Intelligent Early Warning and Sustainable Engineering Prevention for Coal Mine Shaft Rupture

Abstract

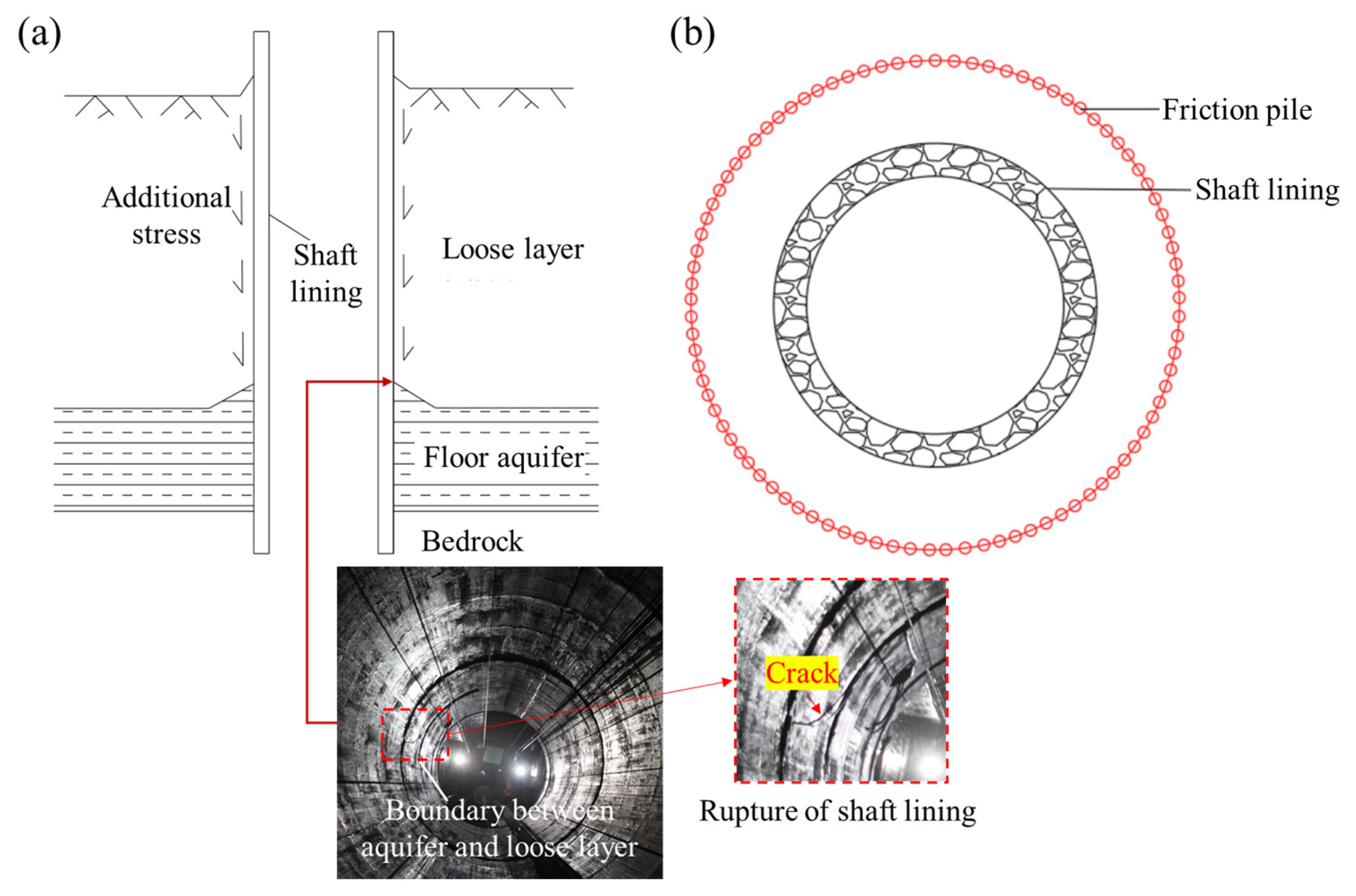

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Algorithms

2.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.2. Theoretical Basis and Discriminant Procedure of Stepwise Discriminant Analysis (SDA)

2.3. Fisher’s Discriminant Analysis (FDA)

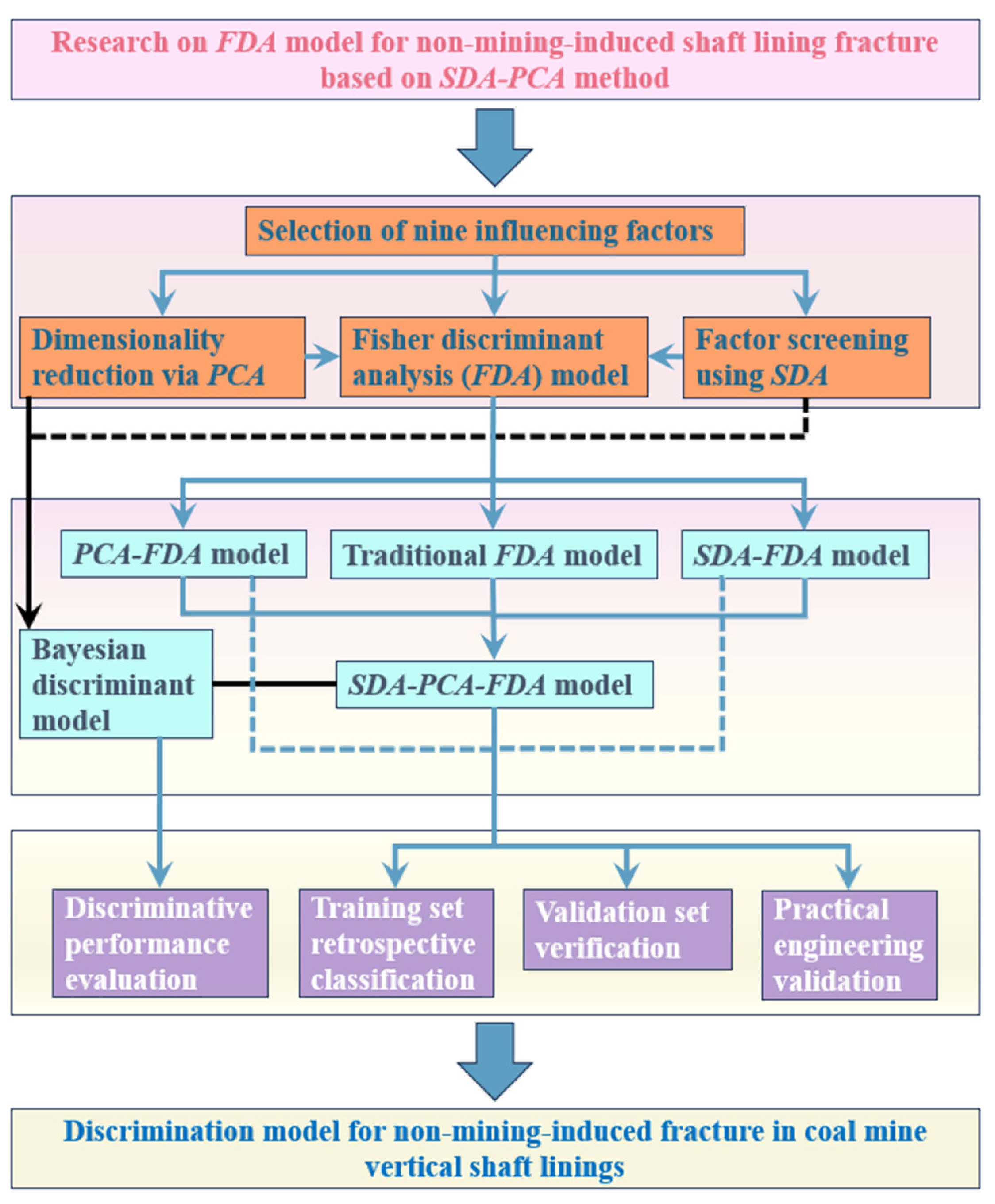

3. Discriminant Analysis Model for Shaft Rupture

3.1. Selection of Discriminant Indicators

3.2. Model Establishment

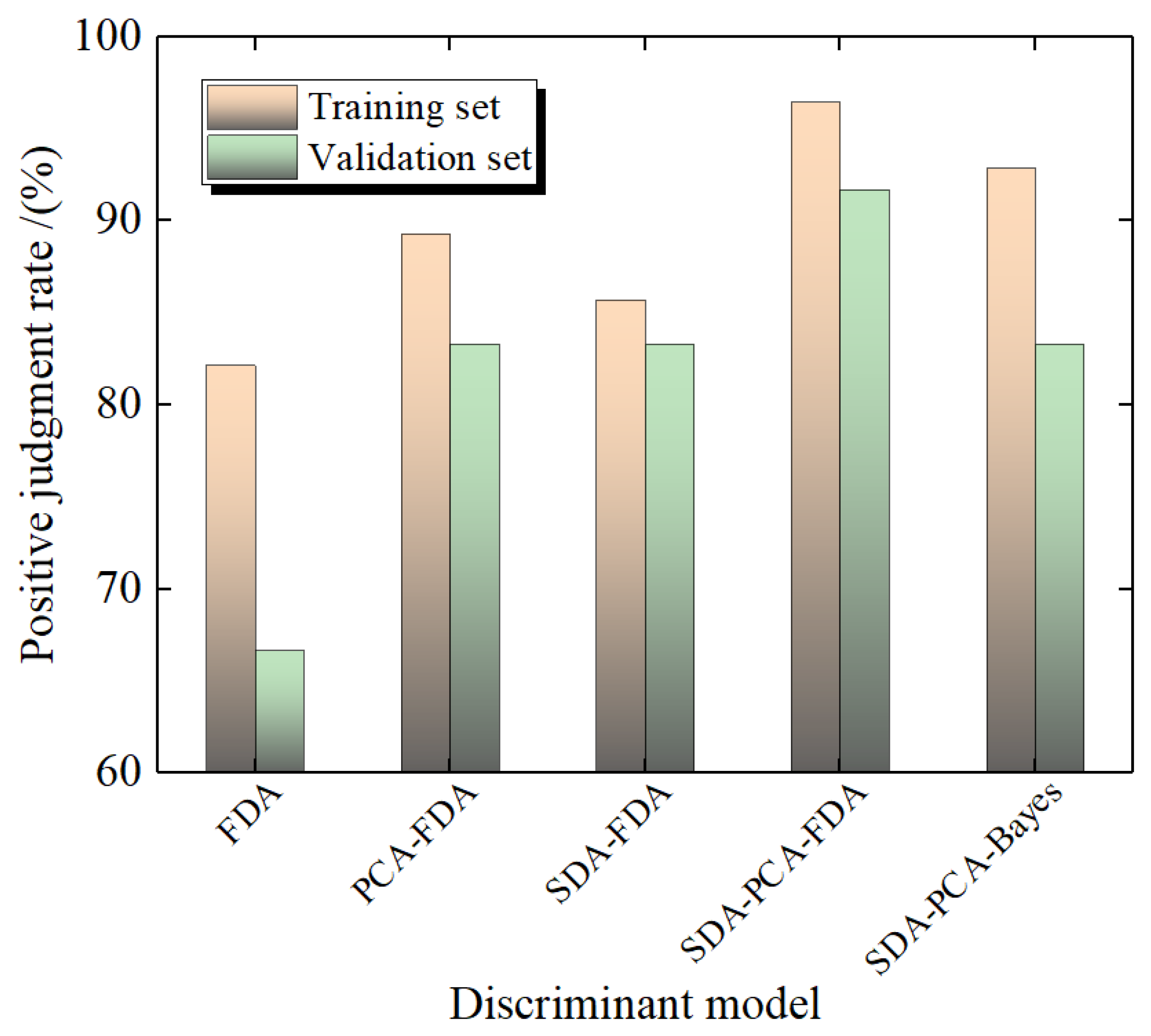

3.3. Validation of Discriminant Effectiveness

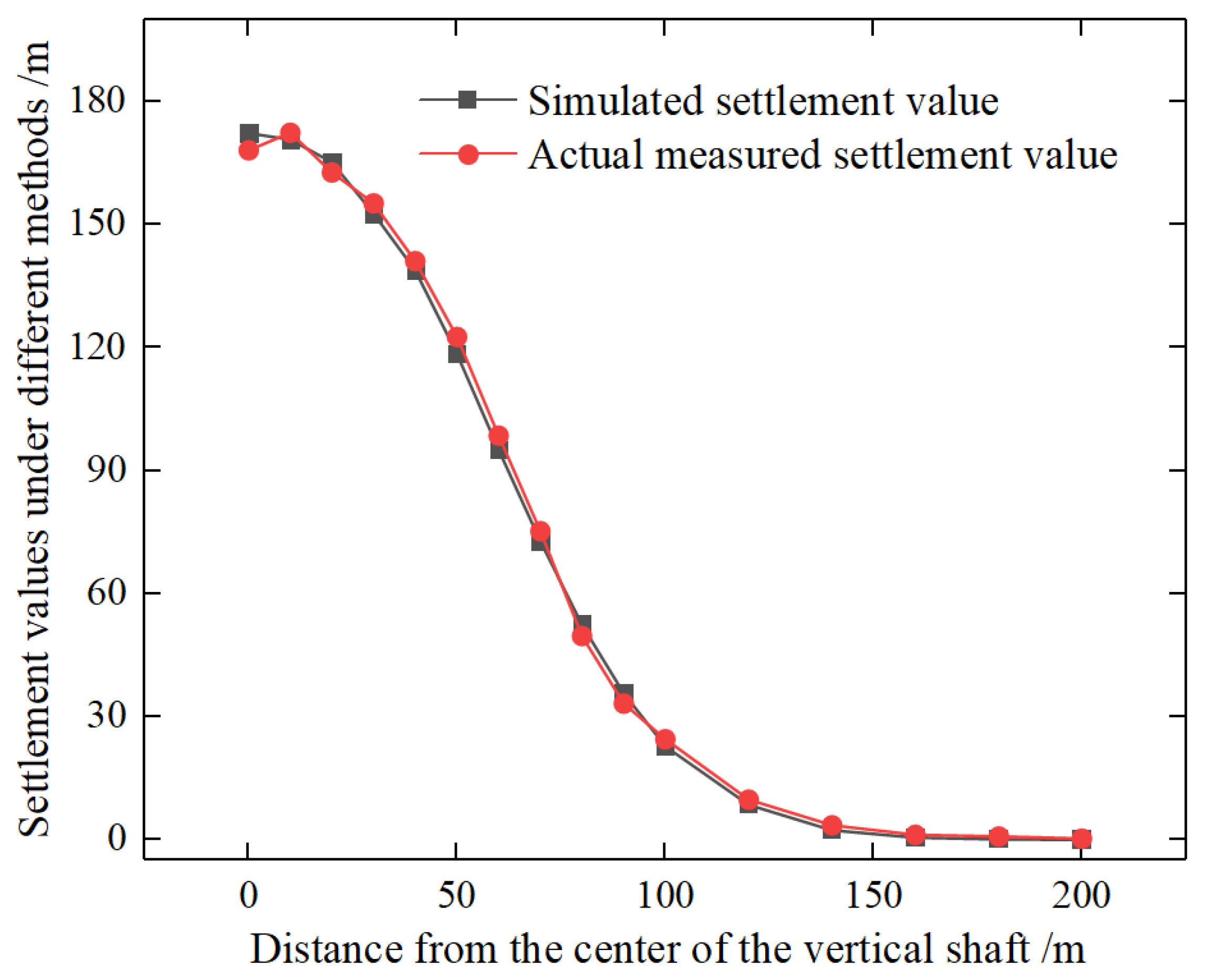

4. Engineering Prediction

5. Sustainable Governance Application

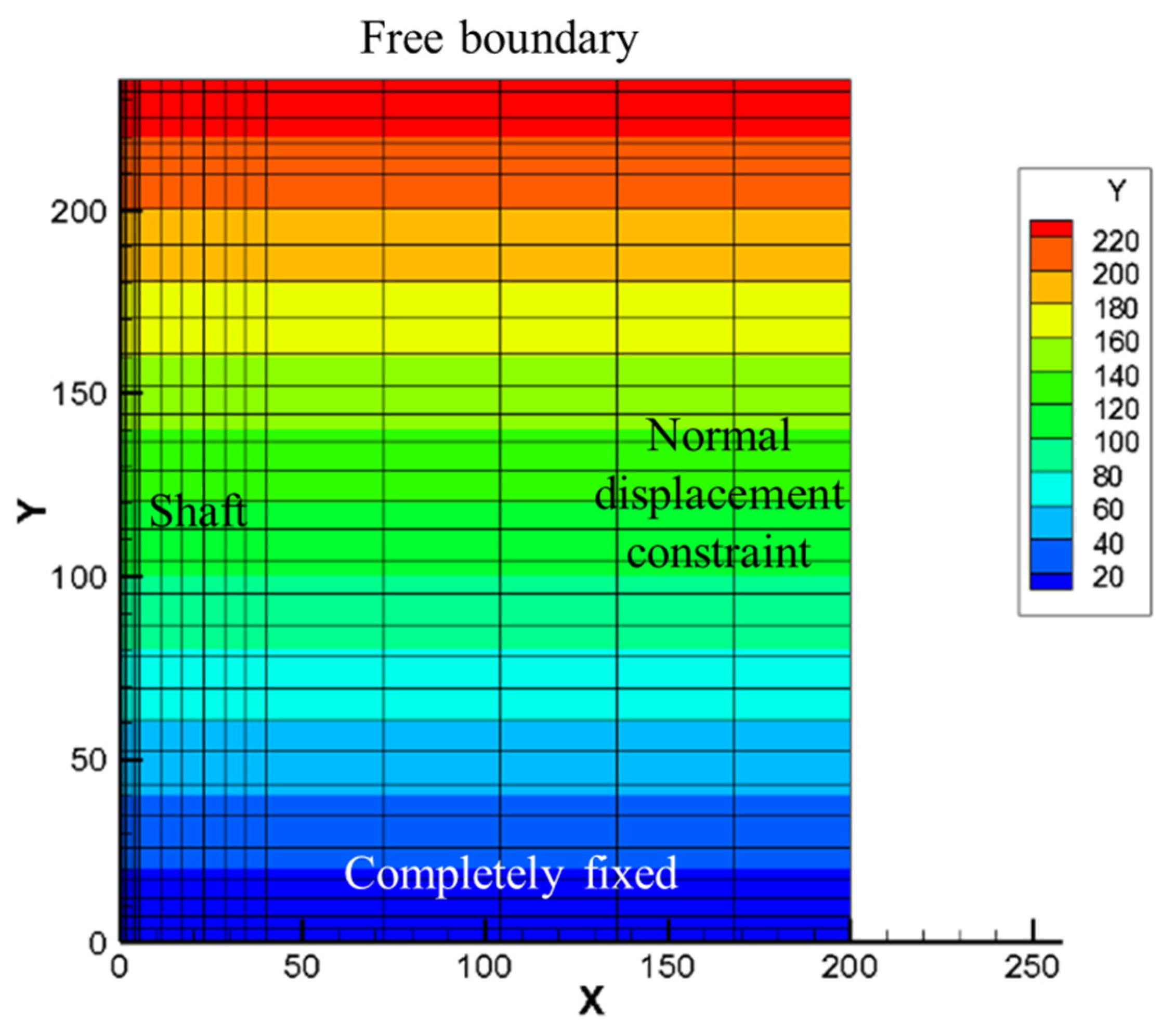

5.1. Determination of Friction Pile Parameters via Numerical Simulation

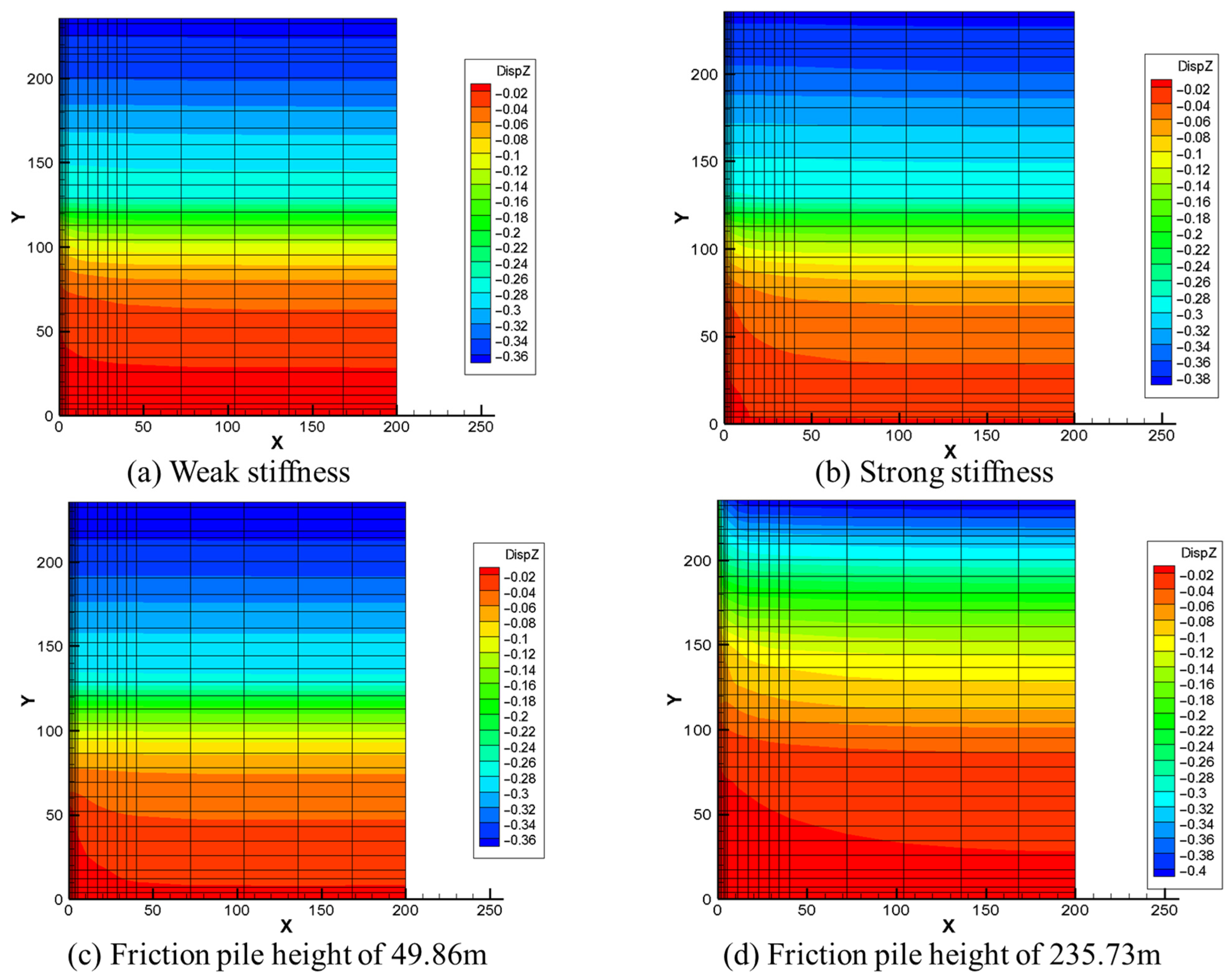

5.1.1. Friction Pile Stiffness and Height

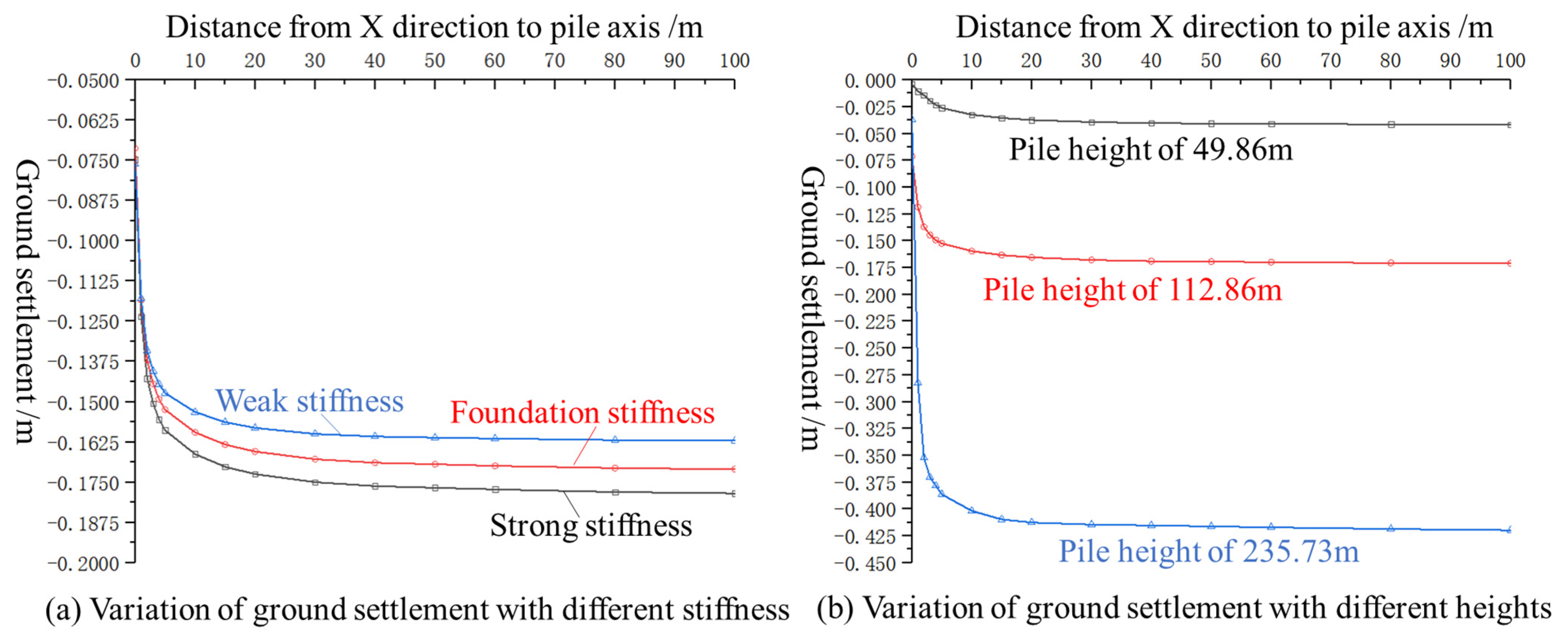

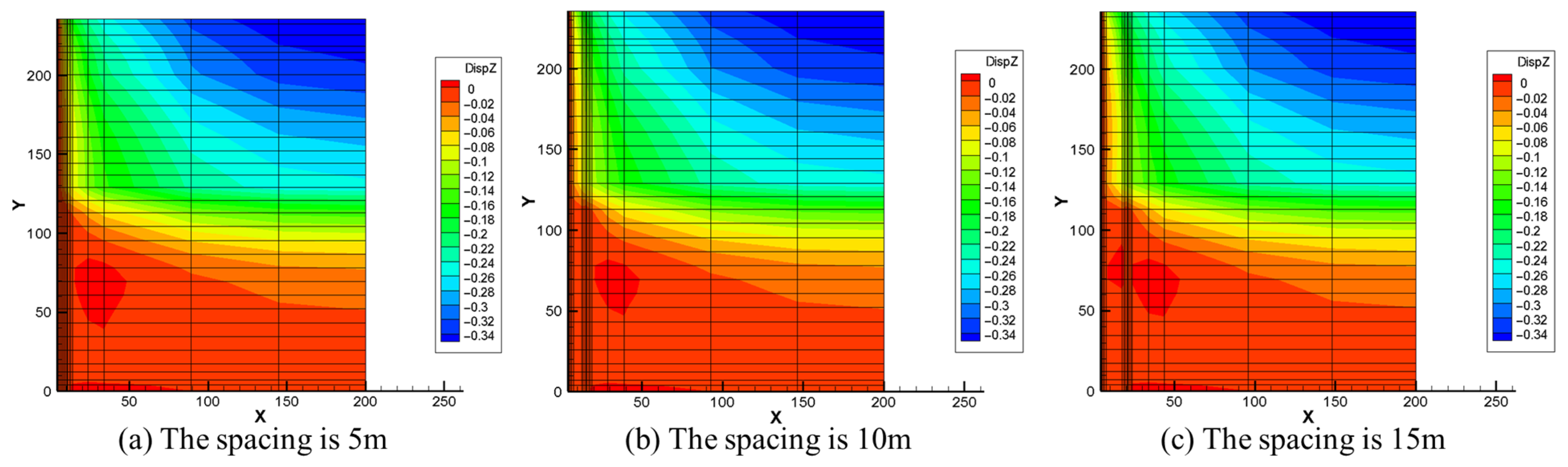

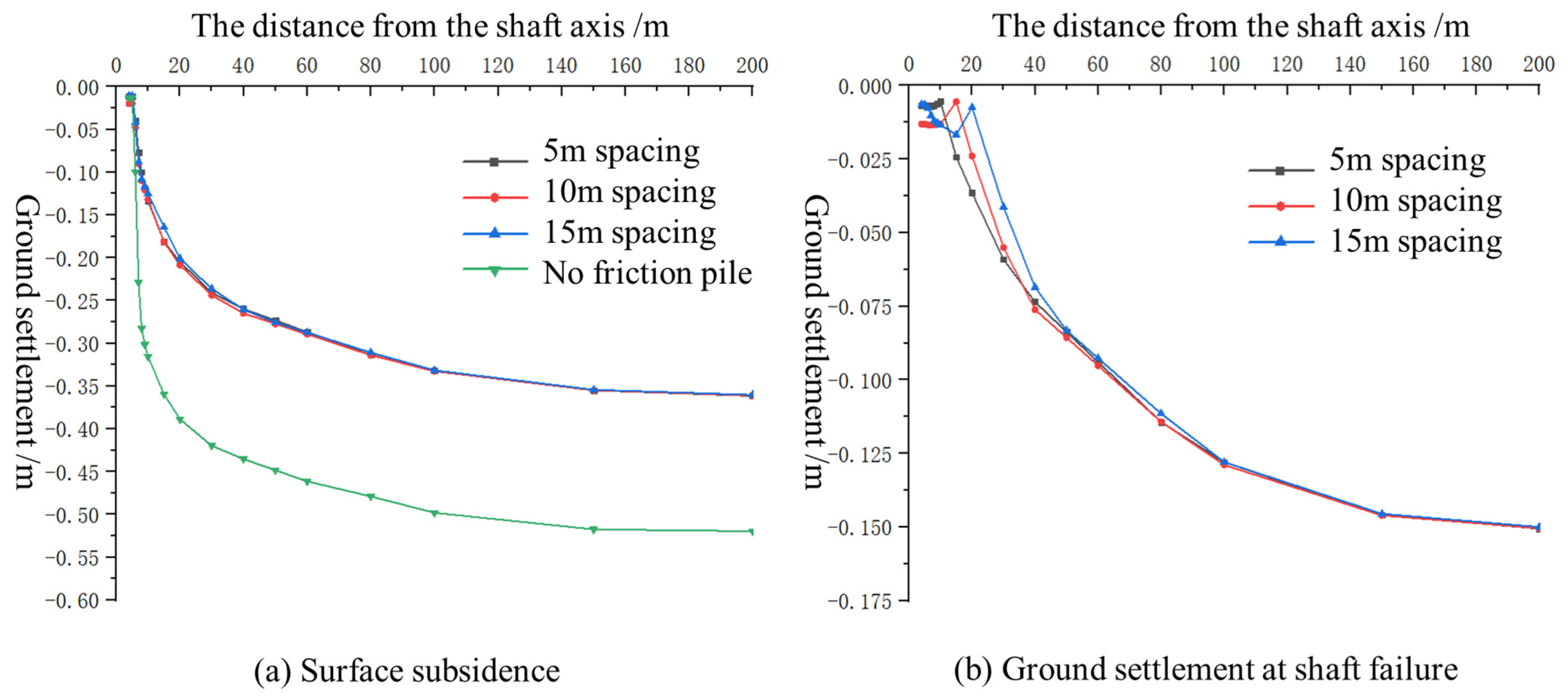

5.1.2. Friction Pile to Shaft Wall Spacing

5.2. Comparative Analysis of Governance Scheme Sustainability

- (1)

- Scheme 1: Chemical grouting after wall penetration within the 213 m to 230 m depth range, combined with creating a relief groove at 223 m depth.

- (2)

- Scheme 2: Cement grouting after wall penetration within the 213 m to 230 m depth range, combined with creating a relief groove at 223 m depth.

- (3)

- Scheme 3: Shaft ring reinforcement within the 213 m to 230 m depth range, combined with creating a relief groove at 223 m depth.

- (4)

- Scheme 4: Ground grouting to reinforce the unconsolidated strata, combined with shaft ring reinforcement.

- (5)

- Scheme 5: Implementation of the friction pile method at a horizontal distance of 10 m from the shaft wall.

5.2.1. Economic Budget Analysis

5.2.2. Analysis of Scheme Advantages and Disadvantages

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, B.; Wang, J. Study on Unfrostered Water Content and Strength Characteristics of Saturated Sandstone During Thawing Process. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Wang, B. Deformation and Instability Mechanisms of a Shaft and Roadway Under the Influence of Rock Mass Subsidence. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; He, H.; Liu, Z.; He, X.; Zhou, F.; Song, Z.; Yang, D. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Microseismic Monitoring Data in Deep Mining Based on ST-DBSCAN Clustering Algorithm. Processes 2025, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, W. Research on Coupling Adsorption Experiments for Wall–Climbing Robots in Coal Mine Shafts. Processes 2023, 11, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Yu, S. Analysis of Rock Mass Energy Characteristics and Induced Disasters Considering the Blasting Superposition Effect. Processes 2024, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, F.; Shi, Z.; Liang, M.; Song, Y. Research and Application of Multi-Mode Joint Monitoring System for Shaft Wall Deformation. Sensors 2022, 22, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Cheng, H.; Rong, C.; Li, M.; Cai, H.; Song, J. Analysis and Prediction of Vertical Shaft Freezing Pressure in Deep Alluvium Based on RBF Fuzzy Neural Network Model. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2016, 33, 70–76+82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, M.; Duan, H.; Zhang, L. A Model of Fisher’s Discriminant Analysis for Evaluating Non-Mining-Induced Fracture. China Coal. 2017, 43, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zhang, Y. Forecast for Non-Mining Fracture of Shaft-Lining of Mine. J. China Coal Soc. 2009, 34, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Li, X. A Distance Discriminant Analysis Method of Forecast for Shaft-Lining Non-Mining Fracture of Mine. J. China Coal Soc. 2007, 32, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, G.; Liu, N.; Fan, X. Forecast Model of GA-SVM for Shaft-Lining Non-Mining Fracture. J. China Coal Soc. 2011, 36, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Shao, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, W.; Wu, X. Evaluation on the Stability of Vertical Mine Shafts Below Thick Loose Strata Based on the Comprehensive Weight Method and a Fuzzy Matter-Element Analysis Model. Geofluids 2019, 1, 3543957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Sheng, K. Research on the Technology of Plugging Gushing Water in the Vertical Shaft Under Complicated Conditions. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 6654987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, E. The indoor experimental method for the microseismic issue of freezing pipe fracture and its effectiveness verification. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wang, C.; Xue, W.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Y. Experimental study on the dynamic mechanical properties of high-performance hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete of mine shaft lining. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Ding, H.; Gao, W.; Zhang, S. Theoretical prediction of high-risk zone for early temperature cracks in well walls in deep-frozen shafts. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2023, 93, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Han, T. Vertical Additional Force and Structure of Shaft Lining in Thick Aeolian Sand Strata. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2016, 33, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Rong, C.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Tang, B.; Li, X. Mechanical Properties of High-Strength High-Performance Reinforced Concrete Shaft Lining Structures in Deep Freezing Wells. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 2430652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z. Distribution Characteristics of the Additional Vertical Stress on a Shaft Wall in Thick and Deep Alluvium: A Simulation Analysis. Nat. Hazards 2019, 96, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, S.; Dong, X. Shaft Failure Characteristics and the Control Effects of Backfill Body Compression Ratio at Ultra-Contiguous Coal Seams Mining. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Sheng, Y.; Cao, W.; Ning, Z.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y. Thermal Stability Prediction of Frozen Rocks Under Fluctuant Airflow Temperature in a Vertical Shaft Based on Finite Difference and Finite Element Methods. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 52, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Chen, C.; Xia, K.; Chen, L.; Fu, H.; Deng, Y.; Du, G. Research on Deformation Mechanism and Feasibility of Continuous Use of Mine Shaft. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38 (Suppl. S1), 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, W.; Yu, X. Early Age Cracking Potential of Inner Lining of Coal Mine Frozen Shaft. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Wang, W. Deformation Monitoring and Stability Analysis of Shaft Lining in Weakly Cemented Stratum. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 8462746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lai, J.; Ren, Z.; Shi, Y.; Kong, X. Failure Mechanical Behaviors and Prevention Methods of Shaft Lining in China. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 143, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Martens, M.P.; Wiedermann, W. Conditional Direction of Dependence Modeling: Application and Implementation in SPSS. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 41, 1252–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Mao, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C. Macro-and Meso-Scale Study on Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Shaft Lining Concrete Exposed to High Water Pressure. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Guo, Q. Research Progress on Mine Shaft Liner Breaking Mechanism and Prevention Technologies in Deep and Thick Overburden. Coal Sci. Technol. 2011, 39, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolfaei, S.; Lakirouhani, A. Sensitivity Analysis of Effective Parameters in Borehole Failure, Using Neural Network. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4958004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhu, C.; Xiang, B. Fuzzy Theory- and SVM-Based Bayesian Network Assessment Method for Slope Seismic In-Stability Scale. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2019, 38 (Suppl. S1), 2807–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacan, C.Ö.; Goodman, G.V.R. Analyses of geological and hydrodynamic controls on methane emissions experienced in a Lower Kittanning coal mine. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 98, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, G.; Lu, X.; Xu, Z.; Dong, P. Multivariate Nonlinear Model of Blasting Vibration Velocity Attenuation Considering Rock Mass Damage. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 14, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Cao, B.T.; Xu, C.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Meschke, G. Mechanics of longitudinal joints in segmental tunnel linings: Role of connecting bolts. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 161, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Shaft Sample | Influencing Factors | Actual Condition | Discriminant Result | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ1/m | γ2 | γ3/% | γ4/m | γ5/m | γ6/% | γ7 | γ8/% | γ9 | FDA | PCA-FDA | SDA-FDA | SDA-PCA-FDA | SDA-PCA-Bayes | ||

| 01 | 189.3 | 0 | 100 | 6.5 | 18.3 | 25.0 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 02 | 189.5 | 1 | 90 | 5.5 | 17.1 | 20.0 | 3 | 60.0 | 1 | Rupture | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * |

| 03 | 190.4 | 0 | 90 | 7.5 | 22.7 | 20.0 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 04 | 176.5 | 0 | 90 | 5.0 | 18.0 | 12.0 | 3 | 20.0 | 1 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 05 | 185.4 | 1 | 80 | 5.0 | 14.3 | 30.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 06 | 189.3 | 0 | 100 | 6.5 | 14.5 | 28.5 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 07 | 190.4 | 0 | 100 | 7.5 | 16.6 | 23.3 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Rupture | Rupture |

| 08 | 176.5 | 0 | 100 | 5.0 | 7.80 | 15.2 | 3 | 20.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 09 | 184.5 | 1 | 80 | 5.0 | 20.0 | 18.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 10 | 189.3 | 0 | 90 | 6.5 | 9.30 | 10.9 | 1 | 41.6 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 11 | 176.5 | 0 | 13 | 5.0 | 2.90 | 1.30 | 0 | 31.3 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 12 | 189.5 | 1 | 100 | 5.5 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 0 | 49.9 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 13 | 190.4 | 0 | 4 | 7.5 | 3.70 | 1.5 | 0 | 41.6 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 14 | 180.9 | 1 | 100 | 7.5 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 60.0 | 1 | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 15 | 189.3 | 0 | 100 | 6.5 | 11.8 | 13.8 | 1 | 35.8 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 16 | 176.5 | 0 | 57 | 5.0 | 5.10 | 1.5 | 0 | 36.2 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 17 | 189.5 | 1 | 100 | 5.5 | 20.2 | 16.2 | 0 | 35.8 | 0 | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 18 | 190.4 | 0 | 41 | 7.5 | 10.2 | 2.6 | 0 | 35.8 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 19 | 183.5 | 1 | 100 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 2.5 | 1 | 60.0 | 0 | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Rupture * | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Rupture * |

| 20 | 189.5 | 1 | 100 | 5.5 | 26.8 | 19.2 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| Shaft Sample | Influencing Factors | Actual Condition | Discriminant Result | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ1/m | γ2 | γ3/% | γ4/m | γ5/m | γ6/% | γ7 | γ8/% | γ9 | FDA | PCA-FDA | SDA-FDA | SDA-PCA-FDA | SDA-PCA-Bayes | ||

| 01 | 190.4 | 0 | 100 | 7.5 | 13.0 | 6.1 | 0 | 18.2 | 0 | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Non-rupture | Rupture * |

| 02 | 176.4 | 0 | 50 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 3.8 | 0 | 7.3 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 03 | 189.5 | 1 | 100 | 5.5 | 30.2 | 20.5 | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | Rupture | Non-rupture * | Non-rupture * | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 04 | 173.4 | 1 | 100 | 4.5 | 20.0 | 17.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 05 | 176.9 | 1 | 100 | 6.5 | 15.0 | 3.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Rupture * |

| 06 | 157.9 | 1 | 100 | 4.5 | 15.0 | 25.0 | 0 | 20.0 | 0 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 07 | 148.6 | 1 | 100 | 6.5 | 13.5 | 25.0 | 0 | 50.0 | 1 | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| 08 | 190.4 | 0 | 100 | 7.5 | 10.6 | 6.8 | 0 | 18.2 | 0 | Non-rupture | Rupture * | Rupture * | Rupture * | Rupture * | Non-rupture |

| 09 | 176.5 | 0 | 88.8 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 0 | 7.3 | 0 | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture | Non-rupture |

| 10 | 189.3 | 0 | 100 | 6.5 | 18.5 | 17.2 | 1 | 18.2 | 0 | Rupture | Non-rupture * | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture | Rupture |

| Variable | Tolerance | VIF | Dimension | Eigenvalue | Condition Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | - | - | 1 | 6.706 | 1.000 |

| γ2 | 0.249 | 4.008 | 2 | 1.099 | 2.471 |

| γ3 | 0.408 | 2.451 | 3 | 0.527 | 3.569 |

| γ4 | 0.366 | 2.729 | 4 | 0.384 | 4.181 |

| γ5 | 0.269 | 3.720 | 5 | 0.174 | 6.211 |

| γ6 | 0.219 | 4.569 | 6 | 0.061 | 10.490 |

| γ7 | 0.288 | 3.475 | 7 | 0.034 | 13.978 |

| γ8 | 0.235 | 4.257 | 8 | 0.011 | 25.103 |

| γ9 | 0.328 | 3.048 | 9 | 0.006 | 33.940 |

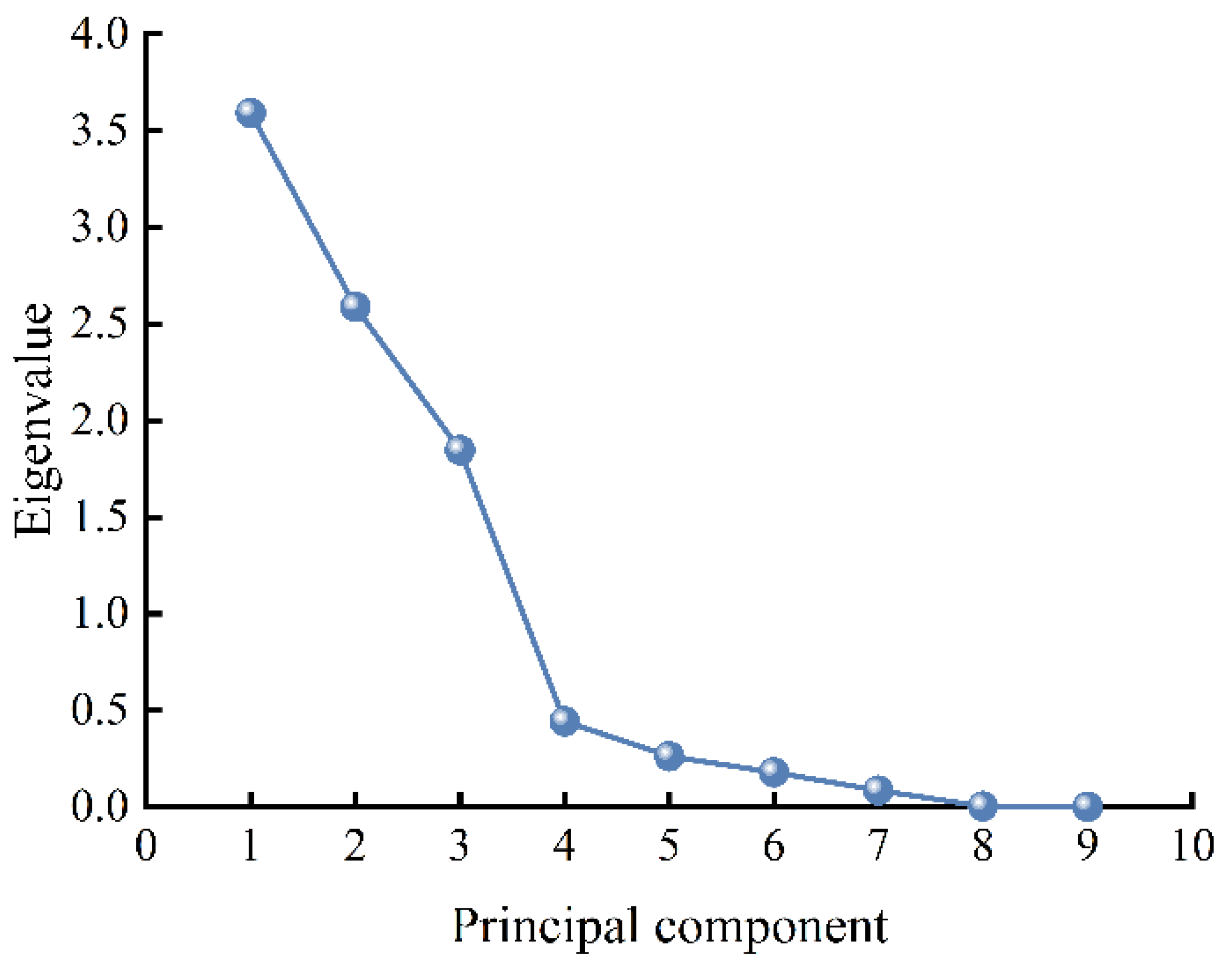

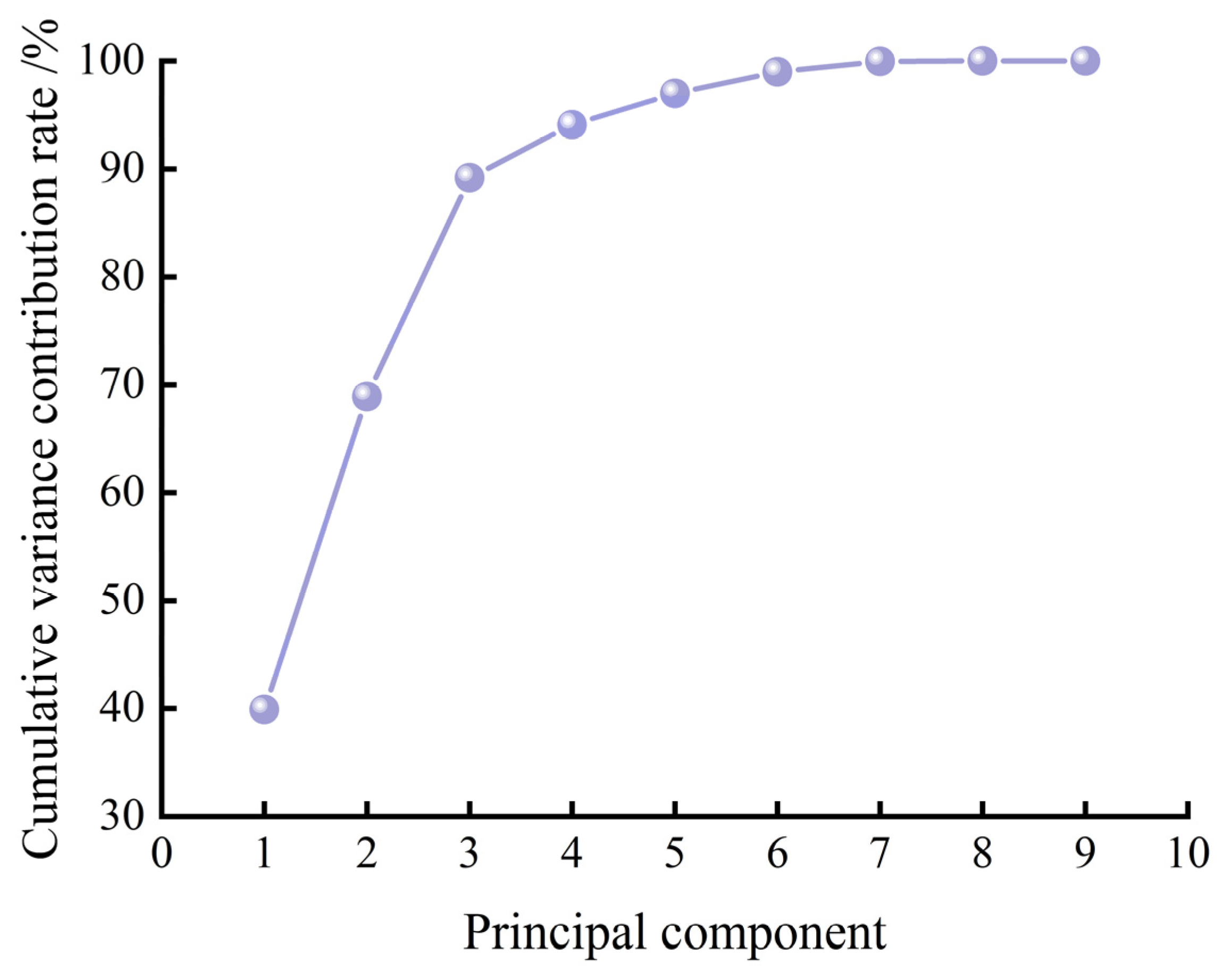

| Principal Component | Eigenvalue | Variance Contribution Rate/% | Cumulative Variance Contribution Rate/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.592 | 39.914 | 39.914 |

| 2 | 2.588 | 28.750 | 68.664 |

| 3 | 1.847 | 20.525 | 89.189 |

| 4 | 0.442 | 4.909 | 94.098 |

| 5 | 0.262 | 2.915 | 97.013 |

| 6 | 0.179 | 1.985 | 98.998 |

| 7 | 0.086 | 0.959 | 99.957 |

| 8 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 99.990 |

| 9 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 100.000 |

| Principal Component Y1 | Principal Component Y2 | Principal Component Y3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ1 | 0.148 | −0.239 | 0.375 |

| γ2 | 0.096 | 0.311 | 0.022 |

| γ3 | 0.327 | −0.014 | 0.021 |

| γ4 | −0.096 | 0.026 | 0.537 |

| γ5 | 0.397 | −0.059 | 0.046 |

| γ6 | 0.388 | −0.129 | −0.126 |

| γ7 | 0.007 | 0.249 | −0.042 |

| γ8 | −0.053 | 0.367 | 0.430 |

| γ9 | −0.142 | 0.429 | −0.032 |

| Test of Function | Wilks’ Lambda | Chi-Square Test | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.280 | 61.016 | 0.000 |

| Discriminant Model | Correct Classification Rate/% | |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set | Testing Set | |

| FDA | 82.14 | 66.67 |

| PCA-FDA | 89.29 | 83.33 |

| SDA-FDA | 85.71 | 83.33 |

| SDA-PCA-FDA | 96.43 | 91.76 |

| SDA-PCA-Bayes | 92.86 | 83.33 |

| Shaft Name | γ1/m | γ5/m | γ6/% | γ7 | γ8/% | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | y-Value | Predicted Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main shaft | 189.3 | 18.6 | 17.3 | 1 | 31.3 | 0.523 | 0.530 | −0.193 | −0.658 | Rupture |

| Auxiliary shaft | 190.4 | 10.2 | 6.8 | 0 | 18.2 | −1.645 | −0.137 | −0.575 | 2.064 | Non-rupture |

| East air shaft | 176.4 | 8.3 | 2.6 | 0 | 7.5 | −0.967 | 1.522 | −0.131 | 2.301 | Non-rupture |

| Lithology | Depth/m | Density /(g·cm−1) | K | Kur | Rf | C | φ | Δφ | K0 | Kns | Kvs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topsoil | 3 | 1.86 | 200 | 300 | 0.6 | 3 | 22 | 3.2 | 0.67 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Medium coarse sand | 8 | 2.2 | 300 | 450 | 0.6 | 3 | 22 | 3.2 | 0.67 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Medium coarse sand | 13 | 2.2 | 300 | 450 | 0.6 | 3 | 22 | 3.2 | 0.67 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Sandy clay | 108 | 2.2 | 400 | 600 | 0.7 | 0 | 30 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.0161 | 0.0161 |

| Sandy clay | 125 | 2.2 | 400 | 600 | 0.7 | 0 | 30 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.0161 | 0.0161 |

| Coarse sand Gravel | 148 | 2.1 | 500 | 750 | 0.6 | 3 | 22 | 11.7 | 0.67 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Coarse sand Gravel | 156 | 2.1 | 500 | 750 | 0.6 | 3 | 22 | 11.7 | 0.67 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| sandy clay | 196 | 2.1 | 430 | 645 | 0.6 | 0 | 30 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.053 | 0.053 |

| Sandy clay | 206 | 2.1 | 430 | 645 | 0.6 | 0 | 30 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.053 | 0.053 |

| Medium sand | 210 | 2.1 | 700 | 1050 | 0.7 | 0 | 30 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 2.536 | 2.536 |

| Medium sand | 214 | 2.1 | 700 | 1050 | 0.7 | 0 | 30 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 2.536 | 2.536 |

| Clay | 228 | 2.2 | 800 | 1200 | 0.7 | 5 | 22 | 17 | 0.6 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Clay | 231 | 2.2 | 800 | 1200 | 0.7 | 5 | 22 | 17 | 0.6 | 0.00021 | 0.00021 |

| Scheme Category | Scheme | Friction Pile Coordinates | Friction Pile Height (m) | Stiffness Coefficient | Dewatering Point Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal schemes | Scheme 1 | (0, 0)~(0, 112.86) | 112.86 | 0.5 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme 2 | (0, 0)~(0, 112.86) | 112.86 | 0.1 | (0, 7) | |

| Scheme 3 | (0, 0)~(0, 112.86) | 112.86 | 0.9 | (0, 7) | |

| Vertical schemes | Scheme 4 | (0, 0)~(0, 49.86) | 49.86 | 0.5 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme 5 | (0, 0)~(0, 235.73) | 235.73 | 0.5 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme | Friction Pile Height (m) | Stiffness Coefficient | Stable Settlement at Failure Point (m) | Settlement at 1 m Radial Distance from Pile (m) | Reduction Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | 112.86 | 0.5 | 0.171 | 0.118 | 30.9% |

| Scheme 2 | 112.86 | 0.1 | 0.163 | 0.117 | 28.2% |

| Scheme 3 | 112.86 | 0.9 | 0.179 | 0.123 | 31.3% |

| Scheme 4 | 49.86 | 0.5 | 0.158 | 0.128 | 19.0% |

| Scheme 5 | 235.73 | 0.5 | 0.190 | 0.138 | 27.4% |

| Scheme | Friction Pile Presence | Distance from Pile to Shaft (m) | Friction Pile Height (m) | Stiffness Coefficient | Dewatering Point Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | Yes | 5 | 112.86 | 0.9 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme 2 | Yes | 10 | 112.86 | 0.9 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme 3 | Yes | 15 | 112.86 | 0.9 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme 4 | No | / | / | 0.9 | (0, 7) |

| Scheme | Friction Pile Height/m | Distance from Shaft to Pile/m | Stable Settlement at Failure Point/m | Settlement at 1 m from Shaft Wall/m | Reduction Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | 112.86 | 5 | 0.150 | 0.007 | 95.3% |

| Scheme 2 | 112.86 | 10 | 0.150 | 0.006 | 96.0% |

| Scheme 3 | 112.86 | 15 | 0.150 | 0.009 | 94.0% |

| Item | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | Scheme 3 | Scheme 4 | Scheme 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction preparation | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Surface grouting | / | / | / | 600 | / |

| Wall-penetrating grouting | 60 | 40 | / | / | / |

| Relief groove construction | 15 | 15 | 15 | / | / |

| Shaft ring reinforcement | / | / | 30 | 30 | / |

| Shaft equipment modification | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Friction pile construction | / | / | / | / | 450 |

| Monitoring instrumentation cost | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Engineering design | 20 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 30 |

| Project close-out | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Total cost | 142 | 112 | 102 | 697 | 517 |

| Duration/days | 55 | 50 | 20 | 150 | 140 |

| Scheme | Content | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | Chemical grouting at 213 m~230 m depth + relief groove at 223 m depth | Effective pressure relief on the shaft wall; good water-plugging effect from grouting | Certain risk associated with creating the relief groove; requires a construction cycle inside the shaft; high cost of chemical materials; high requirements for process and material mix |

| Scheme 2 | Cement grouting at 213 m~230 m depth + relief groove at 223 m depth | Effective pressure relief on the shaft wall; relatively low cost | Certain risk associated with creating the relief groove; requires a construction cycle inside the shaft; poor water-plugging effect from grouting |

| Scheme 3 | Shaft ring reinforcement at 213 m~230 m depth + relief groove at 223 m depth | Short construction period; can quickly control the development of failure | Short duration of protective effect; certain safety risks exist |

| Scheme 4 | Surface grouting to reinforce the loose stratum + shaft ring reinforcement | Minimal construction work inside the shaft; large grouting range | Poor effectiveness in reducing additional stress; high cost and material mix requirements |

| Scheme 5 | Friction pile method at 10 m from the shaft wall | No internal shaft construction required; high shaft protection effectiveness; high safety | High process requirements; high cost |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gai, Q.; Yang, G.; Liu, Q.; Fu, Q.; Liu, S.; Ma, Q.; Lian, C. Intelligent Early Warning and Sustainable Engineering Prevention for Coal Mine Shaft Rupture. Processes 2025, 13, 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124016

Gai Q, Yang G, Liu Q, Fu Q, Liu S, Ma Q, Lian C. Intelligent Early Warning and Sustainable Engineering Prevention for Coal Mine Shaft Rupture. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124016

Chicago/Turabian StyleGai, Qiukai, Gang Yang, Qingli Liu, Qiang Fu, Shiqi Liu, Qing Ma, and Chao Lian. 2025. "Intelligent Early Warning and Sustainable Engineering Prevention for Coal Mine Shaft Rupture" Processes 13, no. 12: 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124016

APA StyleGai, Q., Yang, G., Liu, Q., Fu, Q., Liu, S., Ma, Q., & Lian, C. (2025). Intelligent Early Warning and Sustainable Engineering Prevention for Coal Mine Shaft Rupture. Processes, 13(12), 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124016