Analysis of Sedimentation Behavior and Influencing Factors of Solid Particles in CO2 Fracturing Fluid

Abstract

1. Introduction

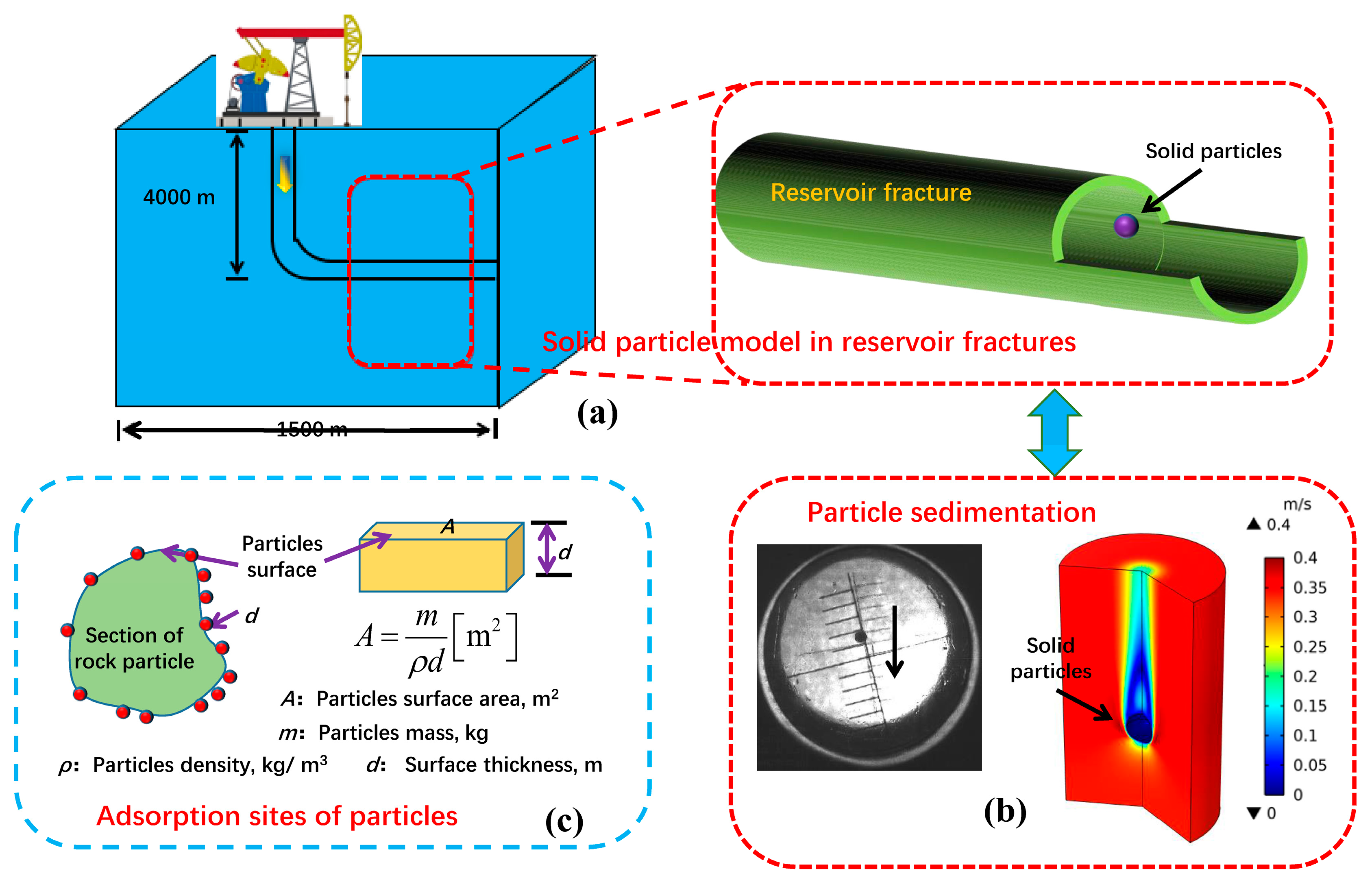

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Temperature Fields of Fluids and Rock Solids in Geological Reservoirs

2.1.1. Solid–Liquid Heat Transfer Equation Considering Fluid Viscosity

2.1.2. Heat Transfer Equation in a Wellbore Considering Seepage and Thermal Convection

2.2. Continuity Equation of CO2 Fracturing Fluid in Geological Reservoirs

2.3. Model Boundary Conditions Between Particles and Fracturing Fluid in Geological Reservoirs

2.4. Construction of a Multi-Coupled Performance Evaluation Device for CO2 Fracturing Fluid

2.5. Model Decoupling, Solution and Adaptability Validation of Investigation Methodology

2.5.1. Model Decoupling, Solution

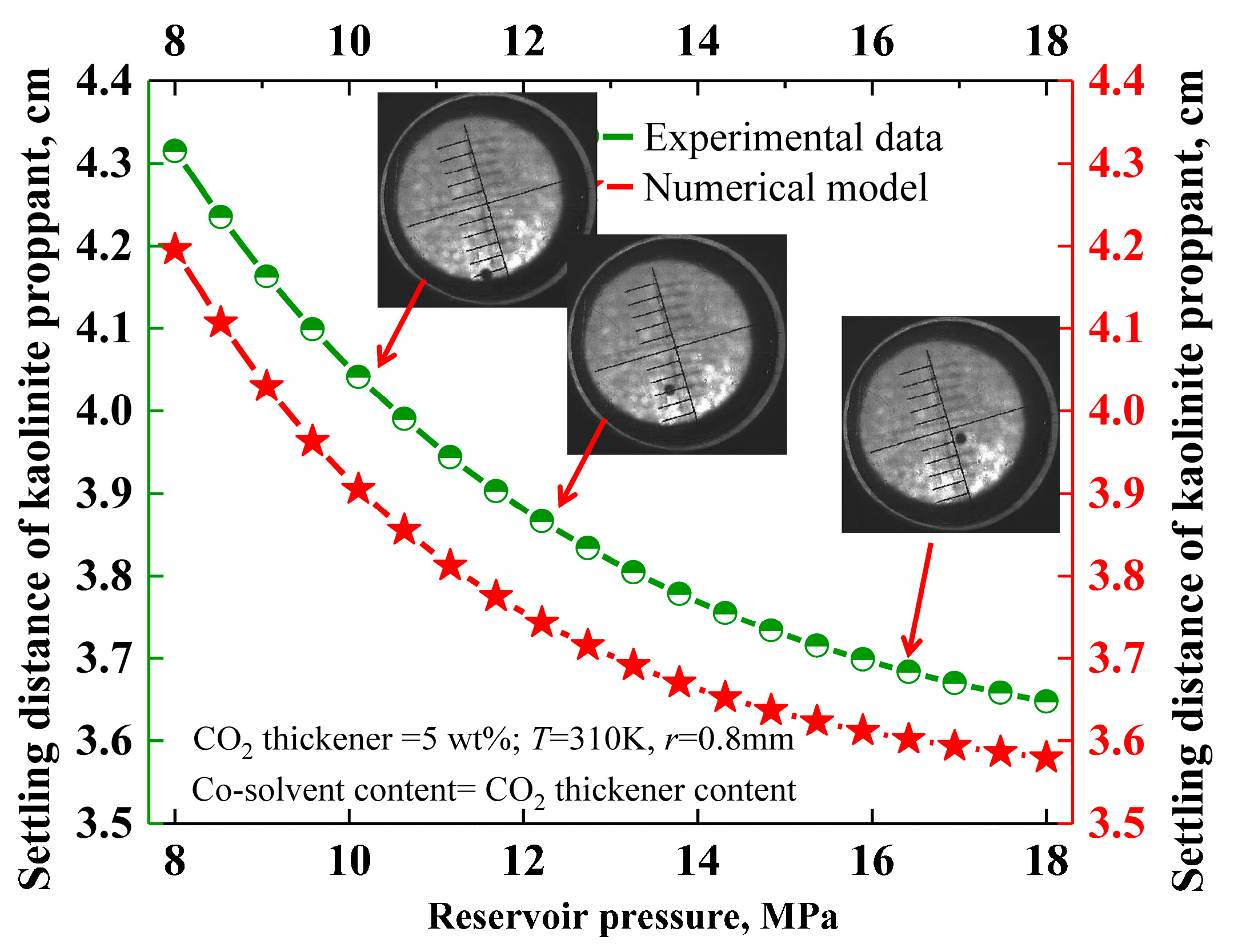

2.5.2. Adaptability Validation of Investigation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

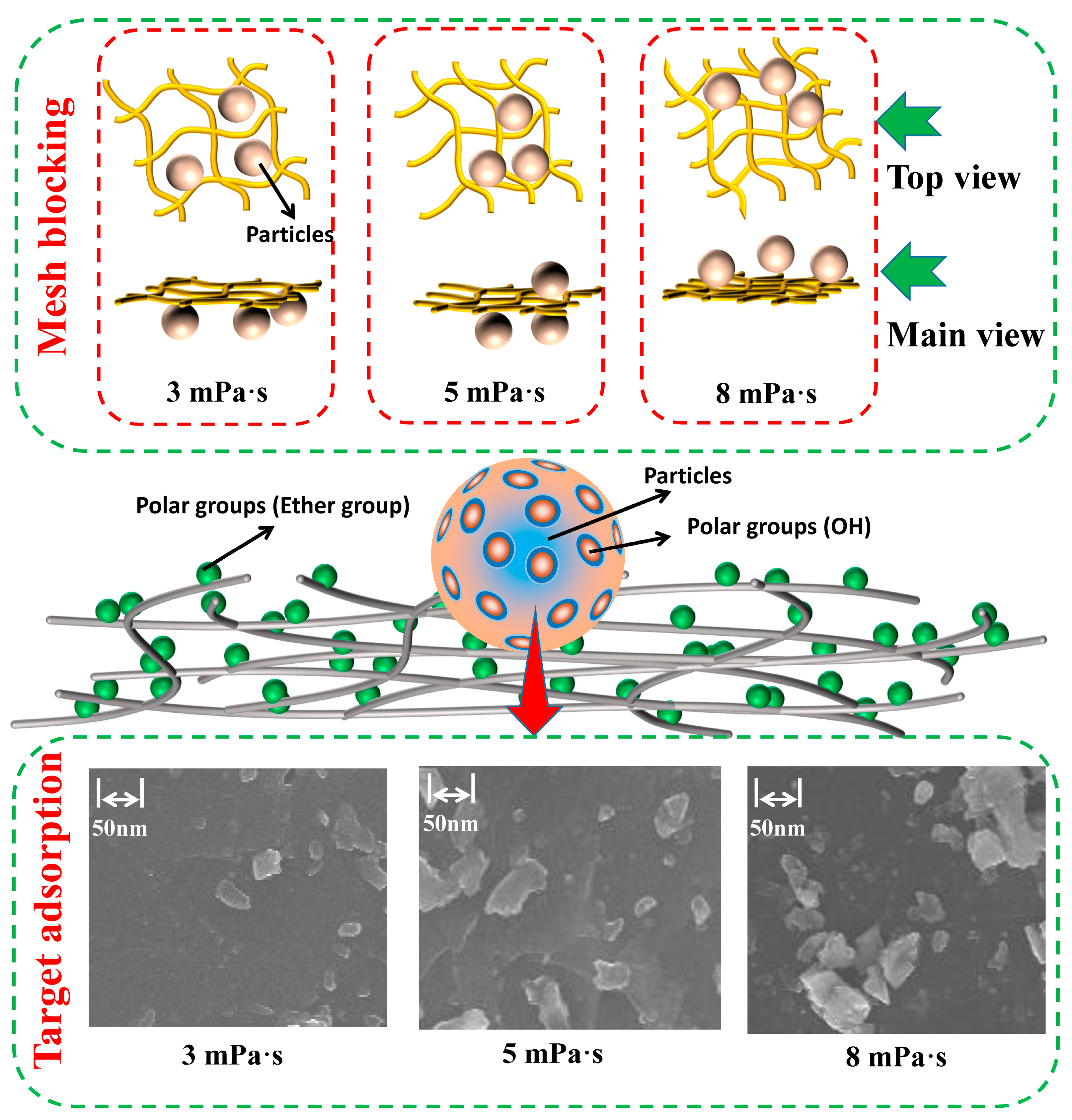

3.1. The Influence of CO2 Fluid Viscosity on Particle Settling Behavior

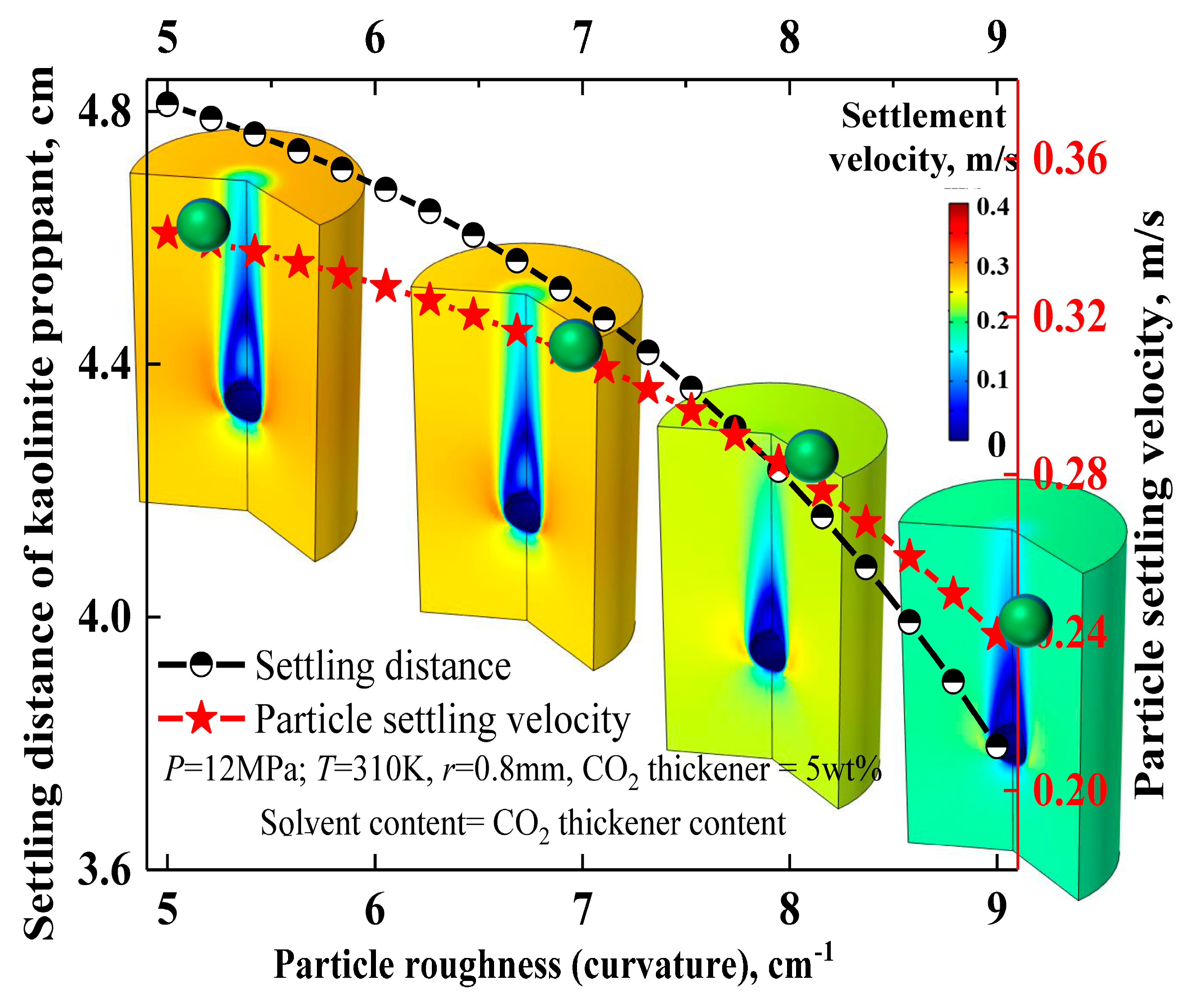

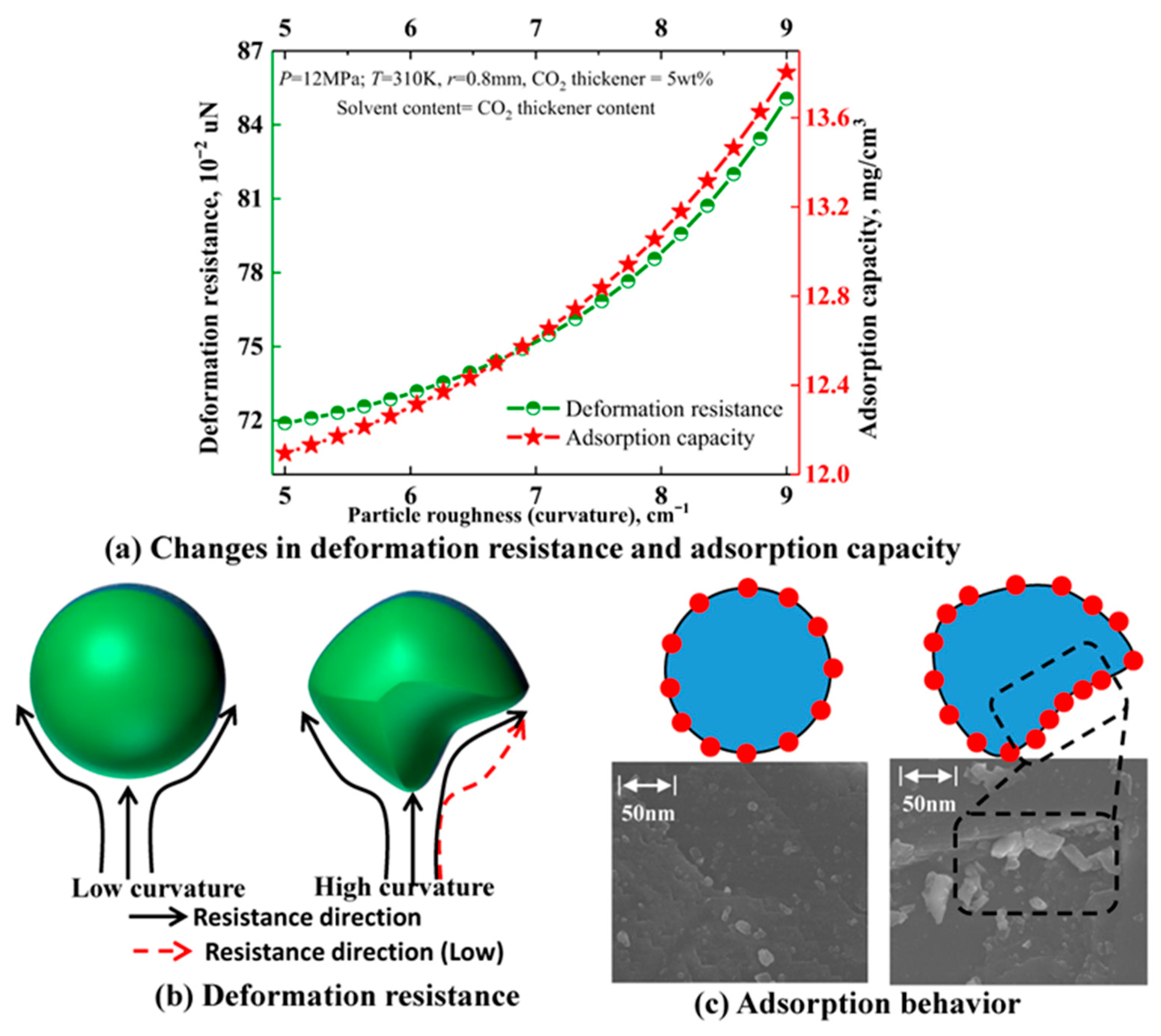

3.2. Influence and Mechanism Analysis of Particle Roughness on Settlement Behavior

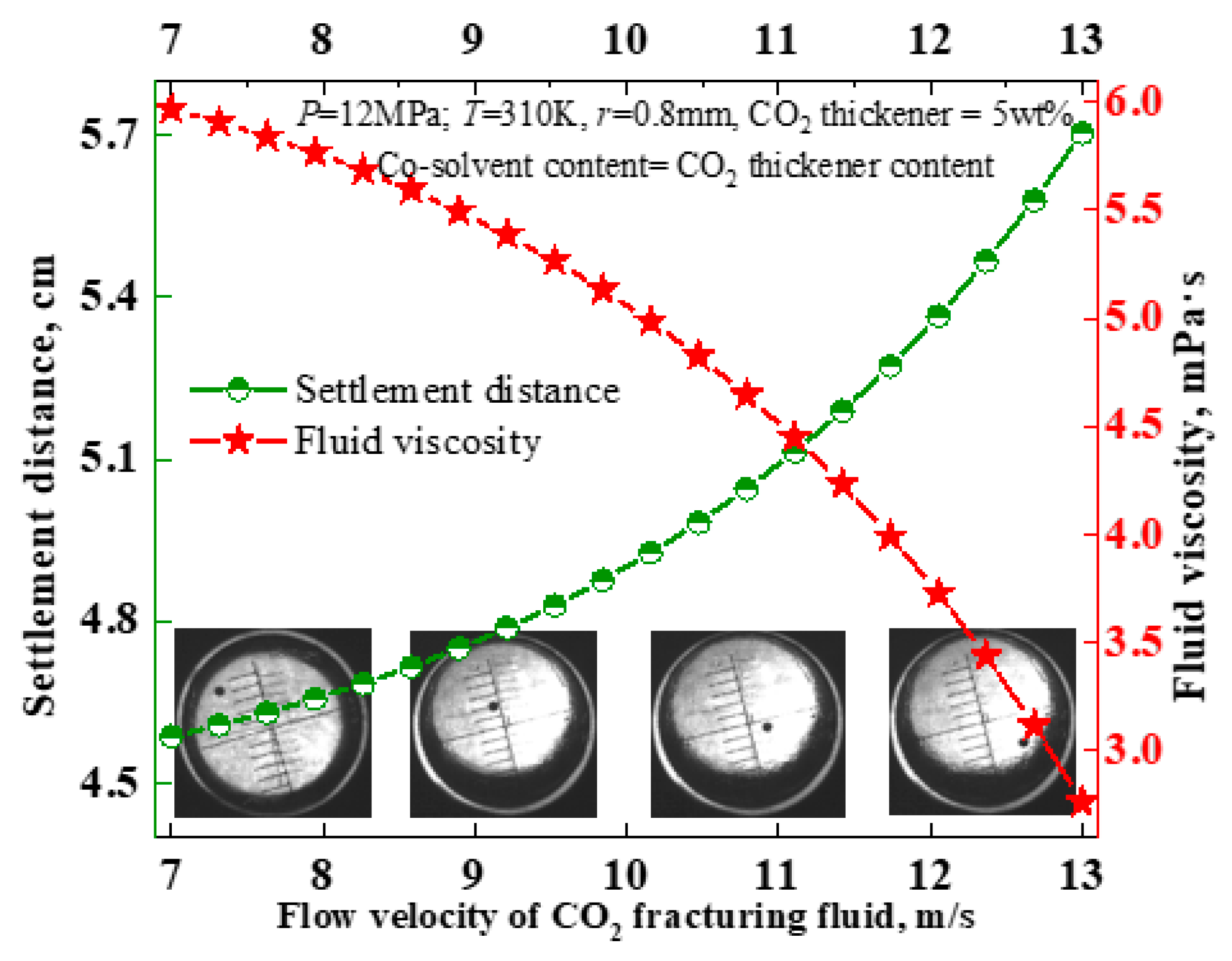

3.3. Effect of Lateral Fluid Flow on the Settling of Solid Particles

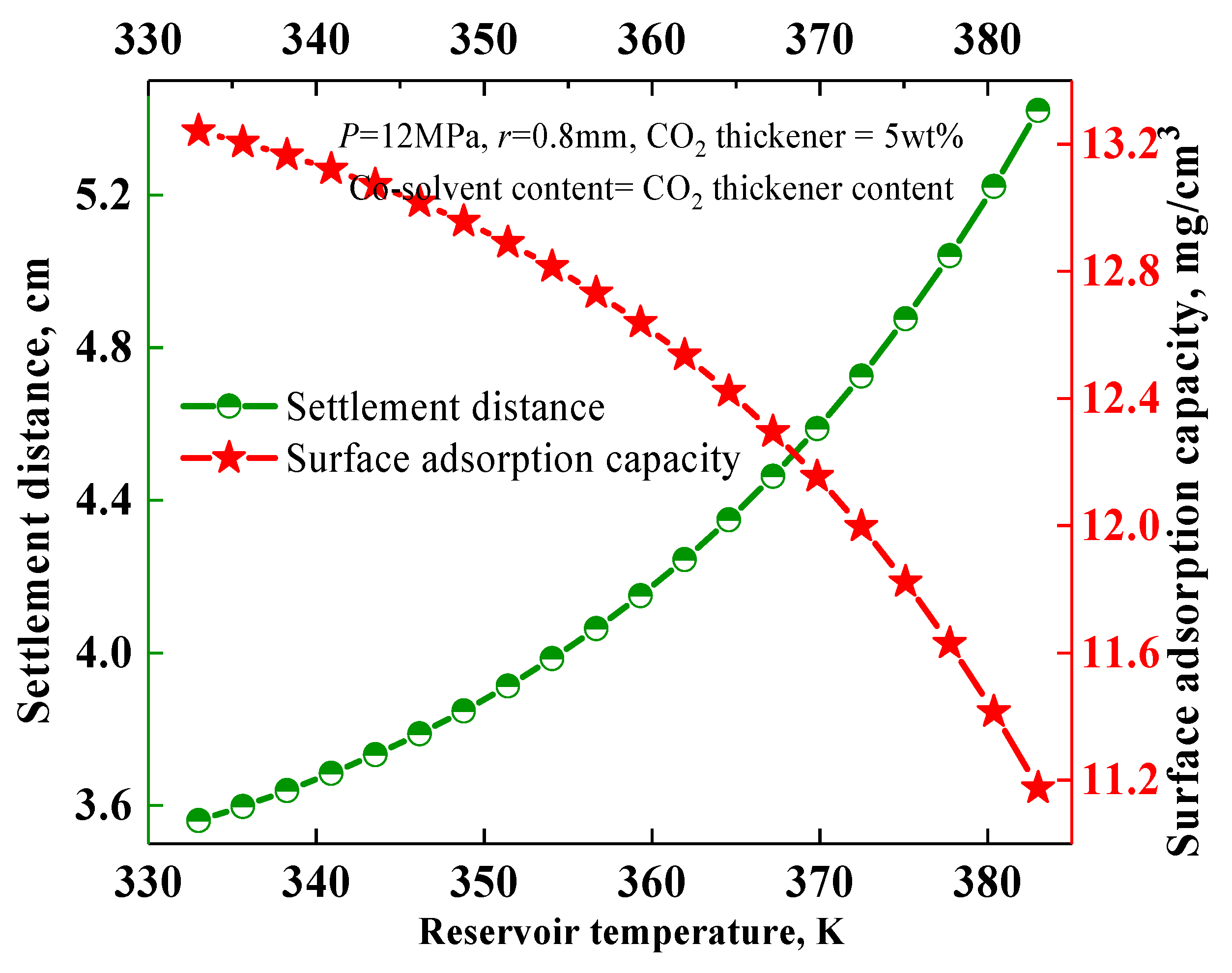

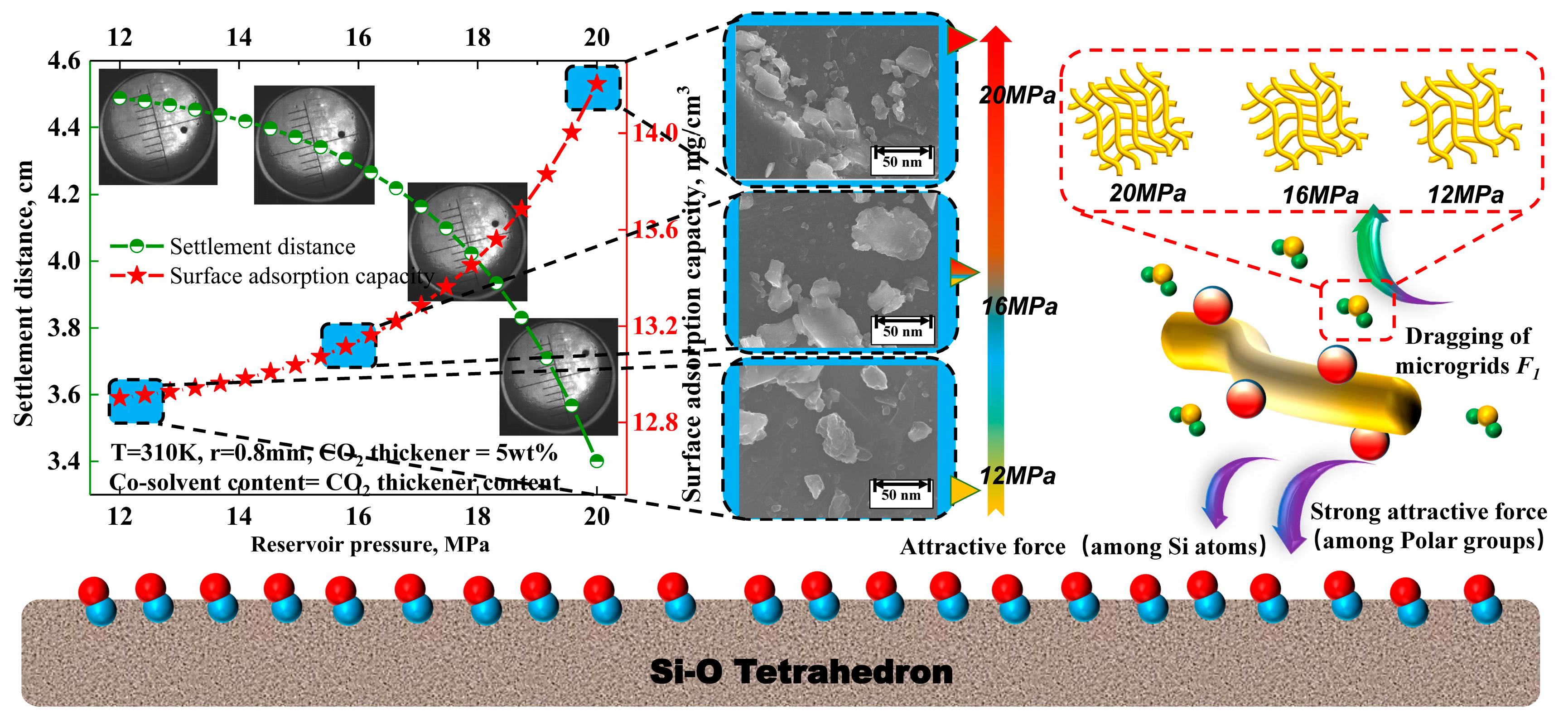

3.4. Effect of Reservoir Temperature and Pressure on the Settling Behavior of Solid Particles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wanniarachchi, W.A.M.; Ranjith, P.G.; Perera, M.S.A. Shale gas fracturing using foam-based fracturing fluid: A review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satea, A.; Tian, Y.; Kou, Z.; Kang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. A technical review of chemical reactions during CCUS-EOR in different reservoirs. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Elsworth, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Liu, Y. The influence of fracturing fluids on fracturing processes: A comparison between water, oil and SC-CO2. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanninen, M.F. Applications of dynamic fracture mechanics for the prediction of crack arrest in engineering structures. Int. J. Fract. 1985, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wei, J.; Ansari, U. Numerical simulation of fracture reorientation during hydraulic fracturing in perforated horizontal well in shale reservoirs. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2018, 40, 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, K.D.; Michalis, V.K.; Peristeras, L.D.; Vasileiadis, M.; Striolo, A.; Economou, I.G. Molecular dynamics simulation of water-based fracturing fluids in kaolinite slit pores. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 17170–17183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, C.; Liao, H. Simulation analysis of an impeller percussive drilling tool based on rotation law. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Zhang, S.; Elsworth, D.; Liu, H.; Sun, B.; Geng, X. Review of fundamental studies of CO2 fracturing: Fracture propagation, propping and permeating. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S.; Wei, C. A review of experimental apparatus for supercritical CO2 fracturing of shale. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, K.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, H. Numerical model of CO2 fracturing in naturally fractured reservoirs. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 244, 107548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, H.Z.; Li, G.S.; Wang, B.; Chang, L.; Tian, G.H.; Zhao, C.M.; Zheng, Y. Fundamental study and utilization on supercritical CO2 fracturing developing unconventional resources: Current status, challenge and future perspectives. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 2757–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J. Effects of Geological and Fluid Characteristics on the Injection Filtration of Hydraulic Fracturing Fluid in the Wellbores of Shale Reservoirs: Numerical Analysis and Mechanism Determination. Processes 2025, 13, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y. Sediment Instability Caused by Gas Production from Hydrate-Bearing Sediment in Northern South China Sea by Horizontal Wellbore: Sensitivity Analysis. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 1667–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, Y. Study on the performance degradation of sandstone under acidification. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 28333–28340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. The carrying behavior of water-based fracturing fluid in shale reservoir fractures and molecular dynamics of sand-carrying mechanism. Processes 2024, 12, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreipl, M.P.; Kreipl, A.T. Hydraulic fracturing fluids and their environmental impact: Then, today, and tomorrow. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liao, H.; Xu, Y.; Niu, J.; Yang, L. Theoretical investigation of the energy transfer efficiency under percussive drilling loads. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, A.; Aljawad, M.S.; Alyousef, Z.; Almajid, M.M. A review of foam-based fracturing fluids applications: From lab studies to field implementations. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 95, 104236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Reservoir Science: A Multi-Coupling Communication Platform to Promote Energy Transformation, Climate Change and Environmental Protection. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Pan, J.; Anwaier, M.; Wu, J.; Xiao, P.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, D. Effect of nano-SiO2 on the flowback-flooding integrated performance of water-based fracturing fluids. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 379, 121686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongole, K.; Sun, Z.; Yao, J.; Mehmood, A.; Yueying, W.; Mboje, J.; Xin, Y. Multifracture response to supercritical CO2-EGS and water-EGS based on thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling method. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 7173–7196. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Feng, X. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical-damage modeling of cold-water injection in deep geothermal reservoirs. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouya, A.; Yazdi, P.B. A damage-plasticity model for cohesive fractures. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 73, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.R. Heat Transfer effects in deep well fracturing. J. Pet. Technol. 1971, 23, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.P.; Ranjith, P.G.; Perera, M.S.A.; Li, X.; Zhao, J. Simulation of flow behaviour through fractured unconventional gas reservoirs considering the formation damage caused by water-based fracturing fluids. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 57, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, D.; Wen, H.; Cheng, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Hu, B. Enhancing coalbed methane recovery with liquid CO2 fracturing in underground coal mine: From experiment to field application. Fuel 2021, 290, 119793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, V.; Ahmadi, N.; Rezazadeh, S.; Sadeghiazad, M. Numerical analysis of thermal performance in a finned cylinder for latent heat thermal system (LHTS) applications. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2013, 31, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Usman Tahir, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z. Effect of thickener and reservoir parameters on the filtration property of CO2 fracturing fluid. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 42, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Foster, G.; Lei, C. Study on the optimization of silicone copolymer synthesis and the evaluation of its thickening performance. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 8770–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. The influence of stress and natural fracture on a stimulated deep shale reservoir using the boundary element method. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, F.; Yan, D.; Liao, H.; Niu, J. Characteristic analysis of a HDR percussive drilling tool with sinusoidal impact load. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 238, 212847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kobina, F. The Influence of Geological Factors and Transmission Fluids on the Exploitation of Reservoir Geothermal Resources: Factor Discussion and Mechanism Analysis. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Tian, S.; Song, X.; Lu, P.; Wang, M. A unified model for wellbore flow and heat transfer in pure CO2 injection for geological sequestration, EOR and fracturing operations. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 2017, 57, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, Y.; Theuerkauf, J.; Jacob, K.V.; Umbanhowar, P.B.; Lueptow, R.M. Modeling segregation of polydisperse granular materials in hopper discharge. Powder Technol. 2020, 374, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jin, G.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Ma, H.; Bai, S.; Song, J. A coarse-grained CFD-DEM method for efficient simulation of fluid-solid coupling failure process in geomaterials: Methodology and verification. Powder Technol. 2025, 467, 121483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Shi, X.; Ni, H.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Q. Review of CO2 fracturing and carbon storage in shale reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 15913–15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.; Viswanathan, H.; Currier, R.; Gupta, R. CO2 as a fracturing fluid: Potential for commercial-scale shale gas production and CO2 sequestration. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 7780–7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; San, J.; Li, Q.; Foster, G. Synthetic process on hydroxyl-containing polydimethylsiloxane as a thickener in CO2 fracturing and thickening performance test. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2018, 40, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chang, C. Study on the characteristics of CO2 fracturing rock damage based on fractal theory. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 134, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, Z.; Yang, F.; Ma, Z. Improved equation of state model for the phase behavior of CO2–hydrocarbon coupling nanopore confinements. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.S.; Carey, J.W.; Currier, R.P.; Hyman, J.D.; Kang, Q.; Karra, S.; Jiménez-Martínez, J.; Porter, M.L.; Viswanathan, H.S. Shale gas and non-aqueous fracturing fluids: Opportunities and challenges for supercritical CO2. Appl. Energy 2015, 147, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.J.; Choo, J.; Yun, T.S. Liquid CO2 fracturing: Effect of fluid permeation on the breakdown pressure and cracking behavior. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 3407–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Huang, J. Dynamics study of self-pulling self-rotating jet drill bit in natural gas hydrate reservoirs radial horizontal well drilling. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 244, 213490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Hu, Z.; Niu, J.; Shi, Y. Numerical simulation of proppant transport from a horizontal well into a perforation using computational fluid dynamics. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2023, 10, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Salimzadeh, S.; Zhang, Q.B. A 3D coupled numerical simulation of energised fracturing with CO2: Impact of CO2 phase on fracturing process. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 182, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, H.; Fu, G.; Tian, L.; Liu, S. CO2 gas fracturing: A novel reservoir stimulation technology in low permeability gassy coal seams. Fuel 2017, 203, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Zhu, B.; Sepehrnoori, K.; Shi, L.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X. Key problems and solutions in supercritical CO2 fracturing technology. Front. Energy 2019, 13, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Feng, W.; Siwei, M.; Yongwei, D. Fracturing with carbon dioxide: Application status and development trend. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Quan, X.; Tian, S.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, X. Permeability-enhancing technology through liquid CO2 fracturing and its application. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruess, K. Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) using CO2 as working fluid—A novel approach for generating renewable energy with simultaneous sequestration of carbon. Geothermics 2006, 35, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Cao, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. The Crack Propagation Behaviour of CO2 Fracturing Fluid in Unconventional Low Permeability Reservoirs: Factor Analysis and Mechanism Revelation. Processes 2025, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Bai, B.; Zhang, J.; Lili, C.; Forson, K. Adsorption behavior and mechanism analysis of siloxane thickener for CO2 fracturing fluid on shallow shale soil. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 376, 121394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, W.; Wei, C.; Elsworth, D.; Wang, J. Microcrack-based geomechanical modeling of rock-gas interaction during supercritical CO2 fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 164, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhu, L.; Guo, M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, G.; Lin, L.; He, L.; Liao, Y.; He, H.; Gong, J. Assessment of CO2 fracturing in China’s shale oil reservoir: Fracturing effectiveness and carbon storage potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.Z.; Jiang, P.X.; Xu, R.N. System thermodynamic performance comparison of CO2-EGS and water-EGS systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 61, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Cheng, Y. Wellhead stability during development process of hydrate reservoir in the Northern South China Sea: Evolution and mechanism. Processes 2025, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, B.; Sun, X. Calculation of temperature in fracture for carbon dioxide fracturing. SPE J. 2016, 21, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, B.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, W. Optimization design of hydraulic parameters for supercritical CO2 fracturing in unconventional gas reservoir. Fuel 2019, 235, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Guo, T.; He, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Qu, Z. Study on the cracking mechanism of hydraulic and supercritical CO2 fracturing in hot dry rock under thermal stress. Energy 2021, 221, 119886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, N.; Shen, G.; Chang, X.; Yu, W.; Tang, Z.; Chen, W.; Wei, W.; et al. Fracturing with carbon dioxide: From microscopic mechanism to reservoir application. Joule 2019, 3, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, G.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Pan, Y. Thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling simulation for fracture propagation in CO2 fracturing based on phase-field model. Energy 2023, 284, 128629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X.; Hu, D.; Zhou, H.; Li, D. A preliminary experimental and numerical study on the applicability of liquid CO2 fracturing in sparse sandstone. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 7315–7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, F.; Qingchao, L.; Qiang, L.; Jingjuan, W.; Fuling, W.; Chuanliang, Y. Numerical Simulation Investigation of Fracture Propagation Behavior Patterns and Sensitivity Factors of Oil Shale Reservoirs in the Xunyi Region Considering the Influence of Natural Fracture. Geofluids 2025, 2025, 2762142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Cai, Z.; Ming, H.; Zhang, F.; He, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, D. Calculation Models for Vapor-liquid Phase Equilibrium in Mixture Systems of CO2 Containing Impurities. Pet. New Energy 2024, 36, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Takuma, K.; Maeda, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Ogata, S.; Sakaguchi, K.; Pramudyo, E.; Fukuda, D.; Wang, J.; Osato, K.; Terai, A.; et al. CO2 fracturing of volcanic rocks under geothermal conditions: Characteristics and process. Geothermics 2024, 120, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Pan, H.; Fujii, Y. Study on energy distribution and attenuation of CO2 fracturing vibration from coal-like material in a new test platform. Fuel 2024, 356, 129584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaali, M.; Ziaei-Rad, V.; Shen, Y. Numerical modeling of CO2 fracturing by the phase field approach. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 70, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Forson, K.; Zhang, J. Effect of reservoir characteristics and chemicals on filtration property of water-based drilling fluid in unconventional reservoir and mechanism disclosure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 55034–55043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Luo, W.; Teng, B. Study on the Influence Mechanism of Natural Fracture Characteristics on EUR of Gas Wells in Horizontal Well Development of Deep Shale Gas. Pet. New Energy 2025, 37, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Lian, H.; Liang, W.; Wu, P.; Jiang, Y.; Song, X. Experimental study of supercritical CO2 fracturing across coal–rock interfaces. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, A.; Lushpeev, V.; Sokolov, A.; Sultanbekov, R.; Tyan, Y.; Ovchinnikov, E.; Islamov, S. Hartmann–sprenger energy separation effect for the quasi-isothermal pressure reduction of natural gas: Feasibility analysis and numerical simulation. Energies 2024, 17, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Xu, N.; Wang, Y.; Bai, B. Settling behavior and mechanism analysis of kaolinite as a fracture proppant of hydrocarbon reservoirs in CO2 fracturing fluid. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 724, 137463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z. Coupled physical–chemical effects of CO2 on rock properties and breakdown during intermittent CO2-hybrid fracturing. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 1665–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cheng, C.; Ding, C.; Song, J.; Hu, D.; Zhou, H. Comparisons of fracturing mechanism of tight sandstone using liquid CO2 and water. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 94, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Zhang, F.; Tao, J.; Jin, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, H. Carbon storage potential of shale reservoirs based on CO2 fracturing technology. Engineering 2025, 48, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ansari, U.; Song, B. Establishment and evaluation of strength criterion for clayey silt hydrate-bearing sediments. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2018, 40, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, C.; Wen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, X.; Wu, J. Thoughts on the development of CO2-EGR under the background of carbon peak and carbon neutrality. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2023, 10, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X. Phase state control model of supercritical CO2 fracturing by temperature control. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 118, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzer, A.; Sommerfeld, M. New simple correlation formula for the drag coefficient of non-spherical particles. Powder Technol. 2008, 184, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Levenspiel, O. Drag coefficient and terminal velocity of spherical and nonspherical particles. Powder Technol. 1989, 58, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, N.; Li, M. Staged numerical simulations of supercritical CO2 fracturing of coal seams based on the extended finite element method. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 65, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.; Feng, R.; Ali, M.; Bhatti, M.A.; Giwelli, A.; Keshavarz, A.; Xie, Q.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Supercritical CO2-Shale interaction induced natural fracture closure: Implications for scCO2 hydraulic fracturing in shales. Fuel 2022, 313, 122682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbis, S.J.; Taylor, J.L. The utility of CO2 as an energizing component for fracturing fluids. SPE Prod. Eng. 1986, 1, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, T.; Song, G.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Han, H.; Li, Y. Experimental Study on Temperature Drop Characteristics of Supercritical CO2 Leakage on Offshore Platform. Pet. New Energy 2024, 36, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Ansari, U.; Liu, Y.; Yan, C.; Lei, C. Development and verification of the comprehensive model for physical properties of hydrate sediment. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; Pang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, G.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Y. Dynamics simulation of the effect of cosolvent on the solubility and tackifying behavior of PDMS tackifier in supercritical CO2 fracturing fluid. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 662, 130985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, F.; Xu, Y.; He, J.; Deng, D.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, C. Dynamics study of hot dry rock percussive drilling tool based on the drill string axial vibration. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 246, 213599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Gao, R.; Zeng, F.B.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Liang, Z. Rheological properties study of foam fracturing fluid using CO2 and surfactant. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 170, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, C. A molecular dynamics investigation into the polymer tackifiers in supercritical CO2 fracturing fluids under wellbore conditions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 212, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Jing, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Phase-field simulation of CO2 fracturing crack propagation in thermo-poroelastic media. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 187, 106052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Si, N.; Guan, W.; Lin, J. Effects of liquid CO2 phase transition fracturing on mesopores and micropores in coal. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 10016–10025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajri, S.; Negash, B.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Haroun, M.; Al-Shami, T.M. Perspective Review of polymers as additives in water-based fracturing fluids. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7431–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Huang, Q.; Wang, G.; Bing, W.; Li, J. Experimental study of the influence of water-based fracturing fluids on the pore structure of coal. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 88, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Morris, G.L. Reservoir sedimentation. II: Reservoir desiltation and long-term storage capacity. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1992, 118, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S. Soil erosion, sediment yield and sedimentation of reservoir: A review. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyu, Z.; Hongming, T.; Senlin, Y.; Gongyang, C.; Feng, Z.; Shiyu, X. Effect of fracture roughness on transport of suspended particles in fracture during drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Juanes, R. Preferential mode of gas invasion in sediments: Grain-scale mechanistic model of coupled multiphase fluid flow and sediment mechanics. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114, B08101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørlykke, K. Relationships between depositional environments, burial history and rock properties. Some principal aspects of diagenetic process in sedimentary basins. Sediment. Geol. 2014, 301, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, J.W. Hydraulic fracturing during the formation and deformation of a basin: A factor in the dewatering of low-permeability sediments. AAPG Bull. 2001, 85, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Luo, X.; Zhang, W. Integrated geological-geophysical characterizations of deeply buried fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoirs in Ordovician strata, Tarim Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 99, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Sui, W.; Qi, J. Experimental investigation on chemical grouting of inclined fracture to control sand and water flow. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 83, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, R.; Wu, X. Multi-timescale capacity configuration optimization of energy storage equipment in power plant-carbon capture system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 227, 120371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.; Yin, X.; Kneafsey, T.; Johanson, B.; Alqahtani, N.; Miskimins, J.; Patterson, T.; Wu, Y.S. Cryogenic fracturing for reservoir stimulation–Laboratory studies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2014, 124, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Yang, S.H.I.; Fujian, Z.H.O.U.; Xiongfei, L.I.U.; Xianyou, Y.A.N.G.; Xiangtong, Y.A.N.G. High efficiency reservoir stimulation based on temporary plugging and diverting for deep reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahov, G.M.; Abbasov, E.M.; Jiang, R. The novel technology for reservoir stimulation: In situ generation of carbon dioxide for the residual oil recovery. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. 2021, 11, 2009–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gou, B.; Qin, N.; Zhao, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, K.; Ren, J. An innovative concept on deep carbonate reservoir stimulation: Three-dimensional acid fracturing technology. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2020, 7, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xie, H.; Hu, J.; Li, C. A critical review of the experimental and theoretical research on cyclic hydraulic fracturing for geothermal reservoir stimulation. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianchun, G.; Cong, L.; Yong, X.; Jichuan, R.; Chaoyi, S.; Yu, S. Reservoir stimulation techniques to minimize skin factor of Longwangmiao Fm gas reservoirs in the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2014, 1, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, L.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Feng, W. Recent advances in reservoir stimulation and enhanced oil recovery technology in unconventional reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, G.; Guo, W.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y. Enhancement of gas production from natural gas hydrate reservoir by reservoir stimulation with the stratification split grouting foam mortar method. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 81, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y. A novel stimulation strategy for developing tight fractured gas reservoir. Petroleum 2018, 4, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y. Coalbed methane reservoir stimulation using guar-based fracturing fluid: A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 66, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reservoir pressure/MPa | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 |

| Chemical bond length/um | 67 | 65 | 61 | 53 |

| Chemical bond energy/×10−6 J·mol | 1.6 | 1.75 | 2.08 | 2.64 |

| Grid density/×103 root·um3 | 2.43 | 2.51 | 2.64 | 2.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; You, D.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Analysis of Sedimentation Behavior and Influencing Factors of Solid Particles in CO2 Fracturing Fluid. Processes 2025, 13, 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124049

Li Q, You D, Li Q, Wang F, Wang Y, Yang Y. Analysis of Sedimentation Behavior and Influencing Factors of Solid Particles in CO2 Fracturing Fluid. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124049

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qiang, Dandan You, Qingchao Li, Fuling Wang, Yanling Wang, and Yandong Yang. 2025. "Analysis of Sedimentation Behavior and Influencing Factors of Solid Particles in CO2 Fracturing Fluid" Processes 13, no. 12: 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124049

APA StyleLi, Q., You, D., Li, Q., Wang, F., Wang, Y., & Yang, Y. (2025). Analysis of Sedimentation Behavior and Influencing Factors of Solid Particles in CO2 Fracturing Fluid. Processes, 13(12), 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124049