Abstract

Vertical shafts are the lifelines of coal mines, serving as critical conduits for resources and personnel. However, the long-term exposure of shaft walls to groundwater erosion significantly reduces their service life and increases the risk of structural failures. This issue is particularly pressing in Inner Mongolia and Henan Provinces, two of China’s major coal-producing regions, where the challenge of sulfate attack on shafts in deep stratigraphic environments has become a growing concern. This study focused on the corrosion damage observed in these two typical auxiliary shafts: the net diameters and depths of the auxiliary shafts in Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine are 6 m and 768.5 m and 9.2 m and 457 m, respectively. The rock section shaft walls in the study range from 5 to 10 m in thickness and are constructed using C40 to C60 grade concrete. To assess the extent of this damage, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of shaft wall samples using water analysis, XRD (X-ray diffraction) analysis, FT-IR (Fourier transform infrared) spectroscopy, and XRF (X-ray fluorescence) analysis. The findings reveal that the identified secondary sulfate reaction products within the shaft wall concrete include calcium sulfate, gypsum, ettringite, and thaumasite. The CaO loss rates in the auxiliary shaft walls of Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine are as high as 66% and 47%, respectively. Additionally, the concentrations of SO3 and MgO in both mines exceed normal levels by up to 5 and 11 times, and 13 and 3 times, respectively. Despite this, severe corrosion is primarily confined to the inner surface of the auxiliary shaft walls, without significant penetration into the deeper shaft structure. The corrosion damage is predominantly concentrated in the shaft sections where the geological environment is characterized by bedrock. This study provides field evidence and laboratory analyses to inform the mitigation of sulfate attack in auxiliary shafts.

1. Introduction

The vertical shaft serves as the primary conduit for coal mining in underground mines, providing a critical link between the surface and the underground mining areas [1,2]. The structural stability of the shaft wall determines the safety of the whole shaft. Inner Mongolia and Henan Province are two of China’s major coal-producing regions, where several vertical shafts are in service and where the shafts pass through stratigraphic environments characterized by groundwater-rich sandstone formations. Due to these special geological conditions, conventional shaft wall designs primarily consider three factors: hydrostatic pressure, vertical additional force, and temperature stress. However, the groundwater contained in the deep sandstone formations in these mining regions contains corrosive ions, such as sulfate ions (SO42−), which can induce corrosion and damage to the vertical shaft walls. Furthermore, the shaft walls are constantly subjected to hydrostatic pressure during the long-term service of the shaft wall. A series of chemical reactions will be initiated when the corrosive ions, transported by the groundwater, penetrate the concrete shaft wall and cause corrosion damage to the concrete shaft wall. Consequently, the strength and durability of the shaft wall concrete will be reduced, which may cause groundwater damage and submerge the shaft, threatening the production safety of the staff and potentially endangering nearby communities [3]. Since 1987, hundreds of shaft wall failures have occurred in Northwest and Central China, resulting in substantial economic losses [4].

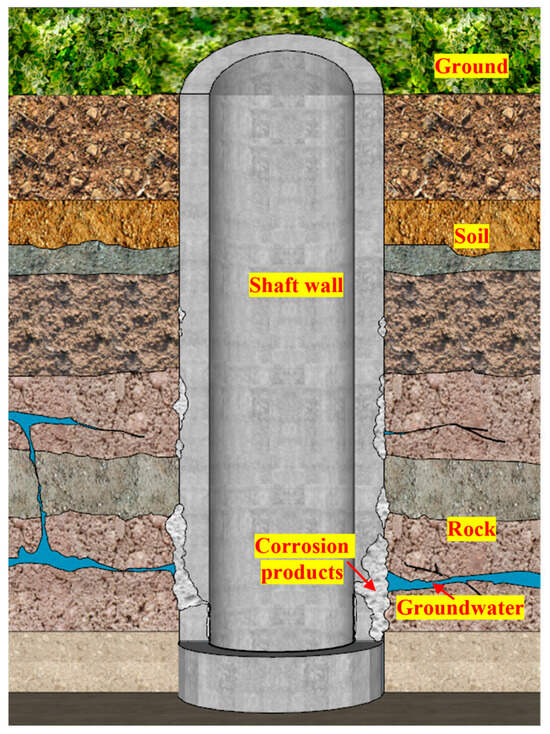

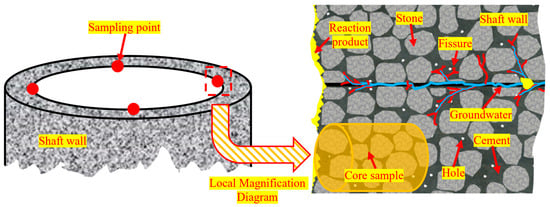

Schematic diagrams and an actual photograph of the sulfate erosion damage of the shaft wall are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of sulfate attack on concrete shaft.

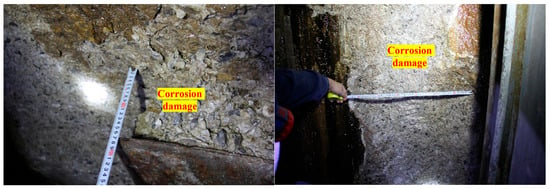

Figure 2.

The actual photograph of serious corrosion section on the shaft inner surface.

To investigate the mechanisms of concrete corrosion, numerous scholars have carried out a series of studies on the laws and variations in concrete corrosion damage through laboratory experiments. Research indicates that corrosion damage to concrete occurs due to the generation of various secondary sulfate reaction products and expansion during the corrosion process [5,6,7]. Sulfate attack is categorized into physical attack and chemical attack based on differences in crystalline products, modes of deterioration, and reaction equations. Physical attack includes the Solid-Phase Expansion Hypothesis, Crystalline Hydrate Pressure Theory, and Salt Crystallization Pressure Theory; chemical attack includes Ettringite Crystallization Attack, Gypsum Sulfate Attack, Thaumasite Sulfate Attack, and Magnesium Sulfate Dual Attack [8]. The primary products of concrete corrosion damage include gypsum, ettringite, and thaumasite. This chemical process is accompanied by a characteristic trend in compressive strength, which initially increases before subsequently decreasing [9,10,11,12,13]. Experimental studies have shown that expansive evolution during concrete corrosion can be categorized into three stages: (1) the initial stage involves the formation of ettringite, which increases crystallization pressure within the pore structure of the sample; (2) the second stage is characterized by a rapid increase in crystallization pressure, inducing microcracks in the sample, while the concomitant formation of gypsum further contributes to the expansion pressure; (3) the third stage is expansion pressure increased to the maximum value [14]. The expansion pressure generated by the formation of ettringite and gypsum during corrosion is identified as the primary cause of specimen damage [15]. Furthermore, the corrosion resistance of concrete largely depends on the pore structure in concrete [16]. To improve the sulfate attack resistance of concrete, Aman Deep and Pradip Sarkar [17] utilized slag and copper slag as concrete aggregates to increase its density, improve its chemical resistance, and reduce the reliance on natural sand. Md Tanvir Ehsan Amin et al. [18] incorporated lithium slag as a supplementary cementitious material and investigated the sulfate attack resistance of the modified cement mortar in a 5% Na2SO4 solution, demonstrating that a 40% LS content provided the optimal balance between durability and mechanical properties. Through experimental studies involving varying fly ash contents in concrete, Wu et al. [19] established a linear creep model for fly ash concrete under sulfate attack at low, medium, and high incorporation levels (ranging from 25% to 75%). Mohammed Belghali et al. [20] evaluated the sulfate attack resistance of in-service bridges by investigating the performance evolution of newly formulated ordinary concrete, self-compacting sand concrete, and samples extracted from existing bridges under sulfate attack. Due to the differences in the environments of different concrete projects, such as shafts and tunnels, scholars have further investigated the corrosion damage mechanism of concrete under the coupling of dry and wet cycles, freeze–thaw cycles, carbonation, and so on. Additionally, they have summarized the corrosion damage laws and damage calculation formulae through the mechanical properties, quality, and apparent morphological changes in concrete after corrosion damage in different environments [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In summary, the corrosion mechanism of concrete damage has been more clearly explained. Nevertheless, the primary objective of this research is still to solve actual engineering problems.

Some scholars have also carried out research on the actual corrosion damage in shaft engineering to explore the causes of shaft corrosion damage. Based on water sample analysis from a coal mine shaft, Shao [31] concluded that shaft wall concrete was gradually corroded and damaged, resulting in the surface loosening from the inner surface of the shaft to the inside, while the hard part of the concrete shaft maintains its original properties. Zhang [32] concluded that the effective components of concrete continuously react with corrosive ions to form crystalline expansion substances that disrupt the concrete microstructure. Li and Zhou [33] studied various deterioration phenomena in the auxiliary shaft wall of the Datun mine, including cracking, spalling, water immersion, water pouring, water inrush, and other seepage deformation and fracture. Wang [34] identified sulfate attack as the primary cause of shaft wall deterioration; the freeze–thaw cycle and dry–wet cycle in the internal environment significantly exacerbated the crystallization of sulfate and the formation of ettringite, accelerating damage to the inner shaft surface. Xu [35] analyzed and tested water samples of several water outlet points, which confirmed that the corrosion source is the fissure-confined aquifer. Cao et al. [36] studied how the corrosion of a shaft was mainly caused by gypsum sulfate erosion based on the observed failure mode, and proposed corresponding remediation strategies. Based on water sample analysis and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis from the shaft of a coal mine, A. Leemann and R. Loser [37] observed that the concrete strength at the damaged part was significantly reduced and the erosion caused different kinds of damage to the equipment in the shaft, concluding after testing that this was caused by sulfate erosion damage. Based on water sample analysis, SEM/EDS analysis, and XRD analysis from the shaft of a coal mine, Liu et al. [38] concluded that the chemical corrosion and expansion of ettringite, gypsum, and mirabilite—caused by the reaction between sulfate ions in groundwater and cement hydration products and the precipitation of mirabilite—leads to the spalling of shaft wall concrete. The above studies show that sulfate attack of concrete vertical shafts has become a more common and serious problem that cannot be ignored.

As the two major coal-producing areas in China, Inner Mongolia and Henan Province still have numerous vertical shafts under planning and normal service. Consequently, the corrosion problem of vertical shaft walls in the two major coal mining areas is imminent. In situ tests based on shafts are an important means of studying shaft wall corrosion damage patterns. Therefore, this paper selects two representative coal mine shafts in the two coal mining areas (Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine) to study the corrosion damage problems. Based on the water analysis, XRD analysis, FT-IR analysis, and XRF analysis of the shaft wall corrosion damage in the auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine and the auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine, this paper obtains performance changes in the two coal mine shafts after sulfate attack and summarizes the corrosion patterns. We hope to provide a reference for the prevention and control of the corrosion damage of the two auxiliary shafts and other shafts under the same working conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the failure characteristics of the corrosion area on the inner surface of the shaft wall, the original loose samples on the inner surface of the auxiliary shafts of two coal mines and the water samples at different positions were sampled, and the concrete core samples of the shaft wall were obtained by drilling the core along the thickness direction of the shaft wall. Then, physical and chemical detection and analysis were carried out after laboratory treatment, and the corrosion patterns of the shaft wall were analyzed and studied.

2.1. Materials and Concrete Properties

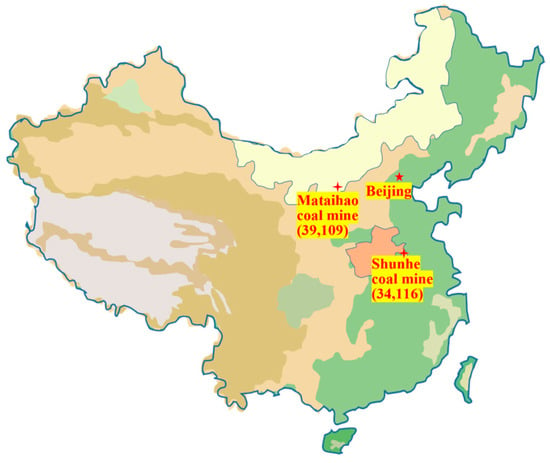

The two typical shafts are the auxiliary shaft in Shunhe Coal Mine and the auxiliary shaft in Mataihao Coal Mine, located in Northwest China and Central China. The details of these two shafts are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The geographic location of Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine in China.

The serious corrosion damage area of the shaft wall in Shunhe Coal Mine is mainly concentrated in the area of −582 m~−642 m. The serious corrosion damage area of the shaft wall is mainly concentrated in the area of −389 m~−425 m. The formation environment around the serious corrosion area of two shafts is rock stratum.

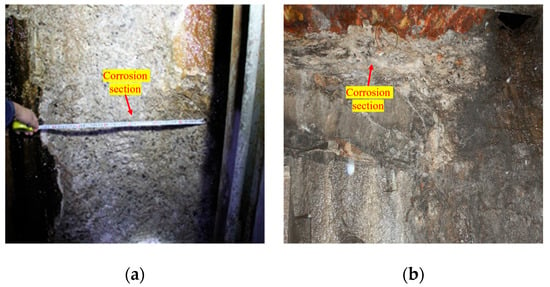

To clearly illustrate the current corrosion conditions of both shafts, Figure 4 displays actual photographs of the severely corroded inner surface areas.

Figure 4.

Actual photographs of serious corrosion sections in two shafts (a) the auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine; (b) the auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine.

- (1)

- The auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine

The construction of the auxiliary shaft in Shunhe Coal Mine started in October 2009 and was completed in October 2010. The net diameter of the shaft is 6 m and the depth of the shaft is 768.5 m. The serious corrosion damage area of the shaft wall is mainly concentrated in the area of −582~−642 m. The formation environment around the shaft wall concrete in the range of −582~−642 m is rock stratum. The design of the single-layer shaft wall in this corrosion area of bedrock section is shown in Table 1 and the corresponding concrete formula is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The structure design of auxiliary shaft wall in the serious corrosion area of Shunhe Coal Mine.

Table 2.

The mix proportion of auxiliary shaft wall concrete in Shunhe Coal Mine (kg/m3).

- (2)

- The auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine

The auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine was started in October 2009 and completed in May 2010. The net diameter and depth of the shaft are 9.2 m and 457 m, respectively. The serious corrosion damage area of the shaft wall is mainly concentrated in the area of −389 m~−425 m, and the formation environment around this serious corrosion area is also rock stratum. The design of the single-layer shaft wall and the detailed formula of shaft concrete are shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

The structure design of auxiliary shaft wall in the serious corrosion area of Mataihao Coal Mine.

Table 4.

Concrete formula of auxiliary shaft wall in Mataihao Coal Mine (kg/m3).

Both the Shunhe and Mataihao Coal Mines utilize the underground longwall mining method. At the same time, this paper selects two existing standard cement main components as the initial comparison to meet the needs of the following detection and analysis, and to judge the performance damage changes in the two auxiliary shaft wall concrete after long-term corrosion. The composition analysis standard of GSB 08-1355-F09-2023 and the content of each component in Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The content of cement clinker under different standards.

2.2. Analysis Methods

The inner surface concrete of the auxiliary shaft at Shunhe Coal Mine exhibits extensive damage areas, showing phenomena such as softening, loosening, powdering, and large-scale spalling, with severe spalling areas reaching a maximum depth of 100 mm. In contrast, the damage in the auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine is less severe, primarily exhibiting softening and loosening, without significant spalling. Based on the surface characteristics of both auxiliary shafts, sampling studies were conducted from three original samples to investigate the damage phenomena.

- (1)

- Water samples

Water samples were extracted from the water outlet points of the auxiliary shaft wall in the bedrock section for two coal mines. A total of 7 and 3 original water samples were taken from the Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine, respectively.

- (2)

- Original loose samples on the inner surface of shaft wall

The original loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall can be divided into four categories based on long-term observation: concrete pulverized loose materials, shaft wall shedding block samples, white crystalline substances, and red precipitates. Therefore, the four types of original loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall in the corrosion area were studied and analyzed. The number of collected original loose samples are 42 and 37 on the inner surface of the Shunhe Coal Mine shaft and Mataihao Coal Mine shaft, respectively.

- (3)

- Shaft concrete core samples

Given that the auxiliary shaft is a primary coal production shaft and the Mataihao Coal Mine auxiliary shaft has no extensive damage, concrete coring experiments were conducted solely in the Shunhe Coal Mine auxiliary shaft to avoid impacting the mine’s economic benefits. No coring sampling analysis in the auxiliary shaft of the Mataihao Coal Mine was performed.

Concrete core samples from the auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine were collected specifically from the identified severe corrosion damage zone, which is concentrated between depths of −582 m and −642 m. This interval was selected based on preliminary field surveys that showed the most pronounced visual damage and water seepage. Concrete core samples were collected at approximately 6 m intervals, where, based on the extent of shaft wall corrosion, three out of four radial directions at the same depth were designated as sampling locations, and three concrete core samples were extracted from each of these locations, as shown in Figure 5. The sampling process involved positioning the drilling rig at representative locations within this zone, followed by coring and backfilling the holes. The core samples, approximately Ø50 mm in diameter, were continuously retrieved along the radial direction of the shaft wall to capture the corrosion profile from the inner surface towards the exterior. A total of 105 core samples were collected.

Figure 5.

The schematic diagram of concrete core sampling points.

- (4)

- Test methods

An Ion chromatograph (Metrohm; Switzerland; Metrohm-950; pressure resistance of pump: 0~50MPa; flow rate of eluent: 0.001-20.000ml/min; concentration range of eluent: 0~100%) from China University of Mining and Technology was selected to test and analyze water samples extracted at the water outlet point. Then, the original samples were compared with water samples from shallow surface water. The X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS; Karlsruhe, Germany; D8 ADVANCE: θ: 4~70°; DS: 0.6 mm; SS: 8 mm; minimum step size: 0.0001°) at China University of Mining and Technology was employed to conduct qualitative phase analysis of the samples. The Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (VERTEX80V: spectral range: 8000~350 cm−1; resolution: >0.06 cm−1; wavenumber accuracy: >0.01 cm−1; transmittance accuracy: >0.07%) at China University of Mining and Technology was employed to conduct identification analysis of ettringite and thaumasite in the samples. The X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Bruker; Karlsruhe, Germany; S8 TIGER: element analysis range: 4 Be~92 U; element quantification range: ppm~100%; maximum power/current: 4 kW/170 mA) at China University of Mining and Technology was utilized to perform precise quantitative analysis of the elements contained in the samples.

In order to meet the requirements of XRD, FT-IR, and XRF microscopic analyses, the size of the original loose samples and concrete core samples from the inner surface of the shaft wall was measured. The apparent characteristics of the original loose samples and concrete core samples were recorded firstly, then the original loose samples were sampled along the radial section. The concrete core samples with different lengths (50 mm~100 mm) were divided into 4~5 parts along the length direction in the laboratory; the thickness of each part was about 10 mm.

The original samples (the original loose samples and concrete core samples) were immersed in 95% anhydrous ethanol for 30 min to terminate the hydration reaction. Then, the soaked original samples were placed in a constant temperature oven at 50 °C for drying treatment. To address the potential interference of coarse and fine aggregates in the original samples with subsequent microscopic analyses, the samples were processed as follows. After being dried for 48 h, the samples with varying erosion depths were crushed using a stone mill. The high-strength gravel and sand retained their granular form, whereas the cementitious components were ground into powder. The resulting powder was then passed through a 200-mesh sieve. Finally, the ground powder was divided into aliquots, sealed, and stored, thus completing the sample preparation process.

The number of prepared corrosion loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and concrete core samples is large, and the same type of samples have multiple replicates. Hence, this paper selects typical samples and their microscopic test analysis results in all test analysis results for study and analysis. The detailed test program is shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Test program in this study.

Table 7.

Concrete core samples in this study.

3. Sulfate Attack Analysis

According to the sampling type, water quality analysis was used to preliminarily determine the type of shaft wall corrosion damage, and XRD analysis and FT-IR analysis were used for phase identification and semi-quantitative analysis of corrosion loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and concrete core samples. Then, XRF analysis was used to analyze the composition and content of different kinds of corrosion loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and concrete core samples. Based on the above analysis of the shaft wall in the severely corroded area, the composition and the material elements after the corrosion were analyzed from the inner surface of the shaft to the inside. As a result, the corrosion patterns of the shaft wall can be obtained.

3.1. Water Analysis

It is found that groundwater may be the source of corrosion based on the research, so it is necessary to study the water outlet point of the auxiliary shaft wall and the groundwater composition in the bedrock section.

- (1)

- The auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine

Based on the hydrogeological report data of the shaft in Shunhe Coal Mine, the bedrock stratum corresponding to the corrosion section of the auxiliary shaft wall mainly has the following aquifers: the weathering fissure confined aquifer in the bedrock weathering zone, the fissure confined aquifer in the K6 sandstone section of the Xiashihezi formation, and the sandstone fissure confined aquifer in the second and third coal groups. It can be seen that the corrosion environment of Shunhe Coal Mine belongs to a class II environment according to relevant specification [39]. The water quality report of the shaft inspection hole and the water quality test results of the water outlet point during the hydrogeological exploration period are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Water quality test results of Shunhe Coal Mine (mg/L).

Based on the water quality analysis of the Shunhe Coal Mine shaft, it can be seen that the content of SO42− and Na+ in the groundwater of the bedrock section are higher. The SO42− content of the groundwater in the serious corrosion area of the auxiliary shaft is more than 3000 mg/L, so the groundwater has strong corrosion to the auxiliary shaft. Additionally, there are certain contents of Cl−, Ca2+, Mg2+, and HCO3−.

- (2)

- The auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine

According to the hydrogeological data of the Mataihao Coal Mine, the groundwater is rich in SO42− and Cl−, which has a corrosive effect on the concrete and steel bars of the shaft wall. The water quality analysis of the water samples at the −80 m water outlet point, the bottom of the auxiliary shaft, and the bottom of the ventilation shaft were studied, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Water quality test report of Mataihao Coal Mine (mg/L).

It can be seen from Table 9 that the content of SO42− exceeds 1800 mg/L, which belongs to a class I environment and a strong corrosion level according to the relevant specification [39]. The content of SO42− was detected in all three water quality measuring points. Moreover, the content of Cl− is up to 1200 mg/L, which is strongly corrosive to steel bars in concrete and can accelerate damage to the shaft wall. The content of HCO3− is also up to 235 mg/L. Thus, attention should be paid to the corrosion of the auxiliary shaft in Mataihao Coal Mine.

In addition, based on the water quality analysis and corrosion depth formation of Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine, it can be seen that the formation environments around the seriously corroded shaft walls in the two coal mines are sandstone layers rich in groundwater, as shown in Table 1 and Table 3. Moreover, water outlet points and obvious corrosion areas of the shaft walls appear in the shaft wall stubble and grouting holes, as shown in Figure 6. The reason for this is that the bedrock shaft is mostly located in the deep formation. Moreover, shaft walls in this formation environment are affected by high ground pressure and high water pressure for long periods of time, while shaft wall stubble and grouting holes are the weak areas of the shaft walls. Cracks easily form at the locations of shaft wall stubble and grouting holes, creating seepage pathways under high-pressure conditions; as a result, the groundwater around the shaft wall in the sandstone layer continuously invades the shaft wall through the seepage channel. Corrosive ions rich in groundwater will therefore continue to cause corrosion damage to the shaft.

Figure 6.

The schematic diagram of sulfate erosion at shaft connection seam.

3.2. XRD Analysis

Based on the geographical locations of Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine in China, and given the lowest winter temperatures in the region and the sulfate attack mechanisms, we hypothesize that the primary damage mechanism at Shunhe is classic ESA, whereas at Mataihao, there is a significant potential for TSA formation.

- (1)

- The auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine

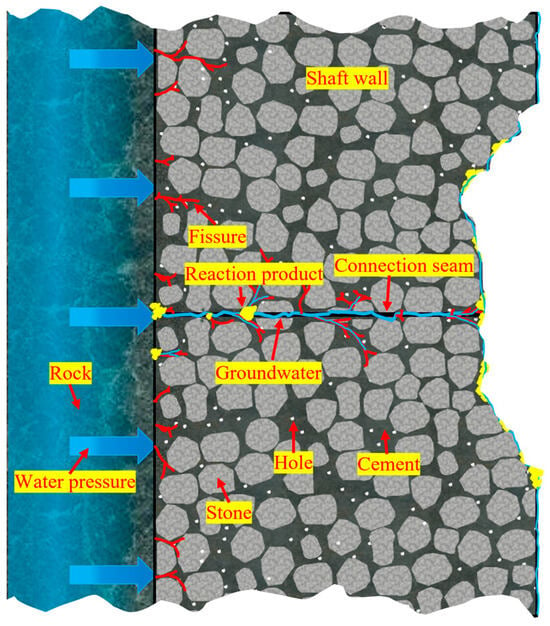

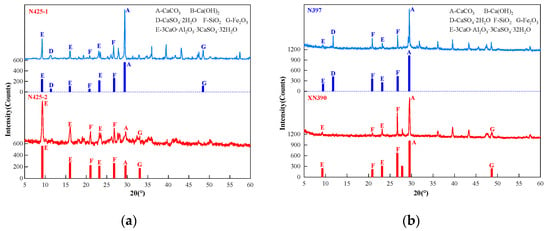

XRD analysis was performed on the samples prepared by the collected concrete shedding blocks from Shunhe Coal Mine, and the XRD patterns are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The XRD patterns of concrete shedding blocks.

The concrete loose materials on the inner surface of the shaft wall come from different depths of Shunhe Coal Mine in four directions: north, west, northwest, and southwest. The XRD pattern of the loose materials in the north and west directions of the shaft wall is shown in Figure 8a. The XRD analysis test of the concrete core samples was carried out to obtain the XRD pattern of the main substances in the corresponding concrete core samples from Shunhe Coal Mine, as shown in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

(a) The XRD patterns of loose substances in the north and west of shaft lining; (b) the XRD patterns of some concrete core samples.

It can be found from the XRD diffraction patterns in Figure 7 and Figure 8 that the main products in the shedding blocks and loose materials from Shunhe Coal Mine are calcium hydroxide, quartz, calcium carbonate, calcium sulfate, and ettringite. The main substances in the concrete core samples are calcium hydroxide and calcium carbonate, and gypsum exists in some core samples near the inner surface of the shaft wall. Among them, calcium sulfate, gypsum, and ettringite are typical products of sulfate corrosion, which indicates that the SO42− in water reacts with hydration products and calcium hydroxide in concrete under the action of groundwater. Then, the chemical reaction causes gypsum-type corrosion and ettringite-type corrosion to the concrete, resulting in the corrosion and deterioration of the shaft wall concrete.

- (2)

- The auxiliary shaft of Mataihao Coal Mine

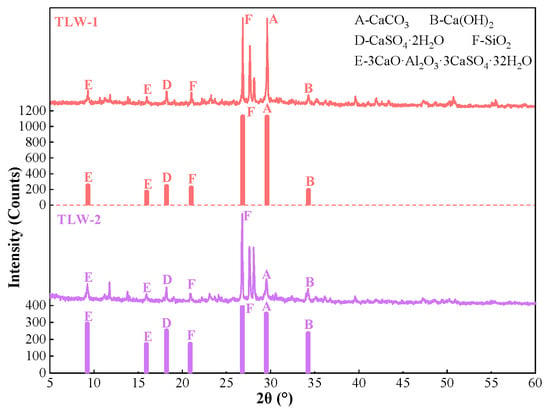

In order to further explore the reasons for the content change in the shaft wall concrete samples from Mataihao Coal Mine, the mud-like flake samples N425-1 and N425-2, red precipitate sample XN390, and the mixture of white crystal and concrete sample N397 were further analyzed. The types of secondary sulfate reaction products were analyzed by qualitative analysis using the XRD test. The XRD patterns are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

(a) The XRD patterns of mud-like samples; (b) the XRD patterns of red precipitate sample and white crystal and concrete sample..

It can be seen from the XRD diffraction patterns of N425-1 and N425-2 that the diffraction peaks of ettringite are significantly higher, which indicates that the mud-like secondary sulfate reaction products are mainly ettringite, accompanied by the formation of a small amount of gypsum. The XRD diffraction pattern of the red precipitate sample XN390 also shows obvious peaks of Fe2O3 and NaCl compared with other XRD patterns, which may be due to the electrochemical corrosion of Cl− in groundwater and steel bars in concrete, resulting in the corrosion of the steel bars. Moreover, the diffraction peak of gypsum is higher in the XRD diffraction pattern of the mixture of white crystal and concrete sample N397. It can be concluded that the crystalline salt is mainly gypsum and sodium sulfate with bound water, and its composition is mainly calcium carbonate, gypsum, and sodium sulfate with bound water.

In summary, the secondary sulfate reaction products of the shaft wall concrete in two auxiliary shafts mainly include calcium carbonate, gypsum, calcium hydroxide, ettringite, and calcium sulfate (XRD analysis cannot distinguish the diffraction characteristic peaks of ettringite and thaumasite in detail). Among them, ettringite, sodium sulfate, calcium sulfate, and gypsum are the main products of sulfate attack.

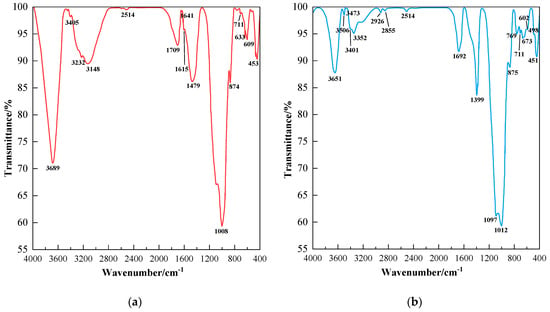

3.3. FT-IR Analysis

In the detection and analysis of samples from two coal mines, it was seen that the diffraction peaks of ettringite and thaumasite in the XRD analysis were relatively close and not clearly defined. Therefore, the FT-IR test was further carried out in the sample detection and analysis of Mataihao Coal Mine to distinguish ettringite and thaumasite by determining the different chemical bonds. The mud-like flake samples N425-1 and N425-2 in the above-mentioned Mataihao Coal Mine samples were selected for the FT-IR test, and the results are shown in Figure 10. Additionally, the characteristic wavenumbers of the main chemical bonds in the FT-IR diagram are shown in Table 10.

Figure 10.

The FT-IR patterns of samples from Mataihao Coal Mine: (a) N425-1 sample; (b) N425-2 sample.

Table 10.

Characteristic wavenumber of main chemical bonds in FT-IR diagram.

In Figure 10, it can be observed that there are characteristic peaks of the [AlO6] group, [SO4] group, and [OH] group at 456 cm−1, 1097 cm−1, and 1622 cm−1 in the erosion products, respectively, which indicates that gypsum and ettringite are formed at a depth of 425 m in the shaft. In addition, the characteristic peaks of the [CO3] group at 875 cm−1 and 1399 cm−1 were also found. Also important are the small characteristic peaks of the [SiO6] group at 498 cm−1 and 497 cm−1, as shown in Figure 10. The [SiO6] group in the thaumasite is coordinated with the six hydroxyl groups, and the distorted [Si(OH)6]2− octahedron group is formed under the action of CO32− and SO42−. This phenomenon indicates that thaumasite is formed at a depth of 425 m in the shaft. Combined with the apparent characteristics of thaumasite and the samples, it can be concluded that the secondary sulfate reaction products in the N425-1 and N425-2 samples contain thaumasite, accompanied by gypsum and ettringite.

3.4. XRF Analysis

XRF analysis was carried out on the pulverized original loose concrete samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and pulverized concrete core samples from two auxiliary shafts. This was mainly used to determine the content and variation laws for different kinds of corrosion loose samples and concrete core samples, explain the corrosion damage phenomenon of the shaft wall, and obtain its corrosion patterns. Based on the results of the XRF analysis, the contents of CaO, SO3, MgO, Fe2O3, Na2O, and SiO2 in the main components of different types of loose samples and concrete core samples changed significantly, while the contents of Al2O3, Cl, and K2O changed little. The following is the analysis of the significant changes in the content of the main components in different types of loose samples and concrete core samples.

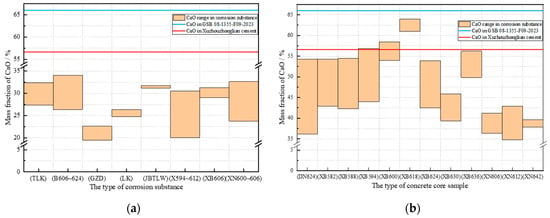

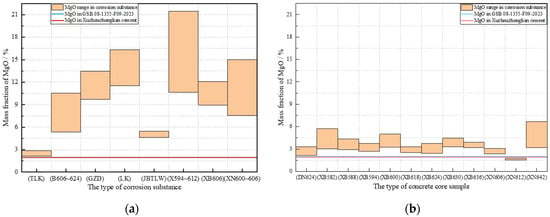

The analysis shown in Figure 11a from Shunhe Coal Mine is the XRF analysis results of the pulverized loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall. TLK, GZD, JBTLW, and LK represent the collected shaft wall shedding block samples; B606~624 represents the loose materials at depths of 606 m~624 m in the north direction of the shaft wall; X594~612 represents the loose materials at depths of 594 m~612 m in the west direction of the shaft wall; XB606 represents the loose materials at the depth of 606 m in the northwest direction of the shaft wall; GDL and GDZL represent white crystalline substances on the shaft wall inner surface. XRF analysis results of the pulverized core samples of the shaft from Shunhe Coal Mine are shown in Figure 11b. DN624 represents the core samples of the sampling point at the depth of 624 m in the southeast direction of the shaft wall; XB582 represents the core sample of the sampling point at the depth of 582 m in the northwest direction of the shaft wall; XN606 represents the core sample of the sampling point at the depth of 606 m in the southwest direction of the shaft wall. The numbering rules of the rest of the samples from two auxiliary shafts are as shown above.

Figure 11.

The mass fraction of CaO on shaft surface of Shunhe Coal Mine: (a) the samples of corrosion substance; (b) the samples of concrete core sample.

- (1)

- The content of CaO in the XRF analysis of Shunhe Coal Mine shaft

Hydration of cement in concrete generates crystals and gels, such as calcium hydroxide, hydrated calcium silicate, and hydrated calcium aluminate. These hydrates are filled between concrete aggregates and play an important role in the performance of concrete, which will decalcify and result in a decrease in the strength of the concrete when the calcium dissolution phenomenon occurs in the concrete structure. Thus, the content of Ca in concrete is an important index to measure the strength of concrete. A higher content of Ca can improve the strength of concrete, and vice versa. Based on existing research [40,41], the strength of concrete decreases rapidly and the condition of cement in concrete is also unstable when the dissolved amount of CaO in concrete reaches 10%. The strength of concrete will be reduced by 35% to 50% when the dissolved amount of CaO in concrete reaches 25%.

It can be seen from Figure 11a that the loss rate of CaO (compared with the composition analysis standard of Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement) in the concrete shedding block and the loose materials on the inner surface of the shaft wall from Shunhe Coal Mine reaches 40%~66%. It can be observed from Figure 11b that the loss rate of CaO in other concrete core samples with large damage reaches 29%~39%. Based on the corrosion damage characteristics of the shaft wall, it can be preliminarily analyzed that the groundwater had dissolved erosion on the shaft wall concrete of Shunhe Coal Mine. The main reason for this phenomenon may be that the SO42− in water reacted with Ca2+ in concrete, and the products were continuously taken away due to the water flow on the inner surface of the shaft wall, which resulted in the loss of Ca2+ and the decrease in concrete strength. The loss rate of CaO in different core samples of shaft wall concrete in Shunhe Coal Mine is different. As observed in Figure 11b, the sampling points XB594, XB600, and XB636 contain samples with CaO content close to the standard value, as well as samples exhibiting substantial leaching of CaO. The loss rate of CaO is high when the sample is taken from the core sample near the inner surface of the shaft wall, while the loss rate of CaO is low when the sample is taken from the core sample position inside the shaft wall. The main reason for this phenomenon is that the concrete core samples with CaO loss comes from the end face of the core samples close to the inner wall of the shaft, which is in long-term contact with the SO42− in the groundwater and is corroded. Given that the auxiliary shaft of Shunhe Coal Mine has not experienced shaft lining rupture, it can be preliminarily judged from Table 7 and Figure 11a,b that concrete corrosion has extensively appeared on the inner surface of the shaft in Shunhe Coal Mine. The erosion depth of the shaft wall exceeded 55 mm, even reaching over 100 mm in severely affected areas. However, the concrete inside the shaft wall can still play effective supportive and protective roles.

- (2)

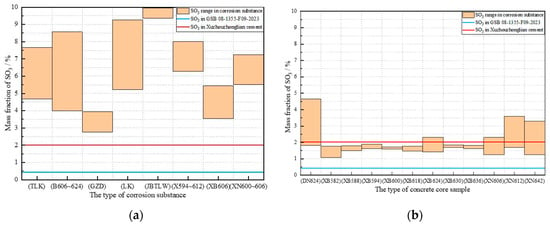

- The content of SO3 in the XRF analysis of Shunhe Coal Mine shaft

The typical change curves in the SO3 content in the XRF test of the concrete loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and concrete core samples from Shunhe Coal Mine are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The mass fraction of SO3 on shaft surface of Shunhe Coal Mine: (a) the samples of corrosion substance; (b) the samples of concrete core sample.

It can be seen from Figure 12a that the content of SO3 (compared with the composition analysis standard of Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement) in the concrete shedding block and the concrete loose materials on the inner surface of the shaft wall from Shunhe Coal Mine exceeds the standard value by 4.93 times, and the average value exceeds the standard value by 3 times. The test results show that the content of SO3 in original loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall is higher. Based on the corrosion mechanism of water on concrete, the preliminary analysis shows that the SO42− in water reacted with Ca(OH)2 in cement stone, resulting in corrosion damage to the shaft wall concrete in Shunhe Coal Mine. Moreover, it can be found from Figure 12b that the content of SO3 in most shaft wall concrete core samples does not exceed the SO3 content standard, and a small part is higher than the SO3 content standard. The reason for this may be that the content of SO3 in the shaft wall concrete core samples gradually decreases from the inner surface of the shaft wall to the outer side of the shaft wall (the length direction of the core sample). The SO3 content of the sample closest to the inner surface of the shaft wall exceeds the standard value, while the sample collected inside the shaft wall does not exceed the standard. It can be inferred from the change trend for SO3 that it is consistent with the change trend for the CaO content in the shaft wall concrete based on the sampling points XB594, XB600, and XB636, as shown in Figure 11b.

- (3)

- The content of MgO in the XRF analysis of Shunhe Coal Mine shaft

The typical change curves for the MgO content in the XRF test of the concrete loose samples on the inner surface of the shaft wall and concrete core samples from Shunhe Coal Mine are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The mass fraction of MgO on shaft surface of Shunhe Coal Mine: (a) the samples of corrosion substance; (b) the samples of concrete core sample.

It can be observed from Figure 13a that the MgO content (compared with the composition analysis standard of Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement) of the concrete shedding block and the loose materials on the inner surface of the shaft wall from Shunhe Coal Mine exceeds the standard value by 11.08 times. Based on the corrosion mechanism of concrete by water, it can be seen that MgSO4 erosion is one of the most aggressive sulfates, as shown in Figure 12a and Figure 13a. The reason is that MgSO4 erosion is a double erosion of Mg2+ and SO42−, and the two ions are superimposed on the shaft wall to form a serious composite erosion.

It can be seen from Figure 13b that the measured values of MgO content are close to the standard value and slightly exceed the standard value for different measuring points along the length direction of the core sample, which indicates that MgSO4 erosion occurs on the inner surface of the shaft. The problem of MgSO4 erosion on the inner surface of the shaft still cannot be ignored.

- (4)

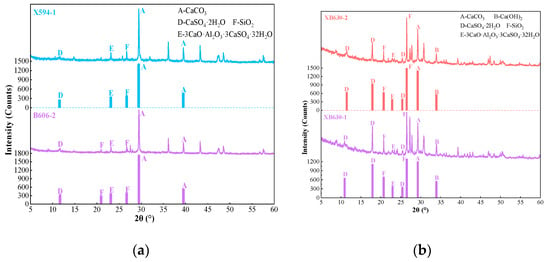

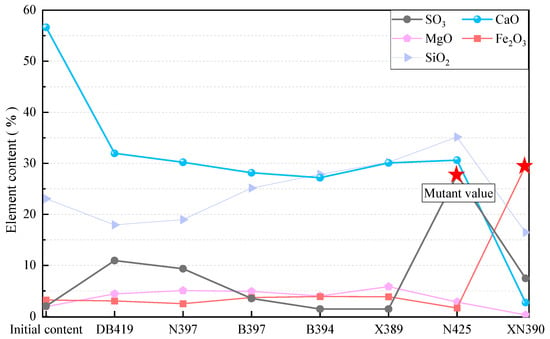

- The XRF analysis of Mataihao Coal Mine shaft

An XRF analysis test was carried out on the collected shaft wall concrete samples from Mataihao Coal Mine. Because the data obtained from the analysis test are more concentrated, and the regularity is more obvious than that of the Shunhe Coal Mine shaft, method of averaging is used for the statistical analysis in the data processing of this part, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The XRF patterns of samples from the shaft wall shedding block of Mataihao Coal Mine.

It can be seen from Figure 14 that the main components of the collected shaft wall concrete samples are CaO and SiO2. Compared with the main components of Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement, the content of CaO in the shaft wall concrete samples decreased significantly, and the content of SO3 and MgO increased to varying degrees. Among them, the content of SO3 in the mud-like flake sample N425 increases by about 13 times, the content of MgO increases slightly, and the content of CaO decreases by nearly 47%. The highest content of S indicates a decrease in concrete strength. In the mixture of white crystal and concrete samples N397 and DB419, the content of SO3 increases by about 5 times, the content of MgO increases by about 2.5 times, and the content of CaO also decreases by nearly 47%. According to its apparent characteristics and internal composition changes, this phenomenon may be due to the physical erosion crystallization of Na2SO4 or chemical erosion to produce gypsum crystals. In the blocky concrete spalling samples B397, B394, and X389, the content of CaO also decreases, the content of SO3 is basically unchanged, and the content of MgO increases by about 3 times, which indicates that it may still be in the early stage of corrosion, and the corrosion effect is not obvious. The content of Fe2O3 in the red precipitate sample XN390 also increases greatly compared with other groups, allowing us to roughly infer that its main component is rust.

According to the stoichiometric mass balance analysis, the measured CaO loss was compared with the theoretical CaO required to form the detected sulfate-containing phase.

For the severely corroded shedding block and the loose material samples from Shunhe Coal Mine, Figure 11a and Figure 12a show that the content of SO3 increases to a maximum of 9.96% (absolute mass fraction), and the loss rate of CaO reaches 40~66%; therefore, the theoretical CaO consumption for forming these sulfate phases would be approximately 7~14% (assuming all SO3 is in gypsum or ettringite, respectively). The significantly larger measured CaO loss (40~66%) indicates that substantial calcium dissolution and leaching occurred, beyond what was incorporated into the detected crystalline sulfate phases. This supports the mechanism where Ca2+ ions are first solubilized and then either form secondary phases or are transported away by seepage flow, with the latter dominating in the severely degraded surface materials.

In summary, the content of CaO is an important index to determine the concrete strength, and concrete corrosion has extensively appeared on the surface of the shaft at present. The content of CaO in all corrosion samples of the two auxiliary shafts decreases to different degrees compared with that of Xuzhou Zhonglian P·O 42.5 cement, and the content of SO3 increases to different degrees, which indicates that the erosion of groundwater lead to the loss of effective components in concrete, which is the main reason for the decrease in concrete strength. At the same time, based on the XRF analysis test, the increase in Mg2+ content and SO42− content is detected in both auxiliary shafts, which indicates that both auxiliary shafts are faced with the double composite erosion of Mg2+ and SO42−. This double composite erosion will make the corrosion damage of the shaft wall more serious.

4. Conclusions

To investigate the damage distribution on the inner surface of the auxiliary shafts in Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine, and to offer guidance on protecting these shafts against sulfate erosion, this paper presents a detailed indoor analysis based on field samples collected from both shafts. The study focuses on understanding the corrosion mechanisms affecting the inner surfaces of the auxiliary shafts in these two coal mines, with the key findings summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Corrosive nature of groundwater: The groundwater surrounding the auxiliary shafts of both Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine exhibits a high level of corrosivity. In the severely corroded areas, the concentration of SO42− in Shunhe Coal Mine exceeds 3000 mg/L, and in Mataihao Coal Mine, it exceeds 1800 mg/L. These elevated sulfate levels have caused significant corrosion to the concrete shaft walls in both auxiliary shafts, indicating an urgent need for protective measures to mitigate further damage.

- (2)

- Presence of secondary sulfate reaction products: XRD and FT-IR analyses of loose materials, shed blocks, and shaft core samples from both Shunhe Coal Mine and Mataihao Coal Mine identified the presence of secondary sulfate reaction products, such as calcium sulfate, gypsum, ettringite, and thaumasite, in the shaft wall concrete. These findings indicate that the corrosion in these auxiliary shafts is advanced and necessitates immediate intervention.

- (3)

- Loss of CaO and increased SO3 and MgO: XRF analysis of the original loose samples from the inner shaft wall surfaces and the core drilling samples revealed substantial loss of CaO from the concrete in the auxiliary shaft wall of Shunhe Coal Mine, with a loss rate as high as 66%. Additionally, there is a marked increase in the concentrations of SO3 and MgO, with maximum levels exceeding standard limits by up to 5 times and 11 times, respectively.

- (4)

- Localized corrosion in bedrock sections: Observations of the severely corroded areas and the depths at which shaft wall samples were collected suggest that the groundwater-induced damage is primarily concentrated in the bedrock sections of the shafts, particularly at the shaft joints. Despite the significant surface damage, XRF analysis and the actual conditions of the shafts indicate that the shafts still maintain their structural integrity and protective function. This pattern of damage may be attributed to the dry and wet cyclic environment created by year-round ventilation within the shafts and groundwater infiltration through fissures in the shaft walls. Further investigation into this phenomenon will be conducted in subsequent studies.

- (5)

- Based on the above findings, the following remedial measures are suggested for the two auxiliary shafts: (1) mechanical removal of the loose and corroded concrete layer on the inner surface until sound concrete is exposed; (2) application of a sulfate-resistant polymer-modified cementitious repair mortar or a dense lining system to act as a barrier against future corrosive ingress; (3) implementation of improved drainage measures at stubbles and grouting holes to mitigate water accumulation and seepage, which are the primary transport mechanisms for corrosive ions.

This paper aims to provide theoretical support for the prevention and control of corrosion damage in these two auxiliary shafts, as well as other shafts under similar conditions. Future research will consider additional methods and factors to deepen the understanding of these corrosion mechanisms. Future work should also incorporate the coupled effects of mechanical loading and chemical attack to develop a more comprehensive understanding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X.; Methodology, Y.X. and Y.W.; Formal analysis, C.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.X.; Writing—review and editing, T.H. and T.L.; Funding acquisition, T.H. and W.Y.; Investigation, Y.T., T.Z. and W.Y.; Project administration, Y.T., T.Z. and W.Y.; Resources, Y.T., T.Z. and Y.W.; Supervision, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Foundation Research Project of Xuzhou (Grant No. KC22061), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Graduate Innovation Program of China University of Mining and Technology (Grant No. 2025WLKXJ215), and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. KYCX25_2896).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (the data presented in this study were obtained for two industry-collaborative projects on coal mine shafts and are classified as confidential information of national significance.).

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their professional suggestions in im-proving this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, H.; Gui, H. Mechanism analysis and management of shaft rupture in Hengyuan coal mine. J. Suzhou Univ. 2015, 30, 110–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gui, H.; Sun, B. Research on deformation damage mechanism and prevention of sub-shaft in Renlou Coal Mine. J. Suzhou Univ. 2016, 31, 112–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X. Research on corrosion deterioration path of mine concrete shaft wall materials and countermeasures for service safety problems. In Proceedings of the 2011 China Materials Symposium, Beijing, China, 18–20 May 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.; Yang, W.; Lv, H. Freezing Walls and Shaft Walls in Deep Topsoil Layers; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Xuzhou, China, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam, M.; Cohen, M.; Olek, J. Mechanism of sulfate attack: A fresh look: Part 1: Summary of experimental results. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, M.; Cohen, M.; Olek, J. Mechanism of sulfate attack: A fresh look: Part 2. Proposed mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Shan, Z.; Miao, L.; Tang, Y.; Zuo, X.; Wen, X. Finite element analysis on the diffusion-reaction-damage behavior in concrete subjected to sodium sulfate attack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 137, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zhao, Y. Durability of Concrete Structures; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Z. Effect of sulfate solution concentration on the deterioration mechanism and physical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, Z. Study on degradation of macro performances and micro structure of concrete attacked by sulfate under artificial simulated environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, W.; Jian, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cao, K. Damage precursors of sulfate erosion concrete based on acoustic emission multifractal characteristics and b-value. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Han, F.; Qin, J.; Lu, L.; Xue, Q. Mechanical relationship between compressive strength and sulfate erosion depth of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, L. Mesoscale numerical simulation on the deterioration of cement-based materials under external sulfate attack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllauer, W.; Beddoe, R.; Heinz, D. Sulfate attack expansion mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 52, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Lv, Y.; Wang, D.; Ye, J. Study on the expansion of concrete under attack of sulfate and sulfate-chloride ions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 39, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehdi, M.; Suleiman, A.; Soliman, A. Investigation of concrete exposed to dual sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 64, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, A.; Sarkar, P. Durability of copper slag aggregate geopolymer concrete exposed to acid and sulphate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Sarker, P.; Shaikh, F. Effect of lithium slag as supplementary cementitious material on sulphate attack resistance of cement mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wu, G.; Zou, Z.; Cao, J.; Tu, B.; Liu, T. Creep performance of high-volume fly ash concrete under sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 502, 144485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghali, M.; Ayed, K.; Ezziane, M.; Leklou, N. The influence of sulfate attack on existing concrete bridges: Study of external sulfate attack (ESA). Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 483, 141751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Guo, T.; Han, P.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; He, B. Durability study and mechanism analysis of red mud-coal metakaolin geopolymer concrete under a sulfate environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, Z.; Li, S.; Hu, C.; Lu, D. Research on the performance evolution of concrete under the coupling effects of sulfate attack and carbonation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 4670–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Niu, D. Ion corrosion behavior of tunnel lining concrete in complex underground salt environment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4875–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandam, G.; Venkataraman, S. Mechanical and Durability Properties of CCD-Optimised Fibre-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. Processes 2023, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zou, H.; Dai, L.; Liu, H.; Rong, Y.; Chang, X.; Zheng, C.; Han, W. Research on the Application of Graphene Oxide-Reinforced SiO2 Corrosion-Resistant Coatings in the Long-Term Protection of Water Treatment Facilities. Processes 2025, 13, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Kong, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, J. Effect of mineral admixtures on the resistance to sulfate attack of reactive powder concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hu, X.; Zhong, S.; Sun, J.; Peng, G. Macroscopic properties evolution and microstructural analysis of early-age concrete in sulfate saline soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, H. Deterioration of cement asphalt pastes with polymer latexes and expansive agent under sulfate attack and wetting-drying cycles. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 109, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Mao, X. Model for the Patterns of Salt-Spray-Induced Chloride Corrosion in Concretes under Coupling Action of Cyclic Loading and Salt Spray Corrosion. Processes 2019, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittelboom, K.; Belleghem, B.; Heede, P.; Putten, J.; Callens, R.; Stappen, J.; Deprez, M.; Cnudde, V.; Belie, N. Manual Application versus Autonomous Release of Water Repellent Agent to Prevent Reinforcement Corrosion in Cracked Concrete. Processes 2021, 9, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y. Exploration of the causes of concrete damage in shaft wall. Met. Mine 1981, 1, 14–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Corrosion protection of concrete shaft wall in vertical shaft. Coal Sci. Technol. 1996, 24, 6–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Z. Analysis of seepage and corrosion damage potential of shaft wall concrete. J. China Coal Soc. 1996, 21, 158–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Example analysis of groundwater corrosion on concrete works in tunnels and shafts. Site Investig. Sci. Technol. 2002, 1, 3–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Study on the Corrosion Damage Mechanism of the Sub-Shaft Wall of Luohe Iron Ore Mine. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Gao, J.; Qian, Z.; Wu, Y. Mechanism of pulverization and rupture of the wall of Shuanglong Coal Mine’s sub-slope shaft and its management measures. Coal Technol. 2019, 38, 6–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemann, A.; Loser, R. Analysis of concrete in a vertical ventilation shaft exposed to sulfate-containing groundwater for 45 years. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bian, L.; He, W.; Ji, H.; Zhou, W.; Han, C. Investigation and damage mechanism of concrete wall corrosion in coal mine shaft. J. China Coal Soc. 2015, 40, 528–553. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50384-2016; Code for Investigation of Geotechnical Engineering. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese)

- Li, J.; Cao, J. Research and Application of Durability of Hydraulic Concrete; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J.; Sun, C.; Liu, Z. Corrosion of Concrete and Reinforced Concrete and Methods of Its Protection; China Building Materials Press: Beijing, China, 1984. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).