Drop Dispersion Through Arrayed Pores in the Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray (CTST)

Abstract

1. Introduction

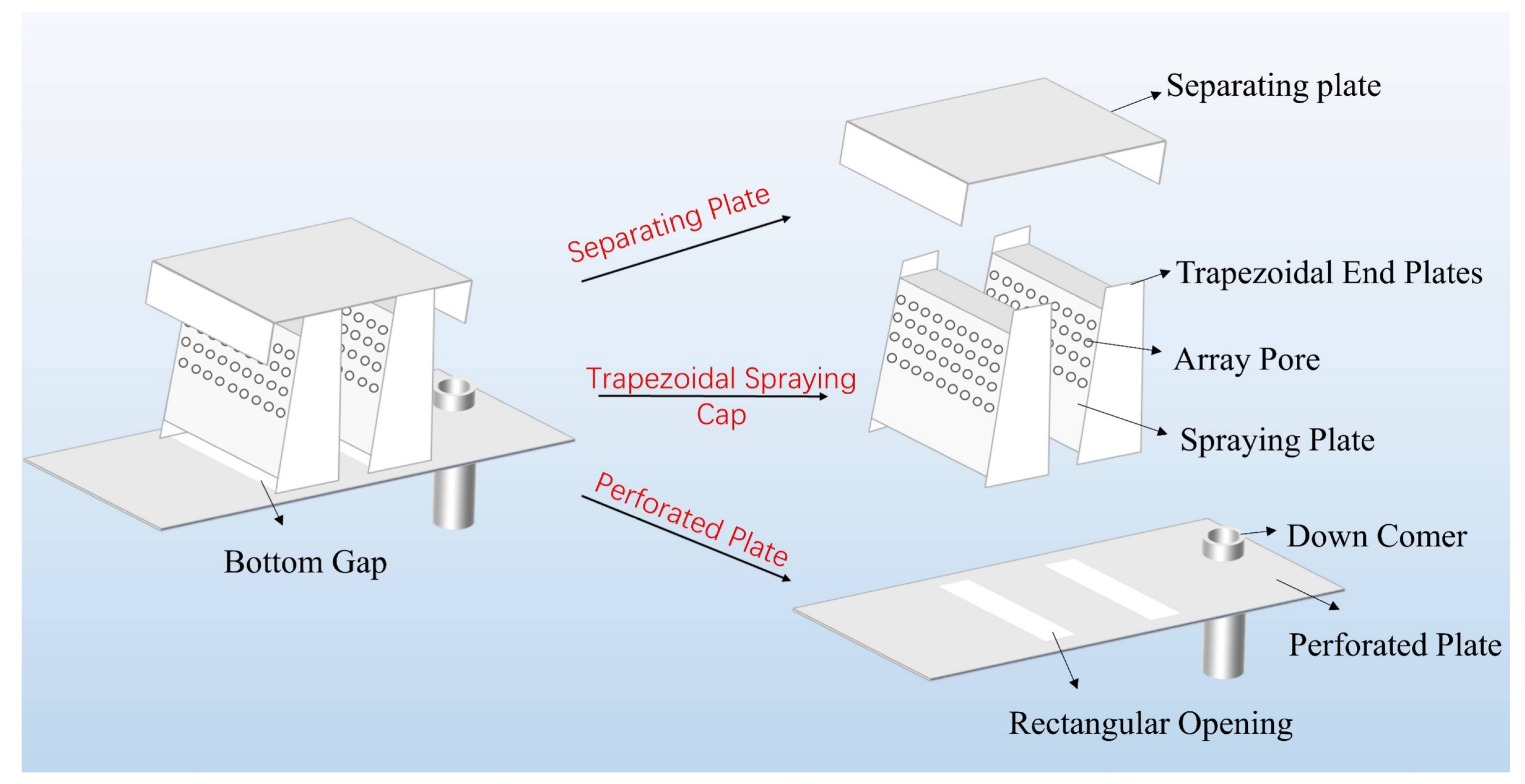

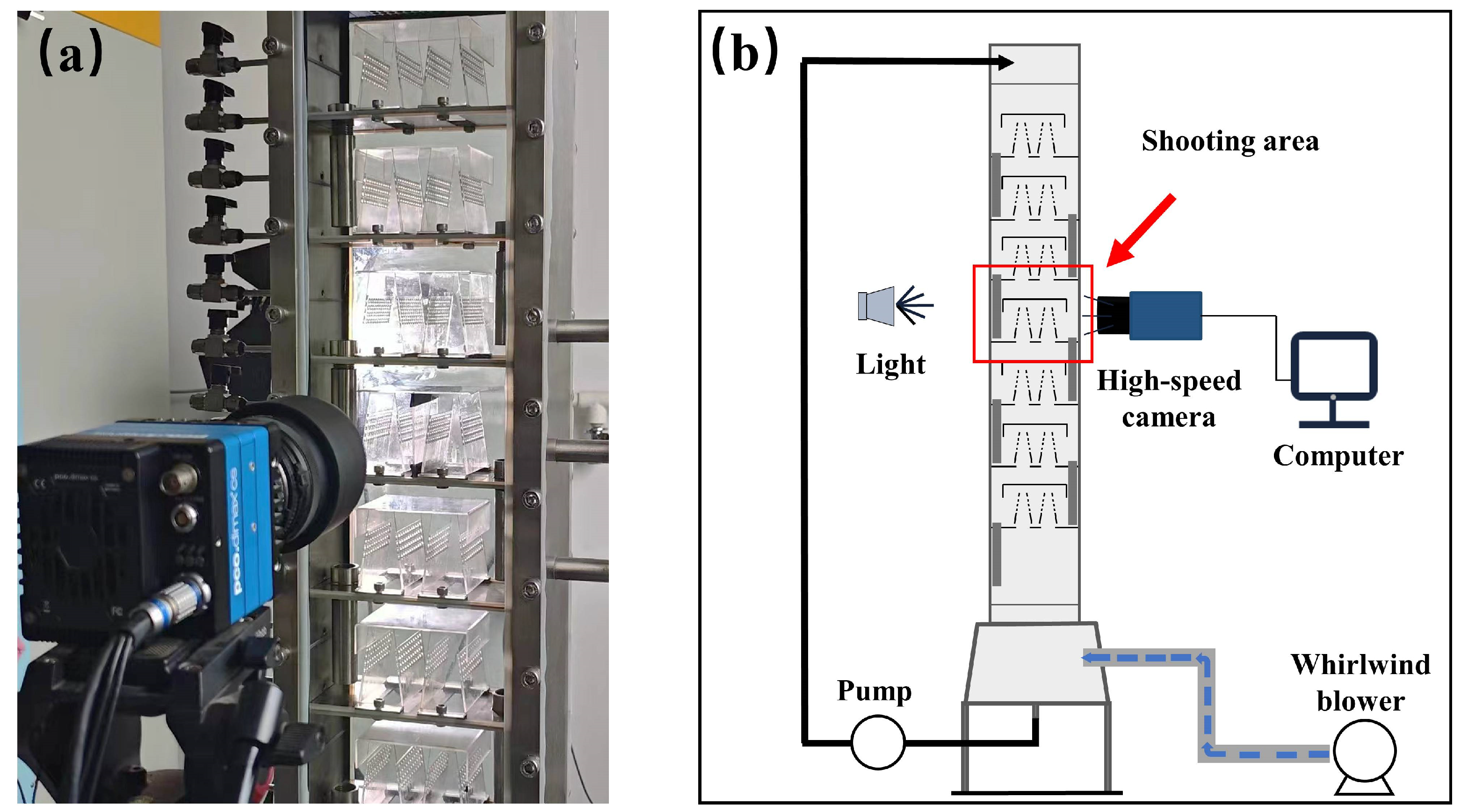

2. Experiments

3. Simulation

3.1. Governing Equations

3.2. Numerical Settings

- (1)

- Gas Inlet

- (2)

- Liquid Inlet

- (3)

- Boundary Condition for the Outlet

- (4)

- Boundary Condition for the Wall

- (5)

- Symmetry Boundary Condition

4. Results and Discussion

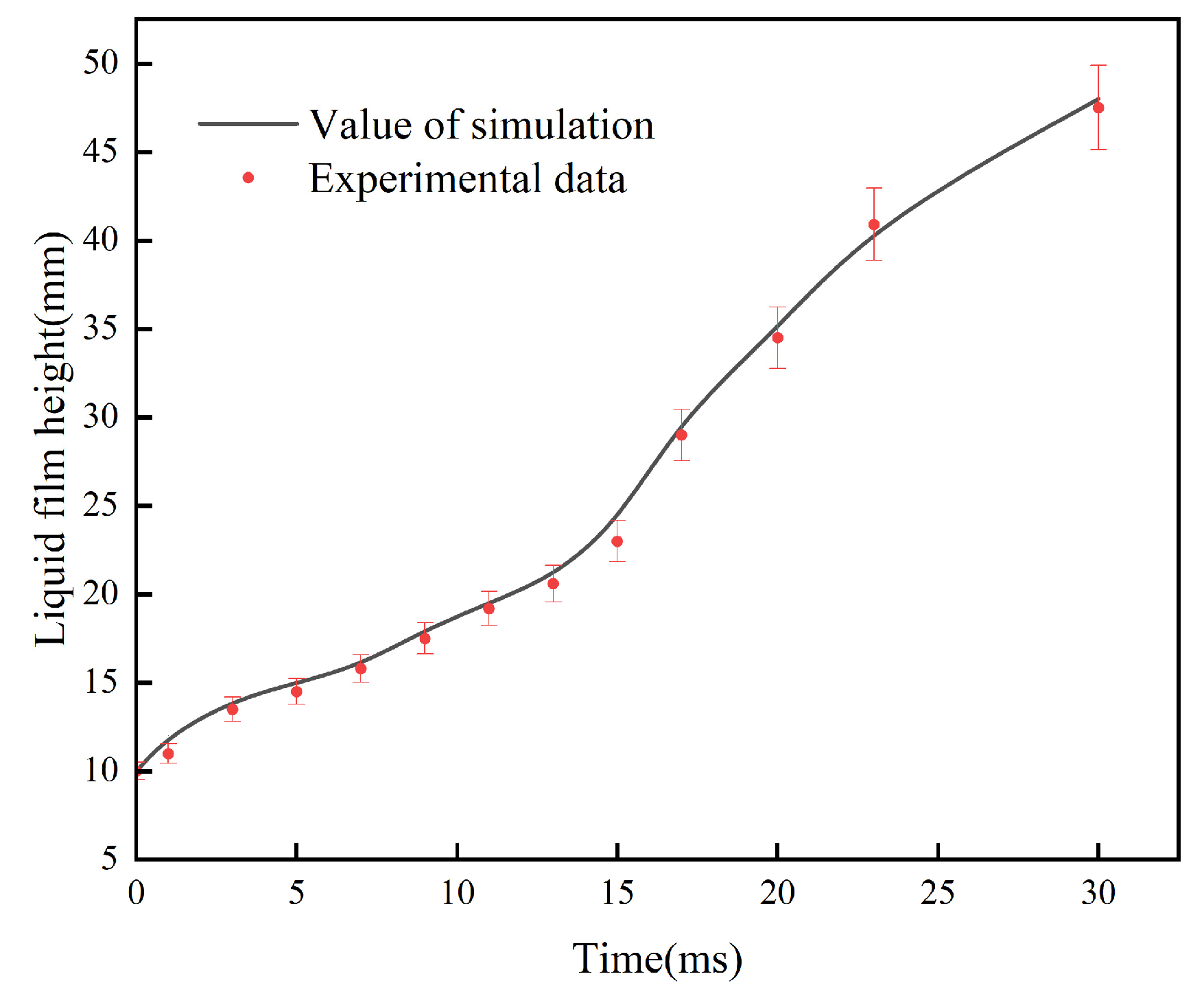

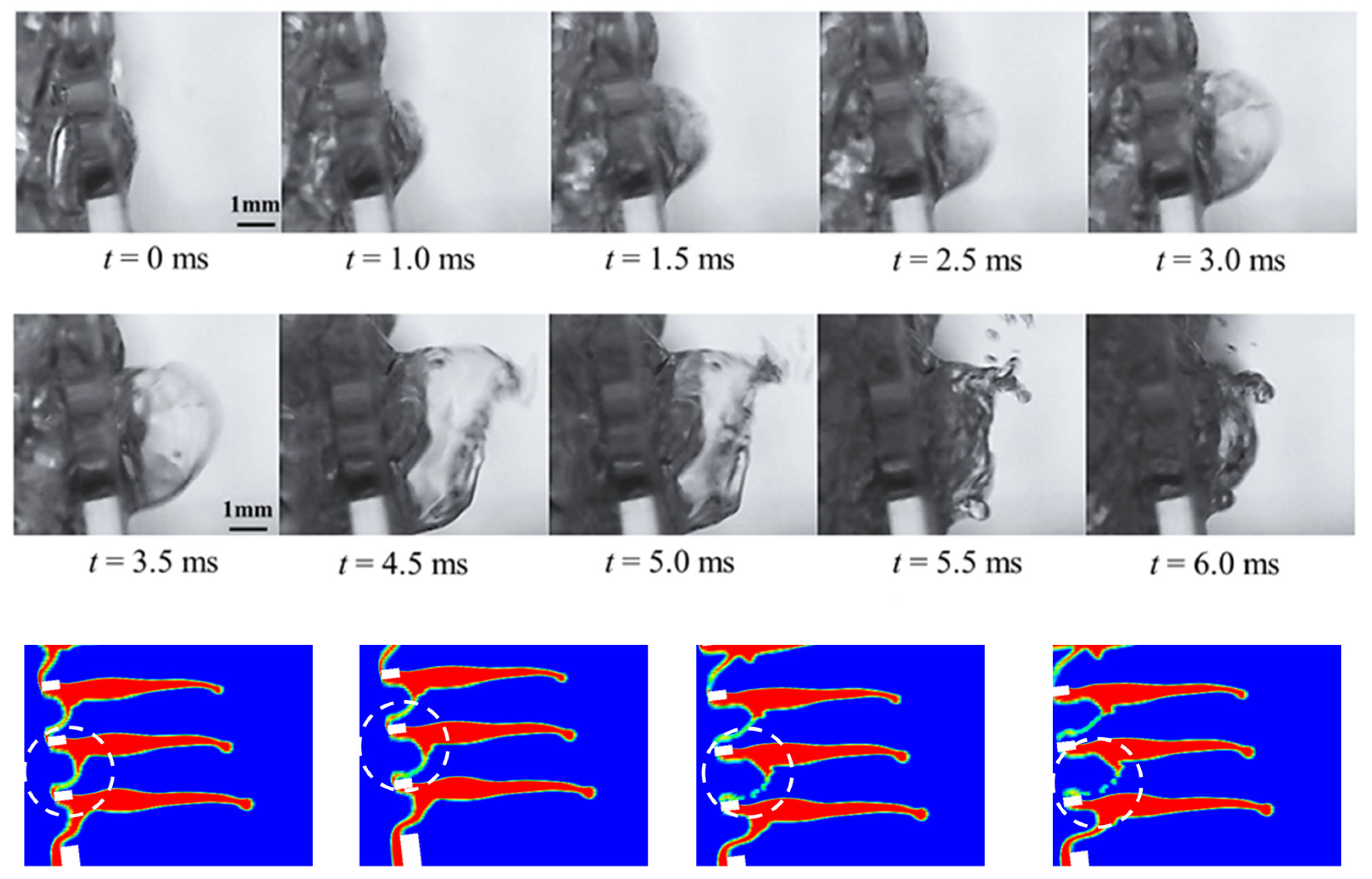

4.1. Model Verification

4.2. Drop Dispersion

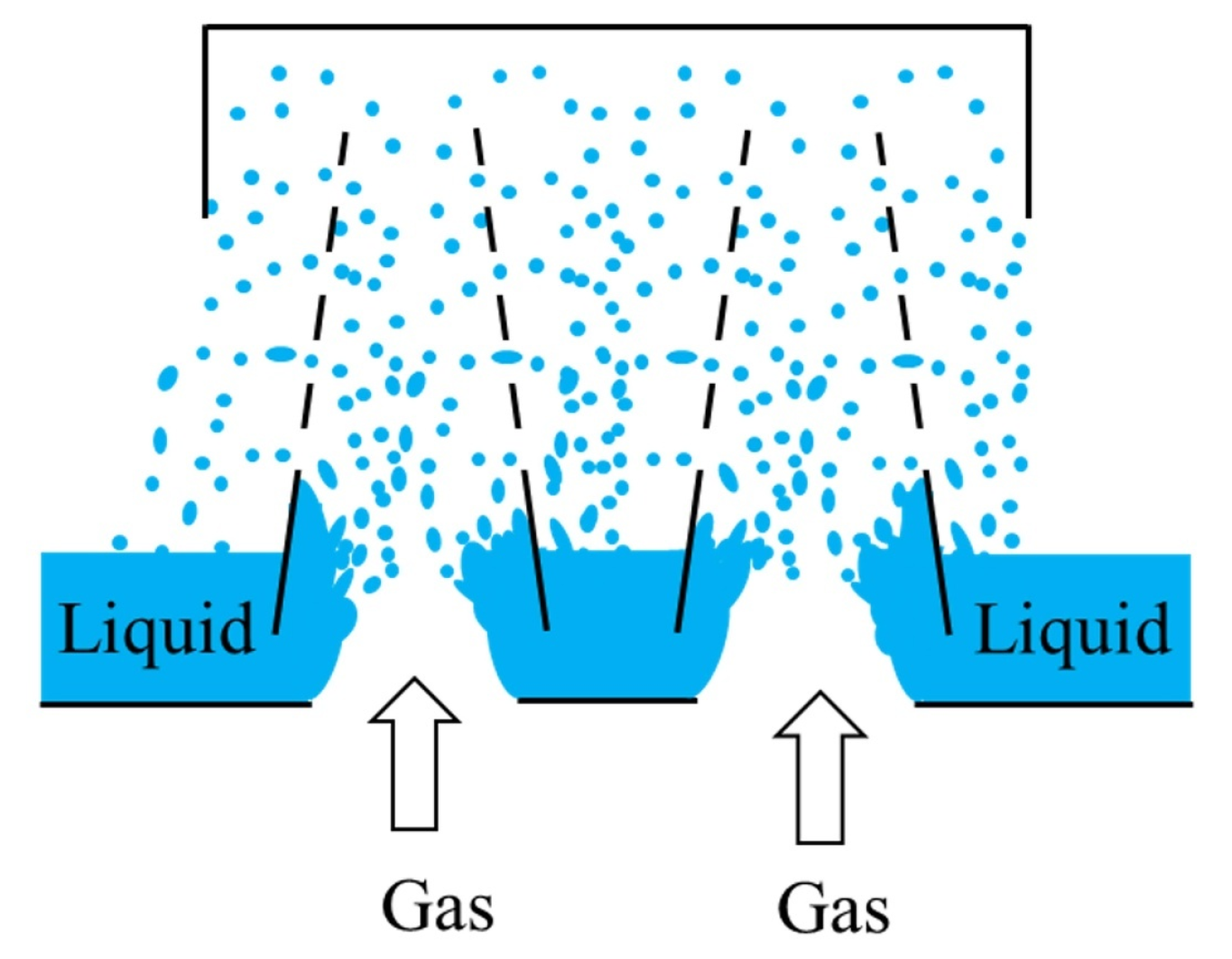

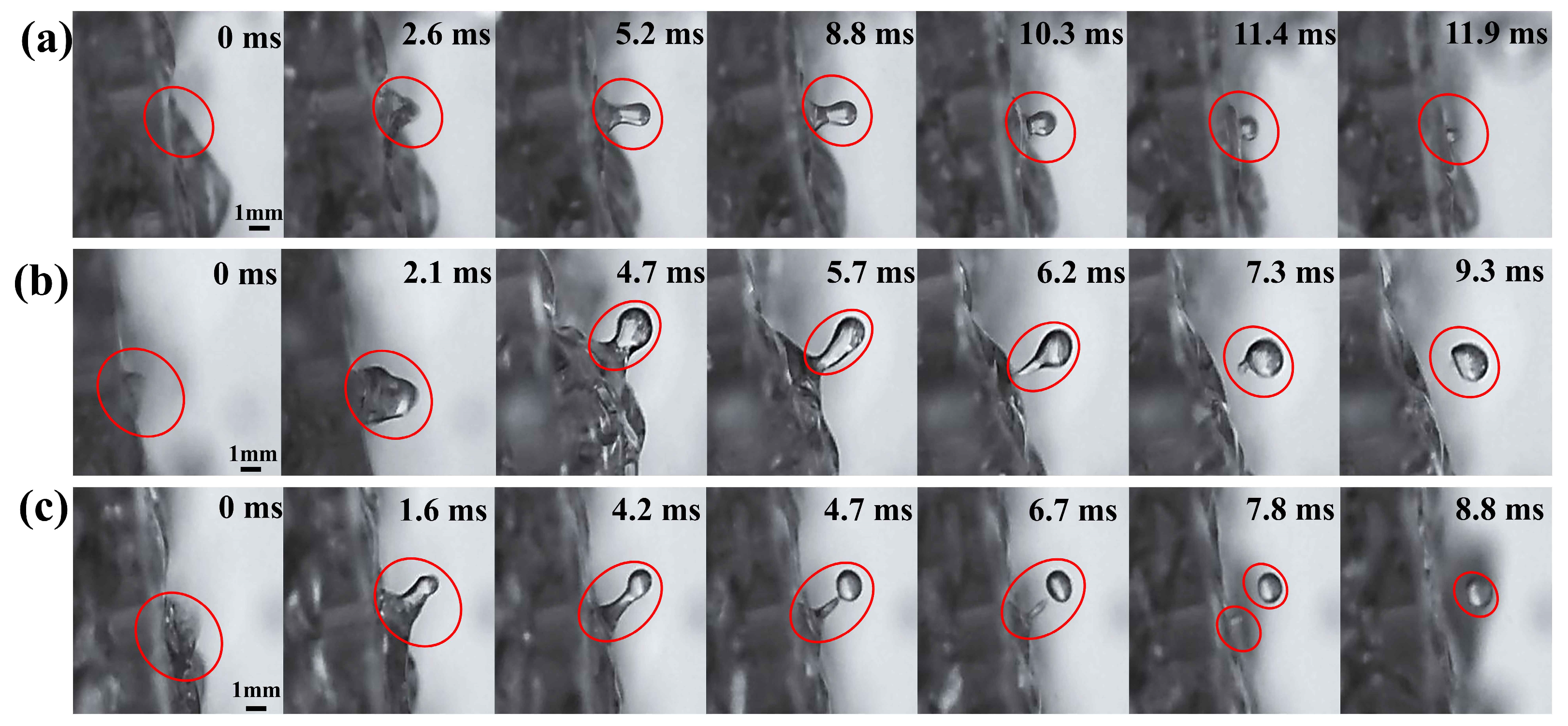

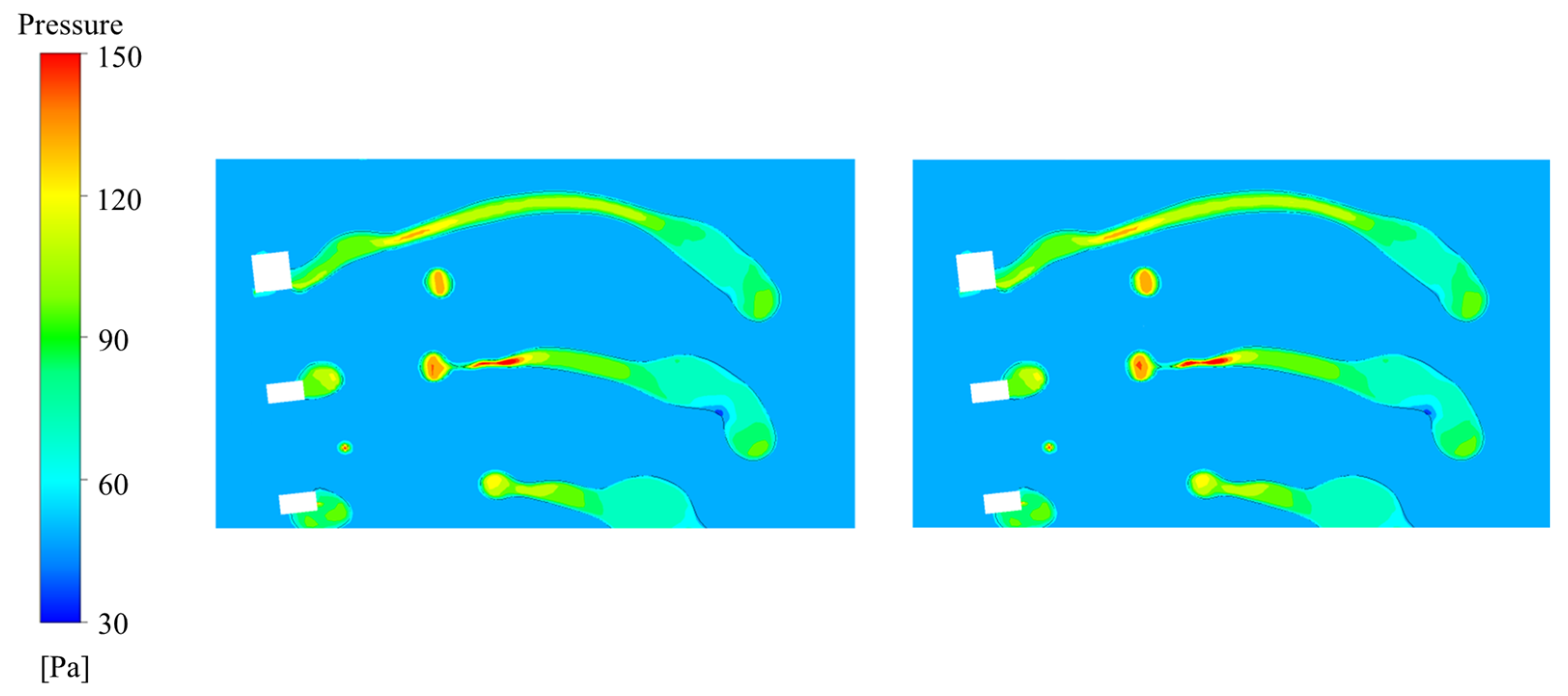

4.2.1. Fracture of Liquid Columns

4.2.2. Tearing of Liquid Films

4.2.3. Liquid Film Bag Dispersion

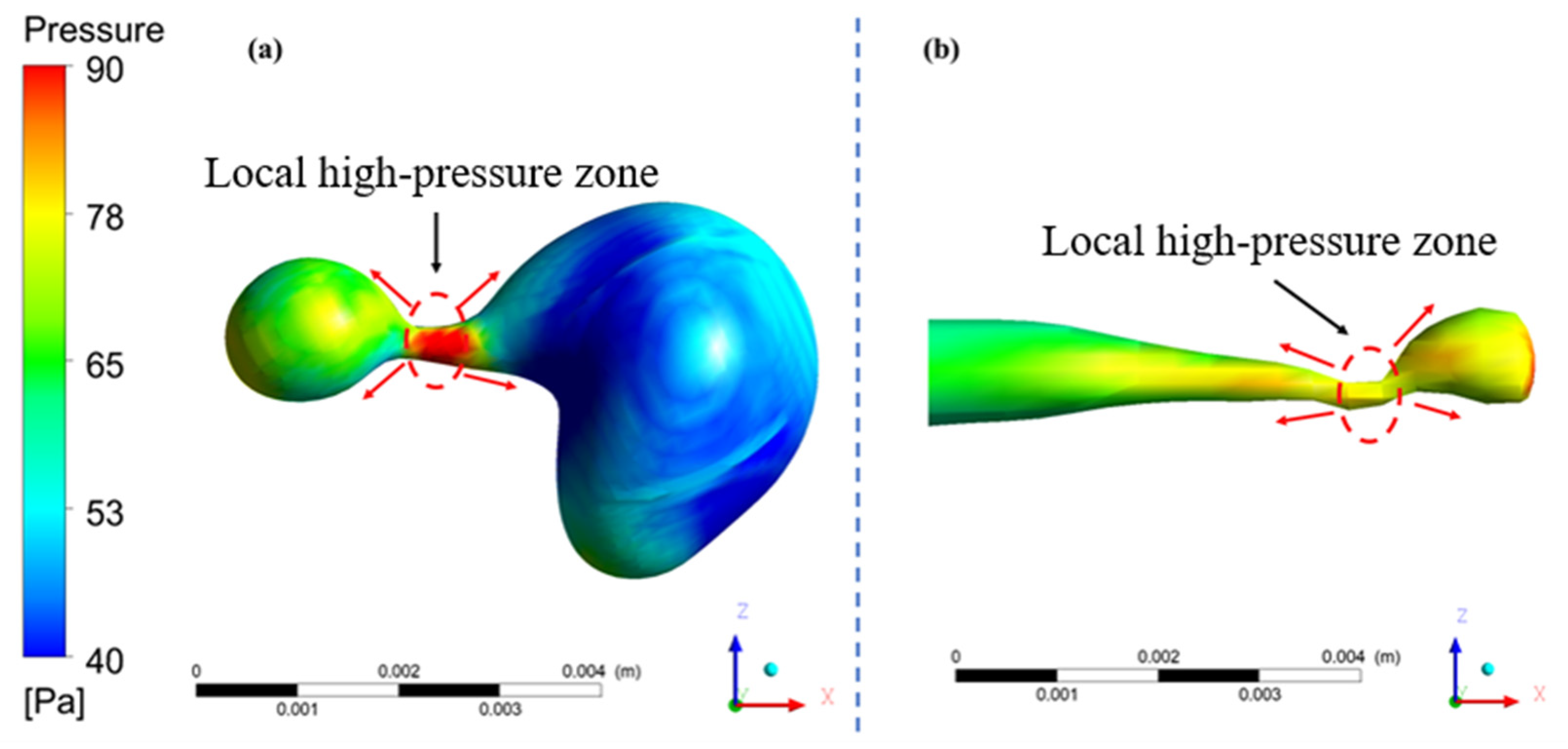

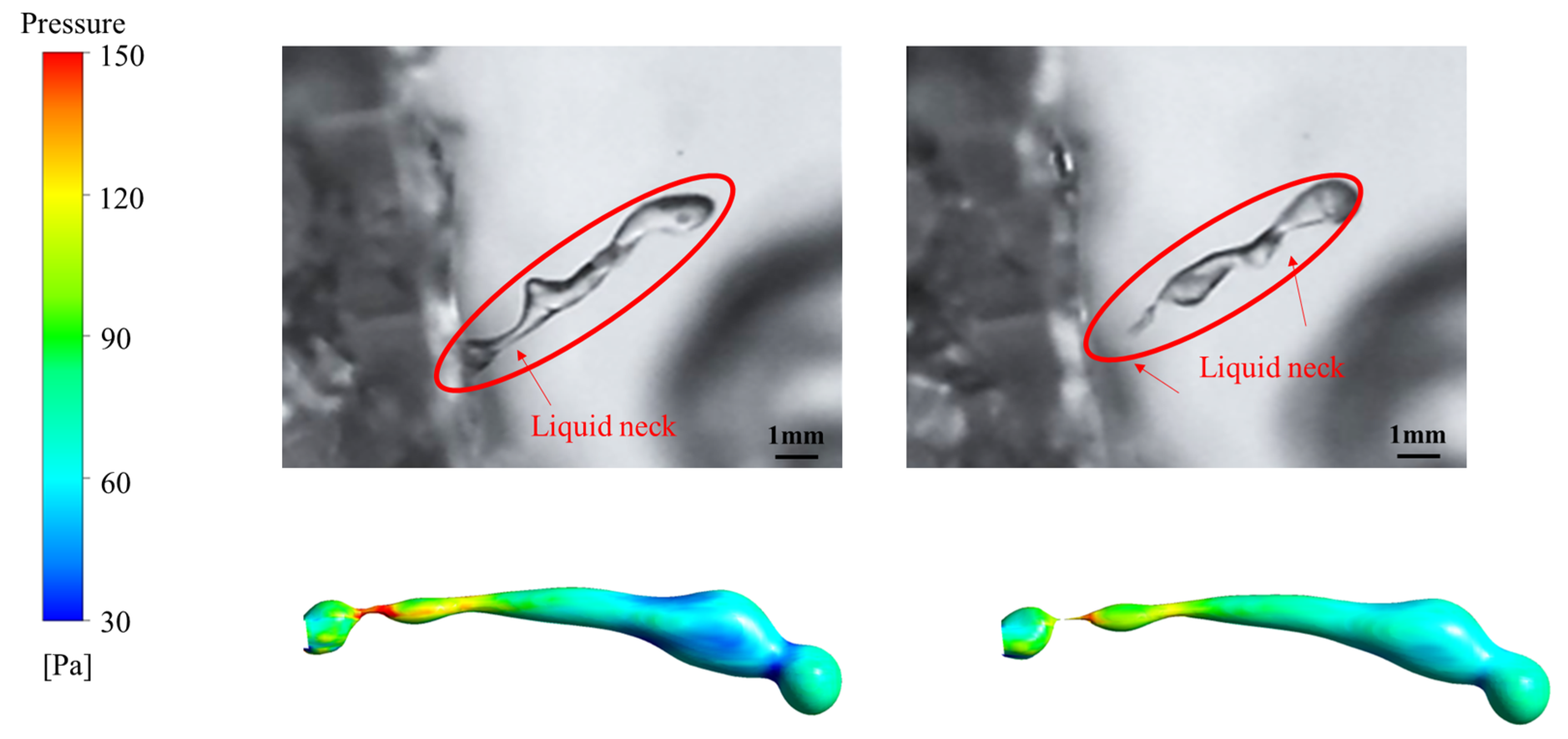

4.3. Formation Mechanism of Liquid Neck

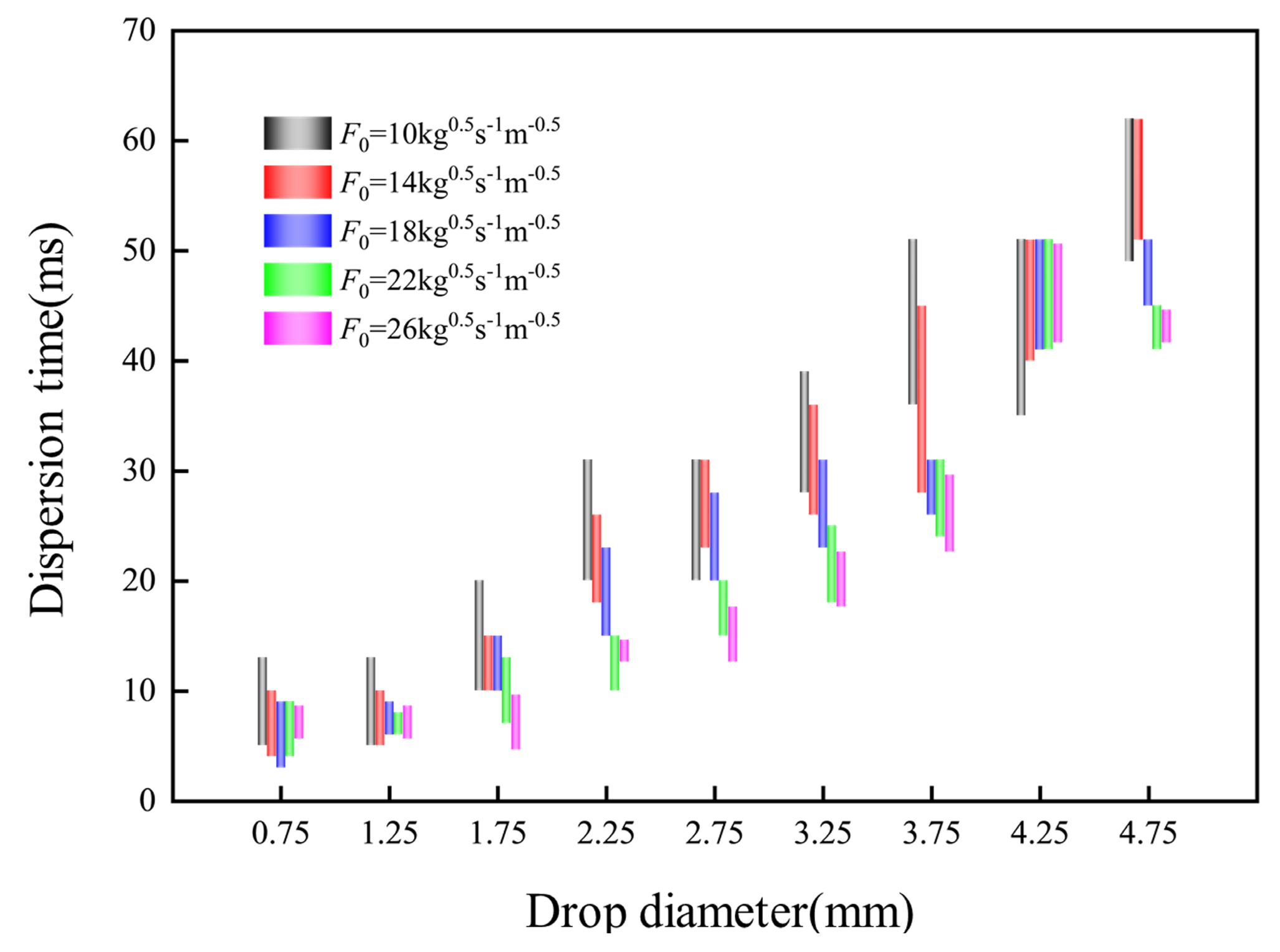

4.4. Dispersion Time

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tran, B.V.; Nguyen, D.D.; Ngo, S.I.; Lim, Y.I.; Kim, B.; Lee, D.H.; Go, K.S.; Nho, N.S. Hydrodynamics and simulation of air-water homogeneous bubble column under elevated pressure. Aiche J. 2019, 65, e16685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windhab, E.J.; Dressler, M.; Feigl, K.; Fischer, P.; Megias-Alguacil, D. Emulsion processing—From single-drop deformation to design of complex processes and products. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 2101–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yasin, M.; Park, S.; Chang, I.S.; Ha, K.S.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, C. Gas-liquid mass transfer coefficient of methane in bubble column reactor. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankova, N.; Tcholakova, S.; Denkov, N.D.; Ivanov, I.B.; Vulchev, V.D.; Danner, T. Emulsification in turbulent flow—1. Mean and maximum drop diameters in inertial and viscous regimes. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2007, 312, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, E.; Radhakrishnan, A.N.P.; bin Hasanudin, R.; Gavriilidis, A. Study of Liquid-Solid Mass Transfer and Hydrodynamics in Micropacked Bed with Gas-Liquid Flow. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 10489–10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, J.; Liu, H.Z.; Chen, J.J.; Li, X.Y.; Li, G.L.; Li, H.; Chen, K.Q. Self-inducing Reactors for Bioengineering. Acs Omega 2023, 8, 48613–48624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olujic, Z.; Jödecke, M.; Shilkin, A.; Schuch, G.; Kaibel, B. Equipment improvement trends in distillation. Chem. Eng. Process. 2009, 48, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.X.; Lei, Z.G. Modeling Flow-Guided Sieve Tray Hydraulics Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 4480–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.L.; Vidal, D.; Bertrand, F.; Chaouki, J. Multiscale multiphase phenomena in bubble column reactors: A review. Renew. Energ. 2019, 141, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Bhusare, V.H.; Joshi, J.B. Comparison of turbulence models for bubble column reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 164, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlollahi, F.; Wankat, P.C. Novel solvent exchange distillation column. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 184, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdipour, F.; Torkmahalleh, M.A.; Kamyabi, M.; Sotudeh-Gharebagh, R. On Solvent Losses in Amine Absorption Columns. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 11154–11164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H.; Knuutila, H.K.; Hillestad, M.; Svendsen, H.F. Characterization and modelling of aerosol droplet in absorption columns. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 58, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshdi, S.; Kasiri, N.; Hashemabadi, S.H.; Ivakpour, J. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of multiphase flow in packed sieve tray of distillation column. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Jing, D.; Zhou, H.; Li, S.W. Population balance of droplets in a pulsed disc and doughnut column with wettable internals. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 161, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, P.; Meller, R.; Schubert, M.; Hampel, U. Application of a hybrid multiphase CFD approach to the simulation of gas-liquid flow at a trapezoid fixed valve for distillation trays. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 193, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Zarazúa, G.; Sánchez-Ramirez, E.; Hernández-Vargas, E.A.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Ramírez, J.J.Q. Process intensification in bio-jet fuel production: Design and control of a catalytic reactive distillation column for oligomerization. Chem. Eng. Process. 2023, 193, 109548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtawy, H.M.; Mahapatra, N.R. Molecular Docking for Drug Discovery: Machine-Learning Approaches for Native Pose Prediction of Protein-Ligand Complexes. Lect. N. Bioinformat. 2014, 8452, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, X.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Yu, W. Combined trapezoid spray tray (CTST)-A novel tray with high separation efficiency and operation flexibility. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 112, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Chunli, L.; Jidong, L.; Zhenshan, X. Spray Characteristics Study of Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 2014, 16, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.D.; Jiang, K.; Dong, Z.Z.; Xu, J.X. Liquid lifting capability of directed combined trapezoid spray tray. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 550–553, 3059–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, Z.; He, L.; Liu, Z. Spray characteristics of combined trapezoid spray tray (CTST). J. Chem. Eng. Chin. Univ. 2014, 43, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulbah, C.; Kang, C.; Mao, N.; Zhang, W.; Shaikh, A.R.; Teng, S. A review of VOF methods for simulating bubble dynamics. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 2022, 154, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Lv, J. Gas elevating capability of combined trapezoid spray tray. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2002, 22, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Misyura, S.Y. Contact angle and droplet evaporation on the smooth and structured wall surface in a wide range of droplet diameters. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.T.; Wang, W.; Chu, N.; Wu, D.Z.; Xu, W.W. Numerical simulations and experimental validation on passive acoustic emissions during bubble formation. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 130, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadawi, A.; Donoghue, D.B.; Robinson, A.J.; Murray, D.B.; Delauré, Y.M.C. On the analysis of bubble growth and detachment at low Capillary and Bond numbers using Volume of Fluid and Level Set methods. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 90, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitavoli, M.; Khaleghi, E.; Babaei, H.; Mostofi, T.M.; Namazi, N. Modeling and prediction of metallic powder behavior in explosive compaction process by using genetic programming method based on dimensionless numbers. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process. Mech. Eng. 2019, 233, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, D.; Vikhansky, A.; Mohammadzadeh, O.; Ma, S.M. A model of droplet breakup in a turbulent flow for a high dispersed phase holdup. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 232, 116350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.U.; Kothe, D.B.; Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Cao, L.L.; Vanierschot, M.; Cheng, Z.F.; Blanpain, B.; Guo, M.X. Modelling of gas injection into a viscous liquid through a top-submerged lance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 212, 115359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Hosseini, S.H.; Rahimi, R. CFD study of weeping rate in the rectangular sieve trays. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2013, 44, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, R.; Chauhan, N.; Chauhan, R.P. Application of CFD modeling for indoor radon and thoron dispersion study: A review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2024, 272, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Castillo, A.-S.; Biard, P.-F.; Guihéneuf, S.; Paquin, L.; Amrane, A.; Couvert, A. Assessment of VOC absorption in hydrophobic ionic liquids: Measurement of partition and diffusion coefficients and simulation of a packed column. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Hosseini, S.H.; Rahimi, R. CFD and experimental studies of liquid weeping in the circular sieve tray columns. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2013, 91, 2333–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulaloglou, C.A.; Tavlarides, L.L. Description of interaction processes in agitated liquid-liquid dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1977, 32, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solsvik, J.; Tangen, S.; Jakobsen, H.A. On the constitutive equations for fluid particle breakage. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2013, 29, 241–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolai, B.; Prajapati, R.P. Kelvin–Helmholtz instability in sheared dusty plasma flows including dust polarization and ion drag forces. Phys. Scr. 2022, 97, 0656037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, R.B.; Olson, J.H. A moment methodology for coagulation and breakage problems: Part 2—Moment models and distribution reconstruction. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 2211–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakansson, A.; Crialesi-Esposito, M.; Nilsson, L.; Brandt, L. A criterion for when an emulsion drop undergoing turbulent deformation has reached a critically deformed state. Colloid. Surface A 2022, 648, 129213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, B.; Jing, S.; Lan, W.J.; Li, S.W. Experimental study on drop breakup time and breakup rate with drop swarms in a stirred tank. Aiche J. 2021, 67, e17065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herø, E.H.; La Forgia, N.; Solsvik, J.; Jakobsen, H.A. Single drop breakage in turbulent flow: Statistical data analysis. Chem. Eng. Sci. X 2020, 8, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashar, M.; Arlov, D.; Carlsson, F.; Innings, F.; Andersson, R. Single droplet breakup in a rotor-stator mixer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 181, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, B.; Jing, S.; Lan, W.; Li, S. Modeling study on drop breakup time in turbulent dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 238, 116599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, K.; Ram Prasad, P. Internal waves and Rayleigh–Taylor instability in magnetized compressible strongly coupled dusty plasmas. J. Plasma Phys. 2024, 90, 905900412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Dimensions |

|---|---|

| Bottom perforated plate | 200 × 100 mm |

| Rectangular opening in the bottom perforated plate | 20 × 70 mm |

| Height of verflow weir | 10 mm |

| Pore diameter in the spraying plate | 5 mm |

| Vertical height of the spraying plate | 70 mm |

| Inclination angle of the spraying plate | 8° |

| Bottom gap height | 6 mm |

| Top gap height | 20 mm |

| Length of plate into cap | 10 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Yi, K.; Li, Q.; Su, W.; Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, X. Drop Dispersion Through Arrayed Pores in the Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray (CTST). Processes 2025, 13, 4050. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124050

Wang H, Yi K, Li Q, Su W, Hu Y, Li C, Yu X. Drop Dispersion Through Arrayed Pores in the Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray (CTST). Processes. 2025; 13(12):4050. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124050

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Honghai, Kunlong Yi, Quancheng Li, Weiyi Su, Yuqi Hu, Chunli Li, and Xiong Yu. 2025. "Drop Dispersion Through Arrayed Pores in the Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray (CTST)" Processes 13, no. 12: 4050. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124050

APA StyleWang, H., Yi, K., Li, Q., Su, W., Hu, Y., Li, C., & Yu, X. (2025). Drop Dispersion Through Arrayed Pores in the Combined Trapezoid Spray Tray (CTST). Processes, 13(12), 4050. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124050