when subjected to a 40 N pressure. Surprisingly, the coating from positive–negative pulse current electroplating does not shatter under a 50 N load, and the scratches stay consistent [22].

Table 5.

Effect of current type on micro-hardness, wear loss and friction coefficient of Ni-TiN composite [22].

Figure 11.

SEM scratches on the surfaces of Ni-TiN coating deposited at different current modes: (a) DC, (b) PC, and (c) PNPC [22].

During direct current electrolytic deposition, the depletion of nickel ions near the cathode promotes hydrogen evolution reactions, leading to a local increase in pH and the formation of compounds trapped within the coating, which degrades its adhesion. In positive pulsed current, the interruption of the pulses allows for the partial regeneration of nickel ions, limiting hydrogen evolution and improving adhesion. Positive-negative pulsed current deposition further enhances this effect, as the negative pulse dissolves micro-protrusions and increases the local concentration of nickel and nano-TiN ions, thus more effectively suppressing hydrogen evolution and providing the best adhesion among the modes studied [22].

Ni-SiC and Ni-ZrO2 coatings, as well as pure Ni and Ni-Al2O3, were electrodeposited by direct current (DC), pulsed current (PC), and pulsed current (PRC) (T. Borkar et al. [33]). The researchers used the ball-and-disk method to compare the wear resistance of the nanocomposite coatings (20 N load, 200 rpm sliding speed, 4 mm track diameter, and 753.6 m total sliding distance). They found that the PC- and PRC-deposited coatings exhibited less mass loss than those obtained by DC electrodeposition. The advantages of DC and PC deposition techniques can be demonstrated by comparison. This comparison is made possible by another study by Gül et al. [42]. In addition to increasing the volume percentage of particles in the composite, which can reach 40% at higher current densities, switching to PC also improved hardness by approximately 5%. Conversely, DC plating resulted in slightly greater crystal lattice distortion and a 5% reduction in grain size. Furthermore, the wear rate of DC-plated nanocomposites increased with sliding speed. The wear rate of PC-plated materials and the coefficient of friction, for both DC- and PC-plated materials, were significantly reduced by increasing sliding speed, unlike the DC-plated nanocomposites [42].

3.2.3. Pulse Frequency

The system under study (metal/nanoparticle matrix, nanoparticle type, electrolyte) determines the ideal pulse frequency. To optimize the trade-off between microstructure, nanoparticle incorporation, and target properties, modeling (e.g., kinetic deposition analysis) and experimentation are often necessary. The duration of the activation and deactivation phases is determined by the frequency of these pulses. Shorter activation periods and shorter pulses are associated with higher frequencies [37]. Equation (11) shows that the pulse frequency is equal to the inverse of the cycle period (T).

The wear behavior of Ni-Al2O3 composite coatings as a function of pulse frequency shows significant variations between dry sliding wear and oil lubrication wear [37]. Under dry sliding wear circumstances, the wear resistance unexpectedly dropped as the pulse frequency increased. Because of the nickel matrix’s structure, which showed erratic orientation and considerable adhesive wear during the wear process, Ni-Al2O3 coatings with a high volumetric proportion of alumina particles had poor wear resistance. Under oil-lubricated wear circumstances, the volumetric amount of reinforcements rose in tandem with the coatings’ wear resistance because lubricating oil could stop adhesive wear. Thus, the volume fraction of alumina particles was the main element influencing the anti-wear efficiency of composite coatings, not the roughness of the powder.

H. Liu et al. investigated the effects of duty cycle and pulse frequency on morphology, structure, wear, and corrosion behavior [82]. SiC nanoparticles were widely dispersed and abundant in Ni grains with a duty cycle of 20% and a pulse frequency of 50 Hz. This also had an impact on the amount of SiC nanoparticles in the Ni matrix. In addition, these values exhibited the highest microhardness value (equal to 911.9 HV) and excellent wear resistance (equal to 18.1 mg). Higher contents of SiC nanoparticles embedded in NCs led to the detachment of a large number of SiC nanoparticles from the Ni matrices, forming large amounts of rolling grains during wear tests. This result could effectively hinder the growth of abrasive grooves, resulting in excellent wear resistance (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

SEM images of the worn surface of prefabricated Ni-SiC with different pulse frequencies: (a) 10 Hz, (b) 25 Hz, and (c) 50 Hz [82].

3.2.4. Duty Cycle

There is a relationship between the addition of nanoparticles and the duty cycle. The effects of the duty cycle on the incorporation rate can be explained as follows:

- A longer dwell time (i.e., a lower duty cycle) increases the chances of nanoparticles reaching the cathode surface;

- Due to this longer dwell time, weakly adsorbed particles may detach due to hydrodynamic forces;

- Nanoparticles on the cathode surface are more likely to be incorporated into the coating if the dwell period is shortened (i.e., the duty cycle is increased);

- A shorter stay period lowers the concentration of nanoparticles since it is less likely that they will reach the cathode surface.

The duty cycle is the percentage of the total duration of a cycle, as shown in Equation (12):

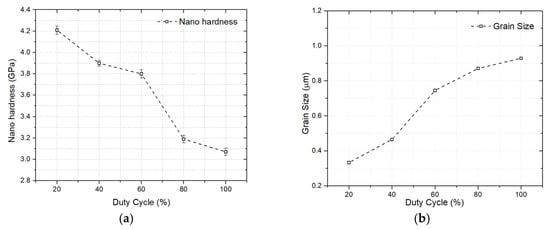

The feasibility of raising the duty cycle from 20% to 100% was investigated by A. John et al. [40] in order to improve the mechanical and surface roughness characteristics of Ni-Al2O3 nano-coatings utilizing pulsed electrodeposition. The results for skewness, kurtosis, and roughness all decreased as the duty cycle increased. However, all duty cycles showed positive asymmetry and flattening greater than 3. The 20% duty cycle exhibits the optimal wear characteristics due to the positive asymmetry and high flattening, which reduce friction. Nano-hardness analysis of the samples revealed that a reduced duty cycle produced increased hardness, thus improving the tribological qualities of the surface (Figure 13a). A shorter dwell time resulted in an increase in grain size, which, in turn, led to a decrease in nano-hardness at a higher duty cycle (Figure 13b).

Figure 13.

(a) Nanoindentation hardness for Ni-Al2O3 coatings at different duty cycles. (b) Grain size of coatings at various duty cycles [40].

Ni-SiC nano-coating electroplating process parameters were optimized by P. Natarajan et al. [19] using the Grey-RSM approach. By adjusting the input parameters, such as frequency (F, Hz), duty cycle (D, %), and peak current density (C, A/cm2), they concentrated on an empirical relationship that was developed to predict micro-hardness (MH), average surface roughness (Ra), specific wear rate (Ws), and coefficient of friction (CoF) of pulse electrodeposition of Ni-SiC nano-coating on AISI 1022 carbon steel. From ANOVA, the linear term of duty cycle (D) is a significant influencing factor on micro-hardness (MH), surface roughness (Ra), with a contribution of 47.57%, 26.22%, respectively. The interaction of frequency (F) and current density (C) are the most significant factors, contributing 48.22% to the wear resistance (Ws). The coefficient of friction (CoF) shows that the linear term of current density (C) has a significant influence with a contribution of 42.62%. Additionally, among the tested coating parameters, the duty cycle showed significant results with the multi-objective optimization of pulsed electrodeposition of composite coatings, compared to other parameters such as peak current density and frequency. According to GRA, the optimal combination of coating parameters for multiple responses are frequency (10 Hz), duty cycle (10%), peak current density (0.2 A/cm2). Co-electrodeposited Ni–SiC coatings were produced by Gyftou et al. [84] using DC and PC with varying duty cycles. Although PC had a reduced wear factor for nanoparticles (20 nm), the duty cycle had a notable impact. Less than 10 × 10−4 mm3 was the lowest value recorded at 50% duty cycle. The main wear mechanism was also abrasive wear, which is characterized by visible scratches that run parallel to the direction of sliding. Nevertheless, the PC sample’s CoF was marginally lower for layers with 20 nm SiC particles.

3.3. Hydrodynamics and Agitation

Several innovative electroplating techniques have been developed over time to reduce costs and improve production efficiency, while considering the environmental impact and overall economic perspective. Reports indicate increased productivity and reduced environmental impact through improved electroplating method and equipment based on the traditional method, including ultrasonic electrodeposition (USED), mechanical stirred electrodeposition (MESED), circulating solution electrodeposition (CSD), magnetic stirred electrodeposition (MASED), and magnetically assisted pulse electrodeposition (MAPED), and jet electrodeposition (JTED) have been used for the fabrication of nanocomposites.

3.3.1. Mechanical Agitation

The agitation speed of the nanoparticles increases their solubility in the electrolyte, which promotes an increase in their concentration in the coating. Conversely, a higher agitation speed reduces this concentration because the turbulent and powerful flow easily removes the particles deposited on the electrode surface [46,49,59,80]. To obtain the desired qualities, the particle content of the second co-electrodeposited phase of the coating is influenced by the stirring speed. Bostani et al. [49] used a gently increasing stirring speed to develop a graded Ni-ZrO2 composite coating. Based on the Guglielmi model, it can be concluded that the stirring speed of the bath can have two opposite effects on the content of co-electrodepositions [67]. The micro hardness values increased steadily from 465 HV (at the coating interface with the substrate) to 615 HV (near the coating surface). F. Kılıc et al. reached the same conclusions [46]. It was found that the optimal stirring speed of 650 rpm made it possible to create co-deposited layers with a high volume percentage of SiC in the Ni matrix and without segregation. It was discovered that the tribological properties of the DES electrolyte were influenced by the rate at which the particle size changed (R. Li et al. [82]). The speed at which mixing takes place is an important factor in determining the number of particles integrated into the metallic matrix. Based on the composite coatings with the highest concentrations of m-SiC and n-SiC particles (12.80% and 5.37% by weight, respectively), the incorporation of large particles into the nickel matrix is facilitated. The average coefficient of friction of a pure Ni coating is approximately 0.76. However, the average coefficients of friction of the Ni–mSiC and Ni–nSiC composite coatings fell to 0.57 and 0.42, respectively. This drop is brought on by the hard SiC particles in the composite coatings, which reduce the direct contact between the steel ball and the metal matrix. The reduction in the friction coefficient also results from the rolling friction with the SiC particles extracted from the composite coatings. Ni–mSiC and Ni–nSiC coatings have wear loss reductions of 70.5% and 88.4%, respectively, as compared to pure Ni coatings.

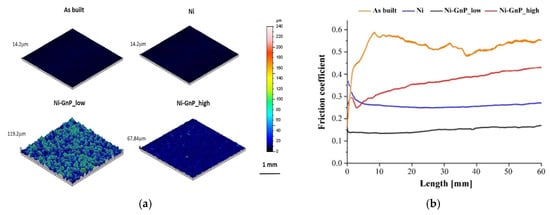

The impact of agitation on a nickel-graphene co-deposition process was reported by D. Almonti et al. [63]. The findings demonstrate how the larger graphene particles are separated by the bath’s agitation, producing a more uniform and smooth covering. Additionally, unlike at greater agitation speeds, the graphene particles are partially exposed at low agitation rates (Figure 14a). Because the film compacts under the indenter’s operation, the increased compactness results in improved resistance to delamination. At low agitation speeds, however, the exposed particles function as a solid lubricant, encouraging sliding and a low coefficient of friction. The smaller particles, on the other hand, do not provide this lubricating function (Figure 14b).

Figure 14.

(a) Surface 3D maps of the different scenarios. (b) Friction coefficient measured through dry sliding test [63].

S.M.J.S Shourije et al. [59] present the influence of stirring speed on the co-deposition of MoS2 particles, microhardness, and friction in a nanostructured nickel matrix. MoS2 particles are more readily transported to the cathode at higher stirring speeds due to the increased hydrodynamic force. However, when the stirring speed increases from 150 to 200 rpm, the percentage of MoS2 particles drops from 20.1% to 6.8%. This is explained by the change in the bath hydrodynamics, which becomes turbulent when the stirrer speed increases from 150 to 200 rpm. When the stirring speed increased from 50 to 150 rpm, the hardness decreased from 612 to 523 VHN, while the MoS2 content in the matrix increased from 15.4% to 20.1%. They then increased the stirring speed from 150 to 200 rpm, resulting in a further increase in hardness from 523 to 573 VHN. Furthermore, in the disc friction test, the coating applied from a stirred bath rotating at 150 rpm exhibited superior performance. This is attributed to the fact that at 150 rpm, the nickel matrix contains a higher MoS2 content. Moreover, the low-friction period of this coating extended beyond 150 rpm, representing approximately 25 to 35% of the total distance [59].

3.3.2. Ultrasonic Agitation