Abstract

Coaxial closed-loop geothermal systems, increasingly recognized as scalable and low-impact geothermal solutions, remain limited by conductive heat transfer between the reservoir and wellbore. This study investigates three strategies to enhance thermal output: (i) dynamic operation scheduling, (ii) substitution of conventional fluids with Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) working fluids, and (iii) targeted conductive enhancements near the well. Using a CMG STARS simulation framework, system performance was evaluated over 1- to 20-year horizons, introducing a characteristic thermal recovery curve as a tool for analyzing long-term behavior. Results show that extended recovery durations raise outlet temperatures but with diminishing returns, identifying approximately 80% recovery as a practical optimization point. Fluids such as n-pentane and R245fa deliver substantially greater ORC-compatible heat than water, with thermo-siphoning observed under low-flow conditions. Conductive enhancement geometries, namely ring and fishbone configurations, exhibit distinct performance profiles, with rings outperforming fishbones due to larger injected volumes and greater advantage due to reservoir reach. One-year gains range from 4.5–9.4% for rings and 0.65–1.37% for fishbones, stabilizing at 3.7–7.8% and 0.55–1.18% after 20 years. These findings provide design and operational guidance for advancing coaxial closed-loop systems in low-carbon energy deployment.

1. Introduction

Meeting the rising demand for low-carbon baseload energy is inseparable from the global challenge of climate change, which requires the development of effective strategies to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. Unlike intermittent sources such as solar and wind, which are weather-dependent, geothermal energy offers a stable supply, though sustainable extraction takes different forms and requires careful management [2]. To this end, closed-loop geothermal systems such as Coaxial Borehole Heat Exchangers (CBHE) are gaining renewed attention. CBHEs are well-established for space heating and other direct use applications with proven economic viability [3]. However, their broader deployment is often constrained by inherently slower conductive heat transfer from the surrounding formation to the wellbore, which limits thermal output. Recent field-scale and numerical studies indicate that deep CBHEs can deliver thermal outputs on the order of several hundred kilowatts, indicating their potential in higher-enthalpy environments [4]. This warrants further investigation into design and operational modifications that can improve long-term performance and extend applicability. This study explores three principal strategies for enhancing heat transfer in CBHEs: (i) intermittent operation cycles, (ii) substitution of conventional geothermal fluids with Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) working fluids, and (iii) thermal enhancement approaches applied around the wellbore and in the surrounding formation. The following section reviews the existing literature on these strategies, providing the context for our simulation-based evaluation and comparative analysis.

1.1. Background and Methodological Rationale

1.1.1. Intermittent Operation and Formation Thermal Recovery

Intermittent operation in coaxial borehole heat exchangers (CBHEs) allows the geothermal reservoir to partially recover its thermal potential during idle periods, thereby enhancing system performance and dispatchability. This operational mode is particularly relevant for energy storage applications, where cyclic demand profiles align with reservoir recovery dynamics. Prior studies have demonstrated that both short- and long-term thermal recovery significantly influence CBHE performance.

Pokhrel et al. [5] developed a numerical model in ANSYS Fluent, validated against field data from a high-temperature CBHE in Beppu, Japan. They introduced a dimensionless temperature recovery ratio, θ, to evaluate thermal recovery at the borehole wall during the idle periods. It is defined as:

where

Twall,init: average wall temperature before heat extraction begins,

Twall,final: average wall temperature at the end of the extraction period,

Twall,rec: average wall temperature after the recovery period.

Naturally, a value of θ = 1 indicates complete thermal recovery to the initial temperature. Using the field-calibrated model, Pokhrel et al. [5] modeled the thermal recovery of the formation and found that a run-recovery ratio of one (456 h of operation followed by 456 h of recovery) yielded 86 percent thermal recovery. Similarly, Zhang et al. [6] combined numerical and field investigations of a 2.5 km deep CBHE in North China, showing that the system nearly re-established thermal equilibrium within a year (120 days of operation followed by recovery during the remainder of the year), supporting the feasibility of sustainable cyclic operation.

Xu et al. [7] modeled continuous and intermittent CBHE operations using a TOUGH-based wellbore-reservoir simulator (T2Well), calibrated against field data from a 2800 m well. Short-term daily cycling (8 h on, 16 h off) improved average heat extraction rates compared to continuous operation, though complete recovery was not achieved. Long-term annual cycling (120 days of operation followed by 245 days of recovery) allowed near-complete thermal recovery but still exhibited gradual performance decline over decades. Huang et al. [8] and Jia et al. [9] further confirmed that shorter daily run times enhance output temperatures but reduce total extracted heat, highlighting tradeoffs between instantaneous performance and cumulative energy yield.

Overall, cyclic operation in CBHE systems offers a pathway to balance short-term heat extraction rates with long-term thermal sustainability. Longer recovery cycles better support near-complete thermal recovery and operational longevity, though practical schedules are often dictated by end-user demand. It seems that thermal degradation is expected and accepted in the operation of CBHE systems. In borehole fields with adequate spacing, staggered cycling may enable continuous output while allowing individual wells to recover. Building on these insights, this study establishes a baseline for high-enthalpy CBHEs and systematically compares continuous and cyclic operations across varying run-recovery ratios while also examining the influence of formation properties, flow rate, and operational scheduling.

1.1.2. Alternative Working Fluid Selection

Beyond operational scheduling, working fluid selection strongly influences CBHE performance. Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) fluids, already widely used in binary geothermal plants, are promising alternatives to water, particularly for power generation applications. Prior studies have modeled CBHEs with n-pentane [10] and iso-butane [11], and certain other organic working fluids such as R245fa [6] for lower-temperature applications (below 40 °C). Major geothermal operators utilize pentane and other similar aliphatic paraffins as ORC working fluids. Directly heating ORC fluids within the wellbore eliminates the surface heat exchanger, reducing thermal losses and improving overall cycle efficiency.

However, fluid selection introduces tradeoffs. n-pentane, while thermodynamically favorable, is highly flammable, raising safety, regulatory, and cost concerns. R245fa. a working fluid with no ozone-depleting properties, possesses high global warming potential (GWP). Alternative fluids with similar thermophysical properties but lower GWP have been identified [12]. Insights from R245fa modeling may extend to these more sustainable substitutes, but further investigation is warranted.

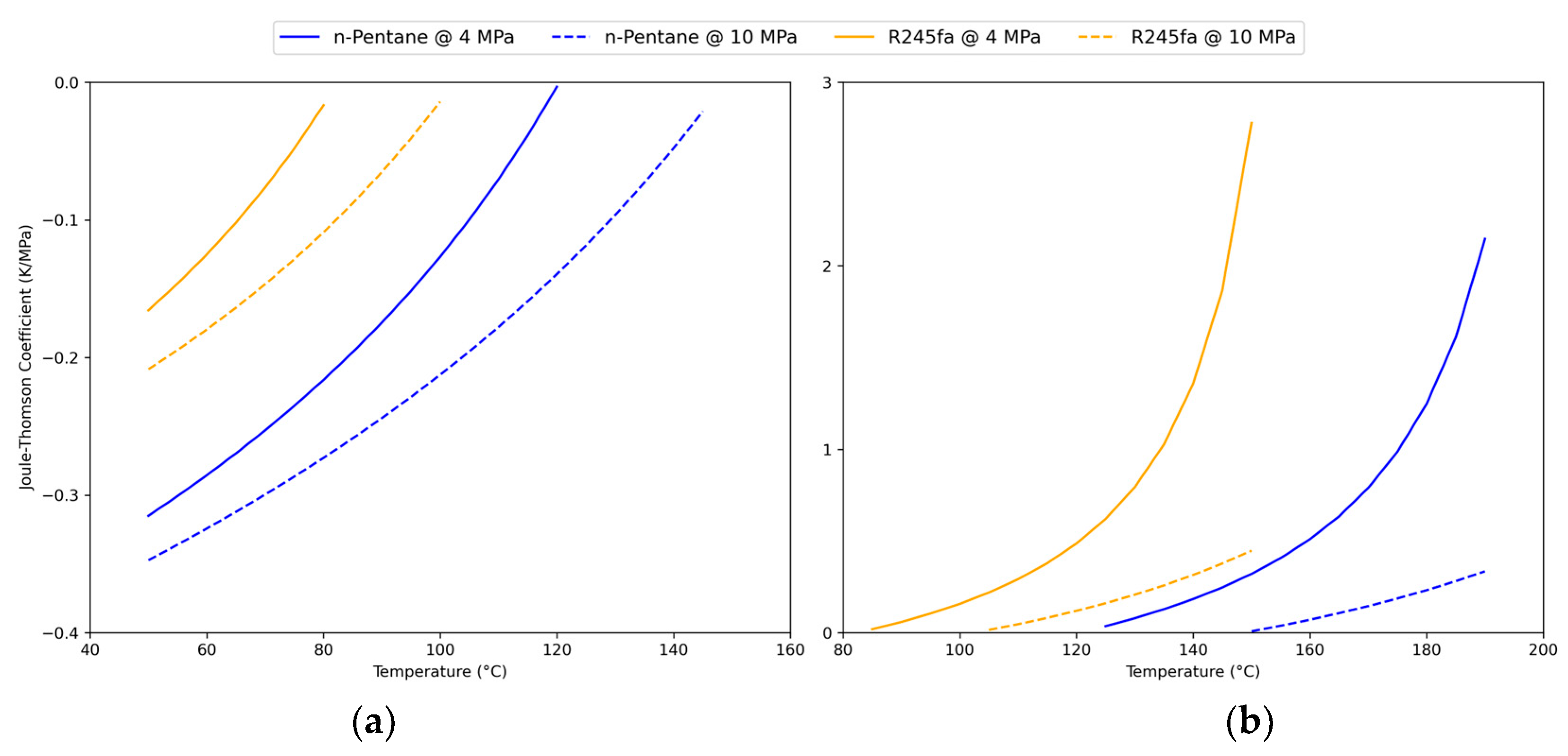

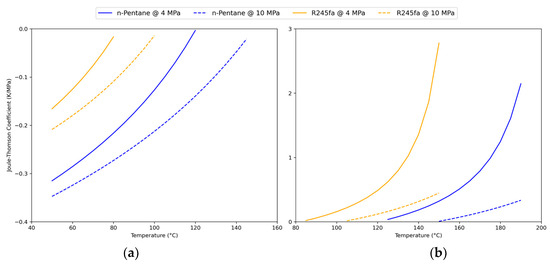

Thermodynamic properties of the three fluids under study (water, n-pentane, and R245fa) can be found in Table 1. While the acentric factor captures how much a fluid deviates from spherical molecular behavior, the dipole moment quantifies polarity and directly relates to intermolecular forces. Thus, n-pentane’s lower acentric factor and negligible polarity reflect simple hydrocarbon behavior, whereas R245fa’s higher acentric factor and significant dipole moment indicate both molecular non-sphericity and stronger polar interactions. Both organic fluids are more compressible than water, making Joule–Thomson (JT) cooling effects significant under depressurization, as shown in Figure 1. As illustrated, the JT values become positive above 80–100 °C, indicating that depressurization could induce cooling, a behavior that must be accounted for in the modeling approach.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic properties of the selected working fluids.

Figure 1.

(a) negative and (b) positive JT values for n-pentane and R245fa, data from [13].

In this study, we model the circulation of water, n-pentane, and R245fa in a high-enthalpy CBHE system. We focus on output temperatures suitable for sub-critical ORC integration and evaluate both thermal performance and hydraulic parasitic losses, providing insights into the tradeoffs of fluid selection for next-generation geothermal applications.

1.1.3. Enhanced Heat Transfer Through Wellbore and Formation Modifications

A third avenue for improving CBHE performance involves enhancing conductive heat transfer between the wellbore and the surrounding formation. While internal wellbore modifications such as baffles or turbulators can improve convective heat transfer [14], the primary bottleneck lies in conduction through the cement, casing, and formation. Strategies therefore focus on reducing thermal resistance at the wellbore-formation interface and increasing effective heat conduction pathways within the reservoir.

One promising approach involves injecting high thermal conductivity fillers such as graphite slurry near the wellbore. Renaud et al. [15] investigated this concept using TOUGH-based T2Well simulations, drawing on patents by Hara [16] proposing the use of graphite instead of cement between casing and formation, and Buchi [17], which focused on a radially distributed chamber filled with enhancer at the bottomhole depth. Graphite injection along the vertical wellbore yielded long-term performance improvements of 5.4–8.4%. However, as shown by Khaleghi et al. [18] and Liu and Dahi [19], increasing cement conductivity beyond that of the formation provides only diminishing returns, suggesting practical limits to such enhancements.

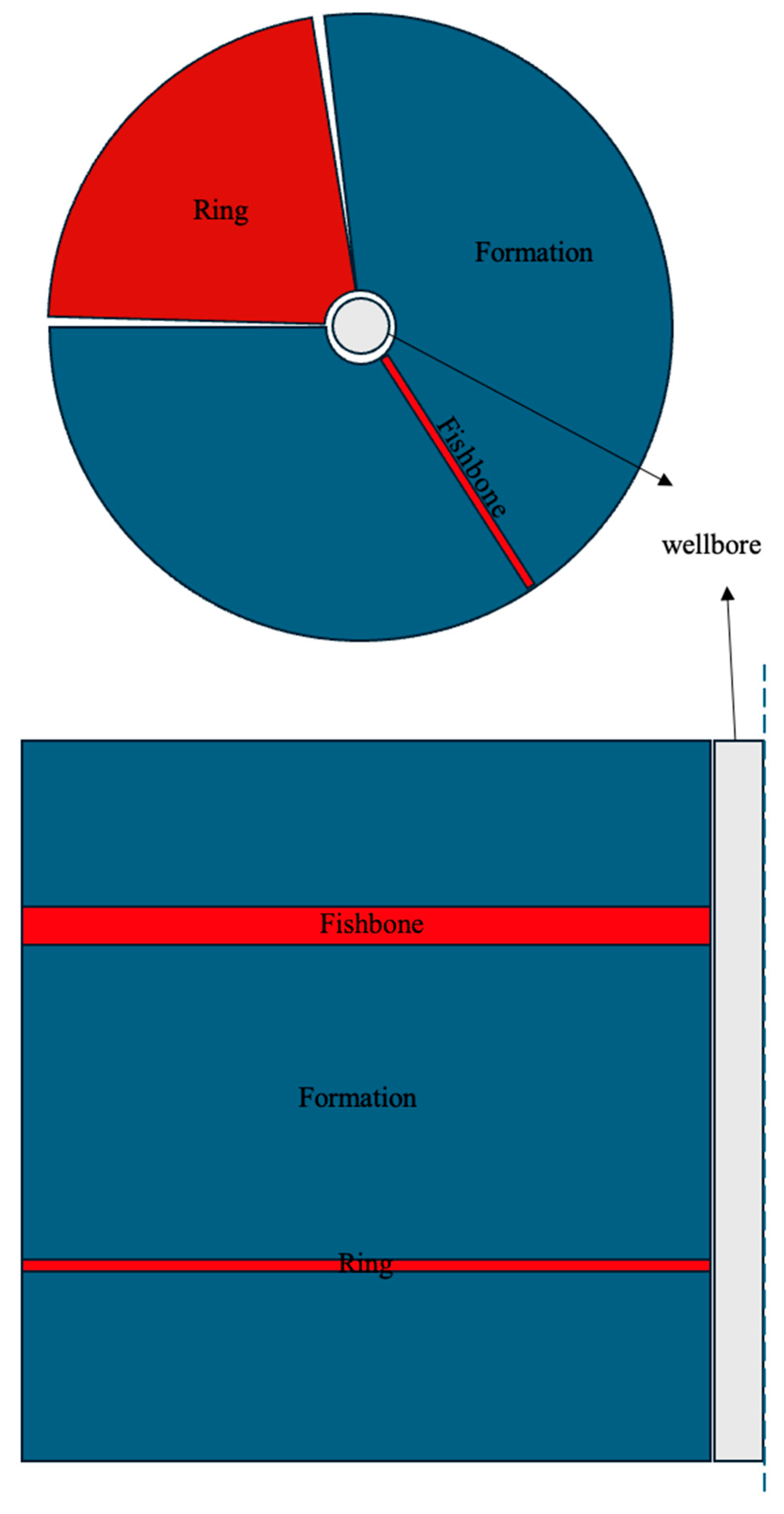

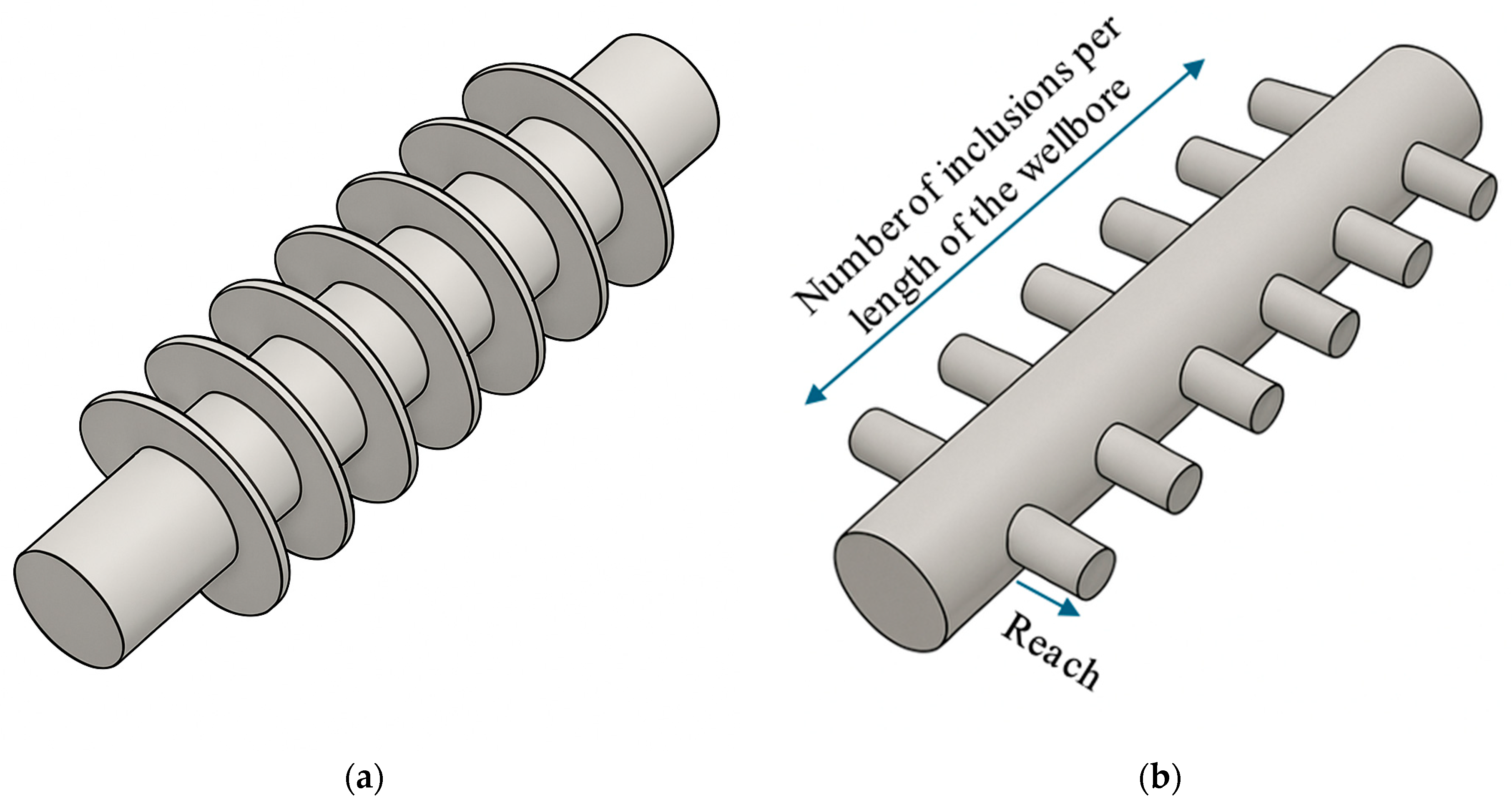

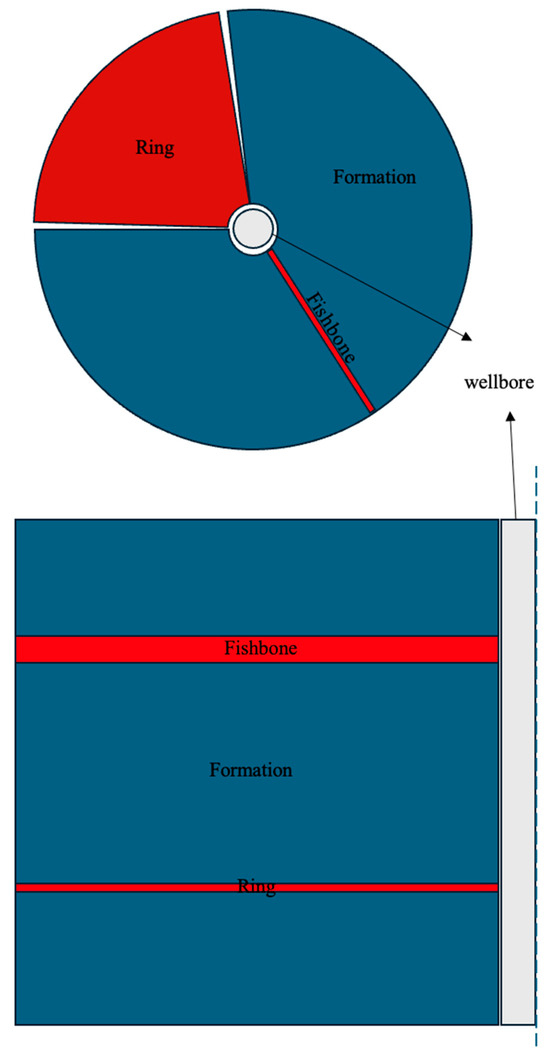

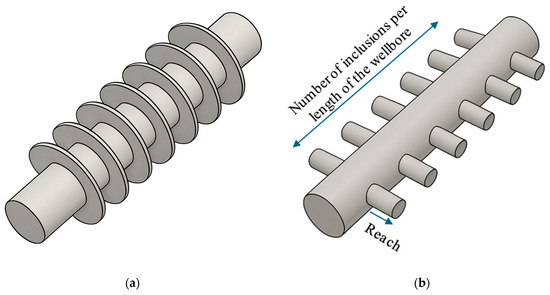

Two geometries of interest for conductive inclusions are ring-shaped and fishbone-like structures; for more information on the latter, see [20]. Ring structures, potentially created via hydraulic stimulation, extend radially from the wellbore, while fishbones, often associated with acid stimulation, extend laterally (Figure 2). Beckers et al. [21] modeled these geometries using COMSOL, showing that thermal output increases linearly with the number of thermal enhancements. Assuming the enhancer material possesses a conductivity 1000 times that of the rock, rings provided modest thermal gains (0.7% for five discs in a 1000 m wellbore), while fishbones (10 m long with the 4 equally spaced enhancements along a 10 m lateral) achieved up to 20% improvement in the thermal power under favorable configurations.

Figure 2.

Top and side views of ring-shaped and fishbone-like structures embedded inside the formation.

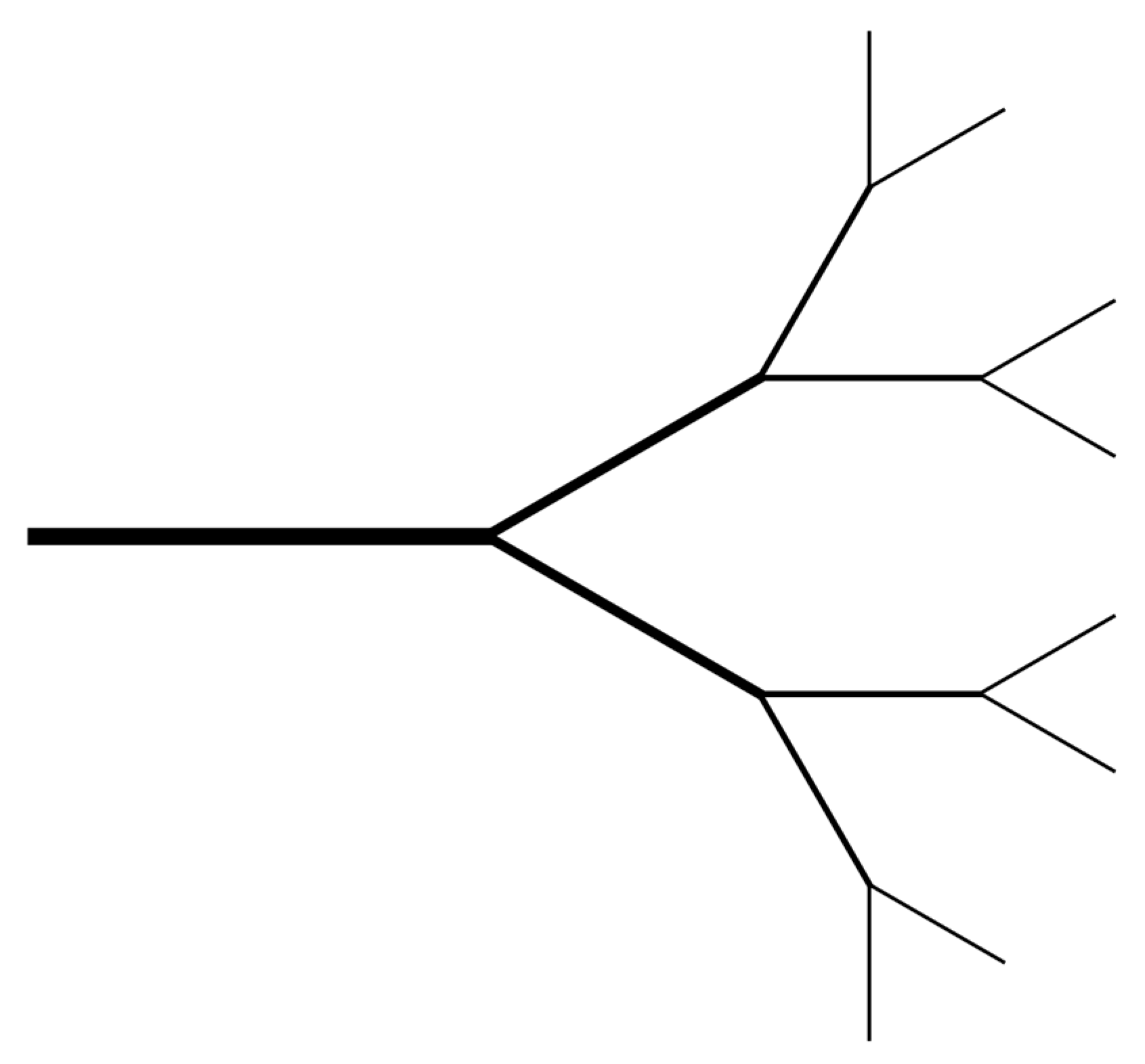

To include the effective thermal conductivity (ETC) of formations augmented with conductive features into reservoir simulators, effective medium theory (EMT) and thermal resistance models provide tractable approximations. Xu et al. [22] developed EMT formulation for tree-like branched conductive structures (see Figure 3). The tree/network is parametrized using the branching number, the total number of branching levels, and the length ratio. Simplified thermal resistance frameworks allow incorporation of thin ring-like inclusions without excessive mesh refinement. In this study, we adopt a control volume (CV) approach for rings to calculate the equivalent thermal resistance and a volume-weighted EMT for fishbones, enabling incorporation of localized enhancements into reservoir-scale models.

Figure 3.

A branched network structure with bifurcating and thinning branches was reproduced from [22].

Accordingly, our objectives are to (i) compare the relative effectiveness of ring and fishbone strategies, and (ii) identify key performance indicators (KPIs) linking enhanced conductivity to thermal output. Together, these analyses provide a framework for evaluating the field potential of conductive modifications in CBHE systems.

While prior studies have advanced analytical, semi-analytical, and numerical models for CBHE performance forecasting, there remains a need for fully coupled simulations that capture both wellbore heat transport and transient formation behavior under realistic operational cycling. In this work, we develop a comprehensive modeling framework in a commercial thermal reservoir simulator capable of resolving heat transfer between the wellbore fluid, insulated tubing, annulus, cement, casing, and surrounding formation, in addition to capturing the hydraulic behavior of the circulating fluid. The model is supported by validation against field data, providing confidence in its predictive capability. Building on this foundation, we investigate operational cycling using a θ-based recovery criterion and examine the resulting recovery-runtime behavior, highlighting characteristic thermal response trends not previously documented. We then compare three potential working fluids, water, n-pentane, and R245fa, under identical geometric and geological conditions to evaluate their suitability for sub-critical ORC integration. Finally, we incorporate a design strategy based on high-conductivity filler materials and introduce an upscaling approach that enables these enhanced-conductivity architectures to be represented consistently within reservoir simulators. Next, we describe the modeling approach developed to achieve these objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

A coaxial borehole heat exchanger model was developed in CMG STARS (Version 2024.20) using a Cartesian reservoir grid with local refinement near the wellbore to improve early-time resolution. The wellbore was represented with the Flexwell tool, a mechanistic, discretized model that accounts for heat transfer and hydraulic losses in both annulus and internal tube [23]. Flexwell operates on a grid independent of the reservoir, with sequential coupling such that the reservoir is updated one iteration after the wellbore.

To validate the workflow, a model was constructed to replicate the dimensions and operating parameters of the HGP-A coaxial pilot in Hawaii [24]. Casing and cement thermal properties were matched to field data, and the geothermal gradient profile in the reservoir was recreated. Formation conductivity and heat capacity, not directly measured in the original work, were estimated to be 1.6 W/m·K and 870–1026 J/kg·°C based on model fitting [25]. Using the reported porosity of 13% and grain thermal conductivity of 3.0 W/m·K for Hawaii basalt [26], an effective conductivity of 2.7 W/m·K was calculated using the following:

where is porosity and , and are effective thermal conductivity of the medium, thermal conductivity of formation water and grain respectively.

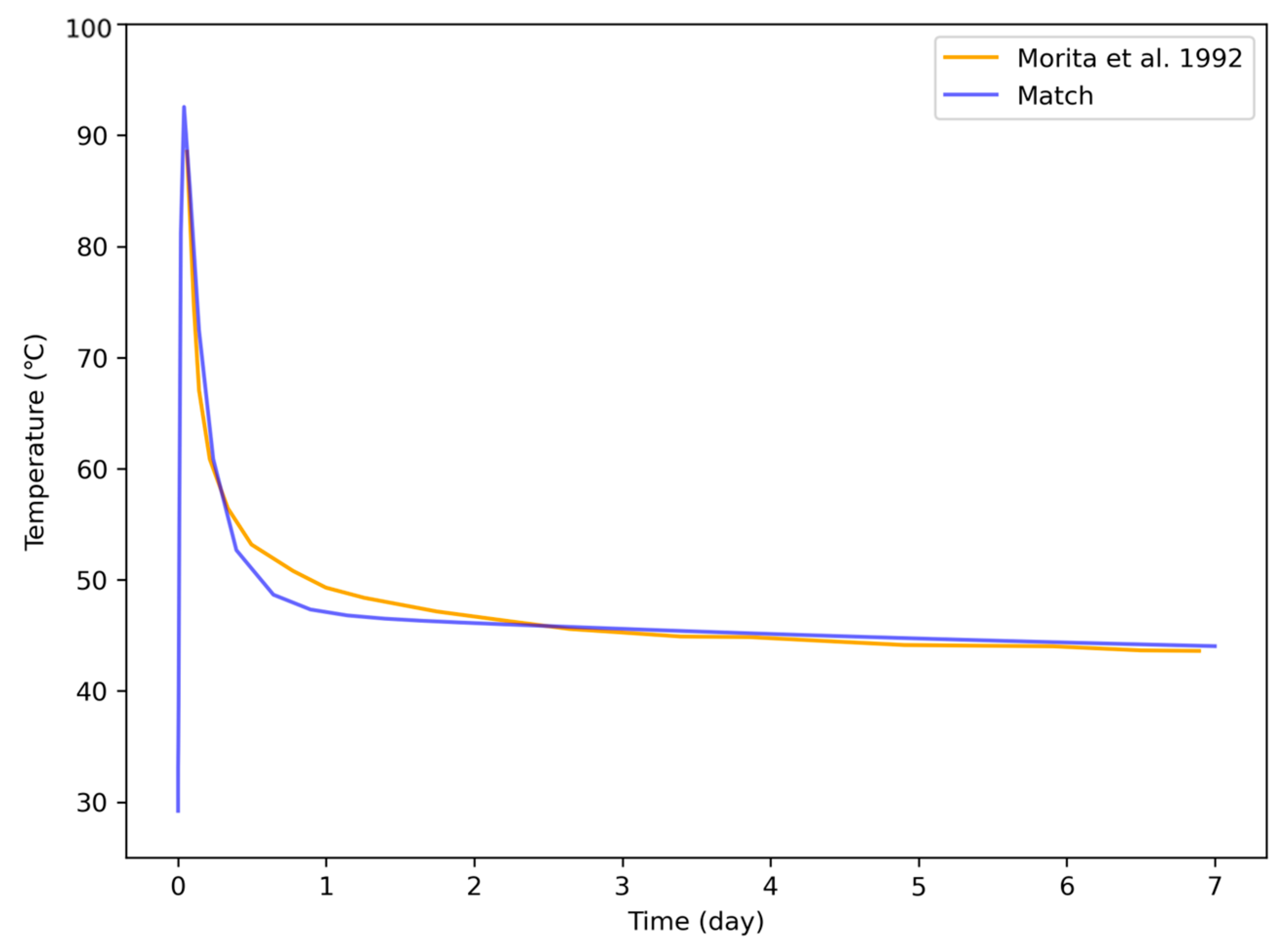

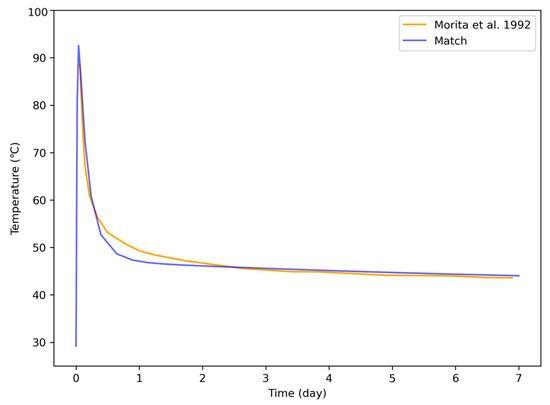

Heat capacity was adjusted to 652 J/kg·°C, consistent with basalt values to improve calibration [27]. Figure 4 compares the seven-day pilot data with results of our calibrated model, showing close agreement. The calibration against the field dataset yielded an RMSE of 2.03 °C and a mean absolute error of 1.42 °C across the full transient period.

Figure 4.

Model temperature output versus the field data reported by [24].

Building on this validation, a base case model of vertical CBHE with 4 km depth and a linear geothermal gradient yielding a bottomhole temperature of 225 °C was developed. Table 2 summarizes the dimensions and thermal properties of system components. Thermodynamic properties of water were obtained from internal steam tables, while for n-pentane and R245fa, density correlations were derived from liquid compressibility and thermal expansion coefficients. The Lee–Kesler method [28] was employed to calculate thermodynamic properties, ensuring accurate representation of Joule–Thomson effects. Liquid viscosity correlations with temperature are based on the NIST chemistry webbook data [13].

Table 2.

Wellbore dimensions and formation, and wellbore thermal properties.

To incorporate conductive enhancements into the reservoir model, effective medium theory (EMT) and thermal resistance formulations were applied. Under steady-state assumptions, resistance to heat flow was expressed in terms of thermal conductivity, thickness of material, and cross-sectional area [29]. In cylindrical coordinates, the resistance per unit length of the wellbore takes the following form:

where

Rj is the conductive resistance of the element “j”.

ri and ro are the inner and outer radii of the element.

kj is the thermal conductivity of the element “j”.

Two enhancement strategies were evaluated: a graphite-filled ring surrounding the borehole, and a high-conductivity fishbone structure representing laterally embedded inclusions. For the ring case, a control volume approach was adopted in which the outer boundary coincided with the outer ring radius, reducing the system to two stacked disks. Radial heat flow occurred through two parallel pathways, and the equivalent thermal resistance was given by:

where

Req is the equivalent conductive resistance of the CV containing the ring and the formation.

Rring is conductive resistance through the graphite-filled ring.

Rformation is conductive resistance through the adjacent formation.

This parallel formulation defines an effective thermal resistance for the composite block and can be easily generalized to a system containing multiple rings. This formulation, suitable for thin fracture-like layers (0.1–10 mm), avoids excessive mesh refinement while capturing localized effects, and the resulting effective conductivity was incorporated directly into the simulator.

For the fishbone structure, a volume-weighted EMT was applied, equivalent to the Voigt upper bound [30], assuming a uniform temperature gradient across the block.

where is the graphite volume fraction, and , and are effective thermal conductivity of the medium, thermal conductivity of the graphite and formation respectively.

This approach is suitable for millimeter- to centimeter-scale conductive inclusions aligned with heat flow. Unlike the ring, the fishbone volume does not scale with annular control volume; hence, the local volume fraction () diminishes with distance from the wellbore, requiring updates to at each radius.

For the enhancement section, a graphite conductivity of 500 W/m·K was assumed [31] with a symmetrical arrangement of rings and fishbones per unit length around the bottom 400 m of the wellbore to preserve model assumptions. This framework enables tractable upscaling of conductive modifications into reservoir-scale simulations while maintaining computational efficiency.

To summarize, the overall workflow of this study proceeds in three stages: (i) simulation setup in CMG STARS, including reservoir geometry, wellbore representation, and property initialization; (ii) validation against the HGP-A pilot dataset to ensure model fidelity; and (iii) performance analysis through three enhancement strategies, operational scheduling, working fluid substitution, and conductive modifications. This structured workflow provides a clear basis for comparing design and operational strategies.

3. Results

The results of this study are presented in three parts, corresponding to the enhancement strategies introduced earlier: (i) operational scheduling through intermittent cycles, (ii) substitution of conventional water with alternative working fluids, and (iii) conductive enhancements in the formation surrounding the wellbore. Each set of simulations was designed to isolate the influence of key parameters while maintaining consistent boundary conditions across cases. The findings are reported in terms of outlet temperature evolution, thermal output rate, and long-term performance trends. These results provide a systematic comparison of operational, fluid, and structural strategies for improving the performance of high-enthalpy coaxial borehole heat exchangers.

3.1. Intermittent Operation and Characteristic Recovery Curve

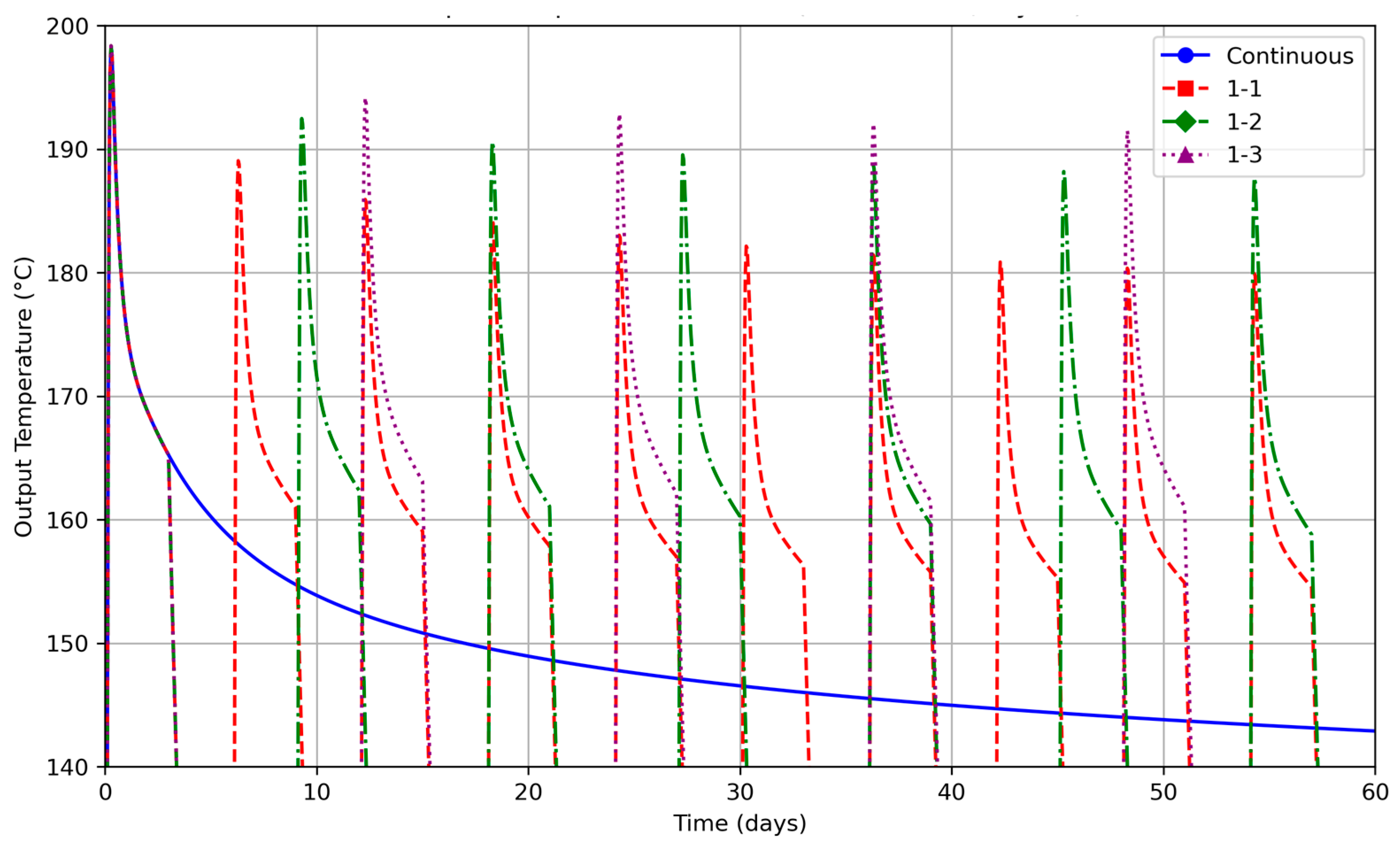

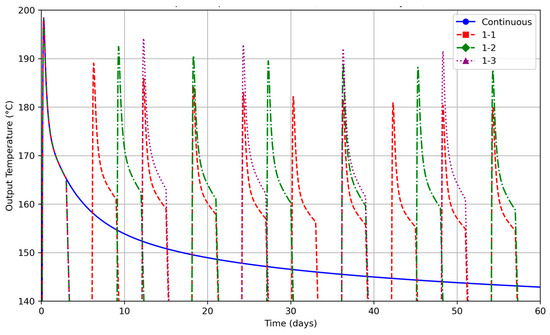

As highlighted in the literature review, studies of intermittency for high enthalpy CBHEs remain limited. Our simulations confirm that the general trends observed in low-enthalpy systems also apply at higher enthalpy levels: longer recovery periods yield higher outlet temperatures during subsequent run cycles. Figure 5 illustrates this behavior by comparing continuous operation with three different run-recovery ratios (1-1, 1-2, and 1-3) for a run duration of three days per cycle.

Figure 5.

Outlet temperature versus time for the base-case CBHE under continuous operation and three intermittent schedules: 1-1 (3-day run, 3-day recovery), 1-2 (3-day run, 6-day recovery), and 1-3 (3-day run, 9-day recovery). Simulations assume a 4 km well depth, bottomhole temperature of 225 °C, formation conductivity of 2.5 W/(m·K), and flow rate of 100 m3/day.

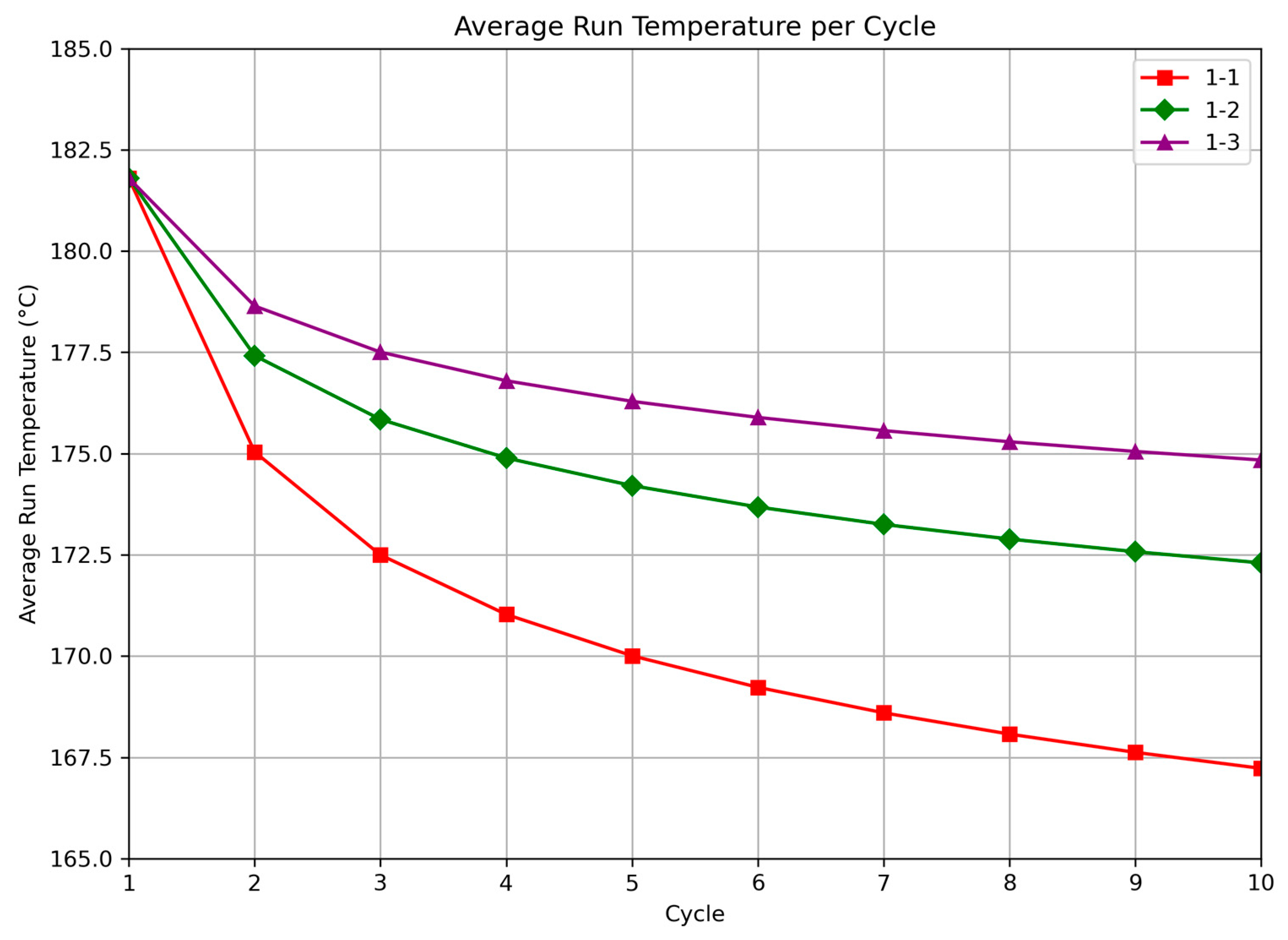

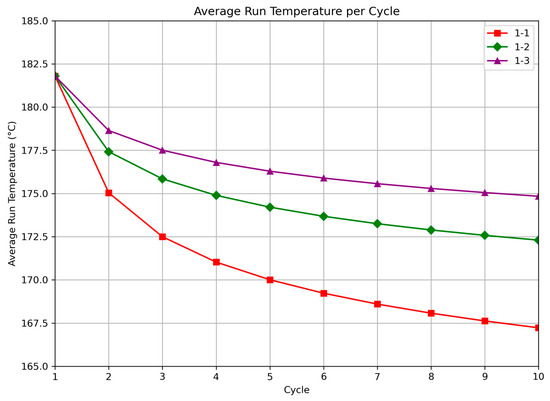

To further characterize cyclic performance, Figure 6 presents the average outlet temperature for the three run-recovery ratios. The spacing between curves is nonlinear, indicating diminishing gains as recovery time is extended. The average temperature profiles also mirror the qualitative behavior of continuous operation, with decline rates slowing over time.

Figure 6.

Average run temperature per cycle for three intermittent schedules: 1-1 (3-day run, 3-day recovery), 1-2 (3-day run, 6-day recovery), and 1-3 (3-day run, 9-day recovery).

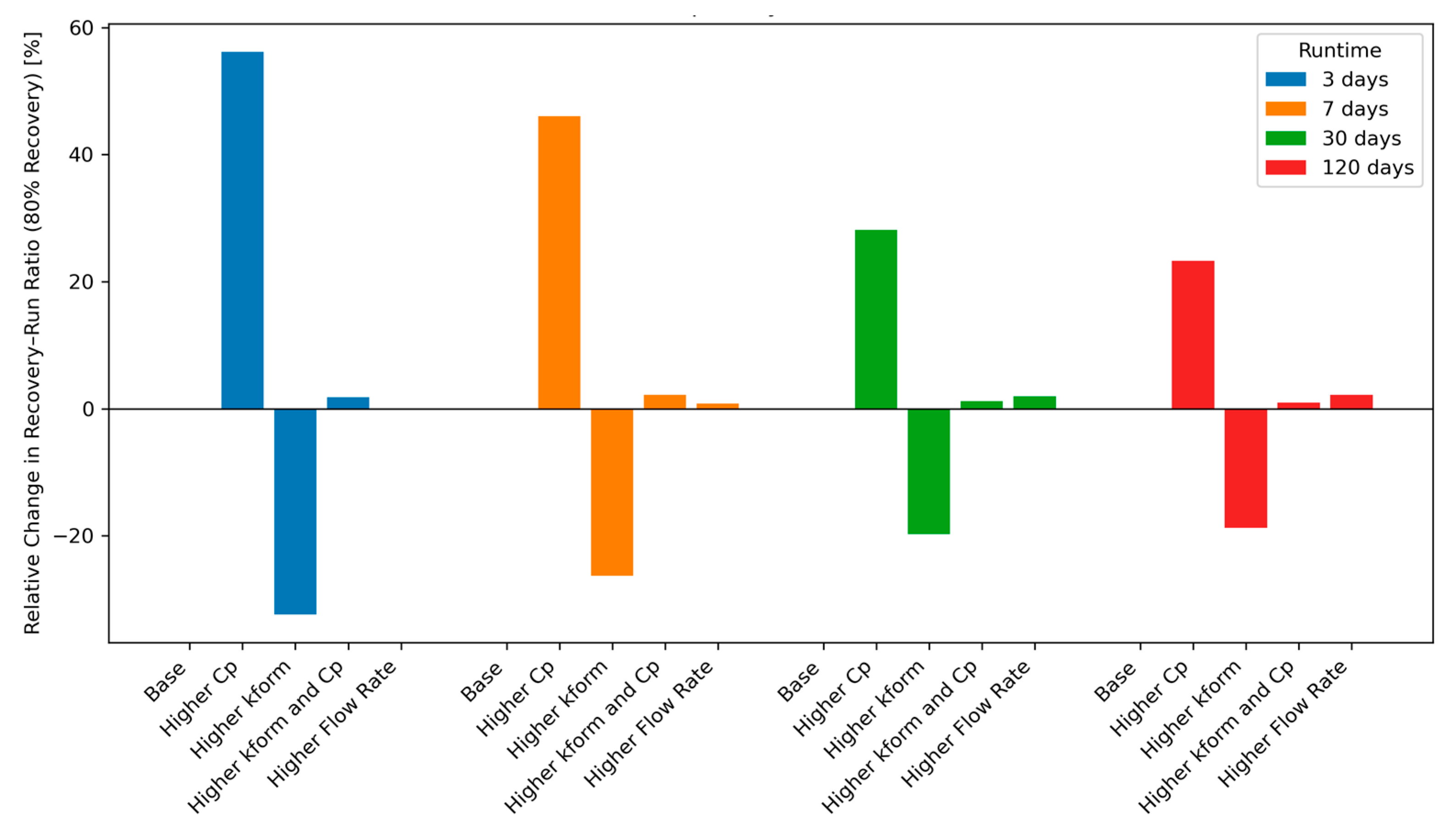

To investigate the influence of reservoir and operation parameters on thermal recovery, a set of simulations was performed by varying formation thermal properties (thermal conductivity and heat capacity), injection flow rate (two levels each), and the number of operational days (3, 7, 30, and 120 days), resulting in a total of twenty simulations. For each runtime, five cases were evaluated: (a) base formation properties (thermal conductivity of 2.5 W/m·K and heat capacity of 600 J/kg·K) with a base flow rate of 100 m3/day, (b) higher heat capacity (1200 J/kg·K), (c) higher thermal conductivity (4.0 W/m·K), (d) combined higher heat capacity and conductivity, and (e) base formation properties with higher flow rate (200 m3/day). The thermal response of the formation adjacent to the bottomhole was monitored during the recovery phase following a single run period.

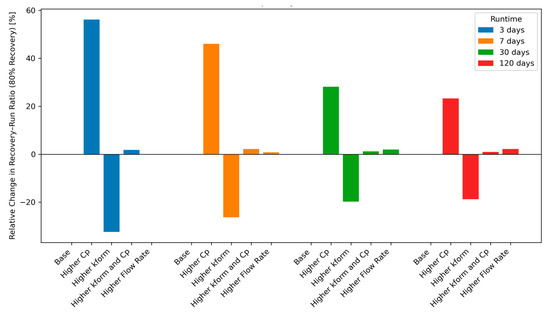

Figure 7 illustrates how the recovery–runtime ratio responds to variations in thermal and operational parameters for four cycle lengths (3, 7, 30, and 120 days). The recovery–runtime ratio is defined as the time required for the bottomhole formation temperature to recover to 80% of its pre-production value (θ = 0.8), divided by the preceding operational runtime. Thus, values greater than the base case (positive deviations) indicate slower recovery relative to runtime, whereas negative deviations indicate faster recovery. The results in Figure 7 show that higher formation thermal conductivity accelerates recovery across all cycle lengths, consistent with the enhanced conductive heat transport and in agreement with [32]. Higher heat capacity slows recovery, as more energy is stored before temperature changes occur. When both parameters are increased, the effects counteract, reflecting the governing role of thermal diffusivity. The influence of flow rate (red bars) is comparatively minor at short runtimes but becomes more visible for the 30- and 120-day cycles, where longer extraction periods amplify small operational differences. Extreme flow regimes remain to be investigated.

Figure 7.

Effect of thermal and operational parameters on recovery-runtime ratio, for θ = 0.8.

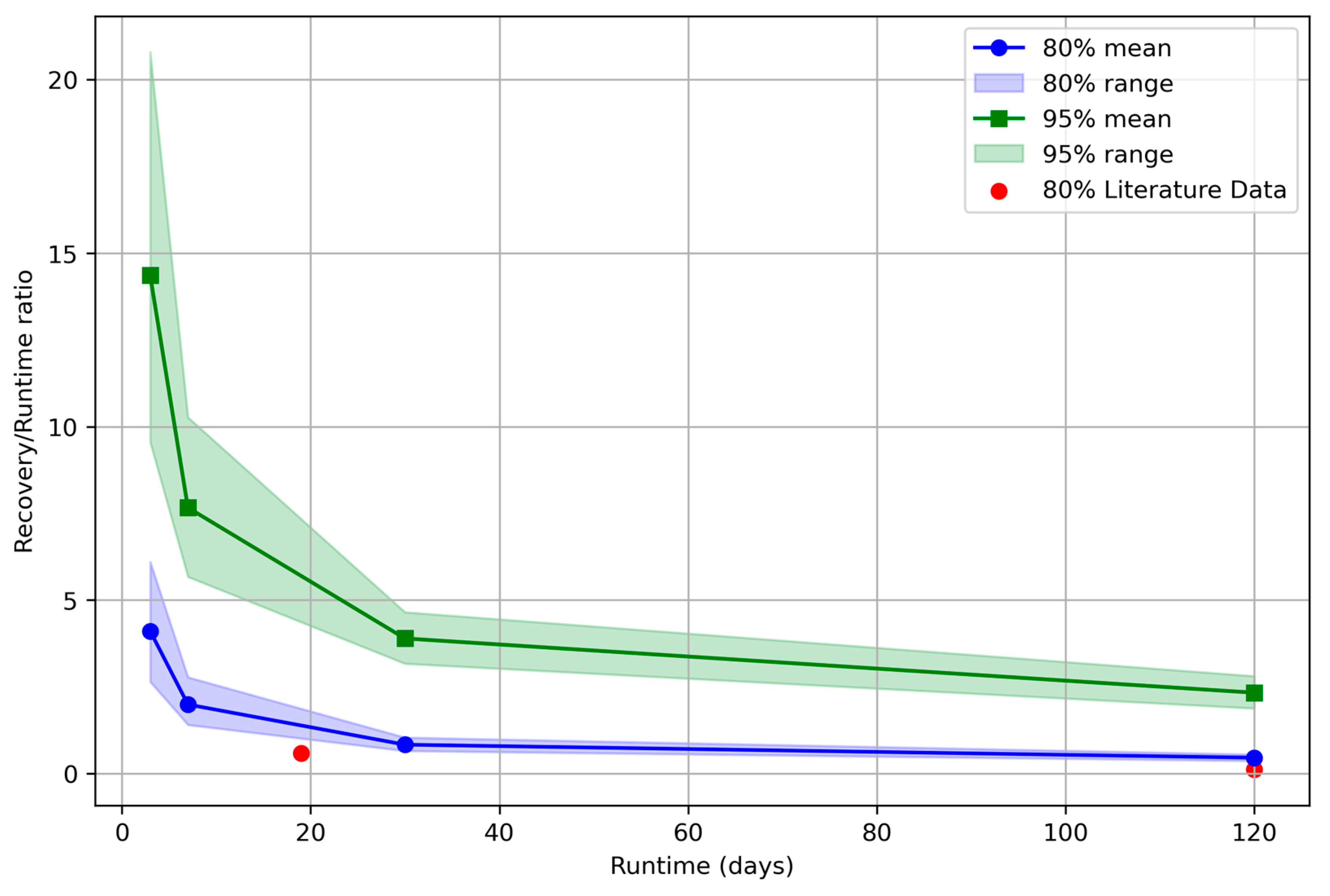

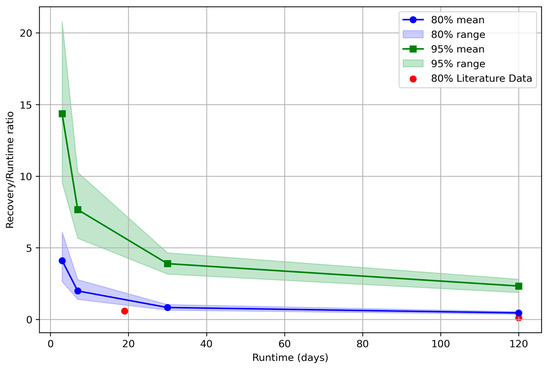

The recovery to run ratio was further analyzed for 80% recovery, yielding a characteristic curve (Figure 8) that correlates recovery/run ratio with run duration. Several insights can be stated:

Figure 8.

Characteristic recovery curve for CBHE operation. Mean recovery-to-run ratio required to reach 80% (blue) and 95% (green) recovery versus run time (3, 7, 30, 120 days). Shaded bands show the range across sensitivity cases in conductivity, heat capacity, and flow rate. Red circles are 80% recovery points from the literature.

- The characteristic curve provides a practical tool for mapping recovery behavior under varying formation thermal properties, run-recovery ratios, and flow rates;

- Achieving 95% recovery requires excessive recovery times, particularly for short cycles, indicating that some degree of thermal degradation needs to be accepted in system design;

- The 80% recovery benchmarks (red circles in Figure 8) reported by Pokhrel et al. [5] and Xu et al. [7], covering different enthalpy environments and well depths, align closely with our results, suggesting that the characteristic recovery curve may have broad applicability;

- Beyond 30 days of runtime, the decrease in recovery/run ratio to achieve 80% recovery slows, indicating a potential “sweet spot” for designing operational schedules.

3.2. Working Fluids: Synergy Between the Surface and the Subsurface

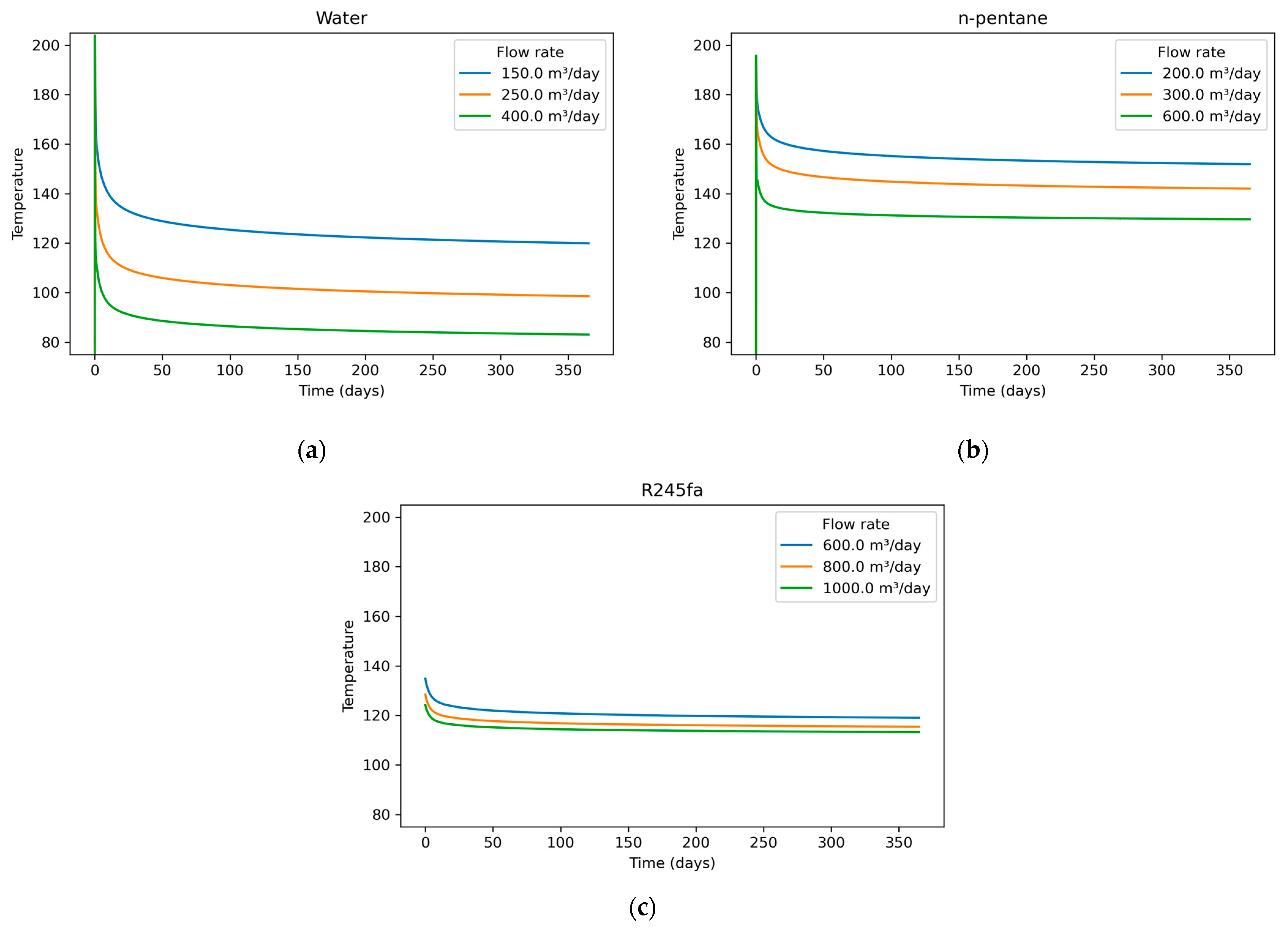

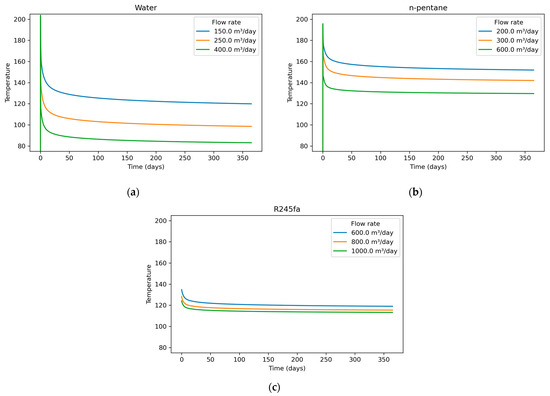

Three working fluids, water, n-pentane, and R245fa, were investigated as candidates for sub-critical Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) applications. For water and n-pentane, wellbore initialization was performed by equilibrating the fluid with the surrounding formation to establish a realistic thermal distribution prior to flow. However, for R245fa, equilibration caused convergence challenges in the numerical model and was therefore omitted. Instead, several initial wellbore temperatures were prescribed to test model sensitivity. Despite these differences, all R245fa cases converged after the first 24 h of simulation, and outlet temperature histories collapsed into a single trajectory for each flow rate. Accordingly, the first 24 h of R245fa results are not reported. For each fluid, three volumetric flow rates were examined, with the corresponding temperature-time responses shown in Figure 9a–c. For water (Figure 9a), flow rate strongly influences the outlet temperature: lower flow rates maintain higher temperatures due to longer residence time, while higher flow rates cool more rapidly. In contrast, n-pentane (Figure 9b) exhibits similar early-time behavior but stabilizes at higher long-term outlet temperatures than water. Although the flow-rate cases for pentane are not directly comparable to those of water, the trend still shows a weaker sensitivity to flow rate relative to water. Finally, R245fa (Figure 9c) shows the weakest dependence on flow rate. The outlet-temperature curves collapse into a narrow band, indicating that the long-term thermal behavior of R245fa is governed primarily by its thermophysical properties, rather than by operational changes in the investigated flow rate range.

Figure 9.

Outlet temperature versus time for three fluids under three volumetric flow rates each: (a) water, (b) n-pentane, (c) R245fa. For R245fa, initialization by equilibration was omitted due to convergence challenges; the first 24 h are excluded.

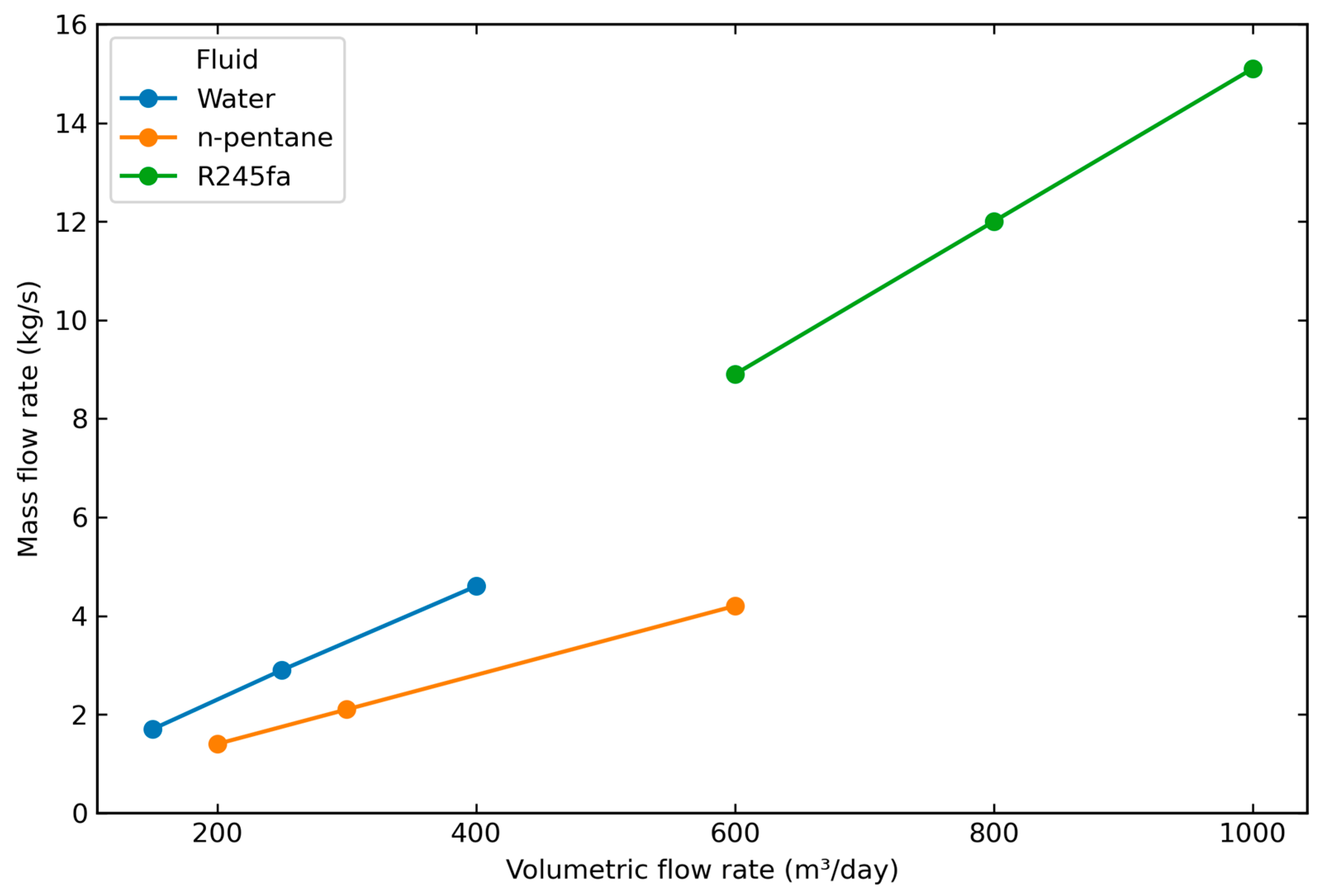

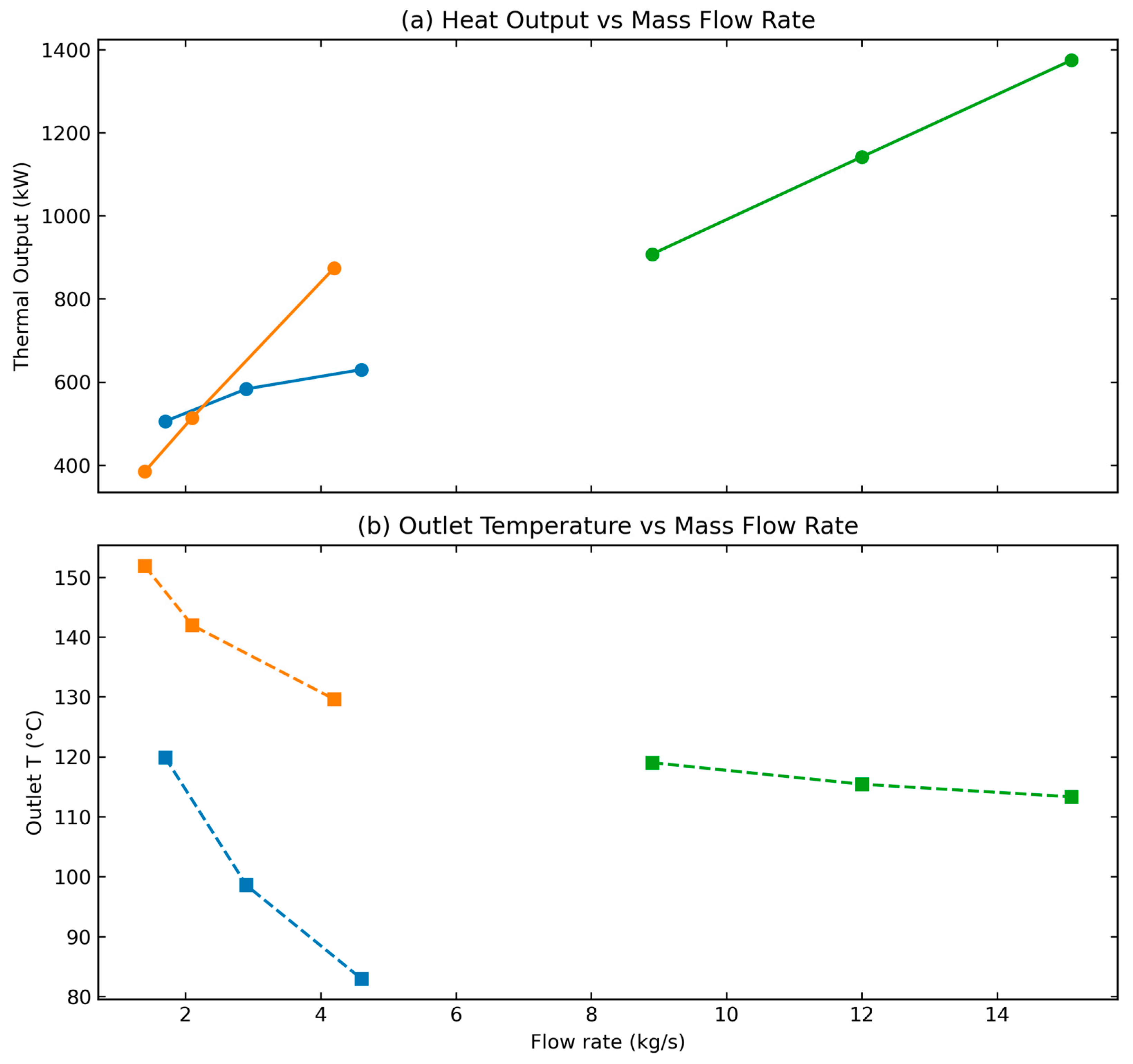

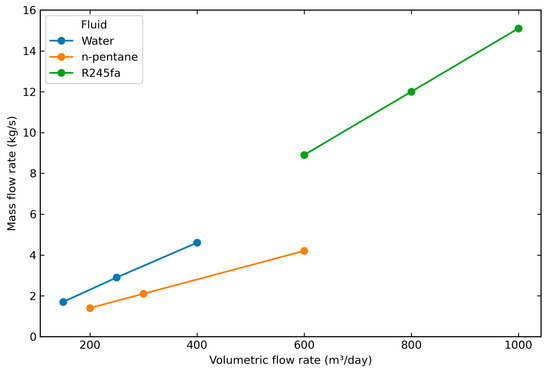

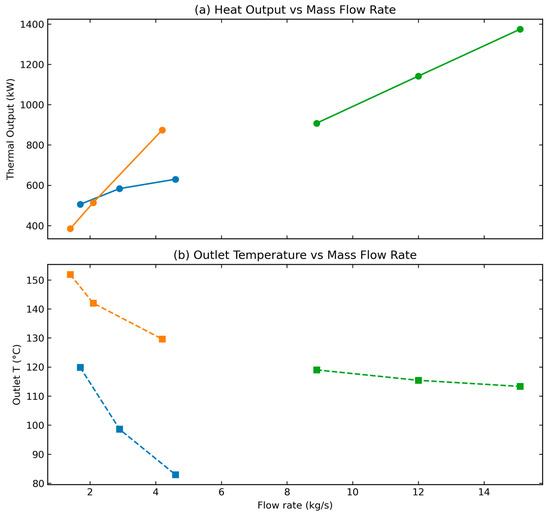

To account for density effects, Figure 10 presents the relationship between volumetric and mass flow rates, enabling comparison of the three fluids on a consistent mass basis. Flow rates were chosen to maintain outlet temperatures within the sub-critical ORC range while avoiding near-critical conditions for n-pentane and R245fa, ensuring reliable property calculations for density, enthalpy, and viscosity. Under these conditions, both the alkane and the refrigerant delivered higher thermal outputs than water (Figure 11). In addition, they offer the advantage of direct integration into an ORC without the need for a surface heat exchanger.

Figure 10.

Mass flow rate (kg/s) versus volumetric flow rate (m3/day) for the working fluids.

Figure 11.

(a) Thermal output in kW (b) and output temperature in °C, at the end of year one of operation for the three working fluids.

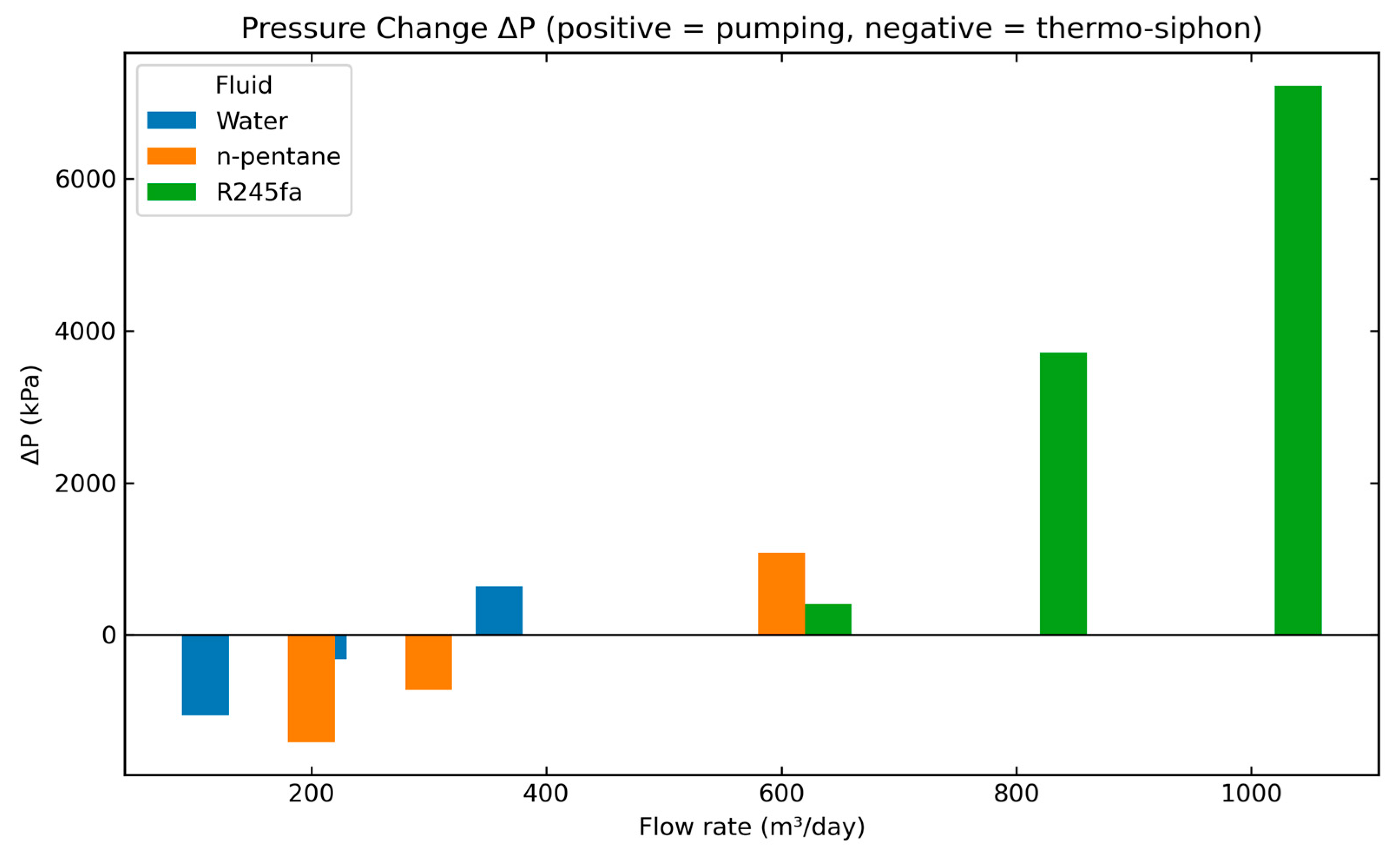

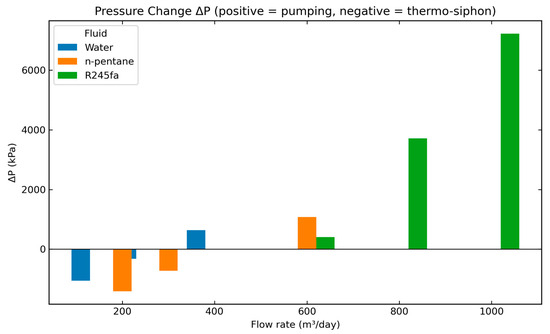

Figure 12 illustrates the pressure differences between inlet and outlet flows. At lower flow rates, water and n-pentane showed thermo-siphoning, promoting natural circulation and eliminating pumping requirements. At higher flow rates, pressure drops increased and pumping demands rose sharply, especially for R245fa. These results highlight the trade-off between thermal output and parasitic losses. Identifying an optimal operating window requires balancing heat delivery, outlet temperature requirements, and pumping costs to ensure efficient ORC power generation.

Figure 12.

Pressure drops across volumetric flow rates for the three working fluids at the end of year one.

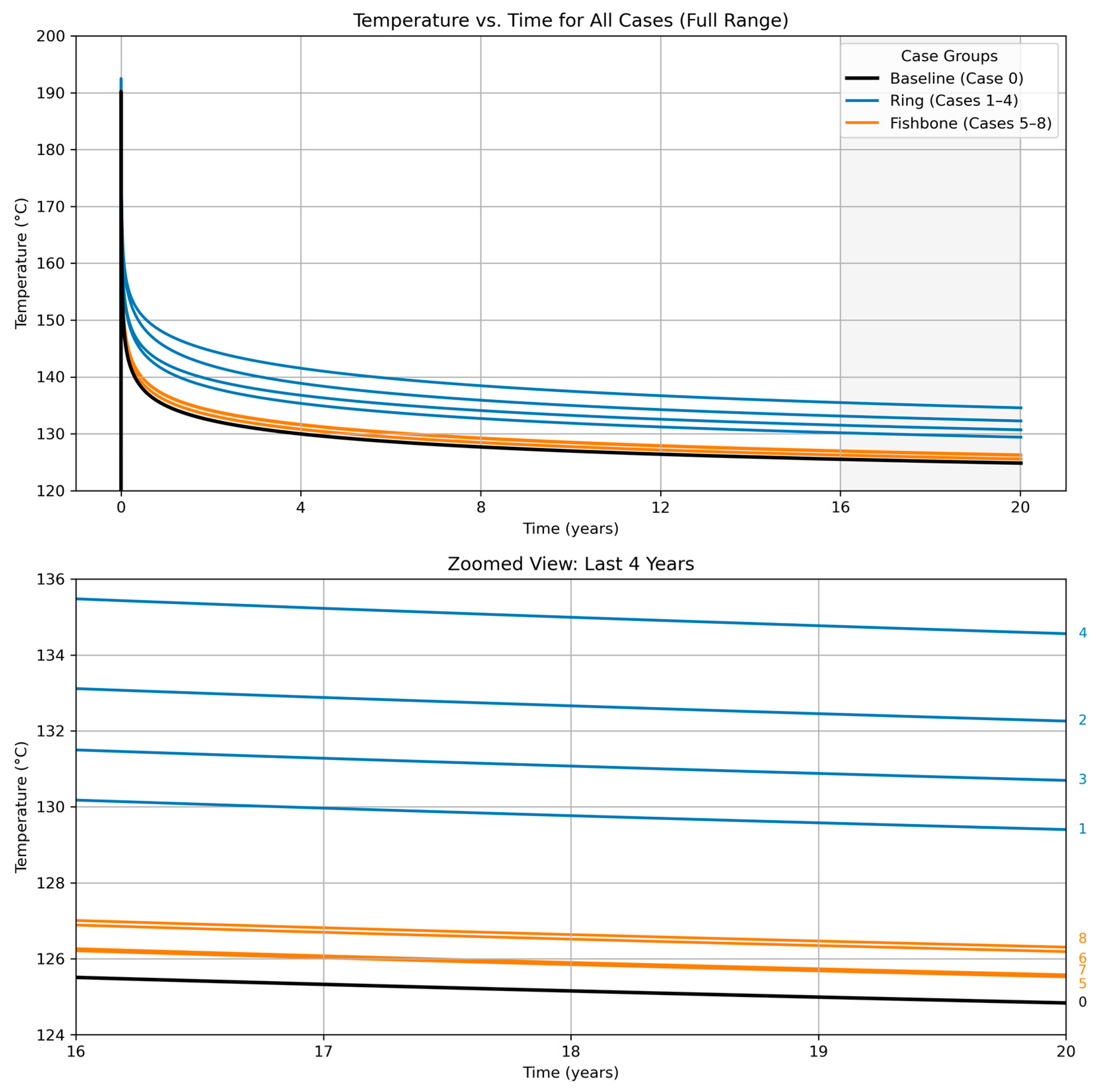

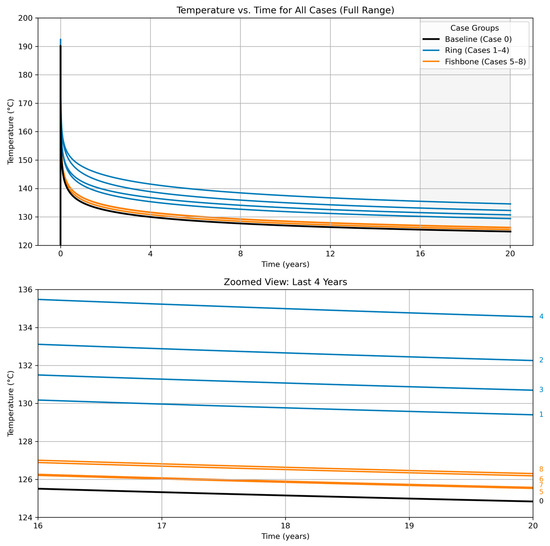

3.3. Thermal Enhancers: Rings Versus Fishbones

To evaluate the impact of design parameters, eight simulation cases were constructed for the two enhancement architectures under consideration: ring and fishbone. The cases varied both in the injected material volume fraction and the radial reach into the reservoir. The control volume framework described previously was applied; Figure 13 illustrates the geometries and associated parameters/KPIs, including reach and inclusion density (number of inclusions per unit wellbore length).

Figure 13.

3D schematic of two types of enhancers: (a) ring; (b) fishbone.

Table 3 summarizes the input parameters for these models, including geometry, inclusion thickness, reach, and inclusion density, along with the corresponding volume fractions. The second half of the table presents the simulation results, reporting the effective thermal conductivity of the enhanced cells and the relative increase in outlet temperature after 1 and 20 years of operation. Results show that outlet temperature gains scale almost linearly with injected volume fraction for both ring and fishbone geometries: doubling the fraction nearly doubles the relative gain. Reach also enhances performance, though its effect differs by geometry. For rings, increasing reach from 5 m to 10 m yields an additional ~20–25% improvement, whereas for fishbones the incremental gain is smaller (~5–10%). Thus, volume fraction emerges as the dominant factor, with reach providing a secondary but meaningful contribution, especially for ring geometries.

Table 3.

Simulation matrix and outcomes for near-wellbore conductive enhancements.

For fishbones, increasing reach and volume fraction both raise output, but the effective control volume expands radially in a non-linear manner. This dilutes the local effectiveness of the injected material, leading to diminishing incremental returns compared to rings. Figure 14 illustrates the temporal evolution of outlet temperature for all cases. The top panel shows the full 20-year production period, highlighting broadly similar long-term decline trends across enhancement strategies. The shaded region marks the final four years of operation, expanded in the lower panel. In this zoomed view, the separation between cases becomes clearer: ring configurations consistently maintain higher outlet temperatures, while fishbone cases cluster more tightly, reflecting their reduced incremental gains at extended reach and lower graphite volume fractions. Overall, the results indicate that ring enhancements deliver more pronounced and sustained improvements, particularly at longer reaches and higher injected volume fractions, resulting in higher effective conductivities and greater long-term thermal performance.

Figure 14.

This Outlet temperature over 20 years for all enhancement cases. Top: full trajectory for baseline (black), ring cases 1–4 (blue), and fishbone cases 5–8 (orange). The conductive enhancements are applied to the bottom 400 m of the wellbore reaching 5–10 m radius around the borehole.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that operational scheduling, fluid selection, and conductive enhancements each provide distinct pathways for improving the long-term performance of high-enthalpy CBHE systems. The introduction of a characteristic recovery curve extends earlier findings (e.g., [5,7]) and provides a practical framework for quantifying recovery dynamics across different operating schedules and formation properties. Its broad applicability suggests value as a design tool. The diminishing gains beyond about one month of recovery highlight a practical constraint: full thermal restoration is rarely achievable, and some degree of degradation must be accepted in both continuous and intermittent operations to varying degrees.

Working fluid analysis highlights the promise of ORC-compatible fluids such as n-pentane and R245fa, which deliver higher thermal outputs than water and enable direct integration into power cycles. Nonetheless, safety, environmental, and cost considerations remain critical, particularly regarding flammability and global warming potential. These findings underscore the need for future techno-economic assessments that weigh efficiency gains against regulatory and operational risks.

Conductive enhancement simulations further demonstrate that ring architectures provide more robust and scalable improvements than fishbones, consistent with effective medium theory predictions that continuous conductive pathways outperform discrete inclusions. While the near-linear scaling with injected volume fraction suggests adaptability to site-specific conditions, the simplified geometries modeled here represent idealized cases. Real reservoirs exhibit heterogeneity, anisotropy, and natural fractures that may alter performance. Limitations also include the use of generalized fluid property correlations and homogeneous and isotropic reservoir assumptions.

The modeling results emphasize that no single strategy is sufficient on its own. Instead, optimal CBHE design will likely require a combination of operational scheduling, fluid optimization, and selective conductive enhancements, tailored to site-specific conditions and end-use requirements. While each strategy was evaluated independently in this study, future work should also examine their combined application, as interactions among intermittent operation, ORC working fluids, and conductive filler materials may produce nonlinear rather than additive effects. Furthermore, future research should generalize the recovery curve to multi-cycle and seasonal demand profiles, evaluate low-GWP substitutes for R245fa with advanced property models, and test conductive enhancements in complex geological settings. Techno-economic and lifecycle cost analyses will be essential to translate these findings into deployment-ready metrics such as NPV and LCOE. These insights can guide the design of next-generation CBHE systems that are technically efficient, economically viable, and supportive of low-carbon energy deployment.

While n-pentane and R245fa offer favorable performance for CBHE operation, their environmental risks must be considered. An alkane such as n-pentane is flammable, requiring strict containment and safety protocols, while R245fa has a high global warming potential (GWP), necessitating careful leak prevention and recovery systems. Recent studies have identified certain hydrofluoro-olefins as promising low-GWP alternatives for organic Rankine cycles, offering comparable performance with reduced environmental impact. Incorporating such alternatives, or adopting robust mitigation strategies, should be addressed in future research for deployment of CBHE systems.

The present investigation involves several sources of uncertainty, including assumptions of homogeneous and isotropic formation properties, generalized correlations for fluid thermophysical properties, and calibration against a single field dataset. These uncertainties can be minimized in future work by incorporating anisotropy and fracture net- works, using updated property databases, and validating against multiple field cases. The HGP-A pilot data used here were collected as a single continuous run without repeated testing; therefore, error bars could not be included in simulated results. Instead, calibration accuracy was quantified using RMSE (2.03 °C) and MAE (1.42 °C). Future field studies with repeated runs would enable statistical error analysis and further strengthen reliability.

Similar to CBHE, other thermally driven energy storage and recovery methods such as adsorption heat transformation systems have been investigated for sustainable energy management [33,34]. These systems, like CBHEs, exploit thermal gradients to enable efficient energy recovery and storage. Their inclusion highlights the broader landscape of low-carbon thermal energy technologies and encourages cross-disciplinary dialogue on integrated solutions.

Beyond thermal performance, the strategies examined in this study contribute directly to energy efficiency and sustainability. Geothermal systems are consistently reported to have far lower greenhouse gas emissions than conventional fossil-fuel baseload plants, and their ability to provide dispatchable, low-impact energy aligns with global decarbonization goals. The integration of ORC fluids within CBHEs eliminates the need for surface heat exchangers, reducing parasitic losses and improving overall cycle efficiency. Similarly, conductive enhancements extend system longevity, supporting sustainable operation over decades. These findings are consistent with broader assessments of geothermal sustainability reported in recent life-cycle studies [35,36,37], which document geothermal energy’s role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting low-carbon energy deployment.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes a systematic framework for evaluating strategies to enhance heat transfer in high-enthalpy coaxial closed-loop geothermal systems. Three practical strategies were investigated:

- Intermittent operation. Longer recovery windows raise outlet temperatures and average delivered heat but with diminishing returns. The proposed characteristic recovery curve (recovery/run vs. run length) indicates ~80% recovery as a realistic design point for shorter cycles, whereas 95% recovery is operationally prohibitive except for longer seasonal shut-ins. Formation properties shift the curve in predictable ways: higher thermal conductivity and lower heat capacity shorten recovery times. Flow rate effects were negligible within the tested range;

- Working fluids. Within the sub-critical ORC temperature range, n-pentane and R245fa deliver higher thermal output than water and allow direct ORC coupling without a surface heat exchanger. However, hydraulic penalties and safety/climate considerations introduce trade-offs. Thermo-siphoning at lower flow rates for water and n-pentane suggests potential for eliminating pump requirements, while higher flow rates increased pressure drops sharply, particularly for R245fa. The Joule–Thomson sign change for n-pentane and R245fa above ~80–100 °C underscores the importance of tracking along-wellbore pressure-temperature paths in design and operation;

- Conductive enhancements. Ring architectures outperform fishbones due to their greater capacity for injected volumes and higher effective conductivity. After one year, rings yielded ~4.5–9.4% gains in outlet temperature (vs. ~0.65–1.37% for fishbones); after 20 years, gains remain at ~3.7–7.8% for rings (vs. ~0.55–1.18% for fishbones). Performance scaled approximately linearly with injected volume fraction for both geometries. Reach further amplified performance, with rings showing ~20–25% relative improvement when extended from 5 to 10 m, compared with ~5–10% for fishbones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and K.S.; methodology, K.K.; software, K.S.; validation, K.K. and K.S.; formal analysis, K.K. and A.R.S.; investigation, K.K. and A.R.S.; resources, S.L. and K.S.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and A.R.S.; writing—review and editing, A.R.S., S.L., and K.S.; visualization, K.K.; supervision, S.L. and K.S.; project administration, S.L. and K.S.; funding acquisition, S.L. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project from the Hildebrand Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering at the University of Texas at Austin is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Silviu Livescu was employed by the company Bedrock Energy. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. All authors declare that there are no relationships or interests that could inappropriately influence or bias the work presented in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBHE | Coaxial Borehole Heat Exchanger |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| NIST | The National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| ORC | Organic Rankine Cycle |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| KPI | key performance indicator |

| EMT | effective medium theory |

| CV | Control Volume |

| JT | Joule–Thomson |

References

- Movahedzadeh, Z.; Shokri, A.R.; Chalaturnyk, R.; Nickel, E.; Sacuta, N. Measurement, monitoring, verification and modelling at the Aquistore CO2 storage site. First Break. 2021, 39, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, K.P.; Brehme, M.; Shokri, A.R.; Malakooti, R.; Nickel, E.; Chalaturnyk, R.J.; Saar, M.O. CCS coupled with CO2 plume geothermal operations: Enhancing CO2 sequestration and reducing risks. Geothermics 2025, 133, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Jia, G.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L. Analysis of economy, thermal efficiency and environmental impact of geothermal heating system based on life cycle assessments. Appl. Energy 2021, 303, 117671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tomac, I. Feasibility of coaxial deep borehole heat exchangers in southern California. Geotherm. Energy 2024, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Sasmito, A.P.; Sainoki, A.; Tosha, T.; Tanaka, T.; Nagai, C.; Ghoreishi-Madiseh, S.A. Field-scale experimental and numerical analysis of a downhole coaxial heat exchanger for geothermal energy production. Renew. Energy 2022, 182, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, G.; Shi, Y.; Peng, C.; Tan, Y. Performance analysis of a downhole coaxial heat exchanger geothermal system with various working fluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 163, 114317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Hu, Z.; Feng, B.; Feng, G.; Li, F.; Jiang, Z. Numerical evaluation of building heating potential from a co-axial closed-loop geothermal system using wellbore–reservoir coupling numerical model. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2019, 38, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhu, K.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Kong, W.; Jiang, Y.; Fang, Z. Heat transfer performance of deep borehole heat exchanger with different operation modes. Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Ma, Z.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Chai, J.; Jin, L. A finite-volume method for full-scale simulations of coaxial borehole heat exchangers with different structural parameters, geological and operating conditions. Renew. Energy 2022, 182, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, J.; Sharma, P.; Al Saedi, A.; Kabir, S. Techno-economic analysis of green energy resources for power generation & direct use by preserving near-wellbore geothermal gradient. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoppi, G.; Biliotti, D.; Ferrara, G.; Carnevale, E.; Ferrari, L. Feasibility Study of a Geothermal Power Plant with a Double-pipe Heat Exchanger. Energy Procedia 2015, 81, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-H.; Liu, M.-C.; Yeh, R.-H. Investigation of low-GWP working fluids as substitutes for R245fa in organic Rankine cycle application. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstrom, P.J. NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sun, L.; Fu, B.; Wei, M.; Zhang, S. Analysis of Enhanced Heat Transfer Characteristics of Coaxial Borehole Heat Exchanger. Processes 2022, 10, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, T.; Pan, L.; Doran, H.; Falcone, G.; Verdin, P.G. Numerical Analysis of Enhanced Conductive Deep Borehole Heat Exchangers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, H. Geothermal Well Using Graphite as Solid Conductor. U.S. Patent 20110232858A1, 29 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buchi, H.F. Method and Apparatus for Extracting and Utilizing Geothermal Energy. U.S. Patent 4912941A, 3 April 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi, K.; Livescu, S.; Sepehrnoori, K. A Comprehensive Techno-Economic Optimization Framework for Deep Geothermal Coaxial Closed-loop System. J. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Taleghani, A.D. Factors affecting the efficiency of closed-loop geothermal wells. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 222, 119947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissembayev, N.; Al-Braiki, A.M.; Bakri, H.; Turniyazov, N.; Soliman, I.; Malak, M.; Rashid, S. Maximizing Efficiency: Coiled Tubing Success in Cutting Needles for Fishbones Completion. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 4–7 November 2024; p. D011S8R05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, K.F.; Ketchum, A.M.; Augustine, C.R. (Eds.) Evaluating Heat Extraction Performance of Closed-Loop Geothermal Systems with Thermally Conductive Enhancements in Conduction-Only Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the 49th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 12 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Yu, B.; Yun, M.; Zou, M. Heat conduction in fractal tree-like branched networks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2006, 49, 3746–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computer Modelling Group, L. STARS. Thermal and Advanced Processes Reservoir Simulator; Computer Modelling Group Ltd.: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, K.; Bollmeier, W.S.; Mizogami, H. An Experiment to Prove the Concept of the Downhole Coaxial Heat Exchanger (DCHE) in Hawaii. Geotherm. Resour. Counc. Trans. 1992, 16, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, K.; Bollmeier, W.S.; Mizogami, H. Analysis of the Results from the Downhole Coaxial Heat Exchanger (DCHE) Experiment in Hawaii. Geothermal Resources Council Trans. 1992, 16, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Vasyliv, Y.; Beckers, K.; Martinez, M.; Balestra, P.; Parisi, C.; Augustine, C.; Bran-Anleu, G.; Horne, R.; Pauley, L.; et al. Numerical investigation of closed-loop geothermal systems in deep geothermal reservoirs. Geothermics 2024, 116, 102852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoqing, S.; Ming, J.; Peiwen, X. Analysis of the Thermophysical Properties and Influencing Factors of Various Rock Types from the Guizhou Province. In Proceedings of the E3s Web of Conferences, Bali, Indonesia, 6–8 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.I.; Kesler, M.G. A generalized thermodynamic correlation based on three-parameter corresponding states. AIChE J. 1975, 21, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, J.P. Heat Transfer, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hashin, Z.; Shtrikman, S. A Variational Approach to the Theory of the Effective Magnetic Permeability of Multiphase Materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1962, 33, 3125–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalc, M.; Skandakumaran, P.; Norley, J. Thermal Performance of Natural Graphite Heat Spreaders with Embedded Thermal Vias. In Proceedings of the International Electronic Packaging Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–22 July 2007; pp. 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Shao, H.; Naumov, D.; Kong, Y.; Tu, K.; Kolditz, O. Numerical investigation on the performance, sustainability, and efficiency of the deep borehole heat exchanger system for building heating. Geotherm. Energy 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Saha, B.B. Enhancing Cooling and Atmospheric Water Harvesting via Zeolite-MOF Composites: Experimental and Thermodynamic Evaluation of MIL-160 (Al) and AFI-Type Zeolite Hybrid Adsorbents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 17635–17656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ng, M.S.; Chakraborty, A. Optimizing metal-organic frameworks for adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting: A systematic evaluation of pristine and modified MOFs for enhanced performance in diverse climates. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, A.; Heath, G.; Carpenter Petri, A.; Nicholson, S. Systematic Review of Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Geothermal Electricity; Technical Report for National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, A.; Jennejohn, D.; Blodgett, L. Geothermal Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Geothermal Energy Association (GEA): Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://geothermal.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Geothermal_Greenhouse_Emissions_2012_0.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Fridriksson, T.; Mateos, A.; Orucu, Y.; Audinet, P. Greenhouse gas emissions from geothermal power production. In Proceedings of the 42nd Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 13–15 February 2017; Available online: https://pangea.stanford.edu/ERE/pdf/IGAstandard/SGW/2017/Fridriksson.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).