Abstract

Manufacturers of cutting and machining machines face increasing pressure to optimize performance and sustainability while complying with evolving regulations. Traditional machine learning approaches are often limited by biased and repetitive datasets collected during real operations. This article presents a real-time simulation framework for generating large synthetic datasets to train predictive machining models. A mechanistic model with probabilistic parameters is validated on experimental data and integrated into the simulator, enabling neural networks to predict process metrics such as vibrations, cutting forces, and product quality prior to machining. The framework further supports large-scale optimal control by testing setpoint control strategies for virtual prototyping. This approach allows manufacturers to enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and improve product quality while minimizing operational risks.

1. Introduction

Predicting the performance of machining processes is becoming essential in the manufacturing industry [1]. Due to the rising and unpredictable cost of energy, careful planning and management can save resources, increase business profitability, and improve the sustainability of energy sources. For this reason, many machine manufacturers are seeking tailored energy prediction models for their energy-intensive machines, tools that enable performance prediction before the process starts. Typical objective performance metrics for a machining process can include estimates of energy consumption, tool vibrations, product surface refinement, and temperature.

Deep Learning (DL) and Machine Learning (ML) techniques are becoming essential tools to predict tool wear, limit machine faults and damages and evaluate cutting performances. Hundreds of literature articles discuss the application of ML and DL techniques to the prediction of tool wear [2,3,4,5]. In [6], the authors combined modal decomposition and convolutional neural networks to monitor the tool wear in real time. To monitor tool wear, measuring vibrations, forces, and acoustic emissions over time during the same repetitive operation is the best way to obtain a dataset consistent with the study objective. Such a dataset enables analysis of variations and drifts in both tool and machine wear. While tool wear is a progressive phenomenon, unexpected faults may also occur during machining. Therefore, many monitoring techniques can be extended to fault detection, providing early warnings of abnormal conditions that may compromise process stability or damage the machine [7]. In this context, building a comprehensive dataset is particularly challenging because of the wide variety of potential faults. Beyond fault detection, ML and DL methods are also increasingly applied to the evaluation of machining performances [8]. Key indicators such as surface roughness and power consumption are widely studied, since they directly affect both the sustainability and the quality of the manufacturing process. In [9], the authors test different combined Fast Fourier Transform and Deep Learning (FFT-DL) techniques for evaluating surface roughness using vibration signals and accelerometers. In [10], the authors review many ML techniques for power consumption estimation and introduce random forests and decision trees to predict the energy consumption of a milling machine.

The main challenge for training a deep learning (DL) model for performance estimation is collecting a comprehensive dataset over different operating conditions. An acceptable data set for DL and ML training must be large, structured, unbiased, uncorrelated, and variable [11]. Big data is often available in manufacturing companies; however, due to the high number of repetitions in batch production processes, these data are often biased and redundant. These datasets are particularly suitable for investigating drifts and progressive tool wear, but they are not adequate for estimating performance indicators that can only be assessed under varying conditions and machining operations. Therefore, despite the large amount of available data, only a small portion is truly relevant. Since the accuracy of a DL model strongly depends on the quality of the training dataset, data collected during batch production cannot be considered a reliable starting point for developing a data-driven model of machining performance. In addition, acquiring large experimental datasets is both complex and costly, due to the wide variety of machining processes and operational procedures required for training. For this reason, synthetic data generation techniques are considered a valid framework for generating data sets for complex manufacturing systems [12].

Synthetic data generation techniques are developed to complete a partial dataset or to generate a new dataset from significant data, using stochastic analytical models. The authors in [13] provide a promising example of using finite element simulations to generate unavailable data (forces during milling) and a generative adversarial network to augment a fictitious dataset aimed at estimating tool wear. A different methodology is developed in [14], in which the researchers propose a discrete-event simulation to generate a large dataset for training ML models for manufacturing productivity. Simulated Digital Twins can serve as a starting point for generating data.

Digital Twin (DT) models serve as reliable simulation-based replicas of real-world plants [15,16]. For instance, in [17], the authors propose a multiphysics DT for a CNC machine. A major challenge in implementing multiphysics DTs is simulating dynamics that occur on different time scales within an acceptable overall simulation time. Electrical variations occur at very high frequencies (on the order of microseconds to milliseconds), while mechanical and thermal transients evolve over milliseconds or even minutes. This mismatch leads to a computational bottleneck. To address this issue, the use of suitable real-time hardware can significantly enhance DT simulation performance. The benefits of employing real-time hardware to extend or generate datasets are manifold: data can be made available quickly and generated under varying process parameters; noise can be easily introduced to introduce variability; and, finally, long-duration simulations can be executed in real time.

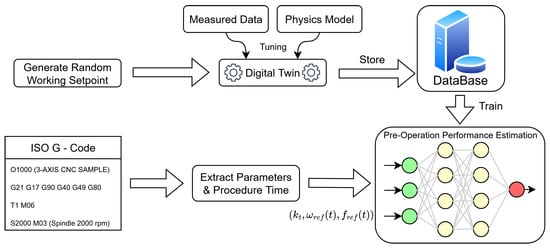

This paper proposes a framework for generating real-time, big, stochastic synthetic data with a wide variety of cutting conditions. A flowchart presenting the objective of the work is presented in Figure 1. Several temporal measurements are used to validate a digital twin of a manufacturing wood profiling machine. The digital twin is implemented in a real-time simulator for generating system data in real time. The hardware simulation is interfaced with an external server that serves as an OPC-UA database. An external training algorithm manages the data during real-time dataset generation for training feedforward Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) until a training termination criterion is met. Then, two data-driven ANNs are used as a fast model to optimise the machine’s performance under different objective functions and to predict profiling performance before the operation.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the work presented by the paper.

2. Methodology

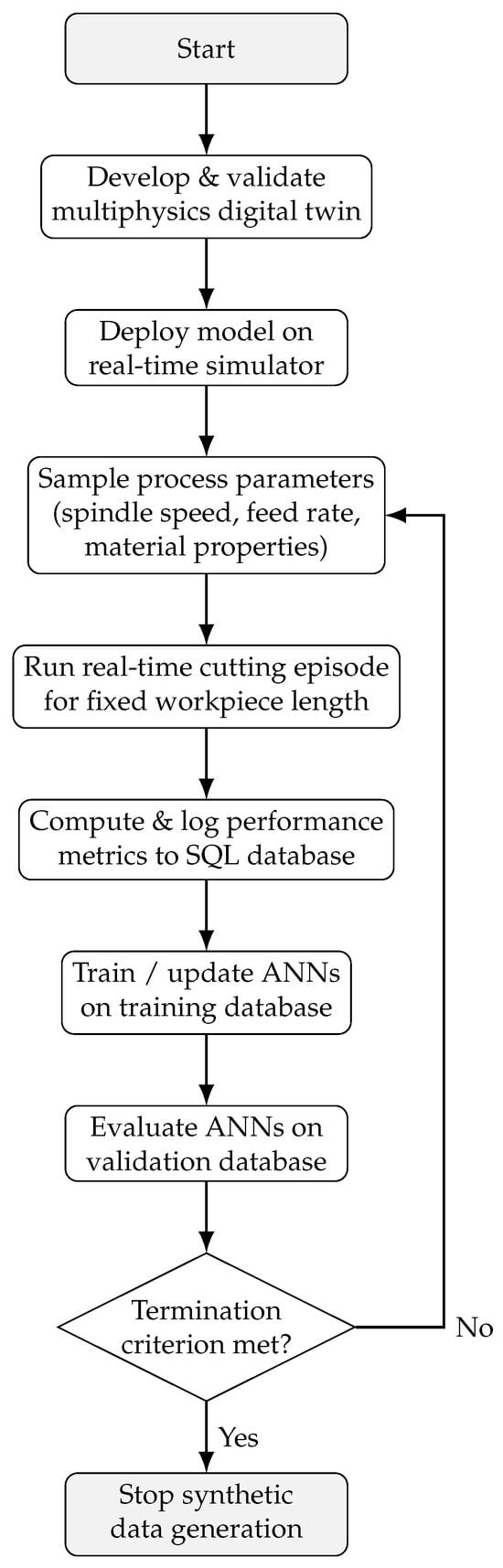

This section describes the proposed framework for generating synthetic datasets for machining performance prediction by means of a real-time simulation of a validated digital twin of a CNC machine (a flow chart is reported in Figure 2). The workflow combines the development and validation of a multiphysics digital twin, its deployment on a real-time hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) platform, and the online generation and management of synthetic cutting episodes for training feedforward artificial neural networks (ANNs) that estimate energy consumption and vibration-related quality indicators.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the proposed methodology for synthetic data generation and ANN training using a real-time digital twin of the machining process.

2.1. Digital Twin Modelling and Validation

A multiphysics digital twin of the CNC profiling machine is created by coupling detailed electrical drive models with a nonlinear mechanistic model of the cutting process. The electrical subsystem includes the field-oriented control of the spindle and feed drives. In contrast, the mechanical subsystem describes the cutting forces and tool vibrations as functions of spindle speed, feed rate, and tool geometry and workpiece properties. The cutting dynamics are modeled through a reduced-order system of second-order differential equations in the tool-tip displacements, excited by time-varying cutting forces obtained from a chip thickness formulation. Material-related uncertainties are represented via stochastic variations of the specific cutting energy, enabling the model to reproduce realistic dispersion in process responses. Model parameters are tuned and validated against experimental measurements of spindle current, torque and vibration signals acquired on the real machine during representative cutting tests.

2.2. Real-Time Hardware-in-the-Loop Setup

The validated digital twin is deployed on a real-time simulator. The model is executed with a fixed integration step suitable to capture the fastest electrical dynamics while preserving real-time capability. An OPC UA interface connects the real-time hardware to an external server that acts both as a supervisory controller and as a data management system. For each cutting episode, the server sends a new set of process parameters to the real-time simulator, including spindle speed, feed rate, and material-specific cutting energy. The simulator tracks these references and performs the virtual machining of a fixed workpiece length. During the episode, relevant process quantities are computed in real time, such as instantaneous power, cumulative energy consumption, and average tool vibration amplitudes along the principal axes. At the end of the episode, summary performance indicators are returned to the server and stored in a structured SQL database together with the corresponding input parameters.

2.3. Synthetic Dataset Generation and ANN Training

Synthetic data are generated as a sequence of independent cutting episodes. For each episode, the process parameters are sampled from a predefined probability distribution within admissible operating ranges, to uniformly explore the feasible space of cutting conditions while avoiding unsafe or unrealistic condition configurations. The first subset of episodes is reserved as a validation database, whereas the remaining episodes are progressively added to the training database. After a given number of new episodes have been simulated, the real-time execution is paused and the current training database is used to update the weights of two feedforward ANNs: one for predicting total energy consumption and one for predicting vibration-based quality indices. Each ANN is implemented as a three-layer network with a decreasing number of neurons per layer, using nonlinear activation functions and standard gradient-based optimization. After each training step, the updated ANNs are evaluated on the fixed validation database, and the root-mean-square (RMS) prediction error is monitored. Data generation and retraining continue until the termination criterion is satisfied, for example, when the decrease in validation RMS error falls below a prescribed gradient threshold, indicating that additional synthetic episodes provide marginal benefit and may lead to overfitting.

3. The Proposed Framework: Modelling a Wood Profiling Machine

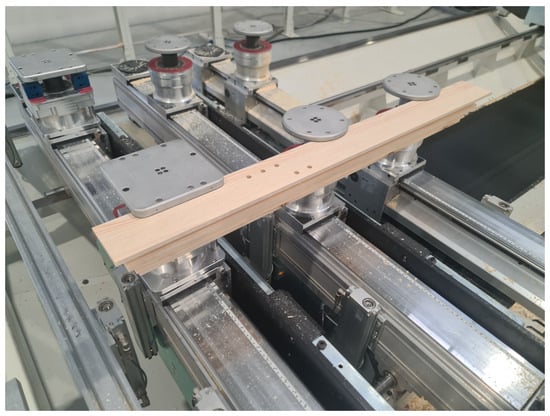

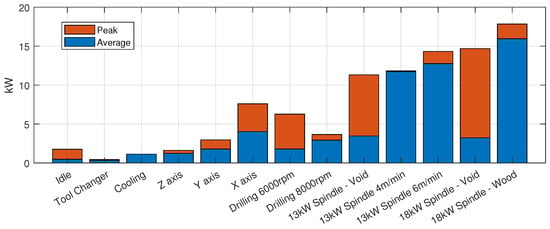

A numerical control machine for wood profiling has been considered for the development of the framework. The machined wood piece used for the tuning of the digital twin is shown in Figure 3. Several experimental tests have been carried out on the machine to collect different parameters, including electromechanical time-series data, total power consumption, and motion profiles studied in the time domain. The results of the power measurements for the various tests are reported in the bar plot of Figure 4. Based on these data, the static power consumption is modelled through a discrete-event finite state machine implemented in the real-time simulator, with each state associated with a specific power demand as in [18]. Conversely, the dynamic power consumption related to the motion is analysed in the time domain using reduced-order dynamic models. As shown in the bar plot, the cutting phase is the most energy-intensive stage of the machining process.

Figure 3.

Picture of the clamped wood workpiece machined by a CNC for wood profiling.

Figure 4.

Analysis of power consumption of different auxiliaries and principal motors of the CNC machine.

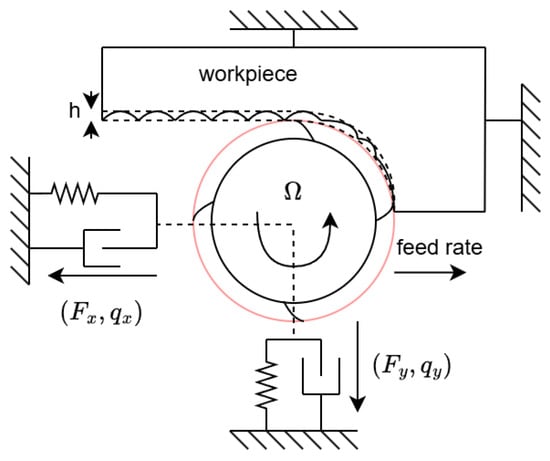

The multiphysical model of the machine is mainly inferred from the physics and validated using several milling tests. The modelling is carried out in Simulink using the specialized electrical power system toolbox. The electromechanical model of two motors is implemented and it is interfaced with a nonlinear mechanistic model of the cutting tool. The nonlinear mechanical model can determine not only the forces acting on the lead to intense vibrations that can ruin the surface roughness of the final product, which can be modelled as proposed in [19,20] and modelled and is briefly discussed here. Figure 5 illustrates the physics of the cutting where all mechanical coefficients used in the vibration model are: and , damping coefficients and , and stiffness values and . These parameters were identified through impact-hammer tests conducted by the manufacturer and refined using vibration measurements obtained during the cutting experiments. Thermal stresses were not included in the present model because the profiling operations studied have very short engagement durations (typically 2–5 s), during which the measured spindle temperature rise was below 1 °C. Preliminary tests using onboard temperature sensors confirmed that the thermal transient is negligible compared to the mechanical and electrical dynamics. Additionally, the current real-time model focuses on electromechanical interactions, and integrating a full thermal subsystem is part of future development.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the mechanical system of the cutting dynamics.

A tool with N cutting edges rotating at with a linear feedrate of f is cutting the workpiece. The workpiece is considered clamped to the system, while the tool can vibrate due to cutting forces acting over the cutting plane. The mechanical Equation (1) represent the force balance for the tool depending on the tool mass, damping and stiffness parameters:

The x-axis and y-axis vibration amplitude for the tool can be easily retrieved by numerically solving the two equations for the couple . During the process, an important performance index for evaluating the cutting procedure is surface roughness. This quantity depends directly on the tool’s vibrations during the process. Thus, it is indirectly dependent on the forces applied during the cutting, on the cutting parameters, and the geometry of the cutting tool. The first step for the calculation of the cutting force is to estimate the chip thickness as a sum of harmonic contributions:

where and are the periods between two cutting edges for the x and y-axis. The amplitudes for the two harmonics are evaluated as:

while the rotational angle the cutting edge is:

assuming that the chip is cut by consecutive cutting edges without regenerative effects. The tangential and radial components for the forces acting on the cutting tool are defined by:

where the and are the specific cutting energy and the proportionality factor, is the coefficient , is the rake angle of the cutting tooth, is the friction coefficient of the sliding tool over the material and is the helix angle of the tool. Since wood is an amorphous material, a time-integral zero-mean gaussian noise is added to the specific cutting energy:

An integral gaussian noise is capable of simulating persistent variations in the material toughness more than the instantaneous gaussian noise.

The resulting planar forces can be calculated by summing all the contribution for each cutting edge for the forces:

where is an activation function representing the immersion of each flute in the workpiece.

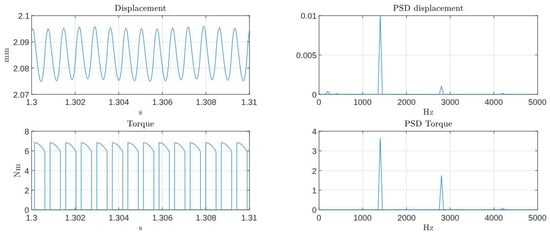

In Figure 6, illustrates the simulated tool displacement and spindle torque together with their spectral densities. The dominant peaks observed in both spectra correspond to the tooth-passing frequency , confirming that the mechanistic force model correctly reproduces periodic force excitation caused by the cutting edges. The displacement spectrum also reveals secondary harmonics associated with chip-thickness modulation, which directly influence the surface-quality index used later in the ANN training. These findings demonstrate that the vibration amplitude predicted by the reduced-order model captures the fundamental dynamics governing surface roughness, thereby validating the model’s suitability for generating synthetic datasets. The parameter used are listed in Table 1. Those parameters were selected based on a combination of manufacturer specifications for the tool and spindle, direct measurement of geometric and dynamic quantities, and standard values reported in milling literature. Candidate parameters such as tool run-out, spindle bearing compliance, and thermal drift were evaluated during preliminary tests; however, their inclusion did not significantly improve model accuracy within the short cutting intervals considered. For this reason, the final parameter set balances physical completeness and real-time feasibility while maintaining strong agreement with the experimental validation data.

Figure 6.

Average displacement and torque including the spectral density of the two quantities.

Table 1.

Parameters used for testing the model.

The forces are employed in the mechanical transfer functions in Equation (1) to determine the displacement amplitude in the two Cartesian coordinates.

4. Model Validation

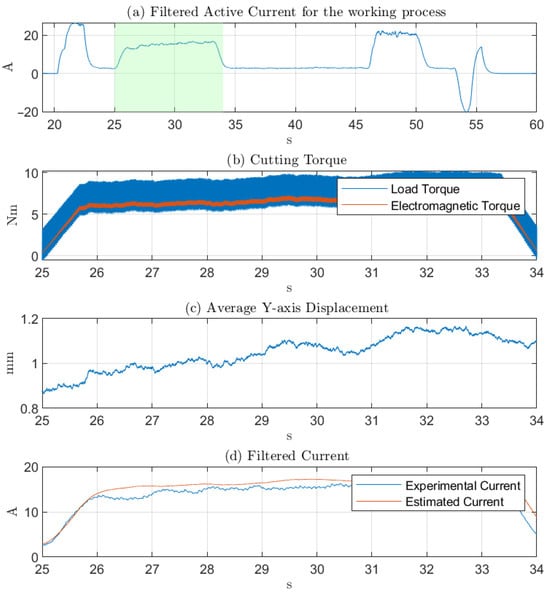

The digital twin is validated through a systematic comparison between simulated responses and experimental measurements collected on the physical CNC profiling machine. The objective is to ensure that the multiphysics model accurately captures the coupled electrical, mechanical, and cutting dynamics under a broad range of operating conditions. A dedicated set of machining tests is carried out on the real machine, covering representative combinations of spindle speeds, feed rates and tool engagement conditions. During each test, high-frequency measurements of spindle current, axis torques and tri-axial vibration signals are acquired using synchronized data-acquisition hardware. These measurements, after appropriate filtering and time alignment, form the ground-truth dataset used for validation. In Figure 7 the simulation is compared with the experimental data for the filtered active current. The filtered active current is measured before the DC-AC converter of the spindle and represents the active power delivered to the spindle with acceptable accuracy. In Figure 7a, the filtered active current is presented for the whole process. The green zone is used to present the other quantities. The Figure 7b highlights the load and active torque vibrations estimated with the mechanistic model, while in Figure 7c, the displacement over the y-axis is presented. Finally, the real data for the active current are compared to the model estimation in Figure 7d. For this simulation, the offset for the specific cutting energy for the testing material (pine wood, Figure 3) has been tuned to 35 with for the noise component in Equation (5).

Figure 7.

Validation of the model for the active current using real dataset.

The proposed framework generalizes naturally to different materials and operating conditions because the material-dependent terms—primarily the specific cutting energy and its stochastic component are explicitly parameterized. By sampling these parameters probabilistically across admissible ranges, the synthetic dataset spans a broad operating domain, enabling ANNs to learn transferable relationships between cutting conditions and performance indicators. Only the material coefficients require recalibration when switching to new workpiece types, whereas the digital twin, real-time execution, and ANN training structure remain unchanged.

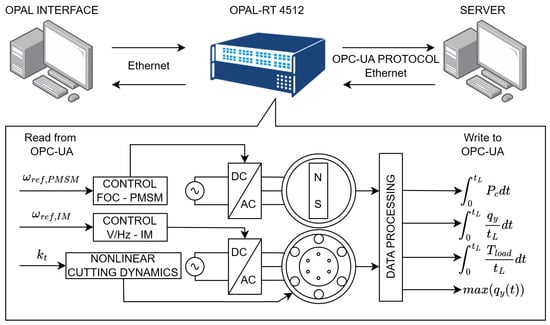

5. Real-Time Hardware in the Loop Setup

The setup is illustrated in Figure 8. The real-time simulator is an Opal-4512. The model is uploaded to the setup with an execution time of 10 μs. The model is executed in sequential cutting episodes. For each cutting episode, the server generates a random value for the feed rate, spindle rotational velocity, and specific cutting energy, and forwards it to the real-time simulation via OPC-UA. The simulation uses the velocities as references for the motors and the specific cutting energy is employed in the vibration model. The reference parameters are kept until the machine model cuts a fixed length of 1 m of material. As the final step of the cutting episode, the real-time simulation feeds back the cutting performance, including power consumption, total energy consumption, and vibration amplitude. The values are sent back to update the OPC-UA server and are stored in a SQL database on an external device. The SQL database is used to train the performance feedforward ANNs.

Figure 8.

Scheme of the Hardware In the Loop setup and simulation.

6. Real-Time Training of the Performance ANNs

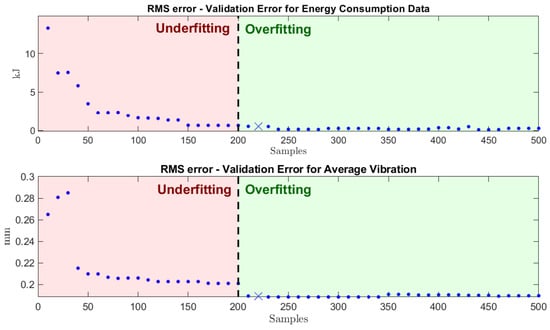

In the framework of synthetic dataset generation, sizing a database for ML and DL applications is crucial. Training on a small or biased dataset may not capture all the features of the selected quantity. When this happens, the ANN is underfitting the dataset. On the other hand, large datasets are sometimes unnecessary and can lead to overfitting the trend.

The feedforward ANNs are trained during the real-time simulation of the DT. The first 150 cutting episodes are stored in a validation SQL database. The other cutting episodes are then stored in a training SQL database. Every 10 iterations, the real-time hardware is kept idle, and the ANNs are trained over the training database. The ANN are made of three layers with decreasing number of nodes (35, 20, 4). The weights and biases are instantiated randomly. After each training, the resulting ANNs are tested over the validation dataset. Experimental data for model validation were collected on the CNC profiling machine using a synchronized acquisition system. The active spindle current was measured upstream of the DC-AC converter (see Figure 7), axis torques were obtained from integrated torque sensors, and tri-axial accelerometers were mounted on the spindle housing to capture vibration responses along the x, y, and z axes. All data were sampled during the cutting phase of the wood-profiling process, which is the most energy-intensive stage, ensuring that the validation dataset reflects the dynamic conditions the digital twin is intended to reproduce.

The trained weights and biases are then used as a starting point for the next training. A termination criterion for generating the synthetic database can be obtained by selecting a gradient threshold over the decaying RMS error. The resulting rms errors () for the two quantities are presented in Figure 9. An acceptable dataset size is selected at the end of the underfitting region, approximately at 220 cutting episodes. ANN performance was evaluated using both RMS error shown in Figure 9 and mean-square error (MSE). For each validation episode, the MSE was computed as where and denote the experimental and ANN-predicted performance indicators, respectively. The best-performing ANNs achieved an MSE of for energy prediction and for vibration amplitude, consistent with the convergence trend observed in the RMS curves of Figure 9. These results confirm the reliability of the ANN models for downstream optimization tasks.

Figure 9.

Rms error for the power consumption and the vibrations ANN with respect to the validation database.

7. Results

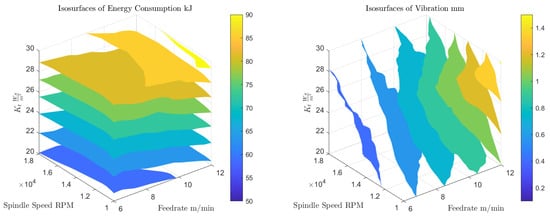

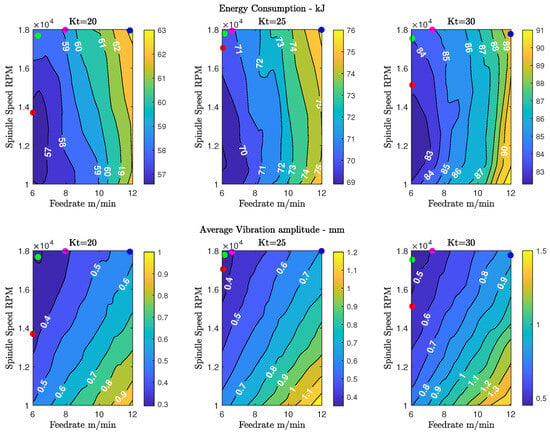

The trained ANNs are presented in Figure 10 as 3D isosurfaces and in Figure 11 as contour plots. As highlighted in Figure 10, the energy consumed and the spindle y-axis vibrations have different trends. The machine consumes more energy when it cuts tougher materials with higher feed rates. On the other hand, the vibrations increase for higher feed rates and material toughness and decreases when the spindle rotates faster. The ANN are evaluated for three different specific cutting energies () in Figure 11. Here, some markers on the contour plots highlight the best cutting parameters (spindle speed and feed rate) for different desired conditions. The parameters for these cutting operations are collected using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) optimization over the ANN models. The problem is formally stated in Equation (6):

where the constraints are the lower and the upper bounds for the two quantities:

Figure 10.

Isosurfaces.

Figure 11.

Contours obtained by the ANN for different specific cutting energies and optimal operational points.

A weighted multiobjective cost function is used with different weights to determine the:

The blue marker refers to the less time consuming operation , the red marker refers to the less power consuming operation , the green marker refers to the less vibration amplitude operation and the magenta represents a trade-off between the three different conditions.

8. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of real-time, simulation-based synthetic data generation for enhancing data-driven modeling in machining applications. Unlike traditional methodologies, which often rely on labor-intensive experimental campaigns or limited offline simulations, the proposed framework integrates a validated multiphysics digital twin with a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) architecture. This innovation facilitates the rapid generation of large, diverse, and physically consistent datasets without incurring the costs and wear associated with extended machine operation.

The incorporation of stochastic variations in material properties effectively models realistic dispersion in spindle load and tool vibration responses, an area often overlooked in deterministic cutting-force models. This framework enables on-demand synthetic data generation, allowing for iterative training of artificial neural networks (ANNs) and introducing a level of adaptability not typically found in static dataset-driven approaches.

However, limitations include reliance on the digital twin’s accuracy, potential discrepancies under extreme cutting conditions, and fixed assumptions about workpiece geometry and depth of cut. Additionally, reliance on scalar performance indicators may limit the predictive capabilities of trained ANNs, necessitating the use of advanced architectures to support more complex representations.

Despite these limitations, the findings suggest that a hybrid physics–data-driven approach is a compelling alternative to conventional experimental or numerical strategies in machining research. The methodology addresses the issues of biased datasets, enabling efficient data generation while minimizing equipment risk and material waste. Future work should extend this framework to additional machining processes, incorporate additional physical phenomena, and explore online learning strategies to enhance predictive accuracy in dynamic environments, thereby improving robustness and applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and G.G.; methodology, E.S.; software, E.S.; validation, E.S.; formal analysis, E.S. and G.G.; investigation, E.S.; resources, E.S. and G.G.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and G.G.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, E.S. and G.G.; project administration, E.S. and G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in Italy–Circular and Sustainable) Extended Partnership and received funding from Next-Generation EU (Italian PNRR M4 C2, Invest 1.3 D.D. 1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004). CUP MICS D43C22003120001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The files are uploaded on https://github.com/EnricoSpateri.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cristaldi, L.; Esmaili, P.; Gruosso, G.; La Bella, A.; Mecella, M.; Scattolini, R.; Arman, A.; Susto, G.A.; Tanca, L. The MICS Project: A Data Science Pipeline for Industry 4.0 Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for Extended Reality Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering Metroxraine, Milano, Italy, 25–27 October 2023; pp. 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Bustillo, A.; Wojciechowski, S.; Sharma, V.S.; Gupta, M.K.; Kuntoğlu, M. Artificial intelligence systems for tool condition monitoring in machining: Analysis and critical review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 2079–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampopoulos, A.; Alexopoulos, K.; Catti, P.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Learning More with Less Data in Manufacturing: The Case of Turning Tool Wear Assessment through Active and Transfer Learning. Processes 2024, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynivand, M.; Esmaili, P.; Cristaldi, L.; Gruosso, G. Modern Digital Twin for Validation and Generation of Datasets for Machine Tool Spindle Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Napoli, Italy, 19–21 June 2024; pp. 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynivand, M.; Gruosso, G. Data-Driven Monitoring and Benchmarking of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Using Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the IECON 2024—50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pang, X.; Zhang, Q. Wear Prediction of Tool Based on Modal Decomposition and MCNN-BiLSTM. Processes 2023, 11, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano Leija, A.B.; Ruiz Beltrán, E.; Orozco Mora, J.L.; Valdés Valadez, J.O. Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms in Fault Diagnosis for Manufacturing Systems: A Comparative Analysis. Processes 2025, 13, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in CNC machine tools, A review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2023, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.J.; Lo, S.H.; Young, H.T.; Hung, C.L. Evaluation of Deep Learning Neural Networks for Surface Roughness Prediction Using Vibration Signal Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillinger, M.; Wuwer, M.; Abdul Hadi, M.; Haas, F. Energy prediction for CNC machining with machine learning. Cirp J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tnani, M.A.; Feil, M.; Diepold, K. Smart Data Collection System for Brownfield CNC Milling Machines: A New Benchmark Dataset for Data-Driven Machine Monitoring. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, K.; Nikolakis, N.; Chryssolouris, G. Digital twin-driven supervised machine learning for the development of artificial intelligence applications in manufacturing. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 33, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, W.; Xiang, J. Sample Augmentation for Intelligent Milling Tool Wear Condition Monitoring Using Numerical Simulation and Generative Adversarial Network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3516610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Rabaev, M.; Pratama, H. Generation of synthetic manufacturing datasets for machine learning using discrete-event simulation. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2022, 10, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D.; Van der Auweraer, H. Digital Twins. In Progress in Industrial Mathematics: Success Stories; Cruz, M., Parés, C., Quintela, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, C.; Ferretti, G.; Leva, A. The role of dynamics in digital twins and its problem-tailored representation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10556–10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hu, T.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Y. Digital twin for CNC machine tool: Modeling and using strategy. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Tang, R.; Lv, J.; Yuan, Q.; Peng, T. Energy consumption modeling of machining transient states based on finite state machine. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 2305–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, B. Nonlinear Dynamics of Milling Processes. Philos. Trans. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2001, 359, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, S.; Agarwal, A.; Desai, K.A. Machine learning-based instantaneous cutting force model for end milling operation. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).