Diagnosing Multistage Fracture Treatments of Horizontal Tight Oil Wells with Distributed Acoustic Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- FBE, when extracted within frequency bands optimized for injection sensitivity, can robustly delineate active perforation clusters and quantify the relative allocation of fluid and proppant;

- (2)

- LF-DAS provides critical low-frequency strain signatures that reveal mechanical deformation events, including fiber strain anomalies indicative of cable damage or wellbore compression;

- (3)

- The integration of FBE, LF-DAS, and surface injection data enables unambiguous discrimination between overlapping acoustic events (e.g., distinguishing sand screenout buildup from diverter-induced flow redistribution);

- (4)

- The perforation cluster efficiency can be reliably calculated and correlated with real-time diagnostic flags to guide on-the-fly completion adjustments.

2. Methods and Workflow

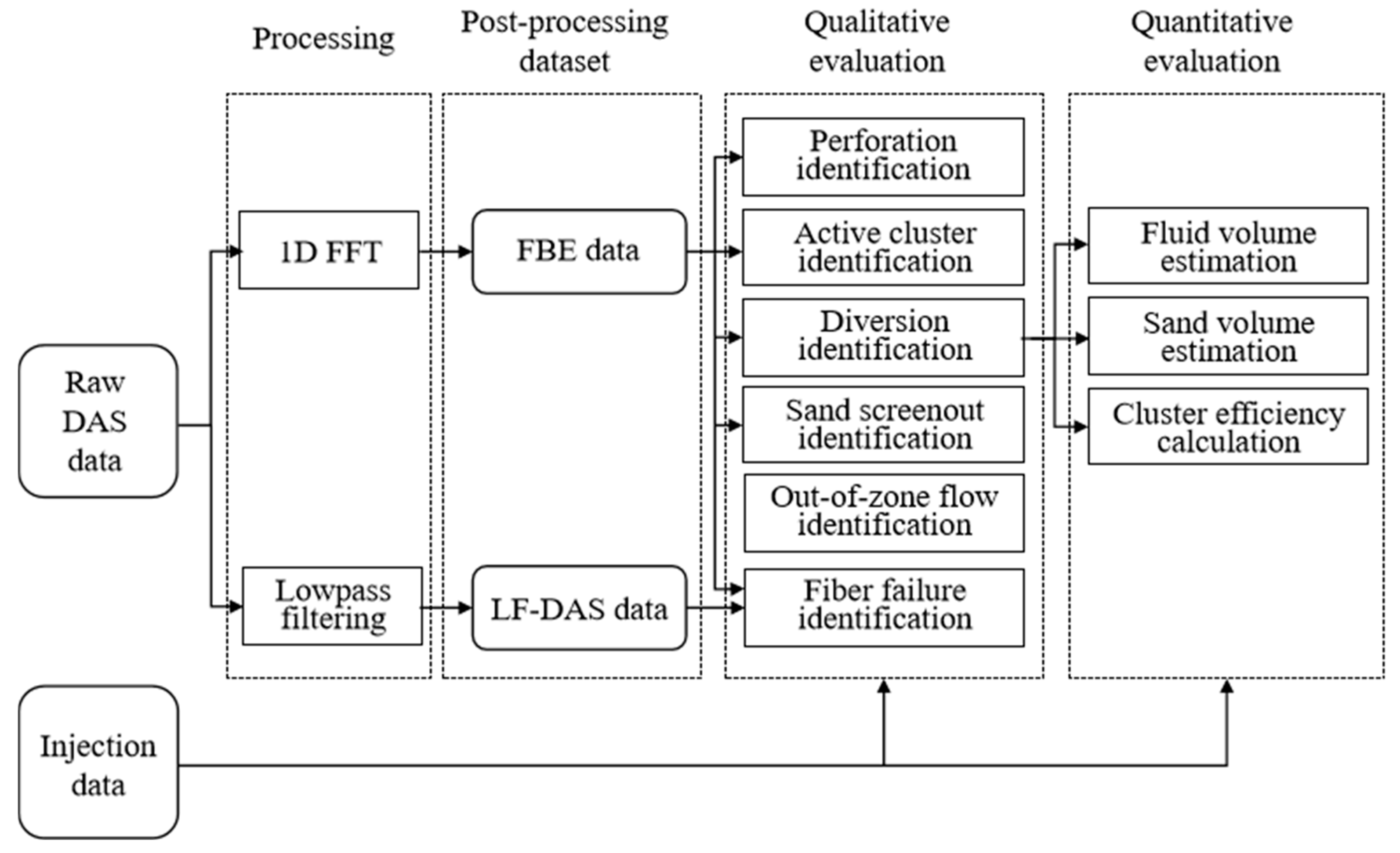

2.1. Overview of the DAS-Based Diagnosis Workflow

- (1)

- A one-dimensional (1D) Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is performed on the raw DAS data to decompose the signal into frequency components, yielding the frequency band energy (FBE) data. Multi-band FBE datasets are generated, and the optimal FBE dataset that is most sensitive to acoustic emissions associated with fluid flow, perforation activation, and proppant transport is used for qualitative diagnoses and quantitative evaluations of fluid volume, sand volume, and cluster efficiency.

- (2)

- Low-pass filtering is applied to the raw DAS data to extract the low-frequency component of DAS (LF-DAS) data, which represents the low-frequency strain response related to fiber tension and compression, as well as long-term deformation of the wellbore and surrounding formation. LF-DAS data are particularly sensitive to fiber breakage during hydraulic fracturing.

- (i)

- Perforation identification, where sudden increases in FBE signals indicate the activation of perforations at each stage;

- (ii)

- Active cluster identification, allowing for determination of which clusters exhibit significant acoustic activity in FBE signals and thus contribute effectively to fracture propagation;

- (iii)

- Diversion identification, which involves detecting the deployment and impact of diverting agents through abrupt shifts in flow patterns observed in the FBE data;

- (iv)

- Sand screenout identification to recognize regions where proppant accumulation leads to reduced or ceased flow, which are identified via sustained FBE intensity anomalies;

- (v)

- Out-of-zone flow identification, in which unintended fluid migration beyond the intended treatment interval is detected via spatially inconsistent FBE signal patterns;

- (vi)

- Fiber failure identification, which involves assessing the optical fiber’s integrity via discontinuities or signal extension stripe features in both the FBE and LF-DAS data.

- (i)

- Fluid volume estimation, which is derived by correlating the amplitude and duration of FBE signals with injection rates and known perforation cluster properties;

- (ii)

- Sand volume estimation, which is performed by applying the fraction of proppant concentration to slurry rate to the fluid volume derived above;

- (iii)

- Cluster efficiency, which is calculated as the ratio of the number of stimulated clusters to the total number of clusters, in which a stimulated cluster is defined as one that has received more than 50% of the ideal volume of the even fluid distribution for the individual stage.

2.2. FBE Extraction

2.3. LF-DAS Extraction

2.4. Quantitative Estimation of Fluid and Proppant Volumes

2.5. Quantitative Calculation of Perforation Cluster Efficiency

3. Field Dataset

3.1. Well Completion

3.2. DAS Acquisition

4. Results and Discussion

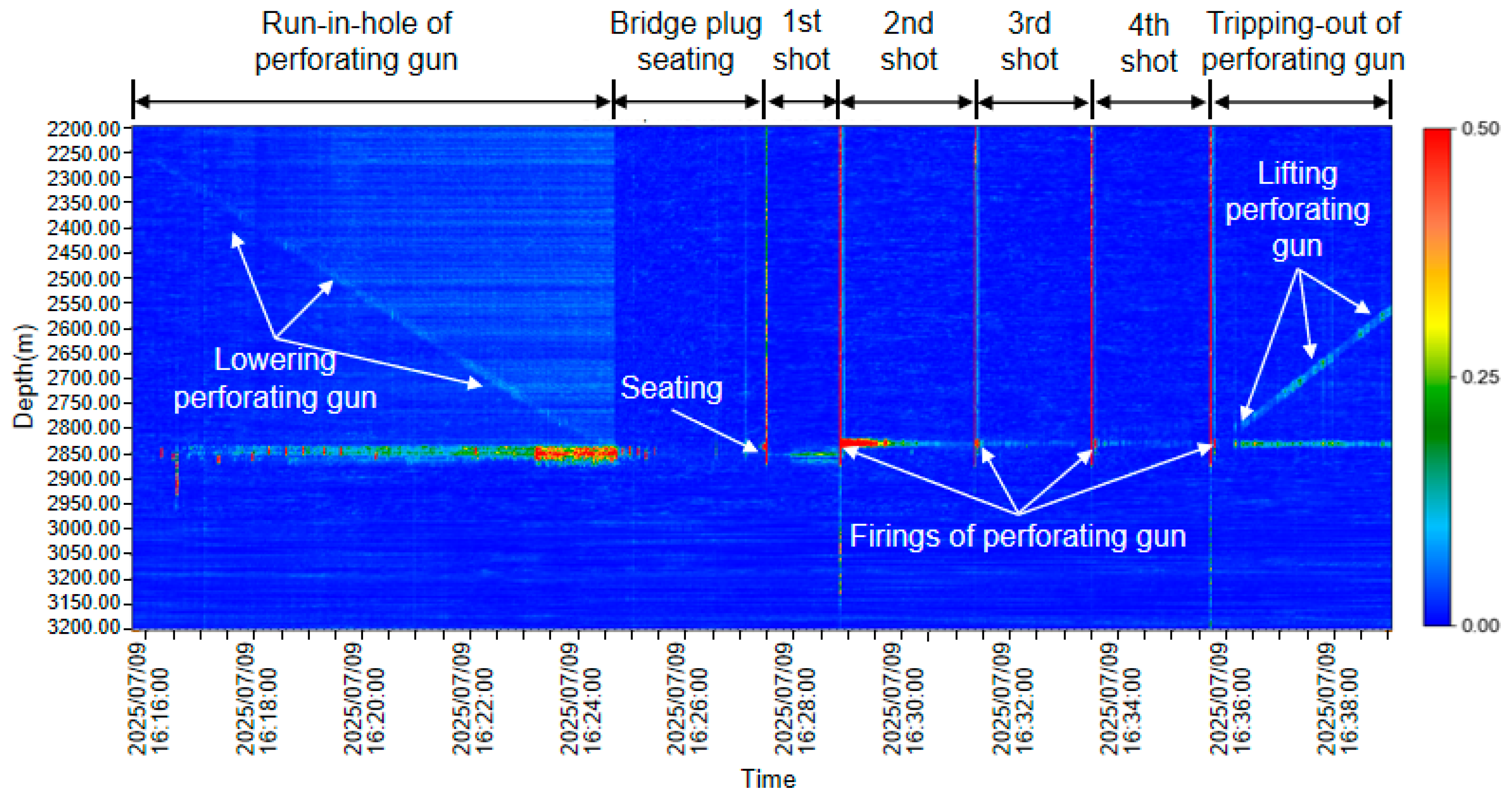

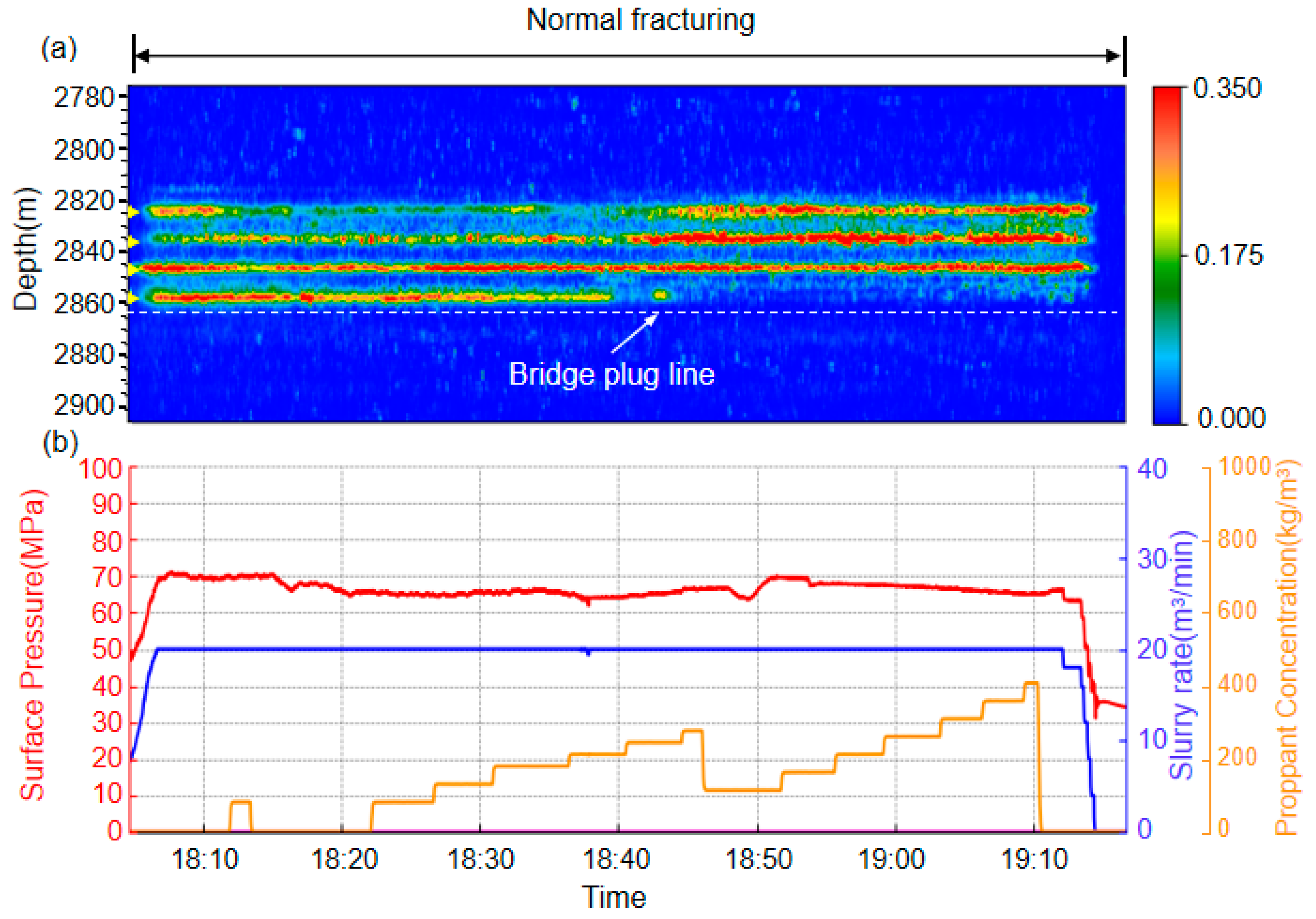

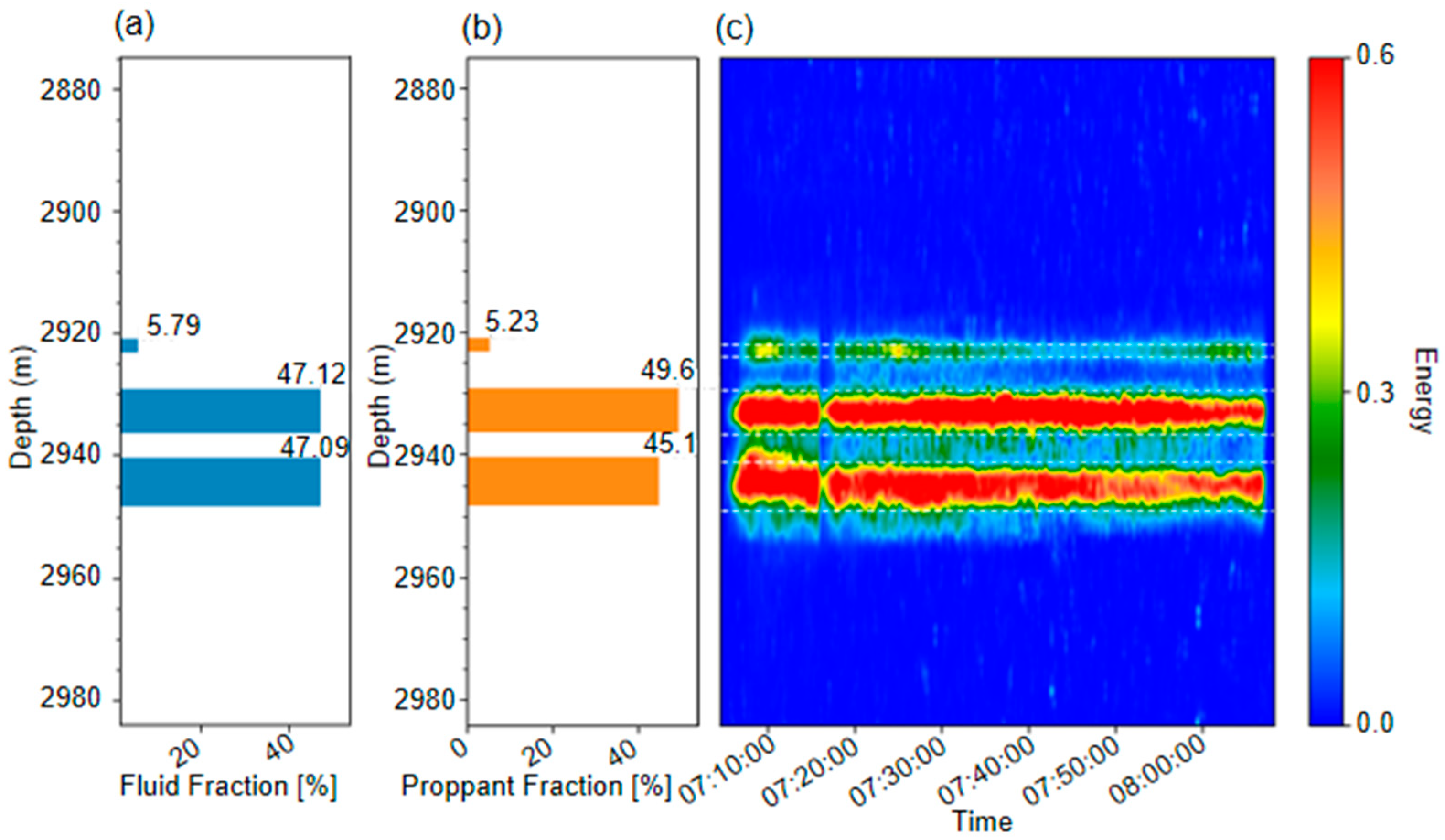

4.1. Normal Fracture Treatment

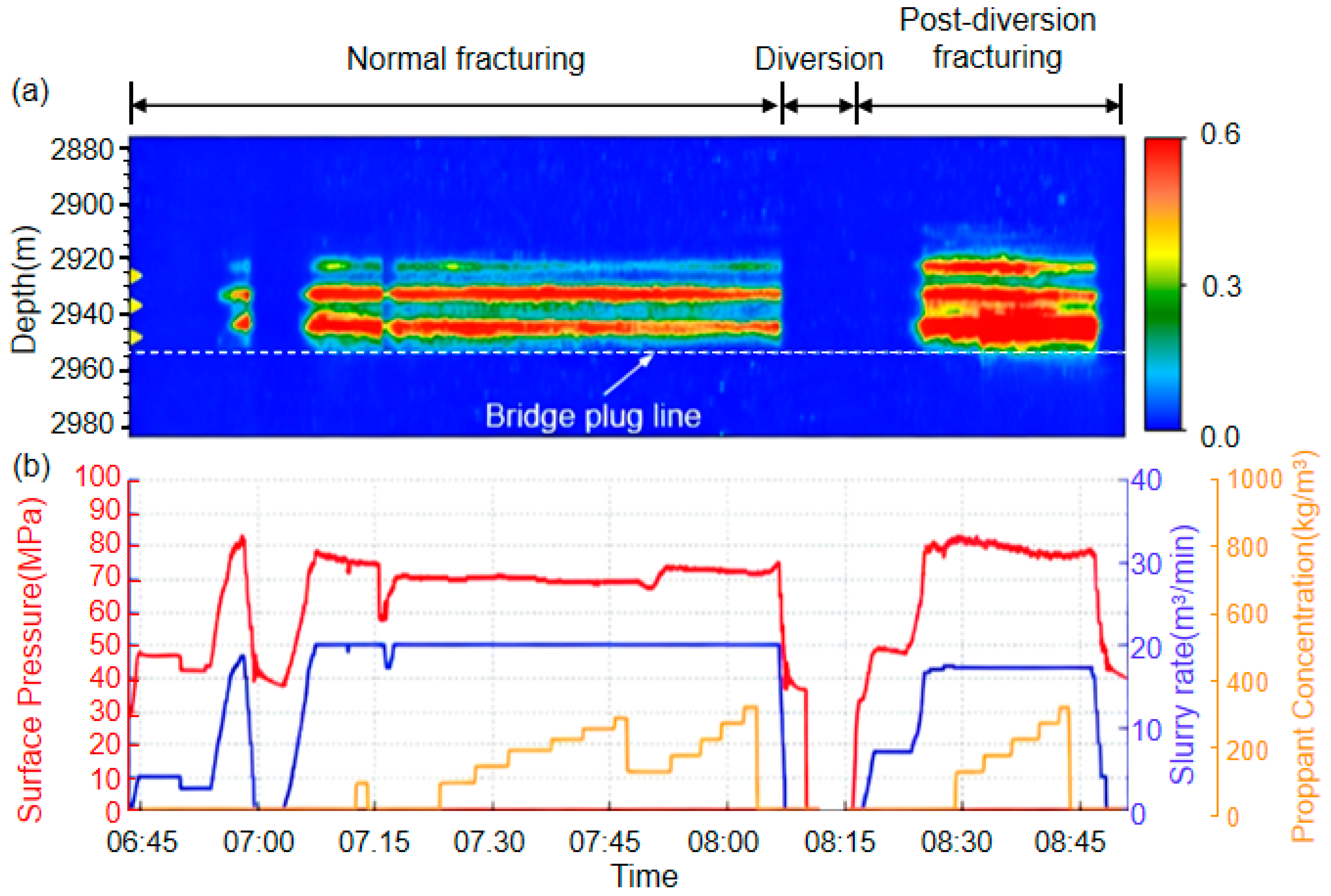

4.2. Diversion Diagnosis

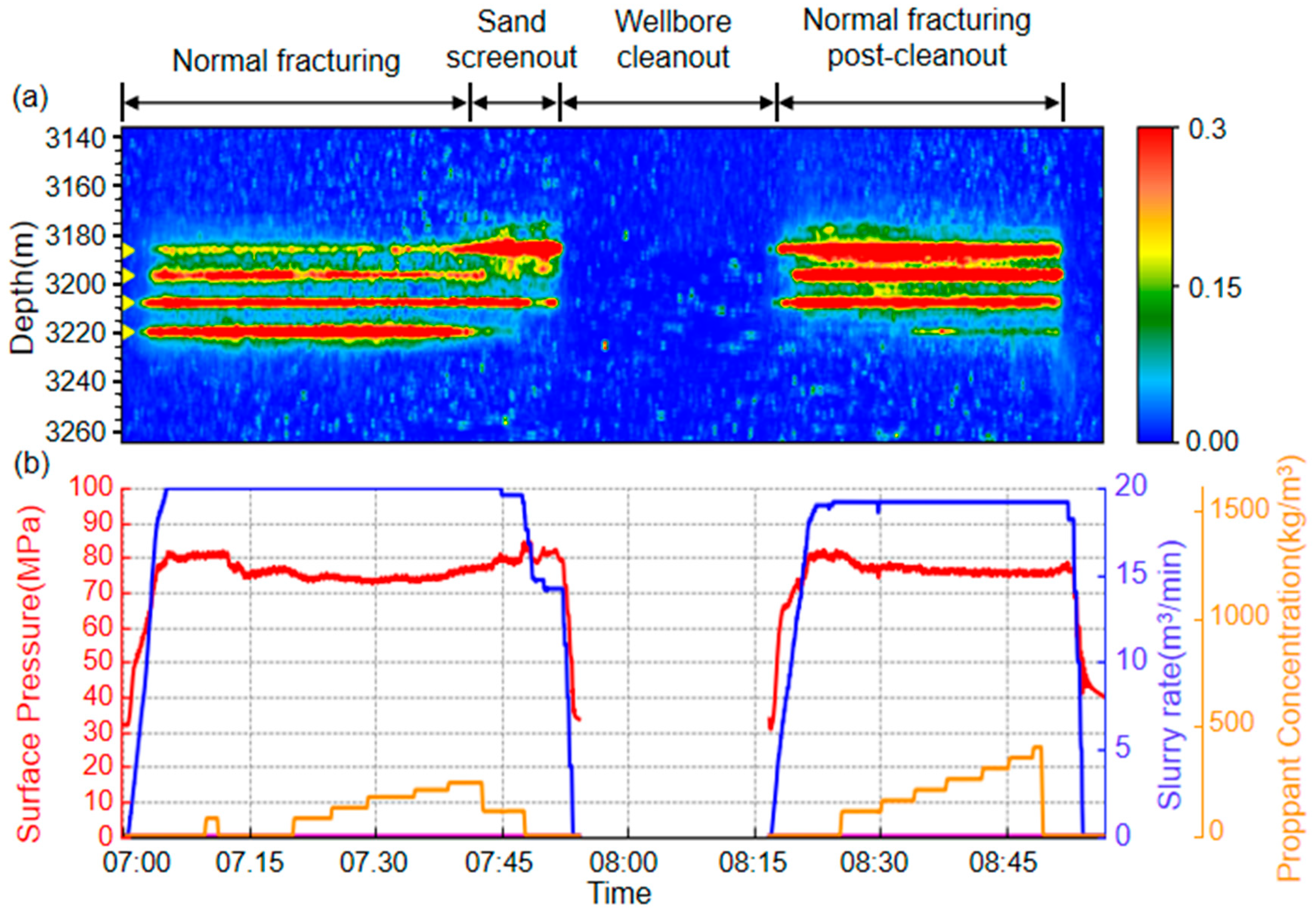

4.3. Sand Screenout Diagnosis

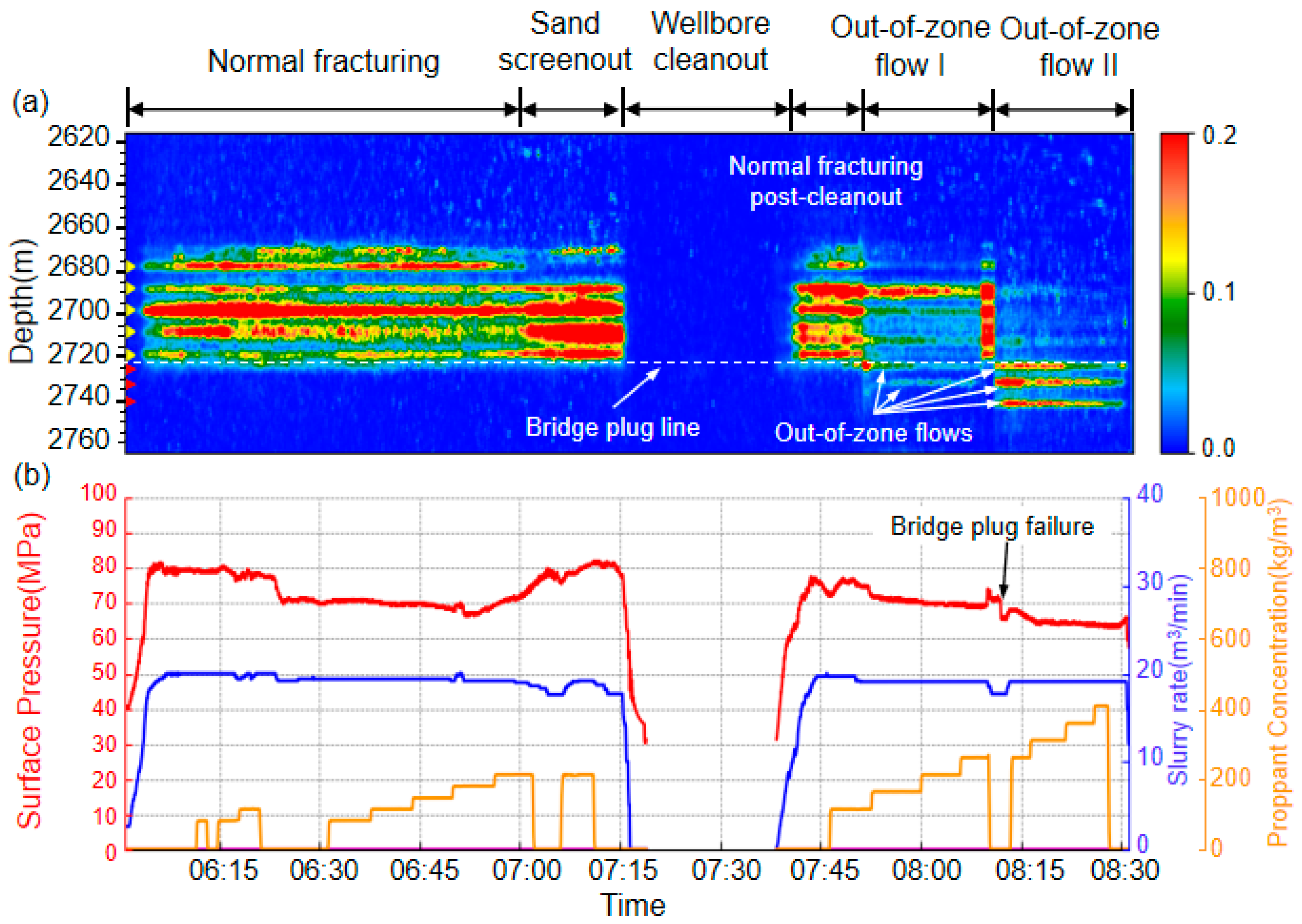

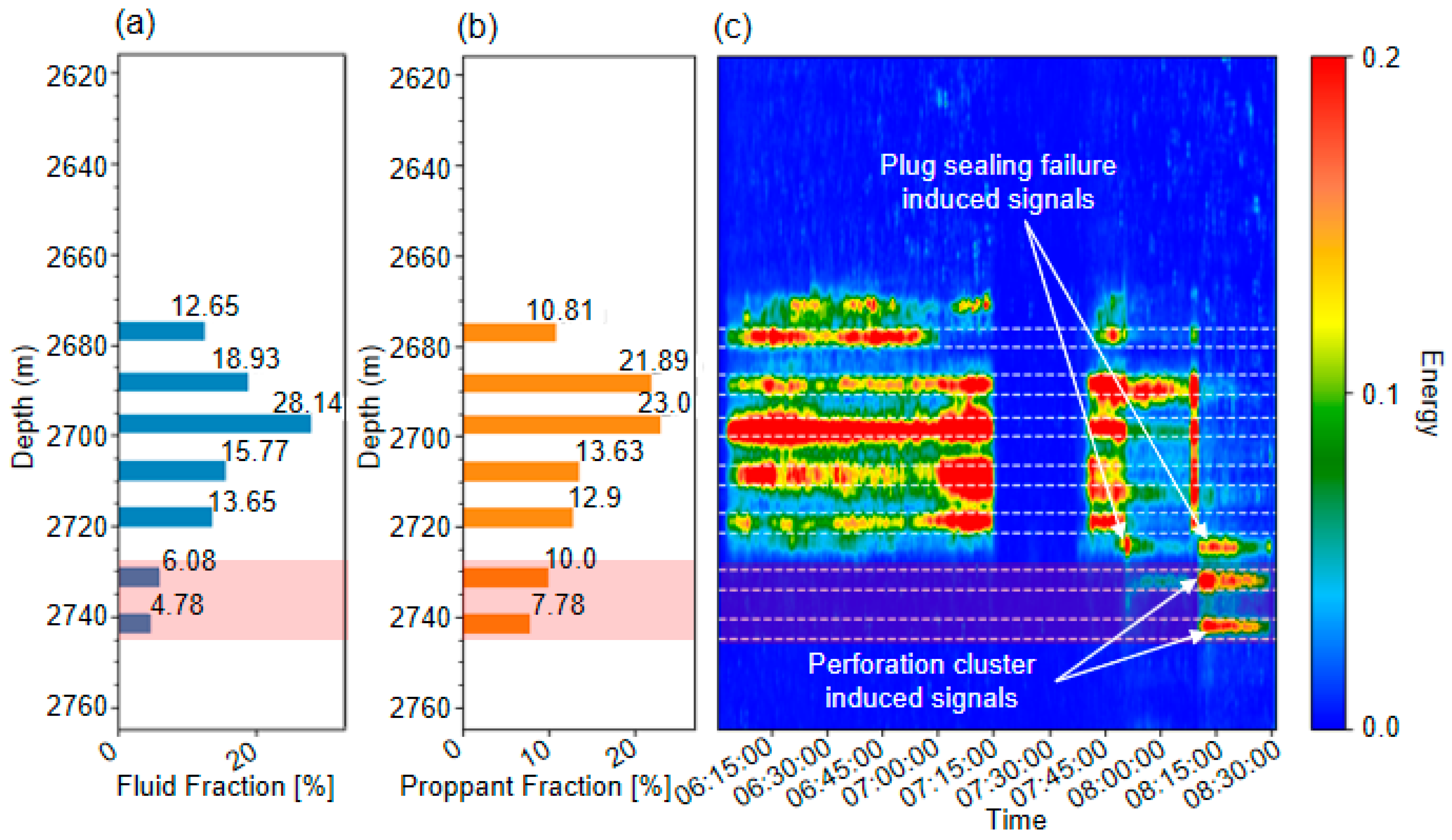

4.4. Out-of-Zone Flow Diagnosis

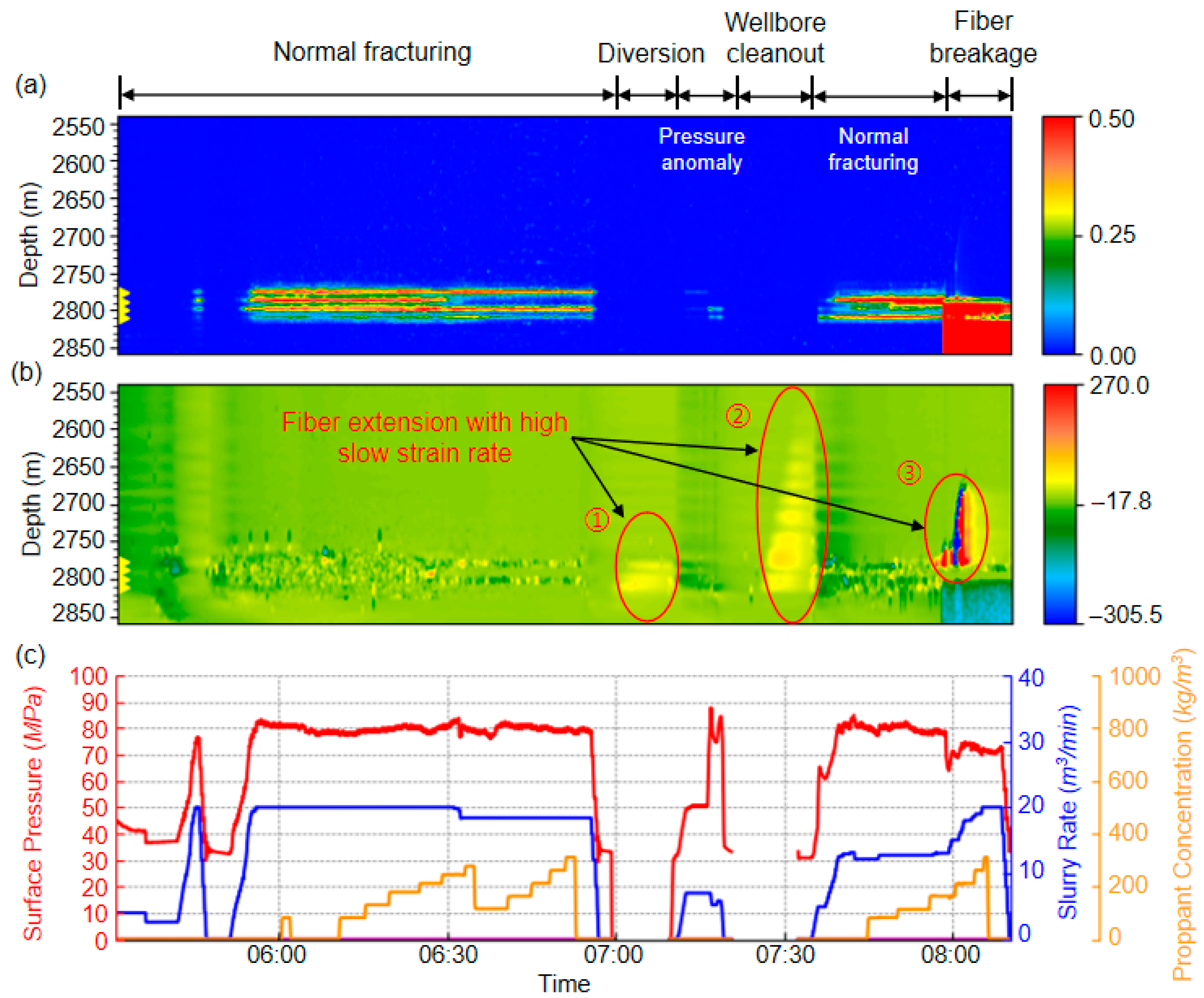

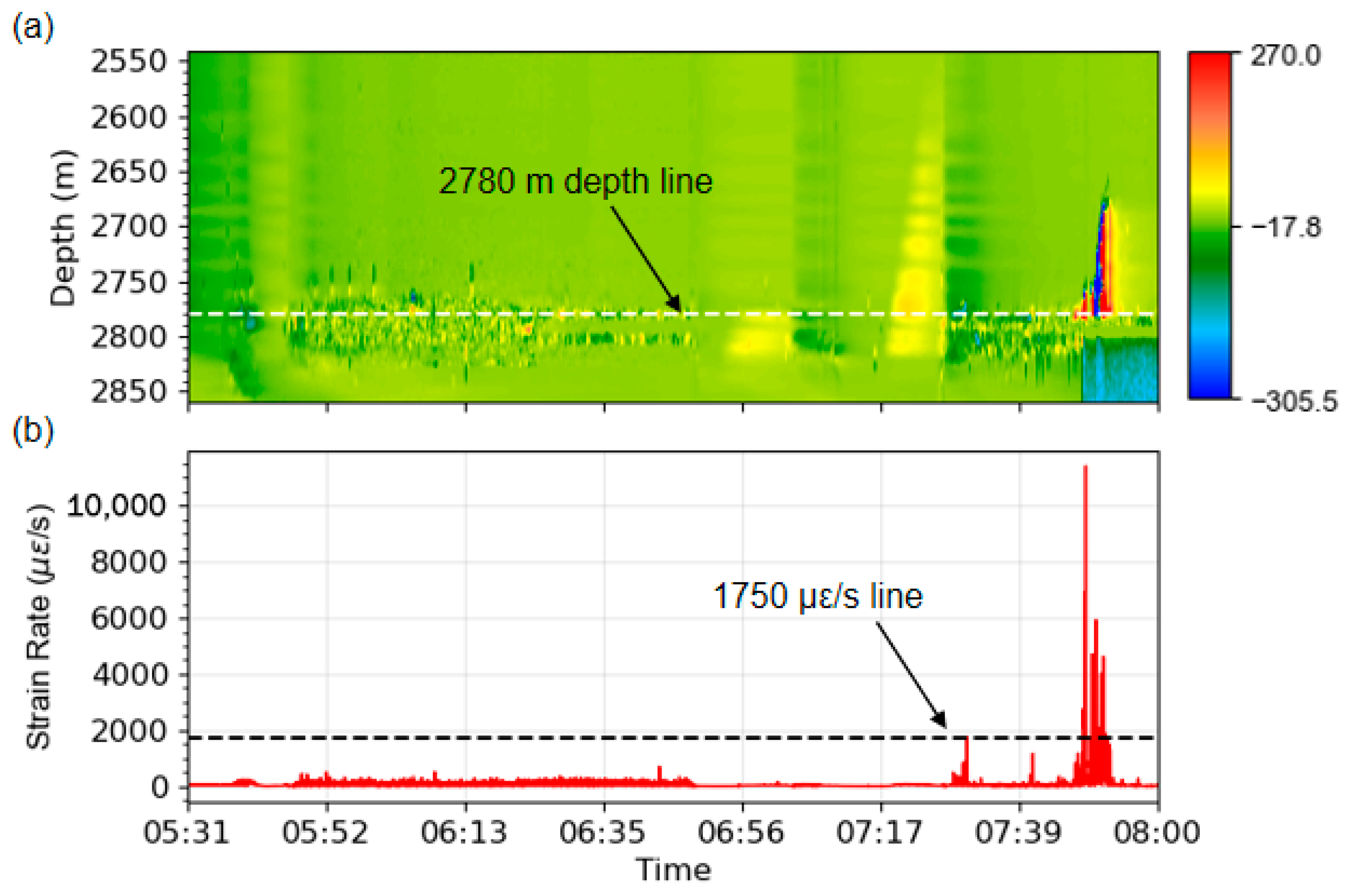

4.5. Fiber Failure Diagnosis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Quantitative accuracy—Fluid and proppant allocations derived from the 50–200 Hz FBE band showed strong agreement with expected stage-level volumes.

- (2)

- Anomaly fingerprinting—Distinct DAS signatures were identified for five critical events: (i) sand screenout manifests as abrupt, localized FBE spikes, coinciding with pressure surges; (ii) effective diversion produces sequential, migrating energy fronts across clusters; (iii) out-of-zone flow appears as coherent acoustic activity outside perforated intervals; (iv) normal treatments exhibit spatially uniform FBE envelopes aligned with the cluster geometry; and (v) incipient fiber failure generates persistent high-strain-rate stripe patterns in LF-DAS (<0.5 Hz), which were detectable minutes before signal loss, and a strain rate of 1750 με/s was found to serve as a case-specific empirical early warning threshold for fiber failure risk.

- (3)

- Methodological synergy—Neither raw DAS nor FBE alone suffices; LF-DAS provides complementary mechanical context, while FBE isolates flow-induced acoustics, jointly enabling robust interpretation even in the presence of overlapping noise sources.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DAS | Distributed Acoustic Sensing |

| DTS | Distributed Temperature Sensing |

| FBE | Frequency Band Energy |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| ICV | Inflow Control Valve |

| IU | Interrogator Unit |

| LF-DAS | Low-Frequency Components of DAS |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| PCE | Perforation Cluster Efficiency |

| PnP | Plug-and-Perf |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| RMS | Root Mean Squared |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

| TGD-OFDR | Time-gated Digital Optical Frequency-Domain Reflectometry |

| VGL | Variable Gauge Length |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, S.; Li, J. Modeling of Scale-Dependent Perforation Geometrical Fracture Growth in Naturally Layered Media. Eng. Geol. 2024, 336, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, L.; Wright, C.; Mayerhofer, M.; Pearson, M.; Griffin, L.; Weddle, P. Trends in the North American frac industry: Invention through the shale revolution. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 5–7 February 2019; p. D011S001R001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, C.; Singh, A.; McClure, M.; McKimmy, M.; Lassek, J. The perfect frac stage—What’s the value? In Proceedings of the Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 17–19 June 2024; pp. 923–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, M.; Hill, D.; Webster, P.; Fidan, E.; Birch, B. First downhole application of distributed acoustic sensing for hydraulic-fracturing monitoring and diagnostics. SPE Drill. Complet. 2012, 27, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugueto, G.; Ehiwario, M.; Grae, A.; Molenaar, M.; McCoy, K.; Huckabee, P.; Barree, B. Application of integrated advanced diagnostics and modeling to improve hydraulic fracture stimulation analysis and optimization. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–6 February 2014; p. SPE-168603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, M.; Fidan, E.; Hill, D. Real-time downhole monitoring of hydraulic fracturing treatments using fibre optic distributed temperature and acoustic sensing. In Proceedings of the SPE/EAGE European Unconventional Resources Conference and Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 20–22 March 2012; p. SPE-152981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, M.; Cox, B. Field cases of hydraulic fracture stimulation diagnostics using fiber optic distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) measurements and Analyses. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Unconventional Resources Conference and Exhibition, Muscat, Oman, 24 January 2013; p. SPE-164030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, J.; Zhu, X.; Luo, L.; Correa, J.; Soga, K.; Ajo-Franklin, J. Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing for in-well hydraulic fracture monitoring. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 250, 213792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, K.; Crickmore, R.; Werdeg, Z.; Laing, C.; Molenaar, M. Monitoring hydraulic fracturing operations using fiber-optic distributed acoustic sensing. In Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–22 July 2015; p. URTEC-2158449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, D.; Friehauf, K.; Roberts, G.; Whittaker, J. Integrating distributed acoustic sensing, treatment-pressure analysis, and video-based perforation imaging to evaluate limited-entry-treatment effectiveness. SPE Prod. Oper. 2020, 35, 730–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tang, H.; Hurt, R.; Jayaram, V.; Wagner, J. Joint interpretation of fiber optics and downhole gauge data for near wellbore region characterization. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–5 February 2020; p. D021S004R002. [Google Scholar]

- Lorwongngam, A.; McKimmy, M.; Oughton, E.; Cipolla, C. One shot wonder XLE design: A continuous improvement case study of developing XLE design in the Bakken. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 31 January–2 February 2023; p. D021S006R002. [Google Scholar]

- Ramurthy, M.; Richardson, J.; Brown, M.; Sahdev, N.; Wiener, J.; Garcia, M. Fiber-optics results from an intra-stage diversion design completions study in the Niobrara formation of DJ basin. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 9–16 February 2016; p. D021S006R005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumble, M.; Sinkey, M.; Meehleib, J. Got diversion? Real time analysis to identify success or failure. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 5–7 February 2019; p. D021S005R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugueto, C.; Gustavo, A.; Huckabee, P.; Molenaar, M. Challenging assumptions about fracture stimulation placement effectiveness using fiber optic distributed sensing diagnostics: Diversion, stage isolation and overflushing. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–6 February 2015; p. D011S002R001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugueto, G.; Huckabee, P.; Nguyen, A.; Daredia, T.; Chavarria, J.; Wojtaszek, M.; Nasse, D.; Reynolds, A. A cost-effective evaluation of pods diversion effectiveness using fiber optics DAS and DTS. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–5 February 2020; p. D011S002R001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvenkatanathan, P.; Langnes, T.; Beaumont, P.; White, D.; Webster, M. Downhole sand ingress detection using fibre-optic distributed acoustic sensors. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–10 November 2016; p. D031S061R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.; Woerpel, C.; Trujillo, K.; Bohn, R.; Wygal, B.; Carney, B.; Carr, T. Hydraulic fracture characterization using fiber optic DAS and DTS data. In Proceedings of the SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, Online, 11–16 October 2020; p. D041S096R007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, R.; Hull, R.; Trujillo, K.; Wygal, B.; Parsegov, S.; Carr, T.; Carney, B. Learnings from the Marcellus Shale Energy and Environmental Lab (MSEEL) using fiber optic tools and Geomechanical modeling. In Proceedings of the Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 20–22 July 2020; pp. 1833–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James-Ravenell, M.; Jin, G. Characterizing in-well DAS signal before fiber breakage. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy, Houston, TX, USA, 26–29 August 2024; pp. 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhotina, I. Using Distributed Acoustic Sensing for Multiple-Stage Fractured Well Diagnosis. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka, Y.; Zhu, D.; Hill, A. Investigation of the Reduction in Distributed Acoustic Sensing Signal Due to Perforation Erosion by Using CFD Acoustic Simulation and Lighthill’s Acoustic Power Law. Sensors 2024, 24, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhotina, I.; Sakaida, S.; Zhu, D.; Hill, A. Diagnosing multistage fracture treatments with distributed fiber-optic sensors. SPE Prod. Oper. 2020, 35, 0852–0864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhu, D.; Hill, A. Acoustic Signature of Flow From a Fractured Wellbore. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 28–30 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Holley, E.; Jaaskelainen, M. Quantitative real-time DAS analysis for plug-and-perf completion operation. In Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 20 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R. Experimental Study of the Effect of Permeability on the Generation of Noise. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Sheng, L.; Guo, H.; Jiao, J.; Li, Z.; Sui, W. A Sensitive Frequency Band Study for Distributed Acoustical Sensing Monitoring Based on the Coupled Simulation of Gas–Liquid Two-Phase Flow and Acoustic Processes. Photonics 2024, 11, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, M.; Kurosawa, I.; Uchida, S.; Kato, A.; Ito, Y.; Takagi, S.; de Groot, M.; Hara, S. Case study of hydraulic fracture monitoring using low-frequency components of DAS data. In Proceedings of the SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts, San Antonio, TX, USA, 15–20 September 2019; pp. 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugueto, G.; Todea, F.; Daredia, T.; Wojtaszek, M.; Huckabee, P.; Reynolds, A.; Laing, C.; Chavarria, J.A. Can you feel the strain? DAS strain fronts for fracture geometry in the BC Montney, Groundbirch. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Calgary, AL, Canada, 30 September–2 October 2019; p. D021S029R005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Roy, B. Hydraulic-fracture geometry characterization using low-frequency DAS signal. Lead. Edge. 2017, 36, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In’t Panhuis, P.; den Boer, H.; Van Der Horst, J.; Paleja, R.; Randell, D.; Joinson, D.; Bartlett, R. Flow Monitoring and Production Profiling Using DAS. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27–29 October 2014; p. SPE-170917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousi, P.; Carr, T.; Wilson, T.; Amini, S.; Wilson, C.; Thomas, M.; MacPhail, K.; Crandall, D.; Carney, B.; Costello, I.; et al. Correlating distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) to natural fracture intensity for the Marcellus Shale. In Proceedings of the SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts, Houston, TX, USA, 24–29 September 2017; pp. 5386–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Tian, Y.; Fu, Z.; Wang, C. Uncertainty analysis of quantitative hydraulic fracturing fluid and sand volumes calculated from DAS data. In Proceedings of the SEG Workshop on Fiber Optics Sensing for Energy Applications, Xi’an, China, 21–23 July 2024; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, R.; Bai, Y.; Guo, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, C. An Enhanced Workflow for Quantitative Evaluation of Fluid and Proppant Distribution in Multistage Fracture Treatment with Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Processes 2025, 13, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Ciervo, C.; Cole, M.; Coleman, T.; Mondanos, M. Fracture hydromechanical response measured by fiber optic distributed acoustic sensing at milliHertz frequencies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 7295–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shragge, J.; Yang, J.; Issa, N.; Roelens, M.; Dentith, M.; Schediwy, S. Low-frequency ambient Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS): Useful for subsurface investigation? In Proceedings of the SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, San Antonio, TX, USA, 15–20 September 2019; p. D023S007R005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavik, K. Annuli liquid-level surveillance using distributed fiber-optic sensing data. SPE J. 2024, 29, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrenbach, M.; Ridge, A.; Cole, S.; Boone, K.; Kahn, D.; Rich, J.; Silver, K.; Langton, D. DAS microseismic monitoring and integration with strain measurements in hydraulic fracture profiling. In Proceedings of the Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 24–26 July 2017; pp. 1316–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Jin, G.; Wu, K.; Wan, X. A Numerical Model for Analyzing Mechanical Slippage Effect on Crosswell Distributed Fiber-Optic Strain Measurements During Fracturing. SPE J. 2024, 29, 4724–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.; Scolimoski, E.; Gomes, D.; Brusamarello, B.; Dureck, E.; Pipa, D. Low-Frequency Strain Testbed for DAS Performance Characterization. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2025, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, S.R.; Lahman, M.; Persac, S. Methods improve stimulation efficiency of perforation clusters in completions. J. Pet. Technol. 2014, 66, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugueto, C.G.A.; Huckabee, P.T.; Molenaar, M.M.; Wyker, B.; Somanchi, K. Perforation Cluster Efficiency of Cemented Plug and Perf Limited Entry Completions; Insights from Fiber Optics Diagnostics. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 9–11 February 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, X.; Liu, Q.; He, Z. Distributed fiber-optic vibration sensing based on phase extraction from time-gated digital OFDR. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 33301–33309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; He, Z. Time-domain multiplexed high resolution fiber optics strain sensor system based on temporal response of fiber Fabry-Perot interferometers. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 21914–21925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Fan, C.; Yan, B.; Chen, J.; Huang, T.; Yan, Z.; Sun, Q. Fading suppression for distributed acoustic sensing assisted with dual-laser system and differential-vector-sum algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 9417–9425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, T.; Bettinelli, P.; Le Calvez, J. Variable gauge length: Processing theory and applications to distributed acoustic sensing. Geophys. Prospect. 2025, 73, 160–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Sui, Q.; Li, Z. Three-layer structure multiplexing fading elimination method in long-haul Φ-OTDR. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 5017–5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakirouhani, A.; Jolfaei, S. Assessment of hydraulic fracture initiation pressure using fracture mechanics criterion and coupled criterion with emphasis on the size effect. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 5897–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, D.D.; Zhang, J. Pressure-Based Diagnostics for Evaluating Treatment Confinement. SPE Prod. Oper. 2021, 36, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshikata, D.; Zhu, D.; Hill, A.D. Evaluating Fluid Distribution by Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) with Perforation Erosion Effect. Sensors 2025, 25, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B. Fracture Competitive Propagation and Fluid Dynamic Diversion During Horizontal Well Staged Hydraulic Fracturing. Processes 2025, 13, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Domelen, M. A practical guide to modern diversion technology. In Proceedings of the SPE Oil and Gas Symposium/Production and Operations Symposium, Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 27–31 March 2017; p. D031S007R002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, M.; Baumbach, J.; Prosser, J.; Pettigrew, S.; Elvig, K. An Eagle Ford case study: Improving an infill well completion through optimized refracturing treatment of the offset parent wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 5–7 February 2019; p. D011S001R005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, L. Sand Screenout Early Warning Models Based on Combinatorial Neural Network and Physical Models. Processes 2025, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Elsworth, D.; Gong, P.; Bian, X.; Zhang, L. Integration of real-time monitoring and data analytics to mitigate sand screenouts during fracturing operations. SPE J. 2024, 29, 3449–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianoush, P.; Gomar, M.; Khah, N.K.F.; Hosseini, S.; Kadkhodaie, A.; Varkouhi, S. Designing multi-function rapid right angle set slurry compositions for a high pressure-high temperature well. Results Earth Sci. 2025, 3, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Definition | Parameter Type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instantaneous flow rate | Variable | Represented by the slurry rate per second of injection curve | |

| Total flow rate | Variable | Represented by the slurry rate during a given time duration | |

| Time | Variable | Represented by the time-series of injection curve | |

| Δt | Delta time | Constant | Represented by the sampling time interval of injection curve |

| E | FBE value | Variable | Derived from the raw DAS data |

| A | Correlation parameter | Constant | Empirically available |

| B | Correlation parameter | Constant | Empirically available and can be replaced as a function of A |

| N | Number of perforation clusters per stage | Variable | Depends on well completion |

| c | Proppant concentration | Variable | Represented by the proppant concentration per second of injection curve |

| V | Cumulative fluid volume | Variable | To be calculated |

| W | Cumulative proppant volume | Variable | To be calculated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, B.; Tang, J.; Li, L. Diagnosing Multistage Fracture Treatments of Horizontal Tight Oil Wells with Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Processes 2025, 13, 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123925

Zhu H, Liu W, Zhao Z, Li B, Tang J, Li L. Diagnosing Multistage Fracture Treatments of Horizontal Tight Oil Wells with Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123925

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Hanbin, Wenqiang Liu, Zhengguang Zhao, Bobo Li, Jizhou Tang, and Lei Li. 2025. "Diagnosing Multistage Fracture Treatments of Horizontal Tight Oil Wells with Distributed Acoustic Sensing" Processes 13, no. 12: 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123925

APA StyleZhu, H., Liu, W., Zhao, Z., Li, B., Tang, J., & Li, L. (2025). Diagnosing Multistage Fracture Treatments of Horizontal Tight Oil Wells with Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Processes, 13(12), 3925. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123925