Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions by Waste-Pretreated Ganoderma resinaceum Biomass: Effect of Process Parameters and Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Biosorbent Preparation

2.3. Characteristics of Pretreated G. resinaceum Biomass

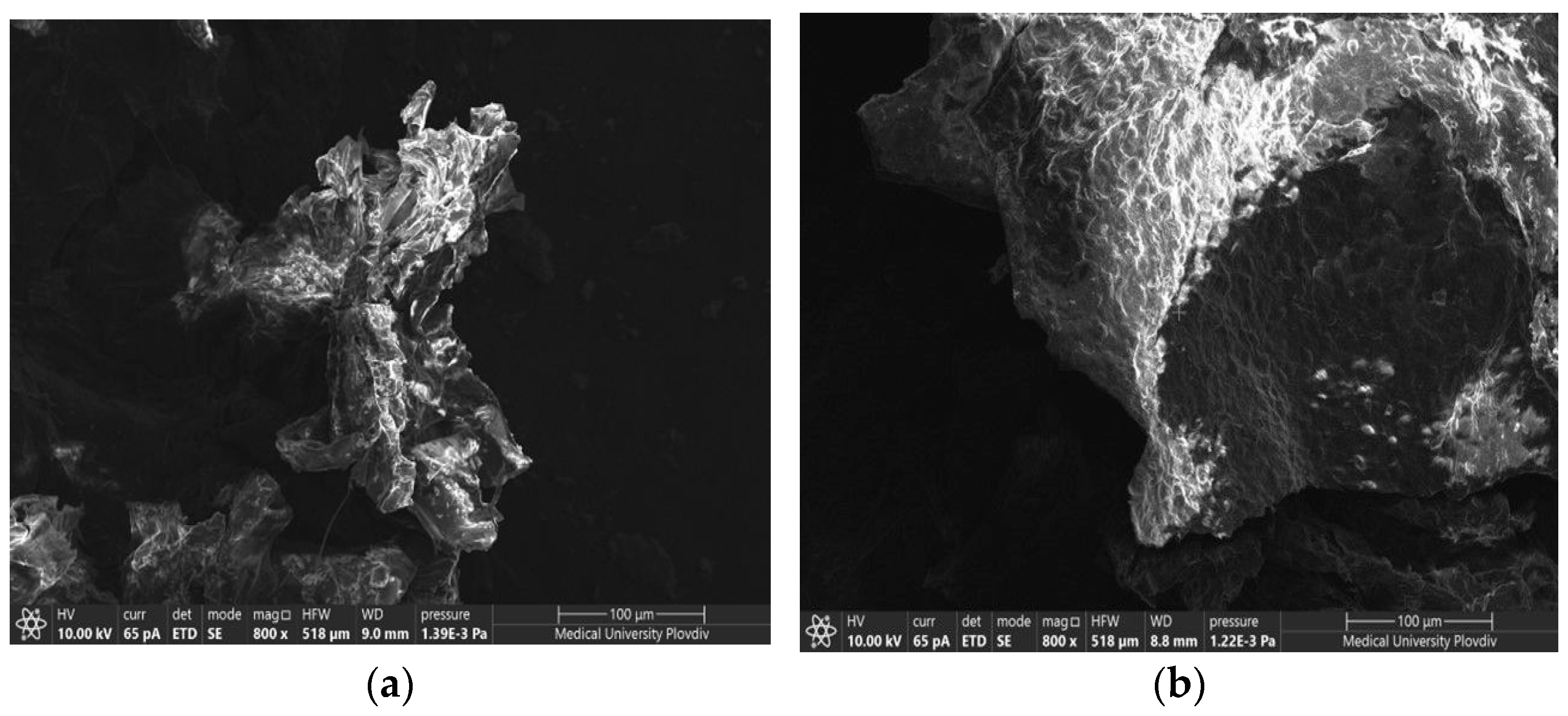

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

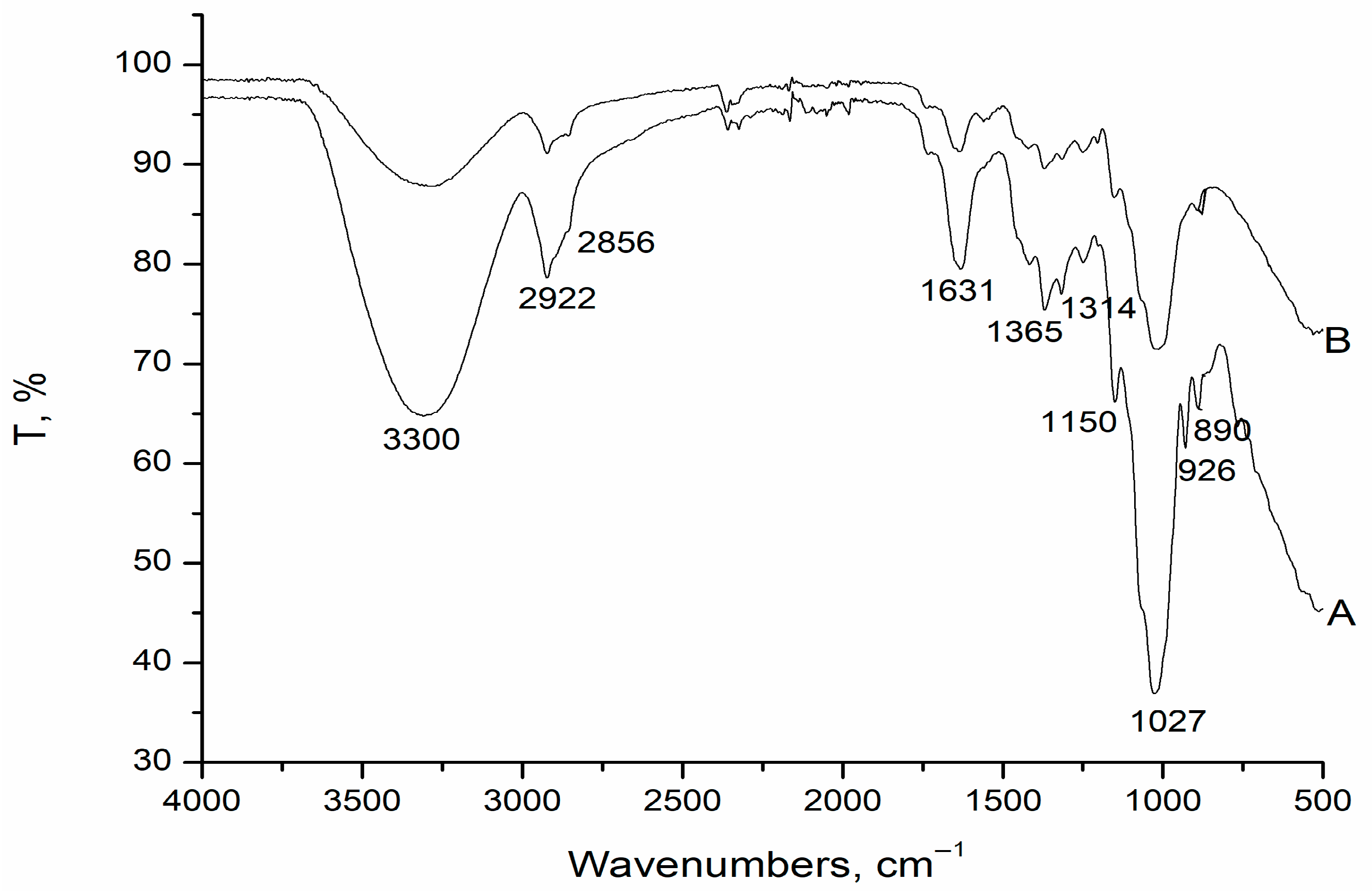

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.3.3. pH at the Point of Zero Charge

2.4. CIP Analysis

2.5. Biosorption Studies

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biomass Characterization

3.1.1. SEM/EDX Analysis

3.1.2. FT-IR Analysis

3.1.3. Point of Zero Charge

3.2. Biosorption Studies

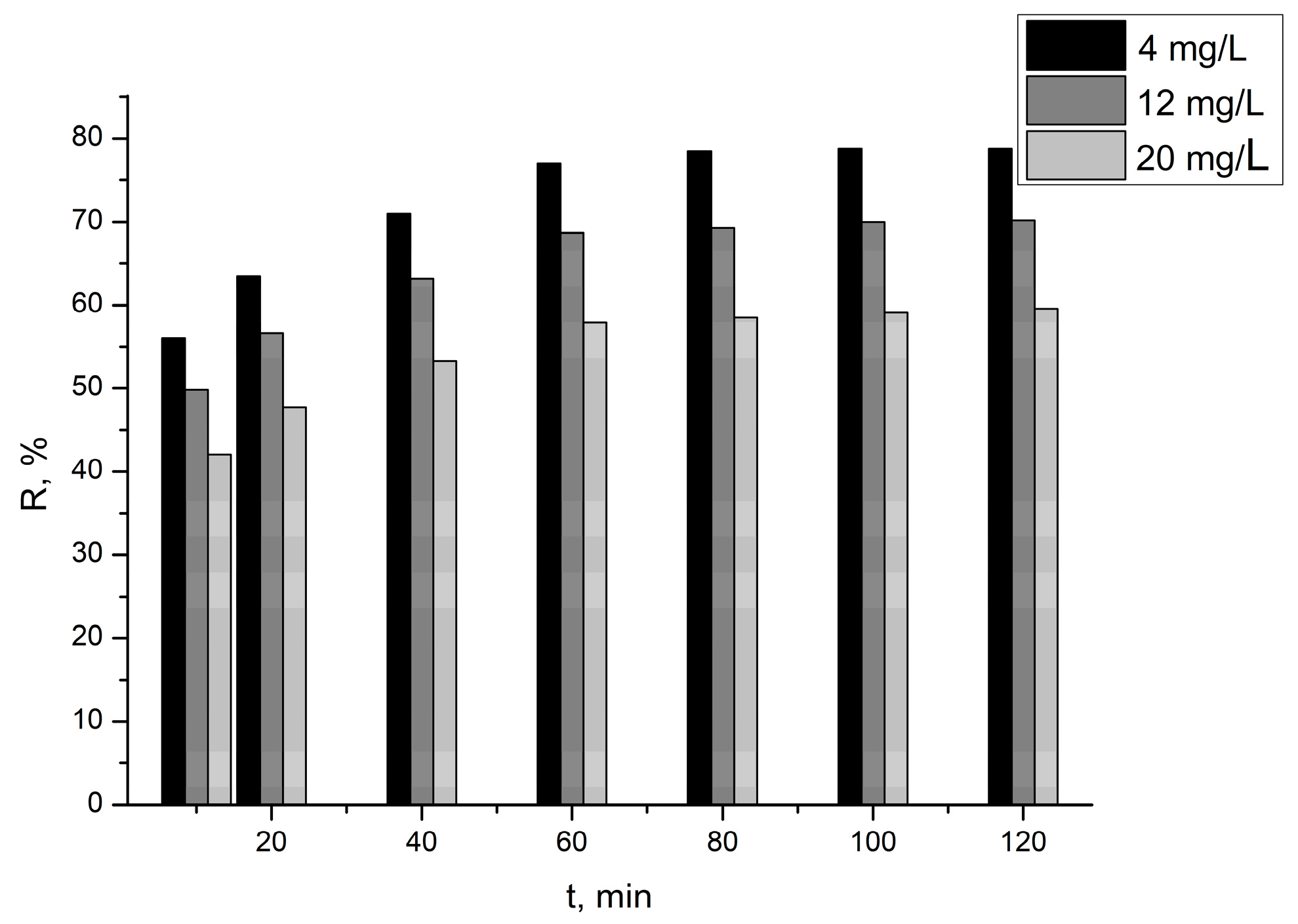

3.2.1. Effect of Process Parameters on the Effectiveness of Ciprofloxacin Removal from Aqueous Solutions

3.2.2. Kinetic Modeling

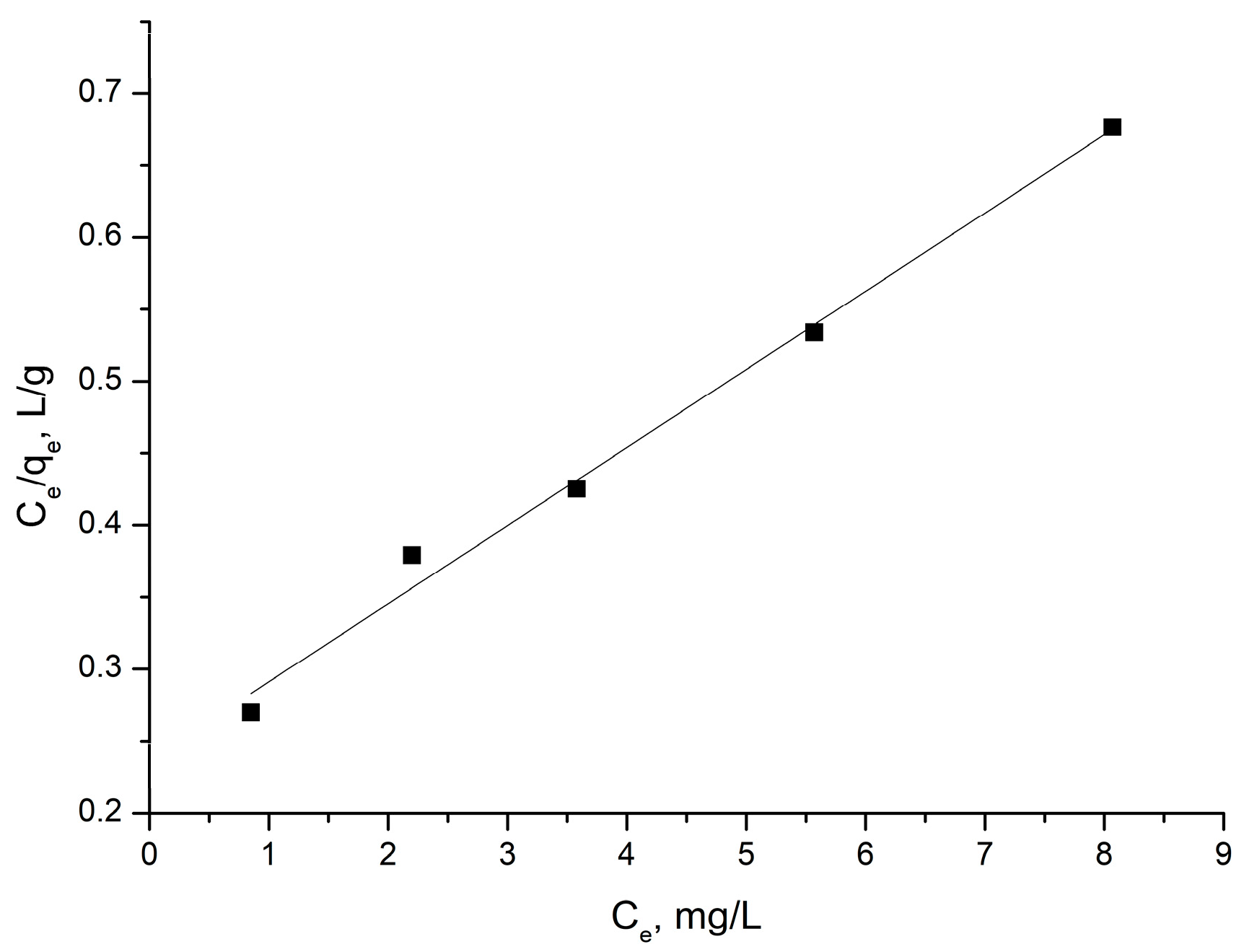

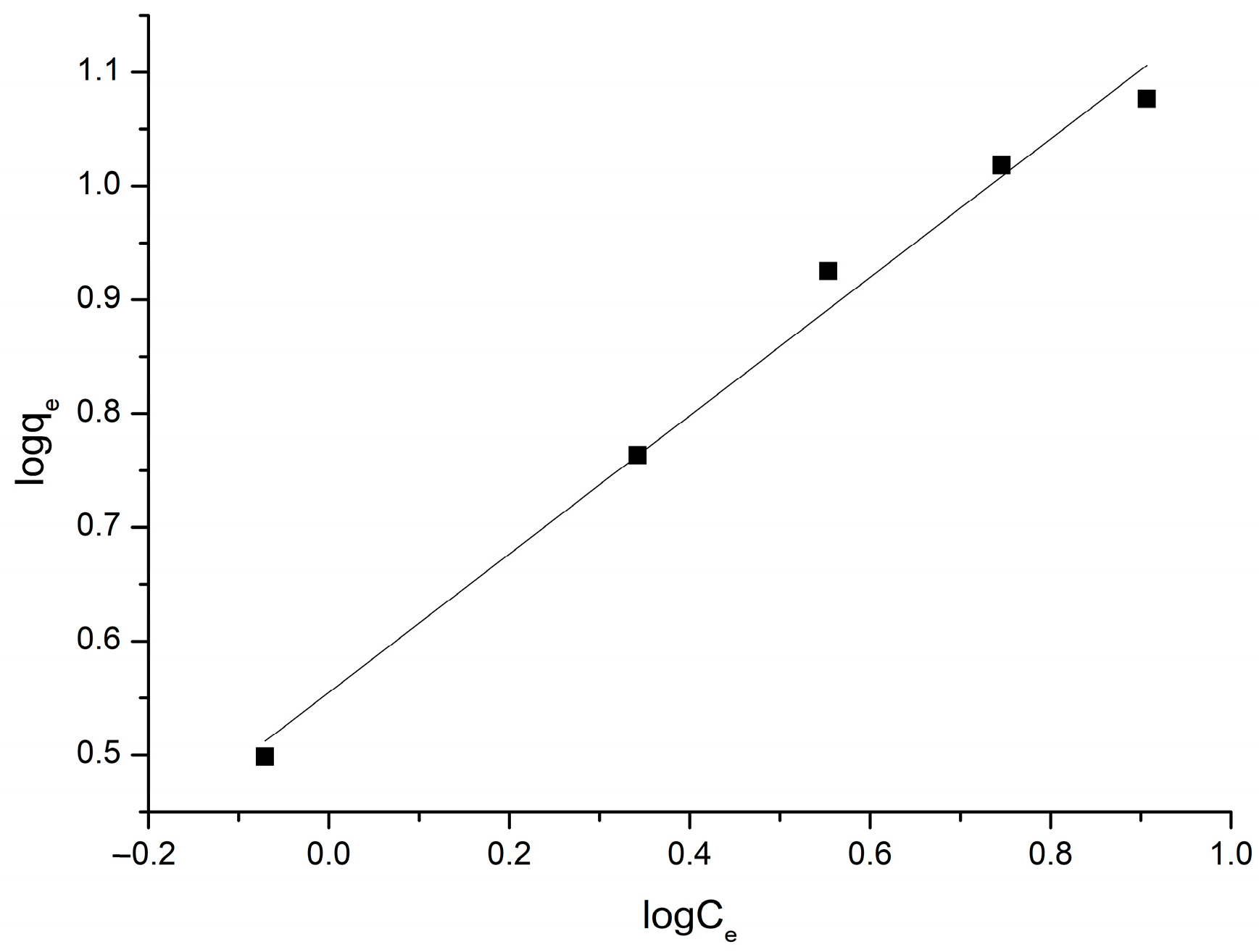

3.2.3. Equilibrium Modeling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Segura, P.A.; François, M.; Gagnon, C.; Sauvé, S. Review of the occurrence of anti-infectives in contaminated wastewaters and natural and drinking waters. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, H.E.; Lehner, B.; Nicell, J.A.; Khan, U.; Klein, E.Y. Antibiotics in the global river system arising from human consumption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf096. [Google Scholar]

- Vardanyan, R.S.; Hruby, V.J. 33—Antimicrobial Drugs. In Synthesis of Essential Drugs, 1st ed.; Vardanyan, V.J., Hruby, V.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 499–523. [Google Scholar]

- Shariati, A.; Arshadi, M.; Khosrojerdi, M.A.; Abedinzadeh, M.; Ganjalishahi, M.; Maleki, A.; Heidary, M.; Khoshnood, S. The resistance mechanisms of bacteria against ciprofloxacin and new approaches for enhancing the efficacy of this antibiotic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1025633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, H.O.; Shikoray, L.; Mohamed, M.-Y.I.; Habib, I.; Matsumoto, T. Veterinary Drug Residues in the Food Chain as an Emerging Public Health Threat: Sources, Analytical Methods, Health Impacts, and Preventive Measures. Foods 2024, 13, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerer, K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment—A review–Part I. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; de Pedro, C.; Paxeus, N. Effluent from drug manufacturers contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J. Hazard Mater. 2007, 148, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwanzala, M.D.; Lehutso, R.F.; Kasonga, T.K.; Dewar, J.B.; Momba, M.N.B. Environmental Dissemination of Selected Antibiotics from Hospital Wastewater to the Aquatic Environment. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyestani, Z.; Khademi, F.; Teimourpour, R.; Amani, M.; Arzanlou, M. Prevalence and mechanisms of ciprofloxacin resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from hospitalized patients, healthy carriers, and wastewaters in Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felisardo, R.J.A.; Brillas, E.; Romanholo Ferreira, L.F.; Cavalcanti, E.B.; Garcia-Segura, S. Degradation of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin in urine by electrochemical oxidation with a DSA anode. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frade, V.M.F.; Dias, M.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Palma, M.S.A. Environmental contamination by fluoroquinolones. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cuasquer, G.J.P.; Li, Z.; Mang, H.P.; Lv, Y. Occurrence of typical antibiotics, representative antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and genes in fresh and stored source-separated human urine. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Wan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, J. Occurrence and fate of quinolone and fluoroquinolone antibiotics in a municipal sewage treatment plant. Water Res. 2012, 46, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Pei, W.; Li, X.; Wei, Q.; Liu, W. Characterization, degradation pathway and microbial community of aerobic granular sludge with ciprofloxacin at environmentally relevant concentrations. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 205, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.K.; Saha, A.K.; Sinha, A. Removal of ciprofloxacin using modified advanced oxidation processes: Kinetics, pathways and process optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Manickam, S.; Wang, W.; Fu, L.; Bie, H.; Wang, B.; Sun, X. Hybrid advanced oxidation process for rapid ciprofloxacin removal: Coupling hydrodynamic cavitation with UV/H2O2. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 120, 107475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milh, H.; Yu, X.; Cabooter, D.; Dewil, R. Degradation of ciprofloxacin using UV-based advanced removal processes: Comparison of persulfate-based advanced oxidation and sulfite-based advanced reduction processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 144510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.J.S.; El Kori, N.; Melián-Martel, N.; Del Río-Gamero, B. Removal of ciprofloxacin from seawater by reverse osmosis. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, J.; Yang, X.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. Study on preparation of a pizza-like attapulgite-based composite membrane and its performance on methylene blue and ciprofloxacin removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio, D.A.; Rivas, B.L.; Urbano, B.F. Ultrafiltration membranes with three water-soluble polyelectrolyte copolymers to remove ciprofloxacin from aqueous systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 351, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njaramba, L.K.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.M. Fabrication of porous beta-cyclodextrin functionalized PVDF/Fe MOF mixed matrix membrane for enhanced ciprofloxacin removal. Clean Water 2024, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, F.; Borba, F.H.; Pellenz, L.; Schmitz, M.; Godoi, B.; Espinoza-Quiñones, F.R.; de Pauli, A.R.; Módenes, A.N. Degradation of ciprofloxacin by the Electrochemical Peroxidation process using stainless steel electrodes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2855–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh, M.M.; Shabanloo, A.; Ansari, A.; Esfandiari, M.; Mousazadeh, M.; Tari, K. Anodic oxidation of ciprofloxacin antibiotic and real pharmaceutical wastewater with Ti/PbO2 electrocatalyst: Influencing factors and degradation pathways. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasulochana, P.; Preethy, V. Comparison on efficiency of various techniques in treatment of waste and sewage water—A comprehensive review. RET Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2016, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazal, H.; Koumaki, E.; Hoslett, J.; Malamis, S.; Katsou, E.; Barcelo, D.; Jouhara, H. Insights into current physical, chemical and hybrid technologies used for the treatment of wastewater contaminated with pharmaceuticals. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdağ, E.; Demirel, M.F.; Benek, V.; Doğru, E.; Önal, Y.; Alkan, M.H.; Erol, K.; Alacabey, İ. Efficient Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Water Using High-Surface-Area Activated Carbon Derived from Rice Husks: Adsorption Isotherms, Kinetics, and Thermodynamic Evaluation. Molecules 2025, 30, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velkova, Z.; Lazarova, K.; Kirova, G.; Gochev, V. Recent Advances in Pharmaceuticals Biosorption on Microbial and Algal-Derived Biosorbents. Processes 2025, 13, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.S.C.; Santos, J.; Souza, A.R.; Spessato, L.; Pezoti, O.; Alves, H.J.; Colauto, N.B.; Almeida, V.C.; Dragunski, D.C. Biosorption of reactive red-120 dye onto fungal biomass of wild Ganoderma stipitatum. Desalin. Water Treat. 2018, 102, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, A.; Bhatti, H.N.; Hanif, M.A. Removal of zirconium from aqueous solution by Ganode6rma lucidum: Biosorption and bioremediation studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, T.; Cabuk, A.; Tunali, S.; Yamac, M. Biosorption potential of the macrofungus Ganoderma carnosum for removal of lead(II) ions from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard Subst. Environ. Eng. 2006, 41, 2587–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Biosorption of Cu(II) from Aqueous Solutions by a Macrofungus (Ganoderma lobatum) Biomass and its Biochar. NEPT Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettem, K.; Almusallam, A.S. Equilibrium, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Studies on the Biosorption of Selenium (IV) Ions onto Ganoderma Lucidum Biomass. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 2293–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, G.M.; Marques de Souza, C.G.; Vaz de Araújo, C.A.; Bona, E.; Haminuik, C.W.I.; Castoldi, R.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M. Biosorption of herbicide picloram from aqueous solutions by live and heat-treated biomasses of Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst and Trametes sp. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 215–216, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, U.; Kalčíková, G.; Marolt, G.; Skalar, T.; Andreja Gotvajn, A.Ž. Potential of waste fungal biomass for lead and cadmium removal: Characterization, biosorption kinetic and isotherm studies. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, A.; Alenezi, K.M.; Humaidi, J.R.; Haque, A.; Mahgoub, S.M.; Mokhtar, A.M.; Shaban, A.; Mansour, M.M.M.; Mahmoud, R. Innovative eco-sustainable reishi mushroom-based adsorbents for progesterone removal and agricultural sustainability. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 16690–16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazkova, M.; Angelova, G.; Goranov, B.; Mihaylova, D.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A.; Krastanov, A. Mycelial growth kinetics, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of a submerged culture of the medicinal fungi Ganoderma resinaceum GA1M isolated from Bulgaria. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2024, 13, e10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacèra, Y.; Aicha, B. Equilibrium and kinetic modelling of methylene blue biosorption by pretreated dead Streptomyces rimosus: Effect of temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 119, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.K. Removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solution by adsorption using activated tea waste. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darajeh, N.; Alizadeh, H.; Leung, D.W.M.; Rashidi Nodeh, H.; Rezania, S.; Farraji, H. Application of Modified Spent Mushroom Compost Biochar (SMCB/Fe) for Nitrate Removal from Aqueous Solution. Toxics 2021, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, S.K.; Pankaj, P.S.; Amar, S.; Roy, R.K. A Simple UV Spectrophotometric Method Development and Validation for Estimation of Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride in Bulk and Tablet Dosage Form. Asian J. Res. Chem. 2012, 5, 336–339. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, B.; Krishnamoorthy, A.S.; Amirtham, D.; Sharmila, D.J.S.; Renukadevi, P.; Malathi, V.G. FT-IR Spectroscopic Characteristics of Ganoderma Lucidum Secondary Metabolites. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Chen, C.; Lv, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Ren, H.; Hassan, M.L. Preparation and Electrochemical Application of Porous Carbon Materials Derived from Extraction Residue of Ganoderma lucidum. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 166, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan-Mohtar, W.A.; Young, L.; Abbott, G.M.; Clements, C.; Harvey, L.M.; McNeil, B. Antimicrobial Properties and Cytotoxicity of Sulfated (1,3)-β-D-Glucan from the Mycelium of the Mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drakopoulos, A.I.; Ioannou, P.C. Spectrofluorimetric study of the acid–base equilibria and complexation behavior of the fluoroquinolone antibiotics ofloxacin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin and pefloxacin in aqueous solution. Anal. Chim. Acta 1997, 354, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hong, H.; Liao, L.; Ackley, C.J.; Schulz, L.A.; MacDonald, R.A.; Mihelich, A.L.; Emard, S.M. A mechanistic study of ciprofloxacin removal by kaolinite. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 88, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.K.; Bajpai, M.; Rai, N. Sorptive removal of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride from simulated wastewater using sawdust: Kinetic study and effect of pH. Water SA 2012, 38, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirizadeh, A.; Solisio, C.; Converti, A.; Casazza, A.A. Efficient removal of tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and amoxicillin by novel magnetic chitosan/microalgae biocomposites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 329, 125115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.; Shehata, N.; Khedr, N.; Elsayed, K.N.M. Management of ciprofloxacin as a contaminant of emerging concern in water using microalgae bioremediation: Mechanism, modeling, and kinetic studies. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomina, M.; Gadd, G.M. Biosorption: Current perspectives on concept, definition and application. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağ, Y.; Aktay, Y. Kinetic studies on sorption of Cr (VI) and Cu (II) ions by chitin, chitosan and Rhizopus arrhizus. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 12, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, U.A.; Sarioglu, M. Removal of tetracycline from wastewater using pumice stone: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. State of the Art for the Biosorption Process—A Review. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 170, 1389–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Yun, Y.S.; Park, J.M. The past, present, and future trends of biosorption. Biotechnol. Bioproc. 2010, 15, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereira, V.R.A.; Amorim, C.L.; Cravo, S.M.; Tiritan, M.E.; Castro, P.M.L.; Afonso, C.M.M. Fluoroquinolones biosorption onto microbial biomass: Activated sludge and aerobic granular sludge. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 110, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mashhadani, E.S.M.; Al-Mashhadani, M.K.H.; Al-Maari, M.A. Biosorption of Ciprofloxacin (CIP) using the Waste of Extraction Process of Microalgae: The Equilibrium Isotherm and Kinetic Study. Iraqi J. Chem. Pet. Eng. 2023, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruganti, R.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Panda, T.K.; Shee, D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Synthesis of algal–bacterial sludge activated carbon/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its potential in antibiotic ciprofloxacin removal by simultaneous adsorption and heterogeneous Fenton catalytic degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 67594–67612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Truong, Q.M.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, W.H.; Dong, C.D. Pyrolysis of marine algae for biochar production for adsorption of Ciprofloxacin from aqueous solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| C0, mg/g | qe,exp mg/g | Pseudo-First-Order Kinetic Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qem, mg/g | k1, min−1 | R2 | qem, mg/g | k2, g/mg min | R2 | ||

| 4 | 3.15 | 2.56 | 0.0624 | 0.924 | 3.33 | 0.0509 | 0.999 |

| 12 | 8.42 | 5.36 | 0.0529 | 0.977 | 8.93 | 0.0187 | 0.999 |

| 20 | 11.93 | 5.28 | 0.0389 | 0.981 | 12.65 | 0.0130 | 0.999 |

| Langmuir Isotherm Model | Freundlich Isotherm Model |

|---|---|

| qm = 18.4 mg/g | kF = 3.59 (mg/g)(L/mg)1.65 |

| kL = 0.229 L/g | n = 1.65 |

| R2 = 0.992 | R2 = 0.989 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazarova, K.; Kirova, G.; Velkova, Z.; Angelova, G.; Zahariev, N.; Iliev, I.; Gochev, V. Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions by Waste-Pretreated Ganoderma resinaceum Biomass: Effect of Process Parameters and Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. Processes 2025, 13, 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123920

Lazarova K, Kirova G, Velkova Z, Angelova G, Zahariev N, Iliev I, Gochev V. Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions by Waste-Pretreated Ganoderma resinaceum Biomass: Effect of Process Parameters and Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123920

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarova, Kristiana, Gergana Kirova, Zdravka Velkova, Galena Angelova, Nikolay Zahariev, Ivan Iliev, and Velizar Gochev. 2025. "Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions by Waste-Pretreated Ganoderma resinaceum Biomass: Effect of Process Parameters and Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies" Processes 13, no. 12: 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123920

APA StyleLazarova, K., Kirova, G., Velkova, Z., Angelova, G., Zahariev, N., Iliev, I., & Gochev, V. (2025). Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions by Waste-Pretreated Ganoderma resinaceum Biomass: Effect of Process Parameters and Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. Processes, 13(12), 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123920