Abstract

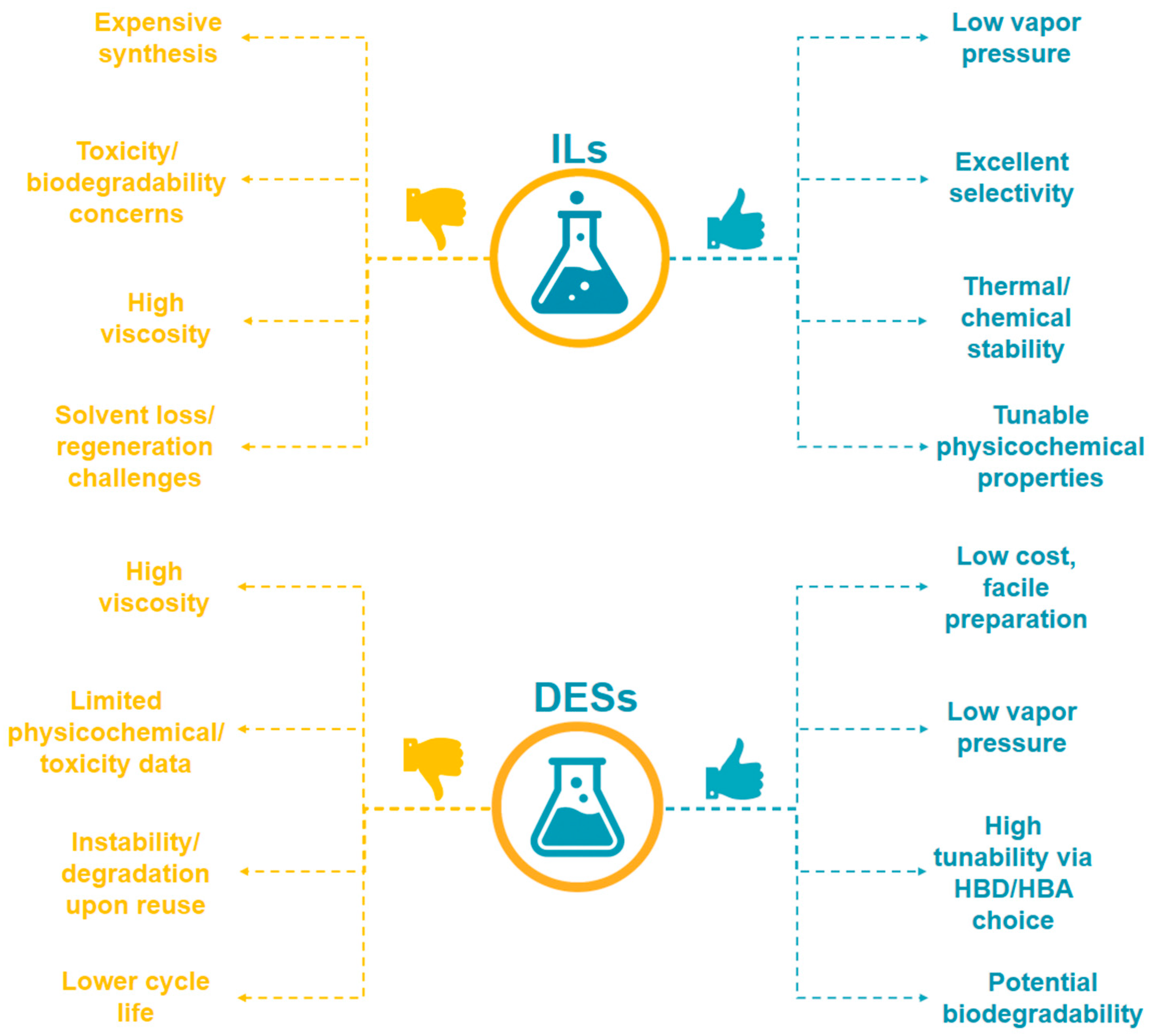

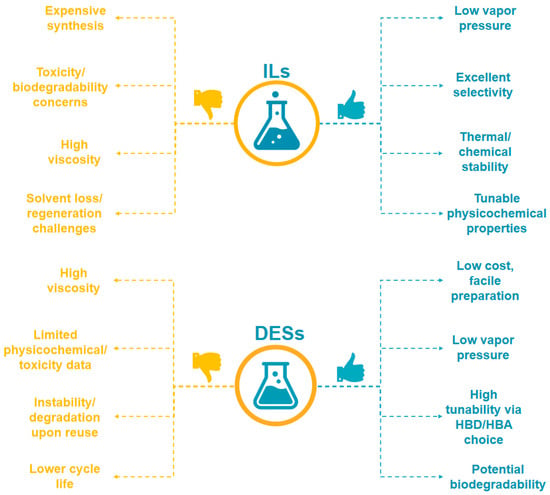

The escalating production and use of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have led to a pressing need for efficient and sustainable methods for recycling valuable metals such as cobalt, nickel, manganese, and lithium from spent cathode materials. Traditional hydrometallurgical leaching approaches, based on mineral acids, face significant limitations, including high reagent consumption, secondary pollution, and poor selectivity. In recent years, deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as innovative, environmentally benign alternatives, offering tunable physicochemical properties, enhanced metal selectivity, and potential for reagent recycling. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and prospects of leaching LIB cathode materials using DES and ILs. We summarize the structural diversity and composition of common LIB cathodes, highlighting their implications for leaching strategies. The mechanisms, efficiency, and selectivity of metal dissolution in various DES- and IL-based systems are critically discussed, drawing on recent advances in both laboratory and real-sample studies. Special attention is given to the unique extraction mechanisms facilitated by complexation, acid–base, and redox interactions in DES and ILs, as well as to the effects of key operational parameters. A comparative analysis of DES- and IL-based leaching is presented, with discussion of their advantages, challenges, and industrial potential. While DES offers low toxicity, biodegradability, and cost-effectiveness, it may suffer from limited solubility or viscosity issues. Conversely, ILs provide remarkable tunability and metal selectivity but are often hampered by higher costs, viscosity, and environmental concerns. Finally, the review identifies critical bottlenecks in upscaling DES and IL leaching technologies, including long-term solvent stability, metal recovery purity, and economic viability. We also highlight research priorities that emphasize applying circular hydrometallurgy and life-cycle assessment to improve the sustainability of battery recycling.

1. Introduction

In the context of the global shift toward decarbonization and sustainable energy systems, the rapid expansion of the global lithium-ion battery (LIB) market has emerged as one of the defining technological developments of the 21st century [1]. This growth is primarily driven by the accelerating transition toward electric vehicles (EVs), the large-scale integration of renewable energy storage systems, and the steadily rising demand for portable consumer electronics [2]. LIBs underpin a wide spectrum of modern technologies, ranging from consumer electronics and medical devices to electric vehicles and large-scale energy storage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main application areas of LIBs, including consumer electronics, electric vehicles, industrial vehicles, energy storage, medical devices, and tools & equipment.

Consequently, the consumption of critical battery raw materials, including lithium (Li), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn), has increased in recent years [3]. These elements are consistently listed among critical raw materials owing to their high economic importance and the elevated risk of supply disruption, as emphasized in both European Union (EU) and United States (U.S.) strategic assessments [4,5]. The geographical concentration of their primary resources, combined with volatile market prices and environmentally intensive mining practices, underscores the necessity for developing efficient, sustainable, and economically viable recycling strategies [6], which are increasingly viewed as an essential complement to primary mining.

From an environmental standpoint, the end-of-life (EoL) management of LIBs involves two major challenges: the safe disposal of hazardous components and the recovery of valuable metals [7]. Spent LIBs can release toxic electrolytes and heavy metals into the environment, creating serious risks for ecosystems and human health [8]. At the same time, these waste streams constitute an urban mine with high concentrations of strategic metals, with Co content often exceeding that of primary ores [9,10]. Therefore, the development of advanced recycling technologies is not only a matter of waste treatment but also a strategic approach to securing critical raw materials, lowering the environmental impact, and supporting a circular economy in the battery industry [11].

At the same time, the complex structure of LIBs—comprising electrodes, electrolytes, binders, and metallic collectors—adds layers of difficulty to downstream recycling processes [12]. Each component plays a distinct role in the overall performance of the cell, and its end-of-life management is crucial for both environmental protection and the recovery of resources [13]. The electrolyte, typically composed of lithium salts dissolved in organic carbonates, can release hazardous compounds if improperly handled [14]. At the same time, binders such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and conductive additives require removal to enable efficient downstream processing [15]. Metallic current collectors, commonly aluminum for the cathode and copper for the anode, represent secondary sources of these metals with significant recycling potential [16].

Among all components, the cathode is of particular importance due to its content of strategic and high-value transition metals [17]. Their targeted recovery not only secures the supply of critical resources but also significantly reduces the environmental footprint, thereby positioning cathode recycling at the heart of sustainable LIB value chains [18,19].

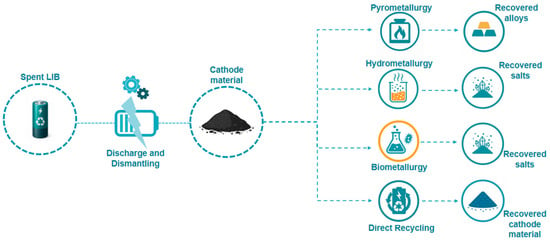

To recover these valuable elements, four main recycling routes are generally recognized: pyrometallurgy, hydrometallurgy, biometallurgy, and direct recycling (Figure 2). Pyrometallurgy, which relies on high-temperature smelting, is a robust and well-established technology capable of processing mixed and contaminated feedstocks [20,21]. However, despite its maturity, pyrometallurgy is highly energy-intensive, generates substantial greenhouse gas emissions, and frequently results in the loss of lithium in the slag phase [22,23]. Biometallurgy employs microorganisms to facilitate the dissolution of metals under mild conditions, offering environmental advantages and lower energy input. Nevertheless, its slow kinetics, high sensitivity to process parameters, and the difficulties associated with handling concentrated feedstocks currently restrict its industrial scalability [24,25]. Direct recycling seeks to recover and regenerate cathode materials in their functional form without decomposing them to elemental constituents, thereby preserving their structural and electrochemical properties [26]. Yet, the strong variability of spent batteries, complex disassembly procedures, and the absence of standardized protocols have so far prevented their wide industrial adoption [26,27].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the four main recycling routes for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs): pyrometallurgy, hydrometallurgy, biometallurgy, and direct recycling, along with their typical recovered products (alloys, salts/metals, and regenerated cathode materials).

In contrast to pyrometallurgical and direct recycling routes, hydrometallurgy has gained prominence as the preferred approach for LIB recycling because it combines operation at moderate temperatures with the potential for high recovery yields and selective metal separation [27,28,29]. Its adaptability in integrating leaching with downstream separation and purification steps makes it particularly suitable for recovering critical metals from diverse LIBs within a sustainable processing framework [29]. Within hydrometallurgical workflows, leaching is the main step that governs the overall efficiency, selectivity, and economic viability of the process [30]. Conventional leaching methods typically employ strong mineral acids, often in combination with reducing agents to accelerate dissolution [31]. Although these systems can achieve nearly complete dissolution of transition metals, their disadvantages include excessive reagent consumption, the generation of large volumes of acidic effluents, safety concerns, and considerable environmental impacts [23]. These drawbacks directly conflict with the Twelve Principles of Circular Hydrometallurgy, which emphasize minimizing the use of hazardous reagents, reducing chemical diversity, optimizing mass and energy efficiency, closing water loops, and enabling reagent regeneration and reuse [32].

In line with these principles, deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as promising alternative leaching agents. DES are formed by combining a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) with a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) at a defined molar ratio to produce a eutectic mixture with a melting point significantly lower than that of the individual components, and they can be synthesized from inexpensive, biodegradable, and often bio-based compounds [33]. ILs, in contrast, are salts composed entirely of cations and anions, whose structures can be precisely tuned to control properties such as polarity, coordination ability, and redox potential for specific leaching applications [34]. Both DES and ILs exhibit negligible vapor pressure, high thermal and chemical stability, and potential for multiple reuses, thereby aligning with the goals of green chemistry and providing a pathway to implement circular hydrometallurgy in the large-scale recovery of critical metals from LIBs.

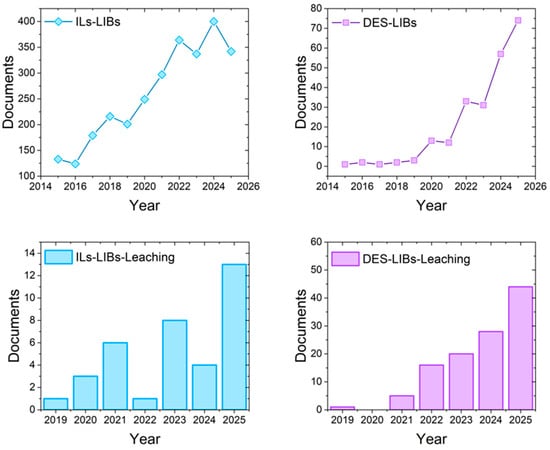

Bibliometric analyses confirm the growing scientific attention devoted to DES- and IL-based approaches in LIB recycling. As illustrated in Figure 3, IL-related research has consistently dominated the literature, reflecting its earlier development and broader application base. In contrast, DESs—although historically underrepresented—have shown an exponential rise in publications over the past five years, signaling their emerging relevance as sustainable solvents. When the scope is narrowed specifically to leaching-focused studies, distinct trends emerge: DESs display a sharp increase after 2021, reaching 44 papers by 2025, while ILs remain comparatively modest, with 13 papers in 2025. Together, these data reveal both the maturity of IL research and the rapid momentum of DESs in the critical step of metal leaching, underscoring the need for a comparative evaluation of their mechanisms, efficiencies, and industrial potential. The bibliometric database was compiled from Scopus, covering the last ten years for general recycling studies and the previous six years for leaching-related studies, corresponding to the appearance of the first publications in this field.

Figure 3.

Bibliometric analysis of publications indexed in Scopus (2015–2025) on the use of green solvents in LIB recycling: general trends for ionic liquids (ILs) and deep eutectic solvents (DESs); DES-related publications explicitly addressing leaching; IL-related publications explicitly addressing leaching.

To contextualize recent research activity and identify emerging thematic directions within solvent-assisted recycling of lithium-ion batteries, a bibliometric keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20). Separate datasets were compiled for DES-focused and IL-focused studies to examine whether these solvent families occupy overlapping or distinct conceptual spaces within the broader hydrometallurgical landscape.

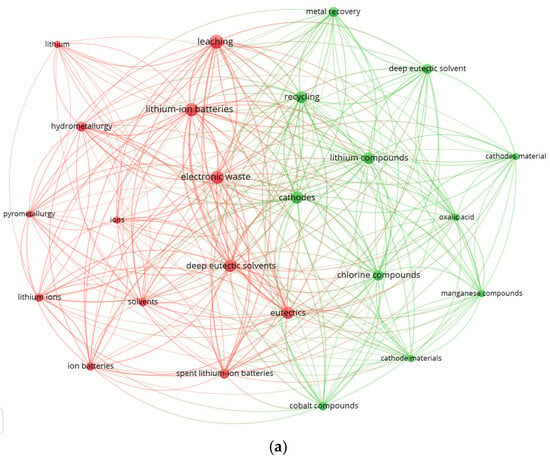

The VOSviewer map generated from 217 Scopus records (2019–2026) containing the terms “deep eutectic solvent”, “leaching”, and “lithium-ion battery” reveals two dominant thematic clusters (Figure 4a). The red cluster comprises “leaching”, “electronic waste”, “lithium-ion batteries”, “hydrometallurgy”, and “deep eutectic solvents”, highlighting a strong research focus on solvent-assisted metal extraction and the integration of DES into LIB recycling workflows. This cluster underscores the central role of DES in discussions related to selective metal dissolution, chloride-mediated coordination chemistry, and comparisons with conventional acid-based routes. In contrast, the green cluster groups terms such as “recycling”, “lithium compounds”, “cathode materials”, “oxalic acid”, and “metal recovery”, which represent established hydrometallurgical practices and benchmark leaching systems. The dense intercluster connectivity indicates that DES chemistry is increasingly embedded within mainstream hydrometallurgical research and is being positioned as a viable, potentially greener alternative to traditional mineral acids.

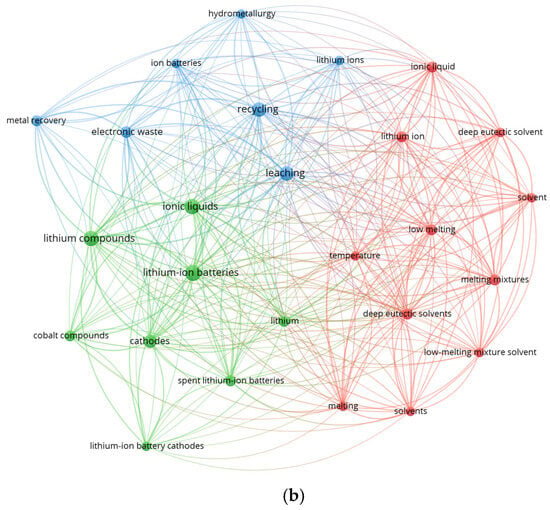

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence networks generated using VOSviewer. (a) Map based on 217 Scopus records (2019–2026) containing the terms “deep eutectic solvent”, “leaching”, and “lithium-ion battery.” Two dominant clusters are observed: a DES-centered cluster associated with hydrometallurgical leaching and electronic waste processing, and a classical hydrometallurgical cluster associated with lithium compounds, cathode materials, and conventional leaching agents. (b) Map based on 50 Scopus records (2019–2026) containing the terms “ionic liquid”, “leaching”, and “lithium-ion battery”. Three clusters emerge, linking IL solvent chemistry with metal dissolution from cathode materials and integration into hydrometallurgical recycling schemes.

In parallel, analysis of 49 Scopus-indexed publications (2019–2026) containing the terms “ionic liquid”, “leaching”, and “lithium-ion battery” reveals three distinct thematic clusters (Figure 4b). The blue cluster contains process-oriented concepts such as “hydrometallurgy”, “recycling”, and “metal recovery”, reflecting the incorporation of ionic liquids into established resource-recovery frameworks. The green cluster includes material-specific terms such as “lithium-ion batteries”, “lithium compounds”, “cobalt compounds”, and “cathodes”, which emphasizes the strong emphasis on selective dissolution of transition metals from cathode active materials. The red cluster is composed of solvent-related terms—including “ionic liquids”, “melting mixtures”, and “temperature”—indicating that IL research remains tightly linked to understanding solvent structure, viscosity, and thermal behavior. The numerous cross-cluster connections show that ionic liquids act as a conceptual bridge between solvent chemistry and applied hydrometallurgical processes, reinforcing their emerging role as tunable, non-volatile alternatives to conventional leaching agents.

Together, these bibliometric maps show that DES research has formed a distinct and rapidly expanding cluster centered on sustainable, chloride-assisted leaching, while IL research spans a broader conceptual space that links solvent design with selective metal dissolution and process engineering. The complementary cluster structures illustrate how both solvent families are shaping the evolving landscape of green hydrometallurgy.

Although several review articles have examined the use of green solvents in LIB recycling, most of them focus primarily on a single solvent class or offer only limited comparative insight into DES and IL systems [10,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Reviews centered on DES typically highlight their green chemistry attributes and efficiency in metal dissolution, whereas IL-focused reviews often address broader applications such as solvent extraction or electrolyte design, with little emphasis on cathode-specific leaching.

In contrast, the present review provides a direct and tightly integrated comparison of DES and IL systems specifically within the context of leaching LIB cathode materials. The discussion combines mechanistic interpretation (acid–base behavior, complexation, redox pathways, and kinetic regimes), systematic correlation of solvent properties with leaching performance (viscosity, acidity, coordination ability), cross-chemistry evaluation across major cathode types (LCO, NMC, and others), and critical consideration of solvent reuse, scalability, and operational limitations. Bibliometric trends and industrial prospects are also incorporated, establishing a broader process-oriented perspective. To our knowledge, no existing review offers such a dual-solvent, cathode-focused, and mechanistically grounded assessment.

Furthermore, several recent reviews published between 2023 and 2025 underscore the growing interest in DES- and IL-based technologies [10,35,39,45,46]. However, these studies typically evaluate only one solvent family, do not compare leaching efficiencies across different cathode chemistries, or overlook essential practical aspects such as solvent regeneration and industrial feasibility. By addressing these gaps, the present work provides a uniquely comprehensive and circularity-driven evaluation of DES and IL systems for LIB recycling.

2. Overview of LIB Cathode Materials

Cathode materials form the essential core of LIBs, determining their electrochemical behavior, energy density, operational safety, and service life [47,48]. They are typically based on layered or spinel-type lithium transition metal oxides, such as LiMO2 (where M = Co, Ni, Mn, or a combination of these metals) or LiMO4 (where M = Fe, Mn) [47]. In these structures, lithium ions can be reversibly inserted and removed during charging and discharging. The most common commercial types include lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2, LCO), lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (LiNixMnyCozO2, NMC), lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4, LFP), lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2, NCA), and lithium manganese oxide (LiMn2O4, LMO) [49]. Each of these materials combines specific advantages and drawbacks that define its applications: LCO offers high energy density and stable cycling, making it dominant in portable electronics [50]; NMC, with adjustable Ni:Mn:Co ratios, is the leading choice for electric vehicles due to its balance of performance and cost [51]; LFP stands out for safety, thermal stability, and long cycle life, but with a lower voltage [52]; NCA delivers a very high capacity but demands stringent synthesis and handling control due to its high nickel content [53], and LMO is cost-efficient with high rate capability, but its use is limited by manganese dissolution and capacity loss at elevated temperatures [54].

Table 1 summarizes the main properties of widely used LIB cathode materials, highlighting their crystal structure, electrochemical performance, cost, and safety profile. This comparative overview allows a direct assessment of each material’s strengths and limitations, as well as its primary application sectors. The data clearly illustrate how material choice influences parameters such as energy density, cycle life, and thermal stability, which in turn determine the suitability of a cathode for portable electronics, electric vehicles, or stationary energy storage.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of common lithium-ion battery cathode types and their market relevance [35].

3. Preparation of Cathode Materials for Leaching

Efficient metal leaching from spent LIBs requires prior separation of the active cathode material from other cell components and its careful preparation. The recycling process typically begins with sorting, discharging, and dismantling of cells, modules, and packs [9,55]. A major challenge at this stage is the wide diversity of cell formats—prismatic, cylindrical, and pouch cells—that are tightly sealed and assembled with different adhesives. Active electrode materials are bound to aluminum or copper current collectors using polymeric binders such as poly (vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF), poly (acrylic acid) (PAA), or poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA), which are chemically stable and highly resistant to elevated temperatures [55].

Discharging is generally performed by immersing high-voltage cells in a concentrated saline solution to eliminate residual charge and minimize the risk of short circuits, combustion, or toxic gas emissions [56]. Once discharged, the cells are subjected to mechanical size reduction by either wet or dry crushing. Wet crushing provides a cooled, oxygen-free environment, but generates wastewater and may cause excessive fragmentation of metal foils. In contrast, dry crushing produces cleaner fractions with fewer impurities [57].

Following crushing, physical separation techniques such as sieving, magnetic separation, and density-based classification are applied to divide the fragmented material into distinct fractions [58]. At this point, additional pretreatment methods may be used to detach active material from the current collectors. These include ultrasonic irradiation, microwave heating, solvent-based delamination, and thermal treatments, selected according to efficiency, cost, and environmental considerations [59]. Mechanical processing methods such as milling or fine sieving may also be applied to disrupt particle agglomerates and weaken crystal structures, thereby facilitating subsequent leaching [10].

A critical step in pretreatment is binder removal, as polymeric binders strongly adhere active particles to collector foils and hinder solvent penetration during leaching. High-temperature pyrolysis effectively decomposes binders but is energy-intensive and releases hazardous gases. As an alternative, solvent-based approaches ranging from organic solvents to more sustainable options such as ionic liquids can dissolve PVDF and related polymers at lower temperatures with reduced environmental impact [60]. Mechanical separation techniques, including grinding, electrostatic or pneumatic separation, flotation, and spouted bed elutriation, have also been applied to remove binders and conductive carbon. In some cases, high-power ultrasound or vibrating screens are employed for rapid delamination of active material from foil substrates [60,61].

Through these combined steps, the cathode material is cleaned, concentrated, and exposed to the leaching agents, ensuring that the subsequent leaching stage proceeds with higher efficiency, reduced reagent consumption, and minimal contamination of the leachate.

4. Traditional Approaches to Leaching and Their Limitations

The recovery of valuable metals from LIB cathode materials has historically relied on conventional leaching techniques using mineral acids, alkaline solutions, ammonia-based systems, and, more recently, bio-acids [62]. Mineral acids such as sulfuric (H2SO4) [63,64], hydrochloric (HCl) [65,66], and nitric (HNO3) [67,68] are the most widely employed, often combined with reducing agents such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or ascorbic acid to accelerate dissolution and facilitate the reduction of transition metals to more soluble oxidation states. Among these, sulfuric acid in combination with H2O2 has become a de facto industrial benchmark for the leaching of layered LCO and NMC cathode materials [30,63]. In such systems, protons attack the M–O lattice framework while the reducing agent converts Co(III) to Co(II) and Mn(IV) to Mn(II), thereby overcoming thermodynamic barriers and achieving high dissolution yields [69]. Hydrochloric acid, due to the strong complexation ability of chloride ions, dissolves Ni and Co efficiently but raises significant corrosion issues [70], while nitric acid offers strong oxidative power yet produces NOx gases and generates nitrate-rich effluents that require costly treatment [71]. For LFP cathode material, the stability of the FePO4 framework necessitates stronger acidic environments and/or oxidative assistance to break P–O bonds, with H2SO4/H2O2 systems commonly used despite higher acid consumption and phosphate-related precipitation challenges [72,73]. In the case of LMO cathode materials, dissolution depends on reducing Mn(III/IV) to Mn(II), where careful control of redox potential and pH is critical to avoid secondary precipitation and manganese losses [74].

Alkaline and ammonia-based leaching systems are generally used as pre-treatment or selective extraction steps rather than as the main leaching stage. Alkaline leaching, typically using NaOH, can selectively dissolve aluminum from current collectors and aluminum oxide phases. This pretreatment step effectively reduces downstream acid consumption and enhances mass transfer during subsequent leaching cycles, while leaving nickel, cobalt, and manganese largely insoluble [75,76]. Ammonia and ammonium salt solutions, capable of forming stable ammine complexes with Ni and Co, enable selective solubilization of these metals, although complex stability is highly dependent on pH, ligand concentration, and the presence of competing ions. Such systems are more commonly integrated into multi-step flowsheets for targeted separations than applied as standalone processes [77,78].

Organic bio-acids such as citric, oxalic, malic, succinic, lactic, and ascorbic acid have gained attention as milder and more environmentally benign alternatives. These acids dissolve metals through a combination of proton-mediated lattice attack and complexation, with some (e.g., ascorbic acid) also serving as mild reducing agents [79]. An attractive feature of certain bio-acid systems is the possibility of in situ precipitation of metals during leaching—for example, cobalt can be recovered as insoluble cobalt oxalate—thus integrating dissolution and separation in a single step [80]. However, bio-acid leaching often suffers from slower kinetics than mineral acids, requiring higher temperatures, longer contact times, and larger reagent dosages, which can limit their economic feasibility at industrial scale.

At the mechanistic level, conventional leaching proceeds through proton attack on the oxide lattice, leading to the cleavage of M–O bonds, redox transformations of transition metals into soluble states, and subsequent complexation that stabilizes the dissolved ions in solution. For LCO and NMC cathode materials, the dissolution process critically hinges on reducing Co(III) (and to a lesser extent Mn(IV)) to their more soluble divalent forms, Co(II) and Mn(II). This redox conversion significantly lowers kinetic barriers—hence, leaching systems often incorporate reductants such as hydrogen peroxide, glucose, or sodium bisulfite to enhance efficiency [81]. In LFP systems, simple protonation and complexation are insufficient due to the robust FePO4 lattice. Therefore, oxidative assistance, commonly in the form of H2O2 or persulfate additives, is required to facilitate P–O bond cleavage and enable Fe dissolution [82]. However, this approach often leads to phosphate release and may cause secondary precipitation, complicating downstream processing.

In all cases, process parameters like acid concentration, solid-to-liquid ratio, temperature, leaching time, and mixing intensity govern the transition from chemically controlled to diffusion-controlled regimes, often described by the shrinking-core model [81,83,84]. Surface passivation by precipitated iron/phosphate phases or gelatinous layers can further slow reaction rates if not properly managed.

While conventional acid-based leaching can achieve high efficiencies (>90–95% under optimized conditions), their long-term sustainability is limited by technical, environmental, and economic drawbacks [85]. High reagent consumption arises from reactions with inactive phases and current collector metals (Al, Cu), while neutralization of acidic effluents generates gypsum and metal-bearing sludge, raising costs and regulatory concerns. Specific drawbacks include corrosion risks in chloride systems, NOx emissions and nitrate-rich effluents in nitric acid systems, and safety issues with hydrochloric acid. Residual LiPF6 can form HF upon contact with acids, adding further HSE hazards. These aqueous systems also entail high water use and significant energy input.

Bio-acids offer lower toxicity and environmental impact but suffer from slower kinetics, higher reagent demand, and variability in performance. To be viable, they often require integration with in situ precipitation or membrane-based separation. Ammonia-based systems add further costs and regulatory complexity due to volatilization, emission control, and reagent losses.

Altogether, despite their proven high dissolution efficiency, conventional leaching methods are increasingly examined under the lens of circular hydrometallurgy [32] and green chemistry [86]. Deep eutectic solvents and ionic liquids have thus emerged as promising candidates for the next generation of LIB leaching processes, offering opportunities for more finely tuned dissolution chemistry, improved integration with downstream separation, and easier solvent regeneration.

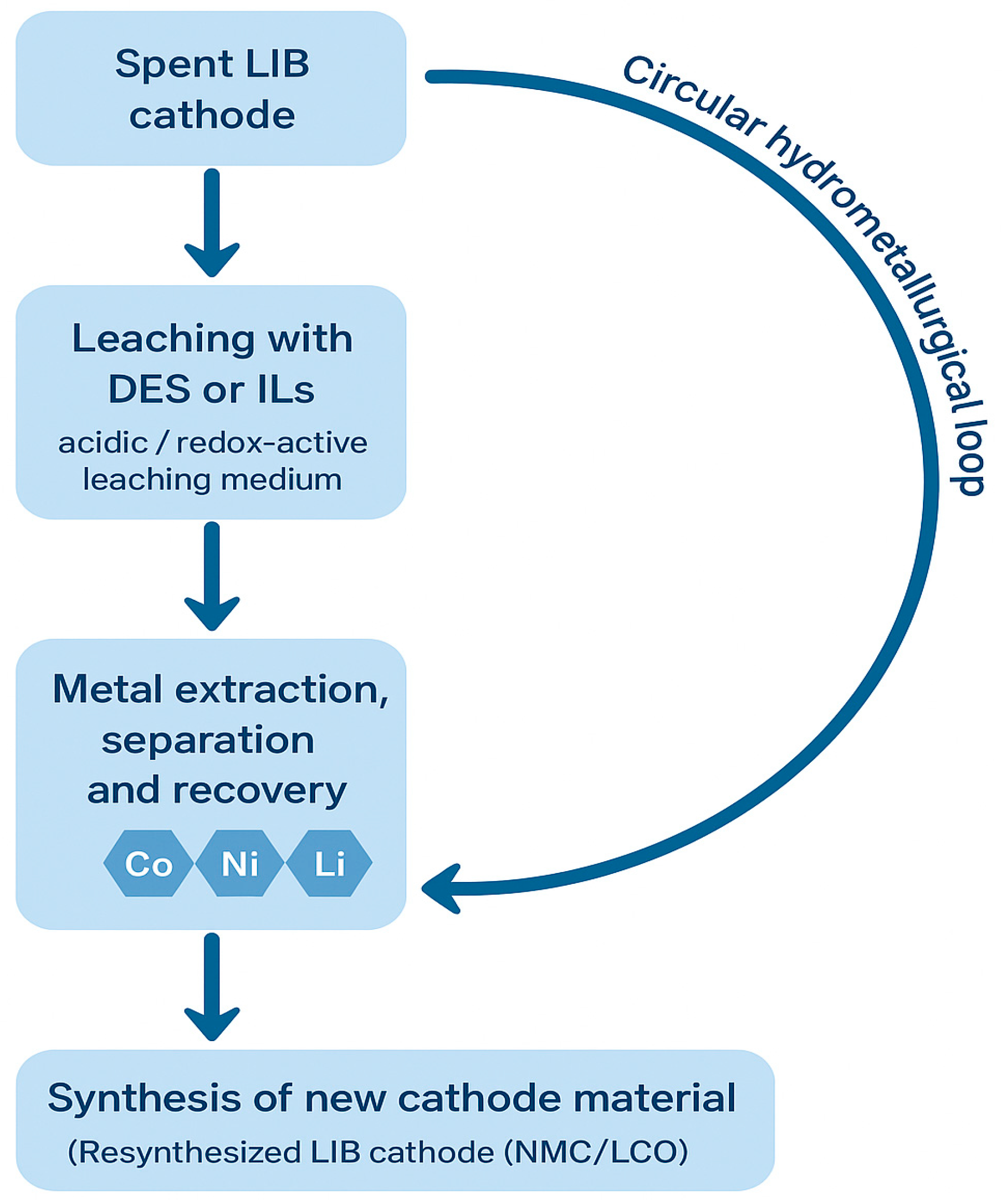

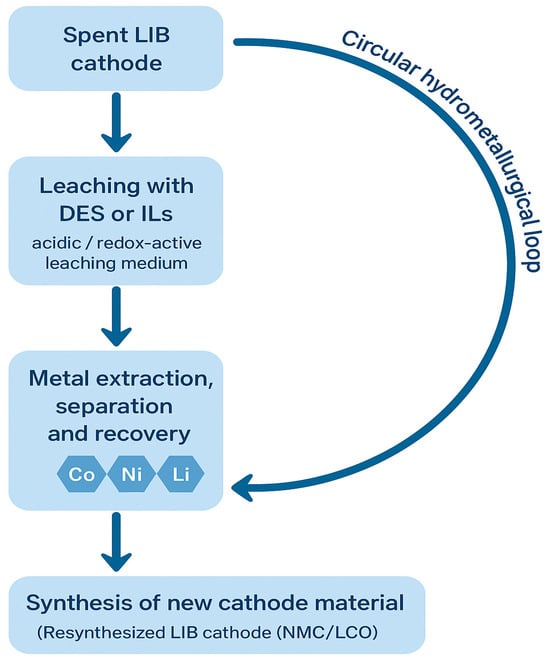

To contextualize the role of DES and IL systems within the broader recycling landscape, a simplified process schematic is presented in Figure 5. In this work, the term “circular hydrometallurgy” refers to hydrometallurgical processes explicitly designed to operate within a circular-economy framework, where reagents, solvents, and recovered metals are continuously regenerated, reused, or reintegrated into new production cycles. Circular hydrometallurgy emphasizes closed-loop solvent management, minimized waste generation, and the reinsertion of high-purity recovered metals into battery manufacturing, thereby reducing primary resource extraction and overall environmental impact. The diagram outlines the key stages of a circular hydrometallurgical route for processing spent LIB cathodes, beginning with solvent-mediated leaching (DES or IL), followed by metal extraction, separation, and recovery, and ultimately reintegration of recovered elements into new cathode synthesis. By visually connecting these steps into a closed-loop framework, the schematic reinforces the conceptual basis for the subsequent sections, where the mechanistic, operational, and practical aspects of DES- and IL-based leaching are examined in detail.

Figure 5.

Simplified circular hydrometallurgical flowsheet for the recovery of metals from spent LIB cathodes.

5. Ionic Liquids: Structure, Properties, and Overview of Leaching of LIB Cathodes

In line with the principles of circular hydrometallurgy [32], the development of sustainable leaching strategies emphasizes not only high metal recovery but also reagent regeneration, controlled chemical consumption, and minimization of secondary waste streams. Designing such closed-loop processes requires the integration of selective and reusable chemical systems that can operate under mild conditions while preserving the chemical integrity of the reagents. Traditional mineral acids and bases, though effective, are typically consumed in large amounts and generate significant waste. In contrast, the application of ILs as alternative leaching media offers several advantages. These low-volatility, thermally stable solvents can dissolve a wide range of metal-containing materials, including spent LIB cathode materials, under relatively mild conditions and with high selectivity. Moreover, ILs can be rationally designed through cation–anion tuning (“task-specific design”) to control their coordination behavior, polarity, redox properties, and affinity for specific metal ions, thereby enhancing dissolution performance. Their potential for regeneration and reuse makes them highly attractive for integration into environmentally responsible and economically viable flowsheets.

Although the fundamental behavior of ILs, ion pairing, Lewis acidity/basicity, specific coordination to M–O bonds, and viscosity-limited mass transfer has been extensively discussed in prior literature, only a concise overview is provided here to avoid redundancy and leave room for emerging IL systems with enhanced functionalities.

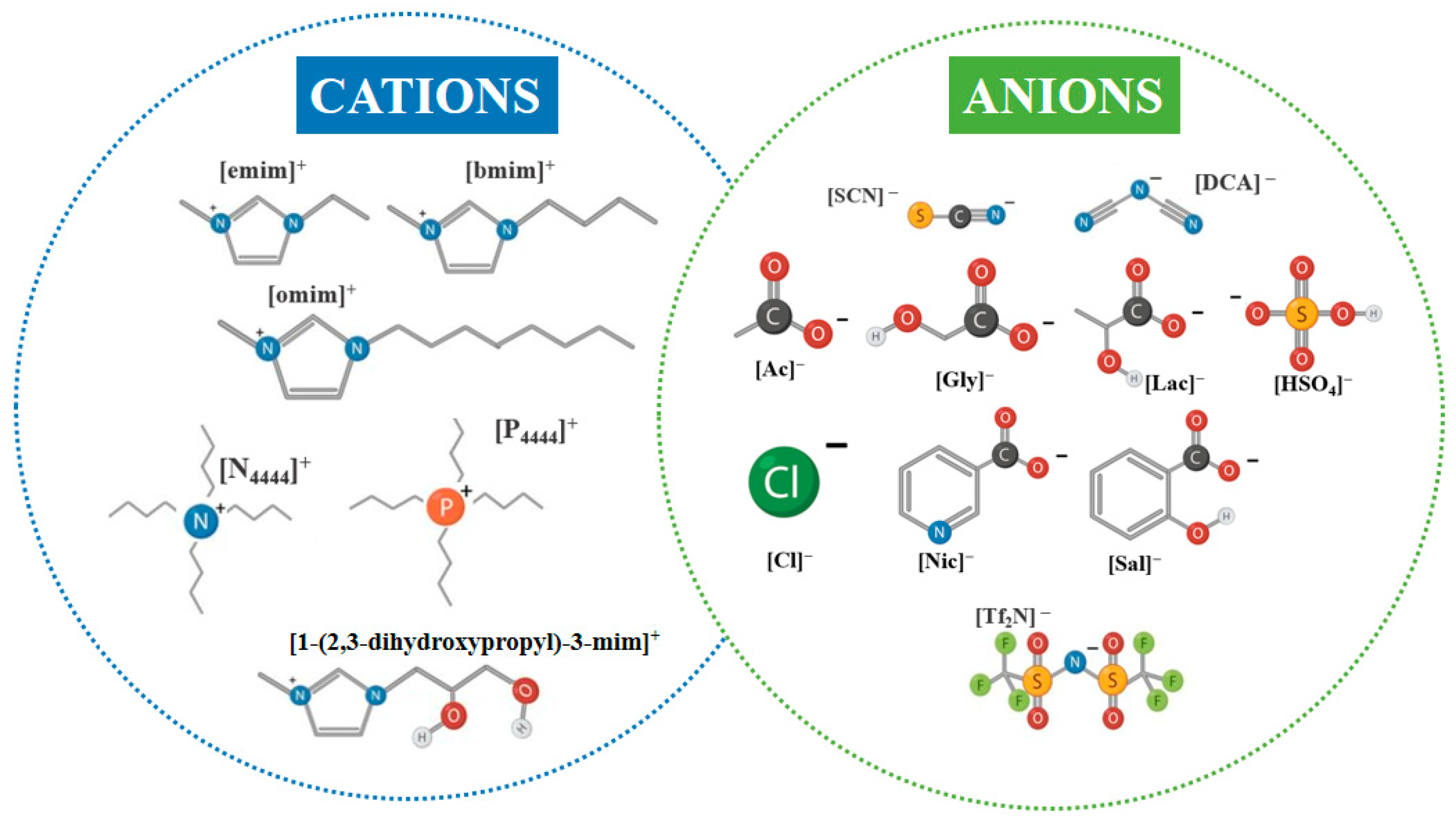

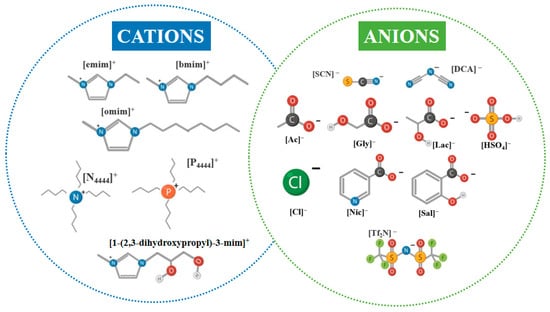

ILs are defined as organic salts consisting of bulky and asymmetric cations, such as imidazolium, pyridinium, ammonium, or phosphonium, combined with either inorganic (e.g., Cl−, [HSO4]−, [NTf2]−) or organic anions (e.g., acetate, oxalate, chelating ligands like diethylenetriaminepentaacetate, DTPA) [87]. Figure 6 illustrates representative IL cation–anion combinations relevant to LIB leaching, highlighting the broad chemical tunability of IL structures and the basis for tailoring solvent properties toward enhanced solubility, coordination, and reactivity in hydrometallurgical systems. Their low melting points (typically < 100 °C) arise from reduced lattice energy and high conformational flexibility, enabling liquid-phase stability across wide temperature ranges [88].

Figure 6.

Representative cations and anions ILs commonly employed, including those investigated for cathode material leaching.

What sets ILs apart from conventional solvents is their unique combination of physicochemical properties, including negligible vapor pressure, non-flammability, high thermal and chemical stability, and a wide electrochemical window [88,89]. These characteristics, along with their intrinsic ionic nature, make ILs suitable for high-temperature processes and applications where volatility and solvent loss must be minimized. Their non-volatile character also enables more controlled reaction environments, particularly during processes involving redox-sensitive metal species.

A particularly valuable feature of ILs is their structural tunability. Through targeted modification of the cation–anion pair, properties such as polarity, viscosity, hydrophobicity, Brønsted or Lewis acidity, and metal coordination ability can be precisely adjusted [88,90]. This design flexibility is central to their use in hydrometallurgical operations, enabling the development of task-specific ILs for selective leaching and efficient separation of critical metals from complex matrices like spent LIB cathodes [90]. Such tunability directly impacts dissolution mechanisms by controlling metal–ligand interactions, proton availability, and the stability of in-solution metal complexes.

ILs have been extensively investigated for metal extraction and separation owing to their unique ability to form metal complexes, minimize solvent evaporation, and enable the design of diverse extraction systems [91,92,93]. Unlike conventional volatile organic solvents, ILs can be incorporated into multiple hydrometallurgical platforms, offering both operational stability and environmental advantages [10,35,51]. Depending on their polarity and solubility, ILs can function as extractants in traditional aqueous–organic systems (typically using hydrophobic ILs) [94,95,96,97,98] or as components of aqueous biphasic systems (ABSs) when hydrophilic ILs [52,63,99,100,101,102,103] are employed. In both cases, the selective coordination between IL anions and transition-metal centers is the primary driver of extraction performance.

In contrast to their widespread application in extraction and separation, the use of ILs for the direct leaching of LIB cathode materials remains relatively underexplored. This limited attention is primarily attributed to the inherently high viscosity of ILs, which leads to significant mass-transfer limitations. Consequently, most research to date has centered on the leaching of metals from waste printed circuit boards (WPCBs), where ILs have demonstrated greater operational feasibility [104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. Only recently have advances in IL formulation such as acidity-enhanced phosphonium ILs and IL–cosolvent mixtures begun to reduce viscosity constraints, enabling more systematic investigation of their leaching capabilities for LIB cathodes.

In one study, Hu et al. [111] designed an imidazolium-based glycol IL, specifically 1-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-3-methylimidazolium chloride, as a leaching agent for LCO cathode material. Without the addition of external reductants or pH adjustment, the system achieved nearly complete metal dissolution (100% Li, 99.6% Co). Cobalt was subsequently recovered as cobalt oxalate and calcined to Co3O4, while lithium was isolated as lithium carbonate. The IL maintained over 80% efficiency after five reuse cycles, underscoring its potential for reuse. However, due to its high viscosity, the process was constrained to solid loadings ≤ 30 g L−1, far below the 100–200 g L−1 typical of industrial acid leaching, which significantly limits its practical throughput and energy efficiency in large-scale operations.

Mušović et al. [30] introduced an innovative approach by extending IL-based leaching to more complex NMC cathode materials, using a phosphonium-based ionic liquid, tetrabutylphosphonium hydrogen sulfate ([P4444][HSO4]). This system exhibited exceptional performance, achieving nearly complete leaching (>98%) of Li, Co, Ni, and Mn even under mild conditions (room temperature). Notably, the presence of just 20 wt% IL enabled a fourfold reduction in acid consumption compared to conventional systems. Moreover, the process tolerated high solid loadings (S/L ratio of 200 g L−1) without compromising leaching efficiency, marking a substantial advancement in IL leaching scalability. Integration with an aqueous biphasic system—formed by combining [TBP][HSO4] with ammonium sulfate—enabled the complete transfer of dissolved metals into the salt-rich phase, while the IL-rich phase remained metal-free and fully recyclable. This one-pot system, which couples leaching and extraction within a single integrated process, represents a major step forward in circular hydrometallurgy, demonstrating that task-specific ILs can effectively replace large quantities of mineral acids while maintaining high efficiency, low environmental impact, and excellent recyclability. Such an integrated design also illustrates how IL chemistry can be leveraged not only for dissolution but for downstream phase engineering and reagent reuse, addressing key limitations highlighted in conventional hydrometallurgical flowsheets.

Although ILs have been extensively studied in the context of LIBs, most reported applications relate to their use as extraction agents in hydrometallurgical workflows or as potential electrolytes in next-generation cell designs. In contrast, their direct application as leaching agents for cathode materials remains scarcely explored. To date, only two studies have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of IL-based leaching of LIB cathodes, highlighting both the technical challenges and the untapped potential of this approach. These pioneering contributions demonstrate that ILs can, in principle, achieve high dissolution efficiencies under mild conditions, but they also reveal critical limitations associated with viscosity, cost, and mass-transfer behavior. Addressing these limitations will require systematic studies that more clearly link IL structure and acidity to dissolution pathways, quantify solvent stability under leaching conditions, and evaluate strategies for reducing viscosity through cosolvents or task-specific design. Consequently, the role of ILs in cathode leaching is still in its infancy, and represents a research avenue with significant opportunities for future development, particularly in the context of circular hydrometallurgical flowsheets where solvent reuse and process integration are essential.

6. Deep Eutectic Solvents: Structure, Properties, and Overview of Leaching of LIB Cathodes

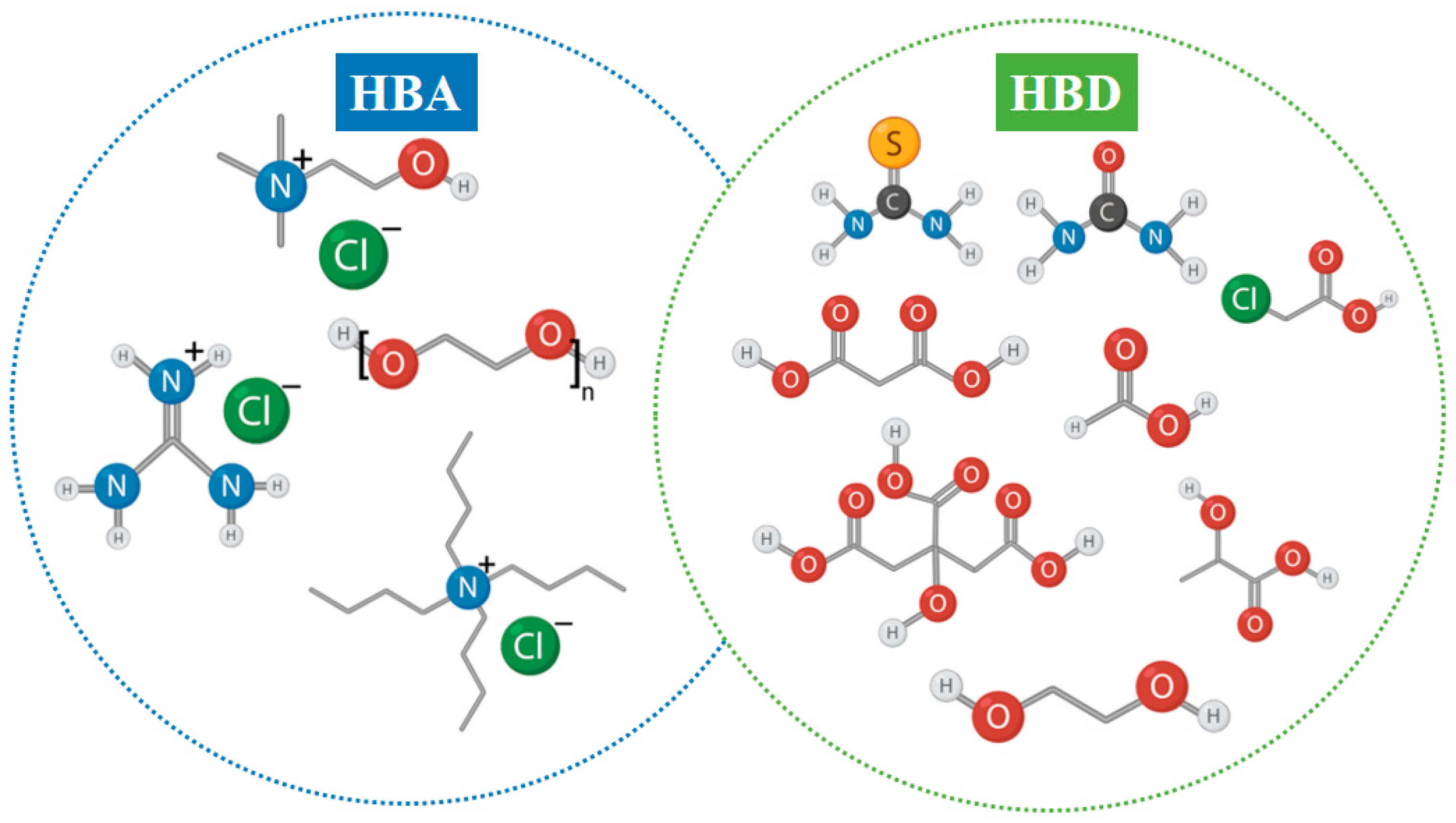

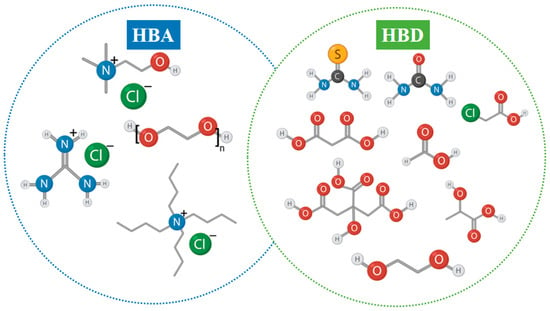

Deep eutectic solvents have emerged as a promising class of green solvents that share many desirable characteristics with ILs, such as low volatility, wide liquid range, and chemical tunability, while offering notable advantages in terms of sustainability, simplicity of synthesis, and overall cost-effectiveness [112]. DESs are typically formed through strong hydrogen-bond interactions between a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) and a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), resulting in a eutectic mixture with a melting point significantly lower than that of the individual components [113]. Common HBAs include quaternary ammonium salts such as choline chloride, while HBDs may range from urea and ethylene glycol to organic acids, polyols, and sugars [114]. Representative examples of widely used HBAs and HBDs are illustrated in Figure 7, where typical quaternary ammonium salts are shown on the HBA side, and a variety of hydrogen-bond-donating compounds—including amides, acids, and polycarboxylic structures—are shown on the HBD side. This visual overview highlights the structural diversity and design flexibility of DESs, which underpins their broad applicability in leaching processes.

Figure 7.

Representative structures of common hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs) and hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) typically employed in the formulation of deep eutectic solvents.

The appeal of DESs lies in their straightforward preparation, low toxicity, high biodegradability, and reliance on inexpensive, abundant, and often renewable components. Unlike ILs, which frequently require multi-step synthesis and purification, DESs can be obtained simply by mixing and gently heating their constituents, without additional purification or solvent removal [45,115]. Their physicochemical properties—such as polarity, viscosity, acidity, and metal coordination ability—can be finely tuned through careful selection of HBD/HBA pairs and adjustment of molar ratios. According to the seminal work of Abbott et al. [116], the presence of an oxygen-accepting component in a deep eutectic solvent—most often the hydrogen-bond donor—is crucial for cleaving metal–oxygen bonds, which constitutes the initial step in oxide solubilization. This mechanistic insight provided the foundation for subsequent studies that sought to rationalize and optimize DES-based leaching of metal oxides from complex matrices. These features make DESs particularly attractive for metal processing applications, especially for leaching critical raw materials from complex solid matrices such as spent LIB cathodes [45].

In the context of hydrometallurgy, DESs offer further benefits by functioning simultaneously as solvents and as active complexing or proton-donating agents, thereby reducing or even eliminating the need for auxiliary reagents [45,117]. Their low vapor pressure and intrinsic non-flammability make them safer alternatives to volatile organic solvents. At the same time, their ability to solubilize various metal oxides under relatively mild temperature and pH conditions opens new avenues for energy-efficient leaching strategies. Moreover, many DESs can be formulated from bio-based, recyclable, and readily available feedstocks, positioning them as key enablers of circular and environmentally responsible battery recycling processes.

Within this framework, choline chloride (ChCl) has emerged as the most widely employed hydrogen-bond acceptor for constructing DESs aimed at dissolving transition-metal oxides from spent cathodes, owing to its low cost, low toxicity, biodegradability, and the ability of chloride anions to form stable complexes with dissolved metal species [118]. When combined with carboxylic acids as hydrogen-bond donors, the resulting eutectic mixtures display a synergistic dual functionality: Brønsted acidity, which facilitates lattice disruption, and chloride complexation, which stabilizes transition-metal ions in solution. Among these systems, ChCl: citric acid (ChCl:CA) has consistently demonstrated superior performance, achieving up to 99.6% Co leaching from LCO under mild conditions, while outperforming its ChCl: malic acid analogue. This enhanced efficiency is attributed to the higher acidity of citric acid, which more effectively promotes cobalt solubilization [118]. Nevertheless, the improved reactivity is accompanied by a viscosity penalty due to the larger molecular structure of citric acid. To overcome this limitation, the addition of approximately 35 wt% water was shown to markedly reduce viscosity, enhance mass transfer, and accelerate leaching kinetics. Under optimized conditions, a 2:1 ChCl:CA molar ratio supplemented with water achieved >98% Co recovery, providing a balanced compromise between selectivity, efficiency, and process operability [118].

Building on the observation that hydration can mitigate viscosity penalties, more systematic efforts have led to the development of water-containing (“hydrated”) ChCl:CA variants specifically designed to reduce viscosity and modulate coordination chemistry. By raising the water content to approximately 25.7 wt%, viscosity decreased to ~69.1 cP, which significantly improved mass transfer and dissolution rates. Under these conditions, Li was completely leached (100%), while Co reached 97.6%, with water molecules acting as ligands that stabilized octahedral Co(II) at moderate temperatures [119]. At elevated temperatures, however, Cl− becomes the dominant coordinating ligand, which can compromise cobalt precipitation efficiency due to stronger chlorocomplex formation. Nevertheless, careful modulation of speciation during downstream treatment enabled up to 99.69% Co recovery while maintaining solvent reusability through simple recovery steps [119].

The same concept was successfully extended to NCM cathodes, where hydrated ChCl:CA DESs delivered 97.75% Li, 99.57% Co, 99.91% Ni, and 99.56% Mn. Kinetic analysis indicated that leaching proceeded via surface-controlled reactions with activation energies ranging between 46.6 and 60.2 kJ mol−1, consistent with DFT insights highlighting strong coordination between multivalent transition-metal ions and the functional groups of the DES [120]. Importantly, the process was further optimized using response surface methodology (RSM), and the recovery strategy combined Ni–Co–Mn oxalate coprecipitation with selective lithium oxalate crystallization, enabling the regeneration of high-purity precursors suitable for new cathode materials [120].

In addition to hydration strategies, accelerated processing has been demonstrated through microwave-assisted leaching. For example, a ChCl/oxalic acid (ChCl:OA) system achieved ~99% Li and ~96% Mn recovery at only 75 °C within 15 min, illustrating how mild heating, activation of the hydrogen-bond network, and oxalate complexation can act synergistically to shorten leaching times while preserving high recovery yields [121]. These results highlight how hydration and microwave activation provide complementary levers for overcoming viscosity and kinetic limitations, thereby advancing the practicality of DES-based leaching systems.

Within the broader family of ChCl–acid DESs, the ChCl/lactic acid (ChCl:LA) system provides a particularly instructive example of redox-assisted leaching. On its own, ChCl:LA shows limited ability to dissolve Mn from the LMO cathode, yet the incorporation of ascorbic acid (AA) as a benign reductant enabled quantitative leaching of both Li and Mn (>99%). Structural and spectroscopic analyses confirmed the process: XRD showed the disappearance of LMO lattice, SEM-EDS revealed a sharp reduction in Mn content (to 1.42 wt%) accompanied by an increase in carbon attributed to the oxidation of AA to dehydroascorbic acid, and XPS verified the reduction of Mn(IV/III) to Mn(II) [122]. In a complementary study, Cao et al. [123] employed the same ChCl:LA (1:2) solvent under even mild conditions (50 °C), thereby enabling the use of low-grade heat and eliminating the need for external reductants. In this case, the solvent’s inherent reducing power and high proton availability allowed selective leaching of Li (93%) and Mn (~60%) into the liquid phase, while Co and Ni formed insoluble lactate complexes that were easily separated by washing. The proposed four-step protocol demonstrated not only environmental compatibility and solvent reusability but also economic feasibility, with an estimated operating cost of USD 1.49 per kg of NMC cathode material and a potential revenue of USD 16.35 per kg, based on prevailing metal prices [123]. These findings align with broader solvometallurgical screening, which showed that ChCl:LA consistently outperforms ChCl/glycerol due to its lower pH and stronger acidity. Under optimized conditions, it enabled complete dissolution (up to 100%) of Li, Mn, Ni and Co from LMO, and NMC cathodes. Importantly, the system facilitated a two-step recovery strategy, involving precipitation of Ni and Co as oxalates using solid oxalic acid, followed by lithium capture. The solvent could be regenerated and reused for at least three cycles, while the aluminum current collector and binder remained undissolved, ensuring straightforward solid–liquid separation and advancing the principles of circular economy [124].

A related system based on ChCl/tartaric acid (ChCl:TA) further demonstrates how molecular design can tailor performance at lower temperatures. At 70 °C, ChCl:TA exhibited high leaching efficiencies that improved with controlled water addition, and kinetic analysis indicated a transition from diffusion to chemically controlled mechanisms as the process progressed. Antisolvent crystallization with ethanol enabled the recovery of >98.5% Co, Ni and Mn as tartrate precursors suitable for direct NMC resynthesis, while lithium recovery remained more sensitive to hydration level, ranging between 65 and 77% [125].

Switching the hydrogen-bond donor class from carboxylic acids to polyols produces a distinctly different balance between kinetics, stability, and energy input. The most studied representative, ChCl/ethylene glycol (ChCl:EG), has repeatedly been cited for its ability to dissolve both cobalt and lithium from spent cathodes, achieving 94.14% Co and 89.81% Li. However, such performance was only reached under rather severe conditions of 220 °C for 24 h, with cobalt leaching rising from 50.3% at 180 °C to 94.14% at 220 °C under otherwise identical parameters. The characteristic blue coloration of the post-leaching solution has been attributed to the formation of [CoCl4]2− complexes, confirming a chlorocomplexation pathway [126]. A more critical assessment, however, revealed that ChCl:EG undergoes irreversible degradation near 180 °C, generating trimethylamine and 2-chloroethanol through a radical β-hydrogen abstraction mechanism on the choline moiety. This degradation occurs concurrently with Co(III) to Co(II) reduction, which has sometimes been misinterpreted in the literature as a benign “green” solvent effect. In reality, the instability of the solvent severely limits recyclability and raises significant environmental, health, and safety (EHS) concerns, leading to the conclusion that ChCl:EG should not be deployed at high temperature, particularly in the absence of a controlled reducing environment [127].

Mechanistic studies provide additional nuance: ethylene glycol is proposed to interact with the cathode lattice via hydrogen bonding to M–O units, potentially weakening the oxide framework and facilitating subsequent proton- or chloride-mediated bond cleavage. However, this interaction remains hypothesized rather than experimentally demonstrated, as no direct spectroscopic confirmation (e.g., XAS, solid-state NMR, Raman) has yet been reported. In contrast, the role of chloride ions is firmly established: multiple studies have directly verified the formation of chlorometalate species through Cl− coordination to transition-metal centers, providing a robust, experimentally supported dissolution pathway that is absent for ethylene glycol. This distinction underscores that, within ChCl-based DESs, chloride-driven complexation is the primary mechanistic contributor to transition-metal dissolution, whereas ethylene glycol plays—at most—a secondary, structure-modifying role.

Lithium displays a different behavior, remaining only loosely associated with chloride and therefore leaching more rapidly due to the absence of strong inner-sphere complexation. Moreover, higher ChCl content promotes more extensive complex formation and improves overall metal-dissolution performance [128].

Building on these mechanistic insights, Wang et al. [129] designed an integrated recycling strategy for NMC cathode materials using a glycol-based ChCl DES. Under optimized conditions, this system achieved 91.63% Li, 92.52% Co, 94.92% Ni, and 95.47% Mn, with kinetic analysis confirming that the leaching process followed the shrinking-core model governed by chemical reaction control. Importantly, dissolution proceeded through coordinated participation of the DES components: chloride-driven complexation of transition metals and rapid lithium release, consistent with the speciation trends described above.

The dissolved metals were subsequently recovered through a co-extraction step with extractant P507, followed by coprecipitation to regenerate NMC cathode material. Infrared spectroscopy suggested that metal ion transfer occurred via a cation exchange mechanism, and P507 demonstrated excellent extraction efficiency, recovering ~90% Li and nearly 100% Co, Ni, and Mn. The loaded extractant was efficiently stripped using H2SO4, enabling repeated reuse of P507. The regenerated NMC cathode material exhibited electrochemical performance comparable to commercial active materials, while the process flowsheet demonstrated high solvent reusability and low reagent consumption. Economic evaluation indicated substantial cost savings of approximately USD 44.72 per kg when recycled precursors replaced commercial ones. Overall, this integrated approach illustrates how ChCl:EG—despite its thermal-stability constraints—can be deployed within a circular recycling framework when operated under controlled conditions, achieving both environmental benefits and economic viability [129].

Because urea provides both strong hydrogen-bonding capacity and intrinsic reducing functionality, its use as a hydrogen-bond donor in ChCl-based DESs has drawn considerable attention. Recognizing that redox capacity is a strong predictor of low-energy leaching, researchers have increasingly relied on electrochemical screening as a rational design tool. By combining DFT/Fukui function analysis with cyclic voltammetry, ChCl/urea was demonstrated to possess a significantly more negative reduction potential than the corresponding ChCl:EG system. This enhanced reducibility translated directly into improved leaching performance: under optimized conditions, the ChCl/urea DES achieved ~95% Li and Co recovery at a substantially lower temperature of 180 °C and in only 12 h, while also maintaining solvent reusability. These results underscore how the inclusion of urea as a hydrogen-bond donor enables a more energy-efficient and sustainable pathway for critical-metal dissolution, offering a practical alternative to polyol-based DESs within the broader ChCl portfolio [130].

Beyond simple binary systems based on ChCl with acids or polyols, the development of sulfonic acid and ternary ChCl-based DESs introduces an additional level of tunability by combining in situ acidity with chloride complexation and, in some cases, intrinsic reducing power. A representative example is the PTSA:ChCl eutectic, which achieved nearly 94% Co leaching from smartphone-derived cathodes while operating at low solute-to-solvent ratios, a practical advantage that minimizes chemical consumption and facilitates scale-up [131]. Similarly, the malonic acid/ChCl system and its ternary variants with PTSA (PTSA + malonic acid/ChCl, PTSA:ChCl) demonstrated high efficiency under mild conditions, enabling 98.61% Co and 98.78% Li dissolution at only 100 °C without the need for external reductants. XANES/XAFS analyses confirmed the presence of in situ reducing activity and the formation of [CoCl4]2− complexes, while the enhanced proton availability in the ternary mixtures further promoted cobalt reduction. Subsequent treatment with Na2CO3 enabled the selective precipitation of cobalt into precursors suitable for electrode resynthesis, exemplifying how these DESs can function simultaneously as leaching agents and reductants in low-temperature flowsheets [132].

Although ChCl dominates the HBA landscape, recent studies have increasingly explored alternative hydrogen-bond acceptors as tunable and, in some cases, lower-temperature options for metal dissolution. A representative example is the guanidine hydrochloride (GH)/formic acid (FA) system, which achieved rapid and highly efficient leaching of Li (99.79%), Ni (98.86%), Co (99.51%), and Mn (96.12%), with kinetics governed by surface chemical reaction control. The addition of oxalic acid to the pregnant DES enabled the coprecipitation of mixed oxalates, which served as precursors for NCM cathodes delivering 162.72 mAh g−1, while the DES phase itself was recovered by filtration and distillation for reuse—demonstrating a dual recycling pathway for both metals and solvent [133].

Other studies have highlighted the versatility of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based DESs. Ketegenov et al. [134] reported that combining a PEG–thiourea DES with ultrasound irradiation produced a clear synergistic effect, significantly enhancing metal recovery from spent LCO. Under optimized conditions (160 °C, intermittent ultrasound), the process achieved 74% Li and 71% Co leaching within 24 h. In a related study, a PEG200–thiourea DES underscored the role of donor electronic structure: while cobalt recovery reached only 60.2% at 160 °C, the findings pointed to S/N coordination and redox activity of thiourea as critical for lattice breakdown under harsher conditions [135]. Expanding the scope of PEG-based systems, Chen et al. [136] developed a PEG/phytic acid (PHA) DES that delivered an ultrahigh 98.7% Co leaching efficiency at just 80 °C for 24 h (1:1 molar ratio, S/L ratio = 50 g L−1), far outperforming most previously reported DESs, which under similar conditions reached efficiencies closer to 30%. Likewise, Chen et al. [137] demonstrated that a PEG/ascorbic acid (6:1) DES could leach 84.2% Co from LCO at 80 °C (72 h, S/L ratio = 100 g L−1), with dissolution driven by the reductive transformation of Co(III) to Co(II) mediated by ascorbic acid.

The growing diversity of non-ChCl DESs also includes quaternary ammonium–based formulations. Zhang et al. [138] proposed a novel route for LCO recovery using a DES composed of chloroacetic acid (CAA) and tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBAC), enhanced by oxalic acid as a co-leaching and precipitating agent. Under optimized conditions (100 °C, S/L ratio = 15 g L−1, 7 h, oxalic acid), cobalt was completely dissolved while lithium precipitated in situ as lithium oxalate with 97.8% efficiency. Crucially, the DES could be reused at full efficiency in a second cycle simply by evaporating water, underscoring its operational simplicity and recyclability.

At the interface of green chemistry and bio-derived solvents, natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs) have emerged as particularly promising alternatives. Sarma et al. [139] synthesized NADESs from plant-derived polyphenols, sugars, amino acids, and choline derivatives, offering excellent metal-binding capacity, biodegradability, and non-toxicity. Applied to both LCO and NMC cathodes, these NADESs achieved 98% leaching for LCO and 94.5% for NMC. The dissolution proceeded via a reductive mechanism, where polyphenols facilitated oxide breakdown and the stabilization of metal ions as chlorometalates through their strong reducing and chelating properties. Optimal performance was observed at 140 °C, a temperature that balanced energy efficiency with high extraction rates, while reaction time remained a decisive factor in maximizing yields.

Finally, phenylphosphinic acid–based DESs further expand the mechanistic diversity of alternative systems. When combined with ChCl, this solvent achieved 97.7% Li, 97.0% Co, 96.4% Ni, and 93.0% Mn recovery at 100 °C (L/S ratio = 90 mL g−1, 80 min). Kinetic analysis showed that the process followed a logarithmic rate law, with distinct activation barriers for each cation (60.3 kJ mol−1 for Li, 78.9 for Co, 99.3 for Ni, 82.1 for Mn). Spectroscopic evidence (UV–Vis, FTIR) confirmed that metal ions were stabilized through P–O coordination, with octahedral Ni and tetrahedral Co species forming in solution [140]. These results emphasize that by moving beyond the conventional ChCl platform, DESs can be systematically designed with tailored coordination environments, enabling high-efficiency leaching under milder and more controllable conditions.

In addition to the extensive research on hydrophilic DESs, recent efforts have also focused on hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents (HDESs), which offer a distinct operational advantage by facilitating efficient phase separation and selective metal recovery. Carreira et al. [141] developed an integrated process using a hydrophobic DES composed of tri-octylphosphine oxide (TOPO) and decanoic acid, which acts as an HCl superconcentrator, reaching effective acid concentrations up to 2.2-fold higher than the aqueous 37 wt% limit. Under optimized conditions (0.93 mol L−1 HCl, S/L ratio= 44 g L−1, 100 °C, 4 h), this system enabled quantitative leaching of Co, Mn, and Cu from black-mass cathode residue, while approximately 90% of Ni remained in the solid phase. A carefully designed sequential precipitation strategy then allowed the selective recovery of 98% Mn as Mn3O4 (81% purity) and 99% Co as cobalt oxalate (95% purity), leaving lithium in solution as LiCl. Notably, the DES phase could be regenerated by simple water washing and reused for at least five consecutive cycles without significant loss of efficiency or selectivity.

Complementary work by Hanada et al. [142] expanded this concept using hydrophobic eutectic solvents prepared from diketone and alkyl phosphine oxide combinations (e.g., HBTA/TOPO 2:1 and decanoic acid/TOPO 1:1). Here, subsequent stripping with aqueous oxalic acid facilitated efficient metal recovery, while the addition of ascorbic acid as a natural reductant promoted the reduction of Co(III) to Co(II), thereby improving leaching performance. Under optimized conditions, over 90% of Li and Co were leached from both LCO and NMC cathode materials, with cobalt selectively recovered as oxalate and lithium retained in the aqueous phase. Despite the hydrophobic nature of these solvents, a small amount of water proved essential for efficient leaching, highlighting the delicate balance between hydrophobicity and reactivity. Importantly, the HES phases could be regenerated and reused across multiple leaching and stripping cycles without noticeable performance losses, reinforcing their potential for sustainable and selective metal recovery.

Water plays a crucial role in improving the leaching efficiency of hydrophilic DES-based systems [118]. Water content affects both the macro-performance and microstructure of DES [125], primarily by significantly reducing viscosity and thereby enhancing mass transfer efficiency [143]. For example, when the water mass fraction in a CA:ChCl DES increased from 22.88% to 53.39%, viscosity dropped from 102.39 to 13.30 mPa·s, with optimal leaching efficiency observed at 38.16% water content [144]. Excessive water, however, can disrupt the hydrogen bond network of DES, leading to component dilution and decreased metal extraction [145,146].

Hydrophobic DESs offer notable advantages in recyclability and waste minimization owing to their intrinsic immiscibility with water. Their ability to form a separate organic phase enables straightforward solvent recovery by decantation, thereby reducing energy input and eliminating the neutralization steps typically required for hydrophilic systems. In addition, hydrophobic DESs show lower susceptibility to hydrolysis and thermal degradation compared with highly hydrated ChCl-based mixtures, which generally supports a higher number of effective reuse cycles. As a result, these systems tend to produce smaller aqueous waste streams and reduced solvent losses, although the presence of metal-rich organic residues may necessitate an additional purification step prior to closed-loop reuse. However, their typically higher viscosity and slower mass-transfer rates can limit leaching kinetics, indicating that the benefits in recyclability must be balanced against potential reductions in operational efficiency. In practice, the choice between hydrophilic and hydrophobic DESs thus reflects a trade-off between kinetic performance and ease of solvent recovery.

Taken together, the growing body of work on DES-based leaching of LIB cathode materials highlights a generalized mechanistic framework that integrates both chemical and structural contributions of the eutectic medium. At its core, the process involves (i) the chemical reduction of high-valent transition metals, such as the transformation of Co(III) to Co(II); (ii) the stabilization of reduced metal species through chlorocomplex formation, often mediated by chloride derived from choline-based acceptors; and (iii) the proton-assisted disruption of the oxide lattice, where protonation drives M–O bond cleavage and concomitant water formation. These primary steps are reinforced by the hydrogen-bond network linking donor and acceptor components, which governs solvent polarity, acidity, viscosity, and redox behavior, thereby fine-tuning both dissolution kinetics and metal selectivity. This unified view helps rationalize why systems that simultaneously provide protons, chloride ligands, and reducing functionality tend to show superior leaching performance.

A particularly important mechanistic distinction concerns the role of water in modulating DES structure and reactivity. In anhydrous DESs, metal dissolution proceeds through direct coordination with chloride, urea, or carboxylate ligands, often coupled with HBD-derived reduction pathways that efficiently lower Co(III) to Co(II). As water content increases, the eutectic hydrogen-bond network becomes progressively disrupted, reducing viscosity but also shifting metal speciation toward aqua and hydroxo complexes. Moderate hydration can therefore accelerate dissolution by improving mass transport, whereas high hydration suppresses chlorometalate formation, weakens reductive pathways, and reduces the intrinsic selectivity of DESs for Co and Ni relative to Li or Mn. These trends demonstrate that hydration governs the balance between DES-specific coordination chemistry and water-dominated dissolution mechanisms, offering a critical design parameter for tuning both kinetics and selectivity.

Despite these shared mechanistic features, the performance of DESs is highly system-dependent. ChCl–acid DESs, particularly those with citric, lactic, and tartaric acid donors, achieve exceptional recovery of Co, Ni, Mn, and Li under comparatively mild conditions, but are often limited by high viscosity—an issue effectively mitigated through water addition or microwave assistance. Polyol-based systems such as ChCl:EG demonstrate high efficiencies but suffer from poor thermal stability, generating hazardous by-products that undermine their green credentials, whereas urea-based DESs have emerged as more energy-efficient alternatives owing to their stronger reducing capacity. Sulfonic acid and ternary systems provide the dual functionality of acidity and intrinsic redox activity, thereby enabling metal recovery without external reductants. Beyond the ChCl platform, PEG-, ammonium-, and NADES-based systems expand the chemical design space, incorporating bio-derived donors such as polyphenols or leveraging ultrasound to accelerate leaching, while hydrophobic DESs introduce unique operational advantages by acting as acid concentrators and facilitating selective phase transfer and recovery. Collectively, these results demonstrate that DES formulation is a multi-dimensional optimization problem in which donor/acceptor identity, hydration level, and process intensification strategies must be co-designed.

Overall, these findings underscore both the versatility and complexity of DES chemistry in hydrometallurgy. On one hand, DESs offer clear advantages over conventional solvents and many ionic liquids: simple preparation, tunable physicochemical properties, potential for regeneration, and compatibility with mild and energy-efficient operating conditions. On the other hand, significant challenges remain, particularly regarding the long-term stability of different formulations, the precise contributions of donor vs. acceptor components to dissolution mechanisms, and the need for systematic correlations between molecular structure, redox potential, and leaching performance. Addressing these gaps will require not only expanded mechanistic studies, but also pilot-scale demonstrations that evaluate solvent recycling, cost efficiency, and environmental safety under realistic operating conditions. Such studies are essential to move from proof-of-concept leaching experiments to robust process designs suitable for industrial implementation.

By integrating these mechanistic insights with advances in solvent design and process intensification, DES-based leaching can evolve from a promising laboratory concept into a viable, circular hydrometallurgical technology for sustainable lithium-ion battery recycling. In this context, DESs are best viewed not merely as alternative solvents, but as integrated reaction media whose structure, composition, and operating window must be engineered alongside the overall process flowsheet. To situate these qualitative insights within a broader performance landscape, Table 2 summarizes representative quantitative metrics reported for IL- and DES-based leaching systems, enabling a direct comparison of their operational behavior and recovery efficiencies.

Table 2.

Representative quantitative parameters for IL- and DES-based leaching of LIB cathode materials.

In order to situate the performance of these emerging DES/IL technologies within the broader landscape of hydrometallurgical practices, it is instructive to contrast the values summarized in Table 2 with those achieved by conventional mineral acid leaching, which remains the current industrial benchmark. For instance, sulfuric acid leaching has been demonstrated to achieve virtually quantitative dissolution of Co, Ni, and Li, and up to ≈ 93% Mn under optimized conditions (1 mol L−1 H2SO4, 90 °C, S/L ratio = 100 g L−1) from NMC-type cathodes [147]. Moreover, recent reviews confirm that H2SO4− or HCl-based hydrometallurgical routes are still widely applied due to their robustness and high recovery efficiencies [9].

Although DES and IL systems can achieve comparable recoveries (typically 70–100% for Co and Ni)—often under milder temperatures, lower acid strengths, or tunable redox conditions—the contrast with mineral acids highlights that their strategic advantage is not necessarily superior dissolution, but improved selectivity, solvent recoverability, waste minimization, and enhanced process sustainability [148].

A comparison of kinetic behavior further reinforces these distinctions. Conventional mineral acids generally operate under mixed diffusion–surface reaction regimes with activation energies between ~5 and 70 kJ mol−1 [149]. Hydrochloric acid, for example, leaches LiCoO2 more rapidly than DESs but at the cost of diminished selectivity, hazardous Cl2 evolution, and rapid dissolution of aluminium current collectors. In contrast, choline chloride–citric acid DES requires cooperative proton–chloride activation of the oxide lattice and proceeds under milder, inherently selective conditions, with redox contributions from metallic current collectors (e.g., Cu-mediated reduction of Co(III) to Co(II)) [127].

DES kinetics frequently lie in the diffusion-limited regime, particularly in viscous formulations, with apparent activation energies of ~13–40 kJ mol−1 for diffusion-controlled systems and up to ~60–100 kJ mol−1 when surface reaction dominates [119,120,132,141]. These observations, when viewed together with the operational parameters summarized in Table 2, indicate that although DES-based leaching typically proceeds more slowly, it offers substantial benefits in energy efficiency, selectivity, and solvent recyclability—key considerations for sustainable process design and industrial-scale implementation.

7. Post-Leaching Processing Steps

Following the complete dissolution of cathode materials in DESs or HESs, a crucial step toward achieving process circularity is the efficient recovery of the dissolved metal ions. Numerous strategies have been reported in the literature, including selective precipitation, solvent extraction and stripping, antisolvent crystallization, electrodeposition, and directional precipitation. These approaches not only enable the isolation of high-purity metal salts but also allow the direct resynthesis of cathode precursors. Furthermore, several studies have systematically investigated the reusability of DESs and HESs, thereby strengthening the prospects of implementing these systems in sustainable recycling processes.

The recovery of cobalt has been extensively studied, with oxalate precipitation emerging as the most frequently applied approach. In a seminal contribution, cobalt was selectively extracted from a choline chloride–citric acid (ChCl:CA) DES using the quaternary ammonium extractant Aliquat 336, and subsequently precipitated as cobalt oxalate with 99.9% purity, resulting in an overall cobalt recovery of 81% [118]. Direct precipitation with oxalic acid from the same DES system under mild conditions (20 °C, 30 min) achieved even higher efficiency, with 99.69% recovery [119]. Complementary studies confirmed that carbonate-based routes are also viable. For instance, Na2CO3 addition yielded mixtures of CoCO3, Co(OH)2, and Co3O4, while electrodeposition enabled the formation of Co(OH)2 directly on a stainless steel mesh [126]. In a different DES system, selective transformation of CoCl2 into CoCO3 achieved ~97% precipitation efficiency, while subsequent calcination produced phase-pure Co3O4 [131]. More recently, ultrapure water was demonstrated as an effective stripping agent, leading to >90% recovery of Co as CoC2O4 [138], while sequential precipitation approaches afforded Co(OH)2 with high selectivity [139]. Additional reports further confirmed that oxalate precipitation could achieve yields above 99%, with products of 95–99% purity [141,142]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that cobalt can be quantitatively recovered by multiple precipitation strategies, providing crystalline oxalates, hydroxides, or oxides suitable as cathode precursors.

Lithium recovery has also been successfully integrated into post-leaching flowsheets. In early reports, lithium was precipitated as Li2C2O4 with ~59% recovery and 99% purity from ChCl:CA DES leachates [119]. Sequential precipitation schemes showed that lithium accumulated in the DES phase during repeated use, and could be separated at later stages with high purity as Li2C2O4 [120]. Similar approaches confirmed that lithium remained in the raffinate (>94.5%) during selective oxalate precipitation of transition metals, thus simplifying its downstream recovery [123]. In co-extraction systems, lithium could be efficiently extracted by organophosphorus extractants such as P507, achieving nearly 90% recovery, and subsequently precipitated as Li2CO3 [129]. Other studies confirmed lithium carbonate recovery from DES leachates upon pH adjustment [133]. A particularly efficient route was reported with CAA:TBAC DES, where lithium was directly separated by filtration as Li2C2O4 with >97% yield and >99.5% purity, without the need for additional reagents [138]. Furthermore, in HES systems, oxalic acid stripping enabled quantitative lithium separation into the aqueous phase with 99% purity [142].

Nickel recovery typically proceeded through oxalate precipitation. In ChCl:CA DESs, Ni co-precipitated as NiC2O4 alongside Co and Mn, providing a mixed precursor suitable for NCM resynthesis [118]. Other reports achieved >97.9% Ni recovery under similar conditions [123]. In choline chloride–lactic acid DESs supplemented with oxalic acid, nickel oxalates precipitated with yields consistently above 80%, while lithium remained in the DES phase [124]. Directional precipitation strategies expanded the repertoire, with Ni isolated as square-planar Ni(DMG)2 complexes, confirmed by XRD and FTIR analyses [139]. High-efficiency solvent extraction routes also achieved nearly complete nickel recovery, particularly when P507 was applied under optimized saponification and O/A ratios [129].

Manganese recovery has been more variable due to its complex redox behavior. In oxalate-based precipitation schemes, MnC2O4 was obtained in co-precipitated mixtures with Co and Ni [120], while selective precipitation achieved ~71% Mn recovery [123]. In other systems, oxalic acid facilitated >80% Mn recovery alongside Ni and Co [124]. More elaborate directional precipitation enabled the selective formation of MnO2 using ammonium persulfate at elevated temperature, providing phase-pure MnO2 [139]. In DES–HCl systems, oxidative precipitation with KMnO4 yielded Mn3O4 at 98% recovery [141]. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring precipitation strategies for manganese, often in combination with other transition metals.

Beyond conventional precipitation, alternative approaches have been developed. Antisolvent crystallization in a ChCl:TA DES achieved >98.5% recovery of Co, Ni, and Mn, while lithium recovery ranged from 65 to 77% [125]. The tartrate-based precipitates served as direct NMC precursors, which, upon calcination, yielded layered oxides with reduced cation mixing. Directional precipitation methods enabled sequential isolation of MnO2, Ni(DMG)2, and Co(OH)2, thereby providing a high degree of selectivity [139]. Such strategies expand the processing toolbox beyond standard oxalate and carbonate precipitation.

A critical factor for process sustainability is the reusability of DESs and HESs. Multiple studies confirmed that these solvents can maintain high leaching and precipitation efficiencies over several cycles, with varying degrees of regeneration required. In ChCl:CA DES, cobalt recovery declined from 99.69% to 88.75% after three cycles, but reintroducing 20 wt% citric acid restored performance. Similar systems showed >97% efficiency in the first two cycles, followed by a decline to ~80% in the third, attributed to citric acid degradation [120]. Other reports indicated decreasing efficiencies for lithium and manganese to ~75–80% after three cycles [123], while ChCl:LA:OA DES maintained stable Ni/Co recovery through three cycles before declining [124]. Antisolvent crystallization studies revealed only modest efficiency losses (7–14%) in regenerated DES [125]. Structural analyses of reused DESs generally indicated minimal changes, though partial loss of hydrogen bond donor components was common [133]. More robust regeneration was demonstrated in DES–HCl systems, which maintained near-quantitative metal recovery over five leaching–stripping cycles [141]. Finally, HESs such as HBTA/TOPO were shown to be reusable for at least three cycles, with only minor performance degradation after repeated washing to remove oxalic acid residues [142].