Abstract

The Linxing area on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin is a key area for tight-gas exploration. Here, the He 8 Member is the principal target for reserve growth and gas production. However, accurate prediction of sweet spots remains challenging due to poorly constrained primary controlling factors affecting high-quality reservoirs and their diagenetic densification mechanisms. To address these issues, we integrated data from cores, petrographic thin sections, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and log-facies analysis to conduct refined sedimentary microfacies identification, diagenetic analysis, and quantitative porosity evolution analysis. Results indicate that high-quality reservoirs in the He 8 Member are predominantly controlled by distributary-channel microfacies of a braided-river delta plain. Reservoir densification resulted from destructive diagenesis, primarily intense compaction and multi-phase cementation. Compaction reduced porosity by 18.7% on average (accounting for 60% of the total loss), whereas cementation led to a 11.4% loss (36.5%). Dissolution locally enhanced reservoir quality but was insufficient to reverse the pre-existing tight background, providing a limited porosity increase of approximately 5.6%. This study reveals a depositional-diagenetic coupling control on reservoir quality and establishes a genetic model for tight sandstones, thereby providing a critical theoretical framework for sweet-spot prediction in the Linxing area and analogous geological settings.

1. Introduction

The global shift in the energy consumption structure is driving hydrocarbon exploration toward unconventional strategic resources [1]. As a central component of unconventional natural gas, tight sandstone gas is crucial for ensuring stable and increased gas production [2,3,4]. Such reservoirs are characterized by low porosity and low permeability, with their petrophysical properties being collectively controlled by detrital composition, depositional setting, tectonic activities, and diagenetic processes [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, identifying the primary factors controlling reservoir quality and reliably predicting the distribution of sweet spots constitute key challenges in this field.

The Ordos Basin is one of China’s most significant petroliferous basins. In its central and western regions, exemplified by the Sulige gas field, tight gas exploration and development have achieved notable success and have been systematically studied [9,10,11,12,13,14]. In contrast, the eastern margin is a relatively new exploration frontier. Although the He 8 Member of the Lower Permian Shihezi Formation shows considerable potential, it remains less studied. Previous studies have primarily focused on petrographic characterization, depositional framework establishment, and identification of diagenetic types [14,15,16,17,18], but a systematic analysis of how depositional facies and diagenetic processes control reservoir properties is lacking. As a result, the distribution of high-quality reservoirs remains poorly constrained, and the genetic mechanism of reservoir densification remains unclear, hindering exploration progress.

To address these issues, this study focuses on the tight sandstone reservoirs of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. By integrating wireline logs, mud logging, cast thin sections, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and quantitative pore analysis, this study aims to achieve the following objectives: (1) to clarify the fundamental control of sedimentary microfacies on high-quality reservoir distribution; (2) to quantitatively and semi-quantitatively evaluate the contributions of key diagenetic processes to porosity evolution; and (3) to reconstruct the diagenetic sequence and establish a genetic model for tight sandstone reservoirs. The findings are expected to provide a robust theoretical basis for sweet-spot prediction and exploration strategy formulation in this area and analogous geological settings.

2. Geological Background

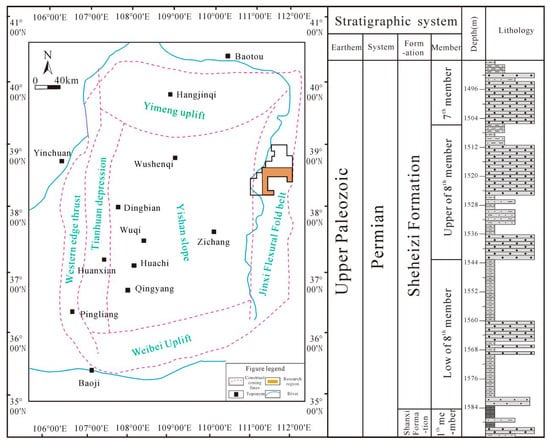

The study area is situated within the northern part of the Jinxi Flexural-Fold Belt along the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, and is structurally characterized by a west-dipping monocline (Figure 1). The Ordos Basin underwent multiple tectonic phases: (1) from the Middle Triassic to Middle Jurassic, southern basin subsidence formed extensive lacustrine systems; (2) during the Late Jurassic, eastern uplift and western marginal compression generated thrust-nappe structures; (3) in the Early Cretaceous, the basin transitioned to an extensional regime; and (4) by the Late Cretaceous, regional compression and uplift culminated in the present structural framework [19,20,21]. These tectonic events created NNE-SSW trending folds and reverse faults within the study area, exerting a first-order control on the deposition and subsequent diagenetic evolution of the He 8 Member reservoirs.

Figure 1.

Structural Location of the Linxing Area in the Ordos Basin and Sedimentary Characteristics of He-8 Member.

The Upper Paleozoic stratigraphic succession in the study area includes, in ascending order, the Benxi, Taiyuan, Shanxi, Lower Shihezi, Upper Shihezi, and Shiqianfeng formations. The target reservoir, the He 8 Member of the Lower Shihezi Formation, is in direct contact with underlying coal-bearing source rocks and is sealed by regionally extensive mudstones. These elements collectively form an effective source-reservoir-seal assemblage [15], providing favorable geological conditions for tight sandstone gas accumulation.

3. Materials and Methods

Well-log data and rock thin sections used in this study were collected from the He 8 Member of the Lower Shihezi Formation in the central Linxing area on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. This dataset comprises well-log information and rock samples from 56 wells.

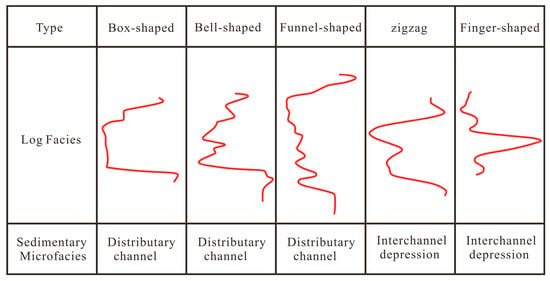

3.1. Identification of Sedimentary Microfacies Based on Log Facies Analysis

Log facies analysis provides a critical bridge between geophysical responses and sedimentological characteristics. Based on established principles of log facies interpretation, this study systematically analyzed the shape, amplitude, contact relationships, and stacking patterns of log curves to identify and classify sedimentary microfacies within the He 8 Member. Previous studies have confirmed that the Lower Shihezi Formation in the Linxing area developed within a braided-river delta plain system [22]. Integrating established log facies models for this depositional environment [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], this study defined the following identification criteria (Figure 2): the braided-river delta plain subfacies typically exhibits log patterns characterized by vertical stacking of multiple box- or bell-shaped curves. The natural gamma ray (GR) curve for the distributary channel microfacies generally displays medium- to high-amplitude, slightly serrated bell or box shapes, forming positive or composite rhythms. In contrast, the interchannel microfacies, characterized by higher clay content, typically show low-amplitude, highly serrated finger-like or zigzag GR curves, which often intercalate with thin sandstone layers exhibiting finger-like log signatures.

Figure 2.

Log facies indicators of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

Guided by these criteria, a systematic interpretation of well-log data across the study area was conducted to delineate the sedimentary microfacies. This work aims to accurately characterize the spatial distribution of sedimentary microfacies in the He 8 Member, thereby establishing a robust foundation for subsequent reservoir analysis.

3.2. Diagenetic Process Identification and Diagenetic Evolution Sequence Analysis

To clarify the key diagenetic processes controlling reservoir quality, this study conducted systematic diagenetic petrographic research. First, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was utilized to determine the mineral composition of the rocks, estimating the mineral content in samples by identifying characteristic peaks in the diffraction patterns. A Zeiss Imager.A1m microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to examine thin sections under plane-polarized and cross-polarized light, focusing on the contact relationships between detrital grains, the types and occurrence of interstitial materials, and the structure and types of pores in the He 8 Member reservoirs. To further elucidate the microscopic characteristics and paragenetic sequence of authigenic minerals, representative samples were examined using an FEI Quanta FEG field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM). This analysis paid particular attention to identifying the crystal morphology, paragenetic relationships, and pore-filling patterns of clay minerals such as kaolinite, chlorite, and illite.

3.3. Quantitative Evaluation of Porosity Evolution

Porosity, permeability, and T2 spectra of 62 samples were measured using a PoroTM300 porosimeter, a Low Perm-Meter, a TSY-1 carbonate content analyzer, and a MesoMR23-60H-I nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) system. The contribution of different diagenetic processes to porosity variation was then quantified [30]. The following parameters were calculated.

- (1)

- Primary porosity: ϕ1(%) = 20.91 + 22.90/S0, where S0 is the sorting coefficient [31];

- (2)

- Post-compaction porosity: ϕ2(%) = C + P1PM/PT;

- (3)

- Porosity loss due to cementation: ϕ3(%) = clay mineral content + C;

- (4)

- Porosity increase from authigenic inter-crystalline pores: ϕ4 = P2PM/PT;

- (5)

- Post-cementation porosity: ϕ5(%) = ϕ2 − ϕ3 + ϕ4;

- (6)

- Porosity increase from dissolution: ϕ6(%) = P3PM/PT.

Here, C is the cement content(%); P1 is the surface porosity of residual primary intergranular pores; P2 is the surface porosity of authigenic intercrystalline pores; P3 is the surface porosity of dissolution pores; PM is the measured average porosity; and PT is the total areal surface porosity. Quantitative analysis of areal porosity was performed through systematic digital image analysis. High-resolution digital images of cast thin sections were captured. Pore domains were subsequently extracted using the ImageJ software package by applying a consistent threshold-based segmentation algorithm. The areal porosity was calculated directly as the percentage of the total area occupied by the segmented pore spaces. To assess measurement uncertainty and ensure statistical representativeness, a minimum of 20 fields of view were analyzed for each sample. The resulting standard deviation of areal porosity measurements was typically less than ±1.5%.

4. Results

4.1. Reservoir Characteristics

4.1.1. Petrographic Characteristics

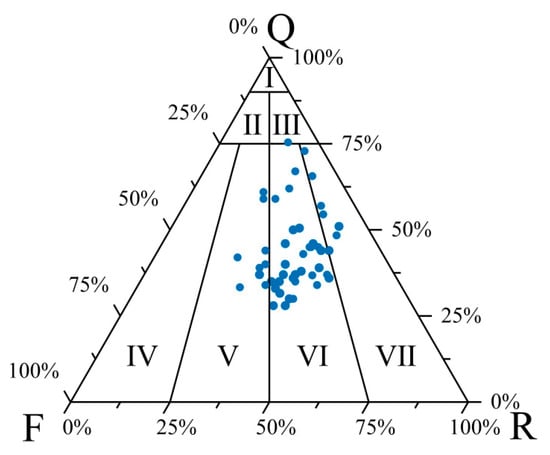

Based on core observation and thin-section analyses from the study area and following the Folk classification scheme for clastic rocks, the tight sandstones of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area are predominantly lithic arkose and feldspathic litharenite, with minor litharenite and lithic quartz sandstone (Figure 3). Statistical analysis of detrital composition reveals that quartz is the most abundant component (avg. 46.7%), followed by rock fragments (avg. 25.4%), with feldspar being the least abundant (avg. 6.23%). The relative content of clay minerals in the He 8 Member is notably high, averaging 14.57%. The clay mineral assemblage is dominated by kaolinite, illite, chlorite, and illite/smectite (I/S) mixed layers, with minor chlorite/smectite (C/S) mixed layers. Textural characteristics show a predominant grain size range of 0.45–1.2 mm. Detrital grain contacts are primarily long, with some sutured contacts and minor point contacts. Grain roundness ranges from angular to subrounded, and sorting is moderate to poor.

Figure 3.

Classification of sandstone reservoirs in the He 8 Member, central Linxing area, Ordos Basin I. Quartz sandstone; II. Subarkose; III. Sublitharenite; IV. Arkose; V. Lithic arkose; VI. Feldspathic litharenite; VII. Litharenite.

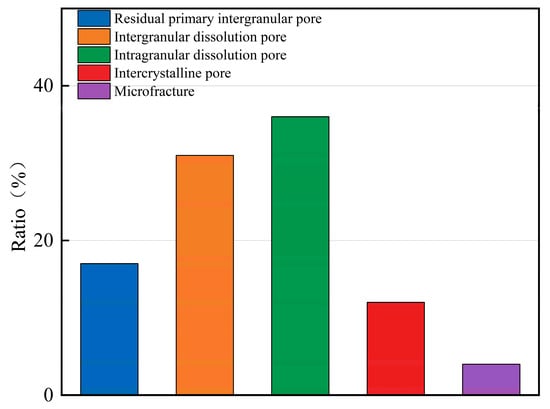

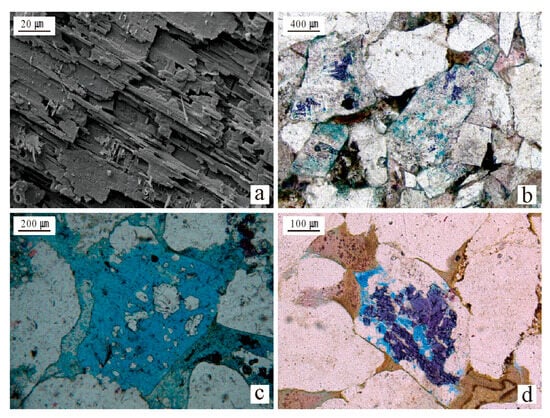

4.1.2. Pore-Scale Characteristics

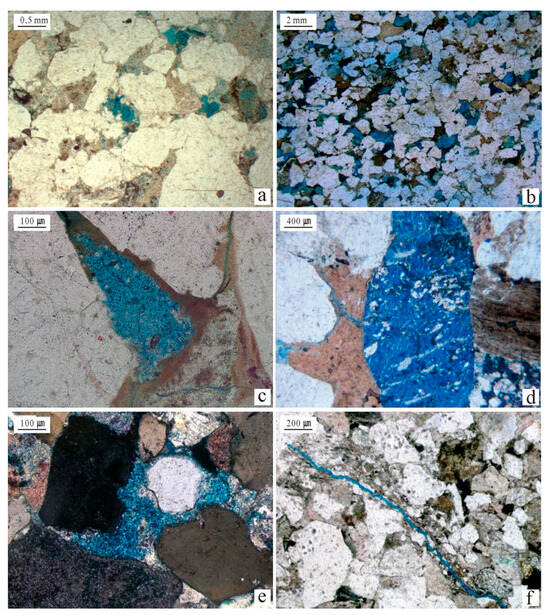

Analysis of cast thin sections and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals the following pore types in the tight sandstones of the He 8 Member (Figure 4): residual primary intergranular pores, intragranular dissolution pores, intergranular dissolution pores, intercrystalline pores, moldic pores, and microfractures (Figure 5). Among these, intragranular and intergranular dissolution pores serve as the dominant storage space. Their formation is attributed to the dissolution of feldspar grains, lithic fragments, interstitial materials, and cements by acidic fluids. Residual primary intergranular pores represent a secondary pore type, primarily formed during the early diagenetic stage and preserved where compaction was not followed by complete pore filling (Figure 5a,b). Intercrystalline pores, which occur mainly between clay mineral aggregates (e.g., kaolinite), also contribute to the storage space. Additionally, moldic pores and minor microfractures are occasionally observed; these microfractures may locally enhance reservoir permeability.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution histogram of reservoir pore types in the He 8 Member, central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

Figure 5.

Pore types of He 8 Member reservoir in central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Intergranular pores (Well L36, 1830.14 m). (b) Intergranular dissolution pores (Well L37, 1703.18 m). (c) Cement dissolution pores (Well L28, 1764.11 m). (d) Feldspar dissolution pores (Well S9, 1696.99 m). (e) Intergranular kaolinite intercrystalline pores (Well S9, 1674.17 m). (f) Microfracture (Well S9, 1676.16 m).

4.1.3. Reservoir Petrophysical Characteristics

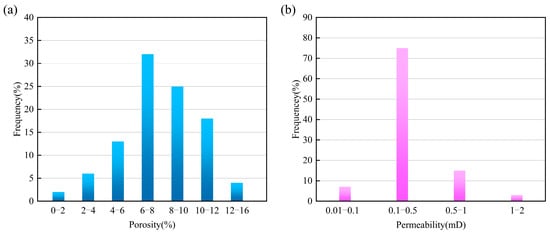

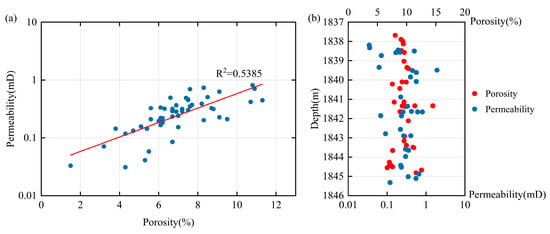

Petrophysical data from 100 samples of the He 8 Member in the study area show that the reservoir porosity ranges from 1.4% to 15.2%, with permeability ranging from 0.03 mD to 1.64 mD. Petrophysical frequency distribution histograms (Figure 6) indicate that porosity is predominantly concentrated in the 4–12% range, while permeability is mainly clustered between 0.1 and 0.5 mD, with samples in these intervals accounting for approximately 75% of the total dataset. The average porosity of the sandstones is 7.01%, overall characterizing a typical tight reservoir with low-porosity and low-permeability attributes. The porosity-permeability cross-plot (Figure 7) demonstrates a positive correlation (R2 = 0.5385). This moderate correlation coefficient, combined with significant data scattering, is characteristic of tight sandstone reservoirs and reflects strong reservoir heterogeneity [32].

Figure 6.

Porosity and permeability frequency distribution histograms of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Porosity frequency distribution histogram. (b) Permeability frequency distribution histogram.

Figure 7.

Porosity-permeability relationship and porosity/permeability versus depth profiles of the He 8 Member reservoirs in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Cross plot showing the porosity-permeability relationship; (b) Distribution of porosity and permeability with depth.

4.2. Sedimentary Facies, Microfacies Types, and Distribution Characteristics

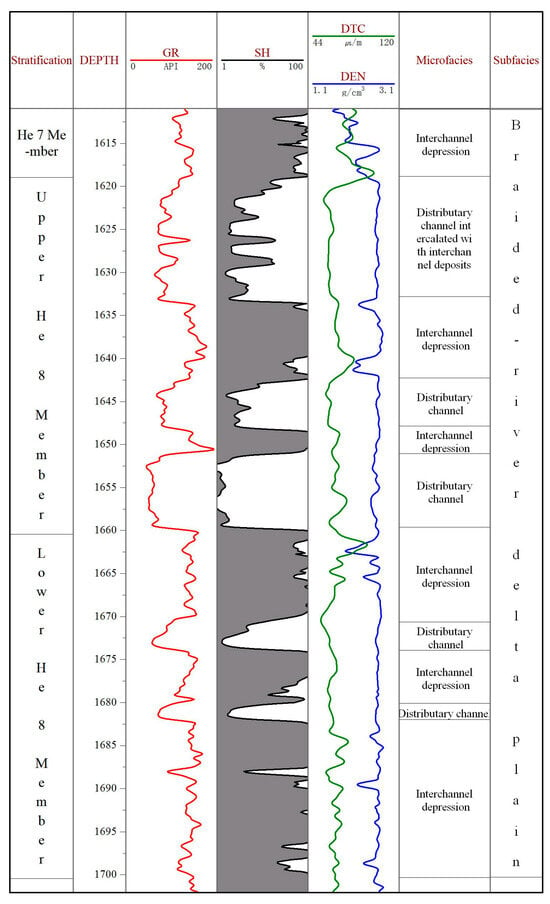

4.2.1. Sedimentary Microfacies Characteristics

Based on log facies analysis of 11 key wells in the study area, integrated with sedimentary indicators including lithology, grain-size distribution, and sedimentary structures, and building upon previous regional sedimentary environment analyses, the He 8 Member in the study area is interpreted as a braided-river delta plain system. Two principal sedimentary microfacies are identified: distributary channels and interchannel deposits. Taking Well L36 in the northwestern part of the study area as an example, the natural gamma ray (GR) log for the distributary channel microfacies displays typical medium- to high-amplitude, box- and serrated bell-shaped patterns, with abrupt upper and lower boundaries (Figure 8). This log facies reflects a channel depositional setting characterized by sufficient sediment supply, strong hydrodynamic energy, and frequent energy variations. Sedimentary rhythms are generally fining-upward or aggradational, and individual sand bodies are usually thick. The interchannel microfacies consists mainly of silty mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, and mudstone, representing deposits of silt and mud transported by floodwaters. The GR log for this microfacies is characterized by medium- to low-amplitude, serrated, or finger-shaped log motifs, mostly showing aggradational rhythms. Due to frequent distributary channel avulsion and erosion of underlying sediments, the interchannel deposits are often incompletely preserved, and individual sand bodies are relatively thin.

Figure 8.

Sedimentary facies characteristics of the He 8 Member in Well L36, northern central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

4.2.2. Distribution Characteristics of Sedimentary Facies

- (1)

- Planar Distribution

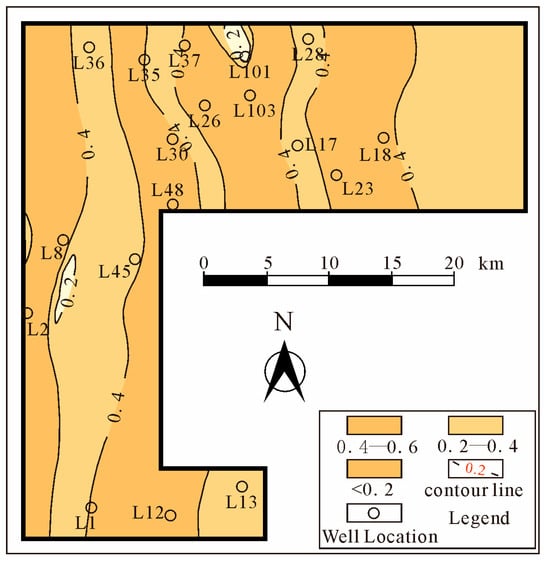

The sand-to-mud ratio serves as an effective indicator for assessing sandbody development, analyzing sedimentary microfacies distribution, and inferring sediment provenance. Differences in its value reflect variations in depositional environment. Based on single-well and multi-well correlations combined with the sedimentary background, a sedimentary facies map of the He 8 Member was constructed (Figure 9), clearly illustrating the spatial distribution of sedimentary facies. The sand-to-mud ratio in the study area ranges from 0 to 0.6. Distributary bays exhibit a ratio of less than 0.2, channel flank deposits range between 0.2 and 0.4, and distributary channels have ratios exceeding 0.4. The main channel systems in the He 8 Member show a predominant north–south orientation, with distributary channels and channel flanks comprising the dominant facies. Due to strong basal scouring by distributary channels and their frequent lateral migration, original distributary bay deposits are rarely completely preserved.

Figure 9.

Sedimentary facies distribution of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

- (2)

- Vertical Distribution

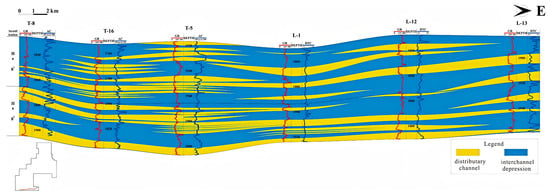

The depositional setting and stacking patterns of sandbodies collectively govern their development scale and spatial architecture. An east–west-oriented cross-section, perpendicular to the paleo-transport direction (Figure 10), demonstrates that distributary channel sandbodies form the primary sandstone framework of the He 8 Member, showing large-scale development and characteristic braided-river depositional features. Vertically, channels exhibit significant inheritance, with multiple stories stacking to form a sand-enveloped-mud configuration. Although individual sandbody thickness is limited, frequent vertical stacking of sandstone lenses attests to multi-phase deposition. Within the vertical succession, the upper part of the He 8 Member displays smaller-scale channel development, thinner channel sandbodies, and poorer lateral connectivity. By contrast, the lower part exhibits better connectivity and larger individual sandbody dimensions. These differences are likely related to temporal variations in hydrodynamic energy and sediment supply during deposition, as well as to frequent lateral migration of distributary channels.

Figure 10.

Sedimentary facies well-tie profile of the He 8 Member in the southern central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

4.3. Diagenetic Processes

The tight sandstones of the He 8 Member in the Linxing area have experienced a complex diagenetic evolution, developing multiple processes including compaction, dissolution, and cementation. These diagenetic processes interact and superimpose upon each other, profoundly modifying the sandstone’s composition, texture, and pore system, thereby ultimately governing the reservoir’s tight characteristics and storage capacity.

4.3.1. Compaction

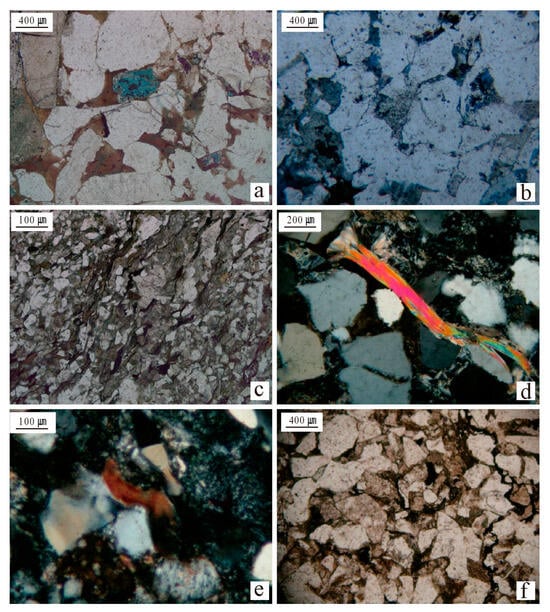

The contact relationships between detrital grains in thin section provide direct evidence for compaction intensity. Systematic examination of cast thin sections from the study area demonstrates that the sandstones of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area experienced intense compaction. The main manifestations include: detrital grains show predominantly long contacts (Figure 11a), with some sutured contacts (Figure 11b) and rare point contacts; grains display a distinct preferred orientation (Figure 11c). Under strong compaction, rigid minerals like feldspar developed microfractures, whereas ductile grains such as mica were bent and deformed (Figure 11d), and were partially altered to siderite (Figure 11e). Furthermore, the clay matrix was compacted and deformed, filling intergranular pores (Figure 11f), which led to substantial destruction of primary porosity.

Figure 11.

Compaction characteristics of the He 8 Member tight sandstone reservoirs in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Long grain contacts (Well L28, 1764.11 m). (b) Long-concave grain contacts (Well L101, 1516.77 m). (c) Tight texture with directionally aligned grains (Well LX28, 1784 m). (d) Deformed mica flake (Well L17, 1695.86 m). (e) Compressed siderite (Well LX17, 1661.2 m). (f) Long grain contacts with clay matrix fill (Well LX101, 1483.79 m).

4.3.2. Cementation

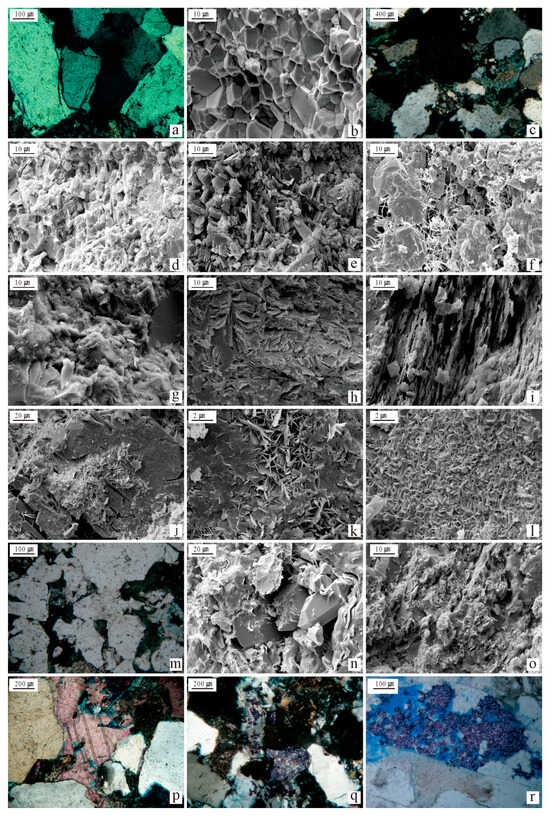

Observations from thin sections and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveal that three main types of cementation occur in the He 8 Member of the Linxing area: siliceous, clay mineral, and carbonate cementation.

- (1)

- Siliceous Cementation

Siliceous cementation manifests mainly as secondary quartz overgrowths and authigenic quartz. Quartz overgrowth is widespread and predominantly grade I–II. Cast thin sections reveal that overgrowths develop on detrital quartz grains, displaying sharp boundaries with the host grains (Figure 12a). Clay rims are occasionally observed separating quartz overgrowths of different phases. SEM images show euhedral authigenic quartz crystals filling interparticle pores; in extensively cemented areas, quartz grains exhibit interlocking, mosaic-like texture (Figure 12b). Although siliceous cementation reinforces the mechanical compaction resistance of the rock framework, it considerably reduces porosity and permeability, thus representing a key factor in reservoir tightness.

Figure 12.

Cementation characteristics of the He 8 Member tight sandstone reservoirs in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Quartz overgrowth (Well L18, 1760.61 m). (b) Intergranular pores cemented by quartz overgrowths (Well L30, 1673.3 m). (c) Intergranular pores filled with kaolinite (Well L17, 1774.9 m). (d) Vermicular and flaky kaolinite filling intergranular pores (Well L7, 1825.42 m). (e) Intergranular pores filled with flaky kaolinite and filamentous illite (Well L28, 1784.37 m). (f) Intragranular dissolution pores formed by feldspar dissolution and filled with filamentous illite (Well L28, 1785.87 m). (g) Feldspar dissolution with filamentous illite coating grain surfaces and flaky mica filling intergranular pores (Well S9, 1680.11 m). (h) Kaolinite altered to filamentous illite, filling intergranular pores (Well L18, 1769.21 m). (i) Feldspar dissolution along cleavages creating intragranular pores and subsequent alteration to illite (Well L18, 1762.81 m). (j) Albite dissolution and overgrowth along cleavages, with intragranular pores filled by filamentous chlorite-smectite (C/S) mixed layers (Well L18, 1760.61 m). (k) Intergranular pores filled with acicular chlorite (Well L28, 1784.37 m). (l) Acicular chlorite coating grain surfaces (Well L18, 1762.81 m). (m) Intergranular pores filled with chlorite (Well L103, 1541.62 m). (n) Intragranular pores filled with filamentous illite, illite–smectite (I/S) mixed layers, flaky kaolinite, quartz overgrowths, and albite (Well L18, 1760.61 m). (o) Dissolution pores formed by calcite dissolution and subsequently cemented by filamentous illite and chlorite-smectite (C/S) mixed layers (Well L71, 1802.16 m). (p) Intergranular pores showing calcite cementation and subsequent calcite dissolution (Well L17, 1677.43 m). (q) Siderite and calcite (Well L17, 1723.94 m). (r) Ferroan calcite (Well L8, 1787.32 m).

- (2)

- Clay Mineral Cementation

An integration of thin-section petrography, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals that the clay minerals in the He 8 Member of the Linxing area mainly comprise chlorite, kaolinite, illite, illite/smectite (I/S), and chlorite/smectite (C/S) mixed layers, with pore-filling and pore-lining being the dominant cementation styles. Kaolinite is the most abundant clay mineral in the study area. It predominantly precipitated from the dissolution of feldspars or volcanic rock fragments within an acidic and confined geochemical system. Under a microscope, kaolinite typically appears as vermicular or book-like aggregates occluding intergranular pores (Figure 12c). SEM observations confirm these aggregates, showing well-developed intercrystalline pores between the kaolinite crystals, which constitute a significant microporosity system (Figure 12d). Illite commonly occurs as fibrous or flake-like crystals, bridging or filling intergranular pores (Figure 12e) and feldspar dissolution pores (Figure 12f), or coating grain surfaces (Figure 12g). Illite has multiple origins: (1) transformation of kaolinite in K-rich environments (Figure 12h), where K-feldspar dissolution by acidic fluids releases K+(4-1), Equation (1); (2) illitization of smectite during the middle to late diagenetic stages, typically occurring at elevated temperatures (70–100 °C or higher in deeper burial) and requiring a K+ source; and (3) direct alteration of K-feldspar to illite in closed to semi-closed systems with sufficient K+ availability. SEM images document feldspar altering to illite along cleavage planes (Figure 12i), with hair-like illite crystals projecting into feldspar dissolution pores (Figure 12j). Chlorite typically occurs as spherical aggregates filling intergranular pores (Figure 12k), or more commonly, forming grain-coating rims (Figure 12l). In thin sections, chlorite appears as pore-lining rims that inhibit quartz overgrowth and preserve porosity (Figure 12m). I/S mixed layers typically exhibit a honeycomb or fibrous morphology, coating grains and filling pores (Figure 12n). C/S mixed layers less commonly occur as leaf-like particles, sometimes observed filling secondary pores such as those after calcite dissolution (Figure 12o).

3Al2SiO2(OH)4 + 2K+ → 2KAl3SiO10(OH)2 + 2H+ + 3H2O

- (3)

- Carbonate Cementation

Thin-section petrography and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) indicate that the carbonate cements in the He 8 Member are predominantly calcite and ferroan calcite, with minor ferroan dolomite and siderite. The primary cementation modes are basal and pore-filling. Thin-section observations reveal that calcite and ferroan calcite occlude intergranular pores or partially to completely replace detrital grains, with local dissolution remnants (Figure 12p,r). SEM analysis further shows calcite commonly associated with clay minerals, notably illite. Siderite typically occurs as brownish, microcrystalline aggregates filling primary intergranular pores (Figure 12q), suggesting an early diagenetic origin.

4.3.3. Dissolution

Analysis of cast thin sections and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) shows that dissolution constitutes the key constructive diagenetic process for reservoir quality enhancement in the He 8 Member. Dissolution pores are predominantly derived from feldspars, with minor contributions from lithic fragments and clay minerals. This process primarily generates intergranular and intragranular dissolution pores. SEM reveals feldspar dissolution along cleavage planes (Figure 13a). The intensity evolved from minor dissolution during eodiagenesis to extensive (Figure 13b), sometimes complete, dissolution during mesodiagenesis, creating moldic pores (Figure 11c). However, parts of the newly formed secondary porosity were subsequently occluded by carbonate cements, including calcite (Figure 13d) and ferroan calcite (Figure 12r). Conversely, SEM also shows instances where calcite cement itself was dissolved, with the resulting pore space later filled by authigenic clay minerals, such as illite or chlorite/smectite (C/S) mixed layers (Figure 12o).

Figure 13.

Dissolution characteristics of the He 8 Member tight sandstone reservoirs in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Feldspar dissolution along cleavages (Well L101, 1517.86 m). (b) Slight dissolution of feldspar grains (Well S9, 1676.16 m). (c) Intragranular dissolution pores in feldspar grains (Well L101, 1514.43 m). (d) Intragranular dissolution pores in feldspar, partially filled by calcite (Well L48, 1842.93 m).

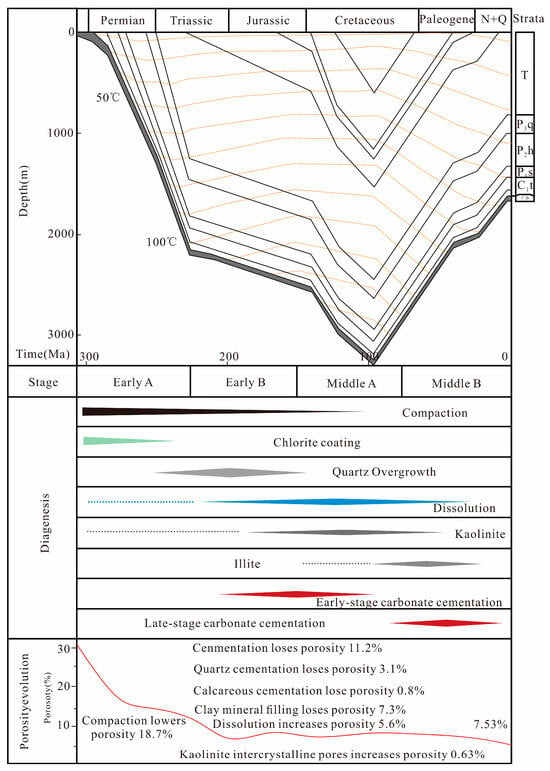

4.4. Quantitative Pore Evolution Characteristics

Quantitative evaluation of porosity evolution (Table 1) indicates a primary porosity of 31.2% for the medium- to coarse-grained sandstones of the He 8 Member in the Linxing area. Compaction was the primary cause of porosity reduction, destroying 18.7% of porosity (accounting for 60% of the total loss). Cementation further reduced porosity by an average of 11.2% (contributing 35.9% to the total loss). Among the cementation types, clay mineral cementation was the most significant, reducing porosity by 7.3% on average, followed by siliceous (3.1%) and calcite cementation (0.8%). In contrast, the intercrystalline pores of kaolinite provided a minor positive contribution, increasing porosity by approximately 0.63%. Dissolution, the principal constructive process, enhanced porosity by an average of 5.6%.

Table 1.

Quantitative porosity evolution data of the He 8 Member sandstones in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Controlling Factors of Reservoir Development

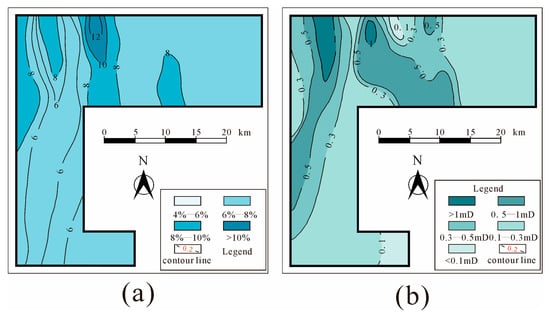

5.1.1. Depositional Microfacies Control on Reservoir Scale and Distribution of Favorable Reservoirs

Synthesis of previous work indicates that depositional microfacies control the spatial distribution of reservoir quality and favorable zones in the He 8 Member by governing sandstone geometry, grain-size distribution, and connectivity [33]. Integration of well-log interpretations with facies and petrophysical maps (Figure 9 and Figure 14) demonstrates that distributary-channel sandstones possess significantly higher porosity and permeability than those deposited in channel margins and interdistributary bays. The high-energy conditions of distributary channels deposited medium- to coarse-grained sandstones with superior initial porosity, which provided essential pore space for later diagenetic fluids and forms the foundation for high-quality reservoir development. In contrast, the fine-grained, clay-rich sediments of interdistributary bays exhibit poor initial petrophysical properties and connectivity, offering limited potential for reservoir enhancement.

Figure 14.

Petrophysical property distribution of the He 8 Member reservoirs in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. (a) Porosity distribution of the He 8 Member reservoirs. (b) Permeability distribution of the He 8 Member reservoirs.

The sandstones of the He 8 Member are dominated by north–south-trending distributary channels and their associated flank deposits, which form the principal reservoir intervals. The lower He 8 submember comprises thicker, more laterally continuous sandstone bodies with enhanced connectivity, whereas the upper submember features smaller, more isolated sandstones. Consequently, favorable exploration targets are predicted in continuous distributary-channel and flank zones characterized by a high sand-to-gross ratio (>0.4) and sand thickness exceeding 20–35 m, particularly in the lower submember. Areas dominated by interdistributary bays, typically with a sand-to-gross ratio of less than 0.2, are considered non-prospective.

5.1.2. Diagenesis Controls the Reservoir Densification Process and Limited Porosity Enhancement

Diagenesis is the decisive factor controlling reservoir quality and strong heterogeneity in the He 8 Member. The quantitative porosity evolution (Section 4.4) demonstrates that intense compaction was the primary cause of the rapid reduction in primary porosity and the initial reservoir densification. Subsequent multiphase cementation (including siliceous, carbonate, and clay mineral cements) further clogged pore throats and was the key process leading to the final, tightly cemented reservoir state [34,35]. In contrast, dissolution served as the principal constructive process, with the secondary pores it created forming the majority of the effective pore space. However, the extent of dissolution was limited by the pre-existing, compacted diagenetic environment, and some of the newly formed secondary pores were subsequently infilled by later cements. Consequently, the porosity-enhancing effect of dissolution was overwhelmingly offset by the porosity-destructive processes of compaction and cementation, ultimately resulting in the characteristic low-porosity and low-permeability reservoir.

5.2. Diagenetic Evolution and Genetic Mechanism of the Tight Sandstone Reservoirs

5.2.1. Diagenetic Evolution Sequence

Following the CNPC (China National Petroleum Corporation) standard for diagenetic stage division of clastic rocks and integrating previous research on the Shihezi Formation in the Linxing area, the He 8 Member is determined to be in the middle diagenetic stage B. Supporting this assignment are the following data: fluid-inclusion homogenization temperatures range from 110 to 144.7 °C [36]; vitrinite reflectance (R0) values vary between 0.90% and 1.83%, averaging 1.28%; and illite–smectite (I/S) mixed-layer clays are in the ordered zone, with an average smectite layer proportion of 12.12% [37,38]. Petrographic observations reveal a predominance of long and sutured grain contacts, the presence of authigenic quartz and quartz overgrowths (typically grade II), authigenic carbonates dominated by calcite and ferroan calcite, and a clay mineral assemblage of kaolinite, illite, chlorite, and illite–smectite (I/S) mixed layers. The pore system is dominated by secondary dissolution pores, with subsidiary residual intergranular pores.

Building upon this diagenetic stage determination and through systematic petrographic analysis of mineral paragenesis, grain contacts, and diagenetic product relationships, the diagenetic sequence of the He 8 Member is reconstructed as follows (Figure 15): Intense mechanical compaction commenced first, transforming initial point contacts into long and sutured types. The formation of chlorite grain-coats postdated this major compaction, as evidenced by their absence at grain-to-grain contacts. Siderite, occurring as intergranular bands/aggregates, formed contemporaneously or shortly after, from the alteration of biotite in an early alkaline pore fluid. Subsequent precipitation of pore-filling calcite was followed by a major phase of feldspar dissolution, which created secondary porosity and supplied silica for later quartz overgrowths. This dissolution phase preceded the formation of vermicular kaolinite, which is observed to fill spaces outside the chlorite coats, and also occurred before significant quartz overgrowth, which is notably suppressed by the presence of chlorite coatings. The final major diagenetic event involved the precipitation of late-stage ferroan calcite, which fills pores adjacent to both chlorite coats and quartz overgrowth rims.

Figure 15.

Burial history of the He 8 Member in the central Linxing area, eastern Ordos Basin.

5.2.2. Tightening Mechanism of the Sandstone Reservoirs

To unravel the dynamic densification process under the coupling of various diagenetic processes, the tightening history of the He 8 Member reservoirs is subdivided into three stages, based on an integration of thin-section observations, quantitative porosity analysis, and hydrocarbon charging history [39].

- Stage I: Early Diagenetic Stage—Intense Compaction and Early Cementation Forming the Tight Foundation

Intense mechanical compaction created a relatively closed, alkaline diagenetic environment with low fluid flux and limited recharge. This environment restricted fluid mobility, causing ions (e.g., Fe3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, SiO2, Al3+) released from unstable grains (feldspar, lithic fragments) to precipitate locally as early cements (e.g., calcite), which occluded intergranular pores. Although pore-occluding, this calcite cementation also acted as a rigid framework that mitigated subsequent compaction and provided soluble material for later acidic fluids [40]. Simultaneously, chlorite grain coatings formed, which enhanced grain-to-grain pressure resistance and significantly inhibited quartz overgrowth, thereby preserving some primary porosity [41,42]. Nevertheless, porosity was drastically reduced by 18.7% during this stage, accounting for 60% of the total porosity loss, resulting in initial reservoir densification.

- Stage II: Middle Diagenetic Stage A—Limited Dissolution Constrained by Ongoing Cementation

At this stage, the underlying Taiyuan and Shanxi Formation source rocks entered the hydrocarbon generation window. Organic acids generated during maturation migrated via faults into the He 8 Member sandstones, triggering dissolution that was most intense for feldspars, with lesser dissolution of early calcite cement and lithic fragments, thereby creating substantial secondary porosity, including intergranular and intragranular dissolution pores. The silica released from feldspar dissolution supplied material for quartz overgrowths. Concomitant kaolinitization of feldspar generated authigenic kaolinite with well-developed intercrystalline pores, contributing a net increase of approximately 0.63% to porosity. Illitization of smectite also progressed during this stage. Thus, dissolution and cementation occurred simultaneously. However, constrained by the pre-existing tight framework, the porosity enhancement from dissolution was both limited in scale and heterogeneous in distribution.

- Stage III: Middle Diagenetic Stage B—Waning Dissolution and Final Tight Reservoir Lock-in

With increasing burial depth and temperature, hydrocarbon generation waned, reducing the supply of organic acids and causing dissolution to cease. The net porosity increase from dissolution throughout the diagenetic history was approximately 5.6%. As the supply of silica diminished, quartz cementation slowed. Diagenesis was subsequently dominated by the transformation of clay minerals: earlier-formed kaolinite and chlorite were progressively converted to illite and illite/smectite (I/S) mixed layers (and minor chlorite/smectite), which further infilled pore spaces, as confirmed by SEM observations. Cementation processes collectively reduced porosity by 11.2%, accounting for 35.9% of the total porosity loss. Through the combined effects of pervasive compaction and multiphase cementation, the reservoir attained its final, tightly cemented state.

Integrated analysis leads to the conclusion that the He 8 Member reservoir was already effectively tight prior to large-scale hydrocarbon charging, demonstrating a characteristic “dense before accumulation” genetic mechanism.

6. Conclusions

This study integrates sedimentological and diagenetic petrographic analyses to systematically unravel the principal controlling factors of reservoir development and the genetic mechanism of densification in the He 8 Member sandstones of the central Linxing area, eastern Ordos Basin. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Depositional microfacies provide foundational control of reservoir distribution. Distributary-channel microfacies are the only effective reservoir facies. The medium- to coarse-grained sandstones deposited in these channels provide the essential material foundation for high-quality reservoirs. Furthermore, the associated thick, well-connected sand bodies act as predominant conduits for later diagenetic fluids, thereby strictly controlling the spatial distribution of “sweet spots.” In contrast, interchannel microfacies, characterized by high clay content, thin sand bodies, and poor initial permeability, possess negligible reservoir potential.

- (2)

- Diagenetic modification is the decisive factor for reservoir quality. Quantitative porosity evolution analysis reveals that intense mechanical compaction is the predominant cause of porosity destruction, reducing porosity by 18.7% on average and accounting for 60% of the total loss. Cementation ranks as the second most significant process, responsible for an 11.4% porosity reduction (36.5% contribution). In contrast, multiphase dissolution serves as the key constructive process, enhancing porosity by approximately 5.6%; however, its effectiveness is spatially constrained by the pre-existing densely compacted framework.

- (3)

- A genetic model of densification is established, affirming a “dense before accumulation” scenario for the He 8 Member. The reservoirs had already reached tight conditions (average porosity < 8%) prior to the main phase of hydrocarbon charging, as evidenced by fluid inclusion data and burial history modeling. Consequently, “sweet spots” are interpreted as the coupled product of favorable depositional facies belts and localized constructive diagenetic alteration.

In summary, future exploration for tight sandstone gas in this area and analogous settings should focus on identifying the distribution of favorable depositional microfacies and, within these trends, targeting intervals exhibiting significant constructive diagenetic overprints. This approach provides a clear strategy for the efficient discovery of unconventional natural gas resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and D.R.; methodology, D.R.; validation F.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z. and D.R.; investigation, T.Z.; data curation, T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.; writing—review and editing, D.R.; visualization, F.Z.; supervision, J.Z. and D.R.; project administration, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Helium Enrichment and Detection in Natural Gas Reservoirs Related to Oil and Gas Fields” (Grant No. 2025ZD1010500), as part of the “Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration—National Science and Technology Major Project”.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author F.Z. and T.Z. were employed by the company CNPC. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zou, C.; Li, S.; Xiong, B.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Pan, S.; Ma, F.; Wang, Z. Concept, Connotation, Pathway and Significance of Total Energy System [J/OL]. Acta Petrolei Sinica, 1-20[2025-12-05]. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2128.TE.20250911.1116.002 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Zou, C.; Li, S.; Xiong, B.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Ma, F.; Pan, S.; Guang, C.; Liang, Y.; et al. The connotation, pathways and implications of building an “energy-powerful nation” in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ni, Y.; Wu, X. Tight sandstone gas in China and its significance for exploration and development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, H.; Sun, Q.; Shao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D. Unconventional oil and gas exploration and development theories and technologies enabling increases in China’s reserves and production. Pet. Sci. Technol. Forum 2021, 40, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, A.; Wei, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Meng, W.; Huang, S. Current status and prospects of tight sandstone gas development in China. Nat. Gas Ind. 2022, 42, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Huang, C.; She, Y.; Ju, X.; Zhao, L. Advances in the accumulation theory of tight sandstone gas in China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2016, 27, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zou, C.; Jia, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Guo, Z. Development characteristics and trends of tight oil and gas in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Yu, J.; Xu, L.; Niu, X.; Feng, S.; Wang, X.; You, Y.; Li, T. New advances in tight oil exploration and development and key controls on large-scale enrichment in the Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2015, 20, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.; Jia, A.; Meng, D.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, X. Efficient development and EOR strategies for large tight sandstone gas fields: A case study of the Sulige gas field, Ordos Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fu, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Cao, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Fan, Y. Accumulation model of quasi-continuous tight sandstone giant gas fields in the Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 33 (Suppl. S1), 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Tao, S.; Yuan, X.; Hou, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, C.; Li, D.; et al. Types, characteristics, mechanisms and prospects of conventional and unconventional hydrocarbon accumulations: A case study of tight oil and tight gas in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 33, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Li, G.; Cui, J.; Huang, F.; Lu, X.; Guo, Z.; Cao, Z. Geological conditions for tight oil and gas formation and exploration prospects in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2025, 46, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Fan, L.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Ji, H. New advances, prospects and countermeasures for natural gas exploration in the Ordos Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2019, 24, 418–430. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, B.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Major advances and scientific issues in deep exploration of China’s petroliferous basins. Earth Sci. Front. 2019, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Yang, S.; He, Q.; Xu, W.; Lin, Q. Conditions for efficient tight sandstone gas accumulation in the Linxing–Shenfu block on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37 (Suppl. S1), 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Huang, W.; Lü, C.; Cui, X. Geochemical characteristics and geological implications of Upper Paleozoic mudstones in the Linxing area of the Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2018, 39, 876–889. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Du, J.; Yang, Q.; Mi, H.; Zhang, S. Breakthroughs and future challenges in deep CBM exploration on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin: A case study of the Linxing–Shenfu block. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Yu, S.; Guo, M. Accumulation conditions and main controlling factors of Upper Paleozoic tight sandstone gas reservoirs in the Linxing block, Ordos Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2021, 42, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D. Advances in structural evolution and paleogeography of the Ordos Basin. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2012, 19, 15–20, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Gui, X.; Yue, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J. Space-Time Coordinate of the Evolution and Reformation and MineralizationResponse in Ordos Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2006, 80, 617–638. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. Compound ancient tectonic system and natural gas of Early Paleozoic in Ordos Basin. J. Geomech. 2002, 8, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Chen, H.; Xiang, F.; Ye, L.; Li, G. Application of trace elements analysis on sedimentary environment environment identification-an example from the Permian Shanxi Formation in eastern Ordos Basin. Xinjiang Geol. 2006, 24, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. Diagenesis of the Shihezi Formation Reservoirs in the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Sedimentary characteristics of braided-river delta of the Shahezi Formation in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression. Miner. Explor. 2019, 10, 756–760. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. Sedimentary Characteristics and Model of Large Shallow-Water Braided-River Deltas. Master’s Thesis, Changjiang University, Jingzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C. Sand-Body Architecture and Distribution of the TIII-1 Sand Unit in the Santamu Oilfield Braided-River Delta Front. Master’s Thesis, Changjiang University, Jingzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Study of braided-river delta facies of the Yingcheng Formation in the Shiwu Oilfield, southern Songliao Basin. West. Explor. Eng. 2016, 28, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, M.S.; Soliman, N.; El-Banbi, A.H. Wellbore storage removal in pressure transient analysis for gas well. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Automatic Identification of Lithology and Sedimentary Microfacies from Logging Curves. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, C. Quantitative analysis of porosity evolution in feldspar-rich coarse clastic sandstones: A case study of Member 2 of the Shahejie Formation, northern Liaodong uplift, Bohai Bay Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2020, 41, 874–883. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, D.C.; Weyl, P.K. Influence of texture on porosity and permeability of unconsolidated sand. AAPG Bull. 1987, 71, 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Wang, X. Relationship between porosity and permeability in different reservoir types. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2014, 33, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. Controlling factors on reservoir development of the Upper Paleozoic He 8 Member in the central Linxing block, Ordos Basin. China Offshore Oil Gas 2018, 30, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Liu, X.; Fu, X.; Li, M. Impacts of petrographic composition and diagenetic evolution on the quality and productivity of tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study of the Upper Paleozoic He 8 gas reservoirs in the Ordos Basin. Earth Sci.—J. China Univ. Geosci. 2014, 39, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, P.; Lin, C.; Zhang, S.; Dong, C.; Wei, M. An overview on study of chlorite films in clastic reservoirs. J. Palaeogeogr. 2017, 19, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, D.; Yu, F.; Ji, H.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Hao, L.; Wei, Z. Diagenetic evolution and quantitative porosity analysis of different grain-size sandstones in the Lower Shihezi Formation, Linxing area, Ordos Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2017, 35, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Hydrocarbon Generation–Expulsion History of Upper Paleozoic Source Rocks and Stages of Natural Gas Accumulation in the Linxing Block, Ordos Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zou, J.; Zhu, Y. Factors influencing the physical properties of tight sandstones in the He 8 Member, Linxing block, Ordos Basin. Geol. J. 2023, 47, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Coupling Between Reservoir Densification and Hydrocarbon Accumulation for Upper Paleozoic Sandstones in the Linxing Area, Ordos Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, L.; Wu, P.; Xu, Y. Lower limits of effective reservoir properties and main controlling factors for the He 7–He 8 Members in the central Linxing area, Ordos Basin. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2024, 31, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Huang, S.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. Effect and protection of chlorite on clastic reservoir rocks. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2004, 31, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, H.; Jia, B.; Yu, J.; Luo, W. Origin of chlorite and its relationship with high-quality tight sandstone reservoirs in the Xujiahe Formation, western Sichuan Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2012, 33, 751–757. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).