Abstract

This study employs CFD simulations carried on ANSYS Fluent 2022 R1 (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), to address the design, development, and thermodynamic analysis of a biomass burner, based on mass and energy balances, combustion efficiency, flame temperature, and thermodynamic properties. The prototype incorporates a flow deflector located before the combustion chamber. This component improves the air-fuel mixture to maximise thermal efficiency and minimise pollutant emissions. The burner is specifically designed to use sawdust as fuel and is intended for industrial applications such as heating or drying processes. The integration of the flow deflector results in uniform, complete combustion, achieving 90% thermal efficiency and an adjustable thermal power output of 0–100 kW. Compared to conventional burners, this design reduces CO emissions by 20% and NOx emissions by 15%, demonstrating significant environmental improvements. The design methodology is based on mass and energy balance equations to evaluate combustion efficiency as a function of the stoichiometric ratio, along with experimental testing. These experimental tests were conducted using an ECOM (America Ltd., Nashua, NH, USA) gas analyser and anemometer. The internal temperature was monitored with a K-type thermocouple (Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA). The results confirmed the positive influence of the structural design on thermal performance. The proposed burner aims to maximise heat generation in the combustion chamber, offering an innovative alternative for biomass combustion systems.

1. Introduction

The escalating global energy demand, coupled with growing environmental concerns about the combustion of fossil fuels, underscores the imperative for sustainable energy solutions [1]. In this context, biomass, an abundant renewable energy source, emerges as a promising alternative, particularly for thermal applications [2]. The efficient utilisation of biomass can significantly contribute to energy security and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [3]. However, realising the full potential of biomass, especially in industrial applications, requires the development of advanced combustion technologies to overcome its inherent heterogeneity. Among various biomass feedstocks, forest by-products, such as sawdust, represent an abundant resource [4,5,6]. Modern energy conversion technologies offer pathways to increase the value of sawdust utilisation beyond heat production [7]. Despite its caloric potential, the direct combustion of raw sawdust in conventional burners often results in inefficiencies, incomplete combustion, and elevated pollutant emissions due to its variable moisture content [8,9]. Existing biomass burner technologies have made strides in separating air into primary and secondary streams to enhance gasification and complete combustion and in modifying conventional designs to process multiple fuel inputs [10]. Some designs incorporate pre-combustion chambers to optimise pulverised biomass combustion, drawing parallels with pulverised coal technology, or focus on reducing specific harmful emissions, such as nanoparticles [11,12].

While these advancements are notable, a persistent challenge remains developing burners that simultaneously achieve significantly higher thermal efficiencies while minimising a broader range of pollutant emissions. The quest for burners that ensure comprehensive combustion performance across these critical parameters remains a focal point of contemporary research [13]. To overcome these limitations, an approach integrating advanced computational and analytical tools is indispensable. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a suitable numerical methodology for simulating heat transfer and chemical reactions in combustion systems [14,15]. Mass and energy balances, together with thermodynamic analysis, enable the quantification of thermal efficiency and the improvement of energy recovery processes [16]. Such analysis aims to obtain the maximum possible energy from the fuel while minimising waste heat. This work addresses the aforementioned elements by applying CFD to investigate the burner’s performance and improve combustion stability, thereby maximising thermal efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

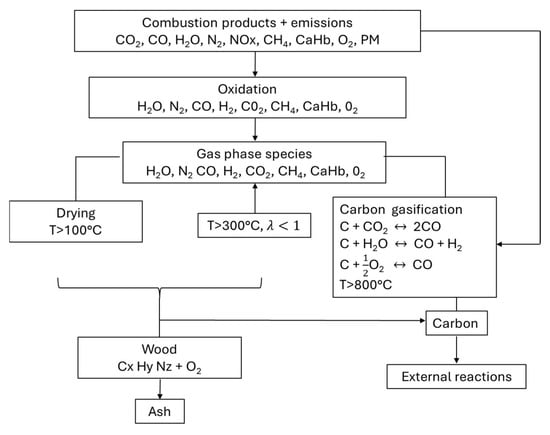

The global requirements for sustainable energy, coupled with the imperative to mitigate climate change, underscore the critical role of biomass as a renewable energy source [17]. However, harnessing the energy potential of biomass also requires combustion technologies that optimise efficiency and minimise environmental impact [18]. This section describes the theoretical frameworks involved in the biomass burner, integrating CFD and thermodynamic analysis [19,20]. Biomass combustion is a complex thermochemical process involving drying, pyrolysis, char oxidation, and gas-phase combustion, ultimately converting organic material into heat, ash, and gaseous products [21]. While its fine particulate nature can enhance reaction kinetics due to increased surface area, it also poses challenges related to complete combustion and particulate matter emissions [22]. Figure 1 shows the relation of the main reactions involved in the combustion of biomass. Modern biomass burners often employ sophisticated air staging strategies, separating primary air for gasification from secondary air for complete combustion of volatiles, which has been shown to improve combustion performance [10]. The introduction of a pre-combustion chamber, a concept adapted from pulverised coal combustors, can further enhance efficiency by providing an optimised environment for initial fuel conversion before the main combustion stage, thereby improving fuel flexibility and stability [11]. These reactions occur within the burner, and its geometric shape can significantly influence combustion efficiency. Modifications to conventional burner designs are continuously explored to accept multiple fuel types and increase efficiency [12].

Figure 1.

Biofuel combustion reactions.

Effective heat transfer mechanisms, often employing design features such as heat storage or specialised heat exchangers, are integral to maximising the system’s overall thermal efficiency [23].

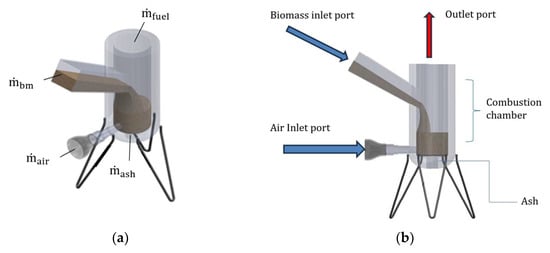

2.1. Mass Balance

The mass balance parameters for the burner include the biomass mass flow rate (), the elemental composition of the biomass (C, H, O, N), the air mass flow rate (), the air composition (O2, N2), and the mass flow rates of combustion products (), which include CO2, H2O, N2, and other gases [24]. Figure 2a shows the Computer Aided Design (CAD) model of the proposed biomass burner, indicating the locations of the inlet and outlet ports. The burner was constructed from carbon steel due to its thermal and mechanical properties, which are suitable for the experiment. The balance elements are included in Equation (1). Figure 2b shows the location of the inlet ports for the biomass and the air. The boiler outlet is connected to atmospheric pressure on the top side of the combustion chamber.

where is the mass flow rate of the sawdust (kg/s). and is the mass flow rate of the ash (kg/s). The stoichiometric condition used in this study was established based on the elemental composition of sawdust biomass (C–H–O–N basis) and validated using both theoretical combustion equations and experimental flue gas measurements.

Figure 2.

Biomass burner configuration, (a) CAD model and (b) location of inlet and outlet ports.

2.2. Energy Balance

The energy balance analysis considers both incoming and outgoing energy to quantify energy losses and their impact on the gasification process’s overall efficiency.

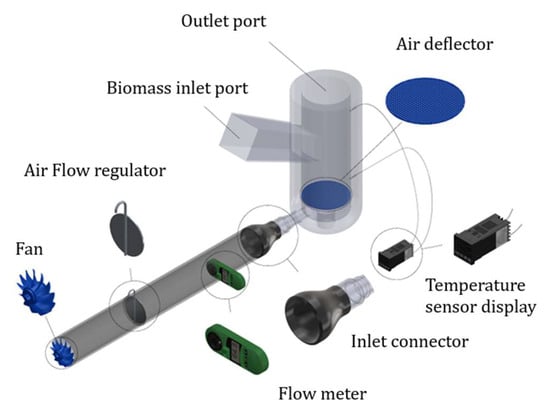

In this case, represent the elemental composition of the biomass. The efficiency equation can be expressed in the form of:

Several articles discuss how energy balances are used to understand system behaviour, predict emissions, and improve efficiency. For instance, [25] highlights that mass, energy, and exergy flows are analysed across main components such as the combustion chamber and boiler. In [26], they applied a model to simulate coupled multi-physical phenomena in combustion and evaluate the boiler’s energy performance. Mamatkulova and Uzakov [27] also discuss thermal balance calculations for biomass pyrolysis plants. These findings reinforce the relationship among the elements shown in Figure 1, which represent the fundamental balances in the biomass burner. The combustion evaluation of biomass is the central focus of this study, with burner design a critical component for achieving efficient, clean combustion. The evaluation process includes a detailed analysis of combustion efficiency, emission levels, and temperature distribution within the burner. To support this, techniques such as flue gas analysis to measure CO2, CO, NOx, and SOx, and thermographic imaging are employed to visualise temperature profiles. Although secondary in focus, the burner design is vital to the successful assessment of combustion. The selection of appropriate materials is essential, favouring those with high resistance to elevated temperatures and corrosion. The mass-flow air deflector is a key feature for improving the air-fuel mixture. Experimental measurements were carried out using a flue gas analyser (ECOM B+, ECOM America Ltd., Nashua, NH, USA) to determine O2, CO2, CO, and excess air. Internal temperature measurements were obtained using K-type thermocouples (Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA). Inlet air velocity was measured using a digital anemometer (ECOM America Ltd., Nashua, NH, USA). Figure 3 shows the elements and accessories designed to construct the prototype.

Figure 3.

Biomass burner components.

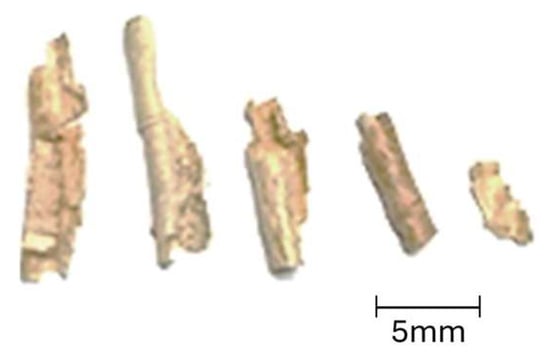

As an energy vector, the biomass is mainly composed of fine particles with high cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content and low levels of carbon, hydrogen, and ash. Key considerations also include moisture content, low density, and particle size, which directly affect the heating value. For this study, the particles range in length from 4 to 8 mm. This morphology, along with its low moisture content, varies with resin composition across different sources (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sawdust size variations.

3. Numerical Validation

CFD has emerged as an indispensable tool for the design and analysis of complex combustion systems. they provide detailed insights into fluid flow, heat transfer, and chemical reactions within the burner, allowing for virtual prototyping and performance prediction before physical construction [28]. This methodology enables engineers to visualise and analyse phenomena such as turbulent mixing, flame propagation, and pollutant formation, which are often challenging to observe experimentally [29,30]. By simulating various design parameters, such as burner geometry, air inlet configurations, fuel feeding mechanisms, and studying their impact on combustion behaviour. While CFD offers significant advantages in cost-effectiveness and the generation of detailed data, its accuracy depends on the fidelity of the physical and chemical models employed and on the computational mesh resolution [31].

Input Parameters

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent 2022 R1 (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA). The CFD model enabled the analysis of airflow patterns, temperature distribution, and species concentration within the combustion chamber. Table 1 shows the parameters considered in the data input to configure the CFD simulation conditions. They include fuel properties, inlet conditions, boundary conditions, and simulation parameters. Together, these parameters define the simulation environment for analysing combustion behaviour.

Table 1.

Input parameters.

4. Numerical Results

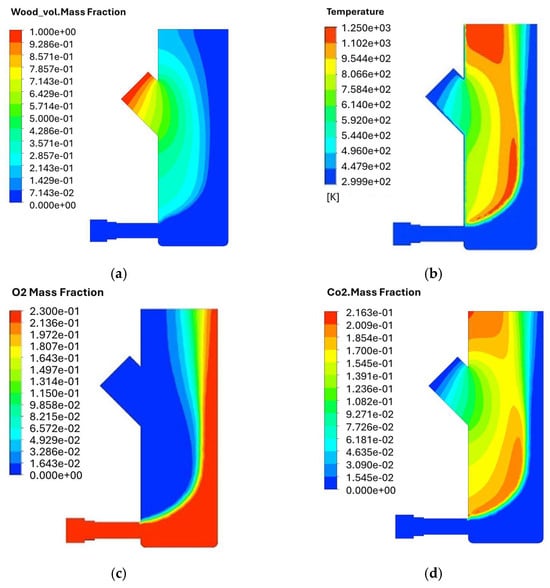

In the computational simulation shown in Figure 5a, the biomass mass fraction gradually decreases from the burner inlet, where the fuel is injected, toward the flame zone, where combustion occurs, indicating complete combustion.

Figure 5.

Contour plots of the simulation results. (a) Biomass mass fraction; (b) Temperature; (c) Oxygen mass fraction; (d) Carbon dioxide mass fraction.

The recorded values of 10.5% CO2 and 2.8% O2 closely approach the ideal stoichiometric combustion conditions, suggesting that the process operates within the acceptable parameters for efficient combustion.

A key result is the temperature distribution inside the biomass burner, as shown in Figure 5b. Distinct hot spots and regions of intense heat transfer are identified. A significant temperature gradient is observed within the combustion chamber, with temperatures above 700 °C in the flame zone and a gradual decrease toward the burner walls.

Additionally, the simulation supports the identification of zones where the biomass mass fraction remains high, which are suitable for pyrolysis and fuel ignition, ensuring effective thermal conversion.

The observations and interpretation of CO2 and O2 concentrations are essential for assessing combustion efficiency and emissions, as shown in Figure 5c,d. High combustion efficiency is indicated by a greater CO2 concentration relative to other combustion products, such as CO, within the previously defined stoichiometric parameters. This reflects more complete and efficient combustion, maximising energy efficiency while minimising pollutant emissions. It is particularly important to observe the mixing zone within the biomass burner, where the CO2 distribution helps identify areas where the fuel–air mixture is carried. In a complete and ideal combustion process, all carbon in the fuel is converted to CO2. If the mixture is fuel-rich (oxygen-deficient), incomplete combustion occurs, producing carbon monoxide and soot and reducing energy release. In such cases, CO2 concentration in the main combustion zone will be lower than expected for complete combustion. The CO2 distribution should show a near-zero concentration in the initial mixing zone, indicating rapid fuel oxidation in an idealised case.

As combustion gases progress into the post-combustion zone, the region following the primary flame, where oxidation reactions are completed, the CO2 concentration should increase, approaching the theoretical value for complete combustion of the biomass type used. This indicates that intermediate combustion products are fully oxidised, maximising conversion to CO2, which is essential for high efficiency and low emissions; the air-fuel mixture and temperature are critical to ensure complete conversion.

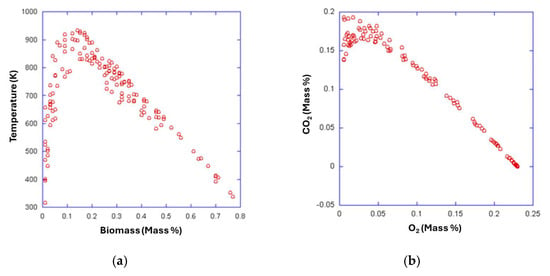

The biomass-temperature and O2–CO2 graphs reveal combustion efficiency and exhaust gas composition. As shown in Figure 6a, the temperature increases as a function of the biomass consumed, with peak temperatures reaching 950 K. In Figure 6b, oxygen is observed to decrease in the flame zone, confirming its active participation in combustion. The extent of oxygen depletion reflects the degree of oxidation taking place. A controlled, efficient decrease in O2 concentration, along with CO2 levels within ideal parameters, indicates effective combustion of biomass into CO2 and heat. In contrast, a rapid or incomplete drop in oxygen may result in CO formation and other products of incomplete combustion, thus reducing overall efficiency and increasing emissions. The graphs presented show the relationships among biomass, oxygen (O2), and carbon dioxide (CO2) during biomass combustion.

Figure 6.

Decrease of components during the combustion, (a) temperature with respect to biomass percentage and (b) CO2 with respect to O2 consumption.

Figure 6a shows that the relationship between biomass mass and combustion temperature is non-linear and constrained by stoichiometric conditions. While increasing the biomass mass (with sufficient oxygen) raises the temperature, this effect plateaus once the stoichiometric point is surpassed, typically near 10.5% CO2 and 2.8% O2, although these values vary with biomass type and operating conditions. Beyond this ideal point, adding more biomass leads to a drop in temperature due to fuel-rich combustion, in which excess fuel absorbs heat without contributing to combustion because of insufficient oxygen. This lowers the overall temperature. In such cases, the burner control system should reduce the fuel feed rate or increase the airflow to maintain the stoichiometric balance and avoid incomplete combustion. If the system fails to correct this, incomplete combustion occurs, producing by-products such as CO and particulates instead of complete oxidation to CO2 and H2O, thereby reducing heat release and combustion efficiency. Figure 6b, shows the dependence of combustion efficiency on oxygen availability. At low O2 levels, combustion is incomplete, promoting CO formation and limiting CO2 production. CO2 reaches its maximum at low oxygen concentrations in cases of incomplete combustion, where biomass carbon is not fully oxidised. As O2 concentration increases, combustion becomes more complete, increasing CO2 production and reducing CO. At the stoichiometric point, oxygen is just sufficient for complete combustion, maximising CO2 and minimising incomplete combustion products. Beyond this point, excess O2 no longer increases CO2, since all available carbon has reacted, as shown in the graph.

The interpretation of CO2 and O2 levels should be related to other variables such as temperature, flow velocity, and the mass fractions of different chemical species. This underscores the importance of closely examining Figure 5 and Figure 6. Evaluating the CO2/O2 concentration relationship enables assessment of combustion efficiency and whether the process operates under stoichiometric or excess air conditions. This approach allows for spatial analysis and visualisation of CO2 and O2 distribution at specific points within the burner. It facilitates comparison with experimental data from a flue gas analyser at the burner outlet. Such validation ensures that emissions remain within acceptable limits.

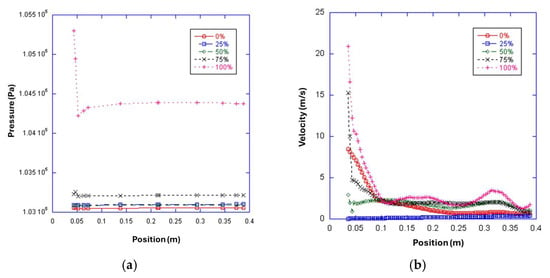

The fundamental design proposal introduced in the biomass burner is the airflow deflector. To evaluate its impact, two burner designs were analysed, as shown in Figure 7a,b: one with the flow deflector and one without. The burner with the deflector improves air–fuel mixing and stabilises laminar flow velocity, producing more complete combustion and reducing emissions. This design enhances heat transfer and flame stability compared to the conventional burner. Both burners underwent rigorous testing using a flue gas analyser to measure CO2, CO, O2, excess air, and combustion efficiency. The analyser samples combustion gases and uses electrochemical or infrared sensors to determine the concentration of individual components. From these measurements, key parameters are derived, including excess air ratio and combustion efficiency. A gas analyser enabled spatial analysis of CO2 and O2 concentrations at specific burner locations, supporting design and improved operational control. Figure 7a shows the pressure drop, and Figure 7b the velocity drop, along the burner with different opening percentages of the flow deflector, measured from the inlet location to the outlet.

Figure 7.

(a) Pressure and (b) velocity drop with different opening percentages of the flow deflector.

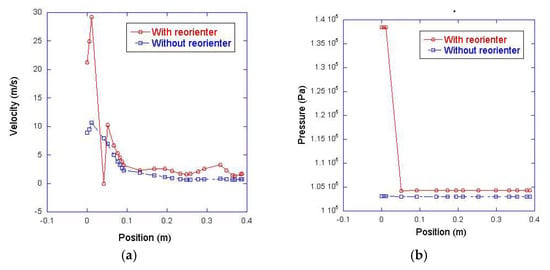

Figure 8a,b illustrate the behaviour of airflow velocity and pressure variation inside the burner, with and without the flow deflector.

Figure 8.

(a) Velocity and (b) pressure drops along the interior of the biomass burner.

In the burner design without the deflector, as shown in Figure 8a, airflow velocity initially decreases but then increases after passing through the inlet zone. However, this increase does not result in a homogenised flow, which may negatively affect combustion efficiency. In contrast, in the burner with the flow deflector shown in Figure 8b, the velocity slightly decreases upon entering the combustion chamber and remains relatively constant throughout the flow path. This behaviour indicates a laminar flow profile, which is ideal for efficient combustion. Compared to the conventional design, the flow deflector-equipped configuration enhances heat transfer and flame stability, thereby improving burner performance. The flow deflector slightly reduces the air velocity upon entering the combustion chamber then maintains a relatively constant velocity.

This indicates a more laminar, stable flow pattern, which is suitable for efficient combustion. In the absence of the flow deflector, pressure exhibits erratic fluctuations, with abrupt increases and drops, resulting in significant pressure loss that compromises proper air guidance through the combustion path.

In contrast, the design with the flow deflector exhibits a stable, uniform pressure field after the air passes through it, creating a more complete and stable combustion process. The theoretical stoichiometric air–fuel ratio corresponds to:

- (a)

- CO2 (dry basis) ranging from 10 to 11.5%,

- (b)

- O2 (dry basis): 2–4%

- (c)

- Excess air ratio (λ): 1.05–1.15

In this study, both CFD simulation and experimental measurements of CO2 ≈ 10.5% and O2 ≈ 2.8% were obtained. These values fall within the stoichiometric regime, validating that the combustion operates close to optimal conditions.

5. Experimental Analysis

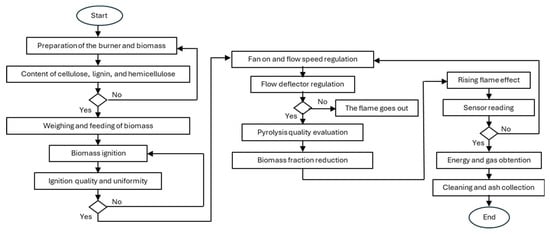

The experimental process shown in Figure 9, begins with biomass preparation. Preference is given to biomass with an adequate lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content, as these characteristics directly influence the thermal behaviour and energy release during combustion. The biomass used in this study, sawdust, has a high content of these components and low carbon, hydrogen, and ash content. Key considerations also include moisture content, low density, and particle size (in this case, 4 to 8 mm in length), which directly affect the calorific value [32,33].

Figure 9.

Experimental procedure.

Experimental Results

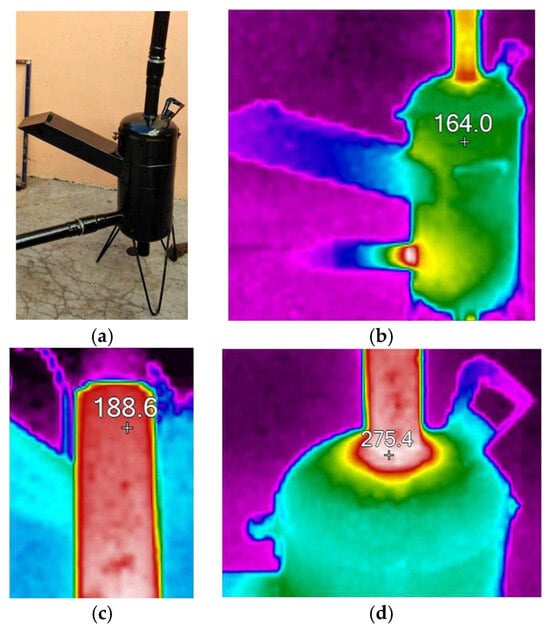

Figure 10a shows a photograph of the final prototype. The burner starts at ambient temperature, approximately 298 K. During the heating and ignition phase, biomass is fed into the combustion chamber, and the air fan is started to initiate ignition. The thermal imaging camera would capture the emergence of initial hot spots, likely in the biomass ignition zone, which would appear as small yellow or orange areas in the contour plot image. At this stage, the energy released by the initial combustion begins to raise the temperature locally.

Figure 10.

Thermograph captions of the burner, (a) finished prototype, (b) temperature on the exterior surface of the burner (164 °C), (c) temperature at the end of the exhaust tube (188.6 °C) and (d) temperature at the exhaust connector (275.4 °C).

As combustion stabilises and the biomass and air feed rates remain constant, the temperature in the combustion chamber rises gradually and steadily. This progressive increase is due to the continuous release of energy from the pyrolysis and combustion reactions of the sawdust. The thermograph shown in Figure 10b indicates a temperature of 164 °C on the external surface of the burner. A temperature of 275 °C was observed on the top side of the burner, as shown in Figure 10d, and at the end of the exhaust tube, the temperature decreases up to 188 °C, as shown in Figure 10c.

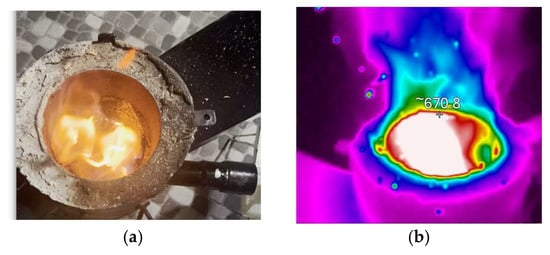

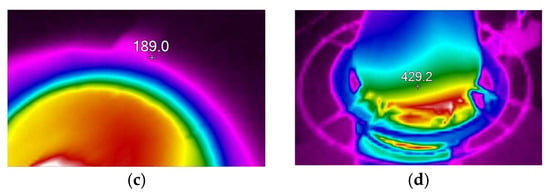

Figure 11a shows the interior of the combustion chamber, loaded with the sawdust and with the flame in the centre. The thermographs reveal that temperatures inside the combustion chamber can reach 700 °C to 750 °C and 189 °C on the external surface, as shown in Figure 11b,c.

Figure 11.

Thermograph captions inside the burner: (a) the flame surrounded by the sawdust inside the combustion chamber, (b) temperature on the core (670.8 °C), (c) temperature on the external surface of the combustion chamber (189 °C), and (d) temperature at the centre of the ash collector (429.2 °C).

The temperature in the burner’s basement ranged from 400 to 550 °C, as shown in Figure 11d. The thermographic visualisation confirms that the burner reaches high operating temperatures and also illustrates how the thermal state is achieved.

The consistent properties of biomass pellets also contribute to this stability, enabling more uniform and predictable combustion characteristics. Table 2 shows related works in which biomass was burned and ≥80% of efficiency was obtained.

Table 2.

Comparison of related works.

In the present study, 90% efficiency was achieved under the CFD predicted stoichiometric operation (CO2 ≈ 10.5%, O2 ≈ 2.8%), the measured flue gas composition, and the temperature measurement, which exceeded that of conventional biomass burners.

6. Discussion

Future modifications to the burner, such as a diagonal-feed hopper and an internal air guide, can enhance the air–fuel mixing and maximise heat transfer efficiency. Both CFD simulations and practical testing on a working prototype validated the design and allowed performance assessment. The results revealed stable combustion temperatures, with emissions falling within stoichiometric limits, with CO2 ≈ 10–11% and O2 ≈ 2–3%. The temperature in the combustion chamber exceeds 700 °C. At this temperature, complete oxidation of volatiles, improved heat transfer, and reduced tar formation are ensured. The internal flow deflector produced a homogeneous airflow distribution, a reduced turbulence intensity, and a stable laminar-to-transitional flow regime. This biomass burner offers adjustable thermal output, ranging from low to high capacity, and adapts to various demands across the energy sector. It provides a versatile solution for heat generation, supporting the diversification of energy sources and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. It is suitable for integration into industrial processes that require thermal energy. The recorded temperatures significantly exceeded the 400–550 °C typical of conventional biomass burners. Other challenges arise for the proper implementation of these technologies; for example, from the technical point of view, the quality of the sawdust, which has a direct relation with the combustion process. On the socioeconomic side, the proper and consistent collection of sawdust can directly affect wood extraction and the internal processes of industrial sawmills. It also creates challenges for the logistics of sawdust treatment, storage, and transportation. Future development and optimisation works can be carried out in all these fields related to biomass processing.

7. Conclusions

This technology supports scalability for low-, medium-, and large-scale applications, presenting an efficient and sustainable alternative in the industrial sector. Higher combustion temperatures improve thermal efficiency and reduce pollutant emissions, contributing to a cleaner energy future. Its hybrid capability enables co-firing biomass with hydrocarbons such as natural gas or Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), providing flexibility and adaptability across different fuel types with high average heating values. This makes the burner an effective alternative for steam generation in the energy sector. The use of CFD combustion simulation enables detailed analysis of the process, including CO2 and O2 concentrations, to evaluate the performance of the biomass burner. Areas for improvement focus on maximising CO2 and minimising CO by adjusting airflow to avoid oxygen excess or deficiency and on correlating data from CO2, O2, temperature, velocity, and additional species to provide a comprehensive diagnosis. This will enable the identification of inefficiencies and support optimisation of burner design, biomass selection, and operating conditions, resulting in cleaner, more efficient combustion with lower emissions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.G.-F. and J.M.S.-P.; Methodology, A.G.-F.; Resources, J.M.S.-P.; Formal analysis, L.A.F.-H. and R.R.-B.; Writing—review and editing, L.A.F.-H. and R.R.-B.; Supervision, J.M.S.-P. and A.Z.-S.; Validation, A.Z.-S. and R.O.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN) under SIP projects numbers: 20254750, 20253687 and 20254255.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The Authors acknowledge the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN) and the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) for their contribution to the development of this academic research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Enthalpy of the incoming air | |

| Enthalpy of the outgoing gas | |

| HHV | Higher heating value |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| Lower heating value of the fuel | |

| mc | Mass of completely burned fuel |

| mf | Total mass of fuel supplied |

| Lower heating value of the generated gas | |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| Heat loss through ash | |

| Heat loss to the environment | |

| Qpotential | Potential energy of the fuel |

| Qreleased | Energy released through combustion |

References

- Pandey, A.K.; Gupta, A.; Bijalwan, P.; Sayal, A. A Review of the Determinants and Barriers to Renewable Energy Utilization in Driving Economic Growth. In Rethinking Resources; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 315–333. [Google Scholar]

- Muneer, T.; Dowell, R. Potential for Renewable Energy–Assisted Harvesting of Potatoes in Scotland. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; Magdalena, R.; Alofaysan, H.; Hagiu, A. The Impact of Green and Energy Investments on Environmental Sustainability in China: A Technological and Financial Development Perspectives. Environ. Model. Assess. 2025, 30, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehman, N.; de León, A.; Quintero Torres, I.N.; Vallejos, M.E.; Area, M.C. Lignocellulosic Agro-Forest Byproducts as Feedstock for Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing Filaments: A Review. Fibers 2025, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Abdelaal, A.H.; Mroue, K.; Al-Ansari, T.; Mackey, H.R.; McKay, G. Biochar from Vegetable Wastes: Agro-Environmental Characterization. Biochar 2020, 2, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Sinha, A.; Chaubey, K.K.; Hariharan, S.; Dayal, D.; Bachheti, R.K.; Bachheti, A.; Chandel, A.K. Second-Generation Bio-Fuels: Strategies for Employing Degraded Land for Climate Change Mitigation Meeting United Nation-Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso-Boateng, E.; Achaw, O.-W. Bioenergy and Biofuel Production from Biomass Using Thermochemical Conversions Technologies—A Review. AIMS Energy 2022, 10, 585–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Cao, Q.; Qin, W. The Evolution of Open Biomass Burning during Summer Crop Harvest in the North China Plain. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2023, 47, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Flores, A.; Gutiérrez-Paredes, G.J.; Merchán-Cruz, E.A.; Zacarías, A.; Flores-Herrera, L.A.; Sandoval-Pineda, J.M. Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis. Processes 2025, 13, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardaś, D.; Wantuła, M.; Pieter, S.; Kazimierski, P. Effect of Separating Air into Primary and Secondary in an Integrated Burner Housing on Biomass Combustion. Energies 2024, 17, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laphirattanakul, P.; Charoensuk, J.; Turakarn, C.; Kaewchompoo, C.; Suksam, N. Development of Pulverized Biomass Combustor with a Pre-Combustion Chamber. Energy 2020, 208, 118333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piawanich, K.; Aggarangsi, P.; Moran, J. Modifications of SME Biomass Boiler for High Efficiency Multi-Fuel Input. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Green Energy for Sustainable Development (ICUE), Phuket, Thailand, 24–26 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeq, A.M.; Homod, R.Z.; Hasan, H.A.; Alhasnawi, B.N.; Hussein, A.K.; Jahangiri, A.; Togun, H.; Dehghani-Soufi, M.; Abbas, S. Advancements in Combustion Technologies: A Review of Innovations, Methodologies, and Practical Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, C.A.; Porteiro, J.; Varela, L.G.; Chapela, S.; Patiño, D. Three-Dimensional CFD Simulation of a Large-Scale Grate-Fired Biomass Furnace. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 198, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.A.; Martín, R.; Collazo, J.; Porteiro, J. CFD Steady Model Applied to a Biomass Boiler Operating in Air Enrichment Conditions. Energies 2018, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghi, M.A.; Baniasadi, E.; Genceli, H. Thermodynamic Assessment of an Innovative Biomass-Driven System for Generating Power, Heat, and Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 75, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğdu, A.; Dayi, F.; Yanik, A.; Yildiz, F.; Ganji, F. Innovative Solutions for Combating Climate Change: Advancing Sustainable Energy and Consumption Practices for a Greener Future. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpeh, M.; Lotfollahi, A.; Moghimi, M.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Combustion Optimization of Various Biomass Types to Hydrogen-Rich Syngas: Two-Stage Pyrolysis Modeling, Methane Addition Effects, and Environmental Impact Assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 133, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bermúdez, C.; Chapela, S.; Gómez, M.A.; Porteiro, J. CFD Simulation of a 4 MW Biomass Grate Furnace Using an Eulerian Fixed-Bed Model: Validation of in-Bed and Freeboard Results. Fuel 2025, 387, 134378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.; Teixeira, S.; Teixeira, J.C. Development of a CFD Model to Study the Fundamental Phenomena Associated with Biomass Combustion in a Grate-Fired Boiler. Processes 2025, 13, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, N.A.; Mohd Yusoff, M.H.; Ahmad Termezi, M.F.; Azmi, N. Sustainable Valorization of Agricultural Biomass: Progress in Thermochemical Conversion for Bioenergy Production. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2025, 19, 2662–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J.; Wasilewski, J.; Zając, G.; Kuranc, A.; Koniuszy, A.; Hawrot-Paw, M. Evaluation of Particulate Matter (PM) Emissions from Combustion of Selected Types of Rapeseed Biofuels. Energies 2022, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, G.; Bennett, N.S.; Luo, Z.; Munir, A.; Islam, M.S. Heat Transfer Enhancement in Heat Exchangers by Longitudinal Vortex Generators: A Review of Numerical and Experimental Approaches. Energies 2025, 18, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.; Mahu, R.; Ion, I.V.; Rusu, E. A Mathematical Model of Biomass Combustion Physical and Chemical Processes. Energies 2020, 13, 6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.A.F.; Tarelho, L.A.C.; Sobrinho, A. Mass, Energy and Exergy Analysis of a Biomass Boiler: A Portuguese Representative Case of the Pulp and Paper Industry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 152, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameri, F.; Delacourt, E.; Morin, C.; Schiffler, J. 0D Dynamic Modeling and Experimental Characterization of a Biomass Boiler with Mass and Energy Balance. Entropy 2022, 24, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzakov, G.; Mamatkulova, S.; Ergashev, S. Thermal Mode of the Condenser of a Pyrolysis Bioenergy Plant with Recuperation of Secondary Thermal Energy. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 411, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.; Van Liew, J.; Turoski, N.; Baysa, M.; Han, Y.-L. Utilizing Computational Modeling to Aid the Development of a Wearable Soft Robot for Finger Rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronic Systems (ICAMechS), Toyama, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Marchelli, F.; Hou, Q.; Bosio, B.; Arato, E.; Yu, A. Comparison of Different Drag Models in CFD-DEM Simulations of Spouted Beds. Powder Technol. 2020, 360, 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.H.; Darmanto, P.S.; Hariana, H.; Darmawan, A.; Aziz, M.; Juangsa, F.B. Numerical Investigation of Coal-Sawdust Co-Firing in a Carolina-Type Boiler: Power Derating and Emission Analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularski, J.; Li, J. Assessment of Biomass Ignition Potential and Behavior Using a Cost-Effective CFD Approach. Fuel 2024, 361, 130637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, B.; Roy, R.; Rahman, M.S.; Raynie, D.E. Extraction and Depolymerization of Lignin from Pine Sawdust and Pistachio Shells. Biomass 2022, 2, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.K.; Thakur, L.S.; Shankar, R.; Mondal, P. Pyrolysis of Wood Sawdust: Effects of Process Parameters on Products Yield and Characterization of Products. Waste Manag. 2019, 89, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Podunavac, J.; Tomić, M.; Anđelković, A.; Kljajić, M.; Živković, P. Optimizing Flue Gas Recirculation for Enhanced Efficiency in Biomass-Fired Boilers: A Comprehensive Study. In Proceedings of the SimTerm Proceedings 2024—Zbornik Radova, Niš, Serbia, 22–25 October 2024; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, I.; Dović, D.; Filipović, P. Numerical and Experimental Methods in Development of the Novel Biomass Combustion System Concept for Wood and Agro Pellets. Energy 2021, 231, 120929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holubcik, M.; Nosek, R.; Jandacka, J. Optimization of the Production Process of Wood Pellets by Adding Additives. Int. J. Energy Optim. Eng. 2012, 1, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.