Abstract

In this study, biopolymer chitosan–glucan from fruiting bodies of Agaricus bisporus (Cs-Agrif) was extracted and characterized as a sustainable alternative to commercial low molecular weight (LMW) chitosan obtained from crab shells (Cs-1). Cs-Agrif was prepared through an alkaline treatment process that included deproteination and deacetylation in the same step. The obtained sample was evaluated for its molecular weight, rheological behavior, degree of deacetylation (DD), crystallinity, and β-glucan and phenolic contents. Furthermore, the antioxidant properties of the prepared chitosan were determined under in vitro conditions using four spectrophotometric methods. Finally, its antimicrobial activity was tested against two pathogenic bacteria, one yeast, and mycotoxigenic fungi. Cs-Agrif had low molecular weight, of 45.70 ± 5.20 kDa, with pseudoplastic flow behavior. The degree of deacetylation was 92.7%. FT-IR and XRD analyses confirmed a chitosan-like structure and lower crystallinity in Cs-Agrif compared to pure commercial chitosan. The mushroom-derived chitosan contained β-glucans and phenols, indicating a chitosan–glucan complex. Antimicrobial assays showed low Cs-Agrif microbicidal concentrations (≤2.5 mg mL−1) for Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Candida albicans. The growth of Aspergillus flavus was significantly reduced after five days of incubation. The laboratory-prepared Cs-Agrif exhibited strong antioxidant activity at 5 mg mL−1, comparing to standards. Mushroom-derived chitosan–glucan biopolymer displays excellent physicochemical, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties, confirming its potential use in biomedicine, food, and the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries, among many others.

1. Introduction

As the second-most abundant natural biopolymer after cellulose, chitin plays a crucial structural role in a wide range of living organisms. It is present in the cell walls of various fungal groups, exoskeletons of crustaceans, mollusks, and insects [1]. Composition of chitin varies depending on the species, age, season, and environmental factors [2]. Through partial deacetylation, chitin is converted into chitosan, a cationic polymer composed of glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine [2]. It is a more versatile and functional, non-toxic, biocompatible, and biodegradable linear polysaccharide [3]. Moreover, chitosan is known for its significant potential applications in agriculture, the food and textile industries, and biomedicine and pharmacy [4,5]. Chitosan is insoluble in water but dissolves in dilute acidic solutions at a pH below its pKb value [1]. Due to the protonation of its amino groups the molecule is a positive charged [5]. The solubility of chitosan depends on several factors, including its biological origin, molecular weight (MW), and degree of deacetylation (DD). Chitin can exist in three amorphous forms—α, β and γ. The most abundant is α-chitin, which occurs in fungi, shells of crustaceans and insects. The other two forms present in squids, fungi and some insects are less common. Differences in the structure of chitin affect the solubility and application of the obtained chitosan [6]. At room temperature, chitosan is a semicrystalline polymer exhibiting polymorphism and a strong tendency to form hydrogen bonds, like many other polysaccharides [7].

Chitosan is widely recognized for its remarkable antimicrobial activity, which represents one of its most important functional characteristics. Unlike many conventional antimicrobial agents, chitosan demonstrates a broad spectrum of activity, high effectiveness against diverse microorganisms, and minimal toxicity to mammalian cells. Its activity has been confirmed against a variety of microorganisms, including algae, fungi, and bacteria. However, the effectiveness of its antimicrobial activity depends on several factors, including its MW and DD [8]. In addition, chitosan exhibits antioxidant properties due to its ability to chelate transition metal ions and thereby inhibit radical chain reactions [7]. Chitosan possesses unique structural characteristics that contribute to its antioxidant potential. Each monomeric unit contains one amino group and two hydroxyl groups located at the C-3 and C-6 positions, which can interact with free radicals, thereby exhibiting radical scavenging ability [9].

Unlike chitin from crustacean sources, fungal chitin, the second-most abundant polysaccharide in the cell wall of fungi, is not subject to seasonal or regional variability and does not require harsh acid treatments during isolation [10]. In crustaceans, chitin is complexed with other biological components such as proteins, minerals, carbohydrates, and lipids. The presence of minerals (like calcium carbonate) in crustaceans necessitates a demineralization step during chitin extraction, which is not required for fungal-derived chitin. For this, harsh acid treatment with inorganic acids is used, while alkali treatment is essential for the deacetylation of chitin, and commonly applied in the methods of isolating chitosan. For this reason, mushrooms have also attracted attention as an alternative and sustainable source of chitin and chitosan. In fungi, chitin is covalently bound to glucans [11]. The major fungal cell wall polysaccharide, linear β-1,3-glucan, provides 15 to 30% of the total cell wall polysaccharides and has a strong tendency to form crystalline microfibrils with chitin [12]. It has been reported that the chitin content in the cell wall of species from the genus Agaricus ranges from 13.3% to 43% [12]. However, because of the covalent bonding of chitin with β-glucans in the cell wall, the extraction of pure chitin from mushrooms is almost impossible [13]. Studies have demonstrated that chitosan or chitosan–glucan complexes from mushrooms promote plant growth, enhance resistance to pathogens, and increase crop yields [12]. Moreover, fungal-derived chitin and chitosan are free from heavy metals and allergens such as the muscle protein tropomyosin commonly associated with crustacean sources [14]. This makes them more suitable for use in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Fungal chitin production is more sustainable and its environmentally friendly. It allows for cultivation under controlled conditions and does not rely on seasonal seafood industry waste. The production of mushrooms generates a large amount of by-products, including stalks and low-quality class of mushrooms without commercial use, which can reach up to 20% of production. To reduce the food industry’s environmental impact, the valorization of these materials is desirable [15]. Therefore, the use of mushroom by-products for obtaining chitin and chitosan, which are not of animal origin, has multiple advantages and is economically profitable.

The significance of this research lies in the fact that the global chitosan market size is anticipated to reach around USD 101.06 billion by 2034 (https://www.precedenceresearch.com/chitosan-market, accessed on 8 November 2025). According to the data, chitosan from shrimp, known as a potential allergen and of animal origin, was the dominant type (63%) on the market in 2024. Fungal chitin and chitosan represent a more acceptable alternative for vegetarians [16]. Given the growing scientific and industrial interest in natural antioxidants, attention has also been directed toward other biologically active materials contained in medicinal mushrooms [17,18,19]. The consumption of mushrooms has increased in recent years due to their high nutritional value. Multiple health benefits are attributed to the presence of proteins, vitamins, minerals, fungal polysaccharides (particularly β-glucans), and antioxidants. Out of more than 35 commercially cultivated species, approximately 20 are produced on an industrial scale. The most widely cultivated and consumed species include the Button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus), Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp.), and Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes), while globally, around 2000 edible mushroom species have been identified [20].

One of the aims of this study was to propose an efficient method for extracting a highly deacetylated (≥90%) and low-molecular-weight (≤50 kDa) chitosan–glucan complex from mushroom fruiting bodies with superior biological activity. The extraction protocol developed here optimizes solvent concentrations, reaction times, and temperature. This eliminates the harsh acid demineralization step and shortens the chemical extraction procedure by omitting the separate NaOH-based deacetylation step commonly described in the literature. Current literature provides limited chemical characterization of mushroom-derived chitosan [1,4,12,15,20,21,22,23]. It overlooks the significance of glucans and phenolic compounds for the complex’s biological activity, despite its visible color. This study aims to fill this gap through a detailed chemical analysis, including quantification of glucans and phenols. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify total phenolics in the extracted complex. The influence of both glucans and phenols is considered when evaluating the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of the chitosan sample.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Standards

Commercial chitosans (denoted by Cs-1, Cs-2, and Cs-3), D2O (99.9 %), ferrozine (97%), 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), potassium persulfate, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), linoleic acid (≥98%), Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and standards such as vitamin C, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), gallic acid, α-tocopherol, and citric acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA). Potassium bromide (99+%, for spectroscopy, IR grade) was supplied by Acros Organics BV (Geel, Belgium). A β-glucan assay kit was purchased from Megazyme Int. (Wicklow, Ireland). Solvents such as ethanol and hydrochloric and acetic acids were provided by LGC Promochem (Wesel, Germany). All other reagents were extra pure or of analytical grade and commercially available.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Extraction of Chitosan–Glucan Complex

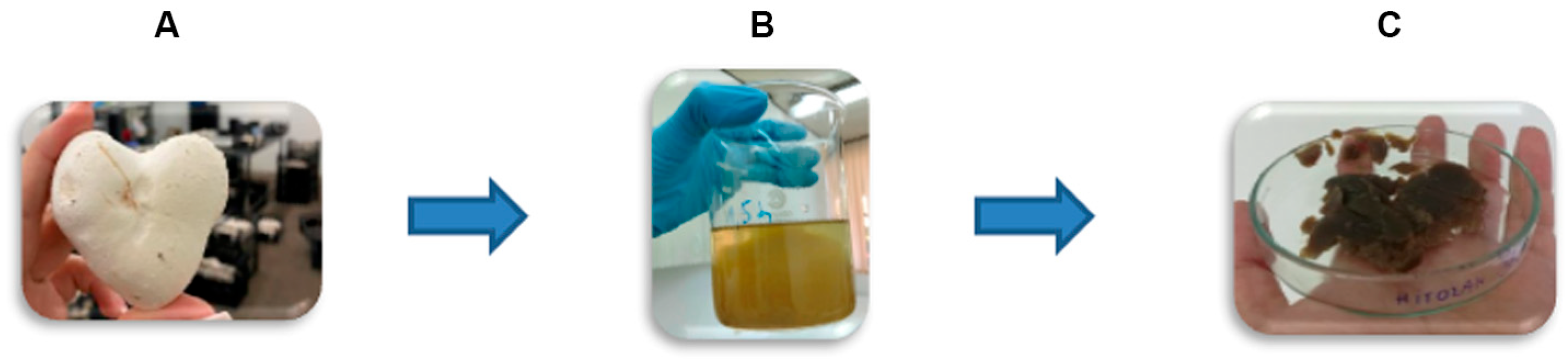

Chitosan–glucan complex (denoted by Cs-Agrif) was extracted from dried and ground fruiting bodies of cultivated Agaricus bisporus mushrooms (Delta Danube d.o.o, Kovin, Serbia) as a crude chitosan under laboratory conditions (Faculty of Agriculture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia) using the modified method of Wu [12]. In general, the extraction process consisted of three steps (Figure 1): (A) Alkaline treatment with 9 M NaOH (w:v/1:40) at 121 °C in an autoclave for 1.5 h to remove proteins, alkaline-soluble polysaccharides, and small molecules. This step also enabled sample deacetylation. The obtained alkaline-insoluble material (AIM) was centrifuged (9000 rpm, 15 min, 12 °C, Eppendorf 5804 R), then washed twice with deionized water and twice more with 96% ethanol; (B) Acid treatment of dried AIM with 5% (v/v) acetic acid (AcOH) at 120 °C for 6 h using a magnetic stirrer at 700 rpm, followed by centrifugation and neutralization as described for the AIM, to separate chitin and chitosan; (C) Precipitation of chitosan under alkaline conditions, followed by adjustment of the pH to 10 with 1 M NaOH, filtration (Whatman No. 4), washing with deionized water, and lyophilization (Christ, Alpha 1-4, LSC plus).

Figure 1.

Scheme of extraction of chitosan–glucan complex from fruiting bodies of Agaricus bisporus (Cs-Agrif): (A) Deproteination and Deacetylation with 9M NaOH (121 °C, 1.5 h); (B) Acetic acid (5%) treatment of AIM followed with chitosan precipitation at pH 10, and (C) Precipitated chitosan Cs-Agrif followed with neutralization and lyophilization.

2.2.2. Characterization of Cs-Agrif

Chemical Characterization

The contents of glucans (total and α-glucans) were determined using a yeast and mushroom β-glucan assay kit, following the instructions given by the kit producer. Additionally, the content of β-glucans was determined by subtracting the α-glucan content from the total glucan content. The total soluble phenol content was measured using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and the method proposed by Gąsecka et al. [24]. Gallic acid was used as the standard.

Rheological Characterization

Rheological characterization was performed on a Rheolab MC 120 rotary rheometer (Paar Physica, Blankenfelde-Mahlow, Germany), using a Z3 DIN coaxial cylinder (25 mm) as a measuring system, by conducting continuous (rotational) measurements [25]. The measurement procedure involved a controlled shear rate (CSR) measurement procedure, during which the shear rate was continuously changed across the measurement ranges (0–100 s−1 and 100–0 s−1) at a temperature of 20 ± 0.1 °C. The measurements were performed 24 h after the preparation of the Cs-Agrif and commercial chitosan solutions (Cs-1, Cs-2, and Cs-3). Chitosan solutions (1% w/v) were prepared by dissolving each sample in 1% (v/v) AcOH. The solutions were mixed by using a magnetic stirrer at 250 rpm until the chitosans were completely dissolved. The solutions were then stored at +4 °C overnight. Prior to further testing, the samples were equilibrated at room temperature for 1 h. For each sample, measurements were conducted in triplicate, and the obtained results represent the mean value ± standard deviation (SD). The obtained data were subsequently used to assess the influence of MW and rheological properties on the biological activity of Cs-Agrif.

Molecular Weight Determination

To determine the average MW of the chitosan, 50 mg of selected chitosan was dissolved in 50 mL of a mixture of 0.1 M AcOH and 0.2 M NaCl to give a final concentration of 0.1% (w/v). The solution was homogenized well and left overnight at room temperature, then filtered through metal sieves (Ø100 μm) to remove insoluble residuals [26]. After that, five diluted concentrations for each tested chitosan—0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, 0.08%, and 0.10% (w/v)—were prepared. The efflux times t for 10 mL of these solutions and t0 for the solvent were measured (at least 5 times) and then used to calculate the viscosity of the investigated samples. The molecular weights of the samples were estimated from the viscosity measurements, from which the intrinsic viscosity [η] was also determined. The intrinsic viscosity was obtained by extrapolating the reduced viscosity versus the concentration. Consequently, the MW of each chitosan was calculated by using Equation (1) (the Mark–Houwink equation) [27]:

where k and a are constants independent of MW over a wide range. In our case, k and a were 1.81·10−3 and 0.93, respectively, at 25 °C. The [η] values of Cs-Agrif and Cs-1 (chosen pure commercial chitosan) are presented in the Section Results and Discussion, together with the MW values of the samples (in kDa).

[η] = k·MWa,

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR analysis was performed in transmission mode over the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1, with 32 scans at a resolution of 2 cm−1, using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA, USA) for sample characterization. The samples and KBr were dried for 24 h at 50 °C in order to remove moisture, and then tablets were made in a tablet press. After the measurements were made, automatic baseline correction and atmospheric correction were applied to eliminate CO2 and H2O interference.

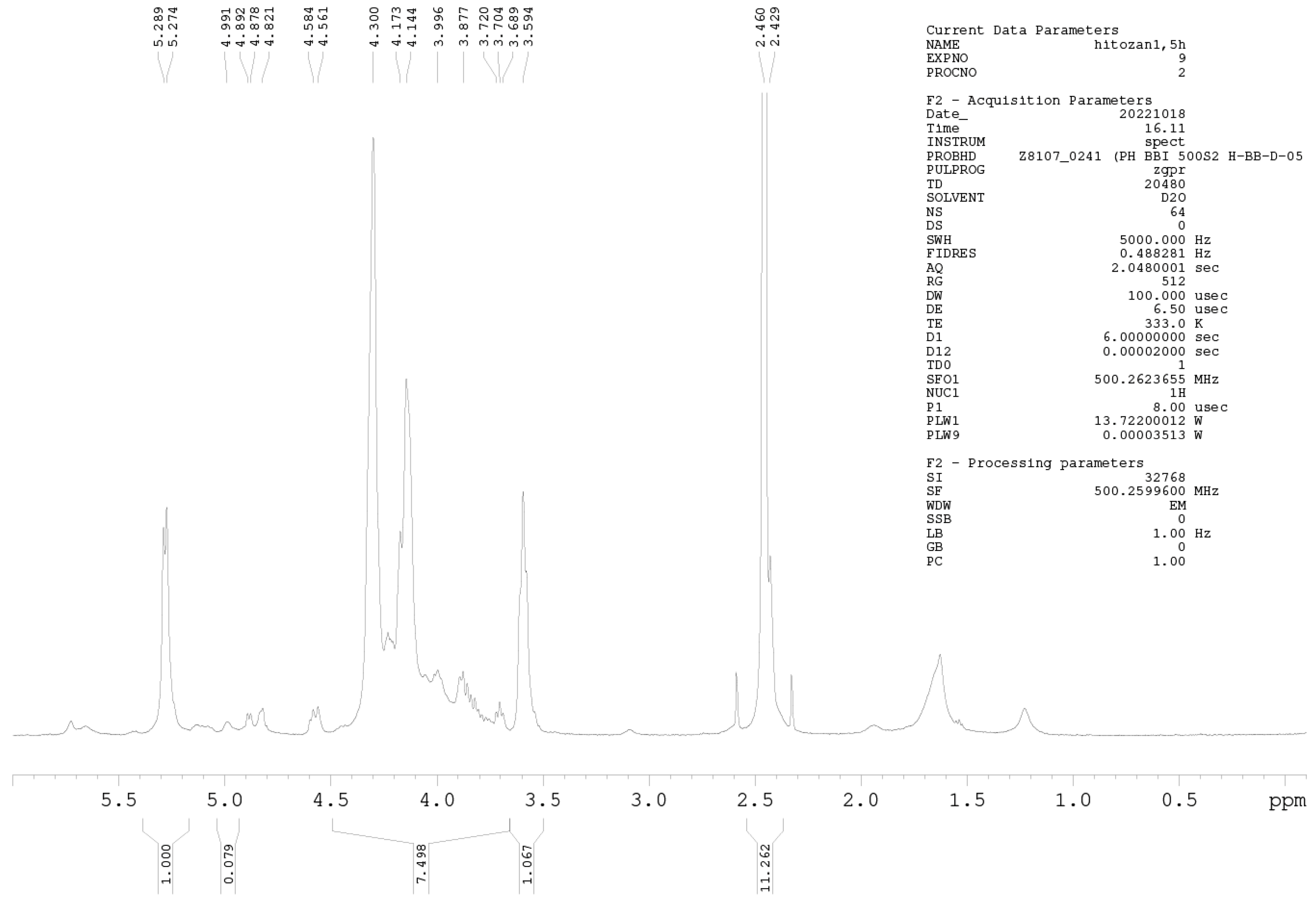

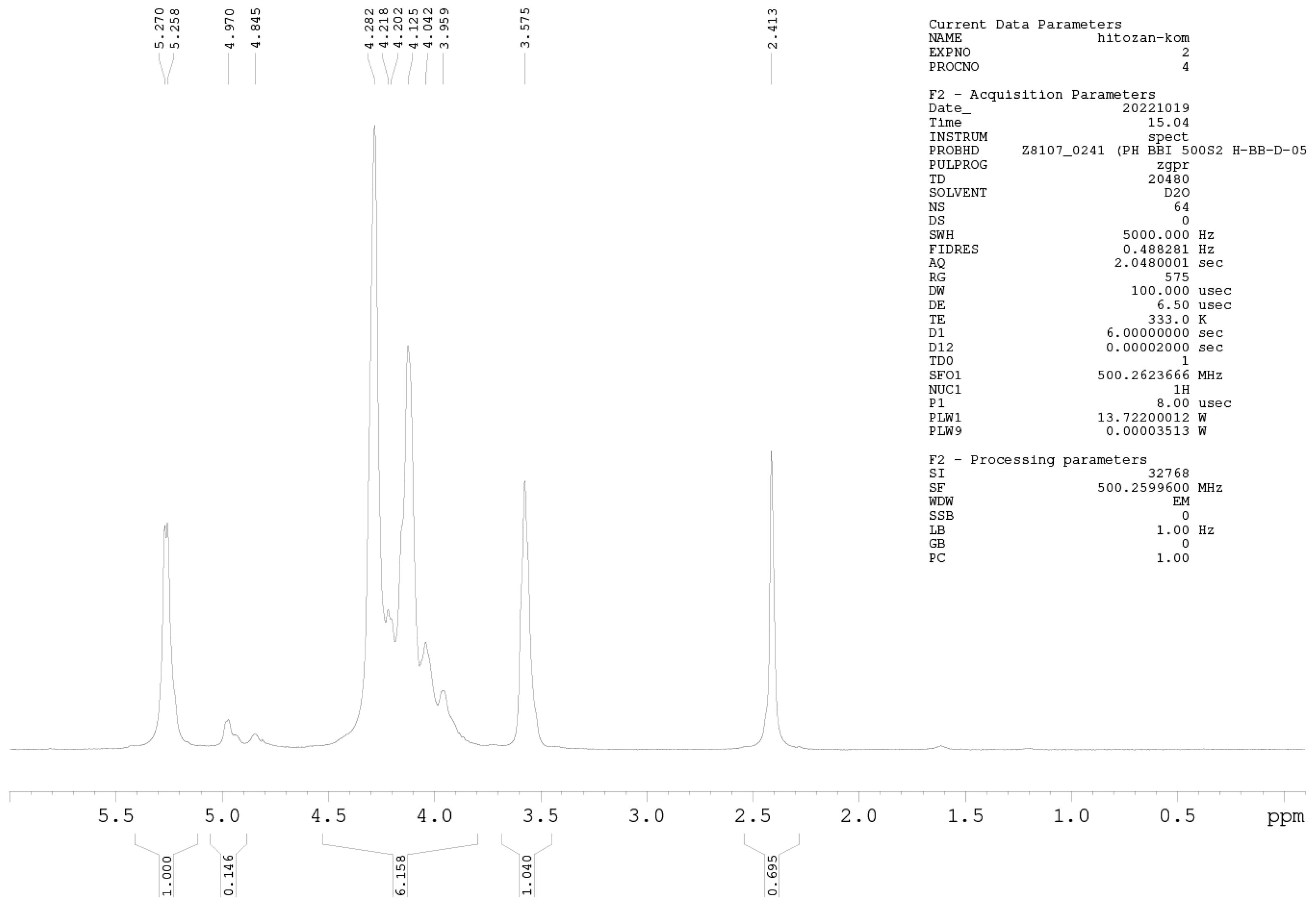

1H-NMR Spectroscopy

1H-NMR spectroscopy was further used for precise DD determination. Samples were prepared at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1 (D2O and HCl). NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AVANCE III 500 spectrometer (500.26 MHz for 1H nuclei) at 60 °C, applying the zgpr pulse sequence to suppress the water signal. All acquisition and processing parameters are presented in the Appendix A (Figure A1 and Figure A2). The DD of chitosan was calculated using Equation (2) [28]:

where IH1-GlnN denotes the integrals for H1 (GlcN), and IH1-GlnNAc denotes the integrals for H1 (GlcNAc).

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was run at room temperature using an Ultima IV Rigaku diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with CuKα1,2 radiation, utilizing a generator voltage of 40.0 kV and a generator current of 40.0 mA. A range of 5–60° for 2θ was used in continuous scan mode with a scanning step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 2°/min, using a D/TeX Ultra high-speed detector. A glass sample carrier was used for sample preparation.

2.2.3. Determination of Antimicrobial Activity

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of Cs-Agrif were evaluated. The bacterial strains used in the antibacterial activity test were Gram-positive Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29219) and Gram-negative Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). The yeast strain Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) and an isolate of the mycotoxigenic mold Aspergillus flavus (isolate 4846, Maize Institute “Zemun Polje”) were used for the antifungal activity test. The bacterial strains were grown for 24 h at 37 °C on Müeller Hinton Broth (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India), and the yeast was grown for 48 h at 30 °C on Malt Broth (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India). For the disc diffusion test, overnight cultures were applied, while the final concentration of the microbial suspensions used for the broth microdilution assay was adjusted to approximately 105–106 cfu mL−1.

For the disc diffusion test, overnight bacterial cultures and 48 h old yeast cultures were spread over Müeller Hinton/Malt Agar (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) in Petri dishes, then sterile discs for antibacterial and antifungal testing were placed on top. The tested chitosan samples (25 µL, conc. 20 mg mL−1), prepared in 0.0625% AcOH, were added to the discs. A low acid concentration was used to exclude the influence of AcOH on microbial growth. During prior research, inhibitory activity at higher concentrations was noted, with 1% (v/v) AcOH demonstrating microbicidal activity. After 24 h and 48 h of incubation, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured [29].

The standard broth microdilution method was performed [30]. The concentrations of the chitosan, prepared in 0.125% AcOH, ranged from 20 to 0.156 mg mL−1.

The inhibitory activity of the samples on A. flavus was tested according to the method described by Savić et al. [31] The chitosan samples were diluted in AcOH, suspended in melted malt agar to obtain a concentration of 20 mg mL−1, and then poured into Petri dishes. After the agars with the added chitosan samples had solidified, a piece of agar overgrown with A. flavus mycelium (5 × 5 mm) was added to the middle of each Petri dish. The growth of the mycelium was monitored for five days. The result is expressed as the percentage of inhibition of mycelial growth compared to the control sample.

2.2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Potential

Sample was prepared in 0.2 M HCl solution [32] at working concentrations of 0.625–5.000 mg mL−1. Before each analysis, the sample was intensively vortexed for 10 min. Different methods corresponding to different levels of antioxidant activity were used to measure the antioxidant properties of the tested sample in vitro. Using spectrophotometric tests, the ability to scavenge free 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radicals (DPPH•) [33] was measured at λ = 517 nm, the ability to neutralize radical cations of 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS+•) [34] was measured at λ = 734 nm, the inhibition of lipid peroxidation in the model system of linoleic acid (conjugated diene method) [35] was measured at λ = 234 nm, and the ability to chelate ferrous ions (Fe2+) [35,36] was measured at λ = 562 nm. All measurements were carried out in triplicate using a UV–VIS 1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The results are expressed as the percentage of scavenged •DPPH, the percentage of neutralized ABTS+•, the inhibition percentage of linoleic acid peroxidation, and the percentage of Fe2+ chelation. Starch, vitamin C, citric acid, α-tocopherol, EDTA, and commercial Cs-1 at concentrations of 0.625–5.000 mg mL−1 were used as standards. A solution containing all components without extract was used as a control solution.

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of differences between the control and experimental groups was determined using Student’s t-test at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed with the Statistica 12.0 software package (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). All experiments were conducted three to five times.

3. Results and Discussion

In this research, Cs-Agrif was extracted from whole fruiting bodies of industrially grown A. bisporus mushrooms through deproteination and deacetylation in alkaline solution in the same step. Unlike pure commercial chitosan from crabs, Cs-Agrif appeared dark brown, most likely due to the absence of purification of the mushroom-derived chitosan–glucan complex and the presence of phenolic compounds. A similar dark coloration was reported for chitosan isolated from Ganoderma lucidum [1]. Further purification can be achieved by refluxing the crude powder in acid [12,37]. When crude chitosan is refluxed in an acid, such as dilute hydrochloric acid, the acid dissolves some of the impurities present in the powder (proteins or mineral salts). In addition, color improvements may be obtained using established decolonization procedures [38,39]. Hydrochloric acid (HCL), commonly applied for the demineralization of mushroom biomass during chitosan extraction, has been shown to adversely affect both the degree of deacetylation (DD) and molecular weight (MW)—two parameters that are critical for the functional quality of the resulting chitin or chitosan. HCL can induce extensive hydrolysis and promote the formation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), which not only alters the physicochemical characteristics of the polymer but may also introduce undesirable environmental impacts [40]. Current literature indicates that lower MW and higher DD are generally associated with enhanced biological activity of chitosan, which is particularly relevant for its antioxidant applications [41]. However, most published protocols for extracting chitosan, or chitosan–glucan complex from mushrooms yield materials with DD values below 80% and MWs exceeding 50 kDa [1,21,23,42].

Wu [12] reported AIM yields from A. bisporus of 12.65–32.00%, expressed as a percentage of the dry weight of stalks, which is in accordance with our result (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of extracted chitosan (Cs-Agrif) and commercial chitosan (Cs-1).

According to the same author, bringing AcOH to boiling temperature also removes impurities from chitin. However, in contrast to our study, this author did not obtain chitosan through a precipitation process. In our process, the yield of precipitated Cs-Agrif was 6.52%, calculated on the basis of the dry weight of the fruiting body. The higher temperatures and longer treatments used during chitosan extraction in our research are probably the reason for this difference. Hemmami et al. [43] reported a much higher yield of chitosan from Amanita phalloides mycelial biomass (70%). However, the reported chitosan yield from G. lucidum biomass was, on average, 83.23 mg of chitosan per g of biomass (8.32%) [22], which is in accordance with our results. The content of chitosan in fungi additionally depends on the strain, growing conditions, and storage temperature [12,22].

The results presented in Table 1 show that the obtained Cs-Agrif was evidently a chitosan–glucan complex composed of 25.36% total glucans (22.97% of β-glucans) and 29.63 mg g−1 d.w. total phenols on average. The result is in consonance with the results obtained by Wu [12] from A. bisporus stipes (20.94% glucans in total). The complex obtained in this research may have strong bioactivity which could be an advantage for its application in biotechnology.

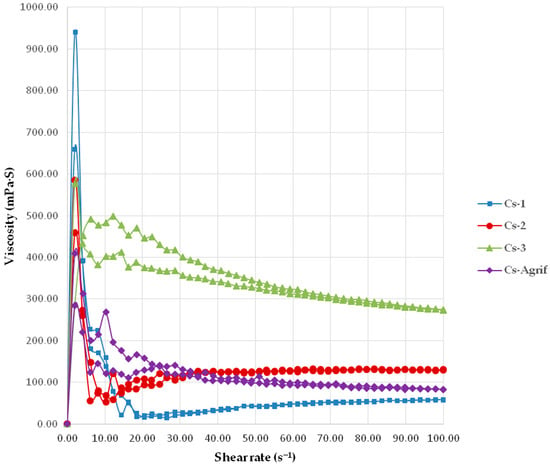

3.1. Determination of Cs-Agrif Molecular Weight and Rheological Characterization

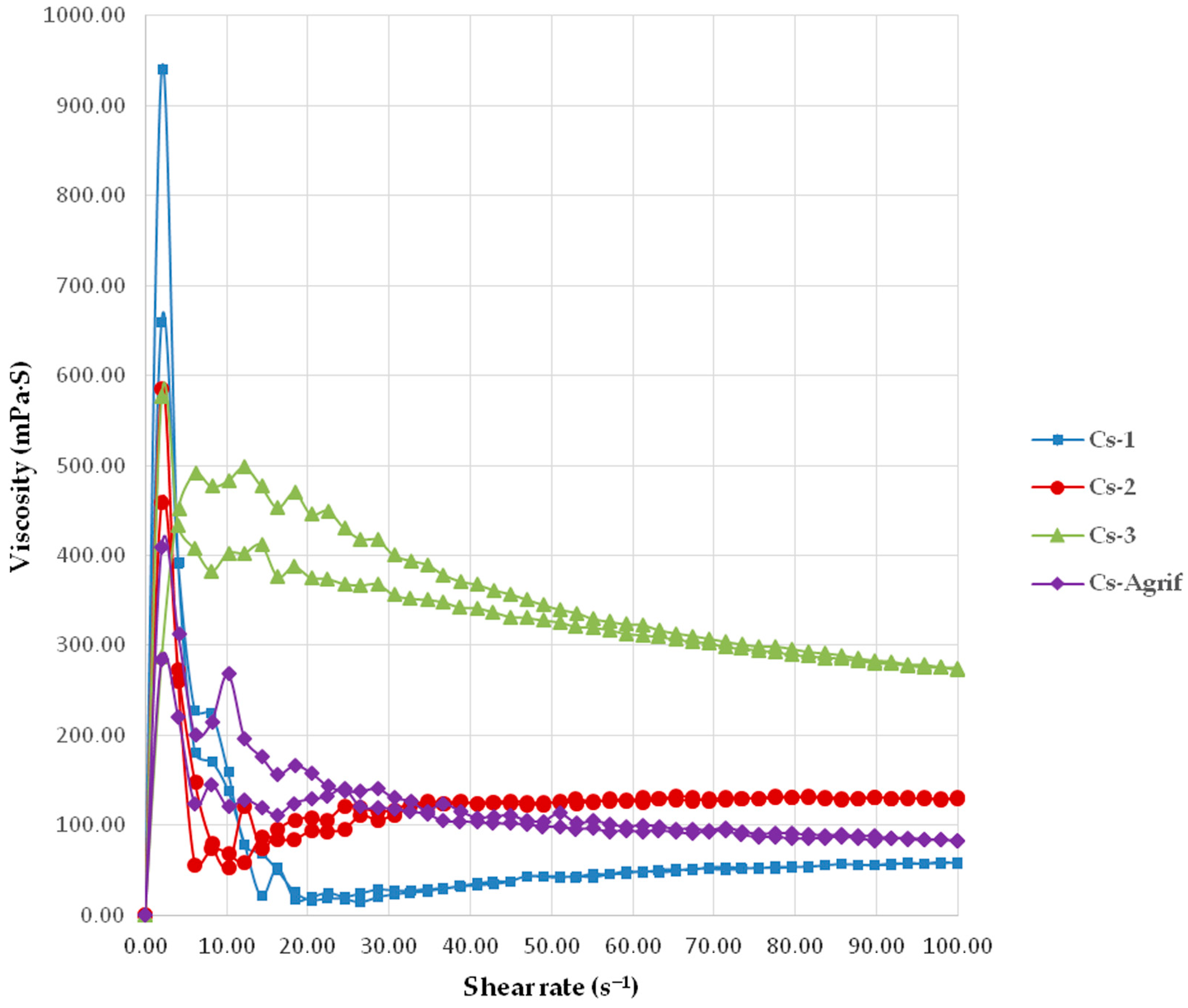

The viscosity profiles of Cs-Agrif and three commercial chitosan samples are presented in Figure 2. The minimal apparent viscosity values at 100 s−1 for Cs-3, Cs-2, Cs-1, and Cs-Agrif were 275.00 ± 4.36, 129.00 ± 3.00, 58.43 ± 2.83, and 82.97 ± 3.86 mPa.s, respectively. All examined samples demonstrated pseudoplastic behavior, which is an essential characteristic for technological and other potential applications as it provides an optimal balance between simple processing and product stability. This behavior depends on the molecular structure of the chitosan (MW, concentration, DD, pH), as well as environmental factors (temperature, solvent, presence of other substances). A decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate indicates that the material becomes “thinner” or less viscous under higher mechanical load. This shear-thinning behavior facilitates application, mixing, and pumping, since the viscosity decreases during processing [43]. Once the mechanical stress is removed, the viscosity recovers to a higher level, thereby enhancing product stability (e.g., preventing settling or phase separation). This property is particularly advantageous for pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic formulations, where it is necessary for the product to flow easily during application and to remain stable afterwards.

Figure 2.

The viscosity profiles of Cs-Agrif and commercial chitosans (mean values ± SD, n = 3); the coefficients of variation were less than 5%.

Stronger pseudoplastic behavior is typically observed in high molecular weight chitosan, as longer polymer chains promote greater intermolecular interactions and entanglements. This effect, however, was not observed in the Cs-Agrif sample. Nevertheless, the newly synthesized chitosan–glucan complex from A. bisporus had a pronounced DD of about 92.7% (the result is presented in Section 3.3). This can explain the increased pseudoplasticity, since a higher DD is known to enhance intermolecular interactions [44,45]. Intermolecular bonding can also be affected by the presence of other polymers. In the case of Cs-Agrif, the presence of β-glucans may have synergistically contributed to the observed pseudoplasticity [46]. Namely, β-glucans are known to increase the viscosity of aqueous solutions or form a gel [47,48]. Due to this property, they have been used in food and cosmetic products as viscosity-enhancing and gelling agents [49]. Therefore, it is possible that the higher viscosity of Cs-Agrif compared to Cs-1, even though the higher MW determined for the latter, could be attributed to the presence of β-glucan, which may have contributed to the higher apparent viscosity at the maximal shear rate.

Most of the biological activities (e.g., antimicrobial activity, mucoadhesion) and functional properties (viscosity, biodegradability, hydrophilicity, moisture absorption) of chitosan are strongly dependent on its MW [50]. Industrial chitosan products ranges from 100 kDa to 1200 kDa depending on the chitosan source [51]. It is reported that chitosan from fungal sources ranges from 6.4 kDa to 1400 kDa, which is an advantage of the fungal application [52]. The deacetylation process, particularly factors such as the heating time, can lower the MW of the polymer. This, in turn, enhances antimicrobial activity, since Cs with low molecular weight (LMW) can more effectively penetrate into microbial cell walls and inhibit protein synthesis [51,52].

The determined average MW of the standard samples were 347.3 ± 58.7 kDa, 445.7 ± 81.7 kDa, and 565.8 ± 85.6 kDa for Cs-1, Cs-2, and Cs-3, respectively. In contrast, the MW of Cs-Agrif was significantly lower (p ˂ 0.05) than that of the commercial Cs-1, with an average of 45.7 ± 5.2 kDa. Chitosan with MW ˂ 50 kDa is often referred to as LMW [53]. These results are consistent with previously reported data on the MW of chitosan derived from G. lucidum mushrooms [1], which ranged from 47.65 to 65.68 kDa depending on the extraction method. Wang et al. [54] also reported that fungal chitosan generally exhibits a lower MW as compared to chitosan obtained from shellfish waste. All the commercial chitosan samples in this study were extracted from shrimps, whereas Cs-Agrif was isolated from mushroom fruiting bodies.

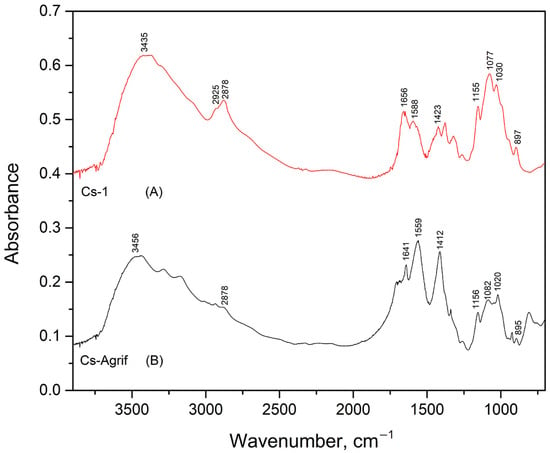

3.2. FTIR Analysis of Cs-Agrif

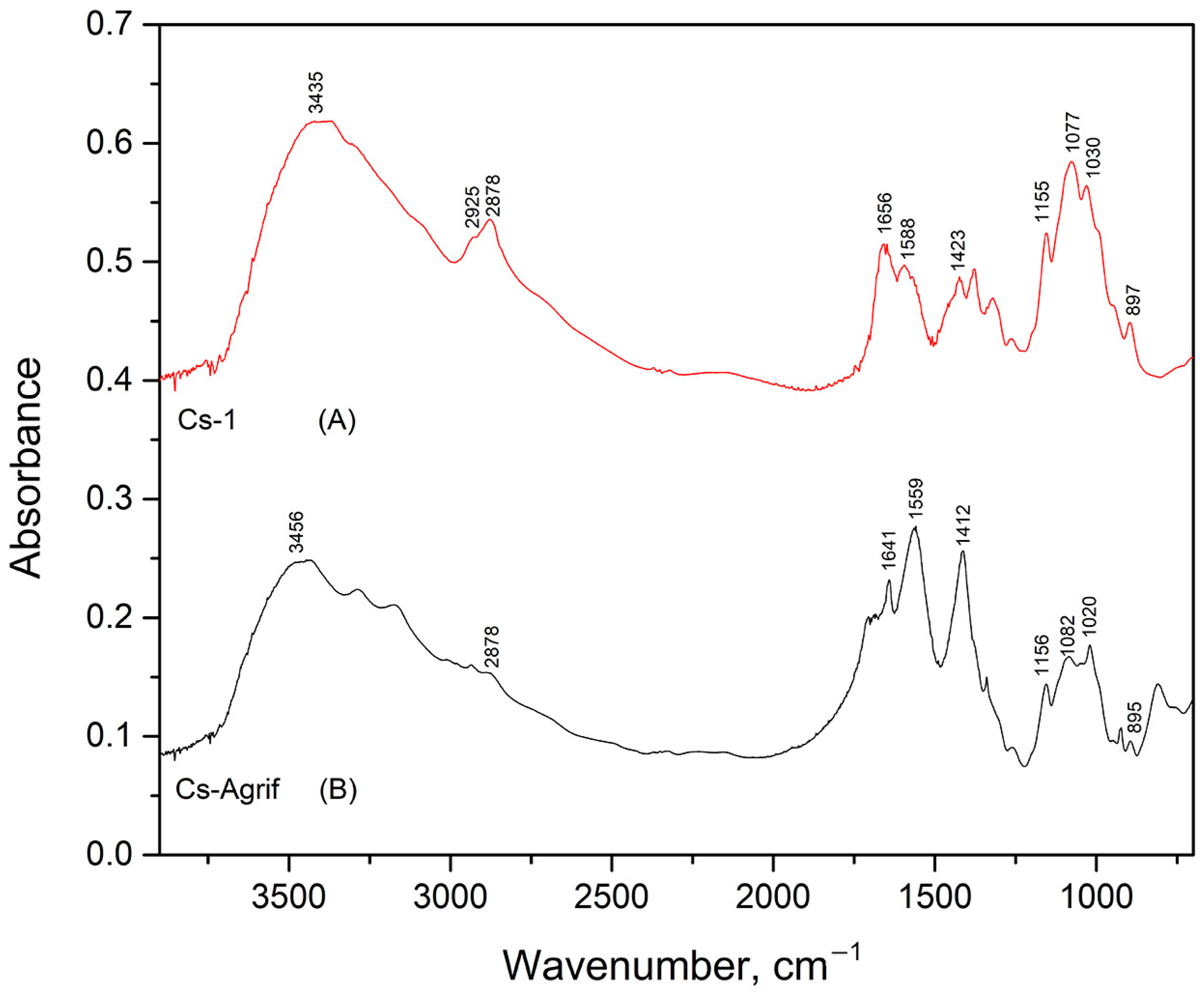

The FTIR spectra of Cs-1 and Cs-Agrif samples are given in Figure 3. Both spectra show characteristic absorption bands that are in good agreement with the data reported by Ospina et al. [22]. The presence of the typical functional groups associated with chitosan and chitosan patterns are confirmed. Chitosan is a product of chitin deacetylation, and it is a binary heteropolysaccharide composed of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose and 2-amino-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose linked by β-(1,4) glycosidic bonds [55]. The spectrum of Cs-1 exhibited a characteristic absorption band at 3435 cm−1, attributed to the –OH stretching vibrations commonly found in polysaccharides. The bands observed at 2925 cm−1 and 2878 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of C–H groups. The absorption peak at 1656 cm−1 is assigned to Amide I vibrations, indicative of C=O stretching in amide groups. The band at 1588 cm−1 is related to the bending vibrations of -NH2 groups. The peak at 1423 cm−1 corresponds to CH3 group bending vibrations, while the absorption at 1155 cm−1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching of C–O–C bridges. This is characteristic of polysaccharide structures. Peaks at 1077 cm−1 and 1030 cm−1 are assigned to C–O stretching vibrations. The band at 897 cm−1 is characteristic of anomeric CH group vibrations, confirming the presence of glycosidic linkages in the sample.

Figure 3.

Infrared absorption spectra of Cs-1 (A) and Cs-Agrif (B).

In the FTIR spectrum of the Cs-Agrif sample, the band at 3456 cm−1 is attributed to –OH stretching vibrations. The absorption at 1641 cm−1 is assigned to Amide I vibrations, confirming the presence of amide groups. The band at 1559 cm−1 corresponds to the bending vibrations of amino groups. The peak observed at 1412 cm−1 is related to CH3 bending vibrations. The asymmetric stretching of C–O–C bridges was observed at 1156 cm−1. The bands at 1082 cm−1 and 1020 cm−1 correspond to C–O stretching vibrations, though the lower wavenumber at 1020 cm−1 may suggest minor structural or purity differences compared to standard chitosan samples. The spectrum of Cs-Agrif shows a band at 895 cm−1, characteristic of anomeric CH group vibrations, confirming the presence of glycosidic linkages. The spectrum lacks clearly defined bands in the 2900 cm−1 region (C–H stretching), indicating possible variations in chemical structure or composition relative to the Cs-1 obtained from crabs.

According to Junior et al. [56], weakening of the band around 1650 cm−1 corresponds to acetylated residues (NHCOCH3) of chitosan. Absence of the band at 3100 cm−1 is associated with deacetylation and differentiates crab shell chitosan standards from fungal chitosan, which explains the loss of the band at 2925 cm−1 in Cs-Agrif. The ratio of intensities of the bands at 1379 cm−1 and 2900 cm−1 has been suggested as a crystallinity index for chitin and chitosan [56,57]. This crystallinity index increases with chitosan purification. The shoulders near 890 cm−1, 1025 cm−1, 1080 cm−1, and 1155 cm−1 are specific for β-glycosidic bonds [35,58,59]. The absorption band of 1080–1085 cm−1 is characteristic of the pyranose rings and helps confirm the presence of the polysaccharide structure in the material. This band is often found alongside other characteristic peaks in the fingerprint region, such as the one near 890–905 cm−1 (saccharide structure) and bands around 1150–1160 cm−1 [60]. The bands between 1410 and 1316 cm−1 confirm the presence of phenolic compounds.

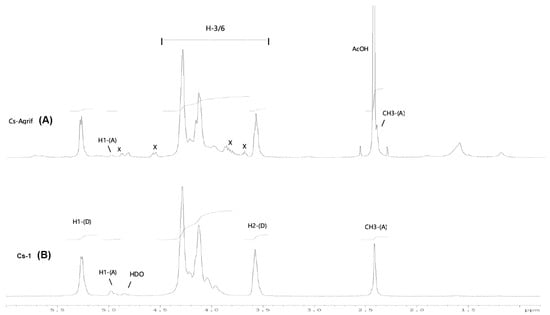

3.3. 1H-NMR Analysis of Cs-Agrif

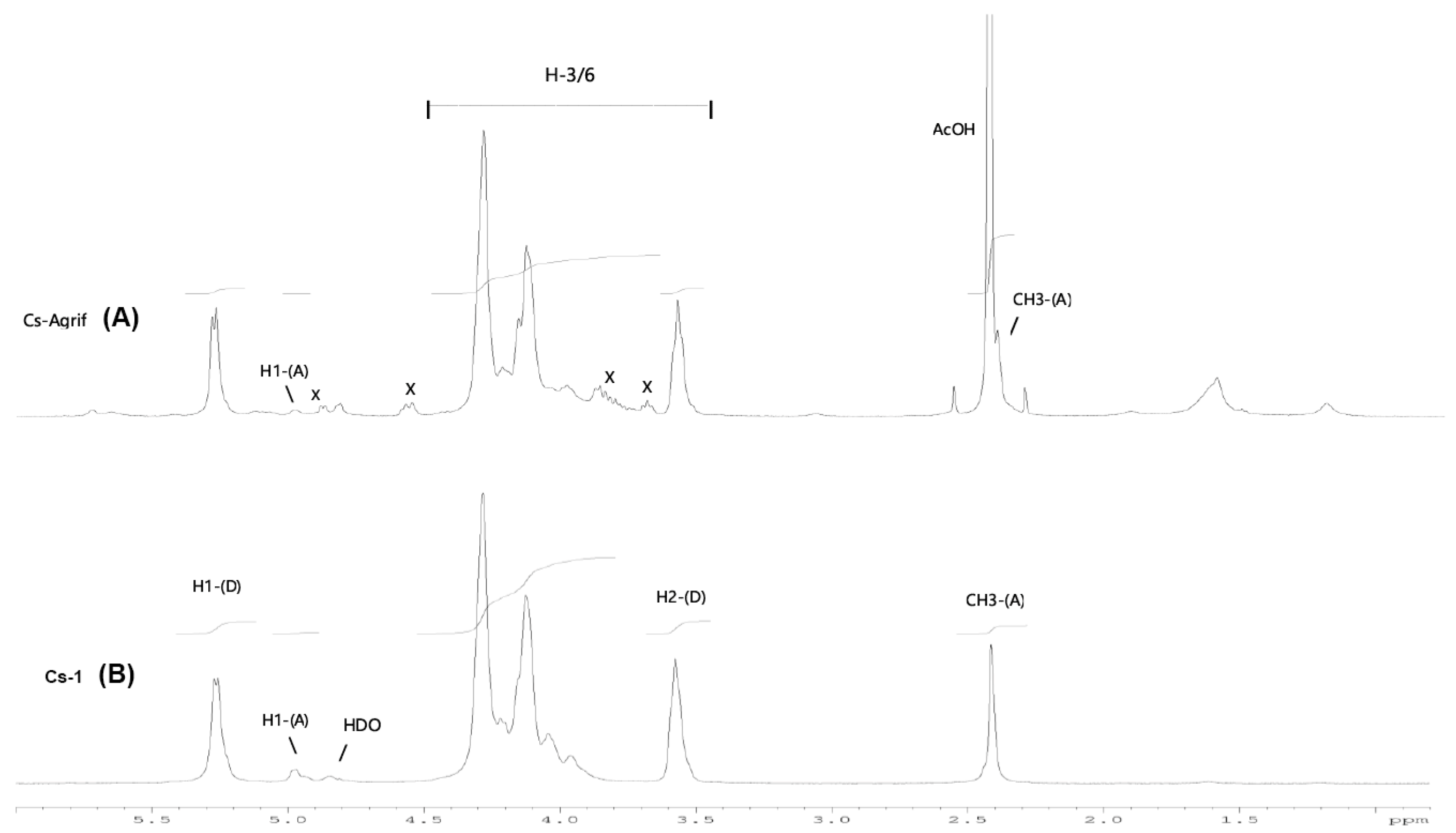

Among the methods for determining the DD of chitosan, the most reliable is 1H-NMR spectroscopy. This method has been selected as an American Standard Test Method [23,27]. The NMR spectra of Cs-Agrif (A) and the referent compound Cs-1 (B) are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The 1H-NMR spectra of Cs-1 and CS-Agrif recorded in acidic D2O, at 60 °C; (A) for acetylated; (D) for deacetylated compounds; (X) probably for β -glucans.

The signals labeled X (Figure 4) could originate from β-glucans [1]. In this study, the calculated DD value for Cs-1 was, on average, 86.1%, and that for Cs-Agrif was 92.7%. The high DD value of Cs-Agrif indicates its high potential for use in biotechnology and biomedicine as a material with good physicochemical properties.

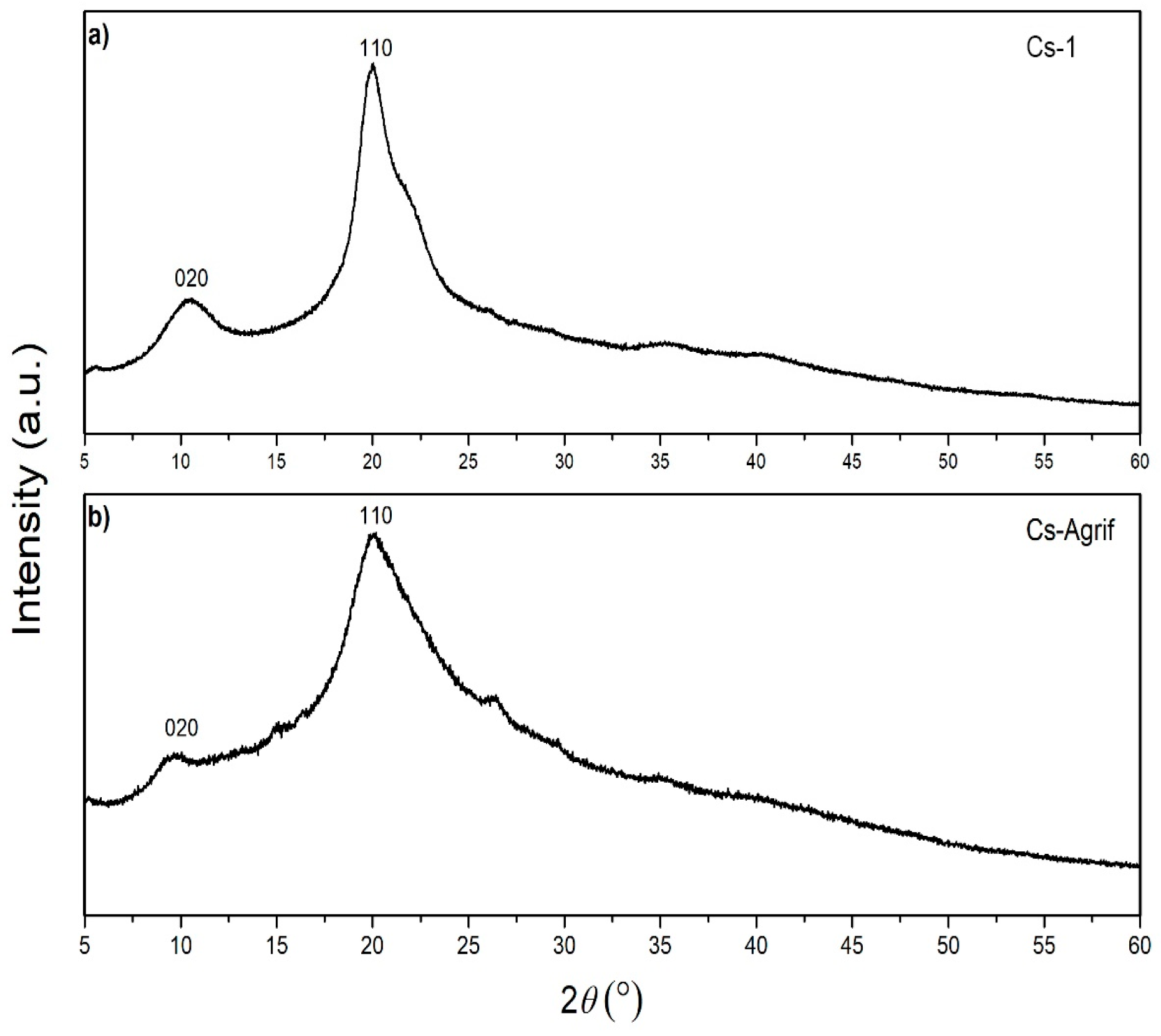

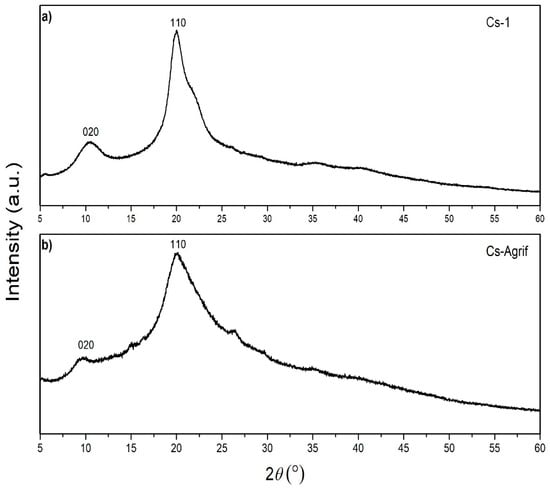

3.4. XRD Analyses of Cs-Agrif

The crystallinity of chitosan is an important characteristic from the point of view of its application. It influences the diffusion properties and accessibility of internal sorption sites [12]. An XRD spectra of Cs-1 and Cs-Agrif, is presented in Figure 5. Both samples show typical broad peaks with a high background, which is in agreement with results from previous studies [22,27,51]. Two characteristic sharp peaks, typical of chitosans, are visible at 2θ values of approximately 10° and 20°, attributed to the (020) and (110) crystalline planes as described by Mendis et al. [61]. The low-intensity peak at 2θ of about 10° is associated with crystal form I, while the higher-intensity peak at 2θ of about 20° is associated with crystal form II [62].

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction patterns of Cs-1 (a) and Cs-Agrif (b).

Some sharper peaks are visible in the XRD pattern of Cs-1, indicating higher crystallinity of pure crab shells chitosan than complex Cs-Agrif. Peak shrinkage, represented by lower intensities and reduced sharpness observed for Cs-Agrif, suggests a decrease in crystallinity in Cs-Agrif [51]. Liu et al. [27] reported that an increase in the DD reduces the crystallinity of chitosan, which is in accordance with our results. This may be a consequence of the negative influence of N-H on the formation of the polysaccharide chain crystal structure, as well as main chain fracture during the deacetylation reaction for the LMW chitosan–glucan complex isolated from mushrooms. Ospina et al. [22] suggested that crystallinity is affected by the chitosan preparation temperature and the concentration of NaOH. Such that, increasing the deacetylation temperature, base concentration, and washing time leads to an increase in the purity of the sample. Both samples, Cs-Agrif and Cs-1, exhibited peaks characteristic of the linear semicrystalline structural order of naturally occurring chitosan polymers [63]. However, from comparisons of the XRD patterns of Cs-1 and the investigated Cs-Agrif obtained from mushrooms, it can be concluded that there is no difference in the identified phases. Their XRD patterns correspond to pure chitosan that does not contain other crystalline secondary phases.

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity of Cs-Agrif

Different mechanisms underlying the antimicrobial activity of chitosan have been described in the literature. Some of them are disruption of the cell membrane structure [64], inhibition of RNA and protein synthesis via permeation into the cell nucleus [65], and chelation of essential nutrients for normal cell growth [66].

The disc diffusion results indicated antimicrobial effect of Cs-Agrif, with inhibition zone diameters of 11.3 ± 0.8 and 9.2 ± 0.6 mm noted for E. faecalis and E. coli, respectively (Table 2). The results of the disk diffusion test on the yeast strain C. albicans indicated antifungal activity by Cs-Agrif, with an inhibition zone of 8 mm.

Table 2.

Results of disc diffusion method—zone of inhibition in mm.

The broth microdilution method gave more detailed results, with the chitosan sample displaying MICs and MBCs in the range of 0.625–2.500 mg mL−1. The effects of Cs-Agrif tested against the bacterial strains E. faecalis (ATCC 29219) and E. coli (ATCC 25922) and the yeast strain C. albicans (ATCC 10231) are presented in Table 3. The data show that Cs-Agrif significantly inhibited the growth of these Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, it showed strong inhibitory/fungicidal activity against C. albicans at a concentration of ˂0.078 mg mL−1.

Table 3.

Minimal inhibitory (MIC), bactericidal (MBC) and fungicidal (MFC) concentrations of Cs-Agrif in mg mL−1.

After five days of incubation, strong inhibitory activity by Cs-Agrif against the mycotoxigenic strain A. flavus was observed (Table 4). The percentage of growth reduction was 43.66%.

Table 4.

Mycelial growth of A. flavus after 5 days of incubation (in mm).

Antimicrobial activity is influenced by several factors, including the DD, MW, pH value, type of bacterium, and environmental conditions [55,67]. Previous studies have demonstrated that LMW chitosan exhibits better antimicrobial activity, with its increased solubility allowing easier penetration through microbial cell walls [68]. Moreover, it has also been shown that chitosan with a higher DD exhibits more effective activity due to the increased density of protonated amino groups that interact with microbial cell surfaces [69]. Our results agree with those of previous studies. The presence of glucans and high content of phenolic compounds additionally increased the antimicrobial activity of the prepared Cs-Agrif. Previous studies proved the antimicrobial activity of β-glucan from mushrooms, which is an advantage in the application of chitosan from mushrooms as compared to chitosan from crabs [70]. Certain glucans from mushrooms exert antibacterial and antifungal activity by causing membrane damage. Additionally, phenolic components led to membrane damage, enzyme inhibition, and the inhibition of intracellular processes [70,71]. As such, Cs-Agrif can be used in the production of functional foods as a natural immunostimulant and bioactive component [72,73]. Fadhil and Mousa [74] indicated that the diameter of the inhibition zone for chitosan produced from A. bisporus stalks against Salmonella Typhimurium was 25 mm, while Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Psedumonas aeuroginosa, and E. coli bacteria had inhibition zone diameters of 21, 18, 17, and 15 mm, respectively. The diameter of the inhibition zone against C. albicans yeast was 14 mm after 48 h of incubation.

Chien et al. [75] reported excellent antimicrobial activity of chitosan extracted from Shiitake stipes against eight species of pathogenic bacteria, with inhibition zones ranging from 11.4 to 26.8 at concentrations as low as 0.5 mg mL−1. The difference in antimicrobial activity can be attributed to the different fungi from which the chitosan was isolated, as well as to the different methods of chitosan preparation. Savin et al. [1] found that the growth of Gram-positive bacteria was more significantly inhibited than that of Gram-negative bacteria in the presence of chitosan extracts derived from G. lucidum. The MIC for S. aureus ranged from 0.625 mg mL−1 to 2.500 mg mL−1, while P. aeruginosa exhibited increased MIC values. Mushroom-derived chitosan samples obtained from brown A. bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus [76] showed MIC values of 0.31 and 0.63 mg mL−1 against B. subtilis and E. coli, respectively, while a commercial sample exhibited an MIC value of 0.16 mg mL−1 for both bacterial species. In the same study, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed lower sensitivity to chitosan as compared to bacteria, which is in accordance with our results.

Due to its excellent biocompatibility, non-toxic nature, biodegradability, and abundant availability, chitosan has emerged as a promising candidate for antifungal applications [77]. Shahatha et al. [78] demonstrated that chitosan derived from the stalks of brown A. bisporus exhibits strong inhibitory activity against A. flavus. The inhibitory potency of chitosan increases proportionally with its concentration. The antifungal activity of chitosan is attributed to the presence of its positively charged amino groups, as well as its ability to readily penetrate fungal cell membranes. Once inside the cell, it binds to specific enzymes responsible for fungal growth, thereby inhibiting their activity [79].

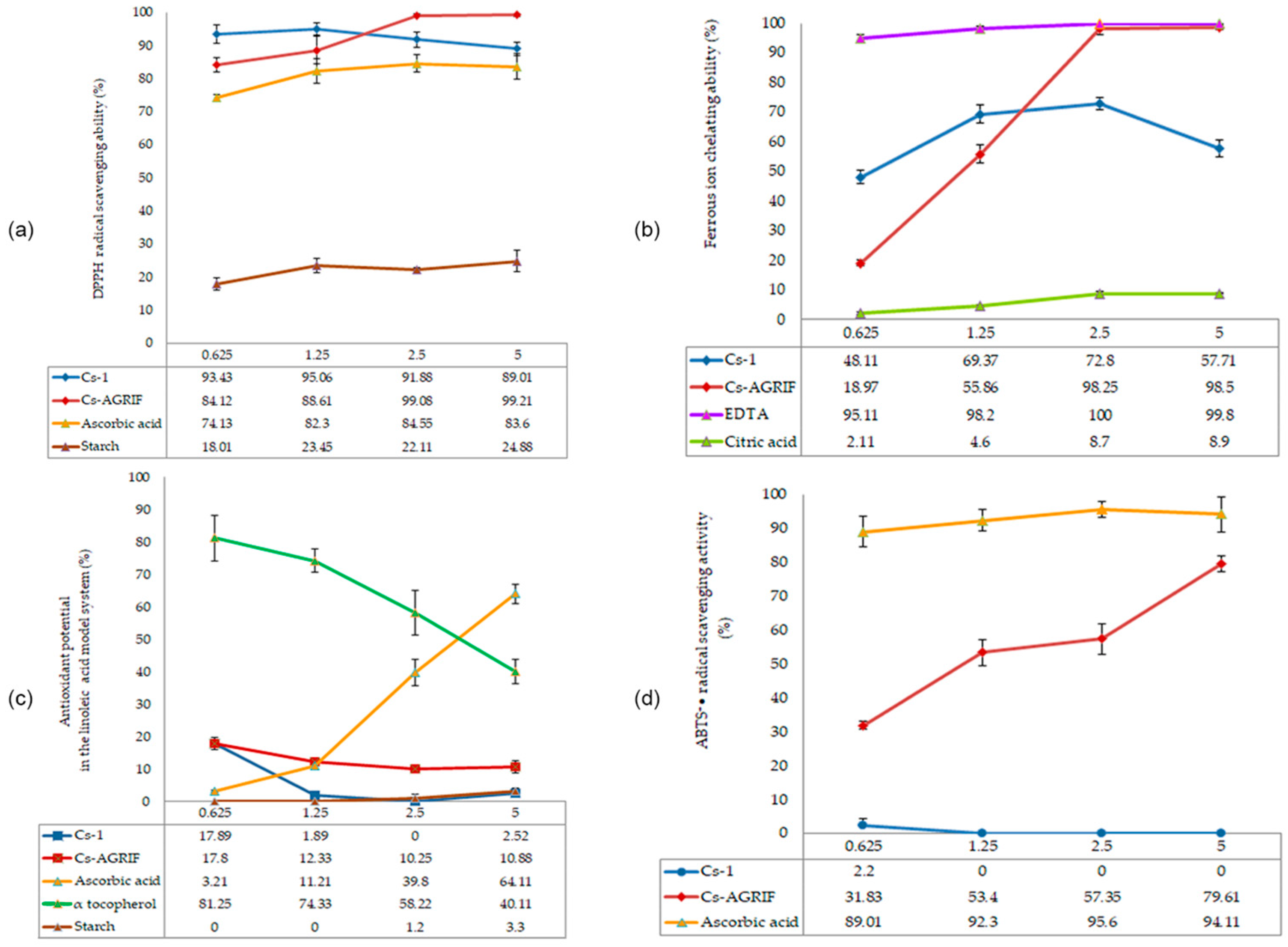

3.6. Antioxidant Activity of Cs-Agrif

Different in vitro methodologies have been applied to evaluate the antioxidant potential of chitosan and its derivatives, including DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays, FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power), hydroxyl and peroxide radical scavenging assays, and macrophage-based models [4,9,80]. While DPPH and ABTS assays are based on hydrogen atom and electron transfer, FRAP relies only on electron transfer [45]. Given that single assay methods (particularly DPPH) often yield contradictory results for chitosan, accurate evaluation of its antioxidant potential requires a combination of different methods that assess both radical scavenging and metal chelation capacity [41].

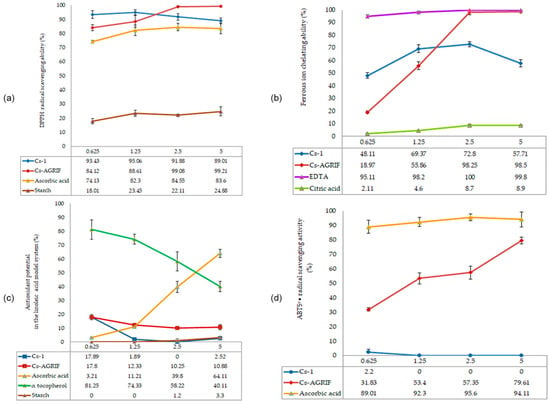

The antioxidant activity of chitosan is strongly influenced by its MW and DD. LMW chitosans (<30 kDa) with a high DD (>90%) demonstrate enhanced primary antioxidant activity [41]. Conflicting results have been reported in the literature regarding primary antioxidant capacity. Some studies have suggested that high MW chitosan with a DD of 78–87% does not exhibit significant radical scavenging activity. This lack of activity was attributed to strong intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonding that limited hydrogen availability or to residual impurities in insufficiently purified chitosan [81]. In contrast, other studies demonstrated a clear dependence on both the MW and concentration. Tomida et al. [82] reported that LMW chitosan (<30 kDa) with a high DD (>90%) has strong scavenging effects against DPPH and ABTS radicals and is also able to reduce copper ions in a concentration-dependent manner. Medium MW chitosans showed moderate activity, while high MW forms were considerably less active [82]. These findings suggest that primary antioxidant activity in chitosan is possible but highly dependent on its structural parameters and concentration. The results of the antioxidative activity analysis in this research are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Antioxidative activity of Cs-Agrif and Cs-1: (a) DPPH radical scavenging activity; (b) Ferrous ion chelation ability; (c) Lipid peroxidation inhibition ability; (d) ABTS+• radical scavenging activity. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3).

DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) radicals are purple in their free state. Through the antioxidant activity of compounds such as chitosan, neutralization—i.e., scavenging of free radicals—occurs, which is manifested by a decrease in the intensity of the purple color and a shift toward yellow [4]. Sample tested in this study exhibited excellent DPPH radical scavenging activity. Cs-Agrif showed concentration-dependent activity, reaching 99.21% at a concentration of 5 mg mL−1.

The antioxidant activity of Cs-Agrif was compared with data from Yen et al. [4] for chitosan isolated from Shiitake mushrooms and treated for 60, 90, or 120 min (samples B60, C60, B90, C90, B120, and C120). Shiitake chitosan samples B60 and C60 (from chitin decolorized with ethanol or potassium permanganate, followed by N-deacetylation) showed low DPPH scavenging activity (7.44–7.60% at 1 mg mL−1 and 28.4–31.3% at 10 mg mL−1), while with longer treatments (B90, B120, C90, C120), DPPH scavenging reached 21.8–22.4% at 1 mg mL−1 and 44.5–53.5% at 10 mg mL−1. In contrast, A. bisporus chitosan exhibited substantially greater DPPH scavenging, ranging from 84.12% at 0.625 mg mL−1 to 99.21% at 5 mg mL−1 for the Cs-Agrif samples. Although the concentrations differ (0.625–5 mg mL−1 vs. 1–10 mg mL−1), the comparison at the highest concentrations highlights the superior radical scavenging potential of Cs-Agrif.

Regarding ferrous ion chelation, Cs-Agrif showed increasing activity with increasing concentration (from 18.27% at 0.625 mg mL−1 to 98.5% at 5 mg mL−1), indicating that the laboratory isolation method yielded chitosan–glucan complex with a high DD and strong chelating ability. In comparison, Shiitake chitosans B60 and C60 exhibited 88.7–90.3% ferrous ion chelation at 1 mg mL−1 [4], with chitosans from longer treatments reaching 97.8–103% chelation at 10 mg mL−1. These results indicate that Cs-Agrif showed activity comparable to or higher than that of Shiitake chitosan at lower concentrations. This comparative analysis clearly demonstrates the differences and similarities in the antioxidant potential of chitosan from different mushroom sources.

The pronounced ability of Cs-Agrif isolated from mushroom fruiting bodies to bind DPPH radicals and chelate iron ion scan be attributed to its high DD, low MW, and high phenol content but also to the complex structure of chitosan with glucans. In earlier studies, the antioxidant activity of β-glucan from mushrooms was proven [83,84]. In addition to glucan, it is important to mention that in mushroom cell walls, melanin is found in a complex with chitin and glucans, forming a robust and dynamic structure [85]. Melanin, a negatively charged phenolic biopolymer, effectively chelates metal ions through its carboxylate and phenolic hydroxyl groups [86]. It can be removed from chitosan through a decolorization process.

The lipid peroxidation inhibition capacity of Cs-Agrif at the tested concentrations (0.625–6.25 mg mL−1) ranged from 17.80% to 10.88%. Cs-Agrif showed consistent but relatively low inhibition, with a decreasing trend at higher concentrations. According to Liu et al. [87], high concentrations of chitosan may lead to molecular aggregation and increased viscosity, thereby reducing the availability of amino groups.

For lipid peroxidation inhibition using a linoleic acid model, Shiitake chitosans B60 and C60, from a publication by Yen et al. [4], showed 82–86% inhibition at 10 mg mL−1, with longer treatments achieving the highest activity.

None of the tested standards, except for Cs-Agrif isolated from Agaricus bisporus, showed ABTS+• radical scavenging activity. For this sample, the values ranged from 31.83% to 79.61%, depending on the concentration. ABTS+• is a hydrophilic radical that exists in an aqueous system. Due to the limited solubility of chitosan, its active sites are not easily accessible, explaining the weak or absent activity in most samples. The differences as compared to DPPH radical scavenging can be attributed to the different reactivity of chitosan with the selected radical species. For example, the ABTS test can show specificity according to a certain structure of the examined compounds, while the DPPH test specifically recognizes functional groups such as –OH and –NH3+ [88].

4. Conclusions

One of the key advantages of this study is the proposal of an efficient and shortened method for extracting a highly deacetylated (92.7%) and low-molecular-weight (45.70 ± 5.20 kDa) chitosan–glucan complex from mushroom fruiting bodies with superior biological properties. Compared to commercial chitosan from crab shells, the fungal-derived biopolymer exhibited similar characteristics to commercial chitosan from crab shells, such as pseudoplasticity, but lower crystallinity. The novelty of the research is the quantification of phenolic compounds in the complex for the first time. The presence of glucans and phenols in the chitosan biopolymer exhibited superior antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of the mushroom-derived sample. This is of great importance due to increasing microbial resistance and awareness about the role of antioxidants in preventing chronic diseases. In the modern global market, antioxidant nutraceuticals are in high demand. The antioxidant nutraceuticals market is projected to reach $6.7 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.7% from 2023 to 2030 (https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/09/06/2942036/28124/en/Antioxidants-Global-Strategic-Business-Report-to-2030.html, accessed on 20 November 2025). Future research should focus on the extraction parameters to maximize yield, as well as exploring its application in the biotechnological field as a biobased alternative. Furthermore, partnerships with mushroom cultivation industries through the valorization of the low-quality class of mushrooms for chitosan extraction can reduce the food industry’s environmental impact and minimize the costs of the production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P., M.K., J.T., D.K. and A.D.; methodology, M.P., M.K., V.L. and A.D.; formal analysis, D.K., N.T., N.M., M.O. and M.M.; investigation, J.T., M.K., A.D. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T., M.P., V.L., D.K., N.T., N.M., M.O. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, A.D., N.M., M.P., M.K. and N.T.; visualization, D.K., M.K., M.O. and V.L.; supervision, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 7748088, Project: Composite clays as advanced materials in animal nutrition and biomedicine—AniNutBiomedCLAYs), and by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-137/2025-03/200116; 451-03-136/2025-03/200017 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Delta Danube d.o.o, Kovin (Serbia) for kindly providing the Agaricus bisporus used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

1H-NMR spectrum of sample Cs-Agrif.

Figure A1.

1H-NMR spectrum of sample Cs-Agrif.

Figure A2.

1H-NMR spectrum of sample Cs-1.

Figure A2.

1H-NMR spectrum of sample Cs-1.

References

- Savin, S.; Craciunescu, O.; Oancea, A.; Ilie, D.; Ciucan, T.; Antohi, L.S.; Toma, A.; Nicolescu, A.; Deleanu, C.; Oancea, F. Antioxidant, Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan Preparations Extracted from Ganoderma Lucidum Mushroom. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Chitosan: Sources, Processing and Modification Techniques. Gels 2022, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasvandian, S.; Shahgholi, M.; Karimipour, A. Investigating the effects of chitosan atomic ratio and drug type on mechanical properties of silica aerogel/chitosan nanocomposites using molecular dynamics approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 401, 124639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.-T.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Li, R.-C.; Mau, J.-L. Antioxidant Properties of Fungal Chitosan from Shiitake Stipes. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C. Recent Patents on Food Applications of Chitosan. FNA 2010, 2, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latańska, I.; Rosiak, P.; Paul, P.; Sujka, W.; Kolesińska, B. Modulating the physicochemical properties of chitin and chitosan as a method of obtaining new biological properties of biodegradable materials. In Chitin and Chitosan—Physicochemical Properties and Industrial Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čalija, B.; Milić, J.; Krajišnik, D.; Račić, A. Karakteristike i primena hitozana u farmaceutskim/biomedicinskim preparatima. Arh. Farm. 2013, 63, 347–364. [Google Scholar]

- Raafat, D.; Sahl, H. Chitosan and Its Antimicrobial Potential—A Critical Literature Survey. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.G.; Yaneva, Z.L. Antioxidant Properties and Redox-Modulating Activity of Chitosan and Its Derivatives: Biomaterials with Application in Cancer Therapy. BioResearch Open Access 2020, 9, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Sam, S.T.; Yaacob, N.D.; Tan, W.K. Fungal Chitosan in Focus: A Comprehensive Review on Extraction Methods and Applications. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Kujundzic, M.; John, S.; Bismarck, A. Crab vs. Mushroom: A Review of Crustacean and Fungal Chitin in Wound Treatment. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T. Production and Characterization of Fungal Chitin and Chitosan. Master’s Thesis, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, T.H.; Alves, A.; Ferreira, B.M.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reys, L.L.; Ferreira, R.J.F.; Sousa, R.A.; Silva, S.S.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Materials of Marine Origin: A Review on Polymers and Ceramics of Biomedical Interest. Int. Mater. Rev. 2012, 57, 276–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.; Silva, D.; Couto, M.; Nunes, C.; Rocha, S.M.; Coimbra, M.A.; Coimbra, A.; Moreira, A. Safety of Chitosan Processed Wine in Shrimp Allergic Patients. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 462–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, S.M.; Nunes, F.M. Agaricus bisporus By-Products as a Source of Chitin-Glucan Complex Enriched Dietary Fibre with Potential Bioactivity. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharanathan, R.N.; Kittur, F.S. Chitin—The Undisputed Biomolecule of Great Potential. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2003, 43, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, H.; Kour, D.; Kour, S.; Singh, S.; Jawad Hashmi, S.A.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, K.; Sharma, Y.P.; Ahluwalia, A.S. Bioactive Compounds from Mushrooms: Emerging Bioresources of Food and Nutraceuticals. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, R.W.; Macharia, J.M.; Wagara, I.N.; Bence, R.L. The Antioxidant Potential of Different Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Medina, G.A.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Verma, D.K.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Thakur, M.; Srivastav, P.P.; Aguilar, C.N. Bio-Funcional Components in Mushrooms, a Health Opportunity: Ergothionine and Huitlacohe as Recent Trends. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahndral, A.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Chaudhary, P.; Mukarram Shaikh, A.; Béla, K. Microwave Assisted Extraction of Chitosan from Agaricus Bisporus: Techno-Functional and Microstructural Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 9, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandy, M.A.M.; Rovina, K. Characterization of chitosan derived from mushroom sources: Physicochemical, morphological, thermal analysis. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 40, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa Ospina, N.; Ospina Alvarez, S.P.; Escobar Sierra, D.M.; Rojas Vahos, D.F.; Zapata Ocampo, P.A.; Ossa Orozco, C.P. Isolation of Chitosan from Ganoderma Lucidum Mushroom for Biomedical Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, I.C.G.; Teixeira, S.C.; Souza, M.V.d., Jr.; Conde, M.B.M.; Bailon, G.R.; Cardoso, S.H.S.; Araújo, L.D.; Oliveira, E.B.d.; Ferreira, S.O.; Oliveira, T.V.d.; et al. Sustainable Extraction and Multimodal Characterization of Fungal Chitosan from Agaricus bisporus. Foods 2025, 14, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsecka, M.; Mleczek, M.; Siwulski, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Kozak, L. The Effect of Selenium on Phenolics and Flavonoids in Selected Edible White Rot Fungi. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Račić, A.; Čalija, B.; Milić, J.; Milašinović, N.; Krajišnik, D. Development of Polysaccharide-Based Mucoadhesive Ophthalmic Lubricating Vehicles: The Effect of Different Polymers on Physicochemical Properties and Functionality. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, M.Y.; Abdel-Razik, E.A.; Abdel-Bary, E.M.; El-Sherbiny, I.M. Chitosan-based Interpolymeric pH-responsive Hydrogels for in Vitro Drug Release. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 103, 2864–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, G.; Sui, W.; An, L.; Si, C. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan by a Novel Deacetylation Approach Using Glycerol as Green Reaction Solvent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4690–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowska-Biskup, R.; Jarosińska, D.; Rokita, B.; Ulański, P.; Rosiak, J. Determination of Degree of Deacetylation of Chitosan—Comparision of Methods. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin Its Deriv. 2012, 2012, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanova, M.; Pantic, M.; Klaus, A.; Mihajlovic, D.; Miletic, D.; Sobajic, S.; Stojanova, M.T.; Niksic, M. Bio Soups—New Functional Dehydrated Soups Enriched with Lyophilised Fuscoporia torulosa Extracts. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 3628–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, D.; Pantić, M.; Pavlović, V.; Nedović, V.; Lević, S.; Matijašević, D.; Sknepnek, A.; Nikšić, M. Advances in Batch Culture Fermented Coriolus Versicolor Medicinal Mushroom for the Production of Antibacterial Compounds. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, M.; Anedjelkovic, I.; Duvnjak, D.; Matijasevic, D.; Avramovic, A.; Niksic, M. The Fungistatic Activity of Organic Selenium and Its Application to the Production of Cultivated Mushrooms Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus spp. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2012, 64, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavertu, M.; Xia, Z.; Serreqi, A.N.; Berrada, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Wang, D.; Buschmann, M.D.; Gupta, A. A Validated 1H NMR Method for the Determination of the Degree of Deacetylation of Chitosan. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2003, 32, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Nikšić, M.; Vrvić, M.M.; Todorović, N.; Jakovljević, D.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative Activities and Chemical Characterization of Polysaccharide Extracts from the Widely Used Mushrooms Ganoderma Applanatum, Ganoderma Lucidum, Lentinus Edodes and Trametes Versicolor. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 26, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Niksic, M.; Jakovljevic, D.; Helsper, J.P.F.G.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative and Immunomodulating Activities of Polysaccharide Extracts of the Medicinal Mushrooms Agaricus Bisporus, Agaricus Brasiliensis, Ganoderma Lucidum and Phellinus Linteus. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.P.; Madeira, V.M.C.; Almeida, L.M. Action of Phenolic Derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as Inhibitors of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and as Peroxyl Radical Scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwesh, O.M.; Sultan, Y.Y.; Seif, M.M.; Marrez, D.A. Bio-Evaluation of Crustacean and Fungal Nano-Chitosan for Applying as Food Ingredient. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.-T.; Mau, J.-L. Physico-Chemical Characterization of Fungal Chitosan from Shiitake Stipes. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.H.; Williams, P.A.; Tverezovskaya, O. Extraction of Chitin from Prawn Shells and Conversion to Low Molecular Mass Chitosan. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 31, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanat, M.; Colijn, I.; de Boer, K.; Schroën, K. Comparison of the Degree of Acetylation of Chitin Nanocrystals Measured by Various Analysis Methods. Polymers 2023, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromis, N.; Lazic, V.; Popovic, S.; Suput, D.; Bulut, S. Antioxidative Activity of Chitosan and Chitosan Based Biopolymer Film. Food Feed Res. 2017, 44, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssekatawa, K.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Wampande, E.M.; Moja, T.N.; Nxumalo, E.; Maaza, M.; Sackey, J.; Ejobi, F.; Kirabira, J.B. Isolation and Characterization of Chitosan from Ugandan Edible Mushrooms, Nile Perch Scales and Banana Weevils for Biomedical Applications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmami, H.; Ben Amor, I.; Zeghoud, S.; Ben Amor, A.; Laouini, S.E.; Alsalme, A.; Cornu, D.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Chitosan Extraction from Amanita Phalloides: Yield, Crystallinity, Degree of Deacetylation, Azo Dye Removal and Antibacterial Properties. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1353524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, N.; Fernández, L.; Barceló, F.; Spikes, H. Shear Thinning and Hydrodynamic Friction of Viscosity Modifier-Containing Oils. Part I: Shear Thinning Behaviour. Tribol. Lett. 2018, 66, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, H.; Ho, V.; Zhou, J. Rheological Characteristics of Soluble Fibres during Chemically Simulated Digestion and Their Suitability for Gastroparesis Patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Meenu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, B. A Concise Review on the Molecular Structure and Function Relationship of β-Glucan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Ritzoulis, C.; Chen, J. Rheological investigations of beta glucan functionality: Interactions with mucin. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 87, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Du, B.; Xu, B. A critical review on production and industrial applications of beta-glucans. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabea, E.I.; Badawy, M.E.-T.; Stevens, C.V.; Smagghe, G.; Steurbaut, W. Chitosan as Antimicrobial Agent: Applications and Mode of Action. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román-Doval, S.R.; Torres-Arellanes, S.P.; Tenorio-Barajas, A.Y.; Gómez-Sánchez, A.; Valencia-Lazcano, A.A. Chitosan: Properties and Its Application in Agriculture in Context of Molecular Weight. Polymers 2023, 15, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crognale, S.; Russo, C.; Petruccioli, M.; D’Annibale, A. Chitosan Production by Fungi: Current State of Knowledge, Future Opportunities and Constraints. Fermentation 2022, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasale, M.F.J.D.P.; Bijang, C.M.; Rumpakwara, E. Preparation of Chitosan with Various Molecular Weight and Its Effect on Depolymerization of Chitosan with Hydrogen Peroxide Using Conventional Technique. IJCTR 2019, 12, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Du, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Cai, J.; Kennedy, J.F. A New Green Technology for Direct Production of Low Molecular Weight Chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, M.; Lazic, V.; Kozarski, M. Mushroom chitosan: A promising biopolymer in the food industry and agriculture. Hrana Ishr. 2023, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar Junior, J.C.; Ribeaux, D.R.; Alves Da Silva, C.A.; De Campos-Takaki, G.M. Physicochemical and Antibacterial Properties of Chitosan Extracted from Waste Shrimp Shells. Int. J. Microbiol. 2016, 2016, 5127515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focher, B.; Beltrame, P.L.; Naggi, A.; Torri, G. Alkaline N-Deacetylation of Chitin Enhanced by Flash Treatments. Reaction Kinetics and Structure Modifications. Carbohydr. Polym. 1990, 12, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijašević, D.; Pantić, M.; Rašković, B.; Pavlović, V.; Duvnjak, D.; Sknepnek, A.; Nikšić, M. The Antibacterial Activity of Coriolus versicolor Methanol Extract and Its Effect on Ultrastructural Changes of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella Enteritidis. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, T.; He, W.; He, Y. Antibacterial Ability and Feature of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Chitosan/Montmorillonite/Copper Nanoparticle Composite Gel Beads. Processes 2025, 13, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, A.; Thambiliyagodage, C.; Ekanayake, G.; Liyanaarachchi, H.; Jayanetti, M.; Vigneswaran, S. Fabrication of Naturally Derived Chitosan and Ilmenite Sand-Based TiO2/Fe2O3/Fe-N-Doped Graphitic Carbon Composite for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue under Sunlight. Molecules 2023, 28, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpintero, M.; Marcet, I.; Cortizo, C.; Guerrero, P.; De La Caba, K.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Chitosan Modification with Octenyl Succinic Anhydride (OSA): Effect of the Degree of Substitution on the Structural, Mechanical and Barrier Properties in the Synthetized Bioplastics. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 171, 111838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamad, D.M.; Muhammad, D.S.; Aziz, S.B.; Muheddin, D.Q.; Ahmed, B.Y.; Abdalkarim, K.A.; Al-Asbahi, B.A.; Ahmed, A.A.A.; Abdullah, O.G. Improvement the Optoelectronic Properties of Chitosan Biopolymer Using Natural Dye of Black Olive as a Novel Approach: FTIR, XRD and UV–Vis Spectroscopic Studies. Opt. Mater. 2025, 164, 117057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Mode of Action: A State of the Art Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Atay, H. Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan-Based Systems. In Functional Chitosan; Jana, S., Jana, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 457–489. ISBN 978-981-15-0262-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sahariah, P.; Másson, M. Antimicrobial Chitosan and Chitosan Derivatives: A Review of the Structure–Activity Relationship. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3846–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubiev, O.M.; Egorov, A.R.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Chitosan-Based Antibacterial Films for Biomedical and Food Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.C.; Van Hoa, N.; Trung, T.S. Preparation, Properties, and Application of Low-Molecular-Weight Chitosan. In Handbook of Chitin and Chitosan; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 453–471. ISBN 978-0-12-817970-3. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, G.; Azad, M.A.K.; Lin, Y.; Kim, S.W.; Tian, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, H. Biological Effects and Applications of Chitosan and Chito-Oligosaccharides. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Gani, A.; Khanday, F.A.; Masoodi, F.A. Biological and Pharmaceutical Activities of Mushroom β-Glucan Discussed as a Potential Functional Food Ingredient. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2018, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.J.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Froufe, H.J.C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Martins, A.; Pintado, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Phenolic Compounds Identified in Wild Mushrooms, SAR Analysis and Docking Studies. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; van Griensven, L.; Jakovljevic, D.; Todorovic, N.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I.; Vunduk, J. Mushroom β-glucan and polyphenol formulations as natural immunity boosters and balancers: Nature of the application. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, P.; Govers, C.; Wichers, H.J.; Debets, R. Consumption of β-glucans to spice up T cell treatment of tumors: A review. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, A.; Mousa, E. Antimicrobal Activities of Chitosan Produces from Agaricus Bisporus Stalks. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, R.-C.; Yen, M.-T.; Mau, J.-L. Antimicrobial and Antitumor Activities of Chitosan from Shiitake Stipes, Compared to Commercial Chitosan from Crab Shells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 138, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Z.; Horev, B.; Rutenberg, R.; Danay, O.; Bilbao, C.; McHugh, T.; Rodov, V.; Poverenov, E. Efficient Production of Fungal Chitosan Utilizing an Advanced Freeze-Thawing Method; Quality and Activity Studies. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, Z. Cationic Chitosan Derivatives as Potential Antifungals: A Review of Structural Optimization and Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahadha, A.; Khaleel, I.; Rashid, N. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Chitosan Produces from the Stalks of Agaricus Bisporus against Aspergillus Flavus and Reducing Aflatoxin B1. Iraqi J. Mark. Res. Consum. Prot. 2024, 16, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing, L.Y.; Zin, N.M.; Sarwar, A.; Katas, H. Antifungal Activity of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Correlation with Their Physical Properties. Int. J. Biomater. 2012, 2012, 632698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.-H.; Qian, Z.-J.; Vo, T.-S.; Ryu, B.; Ngo, D.-N.; Kim, S.-K. Antioxidant Activity of Gallate-Chitooligosaccharides in Mouse Macrophage RAW264.7 Cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatt, S.R.; Rao, M.S.; Chawla, S.P.; Sharma, A. Active Chitosan–Polyvinyl Alcohol Films with Natural Extracts. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 29, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomida, H.; Fujii, T.; Furutani, N.; Michihara, A.; Yasufuku, T.; Akasaki, K.; Maruyama, T.; Otagiri, M.; Gebicki, J.M.; Anraku, M. Antioxidant Properties of Some Different Molecular Weight Chitosans. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrnic-Ciric, M.; Dabetic, N.; Todorovic, V.; Djuris, J.; Vidovic, B. Beta-Glucan Content and Antioxidant Activities of Mushroom-Derived Food Supplements. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2020, 85, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.K.; Samanta, S.; Maity, S.; Sen, I.K.; Khatua, S.; Devi, K.S.P.; Acharya, K.; Maiti, T.K.; Islam, S.S. Antioxidant and Immunostimulant β-Glucan from Edible Mushroom Russula albonigra (Krombh.) Fr. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 99, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seniuk, O.; Kurochko, N.; Cuzminski, Z.; Tyshko, R. Evaluation of the Chitin-Glucan-Melanin Complex from Fomes Fomentarius for Stopping Bleeding and Providing First Aid for Laceration and Burns in Combat Conditions. EUREKA Life Sci. 2024, 3, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, 498276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bao, J.; Du, Y.; Zhou, X.; Kennedy, J.F. Effect of Ultrasonic Treatment on the Biochemphysical Properties of Chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Herfellner, T.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Miesbauer, O.; Eisner, P. Common Trends and Differences in Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Phenolic Substances Using Single Electron Transfer Based Assays. Molecules 2021, 26, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).