Abstract

The safe disposal of high-level radioactive waste (HLW) is a significant challenge in the nuclear industry. As the buffer backfill material for deep geological disposal engineering barriers, the shrinkage characteristics of bentonite–sand mixtures are critical to the long-term stability of repositories. This study systematically conducted drying shrinkage tests using an improved thin-film technique under varying sand contents Rs (0–50%), salt solution concentrations (0–1.5 mol/L), and ion types (Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl−, SO42−). The mechanisms of the effects of sand content and salt solutions on the shrinkage behavior of bentonite were revealed based on the results. In addition, the rationality of the MCG-B model in simulating the shrinkage characteristics of mixtures was also discussed. The results show that a sand content of 30% is the minimum sand content for inhibiting the shrinkage behavior of bentonite–sand mixtures observed in this work: below this ratio, bentonite dominates the shrinkage process, and samples are prone to cracking due to uneven matrix suction; above this ratio, quartz sand forms a rigid skeleton that significantly inhibits volume shrinkage and accelerates water evaporation. Salt solutions suppress shrinkage by compressing the thickness of the diffuse double layer and inducing ion crystallization. Higher cation concentrations and valences (Mg2+ > Na+ > Ca2+) enhance the inhibitory effect. Crystalline salts such as Na2SO4 cause measurement deviations in water content due to hydration and delay the shrinkage process. However, NaCl solutions effectively inhibit shrinkage with minimal impact on shrinkage time. Fitting results with the MCG-B model (Coefficient of determination > 0.97) demonstrate that the MCG-B model can empirically describe the results of thin-film technique experiment, though the model’s prediction accuracy decreases for the residual shrinkage stage at high sand contents (>40%). This study provides a theoretical basis for optimizing buffer material proportions and curing processes, with significant implications for the long-term safety of HLW repositories.

1. Introduction

High-level radioactive waste (HLW) generated from nuclear energy is highly radioactive, toxic, and possesses a long half-life, presenting a significant environmental hazard. With the rapid development of the nuclear industry, the amount of HLW requiring long-term and reliable isolation from the human environment continues to increase [1,2]. Currently, the deep geological disposal method is internationally recognized as the most effective option for the safe disposal of nuclear waste. This method involves burying HLW in stable geological formations 500 to 1000 m underground and constructing a multi-barrier system to permanently and effectively prevent the leakage and migration of radioactive isotopes [3,4,5]. Engineered barriers, as a crucial component of the multi-barrier system, can effectively maintain the structural stability of the disposal site, prevent groundwater infiltration, inhibit the migration of radioactive isotopes, and conduct and diffuse nuclear radiation heat [6]. Bentonite has been widely adopted by many countries as the primary buffer backfill material for constructing engineered barriers due to its low permeability, good adsorption properties, and high swelling potential [7]. However, due to disadvantages including poor thermal conductivity and difficulty in compaction, pure bentonite cannot be used alone in the construction of engineering barriers. Adding aggregates such as quartz sand, pyrite, and zeolite to bentonite and optimizing their ratio can enhance the thermal conductivity and mechanical strength of the bentonite, effectively preventing the leakage of radioactive isotopes without significantly compromising the impermeability and adsorption properties of the bentonite [8,9]. Therefore, it is common practice to employ bentonite–sand mixtures in specific proportions as buffer backfill materials. Improper disposal during the curing, storage, and transportation of the buffer backfill material may result in shrinkage deformation and even cracking, which significantly reduces its barrier effectiveness [10]. During the operation of the disposal site, the combined effects of fluctuating groundwater levels and the residual decay heat from HLW inevitably lead to swelling and shrinkage deformation of the buffer backfill material [11,12]. Furthermore, the soluble salts in groundwater can affect the swelling properties, strength, and hydraulic properties of the buffer backfill material, further affecting the long-term stability of the disposal site [13].

Previous studies have systematically examined the deformation behavior of bentonite; however, research on the performance of bentonite–sand mixtures remains relatively limited. And, the existing research on the volume changes in bentonite–sand mixtures primarily focuses on swelling behavior, with fewer reports on shrinkage characteristics [14,15,16,17]. The shrinkage characteristics of soils are essentially the result of the rearrangement of soil particles and pores under hydraulic forces. During wetting and drying processes, the volume change in soil largely depends on structural pores, with the pore volume increasing during water absorption and decreasing during drying. The relationship between soil volume and water change is usually described by the soil shrinkage characteristic curve (SSCC), and typically follows an “S”-shaped curve across the entire moisture content range. For saturated soils, the shrinkage characteristic curve can be divided into three stages: proportional shrinkage stage, residual shrinkage stage, and zero-shrinkage stage [18,19,20]. However, for undisturbed soils, there is an additional structural shrinkage stage before the proportional shrinkage stage.

The shrinkage characteristics of soil are primarily influenced by the type of clay minerals and the quantity of clay particles [21,22]. In addition, compaction conditions and the number of drying–wetting cycles also have a certain impact on shrinkage characteristics [23,24,25,26]. Studies have shown that soils with higher clay content and plasticity index generally have higher moisture content, which makes them more prone to significant volume shrinkage during the drying process [27]. For clay mixed with quartz sand, the final shrinkage ratio and moisture content decrease with increasing quartz sand content [28,29]. This is because the addition of quartz sand disrupts the continuous matrix formed by clay particles. In addition, the salt content in groundwater may also affect the shrinkage behavior of buffer backfill materials [30,31]. As the concentration of salt solution increases, the final void ratio of bentonite–sand mixtures increases, leading to an increase in the volume in shrinkage limit, thus suppressing shrinkage behavior. The influence mechanisms of sand content and salt solutions on the shrinkage characteristic of bentonite remain unclear in the existing research. In particular, there is a lack of theoretical analysis and studies on how the concentration and type of salt solution suppress shrinkage characteristics in bentonite–sand mixtures. Some researchers have analyzed the shrinkage mechanism of buffer backfill materials from the perspective of particle interactions within the mixture. They suggest that the effects of sand content and salt solution concentration on the shrinkage limit and final void ratio of bentonite–sand mixtures are due to changes in the fine particle content, thereby altering the shrinkage behavior of the mixture [32]. However, this mechanism remains incomplete as it fails to incorporate the analysis of variations in moisture content, and hence, systematic investigation is still required to investigate the effects of sand and saline solutions on the shrinkage characteristic of bentonite.

There are numerous fitting models for the shrinkage characteristic curve, such as the MCG-A model, MCG-B model, GEA model, OH model, and GRO model [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Some of these models, like the MCG-A model, can only fit part of the shrinkage process, and some models have overly complex equations due to the large number of parameters. These characteristics limit their use in related fitting software and research. Currently, widely used and considered highly accurate fitting models include the GRO model and the MCG-B model. The MCG-B model is an improved and refined version of the MCG-A model. This model contains four parameters and is an empirical fitting equation that can fully describe the characteristic curves changes at different shrinkage stages.

This study employed an improved thin-film technique at room temperature (20 °C) to conduct systematic drying shrinkage tests on GMZ bentonite–sand mixtures (Rs = 0–50%) and mixtures containing solutions of varying concentrations of NaCl, Na2SO4, CaCl2, and MgCl2. This comprehensive experimental design allowed for a detailed examination of how sand content and pore water chemistry influenced the shrinkage characteristics and moisture-shrinkage evolution of bentonite–sand mixtures. It also revealed the minimum sand content of 30% for inhibiting shrinkage and the influence of different cation/anion on shrinkage inhibition. Furthermore, this study evaluated and discussed the applicability and limitations of the MCG-B model under high sand content or ion conditions. Compared to previous studies, this study provides a more comprehensive multi-ion dataset under thin-film conditions and offers a theoretical basis for optimizing the curing measures and performance of bentonite–sand mixtures buffer backfill materials, and is of significant importance for the long-term stability of disposal sites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

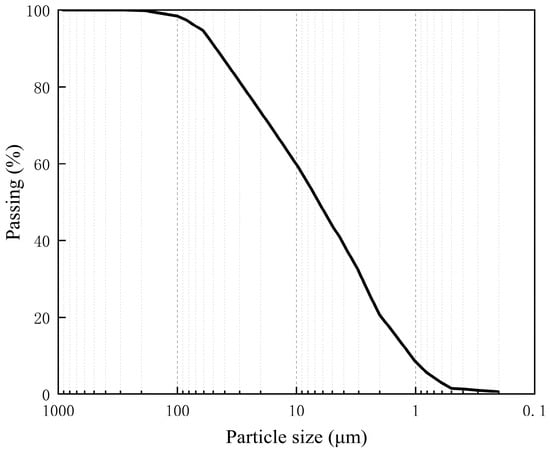

This study utilized GMZ bentonite sourced from Inner Mongolia, China. The primary component of the bentonite is sodium-based, exhibiting a specific gravity of 2.70 and consisting predominantly of clay particles smaller than 5 μm, as illustrated in Figure 1. The basic properties of GMZ bentonite are summarized in Table 1. The quartz sand aggregates employed in this study were obtained from Yongdeng County, Gansu Province, China. These aggregates have a specific gravity of 2.65 and exhibit poor gradation, featuring particle sizes ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 mm.

Figure 1.

Cumulative particle size distribution curve of GMZ bentonite.

Table 1.

Basic properties of GMZ bentonite.

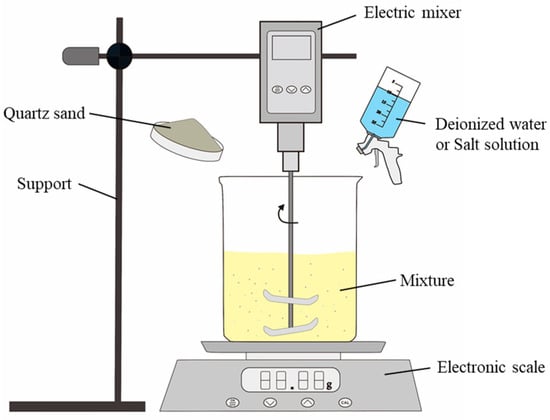

The bentonite and quartz sand were separately oven-dried at 105 °C, then placed into sealed containers containing desiccant to cool to room temperature (20 °C). According to experiment design, the quartz sand was incrementally added to the cooled bentonite, followed by the addition of either deionized water or a saline solution at a predetermined concentration. Quartz sand was added in stages of 20–30 g. Concurrently, deionized water or salt solution water was incrementally sprayed using a spray bottle in increments of approximately 20 mL. In each stage, the mixture was thoroughly stirred with an electronic mixer to ensure uniform distribution of sand and moisture (Figure 2). This process was repeated until the prescribed amount of quartz sand was added, and the mixture reached liquid limit.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of sample preparation.

2.2. Experiment Methods

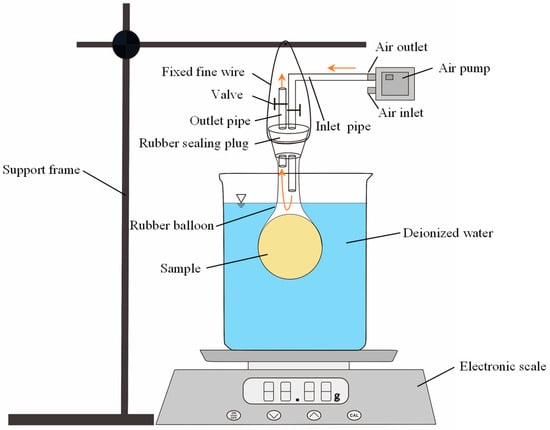

As shown in Figure 3, the experiment employed the thin-film technique based on Archimedes’ principle [39,40]. An elastic, impermeable rubber balloon was selected as the thin-film. A mass of saturated bentonite–sand mixture was accurately weighed and placed into the rubber balloon. Subsequently, the opening of the rubber balloon was sealed using a rubber plug, which was connected to pipes and valves. The valves were closed in order to ensure an airtight environment. The total mass of the rubber plug, rubber balloon, and saturated mixture was measured and recorded. The sealed balloon containing the sample was left undisturbed for 24 h to allow moisture to distribute uniformly throughout the bentonite–sand mixture. Then, the valves were opened, and the air pump was connected to the inlet pipe on the rubber sealing plug. In this way, air could be pumped into the balloon through the inlet pipe, generating a constant airflow rate of 60 L/h around the sample. Due to the humidity gradient, the moisture within the sample evaporated and was discharged through the outlet pipe. During this process, the reduction in moisture content resulted in volume shrinkage of the sample. In addition, the elasticity of the rubber balloon allowed the sample to shrink without mechanical restraint.

Figure 3.

Device of thin-film technique and Archimedes method.

The mass and volume of the sample were measured and recorded every 12 h. The mass measurements were conducted using an electronic scale with an accuracy of 0.01 g. The changes in total mass of the rubber sealing plug, rubber balloon, and sample throughout the experiment were tracked. The volume measurement was conducted based on Archimedes’ principle. A beaker containing a certain mass of deionized water was placed on an electronic scale. The valve on the outlet pipe was closed, and the inlet pipe on the rubber sealing plug was connected to the air inlet of the air pump. In this way, a slight vacuum was applied inside the balloon to ensure close contact between the balloon and the sample. It should be noted that during this process, the air pressure inside the balloon was controlled through the air pump. In order to prevent stress caused by excessive negative pressure, the internal pressure of the balloon was controlled slightly lower than the standard atmospheric pressure. The balloon was then hung on the support frame and immersed into water. The change in the electronic scale reading after immersion was recorded. The experiment was considered terminated when the change rates in sample mass and volume fell below 0.01% per day, indicating stabilization. Finally, the sample was removed from the rubber balloon, dried in an oven at 105 °C to obtain its dry mass.

This study set up 14 groups to investigate the effects of varying sand content ratios (Rₛ), salt solution concentrations (ion concentrations), and ion types on the shrinkage characteristics. The detailed experiment design is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experiment program.

3. Experimental Results

In this study, the shrinkage curve of the samples was described by the relationship between the void ratio (e) and the volumetric moisture ratio (θ). The moisture content (ω), volume (v), and void ratio (e) of the samples at different times were calculated according to Equations (1) to (3). Additionally, the moisture content was converted into volumetric moisture ratio (θ) by Equation (4). This allows for a more intuitive comparison of the changes in volume and the volume of pore water of the bentonite–sand mixture samples under different sand content ratios and water chemistry conditions.

where m1 is the initial mass of the sample at the start of the experiment; m2 is the total mass of the rubber sealing plug, rubber balloon, and saturated mixture; m3 is the change in the electronic scale reading when the sample was immersed into water (water discharge of balloon containing sample); m4 is the change in the electronic scale reading when the rubber balloon (without the sample) was immersed into water (water discharge of balloon without sample); ms is the mass of the sample obtained by drying at 105 °C at the end of the experiment; ρs is the particle density of the bentonite–sand mixture; ρb is the density of the sample during the experiment; and ρw is the density of water.

3.1. The Effect of Rs on the Drying Shrinkage Behavior

3.1.1. Change in Volume

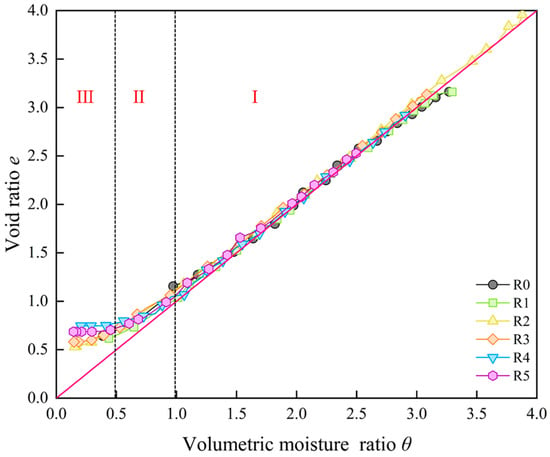

As illustrated in Figure 4, the shrinkage characteristic curves of bentonite samples with varying sand content ratios are presented. It is evident that the shrinkage behavior can be categorized into three distinct stages. During the proportional shrinkage stage (Stage I), as moisture is discharged from the sample, the moisture-filled pores continuously shrink and deform. At this stage, the volume change in the sample equals the volume of discharged moisture. Consequently, the shrinkage curve remains consistently near the saturation line e = θ, indicating that the sample stays saturated throughout this stage. In addition, undisturbed samples often show a structural shrinkage stage at the beginning of the test. During this stage, moisture evaporates but the soil volume stays the same. This behavior was not observed in the present experiment [19]. This suggests that the remolded samples used in the test do not have the inter-aggregate structure found in undisturbed soils or that such structural properties were weakened during the remolding process [41,42]. As the experiment continues, the volumetric moisture ratio of the sample decreases below 1.0, resulting in the volumetric shrinkage of the sample gradually becoming smaller than the volume of expelled water. The shrinkage curve exhibits an upward deviation, progressively distancing itself from the saturation line. This stage is identified as the residual shrinkage stage (Stage II). Subsequently, as the volumetric moisture ratio of the sample continues to decrease and falls to approximately 0.5, the volume of each sample approaches a stable state. Further reductions in moisture content no longer induce additional shrinkage deformation. This stage is referred to as the zero-shrinkage stage (Stage III).

Figure 4.

Shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with different sand content ratios.

Comparing the different shrinkage cures of samples (Figure 4), it can be observed that samples with sand content ratios ranging from 0% and 30% exhibit similar shrinkage behaviors, with final void ratios stabilizing between approximately 0.5 and 0.6. However, samples with sand content ratios of 40% and 50% exhibit significantly weaker shrinkage behavior, and reach the zero-shrinkage stage earlier. The final void ratios of the samples increase markedly to approximately 0.75. The shrinkage characteristic curves of these samples shift slightly upward. The final shrinkage ratio Rf is further defined as

where e0 is the initial void ratio of the sample, and ef is the final void ratio of the sample at the end of the test.

The final shrinkage ratios obtained from tests at different sand content ratios are shown in Table 3. The results show that Rf reaches a critical maximum at sand contents ratio between 20% and 30%, after which it decreases gradually with increasing sand content ratio. It indicates that below 30% sand content ratio, bentonite dominates the shrinkage behavior, whereas above 30% sand content ratios, the shrinkage behavior of bentonite is notably suppressed by sand.

Table 3.

Final shrinkage ratio (Rf) of samples with different sand content ratios.

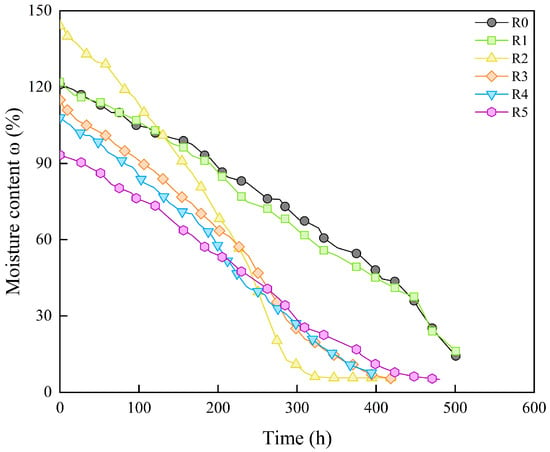

3.1.2. Change in Moisture Content

The variation in moisture content of samples with different sand content ratios over time are plotted in Figure 5. It indicates that the rate of moisture evaporation increases significantly when the sand content ratio exceeds 20%. The curves for samples with sand content ratios ranging from 30% to 50% exhibit a similar trend, suggesting that increasing the sand content ratio within the bentonite promotes moisture evaporation. This characteristic is particularly advantageous in practical engineering barriers applications as it contributes to a reduction in the required curing time for the buffer backfill blocks. Furthermore, it should be noted that the samples with sand content ratios of 0% and 10% fractured into small pieces when the moisture content dropped to about 15%, leading to premature termination of the experiment. As a result, their moisture content does not reach a final stable stage over time. This also indicates that pure bentonite or bentonite–sand mixtures with lower sand content tend to crack and damage during the shrinkage process, which is not conducive to the curing or long-term service of the buffer backfill blocks in engineering barriers.

Figure 5.

Moisture content change over time of samples with different sand contents.

3.2. The Effect of Pore Water Chemistry on the Drying Shrinkage Behavior

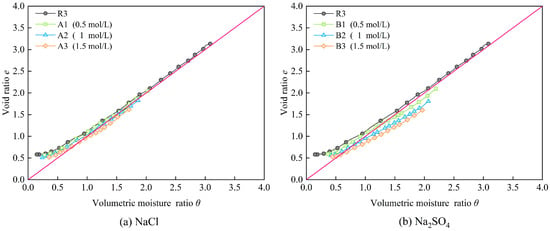

3.2.1. Salt Solution Concentration

The measured shrinkage characteristic curves of saturated samples with deionized water and saturated samples containing different concentrations of NaCl and Na2SO4 solutions are plotted in Figure 6. It can be observed that the shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with different solution concentrations can also be divided into three stages mentioned above: proportional shrinkage, residual shrinkage, and zero shrinkage. For both sodium salts, the initial saturated volumetric moisture ratio and void ratio of the samples both decrease with increasing solution concentration. As the solution concentration increases, the saturation (θ/e) in the proportional shrinkage stage is higher, suggesting that increased salt content facilitates the entry of water into the internal pores of the sample. This indicates that elevated cation concentration in pore water reduces the water retention capacity and swelling potential of bentonite–sand mixtures upon saturation process, yet enhances their water retention performance during the dehydration process. Observing the residual shrinkage stage of the shrinkage characteristic curves reveals that with increasing solution concentration, the proportional shrinkage phase ends sooner, and the volumetric moisture ratio at the beginning of the residual shrinkage stage is higher. During the transition from the residual shrinkage stage to the zero-shrinkage stage, the change in volumetric moisture ratio also decreases with increasing solution concentration. As shown in Table 4, the volume change in the sample throughout the shrinkage process decreases with increasing solution concentration. In summary, these observations suggest that soluble salts can suppress volume changes in the bentonite–sand mixture during saturation and the drying shrinkage process, while also enhancing its water retention capacity during drying. It is beneficial to reduce the volume and moisture variations in bentonite–sand mixture blocks during actual engineering curing and service, as well as the additional stresses induced by these changes.

Figure 6.

Shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with different solution concentrations.

Table 4.

Final shrinkage ratio (Rf) of samples with different solution concentrations.

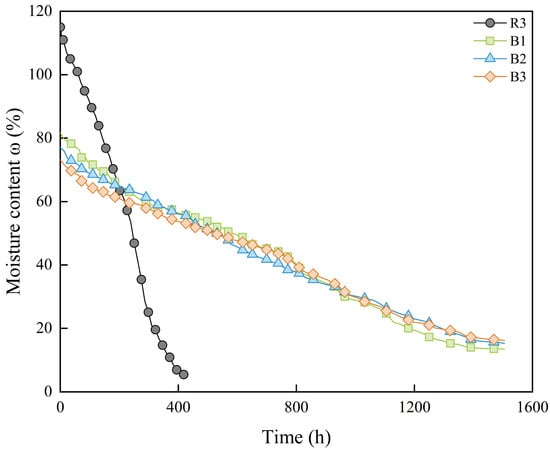

The variation in moisture content over time for samples with different solution concentrations during the shrinkage process is shown in Figure 7. Compared to samples saturated with deionized water, samples containing soluble salts exhibited a significantly slower decrease in moisture content, indicating that the pore water is more difficult to discharge during the drying process. However, the differences in the rate of moisture content reduction among samples with varying concentrations are minimal. As the concentration of the solution increases, the moisture content of the samples in the residual shrinkage stage rises. This further indicates that higher solution concentrations in the pore water enhance the water retention capacity of the bentonite–sand mixture during drying path. Although this phenomenon has positive implications for improving the deformation behavior of the blocks, it may have adverse effects from the perspective of curing time requirements.

Figure 7.

Moisture content change over time of samples with different solution concentrations.

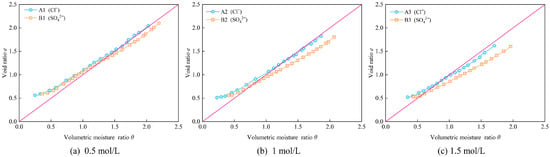

3.2.2. Ion Type

The influence of different anion concentrations of Cl− and SO42− solutions on the shrinkage characteristic curves of bentonite–sand mixture samples is shown in Figure 8. It can be observed that the shrinkage curve of samples containing Cl− consistently remains above the saturation line, while the shrinkage curve of samples containing SO42− is mostly below the saturation line before the residual shrinkage stage. This indicates that the samples containing SO42− are basically in an oversaturated state during the proportional shrinkage stage. As the anion concentration in the samples increases, the difference in volumetric moisture ratio between the sample containing SO42− and the samples containing Cl− becomes more pronounced for the same void ratio during the proportional shrinkage phase. Additionally, a comparison of the final shrinkage ratios of samples with different anion concentrations (Table 4) reveals that, at the same concentration, the final shrinkage ratio of samples containing SO42− is consistently lower than those containing Cl−. This suggests that SO42− is more effective in inhibiting the shrinkage-induced volume deformation of the bentonite–sand mixture samples.

Figure 8.

Shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with different anions.

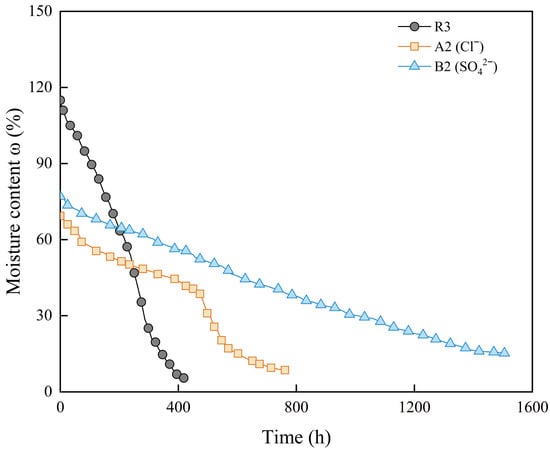

Further observation of the moisture content change over time of the samples with 1 mol/L anion concentration (Figure 9) shows that the evaporation rate of sample A2 is significantly faster than that of sample B2. The required evaporation time of sample A2 is closer to that of the deionized water sample (R3). This indicates that, in addition to influencing the shrinkage process through chemical hydration, SO42− in the pore water may also influence the drying shrinkage of the bentonite–sand mixture through physical processes such as crystallization.

Figure 9.

Moisture content change over time of samples with different anions.

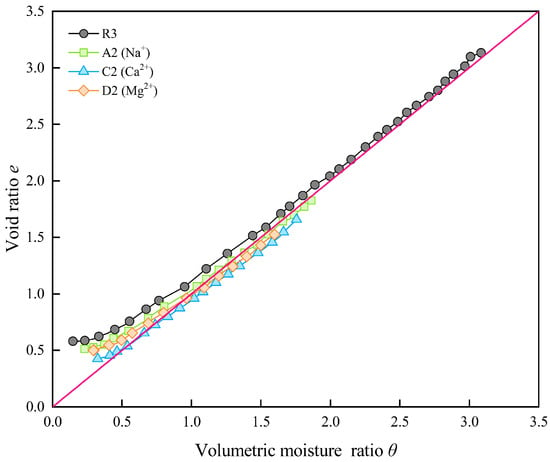

The shrinkage characteristic curves of samples containing different types of cations with the same concentration are plotted in Figure 10. It can be seen that the valence of the cation significantly affects the shrinkage behavior of the samples. Similarly to the samples containing SO42−, the shrinkage characteristic curves of the samples containing divalent cations (C2 and D2) are also in an oversaturated state during the proportional shrinkage stage. During the shrinkage process, the volumetric moisture ratio of the samples containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ are lower than that of samples containing Na+. A comparison of the final shrinkage ratios (Table 5) shows that the ability of the cations to inhibit shrinkage of the bentonite–sand mixture samples follows the order Mg2+ > Na+ > Ca2+. As shown in Figure 10, the ability of cations to suppress volume swelling at saturation follows the same order.

Figure 10.

Shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with the same cation concentrations.

Table 5.

Final shrinkage ratios (Rf) of samples containing different cations.

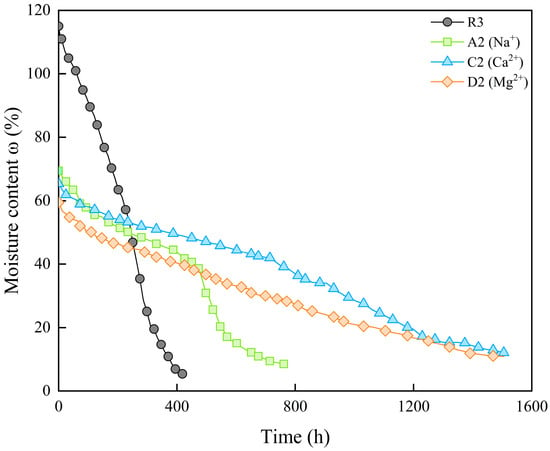

Comparing the moisture content change over time, it can be observed that the evaporation curves of the samples containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ resemble those of the samples containing SO42−, showing a slower evaporation rate (Figure 11). Hence, the solutions containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ are not suitable as additives during the curing process of the bentonite–sand mixture.

Figure 11.

Moisture content change over time of samples with different cation.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence Mechanism of Rs and Pore Water Chemistry

- (1)

- Rs

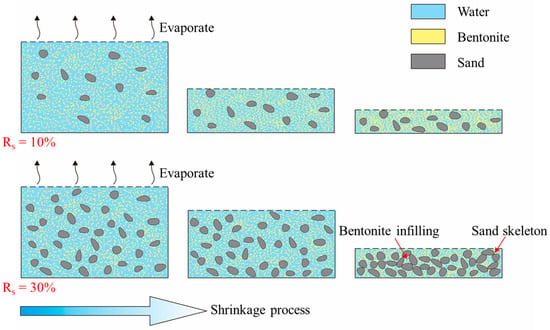

Research has found that the addition of coarse particles reduces the shrinkage properties of bentonite [43]. This is because coarse particles typically form a rigid skeleton structure within the mixture. The pore sizes formed between the coarse particle skeletons are generally smaller than the diameter of coarse particle. During the shrinkage process, these pores are filled by finer bentonite particles, while the coarse particle skeleton remains unchanged. As a result, the shrinkage properties of the mixture containing coarse particles are suppressed [44,45]. In this study, samples with sand content ratios (Rs) ranging from 0% to 30% have a relatively low content of sand. As a result, the coarse quartz particles are dispersed within the bentonite, making it difficult for a stable coarse particle skeleton to form. Therefore, within this range of sand content ratio, the shrinkage properties of the mixture remained primarily influenced by bentonite [46]. When the Rs reaches 40% and 50%, the coarse particle skeleton formed in the mixture, which suppresses the shrinkage deformation of the sample. Although no direct microstructure tests were conducted to prove this reasonable hypothetical mechanism for this sample in this work, previous studies on similar bentonite–sand systems have observed the microstructure of the mixture using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and found that as the sand content ratio increased, the coarse particle skeleton in the bentonite–sand mixture gradually formed, providing indirect verification of this mechanism [44,47,48]. Furthermore, to more intuitively understand this mechanism, a microscopic structural schematic of the shrinkage process was drawn, using samples with Rs = 10% and Rs = 30% as examples, as shown in Figure 12. To further directly verify the proposed mechanism, our future work will combine SEM-based microstructure characterization to directly examine the skeleton formation process.

Figure 12.

Microscopic structural schematic of the formation of rigid sand skeleton.

Additionally, it was observed in Figure 4 that as the sand content ratio increases from 40% to 50%, the final void ratio of the samples decreases. This is because sand does not swell during the saturation process. The higher the sand content ratio, the poorer the swelling properties of the mixture, resulting in a lower initial void ratio after the saturation stage [49]. The initial void ratio of the samples further influenced the final void ratio after shrinkage. Therefore, the decrease in the final void ratio of R5 does not indicate the maximum inhibition of bentonite shrinkage at a 40% sand content ratio. The experiment results should be discussed combined with the final shrinkage ratios of the samples listed in Table 3. The results show that the final shrinkage ratio of R5 is still lower than that of R4, confirming the mechanism mentioned above.

The study on the variation in moisture content indicates that during the shrinkage process, the loss of moisture generates matric suction between the fine bentonite particles [47,50]. In this process, non-uniform moisture distribution within the sample induces heterogeneity in matric suction, ultimately resulting crack propagation. Meanwhile, due to the larger distance between sand particles and the smaller specific surface area of sand particle, the incorporation of sand particles is expected to reduce the matric suction in the bentonite–sand mixture during the shrinkage process [51,52]. Therefore, the samples with low sand content ratio, R0 and R1, exhibited cracking and damage during shrinkage, while other samples with higher sand content ratio did not experience any damage.

- (2)

- Pore water chemistry

The effect of soluble salts in the pore water on the volume changes in soil during the saturation or drying processes can be attributed to the interaction between the ions and the diffuse double layer surrounding the soil particles, which affects the swelling/shrinkage deformation of the soil. Generally, in low salt concentration pore water chemical environment (<2 mol/L), the volume deformation of expansive clay is inhibited [53,54]. Research indicates that since clay particles typically carry a negative charge, electrostatic attraction on the surface of the clay particles leads to the formation of fixed layer and diffuse layer, which contains a significant number of hydrated cations. The thickness of the diffuse layer directly affects the spacing between clay particles, thus influencing the swelling and shrinking properties of the clay. When a significant amount of soluble salts is present in the pore water, the cations produced by the salts are expected to compress the thickness of the diffuse layer due to electrostatic repulsion, and simultaneously the ζ-potential of the fixed layer is expected to reduce. This leads to the aggregation of clay particles, decreasing the particle spacing, and thereby reducing the potential for volume changes [55,56]. In the bentonite–sand mixture, sand particles are prone to become the core of bentonite particle aggregation, and are more likely to absorb bentonite particles to form aggregates. Therefore, the addition of soluble salts in the pore water has a noticeable impact on all samples in this study.

The ability of cations to reduce the thickness of the diffuse layer is primarily related to the following three factors: the higher the cation concentration in the pore water, the stronger the electrostatic repulsion, resulting in a more pronounced reduction in the diffuse layer thickness; the higher the valence of the cations in the pore water, the stronger the electrostatic repulsion; thirdly, the more electron layers the cation has and the larger its ionic radius, the weaker the electrostatic repulsion, resulting in a weaker inhibition of the diffuse layer thickness. Among these three factors, based on the electrostatic repulsion formula F = k·|q1·q2|/r2, it can be inferred that the ionic radius has a greater impact than the other two factors [57,58].

For NaCl and Na2SO4 solutions with the same type of cation, as their concentrations increase, the inhibitory effect on the volume changes in the bentonite–sand mixture during the saturation and drying processes is enhanced (Figure 6). At the same concentration, Na2SO4 solution exhibits a stronger ability to inhibit sample shrinkage compared to NaCl solution for two reasons. Firstly, when the pore water contains the same concentration of Na2SO4 and NaCl, the different valencies of the anions SO42− and Cl− result in the Na+ concentration produced by Na2SO4 being twice that of NaCl. Therefore, due to the increase in cation concentration, Na2SO4 shows more pronounced ability to suppress volume deformation of the samples (Figure 8). Secondly, during the shrinkage process of the samples, the precipitation of Na2SO4 remaining within the soil can form heptahydrate crystals, which increase the particle spacing and cause slight swelling of the sample. This crystallization effect is the primary cause of salt swelling in sulfate saline soils. The formation of crystals is also the reason for the oversaturated state during the shrinkage process of the Na2SO4-containing sample (Figure 8). Meanwhile, according to Equations (1) and (4), it was found that the presence of water molecules in the crystalline crystals within the sample increases m1, resulting in an increase in the calculated ω value (Figure 9). As a result, the θ value obtained from Equation (4) increases, ultimately leading to oversaturation of the calculation results (Figure 8). This indicates that the experimental method used in this study may introduce some error due to the inability to exclude the mass of moisture generated by crystallization in the calculations. Therefore, when conducting moisture-related research on the shrinkage behavior of saline soils, it is recommended that researchers should implement measures to mitigate interference from water of crystallization when employing the experimental methodology presented in this study. A feasible approach is to obtain the true moisture content of multiple parallel samples at different drying stages by vacuum freeze-drying or water-washing and oven-drying, and then plot the shrinkage characteristic curve. The disadvantage is that the plotted curve will inevitably have fewer data points, which cannot continuously reflect the shrinkage process. An alternative method is to determine the crystallization rate at different shrinkage stages, and use interpolation to guide the removal of crystal errors throughout the entire shrinkage stage data.

When different types of cations are present in the pore water, both Na+ and Mg2+ ions have two electron layers, with Mg2+ having a smaller radius (0.65 Å) than Na+ (0.95 Å) and a higher valence. However, Ca2+ has three electron layers and its ionic radius (0.99 Å) is larger than that of Mg2+ and Na+. Based on the analysis at the beginning of this section, since the larger the ionic radius, the smaller the compression of the diffuse double layer thickness of soil particles, it can be found that the compression capacity of the diffuse double layer thickness of soil particles is ranked as Mg2+ > Na+ > Ca2+. Therefore, in the experiment, it can be observed that the order of inhibiting sample shrinkage is Mg2+ > Na+ > Ca2+ (Figure 10). This phenomenon is also supported by the findings of bentonite swelling behavior under different pore water chemistry conditions [53].

The effect of soluble salts in the pore water on the evaporation curve during the shrinkage process is related to the osmotic suction. Studies have found that in the saturated state, the total suction of the soil is mainly the osmotic suction, as the matric suction is essentially zero. The magnitude of osmotic suction is influenced by the salt content. As the saturation decreases, the matric suction increases, and the proportion of osmotic suction in the total suction decreases [59]. Therefore, during the proportional shrinkage stage, the sample remains saturated, and the osmotic suction caused by the soluble salts slow down the evaporation rate. When the sample enters the residual shrinkage stage, the decrease in saturation weakens the effect of osmotic suction, and the evaporation rate of the sample gradually approaches that of R3. The relative relationship between samples R3 and A2 in Figure 9 conforms to this description. For other types of soluble salts, the salts precipitated during the drying process can form hydrate crystals to varying degrees. Hence, the evaporation rate of the sample is lower, and the evaporation curve is relatively smooth (Figure 9 and Figure 11).

4.2. Fitting of the Shrinkage Characteristics Curve and Model Reliability Analysis

The GRO model is suitable for describing the functional relationship between water content and void ratio under different loads; furthermore, it has many fitting parameters, making it inconvenient for engineering applications. In thin-film technique experiments, the samples are obviously not subjected to loads. Therefore, compared to the GRO model, the MCG-B model is more suitable for fitting the experimental results of thin-film technique in this work. This study employs the MCG-B model for fitting the shrinkage characteristic curve of the samples. The MCG-B model is a continuous and smooth empirical model proposed based on the observation that most shrinkage curves exhibit an “S” shape [33]. The MCG-B model is as follows:

where e is the void ratio of the sample; e0 is the void ratio of the sample after oven drying; ev is the difference between the maximum and minimum void ratios during the experiment; θ is the volumetric moisture ratio; θi is related to the volumetric moisture ratio at the inflection point of the shrinkage characteristic curve; and β is a parameter related to the air entry value.

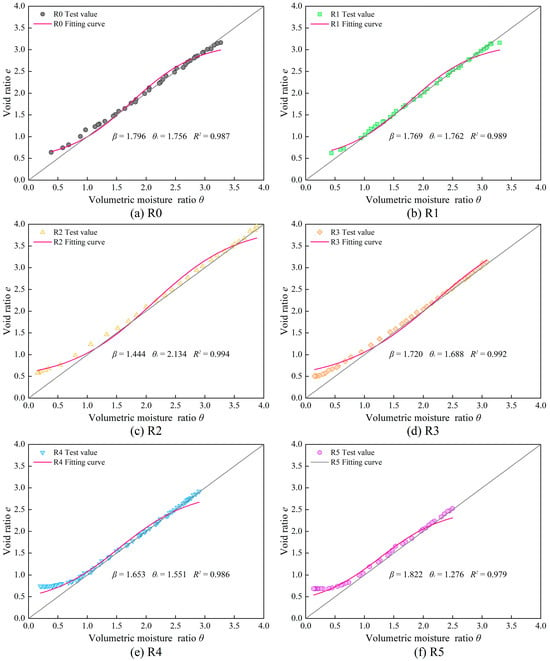

The shrinkage characteristic curves of six samples with different sand content ratios were fitted using the MCG-B model. The fitting parameters and the fitting curves are presented in Table 6 and Figure 13. The fitting results show that the coefficient of determination for all the samples is over 0.97, indicating that the MCG-B model can guarantee a high fitting quality when describing the data of this experiment empirically.

Table 6.

Fitting parameters of the shrinkage characteristic curves for samples with different sand contents.

Figure 13.

Fitting and test shrinkage characteristic curves of samples with different sand contents.

A comparison between the measured shrinkage characteristic curve and the fitting curve in Figure 13 reveals that the fitting curve performs best in the mid-section of the “S” shape for all samples. When the experiments reach the residual shrinkage stage, the volumetric moisture ratio is below 1, and the volume shrinkage becomes smaller than the volume of evaporated water. In this stage, the fitting curves for samples with sand content ratio ranging from 0% to 30% are still in line with the test values. However, the test values exceed the fitting curves in this stage for samples with 40% and 50% sand content ratio. This indicates that the MCG-B model is unable to accurately capture the suppressed effect of high sand content on the shrinkage deformation of bentonite–sand mixtures during the residual shrinkage stage. This is attributed to the model being developed based on the shrinkage characteristics of soils with high fine-grained content. When the sand content exceeds 40%, the particle composition of the mixture changes significantly. As discussed earlier, from a microscopic perspective, the formation of coarse particle skeleton during the residual shrinkage stage resulted in different shrinkage behaviors between samples with higher sand content and samples with lower sand content. However, the MCG-B model did not take into account the suppression of shrinkage caused by the coarse particle skeleton during residual shrinkage stage and the larger pore characteristic formed by the skeleton, which hence weakens the applicability and accuracy of the model.

Furthermore, there is a deviation between the fitting curve and the test values for all samples at the initial stage of the experiment. This deviation is attributed to the fact that the samples are remolded soils without strong structural properties. However, during the establishment of the MCG-B model, the experimental results of structural soil were considered, and hence there the fitting model includes a structural shrinkage stage.

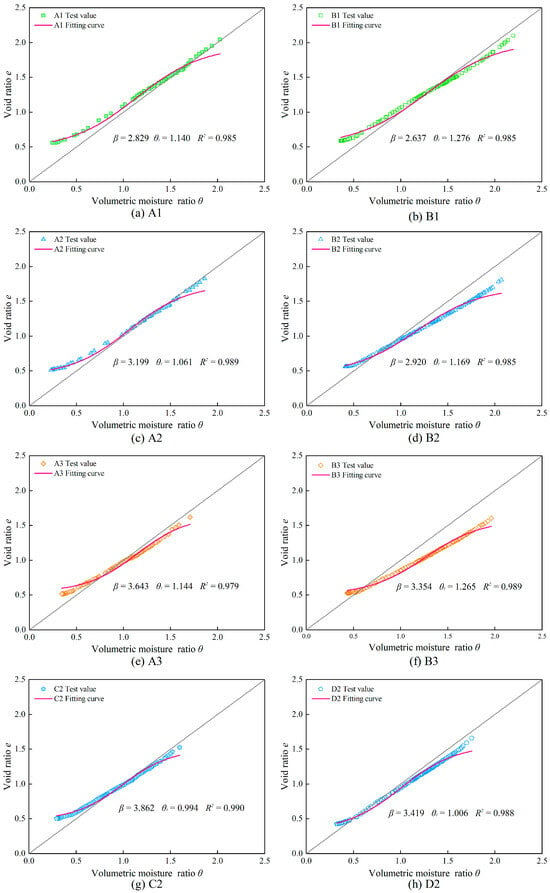

The shrinkage characteristic curves of the samples containing salt solutions were fitted using the MCG-B model, and the fitting parameters and curves are shown in Table 7 and Figure 14. The fitting results indicate that the coefficient of determination for all samples is above 97%. A comparison between the test values and the fitting curves reveals that the best fitting occurs in the proportional shrinkage stage. Similarly to the samples with different sand content ratios, the samples containing salt solutions are also remolded samples without a structural shrinkage stage. As a result, the fitting results also exhibit errors during the initial stages of the experiment.

Table 7.

Fitting parameters of the shrinkage characteristic curves for samples saturated by salt solutions.

Figure 14.

Fitting and test shrinkage characteristic curves of samples saturated by salt solutions.

According to the above fitting results, it can be found that, in general, the MCG-B model can empirically describe the shrinkage characteristics of bentonite under the influence of sand additive or pore water chemistry.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a series of drying shrinkage tests were carried out on bentonite–sand mixtures to investigate the effects of sand content, salt solution concentration, and ion type on the shrinkage characteristics of bentonite–sand buffer backfill materials. The main findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A sand content of 30% is the minimum sand contents that can inhibit the shrinkage behavior of bentonite–sand mixtures, which is in line with previous studies. When the sand content is higher than this level, significant inhibition of shrinkage behavior could be observed. Increasing the quartz sand content in bentonite helps to accelerate the evaporation process of water, which is beneficial for the curing of bentonite blocks in practical engineering barriers. Pure bentonite or bentonite with lower sand content ratio are prone to cracking during shrinkage due to uneven distribution of matrix suction. In contrast, the mix of quartz sand significantly reduces the matrix suction during the shrinkage process of the bentonite–sand mixture, thus preventing the occurrence of such issues.

- (2)

- In this study, the discussion on the influence of cations in pore water on the shrinkage properties of bentonite–sand mixtures was expanded from Na+ to Mg2+ and Ca2+. The shrinkage behavior of the bentonite–sand mixture is suppressed by soluble salts in the pore water. The strength of this suppression is influenced by factors including cation concentration, valence, ionic radius, and the crystallization characteristics of the soluble salts. When the pore water contains crystallizable soluble salts such as Na2SO4, the crystallization process will result in an overestimation of the measured water mass. Therefore, the thin-film technique should be carefully considered when measuring moisture content under the influence of pore water chemistry. An appropriate concentration of NaCl can effectively reduce the saturated swelling and drying shrinkage effects in the bentonite–sand mixture. The addition of NaCl only results in a few extensions of the shrinkage time. However, the other soluble salts involved in this experiment, due to the crystallization effect, caused the sample to be in a looser state and hence delay the shrinkage process, which is not conducive to practical engineering applications.

- (3)

- In this experiment, the measured shrinkage characteristic curves of all samples are fitted with the MCG-B model, and obtain a coefficient of determination of over 97%. This indicates the MCG-B model can empirically describe the shrinkage characteristics of bentonite–sand mixture under the influence of sand additives or the chemical properties of pore water. However, when the sand content is too high, causing the sample to gradually deviate from the clay category, or when the pore water contains crystalline salts, the MCG-B model has certain errors and should be used with caution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; Methodology, C.Z. and P.L.; Software, D.P.; Validation, D.P.; Formal analysis, D.P.; Investigation, D.P. and B.H.; Resources, P.L.; Data curation, D.P.; Writing—original draft, D.P. and C.Z.; Writing—review and editing, C.Z., B.H. and P.R.; Visualization, D.P., B.H. and P.R.; Supervision, C.Z. and P.L.; Funding acquisition, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to our laboratory’s requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Darda, S.A.; Gabbar, H.A.; Damideh, V.; Aboughaly, M.; Hassen, I. A comprehensive review on radioactive waste cycle from generation to disposal. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2021, 329, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H. Radioactive nuclear waste, Practice Periodical of Hazardous. Toxic Radioact. Waste Manag. 2002, 6, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.; Hooper, A. The disposal of radioactive wastes underground. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2012, 123, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, G.; Kudla, W.; Rosenzweig, T. Status of deep borehole disposal of high-level radioactive waste in Germany. Energies 2019, 12, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, W.R.; Reijonen, H.M.; McKinley, I.G. Natural analogues: Studies of geological processes relevant to radioactive waste disposal in deep geological repositories. Swiss J. Geosci. 2015, 108, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Duan, X.; Peng, G. Engineering barriers in deep geological disposal: Implications for radioactive nuclide migration and long-term safety. J. Environ. Radioact. 2025, 285, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupskaya, V.V.; Zakusin, S.V.; Lekhov, V.A.; Dorzhieva, O.V.; Belousov, P.E.; Tyupina, E.A. Buffer properties of bentonite barrier systems for radioactive waste isolation in geological repository in the Nizhnekanskiy Massif. Radioact. Waste 2020, 1, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, C.; Tang, C.; Li, S.; Cheng, Q.; Pan, X.; Shi, B. Effect of sand grain size and boundary condition on the swelling behavior of bentonite–sand mixtures. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 2759–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ye, W.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y. Experimental investigations on thermo-hydro-mechanical properties of compacted GMZ01 bentonite-sand mixture using as buffer materials. Eng. Geol. 2016, 213, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, D. An Assessment of the Impact of the Long Term Evolution of Engineered Structures on the Safety-Relevant Functions of the Bentonite Buffer in a HLW Repository; Savage Earth Associates Ltd.: Bournemouth, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.; Wan, M.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.G.; Cui, Y.J.; Wang, J. Temperature effects on the swelling pressure and saturated hydraulic conductivity of the compacted GMZ01 bentonite. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 68, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lv, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y. The Research on Strength and Deformation Behaviors of Buffer/Backfill Material under High-Temperature and High-Pressure Conditions. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5064690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Vonmoos, M.; Kahr, G.; Bucher, F.; Madsen, F.T. Investigation of Kinnekulle K-bentonite aimed at assessing the long-term stability of bentonites under repository conditions. Eng. Geol. 1990, 28, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, A.; Villar, M.V. Advances on the knowledge of the thermo-hydro-mechanical behavior of heavily compacted “FEBEX” bentonite. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2007, 32, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.F.; Matsuoka, H.; Sun, D.A. Swelling characteristics of fractal-textured bentonite and its mixtures. Appl. Clay Sci. 2003, 22, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Chen, Y.; Ye, W.; Cui, Y. Effects of a simulated gap on anisotropic swelling pressure of compacted GMZ bentonite. Eng. Geol. 2019, 248, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Dong, Y. Correlation between soil-shrinkage curve and water-retention characteristics. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2017, 143, 4017054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronswijk, J. Relation between vertical soil movements and water-content changes in cracking clays. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1991, 55, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenevelt, P.H.; Grant, C.D. Analysis of soil shrinkage data. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 79, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braudeau, E.; Costantini, J.M.; Bellier, G.; Colleuille, H. New device and method for soil shrinkage curve measurement and characterization. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, P.; Garnier, P.; Tessier, D. Relationship between clay content, clay type, and shrinkage properties of soil samples. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertkov, V.Y. Modelling the shrinkage curve of soil clay pastes. Geoderma 2003, 112, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Sridharan, A. A critical study on shrinkage behavior of clays. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2020, 14, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zou, W.; Han, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, X. Evolution of soil-water and shrinkage characteristics of an expansive clay during freeze-thaw and drying-wetting cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 186, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbopa, O.S. Investigation of shrinkage and cracking in clay soils under wetting and drying cycles. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2016, 5, 283–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranthaman, R.; Azam, S. Effect of compaction on desiccation and consolidation behavior of clay tills. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Tang, C.; Cui, Y.; Najdi, A. Compressive stress induced by desiccation shrinkage in clayey soils. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 267, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, A.; Prakash, K. Shrinkage limit of soil mixtures. Geotech. Test. J. 2000, 23, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Dana, K.; Singh, N.; Sarkar, R. Shrinkage and strength behavior of quartzitic and kaolinitic clays in wall tile compositions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2005, 29, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Bostwick, L.E.; Take, W.A. Effect of GCL properties on shrinkage when subjected to wet-dry cycles. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2011, 137, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ye, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, B.; Cui, Y. Impact of cyclically infiltration of CaCl2 solution and de-ionized water on volume change behavior of compacted GMZ01 bentonite. Eng. Geol. 2015, 184, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, F.; He, D.; Zhu, J. Shrinkage property of bentonite-sand mixtures as influenced by sand content and water salinity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, D.; Malafant, K. The analysis of volume change in unconfined units of soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposito, G.; Giráldez, J.V. Thermodynamic stability and the law of corresponding states in swelling soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1976, 40, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giráldez, J.V.; Sposito, G. A general soil volume change equation: II. Effect of load pressure. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, P.A.; Haugen, L.E. A new model of the shrinkage characteristic applied to some Norwegian soils. Geoderma 1998, 83, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenevelt, P.H.; Grant, C.D. Curvature of shrinkage lines in relation to the consistency and structure of a Norwegian clay soil. Geoderma 2002, 106, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupt, C.B.; Prakash, A.; Hazra, B.; Sreedeep, S. Predictive Model for Soil Shrinkage Characteristic Curve of High Plastic Soils. Geotech. Test. J. 2022, 45, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, W.M.; Corluy, J.; Medina, H.; Diaz, J.; Hartmann, R.; Van Meirvenne, M.; Ruiz, M.E. Measuring and modelling the soil shrinkage characteristic curve. Geoderma 2006, 137, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATA-UR-REHMAN, T.; Durnford, D.S. Soil volumetric shrinkage measurements: A simple method. Soil Sci. 1993, 155, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.; Ferrari, A.; Laloui, L. On the hydro-mechanical behavior of remoulded and natural Opalinus Clay shale. Eng. Geol. 2016, 208, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oualmakran, M.; Mercatoris, B.; François, B. Pore-size distribution of a compacted silty soil after compaction, saturation, and loading. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 1902–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, C.; Tang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Li, S.; Shi, B. Experimental study on shrinkage characteristics of compacted bentonite–sand mixtures. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhu, C.; Shi, B.; Liu, Y. Compression, swelling and rebound behavior of GMZ bentonite/additive mixture under coupled hydro-mechanical condition. Eng. Geol. 2017, 221, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Satyanaga, A.; D’Amore, G.A.; Leong, E. Soil–water characteristic curves of gap-graded soils. Eng. Geol. 2012, 125, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, D.; Zhang, G. Deterioration of exposed buffer block: Desiccation shrinkage and cracking. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 5431–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, S.; Delage, P.; Lenoir, N.; Cui, Y.J.; Tang, A.M.; Barnichon, J. Further insight into the microstructure of compacted bentonite–sand mixture. Eng. Geol. 2014, 168, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, K.; Rehman, Z.; Shahzadi, M.; Mujtaba, H.; Khalid, U. Optimization of Sand-Bentonite Mixture for the Stable Engineered Barriers using Desirability Optimization Methodology: A Macro-Micro-Evaluation. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zong, F.; Sun, D.; Wei, Z.; Schanz, T.; Fatahi, B. Swelling prediction of bentonite-sand mixtures in the full range of sand content. Eng. Geol. 2017, 222, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.; Ghasemi-Fare, O. Microstructural analysis of the pore size and volume distribution of bentonite at two different hydraulic states utilizing different drying techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnmr, A.; Alzawi, M.O.; Ray, R.; Abdullah, S.; Ibraheem, J. Experimental Investigation of the Soil-Water Charac-teristic Curves (SWCC) of Expansive Soil: Effects of Sand Content, Initial Saturation, and Initial Dry Unit Weight. Water 2024, 16, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdepalli, B.; Watanabe, K. Empirical Equations Expressing the Effects of Measured Suction on the Compaction Curve for Sandy Soils Varying Fines Content. Geotechnics 2023, 3, 760–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Ye, J.; Han, Z.; Vanapalli, S.K.; Tu, H. Effect of montmorillonite content and sodium chloride solution on the residual swelling pressure of an expansive clay. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, E.; Villar, M.V.; Romero, E.; Lloret, A.; Gens, A. Chemical impact on the hydro-mechanical behavior of high-density FEBEX bentonite. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2008, 33, S516–S526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R. The chemical and mineralogical controls upon the residual strength of pure and natural clays. Geotechnique 1991, 41, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, T.S.; Murthy, B.S. Rationalization of Skempton’s compressibility equation. Geotechnique 1983, 33, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.N.; Mathew, P.K. Effects of exchangeable cations on hydraulic conductivity of a marine clay. Clays Clay Miner. 1995, 43, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.; Rao, S.M. Influence of infiltration of sodium chloride solutions on SWCC of compacted bentonite–sand specimens. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2013, 31, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.X.; Graham, J.; Blatz, J.; Gray, M.; Rajapakse, R. Suctions, stresses and strengths in unsaturated sand–bentonite. Eng. Geol. 2002, 64, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.