Abstract

Agricultural and pastoral parks in China possess abundant biomass resources, such as crop straw and livestock manure. However, insufficient distribution generation capacity and a lack of effective coordination strategies lead to low energy utilization efficiency and high carbon emissions. To address these issues, in this study, a coordinated microgrid optimization strategy is proposed based on multi-energy complementarity. A source–load multi-energy coupling model is established by analyzing the dynamic characteristics of biomass energy flow and incorporating a flexible load demand response mechanism. An optimization model aimed at minimizing operational costs is then developed to coordinate heterogeneous energy sources. Simulations under typical wind–solar–load scenarios demonstrate that the proposed strategy improves operational economy by 12.6% and reduces carbon emissions by 23.3% compared to conventional methods through optimized allocation of demand response resources.

1. Introduction

The low-carbon transition of the global energy system has become a consensus strategy for addressing climate change [1]. Biomass power generation, owing to its advantages such as cost-effectiveness and minimal environmental pollution, plays a crucial role in achieving carbon neutrality goals [2]. As the world’s largest energy consumer, China is actively promoting energy structure transformation under the guidance of its “Dual Carbon” goals. Biomass power generation, which integrates resource recycling and energy production, is regarded as a key pathway for the sustainable development of agricultural and pastoral parks. Despite the annual output of organic waste—such as straw and livestock manure—from which China’s agricultural and pastoral parks possess an energy potential equivalent to 8.63 × 108 megagrams of standard coal, the actual energy conversion efficiency remains notably low, at only about 40% of the theoretical value. This substantial gap primarily stems from two core technical bottlenecks: insufficient penetration of combined heat and power systems and imbalanced configuration of multi-energy storage [3,4], which significantly constrains the full realization of emission reduction potential in this field. Although single utilization models have been adopted in some regions, such as pure biogas projects, the production and utilization of energy remain decentralized, lacking systematic integration and management [5], which leads to low economic benefits and utilization efficiency, resulting in significant resource wastage and unnecessary carbon emissions [6]. In this context, promoting the synergistic and optimized operation of agricultural and pastoral parks can help coordinate various biomass resources, conserve energy, reduce carbon emissions, and achieve cascading energy utilization and multi-energy complementarity, thereby effectively enhancing overall energy utilization efficiency [7,8].

Integrated energy systems (IESs) were initially applied to cogeneration technology [9,10], focusing on the integrated optimization of heating and power networks [11,12]. With the continuous development of energy distribution networks, they have gradually expanded to include various energy forms such as electricity, heating, cooling, and gas [13,14]. According to existing studies, IESs demonstrate significant potential in enhancing economic performance, improving energy utilization efficiency, and reducing carbon emissions [15,16,17]. However, research on electricity–carbon cooperative optimization remains in the exploratory stage, facing challenges such as modeling difficulties and complexity in energy flow analysis [18]. In reference [19], electricity–carbon information for multi-park coordination research is integrated, involving more participants in electricity–carbon markets to effectively improve the economic and low-carbon performance of park IESs. Reference [20] similarly studied the coupling characteristics of carbon and electricity markets, effectively reducing system carbon emissions and economic operating costs through electricity–carbon coordination. Reference [21] established an IES model incorporating hydrogen energy and conducted coordinated optimization research using electricity–carbon mutual recognition, demonstrating effective achievement of low-carbon operation goals for hydrogen-containing systems. In other studies, various types of IES models and CTMs have been analyzed domestically and internationally, summarizing common optimization methods and future development directions [22].

Microgrid cooperative optimization includes coordinating energy dispatch and operational strategies among multiple adjacent microgrids to form clusters or communities [23], aiming to achieve higher energy efficiency, operational economy, and system reliability within a region. However, its widespread application is hindered by the intermittency and volatility of distributed energy resources [24], the complexity of coordinated operation and communication [25], and inadequate policy and market mechanisms [26,27]. Current research is mainly focused on conventional energy scenarios centered on electricity–heat systems. Consequently, existing optimization models and operational strategies lack adaptability when applied to regions with unique energy structures, such as agricultural and pastoral parks. In terms of agricultural and pastoral parks, biomass power generation can effectively achieve energy complementarity and cascaded utilization, significantly alleviating grid operation pressure [28]. However, research on operational characteristics of biomass power generation within this specific context remains insufficient. Reference [29] explores strategies for integrating biomass energy into multi-energy collaborative networks and establishes a multi-process coordinated operation model that includes biogas power generation, which enhances system economics while also optimizing ecological benefits. However, while these studies have established models for IES in agricultural parks, they primarily focus on optimizing either electricity or a single energy form. Consequently, they struggle to resolve the challenge of multi-energy flow synergistic optimization within parks. In this context, research on the collaborative optimization of microgrids in agro-pastoral parks with multi-energy synergy closely aligns with the national “dual carbon” goals [30,31]. Such research addresses the unique energy management challenges of agro-pastoral parks by transitioning rural energy systems from mere consumption to prosumer integration and advancing their role from passive distribution network nodes to active regulatory entities.

In summary, the distinct nature of agricultural park energy systems prevents the direct application of traditional optimization strategies. Developing customized cooperative strategies that leverage local biomass is essential to overcome the challenges of low energy utilization and high carbon emissions in their microgrids.

Given these issues, this paper recommends a coordinated optimization strategy for agricultural park microgrids based on multi-energy complementarity. First, we analyze the conversion characteristics of biomass energy on the source side and flexible load response mechanisms to establish a park source–load model considering multi-energy coupling characteristics. Then, in order to reach minimum park operating costs, we establish a multi-energy complementary coordinated optimization model to holistically optimize the distribution of biomass, electricity, heat, and other energy forms. Finally, we validate the proposed strategy through typical wind–solar–load operation scenarios in agricultural parks. Simulation verification using an actual agricultural park integrated energy test system demonstrates that the proposed optimization strategy can effectively improve park operating economy and reduce carbon emissions through rational allocation of demand response (DR) resources.

In this paper, a coordinated optimization strategy with multi-dimensional innovations is presented. In contrast to existing studies that concentrate mainly on industrial parks and urban energy systems, our work designs a multi-energy complementary system for agricultural–livestock parks. This system integrates biomass, electricity, gas, and heat, leveraging the specific energy profiles and resources of such parks to model energy conversion from agricultural waste with high precision. For the core mechanism, we adopt a straightforward linear carbon cost model, which directly incorporates carbon trading costs into our optimization objectives, moving beyond the more complex tiered mechanism found in ref. [13]. Furthermore, our strategy overcomes the limitations of a single price-based demand response by introducing a hybrid model that combines substitution-type and price-type responses. This enhancement significantly boosts the system’s regulation capacity. At the optimization level, while prior research often addresses economic dispatch in single-market settings while neglecting multi-energy coupling, we propose a unified framework that coordinates demand response, carbon trading, and multi-energy complementarity. This framework ultimately achieves multi-objective optimization, balancing economic efficiency, carbon reduction, and operational performance.

2. Problem Description

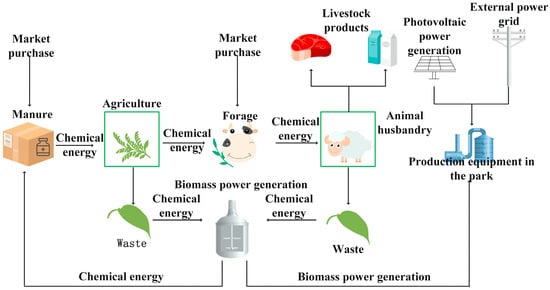

In Figure 1, the integrated energy system model of a typical agricultural–livestock park is illustrated, which primarily consists of multiple energy flows. The system acquires electrical power and gaseous fuel from upstream energy networks, with natural gas being primarily utilized in the combined heat and power (CHP) system and gas boiler (GB). Through energy coupling devices, including CHP, heat-pump (HP), boilers, and biomass power generation, the system achieves bidirectional energy transfer.

Figure 1.

A comprehensive energy system model for agricultural and animal husbandry parks.

According to Figure 1, the material–energy coupling system primarily includes two interconnected components: agricultural production and livestock production processes. In the agricultural production cycle, solar energy is converted into chemical energy through crop photosynthesis, while commercially purchased fertilizers provide additional chemical energy input that partially dissipates during soil decomposition. Agricultural products carry their contained chemical energy to markets, with crop residues (straw, leaves, etc.) being allocated in two ways: some serve as livestock feed to transfer chemical energy to the pastoral production cycle, while others become raw materials for biomass power generation. The livestock production cycle receives chemical energy through both purchased feed and agricultural byproduct-based feed, with livestock products exporting energy to markets and animal waste transferring energy to biomass power generation. The biomass power generation process converts part of the chemical energy from agricultural and livestock waste into electricity through anaerobic digestion, while the remaining chemical energy in the digestate is returned to agricultural production as fertilizer. For its energy needs, the park’s production equipment draws electricity from three sources: biomass power generation, photovoltaic power generation, and purchases from the external grid, forming a complete material–energy circulation system.

Although research on integrated energy systems has achieved considerable maturity, traditional methodologies exhibit significant limitations when applied to agricultural–livestock parks. First, the complex composition and distinct energy characteristics of these parks pose challenges for conventional energy models in adapting to multi-time-scale dynamic response requirements [8]. Second, existing studies predominantly focus on the coordination of conventional energy sources such as electricity, heat, and gas, while neglecting the dynamic conversion characteristics of biomass energy and its deep coupling with other energy forms. This oversight results in low utilization efficiency of biomass resources within the park [2,3,15]. Furthermore, in terms of optimization strategies, most researchers either consider only a single-price-based demand response or concentrate solely on carbon trading mechanisms, failing to effectively integrate these approaches with the park’s multi-energy complementarity characteristics. Consequently, achieving a balance between economic efficiency and low-carbon performance remains challenging [16,29]. As a result, traditional energy system models cannot be directly applied to agricultural-integrated energy systems. There is an urgent need to develop key technologies, including multi-energy load forecasting, energy flow planning, and dispatch modeling and solutions, and comprehensive benefit evaluation to address the current challenges facing agricultural integrated energy systems.

3. Load Demand Response Model Based on Carbon Trading

Electrical loads in agricultural livestock parks demonstrate three distinctive DR characteristics due to their diverse nature. First, primary loads like irrigation systems exhibit pronounced seasonal fluctuations, which are strictly governed by agricultural production cycles and crop growth patterns. Second, specialized loads such as incubation temperature control have rigid operational timing and power-level requirements, significantly limiting their flexibility. Third, temporal mismatches exist between distributed renewable energy generation profiles and peak demand periods of agricultural loads. Furthermore, the geographical dispersion of loads across different stakeholders compounds the challenges of source–load coordination. These operational realities necessitate developing tailored DR models that account for each load type’s specific response characteristics.

3.1. Demand Response Model

3.1.1. Alternative Demand Response

In integrated agricultural–livestock park energy systems, increasing coupling between electricity, heat, and gas energy flows has given rise to substitution DR—a technologically driven branch of DR models that achieves load regulation by substituting forms of energy or technological upgrades. This approach is designed to leverage end-user resources to foster synergistic capabilities for grid interaction. Within substitution DR frameworks, energy-consuming terminals must implement real-time spatial dispatching requirements for energy supply terminals while accounting for multi-energy flow coordination characteristics. This operational paradigm can be mathematically modeled as follows:

where and represent electricity and heat energy flows, respectively, in the agricultural–livestock park’s integrated energy system; and denote the load substitution variation quantities for - and -type energy forms; signifies the conversion coefficients for - and -type energy forms; and indicate the unit calorific values consumed for - and -type energy forms, respectively; represents the electrical-to-thermal conversion efficiency; represents the thermal-to-electrical conversion efficiency; and , , , and specify the maximum and minimum allowable load increments for - and -type energy forms, respectively.

3.1.2. Price-Based Demand Response

Based on the varying sensitivity of park loads to electricity prices, price-responsive loads can be classified into two main types: curtailable loads (CLs) and shiftable loads (SLs). Separate DR models are developed for each type to support the park’s operational dispatch and achieve energy-saving and emission-reduction goals.

Price-based DR is a market-driven mechanism that uses price signals to incentivize users to actively participate in balancing electricity supply and demand. Combining economic efficiency with operational flexibility, PBDR serves as a key component in building modern power systems. Its core principle lies in enabling users to “sense prices and respond to prices,” ultimately achieving a win–win outcome that ensures grid stability, user benefits, and environmental sustainability. However, price-based DR suffers from rigid time-of-use divisions and fixed pricing structures, imposing requirements for active demand-side adjustments in grid support strategies like peak-shaving and frequency regulation, which are long-duration and inherently inflexible.

In this context, CL and SL represent two key types of loads, each corresponding to different response methods and application scenarios.

CL refers to the amount of electricity that users voluntarily reduce during a given time period, reacting to changes in electricity prices. Its defining characteristic is an absolute reduction in electricity usage rather than merely a shift in timing. This type of load is typically sensitive to price fluctuations while ensuring that the fundamental electricity needs of the users are unaffected. The elasticity coefficient between demand-side load and energy pricing must be derived through regression analysis of historical data, as shown in Equation (5). This coefficient allows for qualitative analysis of the relationship between price changes and the temporal variations in user energy demand.

Here, and represent the changes in load and electricity price, respectively, after multi-energy collaborative optimization; and denote the initial values of load and electricity price, respectively; denotes the price elasticity of the demand matrix for CL; and represents the element in the t-th row and k-th column of this matrix, quantifying the elasticity coefficient of load demand at time t in response to electricity prices at time k.

The CL variation model after collaborative optimization is as follows:

where represents the change in CL after optimization; denotes the initial value of CL; and stands for the electricity price.

SL refers to the ability of users to adjust their electricity consumption from peak to valley periods to react to price signals. The key characteristic of SL is the flexible adjustment of consumption time while keeping the total electricity usage constant. The SL variation model after collaborative optimization is as follows:

where represents the change in SL after optimization; denotes the initial value of SL; represents the element in the t-th row and k-th column of ; and represents the price elasticity of the demand matrix for SL.

3.2. Carbon Trading Model

3.2.1. Free Carbon Emission Quota Model

The total carbon quota model for the integrated energy system at is formulated in Equation (8).

where represents the carbon emission quota of the system at time t; represents the carbon emission quota corresponding to the regional unit electricity generation, set at 0.57 Mg/(MW·h), based on the “Baseline Emission Factor for China’s Regional Power Grids in 2019”; and represent the electrical and thermal output power of the gas turbine (GT) at interval ; is the efficiency of conversion for electricity; and represents the thermal output power of the GB at interval .

3.2.2. Carbon Emission Cost Model

With an approximately proportional relationship between the carbon emissions of the unit and its output, based on the carbon emission factor method, the actual cost model of this part is established below:

where represents the actual carbon emissions of the system at time t; and represent the coefficients of carbon emissions for GT and GB, both set at 0.6101 Mg/(MW·h).

To encourage user participation in carbon trading, users are allowed to trade carbon emission quotas independently under the CTM established in this paper. The carbon trading cost model is as follows [29]:

where represents the market price of carbon trading.

4. Multi-Energy Collaborative Optimization Strategies for Agricultural and Pastoral Parks

4.1. Multi-Energy Collaborative Operation Optimization Model for Parks

The collaborative operation optimization strategy proposed in this paper aims to establish a mathematical model for the coordinated scheduling of multiple energy sources within agricultural–livestock parks, ultimately achieving minimization of total system operational costs. The overall framework of this strategy is as follows: Firstly, based on the previously developed load demand response model and carbon trading mechanism, a multi-energy collaborative optimization model is constructed with economic efficiency as its core objective. The constraint conditions encompass instantaneous energy balance requirements for electricity, heat, and gas, as well as physical operational limits of various equipment. Secondly, by solving this model, optimal operational plans for all types of park equipment are formulated across the scheduling horizon. Given the model’s nonlinear characteristics and complex constraints, traditional mathematical programming methods are prone to local optima. Therefore, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is employed for model solutions, which rarely rely on gradient information of the objective function, enabling effective handling of complex constraints while obtaining high-quality global optimal solutions.

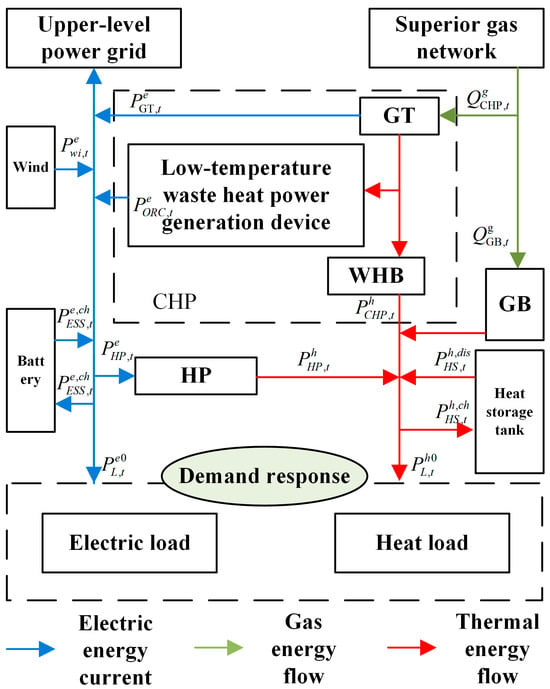

The normal operation of agricultural and pastoral parks relies on the coordinated functioning of internal equipment, with the energy flow within the park illustrated in Figure 2. The operation of the integrated energy system in the agricultural–livestock park centers on the coupling and conversion of three energy forms: electricity, gas, and heat. Electricity is sourced from grid purchases, wind power generation, a combined heat and power (CHP) system, and battery discharge. This collectively supplies power to heat pumps (HPs) and various electrical loads. Surplus electricity generated during operation can either be fed back to the external grid or stored in batteries, thereby enhancing the system’s economic efficiency and flexibility. Gas energy is supplied by natural gas purchased from external networks and distributed to gas turbines (GTs) and gas boilers (GBs). In GT units, natural gas serves as fuel to drive power generation equipment, enabling combined heat and power production to simultaneously generate electricity and thermal energy. In GB units, natural gas is directly combusted to produce high-temperature thermal energy, allowing rapid response to heating demands during extreme cold conditions or CHP maintenance. Thermal energy is jointly supplied by the CHP system, HPs, GBs, and thermal storage tanks to meet the park’s heat load requirements. Surplus thermal energy can be stored in thermal storage tanks for energy time-shifting. As a result, there is a need to establish a multi-energy collaborative optimization model to schedule different devices and enhance the integration of renewable energy.

Figure 2.

Park energy flow.

A multi-energy collaborative optimization model for agricultural and pastoral parks is developed based on the established CTM, aiming to minimize the total cost, including energy procurement costs, carbon trading costs, and operational maintenance costs, thus maximizing user-side revenues:

Energy procurement cost is expressed as follows:

where represents a complete operating cycle; and denote the electric power bought and sold from the main grid at interval ; and represent the buying and selling electricity prices from the main grid at interval ; is the amount of natural gas purchased; and denotes the natural gas unit price purchased.

The carbon trading cost refers to the total carbon trading costs over a complete operating cycle, with the model expressed as follows:

The operational and maintenance cost model is given below:

where represents the six types of equipment: wind turbine, CHP, GB, HP, battery, and thermal storage tank; denotes the operational and maintenance coefficient for the -th-type equipment; represents the output power.

The energy balance is written as follows:

Equations (15)–(17) represent the energy balance constraints for electrical energy, thermal energy, and gas energy, respectively, where and are the electricity consumption power and thermal output power of the HP; denotes the electric and thermal output power; denotes natural gas consumption of the combined heat and power system at interval ; and indicate the power exchange in the energy storage system; and represent the electricity and thermal loads before collaborative optimization; signifies the natural gas consumption of the GB; stands for the thermal output power of the GB. and correspond to the thermal power exchange of the thermal storage tank at interval .

The constraint of wind power generation is as follows:

Equation (18) indicates that wind power output has uncertainty, with the actual generation power being typically less than the theoretically predicted power. In this equation, and represent the actual and predicted wind power generation at time , respectively.

Equations (19) and (20) represent the constraints for electricity and thermal output from the combined heat and power (CHP) system, where and are the electric and thermal outputs of the gas turbine, respectively. Equations (21) and (22) express the constraints for electricity and thermal output from the gas boiler. Equation (23) outlines the constraint for waste heat power generation from the CHP, where represents the biomass waste heat utilization power generation. Equations (24) and (25) indicate the constraints for waste heat distribution from the gas turbine, where and represent the waste heat distribution coefficient of the GT; the electricity generation from the CHP comprises the GT power generation and biomass low-grade waste heat utilization, while the thermal output is generated by the waste heat boiler.

Given that user electricity demand can fluctuate during usage, affecting the responsiveness to DR initiatives, it is essential to establish a user satisfaction constraint:

where and represent the satisfaction levels of users regarding energy consumption patterns and the minimum acceptable level of energy supply service satisfaction, respectively.

4.2. Optimization Model Solution Methods for Agricultural and Pastoral Parks

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based meta-heuristic inspired by the cooperative foraging behavior of bird flocks and fish schools. In PSO, each candidate solution of the optimization problem is regarded as a “particle”. The position of a particle represents a point in the search space, and its quality is evaluated by a fitness function. By iteratively updating particle velocities and positions under the joint influence of individual and collective experience, the swarm gradually converges towards an optimal or near-optimal solution.

In this study, PSO is adopted to solve the integrated scheduling problem of the agricultural–pastoral park with multi-energy complementarity, carbon trading, and demand response. The position vector of particle , denoted as , is determined by stacking all decision variables over the 24 h horizon, including the following:

- The hourly electrical and thermal outputs of controllable units (gas boiler, biomass generator, combined heat and power unit, heat pump, etc.);

- The charging and discharging power of electrical and thermal energy storage systems;

- The demand–response adjustment of electrical and thermal loads.

During initialization, the population size is set, with each particle’s position represented as a vector and velocity also represented as a vector .

where and are the learning factors; and constitute random numbers ranging ; is the iteration count; is the identifier; and represents the inertia weight.

The velocity and position of particle at iteration are updated according to Equations (27)–(30). In these equations, c1 and c2 are the cognitive and social learning factors; r1 and r2 are independent random numbers uniformly distributed in [0, 1]; and ωt is the inertia weight that controls the balance between global exploration and local exploitation. A linearly decreasing strategy is adopted for , where the inertia weight is gradually reduced from a relatively large initial value to a smaller final value along the iterations, so that the swarm explores widely in the early stage and refines the solution in the later stage. After each position update, any component of that exceeds its physical bounds (e.g., unit output limits and SOC limits) is projected back to the feasible interval by saturation mapping. The concrete parameter settings of the swarm are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

PSO parameter settings.

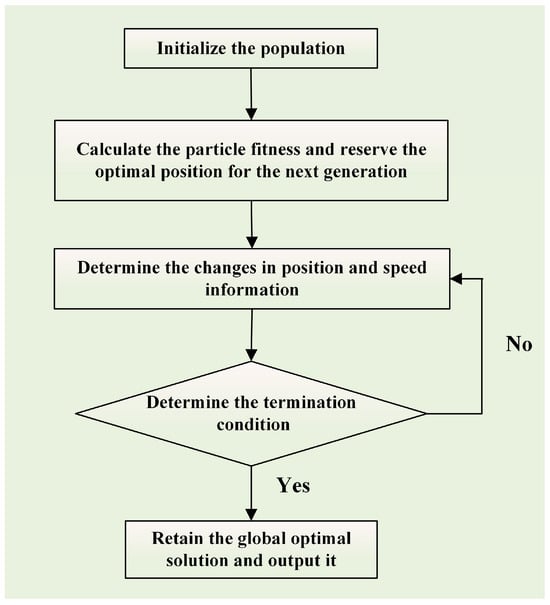

The overall procedure of the PSO algorithm, corresponding to the flowchart in Figure 3, can be summarized as follows:

Figure 3.

Flowchart of solution.

Step 1: Set population parameters in Table 1. Initialize the population size , inertia weight , learning factors and , and the position vector and velocity vector for each particle, where and are between 0 and 1.

Step 2: Evaluate particle fitness. Randomly generate the initial position vectors and velocity vectors of particles within the feasible region, and calculate the fitness value of each particle (i.e., the comprehensive operating cost plus penalty terms). Take the current position of each particle as its individual best position , and select from all particles the one with the best fitness for the global best position, g, and record the corresponding fitness value.

Step 3: Update position and velocity. After iteration , update according to Equations (27)–(30) and compute the new fitness value. If the new fitness value satisfies as well as hard constraints such as output limits and SOC limits, then update ; otherwise, maintain the original value.

Step 4: Check termination conditions. The algorithm is considered to have converged and be terminated if either of the following conditions is satisfied:

- The number of iterations reaches the preset upper limit,

- Within consecutive generations, the relative change in the global best fitness is smaller than a threshold ().

If the termination conditions are not yet met, set and return to Step 3 for further iterations. When the algorithm terminates, the best global position obtained is the optimal scheduling scheme for the multi-energy system of the agricultural park, and the corresponding fitness value is the minimum comprehensive operating cost.

5. Analysis of Calculation Examples

5.1. Description of the Calculation Example System

This paper takes a comprehensive energy system of a certain agricultural and pastoral park as the research object, as shown in Figure 2. The operation cycle is 24 h with a unit operation interval of 1 h. Firstly, three scenarios are set to verify and analyze the multi-energy collaborative optimization strategy of the park:

- Scenario 1: only considering the CTM;

- Scenario 2: only considering DR;

- Scenario 3: considering coordinated multi-energy optimization for both aforementioned scenarios.

Secondly, two scenarios are established to analyze the impact of high and low renewable energy outputs on the collaborative optimization strategy:

- Scenario 4: high renewable energy output scenario;

- Scenario 5: low renewable energy output scenario.

Thirdly, the influence of the carbon trading price on the optimal dispatch and the cost–emission trade-off is analyzed. Finally, to further validate the robustness of the results and identify key driving factors, a global sensitivity analysis based on total-effect Sobol indices is carried out for three critical parameters in the demand and conversion modules (electric load self-elasticity ; thermal load self-elasticity ; and the WHB/ORC heat-splitting coefficient ). This analysis quantifies the relative contribution of each parameter to the variability of system performance.

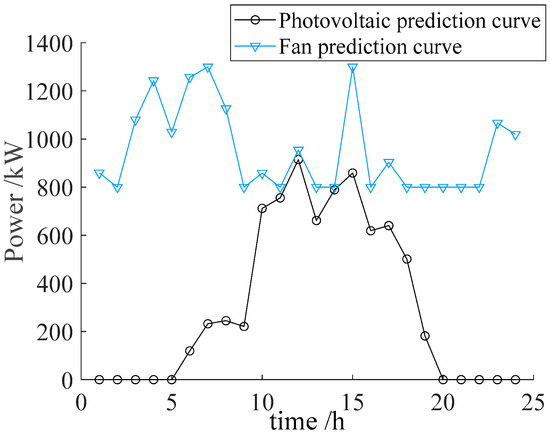

Finally, other parameters include natural gas price at 2.55 CNY/m3; equipment parameters of the agricultural and pastoral park in Figure 2; time-of-use electricity prices as shown in Table 2 and Table 3; wind and solar power generation forecasts for the park system in Figure 4. Note: Unless otherwise specified, all economic quantities in the text are denominated in Chinese CNY. To facilitate an understanding of international readers, referring to the average exchange rate of 2024, it can be approximately assumed that CNY 1 = USD 0.1406.

Table 2.

Equipment parameters for agricultural and animal husbandry parks.

Table 3.

Electricity price based on time of use.

Figure 4.

Wind and solar power output prediction in agricultural and animal husbandry parks.

5.2. Collaborative Optimization Results

The costs and carbon emissions of the comprehensive energy system in the agricultural and pastoral park under the three scenarios are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Operation status of each scenario.

From Table 4, it is clear that compared to Scenario 1, the carbon emissions in Scenario 3 decreased by 20.7% (from 39,664 kg to 31,418 kg, i.e., −8246 kg), while the total profit increased by 3.8% (from CNY 37,985 to CNY 39,446, i.e., CNY +1461). Based on the CTM, the park system possesses carbon emission allowances. Through multi-energy collaborative optimization technology, not only was there a transfer of load between different price periods, but there was also a mutual substitution between electricity and heat, which smoothed the load curve and effectively improved the system’s economic and environmentally friendly operation. Compared to Scenario 2, carbon emissions in Scenario 3 decreased by 23.3% (from 40,972 kg to 31,418 kg, i.e., −9554 kg), and the total profit increased by 12.6% (from CNY 35,021 to CNY 39,446, i.e., CNY +4425). This indicates that considering the CTM can reduce carbon emissions in the park while optimizing operating costs, thereby promoting energy conservation and emission reduction in the comprehensive energy system of the park.

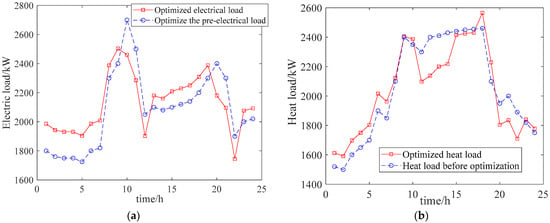

The comparison of electricity and heat loads before and after optimization in Scenario 3 is shown in Figure 5. From this figure, it can be observed that compared to the system’s electricity and heat loads before optimization, the daily average load fluctuations decreased by 12.8% and 1.6%, respectively, after optimization, with a significant transfer of load to the low-price period during early morning (0:00–7:00). Therefore, the collaborative optimization technology shifted loads across different price periods, leading to a smoother load profile and achieving the goal of peak shaving and valley filling.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different loads before and after optimization. (a) Electric load; (b) heat load.

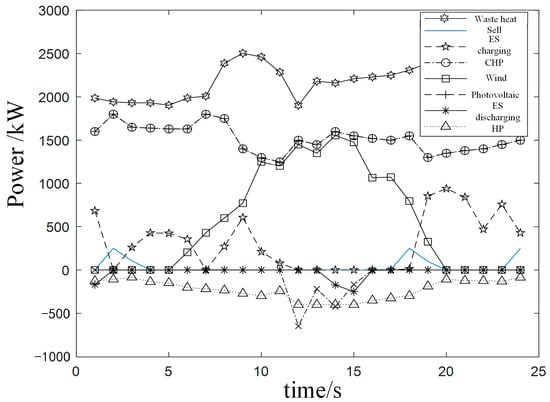

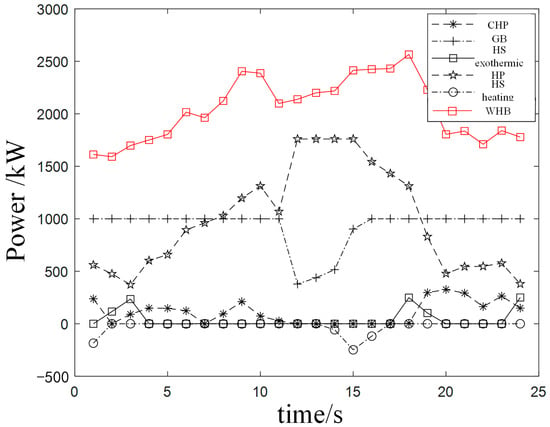

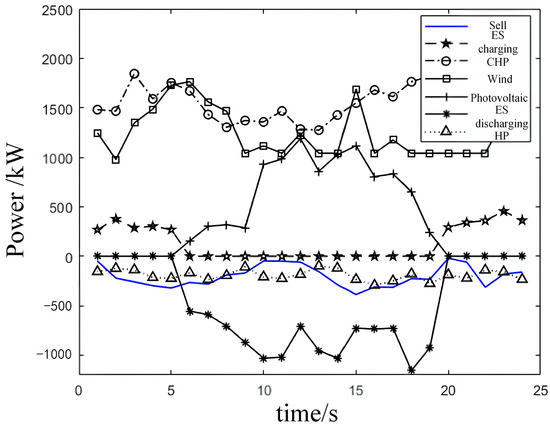

The electricity and heat output conditions in Scenario 3 are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. During peak and flat periods when electricity prices were relatively high, the cost of purchasing electricity from the upper level exceeded that of purchasing gas. In peak periods, the park system’s HPs and electrical loads were supplied by wind power, CHP generation, and thermal storage systems, which reduced the amount of high-priced electricity purchased. During flat periods, the electrical loads and HPs were met by wind power and CHP, with the HPs and CHP supplying the system’s thermal loads, while the shutdown of gas GBs lowered gas costs.

Figure 6.

Electric energy output in scenario 3.

Figure 7.

Heat energy output in scenario 3.

In low-price valley periods, the system’s electricity demand is met by wind power generation and purchasing electricity from the upper level, while the thermal load is supplied by HPs and CHP.

Overall, the system optimizes energy storage to reduce electricity purchase costs by 26.2%. The thermal storage shifts heat energy in the range of 500–800 kW, resulting in a 16.7% reduction in gas consumption. The HPs utilize excess wind and solar power, and the CHP improves the overall energy utilization efficiency by 17.4%, achieving efficient operation of the comprehensive energy system in the agricultural and pastoral park.

Figure 8 illustrates the park system’s electricity operation under the high new energy output conditions in Scenario 4. It can be seen that due to the high wind and solar output, the park’s load primarily relies on wind and solar power generation, with surplus electricity sold to the main grid. During the valley period from 0:00 to 8:00, market electricity prices are low, and wind and solar output are relatively small. At this time, the park’s load is supported by wind and solar power, CHP units, and electricity purchased from the market, while energy storage also charges at a low cost.

Figure 8.

The park system’s electricity operation under high new energy output conditions.

During the flat periods from 8:00 to 9:00, 12:00 to 19:00, and 22:00 to 24:00, electricity prices rise, and wind and solar output increase. The park’s load during these times is met by wind and solar power, CHP units, and energy storage, with any surplus electricity being sold to the main grid for profit. In peak periods from 9:00 to 12:00 and 19:00 to 22:00, electricity prices reach their highest point while wind output increases. Purchasing electricity from the market during these times incurs additional costs; therefore, energy storage devices and CHP units increase their power output to balance the supply–demand gap.

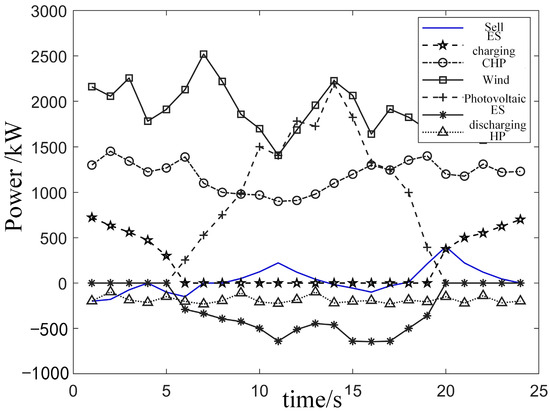

Figure 9 shows the electricity output situation of the park under the low new energy output conditions in Scenario 5. Due to the low wind and solar output, the park mainly relies on CHP for power supply and needs to purchase electricity from the main grid, with other circumstances similar to those discussed for Scenario 4.

Figure 9.

The electricity output situation of the park under low new energy output conditions.

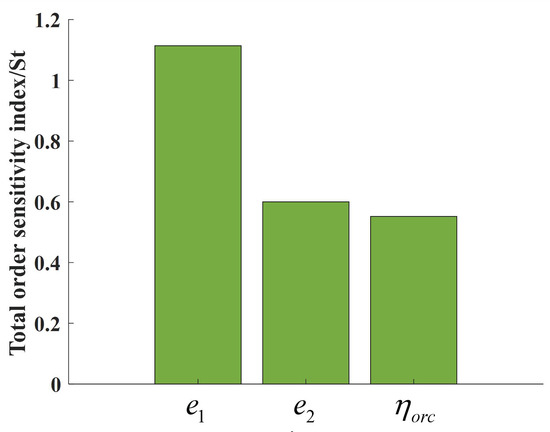

To further examine the robustness of Scenario 3, a total-effect Sobol sensitivity analysis was conducted on three key parameters in the demand and conversion modules: the electric load self-elasticity ; the thermal load self-elasticity ; and the WHB/ORC heat-splitting coefficient . As shown in Figure 10, exhibits the dominant influence on the objective, with a total-effect index close to 1.0, while and have moderate but non-negligible impacts (both around 0.55–0.60). This indicates that the economic and low-carbon gains mainly depend on how strongly electric loads respond to price signals, whereas thermal elasticity and waste-heat splitting serve as secondary levers. Practically, accurate identification and effective activation of electric demand response are, therefore, critical to fully realize the benefits of the coordinated multi-energy framework.

Figure 10.

Total-order sensitivity results.

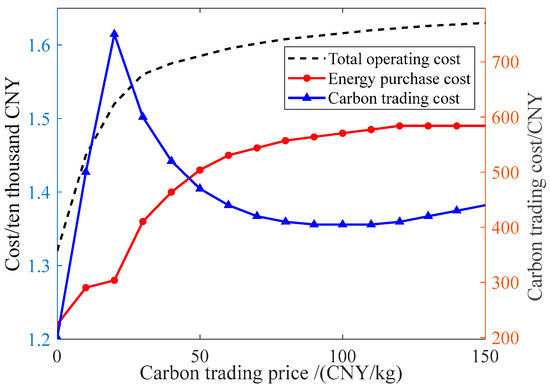

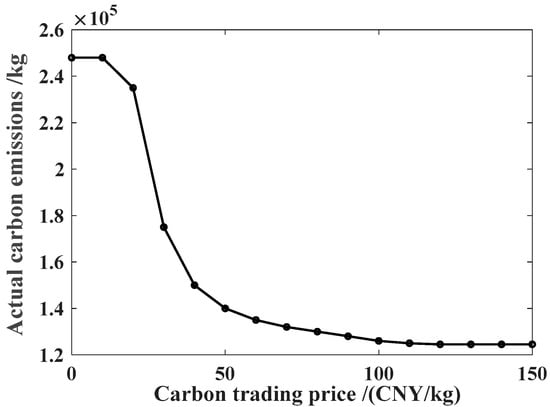

In Figure 11 and Figure 12, the carbon trading price acts as the weight of carbon cost in the objective function, thereby reshaping the optimal dispatch and jointly affecting the energy-purchase cost, carbon trading cost, and total operating cost. When the carbon price is low, the penalty is insufficient to change the dispatch priority of gas-based units, so actual emissions remain nearly unchanged; consequently, the carbon trading cost rises with the carbon price, and together with a higher energy-purchase cost, the total operating cost increases rapidly. Once the carbon price exceeds a threshold, the optimizer begins to cut emissions noticeably by increasing the shares of low-carbon options such as wind and photovoltaic generation, waste-heat recovery, and heat-pump heating. In this region, the carbon trading cost shows a “first-increase-then-decrease” pattern, while the energy-purchase cost rises initially due to higher combined heat and power output and then stabilizes, leading to a slower growth rate of total cost. At around 120 CNY/kg, the carbon trading cost reaches its minimum; however, further price increases place excessive weight on carbon cost and push low-carbon dispatch toward saturation, causing carbon trading costs, energy-purchase costs, and total operating costs to rise again. Overall, these results indicate an effective decarbonization price range and a nonlinear cost–emission trade-off, highlighting that a well-calibrated carbon price is crucial for balancing economic performance and emission reduction.

Figure 11.

Changes in the price–cost relationship of carbon trading. (CNY 1 = USD 0.1406).

Figure 12.

Actual carbon emissions–carbon price curve. (CNY 1 = USD 0.1406).

6. Conclusions

To address the issues of low energy utilization and high carbon emissions in agricultural and pastoral parks, this paper proposes a microgrid collaborative optimization strategy that integrates multi-energy complementarity and CTMs. By establishing a source–load coupling model that accounts for the dynamic conversion characteristics of biomass energy and flexible load responses, and aiming to minimize system operating costs, we comprehensively optimize the scheduling of electricity, heat, and gas multi-energy flows, significantly enhancing the economic performance and environmentally friendly characteristics of parks. The specific conclusions are listed below:

- In comparison to the pre-optimization system’s electricity and heat loads, the collaborative optimization technology facilitates the shifting of loads between different pricing periods, resulting in a smoother load curve and achieving peak shaving and valley filling effects.

- In comparison to traditional operating modes, the proposed strategy reduces operational costs by 12.6% and decreases carbon emissions by 23.3% through optimized DR allocation, validating the comprehensive benefits of multi-energy collaboration and CTMs.

- As carbon trading prices rise and effectively reduce carbon emissions, they also lead to an increase in carbon trading costs. Different levels of carbon trading prices have varying impacts on the system’s operation costs and carbon emissions. Therefore, scientifically and reasonably setting the carbon trading price can achieve low-carbon development while considering economic benefits.

While this study validates the effectiveness of the proposed strategy, several limitations remain. First, the model relies on accurate forecasts of wind generation and load demand, with prediction errors introducing uncertainties that affect optimization performance in practical applications. Second, the performance of the PSO algorithm is significantly influenced by its parameter settings. This study employed a fixed parameter set, and future research could explore adaptive parameter tuning strategies to further enhance computational efficiency and solution quality. Finally, the current model primarily considers three energy carriers; future work should incorporate additional energy forms, such as water and hydrogen, to establish a more comprehensive multi-energy complementary framework.

7. Discussion

The multi-energy complementary and collaborative optimization framework proposed in this paper was validated through the case study to enable agro-pastoral parks to operate at low cost and low carbon emissions while fully satisfying coupled electricity–heat–gas demand constraints. The scientific significance of this work lies not only in introducing carbon trading and demand response, but more importantly in embedding them into a unified energy–carbon-coupled objective and multi-energy coordination constraint system, thereby activating the park’s peak-shaving/valley-filling potential and cross-carrier flexibility at the system level. Specifically, the carbon trading mechanism explicitly converts the emission costs of carbon-intensive units such as gas turbines and gas boilers into marginal operating costs, reshaping dispatch priorities and steering the solution toward low-carbon supply routes including wind and photovoltaic generation, waste-heat-driven organic Rankine cycle power, and heat-pump heating. Demand response, in turn, redistributes and smooths electric and thermal loads across time periods, opening economic windows for storage charging/discharging and electricity–heat substitution, and providing demand-side support for the temporal matching of low-carbon supply. This closed-loop coordination allows the system to achieve simultaneous cost reduction and emission mitigation, whereas considering either mechanism alone cannot trigger comparable comprehensive gains. Furthermore, the carbon-price sensitivity analysis and total-effect Sobol indices corroborate these findings from a robustness perspective: carbon-price variations yield a typical nonlinear cost–emission trade-off with a clear decarbonization threshold and diminishing marginal abatement costs, indicating that a well-calibrated carbon-price range is crucial for jointly optimizing economy and emissions; meanwhile, electric load self-elasticity contributes most to profit variance, highlighting that accurate identification and effective activation of demand–response parameters are key levers for amplifying overall park benefits.

For broader deployment, the proposed framework has a solid structural basis that can scale to larger agro-industrial complexes, but further work is still needed in the following aspects:

- For integrated energy systems with electricity, heat, and gas demands, we will introduce gas–load demand response and a tiered carbon trading mechanism and systematically evaluate how different response structures affect operating cost and carbon emissions.

- Considering uncertainties in wind and photovoltaic outputs, biomass supply, and user responses, we will develop stochastic or robust optimization models to enhance reliability and disturbance-resilience under real operating fluctuations.

- For larger agro-industrial zones or multi-park clusters, we will explore hierarchical/zonal coordination and decomposition-based solution schemes to improve scalability and computational efficiency.

- Toward real-world deployment, we will use demonstration park data to model online elasticity identification, data acquisition limitations, and communication-infrastructure constraints, and validate online executability and control feasibility through rolling optimization or model predictive control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; validation, X.H.; investigation, L.Z.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and Z.N.; writing—review and editing, H.Z. and Z.N.; supervision, S.F.; project administration, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province, grant number 25JRRA415.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hailong Zhang, Zhen Niu, Linxiang Zhao, Shijun Wang, Xin He were employed by the State Grid Gansu Electric Power Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Definition | Unit |

| Substitutable electrical load quantity | kW | |

| Substitutable heating load quantity | kW | |

| Electrical-to-thermal conversion efficiency | \ | |

| Thermal-to-electrical conversion efficiency | \ | |

| Conversion coefficients for electrical and thermal energy forms | \ | |

| Changes in load | kW | |

| Changes in electricity price | CNY | |

| Initial values of load | kW | |

| Initial values of electricity price | CNY | |

| Elasticity coefficient of CL demand at time t in response to electricity prices at time k | \ | |

| Change in CL after optimization | kW | |

| Initial value of CL | kW | |

| Electricity price | CNY | |

| Change in SL after optimization | kW | |

| Initial value of SL | kW | |

| Elasticity coefficient of SL demand at time t in response to electricity prices at time k | \ | |

| Carbon emission quota of the system at time t | Mg/h | |

| Carbon emission quota corresponding to the regional unit’s electricity generation | Mg/(MW·h) | |

| Electrical output power of the GT at the interval | MW | |

| Thermal output power of the GT at the interval | MW | |

| Thermal output power of the GB at the interval | MW | |

| Actual carbon emissions of the system at time t | t/h | |

| Coefficients of carbon emission for the GT | Mg/(MW·h) | |

| Coefficients of carbon emission for the GB | Mg/(MW·h) | |

| Market price of carbon trading | CNY/t | |

| Bought electric power from the main grid at intervals | kW | |

| Sold electric power from the main grid at intervals | kW | |

| Amount of natural gas purchased | ||

| Buying electricity prices from the main grid at intervals | CNY/kW | |

| Selling electricity prices from the main grid at intervals | CNY/kW | |

| Natural gas unit price purchased | CNY/ | |

| Carbon trading cost | CNY | |

| Operational and maintenance costs | CNY | |

| Output power | kW | |

| Electricity consumption power of the HP | kW | |

| Thermal output power of the HP | kW | |

| Electric output power | kW | |

| Thermal output power | kW | |

| Natural gas consumption of the combined heat and power system at interval | ||

| , | Power exchange in the energy storage system | kW |

| Electricity loads before the collaborative optimization | kW | |

| Thermal loads before the collaborative optimization | kW | |

| Natural gas consumption of the GB | ||

| Thermal output power of the GB | kW | |

| , | Thermal power exchange in the thermal storage tank at interval | kW |

| Actual wind power generation at time | kW | |

| Predicted wind power generation at time | kW | |

| Electric outputs of the gas turbine | kW | |

| Thermal outputs of the gas turbine | kW | |

| Biomass waste heat utilization for power generation | kW | |

| Satisfaction levels of users regarding energy consumption patterns | \ | |

| Minimum acceptable level of energy supply service satisfaction | \ |

References

- Slameršak, A.; Kallis, G.; O’Neill, D.W. Energy requirements and carbon emissions for a low-carbon energy transition. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Sun, X.B.; Fu, X.B.; Tang, Y.H.; Li, C.G. Low-carbon dispatch method of rural chemical industry integrated energy system considering power to ammonia and biomass waste energy conversion. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 3350–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, Z.F.; Can, M.Y.; Bai, H.H.; Ta, N. Analysis of the Yield and Comprehensive Utilization Status of Crop Straw in China. J. China Agric. Univ. 2021, 26, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Jiang, X.D.; Xu, G.W. Fully Exploiting the Comprehensive Utilization Efficiency of Biomass for Energy and Materials. China Dev. 2024, 24, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhan, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J.; Xie, S.; Meng, C.; Cao, L.; Wang, X.; Shah, N.; et al. Analysis of biomass polygeneration integrated energy system based on a mixed-integer nonlinear programming optimization method. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 271, 122761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, A.; Magaril, E.; Karaeva, A. Environmental and economic efficiency assessment of biogas energy projects in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. Energ. Ecol. Environ. 2024, 9, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.W.; Strunz, K.; Brown, T.; Sun, H.B.; Neumann, F. Multi-energy system horizon planning: Early decarbonisation in China avoids stranded assets. Energy Internet 2024, 1, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Li, H.R.; Bai, J.H.; Zhang, R. Research progress in biomass coupling cogeneration systems for cooling, heating, and electricity. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisacane, O.; Severini, M.; Fagiani, M.; Squartini, S. Collaborative energy management in a micro-grid by multi-objective mathematical programming. Energy Build. 2019, 203, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falope, T.; Lao, L.; Hanak, D.; Huo, D. Hybrid energy system integration and management for solar energy: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 21, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lu, C.P.; Xu, W.; Yang, F. Design and Research of Multi energy Complementary Microgrid System with Pumped Storage Power Station. Shandong Electr. Power 2023, 50, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Jin, Y.L.; Yang, Y.F.; Cao, J.; Wu, X.J. Research on the optimization of daily operation of virtual power plants considering peak shaving auxiliary services. Shandong Electr. Power 2024, 51, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yuan, F.; Dai, Y.; Liu, W.M.; Zhang, H. A comprehensive energy system optimization scheduling model that takes into account the tiered carbon trading mechanism and load response. Shandong Electr. Power 2024, 51, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.W.; Luo, Y.B.; Kong, L.Q.; Fang, S.D.; Niu, T.; Chen, G.H.; Liao, R.J. A two layer energy management method for distributed ship energy storage system with state coupling constraints. Proc. CSEE 2025, 45, 2500–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, W.Y. Exergoeconomic analysis of integrated energy systems of power to gas-carbon capture power plant. Power Gener. Technol. 2024, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.X.; Yan, X.Y.; Shao, Z.G.; Li, Y.M.; Zheng, X.H.; Zhang, H. Review on modeling and energy flow calculation methods for integrated energy systems. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 50, 1376–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.L.; Han, X.Q.; Li, T.J.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, C. A multifaceted low-carbon trading approach for integrated energy systems accounting for dynamic electricity-carbon demand response. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Zheng, W.T.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Wang, X. Source-load low-carbon economic dispatch method for hydrogen multi-energy system based on mutual recognition of carbon-green certificates and electric and thermal flexible loads. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Z.; Dong, H.J.; Li, S.L.; Zhong, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.Y.; Wu, W.L. Review of optimal dispatching for the aggregation of micro-energy grids based on distributed new energy. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 7952–7970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.M.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, W.; Xiao, Y. Research on Multi Objective Load Optimization of Mother Control Cogeneration System Based on EBSILON. Shandong Electr. Power 2024, 51, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Min, S.S.; Hu, M. Overview of the current situation of biomass gasification power generation in China. Power Syst. Eng. 2020, 36, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, G.C.; Wang, X.X.; Deng, L.; Zhou, L.Y. Analysis of biomass gasification coupled power generation to enhance the flexibility of coal-fired units. Therm. Power Gener. 2018, 47, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Xu, Y. Temporally-coordinated optimal operation of a multi-energy microgrid under diverse uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, K.; Balamane, W. Reducing intermittency using distributed wind energy: Are wind patterns sufficiently diversified within France? Energy 2024, 313, 133516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zholbaryssov, M.; Hadjicostis, C.N.; Dominguez-Garcia, A.D. Fast coordination of distributed energy resources over time-varying communication networks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, K.R.; Gao, Y.; Bian, X.Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, D.D. Coordinated scheduling optimization for Computility center microgrid considering computing resources dynamic pooling. Appl. Energy 2025, 393, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, A.Q.; Morteza, V.; Mohammad, S.J.; Antonio, P.F.; João, P.S.C. A Price-Based Strategy to Coordinate Electric Springs for Demand Side Management in Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.R.; Deng, Y.; He, X.N.; Kumar, P.; Bansal, R.C. A novel methodological framework for the design of sustainable rural microgrid for developing nations. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24925–24951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Q.; Zhang, G.J.; Lv, J. Application of energy-carbon flow charts in high-tech industrial park. Procedia Eng. 2017, 24, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.Q.; Yi, Z.K.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Ding, Z.H.; Xi, M.F.; Zhu, X.C.; Rong, S.; Sun, Y.; Kuang, H.H. A generalised dynamic energy flow model in multi-energy network. Energy Internet 2024, 1, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.C.; Chen, C.H.; Li, L.; Huang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, J. 2006 China energy flow chart. Energy China 2009, 31, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).