Abstract

A novel and rapid ball-milling approach was developed in this study to efficiently intercalate hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA-Br) into vermiculite (VMT) within only 15 min. The raw granular VMT (2–3 mm) was first ground into fine powder using an airflow pulverizer. A suspension containing VMT and HDTMA-Br (1 CEC) in deionized water was then subjected to planetary ball milling at 450 r/min (25 °C), followed by washing and drying to obtain organo-vermiculite (OVMT) with a particle size of 44–5 µm. X-ray diffraction, Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Thermogravimetric Analysis analyses confirmed successful intercalation, with the basal spacing expanding from 1.46 nm to 4.51 nm. Transmission Electron Microscopy observations further revealed partial delamination of lamellar structures and a pronounced reduction in particle size, supporting the structural reorganization induced by the mechanochemical process. In addition, nitrogen adsorption analysis showed that the BET surface area decreased by 4.05 m2·g−1, while the average pore diameter increased by 3.2 nm, indicating the development of a more hydrophobic interlayer environment. Overall, this approach offers a practical route for producing organophilic silicate materials and shows strong potential for wastewater treatment applications, particularly for the adsorption of organic pollutants and heavy-metal ions.

1. Introduction

Layered silicate minerals such as montmorillonite (MMT), sepiolite, illite, and vermiculite (VMT) have attracted great attention due to their excellent adsorption, expansibility, plasticity and high cation exchange capacity [1]. Among them, with the development of material sciences, VMT has shown particular potential as an advanced functional material due to its high crystallinity, structural stability, and good ion-exchange ability. These features make VMT a promising candidate for applications in adsorption, catalysis, environmental remediation, and polymer–clay nanocomposites [2,3,4].

However, the inherent hydrophilicity of VMT, arising from its interlayer inorganic cations, limits its compatibility with organic systems and hinders its industrial use [5]. To overcome this limitation, ion-exchange reactions have been widely employed to replace the interlayer inorganic cations, producing organo-modified vermiculite (OVMT) [6,7]. This intercalation process reduces surface polarity, enhances hydrophobicity, and expands the interlayer spacing, thereby improving the structural and physicochemical properties of the material.

In recent years, considerable effort has been devoted to developing OVMT using different types of surfactants [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Among them, long-chain quaternary ammonium salts (e.g., C14, C16, and C18 alkyltrimethylammonium bromides) have been widely used as effective intercalation agents because they exhibit strong affinities toward the negatively charged VMT layers and efficiently expand the basal spacing while increasing hydrophobicity [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In particular, hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA-Br), as a representative long-chain quaternary ammonium salt, possesses a well-defined molecular structure and strong interlayer binding capability [12,13]. Its ability to form ordered organic bilayers in VMT galleries makes it one of the most effective organic cations for producing high-performance OVMT. Beyond these conventional ammonium surfactants, gemini surfactants and ionic-liquid-based cations have also been explored for promoting stronger intercalation and achieving improved organophilicity [14,15,16].

Despite recent progress in the organic intercalation of VMT, most existing methods remain constrained by long processing durations, often requiring continuous operation for several hours or even several days [17,18,19,20,21]. These procedures are also associated with high energy consumption, making them difficult to implement in large-scale and energy-efficient production. Queiroga et al. [17] employed ethylenediamine to modify VMT under different conditions using a full 24 factorial design, thereby systematically evaluating the effects of temperature, reagent concentration, reaction time, and acid activation on the intercalation behavior. However, the intercalation process in this study required 24–48 h of continuous treatment to achieve structural modification. Likewise, Tuchowska et al. [18] reported the preparation of organo-modified VMT for arsenic removal, but this method involved a one-day conditioning step, indicating that organo-vermiculite (OVMT) synthesis remains time-consuming and difficult to scale up. Wang et al. [20] modified VMT using HDTMA-Br under high-temperature conditions of around 80 °C. Although the elevated temperature reduced the preparation time to 2 h, the process still requires continuous heating, which introduces inherent drawbacks such as increased operational complexity and stricter equipment requirements. Moreover, this synthesis duration is still not particularly short compared with other conventional intercalation methods. In summary, existing OVMT synthesis routes are still constrained by long reaction durations and considerable procedural complexity. Although some improved techniques can accelerate the modification process [9,20], their reaction durations remain relatively long, and the procedures are not always suitable for practical engineering implementation. Therefore, developing a novel preparation method that is both rapid and suitable for large-scale implementation is of considerable research importance.

In this study, a novel ball-milling method is proposed to achieve rapid organic intercalation of VMT using hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA-Br) as the intercalation regent. By combining chemical intercalation with mechanical activation, the OVMT was successfully synthesized within 15 min at room temperature (25 °C). In addition, the process requires no external heating, controlled atmosphere, or other special reaction conditions, further highlighting its operational simplicity. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis showed that the basal spacing increased from 1.46 nm to 4.51 nm, indicating complete intercalation of HDTMA-Br molecules. Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) further confirmed the successful incorporation of HDTMA-Br into the interlayer galleries. Nitrogen adsorption measurements demonstrated that OVMT possesses a more hydrophobic pore structure, as evidenced by a decrease in BET surface area from 7.86 m2·g−1 to 3.81 m2·g−1 and an increase in average pore diameter from 10.8 nm to 14.0 nm after intercalation. To the best of our knowledge, this rapid, ball-milling-based organic intercalation of VMT has not been previously reported. The proposed preparation method provides a solvent-free and energy-saving route for producing organic–inorganic layered silicate materials and is particularly suitable for large-scale application in wastewater treatment.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

HDTMA-Br was purchased from Shanghai LingFeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. VMT with a cation exchange capacity (CEC) value of 74 mmol/100 g was supplied by Dongping Mining Structural Materials Plant (Shijiazhuang, China). Its chemical composition is listed in Table 1. Silver nitrate (AgNO3, analytical reagent grade) was used as precipitant. All other reagents were analytical grade and used as received without additional purification.

Table 1.

Composition of VMT.

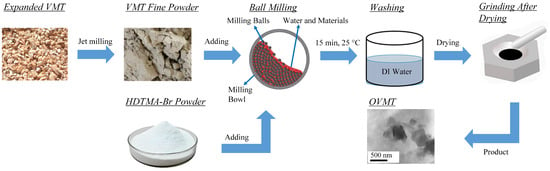

2.2. Sample Preparation

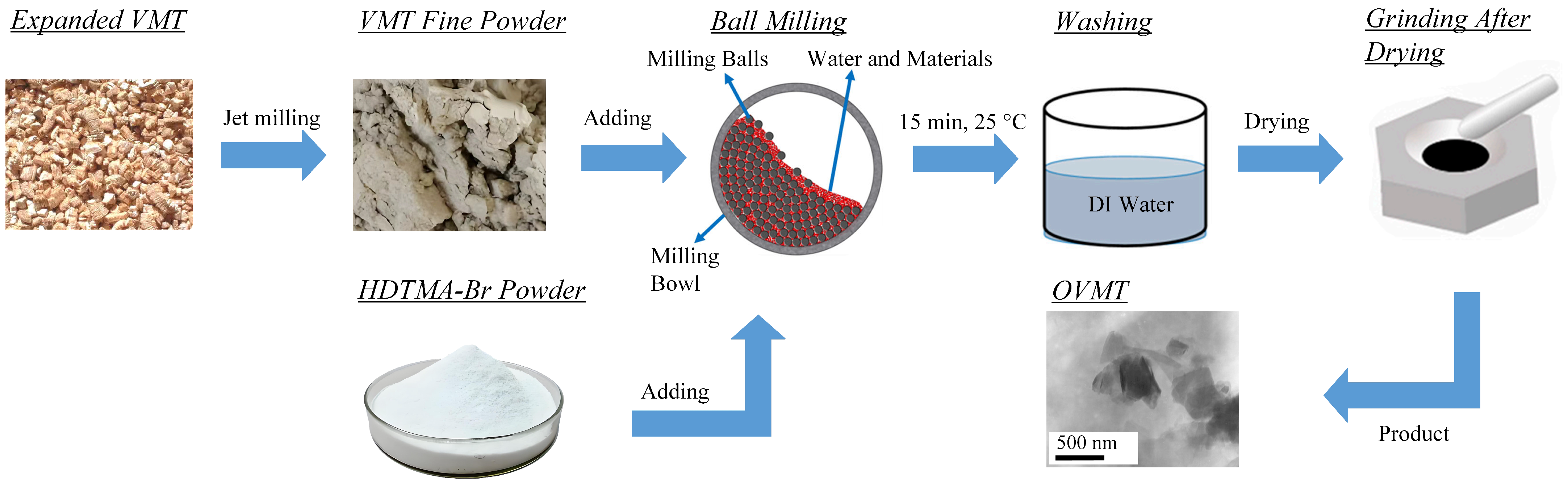

The raw VMT used in this study consisted of coarse granular particles with typical sizes of approximately 2–3 mm, as visually inspected. To obtain a fine powder suitable for intercalation, the material was first ground using an airflow pulverizer (Model QS50, Shanghai Chemical Machinery No. 3 Factory, Shanghai, China). Approximately 30 g of VMT and 8.1 g of HDTMA-Br (equivalent to 1 CEC) were dispersed in 200 mL of deionized water under constant stirring to form a homogeneous suspension. The suspension was subsequently subjected to planetary ball milling (Model QM-ISP2, Nanjing University Instrument Plant, Nanjing, China) at a rotational speed of 450 r/min for 15 min. A schematic diagram of the preparation procedure is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedures for preparing OVMT.

After milling, the resulting slurry was washed several times with deionized water until no precipitation was observed in the filtrate when tested with 0.1 M AgNO3 solution. This purification procedure ensured the removal of unreacted HDTMA-Br and enhanced the chemical purity of the intercalated product, which is essential for avoiding interference in subsequent analyses. The purified solid was then dried and gently ground to obtain the OVMT powder for characterization. Following intercalation and mechanochemical treatment, the resulting product passed through a 325-mesh sieve, corresponding to a particle-size range of approximately 44–5 µm. It is important to note that although washing and oven drying improve analytical precision in laboratory studies, these steps are not essential for large-scale or engineering applications. In large-scale implementation, the milled material would only need to be filtered to remove excess water and allowed to air-dry under ambient conditions. Consequently, the overall process remains energy-efficient despite the laboratory purification steps performed for characterization purposes.

2.3. Sample Characterization

XRD analysis was performed on a diffractometer (Rigaku D/max, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu K radiation ( = 0.154 nm) operated at 40 kV and 200 mA. The scans were conducted in the 2 range from 1.2 to 10° at a rate of 2°/min.

FTIR (KBr pellet, NICOLET 5SXC, Thermo Nicolet, Madison, WI, USA) was employed to analyze the composition of the OVMT. TEM observations were carried out using a transmission electron microscope (Model JEM-2100, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV to examine the microstructure, lamellar morphology, and particle-size evolution of VMT and OVMT. Samples were ultrasonically dispersed in ethanol and dropped onto carbon-coated copper grids prior to imaging. TGA (SDT Q600, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) was employed to study the thermal weight loss in the temperature range of 25–1000 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. XRD Analysis

VMT is a product of the weathering of phlogopite (or biotite) and is composed of a mixture of VMT, phlogopite and hydrobiotite, rather than being a pure mineral [22,23,24].

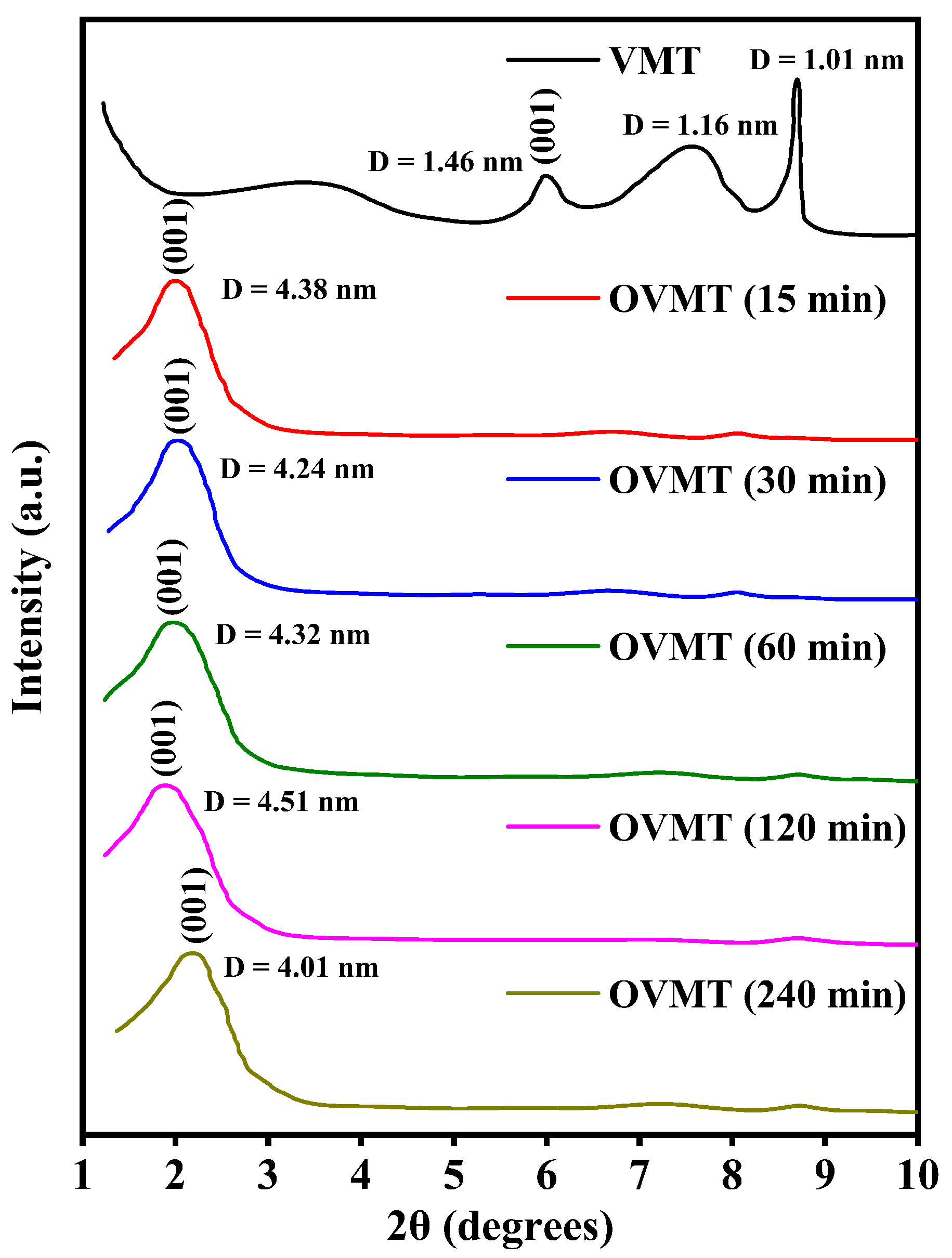

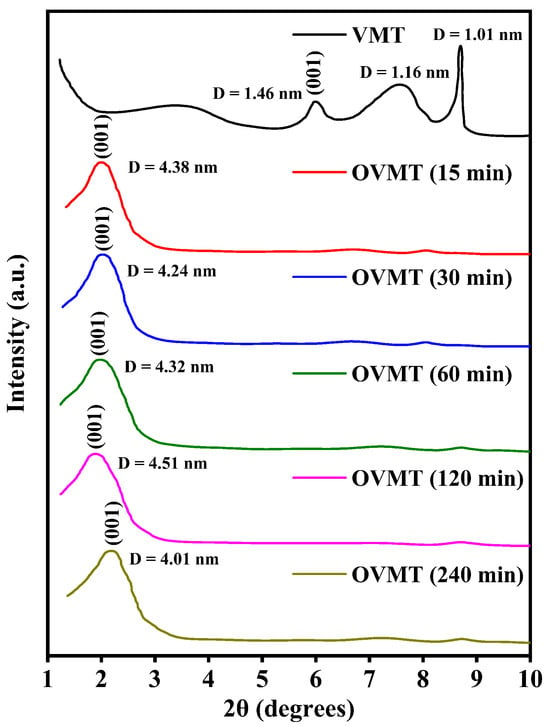

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of VMT and OVMT after ball milling for different durations (15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 120 min and 240 min). The characteristic diffraction peak of for VMT appears at 5.9°, corresponding to a basal spacing of 1.46 nm. Hydrobiotite exhibits a peak at approximately 7.5°, corresponding to a basal spacing of 1.16 nm, while phlogopite shows a basal spacing of 1.01 nm. This is consistent with the known mineralogical composition of naturally weathered VMT [25]. After the intercalation treatment, the XRD patterns reveal a pronounced shift of the VMT (001) reflection toward lower 2 values. This shift reflects a substantial expansion of the basal spacing caused by the intercalation of long-chain HDTMA-Br cations into the interlayer galleries. Importantly, the peak positions and intensities of phlogopite and hydrobiotite remain nearly unchanged after ball milling, indicating that these mineral phases retain their structural integrity and that the intercalation process selectively affects the vermiculite layers. The basal spacing () of OVMT increases progressively with milling time and reaches 4.51 nm after 120 min, representing an exceptionally large interlayer distance exceeding previously reported values for OVMT systems [18,25]. Remarkably, even after only 15 min of ball milling, the basal spacing already expands to 4.38 nm, demonstrating the rapid intercalation kinetics and high efficiency of the mechanochemical process.

Figure 2.

The XRD patterns of VMT and OVMT.

3.2. FTIR Analysis

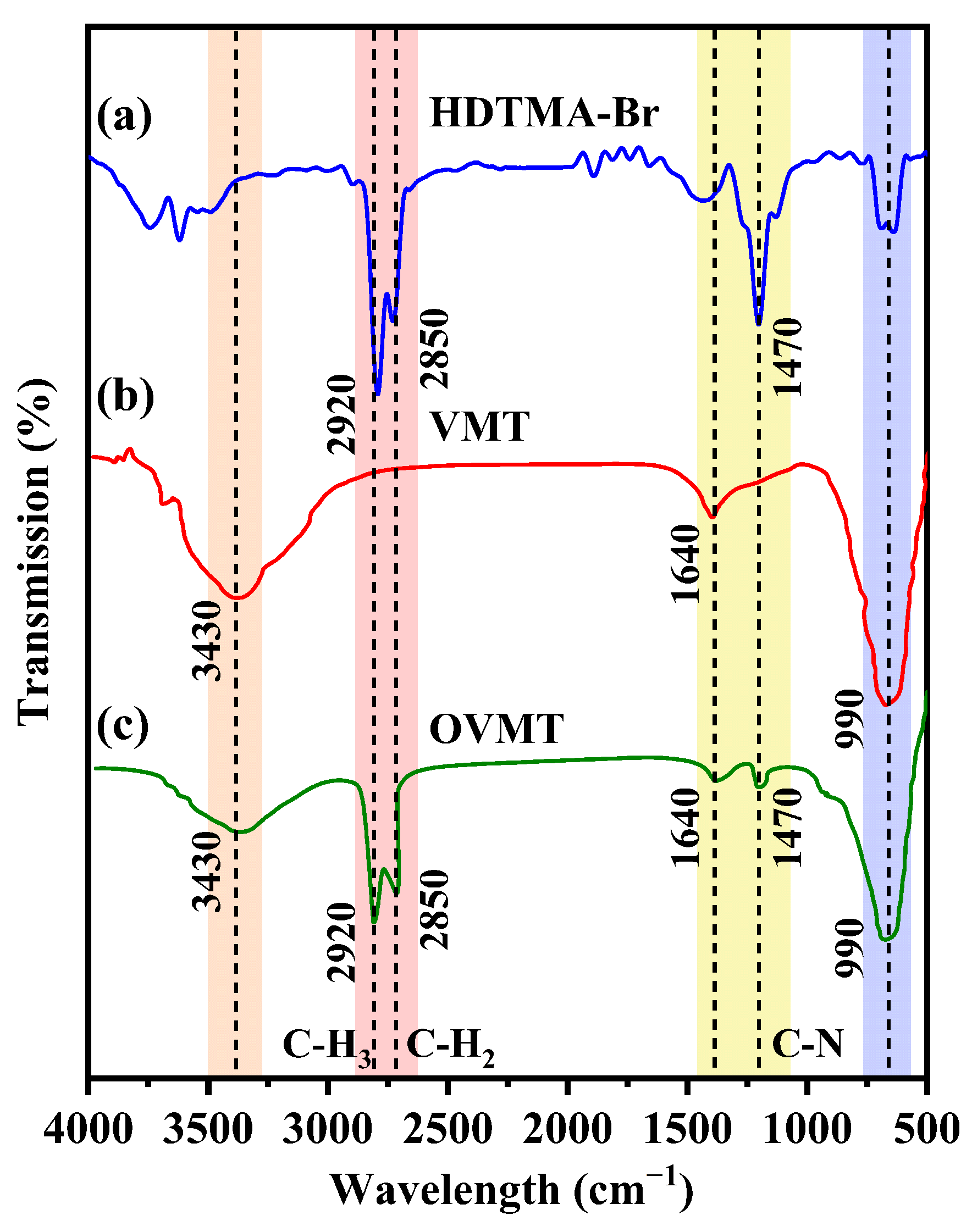

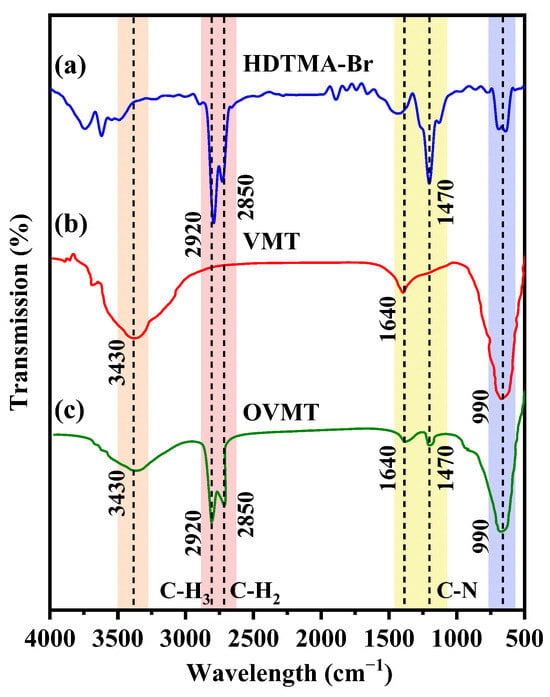

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of pure HDTMA-Br, pristine VMT, and the OVMT sample synthesized by the ball-milling process with a reaction duration of 15 min, where the characteristic absorption bands of each component are highlighted for comparison.

Figure 3.

The FTIR patterns of (a) HDTMA-Br, (b) VMT, and (c) OVMT.

For HDTMA-Br, the spectrum displays two strong C–H stretching vibrations at 2920 cm−1 (asymmetric –CH3 stretch) and 2850 cm−1 (symmetric –CH2 stretch), as well as a characteristic band at 1470 cm−1 assigned to the quaternary ammonium cations of HDTMA-Br. These peaks represent the typical infrared features of long-chain alkyltrimethylammonium salts.

VMT exhibits characteristic hydroxyl and silicate vibrational features. The broad band at 3430 cm−1 is assigned to the O–H stretching vibration of hydrogen-bonded interlayer water molecules, while the peak at 1640 cm−1 corresponds to the H–O–H bending mode of interlayer water. A pronounced band near 990 cm−1 originates from in-plane Si–O stretching vibrations in the tetrahedral sheets, which is typical of layered phyllosilicate minerals.

After modification, the OVMT spectrum retains the fundamental silicate bands of VMT at 3430, 1640, and 990 cm−1, but also displays three additional organic absorption bands at 2920, 2850, and 1470 cm−1, which correspond to the same characteristic features observed in pure HDTMA-Br. These organic vibrational features clearly demonstrate that the alkyl chains and quaternary ammonium groups of HDTMA-Br were successfully incorporated into the VMT interlayers, confirming the formation of OVMT.

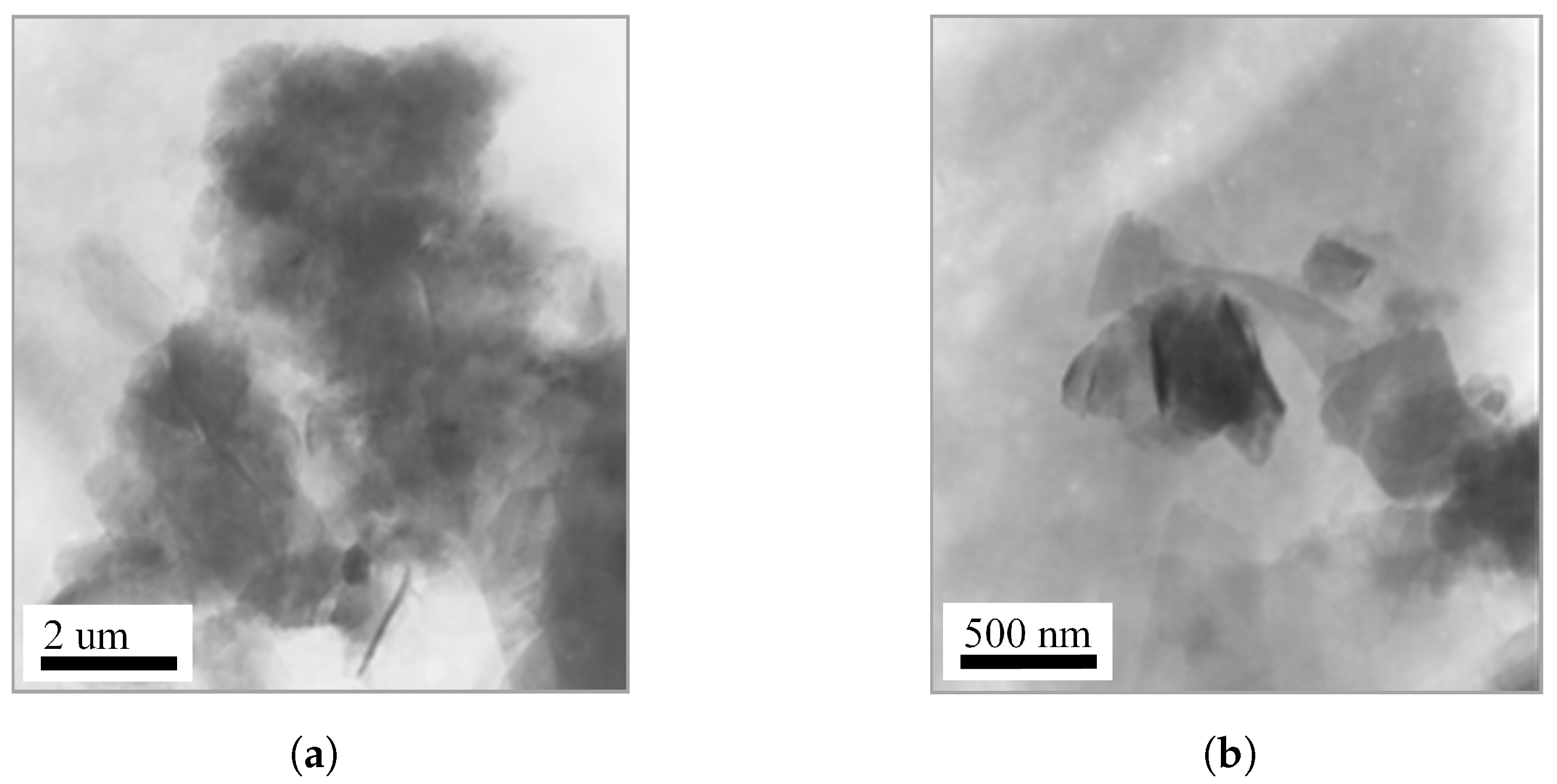

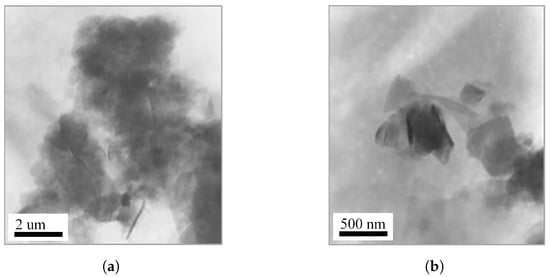

3.3. TEM Analysis

TEM was employed to investigate the microstructural evolution of vermiculite before and after organic intercalation. Figure 4a presents the morphology of pristine VMT, which exhibits large lamellar aggregates with lateral dimensions of approximately 1–2 µm. The silicate layers are densely stacked, reflecting the intrinsic layered architecture and strong interlayer interactions characteristic of unmodified vermiculite. In contrast, the OVMT sample obtained after HDTMA-Br intercalation and subsequent ball milling for 15 min displays pronounced morphological alterations. As shown in Figure 4b, the original stacked lamellae become significantly loosened and partially delaminated, and the particle size is markedly reduced to the range of 200–500 nm. The enhanced layer separation suggests a disruption of the interlayer cohesion, attributable to the penetration of HDTMA-Br molecules into the galleries and the mechanical shearing generated during ball milling.

Figure 4.

TEM images of (a) pristine VMT and (b) OVMT after HDTMA-Br intercalation.

The observed reduction in particle size and the emergence of partially exfoliated lamellae provide direct microscopic evidence for the structural rearrangement induced by the combined chemical–mechanical intercalation process.

3.4. Thermal Analysis

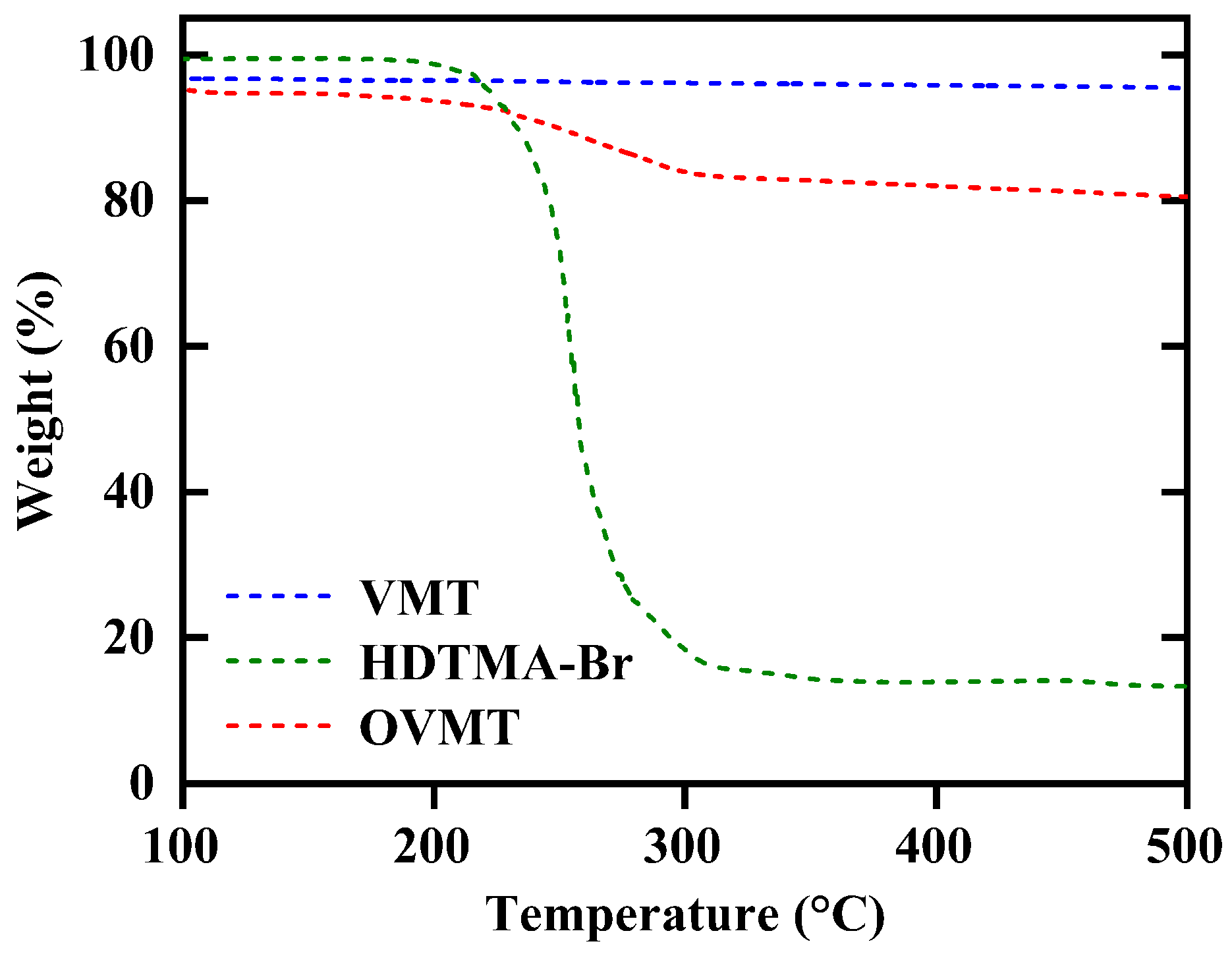

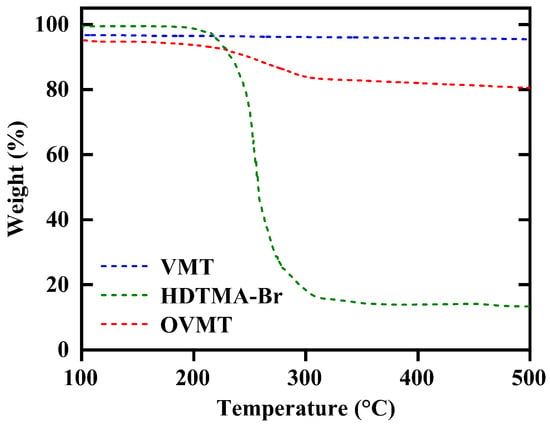

The thermogravimetric curves of HDTMA-Br, VMT and intercalated OVMT (after 15 min of milling) are shown in Figure 5. The weight loss of HDTMA-Br occurs between 180 °C and 320 °C, which corresponds to the thermal decomposition of its alkylammonium chains. For VMT, only a minor mass loss of approximately 3% is observed at low temperatures (<180 °C), attributable to the release of physisorbed and interlayer water.

Figure 5.

The TGA patterns of VMT, HDTMA-Br, and OVMT.

In contrast, OVMT exhibits a clear two-step weight-loss behavior. The initial mass loss between 40 °C and 180 °C arises from moisture desorption, similar to VMT. A pronounced additional weight-loss step of approximately 10% is observed between 180 °C and 320 °C, which aligns with the thermal degradation of the intercalated HDTMA+ organic chains located within the VMT interlayers. This characteristic degradation event is absent in pristine VMT and therefore provides direct thermal evidence for successful incorporation of the quaternary ammonium species.

During the intercalation process, HDTMA+ cations replace the native interlayer cations of VMT (mainly Na+ and Mg2+) through a cation-exchange mechanism. The released Na+ ions combine with Br− to form NaBr in the aqueous phase. However, NaBr is thermally stable up to approximately 747 °C and does not decompose within the temperature range employed in this TGA analysis (up to 500 °C). As a result, no additional mass-loss features related to NaBr formation or decomposition appear in the OVMT thermogravimetric profile. The observed weight loss in the 180–320 °C region can thus be exclusively attributed to the decomposition of the intercalated HDTMA+ species.

3.5. Surface Property Analysis

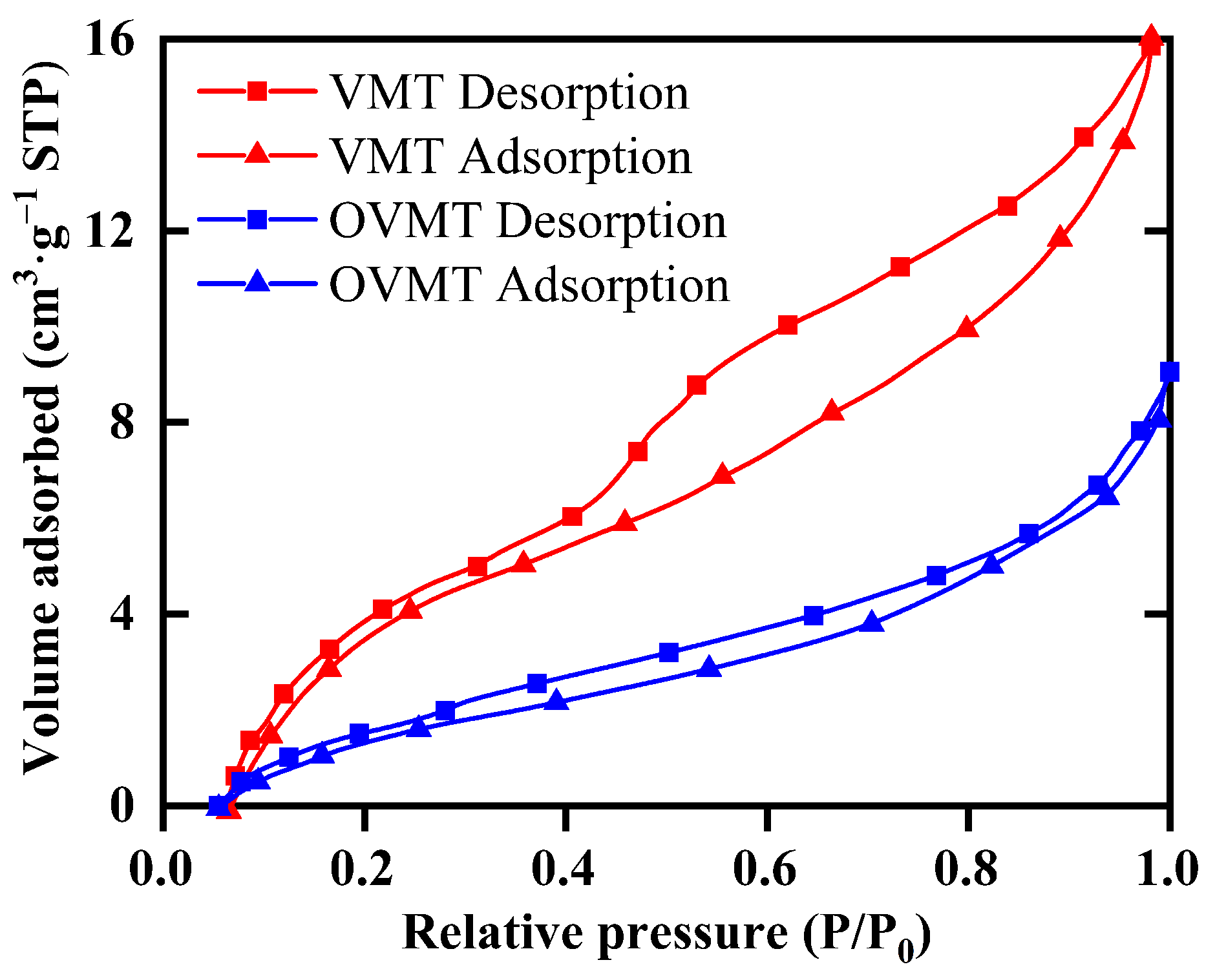

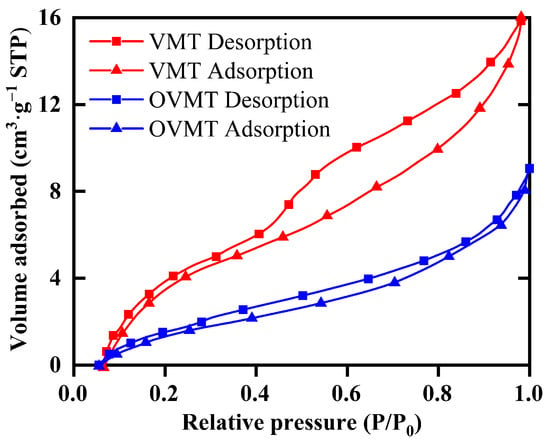

Based on the N2 adsorption data, the specific surface area () was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation, and the pore size distribution was obtained using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model [18]. The corresponding isotherms and textural parameters are summarized in Figure 6 and Table 2.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of VMT and OVMT (15 min).

Table 2.

Textural properties of VMT and OVMT.

Both VMT and OVMT exhibit type IV adsorption isotherms with H4-type hysteresis loops according to the IUPAC classification, which are characteristic of mesoporous materials dominated by slit-like pores formed by stacked lamellar structures [26]. The VMT shows a relatively low BET specific surface area of 7.86 m2·g−1, consistent with its compactly stacked lamellar morphology observed in TEM images in Figure 4b. After HDTMA-Br intercalation and mechanochemical activation, the BET surface area of OVMT decreases to 3.81 m2·g−1. This decrease in surface area is attributed to the partial occupation of interlayer voids by long-chain HDTMA-Br molecules, which reduces the accessibility of N2 adsorption sites. Meanwhile, the average BJH pore diameter increases from 10.8 nm (VMT) to 14.0 nm (OVMT), indicating that intercalation and ball milling induce local expansion of the gallery spacing and partial delamination of the silicate layers. The mesopore volume also decreases from 0.0148 cm3·g−1 to 0.0085 cm3·g−1, consistent with the filling of pore space by intercalated organic cations.

Overall, the nitrogen sorption results indicate that HDTMA-Br intercalation induces a substantial reconfiguration of the pore environment in VMT. The reduction in accessible surface area and mesopore volume suggests that portions of the mineral surface become shielded by the anchored organic chains, while low-polarity domains are introduced within the interlayer region. This alteration diminishes the affinity of the material toward water molecules and simultaneously enhances its interaction with hydrophobic species. As a result, OVMT exhibits improved surface hydrophobicity and stronger affinity toward target contaminants, making it particularly suitable for the adsorption of organic pollutants and heavy-metal ions in wastewater treatment.

3.6. Mechanism Research

VMT is a 2:1 layered silicate, where each crystal layer consists of a magnesium–oxygen octahedron between two silicon–oxygen tetrahedra. Due to chain scission, complementary bonding, and element substitution in the crystal structure, VMT typically carries negative charges on its surface, which attracts various inorganic cations such as K+, Ca2+, Na+ and Mg2+ between the layers. These cations can be exchanged by the organic cations in the high-concentration and high-charge solution, which is the cation-exchange property of VMT. The replacement of Na+ in VMT by HDTMA·Br can be expressed by the following chemical equation [27]:

During the ball milling process, the exfoliation of VMT was enhanced by the strong mechanical power, facilitating the exchange of HDTMA·Br with the inorganic cations in the layers. As a result, organic-intercalated VMT can be synthesized rapidly and efficiently. In just 15 min of ball milling, OVMT with a spacing of 4.38 nm was successfully prepared.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a novel and rapid ball-milling method was successfully developed to OVMT using HDTMA-Br as the intercalation agent. XRD analysis revealed that the basal spacing of vermiculite increased from 1.46 nm to 4.38 nm after only 15 min of milling and further expanded to 4.51 nm with prolonged milling time. FTIR and TGA results confirmed that HDTMA-Br molecules were effectively intercalated into the interlayer spaces of VMT. TEM imaging further revealed partial delamination and a notable reduction in particle size, demonstrating the structural reorganization induced by mechanochemical activation. Moreover, to assess the hydrophobicity of OVMT, nitrogen adsorption measurements were conducted. The results showed a 4.05 m2·g−1 decrease in BET surface area and a 3.2 nm increase in pore diameter, reflecting the formation of a more hydrophobic interlayer environment. With its solvent-free operation, low energy demand, and the markedly enhanced hydrophobic characteristics of the resulting OVMT, the proposed ball-milling strategy provides an efficient route for producing organophilic layered silicates and holds considerable potential for large-scale wastewater treatment applications, particularly for the adsorption of organic pollutants and heavy-metal ions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H. and L.Z.; methodology, L.Z. and X.S.; software, L.Z.; validation, L.Z., B.W. and X.S.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z. and X.S.; resources, W.H.; data curation, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and X.S.; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, W.H.; project administration, W.H.; funding acquisition, W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technical Consulting and Service Project of the Middle Route Source Company of the South-to-North Water Diversion (Grant No. ZSY/YG-SJ(2024)004).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author (Wei Han at hanwei@mail.crsri.cn).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jeon, I.Y.; Baek, J.B. Nanocomposites derived from polymers and inorganic nanoparticles. Materials 2010, 3, 3654–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaya, F.; Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Handbook of Clay Science, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 978-0-08-044183-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.X. Research on the structural characteristic of HDTMA-vermiculite. Earth Sci. Front. 2001, 8, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre, M.; Dubois, P. Polymer-layered silicate nanocomposites: Preparation, properties and uses of a new class of materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2000, 28, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Liu, J.H.; Gates, W.P.; Zhou, C.H. Organo-modification of montmorillonite. Clays Clay Miner. 2020, 68, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Sun, H.; Peng, T.; Zhang, Q. Transformation process from phlogopite to vermiculite under hydrothermal conditions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 208, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; He, J.; Ya, C.Q. Preparation of phenolic resin/organized expanded vermiculite nanocomposite and its application in brake pad. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 119, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.F.A.; de Mira, P.S.; De Presbiteris, R.J.; Grassi, M.T.; Salata, R.C.; Melo, V.F.; Abate, G. Vermiculite modified with alkylammonium salts: Characterization and sorption of ibuprofen and paracetamol. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 4199–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, D.B.; Silva, A.P.; Osajima, J.A.; Silva-Filho, E.C.; Medina-Carrasco, S.; Orta, M.d.M.; Jaber, M.; Fonseca, M.G. Diclofenac removal by alkylammonium clay minerals prepared over microwave heating. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 48256–48272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N.A.; Batista, L.F.A.; de Mira, P.S.; Miyazaki, D.M.S.; Grassi, M.T.; Zawadzki, S.F.; Abate, G. Modified vermiculite as a sorbent phase for stir-bar sorptive extraction. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1347, 343798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.M.; Qin, J.Y.; He, J.Y. Preparation of intercalated organic montmorillonite DOPO-MMT by melting method and its effect on flame retardancy to epoxy resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Jin, B.; Zhang, B.; Du, H.; Li, Q.; Zheng, X.; Qi, R.; Ren, P. Stabilization of heavy metals in solid waste and sludge pyrolysis by intercalation-exfoliation modified vermiculite. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ologundudu, T.O.; Odiyo, J.O.; Ekosse, G.I.E. Fluoride sorption efficiency of vermiculite functionalised with cationic surfactant: Isotherm and kinetics. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, F.; Norouzbeigi, R.; Velayi, E. Organoclays from acid-base activated vermiculites for oil-water mixture separations. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 262, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, Z. Reviving the Potential of Vermiculite-Based Adsorbents: Exceptional Ibuprofen Removal on Novel Amide-Containing Gemini Surfactants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4841–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, I.; Kumar, P.; Shandilya, P.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, V. Surfactant-Assisted Modification of Adsorbents for Optimized Dye Removal. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 40694–40715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroga, L.N.F.; Soares, P.K.; Fonseca, M.G.; de Oliveira, F.J.V.E. Experimental design investigation for vermiculite modification: Intercalation reaction and application for dye removal. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 126, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchowska, M.; Wołowiec, M.; Solińska, A.; Kościelniak, A.; Bajda, T. Organo-modified vermiculite: Preparation, characterization, and sorption of arsenic compounds. Minerals 2019, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudel, A.; Weidler, P.G.; Schuhmann, R.; Emmerich, K. Cation exchange reactions of vermiculite with Cu-triethylenetetramine as affected by mechanical and chemical pretreatment. Clays Clay Miner. 2009, 57, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. Modified Preparation and Characteristic of Vermiculite as Catalysts Support for Catalytic Pyrolysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Academic Conference on Energy Conservation, Environmental Protection and Energy Science (ICEPE 2021), Dali, China, 21–23 May 2021; pp. 4009–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapi, M.; Sefadi, J.S.; Mochane, M.J.; Magagula, S.I.; Lebelo, K. Effect of LDHs and other clays on polymer composite in adsorptive removal of contaminants: A review. Crystals 2020, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimha, K.P. Vermiculite: Nature’s Versatile Mineral. GeoChron. Pan. 2024, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, R.; Kogure, T. Structural and compositional variances in ‘hidrobiotite’sample from Palabora, South Africa. Clay Sci. 2018, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, C.; Kingston, K.; Laycock, B.; Levett, I.; Pratt, S. Geo-agriculture: Reviewing opportunities through which the geosphere can help address emerging crop production challenges. Agronomy 2020, 10, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y. Preparations of organo-vermiculite with large interlayer space by hot solution and ball milling methods: A comparative study. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 51, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis Neto, P.C.d.; Sales, L.P.B.; Oliveira, P.K.S.; Silva, I.C.d.; Barros, I.M.d.S.; Nóbrega, A.F.d.; Carneiro, A.M.P. Expanded vermiculite: A short review about its production, characteristics, and effects on the properties of lightweight mortars. Buildings 2023, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).