Abstract

Hydrogen-based direct reduction (H-DR) represents an environmentally benign and energy-efficient alternative in ironmaking that has significant industrial potential. This study reviews the current status of H-DR shaft furnaces and accompanying hydrogen-rich reforming technologies (steam and autothermal reforming), assessing the three dominant numerical frameworks used to analyze these processes: (i) porous medium continuum models, (ii) the Eulerian two-fluid model (TFMs), and (iii) coupled computational fluid dynamics (CFD)–discrete element method (DEM) models. The respective trade-offs in terms of computational cost and model accuracy are critically compared. Recent progress is evaluated from an engineering standpoint in four key areas: optimization of the pellet bed structure and gas distribution, thermal control of the reduction zone, sensitivity analysis of operating parameters, and industrial-scale model validation. Current limitations in predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and plant-level transferability are identified, and possible mitigation strategies are discussed. Looking forward, high-fidelity multi-physics coupling, advanced mesoscale descriptions, AI-accelerated surrogate models, and rigorous uncertainty quantification can facilitate effective scalable and intelligent application of hydrogen-based shaft furnace simulations.

1. Introduction

The International Energy Agency Net-Zero Roadmap has established that meeting carbon neutrality targets in the steel sector will require phasing out coal-intensive blast furnace/basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) processing and the deployment of near-zero-emission ironmaking technologies. Direct reduction of iron (DRI) has gained increasing prominence, particularly the hydrogen-based variant (H-DRI), as a non-blast furnace process that produces sponge iron using H2-rich reducing gas. H-DRI plants have been adopted globally, notably in regions with suitable natural gas resources or renewable hydrogen potential. Currently, two commercial shaft furnace platforms, the MIDREX and HYL/Energiron processes, dominate global DRI production. Conventional MIDREX units generate a reducing gas with an H2/CO ratio ≈ 1.5 by steam/CO2 reforming of natural gas (NG) [1], where the latest MIDREX-H2 configuration delivers a hydrogen volume fraction of approximately 90%. In the case of the HYL-ZR (Zero Reformer) variant, autothermal reforming (ATR) converts NG or coke oven gas (COG) into an H2-rich stream in the shaft furnace at 0.6–0.8 MPa and ≈1080 °C. Heat balance data released by Tenova HYL for the HYL-ZR process show that the production of hot DRI with 94% metallization and 3.5% carbon requires a net NG input of 9.6 GJt−1 and an electricity demand of 60–80 kWh t−1, achieving lower specific gas and electricity consumption than the standard MIDREX route [2].

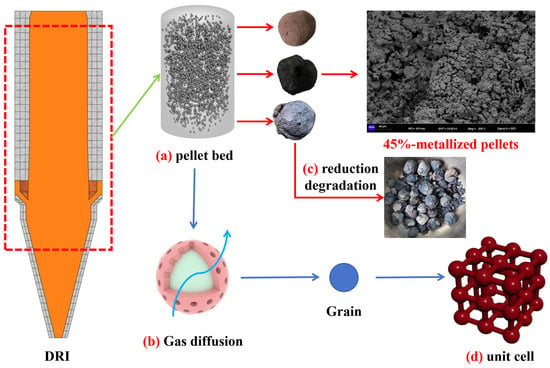

As illustrated in Figure 1, gas-based shaft furnace reduction involves a closely coupled network of physical and chemical phenomena. A reliance solely on physical trials is neither economical nor efficient in exploring the multi-dimensional design space defined by gas composition, flow rate, temperature, pellet size, bed porosity, and operating pressure. Moreover, in the 900–1000 °C range, critical process variables, including local gas composition and in situ metallization, are difficult to measure directly. Consequently, multi-physics numerical simulation has become fundamental to technology development and process optimization [3]. When compared with conventional experimentation, modelling offers lower cost, faster turnaround, and higher spatial–temporal resolution, enabling in-depth analysis of complex thermochemical phenomena that include gas–solid flow, heat and mass transfer, and the multi-stage reduction sequence. Comprehensive models enable researchers to visualize the evolution of temperature fields, predict metallization profiles, optimize gas distribution, and identify process bottlenecks that limit reduction efficiency. As hydrogen metallurgy advances towards full-scale deployment, digital twins and high-fidelity simulations are emerging as indispensable tools for reactor design, scale-up validation, and real-time control integration. In a virtual environment, engineers can test alternative operating strategies, quantify energy consumption for different application scenarios, and assess the influence of parameters such as gas composition, flow rate, and feed size on process performance. As such, modelling and simulation have evolved from academic exercises into a critical tool to enable low-carbon transformation and the industrial implementation of green ironmaking.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the multi-scale processes in a shaft furnace: (a) macroscopic reduction of the pellet bed; (b) gas penetration and diffusion; (c) reduction-induced degradation, (d) metallic iron lattice (α-Fe).

Fei et al. [4] have reviewed the reported simulations of hydrogen shaft furnaces from a chemical engineering standpoint. In addition, Sun et al. [5] have evaluated hydrogen-based reduction technologies with an emphasis on low-carbon steelmaking. Ghadi et al. [6] have addressed the current understanding of direct reduction reaction kinetics. Moreover, Salucci et al. [7] summarized the latest laboratory-scale investigations of hydrogen direct reduction, and Hosseinzadeh et al. [8] have provided a multiscale assessment of shaft and rotary furnaces employed in direct reduction processes. This review offers the first comprehensive examination of gas-reforming strategies applied to hydrogen-based shaft furnaces, addressing modelling and simulation studies for process- and reactor-level optimization with an appraisal of current state of the art, recent advances, persistent challenges, and future research priorities.

We first outline the fundamental process and technological features of hydrogen shaft reduction, then classify current modelling strategies from multi-scale and multi-physics perspectives. Application in reactor geometry optimization, operating parameter control, and industrial scale-up is evaluated, noting major bottlenecks that include strong field coupling, kinetic uncertainty, and the paucity of plant-scale validation data. Finally, we propose key directions in future work, such as hierarchical multi-scale frameworks, hybrid data-driven/physics-informed models, and the development of standardized kinetic databases. Such research will serve to underpin the engineering deployment, intelligent operation, and large-scale industrialization of hydrogen metallurgy via high-accuracy numerical simulation.

2. Overview of the Hydrogen-Based Shaft Furnace

2.1. Process Flow

2.1.1. MIDREX Direct Reduction Process

The MIDREX® process is the most widely deployed hydrogen-based direct reduction (H-DR) technology, employing reformate derived from NG to reduce iron oxides to DRI, has its development history summarized in Table 1. In 2024, MIDREX plants accounted for approximately 53.1% of global sponge iron production and ≈80% of all shaft furnace DRI. The benchmark operating metrics of a standard MIDREX unit are given in Table 2. Given the high energy efficiency and comparatively low greenhouse gas output, the MIDREX route is increasingly recognized as an environmentally benign alternative for ironmaking.

Table 1.

Evolution of the MIDREX gas-based direct reduction processes.

Table 2.

Operational indicators of the MIDREX and HYL-3 processes.

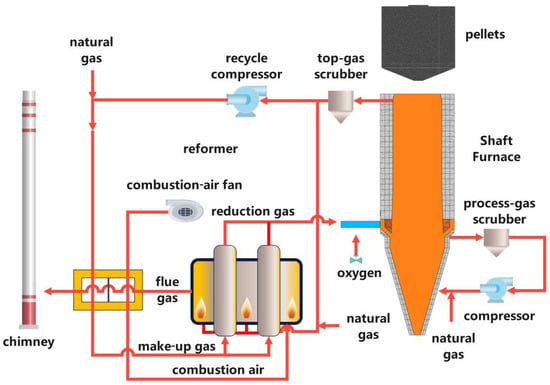

MIDREX NG. The MIDREX standard process is the most prevalent variant of the MIDREX® route. NG is reformed with H2O and CO2 in a tubular reformer packed with hundreds of Ni-based catalyst tubes, generating an H2- and CO-rich reducing gas. The configuration, illustrated schematically in Figure 2, is particularly suitable in regions with abundant natural gas resources. The principal plant sections comprise the shaft furnace, top gas scrubber, cooling gas scrubber, reformer, and associated heat exchangers. Typical operating conditions are reducing gas inlet temperature ≈900 °C, pressure 0.15 MPa, and H2/CO volume ratio ≈ 1.5. Oxidized pellets are maintained in the pre-heat zone for 0.5 h and ≈6 h in the reduction zone. In order to avoid re-oxidation, the hot DRI is cooled by recycled gas introduced at the bottom of the furnace bottom, with a residence time of ≈4 h in the cooling section [25,26,27,28,29].

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the MIDREX process.

MIDREX H2. The MIDREX H2 process is a hydrogen-rich variant of the conventional MIDREX® route in which elemental hydrogen, either pure or blended with NG, provides the primary reducing potential. As the principal reaction by-product is H2O rather than CO2, this configuration enables a substantial reduction in direct carbon emissions. Current commercial trials employ approximately 90 vol% H2, supplemented with a small NG fraction (7–8 vol%) to meet temperature control requirements and to adjust the residual carbon in the product. The long-term objective is full (100%) hydrogen operation. Producing one ton of DRI typically consumes 550–650 Nm3 hydrogen and 50 Nm3 NG, where all other unit operations (shaft furnace, gas-scrubbing trains, and heat recovery equipment) are essentially identical to those in the MIDREX STANDARD scheme.

2.1.2. HYL Direct Reduction Process

The HYL direct reduction route was introduced in 1957 (Table 3). The HYL-1 generation employed batch fixed-bed “charge-and-discharge” reactors, but low associated productivity and high operational complexity led to a complete phase-out of the process. The subsequent HYL-2 configuration adopted fixed-bed reactors and offered higher efficiency, but it is now rarely deployed. The more recent HYL-3 scheme incorporates a continuous counter-current shaft furnace, functionally analogous to the MIDREX unit, while retaining the distinctive HYL gas circuit. Driven by the available resources and market requirements, the platform has been modified to generate several enhanced variants (e.g., HYL-ZR/Energiron) tailored to specific feedstocks, energy mixes, and product specifications [17,30,31].

Table 3.

Evolution of the HYL gas-based direct reduction processes.

- (1)

- HYL-3: As the most widely applied HYL route, HYL-3 employs a counter-current gas–solid moving bed where the reducing gas generation loop is decoupled from the reduction furnace. This process achieves high energy efficiency and stable product quality. Typical unit consumption indicators in Table 2 indicate that conventional MIDREX and HYL-3 gas-based DR processes operate within a broadly comparable performance range but exhibit distinct characteristics. MIDREX generally produces DRI with metallization levels above 92%, whereas HYL-3 typically attains metallization of around 94% combined with a higher and more adjustable carbon content (approximately 3–4 wt%). Both routes show similar specific gas consumption (≈10–11 GJ t−1 iron), but the specific power demand of HYL-3 (≈60–75 kWh t−1) is noticeably lower than the ≈100 kWh t−1 reported for MIDREX. Overall, both technologies are capable of delivering high-quality DRI; however, HYL-3 offers slightly higher metallization, greater flexibility in carbon adjustment, and improved electrical energy efficiency.

- (2)

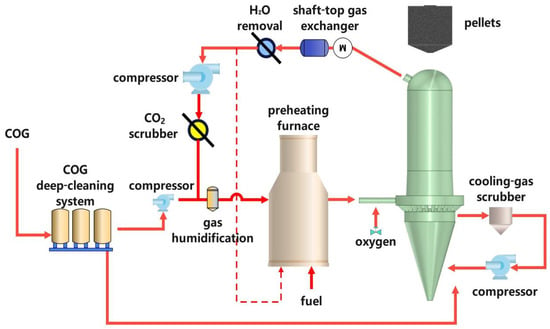

- HYL-ZR (Energiron-ZR): Co-developed by HYL and Tenova in 2009, this variant employs autothermal reforming (ATR) to generate an H2- and CO-rich syngas within the plant battery limits (Figure 3). The feedstock may include NG, coal-derived syngas, COG, or other process gases. Oxygen is then injected immediately upstream of the shaft for partial oxidation reforming. The shaft furnace operates at 750–900 °C and ≈0.5 MPa. As the reducing gas is produced in situ, no external reformer is required, markedly simplifying the flowsheet and lowering capital expenditure.

Figure 3. Process flow diagram for HYL-ZR.

Figure 3. Process flow diagram for HYL-ZR.

A comparison of the entries in Table 1 and Table 2 reveals that, relative to the standard MIDREX® route, the HYL-3 process consumes less reducing gas and electrical energy per ton of DRI while achieving a higher metallization degree. The HYL-3 reformate enters the shaft at ≈85 vol% H2, ≈0.5 MPa, and ≈900 °C. As steam, rather than oxygen, acts as the cracking agent, catalyst sulfur poisoning is circumvented and no restriction is imposed on the sulfur content of the incoming ore. In addition, the major unit operations of the HYL scheme are functionally decoupled, so any failure in the shaft furnace does not curtail reformer throughput, representing a significant improvement in overall utilization.

At identical reactor volumes, the HYL-ZR (Energiron-ZR) configuration not only exceeds MIDREX in DRI productivity, due to its broad feed gas flexibility and in-shaft autothermal reforming, but also delivers a lower carbon footprint. As shown in Table 4, the HYL-ZR process incorporates a high-pressure CO2 absorption unit in the recycling loop, removing 45–50% of the top gas carbon and limiting direct emissions to 0.38–0.44 t CO2 per t DRI. By comparison, the standard MIDREX-NG operation recycles the top gas after water condensation only. Consequently, unless an optional amine-scrubbing module is installed, direct emissions are higher (approximately 0.50 t CO2 per t DRI). Utilizing this add-on scrubber, MIDREX can approach the HYL-ZR footprint, but the environmental benefit is no longer intrinsic to the base process.

Table 4.

Comparison of carbon emissions.

2.2. Gas-Reforming Method

In H-DRI, reforming the feed gas into a high-purity reducing gas represents a pivotal step. The feedstock can be NG or COG, where the catalytic component is critical in converting CH4 to a syngas rich in H2 and CO that is subsequently used to produce DRI or downstream products. As summarized in Table 5, four reforming routes are currently deployed globally in DRI operations: (i) steam methane reforming (SMR), (ii) partial oxidation reforming (POX), (iii) autothermal reforming (ATR), and (iv) dry reforming with CO2 (DRM).

Table 5.

Mainstream reforming methods used in global processes.

These routes employ noble metal or non-noble metal catalysts. Although noble metals provide high activity and superior resistance to coking, the associated high cost has largely restricted application to laboratory studies. Nickel-based catalysts are abundant and inexpensive, exhibiting high reforming activity, and serve as the industry standard. Both MIDREX and HYL-3 processes employ Ni catalysts: The MIDREX reformer contains hundreds of Ni-filled tubes for combined steam/CO2 reforming, whereas the HYL-3 scheme uses Ni-based reformer tubes in a cracking furnace to promote SMR.

The SMR is the predominant route for generating H2-rich gas in H-DR, offering the highest hydrogen purity and a well-established industrial infrastructure. However, each reforming strategy presents a distinct balance of benefits and drawbacks, as summarized in Table 6. When there is an ample natural gas supply, sufficient heat input, and a high hydrogen demand, SMR is the preferred option. Under conditions where energy costs are comparatively low, non-catalytic partial oxidation can lower the external heat duty and associated operating costs.

Table 6.

Advantages and disadvantages associated with different reforming methods.

In the case of plants that rely on COG and require an ad hoc adjustment of the synthesis gas composition, autothermal reforming enables energy-efficient operation without the need for a dedicated external reformer. Conversely, CO2 dry reforming is a viable option for steelmakers seeking to valorize waste CO2 while tailoring the H2/CO ratio of the reducing gas.

In practice, operators should select the reforming route, or combination of routes, that best matches their resource base, environmental constraints, and economic objectives. Hybrid configurations that incorporate two or more reforming methods can, in certain cases, deliver the most viable solution for direct reduction ironmaking.

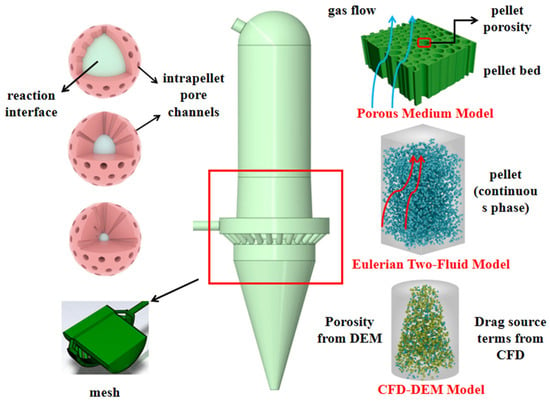

3. Modelling Approaches

Hydrogen-based shaft furnace reduction is governed by a network of closely coupled phenomena, including gas–solid multiphase flow, heat transfer, multistage reduction reactions, and intra-pellet mass diffusion. Accurately capturing these interactions by numerical simulation is essential for predicting furnace performance, optimizing operating parameters, and informing the design of low-carbon ironmaking processes. Over the past two decades, researchers have progressively integrated gas–solid hydrodynamics, thermal transport, reaction kinetics, and intra-particle diffusion into increasingly sophisticated models of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces. In order to accommodate differing spatial scales, modelling objectives, and computational budgets, several strategies have been developed. As illustrated in Figure 4, three frameworks are now widely employed: (i) porous medium continuum models, (ii) the Eulerian two-fluid (gas–solid) model, and (iii) coupled CFD–DEM approaches.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the three principal modelling methods.

3.1. Porous Medium Model

The porous medium model is currently the most widely applied framework to simulate gas flow in shaft furnaces. In this approach, the iron ore pellet-packed bed is treated as a stationary, continuous porous medium, and the inter-particle void structure is homogenized, taking average values of porosity and permeability. This homogenization allows for the solution of continuum-scale momentum, energy-transfer, and mass-transfer equations, enabling adequate predictive accuracy while significantly reducing computational cost, which is an important consideration in engineering-scale simulations. The formulation is generally built on the following assumptions: (i) stationary solid phase: The pellet bed is immobile, neglecting pellet displacement and rearrangement, and only the gas seepage flow through the fixed granular skeleton is modelled; (ii) homogenized, quasi-isotropic medium: The densely packed pellets are regarded as a homogeneous, isotropic (or weakly anisotropic) continuum, where effective medium properties (average porosity and permeability) approximate the actual heterogeneous packing structure; and (iii) empirical resistance law: Local pressure losses are described by empirical correlations, such as the Ergun equation.

- (1)

- Mass conservation equation:

: Bed porosity

: Gas-phase velocity vector, m s−1

- (2)

- Momentum conservation equation incorporating the Ergun drag term:

: Permeability of the porous medium estimated using the Ergun correlation, m2

: Forchheimer (inertial) drag coefficient

: Particle diameter, m

: Gas viscosity and density, pa s; kg m−3

The first term represents viscous resistance, and the second term describes inertial resistance.

- (3)

- Energy conservation equation with either a single-temperature or dual-temperature gas–solid formulation:

isothermal gas–solid assumption (isothermal wall):

Dual-temperature model allowing for separate gas and solid temperature fields (non-isothermal wall and phase interfaces):

: Inter-phase heat-transfer coefficient (based on the Nusselt number), W m−2 K−1

: Effective thermal conductivity of the gas–solid porous medium, W m−1 K−1

: Prandtl number, ratio of momentum diffusivity (kinematic viscosity) to thermal diffusivity.

: Reynolds number, particle-scale.

a: Specific surface area based on particle geometry, m−1

: Gas and solid temperatures, K

: Chemical reaction source term, W m−3

Given the computational economy and conceptual clarity, the porous medium framework has been widely adopted at the engineering scale and underpins several classical shaft furnace models. A notable example is the REDUCTOR code, which utilizes a two-dimensional porous flow formulation coupled with heat transfer and multi-step reduction kinetics. The earliest implementation was the two-dimensional, axisymmetric model for pellet reduction in shaft furnaces proposed by Hara et al. in 1976 [50], which successfully predicted in-furnace gas–solid transport and reaction rates. Takenaka et al. [51] subsequently applied this model to industrial operations to guide process parameter optimization. Overall, the porous medium approach offers a number of advantages; the conceptual simplicity, numerical robustness, and high computational efficiency make it well suited for plant-scale system analysis and flowsheet optimization. The framework can be readily coupled to reaction kinetics sub-models, such as the three-interface unreacted core model or grain interfacial models, accommodating complex gas–solid reaction sequences.

These benefits are, however, based on idealized assumptions that limit the predictive capacity of the model. As it is assumed that the packed bed is homogenized, the framework cannot resolve discrete particle phenomena: the evolution of intra-pellet porosity, pellet swelling, or decrepitation; the formation of preferential gas channels, inter-particle friction, and slip; or bed rearrangement. Consequently, this approach does not capture structural changes that occur during reduction, such as shrinkage-induced densification in highly metallized zones, and the spatial averaging of porosity can cause inaccuracy for regions where the packing is inherently non-uniform.

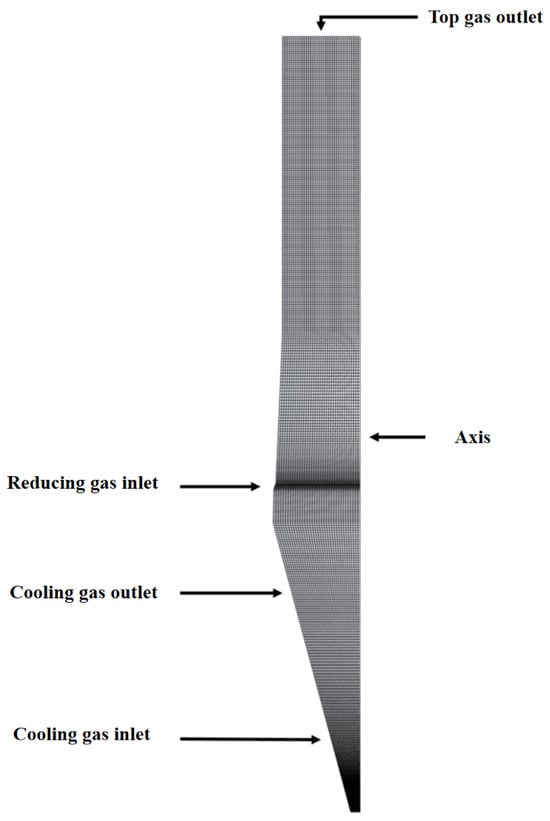

In addition to the above balance equations, a complete porous medium formulation requires appropriate boundary conditions. In most porous medium simulations of shaft furnaces, an axisymmetric geometry is assumed (Figure 5). Pressure outlet boundary conditions are typically imposed at the top of the shaft and at the lower gas off-takes, whereas the inlets for the hot reducing gas and cooling gas are specified as mass flow inlets with predefined temperatures and species compositions. No-slip wall conditions are applied along the refractory lining, coupled with either adiabatic or isothermal thermal boundary conditions, depending on the desired level of detail. Symmetry conditions are enforced along the central axis of the furnace. The solid burden is modelled as a downward-moving porous medium with a specified porosity distribution; its inlet mass flux, temperature, and initial metallization degree at the charging level, as well as the target metallization degree at the discharge, are generally prescribed in accordance with operational practices.

Figure 5.

Model geometry and boundary conditions.

Moreover, by treating the burden as a uniform continuum, the model is unable to capture local maldistributions in flow and composition. In practice, charging patterns often create particle-size segregation, leading to a zone-dependent porosity and permeability and, in turn, bypass flow or stagnant “dead” regions. If such heterogeneities are not represented, the simulation may locally over- or under-predict key variables such as gas velocity, temperature, and metallization.

3.2. Eulerian Two-Fluid Model

The TFM treats both gas and solid phases as interpenetrating continua, solving separate sets of mass and momentum conservation equations for each phase. Unlike the porous medium approach, which treats the solid phase as a rigid, static skeleton with a prescribed porosity, the TFM explicitly resolves the velocity, temperature, and composition fields of the particulate phase. This enables the model to capture slip velocities between phases, radial non-uniformities, and local phenomena such as stagnant zones or channel flow. Consequently, the TFM is particularly suitable for applications involving heterogeneous packing, multi-point gas injection, or localized recirculation.

The governing equations of the TFM are given below.

- (1)

- Mass conservation equation:

Let g and s denote the gas and solid phases with volume fractions (α):

Gas:

Solid:

- (2)

- Momentum conservation equation:

Gas:

Solid:

: Inter-phase momentum exchange term (evaluated from the Gidaspow or Wen–Yu drag correlation), N m−3

: Effective stress tensor that accounts for viscous stresses and particle–particle interactions, Pa

- (3)

- Energy conservation equation:

Gas:

Solid:

: Gas and solid temperatures, K

: Phase-specific heat capacities, J kg−1 K−1

: Thermal conductivity, W m−1 K−1

: Inter-phase heat-transfer coefficient (based on the Nusselt number), W m−2 K−1

: Solid specific surface area per unit volume, m−1, approximated from:

: chemical reaction source term, W m−3

Applying the TFM framework, the solid phase is treated as a pseudo-fluid with effective density and viscosity, where momentum exchange between the two phases is modelled using empirical drag correlations, such as those developed by Gidaspow [52], Syamlal and O’Brien [53], or Wen and Yu [54]. The governing set comprises individual continuity and momentum equations for both gas and solid phases, coupled using interfacial source terms. Energy and multi-species transport equations can likewise be formulated for each phase, with heat-transfer and mass-transfer source terms accounting for inter-phase exchange. Turbulence closure is commonly achieved using multiphase k–ε models [55], large eddy simulation/Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes hybrid turbulence model (LES-RANS) schemes [56], or (more recent) multiscale turbulence approaches, depending on the required accuracy and available computational budget.

When compared with porous medium formulations, the Eulerian approach delivers superior spatial resolution and physical fidelity, capturing slip velocities, channel flow, and localized hotspots. This comes at the cost of significantly higher computational demand and stricter convergence criteria, and is more suitable for research-level analyses and high-resolution studies where detailed flow field information is essential.

The TEM explicitly resolves gas–solid slip, enabling an effective assessment of radial maldistribution, local channel flow, and stagnant “dead” zones in the shaft. As it can be coupled with multi-step reaction kinetics, non-uniform heat transfer, and stress fields, the framework can analyze transient operations and unconventional gas distribution strategies. Moreover, the computational demand is approximately two orders of magnitude lower than that associated with CFD-DEM, where parallelized CFD solvers enable full three-dimensional furnace simulations. Nonetheless, the lack of drag and granular viscosity correlations specifically for hydrogen–pellet systems necessitates generic closures that may not fully represent in-furnace conditions, while the computational cost is significantly higher than that of porous medium models.

3.3. DEM Model

The DEM, introduced by Cundall in 1971 [57,58], extends molecular dynamics concepts to model granular materials. In DEM, the burden bed is represented as an assembly of millions to billions of individual particles. Newton’s second law and Euler rotation equations are integrated for each pellet, explicitly tracking position, velocity, contact force, and angular motion. The particle-level description reveals charging patterns, packing morphology, descent trajectories, and the consequent evolution of porosity and local gas channels. In contrast to continuum models, DEM reproduces inter-particle collision, stacking, sliding, and flow with full kinematic fidelity, which is particularly important in investigating the microstructural behavior of shaft furnace burdens [59].

As the DEM resolves only the solid phase, shaft furnace gas–solid flows are typically simulated using a coupled CFD–DEM framework. CFD simulations commonly apply porous medium models to represent the gas-phase flow field in hydrogen-based shaft furnaces, while DEM is employed to track particle trajectories and the local porosity field; momentum and heat exchange are linked through interphase source terms. The three common framework coupling options employed in shaft furnace studies are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

CFD-DEM model coupling in typical applications.

The DEM framework solves the translational and rotational motion of each particle by integrating Newton’s second law, with inter-particle forces computed via Hertzian contact mechanics (normal collision forces) and a Coulomb friction model (tangential friction forces). Each pellet is assigned material and geometric properties, mass, radius, elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and static/dynamic friction coefficients so that interactions with neighboring particles and confining walls can be accurately modelled.

In a coupled CFD–DEM simulation, the discrete solid phase is advanced according to the particle-scale equations, while the gas phase is solved on a Eulerian grid. Momentum, heat, and mass transfer between phases are described and exchanged through source terms. The full set of governing equations for the CFD–DEM framework is presented below.

- (1)

- Governing equations for the gas phase:

The gas phase is typically modelled using porous medium-corrected, volume-averaged Navier–Stokes equations, which account for particle effects.

Mass conservation equation:

: Local porosity ε, supplied by the DEM solver

: Gas-phase velocity vector u, m s−1

: Gas density, kg m−3

Momentum conservation equation:

: Total drag force exerted by the particles on the gas, N

: Individual drag force on particle , N

: Gas–solid momentum exchange coefficient, kg s−1

- (2)

- Governing equations for the solid particles:

Particle motion obeys Newton’s second law for translation and Euler’s equation for rotation.

Translational equation of motion:

: Mass of particle , kg

: Contact forces from neighboring particles and walls, N

: Gas–solid drag force, N

: Gravitational force, N

: Magnetic, electric and other optional body forces, N

Rotational (angular) equation of motion:

: Moment of inertia, kg m2

: Angular velocity, rad s−1

: Torque due to contact/friction, N m

A coupled CFD–DEM framework can accurately reproduce particle-scale phenomena such as stratified charging, packing heterogeneity, channel flow, and bed collapse. By dynamically feeding the local porosity field from DEM back into the CFD solver, gas–solid interaction hotspots and reaction fronts are captured. Moreover, this approach generates statistics regarding particle residence time, charging trajectories, and stress distributions that can inform equipment design and troubleshooting.

For a gas-based shaft furnace rated at 0.6 Mt a−1, the active reduction zone (approximately 5 m in internal diameter and 15 m in height) occupies 300 m3. With an initial bed porosity of 0.40 and spherical pellets 10 mm in diameter, this volume contains 3.3 × 108 pellets at any given time. A furnace-scale, high-temperature simulation must resolve ≥108 discrete particles, a computational demand that is not feasible for standard central processing unit (CPU) platforms. Coarse-graining can mitigate the load but introduces scale distortion errors. In addition, pellet sticking and reduction-induced pulverization involve complex thermo-mechanical mechanisms that are not fully represented by current elastic–plastic–cohesive contact models. Consequently, DEM applications in shaft furnace research are limited to small-scale or cold-state analyses, initial bed structure reconstruction, and the generation of structural parameters for higher-level models such as REDUCTOR or hybrid CFD–DEM simulations.

3.4. Model Comparison

Flow-field modelling progresses from porous medium formulations to more complex TFM and finally to the detailed DEM simulations, reflecting an increase in physical resolution and computational cost. The differences in these three frameworks with respect to governing principles, computational demand, representable phenomena, and coupling capability are identified in Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison of the three models: porous medium, TFM, and CFD-DEM.

The porous medium model, which represents the pellet bed as an isotropic, or radially graded, continuous medium, represents a workhorse in terms of engineering studies. The streamlined structure and high computational efficiency are well suited for parameter sweeps, process screening, and preliminary design optimization. Although the porous medium approach cannot resolve local flow distortions, structural heterogeneities, or dynamic particle migration, it can be integrated readily with reaction kinetics sub-models and thermal solvers.

The TFM solves separate continuity and momentum equations for the gas and solid phases, coupling their behavior through interphase drag terms. This formulation enhances the resolution of radial maldistribution, multi-point gas injection effects, and phase slip velocities, providing a more realistic bed-scale description of gas–solid distributions. Consequently, the TFM is widely employed in academic research and detailed multi-physics analyses. Application of the TFM requires fine grid resolution, robust convergence, and stable solver coupling, and is therefore best suited to simulations with substantial computational resources.

The DEM focuses on particle-scale kinematics and interactions, accurately capturing charging patterns, packing-density evolution, channel formation, and pellet-scale heterogeneity. When coupled with CFD, the DEM offers a powerful tool for investigating cold-state structural design and particle-level gas penetration pathways. Given the severe computational burden, CFD–DEM applications are largely confined to cold-state modelling, small-scale geometry analyses, or the generation of structural parameters for use in macro-scale models.

Taking an overview of these systems, no single framework is universally optimal for every shaft furnace modelling objective. Porous medium formulations deliver robust, plant-scale performance. The TFM offers higher resolution of detailed flow phenomena, and CFD-DEM techniques provide critical insights into particle-scale mechanisms. In multiscale or hybrid strategies, these approaches can be concatenated or hierarchically coupled, enabling a balance of computational efficiency with predictive accuracy.

4. Application of Numerical Modelling in Process and Reactor Optimization

Numerical simulation serves as a means of optimizing process flow and reactor systems. In hydrogen-based shaft furnaces, gas–solid reactions, heat and mass transfer, and multiphase flow are closely coupled, where conventional empirical methods are inadequate for a comprehensive analysis and design. Modelling provides a systematic, quantitative framework that elucidates the governing mechanisms, predicting operating behavior directed at an optimization of equipment and operating conditions.

A compilation of the reported modelling approaches adopted in hydrogen-based shaft furnace modelling is provided in Table 9.

Table 9.

Reported approaches to flow, heat transfer, and diffusion/reaction modelling with associated applications.

4.1. Bed Layer Structure

The reaction efficiency of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces requires a uniform penetration of H2/CO through the pellet bed. Irregular packing, the large furnace height-to-diameter ratio, and intricate distributor geometry can give rise to bypass flow, dead zones, and local over-pressurization, inhibiting metallization and triggering hotspots. The early studies employed porous medium CFD. Bai et al. [64] calibrated the ventilation–velocity–pressure drop relationship and reproduced the macroscopic resistance and temperature fields with a 5% error, providing a suitable basis for subsequent design refinements. The application of particle-resolved CFD–DEM [84] demonstrated that asymmetric size grading disrupts the main gas stream and prolongs residence time, establishing the need for coordinated charging and gas distribution schemes.

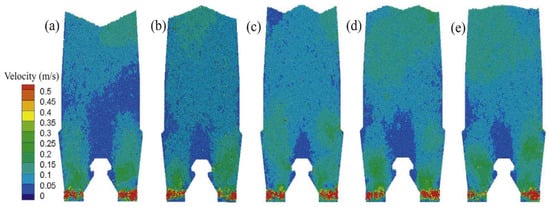

In terms of distributor optimization, installing a central gas distributor (CGD) in a COREX shaft served to eliminate the core dead zone and increased metallization by ≈6% [72]. Ghadi et al. [10] have proposed a dual-inlet hydrogen injection that reduced the radial temperature gradients and total energy usage by 5%. Dual-row re-injection improved top gas utilization by ≈12% and lowered the energy demand by ≈8%. Burden profiling is also critical, with Shao et al. [79] having indicated that a “W”-shaped burden yields the most uniform velocity field. A “V”-shaped profile serves to minimize pressure drop, allowing operators to switch dynamically according to production versus energy priorities. As shown in Figure 6, Zhou et al. [77] compared five COREX burden profiles: V, inverse V, W, M, and flap. Each profile exhibited similar overall descending velocities with distinct flow and permeability signatures: The V-profile gives the highest bed porosity and lowest pressure drop, where the inverse provides intermediate permeability; the flap profile yields the lowest porosity and highest pressure loss; and the W-profile delivers the most uniform gas–solid flow. These differences, driven by profile-dependent size segregation of coke and pellets, offer practical levers for balancing pressure drop and flow uniformity in shaft furnace operation.

Figure 6.

Transient burden descending velocity: (a) “V” shape, (b) inverse “V” shape, (c) “W” shape, (d) “M” shape, and (e) “flap” shape; from Ref. [61].

In addressing high-temperature sticking, Alencar et al. [78] introduced a sticking (agglomeration) index. When the index exceeds 15%, the bed pressure drop rises by >25%, necessitating strict control of pellet tackiness in the hot zone. The DEM–CFD work conducted by Hu [68] has revealed that an uneven descent in the lower column causes local piling; a spiral blade leveler can mitigate this effect. Tang et al. [63] demonstrated that a “Z”-shaped graded bed can exploit axial heat and reduction potential more effectively, enhancing gas and heat utilization.

Taking an overview of the literature, the research has progressed from macroscopic continuum models to particle-resolved, multi-physics frameworks supported by fast algorithms. This has contributed to a quantitative design paradigm addressing burden profiling, distributor architecture, and sticking control. Unified mechanistic descriptions are still required for dynamic porosity variation under sticking/melting conditions, transient flow during distributor switching, and the long-term permeability impact of crack–agglomeration coupling. Integrating AI-driven real-time calibration with pilot-scale visualization testbeds will be pivotal for further enhancing gas flow uniformity and hydrogen utilization in next-generation shaft furnaces.

4.2. Temperature Field Control

In the coupled, multi-physics environment of a hydrogen-based shaft furnace, the axial advance of the reduction front and the radial temperature gradient jointly dictate metallization efficiency, hydrogen utilization, and refractory safety. In order to elucidate these interactions and define the optimal operating windows, modelling has progressed from one-dimensional dynamic kinetics to fully three-dimensional CFD–DEM frameworks calibrated with respect to industrial plant data. The following temperature-related factors are critical in ensuring process efficiency.

Defining the optimal reduction temperature. Using a 3-D CFD–RANS model coupled to a three-interface unreacted-core kinetics scheme, Liu et al. [81] applied the VIKOR multi-criterion method and identified 1173 K as a compromise set point that maximizes metallization while balancing H2 utilization and CO2 emissions; higher temperatures lower thermal efficiency and increase carbon intensity. Although limited in scale, the early model proposed by Hara et al.’s [50] model served to validate the reliability of the unreacted core framework under varying gradients, providing a viable theoretical basis for subsequent temperature-field coupling.

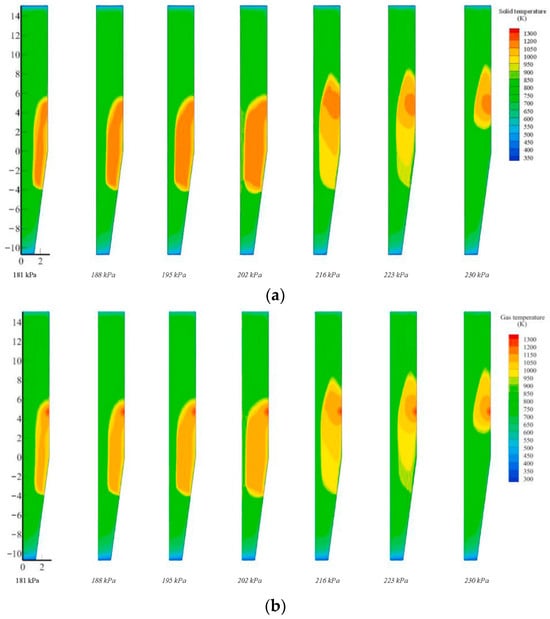

Radial temperature control. Full-scale simulations by Li et al. [85] showed that the cooling gas back pressure is the dominant lever for controlling gas path distribution, where an optimized burden charging reduced center-to-wall metallization discrepancies to <5%. As shown in Figure 7, the present simulation results further confirm that adjusting the cooling gas outlet back pressure is an effective means of achieving radial temperature control in the shaft furnace. With increasing back pressure, the gas flow pattern is modified, and the solid temperature in the transition zone first rises and then decreases; at around 230 kPa, the transition zone temperature becomes comparable to that of the cooling zone, indicating strong penetration of the cooling gas. The gas temperature exhibits a similar distribution, and the combination of a high-temperature, high-flow reducing gas stream and small pellet size promotes rapid interphase heat transfer, which quickly reduces the gas–solid temperature difference in the upper reduction zone while enhancing the cooling effect on DRI near the discharge. Hamadeh et al. [70] modelled the MIDREX furnace as eight thermo-reactive zones and ten kinetic steps, revealing that a central low-temperature band suppresses reduction and lowers H2 utilization, a response that can be mitigated by elevating the inlet gas temperature or adjusting pellet size.

Figure 7.

Gas–solid temperature distributions with varying pressure: (a) pellet bed temperature field; (b) reducing gas temperature field; from Ref. [10].

Dynamic operating parameters. Shao et al. [60] applied an axisymmetric multi-physics model to quantify the interplay of top gas recycling rate, inlet gas temperature, and furnace height: When recycle exceeds 35 m3 t−1, the thermal efficiency drops, but a moderate inlet temperature increase combined with a taller shaft can reduce recycling by ≈20% without throughput loss.

Transient thermo-fluid behavior. Han [67] applied a hybrid porous medium DEM to demonstrate that increasing inlet flow narrows the axial temperature gradient but raises the top gas temperature, lowering overall efficiency; an inverted “V” burden increases the residence time and suppresses dust carryover. Long [68] extended this work, reporting that an uneven descent of the lower burden forms local pile-ups and thermal hotspots, which can be eliminated by using a spiral blade leveler that continuously flattens the burden surface.

Fast algorithms. In order to address the prohibitive cost of large-scale sensitivity studies, Spijker et al. [62] developed the volume fraction smoother (VFS) and timescale splitting method (TSSM) smooth sub-grid algorithm, accelerating CFD–DEM by an order of magnitude while maintaining temperature inconsistencies below 3 K.

Although current models can now limit temperature field deviations to within 3 K, there is no reported unified mechanism that describes radiative heat transfer at high H2 concentrations, pellet sticking/melting, or fine generation from high-temperature reduction. Moreover, industrial-scale closed-loop control of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces still relies principally on empirical rules.

4.3. Recovery Gas Composition and Process Parameter Optimization

Hydrogen utilization in shaft furnaces is constrained by the thermodynamic driving force of the gas (H2/CO/H2O ratio) and operating parameters such as inlet flow rate, pellet size and porosity, and kinetic constants. Recent modelling studies [10,60,61,65,66,67,68,73,80,82,86] show that H2 consumption and CO2 emissions can be significantly reduced without sacrificing metallization by applying strategies such as partial oxidation and hybrid gas blending, top gas recycling, and hydrogen enrichment.

Gas blending and partial oxidation. Lu et al. [61] developed a two-dimensional multi-feed model that established that an increase in the COG fraction above 0.75 vol% lowers carbon emissions by 18% relative to pure NG operation while maintaining metallization above 94%; excessive cooling gas diminishes this effect and necessitates trade-off optimization. In a series of porous medium experiments and simulation, Palacios et al. [66] confirmed that high-equivalence-ratio partial oxidation of CH4 generates in situ H2/CO, achieving >80% reduction and supplying exothermic heat that cuts the need for external firing.

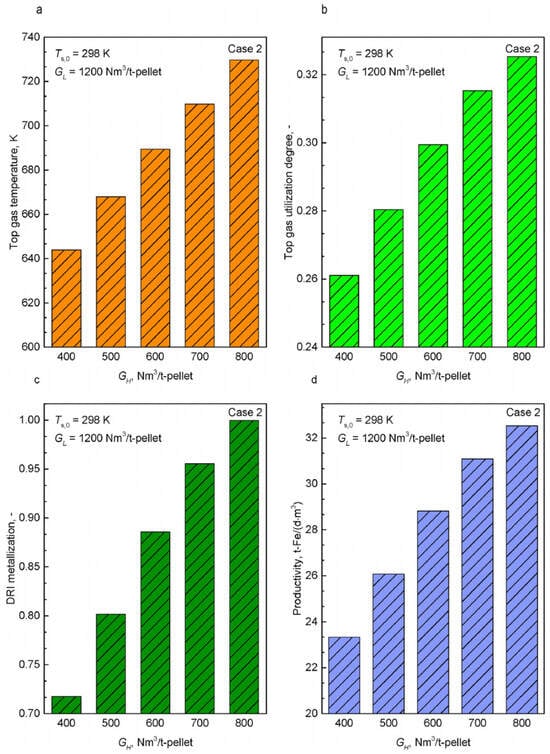

Top gas recycling. Using one-dimensional shaft furnace models for a pure hydrogen shaft furnace equipped with top gas recycling, Shao et al. [60,79] demonstrated that the strong endothermic heat demand of H2 reduction necessitates a high gas feed rate, resulting in a large recycling-to-fresh H2 ratio (>3) and a low H2 utilization degree (<25%). Consequently, a substantial fraction of hydrogen circulates primarily as a heat carrier rather than an active reductant. Building on this baseline, they proposed a modified top gas-recycling configuration featuring dual-row high-temperature gas injection. As illustrated in Figure 8 (from Shao et al. [79]), increasing the upper-row injection rate (GH) systematically elevates the top gas temperature, top gas utilization degree, DRI metallization, and furnace productivity. In the optimized dual-row case with GH = 800 Nm3 t−1 of pellets, the top gas utilization degree increases from 0.229 to 0.325 (approximately a 42% relative increase), while the total specific energy consumption decreases slightly from 14.8 to 14.7 GJ t−1 Fe compared with the single-row reference case, indicating a more favorable thermochemical state and enhanced heat utilization under dual-row injection. Complementary parametric studies on the original top gas-recycling design further reveal that elevating the feed gas temperature or extending the furnace height can reduce the required recycle rate; however, once the shaft length exceeds a critical value, the marginal benefit diminishes, and the total energy consumption begins to increase due to additional compression work.

Figure 8.

Predicted performance indices, including top gas temperature (a), top gas utilization degree (b), DRI metallization (c), and productivity (d), under the conditions of varying GH at Ts,0 = 298 K and GL = 1200 Nm3 t−1-pellet. From Ref. [79].

Inert and methane dilution. DEM–CFD work by Long [68] suggests that moderate N2 or CH4 addition, coupled with a higher inlet temperature, can lower H2 demand by ≈15% at a constant reduction rate, provided a spiral blade leveler is used to maintain a uniform burden surface to prevent local H2 starvation.

Undiluted hydrogen operation. da Costa et al. [86] combined a laboratory reduction of hematite briquettes with a 2D axisymmetric model, identifying 800 °C as the optimum temperature; sintering above this limit densified the surface and impeded reaction. The higher reductive power of undiluted H2 facilitates the design of a more compact furnace.

Distributor optimization. Using a stream function/velocity potential solver, Ghadi et al. [10] demonstrated that a twin jet system extends the active reduction zone, lowering the pressure drop with improved mixing, and increasing DRI output and quality while conserving energy. Bai et al. [65] investigated the effects of oxygen injection in the upper region of the reduction zone, positioned 7 m above the furnace bottom. At an oxygen injection rate of 26.78 Nm3 per metric ton of iron produced, the oxygen-injected shaft furnace, relative to a conventional hydrogen-based shaft furnace, demonstrated a 33.43% increase in hydrogen utilization, a 22.08% decrease in hydrogen consumption, a 61.84% reduction in the reducing potential of the top gas, and a 14.72% decrease in specific energy consumption. Additionally, the burden temperature rose in the vicinity of the injection site and in the upper shaft.

Parameter sensitivity. Finite element analysis by Chai et al. [80] has shown that the primary reduction occurs between 0.5 m and 2 m above the bustle pipe; adjusting gas parameters increases efficiency. A dual energy equation model proposed by Li Shengkang [73] has indicated that (a) increasing the H2 fraction at 900 °C accelerates reduction but also increases consumption, (b) a cooling cone angle of <80° is optimal, and (c) the core descent is faster than at the periphery, lowering residence time. It should be noted that bed motion was neglected in this study. In applying CFD–DEM, Kinaci et al. [75] reported a ±10 kJ mol−1 uncertainty in the activation energy for wüstite → Fe that alters the ultimate metallization by >10%. In a three-dimensional CFD study by Liu et al. [82], an optimum (≈2800 Nm3 h−1) gas flow and mean pellet size (≈10 mm) served to balance pressure drop and reduction where a Rist-diagram check confirmed thermodynamic feasibility. Hara et al. [50] applied a single-pellet 1D model, demonstrating that the product of porosity and gas temperature defines the diffusion–reaction mixed-control regime; every 50 K incremental increase allows porosity to fall by ≈0.03 at constant conversion. At the bed scale, the simulation reported by Han [67] showed that increasing flow narrows the axial temperature gradient but increases top gas temperature and reduces efficiency; use of an inverted “V” burden compensates by increasing residence time.

Despite these advances, predictive accuracy remains limited at high H2 levels, which is caused by uncertainties in catalytic reforming, carbon deposition, and water–gas shift kinetics. For example, the ATR inside a shaft furnace is fundamentally a high-temperature catalytic conversion of methane over the pelletized iron-based catalyst. Nevertheless, the majority of mathematical models capture this process through the global stoichiometric reaction, , overlooking the detailed catalytic reforming mechanism and carbon deposition phenomena. Addressing these gaps is essential for reliable optimization of hydrogen utilization in next-generation shaft furnaces.

4.4. Verification of Industrial-Scale Models and System Integration

The successful design and operation of industrial-scale hydrogen-based shaft furnaces require effective integration of multi-scale numerical models with plant data to ensure reliable predictions and intelligent decision-making under dynamic loads, fluctuating feedstocks, and stringent decarbonization targets. Recent advances follow two complementary tracks: (i) full-furnace steady- and transient-state calibration, and (ii) flowsheet-level heat–mass–energy coupling.

Benchmarking against long-term operating data has shown that numerical shaft furnace models can reproduce the observed trends in temperature, pressure drop, and metallization with good fidelity. Using a two-dimensional multiphase RANS framework, Castro et al. [69] further demonstrated that these models are capable of capturing the coupled flow, heat-transfer, and mass-transfer behavior in industrial gas-based direct reduction shaft furnaces. Béchara et al. [14] embedded particle-scale kinetics into an Aspen Plus flowsheet, demonstrating that effective shaft–reformer heat integration can reduce CO2 emissions by 18–22%. Alhumaizi and co-workers [9] developed a coupled mass and energy balance model for the MIDREX reformer–reduction pair, incorporating intra-reformer mass-transfer resistance and multi-step shaft kinetics. They validated the model with plant data and quantified the impact of key inputs on DRI accuracy.

A review by Fei et al. [4] has established that site-wide models encompassing the shaft furnace, reformer, top gas recycling loop, and renewable electrolysis are capable of multi-objective optimization applied to scenarios with carbon constraints, but sticking mechanisms and steam utilization remain unresolved. Ghadi et al. [10] have identified carbon deposition, AI-assisted operating decisions, and real-time heat balances as three major research gaps, requiring the development of large-scale, multi-physics databases.

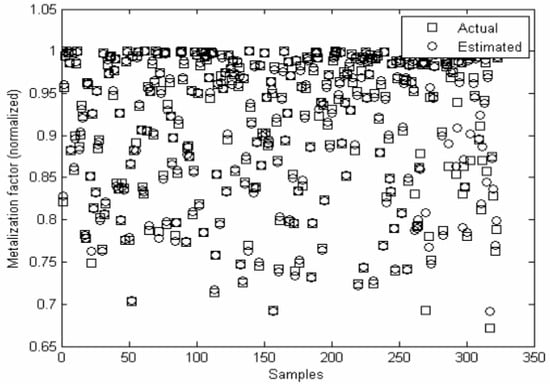

In the first industrial trial, Saif et al. [87] trained a back-propagation neural network (BPNN) soft sensor on seven online variables and recorded real-time metallization predictions within ±2% (Figure 9), enabling closed-loop control. Applying high-resolution sensing and fast algorithms such as VFS and TSSM, digital twin platforms can now reconstruct flow and temperature fields in minutes, delivering on-the-fly “what if” analyses and energy minimization guidance to operators.

Figure 9.

Comparison of actual (mathematical) and ANN model-based estimated metallization factor. From Ref. [87].

Numerical simulation has evolved from early unit-scale continuum models into an end-to-end tool that combines particle-resolved physics, detailed chemistry, radiative heat transfer, and real-time optimization. It now underpins stable furnace operation at high H2 concentrations, variable feed quality, and tight carbon budgets. Further work is required to refine high-temperature sticking and carbon deposition mechanisms, SMR kinetic models, and AI uncertainty quantification to move from “offline design” to true “online adaptive control.”

5. Challenges in Hydrogen-Based Shaft Furnace Simulation and Modelling

Despite the considerable advances in modelling and simulating hydrogen-based shaft furnaces, achieving greater predictive accuracy and industrial relevance faces several critical scientific and engineering challenges. These span every stage of the modelling workflow, from formulating physically rigorous equations and accelerating the numerical solution to ensuring robustness across diverse operating conditions with definitive experimental validation. These limitations have curtailed the full impact of CFD on H2 shaft furnace development and scale-up.

The principal challenges in modelling hydrogen shaft furnaces are identified in Table 10, outlining suitable mitigation strategies that can serve as a roadmap for future work. Each challenge is classified as short-term (1–3 years) or long-term (3–10 years) as a guide to help researchers prioritize their efforts. Short-term goals mainly entail algorithmic refinements or computational upgrades that are readily achievable using existing CFD/DEM software, whereas long-term goals require the development of new in situ instrumentation, multi-scale coupling approaches, or material property databases that are still at low technology readiness levels. The analysis clarifies where immediate progress can be made, and where sustained, collaborative research will be essential.

Table 10.

Key challenges and countermeasures in shaft furnace modelling.

Modelling a hydrogen-based shaft furnace entails closely coupled physicochemical processes, with significant challenges associated with model formulation, parameter acquisition, numerical solution, and result validation. A systematic cataloguing of these obstacles and proposing targeted remedies will help researchers prioritize key issues, avoid redundant efforts, and accelerate overall progress in modelling technology.

5.1. Model Accuracy and Validation

5.1.1. Complex Physicochemical Phenomena

The operation of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces is dominated by the strongly endothermic reduction of Fe oxides; any local heat deficit rapidly develops cold zones that stall reaction. Accurate CFD must close the transient balance between heat supply (hot blast, in-bed burners), heat transfer (gas–solid convection, inter-particle conduction + radiation, gas conduction/radiation) and heat consumption (reaction enthalpy plus sensible heats of both phases). Multicomponent transport in each pellet, molecular and Knudsen diffusion, and possible convection, are coupled with surface kinetics. The pore network evolves continuously, altering porosity, tortuosity, and specific surface, influencing the effective diffusivity and reactive interface. In the presence of CO or CH4, high-T water–gas shift or Fe-catalyzed reforming/cracking alters gas composition and heat effects, amplifying modelling complexity.

5.1.2. Multiphase Flow and Particle Bed Behavior

A hydrogen-based shaft furnace behaves as a moving bed reactor. The charging pattern, wall effects, and buoyancy create porosity gradients and size segregation. The resulting channel flow and stagnant pockets impact gas utilization and reaction uniformity [85]. At a high metallization or near the Fe softening point, DRI pellets soften, stick, and agglomerate, sharply reducing permeability, impeding burden descent with the possible formation of accretions that cause shutdown. The physics of high-T sticking are still poorly quantified, and there is a lack of robust sub-models. Moreover, thermal/mechanical degradation (strength loss, fracture, abrasion) generates fines, shifting the particle size distribution and increasing ΔP, which compromises stability and downstream EAF melting. Capturing these thermo-mechanical effects in continuum CFD represents an on-going challenge.

5.1.3. Uncertainty in Kinetic Parameters

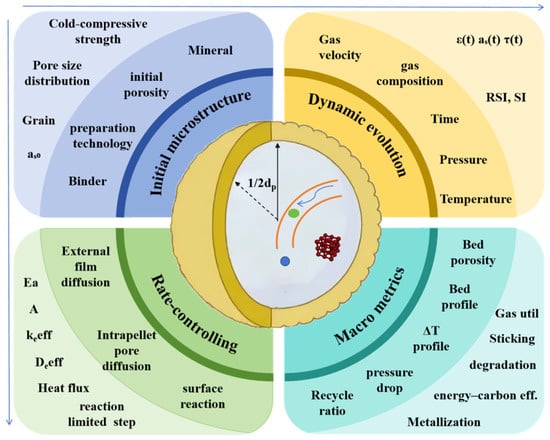

Figure 10 illustrates a multiscale conceptual framework that connects pellet microstructure, dynamic evolution, rate-controlling steps, and the resulting shaft furnace macro-metrics during hydrogen-based direct reduction. The intrinsic kinetic parameters (Ea, A0, reaction order) associated with H2/CO reduction are widely reported in the literature [88,89,90,91,92] and show a dependence on ore origin, preparation, size, gas purity, T-control, and regression method. Furnace-scale predictions are therefore highly sensitive to the chosen kinetic set. Uncertainty in gas-based direct reduction kinetics arises not only from ore-dependent variability and regression scatter in the Arrhenius parameters (activation energy (Ea), pre-exponential factor (A0), and reaction order), but also from the evolving pellet microstructure. Key descriptors of the initial microstructure, including porosity (ε, typically 0.35–0.42), specific internal surface area (as), grain size, and low-temperature compressive strength, collectively govern the effective diffusivity (Deff) and effective reaction rate constant (keff). As temperature and reduction progressively increase, pore coalescence, reduction degradation, and metallic iron whisker growth first increase ε and subsequently diminish it, shifting the rate-controlling mechanism from surface reaction to intra-pellet diffusion. This micro-to-macro transition ultimately modulates furnace-scale performance indicators, including the degree of reduction, gas utilization efficiency and the width of the sticking temperature window. A unified, high-precision kinetic database that accommodates this diversity is required, and there is no consensus scheme that embeds microstructural evolution into macroscopic kinetics.

Figure 10.

Multiscale coupling of pellet kinetics and shaft furnace performance. RSI: reduction swelling index; SI: sticking index.

5.1.4. Data Scarcity and Validation Gaps

Pilot and industrial-scale hydrogen furnaces operate at temperatures above 900 °C, the atmosphere is H2-rich, and instrumentation options are limited [8]. In terms of laboratory-scale units, in situ data are lacking and difficult to generate with respect to spatially and temporally resolved T, gas composition, reduction degree, and phase velocities under corrosive H2 [93]. Parameters derived based on small samples cannot be extrapolated blindly to plant scale, and scale effects require systematic assessment. This also hampers AI/ML, which demands large, high-quality datasets that are currently unavailable [94].

The bottleneck with respect to accuracy in hydrogen shaft furnace modelling stems from an incomplete understanding of coupled phenomena and a lack of validation data. Progress hinges on tighter experiment–simulation loops: targeted kinetic/pilot tests can supply reproducible parameters and benchmarks, where high-fidelity models should guide experiment design and data extraction. As hydrogen reduction is highly endothermic, accurate models derived for blast furnace or shaft furnace require dedicated constitutive relations or entirely new frameworks to capture hydrogen-specific physics [5].

5.2. Computational Cost and Efficiency

High-fidelity CFD–DEM and multiscale simulations often demand hours to weeks to complete, far exceeding the second-to-minute response required for real-time monitoring and optimization [95]. Future research must strike an optimal balance between physical fidelity and computational speed. On the one hand, parallel algorithms, GPU acceleration, and multigrid solvers should be leveraged to increase numerical throughput [96]. On the other, reduced-order and surrogate models must be developed that deliver near-instant predictions consistent with the governing physics.

5.3. Model Transferability and Industrial Implementation

5.3.1. Adaptability to Diverse Ores and H2 Feeds

Industrial hydrogen-based shaft furnaces must process ores and pellets with widely varying Fe grade, gangue (SiO2 and Al2O3), porosity, particle size distribution, reducibility, and softening–melting behavior [97]. Such variability influences reaction pathways, bed permeability, and sticking propensity, but most published models are calibrated for a single ore under fixed conditions. In order to achieve broader generalization, future frameworks must express the ore descriptors explicitly (e.g., pore network metrics, gangue chemistry) rather than lumping them within the fitted rate constants.

Hydrogen supply is equally heterogeneous, including “green” electrolysis H2, “blue” carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS)-coupled reforming H2, and transitional “grey” or by-product streams that contain CO, CO2, CH4, or N2 [98]. These impurities shift gas potential, trigger side reactions, and alter transport properties. Such effects should be quantified systematically and incorporated in the kinetic, thermodynamic, and transport sub-models. Current CFD codes seldom offer true plug-and-play flexibility: A change in ore or gas typically mandates fresh parameter optimization or code modification, raising costs and delaying industrial uptake [99].

5.3.2. Scale-Up from Laboratory to Industrial Furnaces

Models and parameters based on bench reactors cannot be applied directly to full-scale furnaces without accounting for scale-dependent phenomena. In large shafts, gas maldistribution, particle segregation, and channel flow dominate, whereas wall effects that are prominent in small rigs are negligible. Moreover, the hierarchy of heat-transfer modes (gas–solid convection, inter-particle conduction/radiation, wall conduction) and burden macro-porosity pattern exhibit non-linearly with respect to scale.

Reliable scale-up therefore demands similarity criteria that preserve the governing dimensionless groups. Modelling strategies should draw on scale-specific behavior from first principles rather than empirical tuning. An identification of constitutive laws that are invariant (e.g., intrinsic reaction kinetics) and that exhibit variation (e.g., drag and sticking thresholds) is crucial. Only then can CFD tools offer consistent, predictive accuracy from laboratory tests through pilot trials to industrial operation.

5.4. Process-Specific Challenges

5.4.1. Heat Supply and Temperature Homogeneity

In the endothermic H2 reduction of Fe oxides, continuous operation demands sufficient heat to balance reaction enthalpy and sensible warming while maintaining an isothermal reduction zone. Optimal furnace design must integrate hot gas pre-heating, tailored tuyere layouts (number, position, and angle), and, if necessary, internal plasma or electrical heaters. Accurate CFD must resolve these coupled heat-transfer paths to prevent cold pockets or hotspots that hinder reduction efficiency.

5.4.2. Pellet Sticking and Degradation

At temperatures above 600–700 °C and high metallization, freshly formed Fe surfaces promote DRI softening, sticking, and agglomeration, particularly under high local load or temperature peaks. Sticking serves to lower bed permeability, disrupting gas flow and potentially generating significant accretions that halt production [85]. Thermal stress and phase-change strain weaken ore particles, causing breakage, abrasion, and fine generation, which affect porosity and pressure drop.

5.4.3. Refractory and Metallic Component Durability

Operation at temperatures >900 °C in H2-rich, H2O-containing atmospheres accelerates hydrogen embrittlement, high-T creep, oxidation/reduction of alloys, and chemical erosion of refractories. This degradation shortens productive life, raises maintenance costs, and jeopardizes safety. The CFD frameworks should therefore couple thermo-mechanical loads with material corrosion kinetics to accurately predict wear rates and guide the selection of H2-resistant linings and metallic components.

6. Future Development Directions

Modelling of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces is rapidly progressing in terms of higher accuracy and enhanced computational efficiency. The priority research topics, key enabling technologies, and target breakthroughs are given in Table 11, providing a clear roadmap for future R&D efforts.

Table 11.

Future research directions and challenges in blast furnace simulations.

Given the significant increases in computing power, researchers [100,101,102] are capable of converging fluid flow, heat transfer, chemical kinetics, particle mechanics, and electromagnetic effects into unified multi-physics frameworks. Deep integration of mesoscopic LBM with conventional DEM/FEM/FVM [103,104,105] ensures numerical stability in complex pore geometries and nonlinear boundaries while exploiting GPU parallelism to deliver quasi-real-time solutions [103] for giga-cell meshes containing millions of particles. Phase-field methods, which treat multiphase interfaces using continuous-order parameters, can now resolve [106,107] grain growth, pore rearrangement, and metallic-iron nucleation in iron-oxide pellets, clarifying how microstructural evolution modulates macroscopic activation energy and diffusion flux. In parallel, next-generation DEM, equipped with adjacency-list rebuilding, sub-second contact search, and super-quadric descriptors for non-spherical particles, facilitates extended high-temperature sticking–breakage coupling for 106-particle domains. These capabilities can generate a single numerical platform to capture the nonlinear interaction of gas-phase turbulence, solid packing, interfacial mass transfer, and endo-/exothermic reactions, and provide first-principles guidance to inform furnace geometry, injection strategy, and burden management [78].

Artificial intelligence has developed from “black-box prediction” and now represents a hybrid physics–data paradigm. Deep neural networks combined with genetic algorithms or reinforcement learning can predict temperature fields, metallization, and gas utilization within seconds and inform optimal gas flow, nozzle temperature, and charging patterns in closed-loop control [108]. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) represent a powerful machine learning approach that embed conservation laws in the loss function, combining physical constraints with high-dimensional nonlinear fitting and significantly improving the reliability of extrapolation [8]. In order to satisfy the requirement of the steel industry for interpretability, explainable AI (XAI) provides feature visualization and sensitivity ranking, demonstrating model decision pathways and latent risks [109]. Bayesian inference, polynomial chaos, and Monte-Carlo propagation, as advanced techniques, quantify uncertainty arising from ore-grade variability, sensor error, and model simplification, delivering confidence intervals rather than single-point forecasts [110].

A successful deployment of these algorithms necessitates breakthroughs in high-temperature in situ sensing (optical fiber, ultrasonic, and electromagnetic probes) to generate real-time, multi-dimensional images of furnace temperature, gas composition, and burden deformation. The provision of open-access databases and benchmarking platforms is critical in sharing high-quality validation data, avoiding redundant effort [94]. The application of high-fidelity models can then execute rapid parameter sweeps for staged gas feeding, pulse injection, and cascade heat recovery, enabling optimization and failure-boundary analysis for frontier concepts such as plasma-assisted hydrogen reduction [111]. Utilization of the triad of fine-scale mechanistic models, hybrid intelligent algorithms, and the availability of reliable experimental data will deliver advanced hydrogen shaft furnace simulation. This will offer plant-scale, second-level responsiveness without sacrificing engineering accuracy, serving as a core decision tool for large-scale green-steel deployment and maximal carbon abatement.

7. Conclusions

This review has surveyed recent progress, spanning laboratory studies and industrial practice, in multi-scale numerical modelling and process optimization for hydrogen-based shaft furnaces. The main findings are as follows:

Recent research converges toward a multi-scale, complementary modelling framework for hydrogen-based shaft furnaces. The hierarchical toolkit reviewed in this work spans macro-scale porous medium CFD, meso-scale TEM approaches, and micro-scale CFD–DEM simulations. When used in combination, these methods are capable of reproducing furnace-scale temperature, pressure drop, and metallization distributions with good fidelity, while enabling efficient design exploration and mechanistic analysis at the particle scale.

Simulation-driven design across model types, central annular distributors, dual hydrogen inlets, and graded “V/W/Z” burden profiles consistently (i) suppresses dead-zone volume to negligible levels, (ii) increases metallization by 4–6%, and (iii) adds <0.2 kPa t−1 to pressure drop, where the reduction zone should be maintained at 1120–1200 K.

Unresolved issues include (i) high-temperature sticking and carbon deposition mechanisms, (ii) uncertainty in H2/steam reforming kinetics, (iii) insufficient plant-scale validation data, and (iv) the excessive cost of high-fidelity solvers. These bottlenecks serve to constrain model reliability under conditions of hydrogen enrichment and feed variability.

Key breakthroughs necessitate effectively coupled multi-physics models, advanced mesoscale methods, AI-accelerated surrogates with rigorous uncertainty quantification, high-throughput experimentation, and open-access databases. These developments can enable second-scale prediction, adaptive online control, and widespread industrial deployment.

In summary, numerical simulation has evolved from an academic exercise into an indispensable auxiliary for the design, tuning, and scale-up of hydrogen-based shaft furnaces. Further advances will serve to underpin effective decarbonization and intelligent operation in the steel industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and F.W.; methodology, H.L.; software, B.W.; validation, F.W., X.H., and B.W.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, F.W.; data curation, F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, F.W. and Y.Q.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, X.H. and Y.Q.; project administration, X.H. and H.L.; funding acquisition, F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2024YFB3713900&2024YFB3713902).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yue Yu, Feng Wang, Xiaodong Hao, Heping Liu, Bin Wang, Jianjun Gao and Yuanhong Qi were employed by the company State Key Laboratory for Advanced Iron and Steel Processes and Products, Central Iron and Steel Research Institute Co., Ltd. Authors Yue Yu, Feng Wang, Xiaodong Hao, Bin Wang, Jianjun Gao and Yuanhong Qi were employed by the company Beijing Steel Research Institute of Hydrometallurgy Technology Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| H-DR | Hydrogen-based Direct Reduction |

| DRI | Direct Reduced Iron |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| TFM | Two-Fluid Model |

| DEM | Discrete Element Method |

| HBI | Hot Briquetted Iron |

| NG | Natural Gas |

| COG | Coke Oven Gas |

| SMR | Steam Reforming |

| POX | Partial Oxidation Reforming |

| ATR | Autothermal Reforming |

| DRM | Dry Reforming (with CO2) |

| BF-BOF | Blast Furnace–Basic Oxygen Furnace (integrated route) |

| SF-EAF | Shaft Furnace-Electric Arc Furnace |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| EAF | Electric Arc Furnace |

| BPNN | Back-Propagation Neural Network |

| LBM | Lattice Boltzmann Method |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FVM | Finite Volume Method |

| DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regression |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory (recurrent neural network) |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (hybrid turbulence model) |

| VFS | Volume Fraction Smoother |

| TSSM | Timescale Splitting Method |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| UCM | Unreacted-Core Model |

| SGM | Single Grain Model |

| DO | Discrete Ordinates (radiation model) |

| P1 | First-Order Spherical Harmonics Radiation Model |

| X-ray CT | X-ray Computed Tomography |

| PRM | Random Pore Model |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| HIP | Heterogeneous-computing Interface for Portability |

| RSI | Reduction Swelling Index |

| SI | Sticking Index |

References

- Lüngen, H.B.; Schmöle, P. History, developments and processes of direct reduction of iron ores. In Proceedings of the 8th European Coke and Ironmaking Congress and the 9th International Conference on Science and Technology of Ironmaking, Bremen, Germany, 29 August–2 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ripke, J.; Kopfle, J. MIDREX H2™: Ultimate Low CO2 Ironmaking and Its Place in the New Hydrogen Economy. Direct from Midrex 2017, 3rd Quarter, 7–12. Available online: http://www.midrex.com/wp-content/uploads/Midrex_2017_DFM3QTR_FinalPrint.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yu, S.; Shao, L.; Zou, Z. A numerical study on the process of the H2 shaft furnace equipped with a center gas distributor. Processes 2024, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Guan, X.; Kuang, S.; Yu, A.; Yang, N. A Review on the Modeling and Simulation of Shaft Furnace Hydrogen Metallurgy: A Chemical Engineering Perspective. ACS Eng. Au 2023, 4, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Pang, K.; Barati, M.; Meng, X. Hydrogen-based reduction technologies in low-carbon sustainable ironmaking and steelmaking: A review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2024, 10, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Ghadi, A.; Radfar, N.; Valipour, M.S.; Sohn, H.Y. A Review on the Modeling of Direct Reduction of Iron Oxides in Gas-Based Shaft Furnaces. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2200742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salucci, E.; D’Angelo, A.; Russo, V.; Grenman, H.; Saxen, H. Review on the reduction kinetics of iron oxides with hydrogen-rich gas: Experimental investigation and modeling approaches. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 64, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Kasiri, N.; Rezaei, M. A comprehensive multiscale review of shaft furnace and reformer in direct reduction of iron oxide. Miner. Eng. 2025, 222, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhumaizi, K.; Ajbar, A.; Soliman, M. Modelling the complex interactions between reformer and reduction furnace in a midrex-based iron plant. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 90, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Ghadi, A.; Valipour, M.S.; Biglari, M. CFD simulation of two-phase gas-particle flow in the Midrex shaft furnace: The effect of twin gas injection system on the performance of the reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Vasudevan, N.; Kumar, S. Compendium: Energy-Efficient Technology Options for Direct Reduction of Iron Process (Sponge Iron Plants); The Energy and Resources Institute: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Quatravaux, T. A Graphical Tool to Describe the Operating Point of Direct Reduction Shaft Processes. Metals 2023, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, D.R.; Laborde, M.A. Modeling of counter current moving bed gas-solid reactor used in direct reduction of iron ore. Chem. Eng. J. 2004, 104, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béchara, R.; Hamadeh, H.; Mirgaux, O.; Patisson, F. Optimization of the iron ore direct reduction process through multiscale process modeling. Materials 2018, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechberger, K.; Spanlang, A.; Sasiain Conde, A.; Wolfmeir, H.; Harris, C. Green hydrogen-based direct reduction for low-carbon steelmaking. Steel Res. Int. 2020, 91, 2000110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Chi, Z.; Yuan, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W. Development and application of hydrogen-based direct reduction iron process. Processes 2024, 12, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M.; Brooks, G.; Rhamdhani, M.A. Decarbonisation and hydrogen integration of steel industries: Recent development, challenges and technoeconomic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Babich, A.; Senk, D.; Fan, X. Hydrogen direct reduction (H-DR) in steel industry—An overview of challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Filho, I.R.; Ma, Y.; Raabe, D.; Springer, H. Fundamentals of green steel production: On the role of gas pressure during hydrogen reduction of iron ores. JOM 2023, 75, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Tanaka, H. Future steelmaking model by direct reduction technologies. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. The perspective of hydrogen direct reduction of iron. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravian, G.; Zeraatkar, E. Optimization of sponge iron production in direct reduction plants with the KIPEX method. Int. J. Iron Steel Soc. Iran 2024, 20, 45–52. [Google Scholar]