Abstract

The effects of Ce2O3 and CaF2 on the microstructure of silicate-based mold flux were investigated using an integrated approach combining molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with viscosity testing, SEM-EDS, and XRD analysis. The structural origin of changes in viscosity and crystallization behavior was revealed. It was found that the joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 to the silicate melt leads to a synergistic effect; CaF2 acts as a diluent within the silicate network, while O2− introduced by Ce2O3 promotes the depolymerization of the complex [SiO4]4− network. As a result, highly polymerized structural units (Q2, Q3, and Q4) transform into less polymerized ones (Q0 and Q1), reducing the overall degree of polymerization and enhancing slag fluidity. Moreover, the preferential formation of [SiO4]4−–Ce3+–F− and [SiO4]4−–Ca2+–F− coordination structures replaces the original [SiO4]4−–Ce3+ and [SiO4]4−–Ca2+ linkages. This structural rearrangement facilitates the formation of low-melting-point phases during cooling, thereby suppressing the crystallization tendency and improving the stability of viscous properties of the mold flux. These findings provide theoretical insight for the design of high-performance fluxes used in rare earth-containing steel continuous casting.

1. Introduction

Trace rare earth (RE) elements in steel can deeply purify molten steel, denature harmful inclusions, improve the steel organization, and enhance various properties of steel, with an irreplaceable and unique micro-alloying role [1,2]. However, the industrial application of such steel still faces serious challenges. A major bottleneck lies in the continuous casting process, which often fails to proceed smoothly when rare earth elements are present [3,4]. During the casting process, rare earth alloys in the mold react to form rare earth oxides that enter the mold flux, deteriorating the slag’s metallurgical properties and sometimes preventing multi-furnace continuous casting.

Several scholars have conducted research on the design and development of mold flux for the continuous casting of these steels. Li et al. [5] proposed that with the increase in RExOy content, the precipitation of a large number of wollastonite, melilite, calcium cerite, and cuspidite phases in the slag caused a sharp increase in the viscosity of the mold flux, which seriously deteriorated the performance of the original slag. A. Wang et al. [6] pointed out that a small amount of rare earth oxides has a beneficial melting effect on the mold flux. When the content of rare earth oxides exceeded 7 wt%, the high-temperature viscosity of the slag increased significantly, and the stability of its high-temperature properties deteriorated. Zeng et al. [7] and Chen [8] proposed, in the design of the rare earth-treated steels mold flux, to try to use raw materials with complex compositions (CaF2, Li2O, MgO, etc.) and to control the amount of a single raw material, which can improve the stability of properties such as the solidification temperature and the viscosity of the protection slag. Yao et al. [9] developed a special mold flux for the continuous casting of RE steels, which overcomes the problem of the stellate cracking of cast billets produced by the conventional mold flux in production and which meets the requirements for producing rare earth-treated steel. The above work has obtained the laws of physical and chemical property changes in the rare earth-containing steel continuous casting slag, which provides a useful reference for the design and development of slag. However, the microscopic endogenous causes of the variation in the physicochemical properties of the rare earth-containing steel mold flux need to be further explored.

In this paper, the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, combined with viscosity testing, SEM-EDS analysis, and XRD analysis, was used to investigate the effects of Ce2O3 and the joint addition of Ce2O3 and CaF2 on the microstructure evolution of slag, and the structural origin underlying the changes in the viscosity and crystallization behavior of the slag was elucidated, which can help to provide theoretical guidance for the development of mold flux with reasonable properties and promote the development of metallurgical technologies related to steels containing rare earth elements.

2. Experiments

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The slag systems with the addition of Ce2O3 and the joint addition of Ce2O3 and CaF2 to CaO-SiO2 slag were designed. In order to unify the number of oxygen particles and the chemistry valence of cations in alkaline oxides, Ce2O3 was measured as Ce2/3O. The specific composition of the experimental slag systems is shown in Table 1. Referring to the phase diagram data [10], the equilibrium temperature of the simulation was set to 1823 K, which ensured that all slag samples were melted.

Table 1.

Composition, atomic number, density, and size in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 systems.

Molecular dynamics simulation techniques were used to resolve the basic parameters of melt structure (bond lengths and coordination numbers) and reveal the basic structural units and degree of polymerization of slag, and its evolutionary patterns. The molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the LAMMPS software, version 22. In the MD simulation, the Buckingham [11] and the Born–Mayer–Huggins (BMH) potential [12] forms were used as the pair potential, as shown in Equations (1) and (2), respectively, where Uij(r) is the interatomic pair potential, qi and qj are the selected charges, rij is the distance between particles i and j, Aij and ρij are repulsive potential parameters, and Cij is van der Waals force parameter. The potential parameters [13,14,15,16] used are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. In the simulation setup, the system was modeled with approximately 4000 particles. The periodic boundary conditions were employed for the basic cells in the NVT ensemble. The integration of the equation of motion was solved with a time step of 0.1 fs by the leapfrog algorithm. The long-range Coulomb forces were evaluated using the Ewald sum method, and the cut-off radius of the short-range repulsive force was set to 10 Å. More details of the MD simulation and the simulation process setup are described in our previous works [17,18,19]. In the simulation process, an appropriate number of atoms of each type were placed in the primary MD cell with a random initial state. At the beginning of the simulation, the initial temperature was performed at 4273 K for 20,000 steps to mix the system completely and eliminate the effect of the initial distribution. Then, the temperature was decreased to 1873 K through 95,000 steps. After the equilibrium calculation, the systems relaxed for another 60,000 steps. Finally, structure information of melts could be calculated and analyzed.

Table 2.

Buckingham potential parameters of particle pairs in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 system.

Table 3.

BMH potential parameters of particle pairs in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 system.

2.2. Physical Experimental Methods

The viscosity of the slag was measured using the rotating cylinder method. Further experimental details can be found in our previous work [20].

SEM-EDS and XRD were used to analyze the phase composition at the turning point of the slag viscosity–temperature curve. To characterize the crystallization evolution during cooling, a 150 g slag sample with identical chemical composition to that employed in molecular dynamics simulations was placed in a graphite crucible and remelted using a laboratory-scale high-temperature quenching furnace. The system was heated at 4–6 K/min to 1823 K and maintained at this temperature for 2 h under an isothermal holding regime. Subsequently, the molten slag was cooled at a controlled rate of 1 K/min to the break temperature identified from the viscosity–temperature profile, after which it was rapidly quenched in ice water without the crucible to preserve the high-temperature structure. An ultra-high-purity argon atmosphere (>99.999 vol%) was maintained throughout the thermal cycle, with a constant flow rate of 1000 mL·min−1 to prevent oxidation. The quenched slag products were finally dried at 383 K for 2 h prior to further microstructural and mineralogical analysis.

Microstructural characterization and elemental analysis of the phases in the quenched samples were performed using scanning electron microscopy equipped with energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS, Regulus8100, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to examination, all samples were subjected to sequential grinding, polishing, and carbon coating procedures to ensure surface conductivity and topographic clarity. Quantitative grain size analysis of the crystalline phases was carried out based on the acquired SEM images using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software, employing grayscale thresholding and morphological filtering for precise phase boundary identification.

Phase identification of the quenched samples was performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Co Kα radiation. Measurements were scanned over a 2θ range of 10° to 90° with a step size of 0.02° per second. Phase identification was accomplished by matching the acquired diffraction patterns with reference phases embedded in the search–match software (DIFFRAC.EVA software (with built-in Search-Match module, version 3.1, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA)).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Effect of Ce2O3 and CaF2 on the Melt Structure of Slag

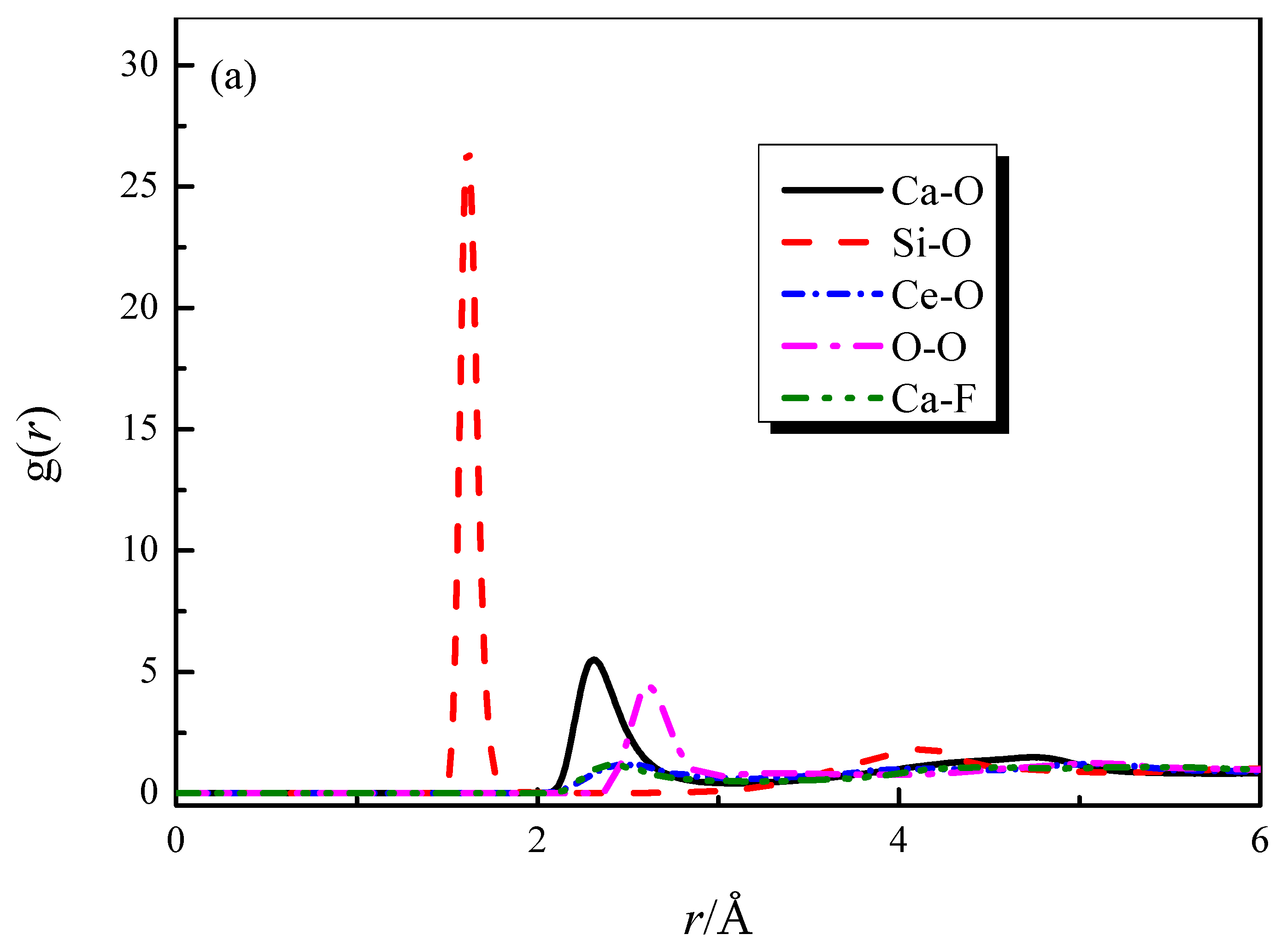

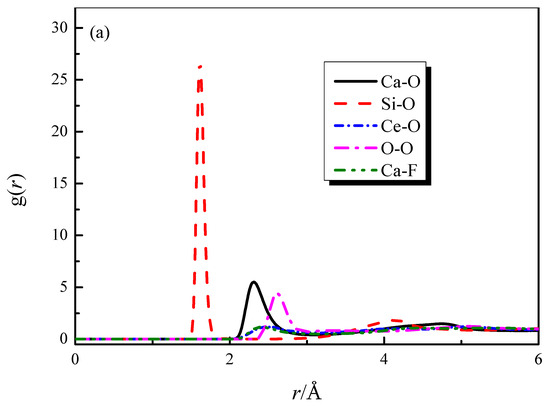

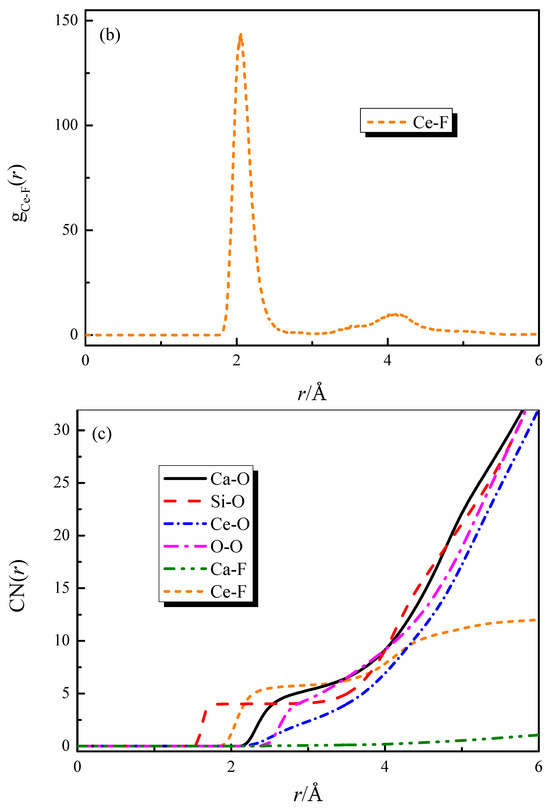

The radial distribution functions (RDFs) and coordination number (CN) curves for each particle pair in the CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 (slag #3) system are shown in Figure 1. From Figure 1a,b, it can be obtained that the bond lengths of Si-O, Ca-O, Ce-O, Ca-F, Ce-F, and O-O are 1.61, 2.31, 2.42, 2.35, 2.05, and 2.62 Å. The bond length values obtained from the simulation agree well with the experimental values [21,22,23,24,25], which verifies the accuracy of the simulation calculation. The coordination numbers of each particle pair can be obtained from Figure 1c, where some of the coordination structures are strongly influenced by the composition.

Figure 1.

RDFs and CNs of different particle pairs in slag #3: (a) RDFs curves of strongly characteristic particle pairs; (b) RDF curve of Ce-F; (c) CNs curves.

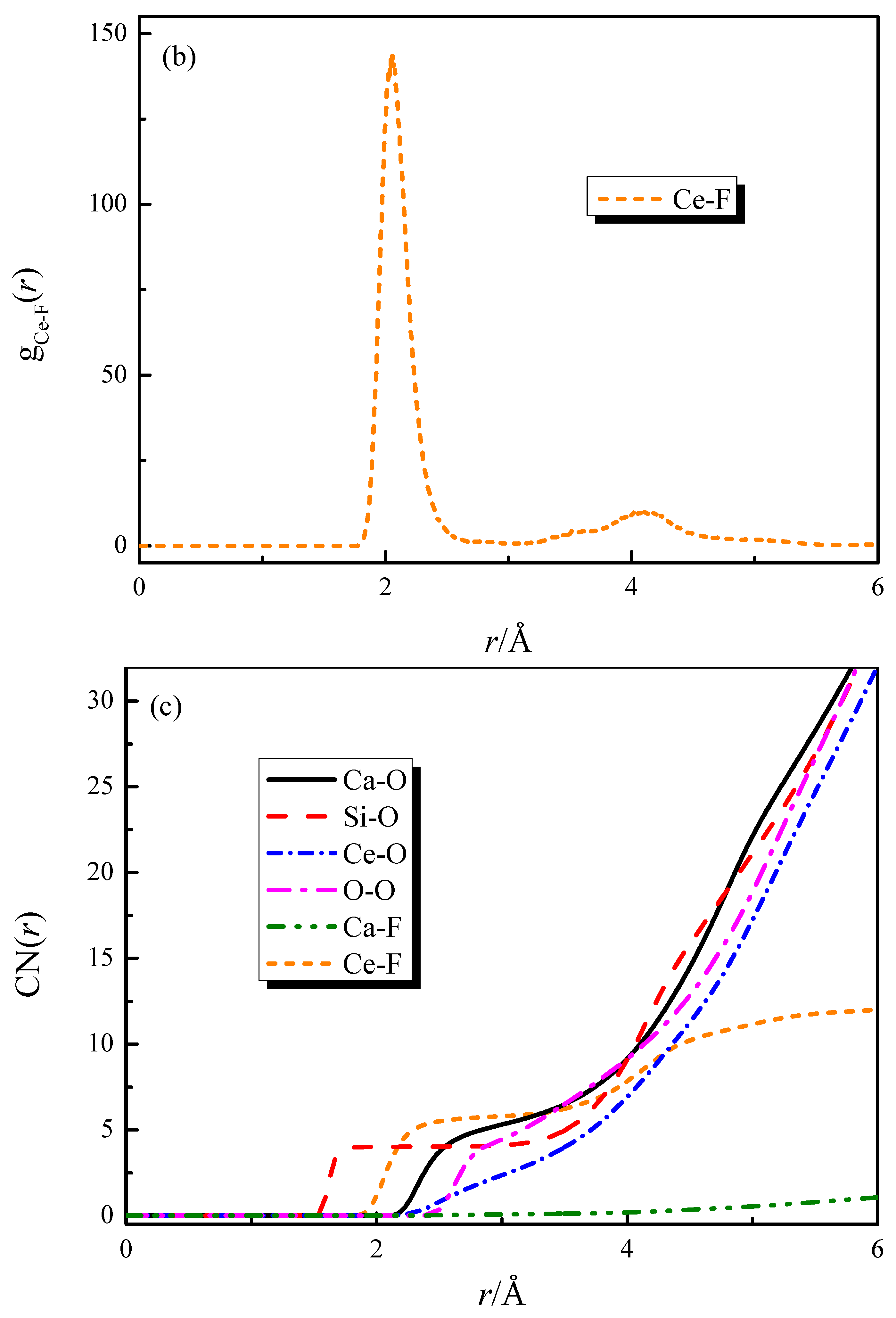

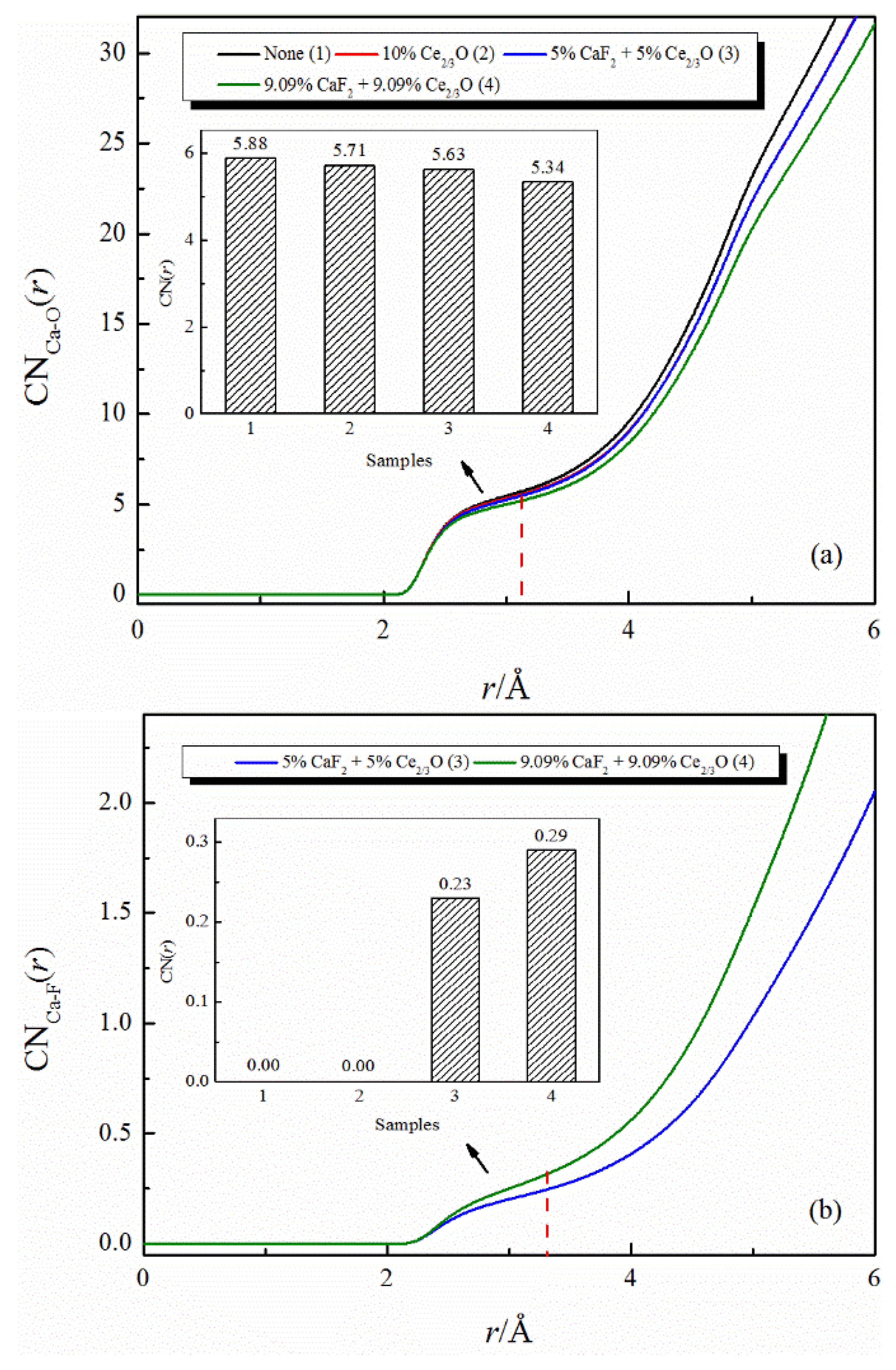

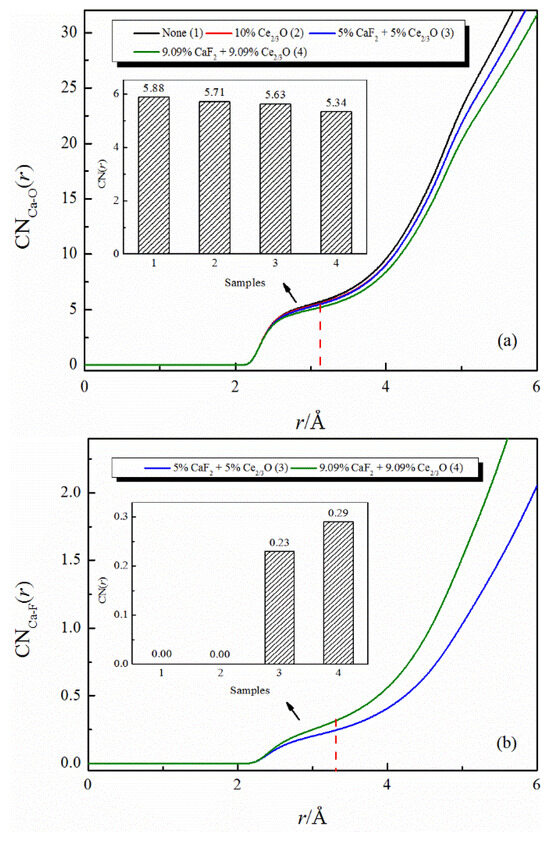

Figure 2 shows the effect of the addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 on the coordination numbers of Ca-O and Ca-F. The coordination number of Ca-O decreases with the addition of Ce2O3. When CaF2 and Ce2O3 are added jointly to the melt, the Ca-O coordination number decreases more significantly, and at the same time, the Ca-F structure appears in the melt. Our previous work [18,19] indicated that Ca-F binds more strongly than Ca-O in silicate melts, and the changes in this study are consistent with previous reports.

Figure 2.

The CNs curves of Ca-O and Ca-F in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 melts: (a) CNs curves of Ca-O; (b) CNs curves of Ca-F.

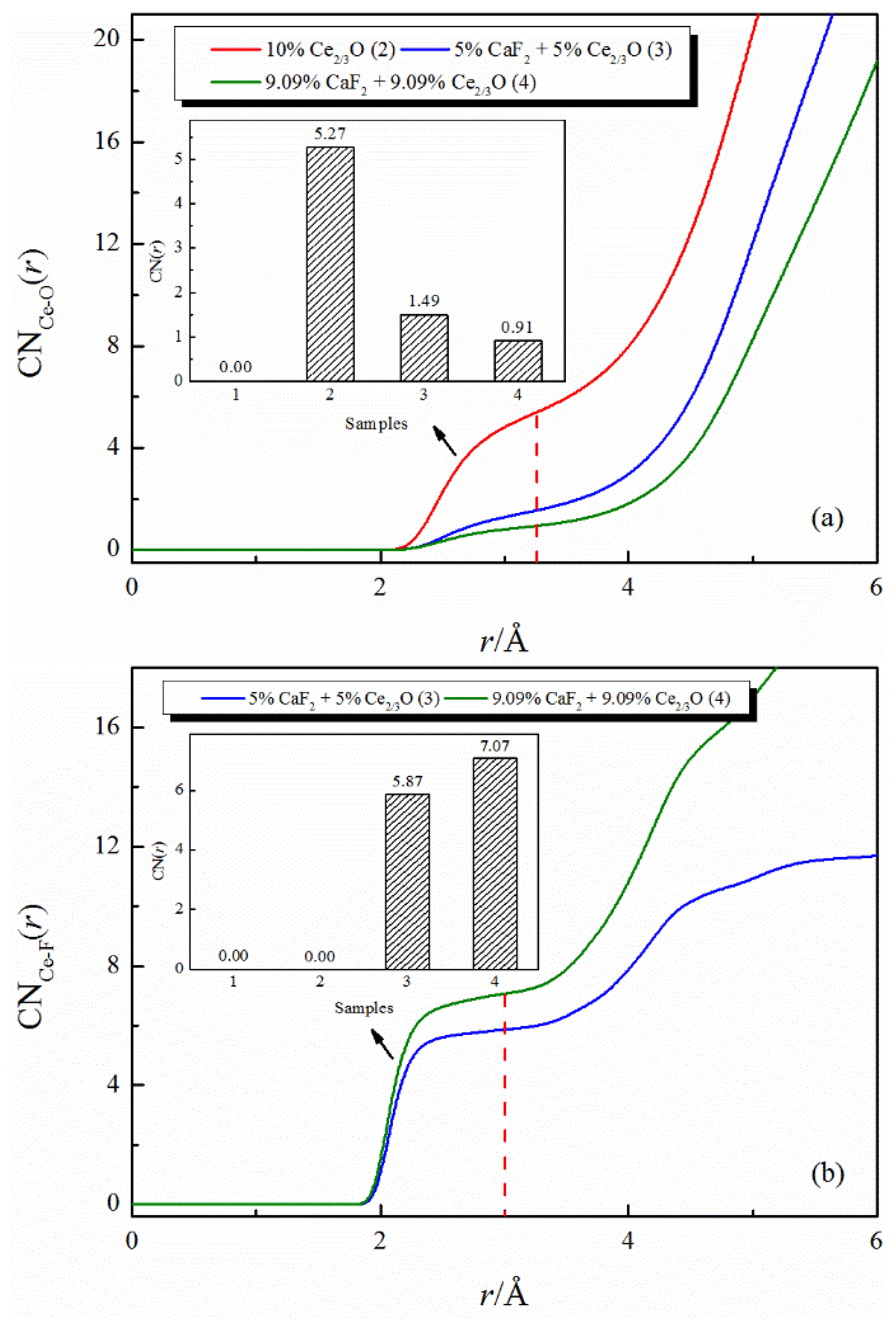

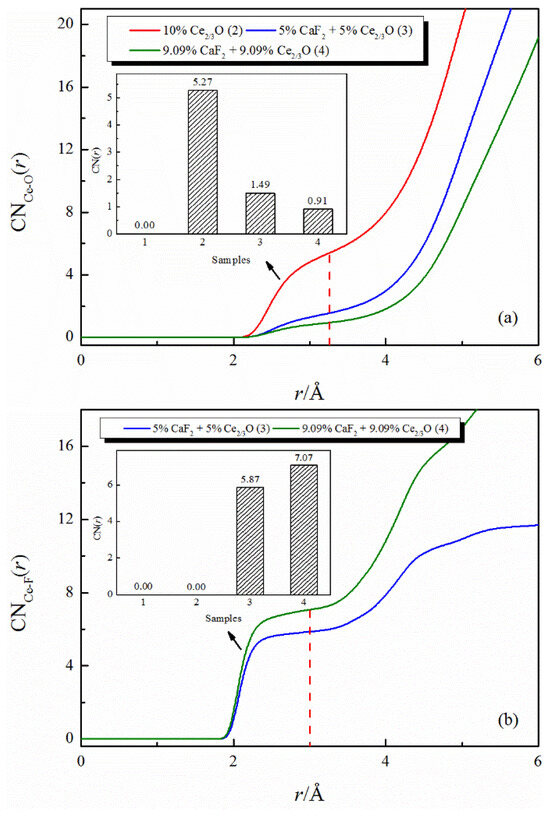

The effect of the addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 on the coordination numbers of Ce-O and Ce-F is shown in Figure 3. The total amount of additive remains unchanged, and as the additive changes from Ce2O3 to CaF2 and Ce2O3, jointly, the coordination number of Ce-O decreases significantly, and the Ce-F coordination structure appears in the melt. Increasing the additions of CaF2 and Ce2O3, the coordination number of Ce-O subsequently decreases, and the coordination number of Ce-F increases correspondingly. In addition, the plateau that appears in the curve of the coordination number of Ce-F is flatter than that of Ce-O. The above data indicate that the Ce-F coordination structure is more stable than the Ce-O coordination structure. Combining the changes in the coordination numbers of Ca-F and Ca-O, it is suggested that the fluoride coordination structures (Ca-F and Ce-F) are preferentially formed instead of oxide coordination structures (Ca-O and Ce-O), with the addition of Ce2O3 alone to the silicate melt transformed to a joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3. Lan [26] pointed out that the only rare earth-enriched phase precipitated in the CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 system during the temperature change was Ce9.33-xCax(SiO4)4O5-0.5xF2 (cerium fluorosilica phase), which provided an experimental data reference for the preferential binding of Ca2+ and Ce3+ to F−.

Figure 3.

The CNs curves of Ce-O and Ce-F in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 melts: (a) CNs curves of Ce-O; (b) CNs curves of Ce-F.

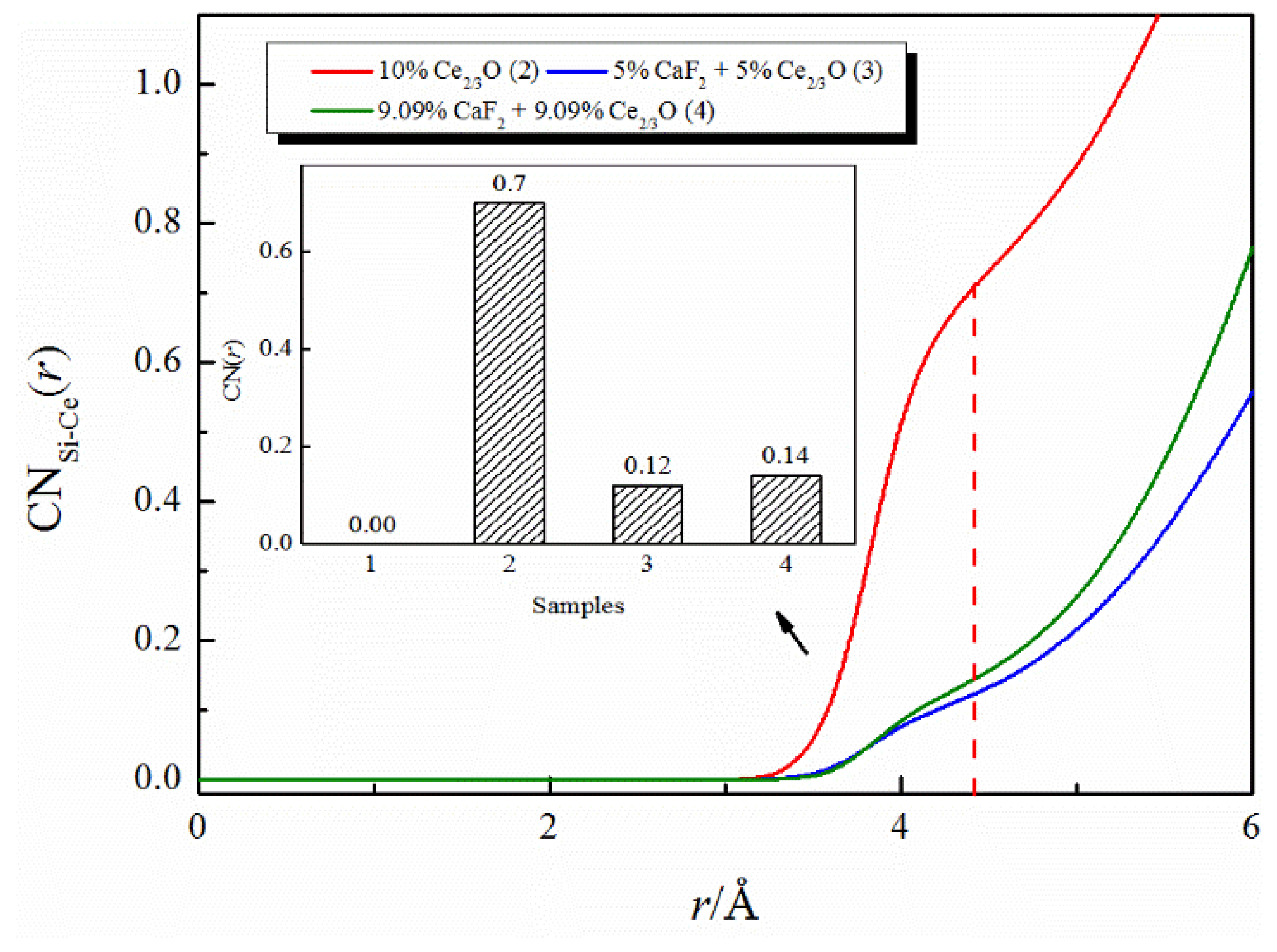

Figure 4 exhibits the effect of the addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 on the coordination numbers of Si-Ce. The coordination number of Si-Ce decreased from 0.7 to 0.12 when the total amount of the additive remained unchanged and the additive changed from the addition of Ce2O3 alone to the joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3. The coordination number of Si-Ce decreased from 0.7 to 0.14 when the same amount of CaF2 was added to the melt with 10% molar fraction of Ce2/3O. The above changes illustrate that the coordination number of Si-Ce is affected by both Ce2O3 and CaF2 content, as follows: the greater the addition of Ce2O3, the more Ce3+ replaces Ca2+ in [SiO4]4−-Ca2+ to form the [SiO4]4−-Ce3+ structure, and the coordination number of Si-Ce increases; and the more addition of CaF2, the more Ce3+ preferentially coordinates with F− to form the Ce-F structure, replacing the original [SiO4]4−-Ce3+ structure, and the coordination number of Si-Ce decreases.

Figure 4.

The CNs curves of Si-Ce in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 melts.

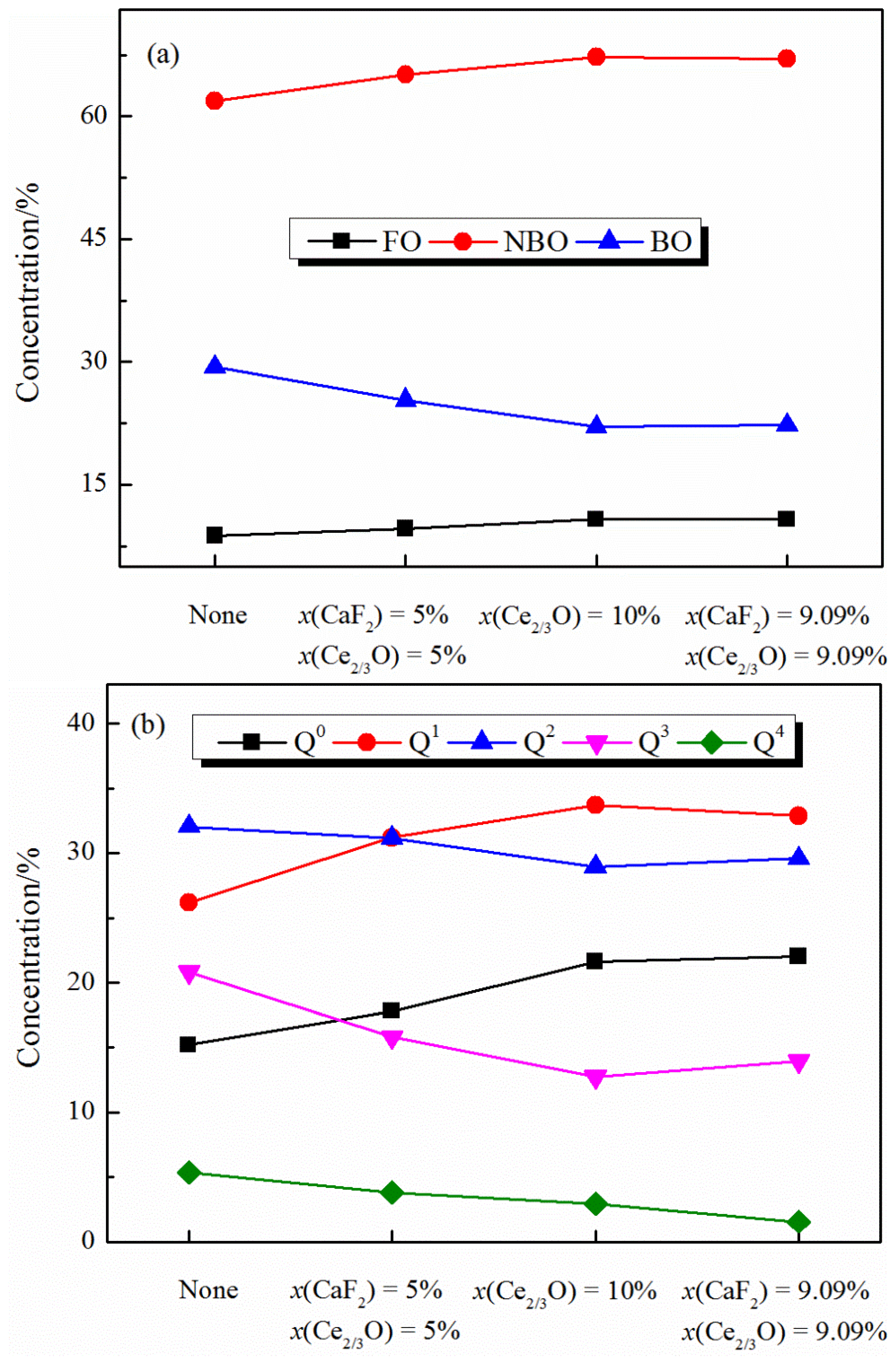

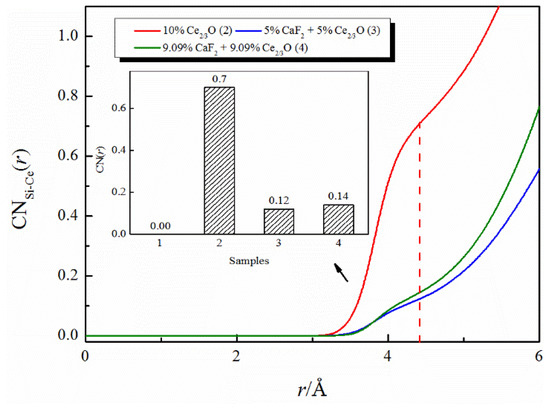

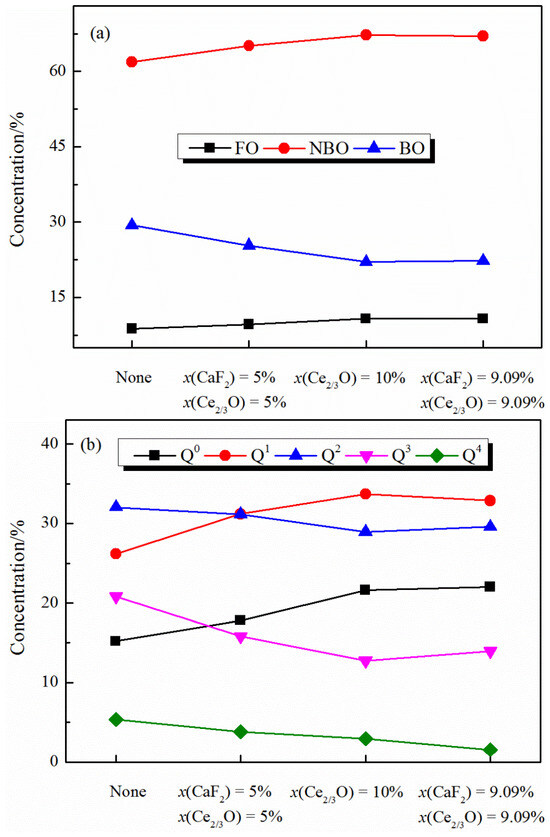

The variation in the medium-range melt structure with the addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen from Figure 5a that the distribution of oxygen types in the melt is mainly influenced by the Ce2O3 content. With the increase of Ce2O3 content, the percentage of free oxygen (FO) and non-bridge oxygen (NBO) in the melt increases, while the percentage of bridge oxygen (BO) decreases, and the polymerization degree of the melt decreases. It is worth noting that F− mainly forms a coordination structure with Ca2+ or Ce3+, and F− has one charge, so it cannot play a “bridging” role in the melt but can only form a structure similar to free oxygen (e.g., Ca-F). Therefore, considering the structure formed by different anions (F− and O2−), the addition of CaF2 has a more pronounced effect on the reduction in the polymerization of the melt structure.

Figure 5.

Distribution of medium-range structure in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 melts: (a) oxygen type and (b) Qn.

It is shown in Figure 5b that by fixing the content of Ce2O3 and adding CaF2 to the melt, the distribution of Qn (n indicates the number of bridging oxygen in the tetrahedral structural unit) changes less, indicating that the addition of CaF2 has less effect on the Qn distribution. With the increase in Ce2O3 content, the percentage of structural units Q0 and Q1 with a low degree of polymerization in the melt increased, and the percentage of structural units Q2, Q3, and Q4, with a high degree of polymerization, decreased, indicating that the degree of polymerization of the melt structure gradually decreased, and the degree of polymerization of the [SiO4]4− tetrahedral structure in the melt was mainly influenced by the Ce2O3 content.

3.2. Microscopic Insights into the Effect of Ce2O3 and CaF2 on Slag Viscosity

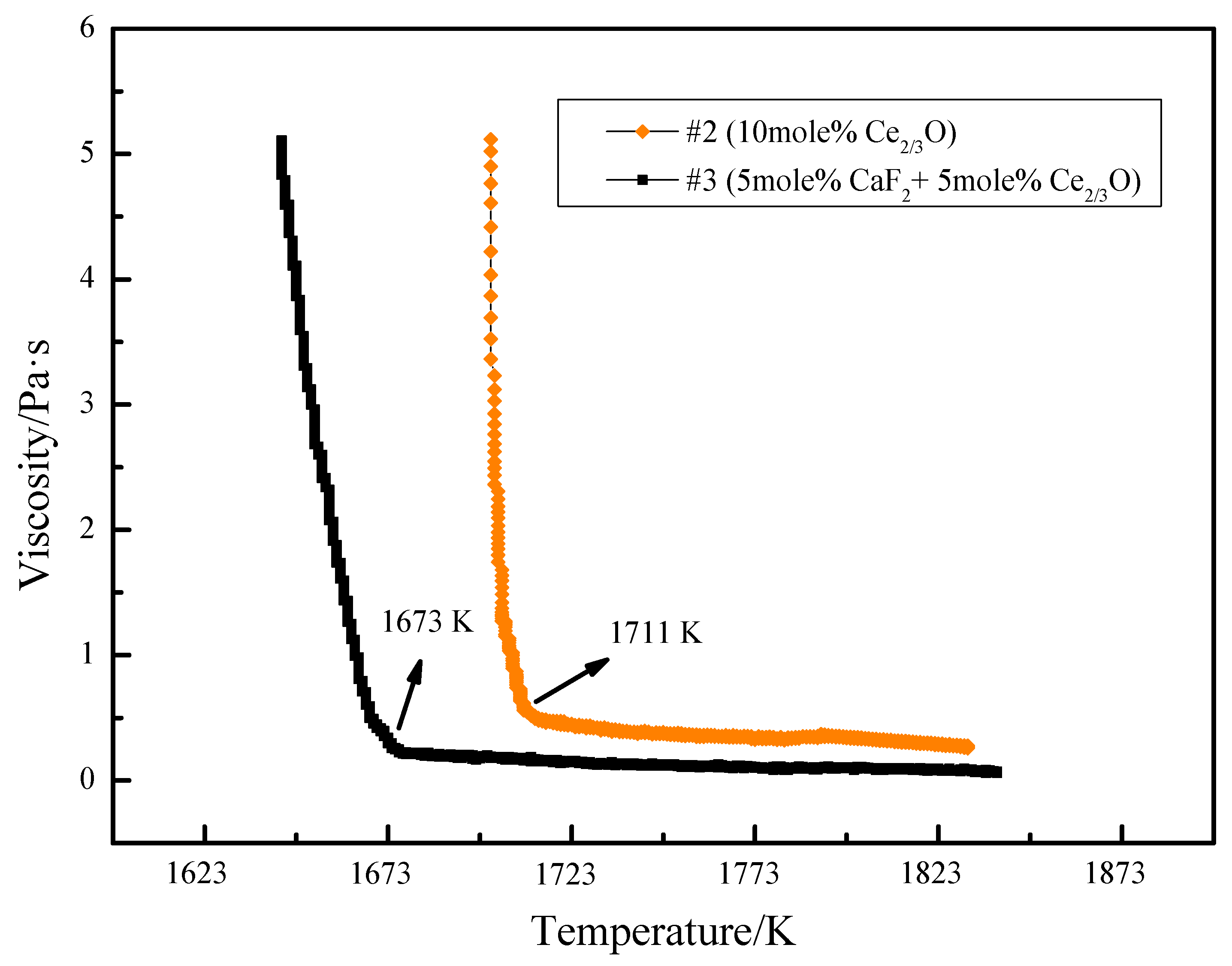

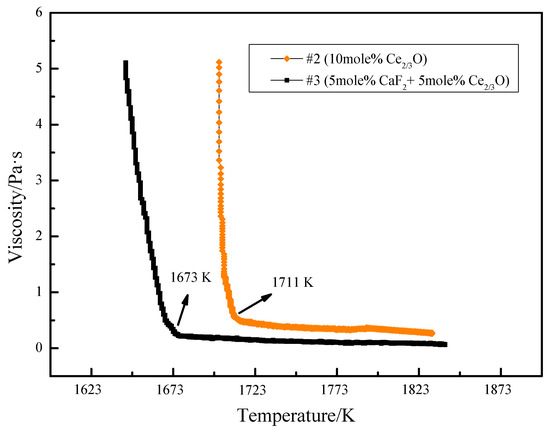

The viscosity–temperature variation curves of slag #2 and slag #3 were determined experimentally using the rotating column method. As can be seen from Figure 6, the high-temperature section viscosity value of slag #2 is 0.34 Pa·s and the turning point temperature is 1711 K. The high-temperature section viscosity value of slag #3 is 0.1 Pa·s and the turning point temperature is 1673 K. The change from the addition of Ce2O3 alone to the joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 resulted in a reduction of 0.24 Pa·s in the viscosity value of the slag in the liquid state (without crystal precipitation), and a reduction of 38 K in the turning point temperature, indicating that the joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 to the silicate melt can further improve the fluidity of the melt, while the stability of the viscous properties of the melt can be improved.

Figure 6.

Variation in slag viscosity–temperature curves with Ce2O3 and CaF2 content.

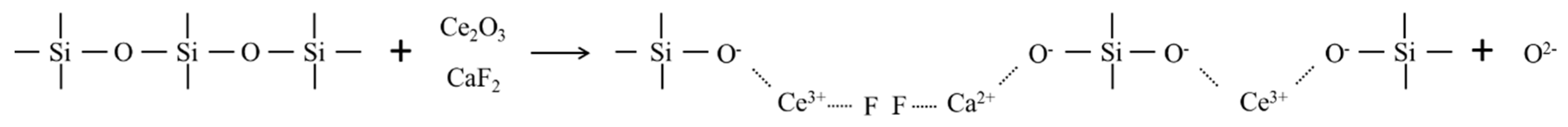

Our previous work [18] revealed the mechanism by which single substance additions affect slag viscosity changes: CaF2 improves slag fluidity by diluting the [SiO4]4− network structure, and Ce2O3 improves slag fluidity by depolymerizing the [SiO4]4− network structure. When CaF2 and Ce2O3 are jointly added to the CaO-SiO2 slag, the effect of CaF2 and Ce2O3 on the [SiO4]4− network structure is “superimposed”. The change in the melt structure is shown in Figure 7. With the addition of Ce2O3, the proportion of free oxygen and non-bridging oxygen in the melt increases, and the structural units with a high degree of polymerization (Q2, Q3, and Q4) shift to those with a low degree of polymerization (Q0 and Q1), and the complex [SiO4]4− network structure undergoes depolymerization, while with the addition of CaF2, more fluoride coordination structures (Ca-F and Ce-F) are formed in the melt, and since F− carries one charge, it can only form an isolated coordination structure. The M-F (M denotes cation) structure formed by F− replacing the O2− structure does not produce the electrostatic binding between adjacent [SiO4]4− structural units that occurs in the O-M-O structure, and the mobility of [SiO4]4− tetrahedra is enhanced and so too the mobility of the melt is further enhanced.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of the joint effect of CaF2 and Ce2O3 on silicate network structure.

3.3. Microscopic Insights into the Effect of Ce2O3 and CaF2 on Slag Crystallization Properties

The change in melt viscosity in the liquid state (without crystal precipitation) is mainly influenced by the degree of polymerization of the melt structure. In the process of a temperature change, if crystals are precipitated, the resistance of the crystals with a regular shape and stable structure to the “layer-to-layer slip” in the melt can be much greater than the network structure formed by the melt, and the melt viscosity appears to have a sharp increase. Therefore, the stability of the melt viscosity is closely related to the crystallization ability of the melt. The precipitation of crystals requires anion–cation interactions, and the only anion in the silicate melt is the [SiO4]4− anion group. Therefore, the more cations, of which species are around [SiO4]4−, the more favorable it is to form a certain type of silicate compound, and if this compound is a high-melting-point phase, then this phase can precipitate and the melt has a strong ability to precipitate crystals.

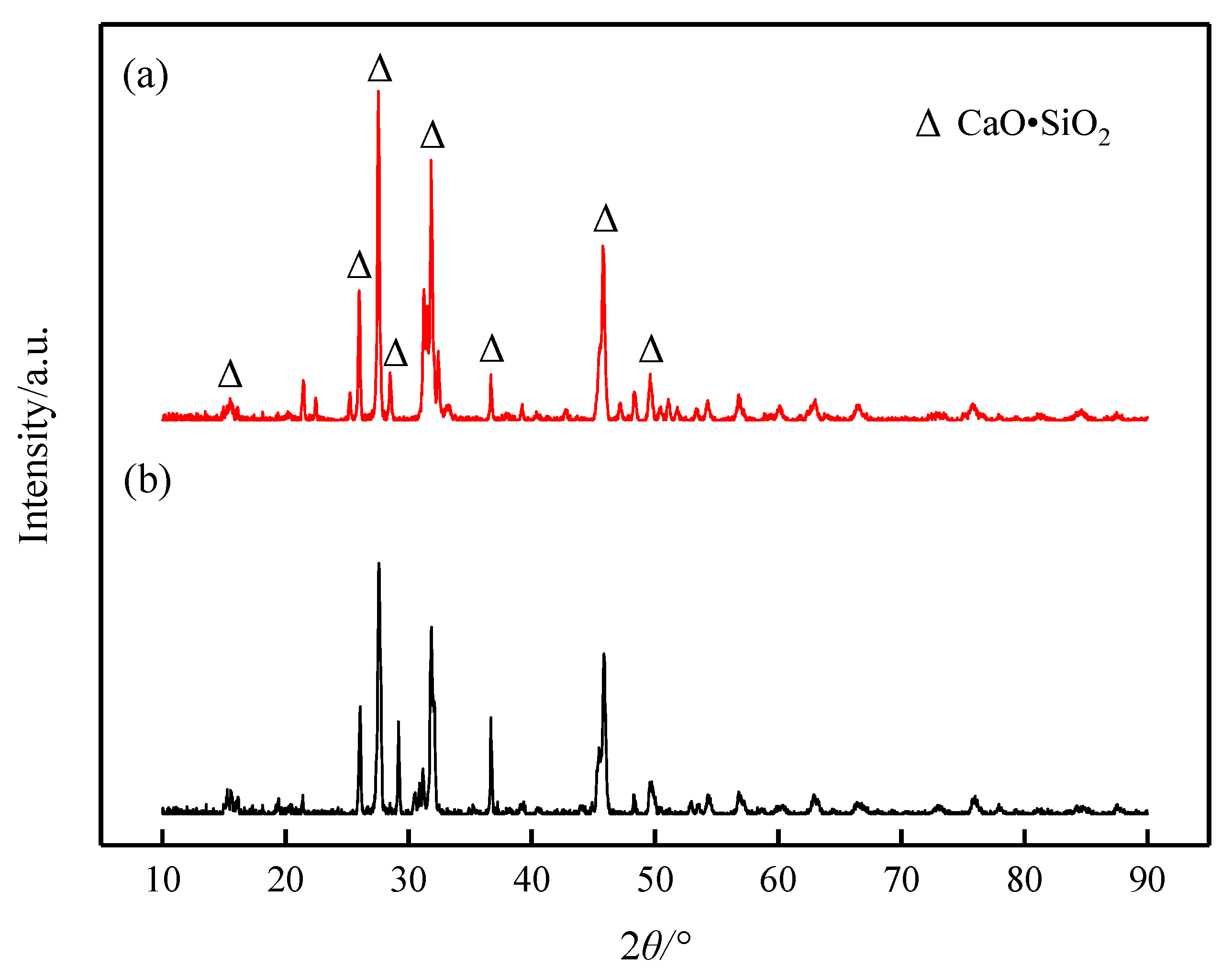

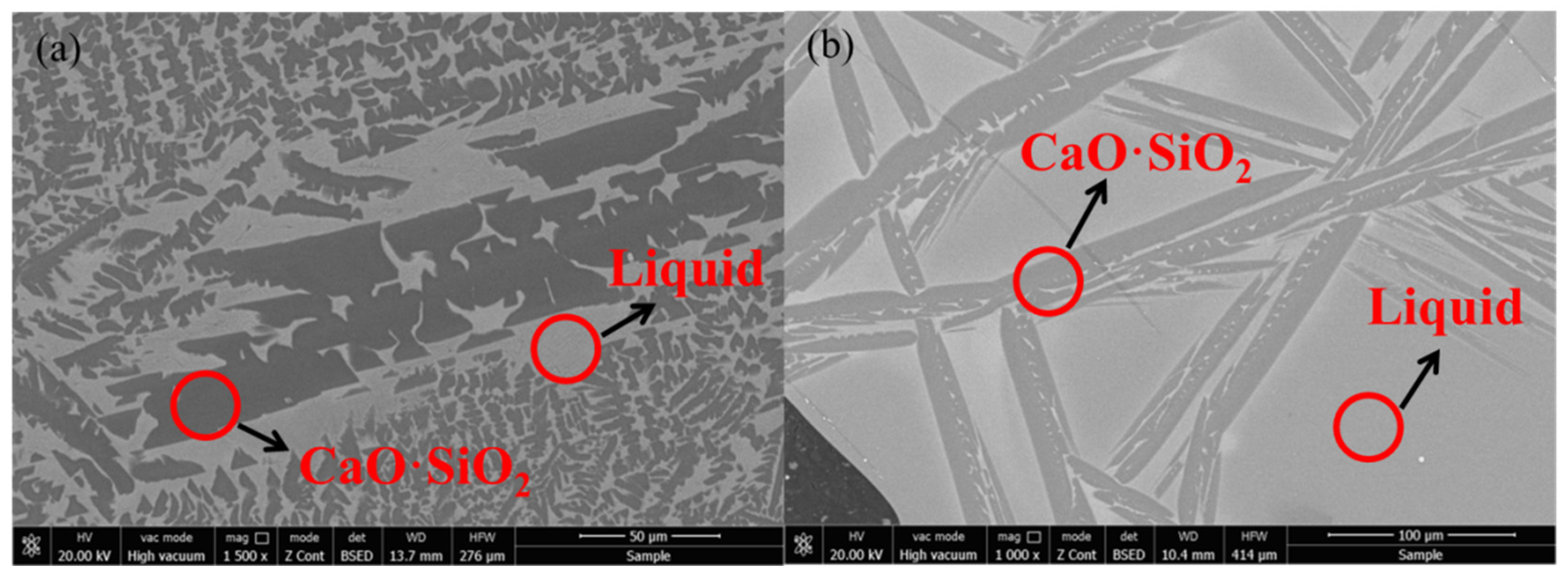

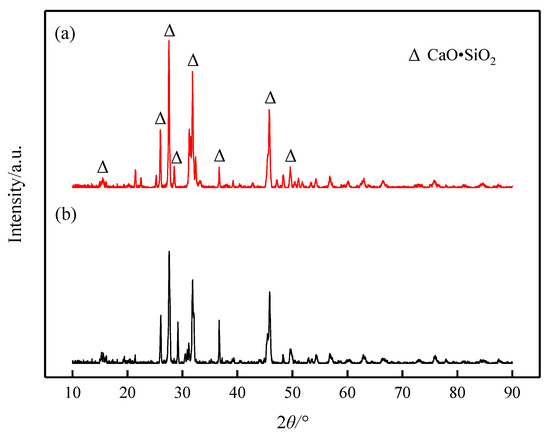

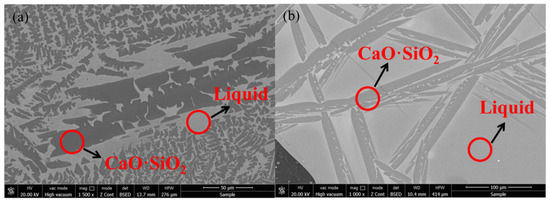

It can be seen from the results of XRD (Figure 8) and SEM-EDS (Figure 9) that the phase precipitated at the turning point of the viscosity–temperature curve of slag #2 is CaO-SiO2 (wollastonite), which appears denser in the SEM images, exhibiting aggregated hill-like morphologies. The phase precipitated at the turning point of the viscosity–temperature curve of slag #3 is also CaO-SiO2, and the morphology of this phase is mainly in the form of long dendrites, as observed in the SEM. From the analysis of the melt structure, it is clear that the coordination number of Si-Ce in the melt is low with the addition of small amount of Ce2O3, and Ca2+ is still dominant around the [SiO4]4− anion group. In this study, the molar ratio of CaO:SiO2 was 1:1, and [SiO4]4− joined with Ca2+ preferentially to form the wollastonite (CaO·SiO2) phase with a melting point of 1817 K [10], which precipitated during the cooling down process. With the joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 to the CaO-SiO2 slag, the preferential formation of fluoride (Ca-F and Ce-F) coordination structures in the melt facilitates the formation of cuspidine-type phases with a melting point of 1680 K [10], which is lower than that of wollastonite, and, therefore, the ability of the melt to precipitate crystals is reduced and the stability of the viscosity is improved.

Figure 8.

XRD patterns of slags at the turning point of viscosity–temperature curve: (a) slag #2 and (b) slag #3.

Figure 9.

Phase morphology of slags at the turning point of the viscosity–temperature curve: (a) slag #2 and (b) slag #3.

4. Conclusions

(1) In silicate melts, the addition of CaF2 enables F− to replace O2− and preferentially form fluoride coordination structures with cations (Ca2+ and Ce3+). Meanwhile, the introduction of Ce2O3 allows Ce3+ to displace Ca2+ in coordinating with [SiO4]4−, forming [SiO4]4−–Ce3+ complexes.

(2) The joint addition of CaF2 and Ce2O3 exerts a dual effect on the silicate melt structure; F− acts as a diluent for the silicate network, while the O2− provided by Ce2O3 promotes the depolymerization of the complex [SiO4]4− network. This leads to the transformation of highly polymerized structural units (Q2, Q3, Q4) into less polymerized ones (Q0, Q1), resulting in a decreased degree of polymerization and significantly improved slag fluidity.

(3) The preferential formation of [SiO4]4−–Ce3+–F− and [SiO4]4−–Ca2+–F− structures replaces the original [SiO4]4−–Ce3+ and [SiO4]4−–Ca2+ configurations. This structural evolution facilitates the formation of low-melting-point cuspidine-type phases during cooling, effectively suppressing the crystallization tendency of the slag and, thereby, enhancing the stability of its viscous properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.; Methodology, X.Z.; Formal analysis, X.Z. and Y.H.; Resources, X.Z. and Y.T.; Data curation, Y.H. and F.J.; Writing—review & editing, C.L.; Supervision, X.Z. and Y.T.; Project administration, X.Z. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan Joint Program, grant number 2023JH2/101800002, and The APC was funded by Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan Joint Program.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to deeply acknowledge the financial support of the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M730022), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1908224), and the Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan Joint Program (2023JH2/101800002).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xiaobo Zhang, Feng Jiang and Yan Huang were employed by the company Bayuquan Branch of Angang Steel Co., Ltd. Author Yong Tian was employed by the company Angang Steel Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Waudby, P.E. Rare earth additions to steel. Int. Met. Rev. 1978, 23, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.L.; Su, Y.H.; Kuo, C.L.; Su, Y.H.; Chen, S.H.; Lin, K.J.; Hsieh, P.H.; Hwang, W.S. Effects of rare earth metals on steel microstructures. Materials 2016, 9, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojola, N.; Ekerot, S.; Andersson, M.; Jonsson, P.G. Pilot plant study of nozzle clogging mechanisms during casting of REM treated stainless steels. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2011, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.; Karasev, A.; Jonsson, P.G. Effect of Si and Ce contents on the nozzle clogging in a REM alloyed stainless steel. Steel Res. Int. 2015, 86, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Li, C.L.; Wang, Y.S. Influence of rare earth on the mould flux properties. Chin. Rare Earths 2003, 24, 18–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.L.; Zhi, J.G.; Zhang, H.J.; Chen, J.X.; Zhang, X.F. Effects of earth oxides on physical and chemical properties of casting powder for continuous casting. Sci. Technol. Baotou Steel 2019, 45, 75–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.H.; Chen, T.M.; Zhao, Q.C.; Zhang, J.X.; Xiao, M.F. Development and application of mold powder to continuous casting of low alloy steel. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2000, 21, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.M. Development of mold powder for 09CuPRE series steel. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2004, 25, 35–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.K.; Ma, J. Development of mould fluxes for continuous casting rare earth steel. Jiangsu Metall. 2001, 29, 15–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verein Deutscher Eisenhüttenleute. Slag Atlas, 2nd ed.; Verlag Stahleisen GmbH: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1995; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, R.N.; Mountjoy, G. A molecular dynamics study of the atomic structure of (CaO)x(SiO2)1−x glasses. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 14273–14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumi, F.G.; Tosi, M.P. Ionic sizes and born repulsive parameters in the NaCl-type alkali halide—I: The Huggins-Mayer and Pauling forms. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1964, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; He, S.; Wu, T.; Wang, Q. Effect of fluorine on the structure of high Al2O3-bearing system by molecular dynamics simulation. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 46, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Q. Molecular dynamics and properties for the CaO-SiO2 and CaO-Al2O3 systems. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2015, 411, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayle, T.X.T.; Parker, S.C.; Catlow, C.R.A. The role of oxygen vacancies on ceria surfaces in the oxidation of carbon monoxide. Surf. Sci. 1994, 316, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlherr, A.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Moore, L.J.; Thomas, P.D. Molecular dynamics investigation of the structure and stability of zirconium-barium-rare earth fluoride glasses. Mater. Sci. Forum 1991, 67, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Liu, C.J.; Jiang, M.F. Effect of fluorine on melt structure for CaO-SiO2-CaF2 and CaO-Al2O3-CaF2 by molecular dynamics simulations. ISIJ Int. 2020, 60, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Liu, C.J.; Jiang, M.F.; Sun, J.L.; Zheng, X. The relationship between composition and structure: Influence of different methods of adding CaF2 on the melt structure of CaO-SiO2 slags. J. Sustain. Metall. 2022, 8, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Liu, C.J.; Jiang, M.F. Effect of Na irons on melt structure and viscosity of CaO-SiO2-Na2O by molecular dynamics simulations. ISIJ Int. 2021, 61, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Liu, C.J.; Jiang, M.F. Effect of B2O3 on the melt structure and viscosity of CaO-SiO2 system. Steel Res. Int. 2022, 93, 2100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, G.N.; Fontaine, A.; Lagarde, P.; Raoux, D.; Gurman, S.J. Local structure of silicate glasses. Nature 1981, 293, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakse, N.; Bouhadja, M.; Kozaily, J.; Drewitt, J.W.E.; Hennet, L.; Neuville, D.R.; Fischer, H.E.; Cristiglio, V.; Pasturel, A. Interplay between non-bridging oxygen, triclusters, and fivefold Al coordination in low silica content calcium aluminosilicate melts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 201903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Iguchi, M.; Hino, M. The role of Ca and Na ions in the effect of F ion on silicate polymerization in molten silicate system. ISIJ Int. 2007, 47, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygel, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Pantano, C.G.; Shibata, T.; Du, J.; Kokou, L.; Woodman, R.; Belcher, J. Local structure of cerium in aluminophosphate and silicophosphate glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 2442–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.S.; Tao, X.J.; Zhou, J.F.; Dang, H.X. Study of tribological behavior of CeF3 nanoparticles. Chin. Rare Earths 2001, 22, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Thermodynamics and kinetics of REEs in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-Ce2O3 system: A theoretical basis toward sustainable utilization of REEs in REE-bearing slag. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 6130–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).