The Mechanism of Calcium Leaching from Steel Slag Based on the “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Route

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. BOFS

2.1.2. Chemical Reagents

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Chemical Composition Analysis

2.2.2. Mineral Phase Composition Analysis

2.2.3. Thermodynamic Analysis

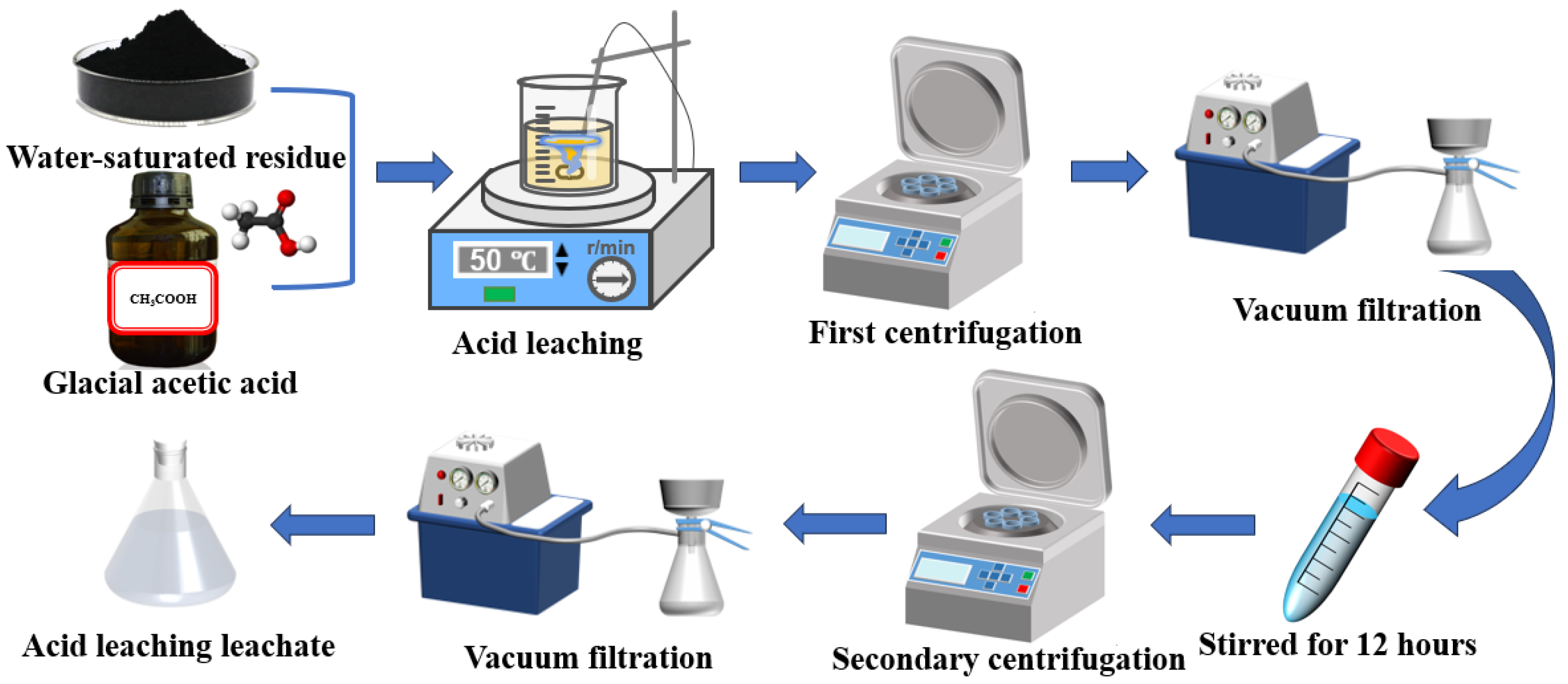

2.2.4. “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Experiment

2.2.5. Orthogonal Experimental Design

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of BOFS

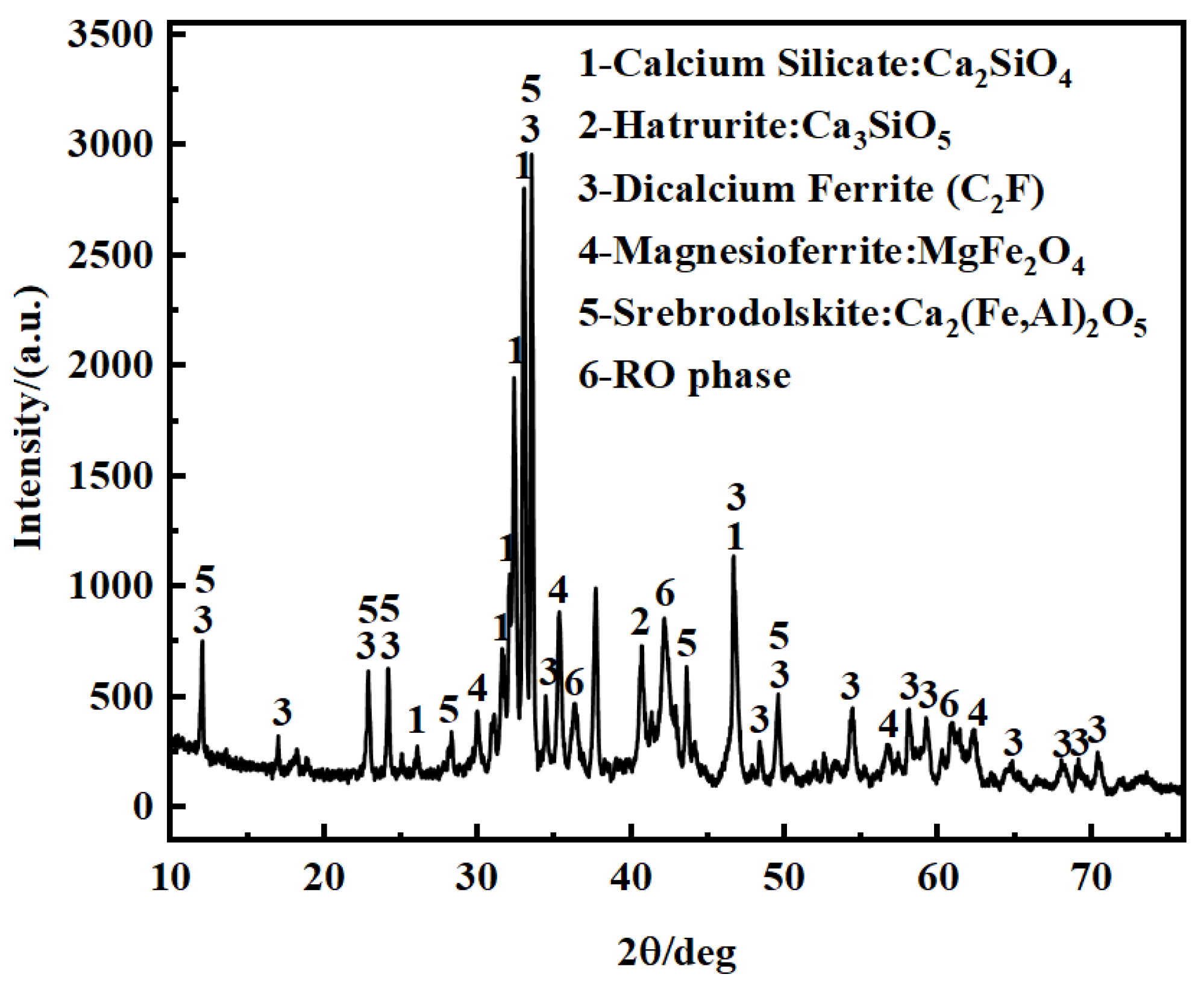

3.2. Mineral Phase Composition of BOFS

3.3. Hydrolysis of Initial Phases in BOFS

3.4. Mineral Phase Analysis of Water-Leached Residue

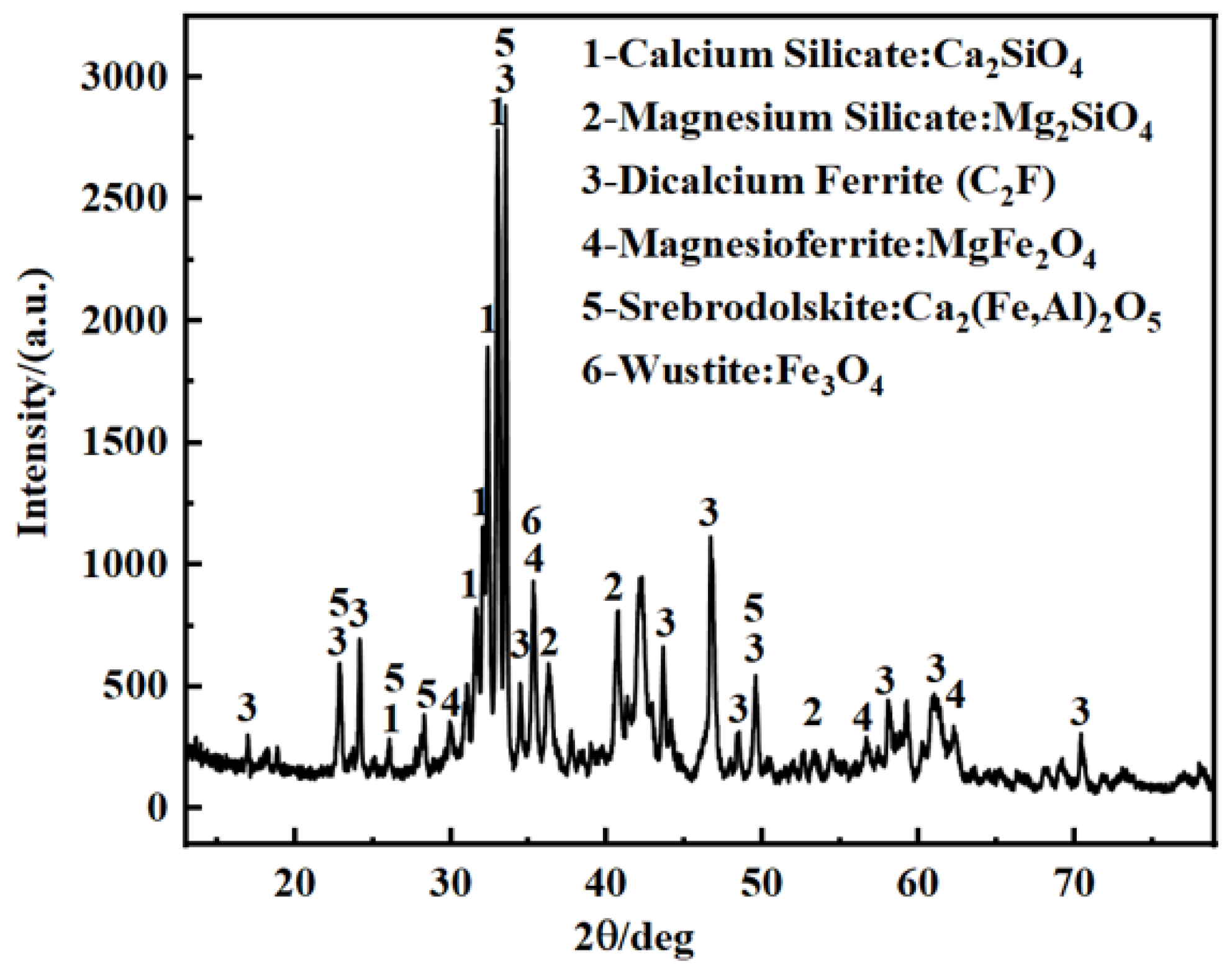

3.5. Acid Dissolution of Mineral Phases in Water-Leached Residue

3.6. Water-Acetic Acid Leaching of Calcium from BOFS

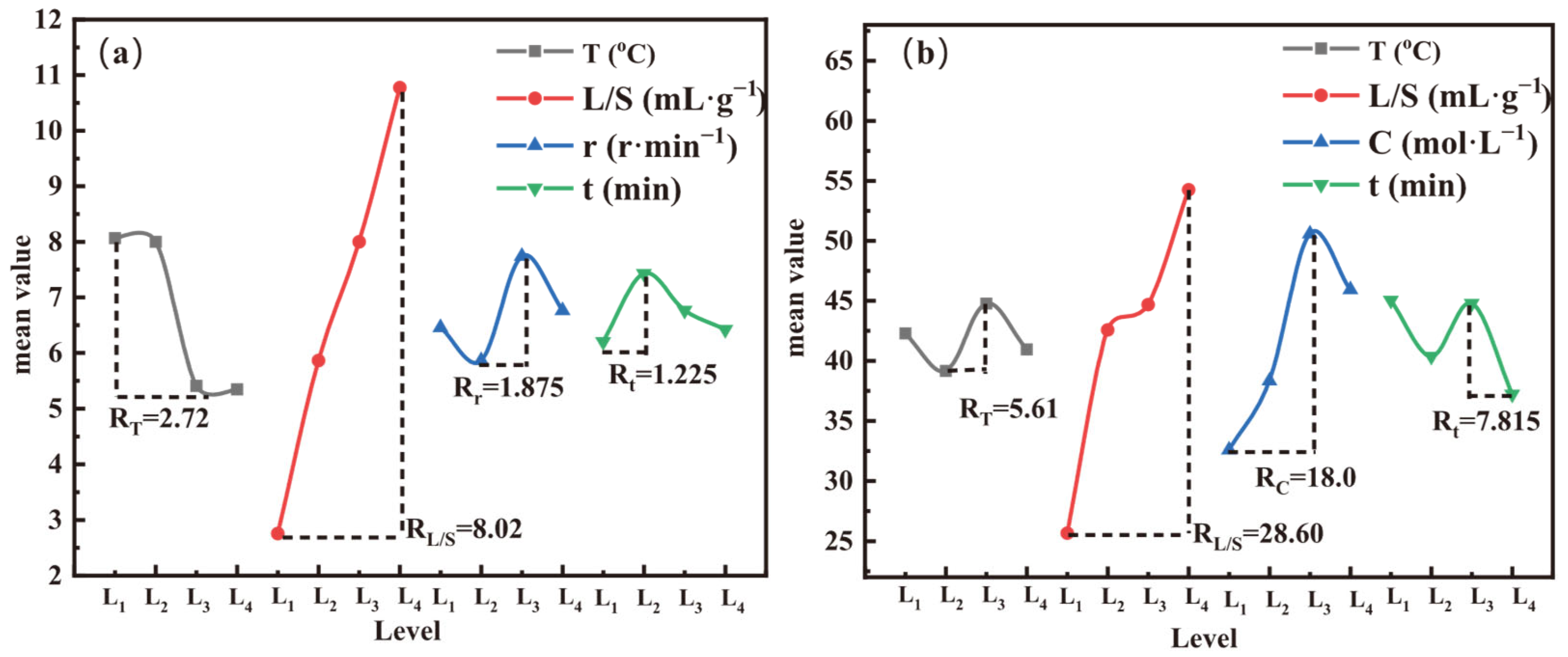

3.6.1. Analysis of Orthogonal Experimental Results

3.6.2. Analysis of Single-Factor Experimental Results for the Water Leaching Process

3.6.3. Analysis of Single-Factor Experimental Results for the Acid Leaching Process

3.6.4. Mineral Phase Analysis of Acid-Leached Residue

3.6.5. Enhancement of Calcium Extraction Efficiency by Two-Step Leaching Method

3.6.6. Economic Analysis and Environmental Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Water leaching selectively dissolved f-CaO, C3S, and part of C2S, while acetic acid further dissolved residual C2S and Ca2Fe2O5, fully aligning with thermodynamic predictions.

- (2)

- The liquid-to-solid ratio was the primary controlling factor in both leaching steps, with temperature and acetic acid concentration additionally governing acid leaching. The optimal conditions were as follows: water leaching at 25 °C, L/S = 50 mL·g−1, and 600 r·min−1 for 30 min, followed by acid leaching at 65 °C, 1 mol·L−1 CH3COOH, and L/S = 50 mL·g−1 for 60 min.

- (3)

- The two-step leaching route achieved a Ca recovery of 75.9%, outperforming direct acetic acid leaching (68.31%) and reducing acid consumption by ~90%, demonstrating its clear advantages for efficient and sustainable BOFS utilization in indirect carbonation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richmond, S.; Millsteed, W.; Wilson, R. Steel and Steel Making Raw Materials: Prospects for Iron Ore, Steel, Metallurgical Coal and Nickel. Aust. Commod. Forecast. Issues 2020, 13, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Gao, A. Leaching Mechanism of Ca and Mg from Converter Steel Slag in Seawater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoble, Y.N.; Ahmed, S. Review on the innovative uses of steel slag for waste minimization. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, C.D.; Tripathi, N.; Carey, P.J. Mineralization Technology for Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasi, G.K.; Rezaei, G.S.; Hughes, D.; Ahmed, T. Exploring the potential of steel slag waste for carbon sequestration through mineral carbonation: A comparative study of blast-furnace slag and ladle slag. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, A.M.; Bercaw, J.E.; Bocarsly, A.B.; Dobbek, H. Frontiers, opportunities, and challenges in biochemical and chemical catalysis of CO2 fixation. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6621–6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Cai, W.J.; Wang, C.; Sanwal, M. The relationships between household consumption activities and energy consumption in china—An input-output analysis from the lifestyle perspective. Appl. Energy 2017, 207, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.C.; Fan, X.H.; Gan, M.; Wei, J.Y.; Gao, Z.T. Microwave-enhanced selective leaching calcium from steelmaking slag to fix CO2 and produce high value-added CaCO3. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 330, 125395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Cui, B.; Li, L.J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.Z. Removal of calcium and magnesium from lithium concentrated solution by solvent extraction method using D2EHPA. Desalination 2020, 479, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Large, D.J.; Adderley, B.; West, H.M. Calcium leaching from waste steelmaking slag: Significance of leachate chemistry and effects on slag grain mineralogy. Miner. Eng. 2014, 65, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraghechi, H.; Rajabipour, F.; Pantano, C.G.; Burgos, W.D. Effect of calcium on dissolution and precipitation reactions of amorphous silica at high alkalinity. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 87, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y. Engineering feasibility, economic viability and environmental sustainability of energy recovery from nitrous oxide in biological wastewater treatment plant. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 282, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Yoon, S.W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.X. Reduction of steel slag leachate pH via humidification using water and aqueous reagents. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragipani, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Akkihebbal, S.K. Understanding dissolution characteristics of steel slag for resource recovery. Waste Manag. 2020, 117, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, S.K.; Youn, M.H. Calcium extraction from steelmaking slag and production of precipitated calcium carbonate from calcium oxide for carbon dioxide fixation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 53, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłacz, K.; Carlos, R.N. The mechanism of vapor phase hydration of calcium oxide: Implications for CO2 capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12411–12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firor, R.; Seff, K. Near zero coordinate calcium(2+) and strontium(2+) in zeolite A. Crystal structures of dehydrated Ca6-A and Sr6-A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 3091–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, B.; Dei, L. Synthesis of Ca(OH)2 Nanoparticles from Diols. Langmuir 2001, 17, 2371–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.T.; Bielefeldt, W.V.; Bragança, S.R. Influence of ladle slag composition in the dissolution process of the dicalcium silicate (C2S) layer on doloma-C refractories. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 15360–15369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Y.; Huang, J.Z.; Chang, J. Understanding the carbonation reactivity of α′L-C2S, β-C2S and γ-C2S based on the DFT simulation and experimental verification. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 23471–23483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Dobson, C.M.; Richardson, I.G. In situ solid-state NMR studies of Ca3SiO5: Hydration at room temperature and at elevated temperatures using 29Si enrichment. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 3926–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhankhar, S.; Bhalerao, G.; Ganesamoorthy, S.; Baskar, K. Growth and comparison of single crystals and polycrystalline brownmillerite Ca2Fe2O5. J. Cryst. Growth 2017, 468, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodbrake, C.J.; Young, J.F.; Berger, R.L. Reaction of beta-dicalcium silicate and tricalcium silicate with carbon dioxide and water vapor. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1979, 62, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, T.; Shishin, D.; Decterov, S.A. Thermodynamic optimization of the Ca-Fe-O system. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2016, 47, 256–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khot, V.M.; Salunkhe, A.B.; Phadatare, M.R.; Pawar, S.H. Formation, microstructure and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline MgFe2O4. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Li, M.; Zhu, F. Variation on leaching behavior of caustic compounds in bauxite residue during dealkalization process. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 92, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioli, C.; Soldati, A. Mechanisms for particle transfer and segregation in a turbulent boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 468, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Nastac, L. Mathematical Investigation of Fluid Flow, Mass Transfer, and Slag-steel Interfacial Behavior in Gas-stirred Ladles. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2018, 49, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Chen, T.F.; Gao, X.J. Carbonation kinetics of steel slag in CO2-loaded potassium glycine solution: Maximization of carbonation conversion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 143025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.H.; Wang, F.; Yan, C.C.; Tian, Z.J. Leaching behavior of metals from iron tailings under varying pH and low-molecular-weight organic acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Nancollas, G.H. Calcium orthophosphates: Crystallization and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4628–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, Y.Y.; Nie, Y.F. Investigation of accelerated and natural carbonation of MSWI fly ash with a high content of Ca. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 174, 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Q.; Ma, J.W.; Ren, Y.Q.; Li, Y.J. Calcium leaching characteristics in landfill leachate collection systems from bottom ash of municipal solid waste incineration. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Phoungthong, K.; Shi, D.X. Leaching characteristics of calcium-based compounds in MSWI Residues: From the viewpoint of clogging risk. Waste Manag. 2015, 42, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oxide | CaO | Fe2O3 | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | TiO2 | Cr2O3 | P2O5 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass percent/% | 37.893 | 36.418 | 10.095 | 5.209 | 1.56 | 0.639 | 0.303 | 3.643 | 4.240 |

| Mineral Facies | The First Leaching Experiment | Log(K) | ΔrGθ (kJ·mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ƒ-CaO | CaO + H2O = Ca2+ + 2OH− | 10.322 | −57.923 |

| C3S | 2C3S + 6H2O = 3CaO·2SiO2·3H2O + 3Ca2+ + 6OH− | 4.699 | −5.838 |

| β-C2S | 2C2S(B) + 5H2O = CaO·2SiO2·2H2O + 3Ca(OH)2 | 0.095 | −0.542 |

| Ca2Fe2O5 | CaO·Fe2O3 + 4H2O = Ca(OH)2 + 2Fe(OH)3 | −1.905 | 10.873 |

| Ca2Al2O5 | CaO·Al2O3 + 4H2O = Ca(OH)2 + 2Al(OH)3 | 3.209 | −18.317 |

| Mineral Facies | The Second Leaching Experiment | Log(K) | ΔrGθ(kJ·mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | Fe3O4 + 8CH3COOH = 2Fe3+ + Fe2+ + 8CH3COO− + 4H2O | −137.274 | 770.343 |

| C2S | C2S + 4CH3COOH = 2Ca2+ + 4CH3COO− + SiO2 + 2H2O | 27.694 | −155.409 |

| Ca2Fe2O5 | Ca2Fe2O5 + 10CH3COOH = 2Ca2+ + 2Fe3+ + 10CH3COO− + 5H2O | 11.517 | −64.630 |

| MgFe2O4 | MgFe2O4 + 8CH3COOH = Mg2+ + 2Fe3+ + 8CH3COO− + 4H2O | −20.642 | 115.834 |

| Mg2SiO4 | Mg2SiO4 + 4CH3COOH = 2Mg2+ + 4CH3COO− + SiO2 + 2H2O | 17.470 | −98.035 |

| Factors | Sum of Squared Deviations | Degrees of Freedom | F | Critical Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/°C | 0.003 | 3 | 0.833 | 3.290 | Absence |

| L/S/(mL·g−1) | 0.014 | 3 | 3.889 | 3.290 | Presence |

| r/(r·min−1) | 0.001 | 3 | 0.278 | 3.290 | Absence |

| t/min | 0.000 | 3 | 0.000 | 3.290 | Absence |

| Error | 0.02 | 15 |

| Factors | Sum of Squared Deviations | Degrees of Freedom | F | Critical Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/°C | 0.008 | 3 | 0.111 | 2.190 | Absence |

| L/S/(mL·g−1) | 0.214 | 3 | 2.964 | 2.190 | Presence |

| C/(mol·L−1) | 0.093 | 3 | 2.288 | 2.190 | Presence |

| t/min | 0.013 | 3 | 0.180 | 2.190 | Absence |

| Error | 0.036 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Cang, Q.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Yu, S.; Hu, B.; Yao, X.; Du, P.; et al. The Mechanism of Calcium Leaching from Steel Slag Based on the “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Route. Processes 2025, 13, 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124077

Zhang K, Cang Q, Peng L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Li H, Yu S, Hu B, Yao X, Du P, et al. The Mechanism of Calcium Leaching from Steel Slag Based on the “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Route. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kai, Qiong Cang, Lijie Peng, Yitong Wang, Shan Zhang, Hongyang Li, Shan Yu, Baojia Hu, Xin Yao, Peipei Du, and et al. 2025. "The Mechanism of Calcium Leaching from Steel Slag Based on the “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Route" Processes 13, no. 12: 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124077

APA StyleZhang, K., Cang, Q., Peng, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Li, H., Yu, S., Hu, B., Yao, X., Du, P., & Wang, Y. (2025). The Mechanism of Calcium Leaching from Steel Slag Based on the “Water-Acetic Acid” Two-Step Leaching Route. Processes, 13(12), 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124077