Abstract

To reduce downtime of the Tunnel Boring Machine and improve construction efficiency of subway tunnels, the tunnel–station synchronous construction method was implemented in the Qingdao metro. In this method, the TBM advanced continuously through the station, while the upper station was excavated in stages using the primary support arch covering technique. Focusing on a construction scheme with low-grade temporary segments, this study develops a three-dimensional numerical model to investigate the mechanical response of shield lining during the simultaneous construction of a subway station and tunnel. The Mohr–Coulomb model and the Elastic model were employed to represent the mechanical behavior of the surrounding rock and support structure, respectively. The deformation, bending moment, axial force, and residual bearing capacity coefficients of the shield lining were systematically examined across six distinct construction stages. The results showed that asymmetric gradual unloading of the surrounding rock at the arch part caused the vertical displacement of the shield lining to be predominantly upward, with a maximum heave of 1.51 mm. Horizontal displacement exhibited significant asymmetry. During station arch excavation, asymmetric unloading led to an increase and clockwise shift in the bending moments of the shield lining. The axial forces transitioned from compression to tension at specific locations (40° and 240°), whereas the removal of temporary supports had only a minor influence. The maximum tensile stress of the shield lining increased by 3.35 times in Stage III and reached 0.69 MPa in Stage V, representing a 1.65-fold increase compared to the previous stage. Although the residual bearing capacity coefficient generally satisfied safety requirements throughout the construction process, it decreased to a minimum of 0.88 in Stage V, a 7% reduction relative to Stage IV, necessitating close monitoring. This study not only confirmed the safety of using temporary segments made of lower-grade concrete (C30) in tunnel–station synchronous construction but also provided valuable insights for optimizing construction schemes and controlling key risks, such as structural deformation, in similarly complex urban environments.

1. Summary

In recent years, the rapid expansion of urban rail transit networks has driven the growing adoption of integrated construction techniques for metro stations and adjacent tunnel sections [1,2]. In densely populated urban cores with heavy traffic and complex geological conditions, critical challenges include ensuring construction safety, reducing project duration, and minimizing environmental disturbance. Under conventional practice, the tunnel boring machine (TBM) must be halted, disassembled outside the station, and reassembled within it—interrupting excavation continuity, elevating safety risks, and increasing the likelihood of delays. To overcome these constraints, the tunnel–station synchronous construction method has been developed. This approach enables the TBM to advance continuously through the station area while the station’s main structure is excavated sequentially using the primary support arch cover method, allowing for coordinated tunnel and station construction. Although this technique clearly offers schedule and cost advantages, the mechanical implications for unloading the arch rock mass and the structural safety of temporary segments remain insufficiently understood.

As the scale and complexity of metro station projects continue to increase, TBM-based station construction methods are gaining prominence owing to their superior spatial efficiency and shortened timelines compared with alternative techniques. For example, the Mansour Station on Tabriz Metro Line 1 in Iran [3] employed a “concrete arch pre-support system” to enlarge a shallow-buried TBM tunnel into a large-span station. Liu et al. [4] introduced the pile–beam–arch (PBA) method for enlarging large-diameter TBM tunnels and validated its structural safety via FLAC3D simulations. Dobashi et al. [5] developed an innovative technique combining open-cut shafts with semi-rectangular jacked boxes (SCJB). Additional studies [6] have investigated PBA support mechanisms, settlement evolution during excavation, and tunnel enlargement-based station construction strategies [7]. In complex urban settings, hybrid approaches that integrate TBM and conventional mining methods have matured over years of application, yielding a variety of innovative solutions. For instance, Wang et al. [8] proposed a novel pipe-jacking–mining hybrid design for Shasan Station on Shenzhen Metro Line 12; Cao et al. [9] developed an enlargement method for Beijing Metro Line 14 stations using large-diameter TBM tunnels as access and working platforms; and Wang et al. [10] reported on the design and construction of super-large rectangular pipe-jacking machines for station construction. Furthermore, Lei et al. [11] cautioned against the arch cover method in Class V or poorer rock masses and in Class IV “soft-over-hard” strata without pre-reinforcement. Song et al. [12] analyzed stress and deformation in shallow-buried single-arch construction based on the Xinggong Street Station project in Dalian, refining the design methodology for large-span single-arch stations. Guo et al. [13] addressed TBM reception in constrained sites using a combined shaft–arch cover method. Research on structure–ground interaction has also been significant. Ng et al. [14] employed three-dimensional numerical analysis to evaluate the impact of the width–diameter ratio (B/D) between existing horseshoe-shaped tunnels and new circular tunnels on stress distribution. Zhang et al. [15] applied compensation grouting to reinforce the rock mass between new and existing tunnels in Beijing Metro Line 5, mitigating the effects on Line 2. Liu et al. [16] proposed a lateral elastic resistance method for non-circular closed-loop structures to analyze bending moment development during Beijing Metro Line 12 construction beneath Line 5. Ye et al. [17] developed a LightGBM-based model to predict deformation and additional stresses in existing tunnels, identifying tunnel relative position and mean earth pressure as dominant factors.

Overall, the combined TBM mining approach for underground station construction has been implemented for decades, with most studies concentrating on process enhancement and TBM-driven tunnel enlargement. The synchronous tunnel–station construction method offers significant advantages in improving the efficiency of metro engineering. However, existing research has primarily focused on sequential excavation—where the station is excavated first, followed by the tunnel—while studies on the simultaneous construction of stations and tunnels remain insufficient. This gap has led to a lack of understanding regarding structural safety under such construction conditions. To address this issue, this study employs numerical simulation to systematically investigate the mechanical response mechanism of segment structures under synchronous tunnel–station construction, thereby ensuring safety in practical engineering applications.

This paper examined an under-construction metro station in Qingdao, located in the Shinan District—an urban environment characterized by high residential density and heavy traffic. In the station section, low-grade temporary segments were installed to reduce cost and facilitate subsequent removal. To investigate the deformation and load-bearing behavior of temporary segments during staged arch excavation, a three-dimensional FLAC3D numerical model was developed. The study systematically evaluated displacement fields, internal force redistribution, and residual bearing capacity coefficients across different construction stages, aiming to provide theoretical guidance and engineering reference for safe implementation of synchronous tunnel–station construction in complex urban zones.

2. Project Description

The under-construction metro station in Qingdao was in the southwest quadrant of the intersection of two major urban thoroughfares in the Shinan District of Qingdao City. The area experienced high vehicular traffic and was surrounded by extensive residential development, which significantly complicated the construction process. While ensuring construction safety, reducing the construction duration to minimize the impact on residents was another major challenge for this project.

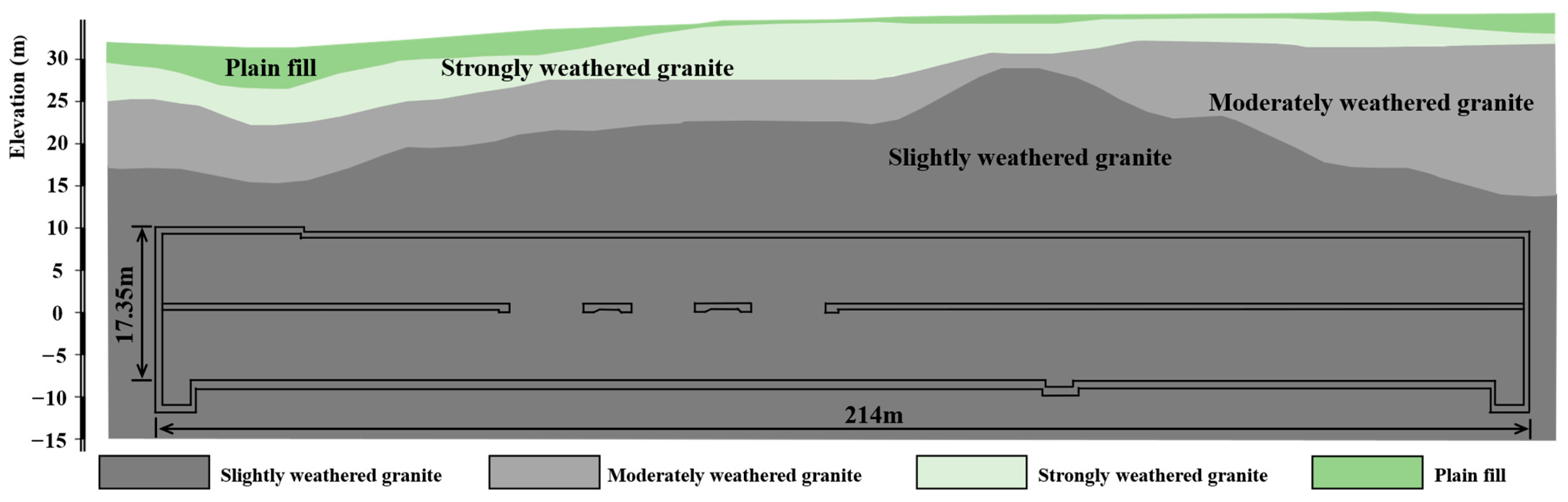

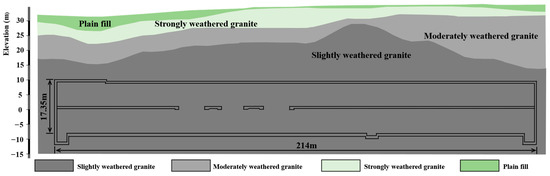

The station was an underground, two-level platform station with 11 m wide platforms, constructed using the cut-and-cover method. The structure consisted of a single-tube extra-large-span arch tunnel, using the mining method (primary support arch cover method), with a fully enclosed waterproof structure. The primary composition of the main tunnel excavation was granite, which had undergone negligible weathering, including in its joint-developed zones. Localized intrusions of vein-like diorite and granodiorite were also present. The presence of sandy-like fractured rock and blocky fractured rock in localized areas was indicative of tectonic influences. The stability of the surrounding rock was generally good to very good, with some areas exhibiting poorer stability. The groundwater was predominantly characterized by a low water content, with a substantial proportion of 92.4% comprising Rank III and above surrounding rock. The stratigraphy of the station’s main structure in the study section is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stratigraphy of the station’s main structure in the study section.

The black lines in Figure 1 denote the outline of the station structure. The station spanned from YDK3 + 152.600 to YDK3 + 366.600, with a total length of 214 m. The standard segment of the main structure had a width of 21.1 m and a height of 17.35 m, progressing from the small mileage to the large mileage direction. Two TBMs were launched from the MaiBei section, employing a “tunnel–station synchronized” excavation method to advance through the station. After the TBMs were hoisted out at the terminal station, the temporary segments within the station area were demolished to complete the lower bench excavation of the station. The outer diameter of the temporary lining segments for both left and right lines in the station section was 6 m, the inner diameter was 5.4 m, the segment thickness was 0.03 m, the segment width was 1.5 m, the concrete grade was C30, the compressive strength was 30 MPa, and the tensile strength was 1.78 MPa. Compared to the standard segment scheme, the low-specification segments saved approximately 8836.16 RMB per segment, effectively reducing project costs and resource wastage.

To prevent the TBM from stopping outside the station and ensure the continuity of the project and construction efficiency, this project employed the tunnel–station synchronous construction method. Under this method, the TBM continued to excavate continuously when it reached the station area, while the station arch was constructed using the primary support arch cover method and was divided into four pilot tunnels that were implemented sequentially. The project’s significance lay in its unique integration of TBM tunnels and subway stations within a complex urban site, making it a noteworthy case study for assessing the safety of temporary segments using this method. This project made two significant contributions. First, it helped to develop an important transportation hub. Second, it provided valuable reference for future engineering practices in similarly constrained urban environments.

3. Numerical Modeling

3.1. Establishment of the Numerical Model

FLAC (Fast Lagrangian Analysis of Continua) 3D 7.0 is based on a hybrid discretization method and explicit finite difference method. The software’s ability to simulate a multitude of elements with minimal memory requirements makes it a valuable tool in various fields, including underground cavern engineering, tunnel engineering, and mining engineering [18,19,20]. In this research, we employed the full suite of software functionalities to assess the safety performance of temporary segments under the concurrent construction of tunnel stations.

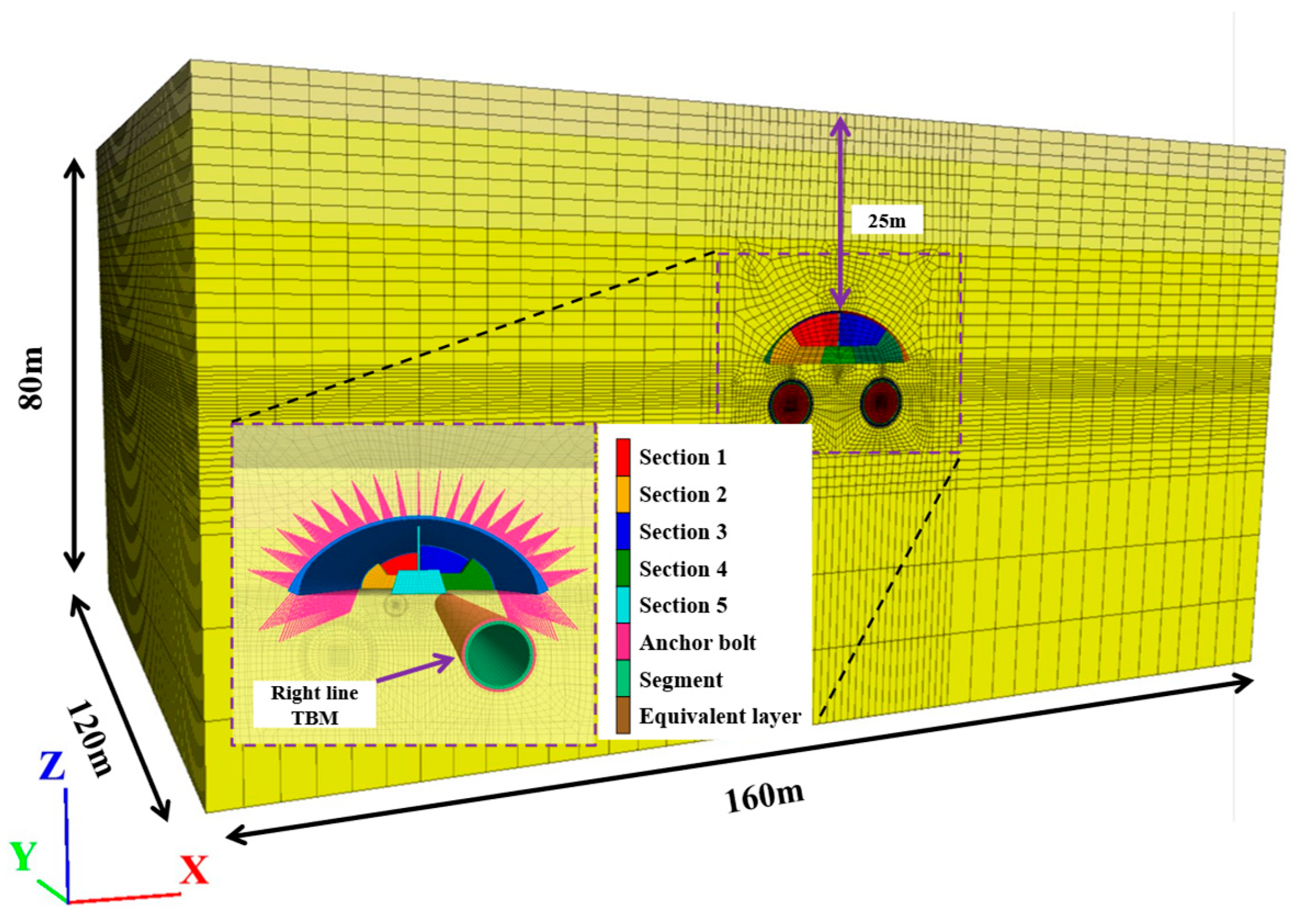

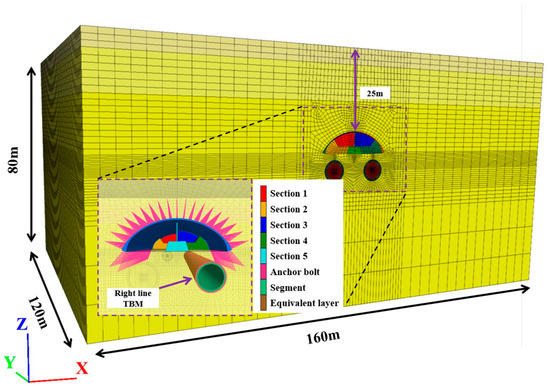

This paper took an under-construction station on Qingdao Metro Line 5 as the engineering background and established a three-dimensional numerical simulation model using FLAC3D finite difference software to study the entire process of tunnel–station synchronous construction. The established numerical model is shown in Figure 2. In view of the spatio-temporal relative position relationship between TBM mechanical excavation and the primary support arch cover method, as well as to minimize the influence of tunnel excavation boundary effects [21,22], the established three-dimensional numerical model had dimensions of 160 m in length, 120 m in width, and 80 m in height. The Rhino and the Griddle plugin were adopted for mesh generation. The surrounding rock, primary support, and temporary lining segments were all modeled using three-dimensional solid elements. The bottom of the model was set with complete normal constraints, the four sides were set with normal constraints, and the top was a free surface.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional numerical model of synchronized construction of the tunnel and station.

To accelerate calculation without affecting the accuracy of analysis results, it was necessary to simplify the numerical model. The following assumptions were made for this modeling: (1) It was assumed that the strata were uniform and clearly defined, with similar strata merged and simplified. Each stratum was considered an isotropic and continuous elasto-plastic body. (2) The surrounding rock was modeled using the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive law, accounting for the contact and deformation compatibility between the surrounding rock and the support structures. Considering that dewatering operations were conducted before station construction, the construction was under water-free conditions, so the influence of groundwater was not considered. (3) Only the influence of self-weight stress was considered in the calculation process, while the influence of surrounding buildings was ignored. (4) The primary support grid steel frame and concrete were equivalent to reinforced concrete, with the equivalent elastic modulus calculated by Equation (1):

where

E = Equivalent elastic modulus of the primary support structure (GPa).

Ec = Elastic modulus of primary support concrete (GPa).

Eg = Elastic modulus of grid steel arch (GPa).

Sc = Cross-sectional area of concrete (m2).

Sg = Cross-sectional area of grid steel arch (m2).

(5) Temporary lining segments were treated as a continuous structure with certain stiffness. Considering that joints and bolts reduced the overall stiffness of the segments, a stiffness reduction factor of 0.85 was applied. (6) All materials were assumed to be isotropic and homogeneous.

Based on Code for Design of Metro (GB50157-2013) [23], Code for Design of Railway Tunnel (TB10003-2016) [24], Geotechnical Investigation Report for Qingdao Metro Line 5 Project (Bid Section 1), and corresponding design data, the parameters of the surrounding rock and support structures were determined. The primary support for the station’s arch section utilized the “anchor-net-grid arch-sprayed concrete” system, comprising C25 early-strength shotcrete + φ25 grouted hollow anchor bolts + grid steel arch. Anchor bolts are arranged at a longitudinal spacing of 0.75 m, a circumferential spacing of 1.5 m, an elastic modulus of 210 GPA, and an ultimate tensile strength of 160 kN. The cable elements in FLAC3D were adopted to model the bolts, with interface elements explicitly simulating the contact behavior between the bolts and the surrounding rock. The primary support employed I-25 steel sections, and the temporary segments used C30 concrete with a thickness of 30 mm. The physical and mechanical parameters of strata in the numerical model were selected from the Geotechnical Investigation Report, as detailed in Table 1. The calculation parameters for the station’s support structures are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Main physical and mechanical parameters of strata.

Table 2.

Calculation parameters of the support structure.

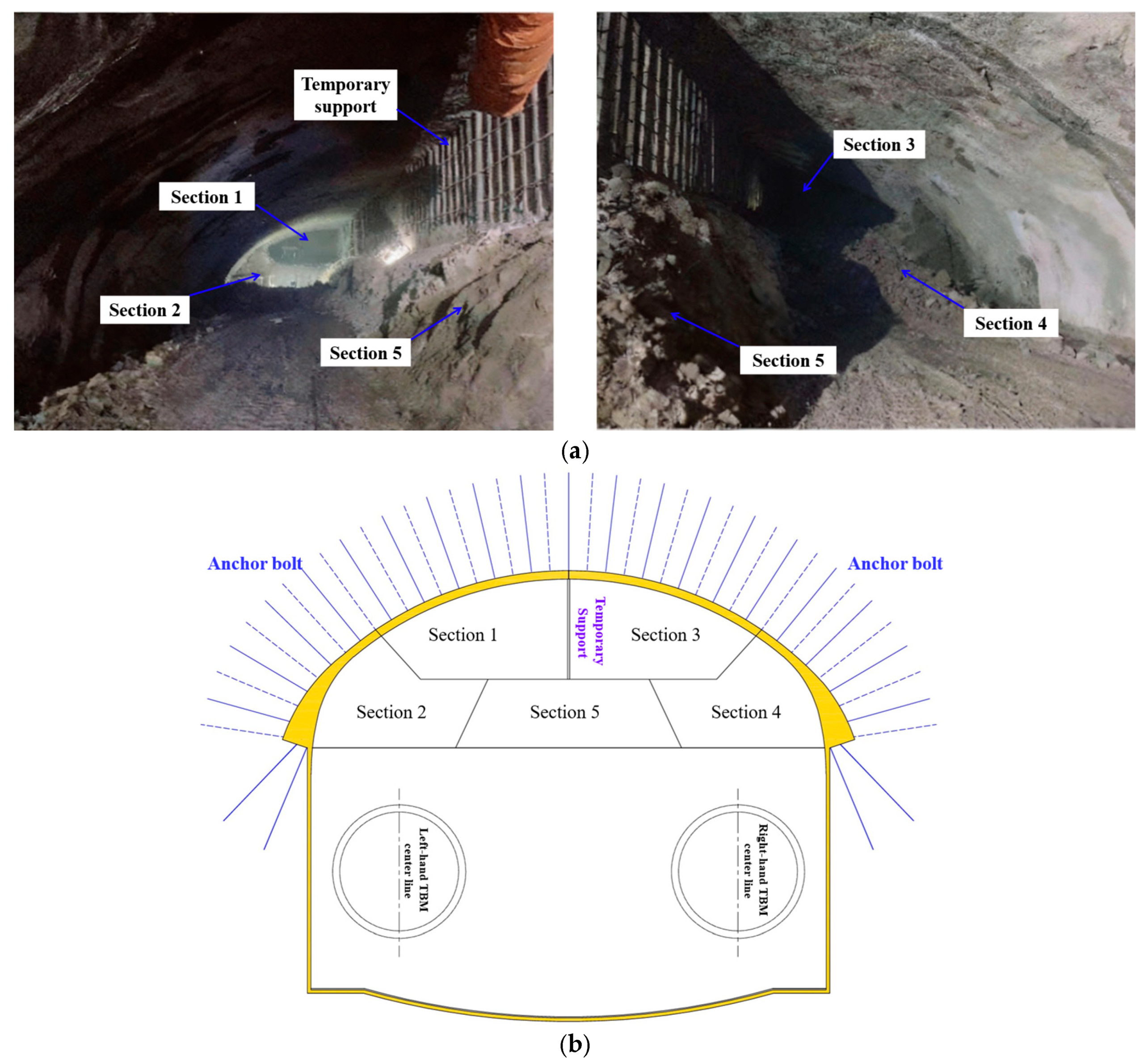

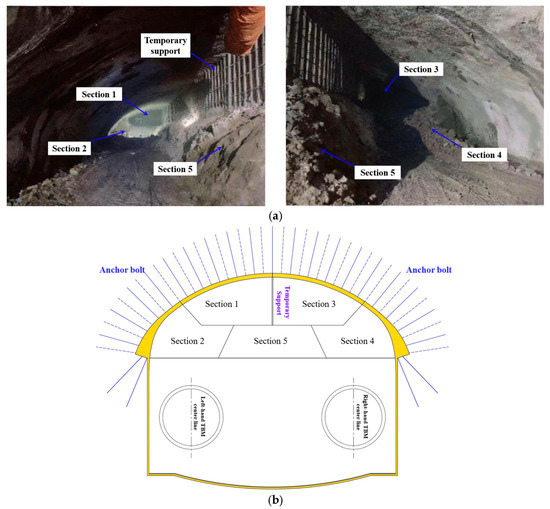

3.2. Construction Procedure

To prevent TBM shutdown outside the station and ensure the continuity and efficiency of the project, the “tunnel–station synchronous construction method” was adopted in this engineering project. Under this method, while the TBM continued its excavation through the station zone, the arch section of the station was constructed using the primary support arch cover technique. The division of the surrounding rock areas in the arch is shown in Figure 3. The specific construction sequence was as follows: First, rock mass (Section 1) excavation was conducted, followed by rock mass (Section 2) excavation with a step length controlled within the range of 6–8 m. Subsequently, rock mass (Section 3) excavation was carried out, maintaining a safety distance of at least 15 m from the rock mass (Section 2). Thereafter, rock mass (Section 4) excavation was performed, also with a step length controlled within the range of 6–8 m. After the primary support structure had stabilized, the steel supports were progressively removed, followed by the excavation of the rock mass (Section 5). When the right-line TBM passed through the station area, rock mass (Section 1) was excavated from the 48 m mark to the 64.5 m mark. All rock mass sections were excavated synchronously, and immediate implementation of primary support measures was carried out upon completion of excavation to ensure construction safety and engineering quality.

Figure 3.

Spatial relationship between the surrounding rock and shield tunnel. (a) On-site photos of the surrounding rock in the arch section. (b) The spatial relationship between the surrounding rock and the shield tunnel.

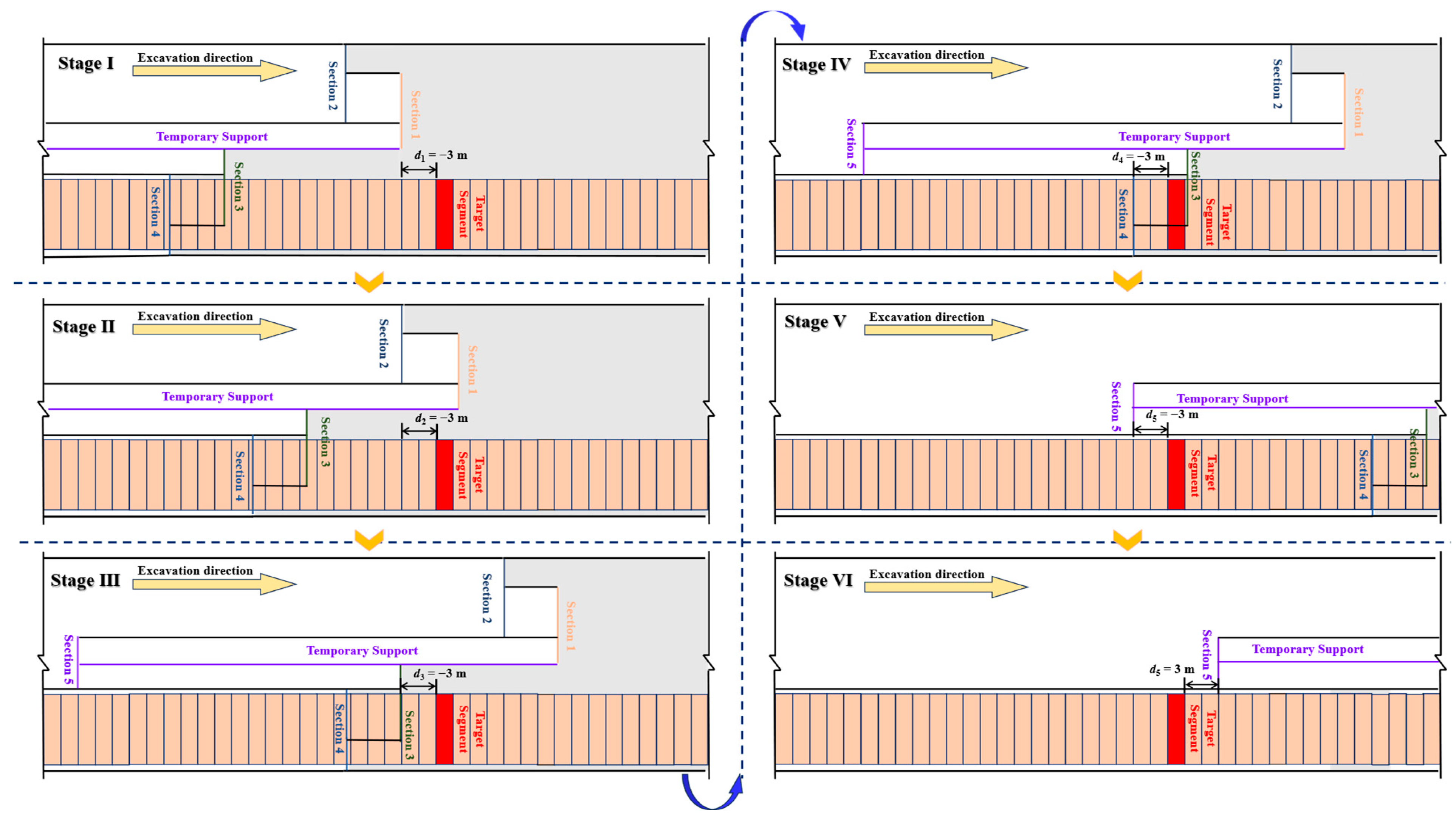

3.3. Division of Construction Stages

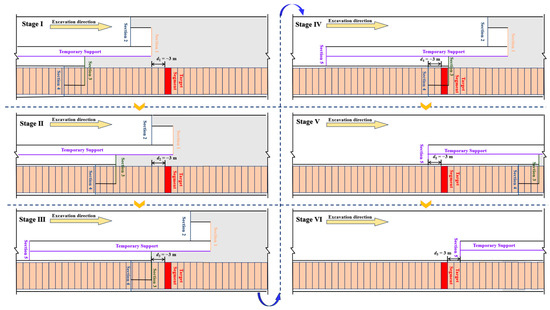

To systematically analyze the mechanical response of the right-line target segment during the arch excavation process, this study divided the construction process into six stages (Stage I to Stage VI). It conducted a detailed analysis of the effects of different excavation faces on the target segment. Specifically, Stage I was defined as the state where the excavation face of Section 1 was 3 m away from the target segment (d1 = −3 m). Similarly, Stage II, Stage III, and Stage IV corresponded to the states where the excavation faces of Sections 2, 3, and 4 were 3 m away from the target segment, respectively. Stage V and Stage VI represented the states where the surrounding rock and temporary supports of Section 5 were 3 m away from the target segment on both sides (d5 = −3 m and d5 = 3 m). The flowchart illustrating the synchronous construction process analysis is presented in Figure 4. By systematically analyzing the displacement, bending moment, axial force, and residual bearing capacity coefficient of the right-line target segment across these six stages, the mechanical response patterns of the target segment during arch excavation could be clearly revealed. This research methodology not only enhanced the understanding of the influence of different construction stages on the mechanical state of the target segment but also provided important theoretical basis and practical references for optimizing construction processes and improving the safety and stability of tunnel structures.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing the spatial positions of the arch sections’ surrounding rock and the target segment during different construction stages.

4. Result

4.1. Displacement Distribution and Trend

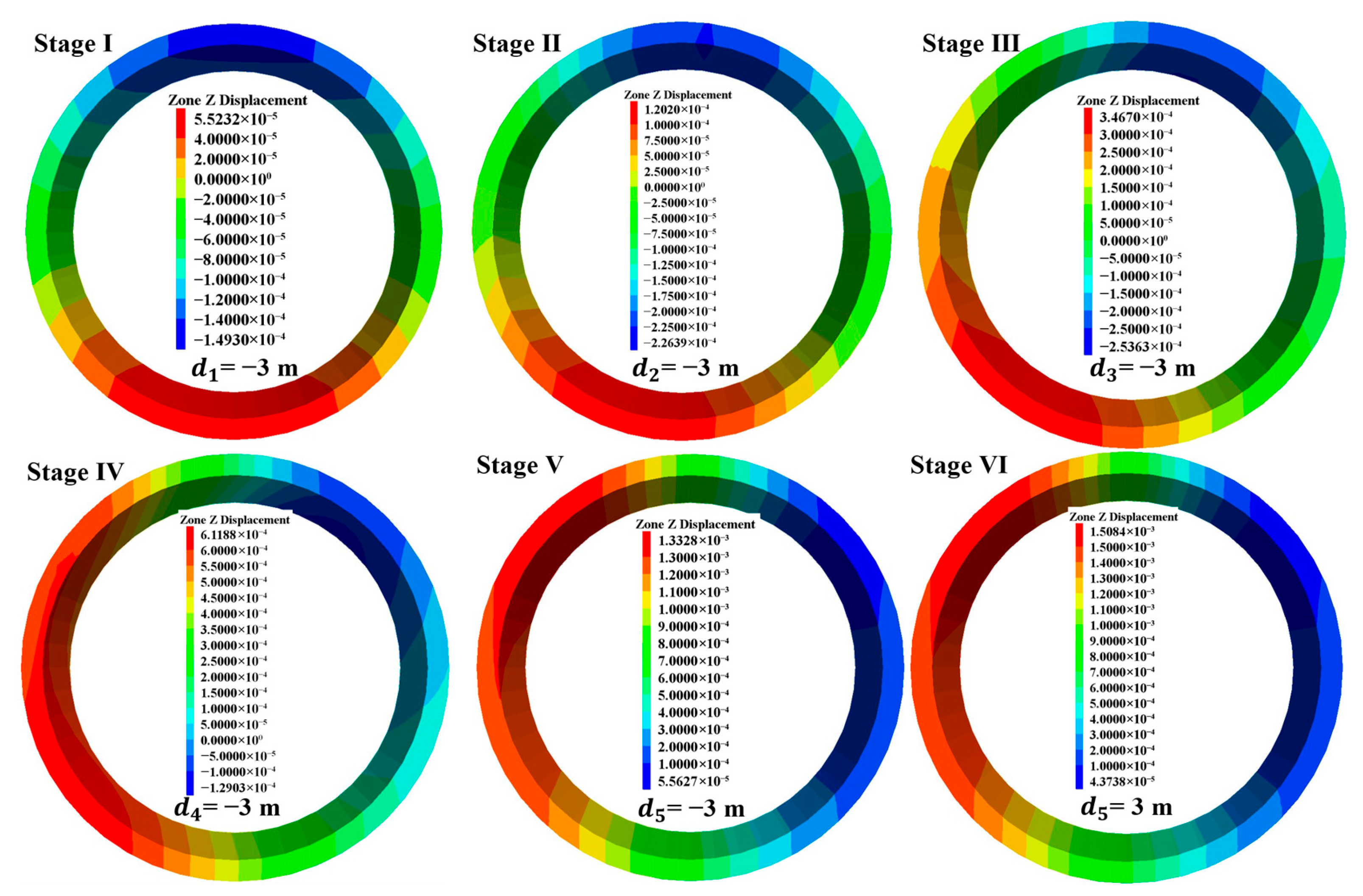

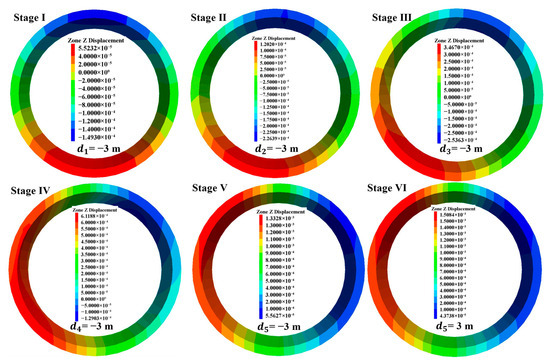

Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of vertical displacement in the target segment during the construction process. From the displacement cloud map, it could be observed that when the excavation reached Stage I, the vertical displacement of the segment exhibited the typical distribution characteristics of arch bottom heave and arch crown settlement, with the displacement field showing left-right symmetry in the horizontal direction. As the excavation progressed from Stage I to Stage III, the distribution of the surrounding rock pressure acting on the segment underwent significant changes. The sequential unloading of the surrounding rock in Sections 1 and 2 caused the maximum uplift value and settlement values of the segment to shift along the circumferential direction gradually. Notably, the rate of increase in heave was notably higher than that of settlement, reflecting the asymmetric deformation characteristics of the segment during the unloading of the arch surrounding rock. Despite this, the overall magnitude of the vertical displacement of the segment remained small, maintaining good stability. When the excavation reached Stage VI (removal of temporary supports), the vertical displacement of the segment reached its maximum value, with the maximum vertical displacement being 1.51 mm. At this stage, the deformation pattern of the segment was dominated by overall heave, with the maximum heave location evolving from the primary arch bottom region to the left arch shoulder. This phenomenon highlighted the substantial impact of surrounding rock unloading on the deformation of the segment.

Figure 5.

Evolution patterns of vertical displacement of the target segment during different construction stages.

Figure 6 presents the evolution of horizontal displacement within the target segment during the construction sequence. During Stage I, prior to excavation of the overlying arch surrounding rock, the target segment manifested horizontal convergence towards the central axis, exhibiting symmetrical displacement distribution bilaterally. Upon advancing to Stage II, maximum horizontal convergence occurred at the left arch waist region, accompanied by a shift in the convergence direction. As excavation progressed to Stage V, horizontal displacement at the lower left arch waist increased substantially due to the excavation of Section 4’s surrounding rock, increasing by 500%. By Stage VI, horizontal displacement of the target segment progressively increased, attaining the maximum value observed throughout the excavation process. Further analysis indicates that excavation of Sections 1 and 2 surrounding rock elicited the most pronounced horizontal displacement response at the left arch waist of the target segment. Subsequent excavation and unloading of Sections 3, 4, and 5 surrounding rock induced progressively increasing horizontal displacement at the target segment’s right shoulder. Collectively, asymmetric excavation of the arch surrounding rock engendered a distinct asymmetric evolution pattern in the target segment’s horizontal displacement. Deformation and convergence of temporary segments under the implemented construction sequence complied with the horizontal displacement control value (5–10 mm) and vertical displacement control value (10–20 mm) stipulated for Grade III rock mass conditions in GB/T 51438-2021 “Design Code for Shield Tunnel Engineering” [25].

Figure 6.

Evolution patterns of horizontal displacement of the target segment during different construction stages.

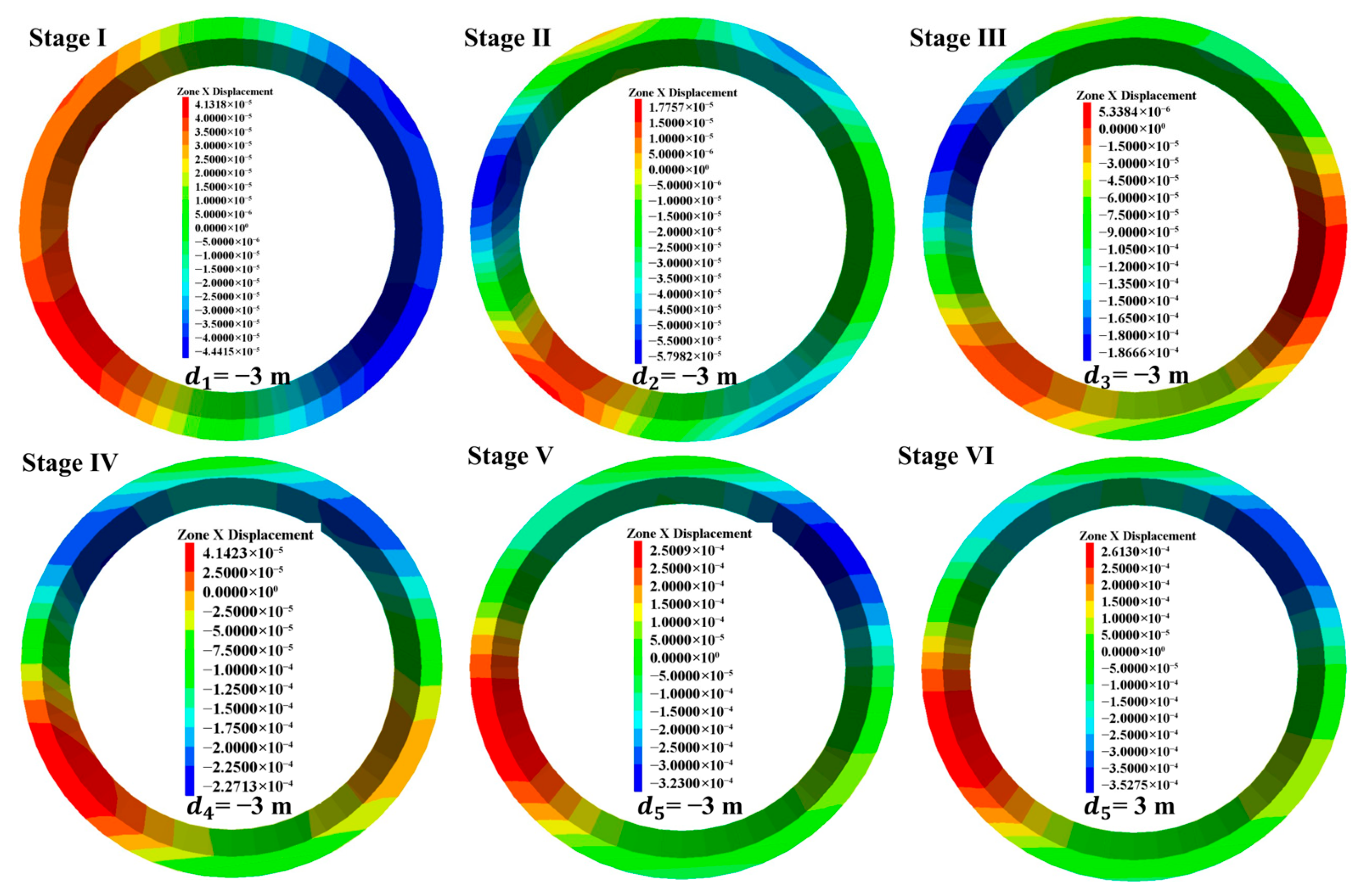

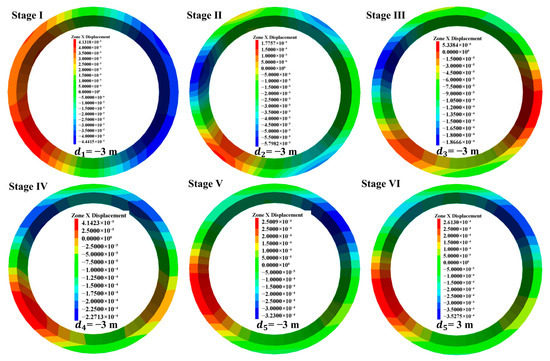

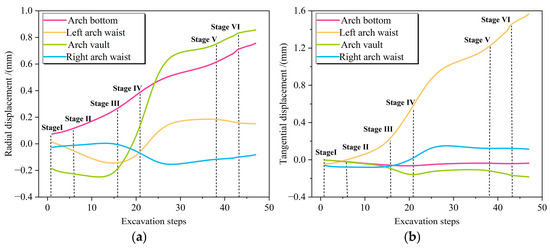

Figure 7 illustrates the evolutionary patterns of radial and tangential displacements in the target tube segment at four characteristic positions (arch bottom, left arch waist, arch vault, and right arch waist) under tunnel–station synchronous construction conditions. Distinct evolutionary patterns were observed in radial displacement across different characteristic positions. Specifically, with progressive excavation of the arch surrounding rock, radial displacement at the arch bottom exhibited gradual augmentation. By Stage IV, significant divergence emerged in radial displacement magnitudes among the four positions, with the arch vault demonstrating a pronounced increase. This indicates the arch vault constitutes the region most significantly affected by arch surrounding rock unloading. Overall, substantial positive radial displacements characterized both the arch vault and arch bottom, while the radial displacement curves at the left and right arch waists exhibited a degree of symmetry, suggesting relatively balanced radial loading states bilaterally. Analysis of tangential displacement evolution patterns (Figure 7b) reveals that the left arch waist experienced the most significant influence from arch surrounding rock unloading. Specifically, tangential displacement at the left arch waist progressively increased during construction before Stage III, while tangential displacements at other positions remained comparatively minor. Upon reaching Stage IV, however, tangential displacement at the left arch waist underwent rapid escalation, indicating substantial tangential stress concentration at this location. This resulted in pronounced heterogeneous tangential deformation characteristics across the tube segment. Based on this analysis, arch surrounding rock unloading substantially impacted both radial and tangential displacements of the target tube segment, with the arch vault and left arch waist representing the most significantly affected regions. Furthermore, the target segment exhibited marked asymmetric tangential deformation characteristics, potentially attributable to the asymmetric distribution of surrounding rock unloading during construction and the complex stress state inherent to the target segment.

Figure 7.

Deformation evolution law of the target segment under synchronous construction of the tunnel and station. (a) Radial displacement. (b) Tangential displacement.

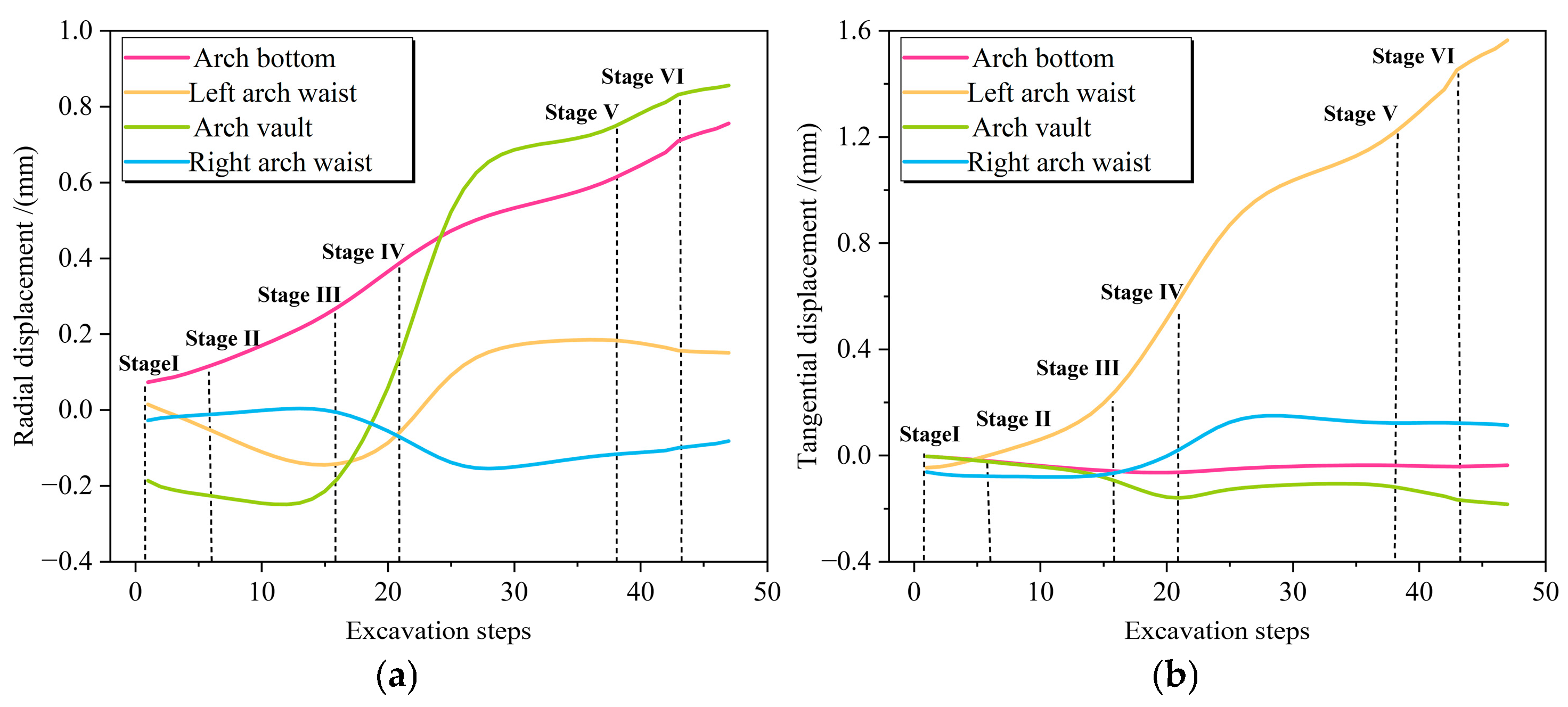

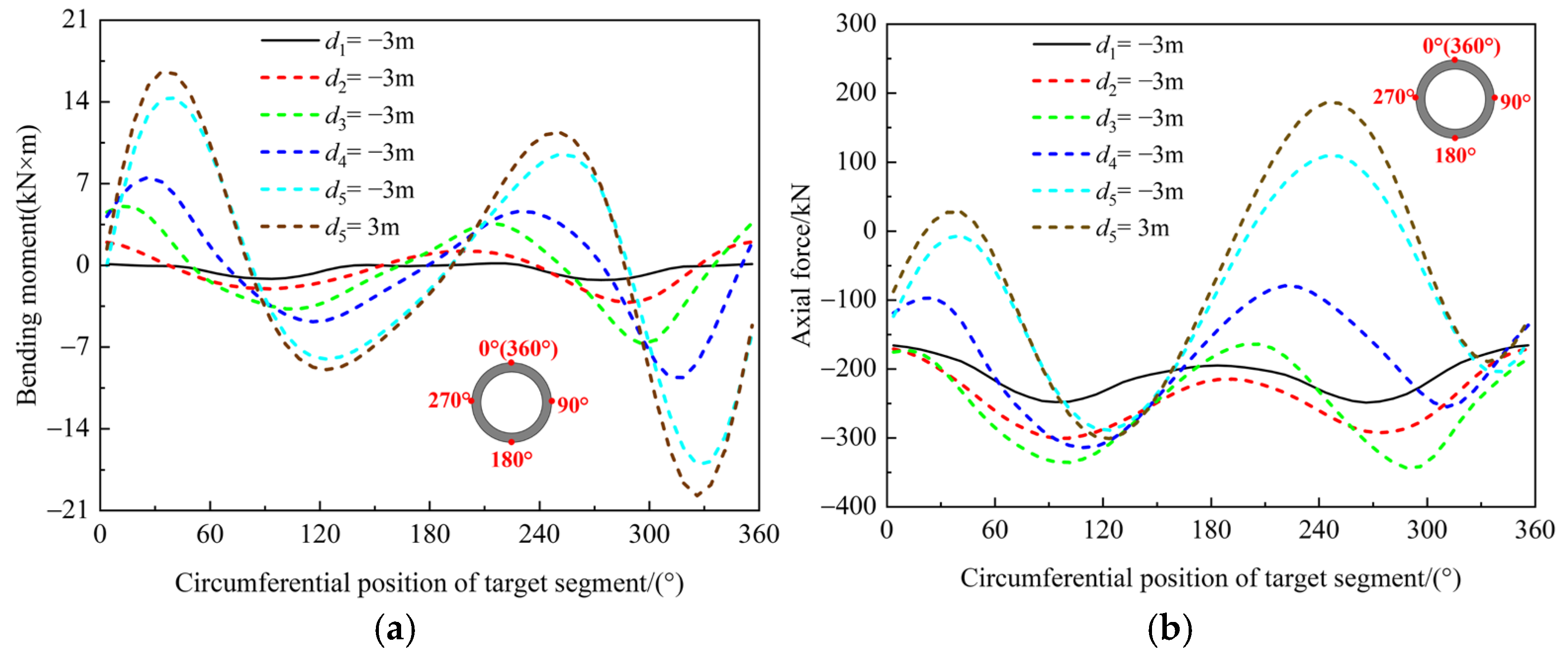

4.2. Distribution State of Bending Moments and Axial Forces

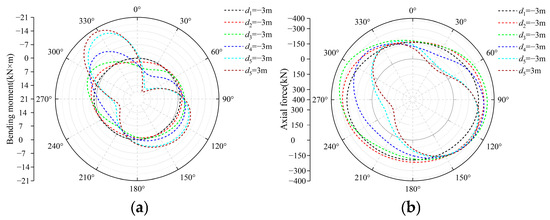

This section details the calculation of internal forces within lining segments utilizing the FISH language embedded in FLAC3D 7.0. Bending moments and axial forces for solid elements were extracted, enabling the generation of distribution maps depicting these forces in the primary lining. The bending moment convention defines positive values when the outer side experiences compression and the inner side tension; conversely, it is negative. The axial force convention defines compressive forces as negative and tensile forces as positive. Figure 8 illustrates the distribution and evolution of bending moment and axial force within the target segment during station arch excavation. Initially, the target segment exhibited negative bending moments at the left and right arch waist regions, whereas the arch crown and arch bottom primarily experienced positive bending moments, indicative of an overall compressive stress state. As the surrounding rock of the arch underwent asymmetric unloading, the target segment was progressively subjected to asymmetric loading, resulting in alterations to the bending moment and axial force distributions. Specifically, the negative bending moment at the left arch shoulder and the positive bending moment at the right arch shoulder exhibited a gradual increase, with the phenomenon of eccentric loading becoming more pronounced. Notably, following the unloading of the surrounding rock in Section 3, axial force values at the right arch shoulder and the lower part of the left arch waist decreased significantly. With advancing excavation and subsequent unloading of the surrounding rock in Section 4, the negative bending moment at the left arch shoulder and the positive bending moment at the right arch shoulder demonstrated more pronounced responses. Concurrently, the axial force response was most intense at the right arch shoulder and the lower part of the left arch waist, transitioning from compressive stress to tensile stress. The removal of temporary supports exerted a negligible influence on the bending moments and axial forces. Post-removal, the maximum negative bending moment of the target segment was −17.34 kN·m, located at the left arch shoulder, while the maximum positive bending moment was 16.36 kN·m, located at the right arch shoulder.

Figure 8.

Internal force distribution diagrams of the target segment during different construction stages. (a) Bending moment. (b) Axial force.

Figure 9 clearly delineates the evolution of bending moments and axial forces within the target segment, offering a critical visual foundation for comprehending its mechanical behavior. As depicted, the bending moment curve manifests dual positive and dual negative peaks, signifying substantial stress variations at specific locations along the segment. With the sequential unloading of the surrounding rock at the arch crown, the peak bending moments progressively intensified, indicating heightened stress concentrations induced by the unloading process. Concurrently, these four peak points exhibited a clockwise migration, reflecting dynamic adjustments in the segment’s stress distribution. Throughout distinct stages of surrounding rock unloading, the compressive stress profile of the target segment demonstrated characteristic trends. Initial unloading of Section 1’s surrounding rock resulted in a global increase in compressive stress. Subsequent unloading of Section 2’s surrounding rock precipitated a reduction in compressive stress within the 150–250° sector, while compressive stress increased elsewhere. Progressive unloading of Sections 3, 4, and 5 surrounding rock led to a further overall decrease in the segment’s compressive stress. Notably, axial forces at the 40° and 240° positions transitioned from compressive to tensile stress states, signifying a fundamental shift in load-bearing mechanism at these critical locations.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the bending moment and axial force of the target segment. (a) Bending moment. (b) Axial force.

5. Discussion

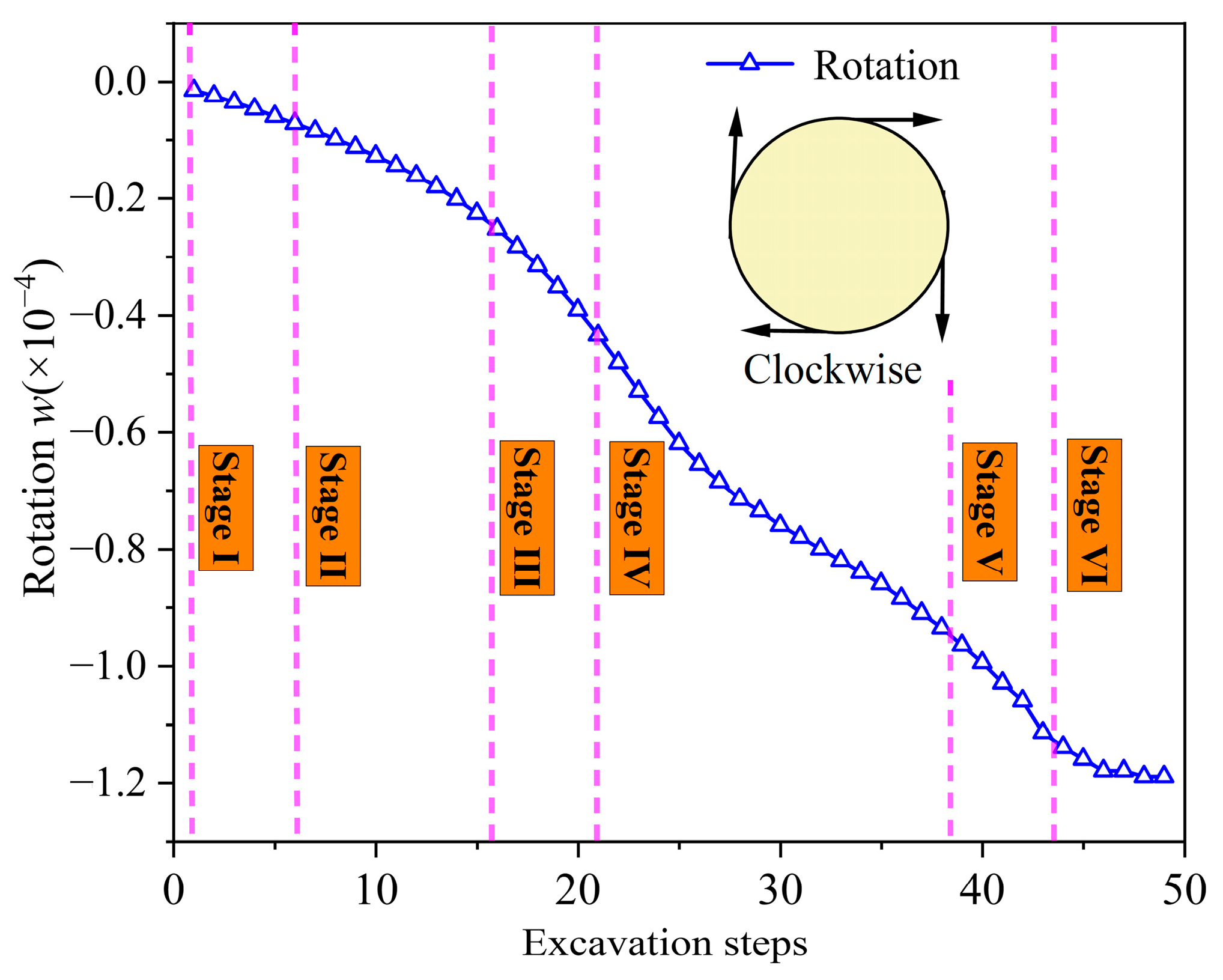

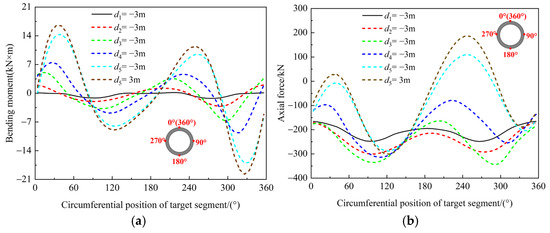

To achieve a more comprehensive characterization of deformation in target segments during tunnel–station synchronous construction, Zhang et al. [26] quantitatively assessed the torsional deformation of the tunnel utilizing the rotation index ω, defined by:

where ω represented the rotation index; ux1 was the horizontal displacement at the crown of the target segment; ux2 was the horizontal displacement at the invert of the target segment; uy1 was the vertical displacement at the right arch waist of the target segment; uy2 was the vertical displacement at the left arch waist of the target segment; and D was the outer diameter of the target segment. Figure 10 shows the relationship between the rotation index ω and the construction progress under different working conditions. A positive ω indicated that the target segment was rotating counterclockwise, while a negative ω indicated a clockwise rotation. As the crown was progressively excavated, the target segment underwent a clockwise torsional deformation, and the torsion value increased gradually. However, the rate of increase in torsion varied significantly across different construction stages.

Figure 10.

Rotation index evolution curve of the target segment under tunnel–station synchronous construction conditions.

During Stage I to Stage III, the rate of increase in torsion for the target segment remained relatively modest. This was primarily because the crown rock mass above the segment had not yet been fully unloaded during these stages, resulting in relatively uniform loading on the segment and a more balanced overall stress distribution. However, upon advancing to Stage IV, the rate of torsional deformation increase became markedly higher. This acceleration was attributable to the unloading of the surrounding rock mass in Section 3, which induced an uneven load distribution across the segment’s centerline, consequently leading to a pronounced clockwise torsion of the target segment. Compared to Stage V, the rate of torsional deformation increase began to decline in Stage VI and subsequently stabilized throughout the ensuing construction steps. This phenomenon indicated that while crown excavation induced irreversible torsional deformation in the target segment, the torsional value ultimately stabilized following complete rock mass unloading, demonstrating that the segment retained its structural stability.

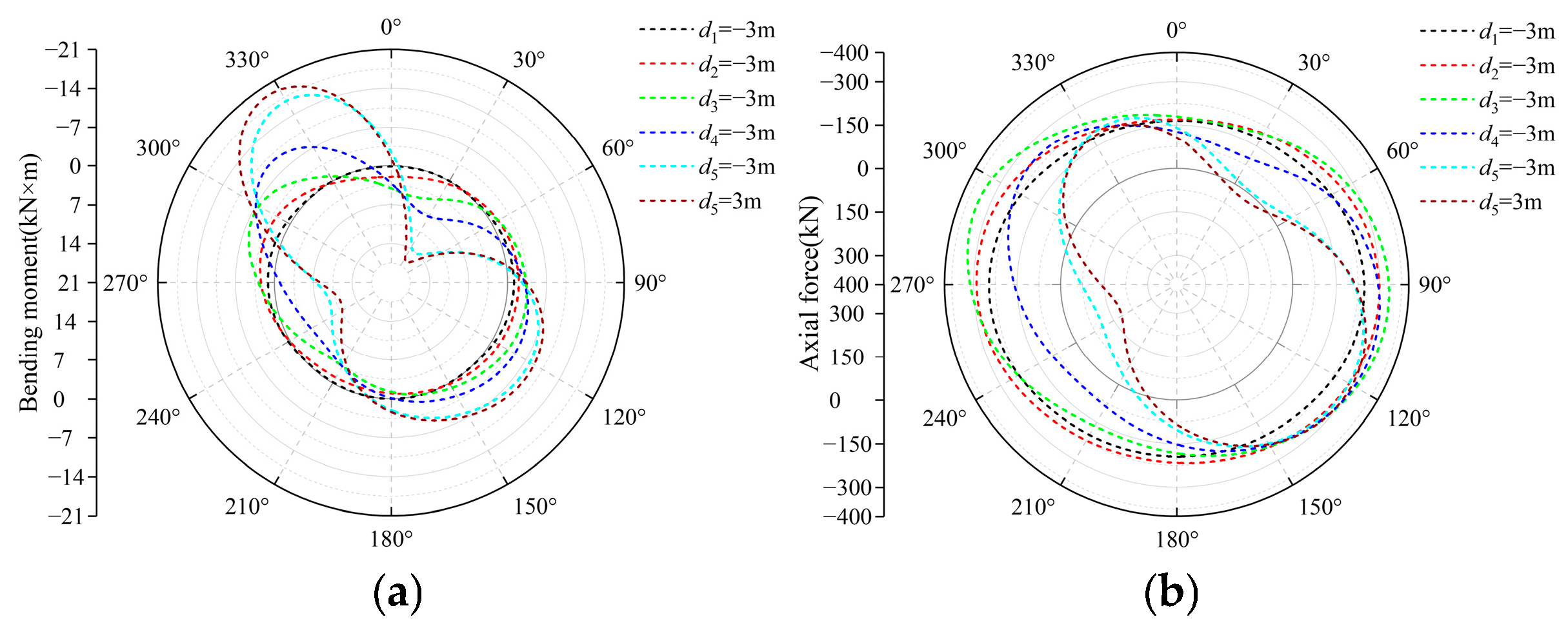

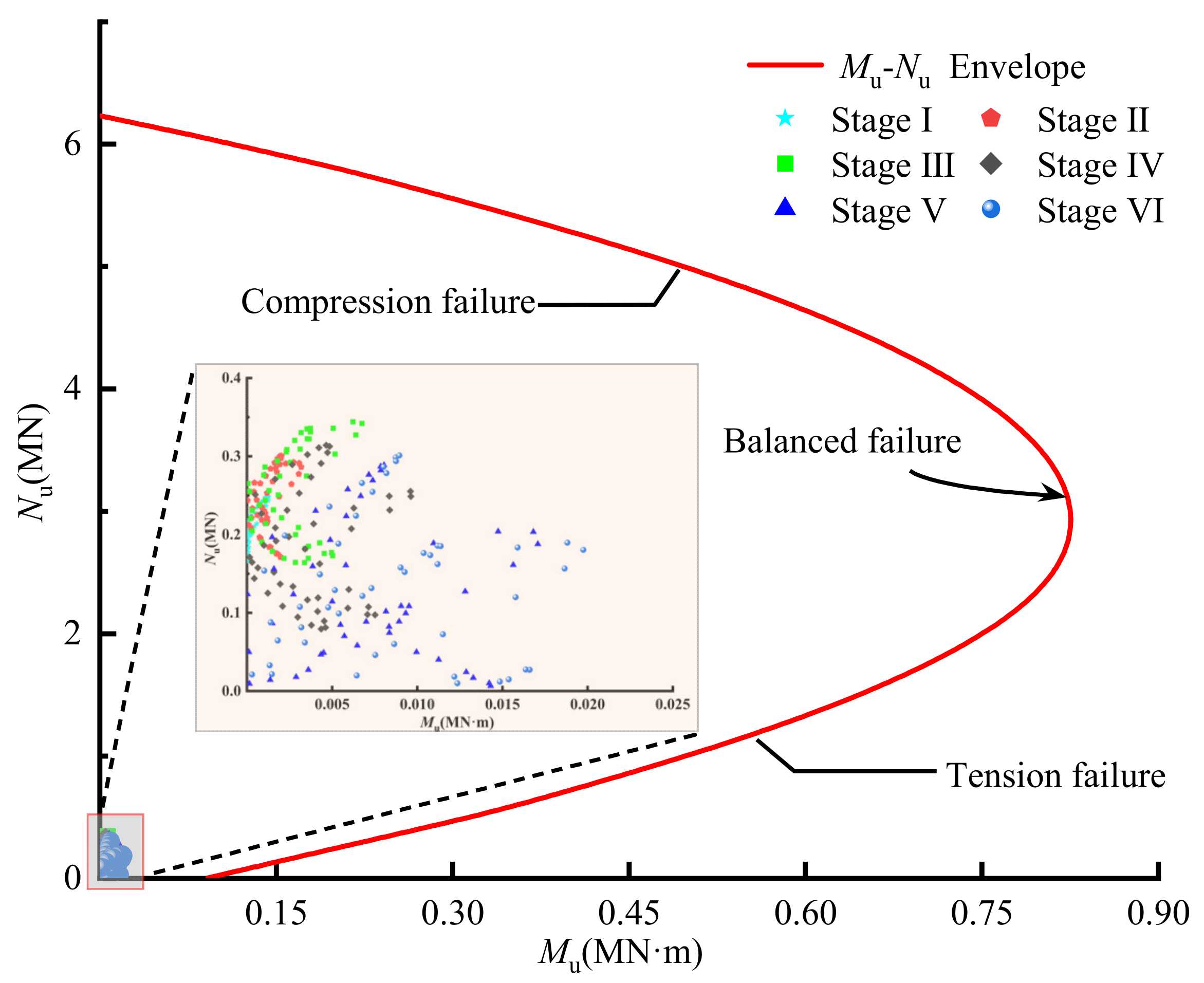

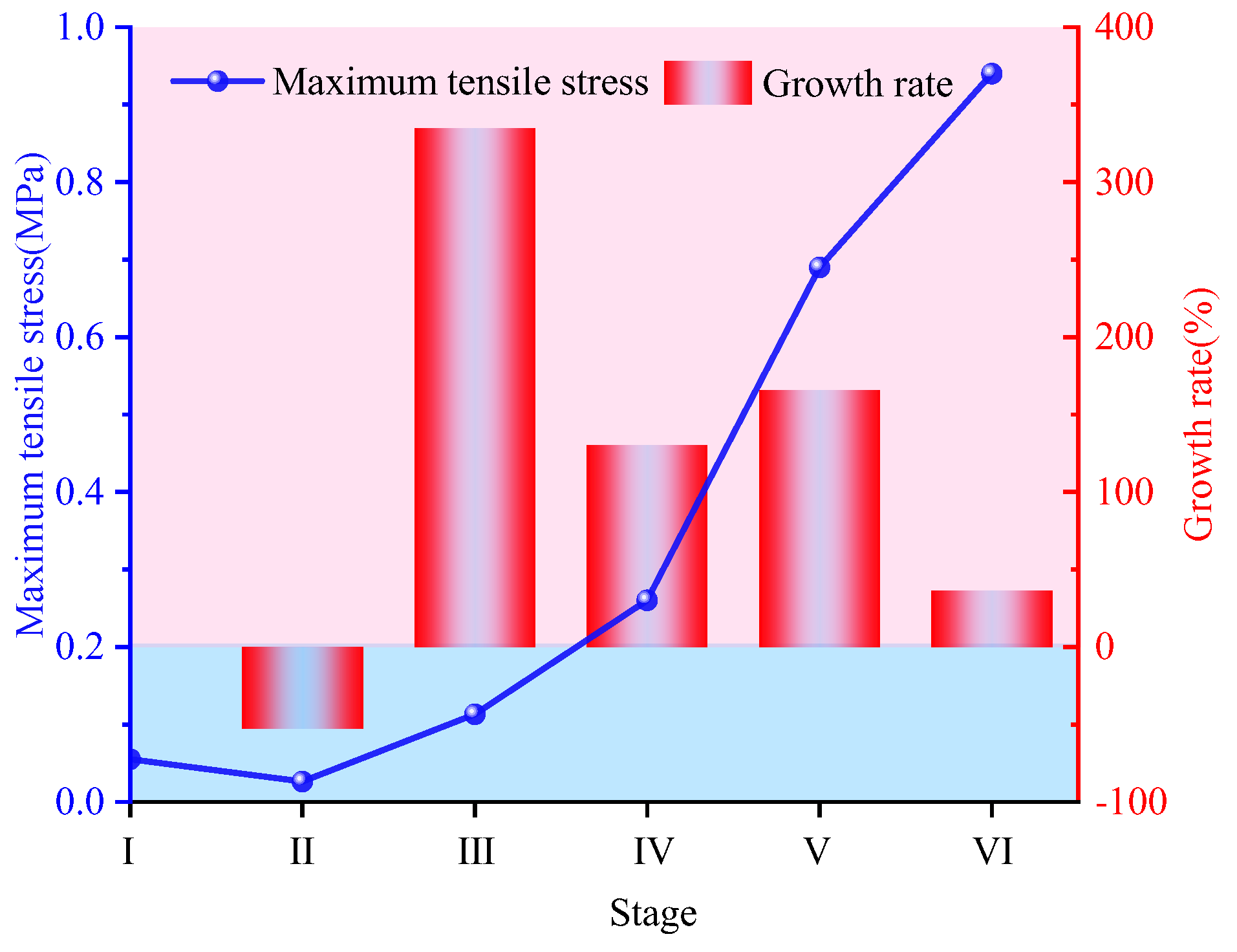

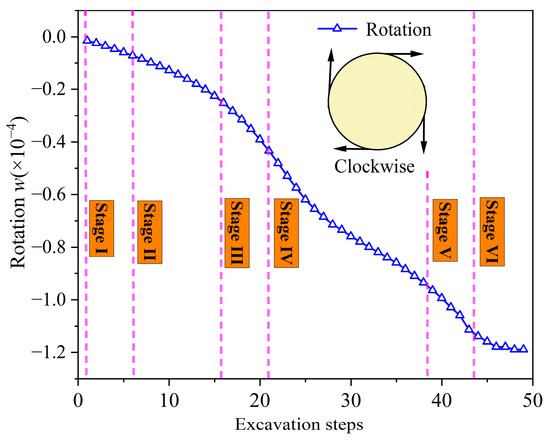

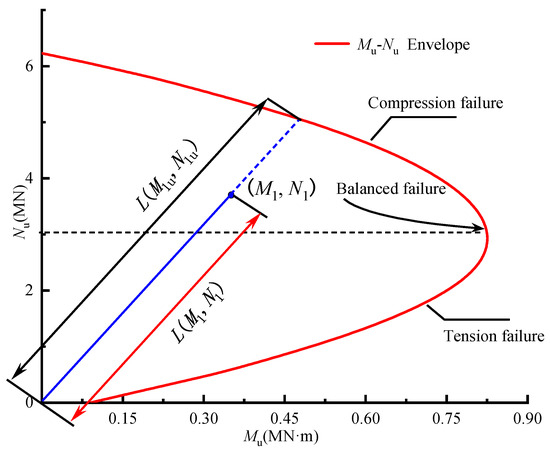

The bending moment–axial force interaction diagrams for support segments possess significant research value within the structural mechanics analysis of tunnel engineering, offering profound theoretical and practical implications. In tunnel–station synchronous construction, the mechanical properties of target segments directly influence structural stability and safety during the construction process. As the primary controlling parameters of internal forces in the cross-section of support segments, bending moments and axial forces not only characterize the stress state under external loads but also determine potential failure modes, including compression failure, tension failure, and balanced failure. Consequently, constructing bending moment–axial force interaction diagrams enables the systematic description of internal force responses in support segments under varied load combinations, providing theoretical support for limit state design and enhancing the precision and safety of tunnel–station synchronous construction design.

For a given reinforced concrete member, we calculated the relationship between the design value of compressive bearing capacity (Nu) and the design value of flexural bearing capacity (Mu) based on its material parameters, cross-sectional dimensions, and reinforcement arrangement. Figure 11 illustrates the evolution of bending moments and axial forces in the target segments during different stages of tunnel–station synchronous construction. From Stage I to Stage III, the fluctuations in bending moments and axial forces of the target segments were relatively small, indicating that the construction during this stage had a limited impact on the stress state of the segments. However, as the construction progressed into Stage IV and Stage V, the fluctuations in bending moments and axial forces significantly increased. Nonetheless, these values remained within the predefined bending moment envelope curves, suggesting that the internal force responses during tunnel–station synchronous construction did not exceed the ultimate bearing capacity limits of the segments. This ensured the safety and stability of the structure throughout the construction process.

Figure 11.

Relationship between the bending moment and axial force of the target segment and the envelope curves during different construction processes.

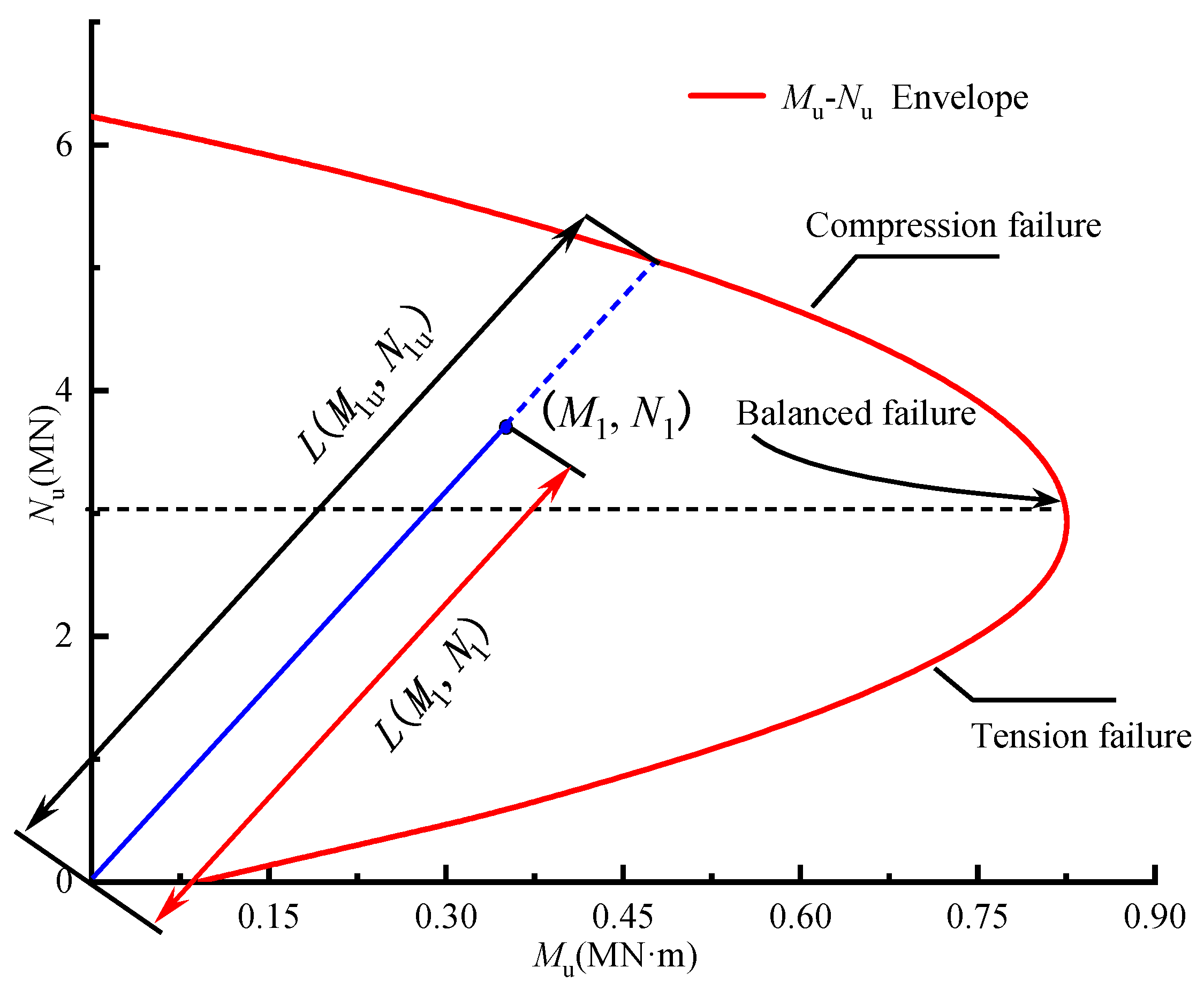

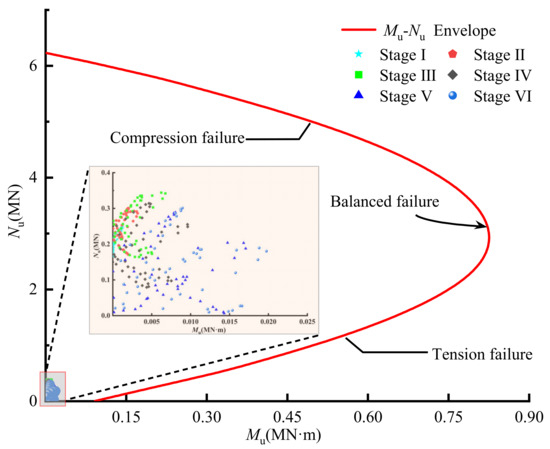

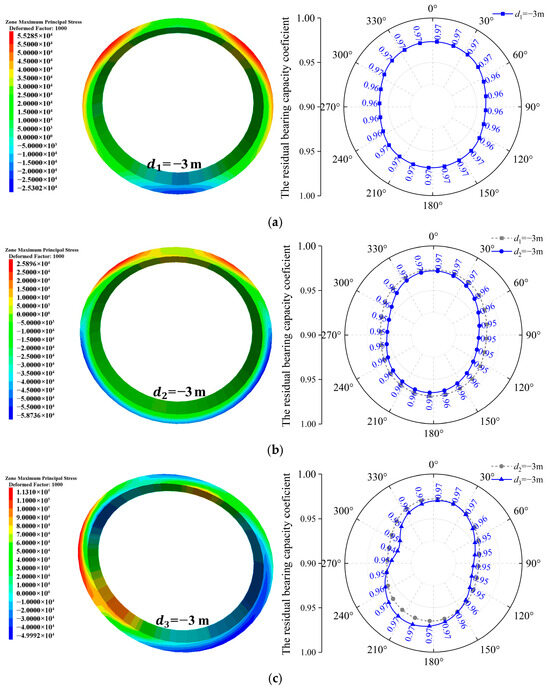

To better evaluate the stress state of the target segments, and following previous research [27], the residual bearing capacity coefficient was defined as the ratio of the residual bearing capacity along a specified eccentric path at a given moment to the ultimate bearing capacity, as illustrated in Figure 12. The calculation was expressed as follows:

where denoted the distance between point and the origin (0, 0), and denoted the distance between point and the origin (0, 0). The minimum value among all parts of an entire segment ring was taken as the residual bearing capacity coefficient, i.e.,

Figure 12.

The residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment.

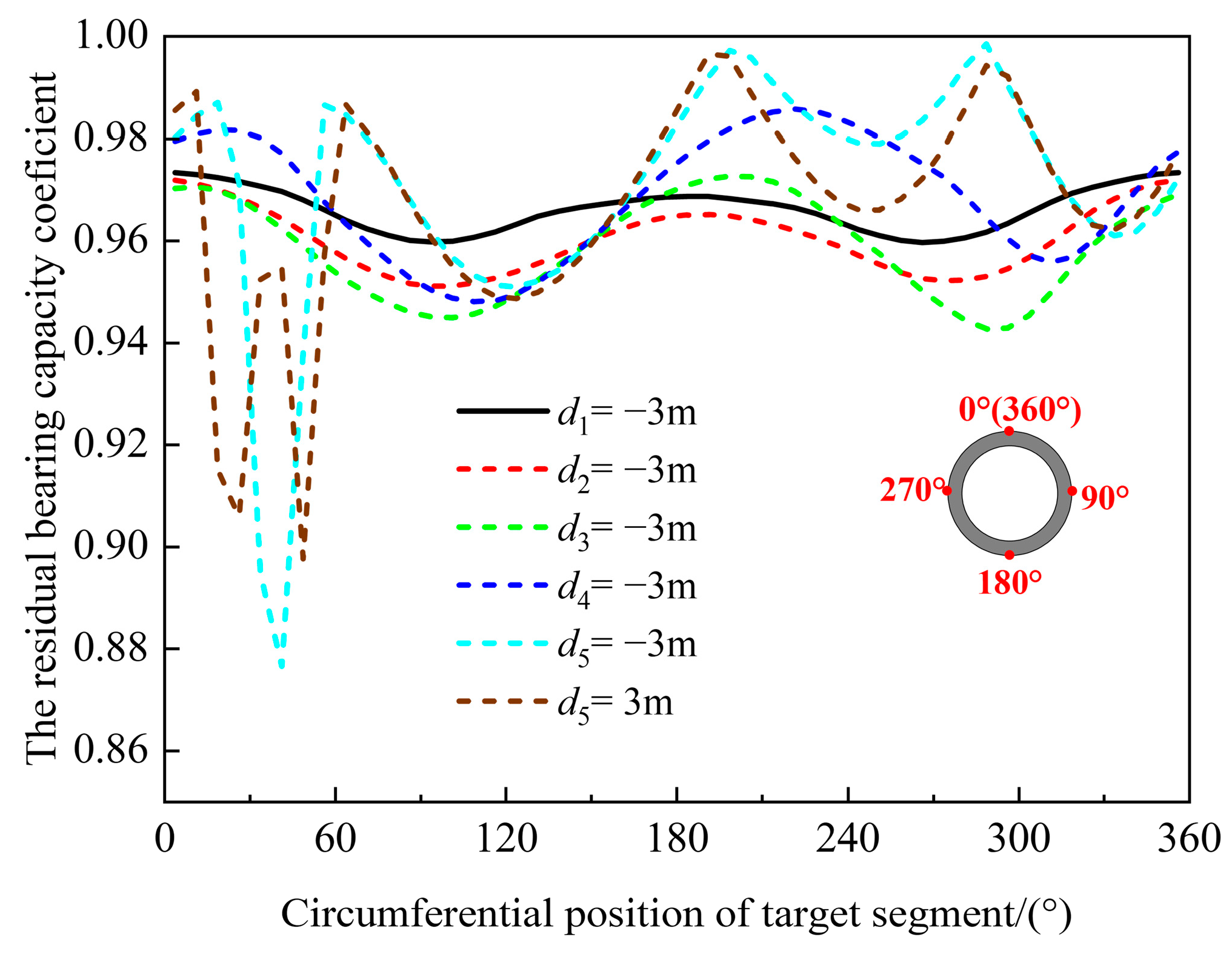

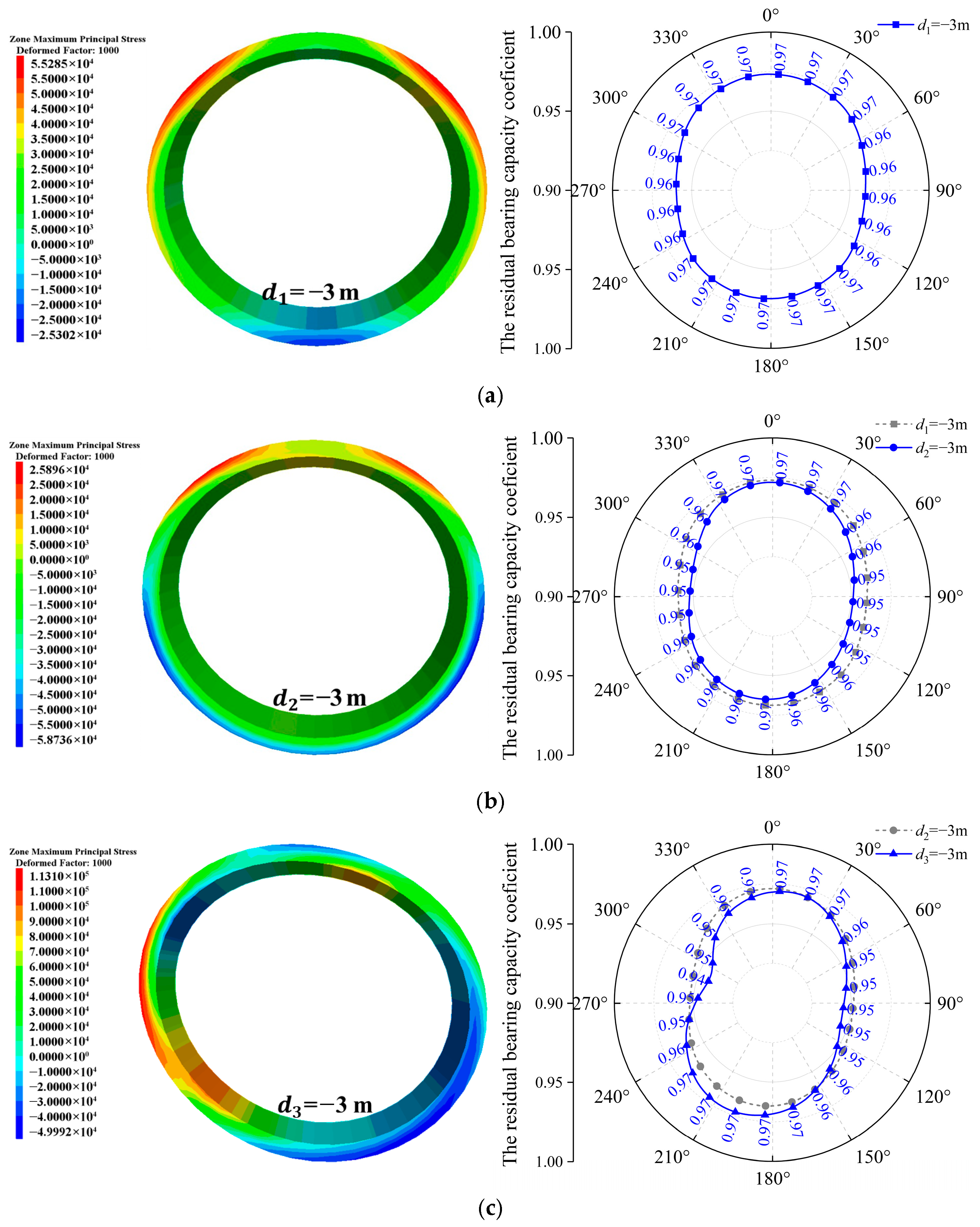

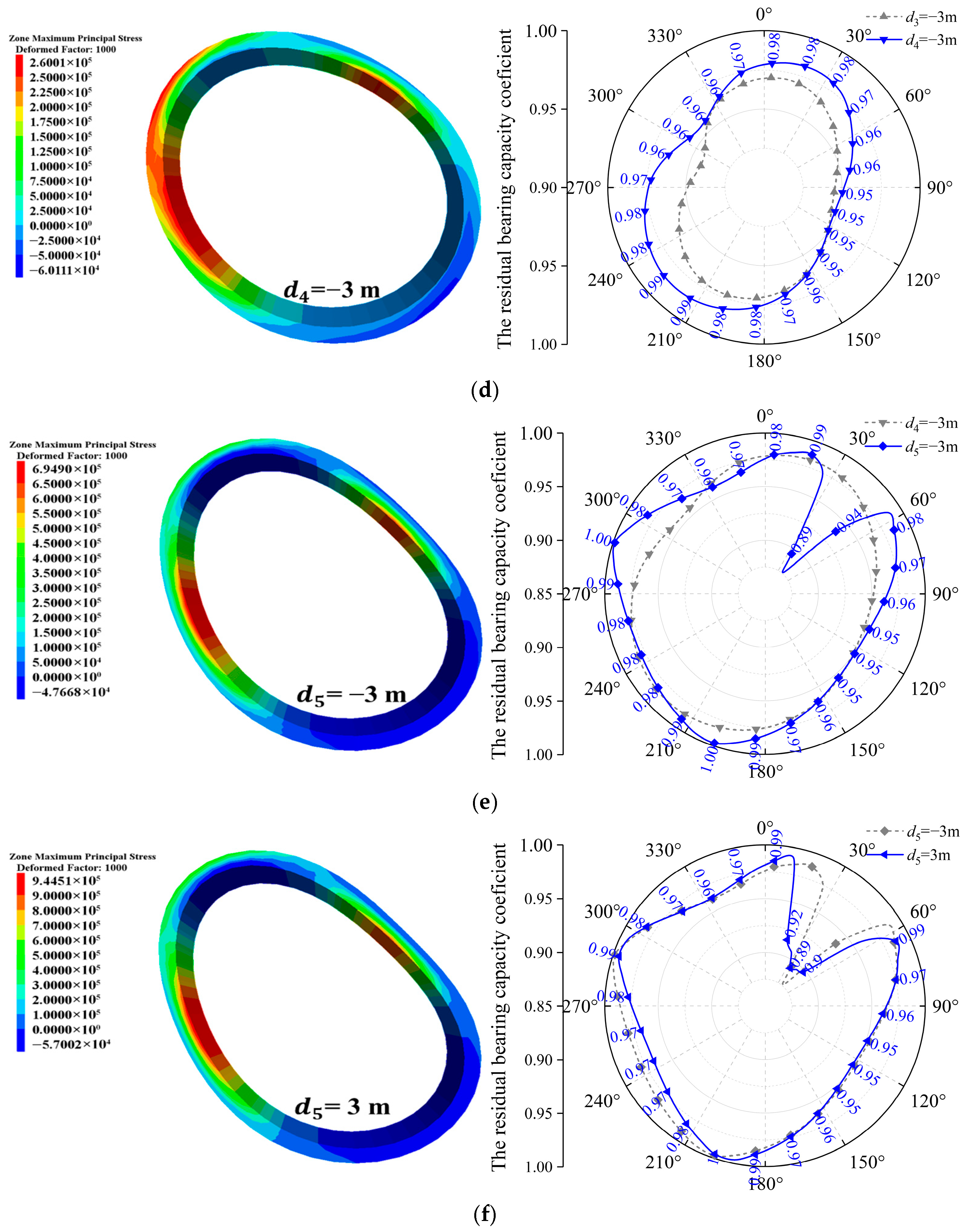

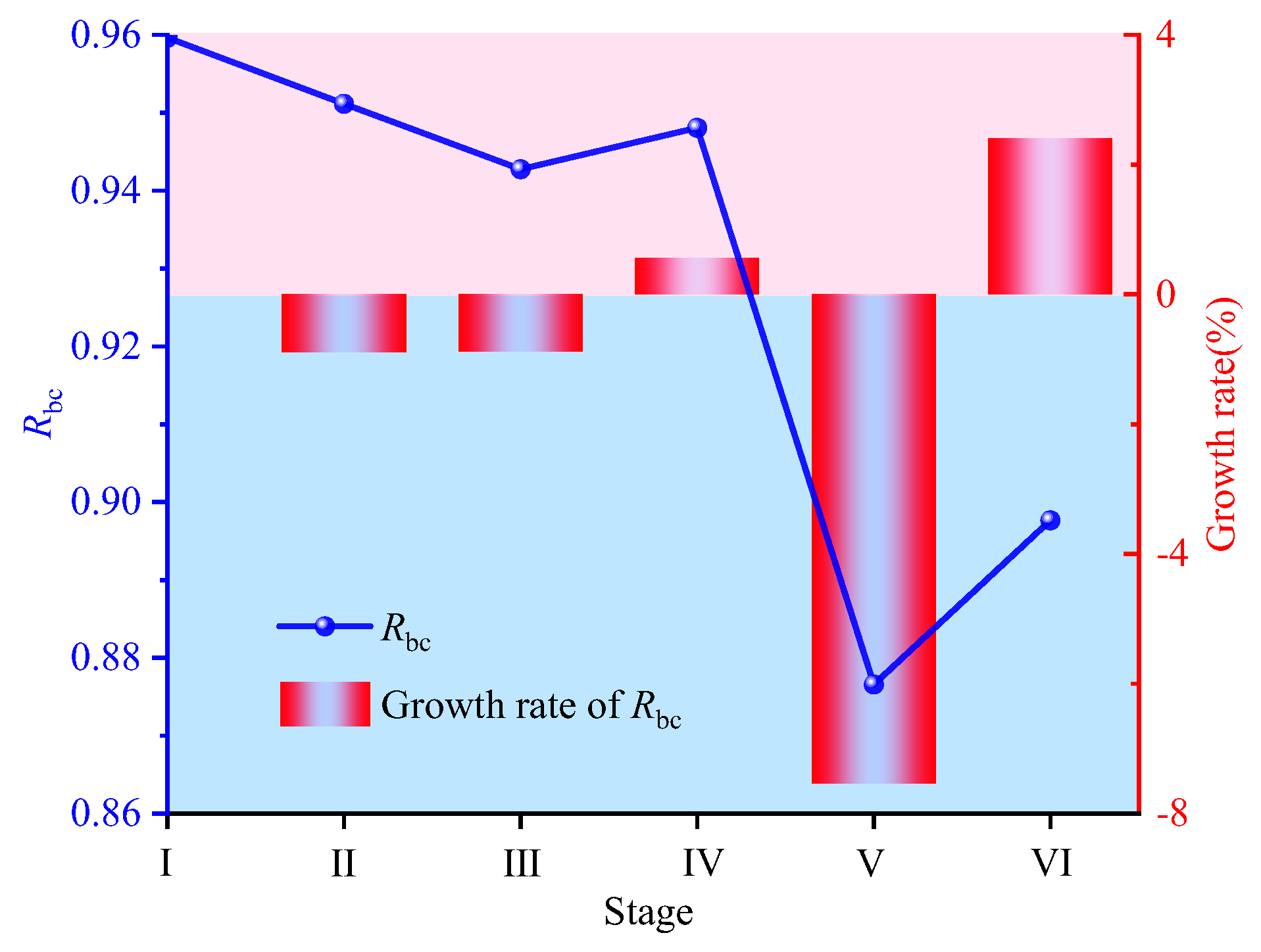

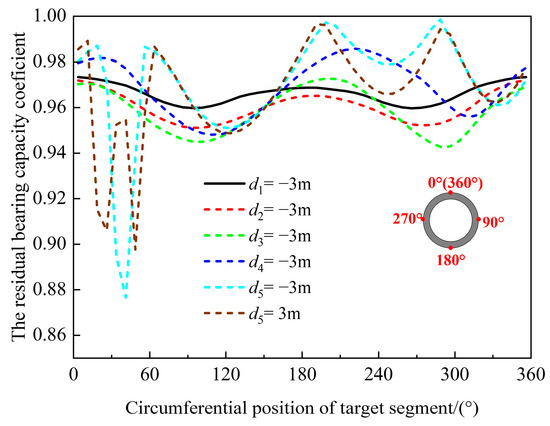

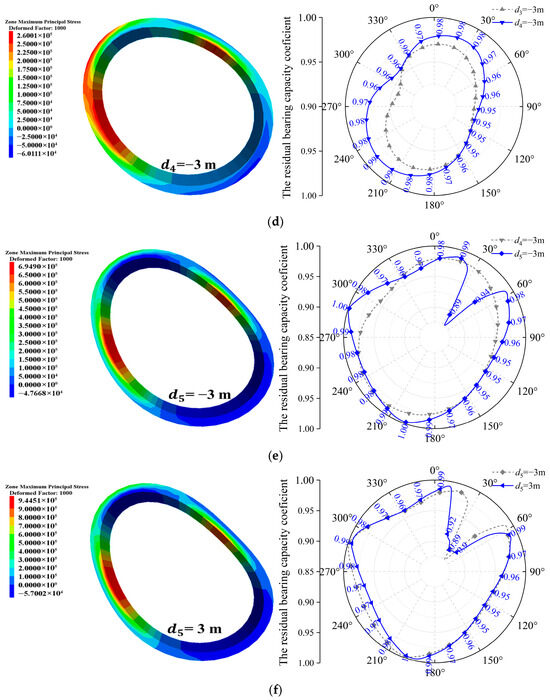

Figure 13 and Figure 14 illustrate the distribution and evolution of the maximum tensile stress and the residual bearing capacity coefficient within the target segment throughout distinct stages of tunnel–station synchronous construction. Upon reaching Stage I of arch construction, the target segment exhibited relatively modest maximum tensile stress, primarily localized near the arch shoulders adjacent to the surrounding rock. The residual bearing capacity coefficient remained elevated, ranging between 0.96 and 0.97, indicating substantial structural safety reserves at this phase. Progressing to Stage II, the residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment manifested a general declining trend, reflecting the progressive influence of surrounding rock unloading on structural performance. When arch construction advanced to Stage III, a significant shift occurred in the location of the maximum tensile stress. It migrated from both arch shoulders to the left arch waist proximate to the surrounding rock, with its magnitude increasing by a factor of 3.35 relative to the preceding stage. Concurrently, the residual bearing capacity coefficient exhibited differentiated spatial responses: it decreased within the angular ranges of 30–150° and 258.75–18.75°, while increasing within the 153.75–258.75° range. Notably, the position of peak tensile stress coincided spatially with the region of diminished residual bearing capacity (258.75–18.75°), suggesting this zone constituted a structural vulnerability. At Stage IV, the maximum tensile stress emerged on the segment’s inner surface. Conversely, the overall residual bearing capacity coefficient increased, attributable primarily to the unloading effect induced by surrounding rock excavation in Section 3, thereby enhancing segment safety. During Stage V, unloading in Section 4 predominantly affected the residual bearing capacity coefficient locally within the 18.75–48.75° arc. The minimum residual bearing capacity coefficient decreased to 0.88, representing a 7% reduction relative to the Stage IV minimum. Simultaneously, the maximum tensile stress increased from 0.26 MPa to 0.69 MPa, a 1.65-fold increase, signifying a substantial alteration in the regional stress state. Upon reaching Stage VI and following temporary support removal, the residual bearing capacity coefficient diminished at multiple segment locations. However, the absolute minimum residual bearing capacity coefficient demonstrated an increasing trend.

Figure 13.

Evolution process of the residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment.

Figure 14.

Evolution patterns of the maximum principal stress and the residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment during different construction stages. (a) Stage I; (b) Stage II; (c) Stage III; (d) Stage IV; (e) Stage V; (f) Stage VI.

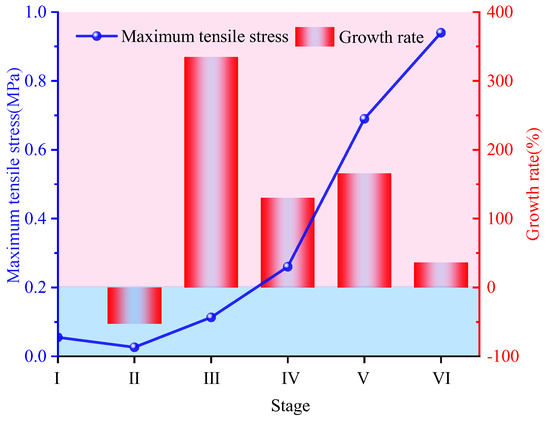

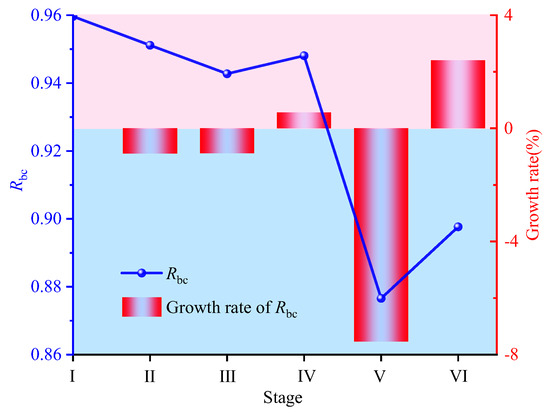

To facilitate a more intuitive analysis of the variation patterns in the maximum tensile stress and residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment during tunnel–station synchronous construction, this study generated line charts and bar charts depicting the variations and growth rates of these parameters across each construction stage. As illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16, when construction progressed to Stage II, the unloading effect of the surrounding rock in Section 1 resulted in a slight decrease in the maximum tensile stress of the target segment, and the residual bearing capacity coefficient also demonstrated a declining trend. From Stage II to Stage VI, the maximum tensile stress of the target segment exhibited a gradual increase, with the highest growth rate observed at Stage III relative to the preceding stage. Upon reaching Stage V, the unloading of the surrounding rock in Section 4 led to a 7% decrease in the residual bearing capacity coefficient, which represented the highest rate among all stages. This observation indicates that the unloading during this stage significantly impacted the bearing capacity of the target segment in specific local regions, necessitating particular attention to the stress state and safety of these areas. Furthermore, during Stage IV and Stage VI, the residual bearing capacity coefficient displayed an increasing trend, suggesting an enhancement in the safety reserve of the segment during these phases.

Figure 15.

Evolution patterns of maximum tensile stress of the target segment during different construction stages.

Figure 16.

Evolution patterns of the residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment during different construction stages.

Currently, the conventional “tunnel-first, station-later” methodology remains prevalent in the construction of metro stations within tunnel engineering projects [28]. However, this approach frequently results in extended construction durations and may induce construction coordination challenges at the tunnel–station interface. To address this technical limitation, the tunnel–station synchronous construction method proposed in this study was successfully implemented in the Qingdao Metro project, achieving a significant reduction in overall construction time. In practical engineering applications, inadequate comprehension of the mechanical response characteristics of segments under tunnel–station synchronous construction conditions has often led to excessively conservative temporary segment designs, resulting in unnecessary cost overruns. Using a specific line of the Qingdao Metro as a case study, the initial design specified a C50 concrete strength grade for temporary segments. Through a comprehensive investigation into the stress behavior of segments under synchronous construction conditions, it was determined that the strength grade of temporary segments could be optimized to C30 while maintaining structural integrity and satisfying construction requirements.

6. Conclusions

This study utilized FLAC3D to analyze the displacement, internal forces, maximum tensile stress, and residual bearing capacity coefficient of the right-line target segment at various stages of tunnel–station synchronous construction. The aim was to elucidate the mechanical response characteristics of the target segment during the unloading of the arch surrounding rock. The specific conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The tunnel–station synchronous construction method offers notable advantages in practical engineering applications. This study investigated the mechanical response characteristics of target segments during different stages of this construction process. As excavation advanced, significant variations were observed in the displacement, internal forces, and residual bearing capacity coefficient of the target segment. The vertical displacement of temporary segments was considerably affected by the unloading of the arch surrounding rock, while the horizontal displacement exhibited an asymmetric evolution pattern, with the arch waist region showing the highest sensitivity.

- (2)

- Asymmetric unloading during station arch excavation led to an increase and clockwise shift in the bending moments of the target segment. Axial forces transitioned from compression to tension at specific locations (40° and 240°), whereas the removal of temporary supports had a limited influence. The maximum tensile stress of the target segment increased by 3.35 times in Stage III and reached 0.69 MPa in Stage V, representing a 1.65-fold increase compared to the previous stage. Although the residual bearing capacity coefficient generally satisfied safety requirements throughout construction, it decreased to a minimum value of 0.88 in Stage V (7% reduction from Stage IV).

- (3)

- In the Qingdao Metro project, the tunnel–station synchronous construction method achieved a time saving of 4.5 months compared to the conventional construction method (where the TBM must remain idle until the main station structure is completed). Under the conventional approach, the TBM idle time amounts to approximately 90 days for station construction, followed by an additional 44 days for completing the tunnel excavation through the station section. Therefore, adopting the synchronous construction method significantly reduces the overall construction timeline.

- (4)

- Through an in-depth analysis of the loading characteristics of the target segment under synchronous construction conditions, the design of temporary segments could be optimized, reducing the strength grade from C50 to C30. This optimization ensured structural stability and met construction requirements while achieving a reasonable control of costs. The numerical simulation methodology and findings of this study could provide valuable references for design optimization and risk control in the integrated construction of metro tunnels and stations in similar complex urban environments.

Future research could further explore the effects of different station geometries on mechanical responses, optimize anchor bolt parameter design, and conduct comparative validation between field monitoring data and numerical models to enhance prediction accuracy and engineering applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and Y.L.; Methodology, S.Z. (Shilin Zhang) and S.Z. (Sulei Zhang); Software, X.S. and X.L.; Validation, Y.L., X.S., Y.C. and X.L.; Formal analysis, X.H.; Resources, Y.L., S.Z. (Shilin Zhang) and S.Z. (Sulei Zhang); Data curation, X.H. and S.Z. (Shilin Zhang); Writing—original draft, X.H., Y.L., S.Z. (Shilin Zhang) and Y.C.; Writing—review and editing, X.H. and S.Z. (Sulei Zhang); Supervision, S.Z. (Sulei Zhang); Project administration, S.Z. (Sulei Zhang); Funding acquisition, S.Z. (Sulei Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. ZR2025MS727, ZR2024QE001), the China Qingdao Metro Research Project (No. M5-ZX-2024-031), and the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2020YQ43).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xusu He and Xuantao Shi were employed by the company China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group Co., Ltd. Authors Yang Liu, Shilin Zhang, Yanhua Cao and Xiaowei Li were employed by the company Qingdao Metro Group Co., Ltd. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, G.; Li, C.; Shao, X.; Zhen, F.; Huang, Y. A New Type of Sustainable Operation Method for Urban Rail Transit: Joint Optimization of Train Route Planning and Timetabling. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Li, S.; Sun, W.; Ji, X. Assessment and Spatial Variation Analysis of the Collaborative Development Potential between Underground Public Spaces and Urban Rail Transit in China’s Urban Central Areas. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 158, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, M.H.; Dadizadeh, S. Study on the Effect of a New Construction Method for a Large Span Metro Underground Station in Tabriz-Iran. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2010, 25, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F.; He, S.; Wang, E.; Zhou, H. Enlarging a Large-Diameter Shield Tunnel Using the Pile-Beam-Arch Method to Create a Metro Station. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 49, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobashi, H.; Shiratori, A.; Miyama, D.; Nagura, H.; Miyawaki, T. Design and Construction of Enlarging Shield Tunnel Sections of Large Dimensional Shield Tunnels for the Non-Open-Cut Method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2006, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; He, C. Numerical Analysis on the Mechanical Performance of Supporting Structures and Ground Settlement Characteristics in Construction Process of Subway Station Built by Pile-Beam-Arch Method. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 1690–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Fang, Q.; Zheng, H. Challenges and Countermeasures for Using Pile-Beam-Arch Approach to Enlarge Large-Diameter Shield Tunnel to Subway Station. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 98, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Su, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Gao, H.; Yang, W. Mechanical Performance of a Prefabricated Subway Station Structure Constructed by Twin Closely-Spaced Rectangular Pipe-Jacking Boxes. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 135, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Chen, T. Subway Station Construction Using Combined Shield and Shallow Tunnelling Method: Case Study of Gaojiayuan Station in Beijing. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 82, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, X.; Su, D.; Liu, S.; Sun, B.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Zhou, S. Low-Carbon Effects of Constructing a Prefabricated Subway Station Using a Trenchless Method: A Case Study in Shenzhen, China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 144, 105557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Zhao, C.; Jia, C.; Shi, C. Study on the Geological Adaptability of the Arch Cover Method for Shallow-Buried Large-Span Metro Stations. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; He, W.; Fei, M. Study on Mechanical Characteristics of Support System for Shallow-Buried Single-Arch Subway Station in Rock Stratum. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Jiang, A. Study on the Stability of a Large-Span Subway Station Constructed by Combining with the Shaft and Arch Cover Method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 127, 104582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.W.; Fong, K.Y.; Liu, H.L. The Effects of Existing Horseshoe-Shaped Tunnel Sizes on Circular Crossing Tunnel Interactions: Three-Dimensional Numerical Analyses. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Q. Behaviors of Existing Twin Subway Tunnels Due to New Subway Station Excavation below in Close Vicinity. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 81, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, T.; Chang, W.; Han, Y.; Fu, C.; Yu, Z. Mechanical Response of Horseshoe-Shaped Tunnel Lining to Undercrossing Construction of a New Subway Station. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 128, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.W.; Ma, S.Y.; Liu, Z.X.; Chen, Y.B.; Lu, C.R.; Song, Y.J.; Li, X.J.; Zhao, L.A. LSTM-Based Deformation Forecasting for Additional Stress Estimation of Existing Tunnel Structure Induced by Adjacent Shield Tunneling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 146, 105664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Sun, C.; Ao, Y.; Jin, C.; Tao, Q. Stratigraphic Response and Control Measures Induced by Excavation of Shallow Underpass Tunnels. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 170, 109286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Hu, B.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Sharifzadeh, M. Comparative Analysis of Creep Mechanical Characteristics of Yellow Mudstone Tunnel in Natural and Saturated Conditions: Insights from Experiments and Numerical Modeling. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, A. A Dynamic Calculation Method for Safety Step Distance in Mechanized Soft Rock Tunnel Construction Using Multi-Source Data Integration. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 165, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Lu, D.; Lin, Q.; Kong, F.; Du, X. Time-Dependent Surrounding Soil Pressure and Mechanical Response of Tunnel Lining Induced by Surrounding Soil Viscosity. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 2453–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Lu, P.; Diao, Y. Computers and Geotechnics Advance Speed-Based Parametric Study of Greenfield Deformation Induced by EPBM Tunneling in Soft Ground. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 65, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50157-2013; Code for Design of Metro. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- TB10003-2016; Code for Design of Railway Tunnel. China Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB/T51438-2021; Standard for Design of Shield Tunnel Engineering. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Guo, F.; Tan, L.; Wang, Z. Construction Techniques and Mechanical Behavior of Newly-Built Large-Span Tunnel Ultra-Short Distance Up-Crossing the Existing Shield Tunnel with Oblique Angle. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 138, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, K.; Gou, C.; He, C.; Liang, K.; Zhang, H. Failure Tests and Bearing Performance of Prototype Segmental Linings of Shield Tunnel under High Water Pressure. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 92, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Beskos, D.E. Soil—Structure Interaction Effects on Seismic Inelastic Analysis of 3-D Tunnels. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2010, 30, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).