Abstract

For the first time, Eriolobus trilobatus bark from Turkey has been characterized in terms of its chemical, extractive, fuel, and ash characteristics using SEM–EDS, wet chemical analysis, phenolic analysis, FT-IR, TGA, XRF, XRD, BET surface area measurement, proximate analysis, and ash fusion temperature (AFT) determination. The results showed that the bark contains 13% ash, dominated by calcium oxalate, and 15% extractives, largely composed of polar phenolic compounds with moderate radical-scavenging potential. Thermal decomposition of bark proceeds in four distinct stages, associated with the sequential degradation of extractives/hemicelluloses, cellulose, lignin/suberin, and inorganic fractions. The higher calorific value of 14.9 MJ/kg indicates moderate fuel quality compared with conventional woody biomass. Ash is mesoporous with a CaO-rich structure highly suitable for catalytic applications in biodiesel production and biomass gasification. Ash fusion analysis revealed a high flow temperature (1452 °C), indicating a very low slagging risk during thermochemical conversion. Overall, E. trilobatus bark is a promising material for value-added biorefinery pathways, enabling processes for the production of biochars, CaO-based catalysts, phenolic extracts, and sustainable energy. The valorization of E. trilobatus bark not only enhances the economic potential of forestry residues but also provides environmental co-benefits through carbon soil amendment and landscape applications.

1. Introduction

Eriolobus trilobatus (Labill. ex Poir.) M.Roem. is a rare small ornamental tree with a scattered and limited distribution in Asia Minor and nearby areas, occurring in particular in Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria, Syria, and Lebanon reaching up to 1200 m and commonly found along the edges of fields, rocky slopes, forests and forest clearings as its natural habitat [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The species is also known as Malus trilobata [8]. The first report on the species dates back to 1787 [6] and the name of the species was published for the first time as Eriolobus trilobatus [9]. The species was suggested to be a hybrid of Sorbus and Malus [10]. Recently, it was listed as “near threatened” in the global assessment of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

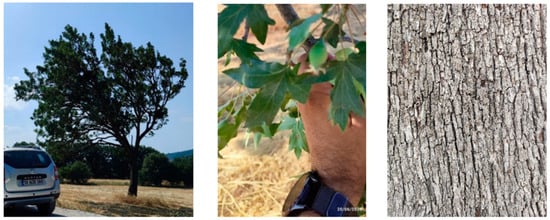

The species is a deciduous tree reaching up to 10 m in height, usually forming a rounded to spreading crown. The leaves are 5–7 cm long, deeply trilobed with a cordate base and finely dentate margins (Figure 1). The umbelliform inflorescences bear 6–8 aromatic white flowers, each 3–4 cm in diameter, with five sepals, five petals as specific to the Rosaceae family, and 20–30 stamens. The fruit is a pale-yellow drupe, oblong to rounded in shape, containing stone cells, and becomes edible once fully mellowed, despite its initial astringency. Flowering occurs from May to June, followed by fruiting between September and October. The species is insect-pollinated and propagates mainly by seed [11].

Figure 1.

Appearance of a solitary Eriolobus trilobatus tree in Balıkesir, Turkey (left), its leaves and fruits (middle), and bark (right).

In Turkey, the plant is naturally distributed in the southwestern regions [5,12] commonly known as apple of the deer or apple of the horse [13], and widely used as an edible fruit, natural dye, and folk medicine [14]. The branches and the leaves are used for the dying of traditional carpets [14]. The fruits are sold in local markets and used as a traditional folk medicine to treat various illnesses including cholesterol, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases [8,15,16,17].

The leaves, flowers, and fruits of E. trilobatus have been reported to contain phenolic substances with antioxidant activity [18]. While fruits have been the subject of various studies, there is scarce information on the chemical composition of the remaining tree parts, e.g., leaves, wood, and bark [18]. The wood has a semi-ring-porous structure with an average vessel diameter ranging between 15 and 65 μm and an average vessel element length of 640 μm [19]. To our understanding, no previous report has been published on the characteristics of the bark of E. trilobatus.

On the other hand, tree barks have an interesting chemical complexity, being rich sources of extractives and inorganic materials, and containing suberin and polyphenolic substances that are not found in woods [20]. Therefore, their fractionation and separation of potentially valuable substances require targeted structural and chemical characterization. Bark valorization is not only important for reducing forestry waste but also for achieving a circular economy, i.e., providing economic value by producing chemicals, materials, bioactive compounds, or energy [21]. In the case of E. trilobatus, given its relatively limited distribution area and vulnerable status, all contributions of potential value-added uses of bark will add to the attractiveness of the species for planting or caring for existing trees by local communities who will recognize their valorization potential. The aim of this article is to contribute to this endeavor and address the knowledge gaps for the bark of E. trilobatus by analyzing for the first time its chemical composition, morphology, extractives and thermal decomposition properties as well as ash characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

E. trilobatus trees were identified using diagnostic floristic and morphological traits described in previous publications [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,11] and bark samples were obtained from six mature trees in local forests in the Isparta and Balıkesir provinces of western Turkey (approx. 37°32′02″ N, 30°59′08″ E and 39°31′07.4″ N 27°21′40″ E) in June 2023. The sampling was done with the official permission from the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

All the sampled trees were healthy, and free from any visible disease or mechanical damage. The trees were naturally grown, solitary, and mixed with other trees such as Pinus brutia and Quercus cerris. The trees were approximately 40 years old with an average diameter at breast height (1.3 m) of approximately 30 cm (Figure 1). The bark samples were collected from the trees at approximately breast height by cutting small squares of bark (about 5 × 5 cm) with a sharp chisel and carefully removing them from the stem wood. The bark thickness was approximately 1 cm. The samples were air-dried and shipped to Lisbon and Izmir for subsequent chemical analyses at the University of Lisbon and Izmir Institute of Technology, respectively.

2.2. SEM-EDS Analysis

The microstructural features of Eriolobus trilobatus bark were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples were affixed to aluminum stubs and coated with a Au/Pd film in a Quorum Q150T ES sputter coater (Laughton, UK). SEM imaging was conducted on a Hitachi S-2400 microscope (Hitachinaka, Ibaraki, Japan) operated at 20 kV and equipped with a silicon drift detector (SDD) for energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Hitachinaka, Ibaraki, Japan). Image acquisition and EDS spectral analysis were performed using Bruker Quantax Esprit 1.9 software (Berlin, Germany).

2.3. Wet Chemical and Phenolic Analyses

The air-dried E. trilobatus bark samples were ground and sieved, and the fraction with 250–420 μm average particle size was kept for subsequent analyses. The samples were dried with a two-step drying program first for 16 h at 60 °C followed by 2 h drying at 100 °C. The ash (inorganic) content of E. trilobatus bark was determined by oxidative heating the bark samples at 600 °C during 16 h.

The extractive content of the bark samples was quantified by three Soxhlet extractions carried out in series, following the TAPPI standards (T204 om-88 [22] and T207 om-93 [23]), using methylene chloride (CH2Cl2), ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH), and water (H2O) during 6 h, 18 h, and 18 h, respectively. Suberin content was quantified on the extractive-free samples by a methanolysis process. A 1.5 g sample was refluxed in 250 mL of 3% NaOCH3 in methanol for 3 h, and following filtration, the solid residue was refluxed again with 100 mL of methanol for 15 min and filtered again. Both filtrates were neutralized to pH 6 with 2 M sulfuric acid and evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator. The resulting residue was dispersed in 100 mL of water and extracted three times with 200 mL of CHCl3. The CHCl3 phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, evaporated, and the suberin content was determined gravimetrically [24].

The previously extracted and desuberinized bark materials were used to quantify the acid-insoluble and acid-soluble lignin fractions according to TAPPI T222 om-88 [25] and TAPPI UM 250 [26] standards. In brief, 3.0 mL H2SO4 (72%) was added to 0.35 g of the material, the mixture was held in a 30 °C water bath for 1 h, later diluted to a 4% H2SO4 concentration, and hydrolyzed for 1 h at 120 °C. After filtration, the acid-insoluble residual fraction termed as Klason lignin is weighed, and the acid-soluble fraction termed acid-soluble lignin is determined spectroscopically [24].

The polysaccharide content was estimated by mass difference [24]. All chemical assays were performed with at least four repetitions.

Phenolic content and DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging potential of E. trilobatus bark extracts were analyzed on extracts obtained by reacting approximately 3 g bark with 100 mL of 80% hydroethanolic solutions (80–20 vol. of ethanol and water, respectively) at 25 °C for 120 min [24].

Total phenolics were quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay. Briefly, 0.5 mL of extract was combined with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and allowed to react for 5 min. Then, 2 mL of 10% (m/v) sodium carbonate was added, and the mixture was incubated in the dark for 1 h. Absorbance at 760 nm was measured, and total phenolics were calculated from a gallic acid calibration curve and expressed as mg GAE/g of dry extract [24].

Condensed tannins were quantified following Broadhurst et al. [27] with minor modifications, using catechin as the calibration standard. Briefly, 400 µL of extract was mixed with 3 mL of 4% vanillin in methanol and 1.5 mL of concentrated HCl. After a 15-min incubation, absorbance was measured at 500 nm, and results were expressed as catechin equivalents (mg CE/g dry extract).

Flavonoids were measured following Barros et al. [28]. In brief, 0.5 mL of extract was mixed with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.15 mL of 5% NaNO2. After 6 min, 0.15 mL of 10% AlCl3 was added, followed 6 min later by 2 mL of 4% NaOH, and the volume was brought to 5 mL with distilled water. After 15 min of reaction, absorbance was recorded at 510 nm (Biochrom Libra S4). Results were expressed as catechin equivalents (mg CE/g dry extract and mg CE/g bark) [29].

Radical-scavenging activity was assessed using the DPPH assay. Briefly, 0.5 mL of bark extract was mixed with 4 mL of DPPH solution and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Absorbance was then measured at 517 nm, and antioxidant capacity was calculated from a Trolox calibration curve (20–100 mg/L), with results expressed as Trolox equivalents (mg TE/g dry extract) [30].

2.4. FT-IR Analysis

Previously dried (1 h-100 °C) powdered samples (180–250 μm) of E. trilobatus bark were analyzed with a Perkin Elmer FTIR-ATR spectrometer (Rodgau, Germany) and the transmittance spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 8 cm−1.

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Approximately 5 mg of E. trilobatus bark samples were analyzed with a TA Instruments SDT 2960 simultaneous DSC-TGA analyzer (New Castle, DE, USA) under a linear 10 °C/min heating rate. Alumina pans were used, and nitrogen and airflow conditions were set to approximately 50 mL/min.

2.6. XRF Analysis

The inorganic composition of E. trilobatus bark was determined with an X-ray fluorescence analyzer (Spectro IQ II, SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Kleve, Germany). All tests were performed duplicate, and the results were given as averages.

2.7. XRD Analysis

XRD analysis was carried out using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. Scans were recorded over 5–80° (2θ) with a 0.02° step size and a 0.1°/s scan speed.

2.8. BET Analysis

The specific surface area and pore structure of the ash samples were determined by N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms using a Micromeritics Gemini V (Mikromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA) analyzer. Before the analysis, the samples (approximately 100–200 mg) were degassed under vacuum at 150 °C for 12 h to remove physisorbed water and volatile contaminants.

Adsorption–desorption isotherms were recorded over a relative pressure (P/P0) interval of 0.05–0.99. The specific surface area was determined by applying the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method to the linear portion of the adsorption branch (P/P0 = 0.05–0.30). Total pore volume was calculated from the amount of nitrogen adsorbed at a relative pressure close to unity (P/P0 approximately 0.99), assuming complete pore filling. The average pore diameter was derived using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model applied to the desorption branch of the isotherm. All measurements were performed duplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.9. Solid Fuel Properties

The higher calorific value (HCV) of the bark samples was measured using a bomb calorimeter Parr 6300 (Moline, IL, USA), in accordance with ASTM D5865-13 [31]. Approximately 0.5 and 1.0 g of oven-dried and homogenized material was pressed into a pellet and combusted at 30 bars in pure oxygen atmosphere. The temperature increase in the surrounding water jacket was used to calculate the HCV. All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and the average value was reported. The HCV was also estimated by using proximate composition for comparison [32].

Proximate analysis was performed to quantify the moisture content, volatile matter, ash content, and fixed carbon using standard procedures: Moisture was determined by drying the sample at 105 °C for 24 h (ASTM E871-82) [33]. Volatile matter was determined by heating the dried sample at 950 °C for 7 min in a covered crucible (ASTM E872-82) [34]. Ash content was obtained by combusting the sample at 575 °C for 4 h in a muffle furnace (ASTM D1102-84) [35]. Fixed carbon was determined by mass difference. All analyses were carried out in six replicates.

2.10. Ash Fusion Temperature

Ash fusion behavior was evaluated using a muffle furnace equipped with visual inspection method according to U-Therm YX-HRD 3000, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China. Ash residues obtained from the proximate analysis were shaped into pyramids using a 10% sucrose solution and heated at a controlled rate up to 1500 °C under oxidizing atmosphere. Shrinkage (ST), deformation (DT), hemispherical (HT), and flow (FT) temperatures were recorded, with observations captured via a high-temperature camera.

Ash fusion temperatures were used to examine the slagging behavior of E. trilobatus bark (ASTM D 1857) [36]. Ash fouling behavior was assessed by using ash deformation temperature as well as using total alkali content indicator.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bark Morphology

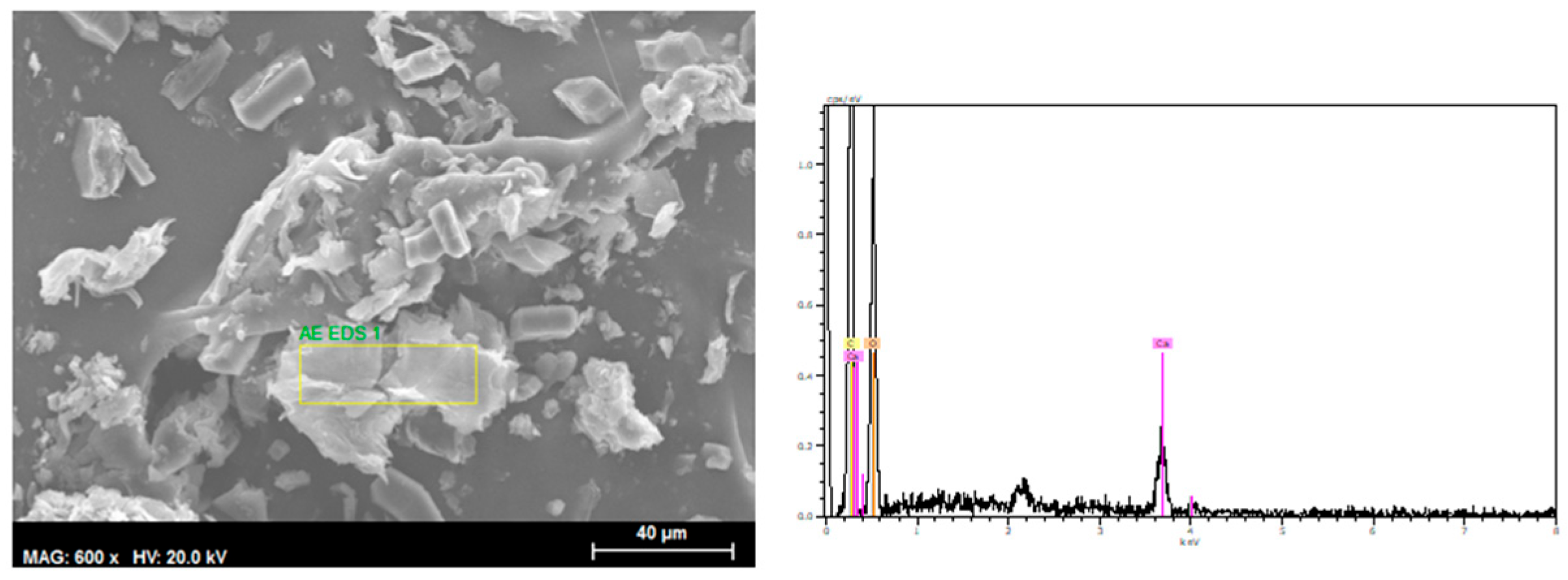

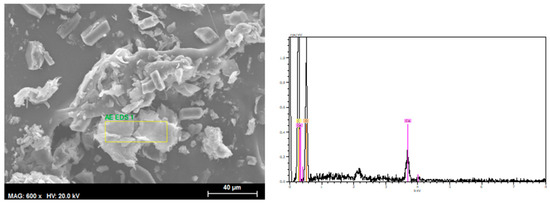

The SEM micrograph of the powdered E. trilobatus bark samples is shown in Figure 2 together with the corresponding EDS spectrum at 600X magnification. The particle surface is heterogeneous arising from fragmented cells and cell wall fractions and characterized by the presence of calcium oxalate crystal structures with calcium dominating the EDS spectra. This morphological feature of E. trilobatus bark is quite similar to other barks including Quercus robur, Ulmus glabra, Populus tremula, and Betula pendula [37]. In fact, calcium oxalates are present in different tissues of more than 215 plant families in different shapes such as styloids, raphides, prismatics, and druses [38]. The function of these crystals possibly include calcium regulation, plant protection, and metal detoxification [39].

Figure 2.

Morphology (left) and SEM-EDS spectra (right) of Eriolobus trilobatus powedered bark samples.

The shape of calcium oxalate crystals is species-specific and may differentiate plant species [39]. In E. trilobatus the calcium oxalate crystals are predominantly prismatic (Figure 2), which is comparable to those in teak bark [40].

The occurrence of calcium oxalate in the bark has direct implications for downstream utilization in thermochemical processes since calcium oxalate decomposes upon heating to yield first CaCO3 and later CaO. This transformation possibly provides an in situ source of catalytically active CaO during pyrolysis and gasification processes [41].

Such behavior has been reported to enhance tar cracking in steam gasification [42] and to impart basic catalytic activity in transesterification for biodiesel production [43]. Thus, the intrinsic calcium content of this biomass can be viewed as a natural catalytic precursor for pyrolysis and gasification systems.

3.2. Chemical Composition and Extractive Properties

The chemical composition of E. trilobatus bark is shown in Table 1. Bark contains an elevated amount of ash (13.3%), a moderate to high amount of extractives (15%) which are mainly polar (approximately 83% of total extractives) as well as low contents of lignin (22%), and an estimated significant amount of polysaccharides (45.7%). This chemical profile is quite similar to that of other barks especially of oak barks which have high inorganic content, moderate polysaccharide content, and an extractive composition of mainly polar compounds [44]. E. trilobatus bark also contains a comparatively high amount of suberin (4%) considering that it belongs to non-cork rich barks.

Table 1.

Wet chemical composition of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

The phenolic composition of E. trilobatus bark extracts is summarized in Table 2. When expressed on an extract basis, the composition varied with the extraction yield: at 12.51% yield, the extract contained 208.5 mg/g extract phenolics, 84.6 mg/g extract flavonoids, and 152.4 mg/g extract condensed tannins while at 8.0% yield, the values increased to 326.5 mg/g extract phenolics, 132.3 mg/g extract flavonoids, and 238.3 mg/g extract condensed tannins. On a solvent concentration basis, the extracts contained on average 782.9 mg/L GAE of total phenolics, 317.4 mg/L GAE of flavonoids, and 572 mg/L EAG of condensed tannins. When calculated to bark mass, the extracts contained on average 26.1 mg/g bark phenolics, 10.6 mg/g bark flavonoids, and 19.1 mg/g bark condensed tannins These values indicate that E. trilobatus bark contains moderate amount of phenolics when compared with oak barks such as Quercus cerris, Q. rotundifolia, and Q. suber [24,45,46].

Table 2.

Phenolic composition and DPPH radical-scavenging properties of Eriolobus trilobatus bark extracts.

The radical-scavenging potential, measured by DPPH method, followed a similar pattern with values between 168 and 252 mg TE/g extract depending on total extract yield with an average 20.1 mg TE/g bark. This result shows that E. trilobatus bark extracts have low to moderate radical scavenging potential [24,45,46].

The ethanol and water-soluble fractions of bark extracts are known to be rich in phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins, which explains why the extracts contained up to 26.1 mg/g bark of total phenolics, 10.6 mg/g bark of flavonoids and 19.1 mg/g bark of condensed tannins. The relatively low content of non-polar extractives (2.5%) is consistent with the fact that phenolic compounds dominate over lipophilic compounds such as fatty acids and terpenoids in this bark.

3.3. Functional Group Characterization

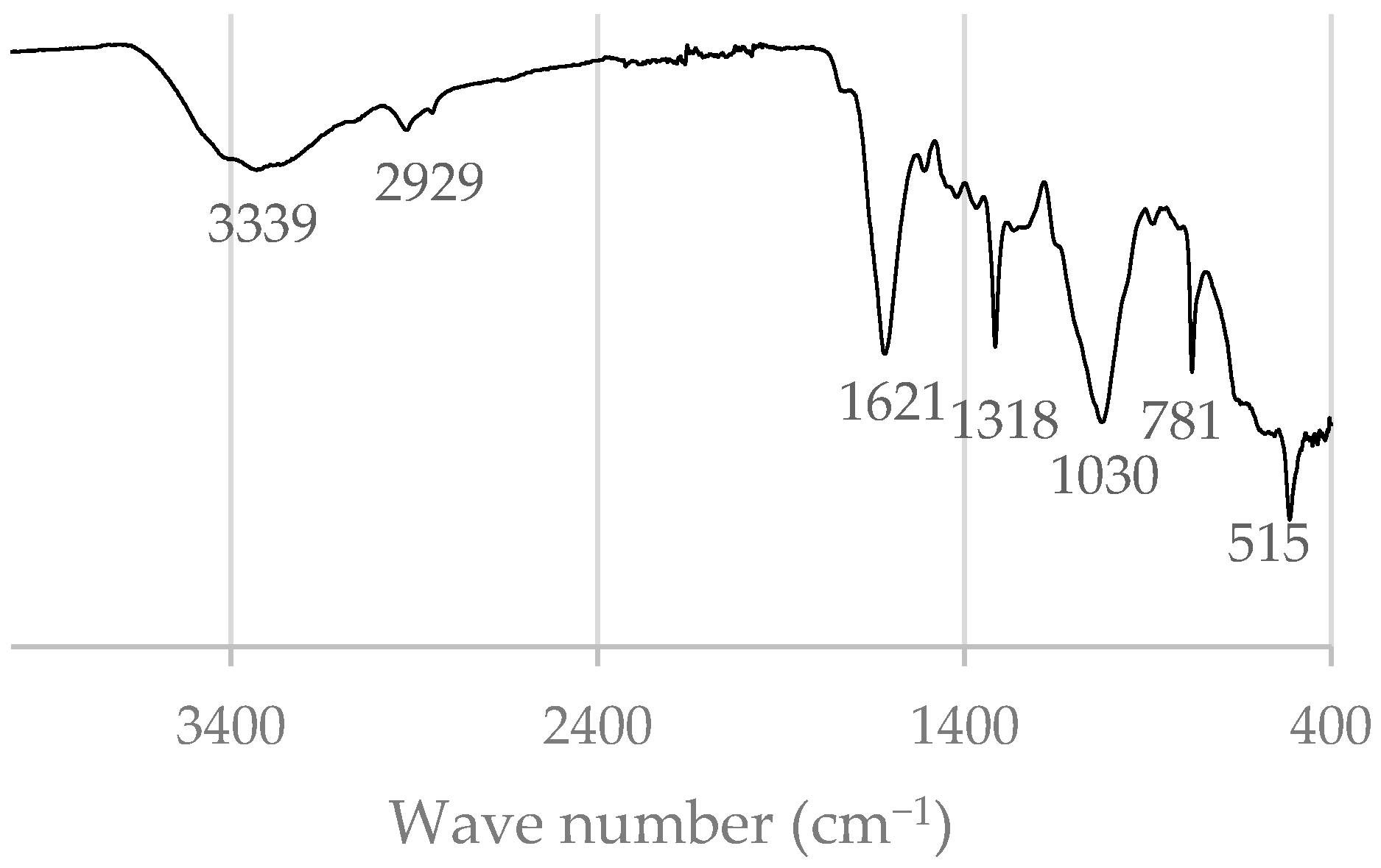

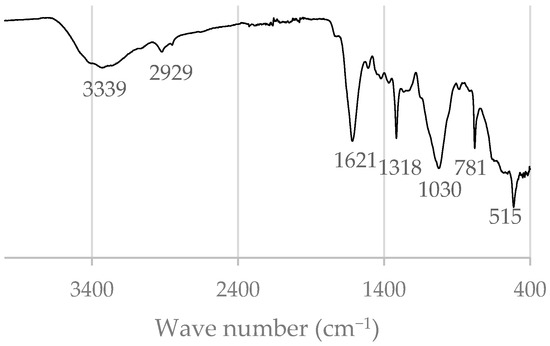

The FTIR spectrum of E. trilobatus bark (Figure 3) confirms the coexistence of organic and inorganic constituents within the material. The strong absorption bands at 1621, 1318, 781, and 515 cm−1 are characteristic of C–O stretching vibrations in calcium oxalate, corroborating the SEM–EDS evidence of Ca-rich inclusions and the high ash content determined by wet chemical analysis [47]. These features support the interpretation that calcium oxalate crystals represent a major inorganic component naturally embedded in the bark tissue. A broad absorption band is observed with a maximum at 3339 cm−1, which is assigned to O-H stretching in cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin and phenolic extractives. A weak band at 2929 cm−1 and a small peak at 2854 cm−1 correspond to asymmetrical and symmetrical CH2 stretching in aliphatic long-chain groups of extractives and suberin that are present with only small contents (4.0% suberin and 2.5% DCM extractives, Table 1). Additionally, the very small peak at 1730 cm−1 corresponds to absorption of C=O ester groups that are characteristic of suberin [47]. The broad band observed with a maximum at 1030 cm−1 is associated with C-O stretching in cellulose and hemicelluloses, reflecting the significant polysaccharide fraction (45.7% dry bark, Table 1). The absorption of C-C stretch in aromatic rings present in lignin is represented by small and undefined peaks at 1510 cm−1, 1607 cm−1 and 1420 cm−1, as well as at 1461 cm−1 (methoxy group).

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectrum of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

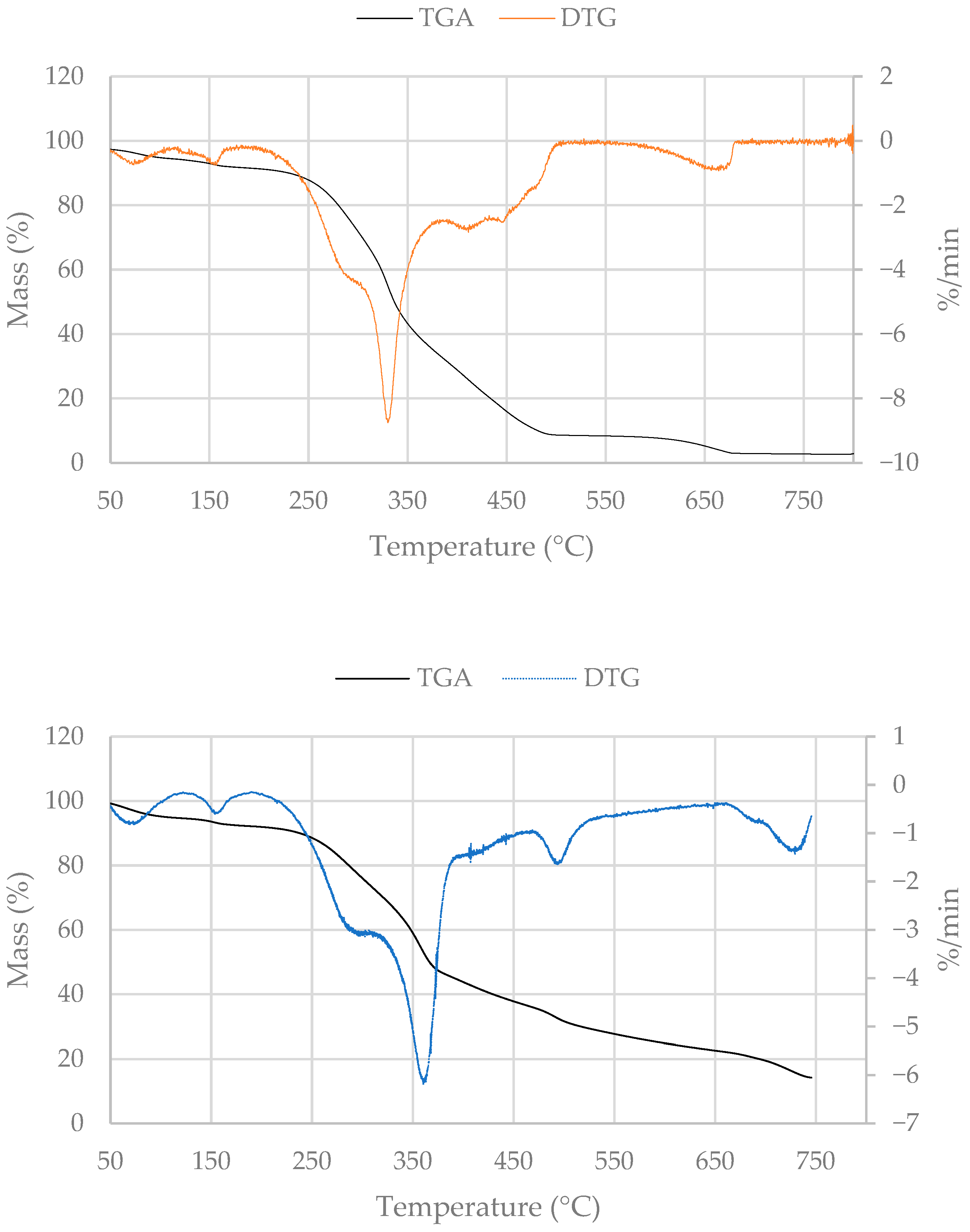

3.4. Combustion and Pyrolysis Behaviors

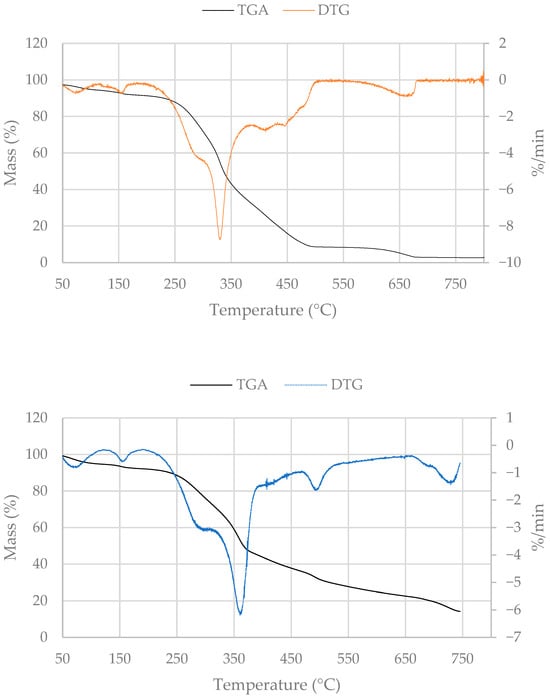

The thermal behavior of E. trilobatus bark under oxidative (air) and inert (N2) atmospheres is shown in Figure 4. In both conditions, decomposition occurs in four main stages, although the degradation pathways and residual masses differ according to the atmosphere. The first stage, up to 310–320 °C, is associated with the release of moisture and volatile extractives, followed by the decomposition of hemicelluloses and part of the amorphous lignin fraction. A shoulder around 300 °C is attributed to extractives and hemicellulose degradation, consistent with the high extractives and polysaccharide contents of the bark. The second stage, between 330 and 360 °C, corresponds to the main mass-loss event and is assigned to cellulose depolymerization. In air, this peak occurs slightly earlier and with higher intensity due to oxidative reactions that accelerate cellulose decomposition, while under N2 it is broader and shifts to higher temperatures, reflecting purely pyrolytic degradation. The third stage, extending beyond 380 °C, represents the slow decomposition of lignin and suberin, together with secondary reactions of char. In air, the residual char is rapidly oxidized, and the final residue corresponds closely to the inorganic ash fraction determined by chemical analysis (13.3%, Table 1). In N2, decomposition continues up to 750 °C, leaving a higher final residue consisting of fixed carbon and inorganic minerals. The fourth stage (670 °C and beyond) possibly corresponds to the thermal decomposition of inorganics. This thermal degradation pattern is consistent with pyrolysis and combustion behavior of barks such as Q. cerris and Betula pendula barks [48] and indicates a heterogeneous thermochemical decomposition behavior.

Figure 4.

Thermal decomposition of Eriolobus trilobatus bark under air flow (above) and nitrogen flow (below) conditions.

At higher temperatures, the important presence of calcium oxalate, as confirmed by FTIR and SEM–EDS, governs the inorganic transformations. Decomposition of Ca-oxalate to CaCO3 (400–600 °C) and subsequently to CaO (≥700 °C) possibly contributes to the high-temperature DTG tail, particularly under inert conditions.

Overall, the TGA and DTG results are consistent with the chemical composition of the bark: extractives and hemicelluloses dominate the early decomposition stage, cellulose accounts for the main degradation peak, lignin and suberin are responsible for the high-temperature degradation tail at the third stage, and Ca-rich minerals possibly control the final residue behavior. These findings highlight the complex interactions of organic and inorganic constituents in determining the thermal reactivity of E. trilobatus bark.

3.5. Fuel Characterization

The proximate composition of E. trilobatus bark (Table 3) reveals a high volatile fraction (73.5% DB), moderate fixed carbon content (12.2% DB), and a substantial ash fraction (14.3% DB). These characteristics are typical of bark-rich biomasses. Using the fixed carbon-based correlation of Demirbaş (1997) [32], the estimated higher heating value was 16.5 MJ kg−1 (dry biomass) or15.3 MJ kg−1 as-received bark (7.3% moisture).

Table 3.

Proximate analysis (%) and estimated calorific value (MJ/kg) of Eriolobus trilobatus bark (AR: As-received basis, DB: dry basis, DAF: Dry-ash-free basis).

A comparison of this proximate composition estimated calorific value with the calculated calorific value (14.9 MJ kg−1) shows a modest discrepancy of 1.6 MJ kg−1, which lies within the range of variation commonly observed when applying empirical models to heterogeneous ash-rich biomasses. The lower measured value is consistent with the high inorganic fraction of the bark, dominated by Ca-rich compounds such as calcium oxalate identified in the FTIR and SEM–EDS analyses.

These results suggest that E. trilobatus bark can be considered a moderate-quality solid biofuel, with an energy density comparable to other hardwood barks but limited by its mineral content. Pre-treatment strategies to decrease mineral content such as hot water treatment or acid washing could improve fuel quality [20], while blending with low-ash lignocellulosic residues offers a practical pathway to increase calorific performance and reduce operational risks in combustion and gasification systems.

3.6. Composition, Porosity, and Fusion Temperature of Inorganic Fraction

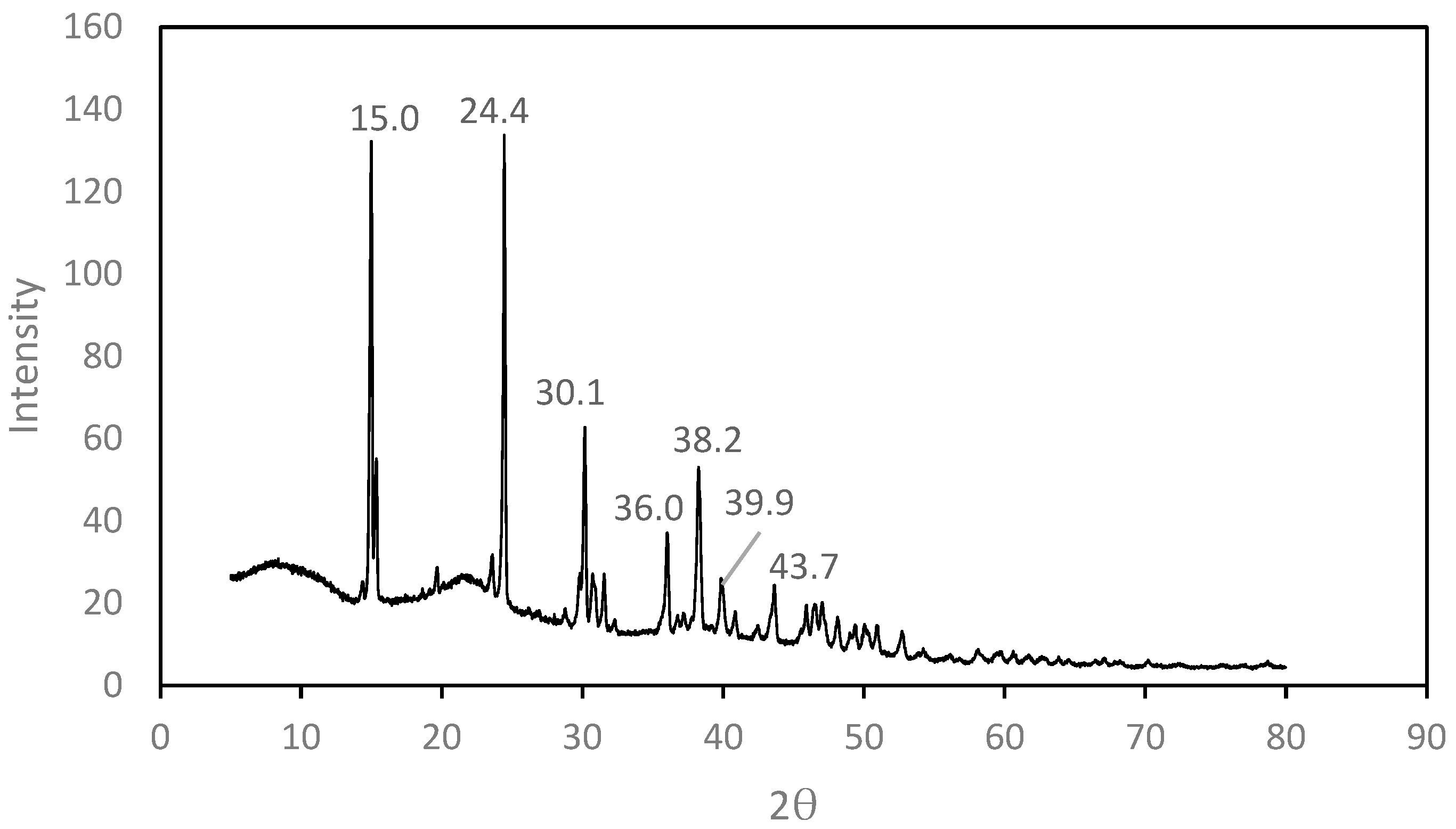

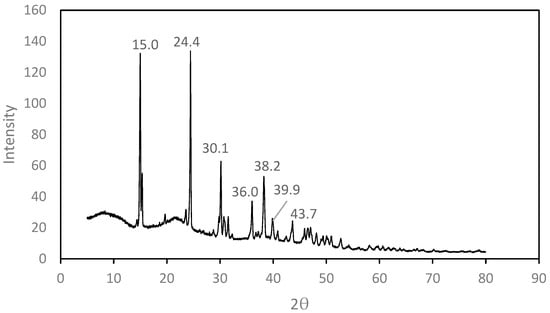

The XRD pattern of E. trilobatus bark (Figure 5) displays a mixture of crystalline and amorphous phases. The most intense reflections appear at 15.0° and 24.4° (2θ), which arise from cellulose I and mineral crystalline phases. The peak at 30.1° is attributed to crystalline calcium oxalate monohydrate (whewellite), a mineral phase frequently found in bark tissues. Additional peaks at 36.0°, 38.2°, 39.9°, and 43.7° suggest the presence of calcium carbonate (CaCO3, calcite) and related Ca-rich crystalline phases, which are consistent with the SEM–EDS and XRF results showing calcium as the dominant inorganic element.

Figure 5.

XRD analysis of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

Beyond these crystalline features, the XRD diffractogram shows a broad diffuse background in the range of 20–25°, corresponding to the amorphous components of lignin and hemicelluloses. This halo reflects the disordered structure of the non-cellulosic polysaccharides and phenolic polymers in the bark.

Overall, the XRD results indicate that E. trilobatus bark is a cellulose-rich, Ca-dominated biocomposite material, with calcium oxalate and carbonate phases embedded in an predominantly amorphous lignocellulosic matrix. These findings are in line with the chemical composition analysis (Table 1), which identified high levels of Ca and polysaccharides. The presence of Ca-based crystalline phases is particularly significant, as they can act as precursors to catalytically active CaO upon thermal decomposition, thereby influencing both the ash behavior and bark reactivity during thermochemical conversion.

The XRF results reveal that the mineral fraction of E. trilobatus bark is dominated by calcium compounds, with CaO representing more than 93 wt.% of the total oxides (Table 4). This high calcium content indicates that the bark has a strong calcareous character, which is consistent with its potential role in enhancing ash melting behavior and reducing slagging tendencies during thermochemical conversion.

Table 4.

Mineral composition of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

In addition to calcium, the bark contains moderate amounts of magnesium oxide (2.34 wt.%) and potassium oxide (1.43 wt.%), both of which are common alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) in biomass ashes. While these elements can contribute to fouling and low temperature melting eutectics, their proportions are relatively minor compared to the overwhelming CaO fraction, suggesting that their effect on lowering ash fusion temperatures may be limited.

Other oxides, such as SiO2 (0.51 wt.%), Al2O3 (0.23 wt.%), and Fe2O3 (0.20 wt.%), are present only in trace amounts. This low abundance of silica, alumina, and iron is favorable, since these oxides often interact with alkalis to form low-melting silicates that promote slagging in combustion and gasification systems. Phosphorus (0.41 wt.% as P2O5) and sulfur (1.27 wt.% as SO3) are also detected at low levels, implying a modest risk of forming condensed phosphates or sulfates that could influence ash deposition behavior.

Overall, the results highlight that E. trilobatus bark has a CaO-dominated inorganic composition, which points to high ash fusion temperatures and relatively low slagging and fouling risks. This mineralogical profile is advantageous for thermochemical applications such as combustion, pyrolysis, and gasification, while also suggesting potential catalytic roles of calcium oxides in secondary char and tar conversion reactions.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis revealed that the E. trilobatus bark-derived ash has a BET surface area of 12.5 m2/g, a Langmuir surface area of 21.1 m2/g, and a single-point surface area of 11.6 m2/g at p/p° = 0.13. The total pore volume was measured as 0.0066 cm3/g, with an average pore diameter of 21.1 Å (2.1 nm), classifying the material as mesoporous according to IUPAC guidelines. Although the overall surface area is modest compared to engineered porous materials such as activated carbons or zeolites, the presence of mesopores ensures accessibility for reactant molecules in catalytic processes [49].

Combined with the CaO-rich mineral composition (as revealed by XRF), this textural profile provides the basis for significant catalytic functionality. In the context of biomass gasification, CaO-based minerals such as dolomite or CaO-based wastes such as waste eggshells, supported within a mesoporous matrix can promote tar cracking by facilitating secondary reactions of heavy hydrocarbons, reducing tar load in syngas, increasing the hydrogen concentration in syngas, and enhancing gas quality [49,50,51,52]. The modest surface area of the ash possibly ensures sufficient active sites while preventing excessive carbon deposition that often deactivates highly porous catalysts.

In biodiesel production, the alkaline character of CaO within the ash material can catalyze the transesterification of triglycerides into fatty acid methyl esters [53]. CaO has low methanol solubility, high catalytic activity, and perhaps most importantly it has low cost [54,55]. Although the pore volume of the ash is limited, the mesoporous structure (2.1 nm) is adequate for accommodating triglyceride molecules and facilitating their interaction with surface-active CaO sites, making the material a potential low-cost, biomass-derived heterogeneous catalyst [56]. Furthermore, for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) applications, CaO-rich mesoporous catalysts can play a role in upgrading bio-oils and promoting deoxygenation, cracking, and reforming reactions necessary for producing hydrocarbon fuels with jet-fuel characteristics [57]. Therefore, while the E. trilobatus bark ash shows only moderate surface area and pore volume, its CaO-dominated composition combined with mesoporosity offers catalytic potential for tar cracking in gasification, biodiesel transesterification, and SAF upgrading, making it an attractive low-cost bio-derived catalyst.

Ash composition is also a key parameter in combustion systems. Combustion of biomass is accompanied by specific operational challenges. Unlike coal, biomass combustion can lead to operational issues such as slagging and fouling, primarily due to its mineral composition, which can lower furnace operating temperatures [58,59].

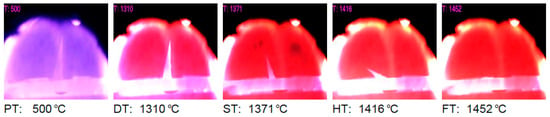

The ash fusion temperature (AFT) defines the temperature range over which the inorganic fraction of the fuel undergoes progressive transformations, beginning with deformation and softening, followed by hemispherical shaping, and ultimately melting into a liquid slag (ASTM D1857) [36]. The characteristic ash fusion temperatures of E. trilobatus bark are summarized in Table 5 and illustrated in Figure 6.

Table 5.

Ash melting temperatures of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

Figure 6.

Visualization of ash melting behavior of Eriolobus trilobatus bark.

These results indicate that E. trilobatus ash exhibits excellent thermal stability with flow temperature of 1416 °C, which is substantially higher than that of coal (1213 °C) [60]. Slagging is therefore unlikely during biomass combustion or coal-biomass co combustion where slag formation usually occurs below 1200 °C. The fouling risk is also moderate to low as reflected by the ash deformation temperature of 1371 °C.

These findings are consistent with earlier studies reporting that CaO based ashes have high melting points [61,62]. The low concentrations of iron, potassium, silicon, and sulfur in the bark reduce the likelihood of forming low-melting eutectic phases that could depress ash melting temperatures.

Despite the ash fusion temperature which indicates a very low slagging and fouling risk, the chemical composition of ashes indicates a certain fouling risk because the total alkali content (Na2O + K2O) of 1.48% is significant.

3.7. Environmental Implications of Bark Processing

The valorization of tree barks offers important environmental opportunities through utilization of bark residues for energy and material applications, thereby contributing to tree species conservation by creating added value to waste biomass streams. The complex chemical composition of bark, comprising lignin, suberin, and extractives along with calcium-rich inorganic phases, enables diverse applications that support sustainable resource use.

Pyrolysis of bark into biochar produces a porous, carbonaceous material that improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient leaching, while contributing to long-term carbon sequestration [63,64]. In parallel, bark ash enriched in CaO and alkaline oxides can serve as a natural liming agent to neutralize acidic soils, simultaneously supplying essential nutrients such as Ca, Mg, and K to support soil fertility and crop productivity [65].

Bark and its derivatives also have ecological and esthetic value in landscape management. Bark-derived biochars and ashes can be incorporated into urban green-infrastructure (e.g., green roofs) [66] to enhance pollutant immobilization/removal, improve stormwater retention, and support urban biodiversity. Additionally, it can be used in urban landscape areas to reduce soil moisture loss through mulching, thereby supporting the adaptation of the landscape to drought during climate change processes. From a sustainability perspective, bark valorization provides a dual benefit by converting lignocellulosic waste into useful products and by reinforcing ecosystem functions, renewable energy generation, and responsible land management.

4. Conclusions

This study presents the first comprehensive characterization of Eriolobus trilobatus bark from Turkey including the chemical composition, extractive profile, fuel properties, and ash characteristics. E. trilobatus bark contains 13% ash, dominated by calcium oxalate, and 15% extractives rich in polar compounds. Thermogravimetric analysis revealed four distinct stages of thermal decomposition. The bark shows moderate fuel quality with 14.9 MJ/kg HCV, the ash is mesoporous and predominantly composed of CaO, indicating potential for catalytic applications in gasification and biodiesel production. The ash has high fusion temperature (1452 °C) thereby with a very low slagging risk in combustion.

This study also highlights the broader significance of bark valorization. By demonstrating the potential of E. trilobatus bark for extraction of antioxidant compounds, energy recovery as well as soil or landscape applications, this study adds value to an underutilized forestry residue. Such valorization may stimulate interest in planting or maintaining this lesser-known and threatened tree species. Such an approach may be used as a reference for other species in which bark data are not available.

Our results also provide a foundational reference for future research on E. trilobatus and other Rosaceae taxa. Further work is needed namely to (i) investigate the variability of bark properties across different environmental conditions, (ii) evaluate the catalytic performance of the CaO-rich bark ash in gasification and biodiesel production, and (iii) explore integrated biorefinery pathways that could support conservation and sustainable valorization of this species from plantations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.Ș., C.Y. and H.P.; methodology, U.Ș., M.G., I.M., G.K. and Ş.A.; formal analysis, B.B., Ş.A., C.V., B.Ş. and I.M.; investigation, U.Ș., B.B., C.V., B.Ş. and Ş.A.; resources, C.Y. and U.Ș.; writing—original draft preparation, U.Ș.; writing—review and editing, U.Ș., C.Y., Ş.A., G.K., I.M., C.V., B.Ş. and H.P.; visualization, U.Ș. and H.P.; supervision, H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Joaquina Silva and Isabel Nogueirafrom University of Lisbon for their kind help in instrumental analysis. The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of Integrated Research Center (TAM) of Izmir Institute of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akman, Y. Contribution a Iètude de Flore Des Montagnes de IÀmanus. I–III. Commun. Fac. Sci. Univ. Ank. Ser. C Biol. 1973, 17, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browicz, K. Distribution of Woody Rosaceae in W. Asia III; Polska Akademia Nauk Arboretum Kornickie: Kórnik, Poland, 1969; Volume XIV. [Google Scholar]

- Boratyński, A.; Browicz, K.; Zieliński, J. Contribution to the Woody Flora of Greece. Arbor. Kórnickie 1983, 28, 7–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tashev, A.; Petkova, K. Fruit and Seed Morphological Peculiarities of the Critically Threatened Eriolobus trilobatus (Rosaceae). In Plant, Fungal and Habitat Diversity Investigation and Conservation, Proceedings of the IV Balkan Botanical Congress, Sofia, Bulgaria, 20–26 June 2006; Institute of Botany, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria; p. 55.

- Davis, P.H. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands; Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1972; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Korakis, G.; Poirazidis, K.; Papamattheakis, N.; Papageorgiou, A. New Localities of the Vulnerable Species Eriolobus trilobatus (Rosaceae) in Northeastern Greece. In Plant, Fungal and Habitat Diversity Investigation and Conservation, Proceedings of the IV Balkan Botanical Congress, Sofia, Bulgaria, 20–26 June 2006; Institute of Botany, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria; p. 422.

- Yılmaz, H.; Tuttu, G. Flora of Çamucu Forest Enterprice Area (Balya, Balıkesir/Turkey). Biol. Divers. Conserv. 2016, 9, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Demircan, H.; Sarioğlu, K.; Sağdiç, O.; Özkan, K.; Kayacan, S.; Us, A.A.; Oral, R.A. Deer Apple (Malus trilobata) Fruit Grown in the Mediterranean Region: Identification of Some Components and Pomological Features. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e116421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, M.J. Familiarum Naturalium Regni Vegetabilis Synopses Monographicae: Seu, Enumeratio Omium Plantarum Hucusque Detectarum Secundum Ordines Naturales, Genera et Species Digestarum, Additis Diagnosibus, Synonymis; Landes-industrie-comptoir: Weimar, Germany, 1847; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, A. Réflexions Sur l’avenir de La Culture Des Arbres Fruitiers Du Groupe Des Pomacées et Sur Les Possibilités de Leur Amélioration. J. D’agriculture Tradit. Bot. Appliquée 1952, 32, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peev, D.; Vladimirov, V.; Petrova, A.; Anchev, M.; Temnickova, D.; Denchev, C.; Ganeva, A.; Gussev, C.H. Red Data Book of the Republic of Bulgaria, Volume 1, Plants and Fungi. Available online: http://e-ecodb.bas.bg/rdb/en/vol1/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Yılmaz, M.; Parlak, S.; Kalkan, M. Güney Marmara ve Ege Bölgesindeki Geyik Elması (Malus trilobata CK Schneid.) Gen Kaynakları. Artvin Çoruh Univ. J. For. Fac. 2019, 20, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, M. Optimum Germination Temperature, Dormancy, and Viability of Stored, Non-Dormant Seeds of Malus trilobata (Poir.) CK Schneid. Seed Sci. Technol. 2008, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, N.; Kirici, S.; Özgüven, M.; Inan, M.; Kaya, D.A. An Investigation of Dye Plants and Their Colourant Substances in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 146, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladı, H.İ.; Satil, F.; Selvi, S. Wild Fruits Sold in the Public Bazaars of Edremit Gulf (Balıkesir) and Their Medicinal Uses. Biyolojik Çeşitlilik Koruma 2019, 12, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, M.; Erarslan, Z.B.; Kültür, Ş. The Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used Against Cardiovascular Diseases in Türkiye. Int. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. Res. 2023, 4, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargin, S.A. Plants Used against Obesity in Turkish Folk Medicine: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 270, 113841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınar, N.; Göktürk, R.S.; Öten, M. Some Medicinal Properties of Crab Apple (Eriolobus trilobatus) Genotypes in Antalya Province. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 13, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baas, P.; Werker, E.; Fahn, A. Some Ecological Trends in Vessel Characters. IAWA J. 1983, 4, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengel, D.; Wegener, G. Wood: Chemistry, Ultrastructure Reactions; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaijaluoto, S.; Sorsamäki, L.; Aaltonen, O.; Nakari-Setälä, T. Bark-Based Biorefinery—From Pilot Experiments to Process Model. In Proceedings of the AIChE 2010 Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 7–12 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- TAPPI T204 om-88; Solvent Extractives ofWood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1988.

- TAPPI T207 om-93; Water Solubility ofWood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1993.

- Şen, A.; Miranda, I.; Esteves, B.; Pereira, H. Chemical Characterization, Bioactive and Fuel Properties of Waste Cork and Phloem Fractions from Quercus cerris L. Bark. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 157, 112909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T222 om-88; Acid Insoluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1988.

- TAPPI UM 250; Acid-Soluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1991.

- Broadhurst, R.B.; Jones, W.T. Analysis of Condensed Tannins Using Acidified Vanillin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1978, 29, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Morais, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Strawberry-Tree, Blackthorn and Rose Fruits: Detailed Characterisation in Nutrients and Phytochemicals with Antioxidant Properties. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.; Duarte, M.P.; Maurício, E.M.; Brinco, J.; Quintela, J.C.; da Silva, M.G.; Gonçalves, M. Chemical and Functional Characterization of Extracts from Leaves and Twigs of Acacia Dealbata. Processes 2022, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, U.; Viegas, C.; Duarte, M.P.; Maurício, E.M.; Nobre, C.; Correia, R.; Pereira, H.; Gonçalves, M. Maceration of Waste Cork in Binary Hydrophilic Solvents for the Production of Functional Extracts. Environments 2023, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5865-13; Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Demirbaş, A. Calculation of Higher Heating Values of Biomass Fuels. Fuel 1997, 76, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E871-82; Standard Test Method for Moisture Analysis of Particulate Wood Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM E872-82; Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis of Particulate Wood Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D1102-84; Test Method for Ash in Wood. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- ASTM D1857; Standard Test Method for Fusibility of Coal and Coke Ash. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Trockenbrodt, M. Calcium Oxalate Crystals in the Bark of Quercus robur, Ulmus glabra, Populus tremula and Betula pendula. Ann. Bot. 1995, 75, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Fu, L. Research Progress on the Formation, Function, and Impact of Calcium Oxalate Crystals in Plants. Crystallogr. Rev. 2024, 30, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Nakata, P.A. Calcium Oxalate in Plants: Formation and Function. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, I.; Miranda, I.; Quilhó, T.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Characterisation and Fractioning of Tectona Grandis Bark in View of Its Valorisation as a Biorefinery Raw-Material. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Dai, L.; Deng, W.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cobb, K.; Chen, P. Applications of Calcium Oxide-Based Catalysts in Biomass Pyrolysis/Gasification—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, X.A.; Alarcón, N.A.; Gordon, A.L. Steam Gasification of Tars Using a CaO Catalyst. Fuel Process. Technol. 1999, 58, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, K.; Ender, L.; Barros, A.A.C. The Study of Biodiesel Production Using CaO as a Heterogeneous Catalytic Reaction. Egypt. J. Pet. 2017, 26, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.U.; Pereira, H. State-of-the-Art Char Production with a Focus on Bark Feedstocks: Processes, Design, and Applications. Processes 2021, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.; Ferreira, J.P.A.; Miranda, I.; Quilhó, T.; Pereira, H. Quercus Rotundifolia Bark as a Source of Polar Extracts: Structural and Chemical Characterization. Forests 2021, 12, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, R.; Santos, S.A.O.; Rocha, S.M.; Belhamel, K.; Silvestre, A.J.D. The Potential of Cork from Quercus suber L. Grown in Algeria as a Source of Bioactive Lipophilic and Phenolic Compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.; Marques, A.V.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Study of Thermochemical Treatments of Cork in the 150–400 °C Range Using Colour Analysis and FTIR Spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 38, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, U.; Pereira, H. Pyrolysis Behavior of Alternative Cork Species. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 4017–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mbeugang, C.F.M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S. A Review of CaO Based Catalysts for Tar Removal during Biomass Gasification. Energy 2022, 244, 123172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, M.; Makwana, J.P.; Mohanty, P.; Shah, M.; Singh, V. In Bed Catalytic Tar Reduction in the Autothermal Fluidized Bed Gasification of Rice Husk: Extraction of Silica, Energy and Cost Analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 87, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Ruiz, S.L.; Díaz-Jiménez, L.; Carlos-Hernandez, S. Catalytic Gasification as a Management Strategy for Wastes from Pecan Harvest. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Díaz, M. Eggshell Waste as Catalyst: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, S.F.; Brahma, S.; Hoque, M.; Das, B.K.; Selvaraj, M.; Brahma, S.; Basumatary, S. Advances in CaO-Based Catalysts for Sustainable Biodiesel Synthesis. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Singh, H.N. Clean Biodiesel Production Approach Using Waste Swan Eggshell Derived Heterogeneous Catalyst: An Optimization Study Employing Box-Behnken-Response Surface Methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, B.S.G.; Fioroto, P.O.; Heck, S.C.; Duarte, V.A.; Cardozo Filho, L.; Feihrmann, A.C.; Beneti, S.C. Obtention of Methyl Esters from Macauba Oil Using Egg Shell Catalyst. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 169, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Señorans, S.; Rangel-Rangel, E.; Maya, E.M.; Díaz, L. Hypercrosslinked Porous Polymer as Catalyst for Efficient Biodiesel Production. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 202, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Upgrading of Bio-Oil via Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Corncob over CaO and HZSM-5 Mixed Catalysts to Promote the Formation of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Bioresources 2019, 14, 9719–9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Baláš, M.; Lisý, M.; Lisá, H.; Milčák, P.; Elbl, P. An Overview of Slagging and Fouling Indicators and Their Applicability to Biomass Fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 217, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Meng, A.H.; Li, L.; Li, G.X. Study on Ash Fusion Temperature Using Original and Simulated Biomass Ashes. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 107, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jia, L. Experimental Study on Ash Fusion Characteristics of Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Wang, G.; Ning, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C. Effect of CaO Mineral Change on Coal Ash Melting Characteristics. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bgasheva, T.; Falyakhov, T.; Petukhov, S.; Sheindlin, M.; Vasin, A.; Vervikishko, P. Laser-pulse Melting of Calcium Oxide and Some Peculiarities of Its High-temperature Behavior. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 3461–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: An Introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Major, J.; Steiner, C.; Downie, A.; Lehmann, J. Biochar Effects on Nutrient Leaching. In Biochar for Environmental Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Saarela, I. Wood, Bark, Peat and Coal Ashes as Liming Agents and Sources of Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium and Phosphorus. Ann. Agric. Fenn. 1991, 30, 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar in Green Roofs. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).