Abstract

Artificial underground compressed air energy storage (CAES) caverns have the advantages of large capacity and flexible location. However, the location selection of CAES in conditions of hard shallowly buried rock requires comprehensive consideration of multi-field coupling effects and engineering constraints, and the decision-making process involves multiple criteria and strong uncertainty. Aimed at addressing the problems of the evaluation index system not being detailed enough and the weight determination being biased to a single subjective or objective method in the existing research, this paper constructs a multi-criteria site selection evaluation method for an artificial underground CAES chamber in hard shallowly buried rock. Firstly, starting from the four criteria layers of ground environment, construction convenience, regional geological characteristics, and basic geological characteristics, combined with literature research and expert investigation, an evaluation index system containing 13 indicators was established. Secondly, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and entropy weight method (EWM) were introduced, the combination of subjective weight and objective weight realized through game theory, and the comprehensive weight of each index obtained. Then, the VIKOR method was used to rank the four candidate sites—A, B, C, and D—and the results were compared with those of the weighted TOPSIS method and the weighted gray relational analysis method. The engineering example shows that site B has advantages in group utility value, individual regret value, and compromise index. It is judged the optimal scheme by the three methods, and the ranking is stable under different decision-making mechanism coefficients, which verifies the robustness and applicability of the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model. The results show that the proposed method can distinguish different site selection schemes more clearly, effectively and comprehensively reflect suitability under complex geological and engineering conditions, and provide quantitative decision support for engineering site selection of artificial underground CAES caverns.

1. Introduction

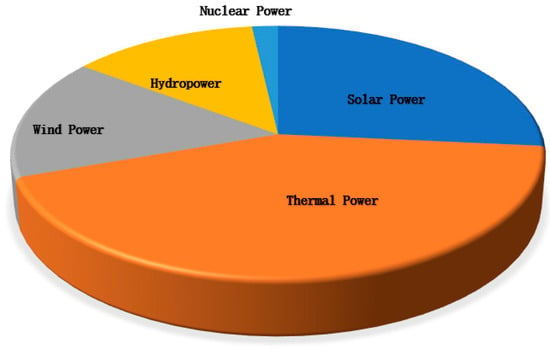

In 2024, China advanced significantly in transitioning to a green and low-carbon power sector. By the end of the year, the country’ s installed power capacity had reached 3.349 billion kilowatts, an increase of 14.6% compared to the previous year. Renewable energy keeps driving power capacity growth (Figure 1). New installations may exceed 400 million kilowatts, but wind and solar are intermittent. Because of this, the grid cannot take all their power, so some wind, solar, and hydropower are curtailed. Compressed air energy storage (CAES) [1,2,3] stores extra electricity as compressed air. It helps match supply and demand and improves power quality. It is efficient, compact, flexible, and cost-effective [4]. Artificial underground caverns can ease gas storage siting limits. They are promising for large-scale CAES [5]. Such caverns are often shallow. They run at high pressure and in changing temperatures. The rock must have high strength and good integrity. Feasibility depends on local geology [6,7]. Therefore, choosing the right site is critical for a CAES project.

Figure 1.

Composition of China’s power generation capacity in 2024 (National Energy Administration).

Choosing the site is the key step when building a gas storage facility. A good choice keeps the plant safe and efficient. It sets the construction plan and the schedule. It also affects how we use people, money, and equipment. It further affects residents’ livelihoods, regional economic benefits, and the ecological environment along access routes. Therefore, establishing a scientifically sound and rational evaluation system for artificial CAES cavern site selection and optimizing the chosen site is important for constructing artificial caverns. Existing research findings have significantly advanced the study of site selection optimization for artificial CAES caverns. Carranza-Torres et al. [8] investigated shallowly buried circular cavities’ geotechnical stability using analytical solutions and finite difference methods. Jin et al. [9] summarized the key technical points for constructing underground gas storage facilities for CAES power plants in hard rock regions, proposed overarching principles for determining site selection, and attempted to establish a comprehensive site evaluation system using the analytic hierarchy process. Jiang et al. [10] analyzed the distribution and characteristics of formations suitable for constructing hard rock underground gas storage facilities in China. Using Guangdong Province as a case study, they explored approaches and methodologies for planning and selecting sites for large-scale underground CAES power plant gas storage facilities. Carneiro et al. [11,12] combined GIS with multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) to assess geological reservoirs in Portugal and identify priority zones. Zhou et al. [13] systematically analyzed factors affecting artificial CAES cavern site selection. They built a full evaluation index system based on factor relationships. Wan et al. [14] used numerical simulation to study groundwater’s effect on cavern stability, aiding site selection and design. Rao et al. [15] summarized site selection principles and design methods for CAES caverns using experience from energy storage and hydraulic tunnels. Xia et al. [16] applied Abaqus software to study rock mass plastic zones, supporting research on seal material durability. Wang et al. [17] used a combined model to analyze energy loss and stress in hard rock CAES systems. In terms of multi-criteria decision-making methods, Gao et al. [18] proposed an evaluation method based on probabilistic linguistic terms and regret theory, and verified that the method had good applicability in dealing with expert fuzzy judgment and decision risk through actual cases, but its research focused on the evaluation method itself. Descriptions of engineering attributes such as geological structure, excavation conditions, and integrity of surrounding rock are relatively simple and lack deep integration with field investigation and rock mechanics analysis. Matos et al. [19] compared CAES with underground pumped storage (UPHS) and other underground energy storage technologies at a macro-system level, formulated screening criteria for different types of underground reservoirs, and focused on analyzing the matching relationship between different energy storage technologies and storage site conditions. However, this kind of research mainly focuses on the selection of technical routes. The site selection index focuses on macroscopic factors such as capacity, structure, and hydrogeology, and factors such as the stress environment, structural safety, and construction feasibility of artificial caverns are less involved. The current research generally focused on qualitative discussion and qualitative evaluation based on a single MCDM method, and the systematic quantification of multi-field coupling, geological uncertainty, and engineering constraints was still insufficient. In the determination of weights, most research mainly relies on experts in different fields to assign weights based on experience, which is easily affected by subjective judgment, or simply uses objective methods such as entropy weight, which only emphasize the data itself, ignore the importance of indicators, and lack the comprehensive representation of subjective and objective weights. The evaluation system for artificial caving in hard shallowly buried rock is still not perfect. The existing system is mostly oriented toward natural reservoirs or deep caving and lacks a targeted index design and comprehensive evaluation framework for the integrity of surrounding rock, the distribution of structural fracture zones, the risk of groundwater inundation, and construction organization, operation, and maintenance under shallowly buried conditions. In this paper, a comprehensive weighting method combining AHP and EWM is proposed, and the VIKOR method is introduced to optimize the ranking of multiple engineering candidate sites. Based on the application of MCDM, this method further improves the index system, the weighted fusion of objectives, and the engineering applicability for artificial chambers in hard shallowly buried rock, which provides a more scientific basis for the site selection of artificial CAES chambers.

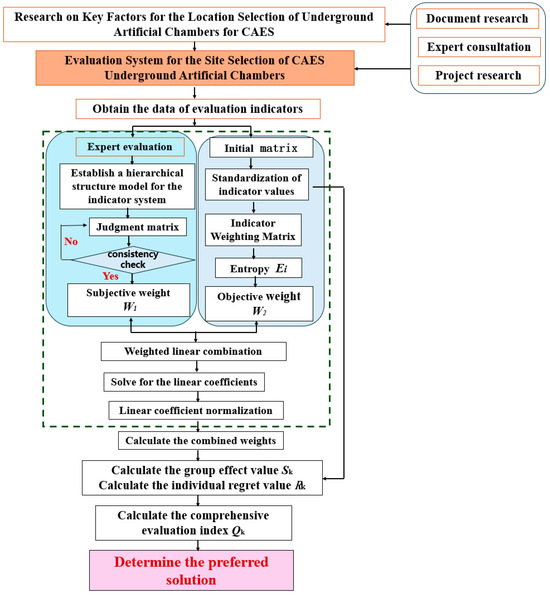

Site evaluation measures the suitability and safety of artificial cavern locations for CAES power plants. Using scientific evaluation methods, different site options can be effectively compared. This offers reliable support for final site selection decisions. The site evaluation process used in this study is as follows. Section 2 identifies key factors for preliminary cavern selection. This is achieved through literature review and tunnel engineering cases. Evaluation indicators and criterion layers are established using surveys. Section 3 builds a hierarchical evaluation system. It combines hydrogeological reports and opinions from industry experts. Using the AHP–EWM weighting analysis method, the comprehensive weights for each evaluation indicator are calculated. Section 4 employs the VIKOR method to optimize multiple alternative site design schemes. Section 5 presents the conclusions of this paper.

2. Evaluation Index System for Site Selection of Underground Artificial Caverns for CAES

2.1. Key Factors in Site Selection for Underground Cavern Storage of CAES

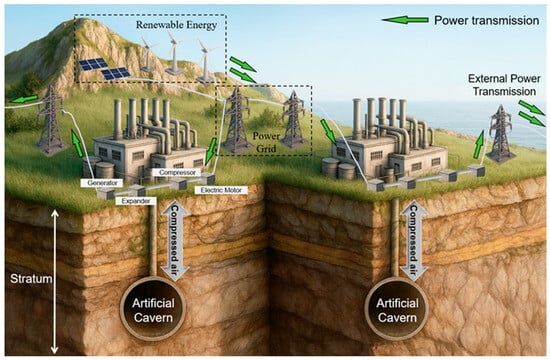

Artificial cavern structures (Figure 2) place stringent demands on the bearing capacity of the surrounding rock, long-term airtightness, geological stability, and the construction environment. Careful site selection is, therefore, a fundamental prerequisite for successful projects [1]. At the early stage of gas storage site planning, it is necessary to systematically identify and classify the main controlling factors on the basis of engineering geology. Their hierarchical influence on structural safety and construction feasibility should then be analyzed to support reliable engineering decisions.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the main components of a compressed air energy storage power station.

Geological factors influence the suitability of CAES underground storage reservoirs across three dimensions: structure, sealing, and construction [2], and exert combined effects through multiple pathways. The lithology, integrity, joint and fracture development, and rock mass classification of the surrounding rock are critical factors determining whether it possesses sufficient bearing capacity, deformation resistance, and long-term stability under prolonged high-pressure cyclic loading [3].

In storage systems with cooperative sealing, reservoirs usually have a composite structure. The system has three parts: a steel liner, a secondary liner, and the rock mass. The rock must be stable and uniform so it can hold the seals. If the surrounding rock has karst, faults, or water-rich zones, problems may appear. These features can focus deformation and cause uneven stress on the liners. They can also create leak paths when water and gas act together during operation [9]. Therefore, geology, groundwater, karst, and faults are critical because they control how well the storage stays sealed.

Rock type and structural features also guide the selection of excavation methods, support schemes, and overall construction plans. Weak layers or water-bearing zones often require specialized techniques and additional reinforcement, which increases construction difficulty and cost. Burial depth and surface topography further influence drainage and ventilation design and, thus, affect the construction schedule. Because these factors interact rather than act in isolation, judging the site based on a single indicator is unreliable. A transparent, multi-level evaluation framework is needed.

2.2. Formulation of the Comprehensive Indicator System

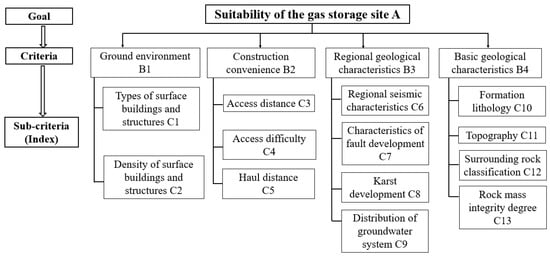

A structured evaluation system is needed to choose CAES cavern sites. If too few indicators are used, key information is lost and the evaluation becomes unreliable. If too many are included, indicators become redundant and the analysis grows unnecessarily complex. Indicator selection should, therefore, follow clear, systematic, and independence-oriented criteria. At present, there is no unified international safety design standard for CAES caverns [20]. Based on key factor studies and the hydraulic tunnel design literature, 13 evaluation factors were identified. In addition, a rating scale was developed. A total of 50 questionnaires were distributed and 45 valid responses were received. The respondents included 35 design experts in geology, structure, and energy storage, and 10 construction managers, all with extensive tunnel experience. The final evaluation system is constructed according to the hierarchical relationship and interaction relationship of the influencing factors, as shown in Figure 3. The details are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Evaluation index system for CAES artificial cavern storage site selection.

Table 1.

Illustration of the 13 evaluation factors.

- (1)

- Ground Environment (B1)

Surface structure density is an important indicator for CAES site selection. It affects safety, constructability, and public acceptance through its influence on accident consequences, construction coordination, permitting, ground-settlement risk, and system layout. If a site is near homes, factories, or roads and railways, work may face interference, vibration, and safety problems. Such sites also face stricter public pressure and tighter rules. In contrast, forested or undeveloped areas usually allow more planning and construction flexibility. Although not a highly technical factor, this indicator reflects important economic, logistical, and social–environmental impacts. It does not decide site selection alone, but helps rank options when technical conditions are similar. This supports the choice of an optimal site with practical management insights.

The type of surface structure is an important environmental and risk factor in selecting sites for CAES rock cavern storage. Even though the reservoir is located underground, its operation involves high-pressure air, thermal systems, and electrical equipment. In the event of leakage or explosion, the effects may propagate to the ground surface. Therefore, the nature, density, importance, and allowable disturbance level of surface structures directly affect the safety, social impact, and regulatory compliance of the site.

- (2)

- Construction Convenience (B2)

Construction accessibility has a direct impact on project duration and total investment. Access distance is a key technical and economic indicator in CAES cavern site selection. This index measures how far the site is from key infrastructure. It covers power lines, substations, gas pipelines, water sources, and main transport routes. Distance changes the upfront investment. It also changes operating efficiency, dispatch speed, and long-term maintenance cost. Sites located close to grid nodes, resource points, and transport hubs can reduce additional costs and losses from long-distance connections. They also enable faster grid integration, lower energy consumption in operation, and shorter construction periods.

Access difficulty is a core technical and economic factor for CAES rock caverns. It affects the schedule and the reliability of operation. This is because it controls how easily the site links to the grid and other resources, how feasible the build is, how clear the land rights are, and how strong the support is after handover. A good site has friendly terrain and sits near needed facilities. Land ownership is clear and the technical links are compatible. The connection plan should limit disruption, shorten build time, and keep coordination cost low.

Transport distance is an important practical factor for CAES caverns. It affects material cost, construction planning, environmental load, and operating efficiency over the whole life cycle [21]. Sites close to main transport corridors, suppliers, and support bases, with reliable road conditions and logistics services, can improve schedule control, reduce cost and risk, and enhance overall sustainability.

- (3)

- Regional Geological Characteristics (B3)

Seismic ground motion depends on amplitude, spectrum, duration, wavelength, and direction. Amplitude shows the energy released. More energy usually causes more damage. High-frequency content can trigger local spalling in rock and concrete. Long shaking raises the chance of plastic deformation and displacement. In severe cases it may cause low-cycle fatigue or collapse [24]. Seismic risk should be a key concern in site selection for artificial cavern gas storage. Sites should avoid areas with seismic intensity 8 or above. A seismic safety assessment is needed to secure overall safety at the regional scale [13].

Faults and joints in the surrounding rock control stability and failure [22]. Their orientation and spacing cause strength anisotropy in the rock mass. Long-term high pressure in storage caverns can change rock properties. Weak planes reduce bearing capacity and raise heterogeneity and discontinuity. Failure modes then become harder to predict and more complex. The risk of cavern hazards increases [25].

Karst development is another major site selection concern. In carbonate formations, sinkholes, karst valleys, and dissolution channels can disrupt rock continuity and form potential pathways for high-pressure gas leakage. This directly affects storage safety. Karst systems are often closely linked with groundwater. Gas–water interactions can weaken seals, corrode liners, and induce buoyancy-related problems, potentially leading to system failure. Sites with moderate or intense karst development require carefully designed sealing and isolation schemes; if the residual risk remains high, they should be excluded from consideration.

Groundwater conditions also strongly influence long-term sealing performance. Hydrogeological investigations should, therefore, identify aquifer distributions, recharge conditions, and water-level fluctuations. The design objective is to achieve groundwater conditions that are controllable and isolatable, thereby supporting robust sealing design and reliable operation.

- (4)

- Basic Geological Characteristics (B4) [1]

Rock lithology controls bearing capacity, excavation, and support design. Different rocks differ in strength, elasticity, durability, and pore structure. Engineering measures can reduce some risks, but rock properties still govern cost and safety.

Local topography also shapes project efficiency. It influences tunnel depth, cavern layout, and drainage scheme, and affects the thickness and stability of surface soils. These aspects in turn constrain the siting of temporary works and define the initial conditions for construction activities.

Rock mass classification shows mechanical behavior, integrity, and fracture development. It is the main basis for judging whether a stable cavern can form. Under high pressure, low-quality rock can cause lining cracks, instability, and leakage. In CAES projects, rock with poor integrity often deforms nonlinearly and develops microcracks under repeated loads. Over time the structure can degrade. Therefore, even if strength is high, weak integrity lowers long-term stability and sealing. Storage sites should be several hundred meters to several kilometers from major faults. In fracture-dense zones, detailed surveys and deformation monitoring are needed to confirm acceptable stress conditions.

The evaluation indicators are divided into two categories: qualitative and quantitative. The quantitative indexes include surface structure density, access distance and difficulty, transport distance, fault development degree, karst development degree, and rock grade and integrity (RQD value). Qualitative indicators include topography, landmark structure types, regional seismic characteristics, and groundwater distribution rules. According to previous research [19,26,27,28], the qualitative items were converted to quantitative data for analysis.

3. Comprehensive Evaluation of Site Selection Criteria for Underground Artificial Caverns in CAES Projects

3.1. Determination of Evaluation Indicator System Weights

3.1.1. Subjective Weighting in the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

The site selection of underground compressed air energy storage facilities is a complex evaluation system. The system includes multi-index and multi-level, covering geological, safety, construction, environment, and other factors. The relative importance of these factors varies across projects. A scientific and systematic method is, therefore, required to assign their weights in a reasonable way. In this study, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) [29] is adopted to derive subjective weights. AHP relies on expert judgment and incorporates internal consistency checks, and is, thus, widely applied in site selection, environmental assessment, and risk evaluation.

A questionnaire survey was conducted using the nine-point scale proposed by Saaty. Experts evaluated the relative importance of indicators within the criterion layer and the indicator layer. Based on the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), the importance weight values of criterion layer Bi relative to objective layer A and indicator layer Ci relative to criterion layer Bi were calculated separately, denoted as matrices I and II, for example, the weight of basic geological characteristics on site suitability and stratigraphic lithology on basic geological characteristics.

Before calculating weights, consistency verification of the matrix must be performed. First, matrices I and II undergo normalization processing. Subsequently, the maximum eigenvalue is computed. The consistency index C.I. is calculated based on the maximum eigenvalue and the matrix order n. Finally, the average random consistency index RI is introduced to calculate the test coefficient CR. When CR < 0.10, the test passes; otherwise, it fails. The comprehensive judgment matrix is adjusted based on empirical methods if the test fails.

After passing the consistency test, the matrix established the comprehensive sub-indicator weights for the objective layer.

3.1.2. Entropy Weighting Method (EWM) for Objective Weighting

The entropy weight method (EWM) assigns weights to indicators according to differences in the observed data, using entropy-based formulas, and has been widely used in many fields [4]. EWM reflects the utility value of sample information entropy without introducing subjective assumptions, yielding more objective indicator weights. The specific steps of EWM are as follows.

- (1)

- Data standardization. Standardize the data for each indicator. For m evaluation schemes and n evaluation indicators, first establish the raw matrix . Standardize the raw matrix to obtain the standardized matrix , where represents the standardized value of the j-th evaluation scheme on the i-th indicator—standardization formula for positive indicators (where higher values indicate better quality).

Standardization formula for negative indicators (where a smaller indicator value indicates better quality):

Here, represents the j-th indicator for the i-th sample, while and denote the maximum and minimum values of a given indicator across all samples, respectively. Standardization transforms all indicators into positive values, with the optimal value set to 1 and the worst value to 0.

- (2)

- Calculate the information entropy e of the indicators. The information entropy of the i-th indicator () is

- (3)

- Calculation of the difference coefficient: The difference coefficient for the i-th indicator is

- (4)

- Weight calculation: Determine the weight for the i-th indicator based on the coefficient of variation for each indicator.

Comprehensive weighting of sub-indicators for the overall objective layer:

3.1.3. Game-Theory-Based Combinatorial Weighting

While capable of reflecting subjective preferences, the subjective weighting method has limitations and may overlook actual data information. Objective weighting methods emphasize data objectivity but may overlook subjective intentions. A combined method is needed to avoid the weaknesses of using only a single approach, and a combined weighting scheme is adopted. This scheme integrates subjective and objective weights so that both expert judgment and data information are considered. Game theory [29] is used to find the best combined weights. It achieves this by combining the weights calculated from different methods. The goal is to reduce the difference between the final combined weight and the original weights. The specific steps are listed below.

- (1)

- Determine the weighting of each indicator.

If k methods are used to calculate the weights of each indicator, , their linear combination is expressed as

In the equation, denotes the linear combination of weights, represents the weight coefficient, and is the transpose matrix of the weight vector set .

- (2)

- Coefficient optimization. Based on game theory principles, the linear combination coefficients in Equation (10) are optimized to minimize the deviation of the linear combination , yielding the optimal . The corresponding optimal policy model is

- (3)

- Solve for the optimal combination. Based on the differential properties of matrices, the optimal first-order derivatives of Equation (11) can be converted into the following set of optimality conditions:

The coefficients obtained from Equation (12) are normalized as follows:

In this paper, the subjective weighting method employs AHP, while the objective weighting method utilizes EWM. The comprehensive evaluation method delivers holistic assessment outcomes by integrating subjective and objective weights. The combined weight vector derived from game theory is as follows:

3.2. Site Selection Optimization for Underground Artificial Caverns of CAES Based on the VIKOR Method

The VIKOR method [5] utilizes weights determined through AHP–EWM weighting to rank different CAES underground artificial cavern site options. The VIKOR measures the proximity of each scheme to the ideal and negative-ideal solutions for each indicator. It considers both the group utility value S and the individual regret value R. These are combined into a comprehensive compromise index Q, which is used to rank different CAES underground cavern site schemes. As conflicts may exist among CAES technologies, such as high investment in smart technologies reducing resource allocation flexibility, the VIKOR method helps balance multiple objectives to find optimal solutions. This provides a scientific basis for selecting the best CAES underground cavern site plan.

- (1)

- Determine the positive and negative ideal solutions. For each indicator, identify the positive perfect solution and the negative ideal solution . The perfect solution is typically the maximum or minimum value of the indicator after data normalization, depending on the optimization direction of the indicator. Calculate the distance between each solution and the ideal solution: Use the norm and norm to compute the weighted distance between each solution and both the perfect solution and the negative ideal solution.

norm calculation for group effect values:

norm calculation of individual regret value:

denotes the AHP–EWM weight for the j-th criterion.

- (2)

- Calculate the comprehensive evaluation index . By comprehensively considering and , compute the comprehensive evaluation index for each scheme using the following formula:

In the formula, and represent the minimum and maximum values of , respectively; and represent the minimum and maximum values of , respectively; denotes the decision-maker’s preference coefficient for group compromise versus individual optimality. Typically, balances the influence of overall proximity and individual proximity.

- (3)

- Determine the preferred option. Based on the calculated results for , , and , sort them in ascending order. Site options ranked higher are preferred. Assuming Sort Order 1 and Sort Order 2 represent the top two alternatives sorted by , Sort Order 1 is deemed the optimal solution if it simultaneously satisfies the following two conditions:

Condition 1: Acceptable benefit threshold condition. , where n denotes the number of alternative site options.

Condition 2: Acceptable decision reliability. The value (or value) corresponding to the value performs better than .

If only condition 1 is satisfied, the site plans ranked first and second are the optimal solutions. If only condition 2 is satisfied, the top k plans may all be considered optimal solutions. The maximum value of k is determined by .

Figure 4 illustrates the site selection evaluation process for artificial cavern storage facilities in compressed air energy storage power plants, based on game theory, AHP–EWM weighting, and the VIKOR method.

Figure 4.

Site selection evaluation process for underground artificial caverns in CAES.

4. Engineering Applications

4.1. Project Overview

A specific project has a capacity of 300 MW × 6 h, comprising one 300 MW-class compressed air energy storage generator unit and supporting facilities. The proposed underground cavern for gas storage has an operating pressure range of 6.6 to 12.6 MPa and a designed volume of 265,000 m3; cubic meters. Given the local geological and topographic conditions, an excavated underground storage cavern is proposed. After preliminary screening and field investigation, four candidate sites, Site A, Site B, Site C, and Site D, are under evaluation following preliminary screening and field surveys. These sites are summarized in Table 2, with site indicators detailed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Site conditions.

Table 3.

Site evaluation criteria.

4.2. AHP–EWM Weight Calculation

Based on the principles of the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine the relative importance of criteria in the criterion layer and indicators in the indicator layer of the CAES cavern site selection system [19]. These comparisons were performed using AHP, drawing on actual site parameters, engineering practice, and expert judgment to construct the pairwise comparison matrices. The weight vector for the criterion layer was then obtained using Equations (1)–(3):

Subjective weight:

EWM determines weights based on the fluctuation in evaluation metric data across different schemes. First, the raw data from the four site schemes are normalized using Equations (4) and (5), yielding the standardized data matrix R. Subsequently, the entropy value E of the evaluation metrics is calculated using Equation (6). Finally, the objective weight of the evaluation metrics is computed via Equation (8).

Based on the concept and methodology of composite weighting, and were substituted into Equations (10)–(14). Using MATLAB R2024a programming, the calculated values for α, β, and the composite weight W are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comprehensive weight calculation.

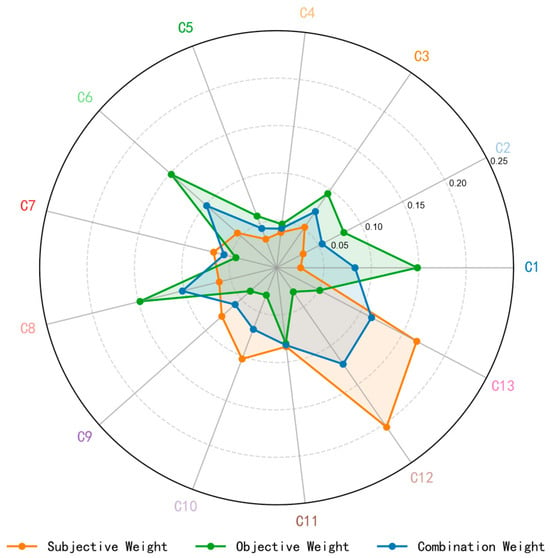

The weights for each evaluation indicator, calculated by three methods, are shown in Figure 5. These methods are the analytical method (AHP–EWM), the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), and the entropy weight method (EWM) [23]. As Figure 5 shows, the combined weights from the game theory approach fall between the weights from the AHP and EWM methods. The AHP method focuses on the inherent properties of the indicators. It also includes a significant amount of expert judgment. In contrast, the EWM method determines importance based on variations in the data. Because of these different emphases, the two methods can yield markedly different weights for the same indicator, and relying on only one method may lead to biased or unsatisfactory assessments. The game-theoretic combination approach addresses this issue by taking into account both the intrinsic attributes of each indicator and the structure of the data. As a result, the combined weights are more balanced and reasonable.

Figure 5.

Weighted radar chart.

4.3. Determination of the Optimal Solution

4.3.1. Calculate S, R, Q

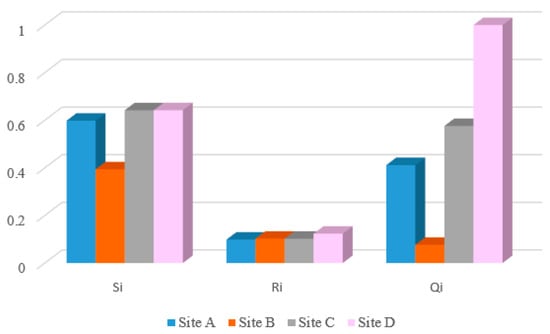

Based on the normalized matrix, the group effect value , individual regret value , and compromise decision index value for the four sites were calculated using the VIKOR evaluation model according to Equations (15), (16), and (17), respectively, based on the positive and negative ideal solutions for each indicator [30]. S, R, and Q were then sorted in ascending order, as shown in Table 5. Simultaneously, a comparison diagram (Figure 6) was plotted based on the group effect values , individual regret values , and compromise decision index values for the four sites, as shown in Figure 6.

Table 5.

Results of the VIKOR method for different sites.

Figure 6.

Comparison of calculation results for different sites.

Based on the evaluation criteria of the VIKOR method, the optimal solution was determined. It can be observed that Site B and Site A correspond to the access road schemes ranked first and second, respectively, with a compromise decision index value . Furthermore, Site B satisfies the acceptable benefit threshold requirement, i.e.,

Therefore, Condition 1 is satisfied. For Condition 2, Site B, which ranks first in Q value, also ranks first in both S and R values among all alternative sites, thus satisfying Condition 2. In summary, Site B can be determined as the optimal site for this CAES facility.

4.3.2. Robustness Evaluation

To validate the stability of the AHP–EWM–VIKOR method in mining plan optimization, the corresponding Q values were calculated by setting different decision mechanism coefficients to determine the ranking of mining plan preferences. Decision mechanism coefficients α were set to 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9 to study the ranking of alternative plans. The specific results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ranking of site options under different decision mechanism coefficients.

As shown in Table 5, with the continuous increase in decision mechanism coefficients, the Q values of the four alternative sites exhibit slight variations but remain generally stable. Site B consistently demonstrates superior performance across different decision mechanism coefficients, indicating that the decision mechanism coefficients have a relatively minor impact on the final evaluation results. The AHP–EWM–VIKOR model, therefore, exhibits good robustness in site selection optimization and provides a rational and reliable tool for identifying optimal underground CAES cavern sites.

4.4. Model Comparison Analysis

To further verify the rationality and advantages of the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model in CAES cavern siting, its results were compared with those obtained using the weighted TOPSIS method and the weighted gray relational analysis (GRA) method.

4.4.1. Comparison of Results Based on the Weighted TOPSIS Method

The weighted TOPSIS method establishes an initial decision matrix by obtaining indicator data for each alternative [31]. This initial matrix is then processed into a weighted, standardized decision matrix. Finally, by calculating the distance D between each evaluated alternative and the optimal alternative, as well as the distance D between each alternative and the worst alternative, the conformity index G between each evaluated alternative and the optimal alternative is obtained: the higher the conformity index, the better the evaluated alternative.

To enhance the comparability of calculation results, the standardization of the decision matrix and the selection of composite weights in the TOPSIS method calculation process were consistent with those of the weighted VIKOR model. The calculation results of the TOPSIS method are shown in Table 6. As indicated in Table 7, among the fitness values calculated by the weighted TOPSIS method, the order from highest to lowest is B, A, C, D. Therefore, B is the optimal solution.

Table 7.

Calculation results of the weighted TOPSIS method.

4.4.2. Comparison of Results Based on the Weighted Gray Relational Analysis (GRA) Method

The weighted GRA method constructs a reference (parent) sequence and comparative (feature) sequences from the evaluation indices. Both sequences are standardized, and the gray relational coefficients between the parent sequence and each feature sequence are computed using a discrimination coefficient of 0.5. The overall correlation degree of each scheme is then obtained by combining the gray relational coefficients with the indicator weights. The correlation degree measures the association between a given scheme and the reference sequence; a higher correlation indicates a better scheme. Using the weighted GRA method, the correlation degrees of Sites A, B, C, and D are 0.5606, 0.7236, 0.5407, and 0.5592, respectively, again indicating that Site B is the preferred alternative.

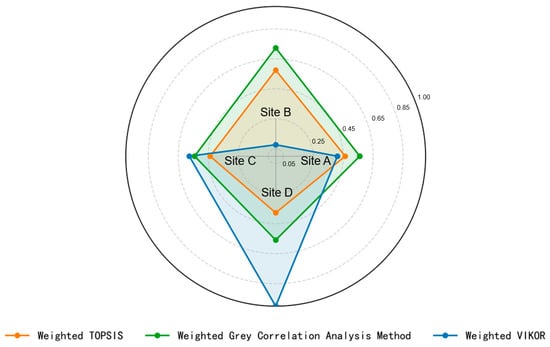

4.4.3. Comparative Analysis

All three models used in this study came to the same conclusion, choosing point B as the best choice. This result confirms the practicality of CAES cavern location model. A detailed comparison of the results of the three models is shown in Figure 7. Figure 7 shows that the optimal solutions obtained by the weighted TOPSIS model and the gray weighted association model are very close to the scores of the other options. This makes it difficult to clearly distinguish between different proposals. This means that these two models are less stable and easily affected by external factors or data errors. Small changes in the data may lead to different optimal solutions. In contrast, the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model combines group utility, individual regret, and compromise index. By comparing these values, it can clearly rank the options. This creates a larger score gap between the best solution and the other solutions. This makes the results more reliable and less sensitive to disturbances. Therefore, the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model provides a clearer and more robust ranking.

Figure 7.

Comparison of analysis results from different models.

Moreover, weighted TOPSIS and weighted GRA typically yield a single optimal scheme, and the differences in decision values between alternatives are often small. When many alternatives are present, this can limit the support for objective and transparent decisions. By contrast, the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model incorporates a decision-making coefficient enabling decision-makers to adopt more aggressive or conservative strategies according to project requirements. By explicitly analyzing trade-offs among attributes, the model can recommend compromise solutions rather than a single “winner”. This flexibility is particularly advantageous when dealing with multiple alternatives, as it provides more viable choices and can reduce the workload of decision-makers.

It should be noted that the selection and grouping of evaluation indicators for CAES cavern siting have a significant influence on the final results, yet there is currently no unified industry standard. Because many factors affect CAES location, further research is needed to refine the indicator system. Continuous optimization of the index framework will improve the accuracy and adaptability of the model and make the site evaluation process more scientific, reasonable, and comprehensive.

5. Conclusions

This study reviews the principal geological and engineering factors that influence underground CAES cavern siting and proposes a clear workflow that progresses from map-based screening to field investigations and detailed site assessment. Building on this foundation, a multi-level evaluation framework is developed to integrate regional tectonics, seismicity, faulting, karst conditions, and groundwater systems. The result is a science-based and practical approach for identifying suitable CAES cavern locations.

An evaluation system with a three-tier structure—objective, criterion, and indicator—is established according to the key factors affecting CAES cavern siting. The system incorporates 13 major indicators, including lithology, fracture spacing, groundwater conditions, karst development, rock-mass classification, and construction access. The role of each indicator in controlling project stability and safety is examined, providing a sound basis for the location model. Indicator weights are obtained using AHP and EWM and are then combined through a game-theoretic strategy to form the AHP–EWM–VIKOR model. This hybrid weighting approach enhances accuracy, avoids the limitations of any single weighting method, and improves the objectivity of the results. The proposed model satisfies engineering needs, accommodates complex geological constraints, and features good clarity, logic, and adaptability. Using this framework and the VIKOR method, four candidate sites were evaluated. For comparison, weighted TOPSIS and weighted gray relational analysis were also applied, and all three models identified the same optimal site.

The method integrates diverse sources of geological and engineering data and offers a structured way to compare multiple alternatives under numerous criteria. Compared with weighted TOPSIS and gray relational analysis, the new model provides clearer separation among alternatives and improves the reliability of the evaluation results. The case study demonstrates that the proposed approach is both robust and effective. It provides a valuable reference for CAES site optimization and offers quantitative support for decision making in practical engineering projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and Y.X.; methodology, B.C. and M.D.; software, B.C. and Y.X.; formal analysis, S.L. and M.D.; investigation, B.C.; resources, H.D.; data curation, Z.Z. and H.D.; writing—original draft, B.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z., Y.X., S.L. and M.D.; visualization, B.C., Z.Z., Y.X., H.D. and S.L.; supervision, M.D.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Minmetals Science and Technology Special Program’s Challenge and Response initiative (grant 2025ZXA04).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Bin Chen, Zhonghai Zhang, Yucheng Xiao and Hongyuan Ding were employed by the company WSGRI Engineering & Surveying Incorporation Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, K.; Sun, G.; Shi, L.; Lin, S.; Yu, X. A nonlinear damage constitutive model applicable to the surrounding rock of compressed air energy storage caverns. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 115048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.H.; Zhu, K.Y.; Ji, W.D.; Yi, Q.; Geng, X.; Yu, X. Basic concepts, design principles, and methods of compressed air energy storage underground caverns. Hazard Control. Tunn. Undergr. Eng. 2024, 6, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Yi, Q.; Yao, Y.; Shang, H.; Ji, W. Study on the potential instability patterns of tunnel type underground caverns for compressed air energy storage. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2024, 43, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, I.; Cañizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K. Compressed Air Energy Storage System Modelling for Power System Studies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3359–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Rutqvist, J.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, B.H.; Ryu, D.W.; Song, W.K. Characterizing Excavation Damaged Zone and Stability of Pressurized Lined Rock Caverns for Underground Compressed Air Energy Storage. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 46, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H.; Wang, T.T. Advance in deep underground energy storage. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2022, 41, 1729–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Shang, H.L.; Ji, W.D.; Xing, T.G.; Hu, W.; Mou, J.R. The Key Process of Artificial Chamber Location of Compressed Air Energy Storage Power Station. Electr. Power Surv. Des. 2023, 6, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Torres, C.; Fosnacht, D.; Hudak, G. Geomechanical analysis of the stability conditions of shallow cavities for Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) applications. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2017, 3, 131–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.P.; Peng, Y.C. Underground Gas Storage Cavern Location Method for Compressed Air Energy Storage Engineering in Hard Rock Area. Power Energy 2017, 38, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.M.; Tang, D.; Li, P.; Li, Y. Research on Selection Method for the Types and Sites of Underground Repository for Compressed Air Storage. South. Energy Constr. 2019, 6, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.F.; Matos, C.R.; van Gessel, S. Opportunities for large-scale energy storage in geological formations in mainland Portugal. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 99, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, C.R.; Carneiro, J.F.; Pereira da Silva, P.; Henriques, C.O. A GIS-MCDA Approach Addressing Economic-Social-Environmental Concerns for Selecting the Most Suitable Compressed Air Energy Storage Reservoirs. Energies 2021, 14, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.S.; Sun, G.B.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, W.; Huang, K.K. Study on Factors Affecting Site Selection for Artificial Cavern CAES Energy Storage. Electr. Power Surv. Des. 2024, 9, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Jiang, Z.; Liao, J.; Li, H. Influences of groundwater on air tightness and surrounding rock stability ofCAES underground gas reservoir. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, H.; Wang, R. Site Selection and Main Design Principles of Artificial Chamber Gas Storage in Compressed Air Energy Storage Power Station. Electr. Power Surv. Des. 2024, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.C.; Xu, Y.J.; Wang, C.L.; Zhao, H.O.; Xue, X.D. Calculation of air leakage rate in lined cavern for compressed air energy storagebased on unsteady seepage process. Rock Soil Mech. 2021, 42, 1765–1773, 1793. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Zhuang, X.Y. Numerical Simulation and Analytical Solutionof Hydraulic Fracturing in Sedimentary Rock Tunnels. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2018, 55, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Men, H.; Guo, F.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Huang, X. A multi-criteria decision-making framework for compressed air energy storage power site selection based on the probabilistic language term sets and regret theory. J. Energy Storage 2021, 37, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, C.R.; Carneiro, J.F.; Silva, P.P. Overview of Large-Scale Underground Energy Storage Technologies for Integration of Renewable Energies and Criteria for Reservoir Identification. J. Energy Storage 2019, 21, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.M.; Liu, Y.T.; Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Liao, J.H.; Liu, C.Z.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhou, W.F.; Shi, Z.F.; Tian, X.; et al. Review on key scientific and designissues of lined rock caverns for compressed air energy storage. Rock Soil Mech. 2024, 45, 3491–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkin, M.; Noorollahi, Y.; Abbaspour, M.; Yousefi, H. Multi criteria site selection model for wind-compressed air energy storage power plants in Iran. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.X.; Zheng, Z.X.; Hu, Y.J. Analysis of impact on the stability of high-geostress tunnels with layered rocks dips. J. Transp. Sci. Eng. 2014, 30, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamheden, R.; Curtis, P. Excavation of a cavern for high-pressure storage of natural gas. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2006, 21, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Judd, W.R. Underground opening damage from earthquakes. Eng. Geol. 1991, 30, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.E. Methods of Geological Engineering in Discontinuous Rocks; West Group: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Cong, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Long, Y. Research and application progress of abandoned mine compressed air energy storage. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, S.; Ma, H.; Mei, D.; Wei, Z.; Mei, C. Research status and development trend of compressed air energy storage in abandoned coal mines. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 163–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, R.W. The analytic hierarchy process—What it is and how it is used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opricovic, S.; Tzeng, G.H. Multicriteria Planning of Post-Earthquake Sustainable Reconstruction. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2002, 17, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, A.; Schlotter, R. Entropy based risk measures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 285, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Omar, M.; Etebaai, I.; Taher, M.; Tawfik, A. Landslide susceptibility mapping in the Bokoya Massif, Northern Morocco: A geospatial and multi-factor analysis using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Sci. Afr. 2025, 30, e02980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).