Abstract

This study focused on optimising the saccharification of cardoon mixed residues through acid or base-catalysed steam explosion, using a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimise the main process parameters. Despite the increasing interest in cardoon as a lignocellulosic feedstock, its efficient fractionation remains challenging, with limited cellulose hydrolysis and incomplete hemicellulose recovery under non-optimised steam explosion conditions. Therefore, a systematic evaluation of catalytic severity is required to improve biomass valorisation. H2SO4-catalysed steam explosion significantly improved glucan hydrolysis in the following enzymatic saccharification process, achieving 78 mol% glucose yield after a pretreatment carried out at 200 °C, 5 min, and 25 mM catalyst concentration. Xylan recovery required a higher catalyst concentration of 50 mM and temperatures lower than 220 °C to avoid the dehydration reaction of xylose to furfural. The optimal conditions for maximising glucose and xylose yields were 196 °C for 5 min with 50 mM H2SO4, resulting in 80.5 mol% glucose yield and 70.3 mol% xylose yield. Alkaline-catalysed steam explosion at 200 °C with 25 mM NaOH increased the enzymatic hydrolysis of glucan and favoured the production of lignin with a higher syringyl/guaiacyl ratio, making it more reactive. Overall, this research provides valuable insights into catalytic steam explosion coupled with the enzymatic saccharification step for the complete valorisation of lignocellulosic cardoon residues.

1. Introduction

Cardoon (Cynara cardunculus L.), a perennial plant from the Asteraceae family, is increasingly recognized as a versatile and sustainable crop, particularly suitable for marginal and uncultivated lands. Its cultivation requires minimal water and nutrient inputs, no irrigation, and reduced herbicide use, making it an excellent option for regions with limited resources, such as the Mediterranean basin [1,2]. Cardoon is a low-maintenance crop with modest soil tillage requirements and annual biomass collection, reducing erosion risks and limiting CO2 emissions, thereby positioning it as one of the most sustainable industrial and energy crops [2,3]. Its adaptability to marginal soils and its multipurpose applications have also been highlighted in studies exploring biomass production potential for bioenergy and biorefineries. The plant is particularly valued for its wide range of potential applications. Oil extracted from cardoon seeds can be utilized for industrial purposes or converted into biopolymers, such as azelaic and pelargonic acids, while protein-rich extraction flours serve as an alternative to genetically modified soybean meal in animal feed and as a nutraceutical source [4,5]. Additionally, cardoon roots contain inulin, a versatile fructan employed in food, biofuel, and biopolymer industries [6]. A significant proportion of cardoon biomass consists of its lignocellulosic fraction. This fraction is the remaining biomass after oilseed harvesting from the capitulum. It includes stems, leaves, and other non-seed tissues. This fraction is particularly promising for integration into biorefinery frameworks. This is due to its high cellulose and hemicellulose content. There is also the possibility of lignin valorization.

Efficient biomass fractionation requires an initial pretreatment step to disrupt the lignocellulosic matrix, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis to release fermentable sugars for biofuels and biochemicals. Several pretreatment methods have been explored, including steam explosion, dilute acid, and organosolv processes, which allow for the exploitation of all biomass components [7,8]. The composition and quality of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin can be tailored for various applications [9,10,11,12,13].

Among these methods, steam explosion stands out as a versatile pretreatment, commonly applied to improve biomass accessibility. High-pressure steam disrupts the lignocellulosic structure, followed by rapid decompression that creates fissures in the cell walls. However, during steam explosion, the harsh conditions, particularly high temperatures, cause significant degradation of hemicellulosic sugars. This degradation reduces sugar yield, while the resulting by-products can inhibit subsequent steps, including fermentation-based biocatalytic upgrading [14,15,16]. To mitigate these challenges, catalysts are employed to promote high levels of fractionation while reducing the thermal severity of the process [17]. Catalytic integration improves steam explosion efficiency: acid catalysis enhances hemicellulose hydrolysis and xylan recovery, whereas base catalysis alters lignin structure, increasing its reactivity for advanced applications. These enhancements facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis and optimize sugar yields, which are crucial for producing bioethanol and other bio-based products [18,19,20,21]. Alkaline catalytic approaches also show promise in enhancing biomass deconstruction [22,23,24].

The lignin fraction plays a pivotal role in determining the overall sustainability of biorefineries. While lignin is mainly used for energy generation through combustion, it also holds potential for producing valuable chemicals, such as aromatics and cyclic alkanes [25,26]. These catalytic approaches optimize sugar recovery, lignin utilization, and overall biorefinery efficiency, bridging key knowledge gaps in cardoon biomass research [27,28].

In this work, “sustainable fractionation” refers to using aqueous, solvent-free steam explosion conditions; applying low-cost, widely available acid or alkaline solutions; and operating under moderate reaction times with industrially scalable equipment. Compared to solvent-based pretreatments or high-severity thermal processes, acid- and base-assisted steam explosion minimizes chemical consumption and energy demand while enabling the recovery and valorization of all biomass fractions (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin). This process is a key element of sustainable biorefinery strategies.

Cardoon has been widely studied as a multipurpose crop, but the valorization of residues remaining after oilseed harvesting has received limited attention, especially with regard to their suitability for integrated biorefinery processes. This study is novel because it combines tailored pretreatment conditions with a detailed assessment of the obtained fractions and a comparative evaluation of enzymatic hydrolysis. Importantly, our study focuses on the catalytic aspects of biomass fractionation and enzymatic biocatalysis rather than the development of new catalytic materials. This approach fills an existing research gap by providing a comprehensive evaluation of cardoon residues and their potential for the efficient, sustainable valorization of biomass. The aim of this study was to optimize the effect of acid- and base-catalyzed steam explosion of cardoon residues on the subsequent enzymatic saccharification process through a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) approach and preliminarily assess their influence on specific lignin properties, highlighting its potential to enhance the environmental and economic feasibility of bio-based industrial processes. RSM is more efficient than orthogonal experiments for process optimization, requiring fewer trials to build a predictive model. This allows us to visualize the “response surface” and identify the precise conditions for maximum yield. This provides deeper insight and a more complete picture for developing a scalable process for cardoon biomass.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock

Cardoon residues were provided by the Italian company Novamont (Novara, Italy) and produced at the industrial level at the Matrica® plant (Porto Torres, Sardinia, Italy). Before the steam explosion pretreatment, the biomass was ground with a straw chopper into small particles with a diameter of around 1.7–5.6 mm. The feedstock, which contained 81.0 ± 0.3% dry matter, was sampled and milled using a Retsch ZM-200 (Haan, Germany) knife mill. It was then sieved to pass through a 50-mesh screen with a particle size of ~300 µm and dried at 55 °C overnight. Finally, laboratory characterizations were performed to determine the extractives, carbohydrates, lignin, and ashes using standard NREL methods [29].

Three replicates were carried out for each type of analysis.

2.2. Steam Explosion Pretreatment

The cardoon biomass pretreatment was performed according to our previous optimized work [11] and using a steam explosion batch unit (10 L Staketech reactor—ENEA, Trisaia, Italy). To adjust the biomass moisture content and facilitate its deconstruction, the biomass was first impregnated at room temperature. Specifically, 0.5 kg of dry biomass was immersed in 10 L of impregnation solution: demineralized water for the non-catalyzed steam explosion (NCSE), or 25 mM or 50 mM sulfuric acid solution for the acid-catalyzed steam explosion (ACSE), or 25 mM or 50 mM sodium hydroxide solution for the base-catalyzed steam explosion (BCSE). After 10 min of soaking, excess liquid was removed using a filter press, resulting in impregnated solids with a dry matter content of about 35 wt%. Steam explosion pretreatments were then carried out at 180, 200, or 220 °C for 5 min. After each pretreatment, the material was pressed to separate the water-insoluble fraction (WIF), mainly cellulose and lignin, from the liquid fraction (LF), which contained hemicellulose derivatives and other soluble compounds. A mass balance was performed for each condition to quantify the recovery of xylan, expressed as monomeric xylose and xylo-oligomers, relative to the initial xylan content in the raw biomass. The solid fractions were resuspended in hot water (65 °C) at 5 wt% biomass loading for 30 min, then filtered through a Büchner funnel before enzymatic hydrolysis. The LF was analyzed to determine the concentrations of monomeric sugars, furanic derivatives, aromatic compounds, and organic acids. The oligomer content was calculated as the difference after acid post-hydrolysis of sugars, which was performed in an autoclave at 120 °C, 1 bar for 45 min using 3 wt% H2SO4.

2.3. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Enzymatic hydrolysis was performed at 5 wt% solid content in 200 mL shaken flasks, maintained at 180 rpm and 50 °C for 96 h, using a citrate buffer at pH 4.8. The enzymatic hydrolysis tests were carried out on the water-insoluble fractions (WIFs) derived from steam explosion, which were washed with hot water at 65 °C to remove residual hemicellulose. The enzymatic mixture Cellic® CTec2 was added with a catalyst loading of 15 FPU (Filter Paper Units) per gram of glucan [7,8]. The enzymatic activity was measured by the standard procedure before the experiments and was 178 FPU/mL [30]. The commercial enzyme was kindly provided by Novozymes (Bagsværd, Denmark). The mean values were reported for each enzymatic reaction performed in duplicate.

2.4. Analytical Methods

Monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, mannose) and acetic acid were determined using an HPIC DX 300 chromatographic system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with a Nucleogel Ion 300 OA column (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) operating at 60 °C with 10 mN H2SO4 solution as mobile phase and a flux of 0.4 mL/min. Samples were pre-filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane before injection. The detector used was a Shodex RI101 refractive index detector. Furan derivatives (2-furaldehyde and 5-hydroxymethyl-furaldehyde) were quantified using an HP1100 system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), equipped with an RP18 5 μm LiChroCart 250 × 4 mm column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), operating at 50 °C. The mobile phase was a 1:1 v/v mixture of Milli-Q water and acetonitrile. The detector was a diode array operating at 210 and 280 nm. Each analysis was performed in triplicate. All the quantifications were performed through the external standard technique. All reagents and standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.5. Determination of Combined Severity Factor (CSF)

In the steam explosion pretreatment, the process severity factor (log(R0)) is widely used to quantify the combined effect of reaction time (t), expressed in minutes, and temperature (T), expressed in °C, on biomass disruption (Equation (1)) [31]:

log(R0) = log[t × exp {(T − 100)/14.75}]

However, when acid or base catalysts are employed, the equation must account for catalytic effects, and its calculation has evolved from the original formulation by Abatzoglou et al. (1992) [31] to that proposed by Pedersen et al. [32] (Equation (2)). For this reason, the severity factor was calculated as the combined severity factor (CSF):

where the pH value was that of the impregnated slurry before the steam explosion treatment.

CSF = log(R0)’ = log(R0) + ∣pH − 7∣ = log[t × exp {(T − 100)/14.75}] + ∣pH − 7∣

2.6. Design of Experiment

Response surface methodology (RSM), based on a 3-level and 2-factor face-centered Central Composite Design (CCD), was used to investigate the influence of the temperature and the amount of the catalyst (as independent variables) on two main responses (dependent variables): glucan hydrolysability and xylan recovery [33]. A face-centered CCD is a type of response surface methodology used in chemometric approaches to design experiments (DoE) to model and optimize processes. This design consists of factorial, center, and axial points located at the faces of the design space. It allows for the estimation of the linear, interaction, and quadratic effects of the variables with a limited number of experiments.

The Design-Experiment® software, version 10 (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), was used to create the experimental matrix and for data elaboration.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate model validation. A second-order polynomial regression model (Equation (3)) was developed based on the experimental data (α = 0.05) and applied to generate response surface and contour plot graphs:

where Y is the predicted value, A and B are the independent variables (temperature and catalyst concentration, respectively), β0 is the intercept, β1 and β2 are the linear regression coefficients, β3 is the cross-product coefficient, while β4 and β5 are the quadratic coefficients associated with each factor.

Y = β0 + β1A + β2B + β3AB + β4A2 + β5B2

As shown in Table 1, three levels of each variable were tested: 180, 200 and 220 °C for the temperature and 0, 25 and 50 mM for the catalyst concentration.

Table 1.

Experimental design range and levels of the two factors, namely temperature (°C) and catalyst concentration (mM).

Two distinct designs with the same setup (Table 1) were performed to alternatively test acid and base catalysts (H2SO4 and NaOH).

2.7. Lignin Isolation and Characterization

Lignin was isolated from cardoon both before and after steam explosion treatment using NaOH solution as an extracting solvent and H2SO4 solution for the re-precipitation of acid-insoluble lignin. Specifically, 50 g of dry biomass was suspended in 500 mL of 1.5 wt% NaOH solution and heated to reflux at 90 °C for 30 min. After the alkali treatment, the reaction mixture was filtered and then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min to separate the residual pulp biomass. The filtered liquid was then adjusted to pH 2 by adding 1 N H2SO4 solution dropwise to precipitate the acid-insoluble lignin. The obtained lignin samples were washed with deionized water, dried in a hot air oven at 50 °C for 3 h, and stored for further processing.

Pyrolysis coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) was employed to investigate the structure of lignin precursors according to the literature [34,35].

Py-GC/MS analyses were carried out by using a Gerstel pyro (SRA Instruments–Milano, Italy) directly combined with the injection system of a GC Agilent 6890N equipped with an Agilent 5975A mass spectrometer. About 2 mg of each sample was introduced into a quartz tube inside the pyrolyser. The samples were initially held at 50 °C for 60 s, then ramped at 50 °C/s to a final temperature of 600 °C and held for 1 min. GC separation of the pyrolysis vapors was performed using a 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm DB5 column, with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. The GC inlet was set to 250 °C with a split ratio of 45:1. The oven was held at 40 °C for 1 min and then heated at 10 °C/min to a final temperature of 320 °C, where it was kept for 20 min. Mass spectra were acquired in electron ionization (EI) mode at 70 eV, with an m/z range of 40–550. The GC interface line and ion source temperatures were set to 150 and 230 °C, respectively. Peak identification was carried out using the NIST mass spectral library and relevant literature. Each analysis was carried out in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Temperature Variation of Non-Catalyzed Steam Explosion on the Raw Material

The composition of raw cardoon material was as follows: glucan 35.0 ± 2.3 wt%, xylan 14.0 ± 1.0 wt%, acetyl groups 1.9 ± 0.1 wt%, acid insoluble lignin 24.8 ± 1.4 wt%, acid soluble lignin 4.6 ± 0.5 wt%, ethanol-soluble extractives 4.1 ± 0.2 wt%, proteins 3.6 ± 0.1 wt% and ash 8.1 ± 0.3 wt%. Biomass composition is highly variable, influenced by factors such as variety, cultivation area, growth conditions, harvest time, and analytical methods. In the present work, the glucan content of residual cardoon was similar to that reported by Ballesteros et al. [36] and Cotana et al. [18], although it is 6–12 wt% lower than values reported by Fernandes et al. [19] and Lourenço et al. [20]. The lignin content in the lignocellulosic residue of cardoon shows considerable variability, with literature values ranging from 11.3 to 26.4 wt% [37], and is strongly affected by factors such as variety, cultivation area, growth conditions, and harvest time. Moreover, the perennial nature of cardoon may also contribute to these discrepancies [38]. Notably, the mass balance in the present study was 96.1%, whereas some studies reported values below 85 wt%, and many authors do not specify whether the reported lignin content includes the acid-soluble lignin fraction [39]. Overall, carbohydrates accounted for about 55 wt% of the biomass, with a sugar-to-lignin ratio greater than 2 wt/wt in most cases.

A temperature range of 180–220 °C for 5 min was initially explored to investigate the steam explosion effect without the use of any catalyst (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of the temperature of non-catalyzed steam explosion on the composition of water-insoluble fraction (WIF) and liquid fraction (LF).

With respect to the raw material composition, the water-insoluble fraction (WIF) showed a significant increase in glucan and lignin content, and a slight decrease in xylan content. This trend is due to the effect of high temperature, which leads to the hydrolysis of hemicelluloses and increases the xylan solubilization. The percentage of glucan in WIF increased from 46.8 wt% at 180 °C to 58.7 wt% at 200 °C and decreased to 50.9 wt% at 220 °C. The percentage of xylan in WIF decreased from 9.5 to 6.4 wt%, consistent with higher concentrations of xylose and xylo-oligomers in the LFs along with acetic acid and furans. The percentage of the acid-insoluble lignin in WIF increased from 23.6 to 30.8 wt%.

3.2. Effect of Catalysis on Biomass Pretreatment

H2SO4 and NaOH were selected as cheap and efficient homogeneous catalysts for the steam explosion pretreatment. Face-centered central composite design was used to describe the variation in responses as a function of temperature and catalyst concentration.

3.2.1. Effect of Acid Catalysis in Steam Explosion Pretreatment

Two response variables were examined: glucan hydrolysability (HY), namely glucose yield, and xylan recovery in the liquid fraction (XR) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of acid-catalyzed steam explosion carried out at different temperatures and soaking concentration of H2SO4 (from 0 to 50 mM) on glucose yield obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of glucan in the WIF (HYac), and xylan recovery (XRac) in the LF. Center points were replicated three times.

The glucose yield was determined by enzymatic hydrolysis of the solid fraction obtained from pretreatment, as described in the experimental section. Xylan recovery represents the percentage of solubilized xylose and xylo-oligomers in the liquid fraction relative to the total xylan content in the raw material, while residual insoluble lignin refers to the WIF remaining after hemicellulose removal. Based on the results reported in Table 3, acid catalysis increased the glucan hydrolysability at all investigated temperatures, with a maximum glucose yield of 83.2 mol% observed at 200 °C and 50 mM H2SO4 (run 10). The glucose yield was also close to 80 mol% with a lower concentration of catalyst (25 mM) at 200 °C (run 5).

On the contrary, a catalyst concentration of 50 mM is needed to obtain a higher xylan recovery (runs 9 and 10). However, at 220 °C, the xylan recovery dramatically decreased from 72.4 (run 10) to 25.7 mol% (run 11) due to the dehydration reaction of solubilized xylose to furfural.

3.2.2. Effect of Alkaline Catalysis on Cardoon Lignocellulosic Residues

The alkaline-catalyzed steam explosion favors the destructuration and solubilization of lignin, making the cellulose more accessible to enzymes during the subsequent saccharification process, and could enhance the solubilization of hemicellulose with different degrees of polymerization. A similar approach to that used for acid catalysis was employed to systematically investigate the impact of the NaOH catalyst in the steam explosion on the following digestibility of pretreated cardoon residue (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of base-catalyzed steam explosion carried out at different temperatures (from 180 to 220 °C) and different soaking concentrations of NaOH (from 0 to 50 mM) on glucose yield obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of glucan in the WIF (HYba) and xylan recovery (XRba) in LF. Center points were replicated three times.

Based on the results reported in Table 4, base catalysis increased the glucan hydrolysability at all investigated temperatures, with a maximum glucose yield of 82.8 mol% observed at 200 °C and 25 mM NaOH (run 5). The glucose yield was also higher than 80 mol% with a higher catalyst concentration (50 mM) at 200 °C (run 10), while at 220 °C, the glucose yield was slightly lower in the presence of either 25 or 50 mM NaOH (runs 8 and 11).

The data show that basic catalysis negatively affects xylan recovery (XRba). Samples treated without NaOH exhibited higher xylan recovery values (up to about 50 mol%), whereas the addition of NaOH at 25 or 50 mM significantly reduces xylan recovery, with values dropping as low as 10–35 mol%. Although higher thermal severity typically promotes xylan solubilization, the increase in pH due to NaOH addition counteracts this effect. Consequently, the alkaline conditions reduce xylan removal, leading to greater retention of xylan within the solid fiber fraction.

3.2.3. Effect of Catalysts Adopted in the Steam Explosion on the Solid Fraction

Data reported in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that the highest experimental hydrolysis yields were 83.2 (run 10, Table 3) and 82.8 mol% (run 5, Table 4) for acid and base catalysis, respectively. These results were obtained at 200 °C with an impregnation of 50 mM H2SO4 and 25 mM NaOH. The results indicate that both catalytic approaches were very efficient in increasing enzymatic access to glucan in the following saccharification step. Under the same steam explosion conditions without the catalyst, the glucose yield in the enzymatic hydrolysis reaction was 73.5 mol%, which is about 10 mol% lower than the glucose yields achieved by carrying out the catalyzed steam explosion. These results confirmed the significant impact of acid or base catalysis in the steam explosion pretreatment of cardoon mixed residues. The appendix data report the trends of cellulose enzymatic hydrolysis under each investigated condition (Figure S1, Supplementary File).

In the case of H2SO4-catalysed steam explosion, the obtained glucose yields were slightly higher than those reported in the literature. Ballesteros et al. [23] obtained 80.2 mol% glucose in a batch bioreactor (24 FPU/g glucan, 72 h) after steam explosion at 200 °C for 10 min with 0.2 wt% H2SO4, while Cotana et al. [18] reported a similar yield of 80 mol% using steam explosion at 220 °C for 10 min followed by enzymatic hydrolysis during the SHF process (30 FPU/g glucan, 48 h at 50 °C and 96 h at 32 °C). Slightly lower yields were obtained by Fernandes et al. [19], who achieved 72.8 mol% after steam explosion at 200 °C for 8 min, lignin alkali extraction (2% NaOH, 15 min, 5% biomass loading), and enzymatic hydrolysis (21 FPU/g glucan, 72 h). Bertini et al. [8] reported a glucose yield of ~70 mol% after steam explosion at 175 °C for 35 min followed by enzymatic hydrolysis (0.3 g enzyme/g cellulose, 5% biomass loading, 72 h), whereas Gelosia et al. [7] reached ~90 mol% using a microwave-assisted reactor at 150 °C with 1.96% acid, 1 wt% solids, and 0.3 g enzyme/g glucan, though under non-scalable and unsustainable conditions. Compared to these studies, our H2SO4-catalysed steam explosion process slightly improves glucose yield while using higher biomass loading and lower enzyme dosage, making it more sustainable and industrially scalable.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated NaOH-catalyzed steam explosion of cardoon biomass, highlighting the novelty of this work in second-generation biorefinery and lignocellulosic conversion. Previous studies on base-catalyzed steam explosion with other biomasses have shown that each feedstock requires tailored process conditions for efficient fractionation and enzymatic conversion. For example, Park et al. [40] reported 65.5 mol% sugar from Eucalyptus (NaOH-catalyzed, 210 °C, 9 min, 30 FPU/g glucan, 5% biomass, 72 h), while Choi et al. [41] achieved 93 mol% glucan recovery and 88.8 mol% digestibility on empty fruit bunches (40 FPU/g glucan, 2% solids, 72 h) using nearly three times more enzyme than in the present study. Mihiretu et al. [42] obtained 92 mol% cellulose digestibility for sugarcane and 81 mol% for aspen wood using NaOH-impregnated steam explosion (204 °C, 10 min, 4.8 wt% NaOH, 25 FPU/g glucan, 72 h), while simultaneously extracting xylan-rich biopolymers.

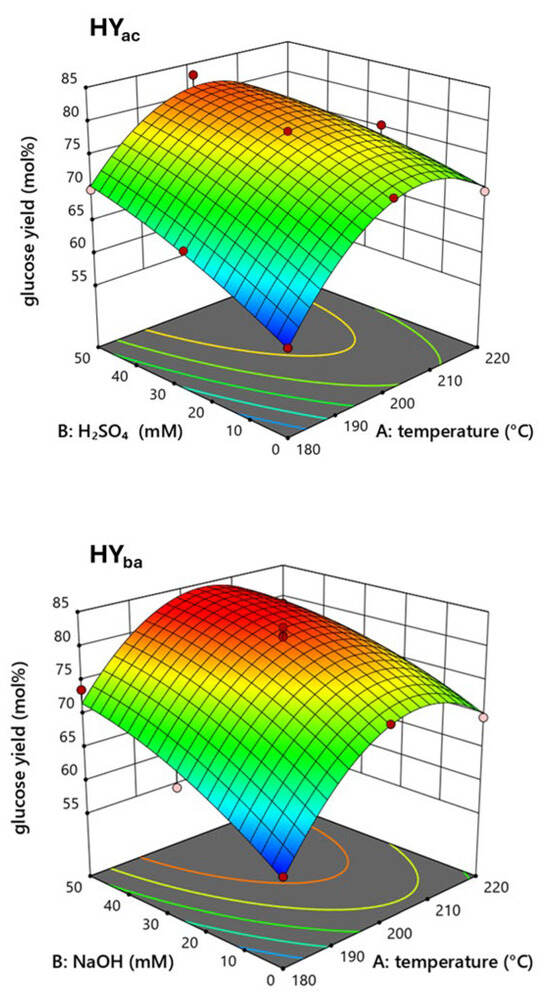

Figure 1 shows the response surfaces for the optimization of steam explosion parameters with H2SO4 and NaOH as catalysts as a function of glucose yield in the saccharification processing of each pretreated solid fraction.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional response surface of glucose yield from enzymatic hydrolysis of steam exploded cardoon residue in the presence of acid (HYac) or alkaline catalysis (HYba).

The surfaces reported in Figure 1 were described by quadratic Equations (4) and (5) in terms of actual factors:

where A and B are the temperature in Celsius degrees and the catalyst concentration in mM. These equations, expressed in terms of actual factors, can be used to predict the response for given values of each factor. The statistical evaluation was conducted using ANOVA, and the coefficients of the final equation, expressed in terms of coded factors, were provided in the Supplementary File (Table S1).

HYac = −888.38 + 9.31 × A + 1.10 × B − 0.0041 × AB − 0.022 × A2 − 0.0002 × B2

HYba = −933.64 + 9.76 × A + 1.033 × B − 0.0032 × AB − 0.024 × A2 − 0.0035 × B2

3.2.4. Effect of the Catalyst on the Chemical Composition of the Liquid Fraction

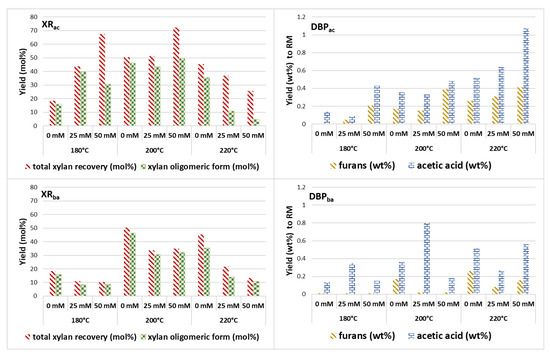

Figure 2 details the effect of the type of catalysis adopted in the steam explosion treatment of cardoon on the distribution of solubilized xylose recovery (XR) and the dehydration by-products (DBP) in the hemicellulose liquid fraction.

Figure 2.

The impact of the acid catalysis on xylan recovery yield (panel XRac) and on the dehydration by-product formation (panel DBPac) in the liquid fractions compared with the xylan distribution (panel XRba) and dehydration by-product formation (panel DBPba) resulted from the effect of base catalysis. XR was the yield determined with respect to the initial xylan in the raw material, while DBP was calculated with respect to dry raw material (wt% to RM).

In Figure 2 (panel XRac), it can be observed that acid catalysis promotes the recovery of xylan from biomass in pretreatments carried out at 180 °C, whereas it has a detrimental effect at higher temperatures, specifically at 220 °C. The thermal capacity to solubilize pentoses is enhanced by catalytic activity, which leads to the degradation of furans and acetic compounds (panel DBPac). Xylan in the raw material can be solubilized either as soluble monomers or oligomers. While the xylose monomer can be subsequently transformed into biobased molecules for the chemical industry [43,44], the xylo-oligomers are highly valued by the nutraceutical industry as food additives and prebiotics [45]. Furthermore, polysaccharide-based packaging films have been preliminarily applied in food packaging. While the use of hemicellulose films is still in the research phase, their excellent barrier properties position them as a promising alternative to plastic films, especially in applications where mechanical strength is not a primary concern [46]. On the other hand, xylo-oligomers are known as strong inhibitors of the enzymes involved in the hydrolysis of cellulose; therefore, the production of mixed hydrolysates from xylo-oligomer-rich hemicelluloses is strongly discouraged [47]. The combination of parameters that ensures a recovery of approximately 70 mol% of xylan was achieved by impregnating the biomass with 50 mM H2SO4 at 180 °C and 200 °C. Specifically, the latter process parameter allowed for the recovery of around 50 mol% of the initial xylan present in the raw material as soluble xylo-oligomers. The pretreatment carried out at 200 °C without a catalyst allowed a xylo-oligomer recovery of more than 45 mol%, but with approximately 20 mol% fewer monomers due to the absence of acid. Hemicelluloses with relative yields of monomeric xylose higher than 80 mol% were obtained when, in addition to the acid concentration, the highest temperature (220 °C) was combined, which favored the thermal autohydrolysis of the oligomers. On the other hand, with these high thermal severities, the recovery yields of the total xylan were lower because part of the sugar is degraded to by-products, and in particular to furan compounds (mainly furaldehyde and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural). The solubilization of acetyl groups also increased as a function of the increase in process severity. Ballesteros et al. [36] indicated the temperature of 180 °C as the optimal one to maximize the xylan recovery yield, reaching a 13.5 mol% recovery, which is a value similar to that achieved in the present study (9.5 mol%). However, a 2-litre stirred reactor and different acid concentrations were used in the cited work. Acid-catalyzed steam explosion was used for cardoon fractionation by Bertini et al. [8], by soaking in a 1 wt% H2SO4 solution, pretreatment temperatures between 160 and 190 °C and a longer residence time, corresponding to 35 min. A maximum recovery yield of around 60 mol% was obtained, approximately 10 mol% lower than that obtained in this work with the combination of parameters described above.

Regarding the base-catalyzed approach, at high temperatures and NaOH concentrations, there was a decrease in total xylan recovery and an increase in the percentage of xylan in the oligomeric form (Figure 2, panel XRba). The amount of furanic compounds produced by basic catalysis (Figure 2, panel DBPba) was typically negligible compared to acid catalysis since the dehydration reaction of glucose and xylose to 5-HMF and furfural, respectively, is catalyzed by Brønsted acidity. However, an increase in acetic acid production was observed at higher temperatures and NaOH concentrations. The use of NaOH for lignin removal has been shown to induce the release of acetyl groups and uronic acid substituents, which can improve the digestibility of cellulose and hemicellulose [48,49]. Nevertheless, some of these degradation products, including xylo-oligomers [47], phenols, organic acids [50], furfural, and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural [51], can inhibit the activity of hydrolytic enzymes, underscoring the critical importance of optimizing process conditions, such as alkaline loading, moisture content, temperature, and reaction time, to minimize such inhibition [52].

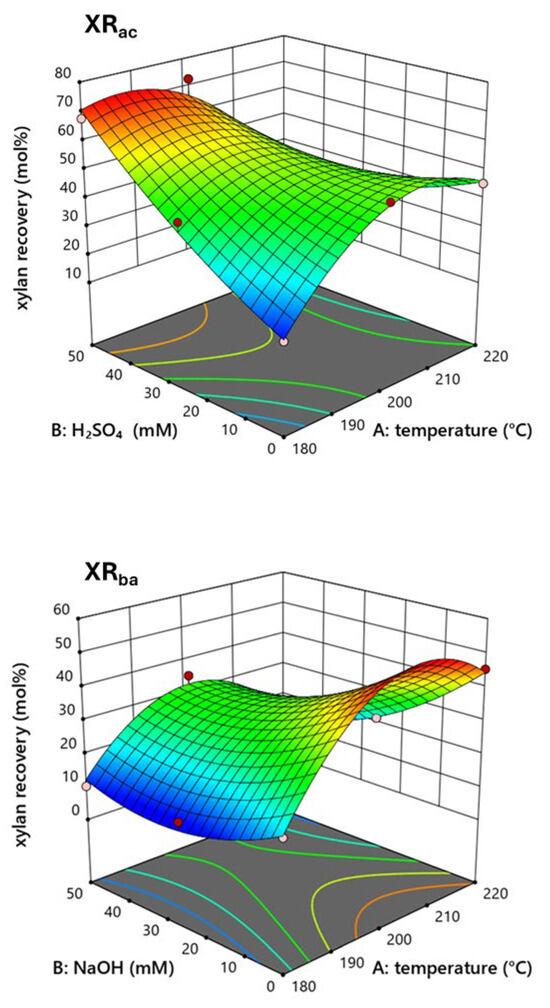

These findings indicate that the treatment conditions can significantly impact the composition of the biomass, which has important implications for its potential applications. On one hand, acid catalysis promotes the recovery of xylan from the lignocellulosic matrix and, at higher thermal severities, allows for the production of mainly monomeric sugars. On the other hand, it inevitably leads to the formation of furanic degradation by-products. In contrast, basic catalysis reduces the recovery of xylan in the liquid fraction and increases the formation of xylo-oligomers and acetic acid. The impact of acid and alkaline catalysis on the xylose recovery in the liquid fraction of pretreated cardoon was also investigated by creating 3D response surfaces (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional response surfaces of xylan recovery (mol%) of pretreated cardoon after acid catalysis (XRac) and alkaline catalysis (XRba).

The effects of temperature and catalyst on the response variable were also statistically analyzed using analysis of variance (Supplementary File, Table S2).

3.3. Optimization of the Catalysis-Driven Steam Explosion Parameters

The section dedicated to optimizing results in the DesignExpert10® software allows for determining the combination of parameters within the working range to achieve the desired objectives.

3.3.1. Optimization of Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion Coupled with Enzymatic Saccharification

A combination of parameters capable of maximizing the yield of glucan hydrolysability was analyzed (desired variable HYac). The values reported in Table 5 show that operating at 202 °C and with 50 mM of H2SO4 impregnation, the glucan hydrolysis yield was higher than 80 mol%. In contrast, the combination of parameters capable of maximizing the xylan recovery into the liquid fraction was elaborated (desired variable XRac), and the maximum predicted value was 72.7 mol% at 187.8 °C and 50 mM of H2SO4. Finally, the optimal combination of parameters to maximize both glucose and xylose was determined. The optimization study predicted a glucose yield and a xylan recovery yield of approximately 80.5 and 70.3 mol%, respectively, by working at 196 °C and 50 mM H2SO4, corresponding to a desirability of 0.926. Desirability is an objective function that varies from 0 (meaning outside the specified limits) to 1 (the desired goal). Numerical optimization seeks to identify a point that maximizes this desirability function, guiding the process toward the optimal outcome. The predicted conditions were validated, together with the model and equations shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3, and the experimental results were similar to those predicted with less than 5% deviation. In this optimized condition of pretreated cardoon at 196 °C with 50 mM of acid impregnation, the measured combined severity factor (CSF) was 9.14. The software prediction and experimental results of model validation were reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Optimization of sugar recovery (glucan hydrolysis, namely glucose yield, and xylan recovery) in the saccharification process after acid-catalyzed steam explosion.

3.3.2. Optimization of Base-Catalyzed Steam Explosion Coupled with Enzymatic Saccharification

The same optimization study was carried out for the alkaline catalytic approach, and the main results were reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Optimization of results on sugar recovery (cellulose hydrolysis yield and xylan recovery) after base-catalyzed experimental campaign. The combination of parameters of predicted results was validated by the experimental results and their desirability.

The optimal reaction conditions for maximizing glucan enzymatic hydrolysis after alkaline-catalyzed steam explosion were 204.1 °C and 39.4 mM NaOH, yielding 83.7 mol% glucose. The model predicted that a combination of 209.5 °C and 0.5 mM NaOH would maximize the xylose yield (52.1 mol%) in the liquid fraction collected after steam explosion. To maximize both responses, pretreatment at 205.4 °C with NaOH impregnation at 13.2 mM was assessed. The results of the experimental tests confirmed the predictions with an error margin of 5%. Generally, when the objective is to maximize glucose yield, pretreatment at 204.1 °C with 39.4 mM NaOH is preferable. However, in processes where both glucose and xylose need to be valorized (e.g., co-fermentation), working with a NaOH concentration around three times lower is more effective. The contour plots of the desirability of the responses of the numerical optimization after the acid-catalyzed and base-catalyzed steam explosion are reported in the Supplementary File (Figure S2).

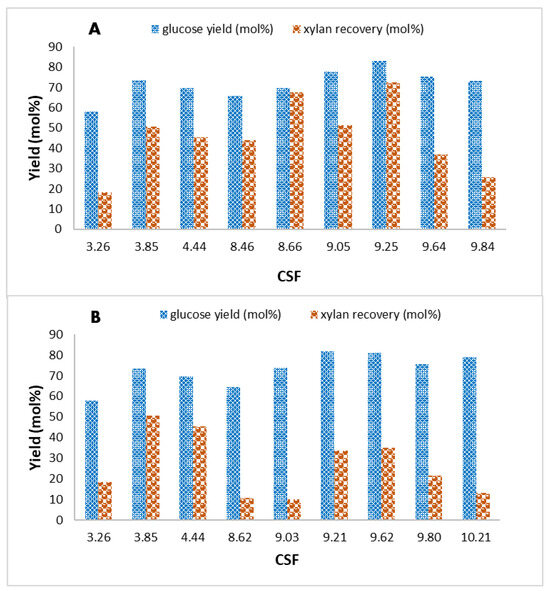

3.4. The Role of the Combined Severity Factor in Balancing Glucan Hydrolysis and Xylan Recovery

The CSF is a key metric for integrating process parameters, such as temperature and pH post-impregnation (see Section 2.5 in the Materials and Methods section). It combines these variables into a single metric to provide a measure of pretreatment severity, helping to evaluate the effect of catalyzed and non-catalyzed steam explosion on biomass deconstruction, particularly regarding enzymatic hydrolysis yield and xylan recovery (Figure 4). The pH values used for the CSF calculation were provided in Table S3 of the Supplementary File, which also included the pH of the slurry after pretreatment to highlight the effect of acetyl group cleavage on the pH of the resulting slurry. Despite its utility, the relationship between CSF and the process outcomes is not strictly linear, illustrating the challenge of balancing cellulose conversion with hemicellulose preservation.

Figure 4.

Effect of the CSF on glucose yield (mol%) after the enzymatic saccharification process and xylan recovery (mol%) under acidic (A) and basic (B) catalysis adopted in the steam explosion treatment of cardoon residue.

In the case of acid-catalyzed steam explosion (Figure 4A), increasing CSF enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis yields while progressively compromising xylan recovery. For instance, at 200 °C and 25 mM H2SO4, the CSF was 9.05, yielding 77.7 mol% glucose yield and 51.4 mol% xylan recovery. This moderate severity effectively balances glucan conversion with hemicellulose preservation. However, higher severity levels—as indicated by a CSF of 9.84 at 220 °C and 50 mM H2SO4—resulted in decreased xylan recovery (25.7 mol%) despite a further increase in hydrolysis yield (83.2 mol%). These results underscore the need to optimize pretreatment conditions to avoid excessive degradation of hemicellulose due to the dehydration reaction, which is particularly sensitive to high severity levels.

In base-catalyzed pretreatments (Figure 4B), similar trends were observed. A CSF of 9.21, achieved at 200 °C and 25 mM NaOH, corresponded to the highest glucan digestibility and glucose yield (81.9 mol%) achieved in the present study. However, xylan recovery was significantly lower (33.6 mol%) compared to acid-catalyzed conditions. At the highest CSF value of 10.21 (at 220 °C and 50 mM NaOH), glucose yield was high (78.9 mol%), but xylan recovery dropped sharply to 13.3 mol%. These findings highlight a key limitation of alkaline conditions: they are effective for glucan conversion in the saccharification process but are considerably less favorable for hemicellulose retention. The utility and limitations of CSF have been widely discussed in the context of lignocellulosic pretreatment. For example, while CSF was originally developed for acidic or neutral conditions, Chum et al. [53] extended its application to basic environments by proposing severity factors that integrate the pH variable to describe the effects of temperature and time on biomass deconstruction, thereby offering a more nuanced perspective on catalytic pretreatments. However, as observed in both acidic and alkaline conditions, CSF alone does not capture all nuances of biomass deconstruction, particularly under basic pH conditions where side reactions and hemicellulose solubilization complicate the analysis. While this study successfully identified moderate CSF values (around 9.0–9.2) as optimal for balancing the efficiency of glucan hydrolysis and xylan preservation, it also reveals significant trade-offs inherent to base catalysis. These findings emphasize the need for further research into alternative metrics or complementary analyses to better understand the effects of alkaline conditions on hemicellulose degradation. Additionally, exploring higher catalyst concentrations and broader pH ranges could provide valuable insights into optimizing both cellulose and hemicellulose exploitation. Despite the promising results, CSF shows a highly non-linear relationship with pH, and small changes in operational conditions can significantly affect enzymatic digestibility. The results were obtained using a specific 10 L-scale steam explosion reactor, so differences in reactor design or biomass loading could alter outcomes. Moreover, this study focused on cardoon residues, and further optimization would be needed to apply the approach to other lignocellulosic biomasses. In conclusion, CSF remains a valuable tool for process optimization, particularly when used alongside other metrics to guide pretreatment strategies. This study contributes to a broader understanding of lignocellulosic biomass valorization, with implications for producing bio-based platform chemicals via sugar fermentation and developing lignin-based materials.

3.5. Impact of Catalyzed-Steam Explosion on the Chemical Composition of Isolated Cardoon Lignin

Isolated lignins extracted before and after steam explosion treatments, performed under the previously optimized conditions, were analyzed using pyrolysis coupled with a gas chromatography/mass spectrometry system (Py-GC/MS). This technique was chosen because it provides detailed insights into lignin’s structural motifs by identifying pyrolysis products from phenylpropane units. According to the literature, Py-GC/MS is a widely used method for evaluating S/G ratios due to its sensitivity and reproducibility in detecting syringyl (S) and guaiacyl (G) units [54]. Table 7 summarizes the key structural motifs identified as pyrolysis products during lignin chromatographic analysis, which can be attributed to the three main alcohol types: coniferyl alcohol (G), sinapyl alcohol (S), and coumaryl alcohol (H), each derived from phenylpropane units. The internal ratio between S and G units is particularly important as it provides valuable insights into lignin recalcitrance and its potential for subsequent conversion and valorization.

Table 7.

Structural determination via Py-GC/MS of the most abundant lignin-derived molecules from lignin extracted from untreated cardoon (namely lignin before steam explosion). Alcohol groups classification: coniferyl alcohol (G), sinapyl alcohol (S), and coumaryl alcohol (H).

The characterization of cardoon lignin focused on its chemical and structural properties, with particular emphasis on the S/G ratio as a predictor of lignin reactivity. Lignins with high S/G ratios, rich in syringyl units, are generally less cross-linked and more reactive, making them suitable for chemical conversions. Conversely, guaiacyl-rich lignins tend to form more condensed structures due to C-C (5-5) covalent bonds, which reduce their reactivity. These trends have been confirmed by other literature studies [55,56], highlighting the industrial relevance of optimizing S/G ratios for specific applications of lignin-based materials.

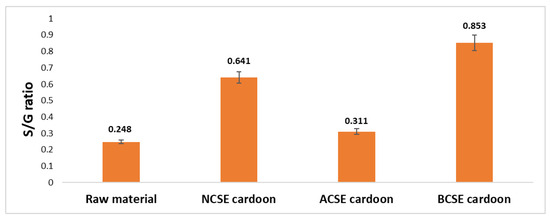

The S/G values determined for each sample, namely lignin from untreated raw material, non-catalyzed steam explosion (NCSE), acid-catalyzed steam explosion (ACSE), and base-catalyzed steam explosion (BCSE), were reported in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the syringyl/guaiacyl (S/G) ratio of lignin extracted from raw cardoon biomass and under different process conditions of steam explosion. NCSE: non-catalyzed steam explosion; ACSE: acid-catalyzed steam explosion; BCSE: base-catalyzed steam explosion.

According to the literature, the S/G ratio is widely recognized as a key parameter for lignin structural composition and reactivity, affecting its suitability for downstream biotechnological and industrial applications. The raw cardoon lignin exhibits a relatively low S/G ratio of 0.248, indicating a higher proportion of guaiacyl units compared to syringyl units. This composition is consistent with previous studies on lignocellulosic biomasses, such as eucalyptus and sugarcane bagasse, where guaiacyl units dominate [57]. The guaiacyl-rich structure forms a condensed lignin network, which poses challenges for chemical valorization. The non-catalyzed steam explosion significantly increases the S/G ratio to 0.641, suggesting a substantial shift in the lignin composition toward a higher syringyl content. This shift likely results from the selective breakdown of guaiacyl units under thermal and mechanical forces, as demonstrated by Sun et al. [58]. The enhanced syringyl content improves lignin reactivity, making it more suitable for producing bio-based chemicals or materials. The acid-catalyzed steam explosion yields an S/G ratio of 0.311, significantly lower than that of the NCSE. Acidic conditions can lead to lignin condensation, particularly among guaiacyl units, which reduces the syringyl content and increases cross-linking. This aligns with observations by Wang et al. [59], indicating that acid-catalyzed lignins may be less reactive but more thermally stable, making them ideal for the production of carbonaceous materials. The base-catalyzed steam explosion results in the highest S/G ratio of 0.853, indicating a pronounced enrichment of syringyl units. Alkaline conditions are well-documented for selectively breaking guaiacyl linkages while preserving syringyl units [55]. The high S/G ratio obtained under BCSE suggests a more linear and less cross-linked lignin structure, which is advantageous for producing biopolymers, adhesives, and aromatic chemicals. Differences in S/G ratios across the three pretreatments highlight the need to tailor lignin isolation methods to the intended applications. These findings demonstrate that lignin with a high S/G ratio, such as that obtained through base-catalyzed steam explosion under the optimized process conditions, is ideal for applications requiring high reactivity and lower cross-linking. Conversely, lignin with a lower S/G ratio, like that from acid-catalyzed pretreatment, may be more suited for thermally stable applications [60]. This study contributes to the increasing research highlighting the important role of pretreatment conditions in determining the potential structure and usability of lignin.

4. Conclusions

A face-centered composite design was used to optimize the fractionation of cardoon biomass via acid or base-catalyzed steam explosion, varying temperature and catalyst concentration. H2SO4 catalysis significantly improved cellulose hydrolysis and glucose yield in the saccharification process carried out on the pretreated biomass, achieving a value of 78 mol% at 200 °C and 25 mM H2SO4. Xylan recovery required a 50 mM catalyst concentration but dropped at 220 °C due to thermal degradation. Base catalysis at 200 °C and 25 mM NaOH also increased cellulose hydrolysability but reduced xylan recovery. Optimal glucose yield of around 83 mol% was achieved in enzymatic hydrolysis after a steam explosion carried out at 200 °C and 50 mM acid or 200 °C and 25 mM NaOH. Acid catalysis enhanced xylan recovery, mainly as xylose monomers, while basic catalysis favored the production of xylo-oligomers. The relevance of each outcome depends on the intended biorefinery pathway: xylan recovery is advantageous when high-purity monomeric hemicellulosic fractions are required for material or chemical applications, whereas xylo-oligomers represent valuable intermediates for prebiotic, nutraceutical, or biochemical markets. Therefore, both catalytic approaches offer benefits, but for different product value chains. The optimal conditions for maximizing sugar yields were 196 °C and 50 mM H2SO4, resulting in a glucose yield of around 80 mol% and a xylan recovery of 70 mol%. Base catalyst optimization indicated 204 °C and 39.4 mM NaOH for glucose recovery and 205 °C and 13.2 mM NaOH for both glucose and xylose coproduction. This study provides key insights into optimizing cardoon biomass fractionation using acid- or base-catalyzed steam explosion. In both acid and base catalysis, moderate CSF values (approximately 9.0–9.2) represented the optimal balance between cellulose hydrolysis efficiency and xylan retention. In base catalysis, higher CSF values further enhance cellulose conversion but significantly reduce xylan recovery; however, the increased syringyl content in base-catalyzed lignins creates new opportunities for their use in high-value chemical sectors, which are progressively focusing on lignin valorization to meet sustainability objectives. Future work should focus on scaling up enzymatic hydrolysis at higher solid loadings to achieve higher sugar concentrations, enabling more economically viable biorefinery processes. In parallel, further research is needed to deepen the understanding of lignin structure and properties, particularly under base-catalyzed conditions, to enhance its valorization and fully exploit the potential of the entire biomass. These efforts will contribute to developing more efficient and sustainable strategies for second-generation biorefineries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123926/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L., K.Z., A.C. and I.D.B.; Methodology, F.L., N.D.F. and A.C.; Software, K.Z. and A.C.; Validation, F.L., N.D.F., K.Z. and E.V.; Formal analysis, F.L. and E.B.; Investigation, K.Z.; Resources, E.V. and I.D.B.; Data curation, N.D.F., E.B. and I.D.B.; Writing—original draft, F.L. and E.B.; Writing—review and editing, F.L., N.D.F., A.C. and I.D.B.; Visualization, I.D.B.; Supervision, E.B., E.V. and I.D.B.; Funding acquisition, I.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

N.D.F. thanks the colleagues of ENEA Trisaia Research Centre for the hospitality in their laboratories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Neri, U.; Pennelli, B.; Simonetti, G.; Francaviglia, R. Biomass partition and productive aptitude of wild and cultivated cardoon genotypes (Cynara cardunculus L.) in a marginal land of Central Italy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gominho, J.; Curt, M.D.; Lourenço, A.; Fernández, J.; Pereira, H. Cynara cardunculus L. as a biomass and multi-purpose crop: A review of 30 years of research. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 109, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Breso, A.; Rúa, F.; Volpe, M.L.; Leskovar, D.; Cravero, V. Biomass characterization of wild and cultivated cardoon accessions and estimation of potential biofuels production. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 28661–28671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, A.; De Caro, P.; Thiebaud--Roux, S.; Vedrenne, E.; Mouloungui, Z. New Environmentally Friendly Oxidative Scission of Oleic Acid into Azelaic Acid and Pelargonic Acid. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, A.; Chiappetta, A.; Araniti, F.; Muzzalupo, I.; Marrelli, M.; Conforti, F.; Schettino, A.; Cozza, R.; Bitonti, M.B.; Bruno, L. Genetic, metabolic and antioxidant differences among three different Calabrian populations of Cynara cardunculus subsp. Cardunculus. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2021, 155, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, I.; Borselleca, E.; Poggetto, G.D.; Staiano, I.; Alfieri, M.L.; Pezzella, C. Exploitation of cardoon roots inulin for polyhydroxyalkanoate production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelosia, M.; Bertini, A.; Barbanera, M.; Giannoni, T.; Nicolini, A.; Cotana, F.; Cavalaglio, G. Acid-Assisted Organosolv Pre-Treatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cynara cardunculus L. for Glucose Production. Energies 2020, 13, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, A.; Gelosia, M.; Cavalaglio, G.; Barbanera, M.; Giannoni, T.; Tasselli, G.; Nicolini, A.; Cotana, F. Production of Carbohydrates from Cardoon Pre-Treated by Acid-Catalyzed Steam Explosion and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Energies 2019, 12, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Alfano, V.; Stefanoni, W.; Latterini, F.; Liuzzi, F.; De Bari, I.; Valerio, V.; Ciancolini, A. Inulin Content in Chipped and Whole Roots of Cardoon after Six Months Storage under Natural Conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orsi, R.; Di Fidio, N.; Antonetti, C.; Galletti, A.M.R.; Operamolla, A. Isolation of Pure Lignin and Highly Digestible Cellulose from Defatted and Steam-Exploded Cynara cardunculus. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporusso, A.; De Bari, I.; Valerio, V.; Albergo, R.; Liuzzi, F. Conversion of cardoon crop residues into single cell oils by Lipomyces tetrasporus and Cutaneotrichosporon curvatus: Process optimizations to overcome the microbial inhibition of lignocellulosic hydrolysates. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 159, 113030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, A.M.R.; Licursi, D.; Ciorba, S.; Di Fidio, N.; Coccia, V.; Cotana, F.; Antonetti, C. Sustainable Exploitation of Residual Cynara cardunculus L. to Levulinic Acid and n-Butyl Levulinate. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalaglio, G.; Gelosia, M.; Giannoni, T.; Temporim, R.B.L.; Nicolini, A.; Cotana, F.; Bertini, A. Acid-catalyzed steam explosion for high enzymatic saccharification and low inhibitor release from lignocellulosic cardoon stalks. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 174, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapini, T.; Santos, M.S.N.D.; Bonatto, C.; Wancura, J.H.C.; Mulinari, J.; Camargo, A.F.; Klanovicz, N.; Zabot, G.L.; Tres, M.V.; Fongaro, G.; et al. Hydrothermal pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for hemicellulose recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 342, 126033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, F.; Mastrolitti, S.; De Bari, I. Hydrolysis of Corn Stover by Talaromyces cellulolyticus Enzymes: Evaluation of the Residual Enzymes Activities Through the Process. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 188, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crognale, S.; Liuzzi, F.; D’Annibale, A.; de Bari, I.; Petruccioli, M. Cynara cardunculus a novel substrate for solid-state production of Aspergillus tubingensis cellulases and sugar hydrolysates. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 127, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, X.; Lau, A.; Rezaei, H.; Takada, M.; Bi, X.; Sokhansanj, S. Steam explosion of lignocellulosic biomass for multiple advanced bioenergy processes: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotana, F.; Cavalaglio, G.; Gelosia, M.; Coccia, V.; Petrozzi, A.; Ingles, D.; Pompili, E. A comparison between SHF and SSSF processes from cardoon for ethanol production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 69, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Ferro, M.D.; Paulino, A.F.C.; Mendes, J.A.S.; Gravitis, J.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Xavier, A.M.R.B. Enzymatic saccharification and bioethanol production from Cynara cardunculus pretreated by steam explosion. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 186, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A.; Gominho, J.; Curt, M.D.; Revilla, E.; Villar, J.C.; Pereira, H. Steam Explosion as a Pretreatment of Cynara cardunculus Prior to Delignification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, P.; Ladero, M.; García-Ochoa, F.; Villar, J.C. Valorization of Cynara cardunculus crops by ethanol-water treatment: Optimization of operating conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, T.H. A review on alkaline pretreatment technology for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, I.; Ballesteros, M.; Manzanares, P.; Negro, M.J.; Oliva, J.M.; Sáez, F. Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of cardoon for ethanol production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Suhag, M.; Dhaka, A. Augmented digestion of lignocellulose by steam explosion, acid and alkaline pretreatment methods: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fidio, N.; Timmermans, J.W.; Antonetti, C.; Galletti, A.M.R.; Gosselink, R.J.A.; Bisselink, R.J.M.; Slaghek, T.M. Electro-oxidative depolymerisation of technical lignin in water using platinum, nickel oxide hydroxide and graphite electrodes. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9647–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsella, E.; De Bari, I.; Colucci, P.; Mastrolitti, S.; Liuzzi, F.; De Stefanis, A.; Valentini, V.; Gallese, F.; Perez, G. Lignin Depolymerization by Catalytic Hydrodeoxygenation Performed with Smectitic Clay-Based Materials. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 2000633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fidio, N.; Liuzzi, F.; Mastrolitti, S.; Albergo, R.; De Bari, I. Single Cell Oil Production from Undetoxified Arundo donax L. hydrolysate by Cutaneotrichosporon curvatus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J.; Giuliano, A.; Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Hulteberg, C.P.; Koutinas, A.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Barletta, D.; De Bari, I. Techno-economic optimization of a process superstructure for lignin valorization. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D.L. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Lab. Anal. Proced. 2008, 1617, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose, T.K. Measurement of cellulase activities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1987, 59, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, N.; Chornet, E.; Belkacemi, K.; Overend, R.P. Phenomenological kinetics of complex systems: The development of a generalized severity parameter and its application to lignocellulosics fractionation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.; Meyer, A.S. Lignocellulose pretreatment severity—Relating pH to biomatrix opening. New Biotechnol. 2010, 27, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaafouri, K.; Ziadi, M.; Hassen-Trabelsi, A.B.; Mekni, S.; Aïssi, B.; Alaya, M.; Bergaoui, L.; Hamdi, M. Optimization of Hydrothermal and Diluted Acid Pretreatments of Tunisian Luffa cylindrica (L.) Fibers for 2G Bioethanol Production through the Cubic Central Composite Experimental Design CCD: Response Surface Methodology. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9524521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A.; Rencoret, J.; Chemetova, C.; Gominho, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Pereira, H.; del Río, J.C. Isolation and Structural Characterization of Lignin from Cardoon (Cynara cardunculus L.) Stalks. Bioenergy Res. 2015, 8, 1946–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y. Lignin biorefinery: Lignin source, isolation, characterization, and bioconversion. Adv. Bioenergy 2022, 7, 211–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M.; Negro, M.J.; Manzanares, P.; Ballesteros, I.; Sáez, F.; Oliva, J.M. Fractionation of Cynara cardunculus (Cardoon) Biomass by Dilute-Acid Pretreatment. In Applied Biochemistry and Biotecnology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligero, P.; Villaverde, J.J.; Vega, A.; Bao, M. Acetosolv delignification of depithed cardoon (Cynara cardunculus) stalks. Ind. Crops Prod. 2007, 25, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencoret, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Nieto, L.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; Faulds, C.B.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J.; Martínez, Á.T.; del Río, J.C. Lignin composition and structure in young versus adult eucalyptus globulus plants. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoni, T.; Gelosia, M.; Bertini, A.; Fabbrizi, G.; Nicolini, A.; Coccia, V.; Iodice, P.; Cavalaglio, G. Fractionation of Cynara cardunculus L. By acidified organosolv treatment for the extraction of highly digestible cellulose and technical lignin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Kang, M.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, J.-P.; Choi, W.-I.; Lee, J.-S. Enhancement of enzymatic digestibility of Eucalyptus grandis pretreated by NaOH catalyzed steam explosion. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 123, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-I.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-P.; Oh, Y.-K.; Park, Y.C.; Kim, J.S.; Park, J.M.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, J.-S. Optimization of NaOH-catalyzed steam pretreatment of empty fruit bunch. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihiretu, G.T.; Chimphango, A.F.; Görgens, J.F. Steam explosion pre-treatment of alkali-impregnated lignocelluloses for hemicelluloses extraction and improved digestibility. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 294, 122121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Eronen, A.; Vasko, P.; Du, X.; Install, J.; Repo, T. Near quantitative conversion of xylose into bisfuran. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5052–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Nandanwar, S.U.; Niphadkar, P.; Simakova, I.; Bokade, V. Maximization of furanic compounds formation by dehydration and hydrogenation of xylose in one step over SO3–H functionalized H-β catalyst in alcohol media. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 139, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ajuwon, K.M.; Zhong, R.; Li, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Beckers, Y.; Everaert, N. Xylo-Oligosaccharides, Preparation and Application to Human and Animal Health: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 731930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Weng, Y. Hemicellulose-Based Film: Potential Green Films for Food Packaging. Polymers 2020, 12, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Q.; Yang, B.; Wyman, C.E. Xylooligomers are strong inhibitors of cellulose hydrolysis by enzymes. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 9624–9630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.K.; Sharma, S. Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y. Liquid hot water and alkaline pretreatment of soybean straw for improving cellulose digestibility. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6254–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ximenes, E.; Mosier, N.S.; Ladisch, M.R. Soluble inhibitors/deactivators of cellulase enzymes from lignocellulosic biomass. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2011, 48, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, S.I.; den Haan, R.; Viljoen-Bloom, M.; van Zyl, W.H. Lignocellulosic hydrolysate inhibitors selectively inhibit/deactivate cellulase performance. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2015, 81, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modenbach, A.A.; Nokes, S.E. Effects of Sodium Hydroxide Pretreatment on Structural Components of Biomass. Trans. ASABE 2014, 57, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, H.L.; Johnson, D.K.; Black, S.K.; Overend, R.P. Pretreatment-Catalyst effects and the combined severity parameter. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1990, 24–25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, D.D.; Ke, J.; Zeng, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, S. Py-GC/MS as a Powerful and Rapid Tool for Determining Lignin Compositional and Structural Changes in Biological Processes. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2013, 9, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, S.-J.; Zhong, C.; Li, B.-Z.; Yuan, Y.-J. Alkali-Based Pretreatment-Facilitated Lignin Valorization: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 16923–16938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, T.; Wang, G.; Sun, H.; Sui, W.; Si, C. Lignin fractionation: Effective strategy to reduce molecule weight dependent heterogeneity for upgraded lignin valorization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 165, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Purkait, M.K. Lignocellulosic conversion into value-added products: A review. Process Biochem. 2020, 89, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lv, Z.-W.; Rao, J.; Tian, R.; Sun, S.-N.; Peng, F. Effects of hydrothermal pretreatment on the dissolution and structural evolution of hemicelluloses and lignin: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Meng, X.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J. Recent Advances in the Application of Functionalized Lignin in Value-Added Polymeric Materials. Polymers 2020, 12, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fridrich, B.; de Santi, A.; Elangovan, S.; Barta, K. Bright Side of Lignin Depolymerization: Toward New Platform Chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 614–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).