Abstract

The edible insect industry produces ingredients that are utilised in both animal feed and human food. However, the quality control of these ingredients and products is carried out using traditional routine chemical analysis, which generates waste and is considered both costly and time-consuming. Therefore, these techniques are not considered suitable for a sustainable and green industry. Consequently, the edible insect industry requires environmentally friendly methods that can be used in quality control along the insect supply and value chains. Most of these methods are based on the use of molecular spectroscopy and optical sensors (near- and mid-infrared, Raman spectroscopy) that allow for the large-scale analysis of chemical composition, authentication, and traceability of the products and processes, helping the real-time data collection and management decision tools. This paper provides an overview of the use of rapid and objective techniques in different examples associated with edible insects.

1. Introduction

Edible insects are considered important to ensure feed and food security [1,2,3,4,5,6]. More importantly, the utilisation of edible insects as a food ingredient is gaining importance due to the high nutritional value they possess. Additionally, their production systems are considered to be more environmentally friendly than traditional livestock farming systems [1,2,3,4,5]. Edible insects farmed for commercial purposes are characterised by high protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and other nutrients that are of importance to the human diet [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Other minor compounds such as polyphenols, microminerals (e.g., iron, zinc, and copper), and macro minerals have been found in the larvae and pupae of different edible farming insects, contributing to the nutritional value of these ingredients [1,2,3,4,5]. In addition to the nutrient-rich ingredients they provide, edible insects are characterised with different functional properties that can be utilised in a wide range of industries, including food (e.g., baking industry), cosmetics, medical and pharmaceutical applications, biotechnology, and as an ingredient in animal feeds [7,8,9]. In all these applications, it is important to characterise the chemical composition and other properties of the insects beyond crude protein measurement. Thus, the total lipid, fatty acid, and amino acid profiles, as well as chitin and the functional properties (e.g., emulsification, gelatinisation, water absorption) that contribute to the techno-functional properties of the food, must be evaluated [9,10,11].

Edible insects are not only used as food ingredients for humans but also as feed ingredients in animal production, where they have been considered a sustainable source of protein [9,10,11]. Various studies have demonstrated that insects, such as black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens, BSFL), can be added to animal feed without compromising animal growth performance [8]. However, more information is needed on the chemical composition, traceability, and safety of the different edible insect species before they can be considered as a feed ingredient [8]. These findings also play an essential role in supporting legislation under development [12]. Due to their high protein biological value and digestibility, insects have been used as alternative sources of protein in poultry [13,14], pig [15], ruminant [16], and fish nutrition [17,18,19]. The possibility of using edible insects has also contributed to food security in different countries where the importation of protein-rich plant sources such as soybean and corn can be reduced [8]. Consequently, novel and eco-conscious protein sources like edible insects have contributed to tackling protein deficiency in different countries, and subsequently improving the efficiency of the production systems, decreasing the pressure on ecosystem services and widening the prospects of improving food security [8,20].

It is estimated that approximately 2000 insect species are consumed worldwide [21]. The most common insects used commercially are house cricket adults (Acheta domesticus), field cricket adults (Gryllus bimaculatus), mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor), palm weevil larvae (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus), and black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) [21]. In recent years, the EU (Regulation 2015/2283) approved the use of seven insect-derived products as new food ingredients for human consumption by the European Commission (2015) [12,21]. However, new regulations require that labels include information about the presence of edible insects. Therefore, the information about species must also be included in the list of authorised novel foods in addition to the nutritive value before their utilisation and commercialization [12,21]. For animal feed, a broader range of insect species in various forms are accepted, including whole insects, live insects, insect proteins, insect fats, and hydrolysed insect proteins [22]. In Europe, the following eight insect species have been approved for use in animal feed and include Hermetia illucens (black soldier fly), G. sigillatus (banded cricket), Gryllus assimilis (Jamaican field cricket), A. domesticus (house cricket), A. diaperinus (lesser mealworm), T. molitor (yellow mealworm), Musca domestica (housefly), and Bombyx mori (silkworm) [12,21].

Edible insects as a source of protein and other nutrients are considered eco-friendly and sustainable [10,11]. However, the quality control of these ingredients and products is performed using traditional routine chemical analysis, which generates chemical waste and is considered costly and time-consuming [23,24]. Therefore, these techniques are not regarded as suitable for a sustainable and green industry [23,24]. Consequently, the insect industry requires environmentally friendly methods for quality control along the insect supply and value chains [23,24]. Vibrational spectroscopic techniques represent valuable, rapid, non-destructive, and green methods that can be used throughout the edible insects’ supply and value chain, from production plants to the end user (e.g., human food or animal feed) [8,20]. Most of these methods are based on molecular spectroscopy and optical sensors that enable large-scale analysis of chemical composition, authentication, and traceability of products and processes, facilitating real-time data collection and decision-making tools.

This paper provides an overview of the use of rapid, objective techniques across different examples of edible insects.

2. The Tools—Vibrational Spectroscopy and Data Analytics

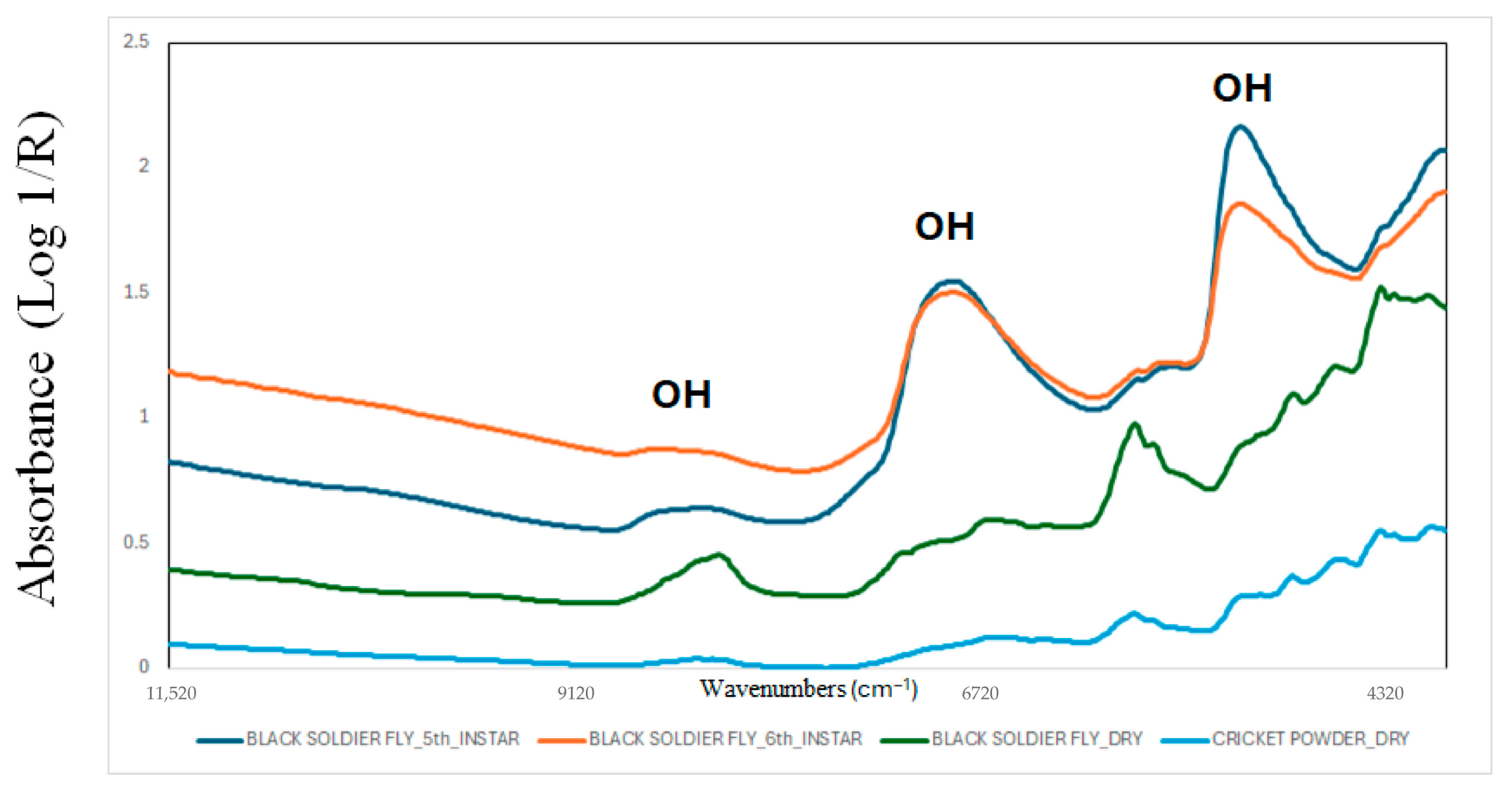

Different vibrational techniques have been evaluated for their ability to predict the chemical composition of foods and feeds [23,24,25]. The most widely used techniques are near-infrared (NIR, 750–2500 nm), mid-infrared (MIR, 1400–3000 nm), and Raman spectroscopy [26,27,28,29]. More recently, hyperspectral imaging (HSI), an analytical method that integrates imaging technology with spectroscopy, has also been used for this purpose [26]. However, other techniques, including infrared microscopy and fluorescence, have also been evaluated to characterise edible insects [30]. Applications and implementation of these techniques require the utilisation of chemometrics or machine learning (ML) [31,32]. Chemometrics and ML algorithms are used to interpret collected spectral data and develop models for quantitatively or qualitatively analysing samples [31,32]. The implementation of these techniques, in combination with ML, required preprocessing, training, and internal and external validation of the spectral data to construct the model and evaluate its future performance [33,34,35]. Figure 1 showed the NIR spectra of BSFL (Hermetia illucens) collected at two instars, as well as both BSFL and cricket dry powder samples. The figure shows that the NIR spectra provides us with information about the chemical characteristics of the samples. Absorbances in wavenumbers related to O-H bonds (around 8300 cm−1, 6800 cm−1, 5000 cm−1) are associated with water or moisture content, wavenumbers related to C-H bonds (between 5600 and 5700 cm−1, and above 5000 cm−1) are associated with carbohydrates, lipids, or fatty acids, and wavenumbers related to N-H bonds (around 6900, 6700, 5000, 4800 cm−1) are associated with protein content or amino acids. Other chemical characteristics or properties can also be associated with different wavenumbers or functional groups [26,27,28,29].

Figure 1.

Near-infrared spectra of black soldier fly larvae collected at two instars, and both black soldier fly larvae and cricket dry powder samples. The figure is an original creation of the authors and has not been published previously.

3. Applications of Vibrational Spectroscopy in Edible Insects

Techniques such as MIR, NIR, and Raman spectroscopy have been evaluated by researchers and industry as effective and practical tools for assessing the chemical composition of edible insects and for quality control during processing. More importantly, these techniques provide rapid and objective measurements of food and feed composition and nutritional value (e.g., protein, moisture, and fat content). In addition to its role in assessing the chemical composition, vibrational spectroscopy has also been evaluated for detecting adulteration, identifying and quantifying the presence of unwanted ingredients, such as plant proteins in insect powders, and detecting the addition of insect meal to different food products. In addition to chemical composition, both authenticity and traceability are important to the consumer from a safety point of view. In addition, the identification of insect species has also been of interest, where different vibrational spectroscopy techniques have been evaluated for their ability to identify insect species, as well as the presence of insect parts in mixed products [36,37].

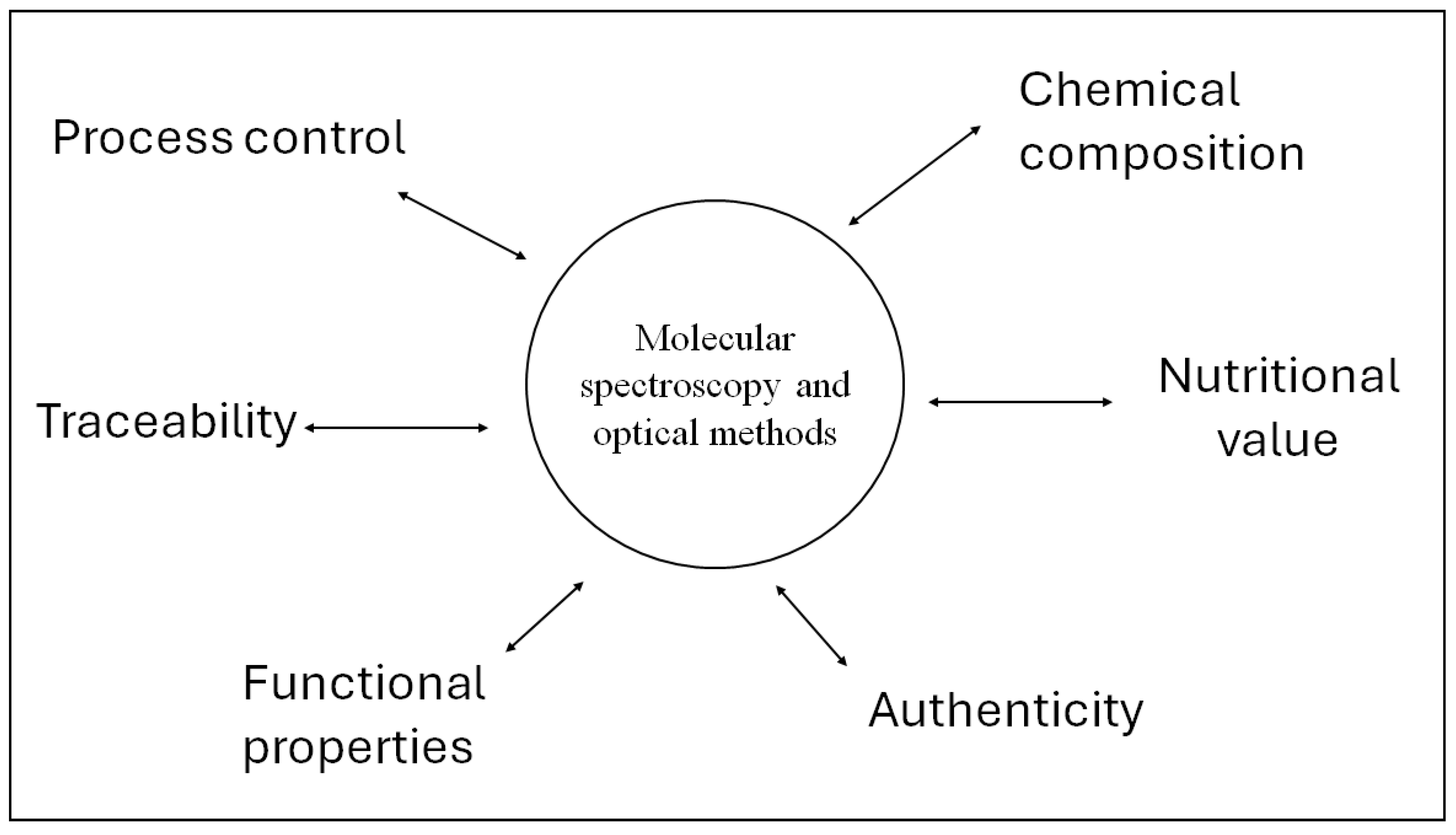

A recent area of interest in the application of these analytical techniques is associated with the ability of these techniques to be used for monitoring different processing parameters [38,39]. Process monitoring or process analytical technologies (PAT) can be incorporated into the production line for the online analysis of insect larvae, enabling producers to monitor and optimise rearing conditions and composition [38,39]. Figure 2 schematically summarises the different applications of vibrational spectroscopy in the edible insect’s feed and food industries.

Figure 2.

Applications of vibrational spectroscopy in the edible insect’s feed and food industries.

3.1. Authentication and Traceability

NIR and MIR spectroscopy were used to evaluate the level of adulteration of A. domesticus, cricket powder (CPF) added to chickpea (CKF), and flaxseed meal flours (FxMF) [36]. In this study, mixture samples were analysed using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) MIR and Fourier transform (FT) NIR combined with partial least squares (PLS) using cross-validation. The coefficient of determination in cross validation (R2CV) and the standard error in cross-validation (SECV) reported ranged from 0.91 to 0.94 and from 4.33% to 6.68%, respectively, for ALL, CPF vs. CKF, and FxMF vs. CKF samples analysed using MIR spectroscopy. The R2CV and SECV ranged between 0.94 and 0.98 and 1.74% to 3.27%, using all of the CPF vs. CKF mixture, and the FxMF vs. CKF samples, as analysed by NIR [36]. The authors showed that the different mixtures differed in absorbance at specific wavelengths in the NIR range. It was concluded that these wavelengths can be utilised to assess the presence of cricket flour in the mixtures [36].

FT-NIR imaging was evaluated to detect and quantify the presence of edible insects in feed meal (e.g., generic vegetal feed meals, poultry, bovine, fish, and krill meals) [40]. Discriminant analysis (DA) was utilised to identify the presence of insect fragments in the feed meal samples. Moreover, the possibility of quantifying the insect’s meal in the feed sample was also successfully tested [40]. The authors concluded that FT-NIR imaging can be used as a screening tool for quality assurance [40].

Edible insect powders from different species (Tenebrio molitor, Alphitobius diaperinus, Gryllodes sigillatus, A. domesticus, and Locusta migratoria) and origins (The Netherlands and New Zealand) were analysed using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) combined with FTMIR spectroscopy and classified using soft independent modelling of class analogy (SIMCA) [37]. The SIMCA classification models identified both the insect species and their origin. The classification models were based on the patterns associated with their lipids and chitin. Most models correctly classified the samples (100%), except for A. diaperinus [37]. Other authors have also reported good classification rates to detect the presence of insects in feed meal samples using either NIR spectroscopy [41] or ATR-MIR spectroscopy [42].

The ability of ATR-FTMIR spectroscopy to discriminate between doughs and 3D-printed baked snacks made with A. diaperinus and L. migratoria flour was evaluated [43]. Doughs were made with different amounts of insect flour (0–13.9%) replacing the same amount of chickpea flour (46–32%). In this study, SIMCA models correctly classified the species of edible insects added and used to prepare the doughs and snacks. The discrimination power of the models was associated with wavelengths linked to lipid, protein, and chitin contents in the insects [43]. Furthermore, the classification models were able to predict the percentage of insect flour added to the dough and snacks, with coefficients of determination ranging from 0.97 to 0.99 and a standard error of prediction (SEP) ranging from 1.08 to 1.90% [43].

3.2. Chemical and Nutritional Fingerprints

The ability of fluorescence spectroscopy to analyse 15 insect powders from five Orthoptera species (A. domesticus, Gryllus assimilis, Gryllus bimaculatus, L. migratoria, Schistocerca gregaria) and three origins was evaluated [44]. The fluorescence data were analysed using the averaged dataset via Parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC). The models were validated for five components, each with distinct fluorescence peaks. Results from the application of PARAFAC suggested that edible insects’ fluorescence information arises from mixtures of amino acids and other chemical compounds such as tryptophan plus tyrosine (PARAFAC component-1), tryptophan plus tyrosine and tocopherol (PARAFAC component-2), and collagen plus pyridoxine and pterins (PARAFAC component-3) [44].

The ability of ATR-FTMIR spectroscopy was used to collect and characterise the fingerprint of BSFL, Tenebrio molitor, G. bimaculatus, and A. domesticus samples [45]. Specific wavenumbers in the MIR range were reported corresponding with Amide groups present in the samples, associated with the secondary structure of protein [45]. This study showed that the MIR spectra of the insects are associated with rearing conditions and substrates used to feed the different species [45].

3.3. Proximate Composition, Amino Acids, and Fatty Acids

The prediction of the proximate composition (e.g., protein, fat, dry matter, ash) of edible insects using NIR, MIR, and HSI has been reported by different authors [46,47,48,49]. The prediction of crude protein (CP) and total lipids (TP) was reported using BSFL (Hermetia illucens) flour, where residual predictive deviation (RPD = SD/SECV) values ranged between 2.5 and 4.3, and root mean square standard error of prediction (RMSEP) between 1.9% to 3.5% depending on the algorithm used to develop the calibration models [48]. A R2CV of 0.90 and RPD value of 3.6 for the acid detergent fibre (ADF) and a R2CV of 0.76 and a RPD value of 2.1 for total carbon (TC), CP (R2CV of 0.63; RPD value of 1.4), crude fat (CF) (R2CV of 0.70; RPD value of 1.6), neutral detergent fibre (NDF) (R2CV of 0.60; RPD value of 1.6), starch (R2CV of 0.52; RPD value of 1.4), and sugars (R2CV of 0.52; RPD value of 1.4) were reported by Alagappan and collaborators [46]. The prediction of proximate composition was also attempted using HSI, where the RMSEP values ranged between 1.57 and 1.66% and RPD values ranged between 2.0 and 2.5 for the prediction of CP (% protein range 25.5 to 43.5%) [47]. Short wavelengths in the NIR (short wavelength—SWIR) combined with HSI were used to predict the proximate composition of dried BSFL [49]. The PLS regression algorithm was used to develop calibration models for moisture, CP, CF, crude fibre, and ash content with R2CV values > 0.89 and RMSEP values within 2% [49]. CF was predicted in partially defatted edible T. molitor and A. diaperinus powders using MIR (4000–630 cm−1) and NIR (1350–2550 nm) spectroscopy [50]. The R2CV was higher than 0.9 and low SECV ranging between 1.06 and 3.22% using PLS regression [51,52]. Overall, studies reported using both NIR spectroscopy and HSI demonstrated that these techniques were able to predict the proximate composition of edible insects successfully.

The prediction of amino acids and fatty acids in T. molitor was reported using FTNIR spectroscopy (1100–2100 nm) [53,54]. The R2CV and R2 in predictions (R2Pred) were higher than 0.82 and higher than 0.86, with RPD values higher than 2.20 for 10 amino acids [53,54]. The PLS regression models developed for the prediction of glutamic acid, leucine, lysine, and valine were not adequate for the prediction of these amino acids [40,41]. The prediction of six fatty acids was also possible with R2CV and R2Pred values higher than 0.77 and higher than 0.66, with RPD values higher than 1.73 [53,54].

The ability of ATR-MIR spectroscopy to predict fatty acids in adult A. domesticus, G. bimaculatus, T. molitor, and Rhynchophorus ferrugineus samples was reported [55]. In this study, freeze-dried insects were analysed using ATR-MIR spectroscopy [55]. The MIR spectra collected was able to provide information about the biochemical properties of the samples. The R. ferrugineus samples showed the highest lipid content and the lowest protein content [55]. Furthermore, unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) were also analysed, where the highest content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), along with the lowest content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), was observed in the larvae of the R. ferrugineus species [55], once more highlighting the versatility and ability of IR technology to predict more complex chemical compounds in insects [55].

In recent years, miniaturised and handheld MIR and NIR instruments have been evaluated to assess the composition and classify edible insect powders [25,28,50,52]. Different NIR portable instruments were compared for the classification of edible insect powders, independent of their origin or grinding degree [56]. The prediction of CP, lipids, and moisture was reported using NIR spectroscopy, which yielded R2CV values greater than 0.95 [50,52]. In addition, NIR microscopy was used to differentiate between insect and plant products and to detect insect meal at low inclusion rates in feed [50,52].

Binary mixtures of T. molitor, A. diaperinus, A. domesticus, and L. migratoria from 0 to 100% in increment of 10%, and mixtures of three insect species (T. molitor, A. diaperinus, A. domesticus) were added to organic wheat, whole wheat, and chickpea flour with an increasing ratio of 10% from 0 to 100% [56]. The authors evaluated different handheld instruments where instrument-to-instrument variation was evaluated. The authors evaluated 13 instruments to analyse 16 samples, where an external validation set in one additional device was used (n: 53) [56]. The PLS regression models showed good linearity, predicting CP and CF in mixtures of insect powders and flour, and in insect powder mixtures, with strong R2CV higher than 0.97, low RMSECV (range between 0.2 and 2.1%), and RMSEP greater than 0.5% [56]. This research showed that using multiple instruments increased the model’s error but resulted in a more generalizable model with reduced instrument-to-instrument variability when predicting properties with a new device [56].

Hyperspectral imaging was used to identify spectral patterns associated with different molecular components, including total fat and moisture in edible insects [57]. In this study, a hyperspectral image system in the wavelength range between 400 and 1000 nm was used to analyse BSFL meal samples [57]. In this study, the results were compared to those obtained using wheat flour samples where BSFL meal samples indicated 7.2% ± 0.05% (w/w) and 28.15% ± 0.15% (w/w) in moisture and total fat content, respectively [57]. Compared with wheat flour, the BSFL meal samples where these differences were clearly identified using the hyperspectral images have less fat, which underscores the efficiency and utility of multispectral cameras to conduct real-time and non-destructive analyses [57].

4. Conclusions

Reports on the use of vibrational spectroscopy techniques (e.g., NIR and MIR spectroscopy) demonstrate that they could play an essential role in the edible insects’ industry. The spectra collected provide with accurate information about the chemical characteristics and nutritional value of the different species of edible insects. Additionally, the spectra or images can be used to authenticate and trace contamination between species when other protein-based alternatives are used. In all cases, vibrational spectroscopy techniques (e.g., NIR, MIR, Raman spectroscopy, or HSI) require combination with ML or chemometrics, and pre-processing techniques. With few exceptions, the scientific literature has reported examples of feasibility or potential studies in which small datasets have been used to represent a wide range of conditions.

While calibration development (e.g., quantitative analysis) has been the primary objective of these applications, less emphasis has been placed on interpreting the spectra or images (e.g., raw data, loadings, pixels). Technological and scientific challenges associated with data interpretation in the context of biology and physiology (e.g., larvae, pupae, instar, adult), rearing conditions, and the nutrition of the samples remain barriers to future applications in the edible insect industry. In addition, regulatory compliance, the integration of predictive models into existing analytical frameworks, the need for a user-friendly interface, data security and privacy issues, and their integration into ethical and welfare guidelines and legislation have not been fully addressed by the industry.

Consequently, protocols addressing these issues must be developed in collaboration with the user to ensure that the benefits of advanced data analysis are aligned with the practicality and the specific requirements imposed by the end-user. Developing guidelines and international collaboration to build large, robust datasets will be required to enable the use of models in routine conditions. Furthermore, training employees (e.g., industry, technicians, researchers, and end-users) will be necessary to ensure the smooth applicability and interpretability of these tools in routine food analysis.

Author Contributions

S.A., S.D.L.-C., C.M.S. and L.C.H., writing—review and editing; D.C., conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Van Huis, A. Insects as food and feed, a new emerging agricultural sector: A review. J. Insects Food Feed. 2020, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A.; Rumpold, B.; Maya, C.; Roos, N. Nutritional qualities and enhancement of edible insects. Annu. Rev. Nut. 2021, 41, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Seijas, N.; Fernandes, H.; López-Periago, J.E.; Outeirino, D.; Morán-Aguilar, M.G.; Domínguez, J.M.; Salgado, J.M. Characterization of all life stages of Tenebrio molitor: Envisioning innovative applications for this edible insect. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Potential and challenges of insects as an innovative source for food and feed production. Innov. Food Sci. Emer. Technol. 2013, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mao, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Fang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; et al. Edible Insects: A New Sustainable Nutritional Resource Worth Promoting. Foods 2023, 12, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Shelomi, M. Review of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) as Animal Feed and Human Food. Foods 2017, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Fonseca, K.Y.; Barragán-Fonseca, K.B.; Verschoor, G.; van Loon, J.J.; Dicke, M. Insects for peace. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 40, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barragan-Fonseca, K.B.; Dicke, M.; van Loon, J.J. Nutritional value of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) and its suitability as animal feed–a review. J. Insects Food Feed 2017, 3, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, B.; Shi, J.; He, S.; Dai, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, D.; Li, J. Black soldier fly larvae as a novel protein feed resource promoting circular economy in agriculture. Insects 2025, 16, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macwan, S.S.; de Souza, T.P.; Dunshea, F.R.; DiGiacomo, K.; Suleria, H.A.R. Black soldier fly larvae (Hermetica illucens) as a sustainable source of nutritive and bioactive compounds, and their consumption challenges. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2024, 64, AN23192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Fonseca, K.B. BioInsectonomy: A circular agrifood economy based on insects as animal feed. In The Circular Bioeconomy in Industry: Strategies for Sustainable Resource Recovery, Environmental Balance, and Ecosystem Protection; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Alagappan, S.; Rowland, D.; Barwell, R.; Mantilla, S.; Mikkelsen, D.; James, P.; Yarger, O.; Hoffman, L.C. Legislative landscape of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) as feed. J. Insects Food Feed 2022, 8, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.; Abdel-Wareth, A.A.A.; Hiramatsu, K.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Luza, D.; Lohakare, J. Flight toward sustainability in poultry nutrition with black soldier fly larvae. Animals 2024, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuch, B.; Barszcz, M.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D. The potential of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae in chicken and swine nutrition. A review. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2024, 33, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestingi, A. Alternative and sustainable protein sources in pig diet: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, E.P.; Cox, J.R.; Wickersham, T.A.; Drewery, M.L. Evaluation of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) as a protein supplement for beef steers consuming low-quality forage. Trans. Anim Sci. 2022, 6, txac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogevik, A.S.; Hanson, E.; Samuelsen, T.A.; Kousoulaki, K. Black soldier fly larvae meals with and without stick water highly utilized in freshwater by Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Parr. Aquac. Nut. 2025, 1, 8827164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Qi, C.; Tang, J.; Ye, T.; Lou, B.; Huang, F. Fattening by dietary replacement with fly maggot larvae (Musca domestica) enhances the edible yield, antioxidant capability, nutritional and taste quality of adult Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Foods 2025, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.K.; Deepti, M.; Patel, A.B.; Kumar, P.; Angom, J.; Debbarma, S.; Singh, S.K.; Deb, S.; Lal, J.; Vaishnav, A.; et al. Dissecting insects as sustainable protein bioresource in fish feed for aquaculture sustainability. Dis. Food 2025, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoe, E.A.; Fagariba, C.J.; Kaburi, S.A.; Chidozie Ogwu, M. Nutritional Composition of Edible Insects. In Edible Insects: Nutritional Benefits, Culinary Innovations and Sustainability; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Marimuthu, S.B.; Meijer, N. Regulations on insects as food and feed: A global comparison. J. Insects Food Feed 2021, 7, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, N.; Safitri, R.A.; Tao, W.; Hil, E.F.H.V.-d. European Union legislation and regulatory framework for edible insect production–Safety issues. Animal 2025, 19, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.-H.; Liu, D.; Cheng, J.-H.; Sun, D.-W.; Ma, J.; Pu, H.; Zeng, X.-A. Applications of near-infrared spectroscopy in food safety evaluation and control: A review of recent research advances. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nut. 2015, 55, 1939–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, T.P.; Engelsen, S.B. Why nothing beats NIRS technology: The green analytical choice for the future sustainable food production. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 325, 125028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorak, D.; Herberholz, L.; Iwascek, S.; Altinpinar, S.; Pfeifer, F.; Siesler, H.W. New developments and applications of handheld Raman, mid-infrared, and near-infrared spectrometers. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2012, 47, 83–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowen, A.A.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Cullen, P.J.; Downey, G.; Frias, J.M. Hyperspectral imaging–an emerging process analytical tool for food quality and safety control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, K.B.; Grabska, J.; Huck, C.W. Review near-infrared spectroscopy in bio-applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beć, K.B.; Grabska, J.; Huck, C.W. Miniaturized NIR spectroscopy in food analysis and quality control: Promises, challenges, and perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy—Its versatility in analytical. Anal. Chem. 2012, 28, 545–562. [Google Scholar]

- Zaukuu, J.-L.Z.; Benes, E.; Bázár, G.; Kovács, Z.; Fodor, M. Agricultural potentials of molecular spectroscopy and advances for food authentication: An overview. Processes 2022, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. Sample presentation, sources of error and future perspectives on the application of vibrational spectroscopy in the wine industry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 95, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. The sample, the spectra and the maths—The critical pillars in the development of robust and sound vibrational spectroscopy applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. The barriers in translating near infrared spectroscopy into the food industry–From research into the application. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westad, F.; Marini, F. Validation of chemometric models: A tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 893, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Dardenne, P.; Flinn, P. Tutorial: Items to be included on a near infrared spectroscopy project. J. Near Infrared Spectros. 2017, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagappan, S.; Ma, S.; Nastasi, J.R.; Hoffman, L.C.; Cozzolino, D. Evaluating the use of vibrational spectroscopy to detect the level of adulteration of cricket powder in plant flours: The effect of the matrix. Sensors 2024, 24, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Carretero, J.; García-Gutiérrez, N.; Ferrando, M.; Güell, C.; García-Gonzalo, D.; De Lamo-Castellví, S. Rapid discrimination and classification of edible insect powders using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy combined with multivariate analysis. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Alamprese, C. Advances in NIR spectroscopy applied to process analytical technology in food industries. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 22, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, F.; Lyndgaard, C.B.; Sørensen, K.M.; Engelsen, S.B. Process analytical technology in the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrile, L.; Fusaro, I.; Amato, G.; Marchis, D.; Martra, G.; Rossi, A.M. Detection of insect’s meal in compound feed by Near Infrared spectral imaging. Food Chem. 2018, 267, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.; Pissard, A.; Vincke, D.; Arnould, Q.; Lecler, B.; Gofflot, S.; Michez, D.; Baeten, V. Contribution of vibrational spectroscopy to the characterisation and detection of insect meal in compound feed. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, M.; D’Addario, A.; D’Archivio, A.A.; Biancolillo, A. Future foods protection: Supervised chemometric approaches for the determination of adulterated insects’ flours for human consumption by means of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Microchem. J. 2022, 183, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, N.; Mellado-Carretero, J.; Bengoa, C.; Salvador, A.; Sanz, T.; Wang, J.; Ferrando, M.; Güell, C.; Lamo-Castellví, S. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy combined with multivariate analysis successfully discriminates raw doughs and baked 3d-printed snacks enriched with edible insect powder. Foods 2021, 10, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.; Durek, J.; Ojha, S.; Schlüter, O.K. Fluorescence-based characterisation of selected edible insect species: Excitation emission matrix (EEM) and parallel factor (PARAFAC) analysis. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, K.; Ortuño, J.; Stratakos, A.; Stergiadis, S.; Theodoridou, K. Attenuated-total-reflection Fourier-transformed spectroscopy as a rapid tool to reveal the molecular structure of insect powders as ingredients for animal feeds. J. Insects Food Feed 2024, 10, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagappan, S.; Hoffman, L.; Mikkelsen, D.; Mantilla, S.O.; James, P.; Yarger, O.; Cozzolino, D. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for monitoring the nutritional composition of black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) and frass. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Tirado, J.P.; Amigo, J.M.; Barbin, D.F. Determination of protein content in single black fly soldier (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae by near infrared hyperspectral imaging (NIR-HSI) and chemometrics. Food Control 2023, 143, 109266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Tirado, J.P.; Vieira, M.S.; Amigo, J.M.; Siche, R.; Barbin, D.F. Prediction of protein and lipid content in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae flour using portable NIR spectrometers and chemometrics. Food Control 2023, 153, 109969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kurniawan, H.; Akbar, F.M.; Hoonsoo, K.L.; Sung, K.M.; Insuck, B.; Byoung-Kwan, C. proximate content monitoring of black soldier fly larval (Hermetia illucens) dry matter for feed material using short-wave infrared hyperspectral imaging. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2023, 43, 1150–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez-Sanchez, C.; Ranasinghe, M.K.; Güell, C.; Ferrando, M.; Domingo, J.S.; Castellvi, S.d.L. Miniaturized NIR and MIR spectroscopy for insect lipid characterization. J. Insects Food Feed 2025, 11, 2393–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lamo Castellvi, S.; Mendez, C.; Matos, C.; Wu, Y.; Plans, M.; Rodriguez-Saona, L. FT-NIR spectroscopy for protein and lipid analysis in insect powders and flour mixtures: A cross-instrument calibration approach. Microchem. J. 2025, 218, 115315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Sanchez, C.; Güell, M.C.; Ferrando, M.; Rodriguez-Saona, L.; Jimenez-Flores, R.; Domingo, J.C.; de Lamo Castellvi, S. Prediction of fat content in edible insect powders using handheld FT-IR spectroscopic devices. LWT 2024, 207, 116652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröncke, N.; Wittke, S.; Steinmann, N.; Benning, R. Analysis of the Composition of Different Instars of Tenebrio molitor Larvae using Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy for Prediction of Amino and Fatty Acid Content. Insects 2023, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröncke, N.; Benning, R. Determination of moisture and protein content in living mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor L.) using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS). Insects 2022, 13, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkusz, A.; Dymińska, L.; Banaś, K.; Harasym, J. Chemical and Nutritional Fat Profile of Acheta domesticus, Gryllus bimaculatus, Tenebrio molitor and Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Foods 2024, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riu, J.; Vega, A.; Boqué, R.; Giussani, B. Exploring the analytical complexities in insect powder analysis using miniaturized NIR spectroscopy. Foods 2022, 11, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.M.O.d.; Fidalgo, L.G.; Inácio, R.; Fantatto, R.; Carvalho, M.J.; Murta, D.; Pereira, N. First insights into macromolecular components analyses of an insect meal using hyperspectral imaging. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).